Abstract

This study aimed to quantify the relationship between postpartum depression and anxiety, oxytocin, and breastfeeding. We conducted a longitudinal prospective study of mother-infant dyads from the third trimester of pregnancy to 12 months postpartum. A sample of 222 women were recruited to complete the Beck Depression Inventory II and Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state subscale, participate in observed infant feeding sessions at 2 and 6 months postpartum, and provide venous blood samples during feeding. Maternal venous oxytocin levels in EDTA-treated plasma and saliva were determined by enzyme immunoassay with extraction and a composite measure of area under the curve (AUC) was used to define oxytocin across a breastfeeding session. Linear regression was used to estimate associations between postpartum depression and anxiety as predictors and oxytocin AUC during breastfeeding as the outcome at both 2 and 6 months postpartum. Mixed models accounting for correlations between repeated oxytocin measures were used to quantify the association between current depression and/or anxiety symptoms and oxytocin profiles during breastfeeding. We found no significant differences in oxytocin AUC across a feed between depressed or anxious women and asymptomatic women at either 2 or 6 months postpartum. Repeated measures analyses demonstrated no differences in oxytocin trajectories during breastfeeding by symptom group but possible differences by antidepressant use. Our study suggests that external factors may influence the relationship between oxytocin, maternal mood symptoms, and infant feeding.

Keywords: oxytocin, depression, breastfeeding, lactation, anxiety

1. Introduction

Postpartum mood and anxiety disorders are common in the United States, with postpartum depression affecting approximately 1 in 9 women (Ko, Rockhill et al. 2017). Postpartum depression commonly presents with depressive symptoms up to 1 year after childbirth, often with comorbid anxiety symptoms, and can have adverse effects on the mother-infant dyad (Mah 2016, Meltzer-Brody, Howard et al. 2018). There is an established relationship between postpartum mood and anxiety disorders and impaired child development, including sleep problems, temperamental difficulties, and impaired maternal-infant bonding (Netsi, Pearson et al. 2018). In addition, 1 out of 5 women with postpartum depression experience failed lactation, defined as unplanned and undesired weaning due to physiologic problems (Stuebe, Grewen et al. 2012).

Lower levels of oxytocin, a neuropeptide involved in social behavior, have been shown to be associated with higher levels of depression in both non-pregnant adults (Gordon, Zagoory-Sharon et al. 2008) and postpartum women (Skrundz, Bolten et al. 2011). Oxytocin is critical for the milk ejection reflex to occur (Ely and Petersen 1941, Gunther 1942, Nickerson, Bonsnes et al. 1954). The relationship between oxytocin, maternal mood symptoms, and breastfeeding is not well understood. Prior work has shown a relationship between maternal depression and anxiety symptoms and low oxytocin levels during breastfeeding (Stuebe, Grewen et al. 2013). Polymorphisms in the oxytocin peptide gene have been shown to interact with early life adversity to predict differences in postpartum depression and breastfeeding duration (Jonas, Mileva-Seitz et al. 2013). In addition, endogenous oxytocin released during breastfeeding has been proposed to reduce anxiety and attenuate stress response in breastfeeding women (Heinrichs, Baumgartner et al. 2003). Conversely, acute stress also inhibits oxytocin release and milk transfer (Newton and Newton 1948, Ueda, Yokoyama et al. 1994), thus, relationships between oxytocin and mood symptoms may be bidirectional. Oxytocin acting in the brain and released into the circulatory system in response to suckling during breastfeeding may play a physiologic role in multiple systems that affect HPA reactivity, physical responses to breastfeeding, and maternal-infant attachment and bonding. Similarly, maternal mood symptoms may also affect these systems by reducing oxytocin release. Despite preliminary evidence for the role of oxytocin in depressive symptoms, studies of exogenous intranasal administration of oxytocin have had mixed findings on mood and affect (Heinrichs, Baumgartner et al. 2003, Ditzen, Schaer et al. 2009). In one study of oxytocin administration in women with postpartum depression, intranasal oxytocin actually worsened self-reported mood symptoms despite improving mothers’ positive speech about their infants (Mah, Van Ijzendoorn et al. 2013). In more recent work, nasal oxytocin has been shown to increase the harshness of maternal response to crying (Mah, Van Ijzendoorn et al. 2017). Peripartum exposure to synthetic oxytocin has also been associated with a higher risk of depression or anxiety or an antidepressant or anxiolytic prescription within the first year postpartum (Kroll-Desrosiers, Nephew et al. 2017).

To our knowledge, no robust longitudinal studies have quantified the role of oxytocin during breastfeeding in women experiencing postpartum depression or anxiety. The objective of our study was to measure the extent to which postpartum depression is associated with differences in maternal neuroendocrine physiology. We hypothesized that postpartum depression is associated with reduced oxytocin levels during breastfeeding. This study is a prospective cohort study of mother-infant dyads from the third trimester of pregnancy to 12 months postpartum.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

We enrolled 222 pregnant women living near Chapel Hill, North Carolina in a longitudinal cohort study Mood, Mother and Infant: The Psychobiology of Impaired Dyadic Development (MMI). Complete study details have been published elsewhere (Stuebe, Meltzer-Brody et al. 2019). Mother-infant dyads were followed from the third trimester of pregnancy until 12 months postpartum, with baseline data collected through questionnaires and interviews with study staff at the third trimester laboratory visit. Follow-up contacts occurred through monthly phone interviews and laboratory visits at 2, 6, and 12 months postpartum. Women were recruited from prenatal and psychiatric clinics affiliated with the University of North Carolina Hospital, and through email and social media between May 2013 and April 2017. Women with an elevated risk for postpartum depression and anxiety were oversampled, with risk ascertained through a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) at enrollment. By design, 87 women had a SCID-confirmed diagnosis of current depression or anxiety, 64 women had a depression or anxiety history, and 71 women had no psychiatric history. All study procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board and all participants gave informed consent.

