Abstract

Ethionamide (ETH) is a commercial drug, used as a second-line resource to neutralize Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. It is proven that its metabolization in the organism leads to the formation of the active form of the drug, but some metabolic pathways may lead to the loss of its activity. Our work proved that the presence of oxidized methionine in cells could influence ETH's degradation, leading to the appearance of an inactive metabolite that is detectable by HPLC and mass spectrometry. In addition, it was found this process increases with the degree of methionine oxidation. This study contributes to a better understanding of ethionamide's metabolism in living organisms, and can help in the design of new drugs or ethionamide boosters for the combat of multidrug resistant tuberculosis.

Ethionamide (ETH) is a commercial drug, used as a second-line resource to neutralize Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections.

Introduction

One of the major health menaces in the 21st century is pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 This disease has a major impact worldwide because it is currently leading as the most lethal infectious disease, with an estimated one third of the world's population being infected. By 2014 the WHO estimated about 9.6 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths. Also, there has been an increase in the global TB incidence among individuals infected with HIV (about 12%).2

TB control is further conditioned by the appearance and continuous growth of antibiotic resistant species (multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB)), which leads to the increased use of second-line drugs with much more noticeable side effects.3 By 2014 it was estimated that 480 000 patients were infected with MDR-TB.4 MDR-TB occurs when there is concomitant resistance to rifampicin (RIF) and isocyanide (INH), which are the most effective first-line drugs.5 Given the limited knowledge on relevant mechanisms of drug resistance in TB,6 it is urgent to develop new strategies to improve the bioavailability of anti-TB drugs.

Ethionamide (Scheme 1, ETH, 1) is one of the commercially available antituberculosis drugs used as a second-line resource to MDR-TB treatment.7 This drug is quite effective against M. tuberculosis, however it is very toxic and has a low therapeutic index, so its use is very restricted.8 ETH is a thioamide antibiotic structurally similar to INH and shares the same biological target, the enoyl–acyl carrier protein reductase InhA.9 This is an essential enzyme of M. tuberculosis and is involved in the synthesis of specific components of its cell wall.10

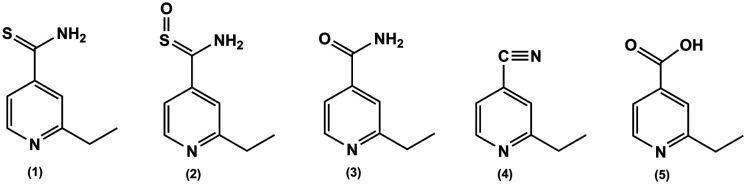

Scheme 1. Structure of ETH (1) and its reported oxidation metabolites: ETH-SO (active) (2) and inactive metabolites (3–5).

The mechanism of action of ETH was only partially elucidated more recently but there are some questions to answer. It is known that, upon EthA activation, ETH is metabolized in the organism into its active form, an S-oxide derivate (Scheme 1, ETH-SO, 2).11 Other work demonstrated one alternative pathway that is independent of the transcriptional repressor EthR. Generation of spontaneous ETH-resistant mutants confirmed a role for MshA in ETH killing activity in an EthA/R-independent manner.12 EthA is a monooxygenase that uses flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor and is NADPH- and O2-dependent.13 The activated form of ETH binds to NAD+/NADH forming adducts that inhibit the InhA gene product, enoyl-reductase. In vivo studies, both in mammals and bacteria, suggest that ETH-SO retains the biological activity of the parent drug.11 Indeed, this is in line with the fact that ETH and many current antimycobacterial agents require some form of cellular activation, corresponding to the oxidative, reductive, or hydrolytic unmasking of active groups.14–16 Besides the active metabolite, there are other metabolic pathways that yield non-active products, where the thioamide moiety is converted into a carboxamide (3, Scheme 1) carbonitrile (4, Scheme 1) or carboxylic acid (5, Scheme 1). The proposed mechanism for ETH metabolic activation leading to the formation of some of these non-active metabolites has been proposed only recently.10

