Abstract

While family planning care (FPC) visits may serve as opportunities to address gaps in knowledge and access to limited resources, young Black women may also face structural barriers (i.e., racism, discrimination, bias) to engaging in care due to the intersections of racial identity, age, and socioeconomic status. Findings from interviews with 22 Black women, ages 18 to 29 years, about the lived experience of FPC highlighted dynamic patient–provider encounters. Women’s narratives uncovered the following essences: silence around sex impedes engagement in care, patient–provider racial concordance as protection from harm, providers as a source of discouragement and misinformation, frustration as a normative experience, decision making excludes discussion and deliberation, medical mistrust is pervasive and a part of Black consciousness, and meaningful and empathic patient–provider encounters are elusive. Health systems should prioritize developing and enhancing young Black women’s relationship with FPC providers to help mitigate persistent inequities that perpetuate disadvantage among this population.

Keywords: African American, contraception, patient–provider interaction, health care inequities, phenomenology, cultural health capital, qualitative, methods, Southeastern U.S.

Introduction

In the United States, Black women disproportionately experience unintended pregnancy and are more than twice as likely as White women to report experiencing an unintended pregnancy (Finer & Zolna, 2016). Health disparities persist as young, and lower income women also disproportionately experience mistimed and unwanted pregnancies compared with older and more affluent counterparts (Finer & Zolna, 2016). To mitigate the occurrence of an untimely pregnancy, women seek health care throughout their reproductive life course. Although research suggests that women will spend the majority of their reproductive years engaging with the health care system (Kjerulff et al., 2007), about half of this population remains in need of family planning services (Guttmacher Institute, 2016a). Specifically, those interested in hormonal and long-term family planning methods must engage with the health care system to obtain family planning information and services (Frost et al., 2013; Guttmacher Institute, 2016b). While family planning care (FPC) visits provide opportunities for women to obtain information and services they cannot obtain elsewhere, the combination of multiple marginalized identities, such as Black racial identity, young age, and low socioeconomic status (SES), may exacerbate racial inequities in care.

The cumulative effects of negative general health and FPC experiences have not been well documented in the literature, but mistreatment by the health care system may further perpetuate health inequities. Research shows that Black women use family planning services (Hall et al., 2014) and receive family planning counseling (Borrero et al., 2009) more than other reproductive-age women, yet rate their FPC encounters more poorly than White women (Cipres et al., 2017; Thorburn & Bogart, 2005; Yee & Simon, 2011a). Although scholars have documented historical examples of reproductive injustices (e.g., contraceptive coercion, forced sterilization; Roberts, 2014; Ross, 1994), Black women continue to report mistreatment in contemporary encounters with the health care system (Gomez & Wapman, 2017; Manze et al., 2016; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020; Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010). Black, Indigenous, and Other women of color report interactions with providers where they felt pressure to use or continue a method of birth control (Amico et al., 2016; Gomez & Wapman, 2017), experienced or feared judgment for their reproductive decisions (Amico et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2016), had a lack of provider trust (Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020), did not want to share that they have or would like to discontinue family planning methods, or were reluctant to share information with providers that could inform family planning method choice (Amico et al., 2016; Gomez & Wapman, 2017; Higgins et al., 2016). Negative experiences are important to document and assess as changes to FPC delivery could mitigate persistent health care inequities.

Young Black women may be exceptionally vulnerable during health care encounters because of sociocultural barriers. Research has shown that Black women report limited communication about sex in their families and communities (Crooks et al., 2019; Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010). Interviews of daughters from an intergenerational dyad study revealed that mothers did not discuss reproductive health issues with them, which later posed communication challenges with providers (Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010). A more recent study of Black women’s sexual development described how this population of women received little to no information from parents about sexual and reproductive health while growing up—a trend some admitted continuing with their children (Crooks et al., 2019). Therefore, women appreciated opportunities to receive sexual and reproductive health education from providers. Despite the benefits of obtaining critical health information during care encounters, women also reported feeling humiliated and further diminished when they opened up to providers and their provider did not believe the information they shared or the provider made assumptions about them and their sexual behaviors (Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010). Due to a lack of support and information from parents and providers, young Black women may attend visits where they have limited knowledge, skills, and comfort to effectively engage in care.

Black women may be further marginalized if faced with structural barriers within the health care context (i.e., racism, discrimination based on the intersections of social identities, implicit bias). National priorities, such as Healthy People 2030 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services—Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020), focus on addressing limited access to family planning information and services but fail to include objectives that address structural barriers to FPC. In addition, the paucity of research examining the experiences and intersections of FPC among Black women (Becker et al., 2009; Downing et al., 2007; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020; Sacks, 2013; Yee & Simon, 2011a), particularly young, unmarried, and childless women, leaves gaps in policy and practice that could be levereaged to address structural barriers. Understanding young Black women’s FPC experiences is important for (a) enabling women to obtain health care needed to reduce their risk of unwanted sexual and reproductive health outcomes in the long term and (b) informing FPC delivery to improve overall and future care experiences. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to describe the lived experience of FPC and its impacts on young Black women.

Theoretical Framework

Intersectionality

The intersectionality framework acknowledges the intertwined nature of a person’s multiple marginalized identities (e.g., age, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and disability) and how those identities function in society (Crenshaw, 1991). Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) created and initially used “intersectionality” to describe how Black women were doubly disadvantaged by race- and gender-based discrimination. Crenshaw further articulated how socially marginalized identities also functioned within power structures (i.e., systems of oppression: age-ism, race-ism, and class-ism) that distributed mistreatment, discrimination, or disadvantage.

Intersectionality is a theoretical and methodological tool that researchers can use to identify how certain populations are disproportionately affected due to historical and ongoing forms of oppression. Scholars reiterate that intersectionality should be employed to interrogate events and contexts that subjugate individuals rather than interrogating characteristics of the individuals themselves (Cho et al., 2013). Although intersectionality was initially used to examine the dual marginalization of Black racial identity and woman gender, scholars advocate for its continued use in a diverse range of fields, populations, and social phenomena (Cho et al., 2013). Extant sexual and reproductive health literature have often used an intersectional lens to examine the health care and lived experience of health management among populations of color, particularly Black women (Crooks et al., 2019; Manze et al., 2016; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020; Sacks, 2018).