2.2. Sample

Eligible study participants were 18-45 years old, enrolled at >34 weeks’ gestation of a singleton pregnancy, able to communicate in English, intending to remain within 40 miles of UNC through infant’s first birthday, and intending to breastfeed more than 2 months. Women were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: maternal diagnosis of Axis I disorders other than unipolar depression or anxiety disorders; current substance use; major congenital anomaly, neonatal intensive care unit admission>12 hours, or perinatal death; contraindication for breastfeeding; and current use of tricyclic antidepressants. For this analysis, we excluded 13 study participants who dropped out before completing the 2-month laboratory visit, at which time maternal oxytocin levels were measured during an infant feeding session.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Exposures

Postpartum depression symptoms were defined via the Beck Depression Inventory II at 2 and 6 months. The BDI-II is a 21-item scale constructed to measure the severity of self-reported depression based upon the DSM-IV criteria, with good validity and reliability in postpartum women (Pinheiro, da Silva et al. 2008, Ji, Long et al. 2011) and good internal consistencies in our data (Cronbach’s Alpha=0.87 at 2 months and 0.91 at 6 months). We used a cutoff score of ≥ 14 to indicate probable postpartum depression at each time point, as this cutoff has been shown to have a 92% sensitivity and 83% specificity for major depression based on a Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview in a postpartum outpatient sample (Wang and Gorenstein 2013).

Postpartum anxiety symptoms were quantified using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state subscale (STAI-S) at 2 and 6 months. The STAI-S asks women to rate experiences of 20 feelings “at this moment” using a Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much so.” This subscale has been validated in perinatal populations (Meades and Ayers 2011) despite somewhat lower internal consistencies in our data (Cronbach’s alpha=0.55 at 2 months and 0.52 at 6 months). We used a cutoff of >40 to indicate probable postpartum anxiety at each time point, as this cutoff at 1 week postpartum had a 67.5% sensitivity and 87.1% specificity in identifying mothers with anxiety at 8 weeks postpartum (Dennis, Coghlan et al. 2013).

2.3.2. Outcome

At laboratory visits at 2 and 6 months postpartum, mother-infant dyads participated in an observed feeding session. At each visit, some mothers had stopped lactating, and some were bottle-feeding expressed breast milk. Mothers were instructed to feed their infant as they typically would at home. Because our primary aim was to explore the role of postpartum depression and anxiety in oxytocin during breastfeeding, we restricted our main analytic sample to mothers who breastfed during the observed feeding session at 2 months (N=145) and 6 months (N=127). After a 10-minute habituation period and 10 minutes of rest before the feeding session began, a baseline venous blood sample from the mother was obtained. In the 10 minutes before the feeding session began, research assistants cared for the infant in a separate room in the laboratory from where the mother rested to ensure that the mother experienced 10 minutes of uninterrupted rest before the baseline venous blood sample was obtained. Additional blood samples were obtained at minutes 1, 4, 7, and 10 of the feeding session. Each blood sample was collected into pre-chilled vacutainer tubes, immediately cold-centrifuged, aliquoted into pre-chilled cryotubes, and stored at −80° Centigrade (C). Oxytocin in EDTA-treated plasma and saliva, with aprotinin added to prevent peptide degradation, was determined by enzyme immunoassay with extraction (Enzo Life Sciences, NY) as previously described (Grewen, Davenport et al. 2010). Oxytocin across a feeding session was defined using a composite measure of area under the curve (AUC) with respect to ground (Pruessner, Kirschbaum et al. 2003) to capture the variation in oxytocin levels due to pulsatile release(Pruessner, Kirschbaum et al. 2003).

2.3.3. Covariates

We explored potential confounding by the following covariates. Trauma history was evaluated at 12 months postpartum using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein, Stein et al. 2003). We used the total score from the validated 28-item instrument that uses self-report to identify previous physical, emotional, and sexual abuse as well as emotional and physical neglect. Pregnancy intendedness was quantified during the prenatal visit using a 6-item measure of “circumstances of pregnancy” that has been shown to have high reliability and validity (Barrett, Smith et al. 2004, Morof, Steinauer et al. 2012). A higher score on the circumstances of pregnancy questionnaire indicates a more intended pregnancy. Parity was defined as a dichotomous variable to distinguish nulliparous and parous participants at baseline. Days postpartum at the time of the observed feeding session was calculated as the age in days from the infant’s birth until the day of the laboratory visit. Adult relationship style was assessed during the prenatal visit using the Experience in Close Relationship Scale-Short Form (ECR-S) (Wei, Russell et al. 2007), which uses 12 items to assess attachment styles in romantic relationships with respect to 6 anxiety and 6 avoidance dimensions.

Maternal medication use was reported monthly via questionnaire. We defined maternal antidepressant use at 2 and 6 months where mothers reported taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or other antidepressant. Antidepressant use was considered both as a potential modifier and confounder.

