SUMMARY

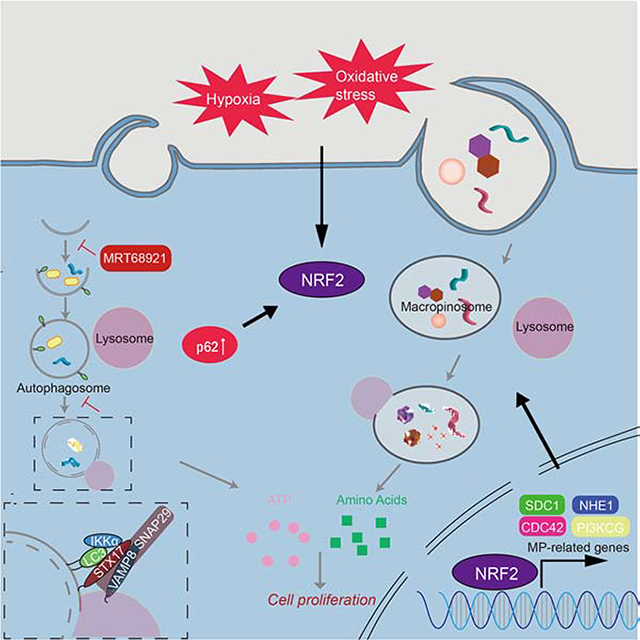

Many cancers, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), depend on autophagy-mediated scavenging and recycling of intracellular macromolecules, suggesting that autophagy blockade should cause tumor starvation. However, till now autophagy inhibiting monotherapies have not demonstrated potent anti-cancer activity. We now show that autophagy blockade prompts established PDAC to upregulate and utilize an alternative nutrient procurement pathway: macropinocytosis (MP) that allows tumor cells to extract nutrients from extracellular sources and use them for energy generation. The autophagy to MP switch, which may be evolutionarily conserved and not cancer cell restricted, depends on activation of transcription factor NRF2 by the autophagy adaptor p62/SQSTM1. NRF2 activation by oncogenic mutations, hypoxia and oxidative stress also results in MP upregulation. Inhibition of MP in autophagy compromised PDAC elicits dramatic metabolic decline and regression of transplanted and autochthonous tumors, suggesting the therapeutic promise of combining autophagy and MP inhibitors in the clinic.

Keywords: Autophagy, Macropinocytosis, NRF2, p62/SQSTM1, RAS-driven cancer

eTOC Blurb

Su et al., show that autophagy inhibition upregulates MP, which provides nutrients supporting the growth of autophagy deficient cancers. The autophagy to MP switch depends on NRF2-driven induction of MP-related proteins.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved, quality control process that maintains cellular homeostasis (Green and Levine, 2014; Levine and Kroemer, 2019) and suppresses tumor initiation (Gozuacik and Kimchi, 2004; Levine, 2007; Nassour et al., 2019; Umemura et al., 2016). Paradoxically, autophagy is upregulated in established cancers, supporting their high metabolic rates and energetic demands by releasing amino acids (AA) and other components from lysosome degraded intracellular macromolecules (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005). These findings imply that autophagy inhibition should cause tumor starvation and regression. However, chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which disrupt lysosomal acidification and manifest anti-cancer activity in mice (Yang et al., 2011), have not improved overall patient survival when combined with chemotherapy (Karasic et al., 2019). Specific blockade of autophagy initiation is also ineffective, unless combined with ERK or MEK inhibition (Bryant et al., 2019; Kinsey et al., 2019). Therapeutic autophagy inhibition has been of particular interest in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common and lethal pancreatic malignancy (Ying et al., 2016). Most PDACs, often detected at an advanced metastatic stage, express high levels of autophagy and lysosome biosynthesis genes, correlating with MIT/TFE transcription factor upregulation (Perera et al., 2015). These findings further suggest that uninterrupted autophagy promotes PDAC growth and survival (Bryant and Der, 2019), a concept established in mouse models (Yang et al., 2014).

PDACs are usually initiated by KRAS mutations and harbor several other dominant genetic alterations (Ying et al., 2016). Oncogenic KRAS signaling to phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) post-translationally activates another nutrient procurement pathway, macropinocytosis (MP), in which cancer cells take up extracellular fluid droplets containing proteins and other macromolecules (Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017). Like autophagy, MP is an evolutionarily conserved and lysosome-dependent degradation pathway (Bloomfield and Kay, 2016; King and Kay, 2019). However, how any MP-enabled organism, including cancer cells, coordinately regulates and balances autophagy and MP is not fully understood, although this conundrum was recently discussed (Florey and Overholtzer, 2019). Here, while investigating the regulation of autophagic flux in human PDAC, we discovered that autophagy inhibition makes PDAC cells switch from autophagic degradation and metabolism of intracellular components to utilization of extracellular proteins taken-up via MP. This autophagy to MP switch depends on the conserved pathway of p62/SQSTM1 accumulation, KEAP1 titration and NRF2 activation (Ichimura and Komatsu, 2018; Moscat et al., 2016). NRF2 serves as the central transcriptional activator of the MP program and its nuclear accumulation in PDAC correlates with increased expression of critical MP proteins. Dual blockade of autophagy initiation and MP results in robust tumor regression.

RESULTS

IKKα Controls Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion in Human PDAC

IKKα ablation in mouse pancreatic epithelial cells (PEC) impairs autophagy termination (Li et al., 2013) and accelerates progression of KrasG12D initiated PDAC (Todoric et al., 2017). We wondered whether low IKKα expression reduces autophagic flux in human PDAC and how tumors with low autophagic flux survive under stringent conditions. We silenced (KD) IKKα in MIA PaCa-2 human PDAC cells and used additional PDAC cultures generated from patient derived xenografts (PDX) that greatly differ in IKKα expression. IKKα-KD MIA PaCa-2 cells showed reduced GFP-LC3 reporter cleavage before and after glucose starvation and displayed more LC3 puncta, lipidated LC3-II and p62 (Figures S1A–S1C), confirming proper initiation but defective degradation. Accordingly, CQ treatment did not increase p62 and LC3-II in these cells (Figure S1C). Immunoblot (IB) analysis of human PDAC PDXs showed that low IKKα specimens had high p62 and NRF2 (Figure S1D). We prepared 2D cultures from these PDXs, including 1444 with high IKKα and low p62, LC3-II, LC3 puncta and nuclear NRF2, and 1305 and 1334 with low IKKα and high p62, LC3-II, LC3 puncta and nuclear NRF2 (Figures S1E and S1F). IKKαlow cells showed reduced GFP-LC3 cleavage (Figure S1G). IKKα introduction into 1334 cells or IKKα ablation (Δ) in 1444 cells confirmed that low IKKα closely correlated with reduced autophagic degradation (Figures S1H–S1J).

Supporting an effect on autophagosome-lysosome fusion, LC3-LAMP1 co-localization was diminished in IKKα-KD cells (Figure S1K). Autophagosome-lysosome fusion is mediated by soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex, composed of STX17 which connects SNAP29 on autophagosomes and VAMP8 on lysosomes (Itakura et al., 2012). IKKα KD dramatically inhibited SNAP29:STX17:VAMP8 complex formation before and after starvation (Figure 1A). IKKα harboring several LC3 interaction (LIR) motifs, interacted with LC3, especially during starvation (Figures 1B, S2A and S2B), but IKKβ, which does not affect pancreatic autophagy (Li et al., 2013), did not associate with LC3. IKKα KD prevented STX17-autophagosome localization and abolished STX17 association with LC3 (Kumar et al., 2018) in fed and starved cells (Figures 1C and 1D). Correspondingly, LC3 and STX17 co-immunoprecipitated (IP) with IKKα, especially during starvation (Figure 1E). Y568A and W651A substitutions within two of the IKKα LIR motifs abolished LC3 binding and STX17 recruitment (Figure S2C). Re-expression of WT but not LIR-mutated IKKα in IKKα-deficient cells restored STX17 co-IP with LC3 and SNAP29, VAMP8 co-IP with STX17 and LC3-LAMP1 co-localization (Figures 1F, S2D and S2E). IKKα localized to autophagosomes during starvation; although the amounts were low due to the dynamic nature of the fusion process, in situ proximity ligation supported IKKα:LC3 interaction (Figures S2F and S2G), which was STX17 independent (Figure S2H) and may be direct due to presence of functional LIR motifs in IKKα. We suggest that IKKα stabilizes the LC3-STX17 interaction, thus facilitating SNARE complex formation (Figure S2I).

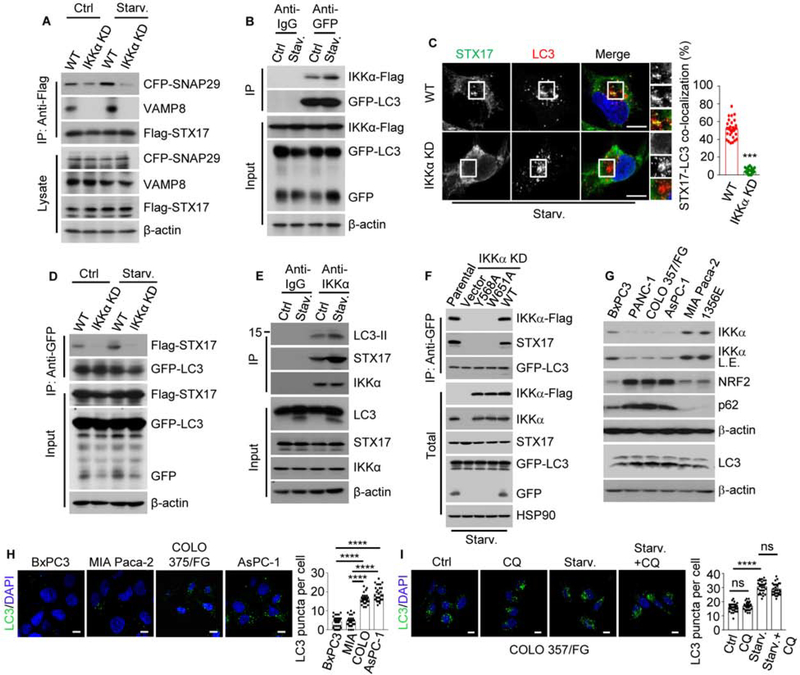

Figure 1. IKKα Promotes Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion by Bridging LC3 and STX17.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of CFP-SNAP29 and endogenous VAMP8 with Flag-STX17 from controlled and starved (for 2 hrs.) MIA PaCa-2 cells.

(B) Co-IP of IKKα-Flag with GFP-LC3 from controlled and starved MIA PaCa-2 cells.

(C) LC3 and STX17 co-localization in parental (WT) and IKKα KD MIA PaCa-2 cells incubated in starvation medium for 2 hrs. The right-hand panels show higher magnifications of the areas marked by squares. Quantification is shown to the right.

(D) Co-IP of Flag-STX17 with GFP-LC3 in above cells.

(E) Co-IP of LC3 and STX17 with endogenous IKKα from control and starved ΜιΑ PaCa-2 cells.

(F) Co-IP of endogenous STX17 and transiently expressed Flag-tagged WT and LIR-mutated IKKα variants with GFP-LC3.

(G) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of human PDAC cell lines with high and low IKKα expression.

(H) LC3 puncta in IKKα high and low PDAC cells. Quantification is on the right.

(I) LC3 puncta in COLO 357/FG cells incubated in normal or starvation medium for 2 hrs +/− chloroquine (CQ). Quantification is on the right.

Results in (C), (H) and (I) are mean ± SEM (n=30). Scale bar, 10 μm. Statistical significance was determined by 2-tailed t-test. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

The MIA PaCa-2, BxPC3 and the PDX-derived 1356E cell lines are IKKαhigh, whereas AsPC-1, COLO-357/FG, and PANC-1 are ιΚΚαlow (Figure 1G). IKKαlow cells showed more p62, NRF2 and LC3 puncta than IKKαhigh cells (Figures 1G and 1H). Starvation increased LC3 puncta and lipidation but did not decrease p62 in IKKαlow COLO-357/FG cells, and was not affected by CQ treatment (Figures 1I and S2J), suggesting proper initiation but defective degradation. Indeed, IKKα transfection into these cells reduced both p62 and LC3-II (Figure S2K).

