Abstract

Background: We examined the effects of exercise training on resting metabolic rate (RMR), and whether changes in body composition are associated with changes in RMR in adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Methods: One hundred forty adolescents (12–18 years, BMI ≥85th percentile) participated in randomized exercise trials (3–6 months) at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (18 control, 51 aerobic, 50 resistance, and 21 combined aerobic and resistance exercise). All participants had RMR assessments by indirect calorimetry after a 10–12 hour overnight fast, and body composition by magnetic resonance imaging and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Results: There were no significant changes in RMR (kcal/day) between exercise groups vs. controls (p > 0.05). All exercise groups decreased visceral fat (−0.2 ± 0.02 kg; p < 0.05) compared to control. Increases in fat-free mass (FFM) were only seen in the combined group (2.3 ± 0.4 kg; p < 0.05), whereas increases in skeletal muscle mass were observed in both resistance (1.2 ± 0.2 kg; p < 0.05) and combined (1.5 ± 0.3 kg; p < 0.05) groups vs. control. Change in FFM, but not fat mass (FM), visceral fat, or skeletal muscle mass (p > 0.05), was a significant determinant of changes in RMR, independent of exercise modality (p = 0.04).

Conclusion: Although exercise modality was not associated with changes in RMR, change in FFM, but not skeletal muscle or FM, was a significant correlate of changes in RMR in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Clinicaltrials.gov registration numbers: NCT00739180, NCT01323088, NCT01938950.

Keywords: exercise type, fat-free mass, resting metabolic rate, skeletal muscle mass

Introduction

Resting metabolic rate (RMR) is the largest component of total daily energy expenditure representing the energy necessary to sustain functions of the body at rest.1 It is known that fat-free mass (FFM) is a strong predictor of RMR in both adults and adolescents.2–4 As such, interventions associated with reductions in FFM, such as diet-induced weight loss, are also shown to be associated with decreases in RMR.5–7 Thus, changes in RMR associated with weight loss may potentially have important implications in long-term weight management.

Whether exercise-induced weight loss is associated with reductions in RMR is of particular interest given that it is recommended that greater physical activity and exercise should be incorporated into weight management interventions.8,9 Previous exercise studies demonstrate that adults who participated in resistance exercise training generally had an increase in FFM and RMR when body weight is maintained,10 whereas RMR is conserved when weight is lost.11 The relationship between aerobic exercise and RMR, however, is inconclusive and may depend on the amount of weight and/or FFM loss.12–15 In the limited literature on adolescents, Treuth et al.16 report similarly large increases in RMR (380 kcal/day vs. 410 kcal/day) and FFM (2.1 kg vs. 1.9 kg) in girls with obesity with resistance training. Further, Alberga et al.17 report no significant changes in RMR despite significant increases in FFM after 6 months of aerobic and/or resistance exercise training. However, the intervention also included mild caloric restriction (250 kcal deficit/day), which would theoretically lower RMR independent of FFM. However, neither of these studies specifically examined the association between changes in skeletal muscle and RMR which may be more relevant when examining exercise-induced changes. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training without caloric restriction on the change in RMR, and to examine whether changes in body composition, such as fat mass (FM), visceral fat, FFM, and skeletal muscle mass, are associated with changes in RMR in adolescents with overweight and obesity. We hypothesize that changes in skeletal muscle will be more strongly associated with changes in RMR than measures of FFM with aerobic and/or resistance exercise.

Methods

Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of our previously published randomized trials of aerobic, resistance, and combined training for 3–6 months (Clinicaltrials.gov registration numbers: NCT00739180, NCT01323088, and NCT01938950) conducted between 2007 and 2017 at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh. The primary objectives of these trials were to examine the effects of exercise modalities on the changes in body composition, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescents with overweight and obesity,18–20 which differs from the current study questions. The present study examined the effects of exercise modalities on the changes in RMR and the associations between body composition change and RMR change.

