Abstract

Introduction

Qualitative methods have become integral in health services research, and Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use (BMHSU) is one of the most commonly employed models of health service utilisation. The model focuses on three core factors to explain healthcare utilisation: predisposing, enabling and need factors. A recent overview of the application of the BMHSU is lacking, particularly regarding its application in qualitative research. Therefore, we provide (1) a descriptive overview of the application of the BMHSU in health services research in general and (2) a qualitative synthesis on the (un)suitability of the model in qualitative health services research.

Methods

We searched five databases from March to April 2019, and in April 2020. For inclusion, each study had to focus on individuals ≥18 years of age and to cite the BMHSU, a modified version of the model, or the three core factors that constitute the model, regardless of study design, or publication type. We used MS Excel to perform descriptive statistics, and applied MAXQDA 2020 as part of a qualitative content analysis.

Results

From a total of 6319 results, we identified 1879 publications dealing with the BMSHU. The main methodological approach was quantitative (89%). More than half of the studies are based on the BMHSU from 1995. 77 studies employed a qualitative design, the BMHSU was applied to justify the theoretical background (62%), structure the data collection (40%) and perform data coding (78%). Various publications highlight the usefulness of the BMHSU for qualitative data, while others criticise the model for several reasons (eg, its lack of cultural or psychosocial factors).

Conclusions

The application of different and older models of healthcare utilisation hinders comparative health services research. Future research should consider quantitative or qualitative study designs and account for the most current and comprehensive model of the BMHSU.

Keywords: organisation of health services, quality in health care, health services administration & management, public health, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Explores the application of the widely adopted behavioural model of health services use without limiting the search on target group, care setting or disease.

Might have missed studies that did not mention the behavioural model of health services use, or the three core factors in the title and abstract of the publications.

Gives insights to the application of the behavioural model of health services use in qualitative research which have received little attention so far.

Introduction

Healthcare utilisation refers to the use of the healthcare system ‘by persons for the purpose of preventing and curing health problems, promoting maintenance of health and well-being, or obtaining information about one’s health status and prognosis’.1 A needs-based healthcare system meets the needs of a person objectively identified by (health) professionals and considers the demands of an individual. If this interaction is successful, overuse, underuse and misuse of healthcare systems can be avoided. Otherwise, there is the possibility of compromising the health of an individual and placing burden on the healthcare system.2 To avoid overuse, underuse and misuse of the healthcare system, it is important to consider the (non-)use of healthcare services, which is determined by a variety of contextual and individual factors.3 As a measurable construct, healthcare service utilisation is primarily determined through quantitative surveys. To explore individual demands, qualitative methods can provide important and rich information within the field of health services research.4 5 Various models have been developed across a variety of disciplines to explore and predict individuals' intentions and behaviours as they utilise healthcare services.6 In health services research, the behavioural model of health services use (BMHSU) is the most frequently cited model of healthcare service utilisation.6 The model was developed by Andersen, and was based on a national quantitative survey that aimed to understand families’ use of health services.7 8 The model focuses on three core factors to explain healthcare utilisation: predisposing factors (eg, age, education), enabling factors (eg, income, hospital density) and need factors (eg, health status).8

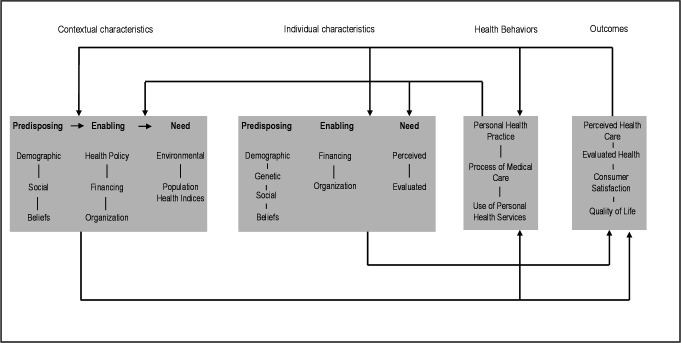

In recent years, Andersen’s initial behavioural model has undergone continuous development, where new focus was placed on various factors,8–10 such as ‘consumer satisfaction’ in the 1970s,11 12 and ‘health status’, ‘personal health practice’ and ‘external environment’ in the 1980s.9 13 In 1995, Andersen himself reviewed the model and its development and has since included feedback loops to consider how treatment outcomes affect health behaviour.8 Additional ‘contextual and individual characteristics’ were added to the model in the 2000s.8 Some of these further developments were carried out in cooperation with other authors, for example, Andersen and Newman’s Framework of Viewing Health Services Utilisation11 or Aday and Andersen’s Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care.12 The BMHSU was modified for specific settings (eg, complementary and alternative medicine14) and for specific target groups (eg, the behavioural model for vulnerable populations for homeless people13). Currently, many versions of the model for different settings or target groups are available and applied in health services research. The most current and comprehensive model is the BMHSU of the year 201315 (figure 1). The main focus of that model is on the factors that facilitate or impede an individual’s access to healthcare services. According to the model, access is determined by contextual characteristics, individual characteristics, health behaviours and outcomes. Contextual characteristics include circumstances and the environment; individual characteristics are determined by a person’s life circumstances including, for example, genetics and socialisation; health behaviours are an individual’s personal practices; and outcomes are reflected by an individual’s health status and consumer satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use.15

The application of the BMHSU and its different versions has already been examined in several systematic reviews. These are, for example, reviews focusing on specific diseases16 or settings.17 The most recent systematic review from Babitsch et al3 has examined the application of the BMHSU in general healthcare, but excludes specific care settings (eg, maternal health), specific target groups (eg, veterans) and studies that focus on specific diseases (eg, HIV).3 These reviews considered quantitative studies only, and excluded qualitative studies, although qualitative methods have become an important and integral part of health services research, and are useful for recording detailed descriptions and complex issues in the context of healthcare utilisation and healthcare services.4 5 Even though the BMHSU is the most frequently cited model of access to healthcare services,6 an overview of the development and application of the BMSHU over the last 50 years is lacking, especially in terms of its application in qualitative research.

