Abstract

Background

Nausea and vomiting are distressing symptoms which are experienced commonly during caesarean section under regional anaesthesia and in the postoperative period.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions versus placebo or no intervention given prophylactically to prevent nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

Search methods

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (16 April 2020), and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of studies and conference abstracts, and excluded quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over studies.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and carried out data extraction. Our primary outcomes are intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Data entry was checked. Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Eighty‐four studies (involving 10,990 women) met our inclusion criteria. Sixty‐nine studies, involving 8928 women, contributed data. Most studies involved women undergoing elective caesarean section. Many studies were small with unclear risk of bias and sometimes few events. The overall certainty of the evidence assessed using GRADE was moderate to very low.

5‐HT3 antagonists: We found intraoperative nausea may be reduced by 5‐HT3 antagonists (average risk ratio (aRR) 0.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42 to 0.71, 12 studies, 1419 women, low‐certainty evidence). There may be a reduction in intraoperative vomiting but the evidence is very uncertain (aRR 0.46, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.73, 11 studies, 1414 women, very low‐certainty evidence). There is probably a reduction in postoperative nausea (aRR 0.40, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.54, 10 studies, 1340 women, moderate‐certainty evidence), and these drugs may show a reduction in postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.47, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.69, 10 studies, 1450 women, low‐certainty evidence).

Dopamine antagonists: We found dopamine antagonists may reduce intraoperative nausea but the evidence is very uncertain (aRR 0.38, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.52, 15 studies, 1180 women, very low‐certainty evidence). Dopamine antagonists may reduce intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.41, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.60, 12 studies, 942 women, low‐certainty evidence) and postoperative nausea (aRR 0.61, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.79, 7 studies, 601 women, low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain if dopamine antagonists reduce postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.92, 9 studies, 860 women, very low‐certainty evidence).

Corticosteroids (steroids): We are uncertain if intraoperative nausea is reduced by corticosteroids (aRR 0.56, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.83, 6 studies, 609 women, very low‐certainty evidence) similarly for intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.87, 6 studies, 609 women, very low‐certainty evidence). Corticosteroids probably reduce postoperative nausea (aRR 0.59, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.73, 6 studies, 733 women, moderate‐certainty evidence), and may reduce postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.68, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.95, 7 studies, 793 women, low‐certainty evidence).

Antihistamines: Antihistamines may have little to no effect on intraoperative nausea (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.11, 1 study, 149 women, very low‐certainty evidence) or intraoperative vomiting (no events in the one study of 149 women). Antihistamines may reduce postoperative nausea (aRR 0.44, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.64, 4 studies, 514 women, low‐certainty evidence), however, we are uncertain whether antihistamines reduce postoperative vomiting (average RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.81, 3 studies, 333 women, very low‐certainty evidence).

Anticholinergics: Anticholinergics may reduce intraoperative nausea (aRR 0.67, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.87, 4 studies, 453 women, low‐certainty evidence) but may have little to no effect on intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.79, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.54, 4 studies; 453 women, very low‐certainty evidence). No studies looked at anticholinergics in postoperative nausea, but they may reduce postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.74, 1 study, 161 women, low‐certainty evidence).

Sedatives: We found that sedatives probably reduce intraoperative nausea (aRR 0.65, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.82, 8 studies, 593 women, moderate‐certainty evidence) and intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.35, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.52, 8 studies, 593 women, moderate‐certainty evidence). However, we are uncertain whether sedatives reduce postoperative nausea (aRR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.71, 2 studies, 145 women, very low‐certainty evidence) and they may reduce postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.09, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.28, 2 studies, 145 women, low‐certainty evidence).

Opioid antagonists: There were no studies assessing intraoperative nausea or vomiting. Opioid antagonists may result in little or no difference to the number of women having postoperative nausea (aRR 0.75, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.45, 1 study, 120 women, low‐certainty evidence) or postoperative vomiting (aRR 1.25, 95% CI 0.35 to 4.43, 1 study, 120 women, low‐certainty evidence).

Acupressure: It is uncertain whether acupressure/acupuncture reduces intraoperative nausea (aRR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.74, 9 studies, 1221 women, very low‐certainty evidence). Acupressure may reduce intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.52, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.80, 9 studies, 1221 women, low‐certainty evidence) but it is uncertain whether it reduces postoperative nausea (aRR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.75, 7 studies, 1069 women, very low‐certainty evidence) or postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.79, 7 studies, 1069 women, very low‐certainty evidence).

Ginger: It is uncertain whether ginger makes any difference to the number of women having intraoperative nausea (aRR 0.66, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.21, 2 studies, 331 women, very low‐certainty evidence), intraoperative vomiting (aRR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.00, 2 studies, 331 women, very low‐certainty evidence), postoperative nausea (aRR 0.63, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.77, 1 study, 92 women, very low‐certainty evidence) and postoperative vomiting (aRR 0.20, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.65, 1 study, 92 women, very low‐certainty evidence).

Few studies assessed our secondary outcomes including adverse effects or women's views.

Authors' conclusions

This review indicates that 5‐HT3 antagonists, dopamine antagonists, corticosteroids, sedatives and acupressure probably or possibly have efficacy in reducing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section. However the certainty of evidence varied widely and was generally low. Future research is needed to assess side effects of treatment, women's views and to compare the efficacy of combinations of different medications.