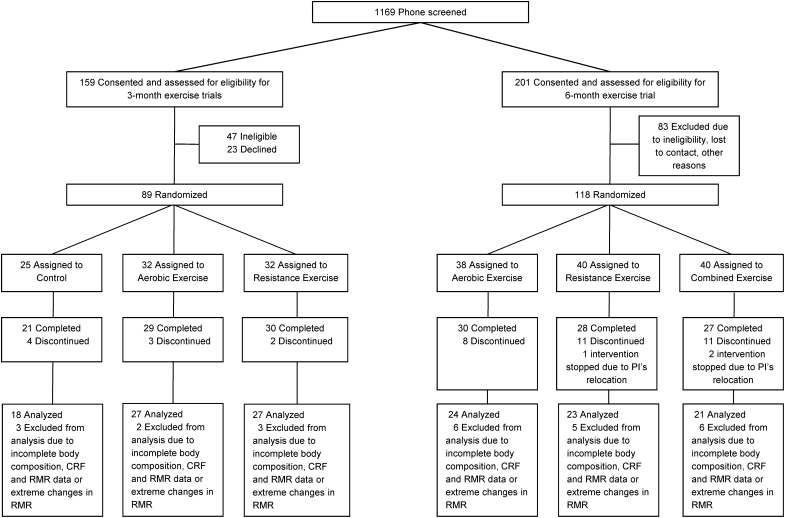

One hundred forty adolescents with overweight and obesity (12–18 years, BMI ≥85th percentile), who had complete baseline and postintervention (51 aerobic, 50 resistance, 21 combined aerobic and resistance exercise groups, and 18 no exercise control group) body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and RMR measurements were included in the current analyses. In brief, 72 adolescents (38 boys and 34 girls) from the two 3-month randomized trials (control, aerobic, or resistance group)18,19 and 68 adolescents (21 boys and 47 girls) from the 6-month randomized trial (aerobic, resistance, or a combination of aerobic and resistance group)20 were included in this study (Fig. 1). Three individuals with extreme changes in RMR [>800 kcal/day (n = 2) or <−800 kcal/day (n = 1)] were excluded. Final study sample included 85% (140/165) of participants who completed the exercise trials. Participant and parental consents were obtained before participation in the intervention trials. These trials were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh (PRO07010011 and PRO12080401) and the research procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval to conduct a secondary analysis was obtained from York University's Research Ethics Board (#e2019–52).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram. CRF, cardiorespiratory fitness; RMR, resting metabolic rate.

Interventions

Details of these intervention studies have been reported previously.18–20 Participants in the aerobic exercise group exercised on treadmills and/or elliptical at 50%–75% of VO2peak, 3 sessions/week (60 minutes/session), for 3–6 months. Participants in the resistance group exercised on weight machines and performed a series of 10 whole-body resistance exercises, 2 sets, 8–12 repetitions in the 3-month study,18,19 and 2 sets, 12–15 repetitions in the 6-month study,20 three sessions/week (60 minutes/session), for 3–6 months. Participants in the combined aerobic and resistance exercise group in the 6-month study,20 performed 30 minutes of aerobic exercise on a treadmill or elliptical at a moderate intensity (50%–65% of VO2peak) and performed a series of 10 whole-body resistance exercises (1 set, 12–15 repetitions), 3 sessions/week (60 minutes/session). Participants in the control group in the 3-month trial18,19 did not partake in any exercise interventions. During the intervention period, participants in all three trials,18–20 including controls, were asked to follow a healthy weight maintenance diet (55%–60% carbohydrate, 15%–20% protein, and 25%–30% fat) to examine the independent effects of exercise on the changes in body composition and obesity-related risk factors.

Resting Metabolic Rate

All participants were admitted to the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh on the previous day, for testing in the following morning. After a 10–12-hour overnight fast, RMR was measured between 09:00 and 09:30 using a ventilated hood system (Parvo Medics, Salt Lake City, UT). Participants were asked not to move or fidget during the duration of RMR testing. Postintervention measurements were taken 72 hours after the last exercise session. RMR change is defined as the difference between baseline and postintervention RMR measurements.

Anthropometrics and Body Composition

Body weight was measured using a digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg, and height was measured using a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. FM and FFM was measured using the Lunar iDXA (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI). Visceral fat and skeletal muscle were assessed by obtaining whole-body magnetic resonance imaging data with a 3.0 Tesla magnet (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) as detailed previously.18–20 Nonskeletal muscle FFM was calculated as the total FFM minus skeletal muscle mass.