Primarily we aimed at a review of qualitative applications of the BMHSU. We learnt from exploratory searches that its application in qualitative research will be difficult to find. That was when we decided to undertake a meticulous screening of titles and abstracts of publications dealing with the BMHSU, to provide a descriptive overview on study characteristics as a first step, to learn about the application of the model in general which would help to put the qualitative findings into perspective. In a second step, we focus on a qualitative synthesis of the application of the BMHSU in qualitative health service research. Here, we synthesise (1) the application of different versions of the BMHSU, (2) the (un)suitability of the BMHSU from the authors’ perspective and (3) which factors of the BMHSU were analysed in publications with qualitative approach. Further analyses, for example, the synthesis of the quantitative studies is object of future publications.

Methods

This scoping review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)18 (online supplemental additional file 1). It exists no review protocol. For study selection, two researchers (ML and JT) independently screened all selected titles and abstracts for relevance. For the descriptive overview, data extraction from title and abstract was divided between two researchers (ML and JT). One researcher’s extraction was verified by the other researcher with extracting data of a 25% random sample and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. For the qualitative synthesis, the full texts were independently screened for eligibility and the data were independently extracted by two researchers (ML and JT). Two researchers (ML and JT) coded the material together. Through all these processes, discrepancies were discussed and resolved by a team of reviewers (ML, JT and EMB).

bmjopen-2020-045018supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search in March and April 2019, and performed an updated search in April 2020 using the Embase via Ovid, Medline via PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO via EBSCOhost and Social Science Citation Index via Web of Science databases.

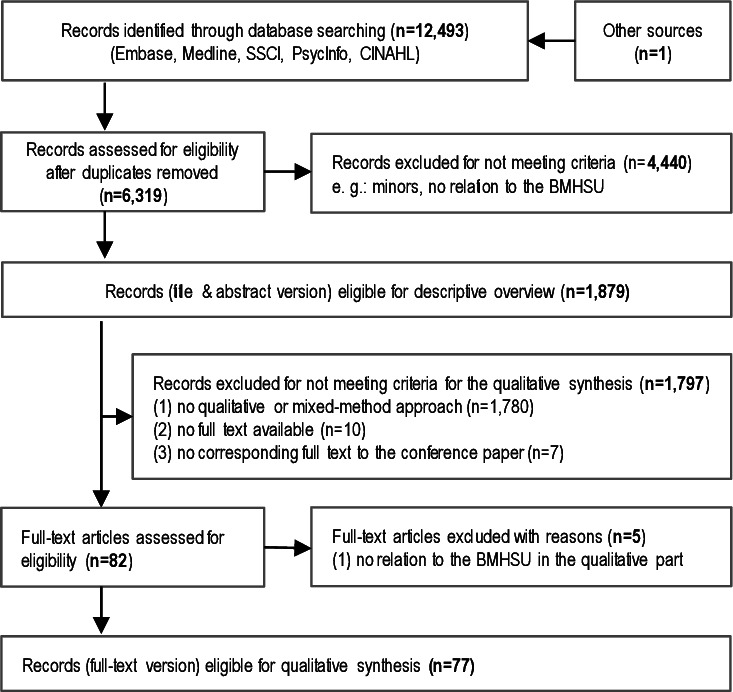

We expanded the search strategy of Babitsch et al3 inter alia without limitation on the target groups, care settings and diseases of interest. We adjusted the search terms to the particular databases and combined thesaurus and keywords pertaining to the BMHSU and its three core factors. The detailed search strategy for one database is identified in online supplemental additional file 2. The search was conducted for publications published from 1968 to April 2020. Figure 2 shows the study selection process according to the PRISMA statement.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram based on PRISMA. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

bmjopen-2020-045018supp002.pdf (63.4KB, pdf)

Descriptive overview

Study selection

As an initial first step, title-abstract-screening was performed for all search results. We included all publications focused on adult populations that applied either the BMHSU, a modified version of the model, or all three core factors of the model. No limitations were set for language, study design, or publication type. Studies were excluded if they could not be obtained via electronic access, interlibrary loan or through contact with the authors.

Data extraction

The following inductively formed characteristics were extracted from the title and abstract of each included study: publication year, first author, region, methodological approach, target group, care setting and the applied version of the BMHSU. Beyond labelling included studies as quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods we undertook no attempt to specify details of the study design, quantify reporting quality or risk of bias. Such a strategy is consistent with scoping reviews.18 For abstracts with insufficient information regarding our extraction characteristics, we obtained the full-text version of the publications.

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics with MS Excel for the descriptive overview.

Qualitative synthesis

Based on the data extraction of the descriptive overview, we obtained the full texts of all publications with a qualitative approach, either specifically or as part of a mixed-method design. Finally, we screened the full-texts of the remaining results and excluded publications with no relation to the BMHSU in the qualitative part (figure 2).

Quality appraisal

The quality of the qualitative studies and the qualitative part of studies with a mixed-method design was assessed independently by two researchers (ML and JT) using the ‘Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research’.19 Authors resolved disagreement by discussion. The checklist contains ten items that assess the methodological quality of the design, data collection and data analysis of the publications. The tool comprises four answer choices: ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ and ‘not applicable’. If there was insufficient information to answer a given question, the response was recorded as ‘unclear’. We included all studies with qualitative and mixed-method approach in the qualitative synthesis regardless of the analysed quality of the studies.

Data analysis

For the qualitative synthesis, MAXQDA 2020 software was used.20 To answer the research questions, the following deductive codes were coded in the data material: applied version of the BMHSU, the way in which the model is applied in qualitative studies, the potential for and limitations of the BMHSU, and the extensions of the BMHSU described by the authors. The subcode ‘potential and limitations of the BMHSU’ is based solely on descriptions and conclusions of the authors of the individual publications. In addition, we considered which of the BMHSU factors were examined and which were complemented by inductive factors that emerged from the data material. We distinguished between the three core factors (predisposing factors, enabling factors and need factors) and the associated factors (eg, demographics, health policy and perceived need). We recoded all documents with the final coding frame. In the context of the content-structuring qualitative analysis, the summarising reduction of the coding followed the approach detailed by other researchers.21 The presented results are structured based on these main categories.