2.4. Data Analysis

Linear regression was used to estimate crude and multivariable associations between postpartum depression and anxiety at 2 months and oxytocin AUC during breastfeeding at the 2-month observed feeding session. We used mixed models that account for correlations between repeated oxytocin measures within each mother to quantify the association between current depression and/or anxiety symptoms and profiles of oxytocin across a breastfeed at 2 and 6 months, and we plotted mean oxytocin levels across each breastfeeding session along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for confounders. Confounders were included where they were identified based on subject-matter knowledge and identified as important to adjust for based on a directed acyclic graph. We used an interaction term to test whether current antidepressant use at the time of the feeding session modified the association between maternal mood symptoms and oxytocin profiles. Effect measure modification was considered to be present where p values for interaction terms were <0.05.

While the main analyses were restricted to women who had values for all five oxytocin measures used to calculate oxytocin AUC across a breastfeed, we conducted sensitivity analyses among the entire sample of breastfeeding mothers who contributed at least one oxytocin value across a breastfeed. We also plotted mean oxytocin profiles across a breastfeed at 2 months using exposure thresholds from our pilot analyses using a different sample of mothers with a sample size of 47 women who completed study visits in the third trimester of pregnancy and at 2 and 8 weeks postpartum. In these pilot analyses, mood symptoms were defined via Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state subscale score of at least 34 or Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score of at least 10 at these study visits (Stuebe, Grewen et al. 2013). We also conducted sensitivity analyses controlling for return of the mother’s menses and hormonal contraceptive use, given the potential association between reproductive hormones and mood symptoms. Every month, mothers were asked if their menses had returned since delivery or if they had started a hormonal contraceptive. For sensitivity analyses, we created indicator variables for resumption of menses or hormonal contraceptive use by the time of the 2 month and 6 month laboratory visits.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

Of the 209 mothers who participated in the two-month laboratory visit, 181 had oxytocin levels measured at all pre-specified time points across the observed feeding session. Of these 181, 145 breastfed during the feeding session at two months and 111 breastfed during the session at 6 months. There were no significant differences between mothers who were not breastfeeding at the 2-month visit and breastfeeding mothers in depression (16% v. 25%, p=0.22) or anxiety symptoms (8% v. 11%, p=0.53), antidepressant use (21% v. 31%, p=0.27), history of moderate/severe childhood trauma (26% v. 37%, p=0.21), or single/divorced status (17% v. 33%, p=0.03) (data not shown). Mothers who breastfed during the 2-month visit also had consistently higher mean oxytocin levels across the feeding session compared with bottle-feeding mothers (Supplemental Figure 1).

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics for the 145 mothers who breastfed at the 2-month observed feeding session overall and by current postpartum depression or anxiety symptoms. Mothers who had active prenatal depression or anxiety had the highest likelihood of experiencing symptoms at 2 months, followed by mothers with a history of depression or anxiety. Overall, mothers in the sample were predominantly non-Hispanic white, almost 52 percent had a postgraduate level of education, 83 percent were married or partnered, and 58 percent were nulliparous at baseline. Mothers with depression or anxiety symptoms were slightly more likely to be a racial/ethnic minority, single/divorced, and multiparous.

Table 1:

Descriptive characteristics overall and by postpartum depression or anxiety symptoms among mothers who breastfed during an observed feeding session at 2 months postpartum (N=145)

| Overall | Postpartum Depression Symptomsa |

Postpartum Anxiety Symptomsb |

P for difference between groups with depression and/or anxiety symptoms and without |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Number of study subjects | 145 | (100) | 122 | (84.1) | 23 | (15.9) | 133 | (91.7) | 12 | (8.3) | |

| Baseline risk for postpartum depression/anxietyc | 53 | (36.6) | 40 | (75.5) | 13 | (24.5) | 45 | (84.9) | 8 | (7.1) | |

| High risk, active prenatal depression/anxiety | |||||||||||

| High risk, history of depression/anxiety | 44 | (30.3) | 36 | (81.8) | 8 | (18.2) | 41 | (93.2) | 3 | (6.8) | |

| Low risk, no history of depression/anxiety | 48 | (33.1) | 46 | (95.8) | 2 | (4.2) | 47 | (97.9) | 1 | (2.1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 112 | (77.2) | 98 | (87.5) | 14 | (12.5) | 104 | (92.9) | 8 | (7.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | |||||||||||

| Hispanic, any race | 17 | (11.7) | 12 | (70.6) | 5 | (29.4) | 14 | (82.4) | 3 | (17.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11 | (7.6) | 9 | (81.8) | 2 | (18.2) | 10 | (90.9) | 1 | (9.1) | |

| Otherd | 5 | (3.4) | 3 | (60.0) | 2 | (40.0) | 5 | (100.0) | 0 | 0 | |

| Education Level | 75 | (51.7) | 64 | (85.3) | 11 | (14.7) | 70 | (93.3) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Postgraduate level | |||||||||||

| Some college or college grad | 62 | (42.8) | 51 | (82.3) | 11 | (17.7) | 56 | (90.3) | 6 | (9.7) | |

| Some high school or high school grad | 8 | (5.5) | 7 | (87.5) | 1 | (12.5) | 7 | (87.5) | 1 | (12.5) | |

| Marital status | 121 | (83.4) | 105 | (86.8) | 16 | (13.2) | 112 | (92.6) | 9 | (7.4) | |

| Married/partnered | |||||||||||

| Single/divorced | 24 | (16.6) | 17 | (70.8) | 7 | (29.2) | 21 | (87.5) | 3 | (12.5) | |

