ABSTRACT/SUMMARY

One million patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) live in the US. They have a lifelong risk of developing heart failure. Current concepts do not sufficiently address mechanisms of heart failure development specifically for these patients. We show that cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure is increased in tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary stenosis (ToF/PS), a common form of CHD. Labeling of a ToF/PS baby with isotope-tagged thymidine showed cytokinesis failure after birth. We used single-cell transcriptional profiling to discover that the underlying mechanism is repression of the cytokinesis gene ECT2, and show that this is downstream of β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR). Inactivation of the β-AR genes and administration of the β-blocker propranolol increased cardiomyocyte division in neonatal mice, which increased the endowment and conferred benefit after myocardial infarction in adults. Propranolol enabled the division of ToF/PS cardiomyocytes. These results suggest that β-blockers should be evaluated for increasing cardiomyocyte division in patients with ToF/PS and other types of CHD.

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect. Improvements in diagnosis and treatment of CHD have increased survival, and 1 million patients live in the US with CHD1. Patients with CHD have a high lifetime risk for developing heart failure, and current thinking about this is based on research on heart failure in adult patients1. We have considered the possibility that CHD may alter cellular growth of the myocardium, i.e., cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation, because these mechanisms are active in infants and children without heart disease2, 3.

Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary stenosis (ToF/PS) is a common form of CHD with relatively uniform structural defects (anterior deviation of the infundibulum, pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy). Despite extensive progress in understanding the genetic causes of CHD, the majority of ToF/PS remains genetically unexplained4. Infants and children with ToF/PS rarely have heart failure, but it is a well-documented cause of morbidity and mortality in adults5–12. Current thinking is that the sequelae of cardiac surgery cause an increased risk of heart failure. However, classical studies showed severe cardiomyocyte changes in ToF/PS patients prior to surgery13, 14, but did not examine cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation. This suggested to us that myocardial changes happen before surgery. We have considered this possibility and found changes in cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation in ToF/PS.

Recent studies have shown that cardiomyocytes divide in human infants and children in contrast to the extremely low cardiomyocyte division rate in adults2, 3, 15. When cardiomyocytes stop proliferating, they undergo incomplete cell cycles, leading to binucleated cardiomyocytes. Although the mechanisms of formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes are unknown, it is thought that they do not divide further16. Mice and rats form binucleated cardiomyocytes in the first week after birth17–19. Zebrafish have only mononucleated cardiomyocytes, which can divide and regenerate myocardium20, which has led to the hypothesis that a high percentage of mononucleated cardiomyocytes is the foundation for myocardial regeneration. However, humans have 70% mononucleated cardiomyocytes and yet do not regenerate myocardium. In addition, cardiomyocytes differentiate by endocycling, which increases the DNA content of nuclei without nuclear division, i.e., they become polyploid. Humans show a high degree of endocycling around 10 years after birth2, 3, 15. Two recent papers have altered the percentage of binucleated cardiomyocytes in mice and zebrafish, but this resulted in additional large changes of polyploid cardiomyocytes21, 22. Although multiple studies have suggested that cardiomyocytes become binucleated by incomplete cytokinesis23–25, the precise mechanisms and relevance of cardiomyocyte binucleation are still unknown. During cytokinesis, a contractile ring forms at the future division plane26. Contraction of this ring is triggered by the cytokinesis protein ECT2, a RhoA guanine-nucleotide exchange factor. RhoA-GTP activates, via Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK), non-muscle myosin II, which constricts the cleavage furrow.

Different pathways regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation, with the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway taking a central position27. The Hippo pathway is regulated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), and, in the heart, activated by β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR)28. β-AR regulate cardiomyocyte contractile function, by adjusting the intracellular second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)29. In CHD, and specifically in ToF/PS, β-AR signaling is overactivated30–34. Adrenergic signaling has also been evaluated in the context of heart regeneration in mice35, 36 and cell cycle activity in cultured rat cardiomyocytes37–39; however, these results were obtained without genetic disruption of signaling pathways. Our results extend these findings by demonstrating a function of β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR) signaling in regulating cardiomyocyte cytokinesis in vivo.

Using formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes as read-out for the definitive endpoint of cell division, we discovered extensive changes of cardiomyocyte proliferation in ToF/PS. We identified the mechanisms of formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes, establishing a new connection between β-AR signaling and regulation of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis.

RESULTS

Infants with Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary stenosis have increased binucleated cardiomyocytes

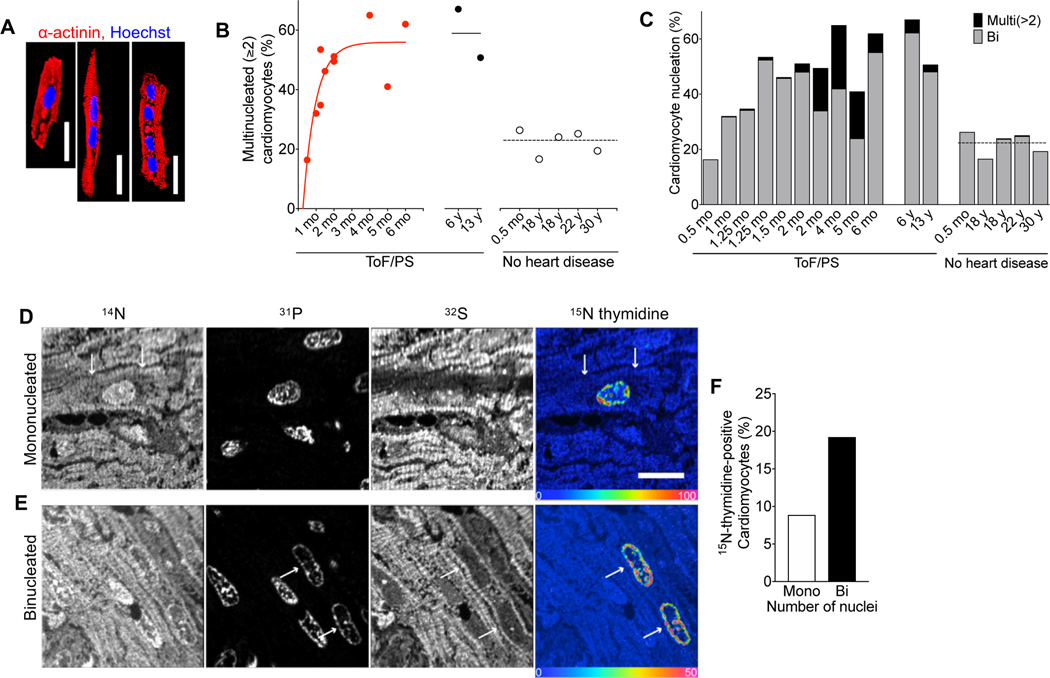

We examined samples from the right ventricle of patients with ToF/PS and made the surprising observation that the percentage of binucleated cardiomyocytes was increased to 50–60% (Fig. 1A–C), suggesting extensively increased cytokinesis failure. The temporal pattern of this increase shows that babies with ToF/PS were born with the appropriate percentage of 20% binucleated cardiomyocytes2, 3, but that the increase happened in the first 6 months after birth (Fig. 1B). All ToF/PS patients > 2 months had cardiomyocytes with > 2 nuclei, a very rare phenotype in humans without heart disease (Fig. 1C), suggesting that multiple serial cytokinesis failures occurred. Bi- and multi-nucleated cardiomyocytes were present in 6 and 13-year-old patients, i.e., after the decline of cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity to the very low levels present in adults. This shows that bi- and multi-nucleated cardiomyocytes generated in the first 6 months after birth live for at least one decade. To directly assess the generation of mono- and binucleated cardiomyocytes, we labeled a 1-month-old ToF/PS baby with 15N-thymidine and examined uptake and retention with multiple-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS) at 7 months of age (Fig. 1D, E). 15N-thymidine labeling was twice as high in the binucleated cells compared to mononucleated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1F), indicating extensive cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure corresponding to a 20–30% reduction of the number of cardiomyocytes (endowment). These findings motivated us to determine the mechanisms controlling cytokinesis in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1. Cardiomyocytes in infants with Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary stenosis (ToF/PS) fail to divide.

