Abstract

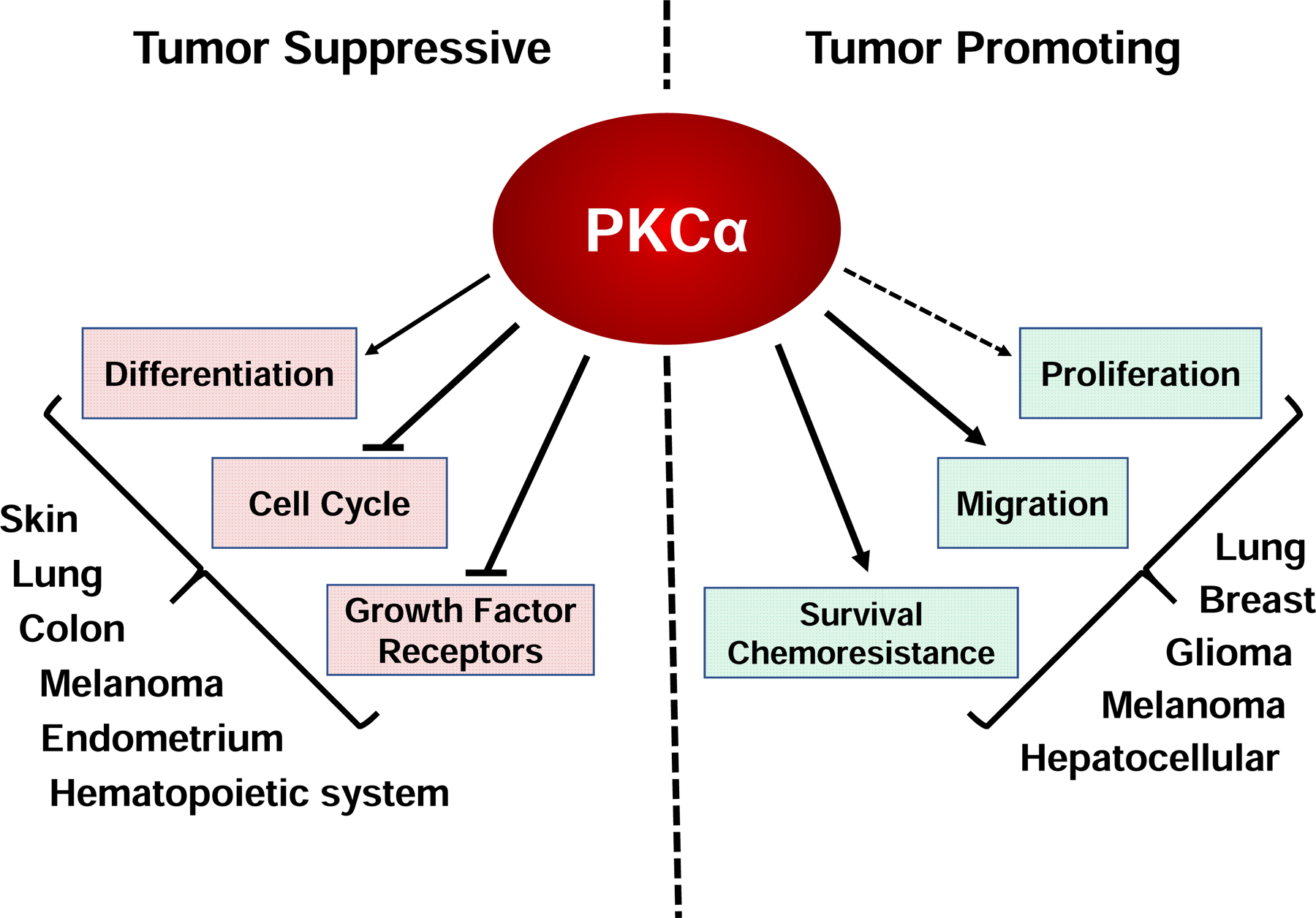

Protein kinase C α (PKCα) is a ubiquitously expressed member of the PKC family of serine/threonine kinases with diverse functions in normal and neoplastic cells. Early studies identified anti-proliferative and differentiation-inducing functions for PKCα in some normal tissues (e.g., regenerating epithelia) and pro-proliferative effects in others (e.g., cells of the hematopoietic system, smooth muscle cells). Additional well documented roles of PKCα signaling in normal cells include regulation of the cytoskeleton, cell adhesion, and cell migration, and PKCα can function as a survival factor in many contexts. While a majority of tumors lose expression of PKCα, others display aberrant overexpression of the enzyme. Although cancer-related mutations of PKCα are uncommon, rare examples of driver mutations have been detected in certain cancer types (e. g., chordoid gliomas). Here we review the role PKCα in various cancers, describe mechanisms by which PKCα affects cancer-related cell functions, and discuss how the diverse functions of PKCα contribute to tumor suppressive and tumor promoting activities of the enzyme. We end the discussion by addressing mutations and expression of PKCα in tumors and the clinical relevance of these findings.

Keywords: Protein kinase C (PKC), tumor suppression, tumor promotion, migration, metastasis, survival, chemoresistance

1. Introduction

Protein kinase C α (PKCα), which is encoded by the PRKCA gene, is a founding member (Parker et al., 1986) of a family of 11 serine/threonine kinases collectively termed protein kinase C (PKC). PKC was initially isolated as a protease-activated kinase from rat brain (Inoue et al., 1977; Takai et al., 1977). However, with cloning of the enzyme (Coussens et al., 1986; Parker et al., 1986), it became apparent that PKC is a family of isozymes that show strong homology in their C-terminal kinase domains, but differ in their regulatory domain and in their cofactor requirements (Newton, 2001, 2018). Along with PKCβI, PKCβII, and PKCγ, PKCα is a member of the conventional or classical subfamily (cPKCs), which are dependent on phosphatidylserine, calcium and diacylglycerol for activity. The other PKC subfamilies are the novel PKCs, PKCδ, PKCε, PKCη and PKCθ, which are calcium-independent, and the atypical PKCs, PKCι\λ and PKCζ, which require neither calcium nor DAG for activity.

Physiological activation of PKCα and the other classical and novel PKCs involves generation of diacylglycerol (DAG), primarily by phospholipase C-mediated cleavage of membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) downstream of tyrosine kinase and G protein-coupled receptors (Becker and Hannun, 2005; Newton, 2018). Hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 also generates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) which leads to increased cytosolic Ca2+, an essential cofactor for the conventional PKCs (Newton, 2018). Under resting conditions, PKCα is maintained in an inactive conformation in the cytosol. DAG recruits PKCα to the membrane, and membrane association activates the enzyme by inducing a conformational change that releases an autoinhibitory N-terminal pseudosubstrate domain from the active site. PKCα signaling is terminated by depletion of membrane DAG by the actions of diacylglycerol kinases and lipases. DAG metabolism results in release of the enzyme from the membrane into the cytosol and restoration of the inactive conformation. Thus, membrane association is the activating event for PKCα and its activity in cells can be monitored by its translocation from the cytosol to the membrane. Several pharmacological agonists can interact with the DAG binding site and activate classical and novel PKCs, including tumor promoting phorbol esters, such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, also known as 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)) and bryostatins (Newton, 2018).

In addition to membrane binding, activation of PKCα is dependent on phosphorylation at three sites located in the activation loop (Thr497), turn motif (Thr638), and hydrophobic motif (Ser657) of the enzyme (Keranen et al., 1995; Newton, 2018). Phosphorylation both stabilizes the protein and primes it for activation. However, unlike other kinases such as AKT and ERK, phosphorylation at these sites is part of the initial processing of the enzyme and is not indicative of activation per se. Despite excellent reviews by the Newton group (Newton, 2001, 2018), there is considerable confusion regarding the role of these phosphorylations, and multiple reports equate priming site phosphorylation with activation of PKCα. Part of this confusion likely arises from 32PO4 incorporation studies indicating that PKCα is phosphorylated upon activation (Lee et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1989; Ng et al., 1999b); however, this phosphorylation occurs on Thr250 and Ser260 (Ng et al., 1999b) and not at priming sites. Thus, priming site phosphorylation cannot be used as a marker of PKCα activation, with translocation of the primed protein to the membrane and substrate phosphorylation providing the best indication of its activation.

Signal termination of PKCα can occur through diacylglycerol metabolism or through agonist-induced downregulation, a key aspect of PKC biology. Early studies, mainly using overexpressed protein and PMA or bryostatin, led to a model where prolonged activation results in caveolar internalization, priming site dephosphorylation, and subsequent proteasomal degradation of PKCα (Hansra et al., 1999; Lee et al., 1996; Prevostel et al., 2000). However, studies in multiple cell types by our group and others have identified at least two distinct pathways of endogenous PKCα downregulation, with the prevailing earlier model likely reflecting a combination of these mechanisms (Leontieva and Black, 2004; Lum et al., 2013a; Lum et al., 2013b; Prevostel et al., 2000). PMA can fully activate endogenous PKCα without leading to dephosphorylation of the enzyme (Lee et al., 1996; Leontieva and Black, 2004; Lum et al., 2013a); rather, prolonged PMA treatment elicits proteasomal degradation of the fully phosphorylated active enzyme at the plasma membrane (Lum et al., 2013a; Lum et al., 2013b). This is also the predominant mechanism of downregulation elicited by bryostatin. However, bryostatin also triggers clathrin-independent internalization of endogenous PKCα to a perinuclear compartment where the fully primed enzyme undergoes delayed lysosomal degradation (Leontieva and Black, 2004; Lum et al., 2013b), a mechanism that is consistent with extensive evidence for a role of PKCα in regulation of membrane trafficking in cells (Alvi et al., 2007). A small proportion of the internalized enzyme undergoes complete desphosphorylation and rapid proteasomal degradation in the perinuclear region (Leontieva and Black, 2004; Lum et al., 2013b). While PMA induces downregulation of endogenous PKCα only at the plasma membrane, it can also channel exogenously overexpressed protein to the perinuclear/lysosomal degradation pathway (Lum et al., 2013b), providing an explanation for the PMA-induced dephosphorylation of PKCα observed in previous studies (Prevostel et al., 2000). Surprisingly, our work also determined that PKCα (but not PKCδ and PKCε) is highly resistant to downregulation following prolonged diacylglycerol-mediated activation (Lum et al., 2016). This sustained activation of PKCα in the presence of its physiological activator is in keeping with the prolonged activation/membrane association of PKCα seen in growth-arrested, differentiated cells in epithelial tissues such as intestine (Frey et al., 1997; Saxon et al., 1994; Verstovsek et al., 1998), skin (Tibudan et al., 2002), and endometrium (Hsu et al., 2018) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of PKCα distribution in normal epithelial tissues.

