Abstract

The most widely used method for the control of the Aedes aegypti mosquito population is the chemical control method. It represents a time- and cost-effective way to curb several diseases (e.g. dengue, Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever) through vector control. For this reason, the discovery of new compounds with a distinct mode of action from the available ones is essential in order to minimize the rise of insecticide resistance. Detoxification enzymes are an attractive target for the discovery of new insecticides. The kynurenine pathway is an important metabolic pathway, and it leads to the chemically stable xanthurenic acid, biosynthesized from 3-hydroxykynurenine, a precursor of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, by the enzyme 3-hydroxykynurenine transaminase (HKT). Previously, we have reported the effectiveness of 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives acting as larvicides for A. aegypti and AeHKT inhibitors from in vitro and in silico studies. Here, we report the synthesis of new sodium 4-[3-(aryl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] propanoates and the cognate HKT-inhibitory activity. These new derivatives act as competitive inhibitors with IC50 values in the range of 42 to 339 μM. We further performed molecular docking simulations and QSAR analysis for the previously synthesized sodium 4-[3-(aryl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] butanoates reported earlier by our group and the data produced herein. Most of the 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives, including the canonical compounds for both series, showed a similar binding mode with HKT. The binding occurs similarly to the co-crystallized inhibitor via anchoring to Arg356 and positioning of the aromatic ring and its substituents outwards at the entry of the active site. QSAR analysis was performed in search of more than 770 molecular descriptors to establish a relationship between the lowest energy conformations and the IC50 values. The five best descriptors were selected to create and validate the model, which exhibited parameters that attested to its robustness and predictability. In summary, we observed that compounds with a para substitution and heavier groups (i.e. CF3 and NO2 substituents) had an enhanced HKT-inhibition profile. These compounds comprise a series described as AeHKT inhibitors via enzymatic inhibition experiments, opening the way to further the development of new substances with higher potency against HKT from Aedes aegypti.

Water-soluble oxadiazole-based HKT inhibitor library, comprising a new class of compounds for control of Aedes aegypti dissemination, act as competitive HKT enzyme inhibitors, promoting accumulation of the toxic metabolite 3-hydroxykynurenine in insect organism.

Introduction

Arboviruses are a heterogeneous group of viruses transmitted by hematophagous arthropods. The most disseminated arboviruses in Brazil belong to the Flaviviridae family, comprising viruses that cause yellow fever, dengue and Zika;1 or to the Togaviridae family, such as the alphavirus, which causes chikungunya fever.2 These viruses cause asymptomatic infections or pyretic diseases in humans both in the wild and in urban cycles and are quite ubiquitous in tropical regions due to geographical distribution of the vector insect.3 A consequential discovery for public health was the discovery that Zika virus causes a congenital syndrome in newborns whose mothers were infected during pregnancy.4,5 This syndrome is responsible for infantile microcephaly and cases of malformation and can be sexually transmitted by infected human males.6–9 The inexistence of effective vaccines for immunization against all the viruses and their serotypes makes vector species population control the most operative and affordable alternative to disease control. Therefore, coordinated efforts have been focused on containing the main transmitting vector of those arboviruses, the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Since A. aegypti is extremely adapted to the domestic environment,10–12 the development of products capable of eliminating larvae or the adult insect in household water reservoirs offers one viable alternative to slow down the transmission of arboviruses.

Numerous expedients can be used to control A. aegypti dissemination, such as biological, chemical, mechanical and biotechnological control, and these can be used alone or in an integrated manner.13 Among these, chemical control can be highlighted as the cheapest of the effective approaches to limit mosquito propagation.14–17 Notably, because A. aegypti larvae are mostly found at the surface of small domestic water reservoirs, the potential environmental toxicity associated to chemical control is greatly minimized. Chemical control involves the use of organic or inorganic insecticides, the latter not being environmentally viable, since most inorganic pesticides contain heavy metals in their formulae, thus showing high toxicity to animals.18 The most commonly used organic insecticides are organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates and pyrethroids, all acting directly on the insect nervous system.19–21 Hence, there is an unceasing need for the development of new insecticides once some of these larvicides lose potency through the development of insect resistance. The search for environment-friendly products with less harmful toxicological profiles is essential to achieve new candidates for A. aegypti control.

Mechanisms that lead to accumulation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the insect organism are a powerful therapeutic weapon against A. aegypti. One of the most important metabolic pathways in detoxifying reactive oxygen species is the so-called kynurenine pathway, the major tryptophan catabolism pathway in living organisms. In this biochemical pathway, tryptophan is oxidized to quinolinic or kynurenic acid or even xanthurenic acid, depending on the organism.22–24 These endogenous acids can be totally oxidized to CO2 and water or even used in the biosynthesis of other substances, such as nicotinamide.25 In mosquitoes, this pathway leads to a chemically stable species, xanthurenic acid (XA). This acid is biosynthesized from 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) in a process catalyzed by 3-hydroxykynurenine transaminase (HKT),26–29 the sole enzyme responsible for 3-HK regulation in mosquitoes.29 Therefore, inhibition of the enzymatic conversion of 3-HK to xanthurenic acid in the kynurenine pathway consists in a powerful approach to control A. aegypti development via the accumulation of 3-HK.

Our research group has been involved in the synthesis and characterization of larvicidal heterocycles for a while.30–33 Recently, we have reported the discovery of new 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives as inhibitors of HKT from A. aegypti (AeHKT), providing direct evidence that HKT can be explored as a molecular target for the discovery of a novel class of chemical insecticides against A. aegypti.32,33 The past advancements in our endeavor to develop specific inhibitors for AeHKT led us to further explore the synthesis of new water-soluble oxadiazole salts with inhibitory activity against recombinant AeHKT in vitro and to characterize the structural features of the resulting complex through computational methods.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

This second generation of water-soluble oxadiazole salts belong to a unique class of insecticides possessing a 1,2,4-oxadiazole nucleus. 1,2,4-Oxadiazoles are five-membered heterocycles with two nitrogen atoms and one oxygen, and they have been reported as amides and ester bioisosteres with numerous biological activities attributed to molecules containing this heterocycle as part of its scaffold.34

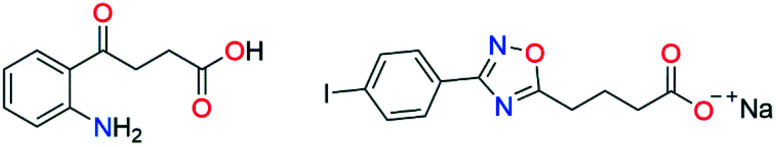

The interest in this recently discovered class of AeHKT inhibitors began with the recognition of a structural similarity between a known HKT crystallographic inhibitor, 4-(2-aminophenyl)-4-oxobutyric acid (4-OB), and some of the 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives with larvicide activity developed by our research group. Previous in silico studies showed that these heterocyclic compounds could have similar binding modes and affinity for HKT as the crystallographic inhibitor.32 Further studies demonstrated that the oxadiazole derivatives de facto worked as inhibitors of HKT from Aedes aegypti, thus confirming our previously formulated hypothesis (Fig. 1).33

Fig. 1. Structures of HKT inhibitors 4-(2-aminophenyl)-4-oxobutyric acid (4-OB) and sodium 4-[3-(4-iodo-phenyl)-[1,2,4] oxadiazol-5-yl]-butanoate.

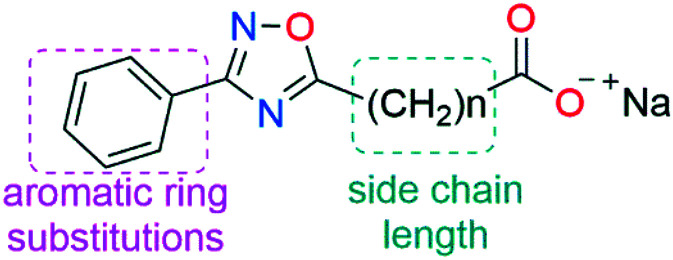

In order to obtain more potent water-soluble AeHKT inhibitors, we evaluated the effect of two types of modifications in the oxadiazole scaffold (Fig. 2): modifications in the aromatic ring bound to the C-3 position of the heterocycle and variations on the length of the carboxylate side chain. These structural changes provided a useful way to investigate potential structure–activity relationships to enhance the AeHKT antagonist activity of 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives.

Fig. 2. Modifications made on oxadiazole derivatives in this work.