(A-C) Patients with Tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary stenosis (ToF/PS) show an increased proportion of multinucleated (≥2) cardiomyocytes (filled symbols and solid lines in B). Each symbol in (B) and bar in (C) represents one human heart (ToF/PS: n = 12; No heart disease: n = 5). (D-F) A 4-week-old infant with ToF/PS was labeled with oral 15N-thymidine. Myocardium was analyzed by multiple-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS) at 7 months. (D-E) 31P reveals nuclei and 32S morphologic detail, including striated sarcomeres. Nuclei are dark in the 32S image. The 15N/14N ratio image reveals 15N-thymidine incorporation. The blue end of the scale is set to natural abundance (no label uptake) and the upper bound of the rainbow scale is set to 50% above natural abundance. The white arrows in (D) indicate the boundaries of a labelled mononucleated cardiomyocyte and in (E) the nuclei of a binucleated cardiomyocyte. (F) The percentage of labeled binucleated cardiomyocytes is higher than mononucleated cardiomyocytes (Mononucleated cardiomyocytes analyzed: n = 282; 15N+ mononucleated cardiomyocytes: n = 25; Binucleated cardiomyocytes analyzed: n = 104 (208 total nuclei); 15N+ binucleated cardiomyocytes: n = 20 (40 total nuclei)), indicating that this patient experienced extensive cytokinesis failure. Scale bar: 20 μm (A), 10 μm (D).

Cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes is associated with low levels of the Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor Ect2

To determine the cellular mechanisms of cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes, we performed live cell imaging with neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes that undergo binucleation (NRVM, Fig. 2A, Video S1). Cleavage furrow ingression was observed in 80% of the cardiomyocytes studied, followed by cleavage furrow regression. We used a transgenic mouse model expressing the fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator (FUCCI) to highlight cell cycle progression 40, which showed normal cell cycle progression until cleavage furrow regression (Videos S2, S3). This finding demonstrates that failure of abscission generates binucleates from mononucleated cardiomyocytes.

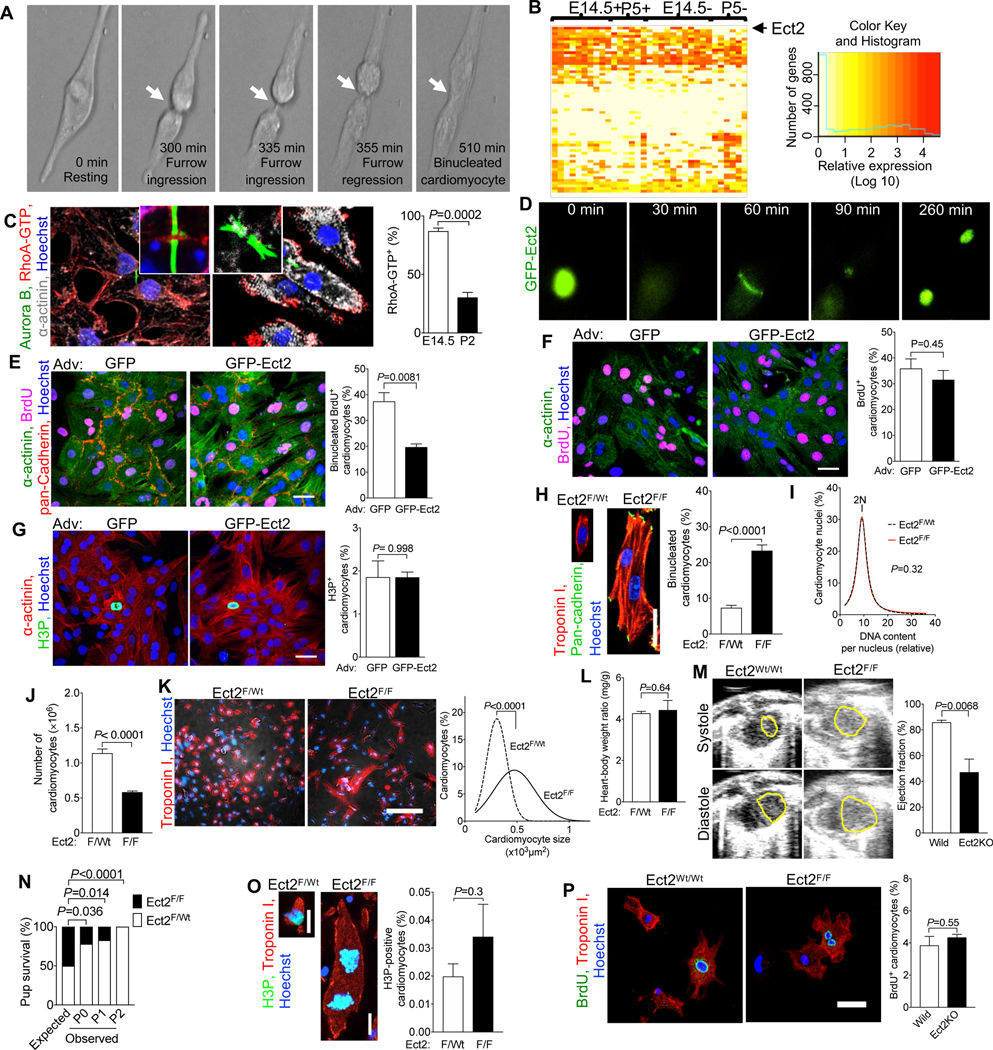

Figure 2. Ect2 levels regulate cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and Ect2 gene inactivation lowers endowment and is lethal in mice.