Compromised Autophagy Stimulates Macropinocytosis

We next investigated how human PDAC cells with low autophagic flux survive under stringent conditions. MP, activated by oncogenic KRAS, provides an alternative nutrient procurement pathway through which cancer cells take up extracellular material (Palm, 2019; Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017). Remarkably, isolated Ikkα-null KrasG12D PEC (KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC) with low autophagic flux (Figures S3A and S3B) and intact pancreata showed dramatic upregulation of numerous MP-related genes (Dolat and Spiliotis, 2016; Lim and Gleeson, 2011; Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017; Yao et al., 2019), including MP-stimulating growth factors and receptors, and exhibited higher MP rates, measured by tetramethylrhodamine-labeled high-molecular-mass dextran (TMR-DEX) uptake, than young or old KrasG12D counterparts with similar tumor burden (Figures 2A–2D). IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 and 1444 cells behaved similarly (Figures 2E and 2F). TMR-DEX labeling was inhibited by 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride (EIPA), a tool compound that blocks macropinosome formation (Ivanov, 2008). KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC PEC and pancreata expressed more MP-related proteins and had more surface-localized syndecan 1 (SDC1) and Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1, the target for EIPA) than young or old KrasG12D counterparts (Figures 2G and 2H), suggesting higher SDC1-controlled RAC1 activity (Yao et al., 2019). To determine whether MP-internalized albumin is lysosomally degraded, we co-incubated IKKα-sufficient and -deficient cells with a self-quenched BODIPY-conjugated BSA (DQ-BSA) which fluoresces after proteolytic digestion. There were no appreciable differences between IKKα-sufficient and -deficient MIA PaCa-2 cells that were immediately fixed following a 30-min incubation with DQ-BSA and TMR-DEX (Figure 2I). However, after a 1 hr chase without indicators, IKKαΔ cells exhibited more DQ-BSA fluorescence in TMR-positive vesicles.

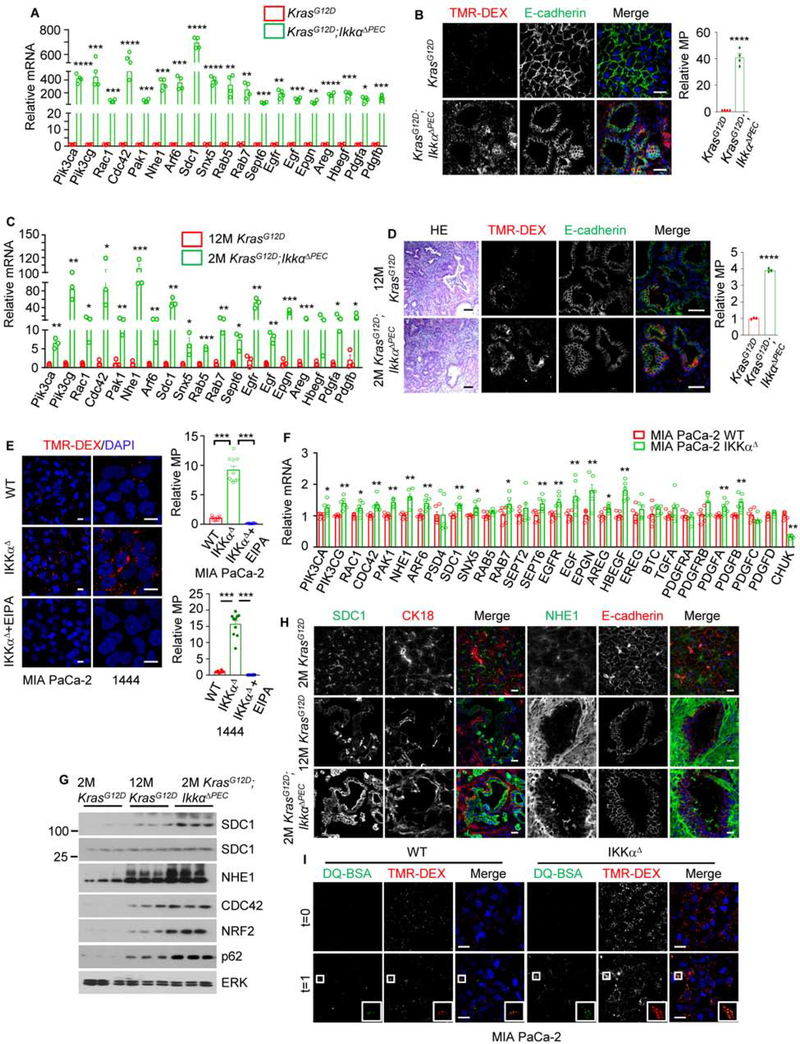

Figure 2. IKKα Deficiency Upregulates MP.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of MP-related mRNAs in pancreatic epithelial cells (PEC) from 8-week-old (wo) mice of indicated genotypes. Mean ± SEM (n=4 mice).

(B) Representative images and quantification of MP in TMR-dextran (TMR-DEX: red) injected pancreatic tissue from 8-wo mice of indicated genotypes. PEC or carcinoma cells are marked by E-cadherin staining (green). Quantification is on the right. Scale bar, 10 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=4 mice).

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of MP-related mRNAs in PEC from 12-month-old (mo) KrasG12D and 2-mo KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC mice. Mean ± SEM (n=3 mice).

(D) H&E staining and representative images of TMR-DEX uptake and in pancreata of above mice. Quantification is on the right. Scale bar, 20 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=3 mice).

(E) MP visualization and quantification using TMR-DEX in parental and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2/1444 cells +/− 75 μM EIPA. Scale bar, 10 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=10).

(F) qRT-PCR analysis of MP-related mRNAs in WT and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells. Mean ± SEM (n=6).

(G) IB analysis of MP-related proteins in PEC isolated from indicated mice.

(H) Images of SDC1 and NHE1 localization in pancreata of above mice. PanIN and PDAC cells are marked with a cytokeratin 18 (CK18, red) or E-cadherin (red) antibodies. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(I) DQ-BSA fluorescence in WT and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells co-incubated with DQ-BSA and TMR-DEX and fixed after 30 min (t=0) or after a 1 hr chase (t=1). The DQ-BSA signal reflects albumin degradation. Insets show higher magnifications of marked areas. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Statistical significance in (A)-(F) was determined by a 2-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

The Autophagy to MP Switch Depends on NRF2

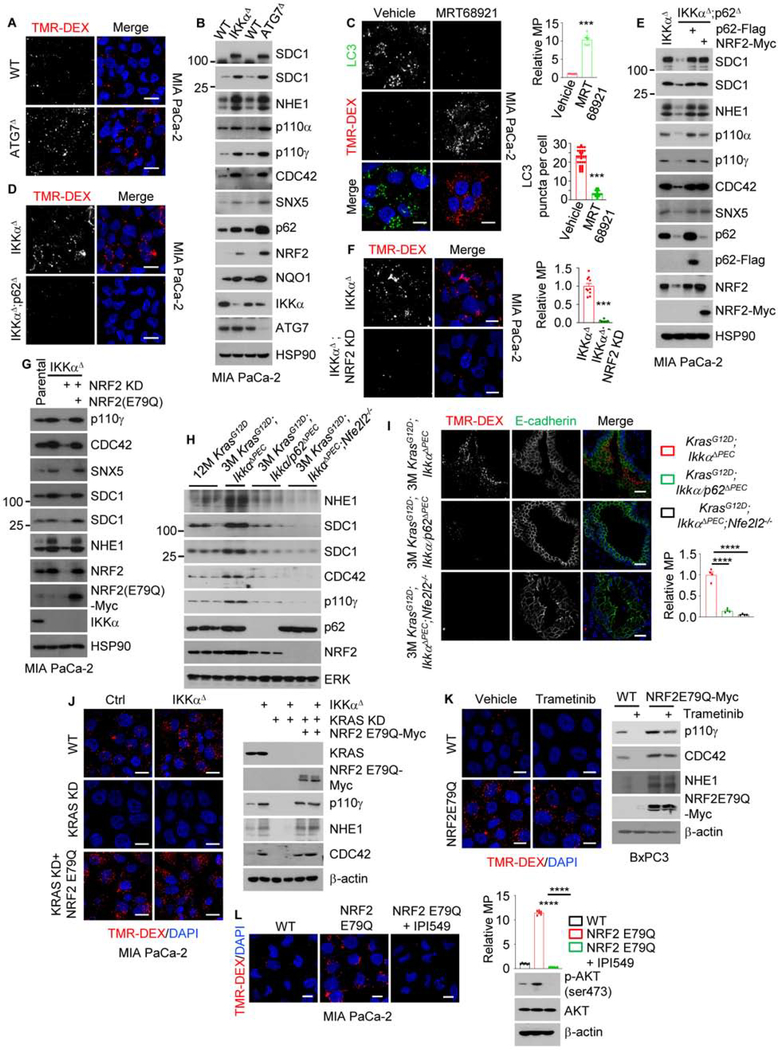

ATG7Δ or STX17 KD MIA PaCa-2 and BxPC3 cells also showed increased TMR-DEX uptake and MP-related mRNA expression (Figures 3A and S3C–S3G). ATG7 or STX17 ablation induced p62 accumulation and upregulated NRF2 and key MP proteins: SDC1, NHE1, p110α, p110γ, CDC42 and/or SNX5 (Figures 3B and S3H). The ULK1/2 inhibitor MRT68921 increased macropinosomes and reduced autophagosomes (Figure 3C). p62 or NRF2 ablation/inhibition in IKKαΔ or STX17 KD MIA PaCa-2 or BxPC3 cells prevented the increase in MP-related mRNAs, proteins and activity, whereas their re-introduction restored MP-related protein expression (Figures 3D–3G and S3G–S3M). Similar results were obtained in KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC PEC (Figures 3H, 3I and S3N). MP activity and related proteins were higher in IKKαlow;NRF2high than IKKαhigh;NRF2low cells (Figures S4A–S4D). IKKα overexpression or NRF2 KD in COLO-357/FG cells reduced NRF2 nuclear localization, MP activity and protein expression, whereas NRF2 transfection upregulated MP-related mRNAs and proteins, increased their surface localization and stimulated MP (Figures S4E–S4J). Oncogenic KRAS, which stimulates MP, induces NRF2-encoding NFE2L2 mRNA expression via a RAF-MEK-ERK-Jun cascade (DeNicola et al., 2011). Accordingly, KRAS ablation diminished MP and NRF2 expression in parental and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells (Figures 3J and S4K). Similar results were observed in MEK inhibitor (trametinib) treated-BxPC3 cells expressing WT KRAS and mutant RAF (Figures S4L and S4M). Importantly, neither KRAS KD nor trametinib inhibited MP activity and protein expression in MIA PaCa-2 and BxPC3 cells overexpressing KEAP1-resistant NRF2(E79Q) (Figures 3J and 3K), suggesting that NRF2 upregulates MP independently of RAS-RAF signaling. p110γ inhibition diminished MP activity in NRF2(E79Q) overexpressing cells supporting an important role for p110γ induction in NRF2-stimulated MP (Figure 3L). Curiously, KRAS ablation and MEK inhibition activated AMPK and ULK1 in parental and IKKαΔ cells but downregulated p62 only in parental cells (Figures S4K and S4M), suggesting that MEK inhibition stimulates autophagy initiation.

Figure 3. The Autophagy-to-MP Switch Requires p62-Mediated NRF2 Activation.

(A) Macropinosomes in WT and ATG7Δ MIA PaCa-2 cells imaged with TMR-DEX. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) IB analysis of MP-related proteins in WT, ATG7Δ and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells.

(C) Autophagosomes and macropinosomes in MIA PaCa-2 cells treated +/− MRT68921. Scale bar, 10 μm. Relative macropinocytic uptake was quantitated (on the right), mean ± SEM (n=7). Autophagosome puncta per cell were measured, mean ± SEM (n=30).

(D) Macropinosomes in IKKαΔ and IKKαΔ;p62Δ (DKO) MIA PaCa-2 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) IB analysis of above cells +/− exogenous p62 or NRF2 transfection.

(F) Macropinosome imaging and quantification in IKKαΔ and IKKαΔ;NRF2 KD MIA PaCa-2 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=10).

(G) IB analysis of WT, IKKαΔ and IKKαΔ;NRF2 KD MIA PaCa-2 cells +/− exogenous NRF2.

(H) IB analysis of MP-related proteins in PEC isolated from the indicated mouse strains (n=2–3).