Results

Descriptive overview of the use of the BMHSU in health services research

After removal of duplicates 6319 records remained of which 1879 dealt with the BMHSU, with its three core factors, or a modified version of the model (figure 2).

Starting with the initial use of the model in 1973, reception toward the model has increased considerably in recent decades (table 1). Two-thirds of all identified publications were published in the last ten years (ie, since 2010), and more than 50% of the publications have been published since 2013. Further, 70% of the publications are from North-America (USA or Canada), followed by Asia (13%) and Europe (9%). The majority are quantitative studies (n=1680, 89%), while 4% of all records are qualitative studies (n=69) and 3% are reviews (n=61). In all, 30 publications are mixed-method studies (2%) and 39 publications (2%) are theoretical reflections without empirical data. As there are numerous diverse care settings, target groups and diseases of interests, table 1 presents the three most frequent categories. An overview of the broad range of the characteristics can be found in online supplemental additional file 3. General healthcare, as care provided by general practitioners, is the most studied care setting (n=471, 25%), followed by nursing care (n=237, 13%) and mental health services (n=222, 12%). About one quarter of all studies deals with individuals aged ≥50 years (n=481). In addition, 17% of the publications focus on migrants (n=322), and 14% on women (n=256). Half of the publications (n=936) do not account for a specific disease; for 12% (n=229) of all publications, mental disorders represent the most frequently examined diseases of interest.

Table 1.

Quantitative description of publications using the behavioural model of health services use in health services research

| Descriptive overview (n=1879) (based on title and abstract) n (%)* |

Qualitative synthesis (n=77) (based on full text version) n (%)* |

|

| Year | ||

| 2010-2019 | 1224 (65) | 70 (91) |

| 2000-2009 | 440 (23) | 7 (9) |

| 1990–1999 | 168 (9) | 0 (0) |

| 1980-1989 | 38 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 1968-1979 | 9 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Region | ||

| North-America | 1275 (70) | 43 (56) |

| Asia | 244 (13) | 6 (8) |

| Europe | 163 (9) | 14 (18) |

| Africa | 68 (4) | 12 (16) |

| South America | 49 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Oceania | 29 (2) | 5 (6) |

| Methodological approach | ||

| Quantitative | 1680 (89) | / |

| Qualitative | 69 (4) | 58 (75) |

| Review | 61 (3) | / |

| Theoretical | 39 (2) | / |

| Mixed-method | 30 (2) | 19 (25) |

| Care setting† | ||

| General health care‡ | 471 (25) | 12 (16) |

| Nursing care§ | 237 (13) | 5 (6) |

| Mental health services | 222 (12) | 6 (8) |

| Screening | 107 (6) | 7 (9) |

| Perinatal care¶ | 77 (4) | 7 (9) |

| Target group† | ||

| Individuals ≥50 years | 481 (26) | 11 (14) |

| Migrants | 322 (17) | 23 (30) |

| Women | 256 (14) | 16 (21) |

| Disease of interest† | ||

| No specific disease | 936 (50) | 27 (35) |

| Mental disorders | 229 (12) | 7 (9) |

| Cancer | 134 (7) | 9 (12) |

| HIV | 96 (5) | 11 (14) |

*The sum might be less than 100% as only the three most frequent categories are represented in this table. Online supplemental additional file 3 shows all characteristics.

†Bold: three most frequent categories.

‡General healthcare: care provided by general practitioners.

§Nursing: homecare, long-term care, formal care, care facility, informal care, respite care, institutionalised care and transportation services.

¶Perinatal care: including midwifery services.

bmjopen-2020-045018supp003.pdf (60.9KB, pdf)

Qualitative synthesis of the use of the BMHSU in qualitative health services research

After excluding publications without a qualitative or mixed-method approach (n=1780), those without a full text available (n=10), those without a corresponding full text to a conference paper (n=7), and those that were not at all related to the BMHSU in the qualitative part (n=5), a total of 77 studies remained and were included in the qualitative synthesis of qualitative studies applying the BMHSU (figure 2).

Although the first known application of the BMHSU in a qualitative study was from 2002, most of the qualitative records were identified in 2010 and later (n=70, 91%; table 1). Most publications are from North-America, USA or Canada (n=43, 56%), 18% (n=14) are from Europe and 16% (n=12) are from Africa. General healthcare is the care setting that was explored most often in publications adopting a qualitative study design (n=12, 16%), followed by screening and perinatal care (n=7 each, 9%). Qualitative research applying the BMHSU primarily targets migrants (n=23, 30%), women (n=16, 21%) and individuals aged ≥50 years (n=11, 14%). Further, 35% of qualitative publications (n=27) address no specific disease; if a particular disease was of interest, it is most often HIV (n=11, 14%) or cancer (n=9, 12%).

Two-thirds of the qualitative studies use personal interviews as a data collection method (n=51, 81%). The sample size varies between 5 and 470 participants. Most of the qualitative studies interview the target group directly (n=65, 84%). Health professionals and/or next of kin assessments are the sole source of information in 12 studies (16%). In addition, 18 of the 65 qualitative studies that approached the target group obtained further information from health professionals (n=13), next of kin (n=1), or both (n=4; for further details; online supplemental additional file 4).

bmjopen-2020-045018supp004.pdf (169.6KB, pdf)

Application of the different versions of the Andersen model

The BMHSU is applied in the various studies to justify the theoretical background (62%), structure the data collection (40%), for example, such as aiding in the development of the interview guide, and for data coding (78%). More than half of the studies (n=42)22–61 are based on the BMHSU from 1995.9 Multiple studies (n=11) use the behavioural model for vulnerable populations.62–71 Twelve studies30 41 54 60 72–79 employ Andersen and Newman’s Framework of Viewing Health Services Utilisation, eight studies41 42 80–85 apply Aday and Andersen’s Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care and seven studies41 47 51 54 58 60 86 are based on the original Behavioural Model of Families’ Use of Health Services from 1968. Individual studies use other models, such as the expanded model from Bradley et al28 (online supplemental additional file 4).

