Abstract

Background

In this study, to clarify the evolving background of people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), we compared the current prevalence of NAFLD with that of 2 decades ago.

Methods

We included two cohorts. The past cohort was from 1994 to 1997 and included 4279 men and 2502 women. The current cohort was from 2014 to 2017 and included 8918 men and 7361 women. NAFLD was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography.

Results

The prevalence of NAFLD increased in both genders throughout these 2 decades (18.5% in the past cohort and 27.1% in the current cohort for men; and 8.0% in the past cohort and 9.4% in the current cohort for women). The prevalence of hyperglycemia increased, whereas the prevalence of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and hypertriglyceridemia significantly decreased. There was no significant difference in the mean body mass index. Multivariate analysis revealed that the prevalence of obesity and body mass index were significantly associated with the prevalence of NAFLD in both the past and current cohorts.

Conclusions

The incidence of NAFLD significantly increased throughout these 2 decades, and obesity is the most prevalent factor. Thus, body weight management is an essential treatment option for NAFLD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-021-01809-2.

Keywords: Cohort, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD, Epidemiology, Trend

Introduction

It is well known that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one common cause of chronic liver disease [1], as is the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease concurrently [2, 3]. The prevalence of NAFLD shows a significant variation between countries and regions. Generally, the prevalence in the western countries is 20–40%, whereas in Asian countries 12–30% [4–8], and between 1980 and 2010, mortality associated with chronic liver disease, including NAFLD, increased by 46% worldwide [9].

The environment surrounding NAFLD has continuously been evolving [10, 11]. In Japan, the number of patients with NAFLD has increased to 20–30% because of the shift to a high-fat diet and sedentary lifestyle [12, 13]. Additionally, the age distribution of NAFLD patients indicates that it is more frequent among middle-aged men and older women [14, 15]. It has been reported that the prevalence of NAFLD increased from 12.9% in 1994 to 23.9% in 2004 in Japan [16]. The prevalence of NAFLD is on the rise, with an increasing number of people with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Therefore, to clarify the evolving background of people with NAFLD, we compared current cohort of patients with cohorts from 2 decades ago. Furthermore, we focused on the metabolic abnormalities of patients with NAFLD.

Methods

Study population and design

In Japan, citizens receive a nationwide health checkup program known as Ningen Dokku, which roughly translates to “human dock” (resembling patient checkups to ships being repaired at docks). This nationwide program promotes public health through the detection of chronic diseases, including gastrointestinal illnesses and other types of cancer, and their corresponding risk factors mainly for a primary care population. Most of them are annual medical examinations as instructed by their workplaces, or they receive medical examinations individually. At the time of the examination, the person in charge asked whether or not they agreed to participate in the study, and the study was conducted on subjects who agreed to participate. This routine checkup includes blood and urine examinations, upper gastrointestinal series or gastroesophageal endoscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, and fecal occult blood tests.

We performed a longitudinal cohort study named the NAGALA (NAfld in the Gifu Area, Longitudinal Analysis) to investigate the impact of fatty liver on several aspects of the metabolic syndrome from 1994 onwards [12]. The ethics committee approved the current version of the NAGALA study (IRB number: 2018-09-01). The study design was opt-out sampling. Participants who underwent health checkups at the Asahi University Hospital were contacted to volunteer to take part in this research. Subjects were excluded only if unwilling to participate.

We included two cohorts that were 20 years apart in our study. The past cohort was composed of participants who participated in the health checkup programs from June 1994 to December 1997. The current cohort, which was 2 decades ahead of the past cohort, consisted of participants who participated in the health checkup programs from January 2014 to December 2017.

We excluded patients having liver disease or history of any medication use [12, 17]. Liver disease was indicated if positive for hepatitis B antigen or hepatitis C antibody, or history of known liver disease, including genetic, viral, drug-induced, or autoimmune liver disease [18].

Data collection and measurements

The methods for data collection and measurements were described in our previous study [17]. Briefly, we used a standardized self-administered questionnaire to collect information not only about the medical history, but also about lifestyle factors, such as alcohol intake, smoking habits, and physical activity [12, 17]. The mean ethanol intake per week was estimated by the amounts and types of alcoholic beverages consumed per week. We divided the patients into three groups: the non-alcoholic group with < 210 g/week for men and < 140 g/week for women (none or minimal alcohol consumption: < 40 g/week, light alcohol consumption: 40–210 g/week for men and 40–140 g/week for women); the intermediate group with 210–420 g/weeek for men and 140–280 g/week for women; and the alcoholic group with ≥ 420 g/week for men and ≥ 280 g/week for women [19].

Regarding the smoking status, we classified the patients into three groups: non-smokers, ex-smokers, and current smokers. The patients were defined as regular exercisers if they participated in any sports activity at least once a week regularly [20]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m) squared. The conventional criteria for Asian obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) were used [21, 22]. In addition, we defined metabolic abnormality as hypertension (blood pressure > 130/85 mmHg), hyperglycemia (fasting plasma glucose > 5.6 mmol/L), hypertriglyceridemia (serum triglycerides > 1.70 mmol/L), and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels (serum HDL cholesterol < 1.03 mmol/L in men and < 1.29 mmol/L in women) [22]. Moreover, NAFLD fibrosis score was calculated with the following formula: − 1.675 + 0.037 × age (years) + 0.094 × BMI (kg/m2) + 1.13 × IFG/diabetes (yes = 1, no = 0) + 0.99 × aspartate transaminase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) − 0.013 × platelet count (× 109/L) − 0.66 × albumin (g/dL) [23]. FIB4 index was calculated with the following formula: age × AST (IU/L)/platelet count (× 109/L)/√ALT(IU/L) [24].