(I) MP visualization and quantification in pancreata of indicated mice. Scale bar, 20 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=4 mice).

(J) Imaging of macropinosomes and IB analysis of indicated proteins in WT and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells +/− KRAS KD and +/− NRF2(E79Q)-Myc. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(K) Imaging of macropinosomes and IB analysis of indicated proteins in WT and NRF2(E79Q)-Myc-overexpressing (OE) BxPC3 cells treated +/− trametinib (100 nM). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(L) Imaging of macropinosomes and IB analysis of indicated proteins in WT and NRF2(E79Q)-Myc-OE MIA PaCa-2 cells treated +/− p110γ inhibitor IPI549 (600 nM). Scale bar, 10 μm. Relative macropinocytic uptake was quantitated (on the right), mean ± SEM (n=6).

Statistical significance in (C), (F), (I) and (L) was determined by a 2-tailed t-test. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

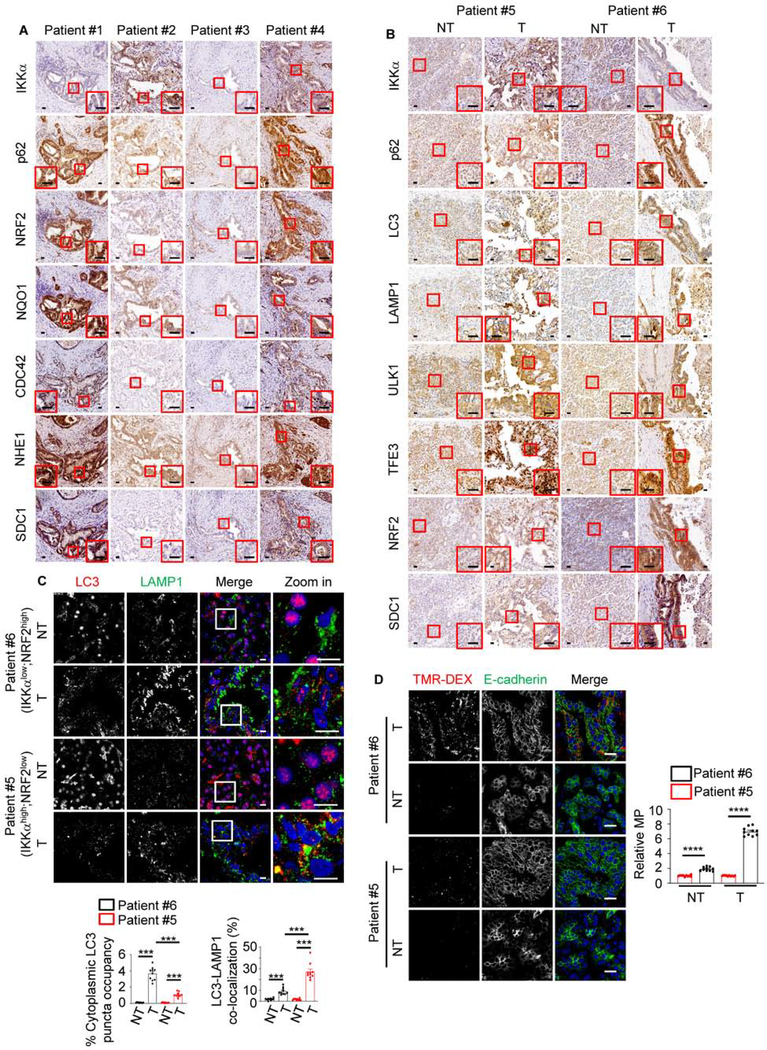

Examination of RNAseq data from 177 PDAC patients, revealed significant positive correlation between MP-related and SQSTM1 or NFE2L2 mRNAs (Figure S5A). Similar results were obtained by IHC analysis of human PDAC specimens, 31% (31/100) of which were IKKαlow with 25 of them showing high p62 and NRF2 (Figures 4A, S5B and S5C). Most IKKαlow;p62high;NRF2high tumors showed elevated NHE1 (76%), SDC1 (76%) and CDC42 (80%) (Figure S5C). However, as seen in PDXs, some IKKαhigh tumors had high NRF2, which still correlated with elevated MP-related proteins, especially CDC42, NHE1 and SDC1 (R = 0.33, p = 0.0008; R = 0.3070, p = 0.0019; R = 0.3005, p = 0.0024) (Figure 4A), supporting an IKKα-independent link between NRF2 and MP-related gene expression. As reported (Perera et al., 2015), PDAC tissue contained more ULK1, LC3, LAMP1 and TFE3 than non-tumor tissue, suggesting higher basal autophagy (Figure 4B). Overall, p62, LC3 and MP-related proteins were higher in IKKαlow than IKKαnormal or IKKαhigh PDAC, suggesting defective autophagic degradation, confirmed by increased LC3 puncta and reduced LC3-LAMP1 co-localization (Figure 4C). A freshly resected IKKαlow;NRF2high tumor showed higher MP activity than an IKKαhigh;NRF2low tumor (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. MP is Upregulated in NRF2high Human PDAC.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of human PDAC tissues. The areas marked by the squares were further magnified. Scale bars, 25 μm.

(B) Representative IHC of non-tumor (NT) and tumor (T) areas in IKKαhigh (patient #5) and IKKαlow (patient #6) human PDAC specimens. Marked areas were examined under higher magnification. Scale bars, 25 μm.

(C) Imaging and quantification (on the bottom) of LC3 puncta and LC3-LAMP1 co-localization in above specimens. Mean ± SEM (n=10 patients). Statistical significance was determined by a 2-tailed t-test; ***p < 0.001. Scale bars, 10 μm

(D) Representative images and MP quantification (on the right) in TMR-DEX injected fresh surgical specimens from patients #5 (IKKαhigh;NRF2low tumor) and #6 (IKKαlow;NRF2high tumor). PEC or carcinoma cells are marked by E-cadherin staining. Scale bar, 20 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=10). ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S5.

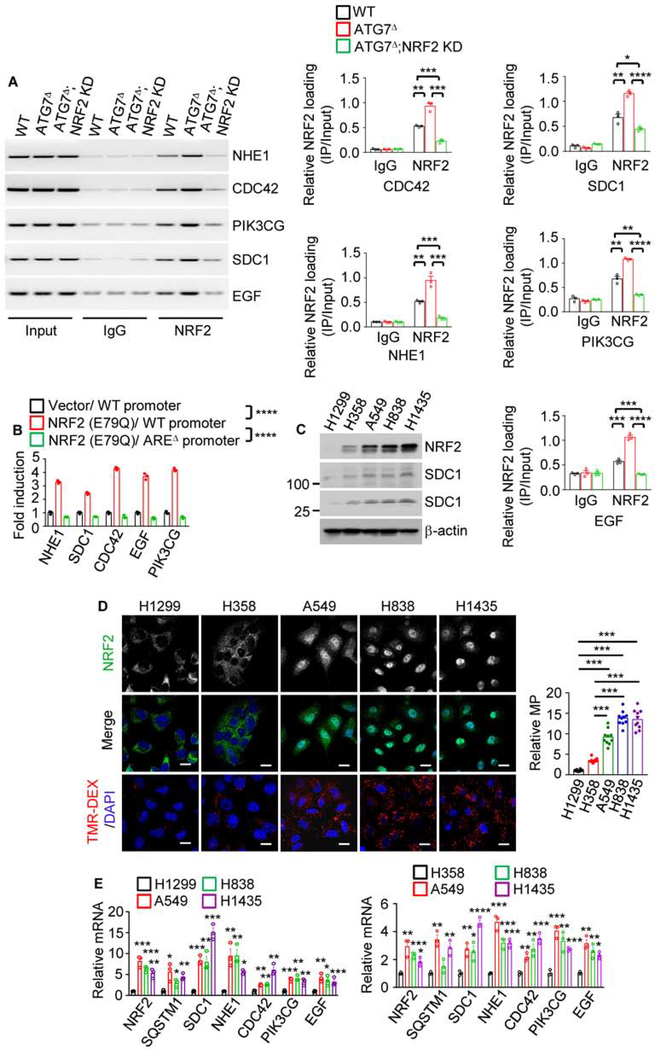

In silico analysis revealed putative NRF2 binding sites in the promoter regions of numerous MP genes (Figure S5D). Targeted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) confirmed that NRF2 was recruited to the NHE1, SDC1, CDC42, PIK3CG and EGF promoters and this was enhanced by autophagy disruption and blocked by NRF2 or p62 KD (Figures 5A, S6A and S6B). Moreover, NRF2 activated these genes’ promoters in an ARE-dependent manner (Figure 5B). Mutations and copy number variations affecting the KEAP1-NRF2 module occur in 25–30% of lung cancers (Cloer et al., 2019). Lung cancer cell lines with KEAP1 mutations (A549, H838, H1435) showed higher NRF2 expression, nuclear localization and MP-related gene expression and MP rates than KEAP1 non-mutated (H1299 and H358) cells (Figures 5C–5E). Oxidative stress induced by H2O2 and hypoxia induced by CoCl2 also increased MP activity and MP-related protein expression in WT and p62Δ MIA PaCa-2 cells but not in NRF2 KD cells (Figures S6C–S6J). These results suggest that any trigger that leads to NRF2 activation stimulates MP. Tumor hypoxia may therefore account for NRF2 activation and MP upregulation in IKKαhigh PDACs.

Figure 5. NRF2 Transcriptionally Controls MP.

(A) ChIP assays probing NRF2 recruitment to the NHE1, CDC42, PIK3CG, SDC1, and EGF promoters in WT, ATG7Δ and ATG7Δ;NRF2 KD MIA PaCa-2 cells. The image shows PCR-amplified promoter DNA fragments containing NRF2 binding sites (AREs). Quantitation is on the right.

(B) Activation of reporters controlled by WT and AREΔ promoter regions of above genes. pGL3-WT or AREΔ promoters fused to a luciferase reporter were co-transfected into MIA PaCa-2 cells +/− NRF2 expression vector and pRL-TK control reporter. The figure shows relative fold-activation by NRF2.

(C) IB analysis of NRF2 and SDC1 in lung cancer cell lines.

(D) Macropinosome and NRF2 imaging in human lung cancer cell lines. Quantitation is on the right. Scale bar, 10 μm. Relative macropinocytic uptake, mean ± SEM (n=10).

(E) qRT-PCR analysis of MP-related mRNAs in above cells.

Results in (A), (B) and (E) are mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). Statistical significance in (A), (B), (D) or (E) was determined by a 2-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S6.