Plain language summary

Reducing nausea and vomiting in women having a caesarean birth with regional anaesthesia

What is the issue?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out from randomised controlled trials how effective drugs and other treatments are for reducing nausea and vomiting during and after caesarean section with epidural or spinal anaesthesia, when compared with an inactive control. We searched for all relevant studies to answer our review question (April 2020).

Why is this important?

Women often prefer to be awake for the birth of their child, so when possible, a caesarean is performed under regional anaesthesia (spinal or epidural). Nausea and vomiting are commonly experienced during and immediately after caesarean section with regional anaesthesia. This is distressing for women. Vomiting during surgery can also challenge the operating surgeon and put the mother at risk of fluids from the stomach going into her windpipe.

Several drugs are commonly used to reduce nausea and vomiting. There are also some non‐drug approaches such as acupressure/acupuncture and ginger. Possible side effects include headaches, dizziness, low blood pressure and itching.

What evidence did we find?

We identified 69 randomised controlled studies (involving 8928 women) that provided data. Data were mostly on non‐emergency caesareans and most findings were supported only by low or very low‐certainty evidence. This was due to many of the studies being old, with small numbers of participants or unclear methodology. A few outcomes had moderate‐certainty evidence.

5‐HT3 antagonists (like ondansetron, granisetron): these probably reduce nausea after surgery, and they may also reduce nausea during surgery (low‐certainty evidence) and vomiting after surgery, but any effect on vomiting during surgery is unclear.

Dopamine antagonists (like metoclopramide, droperidol): these may reduce vomiting during surgery and nausea after surgery, but it is unclear whether they reduce nausea during surgery and vomiting after surgery.

Steroids (like dexamethasone): these probably reduce nausea after surgery and may reduce vomiting after surgery, but it is unclear whether steroids reduce nausea and vomiting during surgery.

Antihistamines (like dimenhydrinate, cyclizine): these may reduce nausea after surgery, but they make little or no difference to nausea and vomiting during surgery and vomiting after surgery.

Anticholinergics (like glycopyrrolate, scopolamine): these may reduce nausea during surgery and vomiting after surgery, but they may make little to no difference to vomiting during surgery. There were no studies on nausea after surgery,

Sedatives (like propofol, midazolam, ketamine): these probably reduce nausea and vomiting during surgery and may reduce vomiting after surgery, but it is uncertain whether they reduce nausea after surgery.

Opioid antagonists (like nalbuphine): only one small study provided data on nausea and vomiting after surgery, and found they may make little or no difference.

Acupressure/acupuncture: this may reduce vomiting during surgery but it is uncertain if it reduces nausea during surgery or nausea and vomiting after surgery.

Ginger: it is unclear if ginger reduces nausea and vomiting during surgery or nausea and vomiting after surgery.

Few studies assessed women's views. What limited data there were on side effects did not find any differences.

What does this mean?

Several classes of drugs may help to reduce the number of women who experience nausea and vomiting during and after regional anaesthesia for caesarean births, although more data are needed. Acupressure may also help but we did not find enough data on ginger. Very few studies looked at women’s views and overall, there were not enough data on possible side effects.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. 5‐HT3 antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| 5‐HT3 antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: 5‐HT3 antagonists Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with 5‐HT3 antagonists | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.42 to 0.71) | 1419 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 479 per 1000 | 263 per 1000 (201 to 340) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.46 (0.29 to 0.73) | 1414 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 5 | ||

| 241 per 1000 | 111 per 1000 (70 to 176) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.40 (0.30 to 0.54) | 1340 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 6 | ||

| 338 per 1000 | 135 per 1000 (101 to 183) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.47 (0.31 to 0.69) | 1450 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 7 | ||

| 228 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (71 to 157) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: > 90% of data comes from studies with unclear selection bias

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: there may be substantial heterogeneity I2 = 65%, Chi2 P = 0.0009.

3 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: > 80% of data comes from studies with unclear selection bias

4 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: there may be substantial heterogeneity I2 = 58%, Chi2 P = 0.008.

5 Downgrade 1 for publication bias: there is some evidence of possible publication bias in the funnel plot.

6 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: > 65% of data comes from studies with unclear selection bias

7 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: > 70% of data comes from studies with unclear selection bias

Summary of findings 2. Dopamine antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Dopamine antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: dopamine antagonists Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with dopamine antagonists (B) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.38 (0.27 to 0.52) | 1180 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 444 per 1000 | 169 per 1000 (120 to 231) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.41 (0.28 to 0.60) | 942 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 211 per 1000 | 87 per 1000 (59 to 127) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.48 to 0.79) | 601 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 393 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (189 to 311) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.63 (0.44 to 0.92) | 860 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| 264 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 (116 to 243) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: all the data come from studies with unclear risk of selection bias.

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency. Moderate to substantial heterogeneity, I2 = 54%, Chi2 P = 0.005

3 Downgrade 1 for publication bias: evidence of some publication bias in the funnel plot

Summary of findings 3. Corticosteroids compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Corticosteroids compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: corticosteroids Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with corticosteroids (C) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.56 (0.37 to 0.83) | 609 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 403 per 1000 | 226 per 1000 (149 to 334) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.31 to 0.87) | 609 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| 141 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (44 to 123) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.59 (0.49 to 0.73) | 733 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | ||

| 491 per 1000 | 290 per 1000 (240 to 358) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.68 (0.49 to 0.95) | 793 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 6 | ||

| 355 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (174 to 337) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: all the data comes from studies with unclear risk of selection bias

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: there is moderate heterogeneity I2 = 50% and Chi2 P = 0.06.

