Abstract

A synthetic strategy for the 2-phospha-1,3-butadiene derivatives [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)] (3a) and [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)] (3b) (IPr = C{(NDipp)CH}2, Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3; cAACMe = C{(NDipp)CMe2CH2CMe2}; cAACCy = C{(NDipp)CMe2CH2C(Cy)}, Cy = cyclohexyl) containing a C C–P C framework has been established. Compounds 3a and 3b have a remarkably small HOMO–LUMO energy gap (3a: 5.09; 3b: 5.05 eV) with a very high-lying HOMO (−4.95 eV for each). Consequently, 3a and 3b readily undergo one-electron oxidation with the mild oxidizing agent GaCl3 to afford radical cations [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACR)]GaCl4 (R = Me 4a, Cy 4b) as crystalline solids. The main UV-vis absorption band for 4a and 4b is red-shifted with respect to that of 3a and 3b, which is associated with the SOMO related transitions. The EPR spectra of compounds 4a and 4b each exhibit a doublet due to coupling of the unpaired electron with the 31P nucleus. Further one-electron removal from the radical cations 4a and 4b is also feasible with GaCl3, affording the dications [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACR)](GaCl4)2 (R = Me 5a, Cy 5b) as yellow crystals. The molecular structures of compounds 3–5 have been determined by X-ray diffraction and analyzed by DFT calculations.

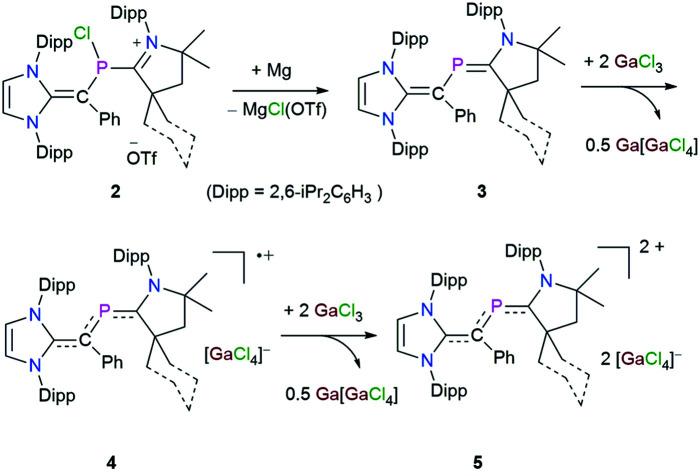

The 2-phospha-1,3-butadiene derivatives 3 are readily accessible by reduction of 2 with Mg. Sequential one-electron oxidation of 3 with GaCl3 leads to the formation of radical cations 4 and dications 5 as crystalline solids.

Introduction

Organic π-conjugated molecules are currently of great academic and significant technological interest due to their intriguing optoelectronic properties.1 In this context, π-conjugated systems featuring heavier main-group elements2 and systems exhibiting a considerable open-shell (radical-type) character3 are particularly attractive as they display promising optical, electronic, and magnetic properties. Among heavier main-group elements, the choice to incorporate phosphorus into π-conjugated systems has been primarily driven by its semblance to the isoelectronic “CR” (R = H, alkyl or aryl group) unit, which is known as a diagonal relationship.4 Moreover, while the calculated P C π-bond strength (43 kcal mol−1) is lower than the C C π-bond of ethene (65 kcal mol−1)5 the conjugative properties of both P C and C C bonds are comparable.6

