Abstract

Background

In an attempt to improve low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) level control in patients ineffectively treated with statins, we evaluated the effectiveness of a fixed-dose combination (FDC) of 10 mg rosuvastatin and ezetimibe and its relation to the timing of drug administration.

Methods

A randomized, open label, single center, crossover study involving 83 patients with coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolemia with baseline LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. In arm I the FDC drug was administered in the morning for 6 weeks, then in the evening for the following 6 weeks and vice versa in arm II. The primary endpoint was the change in LDL-C after 6 and 12 weeks.

Results

The median LDL-C concentration at baseline, after 6 and 12 weeks respectively was: 98.10 mg/dL (Q1;Q3: 85.10;116.80), 63.14 mg/dL (50.70;77.10) and 59.40 mg/dL (49.00;73.30); p < 0.001. LDL-C levels were similar regardless of the timing of drug administration (morning 62.50 mg/dL [50.70;76.00] vs. evening 59.70 mg/dL [48.20;73.80]; p = 0.259], in both time points: 6 week: 63.15 mg/dL (50.75;80.65) vs. 63.40 mg/dL (50.60;74.00), p = 0.775; and 12 week: 62.00 mg/dL (50.20;74.40) vs. 59.05 mg/dL (47.65;66.05), p = 0.362. The absolute change in LDL-C concentration for the morning vs. evening drug administration was — 6 week: −34.6 mg/dL (−56.55; −19.85) (−34.87%) vs. −31.10 mg/dL (−44.20; −16.00) (−35.87%) (p not significant); 12. week: −34.20 mg/dL (−47.8; −19.0) (−37.12%) vs. −37.20 mg/dL (−65.55; −23.85) (−40.06%) (p not significant). The therapy was safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

Fixed-dose combination of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe significantly and permanently decreases LDL-C regardless of the timing of drug administration.

Keywords: hypercholesterolemia, fixed-dose, secondary prevention, timing of administration, adherence, apolipoprotein B, lipoprotein(a)

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the most common single cause of death worldwide [1]. Hypercholesterolemia constitutes one of its major risk factors [2]. According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) 2016 guidelines for the management of dyslipidemias, the therapeutic target for low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) is < 70 mg/dL (< 1.8 mmol/L) [1, 3]. The first line treatment of hypercholesterolemia is statin therapy [3]. However, when the therapeutic target of LDL-C is not achieved, the addition of cholesterol absorption inhibitor — ezetimibe — to statin therapy is recommended [3, 4]. Unfortunately, lipid-lowering therapy is discontinued in a high percentage of patients with CAD [5]. One year after myocardial infarction (MI) only approximately 50% of patients report persistent use of statins [6, 7]. Furthermore, even when patients follow the recommendations and continue statin therapy, only a minority obtains optimal level of LDL-C [8, 9].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of hypercholesterolemia treatment with rosuvastatin and ezetimibe in patients ineffectively treated with statin monotherapy. Also under investigation was whether the timing (morning vs. evening) of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe administration affects their efficacy.

Methods

Study design and population

The study was designed as a randomized, open-label, single-center, crossover study. It was conducted in accordance with the principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and aimed to evaluate: the effectiveness of combined therapy with rosuvastatin and ezetimibe for hypercholesterolemia in patients with inadequate LDL-C control on statins alone, and to determine whether the timing of drug administration influences their efficacy (Clinical-Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02772640). The study was approved by local institutional review board (The Ethics Committee of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Poland). All participants signed informed consent prior to the performance of any investigational procedures. Key inclusion criteria included: diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia, defined according to the 2016 European guidelines [3], ineffectively treated for at least 6 weeks with statins. Patients eligible for the study had LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Major exclusion criteria included: active liver disease; unexplained persistent increase in serum transaminases activity (i.e. > 3-fold higher than the upper reference limit [URL]); myopathy; activity of creatine kinase (CK) > 5-fold higher than the URL. The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria has been previously published [10].