3 Downgrade 1 for imprecision: Wide CI close to line of no difference. Only 61 events out of 609 women.

4 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: 69% of data comes from studies with unclear risk of selection bias.

5 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: 83%% of data comes from studies with unclear risk of selection bias.

6 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: may show moderate heterogeneity. I2 = 52%. Chi2 P = 0.03.

Summary of findings 4. Antihistamines compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Antihistamines compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing nausea and vomiting Setting: in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Intervention: antihistamines Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Placebo | Risk with antihistamines | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.47 to 2.11) | 149 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 155 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (73 to 327) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | not estimable | 149 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 |

Only one RCT with no intraoperative vomiting events | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.44 (0.30 to 0.64) | 514 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 | ||

| 309 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (93 to 198) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.48 (0.29 to 0.81) | 333 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 4 5 | ||

| 189 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (55 to 153) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias; only one study with unclear risk of bias across 6 domains and high risk for one domain

2 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: wide CI, only 23 events out of 149 women in a single study.

3 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: there are no events.

4 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: all data from studies with unclear risk of selection bias

5 Downgrade 1 for imprecision: only 45 events out of 333 women.

Summary of findings 5. Anticholinergics compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Anticholinergics compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: anticholinergics Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with anticholinergics | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.67 (0.51 to 0.87) | 453 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 665 per 1000 | 446 per 1000 (339 to 579) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.79 (0.40 to 1.54) | 453 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 304 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (122 to 468) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | ||

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.41 to 0.74) | 161 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | ||

| 728 per 1000 | 401 per 1000 (299 to 539) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: all the data from studies with unclear selection bias.

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: there may be moderate heterogeneity I2 = 52% Chi2 P = 0.10.

3 Downgrade 1 for imprecision: wide CI, crossing the line of no difference. 120 events out of 453 women participants.

4 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: only one study with unclear allocation concealment but adequate sequence generation

5 Downgrade 1 for imprecision: a single study shows a wide confidence interval away from the line of no difference but with 91 events out of 161 women participants.

Summary of findings 6. Sedatives compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Sedatives compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: sedatives Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with sedatives (F) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.65 (0.51 to 0.82) | 593 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 375 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (191 to 308) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.35 (0.24 to 0.52) | 593 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | ||

| 294 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (71 to 153) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.25 (0.09 to 0.71) | 145 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 | ||

| 441 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (40 to 313) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.09 (0.03 to 0.28) | 145 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | ||

| 356 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (11 to 100) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: 56% of data from studies with low risk of selection bias.

2 Downgrade 1 for risk of bias: 75% of data were from studies with unclear selection bias.

3 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: moderate heterogeneity. I2 = 58%. Chi2 P = 0.09.

4 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: low number of events ‐ 37 and low number of participants 145. Wide CI though a reasonable distance from line of no difference.

5 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: low number of events ‐ 23 and low number of participants 145. Wide CI but a good distance from the line of no difference although the data of high effectiveness comes from just one study of 44 women.

Summary of findings 7. Opioid antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting.

| Opioid antagonists compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing nausea and vomiting Setting: in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Intervention: opioid antagonists Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with opioid antagonists | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | ||

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | ||

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.39 to 1.45) | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 267 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (104 to 387) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 1.25 (0.35 to 4.43) | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | ||

| 67 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (23 to 295) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for imprecision. Only 28 events out of 120 women in one study. Wide CI crossing line of no difference.

2 Downgrade 2 for imprecision. Only 9 events out of 120 women in one study. Wide CI crossing line of no difference.

Summary of findings 8. Acupressure/acupuncture compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

| Acupressure/acupuncture compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section Setting: hospitals across low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries Intervention: acupressure/acupuncture Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with acupressure/acupuncture (K) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.41 to 0.74) | 1221 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | ||

| 466 per 1000 | 256 per 1000 (191 to 345) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.33 to 0.80) | 1221 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 236 per 1000 | 123 per 1000 (78 to 189) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.46 (0.27 to 0.75) | 1069 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | ||

| 411 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (111 to 308) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.34 to 0.79) | 1069 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ||

| 302 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (103 to 239) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: all the data comes from studies which are unclear risk of selection bias.

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity I2 = 69% Chi2 P = 0.0010.

3 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity. I2 = 81% and Chi2 P = < 0.0001. Could be downgrade by 2, borderline decision

4 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency: moderate heterogeneity. I2 = 62% and Chi2 P = 0.01.

Summary of findings 9. Ginger compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting.

| Ginger compared to placebo for preventing nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing nausea and vomiting Setting: in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section? Intervention: ginger Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with ginger | |||||

| Nausea ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.36 to 1.21) | 331 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | ||

| 586 per 1000 | 387 per 1000 (211 to 709) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ intraoperative | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.38 to 1.00) | 331 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | ||

| 408 per 1000 | 253 per 1000 (155 to 408) | |||||

| Nausea ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.63 (0.22 to 1.77) | 92 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5 6 | ||

| 174 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (38 to 308) | |||||

| Vomiting ‐ postoperative | Study population | RR 0.20 (0.02 to 1.65) | 92 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 5 7 | ||

| 109 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (2 to 179) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: Only 2 studies both with unclear risk of selection bias

