Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, heart arrest, inflammation, intensive care units, myocardial infarction

Background:

Patients experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who remain comatose after initial resuscitation are at high risk of morbidity and mortality attributable to the ensuing post–cardiac arrest syndrome. Systemic inflammation constitutes a major component of post–cardiac arrest syndrome, and IL-6 (interleukin-6) levels are associated with post–cardiac arrest syndrome severity. The IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab could potentially dampen inflammation in post–cardiac arrest syndrome. The objective of the present trial was to determine the efficacy of tocilizumab to reduce systemic inflammation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of a presumed cardiac cause and thereby potentially mitigate organ injury.

Methods:

Eighty comatose patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were randomly assigned 1:1 in a double-blinded placebo-controlled trial to a single infusion of tocilizumab or placebo in addition to standard of care including targeted temperature management. Blood samples were sequentially drawn during the initial 72 hours. The primary end point was the reduction in C-reactive protein response from baseline until 72 hours in patients treated with tocilizumab evaluated by mixed-model analysis for a treatment-by-time interaction. Secondary end points (main) were the marker of inflammation: leukocytes; the markers of myocardial injury: creatine kinase myocardial band, troponin T, and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; and the marker of brain injury: neuron-specific enolase. These secondary end points were analyzed by mixed-model analysis.

Results:

The primary end point of reducing the C-reactive protein response by tocilizumab was achieved since there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction, P<0.0001, and a profound effect on C-reactive protein levels. Systemic inflammation was reduced by treatment with tocilizumab because both C-reactive protein and leukocyte levels were markedly reduced, tocilizumab versus placebo at 24 hours: –84% [–90%; –76%] and –34% [–46%; –19%], respectively, both P<0.001. Myocardial injury was also reduced, documented by reductions in creatine kinase myocardial band and troponin T; tocilizumab versus placebo at 12 hours: –36% [–54%; –11%] and –38% [–53%; –19%], respectively, both P<0.01. N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide was similarly reduced by active treatment; tocilizumab versus placebo at 48 hours: –65% [–80%; –41%], P<0.001. There were no differences in survival or neurological outcome.

Conclusions:

Treatment with tocilizumab resulted in a significant reduction in systemic inflammation and myocardial injury in comatose patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Registration:

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03863015.

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Systemic inflammation is a major component of the post–cardiac arrest syndrome that develops after resuscitation from cardiac arrest, and IL-6 (interleukin 6) is associated with severity of post–cardiac arrest syndrome and mortality.

In the present phase II trial, we investigated whether blocking the IL-6 signaling pathway with tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antibody, could lessen systemic inflammation and possibly mitigate organ injury in patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Tocilizumab greatly diminished the levels of C-reactive protein, an unspecific marker of inflammation, during the initial days after resuscitation, and it is important to note that this was accompanied by reductions in troponin T, creatine kinase myocardial band, and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

This trial demonstrates the feasibility of reducing systemic inflammation after cardiac arrest and shows an apparent cardioprotective effect as seen by reduced levels of biomarkers of myocardial injury and stress in patients treated with tocilizumab.

Further studies are needed to determine whether these findings translate into clinical benefits for the patients.

Patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) who remain comatose at hospital admission are at high risk of morbidity and mortality, and the overall 30-day mortality remains at ≈50%.1 This has been attributed to the post–cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS), which includes the 4 interacting components: systemic ischemia/reperfusion response, cerebral injury, myocardial dysfunction, and the persistent precipitating cause of the arrest.2 Despite emphasis on postresuscitation care by current guidelines,3,4 no specific therapies for mitigating PCAS have been implemented except for targeted temperature management.5 Consequently, research addressing specific components of PCAS is warranted. During cardiac arrest, patients are exposed to whole-body ischemia, which, after return of spontaneous circulation, is followed by reperfusion injury. Both ischemia and reperfusion injury trigger activation of inflammatory cascades leading to a systemic inflammatory response or sepsislike syndrome.6–9 High levels of inflammatory markers,9–11 including CRP (C-reactive protein)9 and IL-6 (interleukin-6),9 have been associated with an unfavorable outcome after OHCA, with IL-6 being associated with the severity of PCAS assessed by sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score in unconscious patients with OHCA.8 Levels of IL-6 have been shown to be independently associated with poor outcomes in unconscious patients with OHCA even after the adjustment for known risk markers.9

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine secreted by a variety of cells, including innate immune and endothelial cells, and the effects of IL-6 are abundant.12,13 IL-6 mediates fever and the acute phase response, increases vascular permeability, contributes to activation of the coagulation system, and can cause myocardial dysfunction.14 IL-6 is also involved in a range of pathological processes including tissue hypoxia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure,14 all of which represent parts of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. As for the ischemia-reperfusion injury in myocardial infarction, IL-6 has been associated with the magnitude of myocardial injury, mortality, and adverse events.15–17

Because of the effect of IL-6 in many inflammatory diseases, pharmacological therapy to limit the function of IL-6 has been developed, including both IL-6 receptor antibodies (IL-6RA) and antibodies directed against IL-6 itself.18 Tocilizumab is an IL-6RA approved for the treatment of various rheumatic diseases and chimeric antigen receptor T cell–induced cytokine release syndrome.14,18 In addition, tocilizumab has been suggested to have beneficial effects against some autoimmune neurological disorders.19–22 Furthermore, in patients presenting with non–ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction, a 1-hour infusion of 280 mg tocilizumab decreased the inflammatory response assessed by CRP levels, and further decreased myocardial injury assessed by troponin-T (TnT) levels23; it is important to note that no increased risk of adverse events was observed in patients receiving tocilizumab. Results are also awaited from a randomized clinical trial investigating the effects of tocilizumab on myocardial salvage after ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction.24

In the IMICA trial (IL-6 Inhibition for Modulating Inflammation After Cardiac Arrest), we therefore studied whether a single 1-hour infusion of the IL-6RA tocilizumab initiated as soon as possible after hospital admission will reduce the systemic inflammatory response syndrome–like response assessed by high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) and leukocyte levels in unconscious patients with OHCA and thereby mitigate organ injury.

Methods

Trial Design

The trial was an investigator-initiated, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, single-center, clinical phase II trial. After the successful completion of screening procedures, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to receive IL-6RA or placebo after hospital admission. Before initiation, the trial was registered at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03863015. A comprehensive study protocol with in-depth description of trial rationale, design, safety, and statistical analyses plan has previously been published.25 The full protocol and statistical code will be available on reasonable request. Participant-level data will similarly be made available on reasonable request after full publication and approvals from relevant authorities.