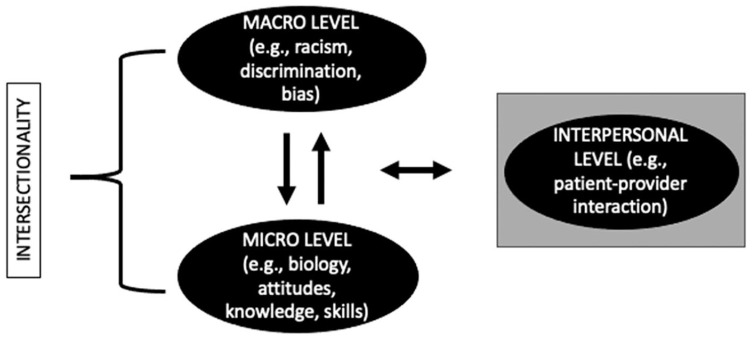

Guidelines for employing intersectionality in research vary. Scholars advocate for the early application of an intersectional lens to ensure study procedures adhere to the overarching goal of intersectionality, which is to address inequities in society (Abrams et al., 2020). In this study, intersectionality was a methodological approach and a guiding framework for the study conceptualization, design, analysis, and interpretation of the findings. The intersectionality perspective also helped link micro-level factors such as women’s biology, knowledge, attitudes, and the skills they brought with them to the visit with higher order factors and experiences, such as racism, discrimination, and bias (Figure 1). Furthermore, an intersectional perspective highlighted how interlocking oppressions function within the larger sociopolitical context and at the interpersonal level. This study was interested in understanding how multiple socially marginalized identities and their related systems of oppression function within the FPC encounter through the patient–provider interaction. Thus, intersectionality enabled an examination of multiple dimensions of an experience by examining one phenomenon—the lived experience of FPC.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the dimensions of the family planning care experience using an intersectional perspective.

Note. Definition of intersectionality: The ways in which multiple marginalized social identities, such as age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, function within power structures that create exponential disadvantage for select groups of people.

Methods

Study Design

These data are part of a mixed-methods study that included an online survey. Women were recruited through social media ads, email blasts to African American organizations in the region, word of mouth, and in-person recruitment at local events, including on-campus at the local university. Participants had to self-identify as a Black woman, U.S. resident, and have had an FPC visit in the past 12 months to talk about starting, stopping, or switching birth control. Women, ages 18 to 29 years, were selected because this age group experiences the highest rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States (Finer & Zolna, 2016). In addition, those who were married or had given birth before were excluded from participation, as the experience of FPC would likely be different for these groups. Consent and survey completion occurred online through Qualtrics. At the end of the survey, women indicated their willingness to complete two in-depth interviews by providing contact information. The researcher contacted women for interviews using purposive sampling based on a combination of responses to online survey questions about their FPC experience using a marker for how women may have experienced mistreatment—reactance (e.g., experience of anger, frustration, irritation, or annoyance while talking to the provider; Dillard & Shen, 2005) and a semantic differential scale (Rosenberg & Navarro, 2018) to capture any negative sentiments women may have recalled while talking to their provider about birth control. As the FPC space has served as a place of reproductive oppression for women, particularly those who identify as women of color, we wanted to include those with a range of impressions of the most recent FPC visit, including unfavorable impressions. In addition, we included a subjective measure for SES. Response options “don’t meet basic expenses” and “just meet basic expenses” represented low SES, and responses “meet needs with a little left” and “live comfortably” represented high SES (Williams et al., 2017). The University of South Florida Institutional Review Board approved this study prior to data collection.

Data Collection

After piloting the interview guides with three women from the community, interviews took place via in-person or videoconferencing (i.e., Zoom) between January and April 2019. Women were asked to complete both interviews (Seidman, 2013) within a 2-week time frame. At the start of each interview, the researcher gained verbal consent and told women that interviews were to be informal—the researcher would take a listening role and the participant a storyteller role to co-construct the lived experience of FPC. Women received a US$55 e-gift card for completing both interviews. Two women only completed Interview 1; they received a US$20 e-gift card and their data were excluded from the analysis.

Analysis

In this study, we used the modified van Kaam method of phenomenological analysis (Moustakas, 1994). The primary researcher engaged in an independent and iterative analysis, which included reflexive journaling, immersion in the data, coding, and memoing. Throughout the data collection and analysis processes, the researcher ensured the validity of the data through several key steps accustomed to qualitative research and phenomenology, including epoché or bracketing, openness, and reflexivity (Berger, 2015; Finlay, 2002; Morse & Mitcham, 2002; Moustakas, 1994; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). To increase the probability of collecting rich data, the researcher also used techniques such as iterative questioning, summarizing the participant’s responses for clarification, and frequent debriefing sessions with another researcher (peer debriefing; Shenton, 2004).

Results

Most women in this study had health insurance (91%), were from the Southern United States (77%), college educated (73%), and low SES (54%). The mean age was 24 years (SD = 3.0). Data from the online survey showed that, on average, women in this sample rated their most recent FPC visit 7/10 (range = 0–10). Despite this moderate rating, 12 of the 22 women experienced reactance during their FPC visit as categorized by perceiving a threat to their reproductive autonomy and experiencing anger and negative cognitions while talking to their provider (Table 1 Supplement).

Women’s narratives uncovered the following essences and experiences: (a) silence around sex impedes engagement in care, (b) patient–provider racial concordance as protection from harm, (c) providers as a source of discouragement and misinformation, (d) frustration as a normative experience during FPC visits, (e) decision making excludes discussion and deliberation, (f) medical mistrust is pervasive and part of Black consciousness, and (g) meaningful and empathic patient–provider encounters are elusive. We also present data regarding how women prepared for the visit and how their meaning-making influenced perceptions about future health care encounters to further contextualize their experiences.

Preparation to Improve Care Experiences

The most common reason women scheduled an FPC visit was to get a well-woman exam or to discuss family planning options. In preparation for their upcoming visit, women gathered information about their reproductive health issues and potential family planning choices from parents and friends. Women sought the counsel of family and friends yet were unsatisfied with the information these sources provided; few sources had adequate information or personal experiences with methods of interest.