(A) Live cell imaging of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRVM, P2-P3, 52 cardiomyocytes) shows that cleavage furrow regression precedes formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes, corresponding to Video S1. Cleavage furrow ingression is between 300–335 min, regression at 355 min, and formation of a binucleated cardiomyocyte at 510 min. (B) Transcriptional profiling of single cycling (+) and not cycling (−) cardiomyocytes at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) and 5 days after birth (P5) reveals that of 61 Dbl-homology family RhoGEF, Ect2 is significantly repressed in cycling P5 cardiomyocytes (P <0.05). (C) Binucleating cardiomyocytes exhibit lower RhoA activity (RhoA-GTP) at the cleavage furrow (E15.4: 59 midbodies; P2: n = 56 midbodies). (D-G) NRVM were transduced with Adv-CMV-GFP-Ect2. Live cell imaging shows appropriate and dynamic localization of GFP-ECT2 in cycling NRVM (D, corresponding to Video S4), reduced cytokinesis failure and reduced generation of binucleated cardiomyocytes. (F, G) Overexpression of GFP-Ect2 does not alter cardiomyocyte S- (F, GFP: n = 407; GFP-Ect2: n = 285) or M-phase (G, GFP: n = 432; GFP-Ect2: n = 443). (H-P) Ect2 gene inactivation in the αMHC-Cre; Ect2F/F mice at P1 (H-O) showed increased binucleated cardiomyocytes (H, Ect2F/wt n = 6, Ect2F/F n = 6 hearts) without change of DNA content per nucleus (I, Ect2F/wt n = 642 cardiomyocytes, Ect2F/F n = 647 cardiomyocytes), and a 50% lower cardiomyocyte endowment (J, Ect2F/wt n = 12, Ect2F/F n = 5 hearts). The reduced endowment triggers compensatory cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (K, Ect2F/wt n = 1,138 cardiomyocytes from 6 hearts, Ect2F/F n = 1,015 cardiomyocytes from 6 hearts), without change of heart weight (L, Ect2F/wt n = 14, Ect2F/F n = 6 hearts). (M, N) The lower cardiomyocyte endowment leads to myocardial dysfunction at P0 (M, left ventricular endocardium outlined in yellow, Ect2wt/wt n = 4, Ect2F/F n = 3 mice) and lethality before P2 (N, Video S5), but does not alter the M-phase (O, Ect2F/wt n = 6, Ect2F/F n = 6 hearts) and cell cycle entry (P, BrdU uptake, Ect2flox gene inactivation with αMHC-MerCreMer, tamoxifen DOL 0, 1, 2, followed by 3 days culture). Statistical significance was tested with Student’s t- test if not specified, and Fisher’s exact test (N). Scale bars 30 μm (E, P), 50 μm (F, G), 100 μm (K).

To identify the molecular mechanisms of cleavage furrow regression, we separated cycling from non-cycling cardiomyocytes and took a single cell transcriptional profiling approach to compare the expressed genes (Fig. S1). We isolated embryonic (Embryonic day 14.5, E14.5) and neonatal (Postnatal day 5, P5) cardiomyocytes and identified cycling cardiomyocytes with the mAG-hGem reporter of the FUCCI indicator 40(Fig. S2). We performed deep, genome-wide, single-cell transcriptional analysis with the Eberwine method 41–43, followed by validation of the results (Fig. S3). Because RhoA activation is required for cleavage furrow constriction, we examined the expression of Dbl-homology Rho-Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEF) in the single cell transcriptional dataset (Fig. 2B, Table S1). Ect2 mRNA was present in cycling E14.5 cardiomyocytes but not in binucleating P5 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2B). Other genes controlling cytokinesis, i.e., Racgap1 (inactivating RhoA), RhoA, Anillin, Aurkb, and Mklp1, were present in P5 cycling cardiomyocytes (Fig. S4), indicating that Ect2 is uniquely regulated. In accordance with the decreased Ect2 levels, active RhoA (RhoA-GTP) was decreased in binucleating cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results show insufficient Ect2 levels in cardiomyocytes lead to less RhoA activation, weakening their cleavage furrows26.

We tested whether increasing Ect2 expression enables cardiomyocyte abscission by expressing GFP-Ect2 44. Live cell imaging showed the functionality of GFP-ECT2 in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2D and Video S4) and increased cardiomyocyte abscission (Fig. 2E) without inducing apoptosis (Fig. S6). GFP-Ect2 did not alter cardiomyocyte BrdU uptake (Fig. 2F) or H3P (Fig. 2G). In conclusion, increasing Ect2 expression in cardiomyocytes has a specific effect on abscission without changing cell cycle entry or progression.

Lowering Ect2 expression reduces cardiomyocyte endowment and heart function

We next tested the hypothesis that lowering the expression of Ect2 induces cytokinesis failure in vivo. To this end, we inactivated the Ect2flox gene in mice with αMHC-Cre 45, (Fig. S6A). αMHC-Cre; Ect2flox/flox mice showed a 3.2-fold increase of binucleated cardiomyocytes (23.3%, Fig. 2H), compared to αMHC-Cre; Ect2wt/flox mice (7.4%, P<0.0001), at P1. Ect2 inactivation did not change the DNA contents of nuclei (Fig. 2I). αMHC-Cre+;Ect2flox/flox pups had 583,000 ± 15,379 cardiomyocytes (n=5 hearts) at P1, a 49% decrease compared to αMHC-Cre+;Ect2wt/flox mice (1,140,833 ± 58,341 cardiomyocytes, n=12 hearts, P<0.0001, Fig. 2J). The mean cardiomyocyte size in αMHC-Cre;Ect2flox/flox mice was increased by 65% (Fig. 2K). These results show that the lower endowment in αMHC-Cre;Ect2flox/flox pups triggered cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and not a compensatory increase in cell cycling. The heart weight was unchanged (Fig. 2L). Echocardiography showed that αMHC-Cre+; Ect2flox/flox had a significantly decreased heart function, measured by ejection fraction (EF=49.6%), compared with control (EF=85.9%, Fig. 2M, Video S6 and S7). All the αMHC-Cre+; Ect2flox/flox died before P2 (Fig. 2N, S6B). Ect2flox inactivation did not change cardiomyocyte M-phase activity, as measured by quantification of H3P-positive nuclei (Fig. 2O). We observed binucleated Ect2flox/flox cardiomyocytes with both nuclei being in M-phase, indicating that forcing cytokinesis failure does not prevent entry into another cell cycle and advancement to karyokinesis (Fig. 2O). This finding suggests a mechanism for how cardiomyocytes with four and more nuclei are generated, i.e., by serial karyokinesis and failure of abscission. To determine whether Ect2 gene inactivation alters cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry, we inactivated an Ect2flox46 gene with αMHC-MerCreMer47 (tamoxifen P0, 1, 2) in vivo, thus circumventing the lethality of inactivating with αMHC-Cre. We isolated cardiomyocytes at P2 and cultured for 3 days in the presence of BrdU. Ect2 inactivation did not alter cell cycle entry (Fig. 2P) or cell viability (Fig. S9). In conclusion, Ect2 inactivation induced cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes, which decreased endowment by 50% and led to severely decreased ejection fraction and death.

ß-adrenergic receptors control cardiomyocyte abscission and endowment by regulating the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway and Ect2