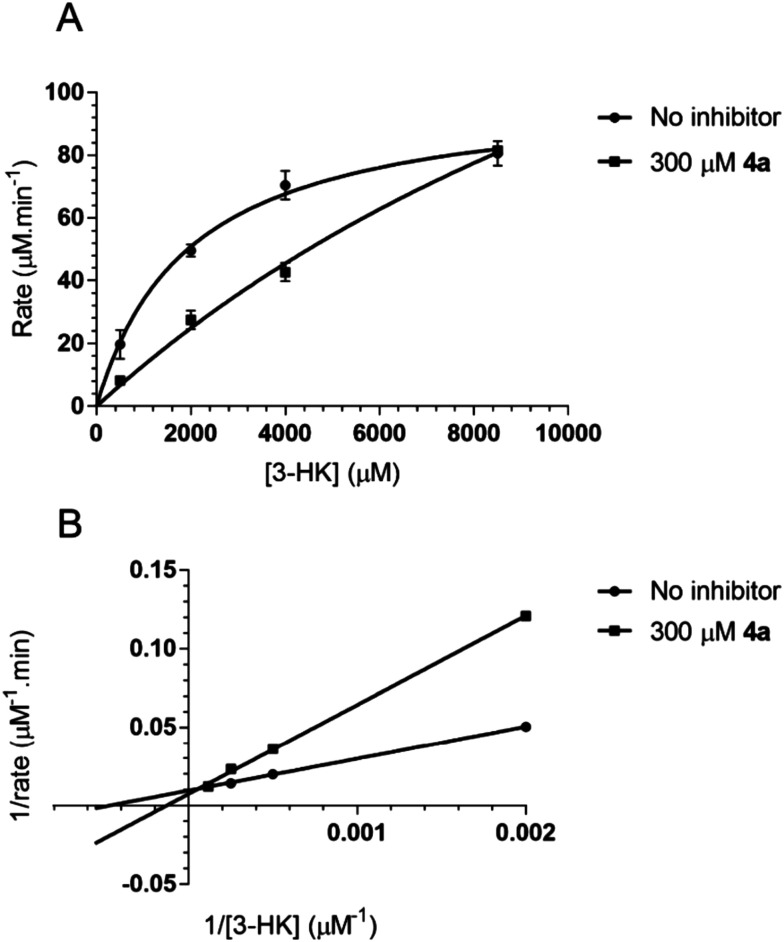

The inhibitors were synthesized from arylamidoximes and succinic anhydride to form 3-[3-(aryl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] propanoic acids. Arylamidoximes were prepared from the corresponding arylnitriles and hydroxylamine.30 After purification, the acids reacted with sodium hydroxide in methanol, yielding the corresponding sodium salts, which were tested for inhibitory activity against AeHKT (Scheme 1). Alternatively, 4-[3-(aryl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] butanoic acids can be synthesized by a reaction of glutaric anhydride with its respective arylamidoxime, and then the corresponding sodium salts can be obtained as previously reported by Maciel and colleagues.33

Scheme 1. Synthesis of oxadiazole salts tested as AeHKT inhibitors. (i) NH2OH.HCl and NaHCO3 (4 eq.), ethanol/H2O, r.t.; (ii) succinic anhydride (1.5 eq.), neat, 140 °C; (iii) NaOH (1 eq.) and methanol, r.t; (iv) glutaric anhydride (1.5 eq.), neat, 140 °C; (v) NaOH (1 eq.) and methanol, r.t.

AeHKT inhibition assays

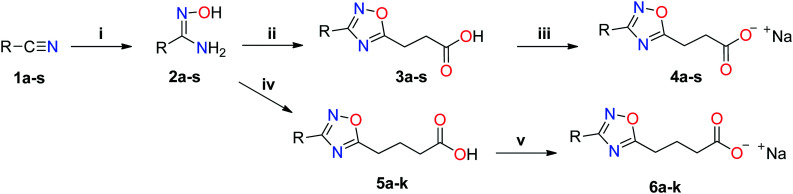

The mechanism of enzymatic inhibition was investigated for recombinant AeHKT with the saturation curve presented in Fig. 3A. It can be verified that the enzymatic reaction both in the presence and in the absence of the inhibitor 4a satisfies the Michaelis–Menten model. From the double-reciprocal plot (Lineweaver–Burk plot), the type of inhibition mechanism was estimated (Fig. 3B) in accordance with the competitive inhibition kinetics. In this type of inhibition, 4a occupies the active site, preventing the substrate 3-HK from binding to the AeHKT enzyme and therefore suppressing the transamination activity of the recombinant AeHKT enzyme. The addition of compound 4a caused changes in the regression slope and y-intercept, indicating the competitive inhibition.

Fig. 3. Inhibition mechanism of the canonical compound 4a. (A) Kinetic model of Michaelis–Menten inhibition in the presence and absence of inhibitor 4a. (B) Lineweaver–Burk plot for the enzymatic reaction in the presence and absence of inhibitor 4a.

Enzymatic assays were conducted using a recent standardized methodology developed by Maciel and colleagues.33,35 The assays allowed the quantification of xanthurenic acid (XA) converted from 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) by AeHKT in the presence of the inhibitor. The reaction was initiated by the combination of 2 μg of recombinant AeHKT, 2 mM of amino donor substrate (3-D, l-HK), 2 mM of sodium pyruvate as an amino acceptor and 40 μM of the cofactor pyridoxal-5′- phosphate (PLP) in a final volume of 100 μL. Reactions were stopped by adding 100 μL of a 10 mM FeCl3·6H2O solution in 0.1 M HCl. The assays were performed in duplicate, and a calibration curve was prepared to quantify the amount of XA generated by AeHKT (R2 = 0.98). The complex absorbance values were read at 570 nm after 5 minutes of incubation at 50 °C. Two tests were performed in the absence of XA, in order to verify if ferric ion could also complex with PLP and/or sodium pyruvate. Those assays showed no absorbance (<0.1), confirming the specificity of the complexation of Fe3+ to XA. The inhibitory activity of salts 4a–4s was assessed in duplicate by adding 500–50 μM of each diluted salt to 200 mM HEPES buffer pH 7/100 mM NaCl. In each assay, a negative control was taken into account when calculating the final activity percentage.

The IC50 values for each of the salts are compiled in Table 1. The two most active compounds displayed inhibition activity in the micromolar range (4b, IC50 = 35 μM; 4h, IC50 = 42 μM). A few trends can be identified concerning the relationship between chemical structure and inhibitory activity.

The molecular structure of 1,2,4-oxadiazole sodium salts tested as AeHKT inhibitors with their biological activity (IC50) and estimated ΔKI values.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | R | IC50 (μM) | ΔKIa | Code | R | IC50 (μM) | ΔKIa |

| 4a |

|

139 ± 1 | −5.2 | 4b |

|

35 ± 1 | −5.1 |

| 4c |

|

86 ± 1 | −7.0 | 4d |

|

119 ± 1 | −6.5 |

| 4e |

|

73 ± 1 | −6.1 | 4f |

|

110 ± 1 | −6.4 |

| 4g |

|

124 ± 1 | −4.9 | 4h |

|

42 ± 1 | −5.1 |

| 4i |

|

76 ± 1 | −6.4 | 4j |

|

85 ± 1 | −6.2 |

| 4k |

|

83 ± 1 | −6.4 | 4l |

|

157 ± 2 | −6.2 |

| 4m |

|

339 ± 2 | −5.9 | 4n |

|

84 ± 1 | −2.4 |

| 4o |

|

68 ± 1 | −3.8 | 4p |

|

85 ± 1 | −7.3 |

| 4q |

|

116 ± 1 | −4.4 | 4r |

|

61 ± 1 | −6.8 |

| 4s |

|

77 ± 1 | −6.4 | ||||

| 6a |

|

72 ± 1 | −6.2 | 6b |

|

101 ± 1 | −6.2 |

| 6c |

|

64 ± 1 | −7.3 | 6d |

|

110 ± 1 | −7.0 |

| 6e |

|

88 ± 1 | −6.8 | 6f |

|

54 ± 1 | −6.9 |

| 6g |

|

63 ± 1 | −7.4 | 6h |

|

70 ± 1 | −6.2 |

| 6i |

|

42 ± 1 | −7.2 | 6j |

|

294 ± 1 | −6.8 |

| 6k |

|

87 ± 1 | −7.1 | ||||

ΔKI = KI (4-OB) − KI (compound).

The modification of the 6-membered aromatic group (4a, phenyl) into 5-membered aromatic rings in 4n (2-furyl) and/or 4o (2-thiophenyl) was positive for the AeHKT inhibition reaction, given that the IC50 value decreased in the sequence 4a (139 μM) > 4n (84 μM) > 4o (68 μM). In fact, the thiophene ring is considered a phenyl group bioisostere since the thiophene ring is also aromatic and has similar electronic characteristics.36 This may be related to ring sizes, favoring a better fit of the smaller rings on the AeHKT active site.

Compounds having electron donor substituents on the aromatic ring exhibited higher IC50 values according to the proximity of the 1,2,4-oxadiazolic ring and to the placement of the substituent, with the para position IC50 < meta position IC50 < ortho position IC50. This is the case for 4e (73 μM), 4m (110 μM) and 4f (339 μM) compounds with a methyl group as a substituent on the aromatic ring. The same was observed for compounds with a methoxy group, 4b and 4l, in which the para compound had better performance. Even for nitro compounds, well-known electron-withdrawing substituents, it was observed that para-substituted oxadiazoles have lower IC50 values than the meta-substituted ones, 4i (76 μM) and 4p (85 μM), indicating that in these cases para-substitution leads to better AeHKT inhibitors. On the other hand, double substitution on the aromatic ring was not very effective in enhancing inhibitory activity against AeHKT. For example, compound 4c (3,4-dichlorophenyl) showed an IC50 value of 86 μM, which is similar to that of 4j (para-chloro, 85 μM) and 4s (ortho-chloro, 77 μM), the latter two being slightly more effective inhibitors with a single substitution on the aromatic ring.