Patients and Randomization Procedure

Admitted patients with OHCA were screened for trial eligibility by the on-call physician and a dedicated team of research personnel, all medical doctors. Inclusion criteria (all required) were the following: OHCA of a presumed cardiac cause, age ≥18 years, unconsciousness (Glasgow Comma Scale<9), and sustained return of spontaneous circulation for >20 minutes. Exclusion criteria (all prohibitive) were the following: >240 minutes from return of spontaneous circulation until randomization, unwitnessed asystole, suspected or confirmed intracranial bleeding or stroke, pregnancy, temperature on admission <30 °C, persistent cardiogenic shock (defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg despite relevant interventions) that was not reversed within the inclusion window, any known disease making 180-day survival unlikely, known limitations in therapy, known prearrest Cerebral Performance Category of 3 to 4, known allergies to IL-6RA, known infections, and known hepatic cirrhosis.

Random assignments of eligible patients were performed using a web-based secure electronic Case Report System (Zenodotus eCRF). Blinding to the allocation sequence was upheld for all treating physicians and study coordinators throughout the trial.

Intervention and Concomitant Care

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive tocilizumab or placebo. Patients being allocated to IL-6RA received a 1-hour infusion of 8 mg of tocilizumab (RoActemra) per kg body weight (maximum dose 800 mg, ie, 40 mL of concentrate), the study drug was suspended in isotonic saline to a total volume of 100 mL. Patients being allocated to placebo received a 1-hour infusion of 100 mL of isotonic saline. The infusion of either IL-6RA or placebo was commenced in a blinded fashion at the earliest possible time after randomization.

During the study period, patients received standard of care, including sedation with either propofol or midazolam (in case of profound hemodynamic instability) and fentanyl, at least until the completion of targeted temperature management of 36 °C for 24 hours, vasopressors and inotropes as needed, prophylactic antibiotics (intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam or, in the case of β-lactam allergy, cefuroxime) and any additional treatment at the discretion of the treating physician.

Trial End Points

Primary Objective

The primary objective of the trial was to determine the efficacy of tocilizumab compared with placebo on reducing the CRP response in comatose patients resuscitated from OHCA as determined by the end point of daily hsCRP measurements from admission and until 72 hours. We would consider tocilizumab to have an effect on the CRP response, if there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction by mixed-model analysis (power calculation was based on a 30% reduction in CRP for the active group versus placebo; see Statistics). CRP was chosen as the primary end point because CRP levels were considered to reflect the biological effects of circulating IL-6, because IL-6 regulates CRP production.14 Accordingly, in this phase II trial, we rationalized that if CRP production was significantly reduced by treatment with tocilizumab, then the chosen dosage would also be sufficient in comatose patients resuscitated from OHCA to potentially allow for other IL-6–mediated effects to be present.

Secondary Objective

The secondary objective of the trial was to determine the effects of tocilizumab on the dampening of inflammation, cardioprotection, neuroprotection, clinical end points including intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, SOFA score (total and cardiovascular score26 on calendar days 1–3), hemodynamic data in the form of cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure from right heart catheter, survival and neurological outcome characterized by cerebral performance category and modified Rankin scale at 30, 90, and 180 days (reported as n [%] with a cerebral performance category ≥3 and modified Rankin scale ≥4),27 and safety, as well. The biomarkers measured were inflammation: hsCRP and leukocytes; cardioprotection: TnT, creatine kinase myocardial band (CKMB) representing myocardial infarction/injury, and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) representing myocardial stress; and neuroprotection: neuron-specific enolase (NSE).

Biomarker Measurement Techniques and Assays

hsCRP, leukocytes, TnT, CKMB, creatinine kinase, NT-proBNP, creatinine, and NSE were measured as routine biochemistry in a DS/EN ISO 15189 standardized laboratory by a COBAS 8000 (hsCRP, TnT, CKMB, creatinine kinase, NT-proBNP, creatinine, and NSE), and Sysmex XN (leukocytes); IL-6 was measured on EDTA samples from biobank that had not been thawed previously, using a BioRad 17-plex human cytokine assay. Biobank samples were spun at 20g for 10 minutes and plasma was then aliquoted and stored at –80 °C.

Approvals and Monitoring

Before study initiation, the trial protocol, written information, and consent forms were approved by the regional ethics committee of The Capital Region of Denmark (Approval No. H-18037286), and the Danish Medicines Agency (Approval No. 2018-002686-19). A data handling agreement was approved by the legal department of Rigshospitalet (Approval No. VD-2019-26). Because patients were unconscious at the time of screening, a legal surrogate was consulted for informed consent before inclusion in the trial according to national legislation. Patients’ next of kin were informed and asked for consent at the earliest opportunity, as were those patients who survived. A second legal surrogate was also consulted for all patients in the follow-up period.

The study was conducted in adherence to national and international standards of good clinical practice and was externally monitored by the national good clinical practice unit at the Copenhagen Good Clinical Practice center.

Safety

Patients were followed for 180 days after randomization for the occurrence of adverse events (AEs). The following categories of AE were registered: bleeding, infection, renal impairment (a patient requiring continuous renal replacement therapy or intermittent hemodialysis), electrolytes (hypo- or hyperkalemia), metabolic disorders (hypo- or hyperglycemia), arrhythmia, seizures, and other (including readmissions, death attributable to withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy, and other AEs not covered by specific categories). An AE that resulted in death was life-threatening, required prolonged hospitalization, or resulted in significant disability was classified as a serious adverse event (SAE). All SAEs were evaluated by the sponsor-investigator, including for the possibility of suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions in accordance with national legislation.

Statistics

The power calculation for the trial was based on a reduction in the primary end point, hsCRP of 30%, that is, 30% lower CRP levels in the active group versus placebo in the period after baseline/tocilizumab infusion.25 Tocilizumab has previously been shown to reduce hsCRP in patients with non–ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction with a median area under the hsCRP curve reduction of 52%.23 However, because the systemic inflammatory response in a non–ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction population is limited compared with an OHCA population,8,23 the assumption was made for a somewhat lesser reduction by tocilizumab in the present trial. A power of 0.81 would be achieved, assuming an α-level of 0.05, if 64 patients were included and data were available for all planned time points. Therefore, to account for mortality within the first 3 days, and blood samples missing, we decided to include 80 patients.