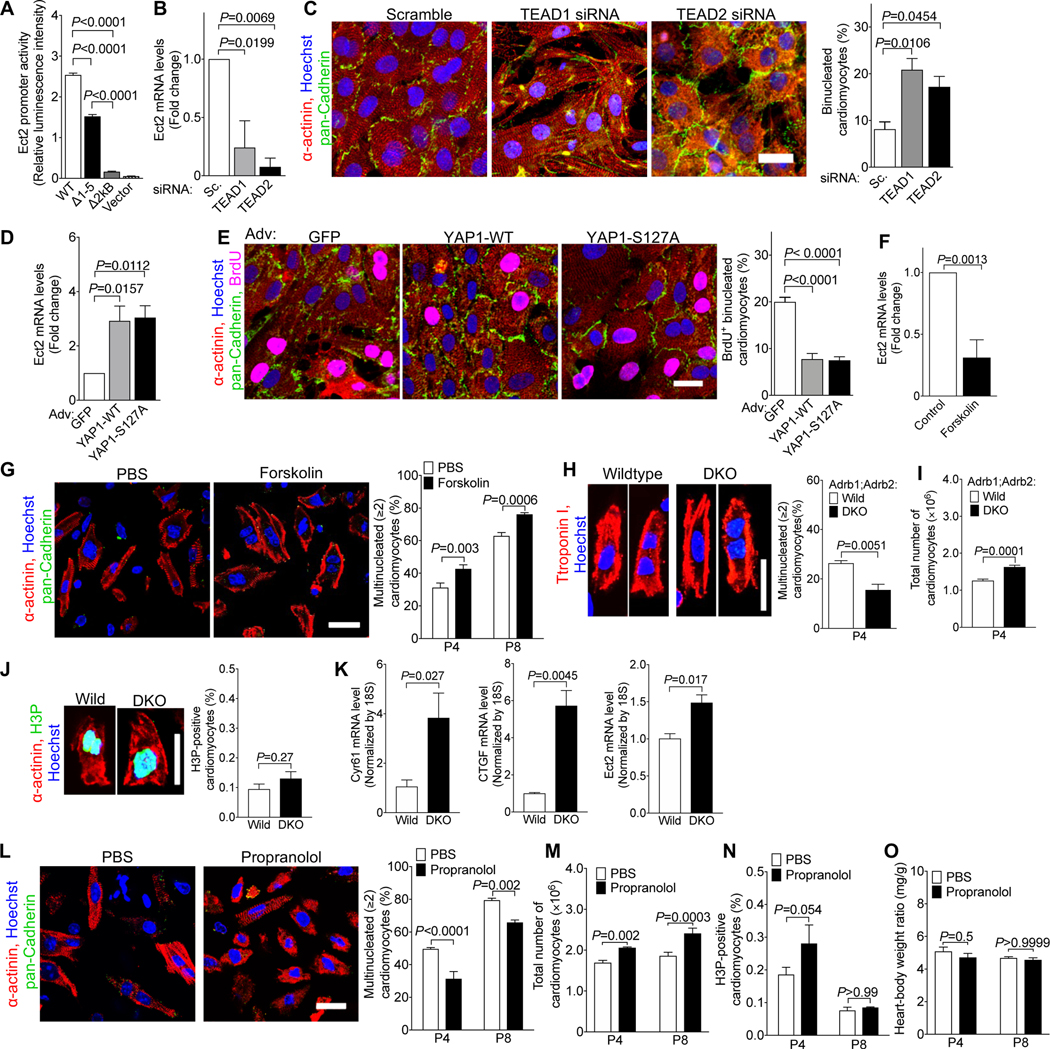

We next sought to identify the mechanisms responsible for decreasing transcription of the Ect2 gene. Previous publications suggested that the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation 48–50. YAP1, the central transcriptional co-regulator controlled by the Hippo pathway, forms a protein complex with TEAD transcription factors 49. We identified five binding sites for the transcription factors TEAD 1 and 2 in the Ect2 promoter (Fig. S7). Removing these TEAD-binding sites individually or en bloc decreased Ect2 promoter activity in Luciferase assays (Fig. 3A). siRNA knockdown of TEAD1/2 reduced Ect2 mRNA levels and increased the proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3B–C). Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of wild type YAP1 (YAP1-WT) and a non-degradable version (YAP1-S127A) in NRVMs increased Ect2 mRNA levels and reduced the proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3D–E). These results show that YAP1 and TEAD1/2 regulate the expression of Ect2 and cardiomyocyte abscission.

Figure 3. β-adrenergic receptor signaling regulates cardiomyocyte abscission and endowment in mice.

(A) Removal of the five TEAD1/2-binding sites (Fig. S7) reduced the activity of the Ect2 promoter in luciferase assays in HEK293 cells. WT: wild type Ect2 promoter; Δ1–5: All five putative TEAD-binding sites were removed; Δ2kB: the continuous 2kB DNA sequence containing all five TEAD-binding sites was removed; Vector: Empty vector that did not contain Ect2 promoter (n = 4 cultures). (B, C) Knockdown of TEAD1 and TEAD2 by siRNA reduced Ect2 mRNA (B), and increased the proportion of binucleated NRVMs (P2, C, n = 3 cardiomyocyte isolations). (D-E) Adenoviral overexpression of wild type YAP1 (YAP1-WT) and a mutated version containing a S127A mutation (YAP1-S127A) in NRVMs (P2) increased the level of Ect2 mRNA (D) and reduced the percentage of binucleated cardiomyocytes (E, n = 4 cardiomyocyte isolations). (F) Forskolin reduced the mRNA level of Ect2 in cultured NRVMs (n = 5 cardiomyocyte isolations). (G) Forskolin administration (1 μg/g, 1 i.p. injection per day) increased the proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes in vivo (n = 6 hearts/group). (H-K) Inactivation of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor genes (DKO) decreased formation of multinucleated cardiomyocytes in vivo (H, n = 4 hearts/group), increased the total number of cardiomyocytes (I, n = 7 hearts for wild, n = 5 hearts for DKO), did not change M-phase (J, n = 4 hearts/group), and increased the expression of the YAP target genes Cyr61 and CTGF (K, n = 3 hearts/group). (L-O) Propranolol administration (10 μg/g, 2 i.p. injections per day) reduced the proportion of multinucleated cardiomyocytes (L, n = 6 hearts/group), and increased the number of cardiomyocytes (M, n = 6 heart/group for P4, n = 4 hearts/group for P8), but did not alter M-phase activity (N, n = 4 hearts/group) or heart-body-weight ratio (O, P4: n = 7 hearts for PBS, n = 6 hearts for Prop; P8: n = 4 hearts/group). Scale bar: 20 μm (C, E, G, H, J, L). Statistical significance was tested with one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons (A-E), Student’s t- test (F, H-K), and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (G, L-O).

The Hippo pathway is activated by G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) via the stimulatory G protein, Gs 28. Accordingly, we treated cultured NRVMs with forskolin, a mimic of active Gs 51, which decreased Ect2 mRNA levels (Fig. 3F). We administered forskolin in newborn mice and found a 37% increase in the proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes after 4 days and a 21% increase after 8 days (Fig. 3G). Because β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors (β1-, β2-AR) are the major Gs-activating GPCR in cardiomyocytes, we examined β1-AR−/−; β2-AR−/− (double-knockout, DKO, 52, 53 pups. These mice showed a lower proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3H) and a higher endowment at P4 (Fig. 3I). Their cardiomyocyte M-phase activity was not changed (Fig. 3J). β1-AR−/−; β2-AR−/− DKO hearts showed increased transcription of the Hippo target genes Cyr61 and CTGF, as well as Ect2 (Fig. 3K). We then administered propranolol, a blocker of β1- and β2-AR, in newborn mice. Propranolol decreased the proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes by 21% after treatment from P1 to P4, and by 17% after treatment from P1 to P8 (Fig. 3L). This was associated with a 22% and 30% increase of cardiomyocyte endowment at P4 and P8, respectively (Fig. 3M), without a change of cardiomyocyte M-phase (Fig. 3N) or heart weight (Fig. 3O). These results show that reducing β-adrenergic receptor signaling enables abscission, thus increasing the endowment.

