Abstract

Persistent comorbidities occur in patients who initially recover from acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). ‘Long COVID’ involves the central nervous system (CNS), resulting in neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs, including cognitive impairment or ‘brain fog’ and chronic fatigue syndrome. There are similarities in these persistent complications between SARS-CoV-2 and the Ebola, Zika, and influenza A viruses. Normal CNS neuronal mitochondrial function requires high oxygen levels for oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production. Recent studies have shown that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can hijack mitochondrial function. Persistent changes in cognitive functioning have also been reported with other viral infections. SARS-CoV-2 infection may result in long-term effects on immune processes within the CNS by causing microglial dysfunction. This short opinion aims to discuss the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of long-term neuropsychiatric COVID-19 involves microglia, mitochondria, and persistent neuroinflammation.

Keywords: Editorial, Central Nervous System, Inflammation Mediators, Neuropsychiatry, Mitochondria, Microglia, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, COVID-19, Cognitive Dysfunction

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been a pandemic disease for more than a year. Worldwide, medical practitioners have become acutely aware of the clinical presentation of long-term comorbidities following recovery from COVID-19. Long-term COVID-19, or ‘long COVID,’ can include compromise to integrative neurological functions that regulate key cognitive and affective processes in the CNS, resulting in neuropsychiatric disease [1]. Based on recent empirical data, SARS-CoV-2 infection may functionally divert the bioenergetics capacity of infected cells to support viral replication [1–3]. It is possible that mitochondrial targeting by the virus may be the substrate for the emergence of cognitive impairment or ‘brain fog’ [3].

Constitutively high levels of mitochondrial oxygen consumption, oxidative phosphorylation, and ATP production are required for normal neuronal function within the CNS. Recent research has shown that operational hijacking of mitochondria by intracellular SARS-CoV-2 RNA and protein components also occurs during infection with the Ebola, Zika, and influenza A viruses [4]. Viral targeting of mitochondria may be an evolutionarily conserved adaptive process for viruses and bacteria as mitochondria are organelles with a prokaryotic origin [5,6]. Therefore, this short review aims to discuss the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of long-term neuropsychiatric COVID-19 involves microglia, mitochondria, and persistent neuroinflammation.

A Hypothesis for the Pathogenesis of Long-term Neuropsychiatric COVID-19

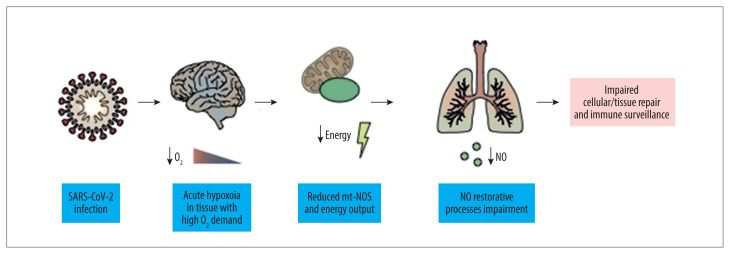

Viral targeting of neural tissues is a complex process, and SARS-CoV-2 may also initiate dysautonomia and alter temperature, blood pressure, cardiac function and rhythm, and gastrointestinal motility [7]. The effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection may manifest as altered stress responses. In 2020, Goldstein proposed that chronic activation of the extended autonomic system (EAS), which includes the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems, is associated with an increased risk of developing ‘long COVID’ [8]. Long-term, viral-induced disease pathogenesis is associated with conditions that include myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) [3,9–11]. Acute cognitive impairment, similar to ‘brain fog,’ may also occur in Lyme disease and infection with influenza, West Nile virus, and Ebola virus [10,12–16]. These findings raise the possibility that the neuropsychiatric sequelae of some infectious diseases may have similar pathogenesis. Accordingly, a chronic state of pro-inflammation within CNS structures may be perpetuated by chronic activation of populations of circulating T and B lymphocytes by cross-reacting viral epitopes ultimately targeting brain microglia. We therefore propose that integrative studies employing bioinformatics analyses to identify small peptides with homologous amino acid sequences across classes of human pathogenic viruses linked to state of the art flow cytometry analyses of activated T and B lymphocytes will provide validating data sets in support of these contentions. However, it is still unclear whether the infectious organism persists in the affected tissues or whether the infection alters the tissue to evade the immune response. A reasonable assumption is that the persistent long-term pathological consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection involving the CNS arise from an immune response resulting in neuroinflammation with dysfunction of mitochondria and microglia (Figure 1) [17–19].

