Abstract

Background:

A sense of meaningfulness is an important initial indicator of the successful treatment of addiction, and supports the larger recovery process. Most studies address meaningfulness as a static trait, and do not assess the extent to which meaningfulness might vary within an individual, or how it may vary in response to daily life events such as social experiences.

Methods:

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) was used to: 1) examine the amount of within-person variability in meaningfulness among patients in residential treatment for prescription opioid use disorder; 2) determine whether that variability was related to positive or negative social experiences on a daily basis; and 3) assess whether those day-to-day relationships were related to relapse at four months post-treatment. Participants (N=73, 77% male, Mage=30.10, Range=19–61) completed smartphone-based assessments four times per day for 12 days. Associations among social experiences, meaningfulness, and relapse were examined using multilevel modeling.

Results:

Between-person variability accounted for 52% (95% CI = 0.35, 0.67) of variance in end-of-day meaningfulness. End-of-day meaningfulness was higher on days when participants reported more positive social experiences (β = 1.17, SE = 0.33, p < .05, ΔR2 = 0.041). On average, participants who relapsed within four months post-residential treatment exhibited greater within-day reactivity to negative social experiences (β = −1.89, SE = 0.88, p < .05, ΔR2 = 0.024) during treatment than participants who remained abstinent.

Conclusion:

Individual differences in maintaining meaningfulness day by day when faced with negative social experiences may contribute to the risk of relapse in the early months following residential treatment.

Keywords: Ecological momentary assessment, opioids, meaningfulness, social experiences, relapse

1. Introduction

Recovery from addiction is a process that goes beyond simple abstinence from substance misuse: It is the process of learning to thrive without substance misuse. Formal definitions of recovery aligning with this broader conception describe it as, “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness” (SAMHSA, 2011), and as a “dynamic” process, “resulting in and supported by…enhanced quality of life” (Kelly & Hoeppner, 2015). Even when measuring recovery beyond abstinence, however, most research has focused on understanding between-person differences in recovery success. Yet, if recovery is dynamic, the intrapersonal states that directly contribute to recovery wellness and the interpersonal experiences that may impact such intrapersonal states should also be investigated as dynamic, within-person processes.

In the current study, we used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data, collected from patients in residential treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), to: 1) document the day-to-day variability in individuals’ sense of meaningfulness, an intrapersonal state that supports recovery wellness; 2) evaluate the association between daily variation in meaningfulness and same-day interpersonal social experiences; and 3) determine if these within-day linkages are associated with post-treatment abstinence.

1.1. Meaningfulness

Meaningfulness refers to the extent to which individuals make sense of their lives and perceive themselves to have an overall purpose (Machell et al., 2015; Steger, 2009). Having a sense of meaningfulness also involves making decisions consistent with one’s personal values and goals and engaging in fulfilling activities. As Roos et al. (2015) point out, meaningfulness-related concepts are important components of several highly utilized approaches for treating substance use disorders. For example, 12-step facilitation and Alcoholics Anonymous, motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), and mindfulness-based relapse prevention (Bowen, Chawla, & Marlatt, 2010) all involve, to varying degrees, helping individuals reflect on and connect to their core values, goals, and over-arching aims in life.

Meaningfulness is also an important aspect of the health and wellness captured in definitions of recovery, and is theorized to be a key indicator of treatment and recovery success (Laudet, 2011) and a core influence on the larger recovery process (SAMHSA, 2011). For example, meaningfulness is thought to help people overcome adversity by motivating behavior change (Wagner & Sanchez, 2002), and by serving as a coping resource that individuals utilize in moments of crisis, such as situations that present a high risk for relapse (Miller et al., 1996; Tonigan et al., 2001).

Indeed, meaningfulness-related constructs are associated with relapse. Lower scores on the Revised Purpose in Life questionnaire predict more days of cocaine and alcohol use 6 months post-treatment (Martin et al., 2011). Increasing scores on the Purpose in Life scale during treatment also predict lower likelihood of heavy drinking 6 and 9 months later (Robinson et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2011), whereas low levels of purpose in life are associated with heavy drinking (Marsh et al., 2003) and alcohol relapse (Miller et al., 1996; Waisberg & Porter, 1994). These associations between meaningfulness-related constructs and relapse support the importance of meaningfulness for treatment and recovery.

Despite these findings, research on meaningfulness and recovery is sparse. Furthermore, existing studies typically rely on methods that measure meaningfulness as a static, trait-like characteristic. When assessed repeatedly, however, meaningfulness has exhibited substantial within-person variability that is not captured by a single assessment. For example, King et al., (2006) found that the majority of variance in meaningfulness in a non-substance using sample existed at the within-person, rather than the between-person, level. Variability in meaningfulness might be expected to play an important role during significant life transitions such as initiating abstinence during OUD treatment.