Oxadiazole derivative binding modes and estimated binding energies

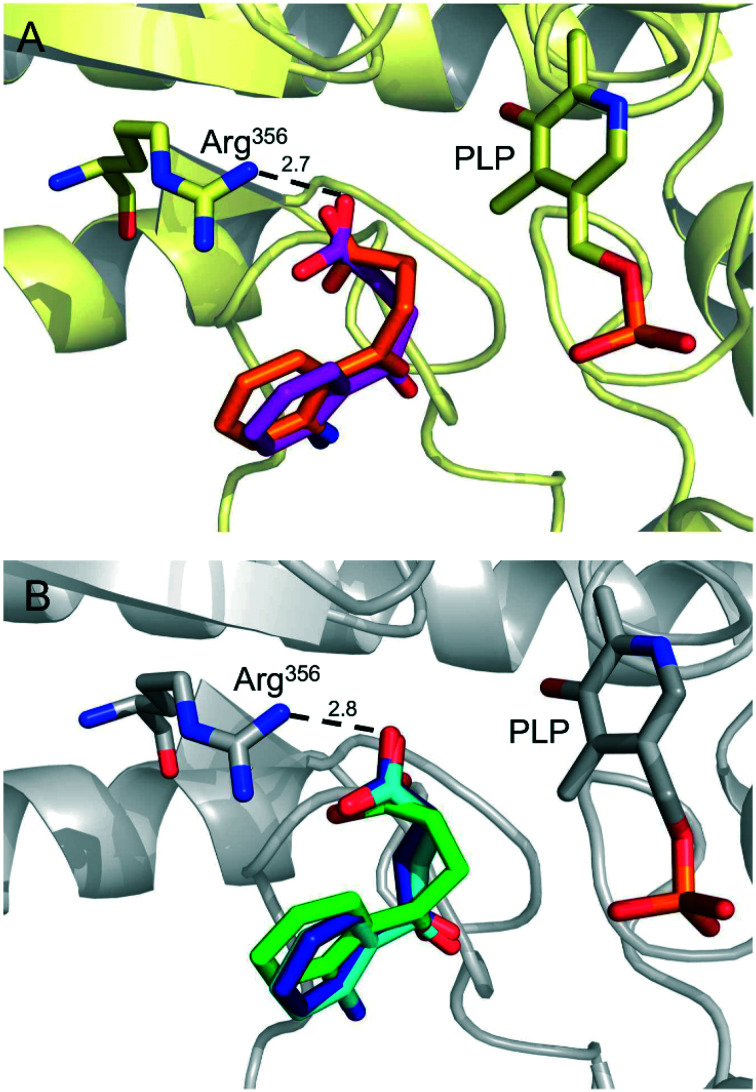

We have successfully determined the X-ray structure of AeHKT (PDB ID 6MFB) but we have struggled with twinned data sets from macromolecular crystallography experiments via soaking and cocrystallization procedures using several 1,2,4-oxadiazole compounds (manuscript in preparation). For this reason, molecular docking simulations were performed to investigate the binding mode and interactions between AeHKT and the present set of 1,2,4-oxadiazole compounds. We have validated our molecular docking protocol through redocking tests for the co-crystallized ligand 4-OB with both AgHKT and AeHKT X-ray structures. It should be noted that the two enzymes share a sequence identity of 79%. Ligand conformations resulting from these simulations were analyzed and compared to the crystallographic structure obtained for the 4-OB–AgHKT complex (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The 4-OB ligand binding modes in AgHKT and AeHKT active sites after the redocking procedure. (A) AgHKT in light yellow, showing the PLP cofactor and Arg356 residue (important for substrate and ligand binding and recognition). Co-crystallized 4-OB in orange and the lowest energy conformation from molecular docking calculations in purple. (B) AeHKT in grey, showing the PLP cofactor and Arg356 residue. Co-crystallized 4-OB in green and the lowest energy conformations (dark blue and cyan) from calculations started with the ligand placed outside the active site. Distances in angstroms.

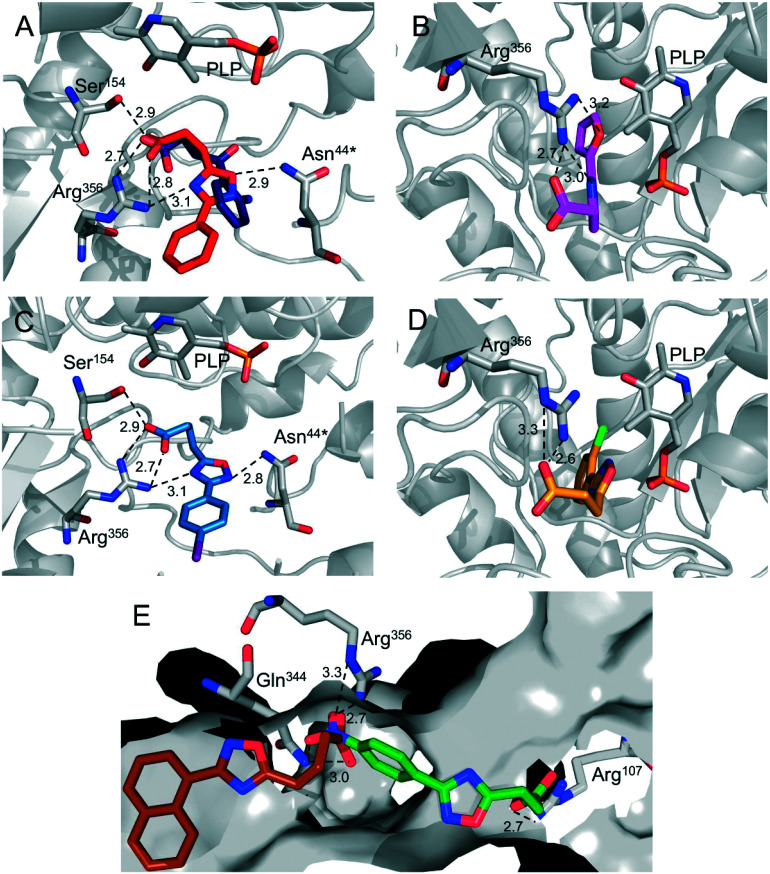

In addition to the nineteen sodium 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-propanoates reported here, eleven sodium 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-butanoates described by Maciel and colleagues were added to this set to evaluate their interactions with AeHKT at the atomic level.33 The 30 oxadiazole derivatives were placed in the active site, and after 200 generational runs with 2.5 × 106 evaluated interactions per generation, the lowest energy conformations and inhibition constants were analyzed. The canonical compounds for both series (4a and 6a) showed similar binding modes to Arg356, which is consistent with the experimental 4-OB binding mode (Fig. 5A). In these compounds, the residues Arg356/C, Ser154/C and Asn44/D interact through electrostatic and hydrogen bonding with the oxadiazole ring and the carboxylate, stabilizing the compounds in these lowest energy conformations. These are key residues for substrate and inhibitor recognition as described in the literature.37 In the binding conformation, the aromatic ring and its substituents point to the entry of the active site, allowing interactions with the residues located at this entry. Compounds 4a–4s, most of them with para substituents, exhibited similar conformation to 4a, with 4g and 4i being the exception. The electronegative/negatively charged substituents may be responsible for differences in their binding mode due to favorable electrostatic interactions with the positively charged residues Arg or Lys. Compounds 4n and 4o also showed different conformations compared to 4a. The exchange of the six-membered to five-membered ring resulted in a conformation with a 180-degree turn, suppressing the interactions with Ser154/C and Asn44/D (Fig. 5B). This behavior was also observed in all ortho-substituted compounds (Fig. 5D). The lowest energy conformation for these compounds is slightly different from that of 4a but still well placed in the active site.

Fig. 5. Calculated binding modes for oxadiazole derivatives in AeHKT active sites via molecular docking simulations. (A) The lowest energy conformation for compounds 4a (red) and 4-OB (dark blue), showing similar interactions with residues Arg356, Ser154 and Asn44. (B) The lowest energy conformation of compound 4n (pink), resulting in a conformation with a 180-degree turn in comparison to the canonical 4a. (C) The lowest energy conformation of compound 6i (blue), which is representative for most compounds of this series except for 6g. (D) All ortho-substituted compounds 4m, 4q and 4s (yellow) exhibited the lowest energy conformations similar to 4n, with the aromatic ring pointing to the inner side of the active site. (E) Compounds 6g and 4i displayed the lowest energy conformation outside of the active site, but still interacting with Arg356.

This search for compounds with short carboxylate linkers is consistent with our previous work, since the 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-propanoic derivatives (4a–4s) can display multiple conformations in the AgHKT active site, most of which are expected to be unproductive for inhibition.32

Nevertheless, most of the 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-butanoic derivatives (6a–6k) show similar conformation to the canonical 6a and the most active compound 6i (Fig. 5C), except for 6g. Considering that 6g is the bulkiest compound in this series and there is no difference in conformation for smaller substituents in para or meta positions (e.g.6e and 6f), steric effect is a plausive reason for this lowest conformation outside of the active site (Fig. 5E). Even so, the carboxylate portion is still interacting with Arg356 and Gln344 (residues located at the active site). The same happens to 4i, but here the nitro substituent is interacting with Arg356 and Gln344 instead of the carboxylate anion. The latter group is closer to another Arg residue (Fig. 5E). The competition between the nitro substituent and the carboxylate anion for interaction with Arg356 is not favorable to the stabilization of the compounds in the active site. Besides the previously described interactions, van der Waals forces play an important role at close range for stabilization and binding of these compounds in the AeHKT active site (ESI†).

