Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Exposure to air pollution, specifically particulate matter of diameter ≤2.5 μm (PM2.5), is a well-established risk factor for CVD. However, the contribution of gaseous pollutant exposure to CVD risk is less clear.

Objective:

To examine the vascular effects of exposure to individual volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and mixtures of VOCs.

Methods:

We measured urinary metabolites of acrolein (CEMA and 3HPMA), 1,3-butadiene (DHBMA and MHBMA3), and crotonaldehyde (HPMMA) in 346 nonsmokers with varying levels of CVD risk. On the day of enrollment, we measured blood pressure (BP), reactive hyperemia index (RHI – a measure of endothelial function), and urinary levels of catecholamines and their metabolites. We used generalized linear models for evaluating the association between individual VOC metabolites and BP, RHI, and catecholamines, and we used Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) to assess exposure to VOC metabolite mixtures and BP.

Results:

We found that the level of 3HPMA was positively associated with systolic BP (0.98 mmHg per interquartile range (IQR) of 3HPMA; CI: 0.06, 1.91; P=0.04). Stratified analysis revealed an increased association with systolic BP in Black participants despite lower levels of urinary 3HPMA. This association was independent of PM2.5 exposure and BP medications. BKMR analysis confirmed that 3HPMA was the major metabolite associated with higher BP in the presence of other metabolites. We found that 3HPMA and DHBMA were associated with decreased endothelial function. For each IQR of 3HPMA or DHBMA, there was a −4.4% (CI: −7.2, −0.0; P=0.03) and a −3.9% (CI: −9.4, −0.0; P=0.04) difference in RHI, respectively. Although in the entire cohort, the levels of several urinary VOC metabolites were weakly associated with urinary catecholamines and their metabolites, in Black participants, DHBMA levels showed strong associations with urinary norepinephrine and normetanephrine levels.

Discussion:

Exposure to acrolein and 1,3-butadiene is associated with endothelial dysfunction and may contribute to elevated risk of hypertension in participants with increased sympathetic tone, particularly in Black individuals.

Keywords: Volatile organic compounds, VOCs, VOC metabolites, cardiovascular disease, CVD, catecholamines, endothelial function, blood pressure, pollution, environmental health, multipollutant, mixture

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death from environmental exposures, surpassing the number of attributable deaths to cancer mortality.1 The World Health Organization estimates that annually, exposure to air pollution is associated with 1.4 million deaths from stroke and 2.4 million deaths from heart disease, worldwide.2 To estimate the health effects of air pollution, most studies examine particulate matter of diameter ≤2.5 μm (PM2.5) and tropospheric ozone (O3).3 However, even though PM2.5 and O3 show strong associations between CVD progression and mortality,4–6 these pollutants represent only two components of complex real-world ambient air pollution, which in most locations around the world is a mixture of different pollutants, including oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Therefore, there is urgent need to assess the health impact of other commonly-found pollutants, and to understand how they affect the risk and progression of cardiovascular and other diseases.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are pervasive environmental pollutants and exposure to VOCs has been found to be associated with health effects such as CVD, neurological effects, organ toxicity, and cancer.7, 8 Although these gaseous compounds are present across all environmental media, they are major components of indoor and outdoor air pollution due to high vapor pressure and low molecular weight.9–11 Primary sources of VOCs include tobacco smoke and vehicle exhaust, industrial releases, consumer goods production, products that contain organic solvents, and hazardous waste sites.12 VOCs also interact with other pollutants to create intermediates and secondary pollutants such as tropospheric O3 and secondary organic aerosols, a major component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5).13, 14 However, compared with the wealth of epidemiological studies of PM2.5, the approximation of human exposure to VOCs is complicated by a lack of routine air monitoring of VOCs,15 large variations of VOCs in space and time,16, 17 and high chemical production each year.18

The classification of multiple chemicals as VOCs further challenges the understanding of VOC exposure. Previous epidemiological studies have grouped ambient VOCs by alkenes, alkynes, and benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and xylene (BTEX) compounds to show associations with cardiovascular events such as heart failure,19 stroke,20 ischemic heart disease,20, 21 and cardiovascular mortality.21, 22 Total VOC exposure is often measured indoors and has been associated with increased blood pressure (BP) and heart rate,23 heart rate variability,24 and autonomic nervous system changes.25 Individual VOC metabolites from human biomonitoring have been associated with doctor-diagnosed CVD26 and metabolic syndrome.27 Likewise, VOC-containing pollutants such as automobile and diesel emissions and tobacco smoke have been variably linked to the development of CVD and CVD risk.28–31 Nonetheless the role of individual VOCs and mixtures of VOCs in CVD pathophysiology in humans remain to be identified.

In addition to environmental monitoring, VOC exposures can also be monitored by measuring urinary metabolites of VOCs. The urinary metabolites of VOCs include specific, stable mercapturic acids with short physiological half-lives quantified by non-invasive sampling.32, 33 Such measurements provide more proximal and individual-level assessments of VOCs. Therefore, in this study, we measured urinary VOC metabolites to assess the relationship between short-term exposure to individual VOCs and VOC mixtures and vascular outcomes. We assessed primary risk factors for CVD, BP and endothelial function, and sympathetic nervous system neurotransmitters/ catecholamines, which are reflective of stress leading to the development of CVD.5 Because personal monitoring and biomonitoring are considered the gold standard of exposure assessment,34 we measured urinary VOC metabolite levels to test the hypothesis that VOC exposure contributes to CVD risk in a nonsmoking, diverse, urban cohort.

METHODS

Both exposure and outcome data were from a cross-sectional study designed to examine the relationship between exposure to environmental pollutants and CVD risk in an urban cohort. The study recruited 615 participants with moderate to high CVD risk (individuals undergoing primary or secondary prevention for CVD) at University of Louisville Hospital and associated clinics in Louisville, KY between October 2009 and April 2017. The primary prevention group refers to those who have known CVD risk factors (e.g. hypertension, hypercholesteremia, obesity, diabetes) that require management but who have no overt CVD. The secondary prevention group refers to those who have CVD risk factors that need to be treated, as well as overt CVD. Participants who met enrollment criteria gave informed consent and were administered a questionnaire to acquire baseline characteristics and demographic information. Inclusion criteria were: 1) age 18 years or older; and 2) treatment for CVD at the University of Louisville Hospital and associated Pre-proofclinics.Personsexcludedwere:1)those unwilling to consent; 2) pregnant or lactating individuals; 3) incarcerated individuals; 4) persons with severe comorbidities (including lung, liver, kidney disease, cancer, and coagulopathies); 5) substance abuse; and, 6) chronic cachexia. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Louisville approved the study.

Measures of Vascular Function

Blood pressure and endothelial function were collected and measured at time of enrollment. Systolic and diastolic BP were measured after ten minutes of rest with an automated cuff and recorded as continuous variables. Three measurements were taken one minute apart with the last two measurements averaged. Peripheral endothelial function was measured in a subset of nonsmoking participants with and without diabetes (n=70) to assess the role of endothelial function in the manifestation of diabetes. Participants with diabetes were classified by HbA1c > 6.5%, fasting plasma glucose > 126mg/dL, or random plasma glucose > 200mg/dL. Peripheral endothelial function was measured using fingertip peripheral arterial tonometry, i.e., EndoPAT, and calculated as a reactive hyperemia index (RHI).35

Urinary Catecholamines and Metabolites

Spot urine samples were collected at day of enrollment. Urinary catecholamines, monoamines, and their metabolites were quantified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) as previously described.36 Briefly, frozen urine samples were thawed on ice, vortexed, and diluted (1:50) with 0.2% formic acid containing isotopically labeled internal standards. The method quantified epinephrine (EPI); norepinephrine (NE); dopamine (DA); serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5HT); metanephrine (MN); normetanephrine (NMN); 3-methoxytyramine (3MT); homovanillic acid (HVA); vanillylmandelic acid (VMA); and, 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (5HIAA) using a Waters Acquity Class-H UPLC coupled with Xevo TQ-S micro mass spectrometer.36 Analytes were normalized to urinary creatinine levels and reported as levels (nanograms of metabolite per milligram of creatinine, ng/mg).