Patients hospitalized at the Department of Cardiology, Dr. Antoni Jurasz University Hospital No. 1 in Bydgoszcz, Poland, between the years 2016 and 2018 were screened, and if eligible, were enrolled in the study. The diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia was confirmed based on the lipid profile assessed during hospitalization. Patients with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL, despite having a 6-week statin monotherapy, were enrolled. After enrollment, all participants were randomly assigned to one of two study arms using Random Allocation Software 1.0. The study drug was a fixed dose combination (FDC) of rosuvastatin 10 mg and ezetimibe 10 mg formulated as capsules (Rosulip plus by Egis). In arm I, the study drug was administered in the morning (8:00 am) for 6 weeks and then in the evening (8:00 pm) for the next 6 weeks. In arm II, patients were receiving the study drug in the evening (8:00 pm) for the first 6 weeks and then in the morning (8:00 am) for the following 6 weeks. All patients received the study drug free of charge over the entire observational period. The remaining medications were as recommended by the ESC guidelines accordingly to specific comorbidities. Clinical evaluation and blood sampling were performed on the day of randomization and after 6 and 12 weeks of treatment. In a subgroup of patients, blood samples were collected twice a day: 12 and 24 hours after the last dose of study drug during follow-up visits.

Endpoints

The primary outcome was defined as change in LDL-C after 6 and 12 weeks of the investigated therapy, with respect to timing of the study drug administration. The secondary endpoints included: change in total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) levels after 6 and 12 weeks (also with respect to timing of the study drug administration), concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), creatine kinase (CK), apolipoprotein B (apoB) and lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) at baseline and after 6 and 12 weeks of the therapy.

Blood collection and laboratory measurements

A detailed description of blood collection and laboratory measurements has been previously published [10]. Routine laboratory measurements were performed in fresh serum (basic lipid profile [TC, TG, LDL-C], AST, ALT, CK). The remaining serum was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until assayed for hs-CRP, apoB, Lp(a). All measurements (except for CRP) were performed using the Horiba ABX Pentra 400 analyzer (Horiba ABX, Montpellier, France). LDL-C was measured directly. CRP was measured using the Alinity c analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA) with the Alinity c CRP Vario High Sensitivity assay for the quantitative, immunoturbidimetric determination of CRP with a limit of detection of 0.4 mg/L. Laboratory measurements were performed at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Collegium Medicum, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistica 13.0 package (StatSoft, Tulsa, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test demonstrated that the investigated continuous variables were not normally distributed. Therefore, continuous variables were presented as median and quartiles (lower and upper) and nonparametric tests (the Mann-Whitney unpaired rank sum test, the Wilcoxon signed rank test, and the Friedman ANOVA) were used for statistical analysis. The χ2 test was used for comparisons of qualitative variables. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Eighty-three patients were enrolled into the study. The mean age was 64.6 ± 8.7 years. The majority of included patients had a documented history of CAD (93.98%) and 62.7% had prior MI. There were no differences between patients in both study arms (Table 1). At the time of enrollment, the majority of patients were treated with atorvastatin (72.29%), 16.87% used rosuvastatin, and the rest were treated with simvastatin.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study patients and comparison between study arms.

| Population | N = 83 patients | Group I (40 patients) | Group II (43 patients) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 20 (24.1%) | 7 (17.5%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.1753 |

| Age [years] | 64.6 ± 8.7 | 64.6 ± 7.9 | 64.6 ± 9.4 | 0.9675 |

| Post myocardial infarction | 52 (62.7%) | 21 (52.5%) | 31 (72.%) | 0.0867 |

| Hypertension | 58 (69.9%) | 24 (60.0%) | 34 (70.1%) | 0.0814 |

| Heart failure | 30 (36.2%) | 12 (30.0%) | 18 (41.9%) | 0.2977 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (36.5%) | 9 (22.5%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.4652 |