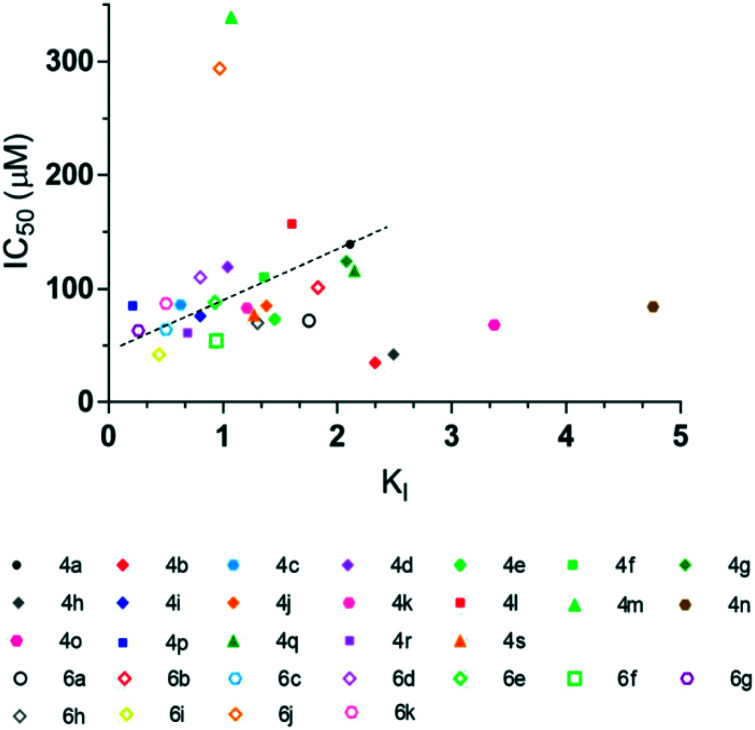

The calculated KI and measured IC50 values were compared to determine if these two measurements behave similarly, since for both, the lower the values, the better the inhibitor (Fig. 6). Although there is no clear-cut relationship between the calculated KI and experimentally measured IC50, most compounds with a low KI also exhibit a low IC50 and vice-versa (Fig. 6). Yet, a few outliers were observed, mostly within the oxadiazolyl-propanoic derivative set (i.e.4b, 4h, 4m, 4n, 4o). As previously reported,32 molecular docking calculations suggested that the oxadiazolyl-propanoic derivatives (4a–4s) do not bind to the active site of AeHKT in one single conformation as seen for oxadiazolyl-butanoic derivatives (6a–6k), but rather through multiple conformers. We have interpreted this pattern as indicative of less efficient inhibitory activity since some of the bound conformations will be unproductive and will require unbinding–rebinding to the active site in order to effect inhibitory action on the enzyme. However, due to the conformational diversity of the oxadiazolyl-propanoic derivatives, the calculated KI value, chosen for the lowest energy conformer of a given compound, will not be as representative of the diversity of conformations as it is for the conformationally more homogenous compounds. It should be noted, however, that a fairly proportional relation was observed for 24 of the 30 compounds, which indicates that chemical modifications of the 1,2,4-oxadiazole scaffold appear to enhance the inhibitory activity of AeHKT.

Fig. 6. Plot of inhibitory activity of the oxadiazole derivative sodium salts (IC50) versus estimated KI values. Compounds 4a–4s are shown as filled symbols, whereas compounds 6a–6k are shown as empty symbols. The shape of the symbols is equivalent to the position of the substitution (para, meta, ortho or other). The same substituents have matching colors for both series.

This demonstrates that better oxadiazole-based candidates for in vitro and in vivo HKT inhibition can be further developed and discovered for this new class of potential A. aegypti larvicides. Furthermore, we calculated the difference ΔKI between the calculated values of KI for the oxadiazole derivatives and for the lowest-energy docked conformation of 4-OB (Table 1). It can be seen that all 30 compounds exhibited a negative ΔKI, indicating that these oxadiazole derivatives can bind similarly or better than the co-crystallized inhibitor 4-OB in terms of estimated binding energy. The combined analysis of ΔKI values, binding modes in the AeHKT active site and experimental inhibitory activities places this set of 30 compounds as a prototype to design new compounds as AeHKT inhibitors with higher potency and specificity.

It should be noted that HKT is a functional ortholog of human kynurenine aminotransferases (KATs) which have been shown to catalyze the irreversible transamination of 3-HK to XA.37 Therefore, there is a concern that 1,2,4-oxadiazoles can undesirably inhibit these orthologs. However, it was previously shown that the 4-(2-aminophenyl)-4-oxobutyric acid (4-OB) inhibitor co-crystallized in the active site of AgHKT does not inhibit the human KAT I isozyme in the millimolar range.37 Given the extraordinary structural similarity of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles with 4-OB, it is reasonable to assume that the former will not bind efficiently to KATs. Furthermore, previous molecular docking calculations could not discriminate one single binding site in KAT I and KAT II for a canonical variant of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles.33 However, it is important to highlight that this series of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles are prototypes that will require further structural modifications for enhanced efficiency as well as selectivity for HKT. In addition, the anthropophilic behavior and great adaptability of A. aegypti to urban environments makes possible the use of oxadiazole-based larvicides in water-filled containers outside buildings which are used by the female mosquitoes to oviposition. For this purpose, high selectivity for HKT versus its human orthologs is desirable but not essential since ingestion by humans or higher animals would be accidental and in very small amounts (millimolar range). After overcoming first-pass metabolism and biological barriers, such a small amount is expected to exhibit considerably lower bioavailability. In addition, structurally related compounds have already shown toxicological safety in preliminary assays.30 Therefore, for use as synthetic larvicides, these compounds can be considered safe.

QSAR modeling

QSAR modeling was performed to investigate molecular descriptors related to the IC50 inhibitory activity, allowing better comprehension of biological activity, design, and prediction of new compounds to be synthesized. After OPS and systematic search algorithms, the selected variables of the best model are presented on Table 2, excluding the outlier compounds, 4m and 6j. These compounds were evaluated by the statistical method of “interquartile distances” in the range of the activities, revealing that they are true outliers.

Molecular descriptors selected after OPS/systematic search algorithms.

| Entry | Compound | pIC50 | HATS7i | RDF050m | RDF070u | G2u | H8m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a | 3.857 | 0.4429 | 3.6412 | 4.1757 | 0.1772 | 0.0213 |

| 2 | 4e | 4.137 | 0.3881 | 3.6746 | 5.3230 | 0.2119 | 0.0402 |

| 3 | 4d a | 3.924 | 0.4405 | 4.5166 | 4.5978 | 0.1772 | 0.0393 |

| 4 | 4b | 4.456 | 0.3092 | 4.1684 | 3.0959 | 0.2086 | 0.0338 |

| 5 | 4j | 4.071 | 0.4431 | 3.3415 | 3.9394 | 0.1772 | 0.0267 |

| 6 | 4l | 3.804 | 0.4622 | 3.7805 | 3.9770 | 0.1707 | 0.0163 |

| 7 | 4g | 3.907 | 0.3793 | 3.7471 | 5.0978 | 0.1772 | 0.0030 |

| 8 | 4k | 4.081 | 0.3907 | 3.9885 | 6.1007 | 0.1926 | 0.0355 |

| 9 | 4i | 4.119 | 0.4050 | 4.1037 | 6.7380 | 0.1951 | 0.0546 |

| 10 | 4p | 4.071 | 0.3368 | 7.9366 | 6.6552 | 0.1738 | 0.0005 |

| 11 | 4h a | 4.377 | 0.4145 | 7.6887 | 3.8661 | 0.2021 | 0.0311 |

| 12 | 4c | 4.066 | 0.3871 | 3.6384 | 5.3099 | 0.2008 | 0.0179 |

| 13 | 4n | 4.076 | 0.3978 | 1.7998 | 2.8134 | 0.1832 | 0.0042 |

| 14 | 4o a | 4.167 | 0.3847 | 3.3366 | 2.6781 | 0.2110 | 0.0029 |

| 15 | 4f | 3.959 | 0.4013 | 3.1145 | 6.5438 | 0.1722 | 0.0245 |

| 16 | 4q | 3.936 | 0.3954 | 1.9689 | 5.2898 | 0.2008 | 0.0203 |

| 17 | 4r | 4.215 | 0.3927 | 3.6949 | 4.8954 | 0.1772 | 0.0118 |

| 18 | 4s a | 4.114 | 0.4030 | 4.3525 | 4.3739 | 0.1772 | 0.0161 |

| 19 | 6a | 4.143 | 0.4312 | 5.0707 | 4.2567 | 0.1830 | 0.0015 |

| 20 | 6b | 3.996 | 0.3169 | 4.5514 | 6.9781 | 0.1667 | 0.0041 |

| 21 | 6c | 4.194 | 0.3751 | 6.6453 | 5.4440 | 0.2119 | 0.0043 |

| 22 | 6d | 3.959 | 0.4185 | 7.6206 | 7.6289 | 0.1722 | 0.0016 |

| 23 | 6e | 4.056 | 0.3953 | 3.8126 | 6.9982 | 0.2397 | 0.0018 |

| 24 | 6f | 4.268 | 0.3704 | 6.9577 | 6.4733 | 0.2027 | 0.0004 |

| 25 | 6g | 4.201 | 0.2983 | 8.1453 | 7.5686 | 0.1643 | 0.0082 |

| 26 | 6h | 4.155 | 0.4151 | 8.8637 | 5.2402 | 0.1679 | 0.0019 |

| 27 | 6i | 4.377 | 0.4129 | 9.3951 | 5.4779 | 0.2678 | 0.0014 |

| 28 | 6k | 4.060 | 0.3974 | 3.9394 | 5.4625 | 0.2397 | 0.0017 |

| Correlation matrix | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HATS7i | RDF050m | RDF070u | G2u | H8m | |

| HATS7i | 1 | 0.223 | 0.339 | 0.043 | 0.080 |

| RDF050m | — | 1 | 0.445 | 0.075 | 0.456 |

| RDF070u | — | — | 1 | 0.015 | 0.132 |

| G2u | — | — | — | 1 | 0.036 |

| H8m | — | — | — | — | 1 |

Test set.