A. Mouse small intestine. PKCα (brown staining) is diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm of proliferating crypt cells (arrowheads), indicating that it is inactive in these cells. However, the enzyme becomes activated/membrane-associated coincident with growth arrest at the crypt/villus junction, a pattern that is maintained in post-mitotic and differentiating cells of the villus (arrow). B. Murine vaginal squamous epithelium. PKCα is inactive/cytoplasmic in proliferating basal cells, but is activated/membrane-associated in the non-proliferative suprabasal cells. C. Mouse endometrium. Ki67 positive (dark nuclear staining in upper right panel) proliferating cells (arrows) express low levels of cytoplasmic staining for PKCα (upper left panel, arrows), whereas non-proliferative Ki67 negative cells show robust membrane staining for PKCα (arrowheads). The lower panel is a higher magnification image of non-proliferating cells showing membrane association of PKCα.

The realization that PKCs are the major cellular receptors for tumor promoting phorbol esters led to the idea that these enzymes act as oncogenes; however, subsequent studies have revealed that the role of these kinases in cancer is considerably more complex, with individual PKC isozymes having diverse and often opposing effects dependent on context (Black and Black, 2012; Black, 2001). In this review, we outline the role and regulation of PKCα in various cancer types, describe mechanisms by which PKCα affects cancer-related cell functions, and address the clinical relevance of these findings. We have concentrated on studies where the involvement of PKCα has been confirmed through knockdown, genetic deletion, overexpression and/or use of inhibitors. Inevitably, this approach will miss some functions of PKCα where studies have not identified the specific isozyme mediating “effects of PKC”.

2. PKCα signaling in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and tumorigenesis

The involvement of PKCα in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation and tumorigenesis has been investigated in normal cells and tissues and in multiple tumor types. Together, these studies highlight the complexity and context-dependence of the effects of PKCα on these processes, with opposite effects seen in different systems and even within the same tissue and tumor type. While PKCα signaling promotes cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis in some contexts, it can mediate growth arrest, differentiation, and tumor suppression in others. This complexity suggests a function of PKCα as a molecular sensor that can promote or repress cell proliferation and differentiation in response to specific environmental cues. In this vein, it has been suggested that the responses induced by PKCα are not an intrinsic property of the kinase, but instead reflect dynamic interactions of the kinase with cell type-specific factors such as anchoring proteins, modulators, and substrates (Nakashima, 2002). In the following sections, we discuss current understanding of the contribution of PKCα to these processes in different tissue types.

2.1. Roles in normal tissues

As discussed in more detail in the sections below, PKCα signaling has pro-proliferative functions in some normal tissues and growth inhibitory/differentiation-inducing effects in others. We note that in-depth studies of PKCα function in normal tissues are limited, a caveat that should be kept in mind in synthesizing currently available data. The most detailed analysis of growth regulatory roles of PKCα in normal cells comes from studies in the hematopoietic system and in regenerating epithelial tissues, including the intestinal epithelium, the epidermis, and the endometrial epithelium. While PKCα appears to have both pro- and anti-proliferative/differentiation-inducing effects in cells of the immune system (see Section 2.2), the enzyme predominantly regulates anti-proliferative and tumor suppressive signaling in regenerating epithelia (see Section 2.3). Additional support for pro-proliferative effects of the kinase in normal tissues comes from studies in muscle cells, Schwann cells, and osteoblasts. Foegh and colleagues showed that a single dose of antisense oligonucleotide targeting PKCα caused long-lasting (at least 4 days) growth inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells (Leszczynski et al., 1996), a finding that was subsequently confirmed by others (Jiang et al., 2017; Okazaki et al., 2000; Shaikh et al., 2013). Consistent with high expression of PKCα in myometrial cells, the kinase is required for endothelin-1-induced proliferation of these cells (Eude et al., 2002; Tertrin-Clary et al., 1999). PKCα activation enhances the proliferation of Schwann cells following peripheral nerve injury, through an ERK-dependent mechanism (Li et al., 2020), and promotes the proliferation of primary human osteoblasts (Lampasso et al., 2002), while suppressing osteoblastic differentiation (Nakura et al., 2011). There is little information on the involvement of PKCα signaling in regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation in the normal mammary gland, liver, and lung. However, extensive evidence supports a tumor promoting role of the kinase in breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, while results are mixed for lung cancer.

2.2. The hematopoietic system and hematological malignancies

PKCα signaling has been linked to regulation of both cell proliferation and differentiation in normal hematopoietic cells. An early study using transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type PKCα in thymocytes pointed to a pro-proliferative role in these cells (Iwamoto et al., 1992). Although no proliferative effects were observed in vivo, isolated PKCα-overexpressing thymocytes showed markedly enhanced proliferation and IL-2 production in response to a weak anti-CD3 antibody stimulus, in association with membrane association/activation of the overexpressed enzyme. Studies in PKCα knockout mice revealed a marked reduction in T cell proliferative responses, while B cell proliferation was unaffected (Pfeifhofer et al., 2006). PKCα also appears to cooperate with PKCθ to regulate T cell proliferation: while mice lacking either PKCα or PKCθ showed only a mild activation defect in a graft-versus-host model, double PKCα/PKCθ knockout mice had a severe defect in alloreactive T cell proliferation (Gruber et al., 2009). In other studies, PKCα was identified as a major effector of cytokine (stem cell factor and erythropoietin)-induced proliferative signaling in erythroid progenitor cells (Haslauer et al., 1999). In contrast, expression of constitutively active PKCα provided a signal for differentiation of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells into macrophages, mimicking the effects of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Pierce et al., 1998). Furthermore, overexpression of PKCα, but not PKCβII, ε, ζ, or η, induced differentiation of a mouse myeloid progenitor cell line into mature macrophages in response to PMA stimulation (Mischak et al., 1993).

Several groups have addressed the role of PKCα in hematological malignancy. Interestingly, in all cases, the effects of PKCα were associated with growth inhibition and tumor suppression. Using mouse models, the Michie laboratory showed that subversion of PKCα signaling in hematopoietic progenitor cells by stable expression of kinase dead PKCα (PKCα K368R) results in the development of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)-like disease, with PKCα-deficient cells phenotypically resembling human B-CLL cells (Nakagawa et al., 2006). Follow-up studies revealed that PKCα deficiency promotes lineage plasticity in B-committed precursors by perturbing critical B-lineage transcription factors, pointing to downregulation of PKCα expression/activity as a mechanism for lineage transdifferentiation in B-cell malignancy (Nakagawa et al., 2012). Further evidence for a suppressive role of the enzyme was provided by a series of studies by the Fields group. Their work determined that PKCα promotes cytostasis and megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 human erythroleukemia cells (Hocevar et al., 1992; Murray et al., 1993) and that the effect is mediated by isozyme-specific sequences within the catalytic domain (Walker et al., 1995). Studies by the Schwende group (Dieter and Schwende, 2000) demonstrated the ability of PKCα to promote the differentiation of THP-1 monocyte-like cells (derived from a childhood case of acute monocytic leukemia) into macrophage-like cells, with antisense-induced deficiency of the enzyme enhancing the proliferation of these cells. Additional studies indicated that sustained activation of PKCα is required for differentiation of HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells into macrophages (Aihara et al., 1991). Consistent with a tumor suppressive role of PKCα in patients, a recent study identified loss of PKCα as an indicator of relapse and very poor outcome in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) patients (Milani et al., 2014).

2.3. Regenerating epithelial tissues

2.3.1. The role of PKCα signaling in maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and in the development of intestinal/colon cancer

The contribution of PKCα signaling to maintenance of intestinal epithelial homeostasis has been extensively studied by our group and others. Using a combined morphological and biochemical approach, we demonstrated that (a) PKCα is cytosolic/inactive in proliferating cells of intestinal and colonic crypts of mice, rats, and humans, and (b) the enzyme undergoes plasma membrane association, indicative of kinase activation, coincident with cell growth arrest in the mid to upper crypt region (Frey et al., 2000; Frey et al., 1997; Hao et al., 2011; Saxon et al., 1994; Verstovsek et al., 1998), a finding that was confirmed by others (Jiang et al., 1995) (Figure 1A). Follow-up studies revealed that PKCα activation triggers a coordinated program of molecular events leading to intestinal epithelial cell cycle withdrawal into G0 (Frey et al., 2000). PKCα induces the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 and rapidly downregulates D-type cyclins, thereby inhibiting the activity of all major G1/S cyclin/CDK complexes and inducing changes in the pocket proteins, p107, pRb, and p130, that drive cells to exit the cell cycle (Frey et al., 2000). This program requires sustained PKCα activity and prolonged stimulation of the ERK/MAP pathway (Clark et al., 2004). PKCα downregulates cyclin D1 via two mechanisms: blockade of cyclin D1 translation initiation by PP2A-mediated hypophosphorylation/activation of the translational repressor, 4E-BP1, and inhibition of cyclin D1 transcription (Guan et al., 2007; Hizli et al., 2006; Pysz et al., 2014; Pysz et al., 2009). Studies by our group further showed that PKCα suppresses the expression of members of the Inhibitor of DNA Binding family, Id1, Id2, Id3, and Id4, in intestinal epithelial cells via an ERK-dependent mechanism (Hao et al., 2011), a function that has been noted in other systems (Akakura et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2014). Since Id1 has mitogenic functions, this finding further supports the growth-suppressive activity of PKCα in intestinal tissue.