Primary endpoint

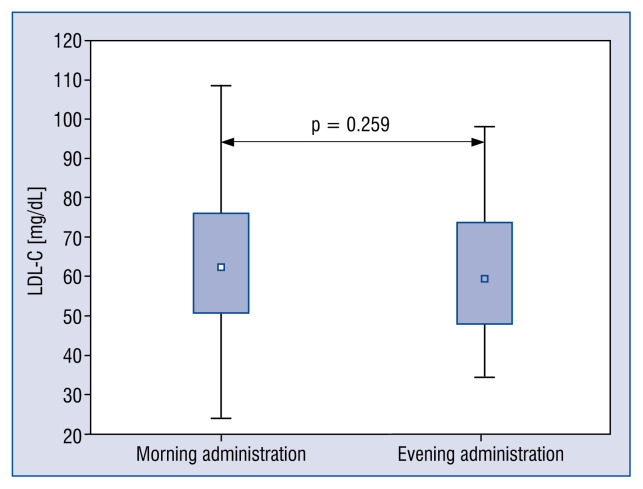

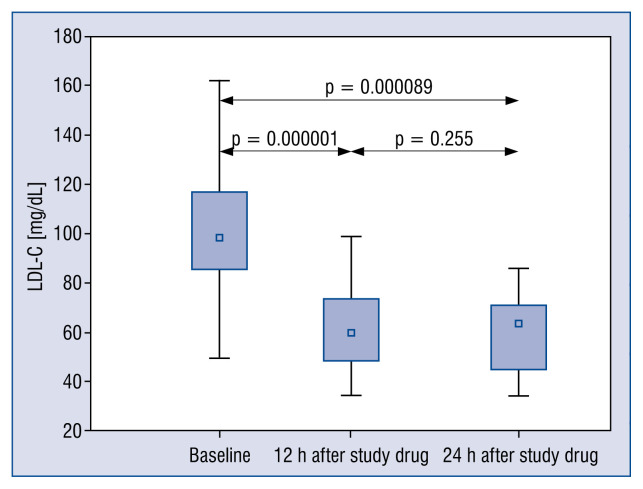

After 6 weeks of therapy with the study drug, there was a significant reduction in LDL-C (median: 98.10 mg/dL; interquartile distribution [Q1;Q3]: 85.10;116.80 vs. 63.14 mg/dL; 50.70;77.10; p < 0.001). The decrease was constant over time after 12 weeks (63.14 mg/dL [50.70;77.10] vs. 59.40 mg/dL [49.00;73.30]; p = 0.077; Fig. 1). There was no significant difference between LDL-C with respect to the timing of the study drug administration (morning: 62.50 mg/dL [50.70;76.00] vs. evening: 59.70 mg/dL [48.20;73.80]; p = 0.259; Fig. 2), in both time points after 6 and 12 weeks, respectively (af ter 6 weeks: 63.15 mg/dL [50.75;80.65] vs. 63.40 mg/dL [50.60;74.00]; p = 0.775); af ter 12 weeks: 62.00 mg/dL [50.20;74.40] vs. 59.05 mg/dL [47.65;66.05]; p = 0.362). After 6 weeks the absolute change in LDL-C was −34.6 (−56.55; −19.85) (−34.87% [−46.83; −22.69]) for the morning administration of the study drug, and −31.10 (−44.20; −16.00) (−35.87% [−47.87; −17.96]) (p not significant) for the evening administration. Twelve weeks after, the absolute change in LDL-C was −34.20 (−47.8; −19.0) (−37.12% [−46.18; −20.62]) for the morning and −37.20 (−65.55; −23.85) (40.06% [−55.24;−23.33]) (p not significant) for the evening administration, respectively.

Figure 1.

Primary endpoint: Change in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) after 6 and 12 weeks of therapy.

Figure 2.

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration depending on time of day of study drug administration.