Definition of fatty liver and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Fatty liver was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography performed by a trained technician [25]. Gastroenterologists reviewed the images alone to diagnose fatty liver without referring to other personal data of the patients. In this study, of four known criteria (hepatorenal echo contrast, liver brightness, deep attenuation and vascular blurring), the participants with hepatorenal contrast and liver brightness were diagnosed as having fatty liver. In addition, we defined patients with fatty liver as having NAFLD on the basis of volume of their alcohol intake as < 210 g/week for men and < 140 g/week for women [26].

Statistical analysis

P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We analyzed all data using the JMP software (ver. 13). We divided the participants into men and women. Medians or frequencies of variables were calculated, and continuous variables were presented as the median ± interquartile range (IQR), and categorized variables were presented as a percentage. A chi-square test was performed to assess the statistical significance of differences between the groups for categorical variables. The continuous variables did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. We performed logistic regression analyses to calculate the unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of several factors that influence the presence of NAFLD. To examine the effects of several factors on NAFLD, we considered the following factors as independent variables in multivariate logistic regression analyses. Model 1 was adjusted for age, alcohol intake, exercise habits, ALT levels, smoking status, exercise, BMI, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol levels. Model 2 was adjusted for age, alcohol intake, exercise habits, ALT levels, smoking status, obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL cholesterol levels.

In addition, the area under the curve (AUC) of several factors, including BMI, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels, for the prevalence of NAFLD was calculated by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Moreover, we sought optimum cut-off value for the prevalence of NAFLD.

Results

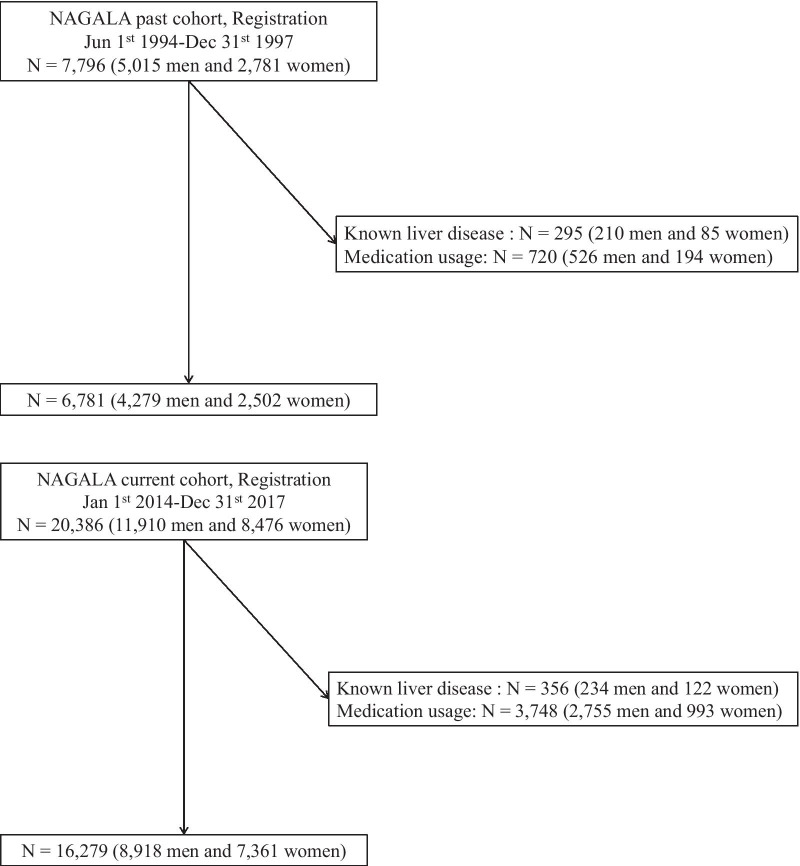

The past cohort consisted of 7796 participants (5015 men and 2781 women), whereas the current cohort consisted of 20,386 participants (11,910 men and 8476 women). After excluding patients with known liver disease and history of any medication use, 6781 patients (4279 men and 2502 women) in the past cohort and 16,279 (8918 men and 7361 women) in the current cohort were finally included in our study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant registration. NAGALA NAfld in Gifu Area, Longitudinal Analysis, CKD chronic kidney disease

Table 1 represents the clinical characteristics of our study. The prevalence of NAFLD increased in both men and women throughout these 2 decades (men, 18.5% in the past and 27.1% in the current cohort, p < 0.001; and women, 8.0% in the past and 9.4% in the current cohort, p = 0.024). Regarding smoking status, the number of current smokers decreased in the 2 decades for both genders. In terms of exercise habits, the number of regular exercisers increased in men, whereas it decreased in women. Regarding alcohol intake, average alcohol intake and number of alcohol drinkers decreased for men. In contrast, the prevalence of alcohol drinkers increased in women, although the average alcohol intake decreased. Regarding metabolic abnormalities, components of obesity and hyperglycemia worsened in men. In contrast, hyperglycemia was the only component found to have increased in women, whereas hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL cholesterol levels improved. Additionally, we investigated the characteristics of non-alcoholic participants (Additional file 1: Table S1). In non-alcoholic participants, both men and women showed the same trend of metabolic abnormalities as in the all participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants at baseline examination