Whenever a drug is developed, care is taken to minimize the formation of reactive metabolites.17 All aerobic organisms generate these species from mitochondrial respiration, NADPH oxidase and other metabolic processes.18–20 ROS play a significant role in the degradation of the human condition over time, affecting its most vital structures such as DNA, lipids, and proteins.21 However, M. tuberculosis has defence mechanisms against this oxygen-rich environment that humans do not possess.22 An administered drug that contains in its structure oxidizable groups may undergo reaction with these ROS and generate secondary metabolites with no therapeutic interest. The bioactivation process of thiono-sulphur drugs seems to be directly related to the toxicity of these compounds.23 In fact, drugs containing heteroatoms such as sulphur, nitrogen or phosphate are readily oxidized due to the presence of these soft nucleophiles. S-Oxygenation is a very important reaction in the metabolism of sulphur-containing drugs. However, the sulphur atom is bioactivated to conceivably reactive metabolites such as S-oxide and sulfenic acid.24 Thionamides, thioureas, thiocarbamates, and thiones are S-oxygenated by flavin-containing monooxygenases25 to their higher states S-oxides through sulfenic acid,26 which can then react with macromolecular cellular proteins, forming protein-electrophile adducts and subsequently triggering adverse drug reactions. Sulfenic acid is, however, unstable, and disproportionate to form a stable S-oxide,27 which is also a reactive intermediate, and has the capacity to also bind to cells. In addition, this is supported by the acknowledgement that a large number of antituberculosis drugs are hepatotoxic due to the bioactivation process of ETH.28

HepG2 is a hepatoma cell line widely used both in pharmacological and toxicological studies since liver is the main target of drug metabolites. HepG2 cells are especially useful for studying the toxicity of chemicals that affect DNA replication and cell cycling because it can take several cell passages before the threshold of toxic effect is reached. These cells are quite easy to maintain in culture and are widely used for toxicological studies. However, the most dramatic disadvantage of hepatic cell lines in toxicological and pharmacological studies is the absence or much lower expression of some key drug-metabolizing enzymes such as CYP3A4, CYP2A6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, in comparison with primary human hepatocytes.29 For this reason, some authors defend cell stimulation with nuclear receptor activators or treatment with CYP inductors before toxicity assays.30 In addition to toxicity studies, the HepG2 cell line have also been used in several studies on drug metabolism,31–34 including on ethionamide.35 In this study, the control lack of methionines oxidized from cell line is advantageous since it allows inferring the effect of phase I and II metabolic enzymes of HepG2. The absence of the studied metabolites allowed us to understand that their formation was due to the presence of the respective family of methionines.

Amino acid oxidation, particularly in the cystine (Cys) and methionine (Met) residues of proteins, is a naturally occurring process in cells. It is triggered by the presence of ROS or other oxidants and is usually corrected by the organisms' endogenous enzymes.36 Methionine is an essential amino acid that is obtained through diet and is present at the core of various metabolic pathways.37 In addition, Met is involved in other important processes such as protein translation (it is the first AA to be incorporated in the N-terminal sequence) resulting in a limiting factor of protein synthesis if their levels are reduced. This amino acid is also involved in redox homeostasis, in sulphur metabolic processes and in the transsulfuration pathway. It also regulates the production of antioxidants and other sulphur compounds, which are involved in the defence against oxidative stress, such as glutathione, taurine and cystine that help to combat the effects of ROS.38 In addition, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), another key metabolite produced from Met, is a major methyl donor in cells and an epigenetic regulator.39,40