| Parity | 84 | (57.9) | 69 | (82.1) | 15 | (17.9) | 77 | (91.7) | 7 | (8.3) | |

| Primiparous | |||||||||||

| Multiparous | 61 | (42.1) | 53 | (86.9) | 8 | (13.1) | 56 | (91.8) | 5 | (8.2) | |

| Antidepressant use at two monthse | 113 | (77.9) | 98 | (86.7) | 15 | (13.3) | 104 | (92.0) | 9 | (8.0) | |

| No | |||||||||||

| Yes | 30 | (20.7) | 24 | (80.0) | 6 | (20.0) | 28 | (93.3) | 2 | (6.7) | |

| Moderate/Severe childhood traumaf | 107 | (73.8) | 94 | (87.9) | 13 | (12.1) | 102 | (95.3) | 5 | (4.7) | |

| No | |||||||||||

| Yes | 37 | (25.5) | 27 | (73.0) | 10 | (27.0) | 30 | (81.1) | 7 | (18.9) | |

| Oxytocin exposure during labor | 83 | (57.2) | 72 | (86.7) | 11 | (13.3) | 78 | (94.0) | 5 | (6.0) | |

| No | |||||||||||

| Yes | 62 | (42.8) | 50 | (80.6) | 12 | (19.4) | 55 | (88.7) | 7 | (11.3) | |

| Mean | (SD) | ||||||||||

| Anxious attachment style, mean (SD)g | 18.3 | (6.8) | 17.1 | 6.1 | 24.3 | 7.2 | 17.5 | 6.3 | 26.3 | 6.7 | |

| Avoidant attachment style, mean (SD)h | 10.9 | (5.8) | 10.1 | 5.2 | 15.1 | 7.0 | 10.7 | 5.9 | 13.0 | 5.3 | |

| Modified perinatal trauma score, mean (SD)i | 6.4 | (6.7) | 4.8 | 5.0 | 15.0 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 13.6 | 8.9 | |

| Pregnancy intendedness, mean (SD)j | 10.4 | (2.6) | 10.5 | 2.5 | 9.8 | 3.0 | 10.5 | 2.5 | 9.3 | 3.5 | |

Postpartum depression symptoms at 2 months were defined using a cutoff of ≥ 14 on the Beck Depression Inventory II.

Postpartum anxiety symptoms at 2 months were defined using a cutoff of >40 on the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Baseline risk for postpartum depression or anxiety was defined at the baseline visit in the third trimester of pregnancy using a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV criteria for depressive and anxiety disorders

Other race/ethnicity includes Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

We defined maternal antidepressant use at 2 months where mothers reported taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, heterocyclic, or other antidepressant; 2 missing values.

Defined as meeting the threshold for moderate/severe emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, or physical neglect on the 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; 1 missing value

Defined at baseline using the Experience in Close Relationship Scale-Short Form, which uses 12 items to assess attachment styles in romantic relationships with respect to 6 anxiety and 6 avoidance dimensions.

Modified Perinatal Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire scores ranges from 0-56, with higher scores indicating more perinatal PTSD

Defined at baseline using the 6-item measure of “circumstances of pregnancy,” where a higher score indicates a more intended pregnancy

Almost 21 percent of the sample was taking an antidepressant at 2 months, with more depressed mothers and fewer anxious mothers using antidepressants. Almost 26 percent of the sample had experienced moderate to severe childhood trauma, with a higher frequency of depressive symptoms (27% versus 12.1%) and anxiety symptoms (18.9% 4.7%) in this group compared to participants without a history of moderate to severe childhood trauma. Depressed and anxious mothers had higher levels of anxious and avoidant attachment styles compared with non-depressed or anxious mothers. Both depressed and anxious mothers had higher perinatal trauma scores and lower pregnancy intendedness scores compared with non-depressed or anxious mothers.

