Abstract

Brain morphometry plays a fundamental role in neuroimaging research. In this work, we propose a novel method for brain surface morphometry analysis based on surface foliation theory. Given brain cortical surfaces with automatically extracted landmark curves, we first construct finite foliations on surfaces. A set of admissible curves and a height parameter for each loop are provided by users. The admissible curves cut the surface into a set of pairs of pants. A pants decomposition graph is then constructed. Strebel differential is obtained by computing a unique harmonic map from surface to pants decomposition graph. The critical trajectories of Strebel differential decompose the surface into topological cylinders. After conformally mapping those topological cylinders to standard cylinders, parameters of standard cylinders (height, circumference) are intrinsic geometric features of the original cortical surfaces and thus can be used for morphometry analysis purpose. In this work, we propose a set of novel surface features. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to make use of surface foliation theory for brain morphometry analysis. The features we computed are intrinsic and informative. The proposed method is rigorous, geometric, and automatic. Experimental results on classifying brain cortical surfaces between patients with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy control subjects demonstrate the efficiency and efficacy of our method.

Keywords: Brain morphometry, shape classification, surface foliation, Alzheimer disease

1. Introduction

MRI based brain morphometry analysis has gained extensive interest in the past decades [17,20]. A lot of research works are focused on identifying very early signs of brain functional and structural changes for early identification and prevention of neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States, and the fifth-leading cause of death among those age 65 and older as reported by Alzheimers Association in 2018 [1], has obtained much interest from researchers around the world. Early detection and prevention of AD can significantly impact treatment options, improve quality of life, and save considerable health care costs. As a non-invasive method, brain imaging study has great potentials that will powerfully track disease progression and therapeutic efficacy in AD. For example, whole brain morphometry, hippocampal and entorhinal cortex volumes are among most promising candidate biomarkers in structural MRI analysis. However, missing at this time is a widely available, highly objective brain imaging biomarker capable of identifying abnormal degrees of cerebral atrophy and accelerated rate of atrophy progression in preclinical individuals at high risk for AD in who early intervention is most needed.

Computational geometric methods are widely used in medical imaging fields including virtual colonoscopy and brain morphometry analysis. Rooted in deep geometry analysis research, computational geometric methods may provide rigorous and accurate quantification of abnormal brain development and thus hold a potential to detect preclinical AD in presymptomatic subjects. Specifically, surface morphometry techniques, such as conformal mapping and area preserving mapping, have shown to be feasible and powerful tools in brain morphometry research.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to propose the use of the surface foliation theory for brain morphometry analysis. We validate our method by classifying brain surfaces of patients with Alzheimer disease and healthy control subjects. Experimental results indicate the efficiency and efficacy of our proposed method. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

A novel brain surface morphometry analysis method is proposed based on surface foliation theory.

A set of new geometric features computed by pants decomposition and conformal mapping of topological cylinders are also proposed for surface indexing and classification.

The proposed method is rigorous, geometric and automatic.

2. Previous Works

Brain morphometry analysis plays a fundamental role in medical imaging [11, 22, 24]. Many research works have investigated the brain morphometry analysis and shape classification. Thompson et al. [17] analyzed brain morphometry using thickness features. Winkler et al. [20] proposed that the surface area could serve as an important morphometry feature to study brain structural MRI images. Besides, numerous methods have been presented in order to describe shapes, including statistical methods [14], topology based methods [6], and geometry based methods [12]. To solve real 3D shape problems, researchers have also proposed many shape analysis and classification methods. Chaplot et al. [3] employed wavelets and neural network for classification of brain MR images. Zacharaki et al. [23] proposed the use of pattern classification methods for classifying different types of brain tumors. Recently, Su et al. [16] presented a shape classification method busing Wasserstein distance. The method computed a unique optimal mass transport map between two measures, and used Wasserstein distance to intrinsically measure the dissimilarities between shapes.

Foliation [15] is a generalization of vector field. In computer graphics field, Zhang et al. [25] invented a vector field design system which could help users create various vector fields with control over vector field topology. The technique can be used in some applications such as example-based texture synthesis, painterly rendering of images, and pencil sketch illustrations of smooth surfaces. Recently, Campen et al. [2] proposed a method for bijective parametrization of 2D and 3D objects based on simplicial foliations. The method decomposed a mesh into one-dimensional submanifolds, reducing the mapping problem to parametrization of a lower-dimensional manifold. It was proved that the resulting maps are bijective and continuous. In isogeometric analysis field, Lei et al. [9] presented a novel quadrilateral and hexahedral mesh generation method using foliation theory. A colorable quad-mesh method was employed to generate the quadrilateral mesh based on Strebel differentials, which then leads to the structured hexahedral mesh of the enclosed volume for high genus surfaces. Hsieh et al. [7] studied an elasticity model for shape evolution where the control is interpreted as the derivative of a body force density in the deforming volume, and a special case of the model decomposes the shapes into a family of layers called foliation.