Statistical Analysis

Participant baseline age, sex, body weight, ethnicity, Tanner stage, BMI, RMR, and body composition variables were stratified by exercise modality and presented as means with standard deviations for continuous variables or frequency for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test was used to determine baseline differences in RMR and body composition variables between exercise groups in comparison to the control group.

Linear regression models were used to analyze the differences between exercise modality on the changes in RMR, body weight, FM, visceral fat, FFM, skeletal muscle, and nonskeletal muscle FFM mass. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Tanner stage, and respective baseline values of RMR, body weight, FM, visceral fat, FFM, skeletal muscle, and nonskeletal muscle FFM. Models were examined for points of influence with outliers excluded. Differences in RMR, body weight, and body composition changes by exercise modality were presented as least squared means. Linear regression models were also used to examine the individual relationship between changes over the intervention in RMR with changes in FM, visceral fat, FFM, skeletal muscle, and nonskeletal muscle FFM, with individuals in the control group excluded from the analyses. All models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Tanner stage, exercise modality, and baseline RMR. p-Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the statistical program SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Participant baseline characteristics stratified by exercise modality are presented in Table 1. No significant differences in baseline FM, visceral fat, FFM, skeletal muscle, or nonskeletal muscle FFM were observed among the exercise groups compared to control (p > 0.05). In contrast, those in the combined group had lower absolute RMR (kcal/day) at baseline compared to the control group (p < 0.05). At baseline, RMR (kcal/day) was significantly correlated with FFM (r = 0.69, p < 0.01), skeletal muscle mass (r = 0.66, p < 0.01), nonskeletal muscle FFM (r = 0.62, p < 0.01), visceral fat (r = 0.43, p < 0.01), and FM (r = 0.41, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline Subject Characteristics

| Control | Aerobic exercise | Resistance exercise | Combined exercise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 18 | 51 | 50 | 21 |

| Male/female, n | 11/7 | 20/31 | 21/29 | 7/14 |

| Ethnicity, black/white/others | 9/8/1 | 27/22/2 | 29/20/1 | 10/8/3 |

| Tanner stage, II–III/IV–V | 2/16 | 5/46 | 8/42 | 1/20 |

| Age, years | 14.6 ± 1.7 | 14.8 ± 1.7 | 14.5 ± 1.6 | 14.6 ± 1.7 |

| Height, cm | 167 ± 7 | 167 ± 8 | 165 ± 8 | 168 ± 9 |

| Weight, kg | 99.0 ± 16.4 | 95.2 ± 17.9 | 92.8 ± 12.9 | 90.2 ± 14.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35.4 ± 5.5 | 33.9 ± 4.5 | 34.1 ± 3.4 | 31.7 ± 3.4a |

| BMI, percentile | 98.7 ± 1.3 | 98.2 ± 1.7 | 98.6 ± 1.0 | 97.5 ± 1.8 |

| RMR, kcal/day | 2034 ± 293 | 1867 ± 336 | 1841 ± 329 | 1723 ± 296a |

| DXA | ||||

| FM, kg | 43.0 ± 11.2 | 39.3 ± 9.7 | 39.8 ± 8.2 | 36.4 ± 9.0 |

| FFM, kg | 55.4 ± 8.8 | 55.4 ± 10.2 | 52.3 ± 7.3 | 53.5 ± 8.8 |

| MRI | ||||

| Visceral fat, kg | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.6 |

| Skeletal muscle, kg | 25.5 ± 5.0 | 26.0 ± 6.0 | 24.3 ± 4.2 | 25.0 ± 4.7 |

| Non-SM FFM, kg | 29.9 ± 4.2 | 29.4 ± 4.7 | 28.0 ± 3.9 | 28.5 ± 4.8 |

Data are means ± SD or frequency (percent %).

DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RMR, resting metabolic rate; SM, skeletal muscle.

p < 0.05 compared to control group.