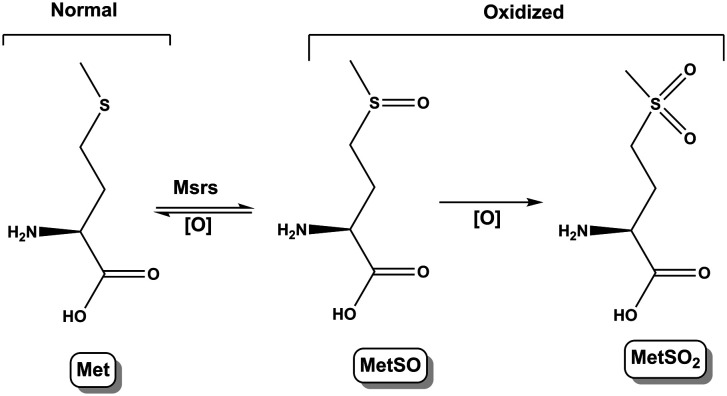

Met is highly susceptible to oxidation by ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Methionine sulfoxide (MetSO) and methionine sulfone (MetSO2) are the major products of methionine oxidation (Scheme 2). Nevertheless, the reduction of methionine sulfoxide into methionine by methionine sulfoxide reductases (Msrs) is the only reversible system (regarding the amino acids oxidation) and serves as a catalytic antioxidant mechanism against deleterious effects of oxidative stress on proteins.41 MetSO is a major quantitative marker of protein oxidation in cellular and extracellular proteins. Msrs isozymes reduce MetSO residues in proteins and MetSO free adduct.42 The oxidation of Met residues is independent of pH.

Scheme 2. Mechanism of methionine oxidation, leading to metabolites MetSO and MetSO2.

In this work, and after our experience with observation of oxidation metabolites of ETH,35 we tried to assess the thioamide group reactivity's in ETH's biodegradability under oxidative damage induced by amino acids. For this purpose, we used HepG2 cells and analyse the degradation of ETH and the formation of its metabolites in the presence of methionine (in its native and oxidized forms – MetSO and MetSO2) by HPLC and mass analysis. It was found the presence of an oxidized amino acid such as Met in cells (triggered by ROS) can influence ETH's degradation, inducing the appearance of an inactive ETH metabolite. These findings contribute for a better understanding of ETH's metabolism in living organisms and can also help in the design of new drugs or ethionamide boosters for the combat of multidrug resistant tuberculosis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human hepatoma cell line, HepG2 (ATCC®) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma Aldrich®) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U mL−1 penicillin and 50 g mL−1 streptomycin. The passage number was less than 10 for all experiments performed. Cells were seeded onto 60 × 15 mm cell culture dishes at a cell density of 5 × 105 in 5 mL of culture media and were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 until they were 70 to 80% confluent (cell confluence was evaluated by visual observation using an optical microscope).

Metabolization of ETH in HepG2 cells

To assess the influence of methionine oxidation on ETH metabolization, HepG2 cells were treated with ETH in the absence or presence of Met, MetSO and MetSO2, at concentrations of 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.75 mM and 2 mM during 3 h, 24 h or 48 h. Cells were also treated with Met, MetSO and MetSO2 alone at concentrations of 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.75 mM to assess cell metabolization of these compounds. At the end of the incubation times, cells were lysed, centrifuged and the supernatant was collected. Metabolites were screened by LC-MS.

LC/UV-DAD/ESI-MSn analyses

LC/DAD/ESI-MSn analyses were performed on a Finnigan Surveyor Plus HPLC (Thermo Scientific®, USA) instrument equipped with a diode-array detector and a mass detector. The HPLC system consisted of a quaternary pump, an autosampler, a degasser, a photodiode-array detector, and a thermostatted column compartment that was kept at 25 °C. An end-capped Merck Purospher C-18 column (150 mm 4 mm; 5 μm particle diameter, end-capped) was used and the elution gradient was 0% B (0 min) to 100% B (30 min), with A = 0.1% (v/v) aqueous trifluoroacetic acid and B = acetonitrile, both previously degassed and filtered. The column was re-equilibrated for 10 min between injections. The mass detector was a Finnigan Surveyor LCQ XP MAX quadruple ion trap mass spectrometer (MS) equipped with an ESI interface. Control and data acquisition were carried out with Xcalibur software (ThermoFinnigan®, San Jose, USA).