Accuracy was measured by creating four levels of quality control (QC) samples of spiked, known amounts of analytes. Within and between run accuracy was measured in three independent runs with five replicates. Accuracy was calculated as the ratio of measured and expected concentration of analyte. The accuracy of within- and between runs of all analytes were 100 ± 16%. The within- and between run precision values, expressed as coefficient of variation (CV), were<15% for all analytes, with the exception of 5-HT at LOQ level (17.3%). Recovery was within the range of 92–113% at all spike levels (SD ± 16%). Collectively, these results demonstrate excellent precision and accuracy for the determination of all the analytes in urine samples.36

Urinary VOC Metabolites

Volatile organic compounds are ubiquitous environmental pollutants. Although there are several sources of VOCs, the major non-occupational source of exposure is tobacco smoke. However, VOCs can also arise from hazardous waste sites, vehicle exhaust, industrial releases, and household products.12 Urinary VOC metabolites are the preferred method to assess human exposure because of high spatial and temporal variability of VOCs in air,16, 17 urine collection is non-invasive, and mercapturic acids are specific and stable with longer physiological half-lives than parent compounds.32 Given that half-lives of urinary VOC metabolites range from 2.1 to 34 hours,32 urinary VOC metabolites represent an individual’s short-term or acute exposure.37 We measured the most common urinary VOC metabolites, a well developed panel of 22 metabolites of 17 parent VOCs32, 33 in spot urine samples collected on the day of enrollment.

To assess VOC exposure, the levels of 22 urinary metabolites of 17 parent VOCs, (acrolein, acrylamide, acrylonitrile, benzene, 1-bromopropane, 1,3-butadiene, crotonaldehyde, N,N-dimethylformamide, ethylbenzene, ethylene oxide, propylene oxide, styrene, tetrachloroethylene, toluene, trichloroethylene, vinyl chloride, and xylene; Supplemental Table S1) were quantified using a modified version of the UPLC-MSmethod.32,38 Inbrief,urinewas diluted with 15mM ammonium acetate and spiked with isotopically labeled internal standards. The analysis was performed on an Acquity UPLC core system coupled to a Quattro Premier XE triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with an electrospray source (Waters Inc, MA).38

The VOC metabolites were analyzed using a method adopted from CDC.32, 33 The method was validated33 and the results showed that the sensitivity, precision, and accuracy of our method are comparable to the method reported. Specifically, the limit of detection (LOD) of each analyte is typically within 1 to 10 ng/ml. Precision, assessed by the coefficient of variation of quality control samples, was within 17%. Accuracy, assessed by analyzing spiked urine, was determined at three different levels of VOC metabolites, and was within 80 to 120%. The method is highly reproducible, with relative standard deviations <8%. The sensitivity, accuracy, and precision were similar to those associated with the method developed by the CDC.

The primary exposure variables were 22 VOC urinary metabolites: N-Acetyl-S-(2-carboxyethyl)-L-cysteine (CEMA), N-Acetyl-S-(3-hydroxypropyl)-L-cysteine (3HPMA), N-AcetylS-(2-cyanoethyl)-L-cysteine (CYMA), N-Acetyl-S- (2-hydroxyethyl)-L-cysteine (HEMA), t,t-Muconic Acid (MU), N-Acetyl-S-(n-propyl)-L-cysteine (BPMA), N-Acetyl-S-(3,4-dihydroxybutyl)-L-cysteine (DHBMA), N-Acetyl-S-(4-hydroxy-2-buten-1-yl)-L-cysteine (MHBMA3), N-Acetyl-S-(3-hydroxypropyl-1-methyl)-L-cysteine (HPMMA), N-Acetyl-S-(N-methylcarbamoyl)-L-cysteine (AMCC), Phenylglyoxylic acid (PGA), N-Acetyl-S-(2-hydroxypropyl)-L-cysteine (2HPMA), N-Acetyl-S-(1-phenyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-L-cysteine + N-Acetyl-S-(2-phenyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-L-cysteine (PHEMA), Mandelic Acid (MA), N-Acetyl-S-(trichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (TCVMA), N-Acetyl-S-(benzyl)-L-cysteine (BMA), N-Acetyl-S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (12DCVMA), N-Acetyl-S-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (22DCVMA), Urinary N-Acetyl-S-(dimethylphenyl)-L-cysteine (DPMA), 2-Methylhippuric acid (2MHA), and 3-Methylhippuric acid + 4-Methylhippuric acid (3,4MHA). Analytes were normalized to individual urinary creatinine levels to adjust for dilution, and reported as levels (nanograms of metabolite per milligram of creatinine, ng/mg).

Covariates

Data on age, sex, race, body mass index, and self-reported tobacco exposure were collected at baseline using questionnaires. Information on medication use, cardiovascular history, and cardiovascular risk factors was obtained from medical records and questionnaires. We calculated the Framingham risk score (FRS), the risk for coronary heart disease, using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute calculator.39 Because PM2.5 is an established CVD risk factor,4,5 we estimated PM2.5 exposure on the day of enrollment for adjustment in our models. We assessed the spearman correlation between PM2.5 and urinary VOC metabolites and found no significant correlations or correlations of ρ>07. Average daily PM2.5 values for all monitors in the Louisville Metropolitan Statistical Area were collected from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to estimate daily mean values of PM2.5.

Statistical Analysis

Smoking is a known risk factor for CVD, and a major source and possible confounder of VOC exposure.28, 38, 40 To assess environmental VOC exposure in individuals, we restricted the cohort to nonsmokers. We excluded individuals who were smokers, classified as individuals with urinary cotinine levels greater than 40 ng/mg of creatinine (n=222), despite self-reported positive smoking status. This range also excludes those exposed to secondhand smoke.41 Participants without measured VOC metabolite data (n=46) and one participant with catecholamine outliers (six times the 99th percentile of 21,633 ng/mg) were removed from the analysis. The remaining cohort (n=346) had ≤10% missing data for other covariates. Observations with unobserved outcomes were removed from models. Thus, the final cohort for each outcome was n=308 for BP, n=70 for endothelial function, and n=323 for catecholamines. To summarize these data, variables were stratified into low and high levels of total VOC metabolites. We created a ‘total VOC score’ by summing the Z-score of each of the log transformed and creatinine-corrected metabolites. Values were dichotomized into low and high groups, using the median value of summed Z-scores (−0.3143426). To determine significant differences between low and high total VOCs, we used Chi square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Values of continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as n (%).

To examine the link between environmental VOC exposures and CVD risk, we constructed individual linear regression models by regressing normally distributed BP against each urinary VOC metabolite after adjusting for potential confounders. The levels of catecholamines and their metabolites, and RHI values were positive and right skewed;therefore, we used generalized linear models (GLMs) with a gamma distribution and log link function. Model adjustments were chosen a priori based on the literature for BP and RHI5, 42, 43 and by creation of a directed acyclic graph (Supplemental Figure S4). The relationships between levels of urinary VOC metabolites and BP were adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, and PM2.5. Models including the covariates temperature, seasonal adjustment, median household income by census tract, diabetes, and cotinine did not change the effect estimate by more than 10% and were therefore not included in final models. The relationship between VOC exposures and RHI was adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, diabetes status, and PM2.5. Additionally, we tested BP medications as moderators of the relationship between VOC exposures and BP, and diabetes and hypertension as moderators of the relationship between VOC exposures and RHI. To simulate a dose-response curve, we split the urinary VOC metabolite levels into equal tertiles and constructed adjusted generalized linear models of predicted means for each tertile as the new exposure variable to determine the shape of the exposure-response relationship. The lowest tertile concentration of each VOC metabolite was the reference group. To determine susceptible groups, we performed sub-analyses based on race and sex strata for blood pressure and catecholamine outcome variables. The data was not stratified by age due to high median age among the cohort. RHI was not included in sub-analyses due to small sample size.