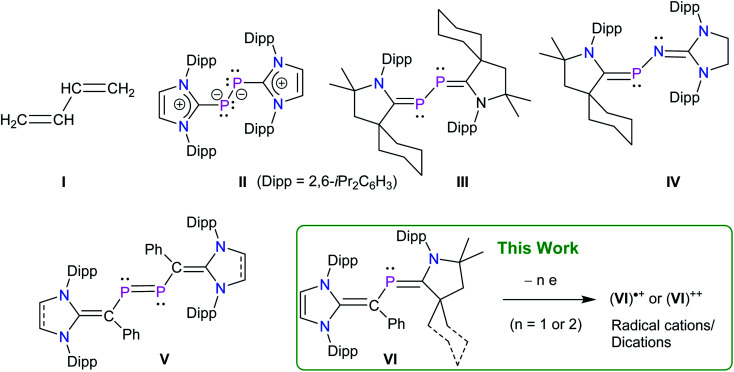

Among stable main-group radicals,7 various neutral,8 cationic,9 as well as anionic10 phosphorus radicals have been also isolated and structurally characterized, however, phosphorus radicals based on a π-conjugated framework remain scarce. 1,3-Butadiene I is the simplest molecule with conjugated π-bonds (Fig. 1) that has also been an important structural motif in phosphorus chemistry.11 Indeed, unsubstituted as well as alkyl substituted phosphorus containing 1,3-butadiene derivatives were already reported by Appel,11b Regitz,11f and Denis,11g however, these compounds are unlikely to afford stable radical compounds on oxidation or reduction. In 2008, Robinson et al. reported a diphosphorus compound II containing a weak π-acceptor N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC).12 Structural and theoretical data suggest that II should be better described as a base-stabilized diphosphinidene with C(NHC)–P and P–P single bonds. Compound III, reported by Bertrand's group in 2010, features a strong π-acceptor cyclic alkyl amino carbene (cAACR) and exhibits short C–P bond lengths, thus it may be regarded as a genuine 2,3-diphospha-1,3-butadiene.13 The same group also reported the 2-phospha-3-azabutadiene IV by an elegant choice of imine and cAAC precursors.9c Remarkably, these electron-rich species readily undergo one-electron oxidation to afford the corresponding radical cations (II)˙+, (III)˙+, and (IV)˙+.9b,9c We recently reported NHC-derived divinyldiphosphenes V14 and isolated the corresponding radicals cations (V)˙+ by one-electron oxidation of V.15 These and other early results16 prompted us to reason that stable 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes VI as well as the corresponding radical cations (VI)˙+ and dications (VI)++ should be synthetically accessible by a rational choice of substrates and reaction conditions.

Fig. 1. 1,3-Butadiene I. Selected examples of phosphorus containing derivatives II–IV and divinyldiphosphene V with singlet carbene frameworks.

Herein, we report the synthesis of 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)] (3a) and [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)] (3b) based on singlet carbene frameworks (IPr = C{(NDipp)CH}2, Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3; cAACMe = C{(NDipp)CMe2CH2CMe2}; cAACCy = C{(NDipp)CMe2CH2C(Cy)}, Cy = cyclohexyl) as crystalline solids. Sequential one-electron oxidation of 3a and 3b leads to the formation of corresponding radical cations [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)](GaCl4) (4a), [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)](GaCl4) (4b) and dications [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)](GaCl4)2 (5a), [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)] (GaCl4)2 (5b) as crystalline solids.

Results and discussion

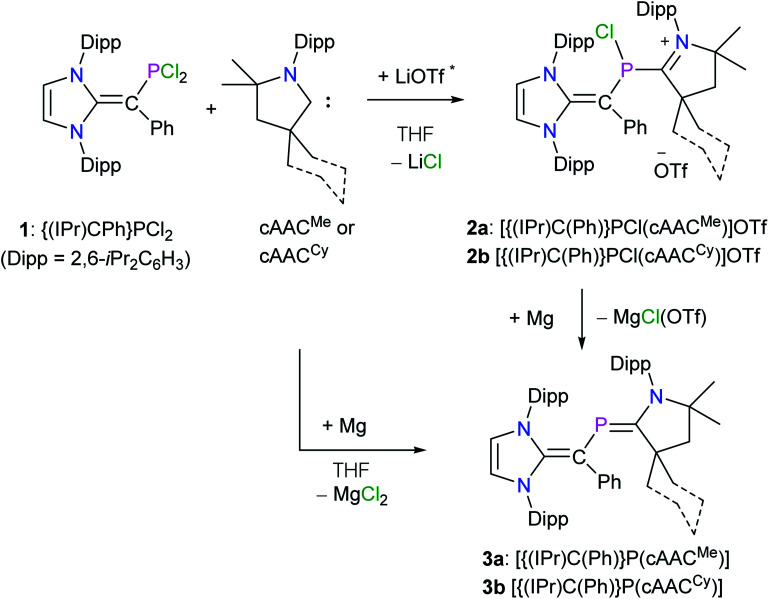

For the synthesis of desired 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes, N-heterocyclic vinyl (NHV)-substituted dichlorophosphine {(IPr)C(Ph)}PCl2 (1)14 and strong π-acceptor cAACR (ref. 17) were chosen as the appropriate precursors (Scheme 1).18 Treatment of a colorless THF solution of 1 with one equivalent of cAACMe or cAACCy immediately resulted in the formation of dark blue solutions (Scheme 1). After workup, the ionic compounds [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(Cl)(cAACR)](OTf) (R = Me 2a, Cy 2b) were isolated as violet crystalline solids. Compounds 2a and 2b are highly air sensitive solids and have been characterized by elemental analysis and NMR spectroscopy. The solid state molecular structure of a typical compound 2a (Fig. S31†) was determined by X-ray diffraction. Reduction of 2a and 2b with magnesium turnings afforded the target compound 3a and 3b, respectively, as orange solids. Interestingly, 3a and 3b are also accessible in a one-pot reaction of 1 and cAACR with magnesium. Both 3a and 3b are soluble in common organic solvents (n-hexane, Et2O, benzene, toluene, THF) and are stable under an inert gas atmosphere.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2-phospha-1,3-butadiene derivatives 3a and 3b. * cAACs were prepared by the deprotonation of their triflate salts with LDA and the side-product LiOTf was not separated.