Reported results are based on the modified intention-to-treat population defined as all randomly assigned patients who received the intervention and for whom the next of kin did not refuse consent to the trial intervention and procedures. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS-Institute Inc), and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM). Markers of inflammation and cardioprotection were log2-transformed and analyzed by baseline corrected repeated measurement mixed models (SAS, PROC MIXED). These values are reported as predicted geometric means and confidence limits after antilog and as relative differences in percent for select group comparisons at specific time points on the basis of the results provided by “lsmeans” in PROC MIXED; observed values for these variables are presented in Figures I–V in the Data Supplement). By default, PROC MIXED estimates missing values based on maximum likelihood inference. For the primary end point (CRP), a prespecified limit of >5% missingness was set for when to perform multiple imputations. The remainder of continuous variables were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test and reported as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were analyzed with Fisher exact tests and reported as n (%); for mortality, we applied log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier estimator. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Recruitment and Patient Characteristics

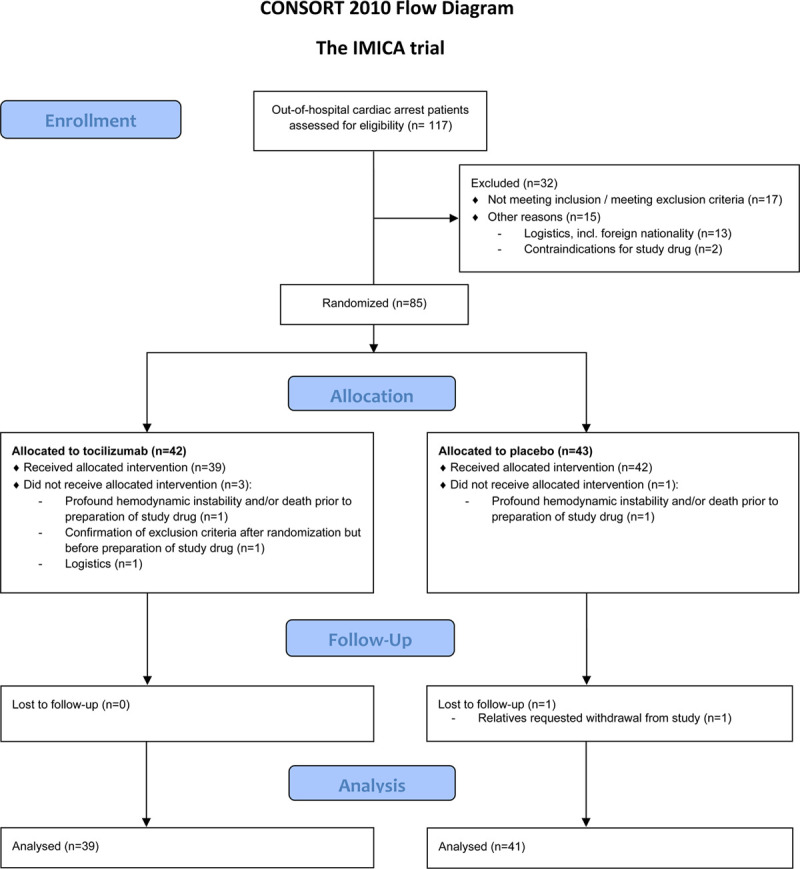

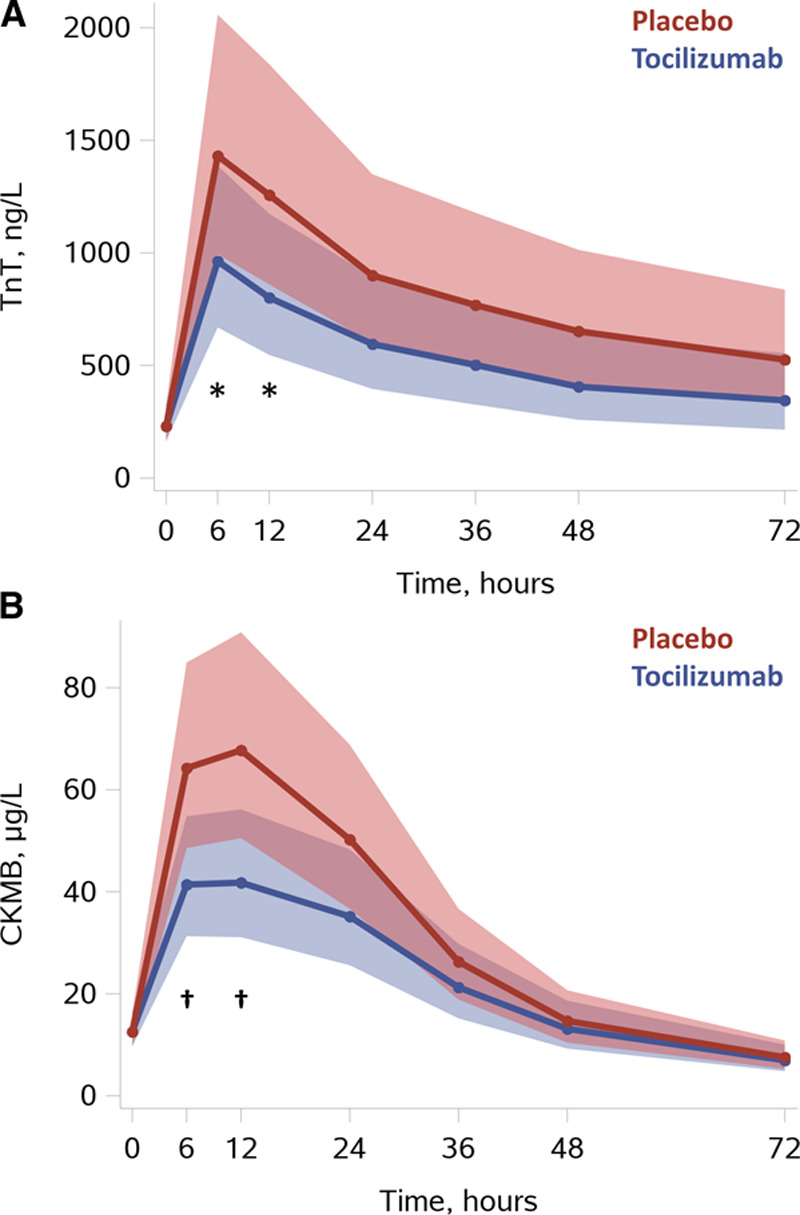

Between March 4 and December 20, 2019, we screened 117 consecutive patients admitted to the Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet after OHCA. Of these, 85 were randomly assigned, and ultimately 80 patients were included in the modified intention-to-treat population (see Figure 1 for consort diagram). There was a balanced randomization with 39 patients randomly assigned to treatment with tocilizumab and 41 assigned to placebo with no major differences in patient baseline characteristics (see Table 1). With respect to the completeness of the data, for the primary end point, data were available for 97.2% of all planned time points (311 available of 320 planned, which also includes projected sampling of patients who died before completion of the sampling period). For the secondary end points, inflammatory and cardiac markers, the completeness was as follows: leukocytes 97%, TnT 95%, CKMB 95%, and NT-proBNP 95%. Because the missingness of data for the primary end point was less than the prespecified limit that would prompt multiple imputations, such were not performed.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram. Adapted from Consort-Statement.org. All analyses were performed on the modified intention-to-treat population as depicted in the diagram. IMICA trial indicates IL-6 Inhibition for Modulating Inflammation After Cardiac Arrest; and incl., including.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