(Un)suitability of the Andersen model from the authors’ perspective

Overall, 29 publications22 30–32 34 35 39 41 42 44 45 47 48 50 52 54 55 68 71 72 77–79 82 87–91 described that the model was suitable in their work, for example, to obtain and evaluate qualitative data. Of these, 17 publications34 35 39 42 44 45 48 50 52 72 77–79 82 87 88 91 highlight the general suitability of the BMSHU for qualitative data: ‘Andersen’s framework provides a valid, consistent and unbiased manner in which to code and classify qualitative data’.88 Various publications (n=17)34 39 42 44 45 48 50 52 54 57 72 77–79 87 88 92 described how their data can be applied very well to the BMHSU and its factors. Others described that the strength of the model lies in its consideration of both patient-related and environmental factors,39 50 90 and that the model allows for ‘a more transparent comparison with findings emerging from other studies’.87

Some studies (n=11) described the suitability of the BMHSU and additionally criticised some parts of the model.22 31 35 39 48 52 54 89 91–93 For instance, there are authors (n=8) who criticised the model, but did not propose changes to its structure.22 25 35 48 89 91–93 Some studies22 25 described that cultural factors are not adequately represented in the model: ‘the model has been noted not to be sensitive to the diverse cultural and structural barriers in healthcare among minority groups’.25 According to the authors of some publications,35 48 the model would need to further elaborate on the relationship between the three core factors of the BMHSU and the relevance of each. Other authors claimed that the model does not cover all factors of healthcare utilisation, such as psychosocial factors,22 and would be less suitable for studies on HIV89 or healthcare coverage.93

Not all critics proposed model modifications, but some of the identified limitations may lead to modifications of or additions to the BMHSU. Based on their findings, some authors (n=12) identified additional factors not covered by the model that impact healthcare utilisation,23 28 31 36 37 39 54 57 74 80 85 90 such as health literacy,39 54 90 or competing priorities23 39 (table 2). The basic structure of the BMHSU is retained as part of these expansions.

Table 2.

Additions to the behavioural model of health services use (BMHSU) from qualitative health services research

| Contextual characteristics | Individual characteristics | Health behaviours | Outcome | Further additions | ||

| Predisposing factors | Enabling factors | Need factors | ||||

| Intake and engagement36 | Competing priorities23 39 | Medication characteristics39 | Unmet need31 | Distinction between problem recognition, decision to seek help and decision to use healthcare system74 | Dental service use and dental experiences57 | Psychosocial factors28 |

| Patient and transition36 | Fear23 | Reminder strategies39 | ||||

| Medication adherence strategies36 | (Mis)trust23 90 | Personal emergency alarm system31 | ||||

| Billing36 | Previous experiences23 90 | Informal care system31 | Avoidant strategies54 | Intended and actual use28 57 | Situation and satisfaction of the next of kin80 | |

| Specific programme for support36 | Contingency plans for future falls31 | Characteristics at the level of informal caregivers37: Physician referral, knowledge about the services, acculturation |

||||

| Health Literacy36 | Health literacy39 54 90 | Mental health85 | ||||

| Individualised care36 | Characteristics at the level of informal caregivers37: Familism, perception about services, religiosity, gender roles | Spirituality54 | Service experience57 | Vulnerability factors71 | ||

| Philosophical approaches36 | ||||||

| Pharmacy services39 | ||||||

| Rheumatologist90 | Conscientiousness90 | |||||

The table shows the variables as the authors of the original studies assigned them to BMHSU core factors.

Other studies fundamentally changed the original structure of the BMHSU, both in terms of the factors24 38 74 and the feedback loops provided,39 52 62 ultimately impacting the influence between each of the factors in the model. Some studies emphasised the distinction between the three core factors as predisposing and inhibiting factors, and as enabling and impeding factors,24 26 62 while others combined the model with another model.61

Factors of the BMHSU emerging from qualitative health services research

Individual characteristics are considered much more frequently than contextual characteristics, health behaviours or health outcomes in publications that adopted a qualitative design. Table 3 lists all factors of the BMHSU with the number of publications that used each factor. Although the qualitative studies explored in our research considered a wide range of factors, there are still some other factors of the BMHSU that have not been considered in any of the included publications that featured a qualitative study design (eg, quality of life as an outcome factor or some predisposing factors as contextual characteristics).

Table 3.

Factors examined in publications

*These factors were inductive codes, developed along the data material.

Contextual characteristics: A total of 63 qualitative studies (82%) mentioned contextual characteristics, of which enabling factors are most frequently included, such as health professional factors, for example, soft skills (n=22, 29%) or availability (n=21, 27%).

Individual characteristics: The most frequently researched factors pertain to individual characteristics, especially predisposing factors such as social networks (n=41, 53%), attitude towards healthcare services (n=33, 43%) and values (n=28, 36%). Nearly half of all studies considered accessibility of healthcare services as an enabling factor (n=34, 44%). The most common need factor was perceived symptoms (n=45, 58%).

Health behaviour: In terms of health behaviour, the relationship between the patient and provider (n=21, 27%), as well as complementary medicine (n=13, 17%) and self-care (n=11, 14%) were most often analysed in publications adopting a qualitative design.

Outcomes: Overall, about half of the qualitative studies (n=37) mentioned health outcomes in their analyses. Satisfaction with providers (n=18, 23%) and prior experience (n=17, 22%) were the most considered aspects.