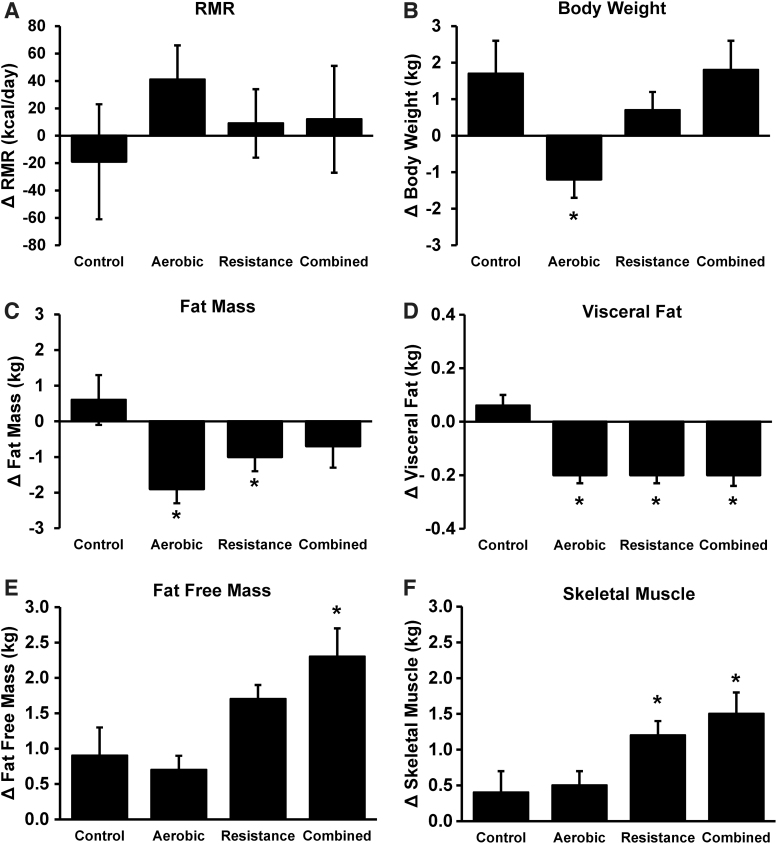

Mean changes in RMR, body weight, and body composition variables adjusted for its respective baseline measurements, age, sex, ethnicity, and Tanner stage are shown in Figure 2. Changes in RMR (Fig. 2A) were not significantly different between exercise modalities (ΔRMRAT = 41 kcal/day; ΔRMRRT = 9 kcal/day; ΔRMRCombined = 12 kcal/day) and control (ΔRMR = −19 kcal/day). Only the aerobic group (−1.2 ± 0.5 kg) had significant decreases in body weight (Fig. 2B) compared to control (1.7 ± 0.9 kg), whereas significant reductions in FM (Fig. 2C) were observed in aerobic (−1.9 ± 0.4 kg) and resistance groups (−1.0 ± 0.4 kg) vs. control (0.6 ± 0.7 kg). All exercise groups also had a reduction (p < 0.05) in visceral fat (Fig. 2D) vs. control. Significant increases in FFM (Fig. 2E) were seen only in the combined group (2.3 ± 0.4 kg) vs. control (0.9 ± 0.4 kg), whereas increases (p < 0.05) in skeletal muscle (Fig. 2F) were seen in both the resistance (1.2 ± 0.2 kg) and combined (1.5 ± 0.3 kg) groups when compared to control (0.4 ± 0.3 kg). For nonskeletal muscle FFM, there were no significant group differences from control (control: 0.6 ± 0.4 kg; aerobic: 0.2 ± 0.2 kg; resistance: 0.4 ± 0.2 kg; and combined: 0.8 ± 0.3 kg; p = 0.49).

Figure 2.

Changes (mean ± SE) in RMR (A), body weight (B), fat mass (C), visceral fat (D), fat-free mass (E), and skeletal muscle (F) in control, aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise groups. All analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Tanner stage, and respective baseline values. *p < 0.05 compared to control group.

The relationship between changes in body composition on RMR change is presented in Table 2, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Tanner stage, exercise modality, and baseline RMR in the exercise groups. The type of exercise modality did not have a significant effect on the associations between body composition variables and RMR change (i.e., exercise modality × body composition variable interaction, p > 0.05). Changes in FFM and nonskeletal muscle FFM, but not FM, visceral fat, FFM, or skeletal muscle mass, were significantly (p = 0.04 for both) associated with RMR change.