To examine the association between VOC exposures and catecholamines, monoamines, and their metabolites, we constructed generalized linear models by regressing each of the ten catecholamines against eachurinary VOC metabolite. We built individual models for each VOC metabolite and adjusted for significant (p<0.1) differences between low and high concentrations of each VOC metabolite. To determine susceptible groups, we performed sub-analyses based on race and sex strata. A list of individual VOC metabolites, stratified descriptive statistics and model estimates, can be found in the supplemental information.

To understand the relationship between exposure to VOCs and BP, we conducted a mediation analysis of VOCs and BP mediated by catecholamines. The mediation analysis was conducted by assessing the direct and indirect effects of each VOC metabolite (X variable) on SBP and DBP (Y variables) with each urinary catecholamine (M) as mediator (Supplemental Figure S30). Analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro in SAS.44 Additionally, we tested the exposure-mediator interaction in the relationship to BP.

In addition to single-VOC models, we created models for multiple VOC exposures. Results are reported for the following five VOC metabolites (CEMA, 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA) of three parent compounds (acrolein, 1,3-butadiene, and crotonaldehyde), which showed consistently positive associations across outcomes. To assess multiple VOC models, we included VOC metabolites that showed statistically significant associations with vascular outcomes in single-VOC models. We applied a Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) approach to flexibly model the relationship between VOC metabolites CEMA, 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA and blood pressure. BKMR is a kernel-regression based method that characterizes the exposure response function of multiple predictors on a health outcome while other predictors are fixed to a specific percentile.45, 46 The method also allows us to examine statistical interactions between VOC metabolites within the mixture and joint associations between the whole mixture and vascularoutcomes.TheBKMR creates posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) that quantify the relative importance of each exposure in the model.45 Hierarchical variable selection is used when components of the mixture are highly correlated (ρ>0.7). Because the VOC metabolites were not highly correlated (Supplemental Figure S14), we did not use the hierarchical variable selection procedure of the BKMR.

Although there were multiple exposure variables, we did not correct for multiple testing in order to test the null hypothesis that all associations were null.47, 48 Furthermore, this is an exploratory analysis where the VOC and CVD connection is not very strong. Thus, we wanted to minimize false negatives. We did not presume that all associations were due to random variation. Values are reported as mmHg or percent difference in outcome per interquartile range (IQR) of VOC metabolite concentration. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for individual VOC models of CEMA, 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA, and R software (version 3.1.3) was used for BKMR analysis46 and graphical displays.

Sensitivity Analysis

We constructed models with and without normalization of VOC metabolites to creatinine.. When the VOC metabolites were not normalized to creatinine, the creatinine variable was included as a covariate in the model. All models were used with the concentrations of VOC metabolites normalized to creatinine. Finally, 11 self-reported smokers were included despite cotinine values of <40ng/mg. The maximum values of cotinine (24.13ng/mg) for the self-reported smokers was much lower than the maximum values of self-reported nonsmokers (38.10 ng/mg). We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine changes in associations with and without self-reported smokers with no difference in result. Thus, we kept nonsmoker status using the above cotinine cut-off of <40ng/mg.

RESULTS

In Table 1, we present descriptive statistics for the restricted non-smoking LHHS participants (n=346) after excluding smoking participants with urinary cotinine values >40ng/mg creatinine. Data for individual covariates were missing for ≤10% of participants. More than half the study population was White, about a third was Black, the mean age was 51.9 years, and the mean BMI was 32.9 kg/m2. Participants with higher VOC metabolite concentrations were older, had higher Framingham risk scores, more comorbidities, and were prescribed more CVD medications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics [number (%) and mean (± standard deviation (SD))] for nonsmoking participants in the Louisville Heathy Heart Study (n=346), stratified by low and high VoC metabolite concentrations.

| Participant Characteristic | Low VOCa | High VOC | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49.3 ± 11.9 | 54.5 ± 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Male | 96 (56.1) | 102 (59.3) | 0.63 |

| Race | 0.8 | ||

| Black (Black v Other) | 55 (32.2) | 50 (28.9) | 0.56 |

| White (White v Other) | 104 (60.5) | 110 (64.0) | 0.24 |

| Other (Other v All) | 13 (7.6) | 12 (6.9) | 0.84 |

| BMI | 32.9 ± 8.0 | 32.8 ± 8.1 | 0.85 |

| Daily Mean PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 12.9 ± 5.0 | 13.7 ± 6.0 | 0.26 |

| Daily Max O3 (μg/m3) | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Temperature (C°) | 12.4 ± 13.2 | 13.3 ± 12.9 | 0.55 |

| Humidity (mg/L) | 22.3 ± 10.7 | 22.2 ± 10.8 | 0.91 |

| Median Household Incomed | 49K ± 31K | 45K ± 26K | 0.22 |

| Framingham Risk Score | 21.1 ± 11.8 | 25.3 ± 9.1 | 0.002 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 77 (45.6) | 102 (59.6) | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | 99 (58.6) | 129 (75.4) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 44 (26.0) | 62 (36.0) | 0.06 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 30 (17.9) | 46 (26.7) | 0.07 |

| Stroke | 10 (5.9) | 13 (7.6) | 0.70 |

| Heart Failure | 18 (10.8) | 28 (16.4) | 0.18 |

| Beta Blockers | 60 (35.9) | 88 (52.4) | 0.003 |

| Ace Inhibitors | 64 (37.9) | 76 (44.7) | 0.24 |

| ARBsc | 11 (6.6) | 20 (11.9) | 0.14 |

| Statins | 59 (35.3) | 82 (48.8) | 0.017 |

| Aspirin | 60 (35.9) | 83 (48.8) | 0.022 |

| Diuretics | 46 (27.5) | 73 (43.5) | 0.003 |

| Vasodilators | 5 (4.0) | 11 (8.0) | 0.28 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 34 (20.4) | 40 (23.8) | 0.53 |

Low and high VOC strata are dichotomized Z-score sums of the log transformed VOC metabolite concentrations normalized to creatinine (ng/mg).

Continuous variables compared between strata by t-tests and categorical variables compared between strata by X2 tests

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers

Reported in thousands (K)