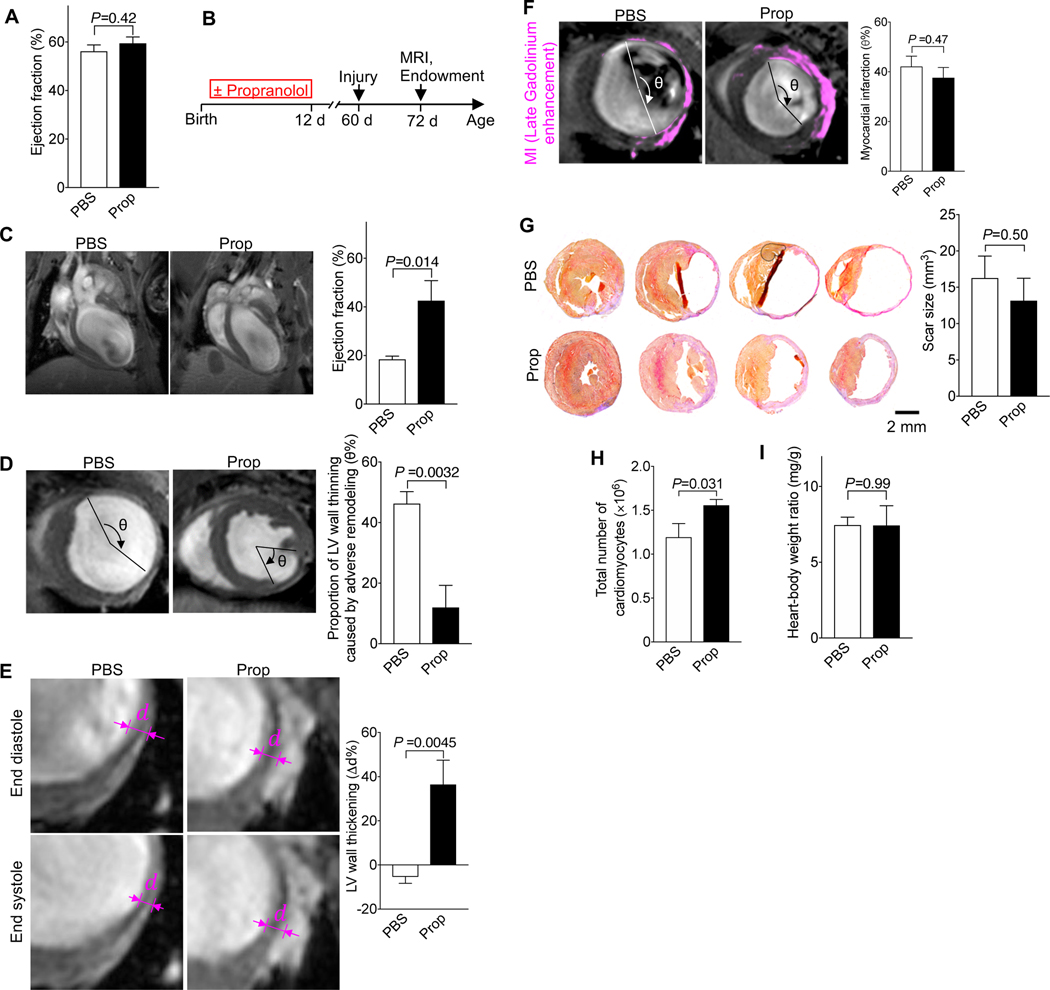

Increasing cardiomyocyte endowment by administration of propranolol in neonatal mice improved heart function and reduced adverse remodeling due to myocardial infarction in adulthood

Although the propranolol-increased cardiomyocyte endowment did not alter cardiac function (Fig. 4A), a larger endowment should confer a benefit after large-scale cardiomyocyte loss, for example, after myocardial infarction (MI). We tested this by administering propranolol in the first week after birth and then inducing myocardial infarction in adult mice (Fig. 4B). We determined cardiac structure and function with MRI and histology (Fig. 4B). Twelve days after MI, mice with propranolol-induced endowment growth had an ejection fraction of 42%, compared with 18% in control mice (Fig. 4C). The thinned region of the LV myocardium after myocardial infarction was significantly smaller (Fig. 4D), and the relative systolic thickening was higher (Fig. 4E), indicating less adverse remodeling. Importantly, the region of myocardium affected by ischemia, visualized by late Gadolinium enhancement (Fig. 4F), and the scar size, determined by histology (Fig. 4G), were not different. Propranolol-treated hearts had a 30% higher cardiomyocyte endowment after MI (determined by stereology, Fig. 4H), in keeping with the increased endowment before MI. The heart weight was not changed (Fig. 4I), indicating that the higher endowment reduced the maladaptive hypertrophy, which drives adverse remodeling after MI. Taken together, these results demonstrate that rescuing cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure with propranolol at the end of development reduces adverse ventricular remodeling in adult mice.

Figure 4. Mice with a 30%-increased cardiomyocyte endowment have better cardiac function and reduced adverse remodeling after myocardial infarction (MI).

Mice received propranolol (Prop, 10 μg/g, 2 i.p. injections per day, P1–12). (A) The ejection fraction (EF) at P60 was not changed (n = 11 hearts for PBS, n = 6 hearts for Prop). (B) Diagram of experimental design. MI was induced at P60 and MRI and histology were performed 12 days after MI. (C) After MI, EF was higher in propranolol-primed mice. (D-G) The region of stretched-out myocardial wall is significantly smaller (D) and systolic myocardial thickening is greater (E), despite same scar size measured in vivo (F) and ex vivo (G, n = 5 hearts for PBS, n = 4 hearts for Prop). (H, I) Propranolol-primed hearts show a higher number of cardiomyocytes, determined by stereology (n = 5 hearts/group), after MI without change of heart weight (n = 5 hearts for PBS, n = 6 hearts for Prop) (I). Statistical significance was tested with t-test.

β-blockers rescue cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes from infants with ToF/PS