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past (n = 4279) | Current (n = 8918) | p value | Past (n = 2502) | Current (n = 7361) | p value | |

| Age (years old) | 47.0 (16.0) | 48.0 (16.0) | 0.563 | 45.7 (10.1) | 47.3 (14.0) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.0 (3.5) | 23.5 (4.0) | < 0.001 | 21.7 (3.0) | 21.4 (3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 20.4 (870) | 23.4 (2087) | < 0.001 | 11.7 (292) | 10.5 (771) | 0.096 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122.8 (22.5) | 121.3 (19.5) | < 0.001 | 115.6 (18.5) | 112.3 (21.0) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77.3 (14.5) | 75.4 (15.5) | < 0.001 | 71.5 (11.2) | 67.3 (15.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.1 (48) | 0.9 (82) | 0.275 | 0.9 (23) | 0.5 (34) | 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.4 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.3 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 21.6 (919) | 42.2 (3759) | < 0.001 | 9.5 (237) | 16.3 (1195) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 1.0 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 33.5 (1432) | 12.2 (1091) | < 0.001 | 9.4 (234) | 2.3 (170) | < 0.001 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | 35.5 (1505) | 7.2 (638) | < 0.001 | 37.4 (926) | 6.0 (439) | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 21.8 (6.0) | 19.1 (9.0) | < 0.001 | 18.6 (4.0) | 15.5 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 21.7 (12.0) | 23.5 (13.0) | < 0.001 | 13.3 (6.0) | 13.9 (14.8) | 0.003 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (IU/L) | 45.7 (34.0) | 31.3 (33.4) | < 0.001 | 17.2 (10.0) | 14.5 (6.5) | 0.036 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | 21.6 (905) | 37.2 (3269) | < 0.001 | 85.0 (2079) | 85.9 (6285) | 0.293 |

| Ex-smoker | 25.5 (1068) | 33.4 (2941) | < 0.001 | 4.7 (116) | 8.8 (646) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 52.9 (2217) | 29.4 (2585) | < 0.001 | 10.3 (251) | 5.3 (389) | < 0.001 |

| Habit of exercise | 18.0 (771) | 20.3 (1792) | 0.002 | 18.4 (459) | 16.2 (1176) | 0.013 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/week | 131.4 (154.0) | 95.4 (125.0) | < 0.001 | 27.3 (36.0) | 24.9 (12.0) | 0.172 |

| Nonalcoholic | 78.9 (3374) | 85.2 (7602) | < 0.001 | 96.0 (2403) | 95.2 (7009) | 0.083 |

| (None or minimal) | 51.2 (2189) | 63.4 (5656) | < 0.001 | 81.5 (2039) | 84.7 (6234) | < 0.001 |

| (Light) | 27.7 (1185) | 21.8 (1946) | < 0.001 | 14.5 (364) | 10.5 (775) | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 15.3 (653) | 10.8 (967) | < 0.001 | 2.8 (71) | 2.9 (214) | 0.858 |

| Alcoholic | 5.9 (252) | 3.9 (349) | 0.002 | 1.1 (28) | 1.9 (138) | 0.008 |

| Fatty liver | 22.5 (963) | 31.2 (2785) | < 0.001 | 8.4 (211) | 9.9 (721) | 0.035 |

| NAFLD | 18.5 (792) | 27.1 (2412) | < 0.001 | 8.0 (199) | 9.4 (691) | 0.024 |

| NAFLD fibrosis score | − 2.27 (1.13) | − 2.38 (1.19) | < 0.001 | − 2.22 (1.05) | − 2.60 (1.08) | < 0.001 |

| Fib4 index | 1.08 (0.51) | 0.93 (0.53) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (0.45) | 0.88 (0.47) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as median (IQR) or % (number) of subjects

p values by one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables

BMI, body mass index; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Next, we compared the differences between patients with and without NAFLD in the past and current cohorts (Table 2). The prevalence of metabolic abnormalities and metabolic syndrome score was significantly higher in patients with NAFLD than in those without, for both genders, in both cohorts. Regarding regular exercisers, the ratio of regular exercisers was significantly lower among the patients with NAFLD than in those without, in both cohorts, for men. The ratio of regular exercisers was not different between the patients with NAFLD and those without in the two cohorts for women.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants with and without NAFLD

| Past | Current | NAFLD+ Past versus current |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD– (n = 3487) |

NAFLD+ (n = 792) |

p value | NAFLD– (n = 6506) |

NAFLD+ (n = 2412) |

p value | p value | |

| Men | |||||||

| Age (years) | 47.0 (16.0) | 46.0 (15.0) | 0.005 | 48.0 (17.0) | 49.0 (14.0) | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.4 (3.3) | 25.0 (3.4) | < 0.001 | 22.3 (3.4) | 25.3 (4.1) | < 0.001 | 0.140 |

| Obesity | 13.6 (474) | 50.0 (396) | < 0.001 | 13.3 (863) | 50.8 (1224) | < 0.001 | 0.716 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 119.5 (22.0) | 125.5 (21.5) | < 0.001 | 119.0 (19.5) | 124.5 (17.5) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.0 (14.5) | 79.0 (15.0) | < 0.001 | 73.5 (15.5) | 78.0 (14.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.2 (41) | 0.9 (7) | 0.468 | 0.8 (54) | 1.2 (28) | 0.155 | 0.502 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5.1 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.9) | < 0.001 | 5.5 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.8) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 18.7 (647) | 34.5 (272) | < 0.001 | 36.6 (2382) | 57.1 (1377) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.2) | < 0.001 | 0.8 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.8) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 28.2 (982) | 56.8 (450) | < 0.001 | 8.0 (521) | 23.6 (570) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | < 0.001 | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | 30.3 (1048) | 57.9 (457) | < 0.001 | 4.4 (284) | 14.7 (354) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 20.0 (5.0) | 23.0 (7.0) | < 0.001 | 16.0 (7.0) | 19.0 (11.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 16.0 (10.0) | 27.0 (20.8) | < 0.001 | 17.0 (9.0) | 27.0 (21.0) | < 0.001 | 0.316 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (IU/L) | 27.0 (32.0) | 39.0 (39.0) | < 0.001 | 20.0 (17.0) | 26.0 (19.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never smoker | 21.0 (717) | 24.4 (188) | 0.042 | 36.0 (2310) | 40.3 (959) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 24.4 (835) | 30.2 (233) | 0.001 | 33.7 (2159) | 32.9 (782) | 0.491 | 0.163 |

| Current smoker | 54.6 (1866) | 45.5 (351) | < 0.001 | 30.4 (1.947) | 26.8 (638) | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Habit of exercise | 18.6 (649) | 15.4 (122) | 0.031 | 22.7 (1462) | 13.9 (330) | < 0.001 | 0.287 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/week | 110.0 (208.0) | 36.0 (110.0) | < 0.001 | 54.0 (179.0) | 1.0 (54.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score | − 2.3 (1.1) | − 2.6 (1.1) | < 0.001 | − 2.6 (1.1) | − 2.6 (1.1) | 0.052 | < 0.001 |

| Fib4 index | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 0.035 |

| Past | Current | NAFLD+ Past versus current |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD– (n = 2303) |