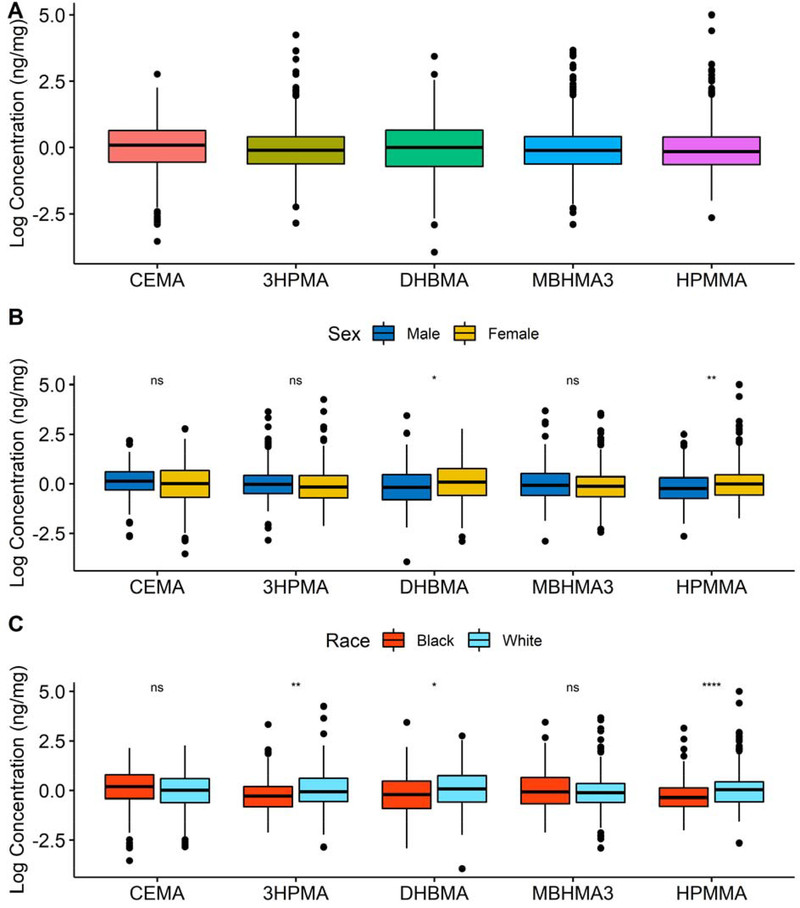

At least 85% of all VOC metabolite observations in the nonsmoking population were above the LOD (Supplemental Table S1). All VOC metabolites were gamma distributed and highly variable. Boxplots of log transformed VOC metabolites normalized to creatinine are presented in Figure 1A. Women (n=198) had higher concentrations of DHBMA and HPMMA compared with men (Figure 1B); and White participants (n=214) had higher concentrations of 3HPMA, DHBMA, and HPMMA compared with Black participants (Figure 1C). Parameter estimates were reported for IQR increase in each VOC metabolite: 88.3ng/mg of creatinine for CEMA, 148.9ng/mg for 3HPMA, 195.0ng/mg for DHBMA, 4.7ng/mg for MHBMA3, and 107.2ng/mg for HPMMA (Table S1). Systolic and diastolic BPs and RHI had a log-normal distribution (Figure S2). Thelevels of catecholamines and metabolites were gamma distributed (Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Exposure distributions of each VOC metabolite, CEMA, 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA, reported as totals (A), and stratified by sex (B) and race (C). Values are reported as the log of the concentration of creatinine corrected urinary VOC metabolites (ng/mg creatinine). Wilcoxon unpaired two sample tests used to compare means. Single asterisk indicates p-values<0.05, 3 asterisks indicate p-values<0.001, and ns indicates not significant, p-values>0.05.

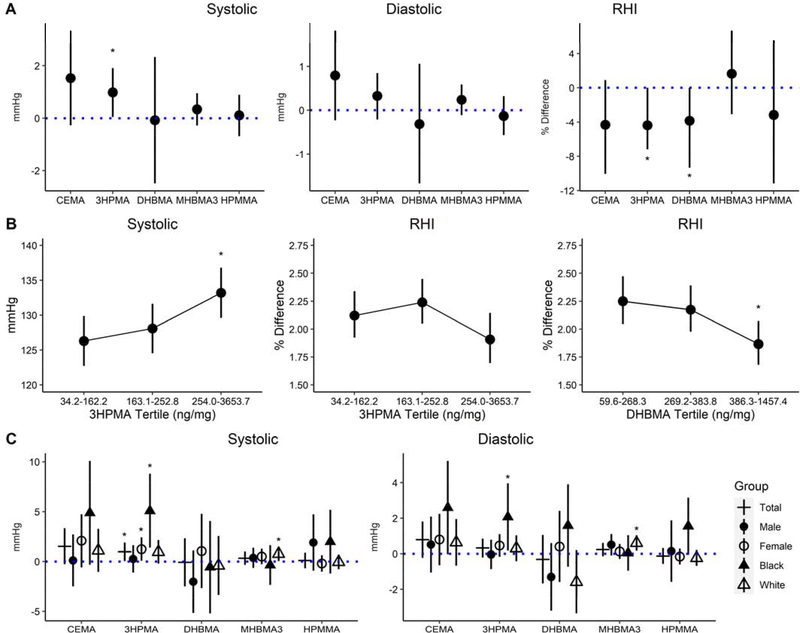

Figure 2A shows fully adjusted estimates for associations with systolic blood pressure (SBP), which were positive per IQR increase in 3HPMA (0.98 mmHg higher; 95% CI: 0.06, 1.91; P=0.038). As shown in Figure 2B, 3HPMA was associated with SBP in an exposure dependent manner. Likewise, for each IQR of 3HPMA or DHBMA, there was a −3.3 % (95% CI: −6.18, 0.37; P=0.024) or a −4.0 % (95% CI: −7.72, −0.12; P=0.012) difference in RHI, respectively, indicating decreased endothelial function. Notably, RHI was lower in an exposure-dependent manner with DHBMA concentrations (1.8%; 95% CI: 1.65, 2.06; P=0.011). Although the reduction in absolute RHI index was similar between 3HPMA and DHBMA, it did not reach statistical significance for 3HPMA. The other acrolein metabolite, CEMA, approached significance in the association with SBP (1.53mmHg; 95% CI: −0.27, 3.34; P=0.097) and RHI (4.3%; 95% CI −10.0, 0.9; P=0.123). Model estimates and 95% confidence intervals are presented in the supplemental information (Supplemental Tables S7–S9).

Figure 2.

Differences (mmHg) and percent differences, and 95% confidence intervals in blood pressure and RHI per IQR of VOC metabolite (A). Predicted means and 95% confidence intervals(mmHg) in blood pressure and % difference in RHI with increasing tertile of 3HPMA and DHBMA (B). Differences and 95% confidence intervals (mmHg) in blood pressure, stratified by sex and race (C). Model adjustments for blood pressure (n=308) include age, sex, race, BMI, daily PM2.5, ace inhibitors, ARBs, and beta blockers. Model adjustments for RHI (n=70) include age, sex, race, BMI, diabetes, and daily PM2.5. Asterisks indicate p-values<0.05. Model estimates can be found in supplemental information.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the entire cohort centered around 129.1±19.7 and 79.6±11.1 mmHg, respectively (Supplemental Figure S2). In comparison, Black participants had higher mean SBP (135.6±23.0 mmHg) and DBP (83.5±11.7.0 mmHg) than White participants’ mean SBP (126.4±17.4 mmHg) and DBP (77.9±10.4 mmHg). Compared with the relationship between 3HPMA and SBP found in the total cohort, Black participants showed a larger association with SBP (5.1 mmHg higher; 95% CI: 1.5, 8.8; P=0.006), despite lower levels of urinary 3HPMA in this population (Figures 1C and 2C). Additionally, women had a larger association with SBP per IQR of 3HPMA (1.2 mmHg higher; 95% CI: 0.08, 2.4; P=0.038). In White participants, estimates were higher for SBP (0.8 mmHg higher; 95% CI: 0.05, 1.5; P=0.037) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (0.6 mmHg higher; 95% CI: 0.2, 1.0; P=0.007) per IQR increase in MHBMA3 (Figure 2C).

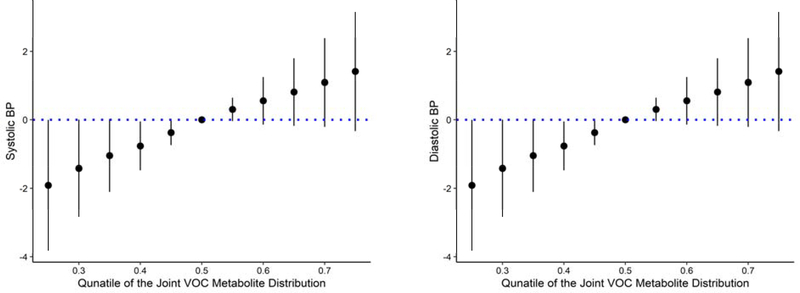

The BKMR analysis allowed for the individual analysis of VOC metabolites with nonlinear relationships, while accounting for correlated exposures. The metabolites 3HPMA and DHBMA had higher posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) for SBP and DBP, respectively (Table 2), indicating that 3HPMA and DBHMA were the most important metabolites of the group in relation to SBP and DBP. There was a positive linear relationship between the whole mixture and SBP, and between the whole mixture and DBP, when all other predictors were fixed at a range of percentiles (25th to 75th by 0.05), compared with when they were fixed to the 50th percentile (Figure 3). When VOC metabolite predictors were fixed to the 50th percentile, the whole mixture exhibited a linear relationship with SBP and DBP in a univariate analysis (Figure S5). There was no evidence of interaction between VOC metabolites when all other exposures were fixed to a percentile or a second VOC was fixed to either the 25th, 50th, or 75th percentile (Figure S16–S18). However, 3HPMA was a critical component of the mixture acting as the primary driver in the relationship with SBP.

Table 2.