1.2. Social Experiences

Social experiences can play an important role in supporting successful recovery. Both quality and frequency of positive social experiences have a demonstrated role in impeding or aiding long-term SUD recovery (e.g., peer-support, 12-step programs; Bassuk et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2020), whereas negative social experiences are often associated with craving (Cleveland & Harris, 2010) and substance use (Preston et al., 2018). Beyond supporting recovery generally, social connections have also been associated specifically with meaningfulness, hope, recovery validation, and quality of life (Best et al., 2012; Longabaugh et al., 2010). Because healthy social relationships often suffer as a result of addiction, positive social experiences that provide potentially hard-to-find emotional connection and support during the transition from initiating abstinence to long-term recovery (Jason et al., 2020) may be especially important for enriching individuals’ short-term meaningfulness. In contrast, negative social experiences may be particularly detrimental to meaningfulness, especially during the early stages of treatment and recovery when meaningfulness may be more susceptible to challenge.

Positive and negative social experiences stand out as particularly important influences on meaningfulness and recovery success because they are malleable—and therefore offer potential targets for clinicians. But social experiences are also momentary experiences, and few theories explain how these transient events influence both shorter-term outcomes, such as daily meaningfulness, and longer-term outcomes such as relapse. The relationships among social experiences and meaningfulness may differ not only across people (e.g., some individuals, on average, are better able to deal with negative social experiences than others), but may also differ within people (e.g., individuals may be better able to deal with negative social experiences on some days than others). Within-person linkages among social experiences and meaningfulness may capture individuals’ relative tendencies to experience enhanced meaningfulness related to positive social experiences and reduced meaningfulness when confronted by negative social experiences. Social experiences may have daily effects on local variation in meaningfulness, but the relationships between momentary events and daily meaningfulness may also explain some of the process through which social experiences influence relapse risk over time, particularly in the vulnerable period following the transition from residential treatment to stepped-down care.

The current study utilized ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to capture daily social experiences and end-of-day meaningfulness among patients in residential treatment for prescription OUD. We first validated our hypothesis that meaningfulness was sufficiently variable on a day-to-day basis to warrant within-person level analyses. We then tested two primary hypotheses. The first hypothesis was that positive and negative social experiences had direct, within-day effects on end-of-day meaningfulness, and that the degree of these effects varied across persons. We labeled person-level differences in the within-day associations among social experiences and end-of-day meaningfulness, meaningfulness reactivity. The second hypothesis examined whether and how meaningfulness reactivity during treatment was related to post-treatment relapse. It was hypothesized that individuals who relapsed post-treatment would exhibit less enhancement in meaningfulness in response to positive social experiences, and greater reductions in meaningfulness in response to negative social experiences, relative to individuals who did not relapse.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N = 73, 77% male, Mage = 30.10, SDage = 10.13, Range = 19–61) were patients recruited from the Caron Treatment Centers’ residential drug and alcohol treatment facility as part of a larger study investigating neural and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation and reregulation during residential treatment for prescription opioid dependence. Patients were recruited who met criteria for prescription opioid dependence (as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID; First, 2005), and Form-90D (Westerberg, Tonigan, & Miller, 1998)) and for whom prescription opioids were the primary substance used and the focus of treatment. All participants completed medically assisted withdrawal prior to enrollment, most within the 10–14 days prior to data collection. Participants were included if they were over age 18, scheduled to stay in residential treatment for at least 30 days, and willing to comply with the research protocol. Exclusion criteria included any reported history of major Axis I disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), traumatic brain injury, intravenous heroin use, or current use of any opiate agonist or antagonist. More information about the sample has been published elsewhere (Huhn et al., 2016; Lydon-Staley et al., 2017).

2.2. Procedure

All study procedures were approved by an institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent following a full explanation of the study protocol. Participants completed smartphone-based surveys 4 times per day for 12 consecutive days. A pre-set alarm notified participants that a survey was ready to be taken at early morning, late morning, mid-afternoon, and evening times that did not conflict with their treatment programs. The surveys took approximately 2–3 minutes each to complete. If participants did not take the survey after the first notification, they were notified again every 15 minutes for up to one hour, after which the survey was closed until the next assessment.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. End-of-day meaningfulness.

End-of-day meaningfulness was measured with four face-valid items on a continuous touchpoint scale with anchors at each end (0=Not at all, 100=Very). The items were, “Overall, how meaningful was your day?”, “Overall, how gratifying was your day?”, “Overall, how fulfilling was your day?”, and “Overall, how purposeful was your day?”. This scale, which is similar to Steger and colleagues’ (2008) Daily Meaning Scale, included a specific focus on the day as the unit of analysis. The items were highly correlated (r = 0.80 – 0.89), and therefore a composite measure of meaningfulness was created by averaging the scores for each individual for each day of the study. The reliability coefficient for the meaningfulness scale was Rc = 0.92, indicating that within-person change in meaningfulness was assessed with a high degree of reliability (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). In addition to the face validity of the items and the measure’s similarity to scales used in previous research, we further examined construct validity by testing associations between end-of-day meaningfulness and (1) other EMA variables in our dataset, and (2) trait-level variables assessed as part of the larger study. End-of-day meaningfulness was significantly positively related to daily positive affect (as assessed by the PANAS; β = 0.63), but unlike positive affect, was not significantly associated with daily negative affect. End-of-day meaningfulness was also significantly negatively related to measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Inventory; β = −0.76) and anhedonia (Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale; β = −2.09).