Table 2.

The Relationship between the Changes in Body Composition and Resting Metabolic Rate in the Exercise Groups (n = 122)

| Model R2 | Partial R2 | β (SE) for Δ RMR | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in body composition | ||||

| FM, kg | 0.18 | 0.001 | 7.4 (6.0) | 0.22 |

| Visceral fat, kg | 0.17 | 0.005 | 63.4 (85.6) | 0.46 |

| FFM, kg | 0.20 | 0.046 | 20.5 (10.0) | 0.04 |

| Skeletal muscle, kg | 0.17 | 0.001 | 5.3 (11.6) | 0.64 |

| Non-SM FFM, kg | 0.22 | 0.053 | 19.6 (9.2) | 0.04 |

All models adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, Tanner stage, exercise modality, and baseline RMR β values for the change in RMR per kg change in body composition.

SM, skeletal muscle.

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of different exercise modalities without caloric restriction on the changes in RMR and explored the relationships between body composition and RMR changes in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Our findings demonstrated that regular exercise, regardless of modality, did not result in significant changes in RMR, and that the change in FFM and specifically nonskeletal muscle FFM, but not FM, visceral fat, or skeletal muscle mass, were significant predictors of RMR change.

Physical activity and exercise has been recommended as an important adjunct to weight management therapies.9,21 However, it is unclear whether exercise training is associated with changes in RMR in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Previous studies15,17,22 have shown that aerobic exercise is not associated with changes in RMR. This is not surprising given that aerobic exercise generally is not associated with changes in FFM or skeletal muscle mass.23 Although aerobic exercise was the only exercise training group associated with both weight and fat loss, RMR was not significantly reduced. It may be attributed to the low metabolic activity in FM24,25 and that aerobic exercise was not associated with reductions in FFM in the present study. This suggests that exercise-induced weight loss may not be associated with reductions in RMR that are often reported with dietary weight loss in children and adults.5–7

Changes in RMR are more commonly associated with resistance training. Treuth et al.16 report an increase in RMR (380 kcal/day) and FFM (2.1 kg) after 5 months of resistance training in prepubertal girls (7–10 years old) with obesity that was similar to what was observed in the control group [RMR (410 kcal/day) and FFM (1.9 kg)]. Similarly, the HEARTY trial,17 which to our knowledge is the only randomized control trial to compare the effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training with dietary restrictions (−250 kcal/day) on RMR change in postpubertal adolescents (14–18 years old) with obesity showed that regardless of exercise modality, 6 months of exercise training was not associated with changes in RMR. In that study,17 although FFM increased in all exercise groups, it was not significantly different between exercise or control groups. Perhaps the absence of group differences in FFM change and the low participant adherence (∼60%) to their respective exercise programs or mild caloric restriction (250 kcal/day) may, in part, explain why RMR changes were not observed in that study. The present study examined the independent effects of different exercise modalities without dietary restrictions on RMR change in adolescents with overweight and obesity and had higher exercise intervention adherence (≥90%), and demonstrate that only the combination of resistance and aerobic exercise was associated with improvements in FFM, while all exercise groups were associated with reductions in visceral fat. Nevertheless, there were no differences in RMR with any of the exercise modalities. Thus, moderate resistance may be associated with significant increases in FFM and skeletal muscle beyond what may be expected with normal growth in adolescents, but these differences may not be enough to significantly increase RMR.