Extensive evidence supports a tumor suppressive role for PKCα in the intestine and colon. The enzyme is commonly lost in colorectal cancer (Kahl-Rainer et al., 1994; Kahl-Rainer et al., 1996; Suga et al., 1998; Verstovsek et al., 1998) and in murine models of intestinal neoplasia (Klein, I. K. et al., 2000; Oster and Leitges, 2006) (Figure 2A). PKCα deficiency is seen in aberrant crypt foci and pre-malignant adenomas (Gökmen-Polar et al., 2001; Kahl-Rainer et al., 1996; Klein, Irene K. et al., 2000; Oster and Leitges, 2006; Pysz et al., 2009), indicating that expression of the enzyme is suppressed early during tumor development (Figure 2A). Restoration of PKCα expression/activity markedly suppresses anchorage-independent growth of human colon cancer cell lines in vitro and tumor formation in vivo, independent of the status of the APC/β-catenin pathway and other known genetic alterations in colon tumors (Batlle et al., 1998; Pysz et al., 2009). In contrast, PKCα deficiency increases cell proliferation, decreases differentiation, and enhances the transformed phenotype of colon cancer cells (Abraham et al., 1998; Scaglione-Sewell et al., 1998). Strong support for the tumor suppressive effects of PKCα comes from studies by the Leitges group using PKCα knockout mice and the ApcMin/+ mouse model of intestinal neoplasia (Oster and Leitges, 2006). PKCα deficiency enhanced crypt cell mitotic index and promoted the development of spontaneous intestinal tumors even in wild-type mice (i.e., in the absence of the Min mutation). In ApcMin/+ mice, loss of PKCα led to an increased number of tumors in the intestine, with lesions displaying a more aggressive histopathological phenotype characterized by invasion into the muscle layers, central necrotic areas, and less differentiated structure. Consistent with the development of more advanced disease, PKCα-deficient ApcMin/+ mice died significantly earlier than their PKCα-expressing littermates. Mechanistic analysis pointed to a role of PKCα in negative regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway (see Section 2.8.1), while excluding a direct effect of PKCα activity on WNT/APC signaling in this model. Studies by Oh and colleagues, on the other hand, indicate that PKCα signaling can inhibit the WNT/β-catenin pathway by phosphorylating N-terminal residues (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) in β-catenin, marking it for degradation (Gwak et al., 2006; Gwak et al., 2009). The same group identified a small molecule activator of PKCα, CGK062, that promotes PKCα-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser33/Ser37 and downregulation of the protein, thereby suppressing cell proliferation (Gwak et al., 2012). Another study determined that PKCα-mediated phosphorylation of the orphan nuclear receptor, RORα, at Ser35 blocks β-catenin transcriptional activity in colon cancer cells (Lee et al., 2010). Additional studies are needed to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying the tumor suppressive effects of PKCα in intestinal cells. Nonetheless, the tumor suppressive effects of PKCα are relevant to human disease since loss of PKCα is an early event in colon tumorigenesis and is associated with advanced disease and poor prognosis in patients (Chen et al., 2016; Kahl-Rainer et al., 1994; Kahl-Rainer et al., 1996; Suga et al., 1998; Verstovsek et al., 1998).

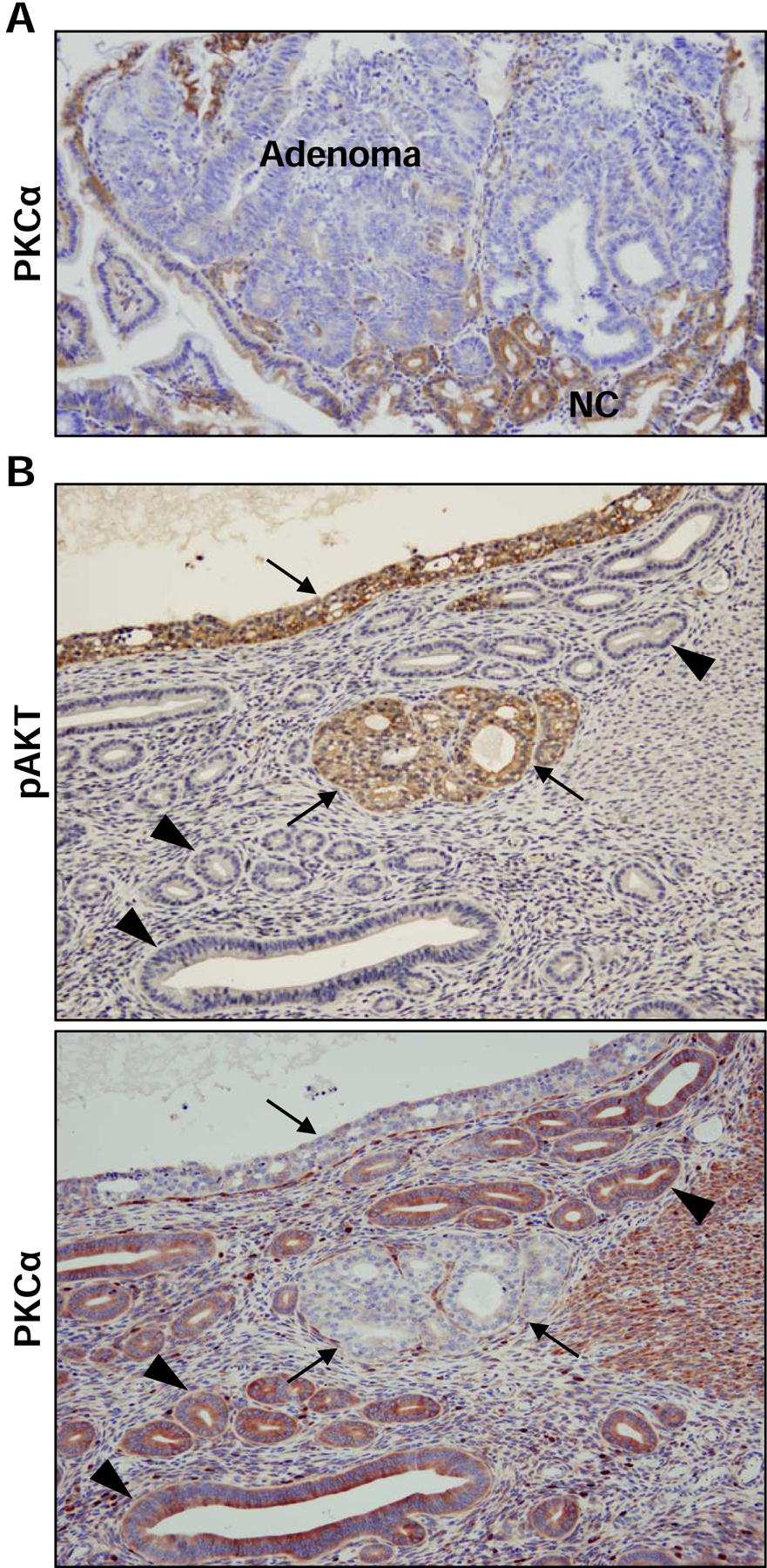

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of PKCα expression in epithelial tumors.

A. APCmin/+ mouse intestine. Note the lack of PKCα staining in adenoma tissue which contrasts with the robust staining of the surrounding normal epithelium. NC: normal crypts. B. PTEN 4−5/+mouse endometrium. Upper panel: Note the robust phospho-AKT (pAKT) staining that is characteristic of hyperplastic tumors (arrows) but not normal epithelium (arrowheads) in this model of endometrial cancer. Lower panel: While PKCα is clearly detected in the phospho-AKT negative normal epithelium (arrowheads), it is uniformly absent from phospho-AKT positive hyperplastic tumors (arrows).

2.3.2. Functions in the epidermis and skin carcinogenesis

Cell proliferation is restricted to the basal layer in the normal epidermis. Terminal differentiation involves detachment of keratinocytes from the basement membrane, migration into the suprabasal compartment, irreversible exit from the cell cycle, and expression of differentiation-specific genes. A role for PKCα in growth arrest and differentiation of normal epidermal cells has been reported by several groups. Early studies by Yuspa and colleagues (Denning et al., 1995) pointed to PKCα as a major player in the induction of differentiation markers during Ca2+-induced keratinocyte differentiation, a role that was confirmed by the Bilke group using PKCα-specific antisense oligonucleotides (Yang et al., 2003). Consistent with this role, immunohistochemical analysis by the Denning laboratory demonstrated PKCα membrane translocation/activation and substrate phosphorylation in suprabasal keratinocytes of the human epidermis, in association with differentiation-associated growth arrest (Bollag, 2009; Tibudan et al., 2002), a pattern also seen in the murine vaginal squamous epithelium (Figure 1B) and reminiscent of that seen for PKCα in intestinal crypts (Section 2.3.1). Additional studies by this group confirmed a role for PKCα in triggering irreversible cell cycle withdrawal in keratinocytes through coordinated changes in cell cycle regulatory molecules (Jerome-Morais et al., 2009; Tibudan et al., 2002). As in intestinal cells, these changes included induction of the CDK inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 and activation of pocket proteins. A growth inhibitory role is further supported by PKCα knockdown studies in human keratinocyte organotypic raft cultures, which resulted in increased basal and suprabasal cell proliferation, decreased differentiation and reduced epidermal stratification (Bollag, 2009; Jerome-Morais et al., 2009). Interestingly, TGFβ-induced growth inhibition of normal human keratinocytes appears to be mediated by PKCα via a mechanism that involves phosphorylation of the EF-hand Ca2+-binding protein, S100C/A11, for p21Cip1 induction (Sakaguchi et al., 2004).