Posterior inclusion probabilities of individual VOC metabolites in the Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression model.

| VOCa | SBPa | DBPc |

|---|---|---|

| CEMA | 0.0448 | 0.0412 |

| 3HPMA | 0.1212 | 0.0128 |

| DHBMA | 0.099 | 0.0838 |

| MHBMA3 | 0.0462 | 0.0082 |

| HPMMA | 0.0786 | 0.0242 |

Volatile organic compound metabolite short name

Systolic blood pressure

Diastolic blood pressure

Figure 3.

Overall association of the VOC mixture with SBP and DBP when all predictors are at a particular percentile compared with the value when all predictors are at their 50th percentile. BKMR models were adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, ace inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, and daily PM2.5.

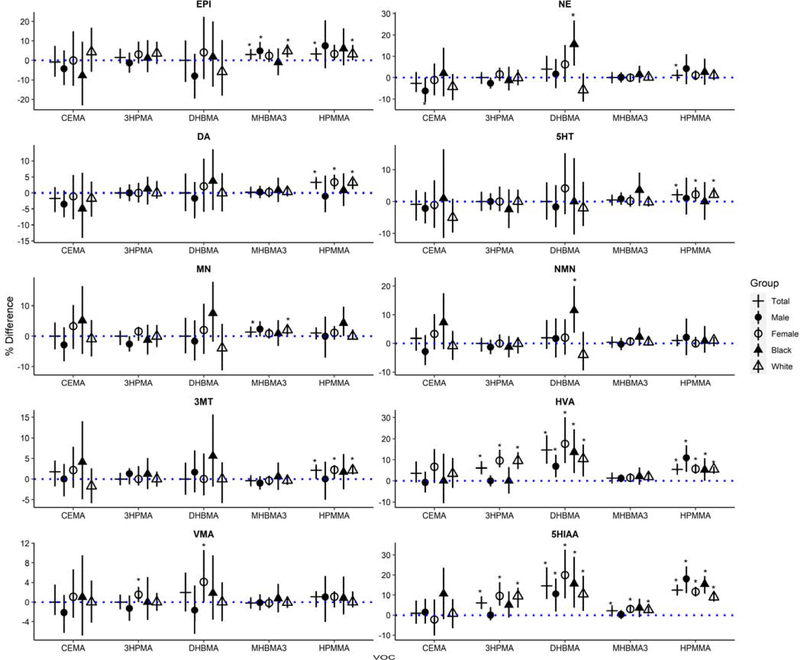

Several catecholamines were significantly associated with VOC metabolites. Urinary EPI levels were positively associated with IQR increases in MHBMA3 (3.1% higher; 95% CI: 0.5, 5.7%; P=0.018) and HPMMA (0.04% higher; 95% CI: 0.0, 6.6%; P=0.036) (Figure 4). Urinary DA levels were positively associated with IQR increases in HPMMA (3.3% higher; 95% CI: 1.1, 4.4%; P=0.001). In Black participants, urinary NE and NMN levels were positively associated with IQR increases in DHBMA (15.7% higher; 95% CI: 5.6, 27.0%; P=0.001; and 11.6% higher; 95% CI: 3.7, 20.0%; P=0.002) compared with the entire cohort. DA and serotonin end products, HVA and 5HIAA, were positively associated with 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA. See supplemental information for model estimates.

Figure 4.

Percent differences and 95% confidence intervals in catecholamines per IQR of VOC metabolite in the total cohort (+). Models were stratified by male participants (filled circle), female participants (open circle), Black participants (fliled triangle), and White participants (open triangle). Catecholamines include epinephrine (EPI), norepinephrine (NE), dopamine (DA), 5-hydroxythreonine (5HT), metanephrine (MN), normetanephrine (NMN), 3-methoxytyramine (3MT), homovanillic acid (HVA), vanillymandelic acid (VMA), and 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5HIAA). Asterisks indicate p-values<0.05. Model estimates can be found in supplemental information.

To understand whether catecholamines modify or mediate relationships between VOC metabolites and markers of vascular dysfunction, we tested for both interaction and mediation. Mediation analyses showed null results (Supplemental Tables S31–32). Although we observed significant direct effects between the acrolein metabolites and catecholamines, there were no significant indirect effects of catecholamines mediating the effects of VOC exposure on blood pressure. However, EPI levels modified the associations of MHBMA3 with DBP (Table S33). Similarly, DA levels modified the association between HPMMA and SBP (Table S34). There was a positive association between MHBMA3 and DBP (0.5% higher; 95% CI: 0.0, 1.0%) in participants with higher urinary levels of EPI tertiles (between 6.6 and 31.5ng/mg). There was a positive association between HPMMA and SBP (3.3% higher; 95% CI: 0.7, 5.9%) in participants with lower levels of EPI (between 0.0 and 3.1 ng/mg). Similarly, there was a positive association between HPMMA and SBP (2.7% higher; 95% CI: 0.0, 5.4%) in participants with lower levels of DA tertiles (between 5.2 and 133.7 ng/mg).

DISCUSSION

In this study of participants with moderate to high CVD risk, we found that metabolites of acrolein and 1,3-butadiene, (3HPMA and DHBMA, respectively), were significantly associated with SBP and endothelial dysfunction. BKMR analyses of the VOC mixture showed a consistent positive and linear relationship of 3HPMA with BP, suggesting that exposure to acrolein alone may be more significant than the pollutant mix containing acrolein. We also found that Black participants may be more susceptible to the effects of acrolein (with respect to SBP) and they had higher levels of NE and NMN associated with 1,3-butadiene exposure. DHBMA was consistently associated with the dopamine metabolite homovanillic acid, across all strata. The crotonaldehyde metabolite, HPMMA, was strongly associated with the serotonin metabolite, 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid. Finally, we report null results of catecholamines mediating the relationship between VOC exposure and blood pressure.

Acrolein is a reactive unsaturated aldehyde known to be associated with CVD risk.30 Acrolein can be produced both endogenously from lipid peroxidation, and exogenously from combustion, chemical production, cigarette smoke, and e-cigarette vapors.40, 49 In the city of Louisville, Jefferson County census tracts were estimated to have some of the highest ambient acrolein concentrations across the state of Kentucky in 2011 and 2014, with point and mobile source emissions (airport and heavy duty vehicles) as top contributors.50 In our analysis, we found that the acrolein metabolite, 3HPMA, was significantly associated with increased SBP in a dose-dependent manner. In our BKMR mixture analysis, 3HPMA appeared to be more relevant than the mixture, indicating that acrolein may be the primary risk driver for BP.

Similar to our results, previous studies have shown that exposure to acrolein increases BP in both normotensive and hypertensive rats.51, 52 Additionally, several experimental studies have shown that exposure to acrolein affects endothelial function by suppressing endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation,53 attenuating endothelial cell migration,54 blocking vascular endothelial growth factor,55 and reducing circulating levels of angiogenic cells.30 Specifically, an intact endothelium mediates dilation of the mesenteric bed in response to acrolein exposure; thus indicating a blunted response with increased sympathetic tone.56 Endothelial function was similarly impaired in tobacco smokers57–59 and e-cigarette users60–63 -two sources of acrolein exposure in the general population. Finally, CVD risk markers, EPI and NE did not increase with respect to acrolein exposure in male Wistar and GK rats.64

The chemical - 1,3-butadiene is an alkene reported to have a possible epidemiological association with arteriosclerotic heart disease.65–67 This chemical is primarily used to make synthetic rubber, but it is also produced from petroleum processing and combustion sources such as vehicle exhaust and cigarette smoke.68 Although our study did not show associations between 1,3-butadiene exposure and BP, one study found normotensive pregnant women had increased odds of high BP when exposed to ambient 1,3-butadiene two hours prior to admission to labor and delivery.20 Another cross-sectional study used principal component analysis of nonsmokers’ personal exposures to ambient VOCs, the authors observed decreased endothelial function and increased DBP in relation to a 1,3-butadiene source in the Detroit Exposure and Aerosol Research Study (DEARS). No effect on SBP was seen.69 Similar to acrolein, several studies suggest 1,3-butadiene as a major cardiovascular risk driver in cigarette smoke.66, 70 However, from these data the singular contribution of 1,3-butadiene exposure to endothelial dysfunction in humans could not be ascertained, as in our study.