Macropinocytosis is an Alternative AA and Energy Source

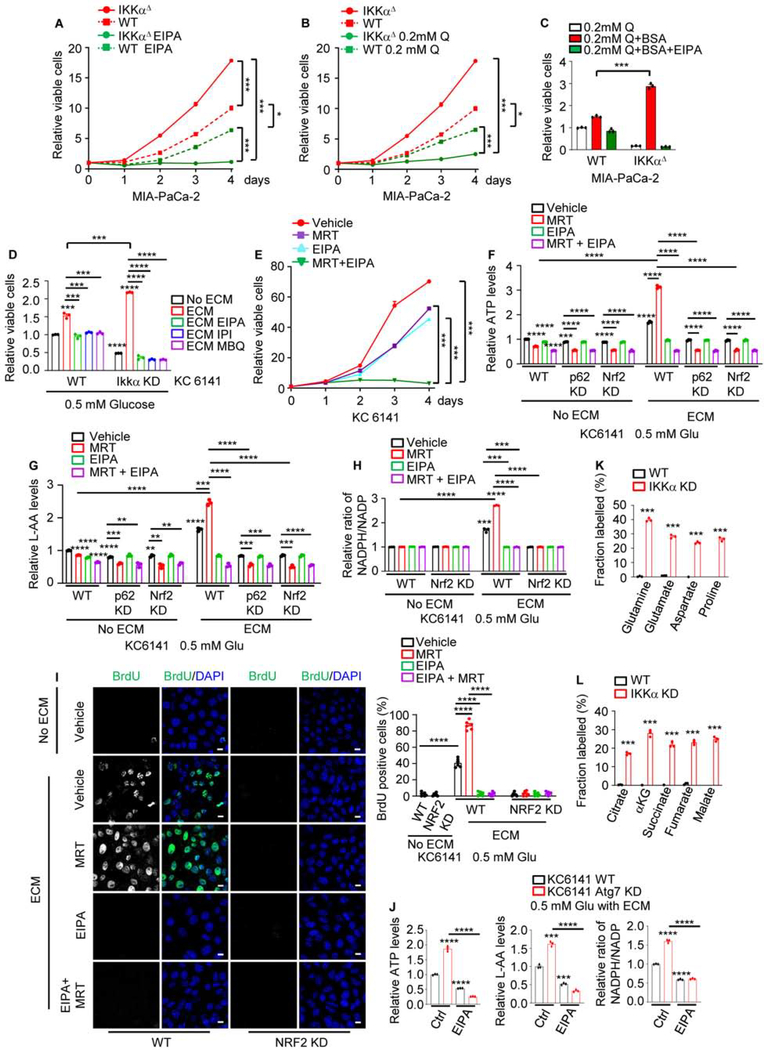

WT, IKKαΔ or ATG7Δ MIA PaCa-2 or 1444 cells were treated with EIPA. Whereas IKKα or ATG7 loss enhanced growth of MIA PaCa-2 cells, which are TP53 mutated (Nakamura et al., 2016), IKKα loss increased and ATG7 loss decreased growth of 1444 cells, which harbor functional TP53, whose expression along with p21 was decreased on IKKα loss (Figures 6A, S7A–S7C), probably due to NRF2-mediated Mdm2 induction (Todoric et al., 2017). Notably, IKKαΔ and ATG7Δ cells were highly sensitive to EIPA regardless of their TP53 status. Glutamine dependence is a hallmark of RAS-transformed cells (Gaglio et al., 2009). Congruently, culture in low glutamine slowed parental and IKKαΔ cell growth, but the effect on IKKαΔ cells was greater (Figure 6B), probably because the latter are autophagy deficient. Addition of exogenous albumin or culture on extracellular matrix (ECM) strongly enhanced the growth of nutrient-starved IKKα-deficient cells, whereas the effect on the parental cells was more modest and only albumin-supplemented or ECM-cultured IKKΔ cells were highly sensitive to inhibition or ablation of NHE1, PI3Kγ, CDC42, or NRF2 (Figures 6C, 6D and S7D). These results suggest that MP compensates for autophagy loss by enhancing extracellular protein uptake, implying that concurrent autophagy and MP blockade should completely inhibit cancer cell growth or survival. To test this prediction, primary (1444, 1305) and established human (MIA PaCa-2) and mouse (KC6141) PDAC cells were treated with the ULK1/2 inhibitor MRT68921, HCQ, EIPA or the NRF2 inhibitor ML385. Concurrent treatment with MRT68921 or HCQ plus EIPA or ML385 synergistically inhibited cell growth (Figures 6E and S7E–S7H). As expected EIPA treatment inhibited MP (Figure S7I). While HCQ synergized with EIPA or ML385, it did not synergize with MRT68921, suggesting that at 10 μM HCQ barely disrupted MP. Since EIPA may have NHE1-independent effects on cell viability (Rolver et al., 2020), we silenced NHE1 in MIA PaCa-2 cells. This rendered MIA PaCa-2 cells EIPA-insensitive but greatly increased their sensitivity to MRT68921 or ATG7 ablation (Figures S7J and S7K). Of note, IKKαlow 1305 and ATG7Δ or IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 and KC6141 cells, were very sensitive to EIPA or ML385 alone, but not to MRT68921 or HCQ (Figures S7F–S7H and S7K). IKKα overexpression rendered 1305 cells more sensitive to autophagy inhibition and resistant to MP or NRF2 inhibition (Figure S7F). SDC1 or CDC42 KD abrogated IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cell growth and MP activity (Figures S7L–S7N). We next examined how HCQ preferentially inhibits autophagy over MP. At 10–40 μM HCQ inhibited autophagic degradation to increase LC3-II, p62 and lysosomal LC3 retention, and stimulated MP as indicated by TMR-DEX and DQ-BSA co-localization and MP-related protein expression (Figures S8A and S8B). HCQ inhibited MP only at 80 μM, the dose that inhibited cell growth (Figure S8C).

Figure 6. Effect of MP and Autophagy Inhibition on PDAC Cell Growth and TCA Metabolism.

(A, B) WT and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells were cultured in complete medium +/− the NHE1 inhibitor EIPA (10.5 μM) (A) or medium containing sub-physiological glutamine (0.2 mM Q)

(B). Total viable cells were measured with a CCK-8 assay on the indicated days. Data are presented relative to day 0.

(C) WT and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells were grown in the presence of 0.2 mM Q, +/− albumin supplementation +/− EIPA. Total viable cells were measured after 3 days and data are presented relative to the WT 0.2 mM Q value.

(D) WT and IKKα KD 6141 cells were grown on plates +/− extracellular matrix (ECM) in the presence of 0.5 mM glucose (Glu) +/− EIPA, the p110γ inhibitor IPI549 (IPI, 600 nM) or the CDC42 inhibitor MBQ-167 (MBQ, 500 nM). Total viable cells were measured after 3 days and data are presented relative to the WT without ECM.

(E) KC6141 cells were incubated with vehicle, the ULK1/2 inhibitor MRT68921 (MRT), EIPA or MRT + EIPA and total viable cells were measured and presented as in (A).

(F) KC6141 cells were grown on plates +/− ECM coating in the presence of 0.5 mM Glu +/− EIPA, MRT or EIPA + MRT for 24 hrs. Total cellular ATP was measured and data were normalized to cell number and presented relative to untreated WT cells grown without ECM.

(G) Total L-amino acids (AA) in KC6141 cells that were cultured and treated as above. Data were normalized and presented as above.

(H) NADPH and NADP were measured in KC6141 cells cultured and treated as above. Data were normalized to cell number and are presented as NADPH to NADP ratio relative to the value of untreated WT cells grown without ECM.

(I) BrdU visualization and quantification in KC6141 cells grown on plates +/− ECM coating in the presence of 0.5 mM Glu and 0.5 mg/ml BrdU for 24 hrs. Scale bar, 10 μm. Mean ± SEM (n=6 fields).

(J) KC6141 cells were grown on ECM-coated plates in the presence of 0.5 mM Glu +/− EIPA for 24 hrs. Total cellular ATP, L-AA and NADPH to NADP ratio were measured and presented as in (F), (G) and (H), respectively.

(K, L) Fractional labeling (mole percent enrichment) of intracellular AA (K) and TCA cycle intermediates (L) in WT and IKKα-KD KC6141 cells cultured for 24 hrs in 0.5 mM Glu medium on ECM deposited by fibroblasts that were cultured with U-13C-glutamine for 6 days.

Results in (A)-(H) and (J) (n=3 independent experiments), (K) and (L) (n=3 per condition) are mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by a 2-tailed t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S7.

We examined how MP compensates for autophagy loss. Consistent with earlier reports (Olivares et al., 2017), KC6141 cells plated on 3H-proline-labelled ECM depended on MP for 3H-proline uptake. Whereas IKKα or ATG7 ablation enhanced 3H uptake, NHE1 or NRF2 KD or inhibition blocked it (Figures S8D and S8E). Importantly, culture on ECM increased cellular ATP and AA content, as well as NADPH to NADP ratio and BrdU incorporation, which were further elevated in MRT68921-treated or IKKα and ATG7-deficient cells and reduced in p62 or NRF2 ablated cells or after MP blockade with either the CDC42 and Rac inhibitor MBQ-167 or EIPA, which was ineffective in p62 or NRF2 KD cells (Figures 6F–6J and S8F–S8J). To address the fate of catabolized ECM proteins under nutrient-deprived conditions, we cultured parental and IKKα or ATG7 KD KC6141 cells on U-13C-glutamine labeled ECM and quantified isotope enrichment in cancer cell metabolites. Consistent with the ability of ECM, which is probably degraded by cancer cell enzymes, to support growth of nutrient-limited cells, we detected substantial ECM-derived isotope enrichment in glutamine-derived AA and TCA cycle intermediates only in IKKα or ATG7 KD cells, which was reversed by EIPA treatment (Figures 6K, 6L, and S8K). These results suggest that NRF2-activated MP compensates for autophagy loss by supporting nutrient acquisition from ECM components.

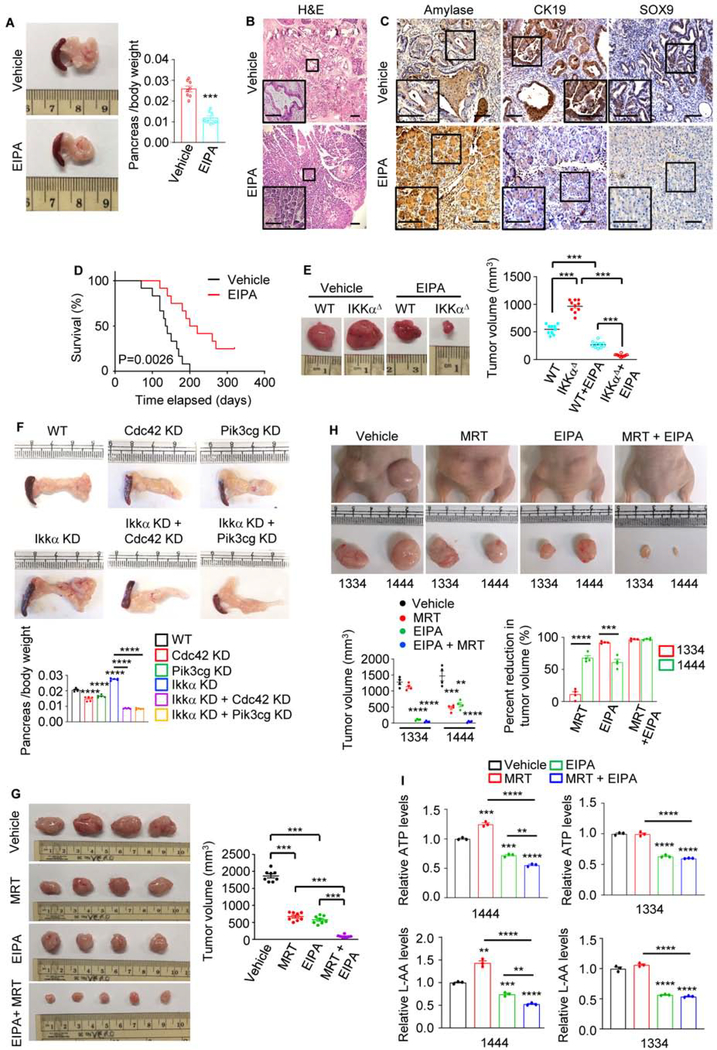

Dual Autophagy and MP Blockade Triggers Tumor Regression

We evaluated MP requirement for in vivo tumor growth using the autochthonous KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC and different allograft models. One month of EIPA treatment, initiated at 1 month of age, markedly reduced pancreatic weight (a tumor burden surrogate), inhibited ADM and advanced PanIN formation, and preserved the normal pancreatic parenchyma in KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC mice (Figures 7A and 7B), while decreasing MP (Figure S9A). IHC confirmed that EIPA prevented acinar cell loss, indicated by upregulation of amylase and downregulation of ductal (CK19) and progenitor (SOX9) markers (Figure 7C). Histological analysis revealed little residual cancer tissue in EIPA-treated mice. Importantly, EIPA treatment substantially extended KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC mouse survival (Figure 7D). Immunocompromised mice bearing parental and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 subcutaneous (s.c.) allografts were given EIPA or vehicle for 15 days when tumors were 50–100 mm3 in size. IKKαΔ tumors with low autophagic flux and high NRF2 activity were considerably larger than those formed by the parental cells but were more EIPA sensitive (Figure 7E and S9B). IKKα-deficient KC6141 cells, transplanted s.c. or orthotopically, also grew faster and formed larger tumors with lower autophagic flux and higher NRF2 activity than the parental cells, but were more sensitive to CDC42, PIK3CG, or NHE1 ablation (Figures 7F and S9C–S9F). C57BL/6 mice bearing KC6141 tumors or Nude mice bearing 1334 and 1444 allografts were treated with vehicle, MRT68921, EIPA, or MRT68921 + EIPA for 3 weeks or 15 days. Whereas MRT68921 or EIPA alone had a small effect on KC6141 or 1444 or 1334 tumor growth, the two agents together strongly inhibited tumors and decreased intracellular ATP and AA (Figures 7G–7I and S9G). Moreover, ATP and AA were reduced by EIPA alone but were insensitive to MRT68921, suggesting that MP provides an alternative AA and energy source when autophagy is inhibited. As expected, MRT68921 treatment inhibited LC3 II formation in both 1444 and 1334 tumors, although increased nuclear NRF2 and p62 accumulation were only seen in 1444 tumors (Figure S9H), consistent with results obtained with 2D cultures of these cells showing that autophagic flux is reduced in low IKKα 1334 cells (Figues S1E–S1I). Autophagic flux was increased in EIPA-treated WT or Cdc42/Pik3cg-ablated tumors, probably due to decreased cellular ATP content and increased AMPK activity (Figures S9B, S9C and S9H).