Although the preponderance of evidence points to a tumor suppressive role for PKCα in the skin, the role of the enzyme in skin carcinogenesis remains unclear. PKCα is downregulated in papillomas arising in wild-type mice subjected to the two-stage protocol of skin carcinogenesis, which involves a single, sub-carcinogenic application of the chemical initiator mutagen 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) followed by repeated applications of TPA (Hara et al., 2005). PKCα knockout mice show enhanced papilloma formation in this model and are also significantly more susceptible to skin tumor development by repeated DMBA treatment (Hara et al., 2012), pointing to a key role of PKCα loss in skin carcinogenesis. On the other hand, studies with targeted overexpression of PKCα in the epidermis have given inconsistent results. One group found that PKCα overexpression enhances CXCR2-dependent tumor formation in response to DMBA/TPA treatment (Cataisson et al., 2016; Cataisson et al., 2009), while others have found no effect on tumor development (Jansen et al., 2001; Wang and Smart, 1999). Overexpression of PKCα in the mouse epidermis enhances cytokine signaling (Cataisson et al., 2003; Cataisson et al., 2009; Wang and Smart, 1999), cell differentiation (Palazzo et al., 2017) and apoptosis (Cataisson et al., 2003), and the balance of these effects under different experimental conditions may explain the discrepancies between these studies. Furthermore, consistent with loss of PKCα in papillomas of wild-type mice, expression of the PKCα transgene was suppressed in tumors that formed in the mutant mice (Wang and Smart, 1999), providing a possible explanation for the lack of phenotype in some PKCα overexpression models. Additional studies will be required to resolve these inconsistent results. Interestingly, PKCα expression is downregulated in patient samples of basal cell carcinoma and PKCα deficiency may be associated with increased Gli1 transcriptional activity in these lesions (Neill et al., 2003).

2.3.3. The role of PKCα in endometrial epithelial cells and endometrial cancer

Immunohistochemical analysis by our group showed that PKCα is expressed in the proliferative and secretory endometrial epithelium during the human menstrual cycle and that PKCα expression and activation are dynamically regulated in the murine uterine epithelium during the estrus cycle (Hsu et al., 2018). Levels are generally low in metestrus and diestrus and the enzyme is maintained in an inactive state during these phases. However, coincident with progesterone-induced growth arrest and differentiation during proestrus/estrus, PKCα expression levels markedly increase and the enzyme is robustly activated, as indicated by strong plasma membrane association (Figure 1C). Thus, PKCα activation appears to be positioned to mediate anti-proliferative signaling in the normal murine endometrial epithelium.

Analysis of the effects of PKCα in endometrial cancer cells in vitro has given conflicting results (Haughian and Bradford, 2009; Haughian et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2018; Thorne et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2005). A series of studies by the Bradford group supports a pro-proliferative role of PKCα in these cells. PKCα knockdown in several endometrial cancer cell lines resulted in reduced growth, formation of fewer colonies in soft agar, and impaired xenograft tumor formation in mice (Haughian and Bradford, 2009; Haughian et al., 2009). Constitutively active PKCα, in turn, potentiated estrogen receptor-dependent transcription and increased proliferation of Ishikawa cells (Thorne et al., 2013). However, another study in Ishikawa cells (Wu et al., 2005) indicated that PKCα signaling does not play a significant role and studies in RL95–2 endometrial cancer cells have linked PKCα to retinoic acid-induced differentiation (Carter et al., 1998). Furthermore, work by our group showed potent suppression of anchorage-independent growth by PKCα in a large panel of endometrial cancer cell lines (Hsu et al., 2018). While additional studies are required to resolve these conflicting results, anti-proliferative effects of PKCα are consistent with our finding that PKCα signaling is tumor suppressive in the endometrium (Hsu et al., 2018). Loss of PKCα is an early event in mutant PTEN-driven endometrial tumorigenesis in mice and PKCα deficiency accelerated tumor formation in this model (Hsu et al., 2018) (Figure 2B). Our data point to disruption of a PKCα→PP2A-family phosphatase⊣AKT signaling axis as a key step in endometrial tumor initiation, contributing to robust, unopposed AKT activation and promoting transformation of endometrial cells. This finding is consistent with evidence from Leitges and colleagues that knockout of PKCα enhances PI3K-AKT signaling in mice (Leitges et al., 2002). PKCα is also lost at both the mRNA and protein levels in early stage human endometrial cancers, with loss increasing with more advanced stage (Hsu et al., 2018). PKCα deficiency predicts worse patient outcome, supporting the clinical relevance of its tumor suppressive effects in this tissue (Hsu et al., 2018).

2.4. PKCα signaling in the lung

Limited evidence supports a pro-proliferative role of PKCα signaling in lung cancer cells. PKCα expression is upregulated in many human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (Clark et al., 2003; Salama et al., 2019) and some lung tumor tissues (Wang et al., 2013) compared with primary human lung epithelial cells or adjacent normal lung tissue, respectively. In addition, loss of PKCα in A549 NSCLC cells by treatment with PKCα-specific siRNA or transfection of miR203, a direct regulator of PKCα expression, suppressed cell proliferation (Wang et al., 2013), while overexpression of the kinase had the opposite effect (Wang et al., 2013). PKCα silencing experiments further revealed that NSCLC cells expressing mutant EGFR rely on PKCα for activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway and to facilitate growth under serum-free conditions (Salama et al., 2019).

In contrast to these findings, other studies support an anti-proliferative, tumor suppressive role of PKCα in the lung. The Kazanietz group demonstrated that S-phase-specific activation of endogenous PKCα in NSCLC cells results in p21Cip1 upregulation, G2/M cell cycle arrest, and cell senescence (Oliva et al., 2008). The link between PKCα signaling and induction of senescence observed in this study has been confirmed by others (Akakura et al., 2010). Analysis of PKCα in gene expression datasets by Fields and colleagues revealed significant downregulation of the enzyme in the three major subtypes of human NSCLC (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, and large cell carcinoma), with PKCα loss increasing with tumor stage (Hill et al., 2014). Immunohistochemical analysis of patient tissues and lung adenomas arising in the LSL-Kras murine lung cancer model confirmed that loss of PKCα is a frequent event in NSCLC (Hill et al., 2014). Furthermore, genetic deletion of PKCα in three murine lung adenocarcinoma models (LSL-Kras, LA2-Kras, and urethane exposure) significantly increased tumor number, size, and aggressiveness, while promoting progression from adenoma to carcinoma and reducing mouse survival (Hill et al., 2014). Consistent with the findings of Kazanietz et al. (Oliva et al., 2008), PKCα deficiency also resulted in bypass of oncogene-induced senescence. Loss of PKCα expanded the tumor-initiating bronchio-alveolar stem cell population, both in vitro and in vivo, an effect that was attributed to relief from a PKCα→p38MAPK⊣TGFβ signaling axis that suppresses Id protein expression, inhibits cell proliferation, and regulates KRAS-induced senescence. The basis for the opposing activities of PKCα in lung cancer cells remains to be defined in future studies and may reflect inherent differences in the lung cancer subtypes analyzed (e.g., tumors with wild-type or activating mutations of EGFR).

2.5. The mammary epithelium and breast cancer cells

Limited studies in normal and non-transformed mammary epithelial cells provide conflicting data on the role of PKCα in regulation of cell growth and differentiation in mammary tissue. Elevated levels of PKCα in COMMA-1D mouse mammary epithelial cells resulted in anchorage-independent growth in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo (Zeng et al., 2002). In contrast, overexpression of PKCα in non-tumorigenic MCF10A human mammary epithelial cells suppressed cell proliferation, with cells accumulating in G1 phase of the cell cycle likely as a result of increased p27Kip1 expression (Sun and Rotenberg, 1999). It should be noted, however, that the validity of MCF10A cells as a model of normal mammary epithelial cells has been questioned (Qu et al., 2015). Thus, in depth studies of the expression, subcellular distribution and function of PKCα in normal mammary epithelium are required to resolve these conflicting findings and determine the role of PKCα in normal mammary biology.

Analysis of PKCα function in breast cancer cells provides a somewhat clearer picture. One of the earliest reports of pro-proliferative effects of PKCα in any system resulted from analysis of breast cancer cells by the Parker group (Ways et al., 1995). Ectopic overexpression of PKCα in PKCα-low MCF7 breast cancer cells enhanced their proliferative rate and tumorigenic properties in vitro and in nude mice. Notably, PKCα overexpression reduced estrogen receptor levels, indicating that PKCα may regulate the switch from ER-positive to ER-negative status in breast cancer. Tonetti et al. confirmed these intriguing results in a series of compelling studies. Stable expression of PKCα in hormone-dependent T47D breast cancer cells resulted in reduced ER function, increased proliferation rate, and hormone-independent growth that could not be inhibited by the antiestrogen tamoxifen (Chisamore et al., 2001; Tonetti et al., 2000; Tonetti et al., 2003). PKCα may engage an AP-1-Notch-4 signaling pathway to promote ER-independent, tamoxifen-resistant proliferation of breast cancer cells (Yun et al., 2013). A caveat of these findings, discussed by the authors of both reports, is that overexpression of PKCα altered the levels of several other members of the PKC family, with marked upregulation of PKCβ observed by both groups. However, a positive role for PKCα signaling in breast cancer cell proliferation was demonstrated more recently by the Larsson group through PKCα knockdown experiments in MDA-MB-231 cells (Lonne et al., 2010). These investigators also confirmed the association between PKCα expression and ER negativity/increased proliferative activity of breast cancer cells, as well as poor survival of breast cancer patients. Interestingly, PKCα can be upregulated and activated by ErbB2 in breast cancer cells through a Src-dependent mechanism, and ErbB2 overexpression correlates with PKCα membrane localization in breast tumors (Tan et al., 2006). A recent study by the Weinberg group identified a platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-PKCα-FRA1 signaling network that is activated specifically in breast cancer stem cells, and appears to play a key role in breast cancer initiation (Tam et al., 2013). However, analysis of the role of PKCα in all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced inhibition of breast cancer cell growth has yielded conflicting results. Consistent with a growth promoting role, studies in ER-negative, retinoic acid receptor-positive SKBR-3 breast cancer cells pointed to suppression of a PKCα-ERK signaling axis as a key event in ATRA-induced G1 arrest (Nakagawa et al., 2003). In contrast, studies by the Talmage group demonstrated a requirement for PKCα expression and activity in retinoic acid-induced growth arrest of ER-positive T47D cells (Cho and Talmage, 2001; Cho et al., 1997), pointing to a potential role for ER-signaling in modulating the tumorigenic effects of PKCα.