NAFLD+ (n = 199) |

p value | NAFLD− (n = 6630) |

NAFLD+ (n = 691) |

p value | p value | |

| Women | |||||||

| Age (years) | 45.0 (15.0) | 52.0 (12.0) | < 0.001 | 46.0 (14.0) | 53.0 (12.0) | < 0.001 | 0.696 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.0 (3.5) | 25.0 (4.4) | < 0.001 | 20.4 (3.4) | 25.1 (5.0) | < 0.001 | 0.610 |

| Obesity | 8.5 (195) | 48.7 (97) | < 0.001 | 6.6 (434) | 48.3 (334) | < 0.001 | 0.919 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 110.5 (21.5) | 126.5 (26.3) | < 0.001 | 109.0 (19.5) | 124.0 (20.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69.0 (13.0) | 79.0 (15.8) | < 0.001 | 65.5 (14.0) | 74.0 (15.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.9 (20) | 1.5 (20) | < 0.001 | 0.4 (27) | 1.0 (7) | 0.049 | 0.573 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 4.8 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.9) | < 0.001 | 5.2 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 0.495 |

| Hyperglycemia | 7.7 (177) | 30.3 (60) | < 0.001 | 13.2 (874) | 44.7 (309) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.8) | < 0.001 | 0.5 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.6) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 7.6 (175) | 29.8 (59) | < 0.001 | 1.3 (86) | 12.0 (83) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | 35.0 (799) | 64.1 (127) | < 0.001 | 3.8 (251) | 26.8 (185) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 18.0 (4.0) | 20.0 (5.0) | < 0.001 | 14.0 (6.0) | 17.0 (9.0) | < 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 11.0 (5.0) | 19.0 (14.0) | < 0.001 | 12.0 (6.0) | 19.0 (13.0) | < 0.001 | 0.367 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (IU/L) | 11.0 (8.0) | 19.0 (20.5) | < 0.001 | 13.0 (6.0) | 17.0 (11.0) | < 0.001 | 0.006 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never smoker | 84.5 (1899) | 90.9 (180) | 0.010 | 85.9 (5663) | 85.0 (585) | 0.533 | 0.027 |

| Ex-smoker | 5.1 (115) | 0.5 (1) | < 0.001 | 8.8 (580) | 9.2 (53) | 0.754 | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 10.4 (234) | 8.6 (17) | 0.407 | 5.3 (349) | 5.8 (40) | 0.569 | 0.175 |

| Habit of exercise | 18.8 (432) | 13.6 (27) | 0.060 | 16.2 (1061) | 14.8 (100) | 0.345 | 0.664 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/week | 0.0 (36.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.002 | 1.0 (12.0) | 0.0 (1.0) | < 0.001 | 0.836 |

| NAFLD fibrosis score | − 2.2 (1.0) | − 2.2 (1.1) | 0.865 | − 2.7 (1.0) | − 2.6 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 0.239 |

| Fib4 index | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.009 | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.070 | 0.008 |

Data are expressed as median (IQR) or % (number) of subjects

p values by one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables

BMI body mass index, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Then, we investigated the differences in the characteristics of NAFLD patients between the past and current cohorts. Regarding metabolic abnormalities, the prevalence of hyperglycemia increased, whereas the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels decreased throughout these 2 decades for both genders. On the other hand, mean BMI was not different between the past and current cohort for both genders. Mean levels of AST and gamma-glutamyl transferase significantly decreased throughout the 2 decades for both genders. ALT levels did not change among genders. In addition, the proportion of exercisers decreased throughout these 2 decades for men and increased for women, although results were not statistically significant. Regarding alcohol consumption, that for men significantly decreased throughout these 2 decades, whereas that for women was not different. In addition, in men, the prevalence of fatty liver in none or minimal, light, and moderate and heavy alcohol consumer was 25.0% (547/2189), 20.7% (235/1185), and 18.9% (171/905) in the past cohort, and that in the current cohort was 33.9% (1917/5656), 25.4% (495/1946), and 28.3% (373/1316), respectively. In women, that in the past cohort was 8.6% (175/2039), 6.6% (24/364), and 12.1% (12/99), and that in the current cohort was 10.0% (624/6,234), 8.6% (67/775), and 8.5% (30/352), respectively. For men in the past cohort and women in the current cohort, as alcohol consumption increased, the prevalence of FLD tended to decrease, on the other hand, for men in the current cohort and women in the past cohort, light alcohol consumer tended to have a lower prevalence rate than the other groups. Additionally, the Fib4 index and NAFLD fibrosis score indicated that fibrosis was very mild.