The 1H NMR spectra of compounds 2a and 2b as well as 3a and 3b show expected resonances for the NHV and cAACR moieties. The 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of 2a and 2b as well as 3a and 3b each is consistent with the 1H NMR resonances and exhibits expected doublets for the phosphorus bound carbon atoms (see the ESI†). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 2a (+100.9 ppm) and 2b (+102.9 ppm) each shows a singlet, which is high-field shifted with respect to that of the 1 (+167 ppm). This is most likely due to the coordination of electron-rich cAACR to the phosphorus atoms in 2a and 2b. The 31P{1H} NMR signal for 3a (+102.5 ppm) and 3b (+108.6 ppm), respectively, appears at a higher field compared to that of IV (+134.0 ppm),9c which is expected because of the electronegativity difference between carbon and nitrogen.

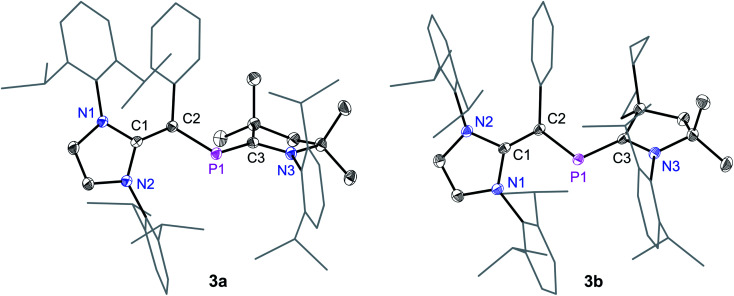

The solid-state molecular structures of 3a and 3b (Fig. 2) adopt a trans-bent geometry along the CNHV–P bond with the C2–P1 bond length of 1.818(1) and 1.820(1) Å, respectively. The C2–P1 bond length is larger compared to that in 1 (1.728(2) Å)14 and 2a (1.751(2) Å), but it is comparable with those of the diphosphenes V (1.785 to 1.797 Å).15 The P1–C3 (3a: 1.735(1); 3b 1.735(1) Å) and C1–C2 (3a: 1.386(1); 3b: 1.384(2) Å) bonds are shorter compared to the same bonds in 2a (1.860(2) and 1.437(2) Å, respectively). The P1–C3 bond lengths of 3a and 3b are nonetheless in line with those of the P C double bonds in III (1.719(7) Å)13 and IV (1.719(2) Å).9c The C1 C2, P1 C3, and P1–C2 bond lengths of 3a and 3b are in line with those of the literature known neutral 2-phospha-1,3-butadiene (Me3SiO)tBuC P–C(SiMe3) C(OSiiPr3)tBu (C C: 1.356(4), P C: 1.702(3), P–C: 1.846(3) Å).19

Fig. 2. Solid-state molecular structures of 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes 3a and 3b. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths and bond angles are given in Table 1.

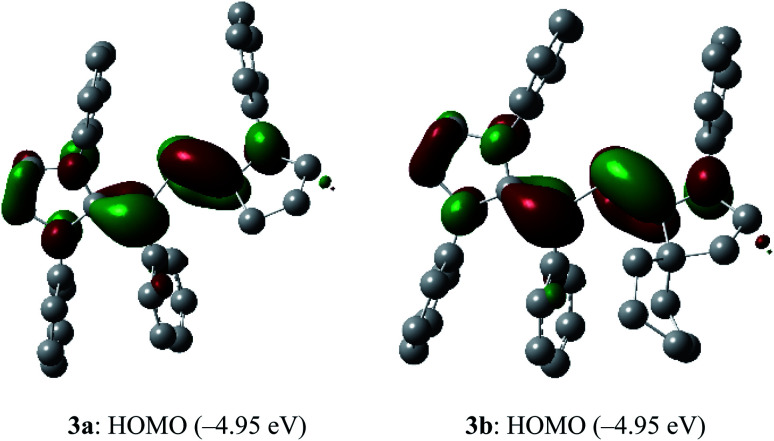

To shed light on the electronic structure of 3a and 3b, we performed DFT calculations at the M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//def2-SVP level of theory. The HOMO of 3a and 3b is a π-type orbital mainly located at the CcAAC P and CIPr CPh bonds (Fig. 3). Remarkably, the HOMO energy of 3a and 3b (−4.95 eV) is quite high and comparable with those of related divinyldiphosphenes V (−4.71 to −5.25 eV),15 indicating the possibility of facile oxidation.

Fig. 3. HOMOs (highest occupied molecular orbitals, isovalue 0.04) of 3a and 3b calculated at M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//def2-SVP level of theory. Hydrogen atoms, methyl as well as iso-propyl groups were omitted for clarity.