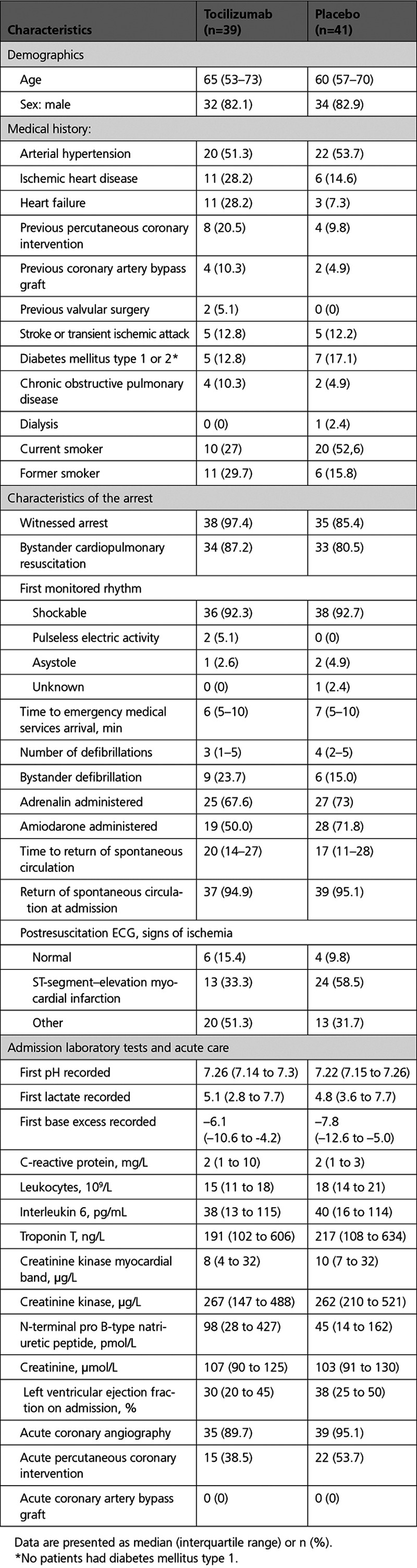

Systemic Inflammation

The primary end point of reducing the CRP response in patients treated with tocilizumab was achieved (Figure 2). In the tocilizumab group, CRP levels were reduced at 24 hours by 84% [90%; 76%] P<0.0001, at 48 hours by 94% [96%; 91%] P<0.0001, and at 72 hours by 96% [97%; 94%] P<0.0001; P<0.0001 for treatment-by-time interaction. Leukocytes were also reduced at 24 hours by 34% [46%; 19%] P = 0.0001, and at 48 hours by 23% [36%; 8%] P=0.004; P=0.0005 for treatment-by-time interaction.

Figure 2.

Systemic inflammation. A, CRP. B, Leukocytes. Results are presented as means with [95% confidence limit] based on predicted values from linear mixed-model analysis with baseline correction (PROC MIXED, SAS Institute Inc). *P≤0.0001, †P=0.004 for tocilizumab vs placebo at corresponding time points using the interaction term “group*time.” For additional illustrations of observed values please see Figures I and II in the Data Supplement. CRP indicates C-reactive protein.