The intensity values presented refer to averages of three tests. Nitrogen above 99% purity was used, and the gas pressure was 520 kPa (75 psi). The instrument was operated in positive-ion mode with electrospray ionization (ESI) needle voltage, 5.00 kV; ESI capillary temperature was 325 °C; full scans covered the mass range m/z from 50 to 2000. MS/MS data were simultaneously acquired for the selected precursor ion. Collision-induced dissociation CID-MS/MS experiments were performed using helium as the collision gas with 25–35 eV of energy.

Physicochemical properties of ETH, ETH-SO and 4

Details on the physicochemical properties of ETH, ETH-SO and 4, including dose and dosage form information, are given in Table 1. The values provided are based on literature information, default values provided in GastroPlus version 9.5 (Simulations Plus), and ADMET Predictor version 8.5 (Simulations Plus).

Predicted physicochemical properties of ETH, ETH-SO and 4. Dosage form (human): IR (tablet) 100 mg; dose volume (human): 250 mL; mean precipitation time: 900 s; drug particle density: 1.2 m mL−1; particle size (radius): 25.0 μm.

| Property | ETH (1) | ETH-SO (2) | ETH-CN (4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted log Pa (S + log P) | 1.263/1.33c | −0.618 | 1.388 |

| S + log Da | 1.263 | −3.035 | 1.388 |

| M log Pa | 0.830 | 0.419 | 0.830 |

| T_PSAa | 38.910 | 55.980 | 36.680 |

| HBDHa | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| Diffusion coefficientb (DiffCoef) (cm2 s−1) | 1.04 × 10−5 | 1.06 × 10−5 | 1.14 × 10−5 |

| Blood/plasma concentration ratiob | 1.19 | 1.28 | 0.73 |

| P eff b (cm s−1) | 3.51 × 10−4 | 2.42 × 10−4 | 7.10 × 10−4 |

| Aqueous solubilityb (mg mL−1) | 1.02 (pH = 7.63)/0.839c | 103.85 (pH = 11.98) | 5.88 (pH = 8.24) |

| CLb (L h−1) | 5.49 | 20.4 | 3.18 |

From ADMET Predictor version 8.5.

From GastroPlus Default.

From DrugBank; S + log P: predicted log of the octanol/water partition coefficient; S + log D: predicted log D at pH 7.4; M log P: predicted log P using Moriguchi's model; T_PSA: topological polar surface area; HBDH: number of OH and NH hydrogen bond donor protons; DiffCoef: Hayduk and Laudie's estimation of diffusion coefficients.