3. Theoretic Foundation

We briefly review the basic concepts and theorems in conformal geometry. Detailed treatments can be found in [5,4,15].

A complex function , (x, y) → (u, v), satisfying the Cauchy-Riemann equation

is called a holomorphic function. If f is invertible, and f−1 is also holomorphic, then f is called a bi-holomorphic function. For a surface with a complex atlas , if all chart transition functions are bi-holomorphic, it is called a Riemann surface, the atlas is called a complex structure. All oriented metric surfaces are Riemann surfaces.

Definition 1 (Holomorphic Quadratic Differentials). Assume S is a Riemann surface. Let Φ be a complex differential form, such that on each local chart with the local complex parameter , in which φα(zα) is a holomorphic function. Then Φ is called a holomorphic quadratic differential.

Based on the Riemann-Roch Theorem, the linear space of all holomorphic quadratic differentials is 3g − 3 complex dimensional with the genus g > 1. A point zi ∈ S is called a zero of Φ, if φ(zi) vanishes. A holomorphic quadratic differential has 4g − 4 zeros. For any point away from zero, a local coordinates can be defined as follows:

| (1) |

which are so-called natural coordinates induced by Φ. The curves with constant real (imaginary) natural coordinates are called the vertical (horizontal) trajectories, and the trajectories through the zeros are called the critical trajectories.

Definition 2 (Strebel [15]). If all of the horizontal trajectories of a holomorphic quadratic differential Φ on a Riemann surface S are finite, then Φ is called a Strebel differential.

We say a holomorphic quadratic differential Φ is Strebel, if and only if its critical horizontal trajectories form a finite graph [15]. In the space of all holomorphic quadratic differentials, the Strebel differentials are dense. Given a holomorphic quadratic differential Φ, a flat metric with cone singularities (cone angles equal to −π), denoted as |Φ|, is induced by the natural coordinates in Eqn. 1. The following existence of a Strebel differential with prescribed type and heights was proved by Hubbard and Masur.

Theorem 1 (Hubbard and Masur [8]). For non-intersecting simple loops Γ = {γ1, γ2, ⋯ ,γn}, and positive numbers {h1, h2, ⋯ , hn}, n ≤ 3g − 3, there exists a unique holomorphic quadratic differential Φ, which satisfies the following:

A surface is partitioned by the critical graph of Φ into n cylinders, {C1,C2, ⋯ ,Cn}, such that γk is the generator of Ck,

The height of each cylinder (Ck,|Φ|) is equal to hk, k = 1,2, ⋯ ,n.

We give the geometric interpretation of above theorem as follows: under the flat metric |Φ|, each cylinder Ck becomes a canonical flat cylinder with height hk. Strebel’s theorem allows for specifying the type of Φ and the height of each cylinder Ck.

Harmonic Map

Assume G = 〈E,N〉 is a graph, and is an edge weight function. p and q denote two points on the graph, and dh(p, q) represents the shortest distance between them. Suppose (S, g) is a surface with a Riemannian metric g. Given a map f : (S, g) → (G, h), we say a point p ∈ S is a regular point, if its image is not any node of G, otherwise it is a critical point. We denote the set of all critical points as Γ. For each regular point p ∈ S, a neighborhood Up can be found and the restriction of the map on Up can be treated as a normal function . An isothermal coordinates (x, y) are selected on Up, such that the metric has a special form g = e2λ(x,y)(dx2 + dy2). Then the harmonic energy is represented by , where , and the area element is dAg = e2λdxdy. The harmonic energy of the whole map is given as

The critical point of the harmonic energy is called a harmonic map. Wolf [21] proved the existence and the uniqueness of the harmonic map.

Theorem 2 (Wolf [21]). The harmonic map f : (S, g) → (G, h) exists and is unique in each homotopy class. Moreover, as induced by the harmonic map, the Hopf differen6tial Φ = 〈fz, fz〉dz2 is a holomorphic quadratic differential, where z = x + iy denotes the complex isothermal coordinates of (S, g).