During our qualitative syntheses of qualitative health services research studies, health literacy emerged as a inductive category, separated into individual94 and organisational health literacy.95 We identified associations with organisational health literacy in 25 studies (32%) and individual health literacy in 52 studies (68%; table 3). In the context of organisational health literacy, the focus was on access to health information: ‘share health risk information while empowering patients to make their own health decisions’.36 The most frequently mentioned factors among individual health literacy were knowledge (n=39, 51%) and competences (n=22, 29%), as exemplified by the following statement: ‘knowledge was empowering to make own choices and feel in control of their care decisions’.27

Quality assessment of publications with a qualitative study design

Of the 77 qualitative studies, four (5%) reported all ten aspects of the critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research.19 Most qualitative studies (n=69, 90%) reported between five and nine criteria from the checklist, and four studies (5%) reported fewer than five criteria. The two quality criteria that were most frequently fulfilled with 95% each (n=73) are the ‘congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology’ and the ‘congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data’.19 In contrast, the ‘influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa’19 is only addressed in nine publications (12%).

Discussion

This scoping review provides a recent overview of the development and application of the BMHSU in very different care settings, across different diseases and among publications examining different target groups. The BMHSU is mainly used in quantitative studies, but our review also shows the suitability of the model in qualitative research.

Descriptive overview of the use of the BMHSU in health services research

The general reception toward the BMHSU has increased considerably in recent years, as has the number of publications adopting this model, with most (70%) of all related publications stemming from North America. This is in line with another review,3 which excluded specific care settings and diseases. The dominance of research projects adopting quantitative design96 is reflected in this scoping review, as 89% of the identified publications used quantitative methods.

The BMHSU is mainly used for research examining healthcare in general, without focusing on specific diseases. This is not surprising, as the recent BMHSU was not developed for any specific care setting or disease.15 Still, a wide range of publications have focused on specific care settings (eg, nursing, mental health services) and diseases (eg, mental disorders). Individuals aged ≥50 years are the largest target group represented in this overview. Possible explanations for this finding include the fact that this population represents the largest, and fastest growing cohort in the broader population.97 Further, this group uses healthcare services most frequently.98

Qualitative synthesis on the use of the BMHSU in qualitative health services research

The relevance of the BMHSU for qualitative projects within health services research is demonstrated by our results. Still, there are some limitations within the BMHSU, which should be critically considered depending on the research question.

The publications featuring a qualitative design mainly consider the individual characteristics within the BMHSU. Since the primary interest of qualitative research is the subjective experience of individuals, this result is not surprising.99 In addition, it was noted that people from the target group were primarily interviewed in these studies, while there were fewer next of kin or health professionals interviewed. Experts may wish to consider obtaining more information about contextual characteristics in their research. Since the data extraction within the descriptive overview was carried out at the level of titles and abstracts, it is not possible to determine whether contextual characteristics in publications featuring a quantitative study design are more strongly represented in this review.

Although over half of all publications that adopted a qualitative design had been published since 2013, most of them considered the Andersen model of 1995, which is also a result of the review by Babitsch et al.3 Only one of the publications with a qualitative design54 adopted the most current and comprehensive BMHSU from the year 2013.15 This is interesting, as some authors expanded on an older version of the BMHSU and justified various missing factors (eg, provider negligence and dissatisfaction, location of a clinic), although these factors are actually included in the most current version of the BMHSU from 2013.15 It is important to consider that even Andersen himself had additional thoughts on the model.9 For example, he coauthored a publication with the aim to expand the view from the original model on psychosocial factors.28

One new factor that has been discussed in some of the considered studies is health literacy. Health literacy relates to many parts of the Andersen model and cannot be assigned to a specific level or factor. We recommend integrating health literacy as an additional factor in the BMHSU, as an individual’s health literacy and health-literate organisations are important foundations for the (non-)use of healthcare services, and consequently for healthcare research.94 95

Strengths and limitations

When interpreting the results, it should be noted that although we performed systematic searches, some publications might have been missed. For example, articles that did not mention the BMHSU, or the three core factors in the title and abstract were not included. Further, articles may have been excluded given that we restricted our search to five databases. However, it became apparent, that all previously known key publications have been identified through our search strategy.3 8 9 11 12 Another limitation is that the extraction of publication characteristics for descriptive overview was divided between the first authors (ML and JT) and were not extracted twice. For the qualitative synthesis, the data extraction was performed on full texts independently by two researchers. Also, the quality of this scoping review is based on the quality of the information contained in the included publications. We considered the general utilisation of the BMHSU in health services research (as identified in the descriptive overview) at the title and abstract level, and not at the full-text level. An analysis of the full-texts could provide further information about, and more detailed insights into, the application of the BMHSU. When coding the results based on the various model factors, one challenge faced by our team was appropriately assigning the factors, as the assignment of the factors was not always clear. The detailed description of the current BMHSU by Andersen et al15 served us substantially for the assignment of the factors. Any uncertainties were discussed in the review team. Also, our comparison of the various studies that adopted a qualitative design is limited by the fact that very different versions of the model were used.

Regarding the influence of the reviewers on the review, it should be mentioned that the review team was composed of individuals with experience in systematic reviews, health services research and qualitative methods. The review team had no affiliation with the research and no funding for the review. It should be noted that this scoping review is the first to explore the application of the widely adopted BMHSU without limiting our search based on target group, care setting, or disease since the model was initially published in 1968. Further, this review examined publications adopting qualitative study designs, strengthening the perceptions of qualitative methods in health services research. This review provides the first-ever overview of the (un)suitability of the BMHSU in qualitative research.