2.6. Glioma cells

Consistent with high expression of PKCα protein in gliomas relative to astrocytes and low grade astrocytomas (Baltuch et al., 1995; Mandil et al., 2001), several studies support a pro-proliferative role of the enzyme in glioma. Using PKCα-specific antisense oligonucleotide, the Yong group showed that PKCα deficiency reduces the proliferation rate of rat C6 glioma cells (Baltuch et al., 1995). Follow-up studies by the same group determined that PKCα signaling is necessary and sufficient for PMA-induced cell cycle progression in several human glioma cell lines (Besson and Yong, 2000). Antisense experiments pointed to an unexpected role of p21Cip1 in facilitating cell cycle progression and hyperproliferation mediated by PKCα in these cells (Besson and Yong, 2000). In keeping with these findings, PKCα overexpression in the human U87 glioma cell line enhanced cell proliferation via a mechanism involving the regulatory domain of the kinase (Mandil et al., 2001). Interestingly, the Parker group reported that PKCα protein but not catalytic activity is required for U87MG glioma cell proliferation and that the fully phosphorylated, folded form of the kinase confers activity-independent effects (Cameron et al., 2008). Analysis of the expression of lncRNAs in human glioma cells identified TCONS_00020456 as an oncosuppressor that targets SMAD2/PKCα signaling to inhibit glioma cell proliferation in vitro and tumor progression in vivo (Tang et al., 2020). While these studies support a pro-proliferative role of PKCα signaling in glioma, it is becoming increasingly evident that glioma cell lines may not be optimal models for studying the disease (Lenting et al., 2017). In this regard, two recent studies (Goode et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2018) involving genomic profiling of patient samples identified a novel mutation in PRKCA (D463H) as a hallmark of chordoid gliomas, with characteristics of oncogenic, gain-of-function mutations rather than inactivating alterations. While expression of wild-type or kinase-dead D463A PKCα in immortalized human astrocytes, the cells of origin of choroid gliomas, failed to affect proliferation, the D463H mutant protein was shown to drive MEK-dependent, anchorage-independent growth of these cells. D463H PKCα is less stable than the wild type enzyme (with a half-life of 4.5 h vs 17 h, respectively), and displays a defect in membrane anchorage (Rosenberg et al., 2018). The authors suggest that neomorphic functions of the mutant kinase may reflect altered substrate specificity. It is also possible that the mutation abolishes kinase activity entirely and that the oncogenic properties of the mutant protein involve novel kinase-independent mechanisms. Additional studies using relevant preclinical models are required to better understand the role of PKCα signaling in glioma.

2.7. Other tumor types

Evidence for the involvement of PKCα in regulation of cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in the liver, pancreas, and melanocytes/melanoma will be summarized briefly here as these tissues have been less extensively studied. A pro-proliferative role for PKCα in hepatocellular carcinoma is supported by some studies. Antisense inhibition of PKCα expression in poorly differentiated human hepatocellular carcinoma cells reduced cell growth, in association with p21Cip1 induction and cyclin D1 downregulation (Wu et al., 2008), and stable knockdown of PKCα using siRNA technology slowed the proliferation of SK-Hep-1 cells (Hsieh et al., 2007). In contrast, the finding that PKCα inhibited the growth of HepG2 cells points to an anti-proliferative role in hepatocellular carcinoma. PKCα-mediated growth inhibition in these cells involved RAS- and RAF-independent activation of MEK/ERK (Wen-Sheng, 2006) and ERK-dependent induction of miR-101, which targets two subunits of the PRC2 methyltransferase complex, enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and embryonic early development (EED), reducing methylation of histone 3 lysine 27 to regulate gene expression (Chiang et al., 2010).

Conflicting results have also been reported in pancreatic cancer. Consistent with frequent upregulation of PKCα expression in pancreatic tumors, some studies support a pro-proliferative role of PKCα in pancreatic cancer cells. Inhibition of PKCα expression in AR4–2J cells using antisense mRNA markedly reduced cell growth, and the extent of growth inhibition paralleled the reduction in PKCα immunoreactivity (Zhang et al., 1997). Conversely, overexpression of PKCα enhanced the tumorigenicity of HPAC cells in mice, while decreasing survival (Denham et al., 1998). However, an anti-proliferative role is indicated by the G1 phase arrest induced by activation of endogenous PKCα or microinjection of recombinant PKCα in DanG pancreatic cancer cells, an effect that involves p21Cip1 induction, inhibition of cdk2 activity, and hypophosphorylation of pRb (Detjen et al., 2000).

Studies by several groups point to a role of PKCα in melanoma cell growth arrest and differentiation. In early studies, Niles and colleagues showed that overexpression of PKCα (2–4 fold) in B16 mouse melanoma cells resulted in longer doubling times, diminished anchorage-independent growth, and increased melanin production (Gruber et al., 1992). PKCα overexpressing clones were further shown to produce smaller tumors with longer latency in mice. The same group determined that PKCα mRNA and protein are upregulated 6–8 fold during retinoic acid induced growth arrest and differentiation of melanoma cells (Niles and Loewy, 1989), an effect that was confirmed by others (Oka et al., 1993), and that PKCα is required for the differentiation program in these cells (Gruber et al., 1992). Follow-up studies excluded a requirement for PKCα enzyme activity in the effect, suggesting that PKCα works through a nonenzymatic protein-protein mechanism to mediate the actions of retinoic acid in B16 melanoma cells (Niles, 2003). PKCα has also been shown to play a critical role in mannosylerythritol lipid-induced differentiation of melanoma B16 cells (Zhao et al., 2001). Consistent with these findings, PKCα deficiency enhances DNA synthesis in A-375 human melanoma cells, while increased levels of the enzyme have anti-proliferative effects in these cells (Krasagakis et al., 2002; Krasagakis et al., 2004).

2.8. Underlying mechanisms

2.8.1. Modulation of growth factor receptor signaling

Extensive evidence supports the ability of PKCα to modulate signaling from growth factor receptors, a function that is thought to contribute directly to the cancer-related effects of the enzyme. Almost all these studies point to an inhibitory role of PKCα on growth factor activity. The best characterized targets of the kinase are members of the epidermal growth factor receptor family, including the EGFR and ErbB2. Early studies determined that phorbol esters can downmodulate EGFR signaling in non-transformed cells as well as cancer cells (Friedman et al., 1984), an effect that has been implicated in both negative feedback following activation by EGF (Chen et al., 1996; Welsh et al., 1991) and in transmodulation of EGFR signaling by multiple G-protein coupled receptors, including receptors for prostaglandin F2α, angiotensin II, vasopressin, carbachol, bombesin, and luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) receptors (de Asua and Goin, 1992; Santiskulvong and Rozengurt, 2007; Yates et al., 2005).

Sequencing data and mutational analysis have led to a consensus that the effects of PKC activation are mediated by phosphorylation of Thr654 in the juxtamembrane region of EGFR (Bao et al., 2000; Countaway et al., 1990; Davis and Czech, 1985; Hunter et al., 1984; Lin, 1986). While studies that directly address the role of PKCα in phosphorylation of Thr654 have been limited, siRNA-mediated knockdown experiments have pointed to PKCα as the major isoform that phosphorylates this site (Koese et al., 2013; Macdonald-Obermann and Pike, 2009; Morrison et al., 1993; Santiskulvong and Rozengurt, 2007) (although PKD has also been implicated in Thr654 phosphorylation in some circumstances (Bagowski et al., 1999; Kluba et al., 2015) such as following PDGFR activation).

PKC-mediated phosphorylation of EGFR reduces high affinity binding of EGF and the autophosphorylation activity of the receptor, thereby inhibiting activation of downstream effectors. These effects that can be seen both in cells and with purified kinases in vitro (Bao et al., 2000; Downward et al., 1985; Hunter et al., 1984; Lund et al., 1990). Mutation of Thr654 to alanine inhibited the effects of PKC (Lund et al., 1990), while mutation to glutamate reduced kinase activity of EGFR in response to EGF, confirming the involvement of Thr654 (Morrison et al., 1993). However, it should be noted that these mutations did not totally block the effects of PKC agonists (Lund et al., 1990; Morrison et al., 1993), indicating that other factors are also involved. Since high affinity binding of EGF and EGFR activation require receptor dimerization (Bjorkelund et al., 2013; Ozcan et al., 2006), these effects may be explained by the finding that PKC activation or mutation of Thr654 to glutamate inhibits ligand-induced EGFR dimerization (Kluba et al., 2015). This idea is supported by evidence that the juxtamembrane domain containing Thr654 is involved in the link between receptor dimerization and ligand affinity (Macdonald-Obermann and Pike, 2009).