Crotonaldehyde is an unsaturated aldehyde and an atherogenic compound.71–73 Crotonaldehyde is produced endogenously from the metabolism of 1,3-butadiene and exogenously from combustion sources like vehicle exhaust and cigarette smoke.74–76 Crotonaldehyde and acrolein did not seem to share similar adverse health effects in our study despite a potential shared mode of action.75 However, crotonaldehyde exposure was weakly associated with EPI, NE, DA, HVA, and 5HT and strongly associated with serotonin metabolite 5HIAA, but had little or no relationship with BP or endothelial function. Consistent with this observation, a recent study shows that chronic inhalation exposure of mice to crotonaldehyde led to decreases in SBP and DBP and enhanced endothelial function.77 Crotonaldehyde is a noncompetitive inhibitor of aldehyde dehydrogenases which have been suggested to be involved in DA metabolism, release, and synthesis.78–80 Furthermore, cigarette smoke, a major source of acrolein, 1,3-butadiene, and crotonaldehyde, has been shown to inhibit monoamine oxidase, a catalyst for the biotransformation of both DA and 5HT to metabolites HVA and 5HIAA, respectively.36 Therefore, our study suggests exposure to crotonaldehyde may affect dopaminergic pathways.

We found that Black participants may be more susceptible to acrolein exposure with respect to SBP, despite lower levels of exposure when compared with White participants. Black individuals are at an increased risk for CVD81 which may be explained by increased susceptibility to acrolein exposure, a major driver of CVD.82 Similar to our study, a previous analysis of NHANES 2005–2006 data reported Black individuals have lower urinary 3HPMA concentrations compared with White individuals.83 However, racial disparities in the relationship between acrolein and blood pressure has not previously been reported. This susceptibility may be explained by a myriad of factors such as access to healthcare or increased stress from systemic racism, and thus requires future research. In Louisville, Kentucky, the National Air Toxics Assessment estimates higher concentrations of acrolein in lower percent Black census tracts, but the health impact of such exposures has not been evaluated.50

Black individuals also had higher levels of NE and NMN associated with 1,3-butadiene exposure. Two large, retrospective epidemiological studies have reported increased standardized mortality ratios for arteriosclerotic heart disease in 1,3-butadiene exposed rubber plant workers, particularly in the Black male population.65–67 Similarly, another study found that Black hypertensive subjects had the more sensitive and highest-density β-receptors,84 and increased α1 and β-adrenergic receptor responsiveness compared with White subjects. 85 Because EPI, NE, and DA are agonists for β-adrenergic receptors, increased catecholamines could produce a higher β-adrenergic response in Black individuals leading to an increased risk for CVD. Additional studies with larger populations are needed to replicate these findings.

In our analyses, catecholamines did not mediate the relationship between VOC exposure and blood pressure. Mediation is the sum of the direct effect (c’) and the indirect effect (a x b) of X on Y, the total effect.44 Although we found significant direct effects between the acrolein metabolites and catecholamines, the indirect effects were null. Therefore, we cannot conclude that catecholamines mediate the effects of VOC exposure on blood pressure in our study. These null effects may be explained by the small magnitude of change in catecholamines. Blood pressure medications, however, may be effect modifiers or confounders of these analyses because they reduce changes in catecholamines and may attenuate the mediating relationship between VOC exposures and blood pressure.

Human populations are exposed to many anthropogenic pollutants which remain as complex mixtures in the air and in toxic waste.5, 86 Chemicals classified as VOCs originate from sources such as industry, Superfund sites, cigarette smoke, and vehicle exhaust. Although there is growing analysis of mixtures and co-pollutants in epidemiology studies, current approaches to assessing the health effects of mixtures have significant disadvantages.45, 46 We used BKMR analysis to flexibly model VOC metabolites CEMA, 3HPMA, DHBMA, MHBMA3, and HPMMA as a mixture to assess the BP health outcome. Our results consistently showed the acrolein metabolite, 3HPMA, was the clear driver of changes in BP. Acrolein metabolism primarily occurs through conjugation with glutathione and conversion to N-acetylcysteine components.87 Of the two metabolites, 3HPMA and CEMA, 3HPMA is the major byproduct and has the higher recovery rate in urine.83 In the mixture analysis, 3HPMA was not confounded by other VOC metabolites and did not interact with other components. Even though 3HPMA confounds the other VOC metabolites, there was still a positive dose response relationship between the mixture and BP. These results suggest 3HPMA is the most relevant VOC metabolite driving the association between exposure and CVDrisk inthiscohort. Furthermore, given the high toxicity and reactivity of acrolein, it appears that acrolein might be the most potent VOC in the ambient air of the three examined, at least in terms of increased CVD risk.

CVD is a complex group of pathological conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels. Although rare cases of CVD can be linked to specific gene-defects, a majority of CVD risk can be attributed to environmental factors such as poor nutrition, physical inactivity, smoking and exposure to air pollution.88–90 There are three proposed biological pathways through which exposure to air pollution could contribute to the development of CVD: 1) systemic oxidative stress and inflammation, 2) autonomic nervous system imbalance, and 3) transmission of constituents from the lung into the blood.5 We observed that exposure to 1,3-butadiene and crotonaldehyde were associated with endothelial dysfunction and biogenic monoamines, and that acrolein exposure was associated with SBP and endothelial dysfunction, suggesting that the risk of CVD attributable to the environment may be in part derived from exposure to VOCs that are ubiquitously present in the environment. Moreover, even though the CVD risk may be affected by a wide range of pollutants, our mixture analyses showed that 3HPMA was the primary driver of BP changes, identifying acrolein as the major VOC of concern particularly in regard to cardiovascular health.

A major advantage of this study is that interindividual differences in exposure were accounted for by using human biomonitoring in the exposure assessment. Another advantage is the removal of smokers based on urinary cotinine values greater than 40 ng/mg of creatinine. Most studies of VOC exposure are unable to account for smoking, or they overestimate the contribution of smoking to VOC exposure. Here, we show how low levels of VOCs may contribute to CVD effects, and that these effects are independent of smoking. Although we chose to use urinary cotinine values greater than 40 ng/mg creatinine to remove smoking individuals, participants could still be exposed to low levels of VOCs from marijuana use, or intermittent smoking. Finally, given that exposures are often complex, heterogeneous, and cumulative, this study uses the BKMR to flexibly model multiple VOC metabolites and their association with CVD health effects.

Limitations of this study include the small sample of nonsmokers, potential bias from cross-sectional study design and classification of nonsmokers, and exposure and outcome measurement error. Misclassification of exposure and outcome is an important source of bias in epidemiologic studies and is a likely limitation of our study. To quantify exposure, we measured urinary metabolites. However, urinary metabolites of VOCs range widely in half-life, and therefore their variable levels due to differences in times of exposure may account for some of the variability in the data and exposure misclassification. Finally, even though we tested multiple associations from individual VOC metabolites, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons which may have allowed for some spurious associations.47

Further work is required to corroborate the findings of our study. Data from larger cohorts with VOC metabolite data may be particularly informative about these associations in the general population. However, cohorts like NHANES do not have extensive data on CVD risk factors or markers of sub-clinical disease progression. While several cohorts such as the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) or the Framingham Heart Study have rich data on CVD risk, progression, and outcomes, they do not, yet have, VOC exposure estimates. Nonetheless, characterization of VOC exposure in these cohorts may be useful in further strengthening the associations identified in our work. Additional work is also required to identify sources of exposure. Source apportionment based on area of residence could be useful in defining geographic exposure contributors.