In a subgroup of 20 patients additional measurements were performed at 12 and 24 hours after the last dose of the study drug. In patients receiving the study drug in the morning, LDL-C measured in the evening (i.e. 12 h after the last dose) were significantly lower than the next morning (i.e. 24 h after the last dose of the study drug) [52 mg/dL (46.95;75.85) vs. 64.95 mg/dL (50.35;77.05); p=0.019] (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, both results were significantly lower compared with baseline LDL-C [12 h: 93.5 mg/dL (86.15;113.4) vs. 52 mg/dL (46.95;75.85); p=0.000089; 24 h: 93.5 mg/dL (86.15;113.4) vs. 64.95 mg/dL (50.35;77.05); p<0.000001]. Among patients taking the drug in the evening, LDL-C measured next morning (i.e. 12 h after the last dose of the study drug) was comparable with the LDL-C level measured in the evening the same day (i.e. 24 h after the last dose of the study drug) [61.05 mg/dL (45.85;74.05) vs. 63.35 mg/dL (44.75;71.00); p = 0.255] (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Morning administration of the study drug: change in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration depending of time of testing.

Figure 4.

Evening administration of the study drug: change in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration depending of time of testing.

Secondary endpoints

Total cholesterol was significantly lower after 6 weeks of therapy with the study drug and this effect was stable throughout the observational period (Fig. 5). Moreover, the effect was independent of the timing of study drug administration (Table 2). Similar results were achieved for TG. There was a significant reduction in TG concentration compared with baseline values (Table 2), and the outcome was again independent of the timing of the study drug administration (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Change in total cholesterol (TC) concentration after 6 and 12 weeks of therapy.

Table 2.

Secondary endpoints.

| Secondary endpoints | Baseline [median] | Q1;Q3 | After 6 weeks [median] | Q1;Q3 | P | After 12 weeks [median] | Q1;Q3 | P (6 vs. 12 weeks) | Morning administration [median] | Q1;Q3 | Evening administration [median] | Q1;Q3 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC [mg/dL] | 179.50 | 156.50; 200.70 | 137.70 | 125.4; 159.5 | <0.00001 | 134.3 | 117.4; 150.4 | 0.14 | 138.0 | 122.80; 160.20 | 134.3 | 121.0; 150.0 | 0.22 |

| HDL [mg/dL] | 42.60 | 8.48–41.00 | 47.91 | 13.52–45.2 | 0.00002 | 45.35 | 9.25–42.8 | 0.114 | 47.44 | 13.5–45.3 | 45.82 | 9.37–43.9 | 0.819 |

| TG [mg/dL] | 153.90 | 117.90;214.00 | 121.65 | 94.60;164.00 | < 0.00001 | 130.30 | 92.10;167.00 | 0.310 | 121.9 | 93.5;170.0 | 131.2 | 90.4;164.0 | 0.62 |

| AST [U/L] | 22.60 | 18.80;27.50 | 23.30 | 19.40;29.70 | 0.1279 | 23.50 | 19.50;29.70 | 0.494 | 23.5 | 19.8;29.8 | 23.0 | 19.2;29.3 | 0.87 |

| ALT [U/L] | 14.90 | 11.10;21.10 | 16.10 | 12.00;28.00 | 0.0045 | 17.70 | 12.00;26.50 | 0.426 | 18.0 | 12.0;27.2 | 15.8 | 12.1;27.3 | 0.467 |

| CK [U/L] | 73.00 | 55.00;108.00 | 80.00 | 58.0;115.0 | 0.011 | 84.0 | 60.0;125.0 | 0.782 | 86.0 | 56.0;116.0 | 80.0 | 63.0;128.0 | 0.984 |

| hs-CRP [mg/L] | 1.82 | 0.86;2.87 | 1.21 | 0.64;2.39 | 0.01 | 1.22 | 0.64;1.995 | 0.44 | 1.26 | 0.76;2.13 | 0.93 | 0.58;2.035 | 0.461 |

| apo B [mg/dL] | 93.00 | 77.00–104.00 | 68.00 | 57.00–83.00 | < 0.00001 | 67.00 | 58.00–78.00 | 0.171 | 69.00 | 60.00–78.00 | 66.00 | 58.00–81.00 | 0.14 |

| Lp(a) [mg/dL] | 14.05 | 5.10–25.55 | 10.50 | 4.60–23.00 | 0.051 | 11.0 | 4.80–24.15 | 0.512 | 10.35 | 4.30–20.90 | 10.50 | 4.45–23.50 | 0.59 |

| apoAI [mg/dL] | 147.0 | 131.00–164.00 | 150.00 | 135.00–172.00 | 0.007 | 154.00 | 141.00–172.00 | 0.5 | 156.00 | 135.00–175.00 | 151.00 | 137.00–171.00 | 0.108 |