Additional effects of PKCα-mediated phosphorylation include disruption of ligand-dependent EGFR trafficking and degradation in the endolysosomal compartment (Bakker et al., 2017). These effects are consistent with extensive evidence for the involvement of PKCα signaling in regulation of membrane trafficking, including endocytosis (Alvi et al., 2007; Elnakat et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2019; Ranganathan et al., 2004), endocytic recycling (Alvi et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2014; Hellberg et al., 2009; Idkowiak-Baldys et al., 2006), and exocytosis (Tzeng et al., 2017). Studies in B82 cells, A431 cells and normal human fibroblasts expressing wild-type Thr654 or Ala654 mutant EGFR (Koese et al., 2013; Lund et al., 1990) indicate that, in addition to inhibition of its tyrosine kinase activity, Thr654 phosphorylation can prevent internalization and degradation of EGFR. The retention of EGFR at the plasma membrane appears to reflect a direct effect of Thr654 phosphorylation on trafficking rather than inhibition of the tyrosine kinase activity of the receptor, since it was seen with an EGFR truncation mutant lacking enzymatic activity (Koese et al., 2013; Lund et al., 1990). In contrast, other studies using EGFR expressing CHO and HEK293 cells did not observe an effect of PKC agonists on ligand-induced receptor internalization; instead, PKC activation inhibited subsequent degradation of the EGFR through Thr654-dependent redirection of the internalized receptor away from late endosomes and into a recycling compartment (Bao et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2013). This effect involves a caveolin- and ganglioside-containing sub-compartment of recycling endosomes, termed the pericentrion (El-Osta et al., 2011; Idkowiak-Baldys et al., 2006), that localizes to the perinuclear region in a PKC- and phospholipase C-dependent manner (Liu et al., 2013). Wild-type EGFR, but not a Thr654 to alanine mutant, is redirected to this compartment and thereby sequestered away from ligands, remaining inactive (Liu et al., 2013). The differences between these studies likely reflect differential engagement of interaction partners, substrates and downstream targets of PKCα in these cells. For example, studies in A431 squamous cell carcinoma cells, head-and-neck cancer cells and breast cancer cells have determined that annexin A6 acts as a scaffold to recruit PKCα to the EGFR and promote Thr654 phosphorylation, resulting in a reduction in ligand-induced EGFR auto-phosphorylation, internalization and degradation (Koese et al., 2013). This effect likely contributes to the tumor suppressive effects of annexin A6 in several cancer types (Qi et al., 2015). On the other hand, a caveolin-1 and ganglioside GM3-dependent complex consisting of EGFR, CD82 and PKCα promotes internalization of the receptor without triggering its degradation (Wang, X.Q. et al., 2007), pointing to its redirection to recycling endosomes/the pericentrion. Thr654 phosphorylation also inhibits binding of calmodulin to the juxtamembrane region of EGFR (Aifa et al., 2006), an interaction that has been implicated in regulation of EGFR activity and trafficking though early endosomes (Li et al., 2012; Tebar et al., 2002). There is also evidence that PKCα can promote the degradation of EGFR by destabilizing the de-ubiquitinase, ubiquitin-specific protease 8 (USP8), via inhibition of AKT activity (Cai et al., 2010).

In addition to the EGFR, PKCα has been implicated in regulation of other growth factor receptors, particularly by promoting trafficking to a perinuclear recycling compartment. ErbB2 has a threonine in its juxatamembrane domain (Thr686) that is analogous to Thr654 in EGFR. PKC agonist treatment induces phosphorylation at Thr686 of ErbB2, reduces tyrosine phosphorylation and activity of the receptor and, as seen with the EGFR in some studies, increases its internalization and trafficking to a perinuclear recycling compartment without triggering its degradation (Bailey et al., 2014; Ouyang et al., 1998; Ouyang et al., 1996). Although the involvement of PKCα in Thr686 phosphorylation of ErbB2 has not been tested directly, its role is supported by the ability of (a) constitutively active PKCα to trigger internalization of ErbB2 in SKBR3 cells (Jeong et al., 2019), and (b) PKCα-knockdown to block trafficking of ErbB2 to a perinuclear recycling compartment in response to PKC-agonist treatment or HSP90 inhibition. PKCα also regulates trafficking of cMet (the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor) to a perinuclear compartment without affecting its initial internalization or its activity (Kermorgant et al., 2004). However, the situation for the PDGFβ receptor is somewhat different: here PKCα also redirects the receptor to a recycling compartment but, in this case, the result is rapid recycling rather than perinuclear sequestration (Hellberg et al., 2009). PKCα functions in a negative feedback loop to regulate the RET tyrosine kinase (Andreozzi et al., 2003). RET binds to and activates PKCα and PKCα, in turn, phosphorylates and downregulates RET, inhibiting mitogenic signaling.

PKCα can also regulate growth factor signaling by acting downstream of growth factor receptors. For example, PKCα regulates insulin action by inhibiting the activation of MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT signaling downstream of the insulin receptor. Blockade of PI3K-AKT activation involves PKCα binding to insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) and inhibition of its phosphorylation (Caruso et al., 1999; Oriente et al., 2005), an effect that may be mediated by direct phosphorylation of Ser24 to prevent phosphoinositide binding of the IRS1 PH domain (Nawaratne et al., 2006). PKCα-mediated inhibition of PI3K-AKT signaling has been observed in multiple cell types, including intestinal epithelial cells (Guan et al., 2007), endometrial cancer cells (Hsu et al., 2018), prostate cancer cells (Tanaka et al., 2003), and head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells (Hoshino et al., 2012), and the effect appears to be accomplished by several mechanisms. In intestinal and HNSCC cells, PKCα suppresses the catalytic activity of PI3K (Guan et al., 2007; Hoshino et al., 2012); in prostate cancer cells, on the other hand, PKCα reduces AKT phosphorylation without affecting PI3K activity (Tanaka et al., 2003). The exact mechanism by which PKCα reduces PI3K activity remains to be elucidated: while the effect has been linked to phosphorylation of Ser361/652 in the p84α regulatory subunit of PI3K in HNSCC cells (Hoshino et al., 2012), in vitro analysis has suggested a role for direct phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit (Sipeki et al., 2006). Analysis in endometrial and prostate cancer cells indicates that PP2A-dependent, PHLPP1/2-independent dephosphorylation of AKT downstream of PI3K can also be involved (Hsu et al., 2018; Tanaka et al., 2003). As discussed above, inhibition of AKT by PKCα in HeLa cells destabilized the de-ubiquitinase, USP8, leading to enhanced ubiquitination and degradation of EGFR (Cai et al., 2010). Consistent with the reported growth inhibitory effects of sustained ERK-MAPK signaling in several systems, PKCα can also activate the MEK-ERK pathway to inhibit growth factor receptor signaling, as observed in intestinal epithelial cells (Clark et al., 2004), colon cancer cells (Hao et al., 2011; Kaur et al., 2018; Pysz et al., 2014), and hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Wen-Sheng and Jun-Ming, 2005), with dominant effects of the PKCα-ERK module over growth promoting signaling from serum growth factors (Clark et al., 2004; Pysz et al., 2014). As noted in section 2.3, PKCα has also been shown to regulate WNT signaling by phosphorylating N-terminal serine residues in β-catenin to mark it for degradation (Gwak et al., 2006; Gwak et al., 2009) or by phosphorylation of the orphan nuclear receptor, RORα, at Ser35 to block β-catenin transcriptional activity (Lee et al., 2010). PKCα may also engage an AP1-Notch-4 signaling pathway to promote ER-independent proliferation of breast cancer cells (Yun et al., 2013).

2.8.2. Cell cycle specific effects

Although anti- and pro-proliferative effects of PKCα have been well documented in many cancer types, relatively few studies have investigated specific effects of the kinase on the cell cycle. Available evidence points to D-type cyclins and the CDK inhibitory proteins, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, as important targets of PKCα activity (Black and Black, 2012; Black, 2001). As discussed above, our analysis in intestinal epithelial and colorectal cancer cells delineated a program of cell cycle withdrawal triggered by PKCα that involves rapid downregulation of D-type cyclins and induction of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, inhibition of G1/S cyclin/CDK complex activity, and changes in the pocket proteins, p107, pRb, and p130, characteristic of G1 arrest and cell cycle withdrawal (Frey et al., 2000; Frey et al., 1997; Pysz et al., 2009). Delayed progression through G2/M was also noted. Similar effects on D-type cyclins and/or CDK inhibitors were reported in keratinocytes (Jerome-Morais et al., 2009; Tibudan et al., 2002) and DanG pancreatic cancer cells (Detjen et al., 2000). In NSCLC cells, p21Cip1 was induced when PKCα was activated in S-phase, but not G1, and led to G2/M arrest and a senescence phenotype (Oliva et al., 2008). PKCα overexpression in non-tumorigenic MCF10A human mammary epithelial cells inhibited G1-S phase transit as a result of increased p27Kip1 expression (Sun and Rotenberg, 1999). Interestingly, induction of p27Kip1 by PKCα in intestinal epithelial cells, keratinocytes, and pancreatic cancer cells was delayed relative to upregulation of p21Cip1 (Detjen et al., 2000; Frey et al., 1997; Jerome-Morais et al., 2009; Tibudan et al., 2002), suggesting that the prolonged activation of the enzyme seen in differentiated epithelial tissues may help maintain their growth arrested state by supporting the expression of p27Kip1 (Figure 1).

Regulation of CDK inhibitory proteins and D-type cyclins also plays a role in growth-promoting functions of PKCα signaling. Antisense-mediated PKCα knockdown in poorly differentiated human hepatocellular carcinoma cells induced G1 arrest in association with p21Cip1 induction and cyclin D1 downregulation (Wu et al., 2008). Interestingly, in glioma cells, PKCα upregulated p21Cip1 without affecting cyclin D1 levels (Besson and Yong, 2000), and increased levels of p21Cip1 were required to promote assembly of cyclin D-CDK4/6 complexes and phosphorylation/inactivation of pRb (Besson and Yong, 2000). This pro-proliferative role of p21Cip1 points to the importance of cyclin D downregulation for the growth arrest induced by PKCα in cells where it also induces p21Cip1.

PKCα uses multiple mechanisms to regulate cell cycle proteins. In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, PKCα appears to promote p21Cip1 upregulation by a p53-dependent mechanism (Wu et al., 2008). In contrast, PKCα induces p21Cip1 expression in p53 mutant colon (Pysz et al., 2009) and pancreatic (Detjen et al., 2000) cancer cells and the upregulation of p21Cip1 in intestinal epithelial cells and colon cancer cells is mediated by MEK-ERK signaling (Clark et al., 2004). PKCα signaling also regulates cyclin D1 levels by two different mechanisms in intestinal epithelial and colon cancer cells. The enzyme inhibits cyclin D1 translation through PP2A-mediated activation of the translational repressor 4E-BP1 (Guan et al., 2007; Hizli et al., 2006; Pysz et al., 2009) and represses cyclin D1 transcription, likely through a MEK-ERK dependent mechanism (Clark et al., 2004; Guan et al., 2007; Pysz et al., 2009).