2.3.2. Positive and negative social experiences.

Positive social experiences (PSE) and negative social experiences (NSE) were measured three times per day (late morning, mid-afternoon, and evening) with five yes/no items each. NSE items were adapted from the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE) scale (Ruehlman & Karoly, 1991). PSE items were piloted in a collegiate recovery community (CRC) to capture positive social experiences that would support recovery, with individual items generated from interviews with CRC staff and members (Cleveland et al., 2010). The NSE items were, “Since last data entry, did someone… ‘lose his/her temper with you’, ‘get angry with you’, ‘get impatient with you’, ‘disagree with you’, ‘argue with you’”. The PSE items were, “Since last data entry, did someone… ‘compliment you’, ‘show you that they cared about you’, ‘express sympathy toward you’, ‘let you know they understand your problems’, ‘let you know they understand your stress’”. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Zhaoyang et al., 2021), responses to these items were coded as 0 (experience did not occur) or 1 (experience occurred) and summed across three surveys within each day to indicate the frequency of assessed NSE and PSE, respectively, for each participant for each day of the study.

2.3.3. Relapse.

Treatment outcome was determined using a combination of factors. Data collected from patients up to 120 days following discharge from residential included: 1) twice monthly reports via a telephone Interactive Voice Response System, with options for staff to call a friend/spouse if patient could not be reached; 2) hair samples at 30 and 90 days post-residential treatment; and 3) the treatment center provided random urine drug screen results from patients involved in their aftercare program. Hair samples, submitted to Quest Diagnostics by the patient or research staff member who collected the sample, were processed using a 5-panel opioid screen. Treatment outcome designations were assigned using a “best estimate” procedure in which all available data were reviewed by a committee consisting of six members, including a research psychiatrist, two clinical psychologists, and the study research staff (Klein et al., 1994). As is common among individuals primarily in treatment for opioid dependence, a significant portion of our sample had histories of poly-substance use and/or drug dependence (see Table 1). Because participants had to be abstinent from all substances except tobacco (tobacco cessation was strongly encouraged, but not mandatory) throughout the duration of the study as a function of staying at the residential treatment facility, and a major focus of the treatment program was on maintaining abstinence from the problematic use of all drugs (including, but not limited to, opioids), relapse was operationalized as the misuse of prescribed opioids; any use of non-prescribed opioids, illicit drugs, marijuana, or amphetamines; or return to heavy alcohol use (Falk et al., 2010; Sobell et al., 2003). Relapse to alcohol was only included if participants had a diagnosis related to alcohol misuse. As marijuana use was illegal at the time of data collection, and use constituted a legal violation, subsequent use of marijuana was also defined as relapse.

Table 1.

Drug dependence of participants at treatment intake

| Participant drug dependence | N |

|---|---|

| Poly-substance drug dependence (excluding tobacco) | 38 |

| Alcohol current dependence | 10 |

| Tobacco current dependence | 30 |

| Cannabis current dependence | 19 |

| Tranquilizer current dependence | 0 |

| Sedative current dependence | 12 |

| Steroid current dependence | 0 |

| Stimulant current dependence | 7 |

| Cocaine current dependence | 5 |

| Hallucinogen current dependence | 0 |

| Inhalant current dependence | 1 |

| Other current dependence | 1 |

2.3.4. Covariates.

Age (continuous variable of self-reported age) and sex (0=Female, 1=Male) were tested as covariates to control for potential between-person differences in meaningfulness. Age, but not sex, was significantly associated with meaningfulness and retained in the final model. Day of study (coded as days since study initiation so that intercepts described the first day of the study) was also included as a covariate to account for time as a third variable (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). A quadratic effect of time on meaningfulness was tested in addition to the linear effect of time but this effect was not significant. As such, the more parsimonious model was retained.

2.4. Data Analysis

We examined PSE and NSE as predictors of end-of-day meaningfulness using a multilevel modeling (MLM) framework that accommodated the nested nature of the data (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). PSE and NSE variables represented the frequency of assessed positive and negative social experiences, respectively, that a person described as having had occurred on a given day. Of note, daily sum scores were used instead of daily mean scores because items asked participants to record their number of PSE and NSE “since last data entry.” Given this time frame, if a survey was missed, counts would still include the entire day as participants filled in the gap by reporting all experiences they had since the last time they responded to the prompt. In this case, using a mean score would inflate the number of social experiences by assuming missing data were similar to, rather than accounted for in, non-missing data. Still, we compared our results to models using mean PSE and NSE scores, and the magnitude and direction of effects were similar. Further, within-person and between-person versions of the number of social experience surveys completed per day, as well as a within- by between-person interaction, were added to our multilevel models testing associations between PSE/NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness and differences by relapse status to examine whether results changed after controlling for the number of surveys completed by participants. We found that results did not differ. Next, variables representing average individual PSE and NSE (iPSE and iNSE, respectively) were computed for each participant as the mean of their repeated measures and included in the models, allowing us to examine both person-level and day-level effects of social experiences on end-of-day meaningfulness. iPSE and iNSE were sample-mean centered.

One participant did not provide any meaningfulness data, leaving 501 days nested within 72 participants. Additionally, relapse data were available for participants who transitioned to home environments, outpatient care, or step-down care following discharge from residential care, rather than transitioning to a second residential facility (n = 70). The three participants without relapse data were only excluded from analyses examining the relationship between meaningfulness reactivity and post-treatment relapse, leaving 486 days nested within 69 participants.