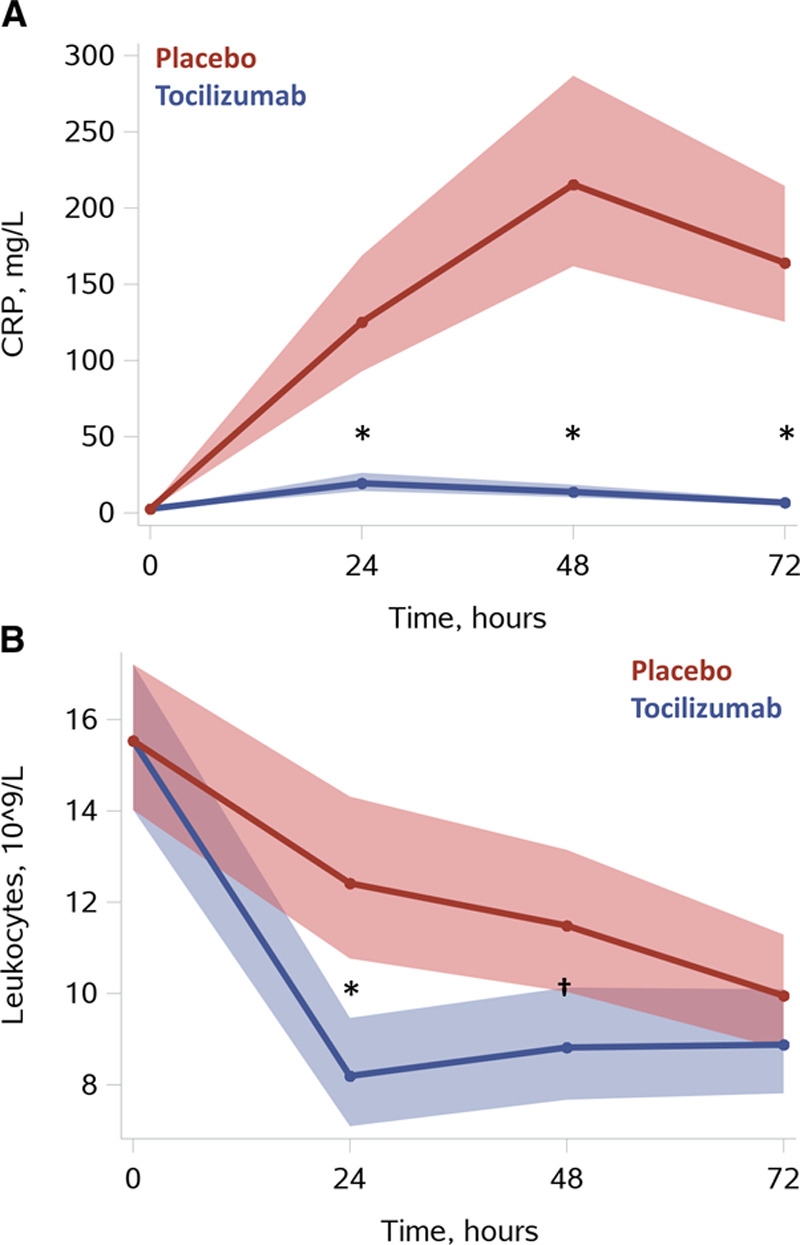

Myocardial Infarction/Injury and Myocardial Stress

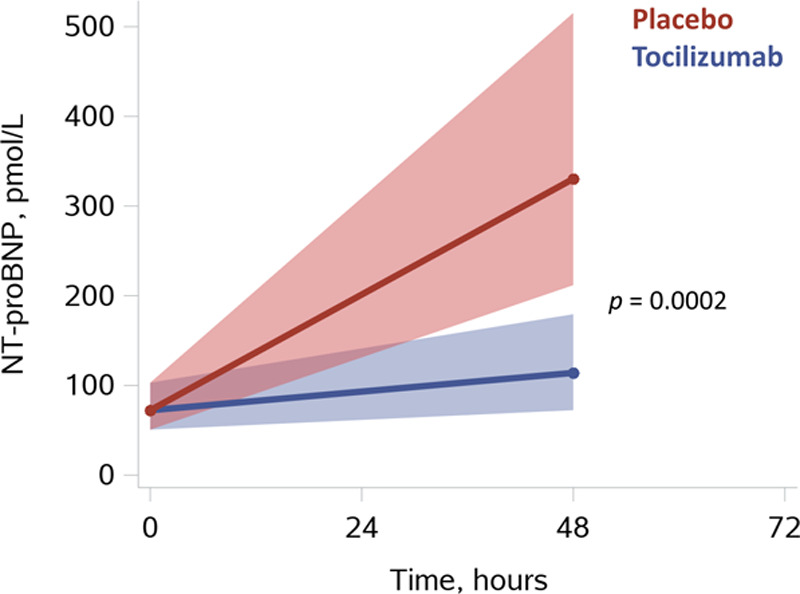

TnT and CKMB were both significantly reduced at 6 and 12 hours in the tocilizumab group (Figure 3). TnT was reduced at 6 hours by 33% [47%; 14%] P=0.0017, and at 12 hours by 36% [54%; 11%] P=0.0082, P=0.09 for treatment-by-time interaction. CKMB was reduced at 6 hours by 36% [47%; 21%] P<0.0001, and at 12 hours by 38% [53%; 19%] P=0.0006; P=0.0035 for treatment-by-time interaction. Furthermore, there was a trend for lower levels of both TnT and CKMB in the tocilizumab group at 24 hours (P=0.07 and P=0.05, respectively). Last, NT-proBNP was reduced by 65% [–80%; –41%] P=0.0002 in the tocilizumab group at 48 hours (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Myocardial infarction/injury. A, TnT. B. CKMB. Results are presented as means with [95% confidence limit] based on predicted values from linear mixed-model analysis with baseline correction (PROC MIXED, SAS Institute Inc). *P<0.01, †P<0.001 for tocilizumab vs placebo at corresponding time points using the interaction term “group*time.” For additional illustrations of observed values please see Figures III and IV in the Data Supplement. CKMB indicates creatine kinase myocardial band; and TnT, troponin T.

Figure 4.

Myocardial stress: NT-proBNP. Results are presented as means with [95% confidence limit] based on predicted values from linear mixed-model analysis with baseline correction (PROC MIXED, SAS Institute Inc). Shown P value is for tocilizumab vs placebo at 48 hours using the interaction term “group*time.” For additional illustrations of observed values please see Figure V in the Data Supplement. NT-proBNP indicates N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