Time spent preparing for an upcoming visit helped some women know what questions to ask their provider, or at least made them more informed of potential health issues. One woman scheduled her most recent well-woman exam because she was returning home from college and was experiencing discomfort and issues with her intrauterine device (IUD). As she stated, “my concern . . . because I do too many ‘Googles’ . . . was that it was dislodged, that it was lost in my vagina somewhere . . . all types of other crazy things” (25-year-old, high SES). She wanted to have a general understanding of her situation before seeing her provider. Women invested time in preparing for visits, which they expected would improve their experience.

Silence About Sex Impedes Engagement in Care

Women reflected on how their Black identity affected the ways in which they entered and engaged with the health care system. They also connected limitations in their knowledge and understanding about their bodies and sexual health to delays in care seeking and their comfort discussing these topics. While women lamented about the “silence around sex in the Black community,” they viewed having access to a health care professional as a resource to fill gaps in knowledge and to get help for managing health issues. Some described how providers helped them gain information not available in their communities about their bodies, which consequently helped them protect themselves.

Women described “the silence” as a cultural norm. A participant summed up this normative experience by stating,

Everybody knows Black parents don’t talk about sex. Everybody [thinks] that you just grow up knowing about sex . . . if I hadn’t gone, took the time to actually talk to my doctor, go to a doctor period . . . I would be just another statistic in terms of get pregnant early, in terms of having STDs. (20-year-old, low SES)

Other women faced health challenges, such as excessive menstrual bleeding, and when they tried to engage family members in conversation, they were dismissed or they perceived family were unwilling to talk with them about these topics. As another woman described,

Wearing super plus tampons in 9th and 10th grade is not a thing that should just be happening normally . . . nobody is like, “Oh, let’s talk about this” . . . nobody was ever like, “that’s not okay” until I went to the doctor . . . all the Black women I talk to are like, “that’s just life” . . . I don’t understand the silence. (25-year-old, high SES)

Here, silence served multiple purposes; however, women either had a general understanding that everybody knows not to talk about sex or remained unclear on the reasons why families avoided such conversations.

Even as women got older and wanted to take control of their health, they realized that they may not be comfortable talking to parents about certain health issues, such as side effects from birth control or pain during sex. For some, this may have translated into also avoiding talking about going to the doctor in the first place. For example, a woman who experienced pain during sex avoided telling her parents about her upcoming appointment for fear she would have to explain why she wanted to go to the doctor (23-year-old, low SES). She believed her parents shared the sentiment that people who were not sexually active (which they assumed about her) would not need to visit a family planning provider.

Patient–Provider Racial Concordance as Protection From Harm

Without prompting, women discussed previous health care encounters, including how patient–provider racial concordance influenced their perceptions about engaging in the health care system. Some women shared that past experiences with same race providers were markedly different from health care experiences with racially and ethnically discordant providers.

I was in college . . . I used my school’s health services and saw a provider there . . . the provider was not Black but she was a woman . . . I feel like from that experience I knew going forward that as much as I could, I would try to seek out a Black woman to talk about with these things. ’Cause I didn’t feel a connection . . . or all that comfortable with my visits with this health services provider. (27-year-old, high SES)

Other women were concerned about how providers would treat them if the provider was White. Through vicarious experience, a woman became concerned about having a White provider because:

You hear so many things on the news . . . I’m not going to go in with my guard down . . . especially if it’s not someone I could relate to on an ethnic level or race level . . . I did feel more apprehensive with it being a White doctor . . . I had to make sure that she was going to provide me care not because of my race or not provide me care because of my race, but just provide me care because I was someone trying to get birth control. (19-year-old, high SES)

Previously, this young woman described having a good relationship with a White pediatrician years ago but perceived that interactions with a White family planning provider would be different. She highlights a conundrum Black women face—They are unsure whether methods will be “pushed” on them because they are Black or they will not receive the help they seek because they are Black. Another woman, who moved from the deep South to another southern state for school, described scrolling through the university clinic’s website to see which provider “looked less racist” (25-year-old, high SES). She had experienced overt racism since moving to the new state and was concerned that she might experience similar treatment in the FPC setting.

Women assumed the odds of them being able to navigate the health care setting with a White provider were more limited than with a Black provider, thus resulting in a potentially less than positive health care experience. While many women perceived having a Black provider reduced the threat of mistreatment, a few women had different experiences with their Black provider. One woman reported feeling “disappointed” because she assumed having a Black female provider would ensure a positive experience; however, she did not describe that visit positively (26-year-old, low SES). Despite a participant wanting to switch providers upon discovering her gynecologist had written “non-compliant” in her chart because she declined using a hormonal birth control method, she decided to continue seeing this provider, because “she’s a Black woman, so I kinda figure it’s hard to find a Black woman OB/GYN so I’ll probably end up staying with her, especially after all these years” (27-year-old, high SES). Therefore, maintaining a relationship with a Black provider—even when the patient did not like the care received—was better than risking getting a non-Black provider. Overall, women perceived racially concordant care as a protective factor that would result in fewer problems than discordant care.

Providers as a Source of Discouragement and Misinformation

When providers offered information to assist women in decision making, they often ignored women’s preferences and, in some cases, discouraged women from using their preferred method. Women also received misinformation from providers or were advised to consider methods in which they expressed little or no interest. Patients not interested in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods told their provider early in the discussion that they would not be selecting a LARC method and they remained firm on that stance—a position their providers respected. However, several women who came to the visit wanting a LARC or interested in learning more about LARC were discouraged or given misinformation: being told that the IUD contained a large amount of hormone that was not good for young women who had never given birth, provided incorrect information about insertion procedures, discouraged from pursuing an IUD because the clinic they attended did not offer that method, or encouraged to use a daily option even after several failed attempts (i.e., repeatedly forgetting to take her oral contraceptive pills [OCPs]). One woman decided against the IUD after her provider said that they would have to “drill in the cervix” to insert the device (28-year-old, high SES). A couple of women had to remind themselves of why they initially wanted to use LARC when they left their visits with no explicit plans to obtain it. In the case of the woman who was encouraged to give OCPs another try, she received a prescription for OCPs when she did not want to restart that method. Similar to that experience, other women had already discontinued their hormonal methods prior to the visit and contemplated restarting the method or learning about other non-hormonal options. Women with little to no interest in using hormonal methods received less information and support than those who considered hormonal options.