Figure 1. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection, blood-borne competent mitochondria provide a novel source of restorative ATP and constitutive nitric oxide synthase (cNOS) to stimulate the release of nitric oxide (NO), which is anti-inflammatory.

During acute stress from viral infection, proinflammatory responses partially mediate autoregulatory homeostatic mechanisms and maintain immune surveillance against infection [18]. Changes in the production of proinflammatory mediators commonly occur in autoimmune diseases and comorbid syndromes [18]. Cell-free mitochondria with significant bioenergetics capacity are present in the peripheral circulation [1]. Blood-borne competent mitochondria may represent a novel source of restorative ATP. Also, cNOS activation results in enhanced production, release, and intra-mitochondrial recycling of NO, which promote anti-inflammatory processes, to effectively modulate cell damage following viral infection [19].

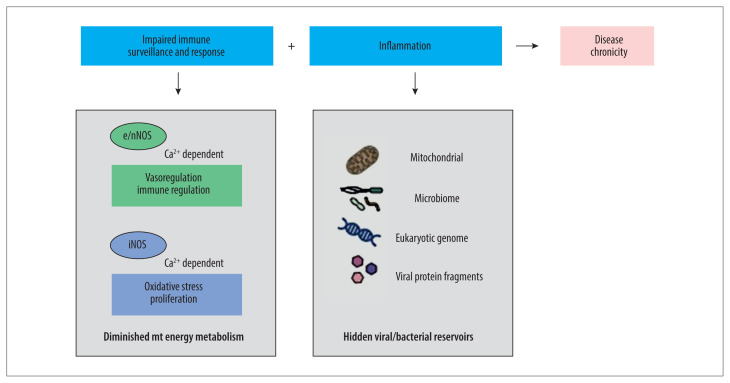

In 2020, Boziki et al. reviewed the immunopathology of COVID-19 infection of the CNS [20]. SARS-CoV-2 infection exacerbates demyelinating CNS disorders, including multiple sclerosis [20]. Possibly, that this long-term effect of SARS-CoV-2 has gone unrecognized [20]. It is also possible that cognitive dysfunction may be a common but unrecognized long-term effect of several viral infections [2,13,19]. Given the common presenting clinical features of some viral infections, we hypothesize that dysfunctional chronic inflammatory conditions may result in long-term comorbid neuropsychiatric syndromes and other syndromes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The persistent presence and magnitude of chronic symptoms linked to viral infections, including ‘long COVID’ may occur by altering the normal healing process.

There are empirically determined normal regulatory equilibria between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system. A model of behaviorally-mediated regulatory effects on whole-body metabolic processes is intrinsically broad-based and multifaceted with the integration of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and the central nervous system (CNS) [18]. Regulatory molecules, including nitric oxide (NO) are multifaceted and stereoselective, and associated with conformational matching. Acute proinflammatory events have the potential to lead to chronic disruption of regulatory molecules. The morbidity that is associated with viral and bacterial infection highlights the role of high-efficiency mitochondrial bioenergetics. Complex behavioral, cognitive, and motor activities may be functionally linked to the fine-tuned cellular metabolic processes, which, when altered following widespread infection [17,19]. Therefore, whole-body bioenergetics is reciprocally and synergistically dependent on the mitochondrial genomic health of the host. Also, the microenvironment in areas of tissue damage may serve as reservoirs for persistent viral and bacterial by products, resulting in chronic inflammation [19]. NO signaling is evolutionarily conserved and complex, highlighting its importance in disease chronicity, including persistent neuroinflammation following SARS-CoV-2 infection [19].

Recent reports by medical journalists indicate that the second dose of the vaccine to SARS-CoV-2 may reduce the incidence ‘long COVID’ syndromes, including ‘brain fog’ [21]. This association has not been formally investigated, possibly because SARS-CoV-2 vaccine programs have only recently been developed and delivered. Hopefully, continuing studies on the long-term sequelae of COVID-19 may increase our understanding of viral pathogenesis and neuropsychiatric disease.