3.2. Postpartum Mood and Oxytocin During Breastfeeding at Two Months

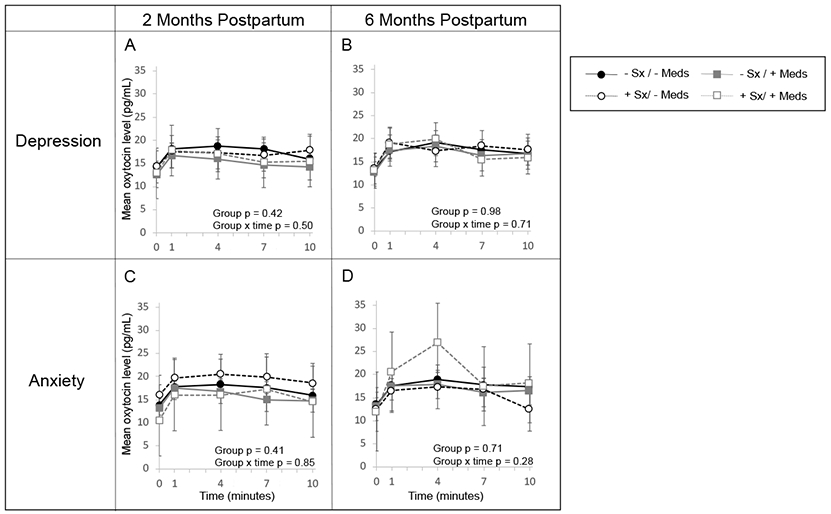

After adjustment for days postpartum, childhood trauma, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and current antidepressant use, mothers with postpartum depression symptoms had oxytocin AUC levels that were 2.26 (95% CI: −30.60, 26.08) pg/mL lower across a breastfeed compared to mothers without postpartum depression symptoms (Table 2). After adjustment for days postpartum, anxious attachment style, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and current antidepressant use, mothers with postpartum anxiety symptoms had oxytocin AUC levels that were 21.27 (95% CI: −15.54, 56.60) pg/mL higher across a breastfeed compared to mothers without postpartum anxiety (Table 2). In repeated measures analyses, mothers with postpartum depression or anxiety symptoms at 2 months did not have significant differences in oxytocin profiles across a breastfeed compared to mothers without symptoms; however, mothers with depression symptoms had lower oxytocin levels across a breastfeed (Figure 1A) and mothers with anxiety symptoms had higher levels (Figure 1C). Results were not different in sensitivity analyses including all mothers contributing any oxytocin values across a breastfeed or in sensitivity analyses controlling for resumption of menses or hormonal contraception. Mean oxytocin (OT) levels were not significantly different across a breastfeed by higher versus lower mood symptoms using pilot study thresholds and similarly adjusted for days postpartum and parity (Supplemental Figure S4).

Table 2:

Estimates of association between perinatal mood, antidepressant use, and oxytocin during an observed feeding session at 2 and 6 months

| Two-month oxytocin AUC across a breastfeed | Six-month oxytocin AUC across a breastfeed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Crude | Adjusted | N | Crude | Adjusted | |

| Exposure | Beta (95% CI) | Beta (95% CI) | Beta (95% CI) | Beta (95% CI) | ||

| Postpartum Depression Symptoms v. Nonea | 145 | −0.52 (−27.85, 26.81) | −2.26 (−30.60, 26.08) | 127 | 0.96 (−27.72, 29.64) | 3.00 (−25.56, 31.56) |

| Postpartum Anxiety Symptoms v. Noneb | 145 | 11.69 (−22.06, 45.45) | 21.27 (−14.26, 56.80) | 126 | −17.88 (−54.79, 19.03) | −3.68 (−42.79, 35.43) |

| Antidepressant Use v. Nonec | 143 | −22.04 (−46.53, 2.46) | −23.79 (−48.60, 1.02) | 126 | −2.79 (−31.15, 25.57) | −7.16 (−35.21, 20.90) |

| Symptomatic v. Asymptomaticd | 143 | 8.03 (−16.01, 32.08) | 7.78 (−16.37, 31.93) | −6.05 (−30.94, 18.84) | −6.41 (−31.55, 18.73) | |

Adjusted for confounding by days postpartum, childhood trauma, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use.

Adjusted for confounding by days postpartum, anxious attachment style, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use.

Adjusted for confounding by days postpartum, childhood trauma, prenatal depression symptoms, pregnancy intendedness, and parity.

Symptomatic group defined using thresholds from pilot study (Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale ≥ 10 or Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory ≥ 34) combined into one symptomatic category; adjusted for confounding by days postpartum and parity as in pilot analyses.

Figure 1.

Mean oxytocin (OT) levels and 95% confidence intervals across a breastfeed at by current postpartum depression symptoms at (A) 2 months and (B) 6 months and anxiety symptoms at (C) 2 months and (D) 6 months. Depression symptom models adjusted for days postpartum, childhood trauma, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use. Anxiety symptom models, adjusted by days postpartum, anxious attachment style, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use.

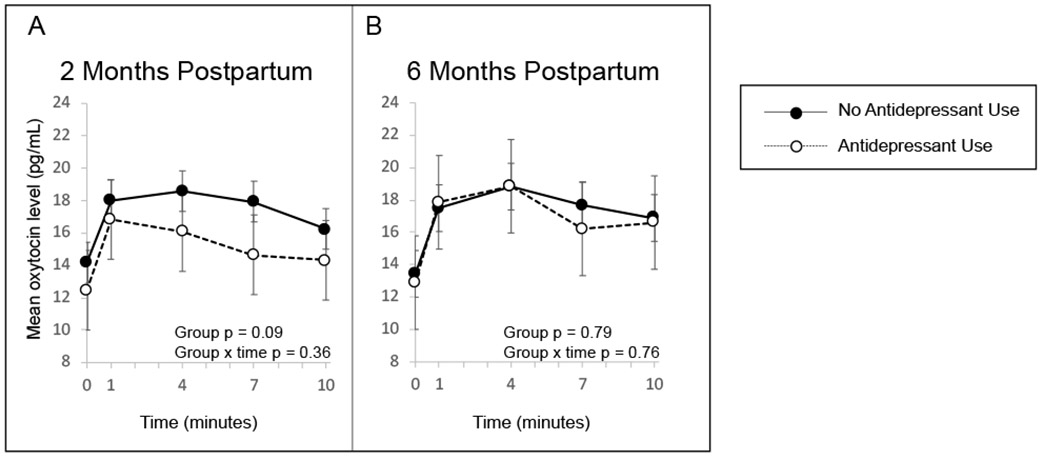

Secondary analyses found no significant interaction between antidepressant use and postpartum depression (p-interaction=0.62) or anxiety symptoms (p-interaction=0.62) on oxytocin AUC or in repeated measures analysis across a feed (Figure 2). However, repeated measures analysis showed a pattern that mothers using antidepressants had lower oxytocin levels across a breastfeed compared to mothers not using antidepressants, adjusting for days postpartum, childhood trauma, prenatal depression symptoms, pregnancy intendedness, and parity (p=0.09) (Figure 3). After adjustment, antidepressant use was associated with 23.79 (95% CI: −48.60, 1.02) pg/mL lower oxytocin AUC across a breastfeed (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean oxytocin (OT) levels and 95% confidence intervals across a breastfeed at (A) 2 months and (B) 6 months by current postpartum depression symptoms and antidepressant use, adjusted for days postpartum, childhood trauma, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use. Mean oxytocin (OT) levels and 95% confidence intervals across a breastfeed at (C) 2 months and (D) 6 months by current anxiety symptoms and antidepressant use, adjusted for days postpartum, anxious attachment style, pregnancy intendedness, parity, and antidepressant use.