Figure 7. MP Inhibition in Autophagy-Compromised PDAC Induces Tumor Regression.

(A) Gross pancreatic morphology and weight in 8-wo KrasG12D;IkkαΔPECmice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg EIPA for 1 month. Mean ± SEM (n=8).

(B) H&E-stained pancreatic sections from above mice evaluated at the end of above experiment. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(C) IHC analysis of pancreatic sections from above mice. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC mice treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg EIPA (n=12). Significance was analyzed by log rank test.

(E) Representative images and sizes of MIA PaCa-2 tumors s.c. grown in nude mice treated with EIPA or vehicle. Mean ± SEM (n=10 mice). Note that IKKαΔ tumors removed from EIPA-treated mice mainly consisted of the Matrigel Plus plug.

(F) Gross pancreatic morphology and weight in C57BL/6 mice orthotopically transplanted with the indicated KC6141 cells. Mean ± SEM (n=5 mice).

(G) Representative images and sizes of dissected KC6141 tumors s.c. grown in C57BL/6 mice treated with vehicle, MRT, EIPA, or MRT + EIPA for 21 days. Mean ± SEM (n=8 mice).

(H) Representative images and sizes of human PDAC 1334 and 1444 tumors s.c. grown in nude mice treated as in (G) for 15 days. Mean ± SEM (n=4 mice).

(I) Total ATP and L-AA concentrations in above tumor cells. Data are presented relative to ATP and L-AA concentrations in tumor cells isolated from vehicle-treated mice.

Statistical significance in (A) or (E-I) was determined by a 2-tailed t-test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figures S8 and S9.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals an important mechanistic coupling between the autophagy and MP programs, the first enabling scavenging of nutrients from lysosome digested endogenous proteins and organelles and the second mediating fluid-phase uptake of exogenous proteins that provide AA and energy to autophagy-compromised cells. We found that autophagy blockade strongly stimulates MP, explaining why autophagy inhibition alone does not cause effective tumor starvation and regression as long as exogenous nutrients are plentiful. The master regulator linking autophagy inhibition to MP activation is NRF2. Although NRF2 maintains proteostasis in autophagy-deficient cells by inducing proteasome subunits (Towers et al., 2019), by stimulating MP it allows autophagy-inhibited cancer cells to meet their energetic demands through lysosomal, rather than proteasomal, degradation of external proteins, such as albumin or ECM components. Accordingly, concurrent autophagy and MP blockade effectively cuts off the cancer cell’s energy supply, as indicated by the large drop in cellular ATP and NADPH concentrations, leading to rapid tumor regression. In fact, MP appears to be more important for supporting tumor bioenergetics than autophagy.

Autophagy and MP are linked via the p62/SQSTM1-KEAP1-NRF2 module; inhibition of autophagy results in accumulation of the autophagy adaptor and signaling protein p62, which by sequestering KEAP1 activates NRF2. Nuclear NRF2 binds to the promoters of key MP-controlling genes, including NHE1, SDC1, CDC42 and PIK3CG, and stimulates their transcription independently of oncogenic RAS-RAF signaling. Curiously, the fly CDC42, NHE1, SDC1 and PIK3CG homologs also contain AREs and the fly NRF2 homolog CncC can stimulate MP in the fat body (E. Baehrecke, P. Velentzas, H. Su and M. Karin, unpublished data). Given the conserved nature of the p62/SQSTM1-KEAP1-NRF2 module, present in two MP-competent organisms (King and Kay, 2019), Drosophila melanogaster (Jain et al., 2015) and Dictyostelium discoideum (Mantzouranis et al., 2010; Mesquita et al., 2017), we postulate that the ability of NRF2 to activate MP may extend beyond cancer and may not be exclusive to mammals. Mutational NRF2 activation in lung cancer also stimulates MP and by analyzing 100 human PDAC specimens we found that high p62 expression and NRF2 activation strongly correlate with upregulation of MP-related proteins, further supporting NRF2’s role as a key transcriptional activator of the MP program. Human PDACs that are IKKαlow and NRF2high are autophagy-deficient and MP-elevated. But even IKKαhigh PDACs can exhibit elevated MP, as long as they are NRF2high. Our ex vivo studies suggest that NRF2 activation by oxidative stress and/or hypoxia may account for MP upregulation in such tumors. Given that KRAS stimulates NFE2L2 mRNA expression (DeNicola et al., 2011), some of the impact of RAS-RAF signaling on MP activity (Commisso et al., 2013; Ramirez et al., 2019) may be NRF2 mediated. Conversely, cancers lacking NRF2 may be incapable of switching from autophagy to MP. Although MP-high PDACs (such as 1334) may regress upon MP blockade alone, from a translational perspective it is preferable to treat such tumors (such as MP-low 1444) and other adenocarcinomas with a combination of autophagy and MP inhibitors. Although lysosomotropic drugs should inhibit both autophagy and MP, our experiments show that due to p62 accumulation, NRF2 activation and MP protein induction, such an outcome is only achieved at high HCQ concentrations that are clinically unattainable due to cardiotoxicity (Browning, 2014). Although their safety profile remains to be evaluated, more effective HCQ derivatives and new lysosomotropic agents show improved anti-tumor activity (Amaravadi et al., 2019), an effect likely due to inhibition of both autophagy and MP-related protein degradation. A more potent and selective class of autophagy inhibitors are the ULK1 inhibitors (Chaikuad et al., 2019; Egan et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2018), although even these compounds have some off-target effects, but highly selective and potent MP inhibitors are missing from the anti-cancer armamentarium. Till more effective and selective MP inhibitors are developed, clinical exploration of the treatment concept outlined by our studies may rely on inhibition of MP with approved PI3K, EGFR or MEK/ERK inhibitors. Indeed, recent studies show that combination of HCQ/CQ or ULK1 inhibitors with MEK/ERK inhibitors can result in PDAC regression (Bryant et al., 2019; Kinsey et al., 2019). Although PI3K, EGFR and MEK/ERK inhibitors have pleiotropic effects, MP inhibition may be an important component of their anti-cancer activity.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILAVILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Michael Karin (karinoffice@health.ucsd.edu).

Materials Availability

Unique materials and reagents generated in this study are available upon request from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

RNA-seq data for 177 human PDACs were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Raw data of this paper were uploaded to Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bxp3pkkhdm/draft?a=754474e6–5e0f-4455-bc8f-5ed53a8b0ada).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Culture

All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2. MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, COLO 357/FG, 1356E (primary human PDAC) and UN-KC-6141 cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco). 1444, 1305 and 1334 primary human PDAC cells, BxPC-3, AsPC-1, H1299, H358, A549, H838, and H1435 cells were maintained in RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 20% FBS (1444, 1305, 1334) or 10% FBS and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Corning). All media were supplemented with penicillin (100 mg/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml).

Mice

Female homozygous NU/NU nude mice and C57BL/6 mice were obtained at 6 weeks of age from Charles River Laboratories and The Jackson Laboratory, respectively. B6.FVB-Tg (Pdx1-cre) 6Tuv/J (termed Pdx1-Cre) and B6.129S4-Krastm4Tyj/J (LSL-KrasG12D) breeding pairs were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. IkkαF/F, p62F/F and B6.129X1-Nfe2l2tm1Ywk/J (Nrf2−/−) were provided by Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), J.M. at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (La Jolla, CA) and Dr. David A. Tuveson at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY), respectively and were previously described (Chan et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2008; Müller et al., 2013). Pdx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D, IkkαF/F, p62F/F and Nrf2−/− mice were interbred as needed to obtain the compound mutants Pdx1-Cre;LSL-KrasG12D (termed KrasG12D), Pdx1-Cre;IkkαF/F;LSL-KrasG12D (termed KrasG12D; IkkαΔPEC), Pdx1-Cre;IkkαF/F; p62F/F;LSL-KrasG12D (termed KrasG12D;IkkαΔ/p62ΔPEC), Pdx1-Cre;IkkαF/F;Nrf2−/−;LSL-KrasG12D (termed KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC;Nrf2−/−). Age- and sex-matched (except where indicated otherwise) male and female mice of each genotype were generated as littermates for use in experiments in which different genotypes were compared. For xenograft studies, female mice were randomly allocated to different treatment groups after cell injections. All mice were maintained in filter-topped cages on autoclaved food and water, and experiments were performed in accordance with UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and NIH guidelines and regulations on age and gender-matched littermates. Dr. Karin’s Animal Protocol S00218 was approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The number of mice per experiment and their age are indicated in the figure legends.

Primary Human PDAC cells and Human Specimens

PDAC patient derived xenografts (PDXs) and primary human PDAC cells were developed and provided by A.M.L. using IRB: 090401 under an IACUC approved animal protocol AM.Lowy-S09158. 1334 cells were previously described (Strnadel et al., 2017) and 1305 and 1444 cells were first generated for this project. Briefly, surgically resected pancreatic cancer tissue was directly transplanted in NSG mice for in vivo expansion of viable tumor cells. Following xenograft formation, tumors were harvested, minced, placed in 8% FBS containing RPMI with collagenase IV (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma) in a tube and incubated at 37°C for 60 min with vortex every 10 min. The dissociated suspension was passed through a 70 μm cell strainer to obtain single cells and washed with culture medium. Cell aggregates retained on top of the filter were put in a separate dish. Isolated cells and aggregates were grown in RPMI medium containing 20% FBS. Purity of the epithelial culture was assessed by flow cytometry with FITC labelled human specific EpCAM antibody staining. For selective trypsinization, cultures were washed twice with PBS, followed by 2–3 min incubation with 0.05% Trypsin/0.02% EDTA solution at 37°C. Detached cells were gently washed away with 5% serum containing medium and selective removal of fibroblasts was repeated once cells reached confluence.

IKKα, p62, NRF2, NQO1, CDC42, NHE1 and SDC1 protein expression in 100 human PDAC specimens were analyzed and are shown in Figure 4A and Figure S5B. LC3, LAMP1, ULK1 and TFE3 protein expression in 15 IKKαlow and 15 IKKαhigh human PDAC specimens are shown in Figure 4B. Pancreatic tissues were acquired from patients who were diagnosed with PDAC between June 2017 and May 2020 at The Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). All patients received a standardized pancreatic duodenectomy and 30 tumor tissues were larger than 4 cm (length or width or height). Paraffin embedded tissues were processed by pathologist after surgical operations and confirmed as tumor for further research. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital with IRB #2018–289-01. Informed consent for tissue analysis was obtained before surgery. All research was performed in compliance with government policies and the Helsinki declaration.

METHOD DETAILS

Autophagy Induction

Starvation was performed as described previously (Su et al., 2017). For starvation, cells were incubated in starvation medium (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1% BSA) for 1.5 or 2 hrs; For glucose starvation, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated in glucose-free DMEM containing 10% dialyzed FBS for 4 hrs.

Plasmids

IKKα-Flag was made by cloning human IKKα cDNA (GenBank: AF012890.1) into pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro vector using EcoRI and NotI. NRF2-Myc or NRF2-Flag was made by cloning the human NRF2 cDNA into pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro vector using NheI and NotI. Site-directed mutagenesis (IKKα LIR mutants or NRF2 E79Q) was performed using QuikChange II XL (Agilent Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For pGL3 promoter plasmids, NHE1, SDC1, CDC42, EGF, or PIK3CG promoter regions (−1000 to +100 relative to the transcriptional start site) and NHE1 (−523 ARE: 5’-TGACAGCGC-3’), SDC1 (−755 ARE: 5’-TGAGGAGC-3’), CDC42 (−911 ARE: 5’-TGACAGAAGC-3’), EGF (−20 ARE: 5’-TGACTCAGC-3’) or PIK3CG (+80 ARE: 5’-TGATAAAGC-3’) ARE deletion mutants was inserted into pGL3, made by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). lentiCRISPR v2-Blast-IKKα lentiCRISPR v2-Puro-IKKα and lentiCRISPR v2-Puro-p62 were constructed by cloning the target cDNA sequences of IKKα/CHUK and SQSTM1 into lentiCRISPR v2-Blast vector and lentiCRISPR v2-puro vector, respectively using BsmBI. pLKO.1-blast-Ikkα was made by cloning the target ιkkα/Chuk cDNA sequence into pLKO.1-blast vector using AgeI and EcoRI.