Frustration as a Normative Experience During FPC

Women who reported having a negative care experience often described experiencing frustration while talking to their provider. One of the key indicators of a woman likely to experience frustration was her stating that provider did not listen to and acknowledge her needs or concerns. Women attended visits with the expectation that their provider would offer greater assistance than what they could achieve alone; however, a shift occurred in the visit once women realized that the provider did not take their concerns seriously. As one woman stated,

I was just frustrated with having to deal with the issues I was dealing with [symptoms from endometriosis] and I felt nervous about describing those feelings . . . throughout the appointment, I became more and more frustrated as we were having a conversation because I felt I wasn’t being heard . . . that it wasn’t a big deal. (26-year-old, low SES)

When feelings of frustration occurred, some women were able to overcome this barrier to communication with their provider; however, many women shared that they began to “shut down.” A woman who experienced cysts popping on her ovaries during menses scheduled a visit to find relief; however, she left her visit upset, discouraged, and planning to “go to a completely different doctor . . . maybe next year when it’s time for my annual” (28-year-old, low SES) because her provider did not acknowledge her pain or take finding solutions to relieve the pain seriously. When asked to provide advice to providers, she drew upon her most recent experience:

. . . take physical pain more seriously without me having to . . . get out of character . . . I should not have to contemplate having to take it to that level of rage in order for you to get something done. (28-year-old, low SES)

After dealing with a disengaged provider or one who did not take women’s pain seriously, women became frustrated and spent time during the visit trying to regulate their emotions or protect themselves from further harm.

Decision Making Excludes Discussion and Deliberation

Information regarding the decision-making process during these visits was limited, and few women described mutual decision making or deliberation between them and their provider. Several women mentioned that providers failed to ask them about their preferences for birth control or satisfaction with the current method they were using. Others mentioned how providers did not ask if they had any questions or allow time at the end of the visit for questions. One woman complained that her provider did not share enough information with her so that she could make an informed decision but told her that she would support any decision that was made. Initially, she appreciated this support; however, following her visit, she realized that she still felt ill-informed, which caused inaction.

At the conclusion of women’s visits, the following occurred—Two women who wanted IUDs received them soon after their visit: re-insertion of an expelling IUD and a new IUD insertion. One woman who wanted to get a regular period and selected NuvaRing with the help of her provider received a prescription at her visit. A few women received prescriptions for OCPs. Those who considered discontinuing or switching their OCP had providers encourage them to continue using the same method, and one provider told a woman to “double up.”

All the women who had discontinued their method prior to the visit did not restart a method following their visit, even though two women received scripts. One woman even refilled her prescription with the pharmacy immediately after her visit yet never took the OCPs. Another woman, who had never used birth control before, still was not ready to decide on a method the day of her visit but felt that she was open to exploring options independently and with her provider in the future. Women perceived that providers were interested in getting them on a birth control method before they left the visit, even when decision making at the end of the visit was not in alignment with women’s preferences. Therefore, when a patient and provider could not reach a mutual decision, women left visits empty handed or women later decided to discontinue a method.

Medical Mistrust Is Pervasive and a Part of Black Consciousness

Experiencing frustration during the provider encounter also coincided with emerging feelings of mistrust. Women who had concerns about mistreatment by providers prior to the visit came with an understanding that “. . . medical professionals are not to be trusted in a lot of situations” (25-year-old, low SES). Other women had feelings that were specific to the encounter, such as feeling the provider was more interested in them starting or continuing birth control than ensuring their needs were met. Suspicion or thinking providers had an agenda that conflicted with their desires caused feelings of mistrust. Women’s mistrust in providers is demonstrated here:

. . . stigma that . . . Black women’ll . . . just start popping out babies if they’re not on birth control, babies that they can’t afford to have . . . so it’s like, get you on something, keep you on something . . . that visit put it into perspective. (27-year-old, high SES)

Another participant reluctantly shared that after her most recent visit, she wondered if her provider “maybe gets some type of commission out of giving certain birth controls because . . . it was a pressuring type thing to put me on birth control” (26-year-old, low SES). While some women had positive encounters with their provider, in general, women described an underlying sense that providers thought young Black women should be on birth control or avoid becoming pregnant.

Meaningful and Empathic Patient–Provider Encounters Are Elusive

One of the key components in descriptions of how women felt during the patient–provider interaction was comfort or the lack thereof. For most women who had positive feelings about the patient–provider interaction, women reported behaviors such as a warm welcome and rapport-building or small talk before the visit, which put women at ease. Women further described how providers listened to, understood, and validated their thoughts and feelings. Women also appreciated transparency and anticipatory guidance (i.e., what to expect during the visit). As one woman described, her provider comforted her by being attentive to her needs: “she introduced herself. She was super friendly . . . she explained what she was going to do . . . I guess [she] could tell I was nervous . . .” (20-year-old, low SES). Another woman remarked about how surprised she was to discover that her provider was “actually” listening to her during the visit. The provider never made her feel as though she was sharing “all this unnecessary information . . . ” and she also observed that the provider “really listened intently and then would repeat certain details. I was like, ‘Okay. Wow, she’s listening. This is actually important’” (23-year-old, low SES). Following early and ongoing rapport-building with patients, women felt more comfortable talking to providers and being transparent about their concerns and preferences.

Another characteristic of a good patient–provider encounter was when women felt, or had a way to find, a connection with their provider. Connections formed between patients and providers were intentional and unintentional, and often contributed to women’s overall perception of the visit. As one woman stated,

I’m a very spiritual person . . . I felt a connection to her, like my soul received her . . . she’s being very thorough with me . . . took her time . . . she did a really good job. (20-year-old, low SES)

Participants who may have only experienced “intentional” connections with a provider observed their provider trying to be personable, engaging, listen to them, and meet their needs. In contrast, women dissatisfied with the patient–provider interaction felt that providers ignored their concerns or did not put any effort in helping them understand their health problems or family planning options.