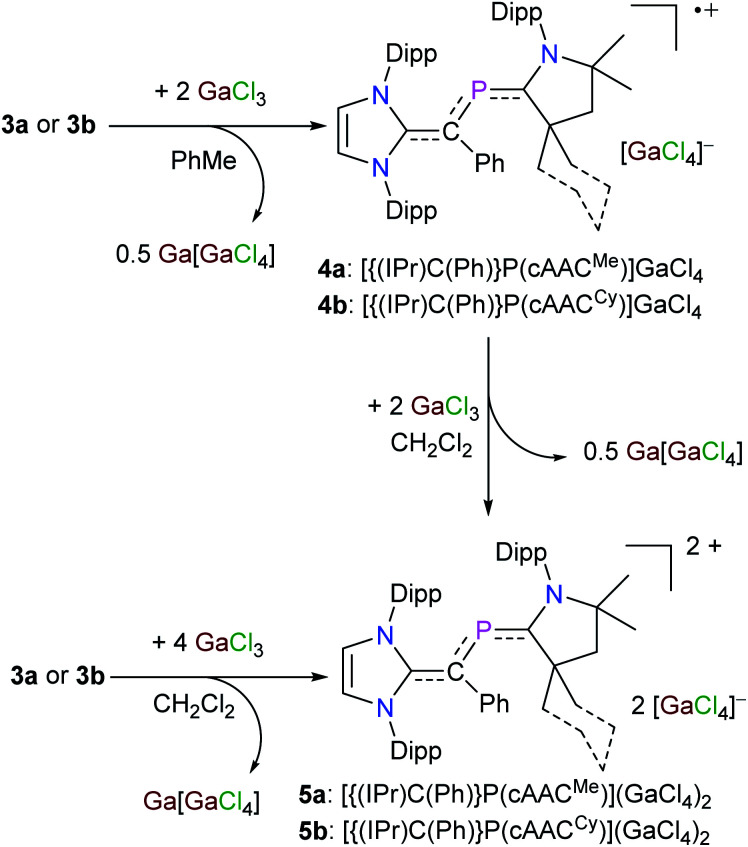

These preliminarily theoretical findings encouraged us to analyze the redox properties of 3a and 3b by electrochemical studies to gain an initial insight into the viability and stability of derived radicals. The cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 3a (Fig. S19†) and 3b (Fig. S20†) show two main redox events in the −2.0 to 1.5 V region. The first reversible wave at E1/2 = −1.06 V for 3a and −1.08 V for 3b may be assigned to the corresponding radical cation, whereas the second quasi-reversible wave at E1/2 = −0.28 V for 3a and −0.24 V for 3b may correspond to the dicationic species. Indeed, treatment of an orange toluene solution of 3a or 3b with GaCl3 immediately led to the precipitation of a violet solid. After workup, the radical cation salts [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)](GaCl4) (4a) and [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)](GaCl4) (4b) were isolated as violet crystals (Scheme 2). GaCl3 acts as oxidizing agent and two molecules of GaCl3 are required for one-electron oxidation.15 Consistent with the CVs (Fig. S19 and S20†), the dication salts [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACMe)](GaCl4)2 (5a) and [{(IPr)C(Ph)}P(cAACCy)](GaCl4)2 (5b) are selectively accessible on one-electron oxidation of 4a and 4b with GaCl3 (Scheme 2). Alternatively, 5a and 5b can also be prepared directly from 3a and 3b with four equivalent of GaCl3, respectively (Scheme 2). Compounds 4a, 4b and 5a, 5b are stable both in solutions as well as in the solid-state under an inert gas atmosphere, but decompose rapidly when exposed to air. The radicals 4a and 4b are NMR silent, while dicationic salts 5a and 5b are diamagnetic and exhibit well resolved 1H and 13C{1H} NMR signals for the NHV and cAACR units. The 31P{1H} NMR signal for the dication salts 5a (+244 ppm) and 5b (+236 ppm) is downfield-shifted with respect to that of the 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes 3a (+102 ppm) and 3b (+108 ppm) but it is in the range expected for phosphaalkenes (200–300 ppm).20

Scheme 2. Sequential one-electron oxidation of 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes 3a and 3b with GaCl3 to the corresponding radical cations 4a and 4b and dications 5a and 5b.