2 Downgrade 1 for inconsistency. Substantial heterogeneity. I2 = 74%, Chi2 P = 0.05

3 Downgrade 1 for imprecision. Very wide CI crossing the line of no difference. 170 events and 331 women participants

4 Downgrade 1 for imprecision: Wide CI. meeting the line of no difference. 112 events and 331 women participating

5 Downgrade 2 for risk of bias: Only 1 study with unclear risk of selection bias

6 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: Wide CI. Only 6 events out of 92 women

7 Downgrade 2 for imprecision: Wide CI crosses line of no difference. 5 events only and just 92 women included

Background

Nausea and vomiting are unpleasant symptoms commonly experienced by pregnant women during caesarean section under regional anaesthesia, and may also occur in the postpartum period following a caesarean under either regional or general anaesthesia. Nausea and vomiting around the time of the birth of a baby can be uncomfortable and distressing for the woman. If vomiting occurs intraoperatively during the caesarean under regional anaesthesia, it offers significant challenges to the operating surgeon, may increase the duration of surgery, the risk of bleeding, the risk of inadvertent surgical trauma and the risk of aspiration of gastric contents (Paranjothy 2014).

Caesarean section is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. World Health Organization data indicate that worldwide around 140 million babies are born each year. Globally caesarean rates vary widely; from less than 5% of births in low‐income countries (e.g. Zimbabwe) to above 30% in high‐income countries (e.g. Germany) (Boerma 2018) and in one study of NHS trusts the caesarean section rate ranged from 14.9% to 32.1% (Bragg 2010). These figures suggest the number of caesareans worldwide is at least 10 to 20 million per year. Caesarean section rates have also risen considerably in many countries in recent years and this trend is continuing (Chen 2018). There are several reasons why general anaesthesia should be avoided if possible in the later stages of pregnancy, and most women want to be awake for the birth of their child, so except where there is a contraindication or in some emergency situations, most caesareans are carried out under regional anaesthesia using spinal or epidural techniques.

Many factors can contribute to the development of nausea and vomiting at caesarean section. While some causes of nausea and vomiting are common to other non‐obstetric surgical procedures, many are unique to caesarean sections. There is a body of published literature, including consensus guidelines (Gan 2019), to help anaesthetists reduce the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting. However, because some of the underlying causes of nausea and vomiting during caesarean section may be specific to the procedure, it is reasonable to assume that the choice of effective treatments may also differ from other types of surgery. Anaesthetists need to consider specific evidence in this setting. Since all interventions are associated with increased healthcare costs and potential risks to the woman (and potentially to the neonate, via either placental transfer or breastfeeding) it is clear that antiemetic use should be evidence‐based.

In some countries, for example in the United Kingdom, there is a recommendation that to reduce nausea and vomiting at caesarean delivery the routine administration of drugs (antiemetics ‐ drugs to reduce nausea and vomiting) or acupressure should be considered (NICE 2011). However, many anaesthetists may choose to give antiemetic medication only when nausea and vomiting occur (treatment) rather than as prophylaxis (prevention). It is not known to what extent medications which have been shown to be efficacious as treatment are also efficacious as prophylaxis (and vice versa).

The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of interventions to prevent nausea and vomiting given as prophylaxis during caesarean section under regional anaesthesia. Future reviews will be required to assess studies on interventions for treatment (rather than prevention) of nausea and vomiting, procedures performed as emergencies and caesarean deliveries performed under general anaesthesia.

Description of the condition

Nausea is the unpleasant subjective urge to vomit, while vomiting is the physiological process associated with propulsive abdominal muscular spasms leading to the expulsion of gastric contents. Retching involves the same propulsive muscular spasms as vomiting but without the expulsion of any gastric contents.

There are several aetiological factors (factors causing or contributing to the development of a condition or disease) which may contribute to the development of nausea and vomiting during caesarean section. These may include the following.

Haemodynamic changes (i.e. changes in blood flow) such as hypotension (low blood pressure ‐ a frequent side effect of regional anaesthesia, Chooi 2017) and reduced cardiac output from aorto‐caval compression resulting from placing the woman on her back (supine position) (Cooke 1979).

Surgical stimulation from visceral traction such as manual delivery of the baby and in particular, exteriorisation of the uterus(temporary removal of the uterus from the abdominal cavity to facilitate repairing the incision), Wahab 1999).

Intraoperative medications may contribute to nausea and include opiates, antibiotics and administered uterotonics such as oxytocin and particularly ergometrine (De Groot 1998).

Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, fatigue and prolonged starvation should not be underestimated as contributors to nausea and vomiting. This may particularly be the case with emergency caesarean delivery.

Medications given prior to the caesarean, such as medications to reduce the risk of aspiration (Paranjothy 2014). If the woman has been in labour prior to surgery then pain relief already provided such as opioids and nitrous oxide may also have residual emetogenic effects.

Few prospective observational studies or audit data have been published and so the underlying incidence of nausea and vomiting during caesarean section is uncertain. It is also likely that the baseline rate will vary considerably depending on the anaesthetic, analgesic and vasopressor regimen that is being used. However, it would seem reasonable to use the rates in the placebo arms of well‐designed randomised trials as an indication of the baseline rate of nausea and vomiting. Published placebo data show rates of intraoperative nausea in the order of 48% (Habib 2013) to 79% (Abouleish 1999). Vomiting rates are typically lower than the rates of nausea, in the order of 15% (Voigt 2013) to 38% (El‐Deeb 2011a). Most studies recruit women in the setting of elective caesarean section, and it is likely that rates are higher in the setting of emergency caesarean section.