Data are shown as median (interquartile distribution (Q1;Q3). TC — total cholesterol; HDL — high density lipoprotein; TG — triglycerides; AST — aspartate aminotransferase; ALT — alanine aminotrans-ferase; CK — creatine kinase; hsCRP — high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; apoB — apolipoprotein B; Lp(a) — lipoprotein(a); apoAI — apolipoprotein AI

With regard to apoB, a significant reduction was found in its concentration after 6 weeks of treatment with the study drug (93.00 [77.00; 104.00] vs. 68.00 [57.00;83.00]; p < 0.00001). The reduction was persistent throughout the observational period, and was independent of the timing of the study drug administration (Table 2).

Lipoprotein(a) decreased after the study drug administration, however without statistical significance (Table 2).

There was no alteration in AST activity. An increase in ALT activity compared with baseline values was recorded, regardless of the timing of the study drug administration. Nevertheless, the morning and evening measurements showed no significant difference (Table 2). There were no cases of ALT activity increase ≥ 3 × URL.

There was a statistically significant, transient increase in CK activity after initiation of the treatment (Table 2), always < 5 × URL. After 12 weeks of therapy CK activity showed no significant differences compared with baseline levels (73.0 [55.0;108.0] vs. 84.0 [60.0;125.0]; p = 0.245). Similar CK activity was noted regardless of the timing of the study drug administration (morning: 86.0 [56.0;116.0] vs. evening: 80.0 [63.0;128.0]; p = 0.984).

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration was significantly reduced after 6 weeks of treatment (Table 2). The effect was stable throughout the observational period (Table 2).

Discussion

The main finding of the ROSEZE study is confirmation of the effectiveness and safety of combined therapy for hypercholesterolemia using an FDC of low dose rosuvastatin (10 mg) and ezetimibe, regardless of the timing of drug administration, in patients unsuccessfully treated with statin monotherapy. According to available research, the current study is the first trial assessing the effectiveness of an FDC of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe in relation to the daily timing of drug administration.

As demonstrated in a meta-analysis of trials assessing statin therapy, each 40 mg/dL drop in LDL-C translates into a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (by 10%) [11] and major cardiovascular events (by 23%) [12]. More powerful statins compared with weaker ones, produce a highly significant 15% (95% confidence interval [CI] 11–18; p < 0.0001) further reduction in major vascular events [11]. More intensive LDL-C lowering therapies including potent statins alone or combinations of statins with ezetimibe or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK-9) inhibitors are associated with a great reduction in risk of total and cardiovascular mortality, especially when the baseline LDL-C level exceeds 100 mg/dL [13].

Surveys and national databases of patients with hypercholesterolemia and CAD demonstrated that the LDL-C target levels recommended by 2016 ESC guidelines were achieved only in a small percentage of patients: 19.3% according to EUROE-SPIRE IV [5], 19–25% according to a large real-life German registry from the years 2011–2016 [8] and were only 5.8% according to a large Italian database published in 2019 [9]. Other lessons coming from available registries include (i) too low usage of high intensity statins and (ii) frequently premature discontinuation of lipid lowering therapy (LLT).

Several trials demonstrated the superiority of combined treatment of hypercholesterolemia with statins and ezetimibe compared with statin monotherapy, revealing that addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy provides more extensive reduction of LDL-C than doubling the statin dose, and thus allows more patients to achieve the LDL-C goal [14–16]. The IMPROVE-IT trial, demonstrated that adding ezetimibe to low intensity statin (simvastatin 40 mg) carries benefit (24% of additional reduction in LDL-C compared with statin monotherapy and lowering the risk of cardiovascular events compared with statin monotherapy with a 2.0-percentage-point lower rate of primary end point defined as a composite of death from cardiovascular disease, a major coronary event or nonfatal stroke [17]) independent of age [18] and sex [19] with a good safety profile, supporting the use of intensive, combined LLT to optimize cardiovascular outcomes [17–19].