Women who maintained nervous and anxious feelings or negative and neutral feelings during the patient–provider interaction did not describe the same level of open patient–provider communication or emotional or physical comfort as women who reported positive experiences. Several women described experiencing anxiety or nervousness prior to the visit that remained throughout the visit and others had negative feelings emerge during the visit. During FPC with a White male provider, a participant (20-year-old, high SES) shared about her recent hair loss and weight gain. She described experiencing severe embarrassment that she was not able to overcome during the visit:

. . . I was telling him about my problems . . . and he shot me down. I felt embarrassed and dumb . . . “okay, he knows more than me” . . . maybe I shouldn’t have told him that . . . now I feel dumb . . . maybe it isn’t my birth control. (20-year-old, high SES)

When women perceived mistreatment or a lack of support from providers, they began to doubt themselves and withdraw to avoid any additional negative feelings.

A couple of women experienced physical pain during their visits that contributed to negative feelings. One woman suffered from vaginal pain upon penetration that made vaginal exams and sex painful. She shared this with her provider who did not believe her, causing her greater frustration. She illustrated with the following: “. . . I was making this face—it hurts. And she goes, ‘Really? This hurts? How are you regularly sexually active, but half an inch hurts? . . . really? Are you sure?’” (22-year-old, low SES). She later told her provider that she and her boyfriend had sex infrequently due to the severe pain. The other woman who experienced physical and emotional distress during her visit described the experience as unexpected because she had not had a similar reaction to a Pap test in some time. She said that her provider ignored her response, which included her crying and shaking her legs uncontrollably:

I felt like she kind of tried to block it out . . . just kept saying, “it’s almost over” . . . I just remember . . . crying, trying not to scream but I wanted to scream because I couldn’t take it no more . . . it was the longest procedure ever. (26-year-old, high SES)

In these examples, women experienced not only frustration but also embarrassment and disappointment that providers did not acknowledge their discomfort or pain. Women also described how experiencing physical pain caused them to experience negative emotions or how not feeling physically or emotionally supported by their provider caused additional distress.

Future Access to Health Care

Women who shared negative reflections about their most recent FPC visit described how these experiences made them wary of future interactions with this provider or health care interactions in general. Several women who had negative experiences said they would not be returning to their provider and, in some cases, women began to question whether they could trust their provider’s recommendations. Other women, who felt they had few options for FPC—particularly women whose main source of care was a university-based clinic—decided to change their expectations about future care experiences.

I feel like if I have to see her again or just pretty much any of them [other providers at the same clinic] . . . I’m not really going there with the expectation of getting actual help if that makes sense . . . let me just ask Google kind of thing . . . or let me see what other people in forums may have been experiencing and get my information from there rather than saying, “Oh, let me ask my gynecologist.” (20-year-old, low SES)

Following the most recent FPC visit, some women made conscious decisions to not seek advice from medical providers but to rely on friends, peers, or information from the internet.

Women also shared concerns regarding future fertility and referenced recent news coverage on Black infant and maternal mortality rates, conversations with others regarding providers’ poor treatment of Black women, including a lack of empathy and provider assistance with pain management, and other concerns related to future health care visits. As one woman expressed,

the nightmare stories that I’ve heard about Black women and the lack of care they receive while pregnant, while in labor . . . makes me want to not have a child anytime soon . . . makes me want to avoid being pregnant. (25-year-old, low SES)

Most women described not being ready to start a family right now, but because of providers treatment of them or how they perceived providers to treat other Black women in health care settings, they worried about future encounters, health decision making, and health management. Regardless of the experience at their most recent visit, many women described not being able to trust that providers would treat them well at future FPC or prenatal care visits.

In women’s advice to providers on how to improve care for young Black women, women suggested that providers recognize the sociopolitical context in which women are engaging in care and how Black women often do not receive the best care—as one participant asked, “. . . when is health care going to actually be care?” (24-year-old, low SES). As women in this sample were highly educated and childless, some also mentioned that providers should stop making assumptions about women because of their sociodemographic background, as Black women have been “. . . seen as less educated . . . lazy . . . reliant on government assistance . . . have so many children” (19-year-old, high SES). Women also suggested that engaging in the health care system was scary and that doctors could make encounters less so by observing that women are “probably scared and comfort her” (20-year-old, low SES). Ultimately, most women agreed that key way to ensure young Black women have a good care experience was to make them feel heard and validated.

Discussion

This study describes the lived experience of FPC among Black women, ages 18 to 29 years, in the United States. FPC encounters ranged from useful and supportive encounters to unsatisfactory—and sometimes emotionally and psychologically harmful—encounters. Characteristics of a positive experience included providers validating patients’ feelings and past experiences, providing enough information to inform patients’ decision making, and including friendly and attentive care delivery throughout the visit. Negative aspects such as feeling ignored and invalidated during the patient–provider interaction were so significant; women generally described these encounters negatively overall. FPC visits were dynamic interactions influenced by individual characteristics (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, previous experiences, biology, and medical history), the patient–provider encounter, and structural factors that exist within the care context (i.e., racism, discrimination, bias).

While phenomenology lends itself to creating new theories, findings from this study align with an existing framework, cultural health capital (Shim, 2010). Derived from Bourdieu’s (1977) cultural capital—a theory describing the way cultural practices and behaviors present and function in society and are the result of our cultural upbringing and social environment—cultural health capital helped describe and elucidate the interplay between the multiple dimensions of FPC in the interpretation of the findings. Underpinnings of the cultural capital framework align with the intersectionality perspective in that social identities relate to power structures in society that distribute privilege and disadvantage. The cultural health capital framework considers the historical and current care context in interrogating how patient–provider interactions help to perpetuate inequities based on a dynamic set of patient and provider characteristics and interactions. Thus, it is with this lens that we view young Black women’s experiences in the FPC context whereby they approached visits with socially marginalized identities, existing knowledge, beliefs, and skills (i.e., cultural health capital), and engaged in a system that historically has oppressed them. Young Black women’s narratives in this study highlight their vulnerability and resilience in navigating the FPC context and managing their sexual and reproductive health, including engaging in FPC. Therefore, we frame the discussion in this article as experiences that cultivate cultural health capital and points of vulnerability for young Black in the FPC context.