The results of the multivariate analyses of factors related to NAFLD prevalence are presented in Table 3. Adjusting the OR for NAFLD prevalence for age was 0.99 (95% CI: 0.99–1.01, p = 0.894) in the past cohort, and 1.03 (1.03–1.04, p < 0.001) in the current cohort for men, whereas it was 0.99 (0.99–1.01, p = 0.979), and 1.04 (1.03–1.04, p < 0.001) in the past cohort, and 1.04 in the current cohort for women (1.03–1.04, p < 0.001). Alcohol consumption was negatively associated with the prevalence of NAFLD in both past and current cohorts in both genders. Exercise habit in the current cohort was negatively associated with the prevalence of NAFLD, and the tendency was shown in the past cohort as well, although results were not statistically significant. Adjusting the OR for NAFLD prevalence for BMI was 1.43 (1.37–1.50, p < 0.001) in the past cohort, and 1.37 (1.33–1.41, p < 0.001) in the current cohort for men, whereas for women, it was 1.33 (1.25–1.43, p < 0.001) in the past cohort and 1.39 (1.34–1.44, p < 0.001) in the current cohort. Similarly, adjusting the NAFLD prevalence the OR for obesity was 3.75 (3.01–4.66, p < 0.001) in the past cohort, and 4.36 (3.80–5.00, p < 0.001) in the current cohort for men. For women, the OR was 5.25 (3.59–7.67, p < 0.001) in the past cohort, and 8.35 (6.76–10.31, p < 0.001) in the current cohort.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with the prevalence of NAFLD

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Current | Past | Current | |||||

| OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | |

| Men | ||||||||

| Age, years old | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) | 0.894 | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) | 0.979 | 1.04 (1.03–1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/week | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 |

| Regular exercise | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.289 | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | < 0.001 | 0.85 (0.65–1.12) | 0.258 | 0.66 (0.56–0.77) | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 1.04 (1.04–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.05–1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.06–1.07) | < 0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.18 (0.89–1.56) | 0.262 | 0.97 (0.83–1.13) | 0.682 | 1.13 (0.86–1.49) | 0.388 | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | 0.648 |

| Current smoker | 0.81 (0.62–1.06) | 0.119 | 0.73 (0.62–0.86) | < 0.001 | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | 0.017 | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | 0.028 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.43 (1.37–1.50) | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.33–1.41) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Systolic blood pressure, 1 mmHg | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.357 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Fasting plasma glucose, 1 mmol/L | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) | < 0.001 | 1.32 (1.20–1.46) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Triglycerides, 1 mmol/L | 1.37 (1.24–1.52) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.19–1.45) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| HDL-cholesterol, 1 mmol/L | 0.49 (0.32–0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.36 (0.29–0.45) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Obesity | – | – | – | – | 3.75 (3.01–4.66) | < 0.001 | 4.36 (3.80–5.00) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | – | – | – | – | 1.48 (0.56–3.93) | 0.431 | 1.00 (0.53–1.87) | 0.900 |

| Hyperglycemia | – | – | – | – | 1.71 (1.36–2.15) | < 0.001 | 1.76 (1.56–2.00) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | – | – | – | – | 2.49 (2.01–3.07) | < 0.001 | 2.61 (2.17–3.15) | < 0.001 |

| Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | – | – | – | – | 1.49 (1.21–1.84) | < 0.001 | 1.63 (1.30–2.04) | < 0.001 |

| Women | ||||||||

| Age, years old | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.023 | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/week | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 |

| Regular exerciser | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | 0.217 | 0.89 (0.67–1.19) | 0.427 | 0.69 (0.41–1.15) | 0.153 | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 0.035 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 1.05 (1.05–1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 0.05 (0.01–0.52) | 0.013 | 1.26 (0.87–1.82) | 0.218 | 0.06 (0.01–0.51) | 0.010 | 1.31 (0.93–1.84) | 0.120 |

| Current smoker | 1.17 (0.63–2.19) | 0.623 | 0.95 (0.59–1.52) | 0.825 | 1.03 (0.55–1.92) | 0.927 | 1.12 (0.73–1.73) | 0.604 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.33 (1.25–1.43) | < 0.001 | 1.39 (1.34–1.44) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Systolic blood pressure, 1 mmHg | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.673 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Fasting plasma glucose, 1 mmol/L | 1.64 (1.27–2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.90 (1.55–2.33) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Triglycerides, 1 mmol/L | 1.60 (1.19–2.14) | 0.002 | 2.38 (1.89–3.00) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| HDL-cholesterol, 1 mmol/L | 0.39 (0.20–0.76) | 0.005 | 0.33 (0.24–0.45) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Obesity | – | – | – | – | 5.25 (3.59–7.67) | < 0.001 | 8.35 (6.76–10.31) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | – | – | – | – | 1.51 (0.27–8.33) | 0.640 | 1.02 (0.33–3.19) | 0.975 |

| Hyperglycemia | – | – | – | – | 2.33 (1.50–3.62) | < 0.001 | 2.91 (2.37–3.58) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | – | – | – | – | 1.70 (1.09–2.66) | 0.020 | 2.69 (1.76–4.10) | < 0.001 |

| Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | – | – | – | – | 2.00 (1.37–2.91) | < 0.001 | 4.48 (3.38–5.94) | < 0.001 |

CI confidential interval, HDL high-density lipoprotein, NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, OR odds ratio

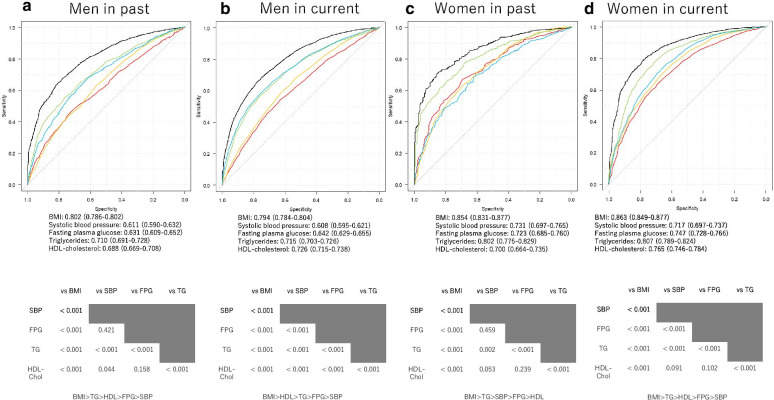

Additionally, the ROC analyses and AUC for several risk factors for NAFLD prevalence are presented in Fig. 2. Comprehensively, in both genders for both cohorts, BMI was most significantly associated with the prevalence of NAFLD.

Fig. 2.