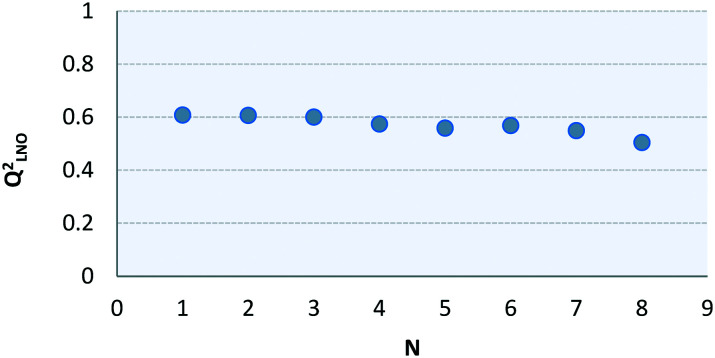

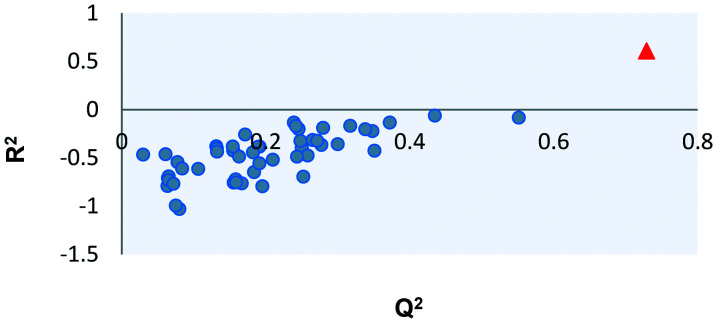

Thus, these samples were disregarded from the QSAR modeling. In the same table, a correlation matrix is displayed based on the training set, showing a weak correlation between the selected descriptors (<0.6). The regression vector is shown below with the respective regression coefficients:pIC50 = −1.8894 (±1.0232) HATS7i + 0.0449 (±0.0229) RDF050m − 0.0554 (±0.0347) RDF070u + 2.4498 (±1.4924) G2u + 2.9769 (±2.9260) H8m + 4.3958 (±0.5623)The values of some validation parameters attested to a good degree of robustness and predictability for the model: R2 = 0.73; Q2LOO = 0.61; Q2EXT = 0.77. Results of leave-N-out cross-validation analysis (Q2LNO) can be visualized in Fig. 7, showing that the values fluctuate around 0.1 from the Q2LOO value, which is a good profile.

Fig. 7. Leave-N-out cross-validation results.

The Y-scrambling results are displayed in Fig. 8 and show validation parameters for the scrambled models (blue dots) and for the original valid model (red triangle). In this analysis, 50 shuffles were performed only on the Y column and models were built from these new matrices, which must have poor validation parameters if there is no random correlation between Y and X. Once again, we can observe the success of this analysis, where most false models show values smaller than 0.4.

Fig. 8. Y-scrambling results (blue dots: results for scrambled models; red triangle: results from the original model).

The physical sense of the molecular descriptors and a structure–activity relationship, from a qualitative standpoint, is essential to understand the QSAR analysis. Taking into account the nature and interpretation of the selected variables, a compilation of these parameters is presented below. It is noteworthy to highlight that the analysis was performed individually, but it is the descriptor's overall contribution that is responsible for model predictability.

HATS7i: It is part of the GETAWAY descriptors (GEometry, topology, and atom-weights assemblY), which are derived from the molecular influence matrix (H).38 This matrix is constructed starting from the geometric distance matrix (M) between all the atoms in a structure, containing three columns regarding the x, y and z coordinates and rows corresponding to the total number of the atoms. Then, the matrix is obtained by H = M·(MT·M)−1·MT.39 The generic descriptor HATSkw implies that k is the lag of the 1–8 bonds between two atoms i and j, and w corresponds to the weighting scheme. Thus, the descriptor can be calculated as: where δ(k; dij) is the Kronecker delta, i.e. δ(k; dij) = 1, if the ijth entry in the topological level matrix is = k, and δ(k; dij) = 0.39 For the HATS7i, the w parameter is the ionization potential (IP) of the atoms, in a lag of seven (k) bonds. The regression coefficient in the QSAR equation is negative, indicating that higher values for this descriptor decrease pIC50 and, subsequently, the activity. This means that atoms with higher ionization potentials at a distance of seven bonds tend to decrease biological activity. We can take as example compounds 4b, 6b (p-methoxy substituted) and 4l (m-methoxy substituted). The former two compounds have the oxygen from the methoxy group at a distance of seven bonds of the oxadiazolyl oxygen. On the other hand, compound 4l has the oxygen from the methoxy group at a lag of seven bonds of oxygen or nitrogen of the oxadiazole ring, even in different combinations. Then, the descriptor value for 4l is higher and the inhibitory activity is worse. It is indicative that a substitution at the para position of the aromatic ring is preferable, including specific relationships in this position for other atoms with considerable IP (halogens).

where δ(k; dij) is the Kronecker delta, i.e. δ(k; dij) = 1, if the ijth entry in the topological level matrix is = k, and δ(k; dij) = 0.39 For the HATS7i, the w parameter is the ionization potential (IP) of the atoms, in a lag of seven (k) bonds. The regression coefficient in the QSAR equation is negative, indicating that higher values for this descriptor decrease pIC50 and, subsequently, the activity. This means that atoms with higher ionization potentials at a distance of seven bonds tend to decrease biological activity. We can take as example compounds 4b, 6b (p-methoxy substituted) and 4l (m-methoxy substituted). The former two compounds have the oxygen from the methoxy group at a distance of seven bonds of the oxadiazolyl oxygen. On the other hand, compound 4l has the oxygen from the methoxy group at a lag of seven bonds of oxygen or nitrogen of the oxadiazole ring, even in different combinations. Then, the descriptor value for 4l is higher and the inhibitory activity is worse. It is indicative that a substitution at the para position of the aromatic ring is preferable, including specific relationships in this position for other atoms with considerable IP (halogens).

RDF050m and RDF070u: These descriptors are related to the radial distribution function in the molecular scaffold.38,39 The first one means the probability of finding an atom in a spherical volume of radius 50.0 Å, weighted by the atomic mass, the second one, in a radius of 50.0 Å, unweighted.38 RDF050m has a positive regression coefficient, while RDF070u has a negative one. Thus, the former indicates that atoms with higher mass in the molecular scaffold tend to contribute positively to activity, in contrast to the latter, which indicates that a greater number of atoms in the structure's periphery tends to decrease activity. In other words, heavier atoms as substituents contribute positively to biological activity. Compounds 4h, 6h and 6i are good examples that explain this archetype, presenting a high value for the first descriptor and a low value for the second one. These three compounds display heavy substituents at the para position of the aromatic moiety.

G2u: The second component symmetry directional WHIM index/unweighted. WHIM descriptors capture relevant molecular 3D information.38,39 A principal component analysis is performed centered on Cartesian coordinates of a compound by using a weighted covariance matrix.39 In this specific case, the descriptor has a positive regression coefficient, indicating that higher values tend to increase the activity. Compounds 4e, 6e, 6i and 6k, all presenting high values for this descriptor, are para-substituted compounds.

H8m: H autocorrelation of lag 8/weighted by atomic masses.38 It is also a GETAWAY descriptor, as the HATS7i, obtained by the equation: where δ(k; dij; hij) = 1 if dij = k (in the topological level matrix) and hij > 0 (considering the H matrix), and zero otherwise.39 This way, heavier atoms at a distance of eight bonds increase the value of this descriptor, which has a positive regression coefficient. Compound 4i has the highest value due to the nitro substitution in the para position, allowing the combination of oxygen from this group with the heavy atoms of the oxadiazole ring, thus increasing the value. The para-CF3 substituted compound, 4h, follows the same trend, but with a higher value on this descriptor. On the other hand, compound 4p has a very low value, and it presents the nitro substituent on the meta position of the aromatic ring.

where δ(k; dij; hij) = 1 if dij = k (in the topological level matrix) and hij > 0 (considering the H matrix), and zero otherwise.39 This way, heavier atoms at a distance of eight bonds increase the value of this descriptor, which has a positive regression coefficient. Compound 4i has the highest value due to the nitro substitution in the para position, allowing the combination of oxygen from this group with the heavy atoms of the oxadiazole ring, thus increasing the value. The para-CF3 substituted compound, 4h, follows the same trend, but with a higher value on this descriptor. On the other hand, compound 4p has a very low value, and it presents the nitro substituent on the meta position of the aromatic ring.

Considering the analysis exposed above for the oxadiazole series described herein, we can summarize that compounds presenting heavy atoms as substituents at the para position of the aromatic ring have an inclination to be more active as HKT antagonists. These findings were validated by a mathematical model depicted in this work, which allows for a better understanding of structure–activity relationships and can be used in the future for synthetic approaches.

Experimental

Synthesis and characterization of oxadiazole salts – general methods

The reactions were monitored by TLC analysis with TLC plates containing GF254 from E. Merck©. Compounds were characterized using an Electrothermal Mel-Temp© apparatus to determine the melting points. NMR spectra were recorded using a Varian Unity Plus 300 MHz or a Varian UNMRS 400 MHz spectrometer. Infrared spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu model IR Prestige-21 FT-IR instrument using KBr pellets. The exact mass of the synthesized compounds was obtained on a MALDI-TOF Autoflex III Mass Spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) with a 355 nm wavelength Nd:YAG laser at a frequency of 100 Hz. An external matrix consisting of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg mL−1) in 50% acetonitrile and 0.3% trifluoroacetic acid was used. Arylamidoximes were synthesized as described in the literature.40

Synthesis of 3-(3-aryl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl) propanoic acids

Succinic anhydride (30 mmol) and the corresponding arylamidoxime (20 mmol) were put in a round-bottom flask in an oil-bath at 473 K. After one hour, the end of the reaction was verified by TLC analysis in a 7 : 3 hexane/ethyl acetate mobile phase. Then, saturated NaHCO3 solution (10 mL) and 10 mL of dichloromethane were added to the cold flask and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight. After the phase separation, the aqueous phase was acidified until precipitation of the title compound occurred and then dissolved in dichloromethane, dried over Na2SO4 and recrystallized from a mixture of chloroform and hexane. The substances 3a–3e, 3g, 3h, 3j, 3p, 3r (ref. 27) and 3f, 3i, 3m, 3o (ref. 28) were synthesized previously and their data were compared to previous literature.

3-[3-(4-Trifluormethylphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]-propanoic acid (3h) (3.53 g, 62%); mp 110–112 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 3.02 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.27 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 7.73 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz Harom); 8.18 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz, Harom); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 21.7; 30.1; 122.3; 125.0; 125.8; 125.8; 127.7; 130.0; 133.1; 167.3; 176.8; 178.6. MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 285.1118 (calcd for C12H9F3N2O3 [M − H]+: 285.0487).