It is well supported in the literature that FFM2–4 and specifically skeletal muscle26,27 is a primary determinant of RMR. Previous studies10,16,28 that report increases in absolute RMR generally also report an increase in FFM, further supporting the importance of FFM change on RMR change. Similarly, we demonstrate that changes in FFM are associated with RMR change in adolescents with overweight and obesity. It has been proposed that resistance exercise is associated with improvements in RMR via the increase of FFM. Several studies examining the effects of resistance exercise on RMR in weight-stable adults with10 or without obesity22 reported an increase in absolute RMR after resistance training, which has been attributed to increases in FFM and more specifically skeletal muscle. In this study, we observed that FFM, but not skeletal muscle is associated with changes in RMR. In fact, changes in FFM and specifically nonskeletal muscle FFM were the only body composition variables examined that had a significant association with changes in RMR. Within FFM, skeletal muscle mass is a major component and also includes depots such as organs with higher metabolic activity than muscle per unit mass and some tissues that have lower metabolic activity (i.e., bone, connective tissue, etc.). In adults, nonskeletal muscle FFM is relatively constant, so exercise-induced changes in skeletal muscle on RMR may be more easily observed, whereas children and adolescents are undergoing growth and development where both skeletal muscle and other FFM depots, namely metabolically active organs, are growing in size.29 Changes in other metabolically active FFM may obscure the association between RMR and skeletal muscle, particularly if they do not increase at the same rates.29 Children and adolescents generally have less absolute and relative skeletal muscle mass than adults, such that the other metabolically active FFM depots may contribute a greater proportion to FFM,30,31 and accordingly RMR. However, there may also be other factors yet to be determined that independently raise energy expenditure beyond FFM alone.31 Thus in adolescents, changes in FFM may be more closely associated with changes in RMR than skeletal muscle. This emphasizes the point that observations in adults may or may not apply to adolescents.

However, despite the relationship between FFM change and RMR change being statistically significant, it is unclear if the magnitude of the association is clinically meaningful as it would require large increases in FFM to see noticeable improvements in RMR. For example, we observed that an increase in 1 kg of FFM or nonskeletal muscle FFM was associated with a ∼20 kcal/day RMR change. With 3 to 6 months of exercise training, there was only a 0.7 to 2.3 kg mean FFM increase from baseline observed in adolescents with overweight and obesity, which translates to an increase in absolute RMR of ∼9 to 41 kcal/day (0.5%–2.2% of baseline RMR). That said that the average 1–2 pound yearly weight gain observed in US adults could be attributed to an excess of only 15 kcal per day.32 Thus, even small differences in RMR with exercise could be associated with meaningful longer term obesity consequences, particularly when examined in the larger context of other factors that may each have a small effect that together may result in successful long-term obesity management (i.e., nonexercise thermogenesis, appetite, emotional eating, differences in exercise efficiency, and so on).

There are strengths and limitations in this study that merit discussion. Findings from the present study contribute to the limited literature on the effects of exercise on RMR change in adolescents with overweight and obesity. This study includes participants with high adherence (≥90%) to their respective training programs. RMR measurements were also taken 72 hours after the last bout of exercise to control for the acute effects of exercise and after an overnight stay at the hospital. Nevertheless, differences in fidgeting, emotional state, or day-to-day variation may have impaired our ability to observe true changes in RMR, which may have biased our observation toward the null. Limitations of the study include the utilization of indirect calorimetry with a ventilated hood instead of whole-room indirect calorimeter.33 The control group was also limited to participants in the 3-month intervention. Due to small sample size, we were unable to examine the effects of exercise modalities on RMR change by pubertal stages, sex, and race.

In conclusion, we found that exercise training without caloric restriction, regardless of modality, did not result in significant improvements in RMR in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Further, change in FFM, but not skeletal muscle or FM, was a significant correlate of RMR change.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants and their parents who participated in this study and the nursing staff of the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center at UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh for their outstanding care of the participants. The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to declare.