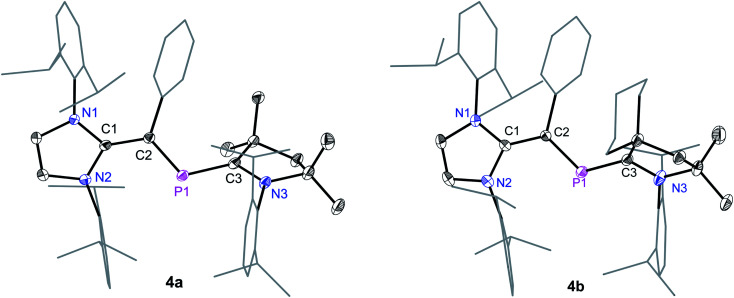

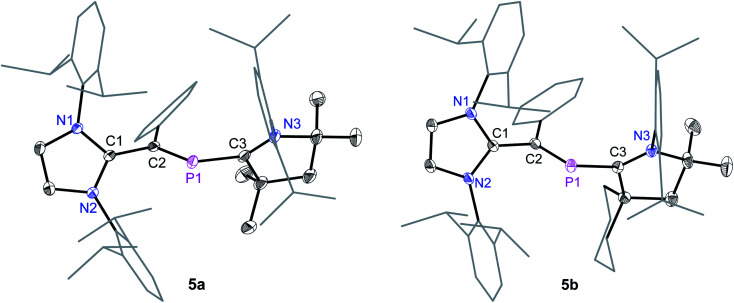

Suitable single crystals for X-ray diffraction were obtained by a slow diffusion of n-hexane into a saturated THF or CH2Cl2 solution of each of radical cations 4a and 4b and dicationic salts 5a and 5b. The solid-state molecular structure of 4a and 4b (Fig. 4) as well as 5a and 5b (Fig. 5) each adopts a trans-bent geometry along the P–CNHV bond and reveals an interesting bond length alteration trend with respect to the precursors 3a and 3b (Table 1). The C2–P1 bond length of 4a (1.758(2) Å) and 4b (1.761(2) Å) is smaller compared to that of the respective 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes 3a (1.818(1) Å) and 3b (1.820(1) Å) but longer with respect to that of the dications 5a (1.692(3) Å) and 5b (1.692(2) Å) Å. The P1–C3 bond, however, steadily stretches on going from neutral to radical cations and to dications: 3a: 1.735(1), 3b: 1.735(1); 4a: 1.785(2), 4b: 1.790(2); 5a: 1.865(2), 5b: 1.853(2) Å. A similar trend in the C1–C2 bond length stretching can also be seen in 3a: 1.386(1), 3b: 1.384(2); 4a: 1.432(2), 4b: 1.433(2); and 5a: 1.479(3), 5b: 1.478(2) Å. In conclusion, the formally C1 C2 and P1 C3 double bonds in 3a and 3b become comparable to Csp2–Csp2 (ca. 1.47 Å) and P–Csp2 (1.85 Å) single bond lengths21 in 5a and 5b, whereas the C2–P1 single bond in 3a and 3b adopts double bond lengths (1.60–1.70 Å) in 5a and 5b as expected for phosphaalkenes.22

Fig. 4. Solid-state molecular structures of radical cation 4a and 4b. Hydrogen atoms, solvent molecules in 4b, and the counter anions GaCl4 have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths and bond angles are given in Table 1.

Fig. 5. Solid-state molecular structures of 5a and 5b. Hydrogen atoms, solvent molecules in 5b, and the counter anions GaCl4 have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths and bond angles are given in Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) of 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes (3a and 3b), radical cations (4a and 4b) and dication salts (5a and 5b).

| 3a | 3b | 4a | 4b | 5a | 5b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1–C2 | 1.386(1) | 1.384(2) | 1.432(2) | 1.433(2) | 1.479(3) | 1.478(2) |