Figure 3.

Mean oxytocin (OT) levels and 95% confidence intervals across a breastfeed at (A) 2 months and (B) 6 months by current antidepressant use, adjusted for days postpartum, childhood trauma, prenatal depression symptoms, pregnancy intendedness, and parity.

3.3. Postpartum Mood and Oxytocin During Breastfeeding at Six Months

At 6 months, there remained no significant differences in oxytocin AUC across a breastfeed by current depression or anxiety symptoms (Table 2, Figure 1B and 1D). However, repeated measures analyses showed that oxytocin levels were approximately the same or lower across a breastfeed for mothers with postpartum anxiety at 6 months, in contrast to the consistently higher levels at 2 months (Figure 1C and 1D). As at 2 months, at 6 months we found no significant interaction between antidepressant use and postpartum depression (Figure 2B, p=0.71) or anxiety symptoms (Figure 2D, p=0.28). In contrast to 2 months, oxytocin levels across a breastfeed in women who used antidepressants and women who did not were nearly identical (Figure 3B). Results were not different in any of the sensitivity analyses. As an indicator of how stable the oxytocin, depression, and anxiety measures were in our data, stabilities were determined for oxytocin AUC at 2 and 6 months (ρ = 0.68, p < .0001), BDI depression scores at 2 and 6 months (ρ = 0.66, p < .0001), and Spielberger state anxiety scores at 2 and 6 months (ρ = 0.55, p < .0001).

4. Discussion

In this longitudinal study of women intending to breastfeed, we aimed to use lactation as a physiologic challenge to quantify the extent to which maternal depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with reduced oxytocin during breastfeeding. In all breastfeeding women, we observed the expected oxytocin trajectory, in which oxytocin rose immediately after the beginning of the feed and peaked around four minutes into the feed. We did not observe this pattern in women who bottle fed their infant during the visit. We hypothesized that women with depression and anxiety symptoms would have lower levels of oxytocin during feeding compared to asymptomatic women. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no significant differences in oxytocin levels across a feed between either depressed and non-depressed women or between anxious and non-anxious women at either 2 or 6 months postpartum. In repeated measures analyses across the feed, we observed contradictory trends in oxytocin profiles that did not reach statistical significance. At 2 months postpartum, oxytocin was lower in women with depressive symptoms and higher in women with anxious symptoms compared to asymptomatic women. At 6 months postpartum, the trend was reversed, with oxytocin higher in depressed women and lower in anxious women compared to asymptomatic women.

Despite the potential physiologic importance of breastfeeding in the relationship between oxytocin and maternal mood symptoms, few studies have examined the role of breastfeeding or have been conducted in breastfeeding populations. To our knowledge, ours is the first robust study to use lactation as a physiologic challenge to examine the role of oxytocin in maternal depression and anxiety symptoms. Prior work by this team in a pilot sample examined a similar question, and contrary to our results in this study, the pilot study did find lower oxytocin at 8 weeks postpartum in women with higher depression and anxiety symptoms compared to asymptomatic women (p < 0.05) (Stuebe, Grewen et al. 2013, Cox, Stuebe et al. 2015). The results between the previous pilot study and the present study findings may differ due to a number of reasons. The pilot study used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to measure depression symptoms, while we used the Beck Depression Inventory in this study. The pilot study sample size was quite small, with only 11 women in the ‘higher symptom’ category. Additionally, because of the small sample size, lower depression and anxiety thresholds were used to establish symptomatic groups (EPDS ≥ 10; STAI ≥ 34) and depression and anxiety symptoms were combined into one ‘higher symptom’ category. In a sensitivity analysis in which we used the same categories and thresholds in our data, we found no difference in mean oxytocin levels across a breastfeed, and slightly higher oxytocin levels among those with higher mood symptoms. Our results also differ from those of the only other study examining the relationship between maternal depression symptoms and oxytocin AUC during infant feeding. In that study, Lara-Cinisomo et al. (2017) found lower levels of oxytocin in women with depressive symptoms compared to asymptomatic women only among those who had stopped breastfeeding their infant by 8 weeks postpartum (Lara-Cinisomo, McKenney et al. 2017). It is possible that the relationship between oxytocin and affective symptoms may interact with a number of other variables that were not captured in our study.

Because our primary hypothesis was to use lactation as a physiologic challenge to quantify the extent to which depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with oxytocin, we recruited women who intended to breastfeed and restricted our primary analyses to women who breastfed at the visit. Relatively few women bottle fed their infants during the visit, so we were limited in our ability to determine if other factors interacted with feeding type, but we were able to observe oxytocin patterns in women who breastfed and women who bottle fed during the visit. As expected, we saw significant differences in oxytocin, in which women who breastfed their infants produced a dramatic increase in oxytocin after the start of the feed while oxytocin levels remained approximately static among women who bottle fed at the visit (Supplementary Figure S1). However, among the 36 women who bottle fed at the visit at two months, 6 (17%) were still breastfeeding some of the time. Thus, it is critical to observe oxytocin specifically during breastfeeding to assess differences in oxytocin in postpartum women and particularly as it relates to maternal mood symptoms. As milk ejection depends on peaks of oxytocin, it is possible that changes in oxytocin circadian rhythmicity may be associated with mood symptoms. However, since shared neuroendocrine mechanisms are proposed to contribute to failed lactation and perinatal mood disorders, mothers that breastfeed may not exhibit such neuroendocrine dysregulation. In our cohort, 80 percent of the mothers that participated in the 2-month laboratory visit were still breastfeeding, and all 2-month laboratory visits were conducted in the afternoon.