Area under the curve (AUC) for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) [95% confidence interval (CI)] of several factors for NAFLD incidence. Upper figure indicates ROC curve, AUC and cut-off value for each factor. Black line indicates body mass index (BMI); red line indicates systolic blood pressure (SBP); yellow line indicates fasting plasma glucose (FPG); green line indicates triglycerides (TG); and blue line indicates high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Lower figure shows results of the comparison among each factor. a Men in the past cohort. b Men in the current cohort. c Women in the past cohort. d Women in the current cohort. a AUC for BMI was 0.802 (95% CI 0.786–0.802, p < 0.001), and that of SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 0.611 (0.590–0.632, p < 0.001), 0.631 (0.609–0.652, p < 0.001), 0.710 (0.691–0.728, p < 0.001), and 0.688 (0.669–0.728, p < 0.001) in men of the past cohort, respectively. Cut-off value for BMI, SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 23.2 kg/m2, 116.5 mmHg, 5.3 mmol/l, 1.3 mmol/l, and 1.0 mmol/l, respectively. b AUC for BMI was 0.794 (95% CI 0.784–0.804, p < 0.001), and for SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 0.608 (0.595–0.621, p < 0.001), 0.642 (0.629–0.655, p < 0.001), 0.715 (0.703–0.726, p < 0.001), and 0.726 (0.715–0.738, p < 0.001) for men in the current cohort, respectively. Cut-off value for BMI, SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 23.3 kg/m2, 118.5 mmHg, 5.6 mmol/l, 0.8 mmol/l, and 1.5 mmol/l, respectively. c AUC for BMI was 0.854 (95% CI 0.831–0.877, p < 0.001), and for SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 0.731 (0.697–0.765, p < 0.001), 0.723 (0.685–0.760, p < 0.001), 0.802 (0.775–0.829, p < 0.001), and 0.700 (0.664–0.735, p < 0.001) for women in the past cohort, respectively. Cut-off value for BMI, SBP, FPG, TG, or HDL cholesterol was 22.4 kg/m2, 116.0 mmHg, 5.0 mmol/l, 1.2 mmol/l, and 1.3 mmol/l, respectively. d AUC for BMI was 0.863 (95% CI 0.849–0.877, p < 0.001), and for SBP, FPG, TG, and HDL cholesterol was 0.717 (0.697–0.737, p < 0.001), 0.747 (0.728–0.766, p < 0.001 vs. BMI), 0.807 (0.789–0.824, p < 0.001), and 0.765 (0.746–0.784, p < 0.001) for women in the past cohort, respectively. Cut-off value for BMI, SBP, FPG, TG, or HDL cholesterol was 22.5 kg/m2, 113.0 mmHg, 5.3 mmol/l, 0.7 mmol/l, and 1.6 mmol/l, respectively

Since obesity was strongly associated with NAFLD prevalence, we investigated the differences in all patients’ characteristics with or without obesity and those who having NAFLD with and without obesity (Additional file 1: Table S2 and S3). BMI in the current cohort was significantly lower than that in the past cohort in non-obese patients in both genders. Non-obese, as well as obese men with NAFLD in the current cohort had a higher prevalence of hyperglycemia, with a lower prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels when compared with the past cohort. Non-obese women with NAFLD showed a similar tendency.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the prevalence of NAFLD significantly increased in both men and women throughout the 2 decades. The prevalence of hyperglycemia in NAFLD patients significantly increased through these 2 decades in men. For women, only the prevalence of hyperglycemia in NAFLD patients significantly increased throughout the 2 decades. Per capita food consumption has increased significantly in the world, from an average of 2360 kcal/person/day in the mid-1960s to 2800 kcal/person/day today, according to a study by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [27]. Additionally, Wehmeyer et al. [28] reported that excessive calorie intake is associated with NAFLD. This increased caloric intake might be a significant contributor to the global rise of prevalence of NAFLD. On the other hand, in contrast to the global trend, the Japanese census showed a gradual decline in energy intake since its peak in 1975, as well as a decline in protein intake in women [29]. In men, the increased incidence of NAFLD despite the increased exercise habits may be due mainly to dietary intake changes not assessed in this study. The results of the Japanese census in 1996 showed that the daily fat intake for men, 63.0 ± 27.9 g, was significantly lower than that in 2018, 65.9 ± 29.2 g. In 1996, the daily fat intake for women, 55.2 ± 24.0 g, was not different from that in 2018, 55.5 ± 23.1 g [29]. These data suggest that the increase in NAFLD could be related to increased fat intake in men [30–32], whereas the main cause of increase in NAFLD in women could be due to the decreased exercise habits and not nutrient intake [33]. It was suggested that the lower mean BMI might be due to lower muscle mass [34]. In addition, Wada reported that waist circumference increased in the 55–69 age group of men throughout 2 decades [35]. Moreover, there were an increasing number of cases such as sarcopenia with increased visceral fat even though they were non-obese evaluated by BMI [36], which might be one of the reasons why the number of men with NAFLD is increasing, even though the BMI of men with NAFLD is not significantly different between past and present cohorts.

Among the metabolic syndrome components, obesity was most associated with the prevalence of NAFLD in men and women for both cohorts. A previous study reported the association between obesity and elevated circulating levels of pro-inflammatory factors, including cytokines or hormones, such as interleukin-1 and tumor-necrosis-factor. Lipid dysregulation in the liver, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress interact to promote fat accumulation in the liver [37]. Specifically, visceral fat accumulation is associated with NAFLD incidence because the venous splanchnic blood flow directly leads to a high exposure of liver tissue to increased free fatty acids and triglycerides by lipolysis [38]. On the other hand, triglycerides were lower and HDL-cholesterol was higher in men for current cohort than for the past cohort. Decreased serum triglycerides might be due to decreased alcohol consumption in patients with NAFLD. Increased HDL cholesterol might be due to increased prevalence of exercise.