Funding Information

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Numbers 5R01HL114857, 1R21DK083654-01A1), American Diabetes Association (7-08-JF-27), and UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (Cochrane-Weber Foundation and Renziehausen Fund) to Lee during her tenure at the University of Pittsburgh, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005) to the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Lam YY, Ravussin E. Analysis of energy metabolism in humans: A review of methodologies. Mol Metab 2016;5:1057–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Later W, et al. Functional body composition: Insights into the regulation of energy metabolism and some clinical applications. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63:1045–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molnár D, Schutz Y. The effect of obesity, age, puberty and gender on resting metabolic rate in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 1997;156:376–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnstone AM, Murison SD, Duncan JS, et al. Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiortsis DN, Durack I, Turpin G. Effects of a low-calorie diet on resting metabolic rate and serum tri- iodothyronine levels in obese children. Eur J Pediatr 1999;158:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med 1995;332:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Menozzi R, Bondi M, Baldini A, et al. Resting metabolic rate, fat-free mass and catecholamine excretion during weight loss in female obese patients. Br J Nutr 2000;84:515–520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bray GA, Frühbeck G, Ryan DH, et al. Management of obesity. Lancet 2016;387:1947–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the obesity society. Circulation 2014;129:S102–S138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Byrne HK, Wilmore JH. The effects of a 20-week exercise training program on resting metabolic rate in previously sedentary, moderately obese women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2001;11:15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller T, Mull S, Aragon AA, et al. Resistance training combined with diet decreases body fat while preserving lean mass independent of resting metabolic rate: A randomized trial. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018;28:46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee M-G, Sedlock DA, Flynn MG, et al. Resting metabolic rate after endurance exercise training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:1444–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Potteiger JA, Kirk EP, Jacobsen DJ, et al. Changes in resting metabolic rate and substrate oxidation after 16 months of exercise training in overweight adults. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2008;18:79–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunter GR, Byrne NM, Sirikul B, et al. Resistance training conserves fat-free mass and resting energy expenditure following weight loss. Obesity 2008;16:1045–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Santa-Clara H, Szymanski L, Ordille T, et al. Effects of exercise training on resting metabolic rate in postmenopausal African American and Caucasian women. Metab Clin Exp 2006;55:1358–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Treuth MS, Hunter GR, Pichon C, et al. Fitness and energy expenditure after strength training in obese prepubertal girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:1130–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alberga AS, Prud'Homme D, Sigal RJ, et al. Does exercise training affect resting metabolic rate in adolescents with obesity? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016;42:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S, Bacha F, Hannon T, et al. Effects of aerobic versus resistance exercise without caloric restriction on abdominal fat, intrahepatic lipid, and insulin sensitivity in obese adolescent boys: A randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes 2012;61:2787–2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S, Deldin AR, White D, et al. Aerobic exercise but not resistance exercise reduces intrahepatic lipid content and visceral fat and improves insulin sensitivity in obese adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013;305:E1222–E1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee S, Libman I, Hughan K, et al. Effects of exercise modality on insulin resistance and ectopic fat in adolescents with overweight and obesity: A randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr 2019;206:91–98.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spear BA, Barlow SE, Ervin C, et al. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics 2007;20 Suppl 4:S254–S288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poehlman ET, Denino WF, Beckett T, et al. Effects of endurance and resistance training on total daily energy expenditure in young women: A controlled randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:1004–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pollock ML, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: Benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: An advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation 2000;101:828–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang ZM, Ying Z, Bosy-Westphal A, et al. Specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues across adulthood: Evaluation by mechanistic model of resting energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1369–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elia M. Organ and tissue contribution to metabolic rate. In: Kinney J, Tucker H (eds), Energy Metabolism: Tissue Determinants and Cellular Corollaries. Raven Press: New York, 1992, pp. 61–80 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zurlo F, Larson K, Bogardus C, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolism is a major determinant of resting energy expenditure. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1423–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dériaz O, Fournier G, Tremblay A, et al. Lean-body-mass composition and resting energy expenditure before and after long-term overfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;56:840–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aristizabal JC, Freidenreich DJ, Volk BM, et al. Effect of resistance training on resting metabolic rate and its estimation by a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry metabolic map. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015;69:831–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanner JM. Growth and maturation during adolescence. Nutr Rev 1981;39:43–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gallagher D, Elia M.. Body composition, organ mass and resting energy expenditure. In: Heymsfield SB, Lohman TG, Wang Z, et al. (eds), Human Body Composition, vol. 918. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2005, pp. 219–239 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu A, Heshka S, Janumala I, et al. Larger mass of high-metabolic-rate organs does not explain higher resting energy expenditure in children. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:1506–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, et al. Obesity and the environment: Where do we go from here? Science 2003;299:853–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rising R, Whyte K, Albu J, et al. Evaluation of a new whole room indirect calorimeter specific for measurement of resting metabolic rate. Nutr Metab 2015;12:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]