Results and discussion

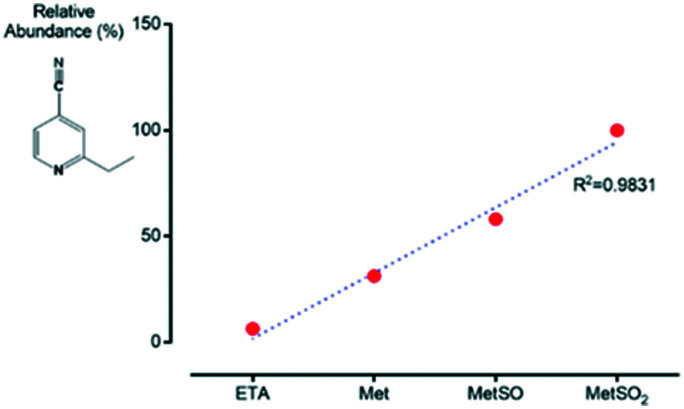

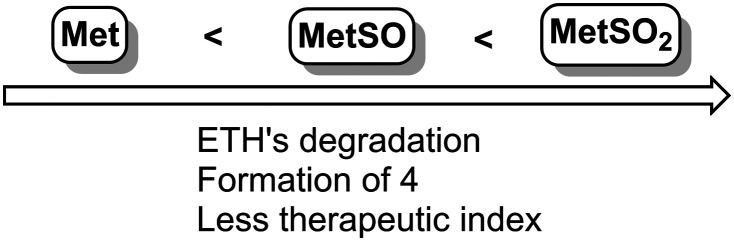

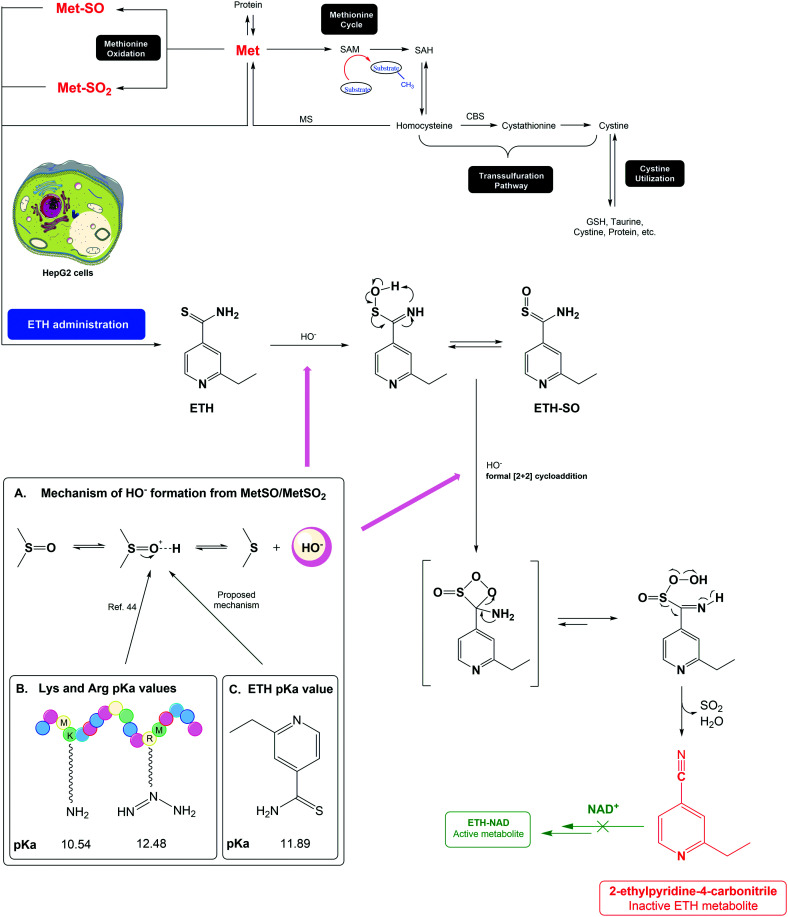

Ethionamide is a drug used in the treatment of TB. Despite being effective through the formation of its active metabolite ETH-SO, studies report the formation of inactive metabolites that decrease its effectiveness, where the thioamide moiety is converted into a carboxamide, carbonitrile or carboxylic acid (3–5, Scheme 1). In this context, our group intended to evaluate the influence of the degree of oxidation of amino acids such as methionine in the formation of inactive metabolites of ethionamide. Control was done by comparing the formation of ETH metabolites in the absence or presence of Met, MetSO and MetSO2 with no HepG2 cells. Over time, these results did not demonstrate the formation of the inactive carbonitrile ETH metabolite. HepG2 cells were treated with ethionamide alone or in the presence of methionine with different degrees of oxidation: Met, MetSO and MetSO2. To discard metabolites derived from the metabolization of methionine by cells, they were also treated with increasing concentrations of this amino acid alone, during different incubation times. At each stage, the cells were lysed, centrifuged and the supernatant was analyzed by LC-MS. The results allow us to conclude that the formation of the inactive metabolite where the thioamide moiety is converted into carbonitrile (4, Scheme 1) occurs in the presence of methionine. This formation is greater as the degree of oxidation of the amino acid increases (Fig. 1). As M. tuberculosis is resistant both to ROS and MetSO, we hypothesized that the presence of oxidized amino acids in cells, triggered by ROS naturally formed in the cells, such as methionine, can influence ETH's degradation inside cells, leading to the appearance of inactive ETH metabolites. This process, which seems to be dependent on the degree of Met oxidation, contributes to the reduction of the formation of the active metabolite of ETH and consequently to the decrease of its effectiveness in the treatment of the disease (Scheme 3).