Conformal Module

Let (S, g) be a surface of genus g > 1. Given 3g − 3 non-intersecting simple loops Γ = {γi} and positive numbers {hi}, the unique Strebel differential Φ based on Hubbard and Masur’s theorem induces a flat metric |Φ| with cone singularities, and cylinders . The height and circumference for each cylinder (Ck, |Φ|) is denoted by (hk, lk). The set of all (hk, lk) are the conformal modules.

4. Algorithm

Pants Decomposition

Let S be a closed surface of genus g, represented by triangular mesh. Let Γ = {γi, i = 1,2, …,3g − 3} be a set of admissible curves, which can be generated automatically or manually specified. User also specifies a height parameter hi for each admissible curve γi. These admissible curves decompose surface S to a set of pants . The pants decomposition graph G is then constructed in the following way:

each pants Pi corresponds to a node in G;

each admissible curve connecting two pants corresponds to an edge in G; two pants may be the same, in that case, the edge becomes a loop.

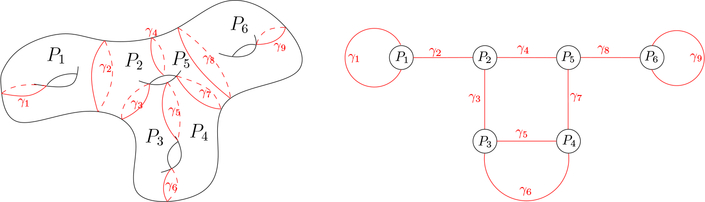

Fig. 1 illustrates pants decomposition and pants decomposition graph.

Fig. 1.

Pants decomposition of surface (left) and pants decomposition graph (right)

Discrete Harmonic Map to Graph

We compute a unique harmonic map f from surface S to G. The harmonic energy is defined as

where vi are vertex on S, f(vi) on G, eij are edges, wij cotangent weight.

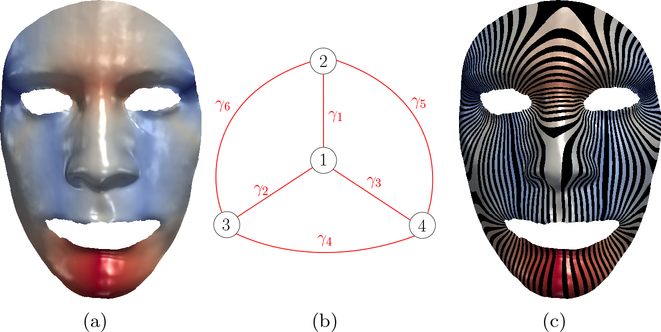

For each vi, by moving f(vi) to the barycenter of its neighbors on graph G, the energy E will decrease monotonically, which is due to the following definition of barycenter. By iteratively doing so, energy E will attain its minimum value, at which point we obtain a harmonic map f : S → G. Thm. 2 guarantees this harmonic map we obtained is the unique one. Fig. 2 (a) illustrates harmonic map from a human face surface to its pants decomposition graph (b), (c) shows surface foliation, where color indicates vertices’ target position on graph G.

Fig. 2.

Harmonic map from human face to pants decomposition graph and induced surface foliation

The initial map f0 should be specified in the same homotopy class as the final harmonic map f. Subgraph at a node consists of the node and all edges connecting to it. Then initial map can be obtained automatically in the following way: each pants Pi be mapped to the subgraph Gi at node i of G, then all pants maps are glued together to obtain f0.

Calculate Barycenter

For each f(vi), we move f(vi) to the barycenter of its neighbors. Calculating barycenter is done by minimizing energy

where the right are exactly the terms in E that involve f(vi). d(f(vi), f(vj)) can be calculated piecewisely. Then minimization of above energy boils down to minimum calculation of a set of quadratic functions.

Surface with Boundaries

For surfaces with boundaries, we can either double cover those surfaces to obtain a closed surface, or we can add boundaries to the set of admissible curves, such curves correspond to open edges on G. Computation of harmonic map remains same.

Extract Geometric Features

A holomorphic quadratic differential Φ can be induced from the harmonic map we obtained. Tracing the critical trajectories of Φ and slicing surface along them, we obtain a set of 3g−3 topological cylinders, each corresponds to an input admissible curve. The set of heights and circumferences of those cylinders are topological invariants, which we propsose to use as geometric features for classification problems in next section.

5. Experiment

To evaluate the proposed method for brain morphometry study, we conducted experiments on a dataset of 60 brain cortical surfaces. Triangle mesh of each brain surface has around 100K triangles.