Conclusion

This scoping review reveals that the BMHSU, which is one of the main models in healthcare services research, has broad applications in very different care settings, across various diseases, and focuses on a wide range of target groups. The BMHSU is mainly used in quantitative studies, but our review also shows the suitability of the model for qualitative research. As health literacy in particular plays an increasingly important role in healthcare utilisation,94 we think it is important to take this factor into account in the BMHSU. In further research, it would be interesting to examine this relationship more thoroughly. Additionally, it might be interesting to compare the application of the BMHSU in quantitative and qualitative research. The application of so many different (and older) models of healthcare utilisation makes it difficult to compare the individual studies with one another. However, such a comparison would be particularly important in the context of health services research. For future health services research, the current and most comprehensive version of the BMHSU15 should always be considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lisa Lyssenko for her valuable comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, JT and EMB conceived the idea of the scoping review. ML and JT built the search strategy, screened the search results, and extracted the data. ML, JT and EMB interpreted the findings and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This manuscript is supported by the cooperative doctoral study course, 'Health Services Research: Collaborative Care' located in Freiburg, Germany. The doctoral study course is, in turn, brought forward by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts Baden-Württemberg. The article processing charge was funded by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Culture and the University of Education, Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This scoping review was based on published data. As researchers did not access any information that could lead to the identification of an individual patient, no concerning ethical issue was raised in this research. Therefore, obtaining ethical approval and consent of participants was waived.

References

- 1.Gellman MD, Turner JR, . Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Advisory Council on the Assessment of Developments in the Health Care System . Needs-Based regulation of the health care provision: introduction and summary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen's behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998-2011. Psychosoc Med 2012;9:Doc11. 10.3205/psm000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann W, Farin E, Menzel-Begemann A, et al. [Memorandum IV: Theoretical and Normative Grounding of Health Services Research]. Gesundheitswesen 2016;78:337–52. 10.1055/s-0042-105511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner BJ, Amick HR, Lund JL, et al. Use of qualitative methods in published health services and management research: a 10-year review. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:3–33. 10.1177/1077558710372810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricketts TC, Goldsmith LJ. Access in health services research: the battle of the frameworks. Nurs Outlook 2005;53:274–80. 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen R. A behavioral model of families' use of health services. Chicago, Ill: Univ. of Chicago, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care 2008;46:647–53. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tv L, Gohl D, Babitsch B. Re-visiting the Behavioral Model of Health Care Utilization by Andersen: A Review on Theoretical Advances and Perspectives. : Janssen C, Swart E, Tv L, . Health care utilization in Germany: theory, methodology, and results. New York: Springer New York, 2014: 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 1973;51:95–124. 10.2307/3349613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9:208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000;34:1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Using the behavioral model for complementary and alternative medicine: the CAM healthcare model. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine 2007;4. 10.2202/1553-3840.1035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Improving Acces to Care. : Kominski GF, . Changing the U.S. health care system: key issues in health services policy and management. 4th edn.. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass, 2013: 33–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guilcher SJT, Craven BC, McColl MA, et al. Application of the Andersen's health care utilization framework to secondary complications of spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:531–41. 10.3109/09638288.2011.608150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman Chong W, Moon-Ho Ho R. Caregiver needs and formal long-term care service utilization in the Andersen model: an individual-participant systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Integr Care 2018;18:121. 10.5334/ijic.s1121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joanna Briggs Institute . Checklist for qualitative research, 2017. Available: https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf [Accessed 26 Aug 2019].

- 20.GmbH V. MAXQDA: the art of data analysis. Available: https://www.maxqda.de/ [Accessed 27 Jan 2020].

- 21.Kuckartz U. Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice & using software. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrasik MP, Rose R, Pereira D, et al. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among low-income HIV-positive African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2008;19:912–25. 10.1353/hpu.0.0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artuso S, Cargo M, Brown A, et al. Factors influencing health care utilisation among Aboriginal cardiac patients in central Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:83. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bascur-Castillo C, Araneda-Gatica V, Castro-Arias H, et al. Determinants in the process of seeking help for urinary incontinence in the Chilean health system. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2019;144:103–11. 10.1002/ijgo.12685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayuo J. Experiences with out-patient hospital service utilisation among older persons in the Asante Akyem North District- Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:652. 10.1186/s12913-017-2604-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boateng L, Nicolaou M, Dijkshoorn H, et al. An exploration of the enablers and barriers in access to the Dutch healthcare system among Ghanaians in Amsterdam. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:75. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge JP, Devaney J, et al. Disabled women's experiences of accessing and utilising maternity services when they are affected by domestic abuse: a critical incident technique study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:181. 10.1186/s12884-015-0616-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley EH, McGraw SA, Curry L, et al. Expanding the Andersen model: the role of psychosocial factors in long-term care use. Health Serv Res 2002;37:1221–42. 10.1111/1475-6773.01053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler C, Kim-Godwin YS, Fox J. Exploration of health care concerns of Hispanic women in a rural southeastern North Carolina community. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care 2008;8:22–32. 10.14574/ojrnhc.v8i2.186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiu TML. Usage and Non-usage behaviour of eHealth services among Chinese Canadians caring for a family member with dementia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiu MWY. Psychosocial responses to falling in older Chinese immigrants living in the community, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conner NE, Chase SK. Decisions and caregiving: end of life among blacks from the perspective of informal caregivers and decision makers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:454–63. 10.1177/1049909114529013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corboy D, McDonald J, McLaren S. Barriers to accessing psychosocial support services among men with cancer living in rural Australia: perceptions of men and health professionals. Int J Mens Health 2011;10:163–83. 10.3149/jmh.1002.163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doshi RK, Malebranche D, Bowleg L, et al. Health care and HIV testing experiences among Black men in the South: implications for "Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain" HIV prevention strategies. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:123–33. 10.1089/apc.2012.0269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill P, Logan K, John B, et al. Participants’ experiences of ketamine bladder syndrome: A qualitative study. International Journal of Urological Nursing 2018;12:76–83. 10.1111/ijun.12167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawk M, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, et al. Exploring the healthcare environment and associations with clinical outcomes of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:495–503. 10.1089/apc.2017.0124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrera AP, Lee J, Palos G, et al. Cultural influences in the patterns of long-term care use among Mexican American family caregivers. J Appl Gerontol 2008;27:141–65. 10.1177/0733464807310682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrmann WJ, Haarmann A, Bærheim A. A sequential model for the structure of health care utilization. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176657. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, et al. Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen's behavioral model. AIDS Care 2015;27:817–28. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1009362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko LK, Taylor VM, Mohamed FB. "We brought our culture here with us": A qualitative study of perceptions of HPV vaccine and vaccine uptake among East African immigrant mothers. Papillomavirus Res 2019;7:21–5. 10.1016/j.pvr.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goh SNOI. Post acute care of the elderly in Singapore what factors influence use of services? Asia Pac J Soc Work Dev 2011;21:31–53. 10.1080/21650993.2011.9756095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koce F, Randhawa G, Ochieng B. Understanding healthcare self-referral in Nigeria from the service users’ perspective: a qualitative study of Niger state. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:209. 10.1186/s12913-019-4046-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohno A, Nik Farid ND, Musa G, et al. Factors affecting Japanese retirees’ healthcare service utilisation in Malaysia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010668. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maulik PK, Tewari A, Devarapalli S, et al. The systematic medical appraisal, referral and treatment (smart) mental health project: development and testing of electronic decision support system and formative research to understand perceptions about mental health in rural India. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164404. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukasa B. Maternal and child health access disparities among recent African immigrants in the United States, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obikunle AF. Barriers to breast cancer prevention and screening among African American women, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parkman T, Neale J, Day E, et al. Qualitative exploration of why people repeatedly attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:140. 10.1186/s12913-017-2091-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porteous T, Wyke S, Hannaford P, et al. Self-Care behaviour for minor symptoms: can Andersen's behavioral model of health services use help us to understand it? Int J Pharm Pract 2015;23:27–35. 10.1111/ijpp.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rööst M, Jonsson C, Liljestrand J, et al. Social differentiation and embodied dispositions: a qualitative study of maternal care-seeking behaviour for near-miss morbidity in Bolivia. Reprod Health 2009;6:13. 10.1186/1742-4755-6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schatz E, Seeley J, Negin J, et al. “For us here, we remind ourselves”: strategies and barriers to ART access and adherence among older Ugandans. BMC Public Health 2019;19:131. 10.1186/s12889-019-6463-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serna CA. Exploring oral health problems in adult Hispanic migrant farmworkers: a mixed-methods approach, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tewari A, Kallakuri S, Devarapalli S, et al. Process evaluation of the systematic medical appraisal, referral and treatment (smart) mental health project in rural India. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:385. 10.1186/s12888-017-1525-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White AW. The role of social and cultural factors on preventive health service use among young rural, African American men: a narrative inquiry 2017.