Fig. 1. Relative abundance of the ETH carbonitrile inactive metabolite in HepG2 cells treated with ETH alone or in the presence of 2 mM of Met, MetSO and MetSO2 after 3 h.

Scheme 3. ETH's degradation is induced by methionine oxidation, resulting in the formation of inactive metabolites with less therapeutic index.

To predict the possible behavior of this inactive metabolite in patients with TB, GastroPlus® software was used to simulate its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, as described in Table 1. GastroPlus is a simulation software that simulates intravenous, oral, oral cavity, ocular, inhalation, dermal, subcutaneous, and intramuscular absorption, biopharmaceutics, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics both in humans and animals. Although this drug is described in the literature as being an inactive metabolite, we have found its presence can have severe consequences on the therapeutic efficacy of ETH since its formation leads to less availability of ETH and consequently its active metabolite, ETH-SO. In addition, this metabolite 4 has unique properties that allow it to remain in the body longer (CL value is lower than ETH and ETH-SO, so the metabolite remains longer In the organism and is more toxic), to have good permeability capacity (Peff is also higher than ETH), significant plasma protein binding and lower blood/plasma concentration ratio.

We propose the lungs of patients with tuberculosis may be compromised with an increased degree of oxidation, and a greater formation of ROS that will attack the structures present in cells, such as proteins and amino acids. In fact, recent studies report the increased presence of different amino acid levels in patients with tuberculosis, with high levels of methionine sulfone being reported.43 This oxidation may potentiate the metabolism of ETH in a metabolite without pharmacological activity (carbonitrile metabolite), reducing its effectiveness (Scheme 4). In addition, the bacteria that cause the disease are resistant to ROS, so there may be a need to administer cocktails with antioxidants, e.g.

Scheme 4. Proposed mechanism for ETH metabolic activation leading to the formation of non-active metabolites in the presence of Met/Met-SO or Met-SO2.44.

Conclusions

In this study, we assessed the metabolic degradation of ETH in HepG2 cells under the presence of MetSO and MetSO2, to mimic the effect of both normal and severe oxidizing conditions, respectively. Scheme 4 summarizes the possible metabolic process that leads to the formation of inactive metabolites of ETH in the presence of an oxidative environment. Our group hypothesized that patients infected with TB may have the presence of oxidized amino acids, such as methionine, due to a greater production of ROS in the lungs. The bacteria that cause this disease are resistant to these radicals and remain active in the patient's body. ETH, a drug administered to TB patients, will undergo hepatic metabolism that may originate an active metabolite, ETH-SO, but also undesired metabolites without pharmacological activity, such as 2-ethylpyridine-4-carbonitrile, which we found to have a longer life span in the patients' organisms and an unwanted pharmacokinetic profile, leading to a decrease in the effectiveness of ETH. Together, these findings contribute for a better understanding of ETH's metabolism in living organisms and can also help in the design of new drugs or ETH boosters for the combat of multidrug resistant tuberculosis.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded from “Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia” (FCT, Portugal) and FEDER – Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional funds through the COMPETE 2020 – Operacional Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation (POCI), Portugal 2020, in the framework of the project IF/00092/2014/CP1255/CT0004. NV thanks FCT by supporting these studies through project from National Funds, within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020). H. A. Santos acknowledges financial support from the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation and the HiLIFE Research Funds.