Nausea and vomiting in the postpartum period are also common, and can affect women who received either regional or general anaesthesia. In most types of surgery, the use of regional anaesthesia is thought to be associated with lower rates of postoperative nausea and vomiting than general anaesthesia (Gan 2019); however, this difference may not be apparent following caesarean delivery. Almost all postoperative analgesia regimens involve the use of opioid type medications, either by oral, intravenous or neuraxial (spinal or epidural) routes, all of which can contribute to nausea and vomiting.

Description of the intervention

In this review, we have included pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions given specifically for the purpose of preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing caesarean under regional anaesthesia. Whilst hypotension is an important cause of these symptoms during a caesarean, treatment for hypotension during regional anaesthesia has already been specifically addressed in another Cochrane Review (Chooi 2017). Similarly, interventions to reduce the risk of acid aspiration may well affect nausea and vomiting and these interventions have also been addressed in another Cochrane Review (Paranjothy 2014).

The pharmacological interventions available include medications from a wide range of drug classes including serotonin and dopamine receptor antagonists, corticosteroids, antihistamines, sedatives and anticholinergics (Flake 2004). A number of non‐pharmacological approaches have also been used traditionally to treat nausea in pregnancy, and some of these have been studied in this setting. These include acupuncture or acupressure (Ho 2006) and oral ginger (Kalava 2013).

How the intervention might work

Pharmacological interventions

For many of the recognised interventions used for the prevention of nausea and vomiting, the mechanism of action is not well understood. However, most treatments can be classed pharmacologically based on their biochemical receptor target. Nausea and vomiting caused by visceral stimulation is thought to be mediated predominantly via serotonin (5‐HT) and dopamine receptors. The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) is a small region within the brainstem responsible for the symptoms of medication and toxin related emesis, including post anaesthetic nausea and vomiting, and is also mediated by serotonin and dopamine. In contrast, nausea and vomiting caused by central nervous system and vestibular mechanisms, such as motion sickness, are thought to be mediated mainly via histamine and acetylcholine.

The main classes of medications in use include the following (Flake 2004; Gan 2003).

Serotonin (5‐HT3) receptor subtype‐3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron, granisetron) antagonise the emetic effects of serotonin in the small bowel, vagus nerve and CTZ (Peixoto 2006). They are effective (George 2009) and have few side effects.

Dopamine receptor antagonists (e.g. metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, droperidol, domperidone) antagonise the effects of dopamine at the D2 receptors in the CTZ. They have a wide variety of associated side effects including sedation, agitation, and extra‐pyramidal effects (Chestnut 1987). Droperidol has been associated with very rare, but potentially life‐threatening, cardiac arrhythmias.

Corticosteroids also known as steroids (most commonly dexamethasone) are regarded as being highly effective, but their mechanism of action is unclear (Tzeng 2000). Whilst long‐term steroid use can lead to a wide variety of side effects such as fluid and electrolyte changes, obesity, and diabetes, single antiemetic doses are well tolerated, even in diabetics.

Antihistamines (e.g. promethazine and cyclizine (Nortcliffe 2003) can cause a variety of adverse effects including sedation and dry mouth.

Anticholinergic agents (e.g. glycopyrrolate (Ure 1999) and scopolamine (Kotelko 1989) are mainly useful for nausea and vomiting caused via the vestibular system, i.e. motion sickness. They can also cause a dry mouth and potentially urinary retention.

Sedatives. Very low doses of sedatives such as midazolam or propofol (Mukherjee 2006; Tarhan 2007) seem to have antiemetic efficacy. The mechanism of action is unclear, but may relate to the contribution of psychological factors such as stress and anxiety to the incidence of emetic symptoms.

Opioids antagonists or partial agonists. A number of studies have attempted to demonstrate the beneficial effects of opioids. Whilst opioids would generally be considered a cause, rather than a treatment, of nausea and vomiting, it is possible that when two opioids are administered together, one of them may reduce the opioid‐induced emetic symptoms caused by the other. If one drug is an opioid antagonist or partial agonist (such as naloxone or nalbuphine) (Charuluxananan 2003), then it may reduce the opioid‐related side effects (such as nausea, itch and constipation) without unduly reducing the analgesic benefits.

Non‐pharmacological interventions

Acupuncture or acupressure: acupressure or acupuncture at the P6 point at the wrist has long been a traditional treatment for nausea, particularly sea sickness. The mechanism of action of acupuncture and acupressure is not well understood (Duggal 1998; Harmon 2000). Potential adverse effects of acupuncture include infection or trauma from acupuncture needles.

Alternative natural therapies such as ginger (Kalava 2013; Zeraati 2016) and peppermint (Lane 2012; Niaki 2016) also have long histories of use as traditional treatments for reducing nausea in pregnancy. Although associated with minimal side effects, their efficacy is uncertain (Matthews 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Nausea and vomiting are very common symptoms experienced both during and following caesarean section, may increase morbidity, and can be very distressing for women and their families. Many interventions are available and routine prophylactic treatment has been proposed (NICE 2011). The available interventions have widely varying cost and significant side‐effect profiles. Whilst guidelines exist for the prevention of nausea and vomiting after general anaesthesia in non‐pregnant patients (Gan 2019), the aetiology of emetic symptoms at caesarean section are clearly multifactorial and the current literature may not be directly applicable. This review is important to ensure that women undergoing caesarean section are offered interventions to prevent nausea and vomiting which are safe, efficacious and cost‐effective.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions versus placebo or no intervention given prophylactically to prevent nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including conference abstracts. We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials, but none were identified. Quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Pregnant women undergoing elective or emergency caesarean section under regional anaesthesia.