3-[3-(2-Furyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]- propanoic acid (3n) (2.58 g, 63%), mp 118–120 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.99 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2); 3.23 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz, CH2); 7.11 (dd, 1H, J = 4.4; 4.4 Hz, Harom); 7.67 (s, 2H, Harom).13C (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 21.6; 30.0; 111.8; 113.8; 141.9; 145.2; 161.2; 176.5; 178.2. MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 209.6012 (calcd for C9H8N2O4 [M + H]+: 209.0562).

4-[3-(3-Nitrophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)- propanoic acid (3p) (4.2 g, 80%); mp 121–122 °C (from CHCl3). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 3.04 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.29 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 7.68 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Harom); 8.36 (d, 2H, J = 8.40 Hz, Harom); 8.91 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 21.7; 29.9; 122.6; 125.7; 128.5; 130.0; 133.0; 166.7; 175.7; 178.9. MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 262.1154 (calcd for C11H8N3O5 [M − H]+: 262.0464).

3-[3-(2-Fluorphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]- propanoic acid (3q) (2.5 g, 53%); mp 83–85 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 3.02 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2); 3.29 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2); 7.29–7.20 (m, 2H, Harom); 7.25–7.46 (m, 1H, Harom); 8.02–8.06 (m, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 21.6; 30.2; 116.8; 124.4; 130.7; 132.8; 159.4; 161.9; 165.1; 176.8; 177.7. MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 237.7582 (calcd for C11H9FN2O3 [M + H]+: 237.0669).

3-[3-(2-Chlorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]- propanoic acid (3s) (3.68 g, 73%); mp 78–80 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 3.02 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.30 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 7.35–7.45 (m, 2H, Harom); 7.53 (dd, 2H, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, Harom); 7.90 (dd, 1H, J = 7.2; 2.0 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 21.6; 30.2; 125.8; 126.4; 130.8; 131.6; 131.7; 133.4; 167.0; 176.9; 177.6. MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 252.7416 (calcd for C11H9ClN2O3 [M + H]+: 253.0374).

Synthesis of sodium 3-(3-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl) propionic salts

In a round-bottom flask, the respective 4-(3-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)propionic acid (1 mmol) and 4.8 mL of 1% NaOH methanol solution (freshly prepared) were mixed and the reaction was stirred for one hour at room temperature. After that, the methanol was evaporated and the product was recrystallized from chloroform.

Sodium 3-(3-phenyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)propanoate (4a) (0.22 g, 93%); mp 171–172 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.56 (t, 2H, J = 7.35 Hz, CH2); 2.98 (t, 2H, J = `7.35 Hz, CH2); 7.32–7.44 (m, 3H, Harom); 7.66 (d, 2H, J = 7.80 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.0; 33.0; 125.2; 126.9; 129.0; 131.6; 167.4; 179.6; 180.6. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2925 (C–Harom); 1691 (C O); 1582 (C N); 1205 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 241.0707 (calcd for C11H9N2NaO3 [M + H]+: 241.0583.

Sodium 3-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4b) (0.25 g, 92%); mp 214–215 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.63 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2); 3.07 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2); 3.77 (s, 3H, CH3); 6.98 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom); 7.76 (dd, J = 8.7 Hz,1.8 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 20.8; 30.8; 53.2; 112.1; 115.7; 126.5; 159.2; 164.9; 177.5; 178.2. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2966 (C–Harom); 1609 (C O); 1423 (C N); 1237 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 271.1074 (calcd for C12H11N2NaO4 [M + H]+: 271.0689.

Sodium 4-[3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4c) (0.3 g, 98%); mp 270–272 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.77 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 3.23 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 7.40 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom); 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom); 7.64 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.1; 125.1; 126.2; 128.3; 130.8; 132.4; 134.9; 165.6; 179.5; 181.0. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2925 (C–Harom); 1692 (C O); 1582 (C N); 1272 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 308.7603 (calcd for C11H7Cl2N2NaO3 [M + H]+: 308.9804).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-bromophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4d) (0.29 g, 90%); mp 238–240 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.62 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 3.06 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 7.36 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz Harom); 7.43 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.0; 124.1; 125.4; 128.4; 131.9; 166.7; 179.6; 180.8. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2943 (C–Harom) 1589 (C O); 1473 (C N); 1195 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 318.8952 (calcd for C11H8BrN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 319.0866).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-tolyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4e) (0.25 g, 98%); mp 179–180 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3); 2.54 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 2.95 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 7.11 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom); 7.50 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 20.5; 22.9; 32.9; 122.2; 126.8; 129.5; 142.5; 167.3; 179.6; 180.4. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2939 (C–Harom); 1650 (C O); 1561 (C N); 1223 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 255.0982 (calcd for C12H11N2NaO3 [M + H]+: 255.0740).

Sodium 3-[3-(3-tolyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4f) (0.24 g, 93%); mp 95–97 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.70 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz, CH2); 3.12 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz, CH2); 7.33–7.37 (m, 3H, Harom); 7.56 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 20.3; 23.0; 33.0; 123.9; 125.1; 127.3; 128.8; 132.3; 139.1; 167.4; 179.6; 180.8. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2946 (C–Harom); 1691 (C O); 1589 (C N); 1216 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 254.7474 (calcd for C12H11N2NaO3 [M]+: 254.0661).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-fluorphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4g) (0.25 g, 96%); mp 190–192 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.58 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 3.02 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 7.02–7.07 (m, 2H, Harom); 7.61–7.66 (m, 2H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 22.9; 33.0; 115.8; 116.1; 121.56; 121.6; 129.3; 129.4; 162.7; 166.0; 166.7; 179.6, 180.8. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2939 (C–Harom); 1608 (C O); 1554 (C N); 1241 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 259.0794 (calcd for C11H8FN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 259.0489).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4h) (0.3 g, 98%); mp 194–195 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.66 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 3.13 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 7.73 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz Harom); 7.96 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.1; 125.4; 127.4; 128.8; 132.4; 166.5; 179.6; 181.2. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2939 (C–Harom); 1568 (C O); 1437 (C N); 1320 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 309.0762 (calcd for C12H8F3N2NaO3 [M + H]+: 309.0457).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4i) (0.28 g, 97%); mp 225–226 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.67 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.15 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 8.05 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom); 8.25 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.1; 124.1; 128.2; 131.6; 148.9; 166.2; 179.7; 181.6. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2925 (C–Harom); 1589 (C O); 1506 (C N); 1306 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 284.0463 (calcd for C11H8N3NaO5 [M − H]+: 284.0277).

Sodium 3-[3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4j) (0,26 g, 97%); mp 217–218 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.64 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.10 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 7.40 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom); 7.73 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 20.9; 30.9; 121.6; 126.2; 126.8; 134.8; 164.5; 177.4; 178.7. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2962 (C–Harom); 1589 (C O); 1423 (C N); 1195 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 275.0217 (calcd for C11H8ClN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 275.0193).

Sodium 3-[3-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4k) (0.27 g, 94%); mp 185–186 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.62 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 3.07 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 5.94 (s, 2H, OCH2O); 6.86 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Harom); 7.23 (d, 1H, J = 1.2 Hz, Harom); 7.36 (dd,1H, J = 8.7 Hz,1.2 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 20.8; 30.9; 99.7; 104.6; 106.5; 116.8; 120.0; 145.3; 147.7; 164.9; 177.5; 178.3. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2902 (C-Harom); 1582 (C O); 1458 (C N); 1230 (N–O); 1023 (C–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 284.7558 (calcd for C12H9N2NaO5 [M]+: 284.0403.

Sodium 3-[3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4l) (0,21 g, 76%); mp 148–150 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.64 (t, 2H, J=7.35 Hz, CH2); 3.09 (t, 2H, J = 7.35 Hz, CH2); 3.76 (s, 3H, OCH3); 7.05 (dd, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz; 1.2 Hz, Harom); 7,33–7,44 (m, 3H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 14.6; 20.9; 30.9; 37.0; 53.2; 109.6; 115.3; 117.5; 124.4; 128.2; 156.8; 165.1; 177.5; 178.5; 180.2. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2953 (C–Harom); 1582 (C O); 1452 (C N); 1230 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 271.0772 (calcd for C12H11N2NaO4 [M + H]+: 271.0689).

Sodium 3-[3-(2-tolyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4m) (0.23 g, 92%) mp 170 °C (dec.) 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.31 (s, 3H, CH3); 2.63 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2); 3.08 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH2); 7.22–7.37 (m, 3H, Harom); 7.56 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 18.0; 20.8; 30.9; 32.0; 122.7; 123.9; 127.4; 128.9; 130.0; 135.7; 165.8; 177.5; 177.8. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2973 (C–Harom); 1575 (C O); 1444 (C N); 1195 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 254.7268 (calcd for C12H11N2NaO3 [M]+: 254.0661).

Sodium 3-[3-(2-furyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4n) (0.12 g, 51%) mp 239–240 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.77 (t, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz, CH2); 3.22 (t, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz, CH2); 6.70 (s, 1H, Harom); 7.18 (s, 1H, Harom); 7.76 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O) δ (ppm): 22.9; 32.9; 34.2; 112.0; 114.5; 140.8; 146.1; 160.3; 179.7; 180.9. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2910 (C–Harom); 1635 (C O); 1549 (C N); 1222 (N–O); 1024 (C–O–C). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 230.7160 (calcd for C9H7N2NaO4 [M]+: 230.0298).

Sodium 3-[3-(2-thiophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4o) (0.24 g, 96%); mp 188–190 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.73 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 3.16 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2); 7.20 (dd, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz, 4.2 Hz, Harom); 7.67 (s, 2H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.0; 33.0; 126.4; 128.2; 130.1; 130.4; 163.4; 179.6; 180.7. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2925 (C–Harom); 1572 (C O); 1417 (C N); 1313 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 247.0458 (calcd for C9H7N2NaO3S [M + H]+: 247.0147).