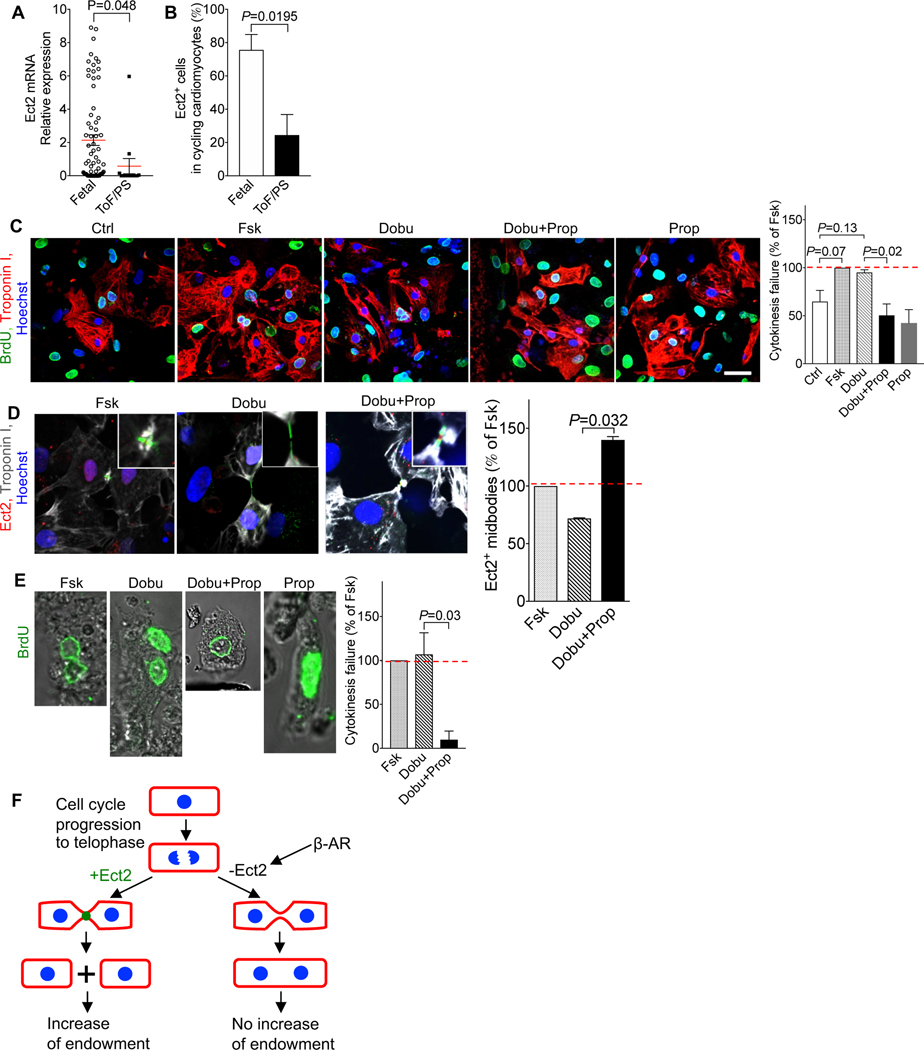

We determined if the molecular mechanisms of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure we discovered are responsible for the increased proportion of binucleated cardiomyocytes in ToF/PS. To this end, we transcriptionally profiled single cardiomyocytes from infants with ToF/PS. ToF/PS cardiomyocytes showed lower Ect2 mRNA levels compared with dividing human fetal cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5A). The frequency of Ect2-expressing cycling cardiomyocytes in ToF/PS infants (24.4%) was significantly lower than in human fetal cardiomyocytes (75.6%, Fig. 5B). Thus, cardiomyocytes in ToF/PS infants exhibit decreased Ect2 levels, similar to cardiomyocytes in neonatal mice (see Fig. 2B). This prompted us to examine the regulation by β-receptors. We used cultured human fetal cardiomyocytes and added forskolin to maximally increase cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure (Fig. 5C). We then treated with dobutamine to mimic the in vivo microenvironment of increased β-AR stimulation, which increased binucleated cardiomyocytes to 95.2% of the forskolin-induced increase (Fig. 5C). Addition of propranolol blocked the dobutamine-stimulated increase of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure completely (Fig. 5C). We examined cardiomyocytes in cytokinesis by immunofluorescence microscopy, which showed that Ect2-positive midbodies were increased with propranolol (Fig. 5D). We then generated organotypic cultures of heart pieces from infants with ToF/PS and added BrdU to label cycling cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5E). Forskolin and dobutamine induced a maximal increase of binucleated cardiomyocytes, and propranolol inhibited the dobutamine-stimulated increase completely (Fig. 5E). In conclusion, β-receptors regulate cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes from infants with ToF/PS and propranolol decreases this effect.

Figure 5. β-adrenergic signaling regulates cytokinesis in cardiomyocytes from ToF/PS patients.

(A) Cardiomyocytes from ToF/PS patients exhibit decreased levels of Ect2 mRNA. Each symbol represents one cycling cardiomyocyte. (B) The percentage of Ect2-positive cycling cardiomyocytes was reduced in ToF/PS patients, compared with fetal human hearts. (A-B, Fetal: n = 71 cardiomyocytes from 4 hearts, ToF/PS: n = 13 cardiomyocytes from 3 hearts). (C, D) β-AR signaling regulates cytokinesis failure in cultured human fetal cardiomyocytes (n = isolations from 3 hearts; Ctrl: control; Fsk: Forskolin, Prop: Propranolol; Dobu: Dobutamine: 10 μM), measured by reduced formation of binucleated daughter cells (C) and higher prevalence of Ect2-positive midbodies (D). (E) Propranolol increases completion of cytokinesis in cultured ToF/PS cardiomyocytes (n = cultures from 3 patients). (F) Cellular model connecting cytokinesis failure to endowment changes. (G) Molecular model of cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes. Scale bar: 40 μm (C). Statistical significance was tested with T-test (A) and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (C-E).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that ToF/PS infants develop increased cardiomyocyte terminal differentiation, measured by increased formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes. This happens in the first 6 months after birth, which shows that these changes do not result from surgical or medical interventions. The changes persisted in older ToF/PS patients. The increased binucleation indicates a proportionate failure of cytokinesis, reducing cardiomyocyte proliferation by 25%. By identifying the upstream molecular regulators, we show that β-blockers could turn cytokinesis failure to increased division.

The results in mice demonstrate that promoting the progression of cytokinesis to abscission in the post-natal period increases the endowment, which improves remodeling due to myocardial infarction. This raises the possibility that a decreased or increased cardiomyocyte endowment connects to outcomes in human patients. This could be tested with β-blocker administration in human infants with CHD to increase the endowment, followed by measuring clinical outcomes, such as myocardial function and risk of heart failure development. β-blockers have been used acutely to treat and prevent cyanotic spells in ToF/PS54. Although this demonstrates that β-blockers are safe in this population, an effect on myocardial growth mechanisms was not evaluated. Our results also predict that administration of β-blockers should produce the largest effect on cardiomyocyte cytokinesis in the first 6 months after birth, which is in line with our previously demonstrated effectiveness of stimulating cardiomyocyte cell cycling in CHD cardiomyocytes in the same period55. The duration of this period should also be assessed in types of CHD other than ToF/PS.

Elucidating the mechanisms generating binucleated cardiomyocytes allows us to compare this process in other cell types. Formation of binucleated cells is also an early event in cancer formation, leading, via entrapment of lagging chromosomes in the cleavage furrow, to aneuploidy 56. In this process, chromosome entrapment lowers Rho A activity in the cleavage furrow, leading to relaxation of the contractile ring and cytokinesis failure. However, we have no evidence for chromatin entrapment cardiomyocyte cytokinesis failure. In cancer cells, cytokinesis failure activates the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway57; however, we found that Hippo pathway activation triggers cytokinesis failure in cardiomyocytes. Cytokinesis failure is also a step in platelet formation, also induced by repression of Ect2 58. This suggests a generalizable molecular mechanism of Ect2 repression in cytokinesis failure in somatic cells.

Cardiomyocyte cell cycle withdrawal in mice happens in the first 3 weeks59 and formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes in the first 2 weeks after birth18, 19. This is nearly coincident, which suggests that they could be mechanistically connected. However, we show that by increasing or decreasing cardiomyocyte binucleation, cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry does not change, thus demonstrating that formation of binucleated cardiomyocytes and cell cycle withdrawal are distinct molecular processes. This is supported by the increase of multinucleated cardiomyocytes (>2 nuclei) in ToF/PS, which shows that in ToF/PS, binucleated cardiomyocytes re-enter the cell cycle. This is consistent with the literature demonstrating that pig cardiomyocytes have up to 16 nuclei60, which shows that binucleated cardiomyocytes can re-enter the cell cycle multiple times.

Our results place the Hippo pathway downstream of β-AR signaling and upstream of Ect2 gene regulation. This does not involve regulation of cell cycle entry and, as such, is distinct from direct genetic modulation of the central Hippo kinases and scaffolds, or regulation of the dystroglycan/agrin complex27, which all have a significant effect on cell cycle entry. Because of the large number of different G protein coupled receptors (GPCR), it is possible that other GPCR may have a function in regulating cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry, progression, and division.