3. Role of PKCα in migration and metastasis

PKCα signaling has been implicated in cell motility, migration, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, and metastasis in many tumor types. In contrast to the complexity of PKCα function in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and tumorigenesis (Section 2), the kinase generally plays a positive role in migratory processes and the metastatic program. These effects likely reflect the well documented functions of PKCα in regulation of the cytoskeleton, adhesion, motility and migration in normal cells. PKCα localizes at focal adhesions, filopodia, and lamellipodia in vitro and interacts with and/or phosphorylates a number of proteins that are associated with these structures and with cell migration, including syndecan-4 (Koo et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2003; Oh et al., 1997), Rho guanidine dissociation inhibitor 1 (RhoGDI1) (Dovas et al., 2010), p190RhoGAP (Lévay et al., 2009),β1 integrin (Ng et al., 1999a), formin-like 2 (FMNL2) (Kitzing et al., 2010), filamin A (Urra et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2010), vinculin (Ziegler et al., 2002), and fascin (Anilkumar et al., 2003).

PKCα activity markedly increases the motility and migration of colon cancer cells (Hu et al., 2013; Masur et al., 2001), especially in cells with low E-cadherin expression. The enzyme also has pro-migratory effects in melanoma cells (Byers et al., 2010; Sullivan et al., 2000), breast cancer cells (Parsons et al., 2002; Pham et al., 2017), lung cancer cells (O’Neill et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013), and kidney cancer cells among others. A role for PKCα in EMT has been described in multiple systems (Kyuno et al., 2013; Llorens et al., 2019; Qi et al., 2014). PKCα activity regulates the expression and stability of transcription factors that play key roles in regulation of the EMT program, including ZEB1 (Llorens et al., 2019), ZEB2 (Abera and Kazanietz, 2015), Snail (Abera and Kazanietz, 2015; Kyuno et al., 2013), and Twist1 (Abera and Kazanietz, 2015; Tedja et al., 2019), with phosphorylation of Twist1 at ser144 by PKCα preventing its ubiquitination and degradation (Tedja et al., 2019). Notably, a recent study by the Weinberg group identified a PKCα-FRA1 signaling axis as a gatekeeper of the EMT program in TNBC (Tam et al., 2013). PKCα signaling can also promote tumor cell invasion, as shown in colon cancer cells (Batlle et al., 1998), hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Hsieh et al., 2007), pancreatic cancer cells (Kyuno et al., 2013), endometrial cancer cells (Haughian and Bradford, 2009), melanoma cells (Putnam et al., 2009), and glioblastoma cells (Lin et al., 2010). Upregulation and activation of PKCα downstream of ErbB2 is critical for breast cancer cell invasion (Tan et al., 2006) and induction of matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-9 expression by PKCα is required for glioblastoma invasion (Lin et al., 2010). A recent study in NSCLC cells (Cooke et al., 2019) using RNA interference to silence individual PKC isozymes demonstrated the ability of PKCα, but not PKCδ or PKCε, to potently induce the expression of the extracellular matrix proteases MMP1, MMP9, and MMP10 (Cooke et al., 2019).

The involvement of PKCα in metastasis has been best characterized in breast cancer. PKCα downregulation by microRNA-200b in triple negative breast cancer cells suppressed metastasis in an orthotopic mouse xenograft tumor model (Humphries et al., 2014). Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of PKCα by in vivo administration of the PKCα selective inhibitory peptide, αV5–3, markedly reduced intravasation and lung seeding of mammary cancer cells by suppressing MMP-9 and NF-κB activity and cell surface expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Kim et al., 2011). Interestingly, PKCα inhibition had no effect on the primary tumor, indicating that PKCα signaling does not play a role in proliferation and survival per se in this model. In human melanoma cells, inhibition of PKCα expression with a phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotide (ISIS-3521, also known as aprinocarsen) suppressed metastatic potential in athymic mice (Dennis et al., 1998) and the metastasis suppressor KiSS1 reduces human ovarian cancer metastasis by inhibiting the activity of PKCα (Jiang et al., 2005).

A major mechanism by which PKCα promotes cell migration is through coordinated activation of Rho-GTPases, particularly RhoA and Rac1. Multiple steps in cell migration are regulated by these GTPases, including formation of actin-rich lamellipodia and invadipodia, focal adhesion assembly at the leading edge, and secretion of MMPs (Clayton and Ridley, 2020). Regulation of RhoA and Rac1 by PKCα is mediated by the interaction of its catalytic domain (but not that of PKCδ or PKCε (Lim et al., 2003)) with the cytoplasmic tail of syndecan-4, a ubiquitously expressed heparin sulfate proteoglycan that has been implicated in regulation of cellular migration, mechanotransduction, endocytosis, and proliferation (Elfenbein and Simons, 2013). Syndecan-4 acts as a receptor for heparin binding extracellular proteins including growth factors, such as FGF2, VEGF and PGDF, and extracellular matrix components, such as fibronectin and vitronectin (Elfenbein and Simons, 2013). Following engagement by heparin binding proteins, syndecan-4 undergoes PI(4,5)P2-dependent oligomerization, which results in direct activation of PKCα (Koo et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2003; Oh et al., 1997). This activation differs from the canonical PKCα activation in that it is independent of DAG and Ca2+, but is dependent on PI(4,5)P2 and syndecan-4 oligomerization (Horowitz et al., 1999; Horowitz and Simons, 1998). Interestingly, PKCδ may negatively regulate this pathway through phosphorylation of syndecan-4 on Ser183, which inhibits PI(4,5)P2 binding and oligomerization, thus preventing PKCα activation (Murakami et al., 2002).

As with other GTPases, RhoGTPases act as molecular switches which are active in the GTP bound state and inactive when bound to GDP (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002; Parri and Chiarugi, 2010). Both the intrinsic GTPase activity of these proteins and the dissociation of GDP are slow; thus, their activity is primarily regulated by proteins that modulate GTPase activity and GDP/GTP exchange. These proteins are activated by a number of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that enhance the dissociation of GDP and thus enable binding of GTP. Conversely, RhoGTPases are negatively regulated by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), which enhance their intrinsic GTPase activity, and by guanidine dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), which sequester RhoGTPases away from the membrane while inhibiting GDP/GTP exchange (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002; Parri and Chiarugi, 2010). In the unstimulated state, syndecan-4 suppresses Rho-GTPase activity by forming a complex with synectin and RhoGDI1 (RhoGDIα), which enhances the interaction of Rho-GTPases with RhoGDI1 (Elfenbein et al., 2009). Following syndecan-4 oligomerization, PKCα phosphorylates RhoGDI1 at Ser34, which releases RhoA (Dovas et al., 2010), and ser96, which releases RhoG and Rac1 (Dovas et al., 2010; Elfenbein et al., 2009; Knezevic et al., 2007). Activation of Rac1 following its release is also dependent on RhoG which forms a Rac-specific GEF by complexing with ELMO and Dock180 (Elfenbein et al., 2009; Katoh et al., 2006). Thus, while syndecan-4 restricts Rho-GTPase activity in the unstimulated state, its ability to stimulate PKCα following oligomerization allows for selective activation of RhoA and Rac1 at sites of matrix and/or growth factor binding to support directional migration (Bass et al., 2007).

In addition to promoting the spatial activation of Rho-GTPases at the leading edge, PKCα helps to regulate the phasic activation of Rac1 and RhoA during adhesion and migration through p190RhoGAP. PKCα phosphorylates p190RhoGAP at Ser1221 and Thr1226 (Lévay et al., 2009), blocking its interaction with acidic phospholipids and increasing its activity towards RhoA, while decreasing its activity towards Rac1 (Lévay et al., 2009). This supports the initial inhibition of RhoA upon matrix engagement that is required for proper adhesion formation and membrane protrusion at the leading edge (Bidaud-Meynard et al., 2017; Lévay et al., 2009).

The effects of PKCα on cell motility, migration and invasion are also mediated by its ability to regulate integrin recycling, an essential event in migration and metastasis (Ng et al., 1999a). PKCα activation by syndecan-4 or PMA upregulates β1 integrin and induces dynamin- and caveolin-dependent internalization of α5β1 integrin (Bass et al., 2011). As with activation of Rac1, the ability of PKCα to promote integrin endocytosis involves downstream activation of RhoG (Bass et al., 2011); however, it also involves direct interaction between PKCα and β1 integrin (Ng et al., 1999a) and phosphorylation of FMNL2 (Kitzing et al., 2010). The interaction of PKCα with the cytoplasmic tail of β1 integrin is mediated by the V3 variable domain of the enzyme (Parsons et al., 2002) and is thus distinct from its interaction with syndecan-4, which is mediated by the catalytic domain (Lim et al., 2003). Preventing the interaction between PKCα and β1 integrin with a blocking peptide or inhibiting PKCα-induced β1 integrin internalization blocks migration of breast cancer cells (Ng et al., 1999a; Parsons et al., 2002).

FMNL2 belongs to a group of Diaphanous (mDia)-related formins that regulate actin polymerization and are intimately involved in migration control (Bogdan et al., 2013; Breitsprecher and Goode, 2013). Knockdown of FMNL2 reduces PKCα-induced internalization of α2β1 and α5β1 integrins and cell migration/invasion, pointing to a role for FMNL2 in mediating the effects of PKCα on cell migration, invasion and metastasis (Wang et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2018). FMNL2 is initially targeted to lamellipodia and filopodia by RhoC and CDC42 (Block et al., 2012; Kitzing et al., 2010), where it interacts directly with PKCα (Wang et al., 2015). PKCα activates FMNL2 through phosphorylation of Ser1072, promoting FMNL2 binding to the cytoplasmic tail of α integrin and actin-dependent internalization of FMNL2/α integrin/β1 integrin complexes (Wang et al., 2015).