- 54.Isaak CA, Mota N, Medved M, et al. Conceptualizations of help-seeking for mental health concerns in first nations communities in Canada: a comparison of fit with the Andersen behavioral model. Transcult Psychiatry 2020;57:346–62. 10.1177/1363461520906978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HY, Lee MH, Jang YJ, et al. Breast cancer screening disparity among Korean American immigrant women in Midwest. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017;18:2663–7. 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.10.2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberson MC. Refusal of epidural anesthesia for labor pain management by African American parturients: an examination of factors. Aana J 2019;87:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Due C, Aldam I, Ziersch A. Understanding oral health help-seeking among middle Eastern refugees and asylum seekers in Australia: an exploratory study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2020;48:188–94. 10.1111/cdoe.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green DC, Wheeler EM. A qualitative exploration of facilitators for health service use among aging gay men living with HIV. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2019;18:232595821988056. 10.1177/2325958219880569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fleury M-J, Grenier G, Farand L, et al. Reasons for emergency department use among patients with mental disorders. Psychiatr Q 2019;90:703–16. 10.1007/s11126-019-09657-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coleman TM. Help-Seeking experiences of African American men with depression, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Opoku D, Busse R, Quentin W. Achieving sustainability and scale-up of mobile health noncommunicable disease interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: views of policy makers in Ghana. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e11497. 10.2196/11497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blanas DA, Nichols K, Bekele M, et al. Adapting the Andersen model to a francophone West African immigrant population: hepatitis B screening and linkage to care in New York City. J Community Health 2015;40:175–84. 10.1007/s10900-014-9916-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Callahan CC. Cancer, vulnerability and financial quality of life: a mixed methods study, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cathers LA. Exploring substance use disorders community outpatient counselors' experiences treating clients with co-occurring medical conditions: an interpretative phenomenological analysis 2014.

- 65.Coe AB, Moczygemba LR, Gatewood SBS, et al. Medication adherence challenges among patients experiencing homelessness in a behavioral health clinic. Res Social Adm Pharm 2015;11:e110–20. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levison JH, Bogart LM, Khan IF, et al. “Where It Falls Apart”: Barriers to Retention in HIV Care in Latino Immigrants and Migrants. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:394–405. 10.1089/apc.2017.0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lor B, Ornelas IJ, Magarati M, et al. We Should Know Ourselves: Burmese and Bhutanese Refugee Women’s Perspectives on Cervical Cancer Screening. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29:881–97. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Noh H, Schroepfer TA. Terminally ill African American elders' access to and use of hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:286–97. 10.1177/1049909113518092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rice MB. Attitudes of women offenders towards Medicaid enrollment and coverage under the Affordable care act 2017.

- 70.Scott KL. Delay to treatment for Latinos diagnosed with lung and head-and-neck cancers: application of the behavioral model for vulnerable populations 2013.