Sodium 3-[3-(3-nitrophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4p) (0.27 g, 96%); mp 202–203 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.88 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 3.33 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2); 7.73 (dd, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, 8.4 Hz, Harom); 8.20 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Harom), 8.34 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom), 8,53 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.0; 121.7; 126.0; 126.9; 130.5; 133.1; 147.7; 166.0; 179.6; 181.5. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2953 (C–Harom); 1592 (C O); 1506 (C N); 1327 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 284.0625 (calcd for C11H8N3NaO5 [M − H]+: 284.0277).

Sodium 3-[3-(2-fluorphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4q) (0.22 g, 86%); mp 170–172 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.75 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 3.20 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 7.21–7.31 (m, 2H, Harom); 7.52–7.58 (m, 1H, Harom); 7.80 (dd, 1H, J = 7.2; 7.5 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 22.9; 33.1; 34.2; 113.3; 116.6; 124.7; 130.0; 133.6; 158.3; 161.6; 164.2; 179.6; 180.2. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 3049 (C–Harom); 1685 (C O); 1596 (C N); 1285 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 259.1279 (calcd for C11H8FN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 259.0489.

Sodium 3-[3-(3-bromophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4r) (0.20 g, 62%); mp 118–120 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.75 (t, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2); 3.19 (t, 2H, J = 7.35 Hz, CH2); 7.26 (dd, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz; 7.5 Hz, Harom); 7.53 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom); 7.64 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, Harom); 7.74 (s, 1H, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 75 MHz) δ (ppm): 23.1; 33.1; 122.2; 125.6; 127.0; 129.5; 130.6; 134.3; 166.2; 179.6; 180.8. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2939 (C–Harom); 1671 (C O); 1561 (C N); 1202 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 318.7591 (calcd for C11H8BrN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 318.9688).

Sodium 3-[3-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]propanoate (4s) (0.27 g, 98%); mp 118–120 °C. 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.61 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2); 3.06 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz, CH2); 7.23–7.36 (m, 3H, Harom); 7.53 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, Harom). 13C NMR (D2O, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 22.9; 33.0; 34.2; 124.4; 127.3; 130.6; 131.3; 132.4; 166.2; 179.6; 180.3. FT-IR (KBr pellet) νmáx/cm−1: 2944 (C–Harom); 1721 (C O); 1558 (C N); 1292 (N–O). MALDI-TOF HRMS m/z: 274.6786 (calcd for C11H8ClN2NaO3 [M + H]+: 274.6355).

Biochemical assay

The methodology was developed by our research group in a previous work.33,35 Stock solutions were freshly prepared, except for 3-hydroxy-d,l-kynurenine (3-d,l-HK) which was kept at −20 °C. 3-d,l-HK and sodium pyruvate were directly diluted in 200 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5/100 mM NaCl, while 20 mM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) was first dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH and then diluted in HEPES/NaCl buffer until a concentration of 0.5 mM is obtained. A solution of 20 mM xanthurenic acid was prepared in 0.1 M NaOH to perform calibration curves. The reactions were carried out in a 96-well round-bottom microplate containing 8 μL of 25 mM 3-d,l-HK, 8 μL of 0.5 mM PLP and 4 μL of 50 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 μg of recombinant AeHKT and HEPES/NaCl buffer to a 100 μL final volume. The plates were incubated at 50 °C for 5 minutes and then 100 μL of 10 mM FeCl3·6H2O in 0.1 M HCl was added to interrupt the reaction and generate the XA–Fe3+ complex. The temperature (30–70 °C) and pH (6–10) of the AeHKT enzyme were evaluated to establish optimum conditions, and kinetic parameters were estimated in our previous work.33 Mixes were prepared to avoid differences between replicates. Samples were performed in duplicate and absorbances were read at 570 nm. All the data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism7.0 software package using the Michaelis–Menten equation. Kinetics and inhibition parameters were determined by non-linear regression.

Inhibition assays

The inhibition assays were performed with pre-incubation of each compound in five concentrations ranging from 500 μM to 50 μM with PLP and AeHKT. To achieve this, solution mixes were prepared to ensure that the same amount of enzyme and co-factor was present in the different inhibitor concentrations. Blank samples and negative controls were incubated at the same time as the samples. After 30 minutes of incubation at 50 °C, the samples were mixed with the other reaction components and the assays were performed as described in the Biochemical assay subsection. All compounds tested were diluted in 200 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5/100 mM NaCl and the samples were evaluated in duplicate. In each test, the negative control was added to calculate the activity percentage.

Molecular docking procedure

Molecular docking calculations were performed as described in our previous studies.32,33 The programs AutoGrid v.4.0 and AutoDock v.4.0 were used during these calculations.41,42 The protein structure was treated as rigid, while the ligands were treated flexibly. Atomic coordinates of the AeHKT crystal structure in its holo form were retrieved from PDB (ID 6MFB). Polar hydrogens were added to the protein considering amino acid protonation states at pH 7. Partial charges for protein atoms were assigned according to AMBER86 force field parameters,43 while PLP and ligand charges were assigned using the Gasteiger method,44 ensuring that all residues have presented integer charges. The AMBER86 atom types were assigned to all atoms.43 Overall, 30 oxadiazole derivatives were evaluated in terms of binding affinity to AeHKT in a complex. In addition to the sodium 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-propionates reported here, the eleven sodium 1,2,4-oxadiazolyl-butanoates described by Maciel and colleagues were docked in the AeHKT active site.33 Aiming at the reproducibility of the present docking protocol, redocking experiments were conducted in three steps: (i) docking of co-crystallized 4-OB in the AgHKT active site (PDB ID 2CH2);37 (ii) docking of co-crystallized 4-OB in the AeHKT active site; and (iii) docking of co-crystallized 4-OB in AeHKT partially outside the active site, all sampled through 200 generation cycles. The C monomer was arbitrarily chosen to perform the docking calculations in both enzymes. A grid with dimensions of 28 × 28 × 28 Å and spacing of 0.22 Å was centered at the co-crystallized ligand 4-OB, located at the active site. The binding modes for all the ligands were predicted based on affinity maps generated by AutoGrid v4.0. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm45,46 was employed in all molecular dockings with the following parameters:45,46 an initial population of 150 individuals per generation, a maximum number of 27 000 generations, and a total of 2.5 × 106 energy evaluations per generation. Thus, a total of 4.05 × 106 conformations for each of the ligands were generated in each of the 200 steps of the simulation. An elitism rate of 1 was applied to ensure that the top individual always survives into the next generation in conjunction with mutation and crossover rates of 0.02 and 0.08, respectively. In the local search, 300 steps were applied with a 0.06 probability of search for one individual. Ligand conformations presenting the most favorable binding energy were selected in each step of the simulation in such a way that at the end of the calculation, atomic coordinates of the 200 conformers that better fitted the binding site were selected. The final lowest energy structures were clustered based on a RMS positional deviation of 2.0 Å. These structures were examined, and the figures were generated by PyMOL.47 Final atomic coordinates for docked complexes are available in the ESI.†

QSAR methods

The 3D geometry of the compounds was obtained from the lowest energy conformations of the docking results. Molecular descriptors of diverse nature (1D, 2D and 3D) were generated by the Dragon® software,38 providing an initial matrix of 5.000 descriptors. This amount was initially reduced by a cutoff of min = 0.1 in the standard deviation and a correlation of <0.9 between the variables. After this process, 781 variables remained.

An initial analysis was performed in the IC50 values, where two samples with very different values were detected: compounds 4m and 6j. Statistical analysis of interquartile distances reveals that they behave as outliers. Considering the 30 IC50 values; taking the median, the first (Q1) and third (Q3) interquartile values (84.5, 68 and 110, respectively) as well as calculating the interquartile range (IQR = 42), the calculation of the limits for the possible lower and upper outliers were, respectively: Q1 − 1.5 × (IQR) and Q2 + 1.5 × (IQR). These calculations resulted in values of 5 and 173 for the lower and the upper limits, respectively. In this way, we verified that none of the samples showed a value smaller than 5 and the two evidenced compounds showed values greater than 173 (4m and 6j). Thus, these samples were not considered for the QSAR analysis.

The original IC50 values were then converted to −log(IC50), or pIC50, reducing the standard deviation so the highest values correspond to the best activities. The descriptor matrix of the 28 compounds was submitted to a variable selection procedure using the ordered predictor selector (OPS) algorithm48 implemented in the QSAR modeling free software.49 This algorithm performs the construction of incremental partial least squares (PLS) models, starting from a reordering of the original descriptor matrix, using the X variables most correlated with the Y variable in the first columns.48,50 Considering the specific parameters used for this work, the incremental models started from the first 10 reordered columns, increasing by a factor of 5, with a maximum of 30% of the total variables. At the end, the best models were presented chosen by the standard deviation of the prediction error sum of squares (SPRESS)48,51 value calculated for each incremental set of variables. After OPS, the original matrix was reduced to 30 descriptors. In this step, training and test sets were randomly chosen, considering 4d, 4h, 4o, and 4s for the test compounds and the remaining 24 compounds for the training set.

The training set was submitted to a new variable selection using the systematic search algorithm implemented in the Build QSAR program.52 At the end, five descriptors were selected in a multiple linear regression (MLR) model, considering the recommended 1 : 5 ratio between descriptors and compounds.53

The validation parameters53 for the model were defined as R2 values (the coefficient of determination for calibration); Q2LOO (the coefficient of determination for leave-one-out cross validation); Q2LNO (the coefficient of determination for leave-N-out cross validation); Q2EXT (the coefficient of determination for external validation) and the results of Y-scrambling. The first two and the Q2EXT parameters were obtained based on the standard equations. The Q2LNO results were expressed in a plot as the means of 10 random runs in each N chosen – which was from one to eight samples taken – considering the training set. For the Y-scrambling procedure, the dependent variable column was mixed 50 times to build alternative models and determine R2 and Q2LOO for them.53 If the descriptors used in the modeling do not correspond to a random correlation with the activity, it is expected for most values of the models with scrambled Y to be calculated with a value smaller than 0.4.