Approximately 70% of noncommunicable diseases like CVD are attributable to air pollution, the fifth leading human health risk factor.91 Although the effects of PM2.5 exposure on CVD are well documented in the literature, there is a lack of data regarding VOC exposures, which are a major component of air pollution, tobacco smoke, consumer products, and Superfund site generated pollutants. This gap is most likely attributable to the gap in VOC emission inventories and quantification of VOCs in ambient air,15–18 as well as the lack of measurements of VOC metabolites in exposed populations. Recently, volatile chemical products such as pesticides, coatings, printing inks, adhesives, cleaning agents, and personal care projects were reported to make up half of fossil fuel VOC emissions in industrialized cities.12 Our findings suggest that low levels of VOCs can contribute to CVD at least in an at-risk population,8, 38 and highlight the importance of investigating VOC exposure as a risk factor in the development of CVD. Finally, our findings highlight the need to further survey, reduce, and regulate environmental pollutants for the prevention of CVD.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are major components of environmental pollution

Exposure to VOCs is associated with high blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction

Exposure to VOCs was also associated with increased levels of catecholamines

Black participants were more susceptible to vascular changes in response to exposure

Exposure to VOCs may be a significant risk factor in the development of heart disease

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (ES023716, ES019217, ES 029846HL122676, HL 149351, HL 120163, ES011564, ES010349, ES009089, ES029967) and the University of Louisville School of Medicine Integrated Programs in Biomedical Sciences (IPIBS). We would like to acknowledge all lab personnel at the Envirome Institute, especially Tatiana Krivokhizhina and Shweta Srivastava for their help in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds – Acrolein, 1,3-Butadiene, and Crotonaldehyde – is Associated with Vascular Dysfunction in the Louisville Healthy Heart Study

Katlyn E. McGraw, Daniel W. Riggs, Shesh Rai, Ana Navas-Acien, Zhengzhi Xie, Pawel Lorkiewicz, Jordan Lynch, Nagma Zafar, Sathya Krishnasamy, Kira C. Taylor, Daniel J. Conklin, Andrew P. DeFilippis, Sanjay Srivastava, and Aruni Bhatnagar

Katlyn E McGraw is an independent contractor for the Environmental Defense Fund at less than ten hours per month.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatnagar A. Environmental Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. July 7 2017;121(2):162–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization W. Paper presented at: First WHO Global Conference on Air Pollution and Health; 30 October- 1 November 2018, 2018; Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett R, et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet. May 13 2017;389(10082):1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. 2004;109(21):2655–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope CA 3rd, Turner MC, Burnett RT, et al. Relationships between fine particulate air pollution, cardiometabolic disorders, and cardiovascular mortality. Circ Res. January 2 2015;116(1):108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Environmental Protection Agency U. Hazardous Air Pollutants. 17 March 2017. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/haps.

- 8.Konkle SL, Zierold KM, Taylor KC, Riggs DW, Bhatnagar A. National secular trends in ambient air volatile organic compound levels and biomarkers of exposure in the United States. Environ Res. December 2 2019;182:108991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armor JN. Volatile Organic Compounds: An Overview. Environmental Catalysis. Vol 552: American Chemical Society; 1994:298–300. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Environmental Protection Agency U. Volatile Organic Compounds Emissions.

- 11.World Health Organization W. Air Quality Guidelines for Europe. Copenhagen: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald BC, de Gouw JA, Gilman JB, et al. Volatile chemical products emerging as largest petrochemical source of urban organic emissions. Science. February 16 2018;359(6377):760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Pope CA, et al. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(11):1085–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jimenez JL, Canagaratna MR, Donahue NM, et al. Evolution of Organic Aerosols in the Atmosphere. Science. 2009;326(5959):1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strum M, Scheffe R. National review of ambient air toxics observations. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 2016/02/01 2016;66(2):120–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villeneuve PJ, Jerrett M, Su J, et al. A cohort study of intra-urban variations in volatile organic compounds and mortality, Toronto, Canada. Environmental Pollution. 12// 2013;183:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoek G, Beelen R, deHoogh K, et al. A review of land-use regression models to assess spatial variation of outdoor air pollution. Atmospheric Environment. 2008/10/01/ 2008;42(33):7561–7578. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Allen DT, McDonald-Buller EC. Air quality modeling of interpollutant trading for ozone precursors in an urban area. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. October 2005;55(10):1543–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ran J, Qiu H, Sun S, Yang A, Tian L. Are ambient volatile organic compounds environmental stressors for heart failure? Environmental Pollution. 2018/11/01/ 2018;242:1810–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannisto T, Mendola P, Laughon Grantz K, et al. Acute and recentair pollution exposure and cardiovascular events at labour and delivery. Heart. Sep 2015;101(18):1491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendryx M, Luo J, Chen BC. Total and cardiovascular mortality rates in relation to discharges from Toxics Release Inventory sites in the United States. Environ Res. August 2014;133:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villeneuve PJ, Jerrett M, Su J, et al. A cohort study of intra-urban variations in volatile organic compounds and mortality, Toronto, Canada. Environ Pollut. Dec 2013;183:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung CC, Su HJ, Liang HH. Association between indoor air pollutant exposure and blood pressure and heart rate in subjects according to body mass index. Sci Total Environ. January 01 2016;539:271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizukoshi A, Kumagai K, Yamamoto N, et al. A Novel Methodology to Evaluate Health Impacts Caused by VOC Exposures Using Real-Time VOC and Holter Monitors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang BL, Takigawa T, Takeuchi A, et al. Unmetabolized VOCs in urine as biomarkers of low level exposure in indoor environments. J Occup Health. March 2007;49(2):104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X, Freeman NC, Dailey AB, Ilacqua VA, Kearney GD, Talbott EO. Association between exposure to alkylbenzenes and cardiovascular disease among National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants. Int J Occup Environ Health. October-December 2009;15(4):385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim YH, Ock JW, Kim Y-J, Kim Y, Kim SY, Kang D. Association between Heavy Metals, Bisphenol A, Volatile Organic Compounds and Phthalates and Metabolic Syndrome. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(4):671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers DM, Ocariz JM, McGuirk MF, Blount BC. Impact of cigarette smoking on volatile organic compound (VOC) blood levels in the U.S. population: NHANES 2003–2004. Environ Int. November 2011;37(8):1321–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeJarnett N, Conklin DJ, Riggs DW, et al. Acrolein exposure is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Heart Assoc. August 06 2014;3(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abplanalp W, DeJarnett N, Riggs DW, et al. Benzene exposure is associated with cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alwis KU, Blount BC, Britt AS, Patel D, Ashley DL. Simultaneous analysis of 28 urinary VOC metabolites using ultra high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI/MSMS). Anal Chim Acta. October 31 2012;750:152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention C. Laboratory Procedure Manual: Volatile Organic Compound (VOCs) Metabolites. In: Health E, ed. Atlanta, GA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Research Council. Human Biomonitoring for Environmental Chemicals. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sceinces; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Axtell AL, Gomari FA, Cooke JP. Assessing endothelial vasodilator function with the Endo-PAT 2000. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2010(44):2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Z, Lorkiewicz P, Riggs DW, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S. Comprehensive, robust, and sensitive UPLC-MS/MS analysis of free biogenic monoamines and their metabolites in urine. Journal of Chromatography B. 2018/11/01/ 2018;1099:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyle EB, Viet SM, Wright DJ, et al. Assessment of Exposure to VOCs among Pregnant Women in the National Children's Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. March 29 2016;13(4):376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorkiewicz P, Riggs DW, Keith RJ, et al. Comparison of Urinary Biomarkers of Exposure in Humans Using Electronic Cigarettes, Combustible Cigarettes, and Smokeless Tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res. June 2 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute of Health (NIH). Assessing Cardiovascular Risk: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institution; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keith RJ, Fetterman JL, Orimoloye OA, et al. Characterization of Volatile Organic Compound Metabolites in Cigarette Smokers, Electronic Nicotine Device Users, Dual Users, and Nonusers of Tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res. February 6 2020;22(2):264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Avila-Tang E, Al-Delaimy WK, Ashley DL, et al. Assessing secondhand smoke using biological markers. Tob Control. May 2013;22(3):164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization W. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Accessed 22 November 2017.