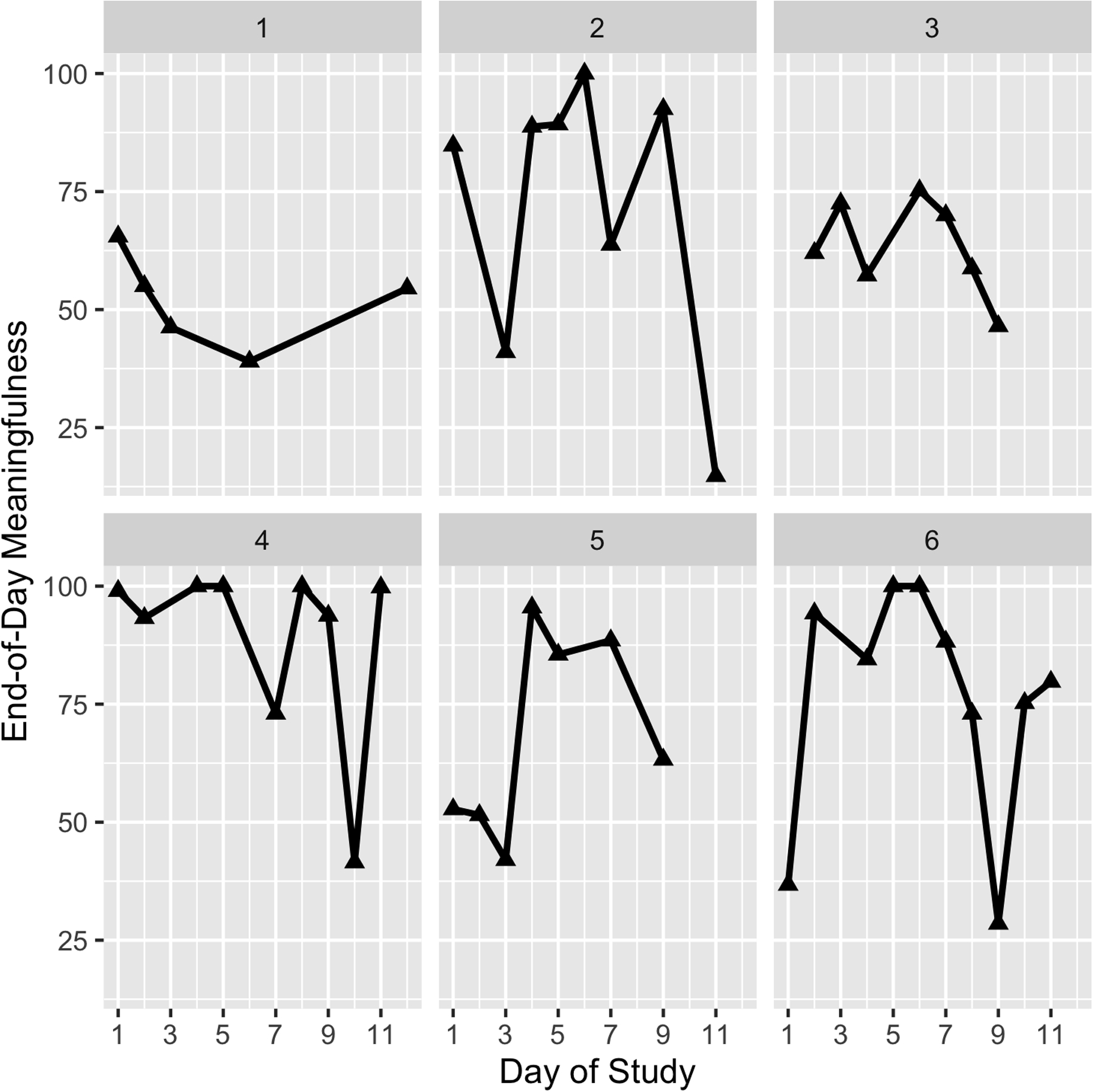

To examine the relative levels of within- and between-person variability in end-of-day meaningfulness, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated using a two-level bootstrap approach (Bliese, 2000). Figure 1 illustrates the amount and pattern of variability in end-of-day meaningfulness for a few participants.

Figure 1.

Within-person variability in end-of-day meaningfulness across the study period for a subsample of six participants. This figure demonstrates that there are between-person differences in both the level of end-of-day meaningfulness and in the amount of within-person fluctuation in end-of-day meaningfulness.

To test the first primary hypothesis that daily PSE and NSE were associated with end-of-day meaningfulness, a multilevel model was estimated regressing end-of-day meaningfulness on day- and person-level variables for PSE and NSE. To test the second primary hypothesis that post-treatment relapse was linked to meaningfulness reactivity during treatment, relapse status and its interactions with PSE and NSE were added to the multilevel model. A significant main effect association between relapse and meaningfulness indicates a difference in average levels of meaningfulness for participants who relapsed; a significant interaction between PSE and relapse status indicates a difference in the person-level relationship between PSE and meaningfulness (“meaningfulness reactivity”) for participants who relapsed. We chose this approach because we wanted to estimate the associations among social experiences and meaningfulness, and their links with post-treatment relapse, all in the same model. An alternative would have been to use a two-step approach (i.e., estimate “meaningfulness reactivity” slopes for each person in one model and use these estimates to predict relapse in a second model), but this method introduces bias by ignoring the error around the estimation of the slope parameters in the first step (Liu, Kuppens, & Bringmann, 2019). Instead, we elected to treat individuals who relapsed and those who abstained as two groups and look for systematic differences between them.