Women’s narratives about FPC highlighted exposure to structural traumas, including provider disengagement, provider bias, and medical mistrust. Women who reported negative care experiences described providers as disinterested in assisting them or unempathetic to them (regarding experiences, feelings, or pain) during care. These narratives indicated gaps in rapport-building and relationship development between patients and providers that could facilitate patient satisfaction with the visit. Reasons for patient perceived provider inattention may be due to structural barriers, which diminish young Black women’s engagement in FPC. As described in the cultural health capital framework, the health care system is a power structure that distributes privilege and disadvantage. Moreover, Shim (2010) suggests that the existence or intersections of historically marginalized social identities among patients are more associated with receipt of disadvantage than privilege. Women, in this study, as in other studies (Gomez et al., 2019; Higgins, 2017; Yee & Simon, 2011b), described providers not being personable, not taking time with them, ignoring and invalidating their pain and experiences, not answering their questions or helping them make decisions, or mistreating them. As previously described in the literature (Dale et al., 2010), young Black women desire a provider who is interested in them and their issues, exhibits a positive attitude and body language (e.g., moving close to the patient instead of away from), and provides information and education in a way they can understand. Examples of negative experiences such as these also signal disinvestment in Black women’s overall biopsychosocial health. The consequences of disinvestment by the health care system may produce negative outcomes, such as women lacking satisfaction with their health care experience (Amico et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2016; Sacks, 2018) or method of birth control (Gomez & Wapman, 2017), women not returning to care or seeking medical advice from a health care professional (Amico et al., 2016; Dickerson et al., 2013; Higgins, 2017), increased medical mistreat, or having fear about future fertility and reproductive health care.

As described in the literature, structural barriers, such as racism, discrimination, and bias due to a patients’ racial or ethnic identity (or some other identity), are critical components of differential treatment in health care (Nelson, 2002). As posited by the cultural health capital framework, providers “reward” patients with assistance during care visits when they speak the same language as their provider and when there is concurrence or similarity between patients’ and providers’ thoughts, opinions, and approaches to care and health management (Dubbin et al., 2013). Therefore, when patients do not possess these characteristics, they may be subject to provider bias and mistreatment during care. During interviews, some women considered reasons for negative encounters. Many women were unclear about what might have contributed to their experience; however, some identified the intersections of race and age as a potential cause for provider bias. Specifically, women perceived that providers subscribed to stereotypes about Black women, particularly stigma around Black teen moms, poor women who cannot independently support their offspring financially, and other pervasive stereotypes about Black women (Crooks et al., 2019; Roberts, 2014; Ross & Solinger, 2017; Sacks, 2018). Previous literature on FPC shows that young women and women of color experience provider bias during the care visit, including provider pressure to initiate or continue birth control (e.g., refusal to remove LARC method) or use methods providers prefer (Amico et al., 2016; Gomez & Wapman, 2017; Higgins et al., 2016). This highlights how provider bias may reduce the likelihood that certain patients, particularly those with multiple marginalized identities, report positive health care encounters, feel validated and heard, or have opportunities to ask questions and obtain enough information to make decisions that align with their preferences.

Among women in the present study, perceiving provider bias and mistreatment due to their racial identity coincided with feelings of mistrust. Scholars have re-framed the prevalence of medical mistrust among communities of color as an appropriate response to historical and ongoing mistreatment by the health care system and an indicator of how people of color understand their position in society (Jaiswal & Halkitis, 2019). Women’s suspicions about their providers’ intentions regarding recommendations for family planning indicate an ongoing dilemma in FPC that health systems must address. One method for mitigating this issue is by improving patient–provider relationships and care experiences for young Black women.

Despite significant barriers to engage in care without harm, young Black women demonstrated resilience and provided clear examples of how FPC encounters can increase their cultural health capital, including trust in providers. Women with positive experiences expressed greater comfort asking questions, scheduling future visits, and managing encounters to get the results they needed. Women’s confidence in navigating the health care system increased after they experienced a positive patient–provider interaction. Black women have also previously discussed how a lack of communication about sex with parents while growing up limited their ability to seek and engage in care and learn about their bodies and reproductive health (Crooks et al., 2019; Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010). Therefore, experiential knowledge may be critical for young Black women as they begin to independently attend FPC visits, initiate conversations about family planning, and share sensitive information about sex behaviors and reproductive health problems with health care providers (Shim, 2010). Providers can help foster and cultivate cultural health capital in young Black women who may not have had opportunities to obtain the necessary skills and resources to achieve their health goals and needs independent of the health care system.

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations in the current study involve study design, recruitment, recall, and social desirability bias. The study had a transformative parallel mixed-methods design where survey completion before interview participation may have changed the nature of women’s narratives. We used purposive sampling to recruit women for interviews; however, the criteria could have been more stringent to restrict women’s participation to only those who had the expressed need of talking about starting, stopping, or switching birth control. Most patients had their most recent visit 6 months before completing the survey. By the time women completed both interviews, more time had elapsed, thus increasing the likelihood of recall bias. Also, during interviews, women may have responded in a way they thought would be favorable to the researcher or limit their discomfort when sharing about their experience in detail. This study also excluded the perspectives of providers who may have varying degrees of cultural health capital that influenced whether women increased or decreased their cultural health capital during encounters. In addition, literature is emerging related to eliciting providers’ perspectives and understandings of contraceptive coercion (Tarzia et al., 2019) and how to mitigate its negative effects, but more work is needed.

Strengths of the study include use of intersectionality in conjunction with phenomenology. Use of an intersectionality perspective and interrogation of the lived experience of FPC among young Black women helped to center and elevate the knowledge and expertise of this population while identifying opportunities for improving care delivery. Although extant literature focuses on mistreatment during perinatal care delivery (Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020; Vedam et al., 2019), more work is needed to examine the experience of mistreatment throughout women’s reproductive health care trajectories, including pregnancy and perinatal care. Thus, this study contributes to existing literature regarding the basic elements for improving care for Black women (Crooks et al., 2019; Gomez & Wapman, 2017; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020; Sacks, 2013, 2018; Warren-Jeanpiere et al., 2010) using frameworks and methods that center social and reproductive justice along with the experiences of Black women. Future research should acknowledge the pervasiveness of medical mistrust and structural barriers to care for young Black women and employ structurally competent frameworks (e.g., cultural health capital) in their assessment of health care inequities, including ones that highlight the strength and resilience of marginalized populations (Sumbul et al., 2020).