Types of interventions

In this updated review, we have included studies where the participants were women undergoing caesarean section under regional anaesthesia (either spinal, epidural or both) comparing interventions for nausea and vomiting against placebo or no intervention. Intervention versus intervention comparisons were excluded. We included studies where the intervention was given with the express purpose of preventing nausea and vomiting, either intraoperative, postoperative, or both.

Interventions included the following categories.

Serotonin (5‐HT3) receptor antagonists (e.g. ondansetron, granisetron).

Dopamine receptor antagonists (e.g. metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, droperidol, domperidone).

Corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone).

Antihistamines (e.g. promethazine, cyclizine).

Anticholinergic agents (e.g. glycopyrrolate, scopolamine).

Sedatives (e.g. midazolam, propofol).

Opioids antagonists or partial agonists (e.g. nalbuphine).

Acupressure/acupuncture.

Alternative therapies such as ginger or peppermint.

We compared the different drug classes against placebo, setting out individual drugs and doses as subgroups.

We excluded:

studies where the authors were comparing two different treatments (unless there was also a control/placebo arm) and studies investigating combinations of treatments;

studies where the intervention was for reducing aspiration pneumonitis, as this is the subject of another review (Paranjothy 2014);

studies where the express purpose was to treat another problem which may impact upon the development of nausea or vomiting, such as studies assessing agents for treating hypotension. This has also been studied in another review (Chooi 2017);

studies where a recognised antiemetic was given, but the focus of the study was on another effect of that medication (for example, studies on the haemodynamic effects of ondansetron);

studies which assessed the efficacy of interventions for treatment, rather than prevention, of nausea and vomiting. This may be the subject of a separate future review;

studies where the intervention was not recognised as an antiemetic and did not have a reasonable theoretical justification for affecting nausea and vomiting, e.g. supplemental oxygen; intravenous fluids; anticonvulsants; antidepressants, opioid agonists.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Nausea intraoperatively.

Vomiting (and/or retching) intraoperatively.

Nausea postoperatively.

Vomiting (and/or retching) postoperatively.

Secondary outcomes

Nausea plus vomiting/retching.

Maternal adverse effects: e.g. sedation, restlessness, extra‐pyramidal effects, surgical bleeding, hypotension, atonic uterus.

Neonatal morbidity: e.g. Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes.

Initiation of breastfeeding.

Duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Maternal satisfaction (using a validated questionnaire).

In this review, when authors reported retching and vomiting separately, we combined these data, as we believe retching is more pathophysiologically analogous to vomiting than nausea. In this update, we clarified our approach to the postoperative data. Where a paper reports a number of time epochs (for example, zero to four hours, four to eight hours, etc), we have included data from the earliest reported time period because we believe these data were most likely to reflect the efficacy of the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (16 April 2020).

The Register is a database containing over 25,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies, Excluded studies, Studies awaiting classification or Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (1 April 2020) using the search methods described in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched for further studies in the reference list of the studies identified.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeGriffiths 2012.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 174 new studies that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2020) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2019). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals. Where a random‐effects model has been used, we report this as an average risk ratio (aRR).

Continuous data

We planned to use mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials and standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials, but did not identify any. Had we identified any, we would have adjusted their standard error using the methods described in the Handbook[Section16.3.4 and 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we had used ICCs from other sources, we would have reported this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would have considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

We excluded cross‐over trials.

Other unit of analysis issues

Where we found multi‐arm studies, we assessed which arms were relevant to our question and included data taking care not to double count the data in the placebo group by dividing the placebo data equally amongst the relevant comparisons such that when the data were pooled, the correct number of events and participants were included.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as reported in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity*;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity*;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity*.

and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2020).

We used random‐effects meta‐analyses for combining data because we considered that there would be heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects would differ between trials because our question is around groups of drugs and so we are combining data from different drugs and different doses within the meta‐analyses.

The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. The results are presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Different drugs with the same group of drugs

Difference doses of the drugs within the group of drugs

The following four primary outcomes were used in subgroup analyses.

intraoperative nausea

intraoperative vomiting

postoperative nausea

postoperative vomiting

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2020). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by selection bias (sequence generation and allocation concealment) and attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), with poor‐quality studies (either high risk or unclear risk) being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

For this update, the certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook to assess the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons. All nine comparisons were chosen as a specific focus as they represent the most clinically‐relevant comparisons in this updated review.