In studies evaluating the effectiveness of more potent regimens, rosuvastatin enabled LDL-C reduction by 44–47% [20–22]. The PULSAR trial revealed that in high-risk patients with hypercholesterolemia, rosuvastatin 10 mg is more efficient at reducing the LDL-C level than the commonly used 20 mg dose of atorvastatin, enabling LDL-C goal achievement and improving other lipid parameters [22]. In the MRS-ROZE study, Kim et al. [23] demonstrated that FDCs of ezetimibe and rosuvastatin provided superior efficacy to rosuvastatin alone in lowering LDL-C, TC and TG levels (reduction by 56–63%, 37–43%, and 19–24%, respectively).

Similarly, the I-ROSETTE trial reported the LDL-C lowering efficacy of each ezetimibe/rosuvastatin combination to be superior to each of the respective doses of rosuvastatin [24]. The mean percent change in LDL-C in all ezetimibe/rosuvastatin combination groups exceeded 50% [24]. Moreover, the number of patients who achieved target LDL-C levels after 8 weeks of an observational period was significantly higher in the combined therapy group than in the rosuvastatin monotherapy group (92.3% vs. 79.9%, p < 0.001) [24]. Rosuvastatin alone or in combination with ezetimibe is very effective even in patients with familiar hypercholesterolemia. Mickiewicz et al. [25] demonstrated a reduction in LDL-C concentration by 45.9% and 55.4% depending whether it concerned monogenic or polygenic subjects with familiar hypercholesterolemia [25].

As expected, the present study also demonstrated that an FDC of rosuvastatin 10 mg/ezetimibe 10 mg significantly reduces LDL-C and other lipid fractions including TC and TG. The median percentage change in LDL-C after FDC drug in the current study was −35–40%. It allowed achievement of the target LDL-C level < 70 mg/dL in 66.27% and 69.88% in patients receiving the FDC drug in the morning and in the evening, respectively. Nevertheless, this result cannot be regarded as fully satisfactory, considering that according to the newly published 2019 European Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemias, the therapeutic goal for LDL-C in very high-risk patients was further lowered to the level of < 55 mg/dL (< 1.4 mmol/L) [4], thus the combination with 10 mg of rosuvastatin might not be sufficient for every single patient.

Apolipoprotein B, which is known to be a more informative marker of adequacy of statin treatment than LDL-C [26], similar to other studies [27–30] it was reduced in the present study by 26.9%, achieving median values close to those recommended in the recent 2019 guidelines [4].

Nozue et al. [31] showed a potential role of ezetimibe as an Lp(a) lowering drug. The reduction in Lp(a) concentration in the current study did not reach statistical significance. In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Sahebkar et al. [32] demonstrated that ezetimibe in monotherapy or in combination with statin did not affect plasma Lp(a) levels.

As indicated by the present results, the daily timing of administration of the study drug did not affect its efficacy. So far, statins were commonly administered in the evening due to the peak of hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductive activity and cholesterol synthesis which occurs at night [33, 34]. Meanwhile, the majority of medications are taken in the morning, thus avoidance of the last pill during the day, which is statin in most cases, is a huge problem. For this reason, we investigated whether the daily timing of intake is relevant for lipid lowering drugs. Although, in our study there was no significant difference between obtained LDL-C levels according to the timing of study drug intake (morning vs. evening), the discrepancies found in LDL-C reduction depending on the time of test performance: 12 or 24 hours after the last dose of the drug studied, are not completely clear and need further exploration. According to a research by Nishida et al. [35], rosuvastatin exposure decreases under the fed condition compared with strict fasting. However, it was only a pharmacokinetics study assessing potential food effect and the bioequivalence between co-administered ezetimibe and rosuvastatin and FDC tablets containing ezetimibe and rosuvastatin in healthy Japanese subjects under fasted and fed conditions [35].