Stable Cell Line Construction

To generate lentiviral particles, HEK293T cells were transfected with the above LentiCRISPR v2 or pLKO.1 or pHAGE vectors (7.5 μg), pSPAX2 (3.75 μg) and pMD2.G (3.75 μg) or pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro vector (7.5 μg), pCMVDeltaR, (3.75 μg), and VSV-G (3.75 μg) DNAs. The next day, the medium was exchanged to fresh antibiotic-free DMEM or RPMI plus 20% FBS. After 2 days, the virus particle-containing medium were harvested and filtered and stored in −80°C. MIA PaCa-2, COLO 357/FG, 1334, BxPC3, or KC6141 cells were transduced by combining 1 ml of viral particle-containing medium with 8 μg/ml polybrene. The cells were fed 8 hrs later with fresh medium and selection was initiated 48 hrs after transduction using 1.25 mg/ml puromycin or 10 μg/ml blasticidin. IKKα KD MIA PaCa-2 cell was constructed previously (Todoric et al., 2017). For GFP-LC3-stable WT and IKKα KD or IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells, WT and IKKα KD or IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells were transduced by combining 1 ml of GFP-LC3 viral particle-containing medium with 8 μg/ml polybrene and then were selected as above.

In Vivo Treatments

To evaluate the effects of MP on tumor growth or survival in the autochthonous model, KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC mice, at 4 weeks of age, were treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg EIPA (Sigma) by i.p. injection every other day for 1 month. After that, surgically removed pancreata were weighed and used for further analysis and other mice were continued to maintain for survival. To evaluate the effects of MP on heterotopic xenografts, female homozygous BALB/c Nu/Nu nude mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in both flanks at 7 weeks of age with 106 parental and IKKαΔ MIA PaCa-2 cells or 1334 and 1444 cells mixed at a 1:1 dilution with BD Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in a total volume of 100 μl. Mice were treated with vehicle (DMSO in PBS), EIPA (7.5 mg/kg), MRT68921 (10 mg/kg) or MRT68921+EIPA for 15 days when tumors attained an average volume of 50–100 mm3. Volumes (1/2 × (width2 × length)) of s.c. tumors were calculated on the basis of measurements using digital calipers after 15 days of treatment. To evaluate the combination effects of autophagy and MP inhibition on tumor growth, C57BL/6 mice were injected s.c. at 7 weeks of age with 106 parental, Ikkα KD, Nhe1 KD or Ikkα+Nhe1 DKD KC6141 cells in a total volume of 100 μl. Mice were treated with or without vehicle, EIPA (7.5 mg/kg), MRT68921 (10 mg/kg), or EIPA + MRT68921 for 21 days when tumors attained an average volume of 50–100 mm3. Tumor volumes were calculated as above.

Orthotopic PDAC Cell Implantation

WT, Cdc42 KD, Pik3cg KD, Ikkα KD, Ikkα KD + Cdc42 KD or Ikkα KD + Pik3cg KD KC6141 were orthotopically injected in 3-month-old C57BL/6 mice as described before (Todoric et al., 2017). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg body weight, respectively). After local shaving and disinfection, a 1.5 cm long longitudinal incision was made into the left upper quadrant of abdomen. The spleen was lifted and 50 μl of cell suspension in ice-cold PBS-Matrigel mixture (equal amounts) was slowly injected into the tail of the pancreas. Successful injection was confirmed by the formation of a liquid bleb at the site of injection with minimal fluid leakage. Following surgery, mice were given buprenorphine subcutaneously at a dose of 0.05–0.1 mg/kg every 4–6 h for 12 h and then every 6–8 h for 3 additional days. Mice were analysed after 20 days. Throughout the experiment, animals were provided with food and water ad libitum and subjected to a 12-hr dark/light cycle.

Isolation of Mouse PECs

PECs were isolated from 2-month-old (MO), 12-MO KrasG12D mice and 2-MO or 3-MO KrasG12D;IKKαΔPEC, KrasG12D;IkkαΔ/p62ΔPEC, KrasG12D;IkkαΔPEC;Nrf2−/−mice using the EasySep™ Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, pancreata were collected and minced in small pieces of 1–3 mm3 with disposable scalpels followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 450 × g and 4°C. Supernatants were aspirated and discarded to remove cell fragments and blood cells. 10 mL of digestion buffer (1 mg/ml collagenase type V in DMEM/F12) were added and incubated in a 37 °C hybridization oven for 20–30 min with gentle rotation until no clumps remained. Digested tissues were pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 8 min. Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA) was used to dissociate the digested tissues to obtain mostly single cells. Then the mouse epithelial cell enrichment EasySep™ kit was used to isolate epithelial cells by sequentially adding the cocktail of Biotinylated E-Cadherin, EasySep™ Biotin Selection cocktail, EasySep™ Magnetic Nanoparticles, and then cells were incubated with the magnet. The enriched epithelial cells were counted and used for extraction of RNA or protein.

Cell Imaging

Immunostaining was performed as described (Su et al., 2017). Cells were cultured on coverslips and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature or methanol for 10 min at −20°C. After washing twice in PBS, cells were incubated in PBS containing 10% FBS to block nonspecific sites of antibody adsorption. The cells were then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (diluted 1:100) and secondary antibodies (diluted 1:500) in PBS containing 10% FBS with or without 0.1% saponin. For cell macropinosome visualization, 24 hrs after seeding, the cells were serum starved for 18 hrs. Macropinosomes were marked using a high-molecular-mass (70 KDa) TMR-DEX (Invitrogen)-uptake assay, wherein TMR-DEX was added to serum-free medium at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml for 30 min at 37°C. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were rinsed five times in cold PBS and immediately fixed in 4% PFA. For tissue macropinosome visualization (Lee et al., 2019), fresh pancreata were cut into pieces with an approximate 5-mm cuboidal shape. Tissue fragments were placed in a 24-well plate and injected with 150 μL of 10 mg/ml TMR-DEX solution. Another 250 μL of diluted TMR-DEX solution were added to the well to immerse the tissue fragment. The plate was incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. Then the tissue fragments were rinsed twice in PBS before embedding in O.C.T. compound in a prelabeled cryomold. Specimens were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C for further processing. Immunostaining was performed as described above. Images were captured using a TCS SPE Leica confocal microscope (Leica, Germany).

Proximity Ligation Assay

In vivo IKKα and LC3 interaction was detected by in situ PLA kit. Briefly, WT and IKKα KD MIA Paca-2 cells were fixed with methanol for 10 minutes at −20°C. Cells were then incubated in PBS containing 10% FBS to block nonspecific sites of antibody adsorption followed by incubation with rabbit anti-LC3 and mouse anti-IKKα (diluted 1:100), incubation with the PLA probes (anti mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated with oligo nucleotides), ligation and amplification according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured as above.

Immunoblot and Immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Proteins were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking with 5% (w/v) fat free milk, the membrane was stained with the corresponding primary antibodies followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies, and development with ECL. Immunoreactive bands were detected by automatic X-ray film processor or KwikQuant Imager.

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% NP-40, 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Then immunoprecipitation was performed using the indicated antibodies. Generally, 2 mg of antibody were added to 1 mL of cell lysate and incubated at 4°C overnight. After addition of protein A/G- magnetic beads, incubation was continued for 2 hrs, and then immune complexes were washed five times using lysis buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and the reaction was stopped with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. ChIP assay was performed as described previously (Xiao et al., 2013). Cells were lysed and sonicated on ice to generate DNA fragments with an average length of 200–800 bp. After pre-clearing, 1% of each sample was saved as input fraction. IP was performed using antibodies specifically recognizing NRF2 (CST, 12721). DNA was eluted and purified from complexes, followed by PCR amplification of the target promoters or genomic loci using primers for human NHE1: 5′-TCTCAGCCTGGGCTC-3′, and 5′-CTATCCCTATCCTGC-3′; 5′-TCCTTCCTCTTCCTACG-3′, and 5′-CAGCTGCAGCTCCT-3′; 5′-TACTGTCTCTACTTAAC-3′, and 5′-GTGAGGTTCTCTGTAT-3′; SDC1: 5′-CTTAGGAGCGGGCCG-3′ and 5′-TCGGCTCGGATTCGG-3′; 5′-TTTCTTGCAGCCCTTCCGTG-3′ and 5′-CTTCAACCGAC GGGCAAACA-3′; 5′-CAGCTTTTTGAACTGAGGCCC-3′ and 5′-CCTTAGTTTAAACAG CTGCACCC-3′; CDC42: 5′-TCGCCGGGACGTCGAGATTGCAG-3′ and 5′-CTTATCTC TACCTACACCCAGTG-3′; 5′-GGACACTGGGTGTAGGTAGAG-3′ and 5′-CCATTTTGC AGAGAAGACGGA-3′; PIK3CG: 5′-TAGGCCCCAAATGCTCTGAA-3′ and 5′-GCCA CAGTATTAGGTATCCTATTAGG-3′; 5′-TGCTCAGTCTCATACTCCTACC-3′ and 5′-AAACCTACCCAGTGTGCGTC-3′; 5′-GAGCCCCAGAAAAGCGGAAG-3′ and 5′-TATT CCGAGTCAGACCCCACA-3′; EGF: 5′-CATTCCTCTGTGCTGG-3′ and 5′-CCTGAG GCCAAATGAAG-3′ 5′-ACAGAGGCTCACTCAAG-3′ and 5′-AAGGAAGAACTGATG-3′ PDGFB: 5′-TGGCCTTGGCTCTGG-3′ and 5′-GACGCGGGAGCTGG-3′; 5′-AACCCGG GGGCTGAGGGAGATAG-3′ and 5′-AGCTGGGTCCGAGTCTCCTCC-3′; SNX5: 5′-CAG TTAGAGGCAGGGAGTACC-3′ and 5′-GACACTCTCCCAGCAAGACG-3′; 5′-TCCTGAG CTGCCTGCAAATG-3′ and 5′-GCTCTGTCCAAACATGTCGAA-3′; PAK1: 5′-GCAGGTA CCTGTAGTC-3′ and 5′-GAAGAATGCTAGGTG-3′; 5′-GTACCTAGTACATAATAG-3′ and 5′-GCCTCCCAAGTAGCTG-3′.