Comparisons for GRADE and Summary of findings

5‐HT3 antagonists versus placebo

Dopamine antagonists versus placebo

Corticosteroids versus placebo

Antihistamines versus placebo

Anticholinergics versus placebo

Sedatives versus placebo

Opioid antagonists/partial agonists versus placebo

Acupressure/acupuncture versus placebo

Ginger versus placebo

Outcomes for GRADE and Summary of findings

Incidence of intraoperative nausea

Incidence of intraoperative vomiting/retching

Incidence of postoperative nausea

Incidence of postoperative vomiting/retching

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2020) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high certainty' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, serious inconsistency, indirectness of evidence, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

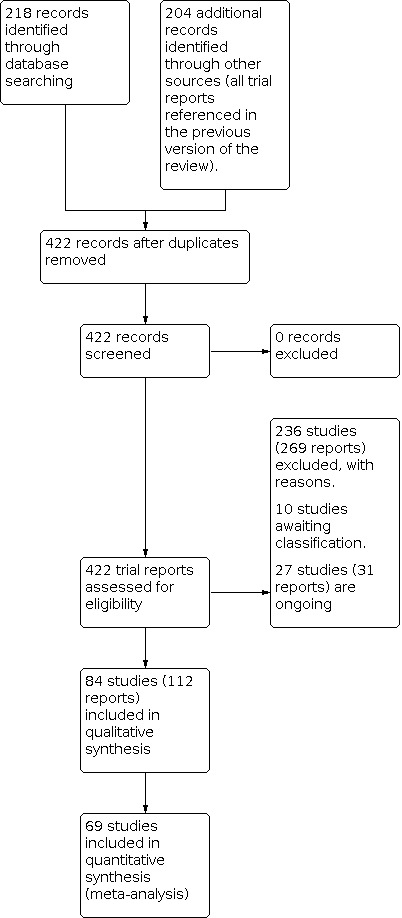

We assessed 218 new trial reports, plus the change in scope meant we also reassessed the 204 trial reports referenced in the previous version of the review.

All in all in this 2021 update, there are 84 included studies (112 reports) (Characteristics of included studies) and 236 excluded studies (269 reports) (Characteristics of excluded studies). Ten studies are awaiting classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). These are predominantly conference abstracts where we have been unable to contact the authors or studies in a non‐English language where we have been unable to obtain a translation as yet. There are 27 studies identified as ongoing (31 reports) (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

The change in scope meant we excluded nine studies from the 2012 publication, six of these studies had provided data (Chestnut 1989; Gaiser 2002; Owczarzak 1997; Pecora 2009; Phillips 2007; Shahriari 2009), and three had provided no data (Biwas 2002; Chaudhuri 2004; Manullang 2000).

In addition, there were eight comparisons in multi‐arm studies where, due to our change in scope, some arms were now excluded and the data from these women were not included in our review (Abdollahpour 2015; Habib 2013; Khalayleh 2005; Levin 2019; Mokini 2014; Shen 2012; Voigt 2013; Wu 2007).

(See: Figure 1)

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the 84 included studies (involving 10,990 women), 69 studies involving 8928 women provided usable data for this review, taking into account the arms of the multi‐arm studies which are not included in our inclusion criteria (Abdel‐Aleem 2012; Abdollahpour 2015; Abouleish 1999; Ahn 2002; Apiliogullari 2007; Baciarello 2011; Biswas 2003; Caba 1997; Cardoso 2013; Carvalho 2010; Charuluxananan 2003; Cherian 2001; Chestnut 1987; Choi 1999; Dasgupta 2012; Direkvand‐Moghadam 2013; Duggal 1998; Duman 2010; El‐Deeb 2011a; Garcia‐Miguel 2000; Habib 2006; Habib 2013; Harmon 2000; Harnett 2007; Hassanein 2015; Ho 1996; Ho 2006; Huang 1992; Ibrahim 2019; Jaafarpour 2008; Kalava 2013; Kampo 2019; Kasodekar 2006; Khalayleh 2005; Koju 2015; Kotelko 1989; Levin 2019; Li 2012; Lussos 1992; Mandell 1992; Maranhao 1988; Mohammadi 2015; Mokini 2014; Mukherjee 2006; Munnur 2008; Niu 2018; Noroozinia 2013; Nortcliffe 2003; Pan 1996; Pan 2001; Pan 2003; Parra‐Guiza 2018; Peixoto 2006; Rasooli 2014; Rudra 2004a; Sahoo 2012; Selzer 2020; Shabana 2012; Shen 2012; Stein 1997; Tarhan 2007; Tkachenko 2019; Tzeng 2000; Uerpairojkit 2017; Ure 1999; Voigt 2013; Wang 2001; Wu 2007; Zeraati 2016).

Fifteen studies are included but do not contribute data to the meta‐analysis because the data were either presented in a graphical format only, or there was no information on the number of women in each outcome group (Birnbach 1993; Boone 2002; ; Imbeloni 1986; Jang 1997; Kim 1999; Lee 2002; Lim 2001a; Lim 2001b; Liu 2015a; Modir 2019; Pazoki 2018; Quiney 1995; Sanansilp 1998; Weiss 1995; Yazigi 2002). We have written to these authors requesting further information.

Multi‐arm studies

There are 41 multi‐arm studies, 31 are three‐arm studies (Abdollahpour 2015; Apiliogullari 2007; Baciarello 2011; Birnbach 1993; Choi 1999; Direkvand‐Moghadam 2013; Duman 2010; El‐Deeb 2011a; Garcia‐Miguel 2000; Habib 2013; Harnett 2007; Hassanein 2015; Kampo 2019; Khalayleh 2005; Levin 2019; Li 2012; Maranhao 1988; Modir 2019; Munnur 2008; Nortcliffe 2003; Pan 1996; Pan 2001; Parra‐Guiza 2018; Pazoki 2018; Peixoto 2006; Rasooli 2014; Sanansilp 1998; Stein 1997; Tarhan 2007; Tkachenko 2019; Tzeng 2000; Voigt 2013) and 10 studies are four‐arm studies (Ahn 2002; Biswas 2003; Charuluxananan 2003; Lee 2002; Mokini 2014; Mukherjee 2006; Shen 2012; Voigt 2013; Wang 2001; Wu 2007). Where two or more arms of a study fell within the same comparison, we treated the data as described in the Unit of analysis issues.