- 43.Kahn SE, Cooper ME, Del Prato S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. The Lancet.383(9922):1068–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach: Guilford publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bobb JF, Valeri L, Claus Henn B, et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics. July 2015;16(3):493–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bobb JF. Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression [R package bkmr version 0.2.0]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). Available at: https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/bkmr/index.html. Accessed 18 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg M, Silbergeld E. On multiple comparisons and on the design and interpretation of epidemiological studies of many associations. Environmental Research. 2011/11/01/ 2011;111(8):1007–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothman KJ. No adjustment sare needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. January 1990;1(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh M, Kapoor A, Bhatnagar A. Oxidative and reductive metabolism of lipid-peroxidation derived carbonyls. Chem Biol Interact. June 5 2015;234:261–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Air Toxics Assessment. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/atw/natamain/.

- 51.Perez CM,Hazari MS, Ledbetter AD,et al. Acroleininhalationaltersarterialbloodgases and triggers carotid body-mediated cardiovascular responses in hypertensive rats. Inhal Toxicol. January 2015;27(1):54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez CM, Ledbetter AD, Hazari MS, et al. Hypoxia stress test reveals exaggerated cardiovascular effects in hypertensive rats after exposure to the air pollutant acrolein. Toxicol Sci. Apr 2013;132(2):467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ismahil MA, Hamid T, Haberzettl P, et al. Chronic oral exposure to the aldehyde pollutant acrolein induces dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. November 2011;301(5):H2050–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Toole TE, Abplanalp W, Li X, et al. Acrolein decreases endothelial cell migration and insulin sensitivity through induction of let-7a. Toxicol Sci. Aug 1 2014;140(2):271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wheat LA, Haberzettl P, Hellmann J, et al. Acrolein inhalation prevents vascular endothelial growth factor-induced mobilization of Flk-1+/Sca-1+ cells in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. July 2011;31(7):1598–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Awe SO, Adeagbo ASO, D'Souza SE, Bhatnagar A, Conklin DJ. Acrolein induces vasodilatation of rodent mesenteric bed via an EDHF-dependent mechanism. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2006/12/15/ 2006;217(3):266–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.George J, Hussain M, Vadiveloo T, et al. Cardiovascular Effects of Switching From Tobacco Cigarettes to Electronic Cigarettes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(25):3112–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyata S, Noda A, Ito Y, Iizuka R, Shimokata K. Smoking acutely impaired endothelial function in healthy college students. Acta Cardiologica. 2015/06/01 2015;70(3):282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Esen AM, Barutcu I, Acar M, et al. Effect of Smoking on Endothelial Function and Wall Thickness of Brachial Artery. Circulation Journal. 2004;68(12):1123–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carnevale R, Sciarretta S, Violi F, et al. Acute Impact of Tobacco vs Electronic Cigarette Smoking on Oxidative Stress and Vascular Function. Chest. 2016/09/01/ 2016;150(3):606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fetterman Jessica L, Keith Rachel J, Palmisano Joseph N, et al. Alterations in Vascular Function Associated With the Use of Combustible and Electronic Cigarettes. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020/05/05 2020;9(9):e014570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fetterman JL, Weisbrod RM, Feng B, et al. Flavorings in Tobacco Products Induce Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2018;38(7):1607–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuntic M, Oelze M, Steven S, et al. Short-terme-cigarette vapour exposure causes vascular oxidative stress and dysfunction: evidence for a close connection to brain damage and a key role of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase (NOX-2). European heart journal. 2020;41(26):2472–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snow SJ, McGee MA, Henriquez A, et al. Respiratory Effects and Systemic Stress Response Following Acute Acrolein Inhalation in Rats. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2017;158(2):454–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Divine BJ, Hartman CM. Mortality update of butadiene production workers. Toxicology. 1996/10/28/ 1996;113(1):169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Penn A, Snyder CA. 1,3-Butadiene exposure and cardiovascular disease. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2007/08/01/ 2007;621(1):42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matanoski GM, Santos-Burgoa C, Schwartz L. Mortality of a cohort of workers in the styrene-butadiene polymer manufacturing industry (1943–1982). Environ Health Perspect. June 1990;86:107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Center for Biotechnology Information. 1,3-Butadiene. PubChem Database. Available at: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1_3-Butadiene, 24 July 2020.

- 69.Shin HH, Jones P, Brook R, Bard R, Oliver K, Williams R. Associations between personal exposures to VOCs and alterations in cardiovascular physiology: Detroit Exposure and Aerosol Research Study (DEARS). Atmospheric Environment. 2015/03/01/ 2015;104(Supplement C):246–255. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soeteman-Hernández LG, Bos PMJ, Talhout R. Tobacco smoke-related health effects induced by 1,3-butadiene and strategies for risk reduction. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2013;136(2):566–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhatnagar A. Cardiovascular pathophysiology of environmental pollutants. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. February 2004;286(2):H479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Conklin DJ. Acute cardiopulmonary toxicity of inhaled aldehydes: role of TRPA1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. June 2016;1374(1):59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Toole TE, Zheng YT, Hellmann J, Conklin DJ, Barski O, Bhatnagar A. Acrolein activates matrix metalloproteinases by increasing reactive oxygen species in macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. April 15 2009;236(2):194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Conklin DJ, Ogunwale MA, Chen Y, et al. Electronic cigarette-generated aldehydes: The contribution of e-liquid components to their formation and the use of urinary aldehyde metabolites as biomarkers of exposure. Aerosol science and technology: the journal of the American Association for Aerosol Research. 2018;52(11):1219–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grant RL, Jenkins AF. Use of In Vivo and In Vitro Data to Derive a Chronic Reference Value for Crotonaldehyde Based on Relative Potency to Acrolein. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part B, Critical reviews. 2015;18(7–8):327–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.National Center for Biotechnology Information. Crotonaldehyde. PubChem Database. Available at: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Crotonaldehyde Accessed 25 July 2020.

- 77.Lynch J, Jin L, Richardson A, et al. Acute and chronic vascular effects of inhaled crotonaldehyde in mice: Role of TRPA1. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2020/09// 2020;402:115120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koppaka V, Thompson DC, Chen Y, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitors: a comprehensive review of the pharmacology, mechanism of action, substrate specificity, and clinical application. Pharmacological reviews. 2012;64(3):520–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.LoPachin RM, Barber DS, Gavin T. Molecular mechanisms of the conjugated alpha, beta-unsaturated carbonyl derivatives: relevance to neurotoxicity and neurodegenerative diseases. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2008;104(2):235–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rees JN, Florang VR, Anderson DG, Doorn JA. Lipid peroxidation products inhibit dopamine catabolism yielding aberrant levels of a reactive intermediate. Chem Res Toxicol. October 2007;20(10):1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frieden TR. CDC health disparities and inequalities report-United States, 2013. Foreword. MMWR supplements. 2013;62(3):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Henning RJ, Johnson GT, Coyle JP, Harbison RD. Acrolein Can Cause Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2017/07/01 2017;17(3):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alwis KU, deCastro BR, Morrow JC, Blount BC. Acrolein Exposure in U.S. Tobacco Smokers and Non-Tobacco Users: NHANES 2005–2006. Environmental health perspectives. 2015;123(12):1302–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG, Nelesen RA. Racial differences in epinephrine and beta 2-adrenergic receptors. Hypertension. January 1995;25(1):88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sherwood A, Hill LK, Blumenthal JA, Johnson KS, Hinderliter AL. Raceand sex differences in cardiovascular α-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptor responsiveness in men and women with high blood pressure. Journal of hypertension. 2017;35(5):975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lybarger JA, Lee R, Vogt DP, Perhac RM, Jr., Spengler RF, Brown DR. Medical costs and lost productivity from health conditions at volatile organic compound-contaminated superfund sites. Environ Res. October 1998;79(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stevens JF, Maier CS. Acrolein: sources, metabolism, and biomolecular interactions relevant to human health and disease. Molecular nutrition & food research. 2008;52(1):7–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Flowers E, Froelicher ES, Aouizerat BE. Gene-Environment Interactions in Cardiovascular Disease. European journal of cardiovascular nursing: journal of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Nursing of the European Society of Cardiology. 03/June 2012;11(4):472–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhatnagar A. Environmental cardiology: studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Circ Res. September 29 2006;99(7):692–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Riggs DW, Yeager RA, Bhatnagar A. Defining the Human Envirome: An Omics Approach for Assessing the Environmental Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. April 27 2018;122(9):1259–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.