References

- Palmer A. L. Leykam V. L. Larkin A. Krueger S. K. Phillips I. R. Shephard E. A. Williams D. E. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:1147–1159. doi: 10.3390/ph5111147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L. Miller K. D. Jemal A. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian I. Colebunders R. Drugs. 1999;58:633–661. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait W. N. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:253. doi: 10.1038/nrd3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale N. Correia A. Silva S. Figueiredo P. Mäkilä E. Salonen J. Hirvonen J. Pedrosa J. Santos H. A. Fraga A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:403–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenzo D. Mousa S. A. Acta Trop. 2011;119:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S. Mokaddas E. Respir. Med. CME. 2010;3:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff K. A. Nguyen L. Expert Rev. Anti-infect. Ther. 2012;10:971–981. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomino J. C. Martin A. Antibiotics. 2014;3:317–340. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics3030317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde J. Deraeve C. Duhayon C. Pratviel G. Bernardes-Génisson V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:8848–8858. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01561a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBarber A. E. Mdluli K. Bosman M. Bekker L.-G. Barry C. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:9677–9682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang M. L. T. Rahim S. Z. Z. de Sessions P. F. Lin W. Koh V. Pethe K. Hibberd M. L. Alonso S. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:710. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannelli T. A. Dykman A. de Montellano P. R. O. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12824–12829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcheze C. Weisbrod T. R. Chen B. Kremer L. Hazbón M. H. Wang F. Alland D. Sacchettini J. C. Jacobs W. R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:708–720. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.708-720.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge A. G. Richman J. E. Johnson G. Wackett L. P. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7468–7476. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01421-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover L. G. Alahari A. Gratraud P. Gomes J. M. Bhowruth V. Reynolds R. C. Besra G. S. Kremer L. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1055–1063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01063-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalgutkar A. S. Didiuk M. T. Chem. Biodiversity. 2009;6:2115–2137. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth J. D. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2007;43:332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2002;33:774–797. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00956-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski A. J. de Souza-Pinto N. C. Castilho R. F. Vercesi A. E. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009;47:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M. Leibfritz D. Moncol J. Cronin M. T. D. Mazur M. Telser J. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. G. VanderVen B. C. Lee W. Abramovitch R. B. Kim M. Homolka S. Niemann S. Rohde K. H. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal R. A. Halpert J. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1982;22:321–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga F. I. Loi D. Ling K. H. J. Tang-Liu D. D. S. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012;8:467–485. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.668528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson M. C. Siddens L. K. Morré J. T. Krueger S. K. Williams D. E. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;233:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson M. C. Siddens L. K. Krueger S. K. Stevens J. F. Kedzie K. Fang W. K. Heidelbaugh T. Nguyen P. Chow K. Garst M. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014;278:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipiso K. Simoyi R. H. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016;761:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran G. Swaminathan S. Drug Saf. 2015;38:253–269. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0267-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink W. M. A. Schoonen W. G. E. J. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2007;21:1592–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkening S. Stahl F. Bader A. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003;31:1035–1042. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lançon A. Hanet N. Jannin B. Delmas D. Heydel J.-M. Lizard G. Chagnon M.-C. Artur Y. Latruffe N. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007;35:699–703. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.013664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birringer M. Pfluger P. Kluth D. Landes N. Brigelius-Flohé R. J. Nutr. 2002;132:3113–3118. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe A. L. Snawder J. E. Benson R. W. Roberts D. W. Casciano D. A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;190:15–19. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharnagl H. Schinker R. Gierens H. Nauck M. Wieland H. März W. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;62:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale N. Mäkilä E. Salonen J. Gomes P. Hirvonen J. Santos H. A. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012;81:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G. Weiss S. J. Levine R. L. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, General Subjects. 2014;1840:901–905. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabkin H. J. RajBhandary U. L. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5140–5147. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métayer S. Seiliez I. Collin A. Duchêne S. Mercier Y. Geraert P.-A. Tesseraud S. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008;19:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterland R. A. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1706S–1710S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1706S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrey C. L. Liu L. Andrews L. G. Tollefsbol T. O. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:R139–R147. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R. Moskovitz J. Levine R. L. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2003;5:577–582. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer C., Faragher R. and Thornalley P., Redox metabolism and longevity relationships in animals and plants, Garland Science, 2009, vol. 62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrieling F. Alisjahbana B. Sahiratmadja E. van Crevel R. Harms A. C. Hankemeier T. Ottenhoff T. H. M. Joosten S. A. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54983-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T. Heinemann S. H. J. Physiol. 2001;531:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]