| C2–P1 | 1.818(1) | 1.820(1) | 1.758(2) | 1.761(2) | 1.692(2) | 1.692(2) |

| P1–C3 | 1.735(1) | 1.735(1) | 1.785(2) | 1.790(2) | 1.865(2) | 1.853(2) |

| C1–N1 | 1.401(1) | 1.403(1) | 1.375(2) | 1.375(2) | 1.351(3) | 1.344(2) |

| C1–N2 | 1.408(1) | 1.412(1) | 1.382(2) | 1.385(2) | 1.355(3) | 1.356(2) |

| C3–N3 | 1.387(1) | 1.388(1) | 1.349(2) | 1.349(2) | 1.295(3) | 1.295(3) |

| C1–C2–P1 | 117.7(1) | 118.0(1) | 117.3(1) | 117.4(1) | 114.9(1) | 115.3(1) |

| C2–P1–C3 | 109.7(1) | 110.9(1) | 108.8(1) | 110.3(1) | 106.1(1) | 105.2(1) |

| P1–C3–N3 | 117.6(1) | 116.4(1) | 116.0(1) | 115.1(1) | 118.1(2) | 121.5(1) |

| N1–C1–N2 | 103.0(1) | 103.3(1) | 104.8(1) | 104.9(1) | 107.2(2) | 107.3(2) |

DFT calculated geometries of 3–5 are found to be fully in agreement with their solid-state molecular structures determined by X-ray diffraction (Table S5†). An increasing value of the WBIs (Wiberg Bond Indices) for the CNHV–P bond of 3a (0.95), 3b (0.95), 4a (1.22), 4b (1.22), 5a (1.63), and 5b (1.63) is consistent with the experimental C2–P1 bond lengths (Table 1). Similarly, the WBIs for the P–CcAAC (3a: 1.57, 3b: 1.56; 4a: 1.19, 4b: 1.18; 5a: 0.92, 5b: 0.91) as well as C–CPh (3a: 1.49, 3b: 1.49; 4a: 1.20, 4b: 1.20; 5a: 1.06, 5b: 1.06) bonds also exhibit the expected trend. The NPA (Natural Population Analysis) atomic partial charges (Table S5†) calculated using the NBO (Natural Bond Orbital) method indicate that the phosphorous atom in 3a (0.49e), 3b (0.49e), 4a (0.65e), 4b (0.65e), 5a (0.85e), and 5b (0.85e) carries a positive charge. The former IPr carbene carbon atom (C1) also bears a positive charge (3a 0.45e, 3b 0.44e, 4a 0.47e, 4b 0.47e, 5a 0.43e and 5b 0.43e), which is larger compared to that of the cAAC carbene carbon atom C3 (3a −0.08e, 3b −0.08e, 4a 0.04e, 4b 0.04e, 5a 0.23e and 5b 0.24e). This is most likely because of the greater π-acceptor property of cAACs compared to the IPr.

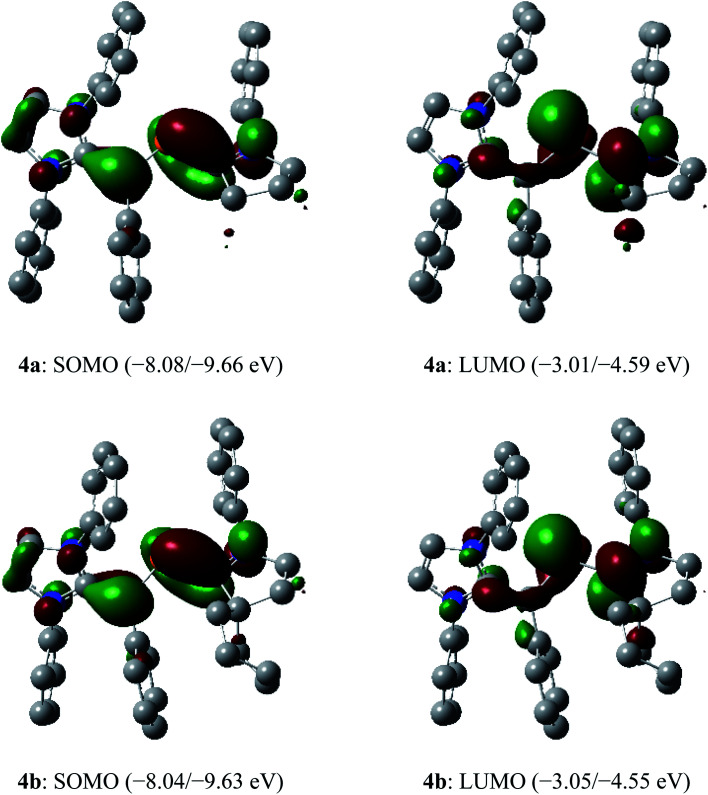

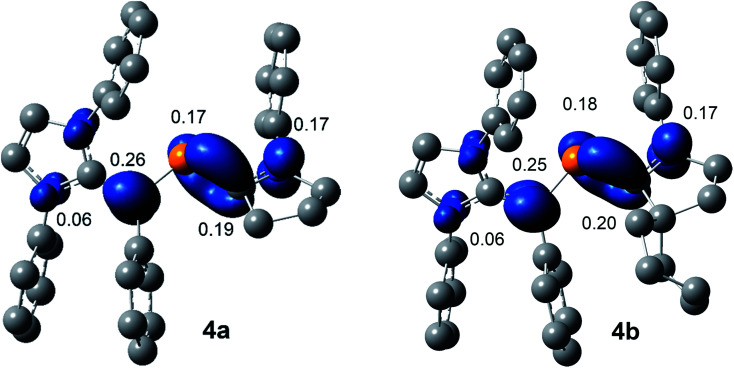

The SOMO (singly occupied molecular orbital) of 4a and 4b (Fig. 6) is the π-orbitals of the CIPr Cvinyl and P CcAAC bonds with a small contribution from the nitrogen atoms of the pyrrolidine and imidazole ring, whereas the LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) is the π*-orbitals of the P atom along with the π*-orbitals of CIPr Cvinyl and CcAAC–N bonds of NHV and cAAC, respectively. The localized Mulliken atomic spin density (Fig. 7) and the plot of the SOMO (Fig. 6) for 4a and 4b reveal that the unpaired electron is mainly delocalized over the CPCN moiety with an almost equal spin density distribution on the phosphorus (4a: 17%, 4b: 18%), carbene CcAAC (4a: 19%, 4b: 20%), and vinylic CPh (4a: 26%, 4b: 25%) atoms. The spin-density at the imidazole-ring nitrogen atoms (6% at each of N) of 4a and 4b is rather small compared to that at the pyrrolidine nitrogen atom (17%).