- 71.Velez D, Palomo-Zerfas A, Nunez-Alvarez A, et al. Facilitators and barriers to dental care among Mexican migrant women and their families in North San Diego County. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:1216–26. 10.1007/s10903-016-0467-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dergal J. Family members' use of private companions in nursing homes: a mixed methods study, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gräßel E, Luttenberger K, Trilling A, et al. Counselling for dementia caregivers—predictors for utilization and expected quality from a family caregiver’s point of view. Eur J Ageing 2010;7:111–9. 10.1007/s10433-010-0153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henson LA, Higginson IJ, Daveson BA, et al. 'I'll be in a safe place': a qualitative study of the decisions taken by people with advanced cancer to seek emergency department care. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012134. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Navarro-Millán I, Zinski A, Shurbaji S, et al. Perspectives of rheumatoid arthritis patients on electronic communication and patient-reported outcome data collection: a qualitative study. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:80–7. 10.1002/acr.23580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rachlis B, Naanyu V, Wachira J, et al. Community perceptions of community health workers (CHWs) and their roles in management for HIV, tuberculosis and hypertension in Western Kenya. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149412. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rachlis B, Naanyu V, Wachira J, et al. Identifying common barriers and facilitators to linkage and retention in chronic disease care in Western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2016;16:741. 10.1186/s12889-016-3462-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Riang’a RM, Nangulu AK, Broerse JEW. “I should have started earlier, but I was not feeling ill!” Perceptions of Kalenjin women on antenatal care and its implications on initial access and differentials in patterns of antenatal care utilization in rural Uasin Gishu County Kenya. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202895. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Victor C, Davies S, Dickinson A, et al. "It just happens". Care home residents' experiences and expectations of accessing GP care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018;79:97–103. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Condelius A, Andersson M. Exploring access to care among older people in the last phase of life using the behavioural model of health services use: a qualitative study from the perspective of the next of kin of older persons who had died in a nursing home. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:138. 10.1186/s12877-015-0126-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han H, Perumalswami P, Kleinman L. Voices of multi-ethnic providers in NYC: Health care for viral hepatitis. Hepatology 2013;Conference 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases The Liver Meeting 2013. Washington, DC United States. Conference Publication:1195A-1196A. Available: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed14&AN=71238042

- 82.Perry R, Gard Read J, Chandler C. Understanding participants' perceptions of access to and satisfaction with chronic disease prevention programs. Health Educ Behav 2019;1090198118822710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thiessen K, Heaman M, Mignone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators related to implementation of regulated midwifery in Manitoba: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:1–22. 10.1186/s12913-016-1334-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Briones-Vozmediano E, Castellanos-Torres E, Goicolea I, et al. Challenges to detecting and addressing intimate partner violence among Roma women in Spain: perspectives of primary care providers. J Interpers Violence 2019:088626051987229. 10.1177/0886260519872299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chao Y-Y, Seo JY, Katigbak C, et al. Utilization of mental health services among older Chinese immigrants in New York City. Community Ment Health J 2020;56:1331–43. 10.1007/s10597-020-00570-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shewamene Z, Dune T, Smith CA. Use of traditional and complementary medicine for maternal health and wellbeing by African migrant women in Australia: a mixed method study. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020;20:60. 10.1186/s12906-020-2852-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Majaj L, Nassar M, De Allegri M. "It's not easy to acknowledge that I'm ill": a qualitative investigation into the health seeking behavior of rural Palestinian women. BMC Womens Health 2013;13:26. 10.1186/1472-6874-13-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez HR, Dobalian A. Provider and administrator experiences with providing HIV treatment and prevention services in rural areas. AIDS Educ Prev 2017;29:77–91. 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nowgesic EF, Access AT. Acceptance and adherence among urban Indigenous peoples living with HIV in Saskatchewan: the Indigenous red ribbon Storytelling study, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heidari P, Cross W, Weller C, et al. Rheumatologists' insight into medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Int J Rheum Dis 2019;22:1695–705. 10.1111/1756-185X.13660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robinson PG, Douglas GVA, Gibson BJ, et al. Remuneration of primary dental care in England: a qualitative framework analysis of perspectives of a new service delivery model incorporating incentives for improved access, quality and health outcomes. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031886. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Travers JL, Hirschman KB, Naylor MD. Adapting Andersen’s expanded behavioral model of health services use to include older adults receiving long-term services and supports. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:58. 10.1186/s12877-019-1405-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grodensky CA, Rosen DL, Blue CM, et al. Medicaid enrollment among prison inmates in a Non-expansion state: exploring predisposing, enabling, and need factors related to enrollment Pre-incarceration and Post-Release. J Urban Health 2018;95:454–66. 10.1007/s11524-018-0275-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12:80. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez Lyla M. Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations, 2012. Available: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf [Accessed 07 Jan 2020].

- 96.Chafe R. The value of qualitative description in health services and policy research. Hcpol 2017;12:12–18. 10.12927/hcpol.2017.25030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ritchie H, Roser M. Age structure, 2019. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/age-structure# [Accessed 02 Mar 2020].

- 98.Institute of Medicine . Retooling for an aging America: building the health care workforce. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Flick U, Ev K, Steinke I. What is Qualitative Research? And Introduction to the Field. : Flick U, Ev K, Steinke I, . A companion to qualitative research. London: SAGE, 2010: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Go VF-ling, Quan VM, Chung A, et al. Gender gaps, gender traps: sexual identity and vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases among women in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:467–81. 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00181-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sperber N, Andrews S, Voils C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to adoption of genomic services for colorectal care within the Veterans health administration. J Pers Med 2016;6:16. 10.3390/jpm6020016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mago A, MacEntee MI, Brondani M, et al. Anxiety and anger of homeless people coping with dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2018;46:225–30. 10.1111/cdoe.12363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Richards C. Women’s experiences with the follow-up system for cervical cancer in a developing country 2015;76. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge JP, Devaney J, et al. Priorities and strategies for improving disabled women's access to maternity services when they are affected by domestic abuse: a multi-method study using concept maps. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:350. 10.1186/s12884-015-0786-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee MH. Breast cancer screening behavior in Korean immigrant women in the United States, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Noh H. Terminally ill black elders: making the choice to receive hospice care, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045018supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-045018supp002.pdf (63.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-045018supp003.pdf (60.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-045018supp004.pdf (169.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.