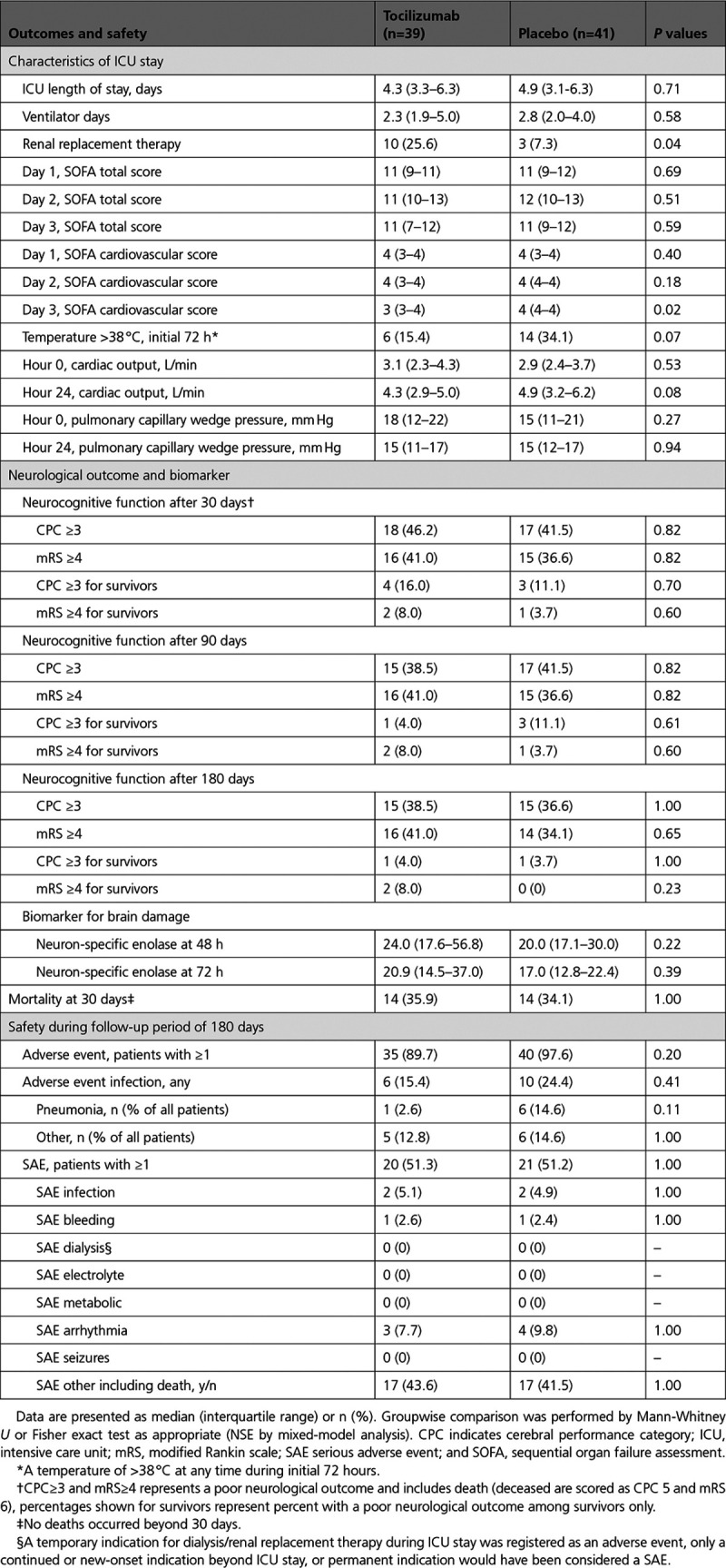

Safety

The frequency of patients experiencing at least 1 AE or SAE was equal in the 2 groups (see Table 2), with 90% experiencing an AE and 51% experiencing an SAE in the tocilizumab group, and, in the placebo group, this was 98% and 51%, P=0.20 and P=1, respectively. Specifically, there was no group difference with respect to the frequency of an AE of infection (15% for tocilizumab and 24% for placebo, P=0.41). Nor was there a significant difference in the overall fraction of patients with an AE of infection classified as pneumonia. Last, there was no group difference either in the frequency of patients experiencing any of the prespecified SAE categories.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes and Safety

Clinical Outcomes

There were no group differences with respect to ICU length of stay, ventilator days, or SOFA total score on days 1 to 3. However, the SOFA Cardiovascular score was slightly lower in the tocilizumab group on day 3, with no difference on days 1 and 2. Also, there was a trend toward a lesser occurrence of a temperature >38 °C during the initial 72 hours in the tocilizumab group. Cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, which approximates left atrial pressure, did not differ between groups at 0 or 24 hours. The frequency of patients receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT) during ICU stay was 10 in the tocilizumab group and 3 for placebo, P=0.04 (a new-onset indication for RRT during ICU stay was registered as an AE). The mortality for patients receiving RRT in the ICU was 7 of 10 for tocilizumab and 3 of 3 for placebo. One patient in the placebo group was treated with peritoneal dialysis before OHCA. Surviving patients all regained native renal function and were discharged without dialysis from the ICU.

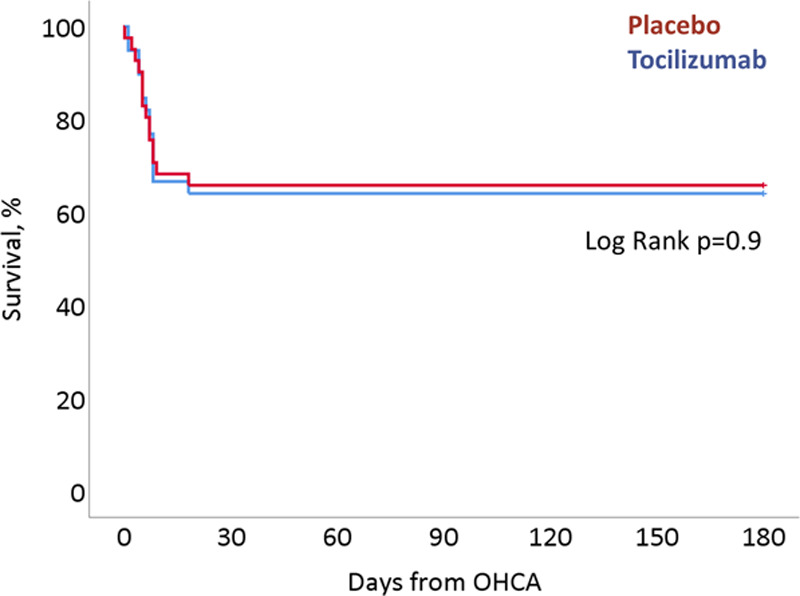

Mortality rates were similar in both groups at 30, 90, and 180 days after OHCA, with all deaths having occurred before 30 days and before discharge in both groups (see Figure 5). Likewise, there was no significant group difference in the frequencies of death or survival with an unfavorable neurological outcome, defined as a cerebral performance category of ≥3 or a modified Rankin scale ≥4, at neither of the investigated time points. The marker of neuronal damage, NSE, did not differ between groups at the measured time points of 48 and 72 hours, P=0.22 and P=0.39, respectively.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier plot. Survival stratified by treatment arm from randomization until the end of the follow-up period of 180 days. OHCA indicates out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Discussion

The primary objective of the trial, a reduction in the CRP response in comatose patients resuscitated from OHCA by treatment with tocilizumab, was achieved. Furthermore, the tocilizumab group experienced a dampening of systemic inflammation as demonstrated by a reduction in leukocytes, and there was an apparent cardioprotective effect with a reduction in myocardial injury and myocardial stress. Also, in the tocilizumab group there was a slightly lower SOFA Cardiovascular score on day 3, and a trend for fewer patients experiencing a temperature >38 °C. There were no group differences in mortality, the distribution of unfavorable neurological outcomes, or in the predefined safety parameters.

In the present trial, CRP levels were dramatically reduced, and leukocytes approached normal values faster in patients treated with tocilizumab than with placebo. Although reduction in CRP in itself is not considered a therapeutic target, the marked reduction in CRP levels by IL-6 receptor blockage with tocilizumab illustrates that the dosage was of sufficient magnitude to effectively block the IL-6 receptors and limit the synthesis of acute-phase proteins in the liver, including CRP, even after resuscitation from OHCA.14 Before initiating the trial, this was considered a prerequisite for other IL-6–mediated effects to also be sufficiently lessened. Henceforth, the reduction in CRP should rightfully not be considered a reduction in inflammation, although CRP has been suggested to be active in inflammatory processes.28 However, the accompanying reduction in leukocytes suggests that there was an anti-inflammatory effect of IL-6 receptor blockage. This was further illustrated by the trend for a lesser occurrence in the tocilizumab group of a temperature >38 °C after cessation of targeted temperature management, which is a known entity that has been termed “rebound pyrexia.”29