Conclusions

In this editorial, we have presented the hypothesis that neuropsychiatric disorders such as brain fog and chronic fatigue syndrome may support that viral and bacterial infections have damaging effects on normal immune processes that persist due to our persisting lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of long-term neuroinflammation. Therefore, because ‘long COVID’ is now recognized to affect up to one-third of people following SARS-CoV-2 infection, increased studies and resources should be directed to understanding the pathogenesis of these new post-viral syndromes, including long-term neuropsychiatric COVID-19. Further research on microglia, mitochondria, and neuroinflammation may answer the questions raised by the hypothesis discussed in this editorial.

References

- 1.Esch T, Stefano GB, Ptacek R, Kream RM. Emerging roles of blood-borne intact and respiring mitochondria as bidirectional mediators of pro- and anti-inflammatory processes. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924337. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e928996. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefano GB, Ptacek R, Ptackova H, et al. Selective neuronal mitochondrial targeting in SARS-CoV-2 infection affects cognitive processes to induce ‘brain fog’ and results in behavioral changes that favor viral survival. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e930886. doi: 10.12659/MSM.930886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutta S, Das N, Mukherjee P. Picking up a fight: Fine tuning mitochondrial innate immune defenses against RNA viruses. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salmond GP, Fineran PC. A century of the phage: Past, present and future. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:777–86. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris HMB, Hill C. A place for viruses on the tree of life. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:604048. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.604048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: Rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med (Lond) 2021;21:e63–67. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein DS. The extended autonomic system, dyshomeostasis, and COVID-19. Clin Auton Res. 2020;30(4):299–315. doi: 10.1007/s10286-020-00714-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefano GB. Historical insight into infections and disorders associated with neurological and psychiatric sequelae similar to long COVID. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e931447. doi: 10.12659/MSM.931447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein DS. The possible association between COVID-19 and postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2020;20:31141–43. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vicenzi M, Di Cosola R, Ruscica M, et al. The liaison between respiratory failure and high blood pressure: evidence from COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001157. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01157-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novak CB, Scheeler VM, Aucott JN. Lyme disease in the era of COVID-19: A delayed diagnosis and risk for complications. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2021;2021:6699536. doi: 10.1155/2021/6699536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeza-Velasco C, Bulbena A, Polanco-Carrasco R, Jaussaud R. Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral considerations for chronic pain management in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility-type: A narrative review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:1110–18. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1419294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosseini S, Wilk E, Michaelsen-Preusse K, et al. Long-term neuroinflammation induced by influenza A virus infection and the impact on hippocampal neuron morphology and function. J Neurosci. 2018;38:3060–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1740-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sejvar JJ. The long-term outcomes of human West Nile virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1617–24. doi: 10.1086/518281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chertow DS. Understanding long-term effects of Ebola virus disease. Nat Med. 2019;25:714–15. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefano GB, Esch T, Ptacek R, Kream RM. Dysregulation of nitric oxide signaling in microglia: Multiple points of functional convergence in the complex pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e927739. doi: 10.12659/MSM.927739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stefano GB, Esch T, Kream RM. Behaviorally-mediated entrainment of whole-body metabolic processes: conservation and evolutionary development of mitochondrial respiratory complexes. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:9306–9. doi: 10.12659/MSM.920174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefano GB, Goumon Y, Bilfinger TV, et al. Basal nitric oxide limits immune, nervous and cardiovascular excitation: Human endothelia express a mu opiate receptor. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;60(6):513–30. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boziki MK, Mentis AA, Shumilina M, et al. COVID-19 immunopathology and the central nervous system: Implication for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases with associated demyelination. Brain Sci. 2020;10(6):345. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein L, Guarino B. Some long-haul covid-19 patients say their symptoms are subsiding after getting vaccines. Washington Post. Mar 16, 2021. [accessed on 18th April 2021]. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/long-haul-covid-vaccine/2021/03/16/6effcb28-859e-11eb-82bc-e58213caa38e_story.html.