This is the largest study to assess oxytocin throughout breastfeeding in relation to maternal mood symptoms, but is limited in several ways. Not surprisingly, individual oxytocin patterns throughout feeding were highly variable, even when limited to breastfeeding women (Supplementary Figures S2, S3). It is possible that the rate of oxytocin change throughout feeding may be just as important as oxytocin levels, and assessing average oxytocin levels over time by mood and anxiety status may mask some of the variability in rate of change. Future work might examine latent classes of oxytocin to determine if oxytocin trajectories during feeding are differentially associated with maternal mood symptoms. As prior work by Jonas et al. (2013) has shown an association between genetic variation in the oxytocin peptide gene and maternal breastfeeding and mood symptoms, genotyping of the mothers in our study may further inform our understanding of the relationship between oxytocin and maternal depression symptoms as well as the variability in oxytocin patterns during feeding. Due to our sample size, we also faced challenges with the ability to detect differences with respect to individual factors that might increase or decrease this oxytocin variability such as mixed feeding, pumping, use of galactagogues, and breastfeeding challenges. In other ways, our sample was limited by its homogeneity. Despite recruiting a high-risk sample, in which approximately two-thirds of women had active symptoms or a history of a mood disorder at the time of recruitment, depression and anxiety symptoms overall were relatively mild at the 2-month postpartum visit, which may have limited our ability to detect group differences in oxytocin. Our population was also mostly non-Hispanic white, married or partnered, and most had high levels of education, which may limit generalizability to other populations. In addition, the heterogeneity of oxytocin profiles during breastfeeding represents a potential limitation in identifying average patterns by mood or anxiety status (see Supplemental Figures).

Despite these limitations, our study has a number of additional strengths. To our knowledge, this is the largest longitudinal study of oxytocin throughout feeding assessed at multiple time points after childbirth. Although we saw no significant differences in oxytocin AUC between symptom groups, we did see differences in oxytocin patterns between the 2-month and 6-month visits for several factors, even after controlling for number of days since birth, which may indicate that both timing throughout a feed and timing since childbirth might influence how external factors affect endogenous oxytocin. We recruited women in late pregnancy and followed them prospectively to capture breastfeeding intention prior to birth and reduce confounding by preferences about breastfeeding. We employed well-validated metrics that are frequently used in clinical and research settings to assess maternal affective symptoms and infant feeding characteristics. Additionally, we measured both depression and anxiety symptoms separately; most studies of maternal mental health focus on depressive symptoms or assess depressive and anxiety symptoms jointly. Our highly granular data also enabled us to control for important confounders such as parity, time since birth, trauma history, pregnancy intendedness, relationship style, and antidepressant medication use.

Our study design also enabled us to incorporate treatment into analyses, both as a potential confounder and to assess potential interactions between affective symptoms and treatment. Use of antidepressant medications was one of the more influential factors in differences in oxytocin profiles. Specifically, in repeated measures analyses, oxytocin values tended to be lower throughout the feed in women taking antidepressants than those who were not taking antidepressants at 2 months postpartum, although this finding did not reach statistical significance. We assessed interaction of symptoms and antidepressant use and found no interaction between mood or anxiety symptoms and antidepressant medication use at either the 2- or 6-month visits. Despite our analytic approach, it is still a challenge to disentangle how much current affective symptoms, treatment, or a combination of both most directly affect oxytocin. In our sample, approximately 20 percent of asymptomatic women were using an antidepressant. It is plausible that a person may have experienced affective symptoms and were treated with antidepressants prior to 2 months postpartum but then are asymptomatic by the time of the 2-month visit. Similarly, it is not possible to separate treatment from symptom severity with our study design. Women with more severe depression or anxiety are more likely to be treated with an antidepressant, and women using more medication may be more likely to have more severe and treatment-resistant symptoms.

Overall in our sample, we found no significant differences in oxytocin levels across a feed between women with depressive or anxious symptoms versus asymptomatic women at both 2 and 6 months postpartum. Analyses of repeated oxytocin measures throughout a feeding session demonstrated no differences in oxytocin trajectories during breastfeeding by symptom group. We did not find strong evidence that oxytocin dysregulation was associated with maternal depression or anxiety symptoms. This work highlights that future research must carefully evaluate external factors to understand the complex relationship between oxytocin and maternal depression and anxiety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD073220-01). The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Alison Stuebe and Samantha Meltzer-Brody receive grant support from Janssen Research and Development, and Samantha Meltzer-Brody receives grant support from Sage Therapeutics, Inc, awarded to the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill, NC). These grants are outside the submitted work. The other authors have no competing interests.