Patients in the tocilizumab group had a substantial lowering of the markers of myocardial injury, because both TnT and CKMB peaked at lower levels than those seen for placebo. A previous study in patients with non–ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction similarly demonstrated a reduction in TnT release and a lowering of CRP when patients were given an infusion of tocilizumab before coronary angiography.23 Although the exact mechanism is unknown, Kleveland and associates speculated that the reduction in TnT release was related to a reduction in the ischemia/reperfusion injury by treatment with tocilizumab. The levels of TnT and especially CRP in that study were comparatively lower than in the present trial, and, for our patients, the study drug infusion was generally not initiated until ICU admission after coronary angiography (if such was indicated). Ischemia/reperfusion injury is also an important component of PCAS, but here it relates to the whole body and not just the heart.2 In this context, inhaled Xenon as an adjunct to standard of care after OHCA has also been demonstrated to reduce myocardial injury as evaluated by TnT release, possibly by means of a protective postconditioning effect.30 In the present trial, the cardioprotective effect was also illustrated by the finding of a markedly reduced level of NT-proBNP in patients treated with tocilizumab. Whether this is related to a diminished ischemia/reperfusion injury or to another beneficial effect is unknown at the present. Nonetheless, NT-proBNP has previously been shown in a larger study to be predictive of death from a hemodynamic cause after OHCA.31

We did not find an effect of treatment on ICU length of stay or total SOFA scores for the initial 3 days. The SOFA Cardiovascular score was slightly lower in the tocilizumab group on day 3, illustrating more stable hemodynamics with lesser vasopressor requirements. However, more patients received RRT during ICU stay in the tocilizumab group than in the placebo group. Whether this is a chance finding or is because of an unforeseen side effect of tocilizumab in this setting remains unknown, but none of the survivors had a need for dialysis after ICU discharge, and observational data suggest that tocilizumab as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis is safe in patients with renal insufficiency.32 Also, in a recent study in a similar patient cohort from our cardiac ICU, the frequency of RRT in the active and placebo group was 24% and 23%, respectively, and thus of the same magnitude as seen in the tocilizumab group in the present study.33

Although the study was not powered to detect the effects on clinical end points, no differences in mortality, unfavorable neurological outcomes, or a surrogate marker for cerebral injury (NSE) were found. There is no concluding evidence on whether tocilizumab crosses the blood-brain barrier in humans, neither in health nor during illness. However, an animal study in healthy monkeys revealed a low degree of penetration of the blood-brain barrier after intravenous administration.34 Yet, tocilizumab has been suggested as a possible treatment of autoimmune central nerve system diseases.19–21

There were no significant group differences in frequencies of patients experiencing a SAE or in patients with AE infection. The observation of no increased risk of infections is a vital finding in these critically ill patients and is in line with a recent study in patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) treated with tocilizumab.35 This contrasts with previous findings where treatment with tocilizumab was associated with increased occurrence of infections.36 Of note, however, all patients in the present trial were treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infections.37

In summary, resuscitated OHCA is associated with a systemic inflammatory response, the magnitude of which has been associated with increased mortality and poor neurological outcome. In the present trial, inhibiting the IL-6–mediated immune response by infusion of tocilizumab reduced systemic inflammation and exerted apparent cardioprotective effects as evaluated by biomarkers. The trial was not powered to detect changes in survival or neurological outcome, and nor did we find a difference in mortality or unfavorable neurological outcomes. For safety aspects, however, this does seem reassuring in conjunction with the finding of no significant differences in the occurrence of infections.

Limitations

This trial, which is to be considered a phase II trial, was conducted at a single center and was of limited size, not powered to detect possible group differences in mortality or neurological outcome. In addition, because all patients in the trial had experienced a cardiac arrest of presumed cardiac cause, as per the inclusion criteria, and the vast majority of patients had an initial shockable rhythm, the generalizability to noncardiac causes or initial nonshockable rhythms can be uncertain.

Further studies are needed before evaluating if treatment with tocilizumab after OHCA confers a clinical benefit.

Conclusions

Treatment with tocilizumab resulted in a significant reduction in systemic inflammation and myocardial injury in comatose patients resuscitated from OHCA. Further studies are warranted to evaluate if tocilizumab or similar agents should be implemented as standard of care in this setting.

Sources of Funding

The study was supported by funding from: The Danish Heart Foundation (Reference No. 19-R135-A9302-22125), “Region Hovedstadens Forskningsfond til sundhedsforskning” (Capital Region Research Foundation, Denmark; Reference No. A6030), “Hjertecenterets Forskningsudvalg” (The Heart Center Research Council, Rigshospitalet), NovoNordisk Foundation (unrestricted research grant for Dr Kjaergaard, NNF17OC0028706), Lundbeck Foundation (Reference No. R186-2015-2132).

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Materials

Data Supplement Figures I–V

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Sources of Funding, see page 1850

Continuing medical education (CME) credit is available for this article. Go to http://cme.ahajournals.org to take the quiz.

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.053318.

Contributor Information

Sebastian Wiberg, Email: sebastian.christoph.wiberg@regionh.dk.

Johannes Grand, Email: johannes.grand@regionh.dk.

Anna Sina Pettersson Meyer, Email: martin.as.meyer@gmail.com.

Laust Emil Roelsgaard Obling, Email: laust.emil.roelsgaard.obling.01@regionh.dk.

Martin Frydland, Email: martin.steen.frydland.01@regionh.dk.

Jakob Hartvig Thomsen, Email: jakob.hartvig.thomsen.01@regionh.dk.

Jakob Josiassen, Email: jakob.josiassen@regionh.dk.

Jacob Eifer Møller, Email: jacob.moeller@regionh.dk.

Jesper Kjaergaard, Email: jesper.kjaergaard.05@regionh.dk.

Christian Hassager, Email: Christian.Hassager@regionh.dk.