The final model was constructed as:

Level 1:

Level 2:

At Level 1, Meaningit is the reported meaningfulness for person i on day t; β0i indicates the expected level of meaningfulness on the first day of the study if all predictor variables are at zero for person i; Slopei indicates within-person differences in meaningfulness associated with day of the study; PMRi (“positive meaningfulness reactivity”) and NMRi (“negative meaningfulness reactivity”) indicate the impact of positive and negative social experiences on meaningfulness for each individual; and eit are day-specific residuals that were allowed to autocorrelate (AR1).

Person-specific intercepts and between-person variance from Level 1 were specified at Level 2, where gamma (γ) coefficients γ01 through γ04 represent person-level associations of age, average individual PSE, average individual NSE, and relapse, respectively, with meaningfulness. The γ00 parameter is the intercept and represents the level of meaningfulness predicted on the first day of the study for a typical person. The γ10 parameter represents the change in meaningfulness across each day of the study, averaged and fixed across all participants. Terms γ20 and γ30 are PSE and NSE reactivity parameters for each individual, respectively, and γ21 and γ31 indicate between-person differences in the within-person associations of day’s meaningfulness and PSE and day’s meaningfulness and NSE, respectively, for participants who relapsed. Models were tested with a random intercept (v0i), and with and without random slopes for PSE and NSE (v2i, v3i). Comparing models with and without random slopes, the AIC fit statistic indicated that the model with random slopes fit better than the model without random slopes, although BIC indicated a slight decrease in fit when including random slopes (most likely due to the harsher penalty imposed by BIC for model complexity). In addition, pseudo-R2 values were compared between the two models, and the model with random slopes explained more variance than the model without random slopes. Finally, substantive results did not differ between the two models. Thus, the model with random slopes for PSE and NSE was selected for interpretation.

In addition to comparing pseudo-R2 values between models with and without random slopes for PSE and NSE, pseudo-R2 calculations were also used to compare models to examine the variance uniquely attributable to each type of social experience. All models were fit using the nlme package in R (Pinheiro et al., 2015) using maximum likelihood estimation, with missing data handled using listwise deletion.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are shown in Table 2. ICC (r = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.35, 0.67) indicated that 52% of the variance in meaningfulness was explained by between-person differences, leaving 48% at the within-person level. Participants in our sample reported having 6.59 PSE (SD = 4.00, Range = 0–15) and 1.44 NSE (SD = 2.27, Range = 0–11) across three momentary assessments collected each day on average. It is worth noting that 93% of all reported days had at least one PSE, whereas 43% of all reported days had at least one NSE. At the person-level, 8.2% (N = 6) did not report any NSE across the 12-day study period; all participants reported at least one PSE. Additionally, 51% (N = 36) relapsed to any substance use following discharge from residential treatment.

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptive statistics for all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD | Range | ICC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-level | ||||||||

| Age | 30.10 | 10.13 | 19–61 | -- | ||||

| Relapse | 0.20*** | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0–1 | -- | |||

| Day-level | ||||||||

| Meaningfulness | −0.05 | −0.04 | 70.41 | 23.86 | 0–100 | 0.52 | ||

| Positive Social Experiences | 0.15*** | −0.14*** | 0.35*** | 6.59 | 4.00 | 0–15 | 0.38 | |

| Negative Social Experiences | −0.06 | −0.10* | −0.09* | 0.09* | 1.44 | 2.27 | 0–11 | 0.27 |

Note. M = Mean. SD = Standard deviation. ICC = Intraclass correlation coefficient.

p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05

Results from two multilevel models are shown in Table 3; Model 1 includes main effects only and Model 2 includes the significant interaction terms. All results reported in-text are from Model 2 unless otherwise noted. A significant within-day association between PSE and end-of-day meaningfulness (β = 1.17, SE = 0.33, p < .05) showed that, on average, patients’ end-of-day meaningfulness was higher on days when they experienced more PSE, controlling for iPSE, NSE and iNSE, age, and day of study. A significant random effect for PSE (Est. = 1.40, 95% CI = 0.89, 2.21) indicated that PSEs were more strongly associated with end-of-day meaningfulness for some patients than others. A significant patient-level association between iPSE and meaningfulness (β = 1.87, SE = 0.70, p < .05) indicated that patients who experienced more PSE on average had higher mean end-of-day meaningfulness than patients who, on average, experienced fewer PSE. We found that the main effect association between meaningfulness and relapse was non-significant (β = 6.61, SE = 4.05, n.s.), and that there were no differences in the associations between PSE and meaningfulness between patients who relapsed and those who did not (β = 0.44, SE = 0.64, n.s.).

Table 3.