In addition, the number of non-obese patients with NAFLD increased throughout these 2 decades. They became leaner than in the past cohort. However, the number of patients with impaired glucose tolerance increased. These results indicate that non-obese NAFLD and impaired glucose tolerance are closely associated with each other. We have previously reported that non-obese patients with NAFLD had a higher risk of diabetes than obese patients without NAFLD [21]. In the future, it is necessary to clarify the onset mechanisms of non-obese NAFLD.

Furthermore, the proportion of current smoker with NAFLD in the current cohort significantly decreased in men and tended to decrease in women. In addition, current smoking was negatively associated with the prevalence of NAFLD. Taken together, the decreased proportion of current smoker might be associated with the increased prevalence of NAFLD in the current cohort. Although several studies reported that smoking is a risk factor of incident NAFLD [39]40, it has been reported that smoking is not associated with the prevalence of NAFLD [41]42. Possible explanation is that smoking is associated with decreased food intake [43] and may decrease the prevalence of NAFLD. In addition, there is a possibility that the effect of the other risk factors on NAFLD might be higher than that of smoking.

The strengths of our study include using the same standardized diagnosis for fatty liver [12], standardized questionnaire for lifestyle factors, and the relatively large population-based longitudinal research design. Our study also has some limitations. Limited diagnostic accuracy to detect mild degree hepatic steatosis is taken as one limitation of abdominal ultrasonography for the evaluation of fatty liver [44], and liver steatosis was not assessed using the ultrasound parameters or scores. However, we assessed fatty liver on the basis of standardized diagnostic criteria, and we could have evaluated a certain level of fatty liver. A liver biopsy was required for a more accurate diagnosis for NAFLD and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In addition, self-reported alcohol intake might be inaccurate, especially heavy alcohol consumer, although several studies revealed that these consumption measures can be used with considerable confidence [45]4647. Second, we did not have data for plasma insulin concentrations to evaluate insulin resistance, such as homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance. If we could evaluate insulin resistance, we could more accurately assess the relationship between alcohol intake and insulin resistance. Third, we did not have data for waist circumference, which are markers of visceral fat [48]. Thus, we cannot evaluate the obesity and NAFLD rigorously. Fourth, we also had a limited ability to examine different levels of physical activity. If we can assess the frequency and intensity of exercise, a more accurate analysis would be possible. Fifth, we did not have dietary data available. Sixth, several NAFLD-associated SNPs, such as rs738409, a single variant in the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3, rs12447924 and rs12597002, cholesteryl ester transfer protein, rs58542926 C, a single nucleotide polymorphism in transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2, rs368234815 TT, the interferon lambda 4, and deficiency of the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase [49–51]. Further investigation of SNPs in future studies will clarify the pathogenesis of NAFLD in the Japanese population. Moreover, compared to the total Japanese population, the participants in the past cohort study had fewer people under 29 and over 60 years old, and the participants in the current cohort had fewer people under 29 and over 65 years old. As the characteristics of the participants in this cohort study, most of them are annual medical examinations as instructed by their workplaces, therefore, the working-age population tends to be larger. Finally, the generalizability of our study to non-Japanese populations is uncertain.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed that throughout these 2 decades, the prevalence of NAFLD significantly increased, and that obesity was the most associated factor with the prevalence of NAFLD. Thus, body weight management is essential as a treatment alternative for NAFLD. However, non-obese individuals and NAFLD also increased in these 2 decades. Therefore, it would have been much more solid a study analyzing trajectories on disease prevalence based un multiple cohorts instead of two cohorts taken some 20 years apart, and further studies targeting these non-obese NAFLD individuals are needed.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Summary of all additional Tables S1–S3. Table S1. Characteristics of non-alcoholic participants. Table S2. Characteristics of study participants with and without obesity. Table S3. Characteristics of study participants having NAFLD with and without obesity.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the staff members in the medical health checkup center at Asahi University Hospital. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Authors' contributions