Fig. 6. Selected molecular orbitals (isovalue 0.04) of the radical cations 4a and 4b (α/β spin orbital energy) calculated at the M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//def2-SVP level of theory. Hydrogen atoms, methyl groups as well as iso-propyl groups were omitted for clarity.

Fig. 7. Calculated Mulliken spin densities (isovalue 0.004 a.u.) of radical cations 4a and 4b at M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//def2-SVP level of theory.

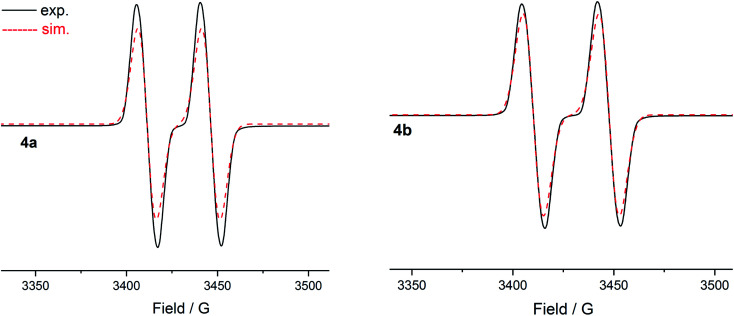

The room temperature X-band EPR spectra of 4a (g = 2.0064) and 4b (g = 2.0064) in THF exhibit a doublet (Fig. 8) owing to the coupling of the unpaired electron with the phosphorous nucleus (Aiso(31P) = 35 G 4a; 38 G 4b). The magnitude of the hyperfine coupling constant (hfc) of 4a and 4b is comparable to those observed for radical cations (II)˙+ (Aiso(31P) = 44 G)9b (III)˙+ (Aiso(31P) = 42 G),9b and (IV)˙+ (Aiso(31P) = 44 G),9c but that is larger than those of (V)˙+ (Aiso(31P) = 12–20 G) featuring a longer π-conjugated system (Fig. 1).15 This is, however, considerably smaller than that of the phosphinyl radical cation [(cAACCy)P(R)]˙+ (Aiso(31P) = 99 G) (R = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidino)9a as well as those observed for phosphinyl radicals R2P˙ (Aiso(31P) = 92–96 G) (R = HC(SiMe3)2 or N(SiMe3)2),8a,23 for which, particularly for the latter, the unpaired electron resides predominantly in a 3p(P) valence orbital. The value of coupling constants is in good agreement with the computed values (Table S12†). These hfcs corroborate with the delocalization of the spin-density along the CPCN moiety of 4a and 4b (Fig. 7). The measured EPR spectra of 4a and 4b were simulated by employing the g values, the hyperfine coupling for the phosphorus atom, and two linewidth parameters (Table S13†). The EPR spectra of 4a (Fig. S29†) and 4b (Fig. S30†) measured in a frozen THF solution at 80 K show an anisotropic pattern. The g-factors (4a: g‖ = 2.0062, g⊥ = 2.0082; 4b: g‖ = 2.0069, g⊥ = 2.0079) and hfc tensors (4a: Az(31P) = 149 MHz, Ax(31P) = −83 MHz, Ay(31P) = 39 MHz; 4b: Az(31P) = 179 MHz, Ax(31P) = −71 MHz, Ay(31P) = 49 MHz) were determined. The analysis of hfc tensors reveals the major contribution of phosphorus 3p (4a: 11.8%; 4b: 12.8%) orbital to the SOMO, whereas the contribution of the 3s (4a: 0.45%; 4b: 0.46%) orbital is small.

Fig. 8. X-band EPR spectra of radical cations 4a and 4b in THF at 298 K.

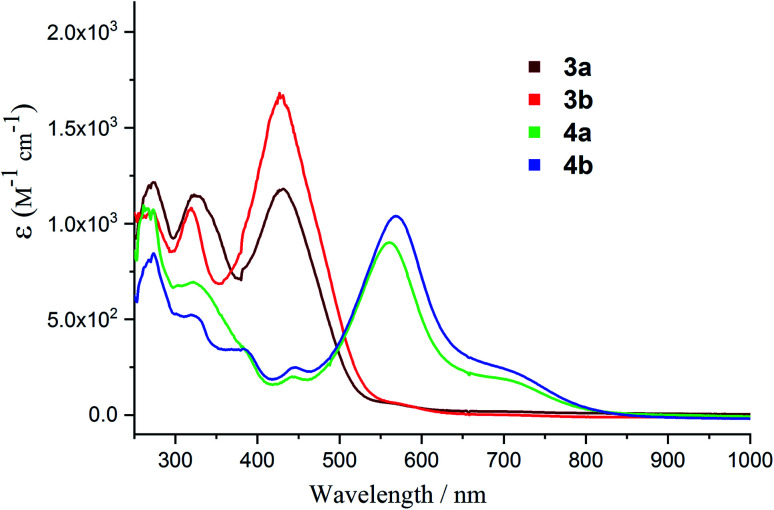

The UV-vis spectra of both 2-phospha-1,3-butadienes 3a (277, 331, 427 nm) and 3b (271, 322, 430 nm) exhibit three main absorptions (Fig. 9) which, based on TD-DFT calculations at TD-PCM(thf)/M06-2X/def2-SVP level of theory, comprise dominant contributions of the H−1 → L, H → L+2, and H → L transitions, respectively (Fig. S32 and S33, Tables S6 and S7†). The UV-vis spectra of the radical cations 4a and 4b, respectively show a broad absorption at 563 and 571 nm along with a shoulder at ca. 700 nm (Fig. 9) that corresponds to the SOMO-related transitions S → L and S−1 → S (Tables S8 and S9†).