Data Preparation

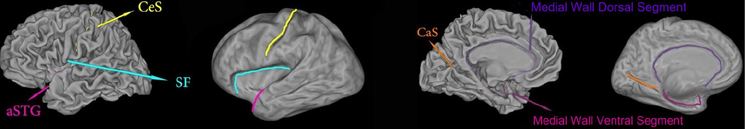

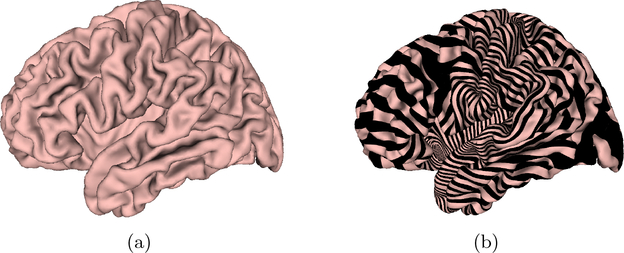

The dataset used in our experiments includes images from 30 patients with Alzheimer disease and 30 healthy control subjects. The structural MRI images were from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [13]. The brain cortical surfaces were reconstructed from the MRI images by FreeSurfer. Then, a set of ‘Core 6’ landmark curves, including the Central Sulcus (CeS), Anterior Half of the Superior Temporal Gyrus (aSTG), Sylvian Fissure (SF), Calcarine Sulcus (CaS), Medial Wall Ventral Segment, and Medial Wall Dorsal Segment, are automatically traced on each cortical surface using the Caret package [19]. In Caret software, the PALS-B12 atlas is used to delineate the “core 6” landmarks, which are well-defined and geographically consistent, when compared with other gyral and sulcal features on human cortex. The stability and consistency of the six landmarks was validated in [18]. An illustration of the landmark curves on a left cortical surface is shown in Fig. 3 with two views. We show the landmarks with both the original and inflated cortical surfaces for clarity. A brain surface and its foliation are shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b), respectively.

Fig. 3.

A left cortical surface with six landmark curves, which are automatically labeled with Caret, showing in two different views on both the original and inflated surfaces.

Fig. 4.

A brain surface and its foliation.

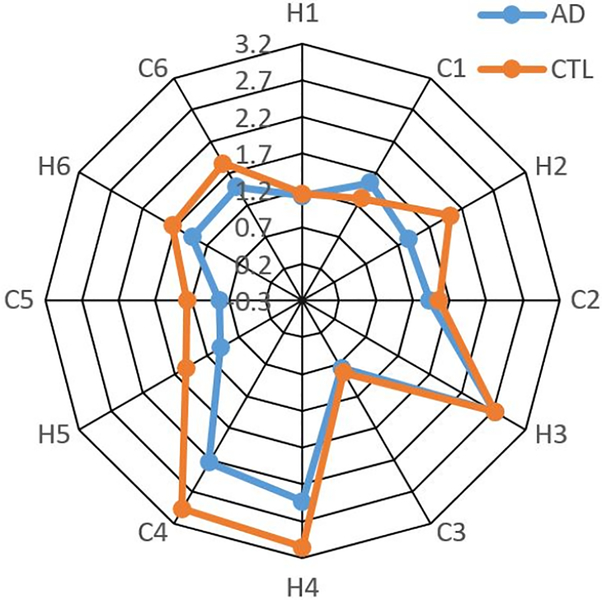

Foliation Feature Visualization

We illustrate the difference of feature values between a pair of subjects with AD and healthy control subject (CTL) using radar chart. Radar chart displays multi-variate data in a two-dimensional chart where multiple variables are represented on axes starting from the same point. As shown in Fig. 5, six pairs of heights(H) and circumferences(C) corresponding to core 6 landmarks, i.e., twelve features (labeled by ‘H1’, ‘C1’,…,’H6’, ‘C6’) are associated with twelve corners on the radar chart. We find that the pair of the H4 height and C4 circumference features associated to landmark curve of medial wall dorsal segment have the largest difference between these two subjects radar charts represented by a blue color line and an orange color line respectively. Although more validations are warranted, our research results may help discover AD related brain atrophy patterns.

Fig. 5.

Radar chart.

Classification

We validated our method with brain surface classification on a dataset of brain cortical surfaces from 30 patients with Alzheimer disease and 30 healthy control subjects. The SVM method was employed as the classifier with 10-fold cross validation in our experiments. For each image, the input feature vector of the classifier includes 12 features. For comparison purpose, we also compute cortical surface area and cortical surface mean curvatures, two cortical surface features frequently adopted in prior structural MRI analyses [10]. We also applied SVM as the classifiers for these two features. Experimental results are shown in Table 1. Our proposed method achieved 78.33% correctness rate, which is better than the correctness rate 56.67% in the brain surface area based method and 55.00% in the brain surface mean curvature based method. Although multi-subject studies are clearly necessary, this experiment demonstrates that the foliation theory based geometric features may have the potential to quantify and measure AD related cortical surface changes.