PKCα can also drive lamellipodia protrusion at the leading edge and cell migration through effects on the actin cytoskeleton. PKCα interacts with filamin A (Tigges et al., 2003; Urra et al., 2018), a crosslinker of polymerized actin with crucial roles in adhesion and migration (Feng and Walsh, 2004; Zhou et al., 2010). Phosphorylation of filamin A on Ser2152 by PKCα protects filamin A from degradation and enhances cytoskeletal remodeling and cell migration (Urra et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2010). Another mechanism by which PKCα can enhance migration is through interaction with Disks-Large 1 (DLG1, SAP97) (O’Neill et al., 2011), a member of the Scribble/LGL/DLG polarity complex that regulates cell polarity and directed migration (Marziali et al., 2019; Saito et al., 2018). DLG1 is a substrate for PKCα and these proteins colocalize at the leading edge in migrating cells (O’Neill et al., 2011). PKCα contains a PDZ-ligand at its C-terminus that mediates direct binding to the third PDZ-domain of DLG1. Deletion of the PDZ-ligand or knockdown of DGL1 reduces the ability of PKCα to promote migration, confirming the role of this interaction in the pro-migratory effects of PKCα (O’Neill et al., 2011). Although the precise mechanisms by which the PKCα-DLG1 interaction affects migration remains to be determined, it likely reflects, at least in part, the role of DLG1 in establishing front rear polarity in migrating cells (Marziali et al., 2019; O’Neill et al., 2011).

Other less well characterized mechanisms for regulation of migration by PKCα include inhibition of secretion of the metallopeptidase inhibitor TIMP1 through Rab37 phosphorylation (Tzeng et al., 2017), suppression of p120catenin expression through FOXC2 (Pham et al., 2017), and activation of p38 MAPK (Hsieh et al., 2007).

As noted for PKCα-mediated regulation of cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, effects of the enzyme on migration in cancer cells can be context-dependent. Consistent with a role in regulation of invasion and metastasis, a computational network analysis of published data identified PKCα as one of the top ten signaling hubs in control of focal adhesions and invadopodia (Hoshino et al., 2012). However, follow-up studies in HNSCC cells, which retain high levels of PKCα, indicated that the effects of the kinase on the invasive phenotype are dependent on the status of the PI3K/PTEN signaling axis. In PI3K/PTEN wild-type cells, PKCα knockdown reduced invadopodia formation, indicating that PKCα enhances their invasive phenotype. However, in cells with activating mutations in PI3K or loss of PTEN, PKCα knockdown enhanced invadopodia formation and extracellular matrix degradation, pointing to an inhibitory role in invasion in this context. Mechanistic analysis revealed a PKCα-mediated negative feedback loop that dampened PI3K activity. In keeping with these findings, the PI3K-high/PKCα-low signaling state was found to predict the most invasive phenotype in HNSCC (Hoshino et al., 2012).

A role of PKCα in promoting metastasis appears at odds with its tumor suppressive properties in multiple cancer types and the fact that its expression is commonly lost in advanced metastatic disease (Sections 2 and 5). Similarly, the PKCα target DLG1 can act as a tumor suppressor and is frequently lost in invasive carcinomas (Marziali et al., 2019). Thus, a positive contribution of PKCα to invasion and metastasis is likely limited to tumor types where the kinase does not have a tumor suppressive role, or to tumors where downstream tumor suppressive signaling has been inactivated. Notably, RhoGTPases that are downstream of PKCα in migration signaling are commonly overexpressed in cancer (Jansen et al., 2018), indicating that tumors have alternate mechanisms for upregulation of these pathways in the absence of PKCα activity.

4. The role of PKCα in cell survival and drug resistance

Multiple studies point to a protective role of PKCα in the response of tumor cells to chemotherapy. The ability of PKCα overexpression to confer drug resistance has been observed with a variety of chemotherapeutic agents in a broad range of cancer types. For example, increased levels of the kinase protected acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) cells from the antitumor effects of etoposide and cytosine arabinoside (araC) (Jiffar et al., 2004; Ruvolo et al., 1998), RT4 bladder cancer cells from the effects of doxorubicin (Kong et al., 2005), and C6 glioma cells from tamoxifen treatment (Tian et al., 2009). Conversely, reducing PKCα expression using antisense RNA, ribozyme or RNAi technology sensitized cancer cells to a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including vincristine and prednisone in ALL (Lei et al., 2016), cisplatin and taxol in ovarian cancer (Zhao et al., 2012), erlotinib in lung cancer (Abera and Kazanietz, 2015), mitomycin-C and 5-fluorouracil in MKN-45 gastric cancer (Jiang et al., 2004), and cisplatin in prostate (Villar et al., 2009) and cervical cancer cells (Mohanty et al., 2005). The clinical relevance of these findings is highlighted by evidence that PKCα expression correlates with resistance to antiestrogen therapy in breast cancer patients (Assender et al., 2007).

A major mechanism underlying PKCα-mediated drug resistance appears to involve regulation of apoptosis, particularly through BCL2 family proteins. Even in the absence of cytotoxic treatments, reduced expression of PKCα leads to an increase in spontaneous apoptosis in some cell lines, including COS cells (Whelan and Parker, 1998), HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Zhu, B.H. et al., 2005), T98G and U87 glioblastoma cells (Leirdal and Sioud, 1999; Mandil et al., 2001), and MKN-45 gastric cancer cells (Jiang et al., 2004). PKCα can phosphorylate BCL2 on Ser70 in vitro (Ruvolo et al., 1998), a modification that has been linked to enhanced anti-apoptotic activity (Ruvolo et al., 2001). In cells, PKCα can associate with mitochondrial membranes (Ruvolo et al., 1998; Wang, W.L. et al., 2007) and the enzyme induces phosphorylation of BLC2 in murine fibroblasts (Wang, W.L. et al., 2007), HL60 promyelocytic leukemia cells (Jiffar et al., 2004), REH pre-B ALL cells (Ruvolo et al., 1998), LNCaP prostate cancer cells (Villar et al., 2009), and U87MG glioblastoma cells (Joniova et al., 2014). In addition to direct phosphorylation, PKCα-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial PP2A appears to contribute to enhanced BCL2 phosphorylation and activity (Jiffar et al., 2004; Ruvolo et al., 1998). PKCα also supports the expression of BCL-xL in U87MG and T98G glioblastoma cells (Leirdal and Sioud, 1999) and in rat hepatic epithelial cells (Hsieh et al., 2003) (but not keratinocytes (Jost et al., 2001)), indicating that the kinase affects multiple BCL2 family members. Mitochondrial PKCα can also act through modulation of pro-apoptotic BH3 proteins since PKCα-mediated inhibition of BAD, rather than activation of BCL2, is involved in blocking mitochondrial permeability-transition (MPT)-dependent necrosis induced by peroxynitrite in U937 lymphoma cells (Cerioni et al., 2006). Additional mechanisms that have been associated with the anti-apoptotic effects of PKCα include downregulation of the apoptosis mediators FEM1b and Apaf-1 in Rack1-overexpressing Jurkat and CCRF-CEM T-cell ALL cells (Lei et al., 2016), induction of nuclear translocation of NFκB in T24 and 5637 bladder cancer cells (Zheng et al., 2017), cytoplasmic localization of p53 in M21 melanoma cells (Smith et al., 2012), and upregulation of Dicer in T24 and 5637 bladder cancer cells (Jiang et al., 2015).

Although less common, PKCα can also have a pro-apoptotic role in cancer. For example, in renal tubular cells, the cells of origin for renal clear cell carcinoma (Santiago et al., 2006), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) activate PKCα, in association with downregulation of BCL2 and activation of caspase-3. In hormone-dependent LNCaP cells, PMA leads to prolonged association of PKCα with non-nuclear membranes and induction of apoptosis (Powell et al., 1996) and PKCα mediates apoptosis induced by DAG-lactones (Garcia-Bermejo et al., 2002). Interestingly, the pro-apoptotic effects of PKCα in prostate cancer appear to be cell-type specific since ribozyme-mediated knockdown of PKCα sensitizes hormone-independent DU145 cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Orlandi et al., 2003).

Multiple studies have implicated PKCα in drug resistance through regulation of P-glycoprotein/MDR1 (ABCB1) and related ATP binding cassette (ABC) efflux pumps (Mayati et al., 2017). A major consideration in interpreting these studies is that many have relied on the use of the classical PKCα inhibitor Gö6976 to attribute the effects to PKC α. Gö6976, and general PKC inhibitors such as bisindolylmaleimides, are inhibitors of ABC pumps (Budworth et al., 1996; Robey et al., 2007), complicating interpretation of the findings. Nonetheless, it would appear that PKCα can reduce cellular drug accumulation by enhancing the activity of efflux pumps. Serines 661, 667 and 671 within the linker region of P-glycoprotein are phosphorylated by PKCs both in vitro and in cells (Chambers, 1998; Idriss et al., 2000), with Ser671 identified as a PKCα target (Ahmad et al., 1994). While mutational analysis has revealed that phosphorylation of serines 661, 667 and 671 is not necessary for P-glycoprotein to confer multidrug resistance (Germann et al., 1996; Goodfellow et al., 1996), mutation of these sites to alanine negatively impacts the interaction of P-glycoprotein with verapamil, vinblastine and rhodamine 123 (Szabo et al., 1997), and alanine mutation of Ser671 abolished the ability of PKCα to enhance verapamil-induced ATPase activity of P-glycoprotein (Ahmad et al., 1994). In addition to regulation of P-glycoprotein activity, PKCα also appears to regulate its expression, likely through modulation of its transcription. PKCα overexpression upregulates P-glycoprotein in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and increases ABCB1 promoter activity (Gill et al., 2001). Conversely, the increased sensitivity of OV1228 ovarian cancer cells upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of PKCα is linked to downregulation of P-glycoprotein at both the mRNA and protein levels (Zhao et al., 2012). PKCα likely affects other ABC proteins since it can phosphorylate MRP2 (ABCC2) and cooperates with PKA to modulate its internalization in rat liver cells (Crocenzi et al., 2008; Wimmer et al., 2008). The ability of PKCα to phosphorylate RLIP76 (Singhal et al., 2005), a multifunctional ATP-dependent non-ABC transporter (Vatsyayan et al., 2010), and increase its ability to transport doxorubicin in lung cancer cells (Singhal et al., 2005), indicates that PKCα can affect drug resistance through multiple types of efflux pumps.

5. PKCα in tumors

5.1. PKCα mutations in cancer