Implications

While it is important to acknowledge how patients can benefit from obtaining additional skills to increase their health awareness and knowledge, such skills cannot withstand systemic and structural inequity (Downey & Gómez, 2018). Therefore, the family planning and health care delivery system needs to build and cultivate cultural health capital through investment in patients—particularly populations who report worse health care experiences and outcomes. Approaches to improve the FPC experiences of young Black women should be multifaceted. First, conscientious providers could greet patients in a friendly manner, ensure adequate time to discuss issues and ask questions, and exhibit qualities of active listening. In addition, providers can create opportunities for patients to engage in dialogue, including discussion about perceptions and experiences with family planning methods and what method(s) might be best for them. Care models, such as person- or client-centered care (Goldberg et al., 2017; World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Program [CCP] Knowledge for Health Project, 2018), relationship-centered care (Dehlendorf et al., 2014), and trauma-informed care models (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014), may provide the tools and resources needed to improve current FPC delivery. To systematically build and cultivate cultural health capital during FPC visits, institutions should examine the structure of visits, information-sharing, and counseling practices, including information delivery, and how clinicians and staff help patients navigate visits. Furthermore, institutions can enhance care experiences by exploring their role in naming, acknowledging, and dismantling systemic and structural inequities that perpetuate disadvantage.

Conclusion

Women’s descriptions of the patient–provider interaction showed how providers can positively or negatively affect their cultural health capital. Women who had positive FPC experiences reported feeling comfortable making health decisions, considering their family planning options, continuing birth control, and navigating health care encounters in the future. Those who had negative experiences became distrusting of providers, discontinued birth control, and were concerned about future care encounters. Future studies should measure the effects of cultural health capital on decision making, satisfaction, and health care utilization. Also, future research should assess the cumulative and long-term effects of cultural health capital to determine how it might be leveraged to reduce long-standing health care inequities and outcomes. Providers’ investment in young Black women during FPC visits may foster relationship building, cultivate cultural health capital, and, ultimately, reduce persistent FPC and health inequities.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-qhr-10.1177_1049732321993094 for “When Is Health Care Actually Going to Be Care?” The Lived Experience of Family Planning Care Among Young Black Women by Rachel G. Logan, Ellen M. Daley, Cheryl A. Vamos, Adetola Louis-Jacques and Stephanie L. Marhefka in Qualitative Health Research

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Taylor Livingston from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln for her insights on the cultural health capital framework.

Author Biographies

Rachel G. Logan PhD is a public health research consultant at The Equity Experience. Dr. Logan is interested in sexual and reproductive health equity, reproductive justice, and understanding the social and structural determinants of health that disproportionately impact Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color.

Ellen M. Daley PhD is the Associate Dean for Translational Research and Practice and a Professor at the College of Public Health. Dr. Daley is a behavioral researcher with interests in women’s health, health literacy, reproductive health, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) prevention, adolescent health, and health risk-taking behaviors.

Cheryl A. Vamos PhD is an Associate Professor and Fellow with the Chiles Center for Women, Children, and Families. Dr. Vamos uses health literacy, implementation science, and technology approaches to ensure women and providers have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to be empowered and make informed decisions.

Adetola Louis-Jacques MD is a Maternal-Fetal Medicine physician and Assistant Professor in the Morsani College of Medicine. Dr. Louis-Jacques focuses on disparities in lactation and understanding the impact of lactation on maternal health across the lifespan.

Stephanie L. Marhefka PhD is a Professor and Assistant Dean for Research at the College of Public Health. Dr. Marhefka’s mixed-methods research has focused primarily on two areas: improving care and services for people living with HIV; and supporting positive child health outcomes through breastfeeding promotion.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: Rachel Logan disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the, University of South Florida Graduate School Dissertation Completion Fellowship, and a stipend from the University of South Florida College of Public Health to attend the Intersectional Qualitative Research Methods Institute for Advanced Doctoral Students (IQRMI-ADS) at the Latino Research Institute at the University of Texas at Austin.

ORCID iDs: Rachel G. Logan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7686-5754

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7686-5754

Adetola Louis-Jacques  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2119-9739

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2119-9739

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Abrams J., Tabaac A., Jung S., Else-Quest N. (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113138. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico J. R., Bennett A. H., Karasz A., Gold M. (2016). She just told me to leave it: Women’s experiences discussing early elective IUD removal. Contraception, 94(4), 357–361. 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D., Klassen A. C., Koenig M. A., LaVeist T. A., Sonenstein F. L., Tsui A. O. (2009). Women’s perspectives on family planning service quality: An exploration of differences by race, ethnicity and language. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(3), 158–165. 10.1363/4115809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. 10.1177/1468794112468475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero S., Schwarz E. B., Creinin M., Ibrahim S. (2009). The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States. Journal of Women’s Health, 18(1), 91–96. 10.1089/jwh.2008.0976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (Vol. 16). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Crenshaw K. W., McCall L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. 10.1086/669608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cipres D., Rodriguez A., Alvarez J., Stern L., Steinauer J., Seidman D. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in young women’s health-promoting strategies to reduce vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 556–562. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, Article 8. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks N., King B., Tluczek A., Sales J. M. (2019). The process of becoming a sexual Black woman: A grounded theory study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 51(1), 17–25. 10.1363/psrh.12085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H. E., Polivka B. J., Chaudry R. V., Simmonds G. C. (2010). What young African American women want in a health care provider. Qualitative Health Research, 20(11), 1484–1490. 10.1177/1049732310374043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf C., Krajewski C., Borrero S. (2014). Contraceptive counseling: Best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 57(4), 659–673. 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson L. M., Diaz V. A., Jordan J., Davis E., Chirina S., Goddard J. A., Carr K. B., Carek P. J. (2013). Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long-acting reversible contraception. Family Medicine, 45(10), 701–707. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24347187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard J. P., Shen L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. 10.1080/03637750500111815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downey M. M., Gómez A. M. (2018). Structural competency and reproductive health. AMA Journal of Ethics, 20(3), 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing R. A., LaVeist T. A., Bullock H. E. (2007). Intersections of ethnicity and social class in provider advice regarding reproductive health. American Journal of Public Health, 97(10), 1803–1807. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbin L. A., Chang J. S., Shim J. K. (2013). Cultural health capital and the interactional dynamics of patient-centered care. Social Science and Medicine, 93, 113–120. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer L. B., Zolna M. R. (2016). Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(9), 843–852. 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2002). Outing the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 531–545. 10.1177/104973202129120052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost J. J., Zolna M. R., Frohwirth L. (2013). Contraceptive needs and services, 2010. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/contraceptive-needs-2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D., Sahgal B., Beeson T., Wood S. F., Mead H., Abdul-Wakil A., Stevens H., Rui P., Rosenbaum S. (2017). Patient perspectives on quality family planning services in underserved areas. Patient Experience Journal, 4(1), 54–65. 10.35680/2372-0247.1194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A. M., Arteaga S., Aronson N., Goodkind M., Houston L., West E. (2019). No perfect method: Exploring how past contraceptive methods influence current attitudes toward intrauterine devices. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1367–1378. 10.1007/s10508-019-1424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A. M., Wapman M. (2017, October 1). Under (implicit) pressure: Young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception, 96(4), 221–226. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. (2016. a). Contraceptive use in the United States. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/contraceptive-use-united-states