Low levels of cardiomyocyte proliferation in mammals continue to be a barrier for heart regeneration 27. To overcome this, molecular interventions to stimulate cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry in adults have been proposed: increase of individual positive cell cycle regulators (cyclins A2 and D2, 61, 62 and combinations 63), removal of negative cell cycle regulators (p53, pocket proteins, 64, 65), and administration of mitogenic growth factors (FGF, NRG1, Oncostatin M, FSTL1, 55, 66–68). All of these approaches involve oncogenes or tumor suppressors and are associated with the risk of inducing uncontrolled proliferation. The findings presented here indicate that targeting the final stage of the cell cycle, i.e., abscission, is a viable strategy that could synergize with any of these interventions to increase cardiomyocyte generation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tae Kyung Kim (University of Pennsylvania) for help with initial single cell amplifications. We thank Channing Der (University of North Carolina Chapel Hill) for providing Ect2flox mice and Mark Petroncski (Clare Hall Laboratories, London), Buzz Baum (University College London), and Toru Miki (Nagaoka University of Technology) for providing Ect2 expression constructs. We thank Maria Magaro (Harvard Medical School) for technical assistance with phenotyping of cardiomyocytes. We thank the patients and families for participating in this research and the operating room staff and cardiac surgeons for assistance with identifying study subjects and ascertaining samples. We thank Sean Lal and Cris dos Remedios (University of Sydney) and Charles McThiernan (University of Pittsburgh) for providing human myocardial samples. This project used the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and Tissue and Research Pathology/Pitt Biospecimen Core shared resource which is supported in part by award P30CA047904. We thank members of the Kuhn laboratory for support, helpful discussions, and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Richard King Mellon Foundation Institute for Pediatric Research (UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), by a Transatlantic Network of Excellence grant by Fondation Leducq (15CVD03), Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation, and NIH grant R01HL106302 (to B.K.) and Health Research Formula Funds from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania which had no role in study design or interpretation of data (to J.H.E.). This project was supported in part by UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh (to H.L.), Genomics Discovery Award (to B.K. and D.K.), and UPP Physicians (to B.K.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns KM, Byrne BJ, Gelb BD, Kuhn B, Leinwand LA, Mital S, Pearson GD, Rodefeld M, Rossano JW, Stauffer BL, Taylor MD, Towbin JA and Redington AN. New mechanistic and therapeutic targets for pediatric heart failure: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group. Circulation. 2014;130:79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollova M, Bersell K, Walsh S, Savla J, Das LT, Park SY, Silberstein LE, Dos Remedios CG, Graham D, Colan S and Kuhn B. Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:1446–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, Szewczykowska M, Jackowska T, Dos Remedios C, Malm T, Andra M, Jashari R, Nyengaard JR, Possnert G, Jovinge S, Druid H and Frisen J. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell. 2015;161:1566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahed AC, Gelb BD, Seidman JG and Seidman CE. Genetics of congenital heart disease: the glass half empty. Circ Res. 2013;112:707–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy JG, Gersh BJ, Mair DD, Fuster V, McGoon MD, Ilstrup DM, McGoon DC, Kirklin JW and Danielson GK. Long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nollert G, Fischlein T, Bouterwek S, Bohmer C, Klinner W and Reichart B. Long-term survival in patients with repair of tetralogy of Fallot: 36-year follow-up of 490 survivors of the first year after surgical repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nollert G, Fischlein T, Bouterwek S, Bohmer C, Dewald O, Kreuzer E, Welz A, Netz H, Klinner W and Reichart B. Long-term results of total repair of tetralogy of Fallot in adulthood: 35 years follow-up in 104 patients corrected at the age of 18 or older. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;45:178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatzoulis MA, Balaji S, Webber SA, Siu SC, Hokanson JS, Poile C, Rosenthal M, Nakazawa M, Moller JH, Gillette PC, Webb GD and Redington AN. Risk factors for arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death late after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: a multicentre study. Lancet. 2000;356:975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacha EA, Scheule AM, Zurakowski D, Erickson LC, Hung J, Lang P, Mayer JE Jr., del Nido PJ and Jonas RA. Long-term results after early primary repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therrien J, Marx GR and Gatzoulis MA. Late problems in tetralogy of Fallot--recognition, management, and prevention. Cardiol Clin. 2002;20:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Andrea A, Caso P, Sarubbi B, Russo MG, Ascione L, Scherillo M, Cobrufo M and Calabro R. Right ventricular myocardial dysfunction in adult patients late after repair of tetralogy of fallot. Int J Cardiol. 2004;94:213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geva T, Sandweiss BM, Gauvreau K, Lock JE and Powell AJ. Factors associated with impaired clinical status in long-term survivors of tetralogy of Fallot repair evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1068–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones M, Ferrans VJ, Morrow AG and Roberts WC. Ultrastructure of crista supraventricularis muscle in patients with congenital heart diseases associated with right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 1975;51:39–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones M and Ferrans VJ. Myocardial degeneration in congenital heart disease. Comparison of morphologic findings in young and old patients with congenital heart disease associated with muscular obstruction to right ventricular outflow. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:1051–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S and Frisen J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B and Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F, Wang X, Capasso JM and Gerdes AM. Rapid transition of cardiac myocytes from hyperplasia to hypertrophy during postnatal development. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:1737–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soonpaa MH, Kim KK, Pajak L, Franklin M and Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and binucleation during murine development. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkass K, Panula J, Westman M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL and Bergmann O. No Evidence for Cardiomyocyte Number Expansion in Preadolescent Mice. Cell. 2015;163:1026–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wills AA, Holdway JE, Major RJ and Poss KD. Regulated addition of new myocardial and epicardial cells fosters homeostatic cardiac growth and maintenance in adult zebrafish. Development. 2008;135:183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson M, Barske L, Van Handel B, Rau CD, Gan P, Sharma A, Parikh S, Denholtz M, Huang Y, Yamaguchi Y, Shen H, Allayee H, Crump JG, Force TI, Lien CL, Makita T, Lusis AJ, Kumar SR and Sucov HM. Frequency of mononuclear diploid cardiomyocytes underlies natural variation in heart regeneration. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1346–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Rosa JM, Sharpe M, Field D, Soonpaa MH, Field LJ, Burns CE and Burns CG. Myocardial Polyploidization Creates a Barrier to Heart Regeneration in Zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2018;44:433–446 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hesse M, Doengi M, Becker A, Kimura K, Voeltz N, Stein V and Fleischmann BK. Midbody Positioning and Distance Between Daughter Nuclei Enable Unequivocal Identification of Cardiomyocyte Cell Division in Mice. Circ Res. 2018;123:1039–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel FB, Schebesta M and Keating MT. Anillin localization defect in cardiomyocyte binucleation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:601–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leone M, Musa G and Engel FB. Cardiomyocyte binucleation is associated with aberrant mitotic microtubule distribution, mislocalization of RhoA and IQGAP3, as well as defective actomyosin ring anchorage and cleavage furrow ingression. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:1115–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fededa JP and Gerlich DW. Molecular control of animal cell cytokinesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzahor E and Poss KD. Cardiac regeneration strategies: Staying young at heart. Science. 2017;356:1035–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng K, Li H, Fu XD, Mills GB and Guan KL. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S and Eschenhagen T. What is the role of beta-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circ Res. 2003;93:896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross RD, Daniels SR, Schwartz DC, Hannon DW, Shukla R and Kaplan S. Plasma norepinephrine levels in infants and children with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59:911–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto SD, Stauffer BL, Polk J, Medway A, Friedrich M, Haubold K, Peterson V, Nunley K, Nelson P, Sobus R, Stenmark KR and Sucharov CC. Gene expression and beta-adrenergic signaling are altered in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:785–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyamoto SD, Stauffer BL, Nakano S, Sobus R, Nunley K, Nelson P and Sucharov CC. Beta-adrenergic adaptation in paediatric idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina E, Sucharov CC, Nelson P, Miyamoto SD and Stauffer BL. Molecular Changes in Children with Heart Failure Undergoing Left Ventricular Assist Device Therapy. J Pediatr. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakano SJ, Sucharov J, van Dusen R, Cecil M, Nunley K, Wickers S, Karimpur-Fard A, Stauffer BL, Miyamoto SD and Sucharov CC. Cardiac Adenylyl Cyclase and Phosphodiesterase Expression Profiles Vary by Age, Disease, and Chronic Phosphodiesterase Inhibitor Treatment. J Card Fail. 2017;23:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahmoud AI, O’Meara CC, Gemberling M, Zhao L, Bryant DM, Zheng R, Gannon JB, Cai L, Choi WY, Egnaczyk GF, Burns CE, Burns CG, MacRae CA, Poss KD and Lee RT. Nerves Regulate Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Heart Regeneration. Dev Cell. 2015;34:387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White IA, Gordon J, Balkan W and Hare JM. Sympathetic Reinnervation Is Required for Mammalian Cardiac Regeneration. Circ Res. 2015;117:990–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feridooni T, Hotchkiss A, Baguma-Nibasheka M, Zhang F, Allen B, Chinni S and Pasumarthi KBS. Effects of beta-adrenergic receptor drugs on embryonic ventricular cell proliferation and differentiation and their impact on donor cell transplantation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H919–H931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreipke RE and Birren SJ. Innervating sympathetic neurons regulate heart size and the timing of cardiomyocyte cell cycle withdrawal. J Physiol. 2015;593:5057–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng YT, Kopel R, Stabila JP, McGonnigal BG, Nguyen TT, Gruppuso PA and Padbury JF. Beta-adrenergic receptors (betaAR) regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation during early postnatal life. FASEB J. 2001;15:1921–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakaue-Sawano A, Kurokawa H, Morimura T, Hanyu A, Hama H, Osawa H, Kashiwagi S, Fukami K, Miyata T, Miyoshi H, Imamura T, Ogawa M, Masai H and Miyawaki A. Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell. 2008;132:487–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eberwine J and Crino P. Analysis of mRNA populations from single live and fixed cells of the central nervous system. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2001;Chapter 5:Unit 5 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris J, Singh JM and Eberwine JH. Transcriptome analysis of single cells. J Vis Exp. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dueck H, Khaladkar M, Kim TK, Spaethling JM, Francis C, Suresh S, Fisher SA, Seale P, Beck SG, Bartfai T, Kuhn B, Eberwine J and Kim J. Deep sequencing reveals cell-type-specific patterns of single-cell transcriptome variation. Genome Biol. 2015;16:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su KC, Takaki T and Petronczki M. Targeting of the RhoGEF Ect2 to the equatorial membrane controls cleavage furrow formation during cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA and Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook DR, Solski PA, Bultman SJ, Kauselmann G, Schoor M, Kuehn R, Friedman LS, Cowley DO, Van Dyke T, Yeh JJ, Johnson L and Der CJ. The ect2 rho Guanine nucleotide exchange factor is essential for early mouse development and normal cell cytokinesis and migration. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:932–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, Penninger JM and Molkentin JD. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL and Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Gise A, Lin Z, Schlegelmilch K, Honor LB, Pan GM, Buck JN, Ma Q, Ishiwata T, Zhou B, Camargo FD and Pu WT. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bassat E, Mutlak YE, Genzelinakh A, Shadrin IY, Baruch Umansky K, Yifa O, Kain D, Rajchman D, Leach J, Riabov Bassat D, Udi Y, Sarig R, Sagi I, Martin JF, Bursac N, Cohen S and Tzahor E. The extracellular matrix protein agrin promotes heart regeneration in mice. Nature. 2017;547:179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dessauer CW, Watts VJ, Ostrom RS, Conti M, Dove S and Seifert R. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CI. Structures and Small Molecule Modulators of Mammalian Adenylyl Cyclases. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69:93–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rohrer DK, Desai KH, Jasper JR, Stevens ME, Regula DP, Jr., Barsh GS, Bernstein D and Kobilka BK. Targeted disruption of the mouse beta1-adrenergic receptor gene: developmental and cardiovascular effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7375–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chruscinski AJ, Rohrer DK, Schauble E, Desai KH, Bernstein D and Kobilka BK. Targeted disruption of the beta2 adrenergic receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barazzone C, Jaccard C, Berner M, Dayer P, Rouge JC, Oberhansli I and Friedli B. Propranolol treatment in children with tetralogy of Fallot alters the response to isoprenaline after surgical repair. Br Heart J. 1988;60:156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polizzotti BD, Ganapathy B, Walsh S, Choudhury S, Ammanamanchi N, Bennett DG, Dos Remedios CG, Haubner BJ, Penninger JM and Kuhn B. Neuregulin stimulation of cardiomyocyte regeneration in mice and human myocardium reveals a therapeutic window. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:281ra45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ganem NJ, Storchova Z and Pellman D. Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ganem NJ, Cornils H, Chiu SY, O’Rourke KP, Arnaud J, Yimlamai D, Thery M, Camargo FD and Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure triggers hippo tumor suppressor pathway activation. Cell. 2014;158:833–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao Y, Smith E, Ker E, Campbell P, Cheng EC, Zou S, Lin S, Wang L, Halene S and Krause DS. Role of RhoA-specific guanine exchange factors in regulation of endomitosis in megakaryocytes. Dev Cell. 2012;22:573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh S, Ponten A, Fleischmann BK and Jovinge S. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle control and growth estimation in vivo--an analysis based on cardiomyocyte nuclei. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grabner W and Pfitzer P. Number of nuclei in isolated myocardial cells of pigs. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1974;15:279–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shapiro SD, Ranjan AK, Kawase Y, Cheng RK, Kara RJ, Bhattacharya R, Guzman-Martinez G, Sanz J, Garcia MJ and Chaudhry HW. Cyclin A2 induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction through cytokinesis of adult cardiomyocytes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Soonpaa MH and Field LJ. Targeted expression of cyclin D2 results in cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and infarct regression in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2005;96:110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohamed TMA, Ang YS, Radzinsky E, Zhou P, Huang Y, Elfenbein A, Foley A, Magnitsky S and Srivastava D. Regulation of Cell Cycle to Stimulate Adult Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Regeneration. Cell. 2018;173:104–116 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Tsai SC and Field LJ. Expression of mutant p193 and p53 permits cardiomyocyte cell cycle reentry after myocardial infarction in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2004;94:1606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacLellan WR, Garcia A, Oh H, Frenkel P, Jordan MC, Roos KP and Schneider MD. Overlapping roles of pocket proteins in the myocardium are unmasked by germ line deletion of p130 plus heart-specific deletion of Rb. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2486–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei K, Serpooshan V, Hurtado C, Diez-Cunado M, Zhao M, Maruyama S, Zhu W, Fajardo G, Noseda M, Nakamura K, Tian X, Liu Q, Wang A, Matsuura Y, Bushway P, Cai W, Savchenko A, Mahmoudi M, Schneider MD, van den Hoff MJ, Butte MJ, Yang PC, Walsh K, Zhou B, Bernstein D, Mercola M and Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial FSTL1 reconstitution regenerates the adult mammalian heart. Nature. 2015;525:479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kubin T, Poling J, Kostin S, Gajawada P, Hein S, Rees W, Wietelmann A, Tanaka M, Lorchner H, Schimanski S, Szibor M, Warnecke H and Braun T. Oncostatin M is a major mediator of cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and remodeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:420–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Engel FB, Hsieh PC, Lee RT and Keating MT. FGF1/p38 MAP kinase inhibitor therapy induces cardiomyocyte mitosis, reduces scarring, and rescues function after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.