Of the multi‐arm studies which provided data, 18 compared more than one drug against placebo but the drugs were in different categories and so in different comparisons (Biswas 2003; Choi 1999; Direkvand‐Moghadam 2013; Duman 2010; El‐Deeb 2011a; Garcia‐Miguel 2000; Harnett 2007; Hassanein 2015; Kampo 2019; Nortcliffe 2003; Pan 1996; Pan 2001; Parra‐Guiza 2018; Peixoto 2006; Shen 2012; Stein 1997; Tzeng 2000; Wu 2007). Six multi‐arm studies providing data included arms with one of our excluded drugs or a combination of drugs, so data from these arms were excluded (Abdollahpour 2015; Habib 2013; Khalayleh 2005; Levin 2019; Li 2012; Voigt 2013). Seven multi‐arm studies providing data looked at different concentrations of the same drug or different routes of administration and we adjusted the placebo data accordingly (Ahn 2002; Apiliogullari 2007; Baciarello 2011; Lee 2002; Mukherjee 2006; Tkachenko 2019; Wang 2001). Four multi‐arm studies looked at different drugs from the same category and so were in the same comparison and here we adjusted the placebo data accordingly (Maranhao 1988; Munnur 2008; Rasooli 2014; Tarhan 2007). One four‐arm study looked at two drugs from different categories and for one of these drugs looked at two doses, the placebo data was dealt with accordingly (Charuluxananan 2003) and another four‐arm study one arm was excluded as it was a combination of drugs and the other two arms were drugs in different categories (Mokini 2014). Four of the multi‐arm studies provided no data that we could use in this review (Birnbach 1993; Pazoki 2018; Sanansilp 1998; Modir 2019).

Populations

The included studies covered women undergoing elective and emergency caesarean sections under regional anaesthesia, with either spinal or epidural anaesthesia. Most studies reported women in American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification (ASA) Grade 1 to 2, and so generally with no medical problems (Characteristics of included studies)

Interventions

The studies covered drugs in seven different classes of drugs. For 5‐HT3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron, granisetron) there were 21 studies involving providing data on 2686 women; for dopamine antagonists (e.g. metoclopramide, droperidol) there were 20 studies providing data on 1880 women; for corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone) there were 12 studies providing data on 1182 women; for antihistamines (e.g. dimenhydrinate, cyclizine) there were four studies providing data on 514 women; for anticholinergics (e.g. glycopyrrolate, scopolamine) there were six studies providing data on 787 women; for sedatives (e.g. propofol, midazolam) there were 13 studies providing data on 1265 women; and for opioid antagonists/partial agonists (nalbuphine) there were two studies providing data on 197 women. Ten studies on acupressure/acupuncture provided data on 1401 women and two studies on ginger which provided data on 365 women (Characteristics of included studies).

Outcomes

Most studies reported intraoperative nausea, intraoperative vomiting, postoperative nausea and postoperative vomiting separately, but a few reported combines nausea and vomiting both intraoperative and postoperative. Some studies reported looking for side effects/adverse effects such as hypotension, itching, dizziness. Few studies looked at women's satisfaction (Characteristics of included studies).

Settings

The 84 studies were undertaken in a wide range of countries across the world (see Characteristics of included studies):

Americas (24 studies) ‐ USA 18 studies, South America four studies (including one from Columbia and two from Brazil), Canada two studies;

Asia (24 studies) ‐ India five studies, China five studies, Nepal one study, Thailand three studies, Taiwan three studies; South Korea five studies, Singapore two studies;

Middle East (14 studies) ‐ Iran 10 studies, Lebanon one study, Turkey three studies;

UK/Europe (10 studies) ‐ UK four studies, Germany one study, Ireland one study, Italy one study, Spain two studies; Ukraine one study;

Africa (seven studies) ‐ Egypt six studies, Ghana one study.

For two studies, there was no information provided on the setting, and three studies were conducted across multiple countries (e.g. USA and UK).

Dates of included studies

Fifty‐nine studies did not report the dates over which their studies were undertaken. The studies which reported dates covered 2001 to 2017 and publication dates range from 1987 to 2020 (Characteristics of included studies).

Funding sources of included studies

Seventy‐one studies did not report funding sources. Of the studies reporting this information, two studies reported commercial company funding (Abouleish 1999; Duggal 1998), one study specifically reported no commercial funding (Cherian 2001), nine studies reported finding from universities, hospitals and public funding bodies (Abdollahpour 2015; Cardoso 2013; Direkvand‐Moghadam 2013;Duggal 1998; Modir 2019; Parra‐Guiza 2018; Pazoki 2018; Selzer 2020; Zeraati 2016), and two studies reported specifically that they had no funding (Kampo 2019; Levin 2019).

Declarations of interest of authors of included studies

Seventy‐three studies did not report on declarations of interest of the authors. Eleven studies reported no conflict of interest for their authors (Abdel‐Aleem 2012; Abouleish 1999; Cardoso 2013;Kampo 2019; Koju 2015; Levin 2019; Niu 2018; Parra‐Guiza 2018; Selzer 2020; Uerpairojkit 2017; Voigt 2013).

Elective versus emergency caesarean sections