- Guttmacher Institute. (2016. b). Publicly funded family planning services in the United States [Issue September]. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contraceptive_serv.html

- Hall K. S., Dalton V., Johnson T. R. B. (2014). Social disparities in women’s health service use in the United States: A population-based analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 24(2), 135–143. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. A. (2017). Pregnancy ambivalence and long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) use among young adult women: A qualitative study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 49, 149–156. 10.1363/psrh.12025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. A., Kramer R. D., Ryder K. M. (2016). Provider bias in long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) promotion and removal: Perceptions of young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 106(11), e1–e6. 10.2105/ajph.2016.303393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal J., Halkitis P. N. (2019). Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 79–85. 10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjerulff K. H., Frick K. D., Rhoades J. A., Hollenbeak C. S. (2007). The cost of being a woman: A national study of health care utilization and expenditures for female-specific conditions. Women’s Health Issues, 17(1), 13–21. 10.1016/j.whi.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manze M. G., McCloskey L., Bokhour B. G., Paasche-Orlow M. K., Parker V. A. (2016). The perceived role of clinicians in pregnancy prevention among young Black women. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 8, 19–24. 10.1016/j.srhc.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morse J. M., Mitcham C. (2002). Exploring qualitatively-derived concepts: Inductive—Deductive pitfalls. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(4), 28–35. 10.1177/160940690200100404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(8), 666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A., Dominguez T. P., Hammond W. P., Leu J., Skaff M., Egerter S., Jones C. P., Braveman P. (2009). It’s the skin you’re in: African-American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13(1), 29–39. 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. (2014). Killing the black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. Vintage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg B. D., Navarro M. A. (2018). Semantic differential scaling. In Frey B. B. (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. 10.4135/9781506326139.n624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L., Lobel M. (2020). Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethnicity & Health, 25, 367–392. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. (1994). Sterilization and de facto sterilization. The Amicus Journal, 29. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0028675699&partnerID=40&md5=97b5888e8de02deec06032f3901da7d0 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L., Solinger R. (2017). Reproductive justice: An introduction (Vol. 1). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks T. K. (2013). Race and gender concordance: Strategy to reduce healthcare disparities or red herring? Evidence from a qualitative study. Race and Social Problems, 5(2), 88–99. 10.1007/s12552-013-9093-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks T. K. (2018). Performing Black womanhood: A qualitative study of stereotypes and the healthcare encounter. Critical Public Health, 28(1), 59–69. 10.1080/09581596.2017.1307323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. 10.1111/j.1744-618X.2000.tb00391.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J. K. (2010). Cultural health capital: A theoretical approach to understanding health care interactions and the dynamics of unequal treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1), 1–15. 10.1177/0022146509361185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. http://store.samhsa.gov

- Sumbul T., Spellen S., McLemore M. R. (2020). A transdisciplinary conceptual framework of contextualized resilience for reducing adverse birth outcomes. Qualitative Health Research, 30(1), 105–118. 10.1177/1049732319885369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzia L., Wellington M., Marino J., Hegarty K. (2019). A huge, hidden problem: Australian health practitioners’ views and understandings of reproductive coercion. Qualitative Health Research, 29(10), 1395–1407. 10.1177/1049732318819839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A., Teddlie C. (2010). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn S., Bogart L. M. (2005). African American women and family planning services: Perceptions of discrimination. Women and Health, 42(1), 23–39. 10.1300/J013v42n01_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services—Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/family-planning

- Vedam S., Stoll K., Taiwo T. K., Rubashkin N., Cheyney M., Strauss N., McLemore M., Cadena M., Nethery E., Rushton E., Schummers L., Declercq E. (2019). The giving voice to mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 77. 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren-Jeanpiere L., Miller K. S., Warren A. M. (2010). African American women’s retrospective perceptions of the intergenerational transfer of gynecological health care information received from mothers: Implications for families and providers. Journal of Family Communication, 10(2), 81–98. 10.1080/15267431003595454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams V., Smith A. A., Villanti A. C., Rath J. M., Hair E. C., Cantrell J., Teplitskaya L., Vallone D. M. (2017). Validity of a subjective financial situation measure to assess socioeconomic status in us young adults. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 23(5), 487–495. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Program (CCP) Knowledge for Health Project. (2018). Family planning: A global handbook for providers. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fp-global-handbook/en/

- Yee L. M., Simon M. A. (2011. a). Perceptions of coercion, discrimination and other negative experiences in postpartum contraceptive counseling for low-income minority women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(4), 1387–1400. 10.1353/hpu.2011.0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee L. M., Simon M. A. (2011. b). Urban minority women’s perceptions of and preferences for postpartum contraceptive counseling. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 56(1), 54–60. 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00012.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-qhr-10.1177_1049732321993094 for “When Is Health Care Actually Going to Be Care?” The Lived Experience of Family Planning Care Among Young Black Women by Rachel G. Logan, Ellen M. Daley, Cheryl A. Vamos, Adetola Louis-Jacques and Stephanie L. Marhefka in Qualitative Health Research