According to available research, the present study is the first one to reveal the influence of the timing of an FDC of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe on the effectiveness of LLT. Observations herein, indicate similar potency of tested therapy, regardless of whether the drug was administered in the evening or in the morning. As a consequence of this, we encourage administration of the FDC of rosuvastatin with ezetimibe in the morning with the majority of other drugs. This timing modification may translate into better adherence to recommended LLT, compared with traditional statin dosing in the evening, which leads to its frequent omission. Simplifying the treatment strategies and reducing the number of tablets by using polypills are one of key factors for better cooperation between health care providers and patients, and better drug adherence [3].

Similar to previous studies in patients with CAD [36, 37], in the present study, the tested therapy provoked a further reduction in hs-CRP concentration, compared with baseline values. Considering the fact that our population of patients had been already treated with statins for secondary prevention prior to the study, it was the addition of ezetimibe that led to a further reduction of the inflammatory process. This finding supports the existence of a pleotropic anti-inflammatory, in addition to hypolipemic, effect of ezetimibe, both of which are responsible for residual atherosclerotic risk [38].

The safety and tolerability of the tested therapy were similar in both arms of the current study. There were no cases of rosuvastatin/ezetimiberelated adverse events including muscular, hepatic and gastrointestinal events.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. The first one is a relatively small sample size. Due to the preliminary nature of the study, the number of patients included in the current analysis is lower than calculated earlier for the sample size. Second, the study was designed to assess changes in LDL-C concentration without addressing the relationship between LDL-C reduction and clinical outcomes. Third, the divergences between LDL-C levels assessed 12 and 24 hours after the last dose of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe may have had a multifactorial origin which is difficult to explain at this point and would likely require an adequate sample size for clarification.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that a combination of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe as a polypill is effective and well tolerated, showing similar efficacy whether administered in the morning or in the evening.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend N, Nichols M, Scarborough P, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe–epidemiological update 2015. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(40):2696–2705. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catapano A, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Assocciation for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(39):2999–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiner Ž, De Backer G, Fras Z, et al. Lipid lowering drug therapy in patients with coronary heart disease from 24 European countries — Findings from the EUROASPIRE IV survey. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dykun I, Wiefhoff D, Totzeck M, et al. Disconcordance between ESC prevention guidelines and observed lipid profiles in patients with known coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;22:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Presta V, Figliuzzi I, Miceli F, et al. Achievement of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol targets in primary and secondary prevention: Analysis of a large real practice database in Italy. Atherosclerosis. 2019;285:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obońska K, Kasprzak M, Sikora J, et al. The impact of the time of drug administration on the effectiveness of combined treatment of hypercholesterolemia with Rosuvastatin and Ezetimibe (RosEze): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):316. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753)(10):1670–1681. 61350–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navarese EP, Robinson JG, Kowalewski M, et al. Association between baseline LDL-C level and total and cardiovascular mortality after LDL-C lowering: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1566–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikhailidis DP, Lawson RW, McCormick AL, et al. Comparative efficacy of the addition of ezetimibe to statin vs statin titration in patients with hypercholesterolaemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(6):1191–1210. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.571239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambegaonkar BM, Tipping D, Polis AB, et al. Achieving goal lipid levels with ezetimibe plus statin add-on or switch therapy compared with doubling the statin dose. A pooled analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237(2):829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzi M, Ambegaonkar B, Baxter CA, et al. Ezetimibe in high-risk, previously treated statin patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of lipid efficacy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108(5):487–509. doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1379-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach RG, Cannon CP, Giugliano RP, et al. Effect of simvastatin-ezetimibe compared with simvastatin monotherapy after acute coronary syndrome among patients 75 years or older: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(9):846–854. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato ET, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of adding ezetimibe to statin therapy among women and men: insight from IMPROVE-IT (improved reduction of outcomes: vytorin efficacy international trial) J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR* Trial) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(2)(03):152–160. 00530–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster H, Barter PJ, Stender S, et al. Effects of switching statins on achievement of lipid goals: measuring effective reductions in cholesterol using rosuvastatin therapy (MERCURY I) study. Am Heart J. 2004;147(4):705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clearfield MB, Amerena J, Bassand JP, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin 10 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg in high-risk patients with hypercholesterolemia — Prospective study to evaluate the Use of Low doses of the Statins Atorvastatin and Rosuvastatin (PULSAR) Trials. 2006;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KJ, Kim SH, Yoon YW, et al. Effect of fixed-dose combinations of ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia: MRS-ROZE (Multicenter Randomized Study of ROsuvastatin and eZEtimibe) Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;34(5):371–382. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong SJ, Jeong HS, Ahn JC, et al. A Phase III Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Active Comparator Clinical Trial to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Combination Therapy With Ezetimibe and Rosuvastatin Versus Rosuvastatin Monotherapy in Patients With Hypercholesterolemia: I-ROSETTE (Ildong Rosuvastatin & Ezetimibe for Hypercholesterolemia) Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Ther. 2018;40(2):226–241.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mickiewicz A, Futema M, Ćwiklinska A, et al. Higher responsiveness to rosuvastatin in polygenic versus monogenic hypercholesterolaemia: a propensity score analysis. Life (Basel) 2020;10(5):73. doi: 10.3390/life10050073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thanassoulis G, Williams K, Ye K, et al. Relations of change in plasma levels of LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apoB with risk reduction from statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000759. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen T, Olsson A, Færgeman O, et al. Lipoprotein changes and reduction in the incidence of major coronary heart disease events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Circulation. 1998;97(15):1453–1460. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1453.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones PH, Hunninghake DB, Ferdinand KC, et al. Effects of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin on nonhigh-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoproteins, and lipid ratios in patients with hypercholesterolemia: additional results from the STELLAR trial. Clin Ther. 2004;26(9):1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed O, Littmann K, Gustafsson U, et al. Ezetimibe in combination with simvastatin reduces remnant cholesterol without affecting biliary lipid concentrations in gallstone patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e009876. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simes RJ, Marschner IC, Hunt D, et al. Relationship between lipid levels and clinical outcomes in the long-term intervention with pravastatin in the ischemic disease (LIPID) trial. To what extent is the reduction in coronary events with pravastatin explained by onstudy lipid levels? Circulation. 2002;105:1162–1169. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nozue T, Michishita I, Mizuguchi I. Effects of ezetimibe on remnant-like particle cholesterol, lipoprotein (a), and oxidized low-density lipoprotein in patients with dyslipidemia. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(1):37–44. doi: 10.5551/jat.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahebkar A, Simental-Mendía L, Pirro M, et al. Impact of ezetimibe on plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations as monotherapy or in combination with statins: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials [published correction appears in Sci Rep 2020, 10(1): 2999] Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):17887. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36204-7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones PJ, Schoeller DA. Evidence for diurnal periodicity in human cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(4):667–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker TS, McNamara DJ, Brown C, et al. Mevalonic acid in human plasma: relationship of concentration and circadian rhythm to cholesterol synthesis rates in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(9):3037–3041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishida C, Matsumoto Y, Fujimoto K, et al. The bioequivalence and effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of a fixed-dose combination tablet containing rosuvastatin and ezetimibe in healthy Japanese subjects. Clin Transl Sci. 2019;12(6):704–712. doi: 10.1111/cts.12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren Y, Zhu H, Fan Z, et al. Comparison of the effect of rosuvastatin versus rosuvastatin/ezetimibe on markers of inflammation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(5):4942–4950. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, et al. Achievement of dual low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein targets more frequent with the addition of ezetimibe to simvastatin and associated with better outcomes in IMPROVE-IT. Circulation. 2015;132(13):1224–1233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vavlukis M, Vavlukis A. Adding ezetimibe to statin therapy: latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212534. doi: 10.7573/dic.212534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]