Multilevel model results for associations of positive and negative social experiences with end-of-day meaningfulness.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | Est. | S.E. | Est. | SE. |

| Intercept | 78.54* | 5.85 | 75.87* | 5.97 |

| Age | −0.46* | 0.15 | −0.49* | 0.16 |

| Day | −0.15 | 0.24 | −0.17 | 0.25 |

| PSE | 1.19* | 0.32 | 1.17* | 0.33 |

| NSE | −1.25* | 0.49 | −0.41 | 0.62 |

| iPSE | 1.81* | 0.69 | 1.87* | 0.70 |

| iNSE | −0.24 | 1.20 | −0.44 | 1.20 |

| Relapse | 6.61 | 4.05 | ||

| Interactions | ||||

| NSE × Relapse | −1.89* | 0.88 | ||

| PSE × Relapsea | 0.44 | 0.64 | ||

| NSE × PSE × Relapsea | −0.09 | 0.14 | ||

| Random effects | Est. | CI | Est. | CI |

| Intercept variance | 19.19* | [14.7,25.0] | 19.69* | [15.3, 25.3] |

| PSE variance | 1.34* | [0.82,2.19] | 1.40* | [0.89, 2.21] |

| NSE variance | 1.94* | [1.09,3.47] | 1.65* | [0.73, 3.76] |

| Cor, intercept, PSE slope | −0.74* | [−0.9, −0.4] | −0.78* | [−0.9, −0.53] |

| Cor, intercept, NSE slope | −0.45 | [−0.8, 0.13] | −0.56* | [−0.8, −0.16] |

| Residual AR(1) | 0.07 | [−0.06, 0.2] | 0.07 | [−0.06, 0.19] |

| Residual variance | 16.38* | [15.1,17.7] | 16.58* | [15.3, 17.9] |

| Fit indices | ||||

| AIC | 4388.4 | 4266.1 | ||

| BIC | 4451.6 | 4337.3 | ||

Note. N patients = 72; N days = 501.

p < 0.05.

PSE = Positive social experiences. NSE = Negative social experiences. iPSE = Individual positive social experiences. iNSE = Individual negative social experiences. AIC = Akaike information criterion. BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Non-significant interaction term, removed from the final model.

A significant within-day association between NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness in Model 1 (β = −1.25, SE = 0.49, p < .05) showed that, on average, patients’ end-of-day meaningfulness was lower on days when they experienced more NSE, controlling for iNSE, PSE and iPSE, age, and day of study. NSE were also more strongly associated with end-of-day meaningfulness for some patients than others (Est. = 1.65, 95% CI = 0.73, 3.76). End-of-day meaningfulness did not differ across patients who reported more versus fewer NSE on average across study days (β = −0.44, SE = 1.20, n.s.). However, the within-day association between NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness from Model 1 was superseded by a significant interaction between relapse and NSE in Model 2 (β = −1.89, SE = 0.88, p < .05).

The interaction indicated that patients who relapsed exhibited greater meaningfulness reactivity to NSE during treatment, in that they had a stronger negative within-day association between NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness compared to patients who remained abstinent. As shown in Figure 2, the relation between NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness was −0.41 among patients who remained abstinent, which was not significantly different from zero. Among patients who relapsed, the relation between NSE and end-of-day meaningfulness was −2.30, which was significantly different from zero.

Figure 2.

This figure demonstrates that individuals who relapsed following discharge from residential treatment exhibited greater reactivity to negative social experiences during treatment, in that they had a stronger negative within-day association between number of daily negative social experiences and end-of-day meaningfulness compared to individuals who remained abstinent post-treatment.

Given that both positive and negative social experiences were related to end-of-day meaningfulness, pseudo-R2 was calculated from a model without PSE and subtracted from the pseudo-R2 from the full model with PSE to examine the variance uniquely attributable to PSE. The same process was followed for NSE, subtracting pseudo-R2 from a model without NSE (main or interaction effects) from the full model’s pseudo-R2 (main and interaction effects included). The full model explained 17.4% of variance in end-of-day meaningfulness. The fixed effect of PSE accounted for 4.1% of variance, and the fixed effect of NSE accounted for 2.4%.

Of note, there were n=49 participants in our sample for whom we could determine with a reasonable degree of certainty whether or not they specifically returned to opioid misuse following residential treatment (and of these, n=48 had data on end-of-day meaningfulness). However, factors that contribute to return to opioid misuse are likely to create vulnerability to other substances as well. The patients’ treatment was not specific to opioid dependency, although study entry required opioid use disorder as a primary treatment diagnosis. The treatment goal at the clinic was abstinence from all drugs of abuse, as by definition they were problematic in the patients’ lives. Still, we compared the pattern of results when relapse was operationalized as the return to problematic use of any substance (n=69) vs. the return to opioid misuse specifically (n=48). After reducing the number of random effects estimated due to the reduced sample size, we found that the pattern of the results was the same, such that individuals who relapsed (to any substance or to opioids specifically) had stronger negative within-person associations between NSE frequency and end-of-day meaningfulness during residential treatment than individuals who did not relapse.