Luciferase Assay

The Dual Luciferase assay was performed as described previously (Todoric et al., 2017). pGL3-NHE1, pGL3-SDC1, pGL3-PIK3CG, pGL3-CDC42 or pGL3-EGF WT or AREΔ reporter plasmids and pRL-TK plasmids (Promega) were co-transfected with or without NRF2(E79Q) expression vector into MIA PaCa-2 cells. 24 h after transfection, the cells were seeded to a 96-well plate. The activity of both Firefly and Renilla luciferases was determined 48 h after transfection with the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega Promega E1910) with a luminometer FilterMax F5 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Results are expressed as fold change and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA and DNA were extracted using an All Prep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed using a Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed as described (Todoric et al., 2017). Relative expression levels of target genes were normalized against the level of 18s rRNA expression. Fold difference (as relative mRNA expression) was calculated by the comparative CT method (2Ct(18s rRNA–gene of interest)). Primers obtained from the NIH Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC=BlastHome) were as follows: Pik3ca F: 5′-GGACTGTGTGGGTCTCATCG-3′; Pik3ca R: 5′-TCTCGCCCTTGTTC TTGTCC-3′; Pik3cg F: 5′-CTCTGGACCTGTGCCTTCTG-3′; Pik3cg R: 5′-ATCTTTGAATGCCCCCGTGT-3′; Rac1 F: 5′-CTACCCGCAGACAGACGTG-3′; Rac1 R: 5′-AGATCAAGCTTCGTCCCCAC-3′; Cdc42 F: 5′-GAGACTGCTGAAAAGCTGGCG-3′; Cdc42 R: 5′-GGCTCTTCTTCGGTTCTGGAGG-3′; Pak1 F: 5′-CTTCCGGGACTTTCTGCAATG-3′; Pak1 R: 5′-GTCAGGCTAGAGAGGGGC TT-3′; Nhe1 F: 5′-TCATGAAGATAGGTTTCCATGTGAT-3′; Nhe1 R: 5′-CGTCTGATTG CAGGAAGGGG-3′; Arf6 F: 5′- CGTGGAGACGGTGACTTACA-3′; Arf6 R: 5′-GGTGTAG TAATGCCGCCAGA-3′; Sdc1 F: 5′-TCTGGCTCTGGCTCTGCG-3′; Sdc1 R: 5′-GCCGTGA CAAAGTATCTGGC-3′; Snx5 F: 5′-ACTGACAGAGCTCCTCCGAT-3′; Snx5 R: 5′-TTAACC GGGCCTTGTCCAAA-3′; Rab5 F: 5′-ACAGCTGGTCAAGAACGGTA-3′; Rab5 R: 5′-GCTCTCGCAAAGGATTCCTCA-3′; Rab7 F: 5′-GGAGCGGACTTTCTGACCAA-3′; Rab7 R: 5′-GCCACACCAAGAGACTGGAA-3′; Sept6 F: 5′-GCTTCAACATCCTGTGCGTG-3′; Sept6 R: 5′-GTTTCAACCCCACGTTGCTC-3′; Egfr F: 5′-ACCTCTCCCGGTCAGAGATG-3′; Egfr R: 5′-CTTGTGCCTTGGCAGACTTTC-3′; Egf F: 5′-TTCTCACAAGGAAAGAGCATCTC-3′; Egf R: 5′-GTCCTGTCCCGTTAAGGAAAAC-3′; Epgn F: 5′-CTCCTAGCACAGCACAGC AG-3′; Epgn R: 5′-GCTTCAGCTCATGGTGGAAT-3′; Areg F: 5′-ACAGCGAGGATGACA AGGAC-3′; Areg R: 5′-GATGCCAATAGCTGCGAGGA-3′; Hbegf F: 5′-CTCTTGCAAA TGCCTCCCTG-3′; Hbegf R: 5′-CAAGAAGACAGACGGACGACA-3′; Pdgfa F: 5′-CAGTGT CAAGGTGGCCAAAG-3′; Pdgfa R: 5′-CACCTCACATCTGTCTCCTC-3′; Pdgfb F: 5′-CTGCTACCTGCGTCTGGTC-3′; Pdgfb R: 5′-GAGTGTGCTCGGGTCATGTT-3′; m18s F: 5′-AGCCCCTGCCCTTTGTACACA-3′; m18s R: 5′-CGATCCGAGGGCCTCACTA-3′; PIK3CA F: 5′-GGTTTGGCCTGCTTTTGGAG-3′; PIK3CA R: 5′-CCATTGCCTCGACTTGCCTA-3′; PIK3CG F: 5′-AGGAGGTGCTGTGGAATGTG-3′; PIK3CG R: 5′-TTGGACTCAGAACT GGGGGA-3′; RAC1 F: 5′-AAAACCGGTGAATCTGGGCT-3′; RAC1 R: 5′-AAGAACACATC TGTTTGCGGA-3′; CDC42 F: 5′-ACGACCGCTGAGTTATCCAC-3′; CDC42 R: 5′-TCTCA GGCACCCACTTTTCT-3′; PAK1 F: 5′-GTCACAGGGGAGTTTACGGG-3′; PAK1 R: 5′-GCCTGCGGGTTTTTCTTCTG-3′; NHE1 F: 5′-TTCCCTTCCTTACTCGTGGTG-3′; NHE1 R: 5′-AATCGAGCGTTCTCGTGGT-3′; ARF6 F: 5′-CAACGTGGAGACGGTGACTT-3′; ARF6 R: 5′-TCCCAGTGTAGTAATGCCGC-3′; PSD4 F: 5′-CAACCTTGGGCCTCTCTCAG-3′; PSD4 R: 5′-GTCCACCCTCCCTCTCATCT-3′; SDC1 F: 5′-CAGGAAAGAGGTGCTGGGAG-3′; SDC1 R: 5′-GCTGCCTTCGTCCTTCTTCT-3′; SNX5 F: 5′-ACTGGGAGAAG GTGAAGGGT-3′; SNX5 R: 5′-ACAGGGTGAGAAGAAAGCCG-3′; RAB5 F: 5′-TACTTCTGGGAGAGTC CGCT-3′; RAB5 R: 5′-TTTGGGTTAGAAAAGCAGCCC-3′; RAB7 F: 5′-GGTTCCAGTCTCT CGGTGTG-3′; RAB7 R: 5′-GAATGTGTTGGGGGCAGTCA-3′; SEPT2 F: 5′-AGCCCTTAGA TGTGGCGTTT-3′; SEPT2 R: 5′-TCCTTTTCTTCAGCCGCTCC-3′; SEPT6 F: 5′-GGCTTT GGGGACCAGATCAA-3′; SEPT6 R: 5′-TCGGGAGTCATGGTAGGTGT-3′; EGFR F: 5′-CGCAGTTGGGCACTTTTGAA-3′; EGFR R: 5′-GGACATAACCAGCCACC TCC-3′; EGF F: 5′-GAGATGTGAGGAGTCGCAGG-3′; EGF R: 5′-GGTTGCATTG ACCCATCTGC-3′; EPGN F: 5′-CCCAGCAAGCTGACAACATAG-3′; EPGN R: 5′-TTCAATTTTAGACACCTTT CTCCAG-3′; AREG F: 5′-TCGCTCTTGATACTCGGCTC-3′; AREG R: 5′-AATGGTTCACGC TTCCCAGA-3′; HBEGF F: 5′-GGTGGTGCTGAAGCTCTTTC-3′; HBEGF R: 5′-AGCTGGT CCGTGGATACAGT-3′; EREG F: 5′-ACGTGTGGCTCAAGTGTCAA-3′; EREG R: 5′-AGTGTTCACATCGGACACCA-3′; BTC F: 5′-CCTTGCCCTGGGTCTAGTG-3′; BTC R: 5′-CCACAGAGGAGGCCATTAGT-3′; TGFA F: 5′-CCTGTTCGCTCTGGGTATTGT-3′; TGFA R: 5′-GTGGGAATCTGGGCAGTCAT-3′; PDGFRA F: 5′-TGTGGAGAATCTGCTGCCTG-3′; PDGFRA R: 5′-CCTCCCAGTCCTTCAGCTTG-3′; PDGFRB F: 5′-TGGCCCTCAAAGGC GAG-3′; PDGFRB R: 5′-GAGCAGGTCAGAACGAAGGT-3′; PDGFA F: 5′-CACTAAG CATGTGCCCGAGA-3′; PDGFA R: 5′-AGAT CAGGAAGTTGGCGGAC-3′; PDGFB F: 5′-TCCTGTCTCTCTGCTGCTAC-3′; PDGFB R: 5′-ATCAAAGGAGCGGATCGAGT-3′; PDGFC F: 5′-GACTCAGGCGGAATCCAACC-3′; PDGFC R: 5′-ATGAGGAAACCTTGG GCTGT-3′; PDGFD F: 5′-GCACCGGCTCATCTTTGTCT-3′; PDGFD R: 5′-GATTGCT CTCATCTCGCCTG-3′; CHUK F: 5′-GCTGCCCCCGACTTCAGCAG-3′; CHUK R: 5′-ACTATTGCCCTGTTCCTCATTTGCCTCA-3′; NQO1 F: 5′-CTGGAGTGCAGTGGTG TGAT C-3′; NQO1 R: 5′-AGGCAGGAGAATTGCTGGAAC-3′; h18s F: 5′-GGACACGGACAGG ATTGACAG-3′; h18s R: 5′-CAACTAAGAACGGCCATGCAC-3′; ACTB F: 5′-TCACCCA CACTGTGCCCATCTAC-3′; ACTB R: 5′-GGAACCGCTCATTGCCAATG-3′.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Preparation

Skin fibroblasts were seeded on 6/12/96-well plates. One day after plating, cells were switched into DMEM (with pyruvate) with 10% dialysed FBS supplemented with or without 500 μM 3H-proline and 100 μM Vitamin C. Cells were cultured for 6 days with media renewal every 24 h. After six days, skin fibroblasts were removed by washing in 1 ml or 500 μl or 100 μl per well PBS with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 20 mM NH4OH. ECM was washed five times with PBS before plating KC6141 cells. The following day, KC6141 cells were switched into the indicated medium for 24 or 72 hrs.

Metabolite Extraction

Cells grown on 12-well plate were rinsed with 1 ml cold saline and quenched with 250 μl cold methanol. 100 μl of cold water containing 1 μg norvaline was added, cell lysate was collected, and 250 μl of chloroform was added to each sample. After extraction the aqueous phase was collected and evaporated under nitrogen.

Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis

Dried polar metabolites were dissolved in 2% methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine (Thermo) and held at 37 °C for 1.5 h. After dissolution and reaction, tertbutyldimethylsilyl derivatization was initiated by adding 30 ml N-methyl-N-(tertbutyldimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide + 1% tertbutyldimethylchlorosilane (Regis) and incubating at 37°C for 1 h. GC/MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 6890 GC equipped with a 30m DB-35MS capillary column connected to an Agilent 5975B MS operating under electron impact ionization at 70 eV. One microlitre of sample was injected in splitless mode at 270°C, using helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. For measurement of amino acids, the GC oven temperature was held at 100°C for 3min and increased to 300°C at 3.5°C/min. The MS source and quadrupole were held at 23°C and 150°C, respectively, and the detector was run in scanning mode, recording ion abundance in the range of 100–605 m/z. Mole percent enrichments of stable isotopes in metabolite pools were determined by integrating the appropriate ion fragments (Cordes and Metallo, 2019) and correcting for natural isotope abundance as previously described (Kumar et al., 2020).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined with Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK-8 assay kit, Glpbio). Cells were plated in 96-well plates coated with or without ECM at a density of 3000 cells (MIA PaCa-2, 1444, 1305, COLO 357/FG) or 1500 cells (KC6141) per well and incubated overnight prior to treatment. EIPA (10.5 μM), IPI549 (600 nM), MBQ-167 (500 nM), MRT68921 (600 nM) or erlotinib (2 μM, Sigma), ML385 (10 μM, Sigma), HCQ (10 μM or 80 μM) or their combinations were added to the wells for 24, 72 or 96 hrs. Next, 10 μL of CCK-8 was added to each well. The optical density was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (FilterMax F5, Molecular Devices, USA) at day 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4. For glutamine-deprivation assays, cells in 96-well plates were rinsed briefly in PBS and incubated in the 0.2 mM glutamine. Glutamine-free DMEM medium was supplemented with 0.2 mM glutamine in the presence of 10% dialyzed FBS and 25 mM HEPES. For glucose-deprivation assays, cells in 96-well plates were rinsed briefly in PBS and incubated in the 0.5 mM glucose. Glucose-free DMEM medium was supplemented with 0.5 mM glucose in the presence of 10% dialyzed FBS and 25 mM HEPES. For some conditions, the medium was supplemented with a final concentration of 2% BSA (Fraction V, fatty-acid-, nuclease and protease-free, Calbiochem). For all experiments, media were replaced every 24 hrs. Viable cell counts were obtained using CCK-8 assay described as above.

ATP Detection Assay

For cell samples, intracellular ATP level was determined with luminescence ATP detection assay system (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, KC6141 cells were grown on 96-well plates coated with or without ECM in the presence of 100 μl 0.5 mM glucose medium with or without EIPA (10.5 μM), MBQ-167 (500 nM), MRT68921 (600 nM) or their combinations for 24 hrs. 50 μl mammalian cell lysis solution was added and shaken for 5 minutes. Next, 50 μl substrate solution was added and shaken for 5 minutes. Finally, plate was adapted in dark for 10 minutes and luminescence was measured.