T.O. contributed to the data research and analyses and wrote the manuscript. Y.H. originated and designed the study, analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. M.H. contributed to data research and the manuscript organization and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.O. and T.K. contributed to originate the study, data research and contributed to the discussion. M.F. analyzed the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in the writing of the manuscript and approved the manuscript's final version.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee approved the current version of the NAGALA study (IRB Number: 2018-09-01). The study design was opt-out sampling. Participants who underwent health checkups at the Asahi University Hospital were contacted to volunteer to take part in this research. Subjects were excluded only if unwilling to participate. This study was approved by Asahi University Hospital Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Y. Hashimoto received grants from Asahi Kasei Corporation outside the submitted work. M. Fukui received grants from AstraZeneca plc, Astellas Pharma Inc., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd., Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. The sponsors were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article. The authors declare that although they are affiliated with a department that is supported financially by pharmaceutical company, the authors received no current funding for this study, and this does not alter their adherence to all the journal policies on sharing data and materials. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bellentani S, Scaglioni F, Marino M, Bedogni G. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28:155–161. doi: 10.1159/000282080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milić S, Lulić D, Štimac D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: biochemical, metabolic and clinical presentations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9330–9337. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:330–344. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–131. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radu C, Grigorescu M, Crisan D, Lupsor M, Constantin D, Dina L. Prevalence and associated risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in hospitalized patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angulo P. GI epidemiology: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:883–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou X, Zhu Y, Lu H, Chen H, Li Q, Jiang S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease’s prevalence and impact on alanine aminotransferase associated with metabolic syndrome in the Chinese. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:722–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, Murray CJ, Naghavi M. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang DQ, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Abenavoli L, Milic N, Di Renzo L, Preveden T, Medić-Stojanoska M, De Lorenzo A. Metabolic aspects of adult patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7006–7016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i31.7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nakagawa T, Taniguchi H, Fujii K, et al. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:722–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaguchi M, Takeda N, Kojima T, Ohbora A, Kato T, Sarui H, et al. Identification of individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by the diagnostic criteria for the metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1508–1516. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i13.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jimba S, Nakagami T, Takahashi M, Wakamatsu T, Hirota Y, Iwamoto Y, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with impaired glucose metabolism in Japanese adults. Diabet Med. 2005;22:1141–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Prevalence, gender, ethnic variations, and prognosis of NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(Suppl 1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, Bantel H, Bellentani S, Caballeria J, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016–2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69:896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuda Y, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Fukuda T, Nakamura N, Ohbora A, et al. Triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is an independent predictor of incident fatty liver; a population-based cohort study. Liver Int. 2016;36:713–720. doi: 10.1111/liv.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCullough AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Ohshima Y, Ohbora A, Kato T, et al. The modest alcohol consumption reduces the incidence of fatty liver in men: a population-based large-scale cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:546–552. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryu S, Chang Y, Kim D-I, Kim WS, Suh B-S. Glutamyltransferase as a predictor of chronic kidney disease in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic Korean men. Clin Chem. 2006;53:71–77. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda T, Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Hashimoto Y, Ohbora A, Kato T, et al. The impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in non-overweight individuals. Liver Int. 2015 doi: 10.1111/liv.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashimoto Y, Tanaka M, Kimura T, Kitagawa N, Hamaguchi M, Asano M, et al. Hemoglobin concentration and incident metabolic syndrome: a population-based large-scale cohort study. Endocrine. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846–854. doi: 10.1002/hep.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumida Y, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Itoh Y, Ono M, Fujii H, et al. Validation of the FIB4 index in a Japanese nonalcoholic fatty liver disease population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y, Harano Y, Fujii K, Nakajima T, et al. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2708–2715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musso G, Gambino R, Tabibian JH, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, Hamaguchi M, et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. World agriculture: towards 2015/2030. http://www.fao.org/3/y4252e/y4252e04.htm. Accessed 12 Jan 2021.

- 28.Wehmeyer MH, Zyriax BC, Jagemann B, Roth E, Windler E, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Lohse AW, Kluwe J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with excessive calorie intake rather than a distinctive dietary pattern. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(23):e3887. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. National health and nutrition survey. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html. Accessed 16 April 2020.

- 30.Golay A, Bobbioni E. The role of dietary fat in obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(Suppl 3):S2–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabriel AS, Ninomiya K, Uneyama H. The role of the Japanese traditional dietin healthy and sustainable dietary patterns around the world. Nutrients. 2018;10:E173. doi: 10.3390/nu10020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami K, Livingstone MBE, Sasaki S. Thirteen-year trends in dietary patterns among Japanese adults in the national health and nutrition survey 2003–2015: continuous westernization of the Japanese diet. Nutrients. 2018;10:994. doi: 10.3390/nu10080994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiklund P. The role of physical activity and exercise in obesity and weight management: time for critical appraisal. J Sport Health Sci. 2016;5:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graf CE, Pichard C, Herrmann FR, Sieber CC, Zekry D, Genton L. Prevalence of low muscle mass according to body mass index in older adults. Nutrition. 2017;34:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wada T. Twenty years of transitional changes of waist circumference first introduced as a basic item in the Ningen Dock in Japan. HEP. 2020;47:539–545. doi: 10.7143/jhep.47.539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Obora A, Kojima T, Fukui M. Ectopic fat obesity presents the greatest risk for incident type 2 diabetes: a population-based longitudinal study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2019;43:139–148. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson AMF, Olefsky JM. The origins and drivers of insulin resistance. Cell. 2013;152:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazaki Y, DeFronzo RA. Visceral fat dominant distribution in male type 2 diabetic patients is closely related to hepatic insulin resistance, irrespective of body type. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:44. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung HS, Chang Y, Kwon MJ, et al. Smoking and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:453–463. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim NH, Jung YS, Hong HP, et al. Association between cotinine-verified smoking status and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018;38:1487–1494. doi: 10.1111/liv.13701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chavez-Tapia NC, Lizardi-Cervera J, Perez-Bautista O, Ramos-Ostos MH, Uribe M. Smoking is not associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5196–5200. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilmaz Y, Yonal O, Kurt R, Avsar E. Cigarette smoking is not associated with specific histological features or severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:391–392. doi: 10.1002/hep.23718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jo YH, Talmage DA, Role LW. Nicotinic receptor-mediated effects on appetite and food intake. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:618–632. doi: 10.1002/neu.10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SS, Park SH, Kim HJ, Kim SY, Kim M-Y, Kim DY, et al. Non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis: prospective comparison of the accuracy of imaging examinations. J Hepatol. 2010;52:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams GD, Aitken SS, Malin H. Reliability of self-reported alcohol consumption in a general population survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:223–227. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Northcote J, Livingston M. Accuracy of self-reported drinking: observational verification of 'last occasion' drink estimates of young adults. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:709–713. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grundy SM, Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Vega GL. Waist circumference as measure of abdominal fat compartments. J Obes. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/454285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishioji K, Mochizuki N, Kobayashi M, Kamaguchi M, Sumida Y, Nishimura T, Yamaguchi K, Kadotani H, Itoh Y. The impact of PNPLA3 rs738409 genetic polymorphism and weight Gain ≥10 kg after age 20 on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese Japanese individuals. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0140427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albhaisi S, Chowdhury A, Sanyal AJ. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals. JHEP Rep. 2019;1(4):329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahadi M, Molooghi K, Masoudifar N, Namdar AB, Vossoughinia H, Farzanehfar M. A review of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese and lean individuals. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jgh.15353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Summary of all additional Tables S1–S3. Table S1. Characteristics of non-alcoholic participants. Table S2. Characteristics of study participants with and without obesity. Table S3. Characteristics of study participants having NAFLD with and without obesity.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.