4. Discussion

This study examined (1) within-person variability in end-of-day meaningfulness among patients in residential treatment for prescription OUD, (2) daily associations among positive and negative social experiences and end-of-day meaningfulness, and (3) whether daily associations were linked to person-level differences in relapse in the first four months after residential treatment. Within-person variability accounted for 48% of variance in end-of-day meaningfulness. Patients’ end-of-day meaningfulness was higher on days when they experienced more positive social experiences, and lower on days when they experienced more negative social experiences. However, patients differed in the way their end-of-day meaningfulness was linked to same-day positive social experiences (“positive meaningfulness reactivity”) or to negative social experiences (“negative meaningfulness reactivity”). Patients who later relapsed exhibited greater negative meaningfulness reactivity during residential treatment than patients who remained abstinent.

The finding that a greater number of positive social experiences predicted higher end-of-day meaningfulness coincides with previous research in college students (Machell et al., 2015) but is the first study we are aware of to examine this relationship among adults in residential OUD treatment. Many individuals experience difficulty maintaining supportive relationships during active addiction (Best et al., 2007; Shinebourne & Smith, 2009). By providing needed emotional connection, positive social experiences may be especially important for enriching meaningfulness in daily life, at least for some individuals.

We found no differences in the association between positive social experiences and end-of-day meaningfulness among patients who relapsed relative to patients who remained abstinent. Rather, patients who relapsed exhibited greater end-of-day meaningfulness reactivity to negative social experiences during residential treatment than patients who remained abstinent. These findings suggest that these daily dynamics are an important element of OUD recovery. In contrast to prior research, which has found an association between meaningfulness and relapse (Martin et al., 2011; Robinson et al., 2007, 2011), we did not find evidence of a direct relationship between meaningfulness and relapse in the current study. Although surprising, it is important to note that our measure was modified to capture meaningfulness as experienced in daily life, rather than meaningfulness in life more broadly as assessed in prior research. Thus, caution should be taken when making direct comparisons to the preexisting literature, and the relationship between meaningfulness and substance use behaviors on a moment-by-moment basis should be the subject of future research. Nonetheless, our results do suggest that when patients in OUD treatment are confronted by negative social experiences, person-level differences in maintaining meaningfulness may be part of the mechanism by which momentary social experiences lead to relapse risk in the early months following residential treatment.

This information could help in the clinical effort to personalize recovery support in addiction treatment. Identifying individuals whose daily meaningfulness appears to react more strongly to negative social experiences would allow clinicians to focus on helping them develop coping strategies to de-couple daily negative social experiences from their sense of meaningfulness. Furthermore, it may also be useful to assess these individuals’ perceived social and environmental stressors prior to returning home, to determine if they require continued residential treatment or referral to a sober living facility.

4.1. Limitations

The fact that patients were in residential treatment likely restricted the range of positive and negative social experiences. Although the residential facility may have reduced the noise that would have been inherent if individuals were in their natural environments, findings should be understood to be restricted to the distributions of these experiences as observed. Future research should examine social experiences (and their relationship to meaningfulness) in other contexts where the types of social experiences and the people with whom individuals interact are likely very different from those in a residential treatment facility. Additionally, in contrast to negative experiences, positive social experiences were assessed with a scale that is not well-established in the literature. Direct comparisons between positive and negative social experiences should be viewed as speculative. Further, we chose to operationalize relapse broadly as the return to problematic use of any substance. Although our data suggest that these results were consistent whether the individuals relapsed to opioids, or to substances other than opioids, larger samples are needed to more fully examine whether the results remain similar when the operationalization of relapse is restricted to a specific substance.

We also focused only on the frequency of social experiences without regard for the individuals with whom these social experiences occurred or the degree of positivity or negativity experienced—factors that might be related to meaningfulness. Our model also constrains the effects of social experiences to a single day. More research is needed to fully understand how long the impacts last before fading, and what characteristics influence that rate of decay.

5. Conclusions

This study considers factors related to both wellness and substance use as important components of addiction treatment. Findings suggest it is not always the levels of a variable, but linkages between variables (i.e., the processes) that are important for understanding treatment outcomes. Clinicians might improve outcomes by helping patients develop coping strategies around de-coupling negative social experiences from meaningfulness.

Highlights.

Nearly half of end-of-day meaningfulness variability was within-person

End-of-day meaningfulness was higher on days with more positive social experiences

Patients who relapsed had greater meaningfulness reactivity to negative experiences

Individual differences in negative meaningfulness reactivity may indicate risk

Strategies to de-couple negative social experiences and meaningfulness are needed

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Caron Treatment Centers for hosting the research study.

Role of Funding Sources

This study was supported by grant R01 DA035240 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Multi-PIs: R.E. Meyer & S.C. Bunce). Author Knapp was supported by the Prevention and Methodology Training Program (T32 DA017629; MPIs: J. Maggs & S. Lanza) with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Agreement

The study was conducted under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board for research with human subjects. Initial findings from this work were presented at the Society for Ambulatory Assessment Conference in June 2019. The manuscript is not being reviewed elsewhere, and the results have not been previously published. The manuscript will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder. All authors approved the final manuscript and made meaningful contributions to its production.