References

- 1.Søholm H, Wachtell K, Nielsen SL, Bro-Jeppesen J, Pedersen F, Wanscher M, Boesgaard S, Møller JE, Hassager C, Kjaergaard J. Tertiary centres have improved survival compared to other hospitals in the Copenhagen area after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Böttiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RSB, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC, et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication a consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 2008;118:2452–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, Geocadin RG, Golan E, Kern KB, Leary M, Meurer WJ, Peberdy MA, Thompson TM, et al. Part 8: post–cardiac arrest care. Circulation. 2015;132:S463–S482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Moulaert VR, Deakin CD, Bottiger BW, Friberg H, Sunde K, Sandroni C. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines for Post-resuscitation Care 2015: Section 5 of the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation. 2015;95:202–222. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan JP, Morley PT, Hoek TLV, Hickey RW. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: an advisory statement by the Advanced Life Support Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 2003;108:118–121. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079019.02601.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adrie C, Adib-Conquy M, Laurent I, Monchi M, Vinsonneau C, Fitting C, Fraisse F, Dinh-Xuan AT, Carli P, Spaulding C, et al. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation after cardiac arrest as a “sepsis-like” syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106:562–568. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023891.80661.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adrie C, Laurent I, Monchi M, Cariou A, Dhainaou JF, Spaulding C. Postresuscitation disease after cardiac arrest: a sepsis-like syndrome? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:208–212. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000126090.06275.fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bro-Jeppesen J, Kjaergaard J, Wanscher M, Nielsen N, Friberg H, Bjerre M, Hassager C. The inflammatory response after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is not modified by targeted temperature management at 33 °C or 36 °C. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1480–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bro-Jeppesen J, Kjaergaard J, Wanscher M, Nielsen N, Friberg H, Bjerre M, Hassager C. Systemic inflammatory response and potential prognostic implications after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a substudy of the Target Temperature Management Trial. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1223–1232. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fries M, Kunz D, Gressner AM, Rossaint R, Kuhlen R. Procalcitonin serum levels after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2003;59:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00164-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stammet P, Devaux Y, Azuaje F, Werer C, Lorang C, Gilson G, Max M. Assessment of procalcitonin to predict outcome in hypothermia-treated patients after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Res Pract. 2011;2011:631062. doi: 10.1155/2011/631062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a016295. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uciechowski P, Dempke WCM. Interleukin-6: a masterplayer in the cytokine network. Oncology. 2020;98:131–137. doi: 10.1159/000505099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Interleukin (IL-6) immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a028456. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Cuenca Á, Manzano-Fernández S, Lip GY, Casas T, Sánchez-Martínez M, Mateo-Martínez A, Pérez-Berbel P, Martínez J, Hernández-Romero D, Romero Aniorte AI, et al. Interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein for the prediction of outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2013;66:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawa Y, Ichikawa H, Kagisaki K, Ohata T, Matsuda H. Interleukin-6 derived from hypoxic myocytes promotes neutrophil-mediated reperfusion injury in myocardium. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:511–517. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamani P, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Rifai N, Bao W, Libby P, Ganz P, Kinlay S; Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) Study Investigators. Inflammatory biomarkers, death, and recurrent nonfatal coronary events after an acute coronary syndrome in the MIRACL study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e003103. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine Storm. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2255–2273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2026131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araki M, Matsuoka T, Miyamoto K, Kusunoki S, Okamoto T, Murata M, Miyake S, Aranami T, Yamamura T. Efficacy of the anti-IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab in neuromyelitis optica: a pilot study. Neurology. 2014;82:1302–1306. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayzenberg I, Kleiter I, Schröder A, Hellwig K, Chan A, Yamamura T, Gold R. Interleukin 6 receptor blockade in patients with neuromyelitis optica nonresponsive to anti-CD20 therapy. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:394–397. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee WJ, Lee ST, Moon J, Sunwoo JS, Byun JI, Lim JA, Kim TJ, Shin YW, Lee KJ, Jun JS, et al. Tocilizumab in autoimmune encephalitis refractory to rituximab: an institutional cohort study. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13:824–832. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0442-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ringelstein M, Ayzenberg I, Harmel J, Lauenstein AS, Lensch E, Stögbauer F, Hellwig K, Ellrichmann G, Stettner M, Chan A, et al. Long-term therapy with interleukin 6 receptor blockade in highly active neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:756–763. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleveland O, Kunszt G, Bratlie M, Ueland T, Broch K, Holte E, Michelsen AE, Bendz B, Amundsen BH, Espevik T, et al. Effect of a single dose of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab on inflammation and troponin T release in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2406–2413. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anstensrud AK, Woxholt S, Sharma K, Broch K, Bendz B, Aakhus S, Ueland T, Amundsen BH, Damås JK, Hopp E.Rationale for the ASSAIL-MI-trial: a randomised controlled trial designed to assess the effect of tocilizumab on myocardial salvage in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Open Heart. 2019;6:e001108. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2019-001108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer MAS, Wiberg S, Grand J, Kjaergaard J, Hassager C. Interleukin-6 Receptor Antibodies for Modulating the Systemic Inflammatory Response after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (IMICA): study protocol for a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, single-center, randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21:868. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04783-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Geocadin RG, Callaway CW, Lazar RM, Donnino MW, Nadkarni VM, Abella BS, Adrie C, Berg RA, et al. ; American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Primary outcomes for resuscitation science studies: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:2158–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182340239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leary M, Grossestreuer AV, Iannacone S, Gonzalez M, Shofer FS, Povey C, Wendell G, Archer SE, Gaieski DF, Abella BS. Pyrexia and neurologic outcomes after therapeutic hypothermia for cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arola O, Saraste A, Laitio R, Airaksinen J, Hynninen M, Bäcklund M, Ylikoski E, Wennervirta J, Pietilä M, Roine RO, et al. ; Xe-HYPOTHECA Study Group. Inhaled xenon attenuates myocardial damage in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Xe-Hypotheca trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2652–2660. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frydland M, Kjaergaard J, Erlinge D, Stammet P, Nielsen N, Wanscher M, Pellis T, Friberg H, Hovdenes J, Horn J, et al. Usefulness of serum B-type natriuretic peptide levels in comatose patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to predict outcome. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori S, Yoshitama T, Hidaka T, Hirakata N, Ueki Y. Effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and renal insufficiency: a real-life registry study in Japan (the ACTRA-RI study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:627–630. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer ASP, Johansson PI, Kjaergaard J, Frydland M, Meyer MAS, Henriksen HH, Thomsen JH, Wiberg SC, Hassager C, Ostrowski SR. “Endothelial Dysfunction in Resuscitated Cardiac Arrest (ENDO-RCA): Safety and efficacy of low-dose Iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue, in addition to standard therapy, as compared to standard therapy alone, in post-cardiac-arrest-syndrome patients.” Am Heart J. 2020;219:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nellan A, McCully CML, Cruz Garcia R, Jayaprakash N, Widemann BC, Lee DW, Warren KE. Improved CNS exposure to tocilizumab after cerebrospinal fluid compared to intravenous administration in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2018;132:662–666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-846428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, Fernandes AD, Harvey L, Foulkes AS, Horick NK, Healy BC, Shah R, Bensaci AM, et al. ; BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial Investigators. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, Ramos-Remus C, Rovensky J, Alecock E, Woodworth T, Alten R; OPTION Investigators. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:987–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.François B, Cariou A, Clere-Jehl R, Dequin PF, Renon-Carron F, Daix T, Guitton C, Deye N, Legriel S, Plantefève G, et al. ; CRICS-TRIGGERSEP Network and the ANTHARTIC Study Group. Prevention of early ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1831–1842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.