Conclusions

Nineteen sodium 3-[3-(aryl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]-propanoates were synthesized and obtained in yields ranging from 51% to 98% and comprise a second generation of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles planned to act as Aedes aegypti larvicides. These salts were tested for A. aegypti HKT inhibition and from this reaction, it was possible to conclude that these compounds are part of a new class of HKT inhibitors. Compounds containing p-anisoyl and p-trifluoromethylphenyl groups exhibited the best IC50 values, 35.0 and 42.3 mM, respectively. These results showed that inhibitors with high electron density substituents have lower IC50 values and therefore are more promising candidates for inhibitors of the HKT from A. aegypti. Inhibition assays showed that the synthesized salts are competitive inhibitors of the enzyme, promoting accumulation of the toxic metabolite 3-HK in the reaction medium.

Molecular docking calculations provided a 3D map of essential interactions for the molecular recognition of the 30 oxadiazole derivatives by HKT with a diverse repertoire of side chains and aromatic ring substituents. Although some derivatives showed lowest energy conformations slightly different from that of the AgHKT co-crystallized inhibitor 4-OB, the most promising compounds with para substituents showed similar conformation and interaction with the Arg356 residue. Remarkably, all 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives docked exhibited an estimated KI smaller than the corresponding value for 4-OB under the same simulation conditions. This finding indicates that this class of compounds has great potential as prototypes for the design of new HKT inhibitors with greater potency and specificity.

The QSAR modeling revealed five molecular descriptors that could explain the variability in oxadiazole biological responses. From a qualitative viewpoint, compounds presenting heavy atoms as substituents on the para position of the aromatic ring tend to be more active. The equation can be used to predict compounds not yet tested, considering the general adjustment of the numerical information provided by the molecular descriptors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew Oliveira and Dr. Rafael Guido for the collaboration in cloning, expression and purification experiments of recombinant HKT and also Dr. Tatiany Romão and Dr. Maria Helena Neves for the use of the spectrophotometer and providing the DNA samples to achieve the cloning step. Financial support for this research project was provided by the Brazilian funding agencies FACEPE (APQ-0732-1.06/14), BioMol/CAPES (BioComp 23038.004630/2014-35), INCTFx/CNPq (465259/2014-6) and FAPESP (2013/07600-3). TAS acknowledges CNPq for a productivity fellowship.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00305k

Notes and references

- Musso D. Gubler D. J. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:487–524. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00072-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini G., Landini M. P. and Sambri V., in Chikungunya Virus: Methods and Protocols, ed. J. J. H. Chu and S. K. Ang, Springer Science+Business Media, New york, 2016, vol. 1426, pp. 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuera A. Ramírez J. D. Acta Trop. 2019;190:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt D. J. Miner J. J. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses J. D. A. Ishigami A. C. de Mello L. M. de Albuquerque L. L. de Brito C. A. A. Cordeiro M. T. Pena L. J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;64:1302–1308. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Situation report: Zika virus, microcephaly, Guillain-Barré Syndrome, 10 march 2017, 2017

- PAHO/WHO, Zika cases and congenital syndrome associated with Zika virus reported by countries and territories in the Americas, 2015–2018. Cumulative cases, https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=43297&lang=en, (accessed 8 July 2020)

- Mead P. S. Duggal N. K. Hook S. A. Delorey M. Fischer M. Olzenak McGuire D. Becksted H. Max R. J. Anishchenko M. Schwartz A. M. Tzeng W.-P. Nelson C. A. McDonald E. M. Brooks J. T. Brault A. C. Hinckley A. F. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1377–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira J. Peixoto T. M. Siqueira A. M. Lamas C. C. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017;23:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A. C. Zielinski-Gutierrez E. Scott T. W. Rosenberg R. PLoS Med. 2008;5:0362–0366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyston P. Robinson K. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012;61:889–894. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.039180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:537–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sene Amâncio Zara A. L. dos Santos S. M. Fernandes-Oliveira E. S. Carvalho R. G. Coelho G. E. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude. 2016;25:1–2. doi: 10.5123/S1679-49742016000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana-Medeiros P. F. Bellinato D. F. Martins A. J. Valle D. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2017;31:340–350. doi: 10.1111/mve.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinato D. F. Viana-Medeiros P. F. Araújo S. C. Martins A. J. Lima J. B. P. Valle D. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2016/8603263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo A. P. Paiva M. H. S. Cabral A. M. Cavalcanti A. E. H. D. Pessoa L. F. F. Diniz D. F. A. Helvecio E. da Silva E. V. G. Silva N. M. Anastácio D. B. Pontes C. Nunes V. de Souza F. M. Magalhães F. J. R. de Melo Santos M. A. V. Ayres C. F. J. J. Insect Sci. 2019;19(3):1–15. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iez054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkya T. E. Akhouayri I. Kisinza W. David J.-P. P. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013;43:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanches S. M. Da Silva C. H. T. de P. De Campos S. X. Vieira E. M. Pesticidas: R. Ecotoxicol. e Meio Ambiente. 2003;13:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte H. A. Penilla R. P. Dzul-Manzanilla F. Che-Mendoza A. López A. D. Solis F. Manrique-Saide P. Ranson H. Lenhart A. McCall P. J. Rodríguez A. D. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013;107:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishk A. Hijaz F. Anber H. A. I. AbdEl-Raof T. K. El-Sherbeni A. E. H. D. Hamed S. Killiny N. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017;143:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H. Moreau J. A. Zina J. M. Mazgaeen L. Yoon K. S. Pittendrigh B. R. Clark J. M. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018;151:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Li G. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;27:859–867. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Beerntsen B. T. James A. A. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999;29:329–338. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Guillemin G. J. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2009;2:1–19. doi: 10.4137/ijtr.s2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz R. Stone T. W. Neuropharmacology. 2017;112:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q. Fang J. Li J. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15781–15787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q. Kim S. R. Ding H. Li J. Biochem. J. 2006;397:473–481. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q. Li J. FEBS Lett. 2002;527:199–204. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03229-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q. Beerntsen B. T. Li J. J. Insect Physiol. 2007;53:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves Filho R. A. W. da Silva C. A. da Silva C. S. B. Brustein V. P. Navarro D. M. do A. F. dos Santos F. A. B. Alves L. C. Cavalcanti M. G. dos S. Srivastava R. M. Carneiro-Da-Cunha M. das G. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009;57:819–825. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva-Alves D. C. B. dos Anjos J. V. Cavalcante N. N. M. Santos G. K. N. Navarro D. M. D. A. F. Srivastava R. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira V. S. Pimenteira C. da Silva-Alves D. C. B. Leal L. L. L. Neves-Filho R. A. W. Navarro D. M. A. F. Santos G. K. N. Dutra K. A. dos Anjos J. V. Soares T. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:6996–7003. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel L. G. Oliveira A. A. Romão T. P. Leal L. L. L. Guido R. V. C. Silva-filha M. H. N. L. Anjos J. V. Soares T. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020;28:115252. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K. E. Lundt B. F. Jorgensen A. S. Braestrup C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1996;31:417–425. doi: 10.1016/0223-5234(96)89169-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel L. G. dos Anjos J. V. Soares T. A. MethodsX. 2020;7:100982. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2020.100982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourn M. R. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1989;16:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F. Garavaglia S. Giovenzana G. B. Arca B. Li J. Rizzi M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:5711–5716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510233103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kode srl, Dragon (software for molecular descriptor calculation) version 7.0.10, 2017, 382, https://chm.kode-solutions.net/

- Todeschini R. and Consonni V., Molecular Descriptors for Chemoinformatics, Wiley, 2009, vol. 41 [Google Scholar]

- Eloy F. Lenaers R. Chem. Rev. 1962;62:155–183. doi: 10.1021/cr60216a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodford P. J. J. Med. Chem. 1985;28:849–857. doi: 10.1021/jm00145a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. M. Huey R. Lindstrom W. Sanner M. F. Belew R. K. Goodsell D. S. Olson A. J. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S. J. Kollman P. A. Nguyen D. T. Case D. A. J. Comput. Chem. 1986;7:230–252. doi: 10.1002/jcc.540070216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger J. Marsili M. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:3219–3228. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(80)80168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soares T. A. Goodsell D. S. Briggs J. M. Ferreira R. Olson A. J. Biopolymers. 1999;50:319–328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199909)50:3<319::AID-BIP7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares T. A. Goodsell D. S. Ferreira R. Olson A. J. Briggs J. M. J. Mol. Recognit. 2000;13:146–156. doi: 10.1002/1099-1352(200005/06)13:3<146::AID-JMR497>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0, Schrödinger, LL; C [Google Scholar]

- Teófilo R. F. Martins J. P. A. Ferreira M. M. C. J. Chemom. 2009;23:32–48. doi: 10.1002/cem.1192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J. P. A. Ferreira M. M. C. J. Chemom. 2013;36:554–U250. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos I. M. Agra J. P. G. de Carvalho T. G. C. de Azevedo Maia G. L. de Alencar Filho E. B. Struct. Chem. 2018;29:1287–1297. doi: 10.1007/s11224-018-1110-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alencar Filho E. B. Weber K. C. Vasconcellos M. L. A. A. Med. Chem. Res. 2014;23:5328–5335. doi: 10.1007/s00044-014-1077-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira D. B. Gaudio A. C. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 2001;19:599–601. doi: 10.1002/1521-3838(200012)19:6<599::AID-QSAR599>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiralj R. Ferreira M. M. C. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009;20:770–787. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532009000400021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.