For tissue samples, 10 mg tissues were washed in cold PBS. Then tissues were homogenized in 100 μL of ATP assay buffer with a Dounce homogenizer on ice with 10–15 passes. Samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 4°C at 13,000g to remove any insoluble material. Supernatants were collected and transferred to a new tube and kept on ice. Then ATP level was determined with ATP Assay Kit (Abcam) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

L-Amino Acid Assay

Total amount of free L-amino acids (except for glycine) were measured by L-Amino Acid Assay Kit (Colorimetric) (antibodies) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, KC6141 cells were grown on 6-well plates coated with or without ECM and treated as above. The cells were resuspended at 106 cells/mL 1X Assay Buffer and were homogenized on ice and then centrifuged to remove debris. 50 μL of each L-alanine standard or cell lysis was added into wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. Then 50 μL of Reaction Mix was added to each well. The well contents were mixed thoroughly and incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C protected from light. The plate was read with a spectrophotometric microplate reader in the 540–570 nm range. The concentration of L-amino acids was calculated within samples by comparing the sample OD to the standard curve. For tissue samples, 10 mg tissues were homogenized in cold PBS and centrifuged at 10000g for 10 minutes at 4 °C to remove insoluble material. The supernatants were sequentially diluted in 1X Assay Buffer and transferred to 96-well microtiter plate. The concentration of L-amino acids was measured as above.

NADPH/NADP Measurement

NADPH and NADP measurement was performed using NADP/NADPH-Glo™ Assays (Promega #G9081) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, KC6141 cells were grown on 6-well plates coated with ECM and treated as above. Then the cells were resuspended at 106 cells/mL 50μl of PBS and 50μl of base solution with 1% DTAB and transferred to 96-well plates. The plate was briefly mixed to ensure homogeneity and cell lysis. 50μl of each sample was removed to an empty well for acid treatment. 25μl per well of 0.4N HCl was added into these samples. All samples were incubated for 15 minutes at 60°C and then equilibrated for 10 minutes at room temperature. 25μl of 0.5M Trizma® base was added into each well of acid-treated cells to neutralize the acid. 50μl of HCl/Trizma® solution was added to each well containing base-treated samples. Then 100μl of NADP/NADPH-Glo™ Detection Reagent was added into each well and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Luminescence was recorded using a luminometer.

Immunohistochemistry

Pancreata were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and embedded in paraffin. 5 mm sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For IHC, after xylene de-paraffinization and rehydration through graded ethanol antigen retrieval was performed for 20 min at 100°C with 0.1% sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Following quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2 and blocking of non-specific binding with 5% bovine serum albumin buffer, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the appropriate primary antibodies followed by incubation with 1:200 biotinylated secondary antibodies for 30 min and 1:500 streptavidin-HRP for 30 min. Bound peroxidase was visualized by 1–10 min incubation in a 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (Vector Laboratories, SK-4100). Slides were photographed on an upright light/fluorescent Imager A2 microscope with AxioVision Release 4.5 software (Zeiss, Germany).

IHC Scoring

A modified labeling score (H score) which is calculated by using percentage of positive stained cancer cells and their intensity per tissue core as before (Todoric et al., 2017). Intensity of stain was determined by dominant staining and was divided into four categories (0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong). By multiplying staining intensity and percentage of positive stained tumor cells ranged from 0 to 100%, H score got a range of 0–300. Cores with overall scores of 0–5, 5–100, 101–200, 201–300 were classified as negative, weak, intermediate and strong expression level. Complete absence of staining or less than 5% of cancer cells stained faintly were thought to be negative (H-score, 0–5). Negative and weak were viewed as low expression level and intermediate and strong were viewed as high expression level. For cases with tumors with two satisfactory cores, the results were averaged; for cases with tumors with one poor-quality spot, results were based on the interpretable core. Based on this evaluation system, Spearman correlation analysis or Chi-square test was used to estimate the association between IKKα, p62, NRF2, and MP-related proteins staining intensities. The number of evaluated cases for each different staining in PDAC tissues and the scoring summary is indicated (Figure S5B).

Quantification and Statistics

To quantify LC3 puncta or LC3-LAMP1 co-localization, a total of 30 cells were recorded and analyzed using the LAS X measurement program on the TCS SPE Leica. Macropinosomes were quantified by using the ‘Analyze Particles’ feature in Image J (National Institutes of Health). LC3 puncta in human PDAC specimens or macropinocytic uptake index (Commisso et al., 2014) was computed by determining the total LC3 puncta or macropinosome area in relation to the cytoplasmic area or total cell area for each field and then by determining the average across all the fields (at least 6 fields). These measurements were done on randomly-selected fields of view. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was performed for statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Scatter plots in Figure S5A were generated by nonparametric Spearman correlation analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by log rank test. Statistical correlation between p62 or NRF2 and MP-related mRNA expression in human PDAC was determined by nonparametric spearman correlation analysis. (****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-p62 polyclonal antibody | Progen | Cat# GP62-C; RRID:AB_2687531 |

| Rabbit anti-NRF2polyclonal antibody | ABclonal | Cat#A11159; RRID:AB_2758436 |

| Rabbit anti-NRF2 monoclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab62352; RRID:AB_944418 |

| Rabbit anti-NRF2 monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12721; RRID:AB_2715528 |

| Rabbit anti NQO1 monoclonalantibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#62262; RRID:AB_2799623 |

| Mouse anti-NQO1 monoclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat# ab28947; RRID: AB_881738 |

| Mouse anti-IKKα monoclonal antibody | Invitrogen | Cat#MA5–16157;RRID: AB_2537676 |

| Rabbit anti-IKKα monoclonal antibody | GeneTex | Cat#GTX62710; RRID:AB_10621122 |

| Mouse anti-actin monoclonal antibody | Sigma | Cat#A4700; RRID: AB_476730 |

| Rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibody | Molecular Probes | Cat#A-11122; RRID:AB_221569 |

| Mouse anti-LAMP-1 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#:sc-20011; RRID:AB_626853 |

| Rabbit anti-LAMP-1 monoclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab108597 |

| Chicken anti-GFP/YFP/CFPpolyclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab13970; RRID:AB_300798 |

| Mouse anti-VAMP-8 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-166820; RRID:AB_2212959 |

| Mouse anti-Flag monoclonal antibody | Sigma | Cat#F3165; RRID: AB_259529 |

| Rabbit anti-Flag polyclonalantibody | Sigma | Cat#F7425; RRID:AB_439687 |

| Rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody | Roche | Cat#1867431; RRID:AB_390919 |

| Rabbit anti-STX17 polyclonal antibody | Proteintech | Cat#17815–1-AP; RRID:AB_2255542 |

| Rabbit anti-STX17 polyclonal antibody | Genetex | Cat#GTX130212 |

| Mouse anti-STX17 monoclonal antibody | CBXS | Cat#CAMAB-S0951-CQ |

| Mouse anti-LC3 monoclonal antibody | Cosmo Bio | Cat#CTB-LC3–2-IC |

| Rabbit anti-LC3B polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2775; RRID:AB_915950 |

| Rabbit anti-LC3 polyclonal antibody | CiteAb | Cat#AP1802a; RRID: AB_2137695 |

| Rabbit anti-LC3B polyclonal antibody | NOVUS | Cat#NB100–2220; RRID: AB_10003146 |

| Rabbit anti-E-Cadherin monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3195; RRID: AB_2291471 |

| Rabbit anti-CD138 antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#36–2900; RRID: AB_2533248 |

| Mouse anti-NHE-1 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-136239; RRID: AB_2191254 |

| Rabbit anti-PI3 Kinase p110α monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4249; RRID: AB_2165248 |

| Rabbit anti-PI3 Kinase p110γ monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5405; RRID: AB_915950 |

| Rabbit anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4267; RRID: AB_2246311 |

| Rabbit anti-CDC42 polyclonal antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#PA1–092; RRID: AB_2539858 |

| Mouse anti-SNX5 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-515215 |

| Mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat#Ab-32; RRID: AB_303599 |

| Mouse anti-HSP90 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-13119; RRID:AB_675659 |

| Rabbit anti-α-Amylase polyclonal antibody | Sigma | Cat#A8273; RRID: AB_258380 |

| Goat anti-cytokeratin 19 polyclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-33111; RRID: AB_2234419 |

| Rabbit anti-SOX9 Polyclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-20095; RRID: AB_661282 |

| Mouse anti-cytokeratin 18 monoclonal antibody | GeneTex | Cat#GTX105624; RRID:AB_1950645 |

| Rabbit anti-ERK polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9102; RRID: AB_330744 |

| Rabbit anti-pERK polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9101S; RRID:AB_331646 |

| Rabbit anti-K-Ras polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#53270S |

| Mouse anti-K-Ras monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-30; RRID:AB_627865 |

| Rabbit anti-ULK1 monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8054; RRID:AB_11178668 |

| Rabbit anti-ULK1 polyclonal antibody | Proteintech | Cat#20986–1-AP |

| Rabbit anti-pULK1(Ser317) polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#37762 |

| Rabbit anti-AMPK monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5832; RRID: AB_10624867 |

| Rabbit anti-pAMPK monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2535; RRID: AB_331250 |

| Rabbit anti-TFE3 monoclonal antibody | Abcam | Cat#ab179804 |

| Rabbit anti-p53 polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9282; RRID: AB_331476 |

| Rabbit anti-p21 monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2947; RRID:AB_823586 |

| Rabbit anti-ATG7 monoclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8558; RRID:AB_10831194 |

| Rabbit anti-phospho Akt (Ser473) polyclonal antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9271; RRID:AB_329825 |

| Mouse anti-Akt1/2/3 monoclonal antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-81434; RRID:AB_1118808 |

| Rabbit anti-Histone H3 polyclonal antibody | ABclonal | Cat#A2348; RRID: AB_2631273 |

| Mouse HRP goat anti-chicken IgY antibody | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-2428; RRID:AB_650514 |

| HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7074; RRID: AB_2099233 |

| HRP horse anti-mouse IgG antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7076; RRID: AB_330924 |

| HRP streptavidin | Pharmingen | Cat#554066 |

| Biotin goat anti-mouse IgG | Pharmingen | Cat#553999; RRID:AB_395196 |

| Biotin goat anti-rabbit IgG | Pharmingen | Cat#550338; RRID: AB_393618 |

| Biotin mouse anti-goat IgG | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-2489; RRID: AB_628488 |

| Goat anti-Chicken IgY (H+L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11039; RRID:AB_ 2534096 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32731; RRID:AB_2633280 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 594 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32744; RRID:AB_2762826 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32723; RRID:AB_2633275 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 594 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32740; RRID:AB_2762824 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11031; RRID:AB_144696 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32733; RRID:AB_2633282 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Chemically competent One shot Stbl3 | Invitrogen | Cat# C737303 |

| NEB® Stable Competent E. coli | BioLabs | Cat# C3040I |

| MAX Efficiency™ DH5α Competent Cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 18258012 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human PDAC specimens | The Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School | N/A |

| Patient-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts | Moores Cancer CenterUniversity of California San Diego | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Dextran, Tetramethylrhodamine, 70,000 MW, Lysine Fixable | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# D1818 |

| Trametinib | MCE | Cat# HY-10999 |

| 5-(N-Ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA) | Sigma | Cat# A3085 |

| MRT68921 dihydrochloride | MCE | Cat# HY-100006A |

| ML385 | MCE | Cat# HY-100523 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Sigma | Cat# H0915 |

| DQ™ Green BSA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# D12050 |

| Polybrene | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-134220 |

| Puromycin (solution) | InvivoGen | Cat# ant-pr-1 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# L3000015 |

| Blasticidin S HCl solution | Santa Cruz | Cat# 3513–03–9 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| 177 human PDAC RNA-seq Data | TCGA | https://gdac.broadinstitute.org/ |

| Raw data of this paper | Mendeley Data | https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bxp3pkkhdm/draft?a=754474e6-5e0f-4455-bc8f-5ed53a8b0ada |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Quick Change II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 200521 |

| Super Script VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit Scientific | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11754050 |

| Dual Glo Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat# E2920 |

| Duolink™ In Situ Red Starter Kit Mouse/Rabbit | Sigma | Cat# DUO92101 |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | Glpbio | GK10001 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: MIA PaCa-2 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1420; RRID: CVCL_0428 |

| Human: PANC-1 | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1469; RRID:CVCL_0480 |

| Human: COLO 357/FG | Andrew Lowy (Morgan et al., 1980) | RRID:CVCL_8196 |