References

- Barrett G, Smith SC and Wellings K (2004). "Conceptualisation, development, and evaluation of a measure of unplanned pregnancy." J Epidemiol Community Health 58(5): 426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D and Zule W (2003). "Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire." Child Abuse Negl 27(2): 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EQ, Stuebe A, Pearson B, Grewen K, Rubinow D and Meltzer-Brody S (2015). "Oxytocin and HPA stress axis reactivity in postpartum women." Psychoneuroendocrinology 55: 164–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, Coghlan M and Vigod S (2013). "Can we identify mothers at-risk for postpartum anxiety in the immediate postpartum period using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory?" J Affect Disord 150(3): 1217–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B, Schaer M, Gabriel B, Bodenmann G, Ehlert U and Heinrichs M (2009). "Intranasal oxytocin increases positive communication and reduces cortisol levels during couple conflict." Biol Psychiatry 65(9): 728–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely F and Petersen WE (1941). "Factors Involved in the Ejection of Milk." Journal of Dairy Science 24: 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon I, Zagoory-Sharon O, Schneiderman I, Leckman JF, Weller A and Feldman R (2008). "Oxytocin and cortisol in romantically unattached young adults: associations with bonding and psychological distress." Psychophysiology 45(3): 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewen KM, Davenport RE and Light KC (2010). "An investigation of plasma and salivary oxytocin responses in breast- and formula-feeding mothers of infants." Psychophysiology 47(4): 625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther M (1942). "Lactation in Women." The Canadian Medical Association Journal 47(5): 410–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C and Ehlert U (2003). "Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress." Biol Psychiatry 54(12): 1389–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S, Long Q, Newport DJ, Na H, Knight B, Zach EB, Morris NJ, Kutner M and Stowe ZN (2011). "Validity of depression rating scales during pregnancy and the postpartum period: impact of trimester and parity." J Psychiatr Res 45(2): 213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas W, Mileva-Seitz V, Girard AW, Bisceglia R, Kennedy JL, Sokolowski M, Meaney MJ, Fleming AS, Steiner M and Team MR (2013). "Genetic variation in oxytocin rs2740210 and early adversity associated with postpartum depression and breastfeeding duration." Genes Brain Behav 12(7): 681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, Morrow B and Farr SL (2017). "Trends in Postpartum Depressive Symptoms - 27 States, 2004, 2008, and 2012." MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66(6): 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Nephew BC, Babb JA, Guilarte-Walker Y, Moore Simas TA and Deligiannidis KM (2017). "Association of peripartum synthetic oxytocin administration and depressive and anxiety disorders within the first postpartum year." Depress Anxiety 34(2): 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, McKenney K, Di Florio A and Meltzer-Brody S (2017). "Associations Between Postpartum Depression, Breastfeeding, and Oxytocin Levels in Latina Mothers." Breastfeed Med 12(7): 436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah BL (2016). "Oxytocin, Postnatal Depression, and Parenting: A Systematic Review." Harv Rev Psychiatry 24(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah BL, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Out D, Smith R and Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ (2017). "The Effects of Intranasal Oxytocin Administration on Sensitive Caregiving in Mothers with Postnatal Depression." Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48(2): 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah BL, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Smith R and Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ (2013). "Oxytocin in postnatally depressed mothers: its influence on mood and expressed emotion." Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 40: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meades R and Ayers S (2011). "Anxiety measures validated in perinatal populations: a systematic review." J Affect Disord 133(1-2): 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Howard LM, Bergink V, Vigod S, Jones I, Munk-Olsen T, Honikman S and Milgrom J (2018). "Postpartum psychiatric disorders." Nat Rev Dis Primers 4: 18022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morof D, Steinauer J, Haider S, Liu S, Darney P and Barrett G (2012). "Evaluation of the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy in a United States population of women." PLoS One 7(4): e35381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG and Stein A (2018). "Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child Outcomes." JAMA Psychiatry 75(3): 247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton M and Newton NR (1948). "The let-down reflex in human lactation." The Journal of Pediatrics 33: 698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson K, Bonsnes RW, Douglas RG, Condliffe P and du Vigneaud V (1954). "Oxytocin and milk ejection." American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 67(5): 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro RT, da Silva RA, Magalhães PV, Horta BL and Pinheiro KA (2008). "Two studies on suicidality in the postpartum." Acta Psychiatr Scand 118(2): 160–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G and Hellhammer DH (2003). "Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change." Psychoneuroendocrinology 28(7): 916–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrundz M, Bolten M, Nast I, Hellhammer DH and Meinlschmidt G (2011). "Plasma oxytocin concentration during pregnancy is associated with development of postpartum depression." Neuropsychopharmacology 36(9): 1886–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Grewen K and Meltzer-Brody S (2013). "Association between maternal mood and oxytocin response to breastfeeding." J Womens Health (Larchmt) 22(4): 352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Pedersen CA, Propper C and Meltzer-Brody S (2012). "Failed lactation and perinatal depression: common problems with shared neuroendocrine mechanisms?" J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21(3): 264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Meltzer-Brody S, Propper C, Pearson B, Beiler P, Elam M, Walker C, Mills-Koonce R and Grewen K (2019). "The Mood, Mother, and Infant Study: Associations Between Maternal Mood in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Outcome." Breastfeed Med 14(8): 551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T, Yokoyama Y, Irahara M and Aono T (1994). "Influence of psychological stress on suckling-induced pulsatile oxytocin release." Obstet Gynecol 84(2): 259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YP and Gorenstein C (2013). "Assessment of depression in medical patients: a systematic review of the utility of the Beck Depression Inventory-II." Clinics (Sao Paulo) 68(9): 1274–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B and Vogel DL (2007). "The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: reliability, validity, and factor structure." J Pers Assess 88(2): 187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.