Table 1.

Classification accuracy comparision between our method and other methods.

| Classification method | Correctness rate |

|---|---|

| Our Method | 78.33% |

| Brain Surface Area | 56.67% |

| Brain Mean Curvature | 55.00% |

6. Conclusion

In this paper, a novel brain surface classification method is proposed based on surface foliation theory. The method is rigorous, geometric, and automatic. In order to validate our proposed method, we applied our method on classifying brain cortical surfaces between patients with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy control subjects, and the preliminary experimental results demonstrated the efficiency and efficacy of our method. In the future, we will employ our method to explore brain morphometry related to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and other applications in the medical imaging field.

References

- 1.Association A et al. 2018 alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(3):367–429, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campen M, Silva C, and Zorin D. Bijective maps from simplicial foliations. ACM Transactions on Graphics, to appear, 35(4):7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaplot S, Patnaik L, and Jagannathan N. Classification of magnetic resonance brain images using wavelets as input to support vector machine and neural network. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 1(1):86–92, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farkas H and Kra I. Riemann surfaces. Springer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu X and Yau S-T. Computational conformal geometry. International Press Somerville, Mass, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilaga M et al. Topology matching for fully automatic similarity estimation of 3d shapes. In Proceedings of the 28th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, pages 203–212. ACM, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh D-N, Arguillère S, Charon N, Miller MI, and Younes L. A model forelastic evolution on foliated shapes. In International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging, pages 644–655. Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard J and Masur H. Quadratic differentials and foliations. Acta Mathematica, 142(1):221–274, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei N, Zheng X, Jiang J, Lin Y, and Gu X. Quadrilateral and hexahedral mesh generation based on surface foliation theory. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li S, Yuan X, Pu F, Li D, Fan Y, Wu L, Chao W, Chen N, He Y, and Han Y. Abnormal changes of multidimensional surface features using multivariate pattern classification in amnestic mild cognitive impairment patients. J. Neurosci, 34(32):10541–10553, August 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luders E, Narr K, Bilder R, Thompson P, Szeszko P, Hamilton L, and Toga A. Positive correlations between corpus callosum thickness and intelligence. Neuroimage, 37(4):1457–1464, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoudi M and Sapiro G. Three-dimensional point cloud recognition via distributions of geometric distances. Graphical Models, 71(1):22–31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller S, Weiner M, Thal L, Petersen R, Jack C, Jagust W, Trojanowski J, Toga A, and Beckett L. The alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America, 15(4):869–877, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osada R, Funkhouser T, Chazelle B, and Dobkin D. Shape distributions. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), 21(4):807–832, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strebel K. Quadratic differentials. Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su Z, Zeng W, Wang Y, Lu Z-L, and Gu X. Shape classification using wasserstein distance for brain morphometry analysis. In International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging, pages 411–423. Springer, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson P et al. Dynamics of gray matter loss in alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23(3):994–1005, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Essen DC. A Population-Average, Landmark- and Surface-based (PALS) atlas of human cerebral cortex. Neuroimage, 28(3):635–662, November 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Essen D et al. An integrated software suite for surface-based analyses of cerebral cortex. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 8(5):443–459, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler A et al. Measuring and comparing brain cortical surface area and other areal quantities. Neuroimage, 61(4):1428–1443, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf M. On realizing measured foliations via quadratic differentials of harmonic maps tor-trees. Journal DAnalyse Mathematique, 68(1):107–120, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J-J, Yoon U, Yun H, Im K, Choi Y, Lee K, Park H, Hough M, and Lee J-M. Prediction for human intelligence using morphometric characteristics of cortical surface: partial least square analysis. Neuroscience, 246:351–361, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zacharaki E et al. Classification of brain tumor type and grade using mri texture and shape in a machine learning scheme. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 62(6):1609–1618, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng W, Shi R, Wang Y, Yau S-T, Gu X, Initiative ADN, et al. Teichmüller shape descriptor and its application to alzheimers disease study. International journal of computer vision, 105(2):155–170, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang E, Mischaikow K, and Turk G. Vector field design on surfaces. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG), 25(4):1294–1326, 2006. [Google Scholar]