References

- Bassuk EL, Hanson J, Greene RN, Richard M, & Laudet A (2016). Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 63, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Gow J, Knox T, Taylor A, Groshkova T, & White W (2012). Mapping the recovery stories of drinkers and drug users in Glasgow: Quality of life and its associations with measures of recovery capital. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31(3), 334–341. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Manning V, & Strang J (2007). Retrospective recall of heroin initiation and the impact on peer networks. Addiction Research & Theory, 15, 397–410. doi: 10.1080/16066350701340651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Klein KJ & Kozlowski SW (Eds.), Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations (pp. 349–381). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Laurenceau JP (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, & Marlatt GA (2010). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for addictive behaviors: A clinician’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, & Harris KS (2010). The role of coping in moderating within-day associations between negative triggers and substance use cravings: A daily diary investigation. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 60–63. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Harris KS, & Wiebe RP (2010). Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M, … Litten RZ (2010). Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: Evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(12), 2022–2034. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB (2005). Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV–TR axis I disorders (patient edition). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Huhn AS, Harris J, Cleveland HH, Lydon DM, Stankoski D, Cleveland MJ, … Bunce SC (2016). Ecological momentary assessment of affect and craving in patients in treatment for prescription opioid dependence. Brain Research Bulletin. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Guerrero M, Lynch G, Stevens E, Salomon-Amend M, & Light JM (2020). Recovery home networks as social capital. Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 645–657. 10.1002/jcop.22277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, & Hoeppner B (2015). A biaxial formulation of the recovery construct. Addiction Research and Theory, 23(1), 5–9. 10.3109/16066359.2014.930132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Humphreys K, & Ferri M (2020). Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 3, CD012880. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Hicks JA, Krull JL, & Del Gaiso AK (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179–196. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, Ferro T, & Riso LP (1994). Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of axis I and II disorders in a family study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(7), 1043–1047. 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A (2011). The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 6, 44–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Kuppens P, & Bringmann L (2019). On the use of empirical bayes estimates as measures of individual traits. Assessment, 1–13. 10.1177/1073191119885019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zywiak WH, & O’Malley SS (2010). Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: The COMBINE study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(6), 837–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon-Staley DM, Cleveland HH, Huhn AS, Cleveland MJ, Harris J, Stankoski D, … Bunce SC (2017). Daily sleep quality affects drug craving, partially through indirect associations with positive affect, in patients in treatment for nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 275–282. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machell KA, Kashdan TB, Short JL, & Nezlek JB (2015). Relationships between meaning in life, social and achievement events, and positive and negative affect in daily life. Journal of Personality, 83(3), 287–298. 10.1111/jopy.12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh A, Smith L, & Piek J (2003). The Purpose in Life Scale: Psychometric properties for social drinkers and drinkers in alcohol treatment. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 859–871. 10.1177/0013164402251040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RA, MacKinnon S, Johnson J, & Rohsenow DJ (2011). Purpose in life predicts treatment outcome among adult cocaine abusers in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 40(2), 183–188. 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Westerberg VS, Harris RJ, & Tonigan JS (1996). What predicts relapse? Prospective testing of antecedent models. Addiction, 91, 155–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, & Core Team R (2015). nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Package version3., 1–120. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Kowalczyk WJ, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Vahabzadeh M, Lin J-L, … Epstein DH (2018). Exacerbated craving in the presence of stress and drug cues in drug-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43, 859–867. 10.1038/npp.2017.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Cranford JA, Webb JR, & Brower KJ (2007). Six-month changes in spirituality, religiousness, and heavy drinking in a treatment-seeking sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(2), 282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, & Brower KJ (2011). Six- month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(4), 660–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Kirouac M, Pearson MR, Fink BC, & Witkiewitz K (2015). Examining temptation to drink from an existential perspective: Associations among temptation, purpose in life, and drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 716–724. 10.1037/adb0000063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehlman LS, & Karoly P (1991). With a little flak from my friends: Development and preliminary validation of the test of negative social exchange (TENSE). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shinebourne P, & Smith JA (2009). Alcohol and the self: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of addiction and its impact on the sense of self and identity. Addiction Research and Theory, 17, 152–167. doi: 10.1080/16066350802245650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Connors GJ, & Agrawal S (2003). Assessing drinking outcomes in alcohol treatment efficacy studies: Selecting a yardstick of success. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 27(10), 1661–1666. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000091227.26627.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF (2009). Meaning in life. In Lopez SJ (Ed.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 679–687). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Kashdan TB, & Oishi S (2008). Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Results from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health: Summary ofnational findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, & Connors GJ (2001). The search for meaning in life as a predictor of alcoholism treatment outcome. In Longabaugh R, & Wirtz PW (Eds.) Project MATCH Hypotheses: Results and casual Chain Analyses. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 8, NIH Publication No. 01–4238 (pp. 154–165). Washington: Government Printing Office [Google Scholar]

- Waisberg JL, & Porter JE (1994). Purpose in life and outcome of treatment for alcohol dependence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(1), 49–63. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner CC, & Sanchez FP (2002). The role of values in motivational interviewing. In Miller WR, & Rollnick S (Eds.) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed., pp. 284–298). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg VS, Tonigan JS, & Miller WR (1998). Reliability of Form 90D: An instrument for quantifying drug use. Substance Abuse, 19, 179–189. 10.1080/08897079809511386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]