Fig. 9. UV-vis spectra of 3a and 3b and their radical cations 4a and 4b in THF.

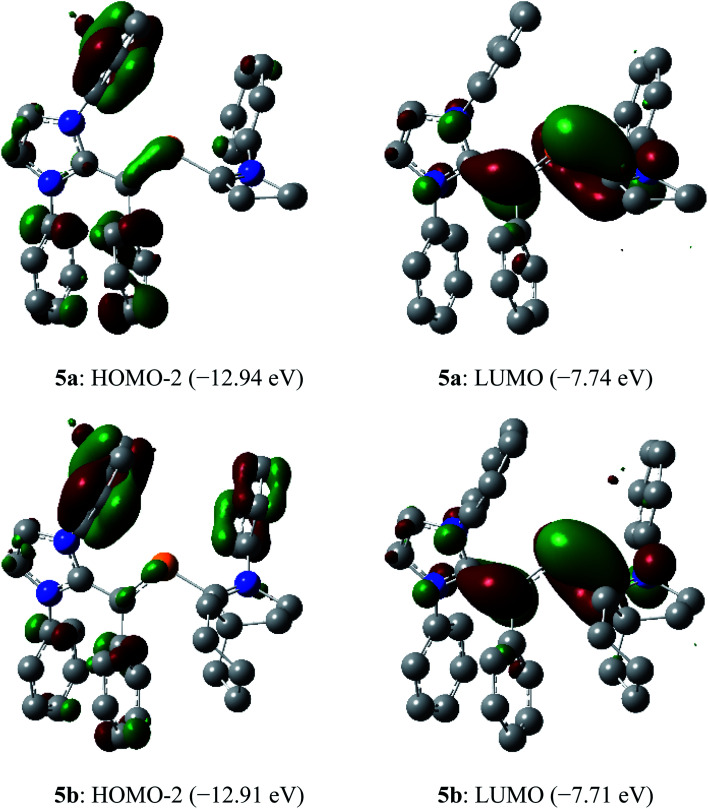

In the dications 5a and 5b, the HOMO-2 is a π-type orbital with contributions from the aryl groups and Cvinyl–P bond (Fig. 10). The LUMO of 5a and 5b is the π-orbital of the CIPr Cvinyl and P CcAAC bonds with a small contribution from the nitrogen atoms of pyrrolidine and imidazole rings. Upon removal of one and two electrons from the π-type orbital of 3a and 3b, the HOMO of 3a and 3b (Fig. 3) becomes SOMO in the radical cations 4a and 4b (Fig. 6) and LUMO in the dications 5a and 5b (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Selected molecular orbitals (isovalue 0.04) of the dications 5a and 5b calculated at M06-2X/def2-TZVPP//def2-SVP level of theory. Hydrogen atoms, methyl groups as well as iso-propyl groups were omitted for clarity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have isolated the crystalline 2-phospha-1,3-butadiene derivatives 3a and 3b by a rational choice of combining a weak π-acceptor (IPr) and a strong π-acceptor (cAACR) singlet carbene scaffolds. Sequential one-electron oxidation of 3a and 3b affords the radical cations 4a and 4b and the dications 5a and 5b. The isolation of 4a, 4b and 5a, 5b as crystalline solids is consistent with the redox properties of 3a and 3b analyzed by electrochemical studies. Molecular structures of all compounds in the solid-state were established by single crystal X-ray diffraction. Computational and EPR spectroscopic data indicate that the unpaired electron in 4a and 4b is delocalized over the CPCN π-conjugated framework. The study emphasizes the advantage of merging singlet carbenes with dissimilar donor–acceptor properties in accessing stable open-shell π-conjugated systems. As a variety of stable singlet carbenes with adaptable properties are readily accessible, it is very likely that many π-conjugated systems with other heavier main-group elements, which are hitherto believed to be synthetically challenging targets, may be isolated.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financial support and thank Professor Norbert W. Mitzel for his constant support. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by computing time provided by the Paderborn Center for Parallel Computing (PC2).

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 1949887–1949892 and 1951632. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c9sc05598c

References

- (a) Wang C. Dong H. Hu W. Liu Y. Zhu D. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2208–2267. doi: 10.1021/cr100380z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu W. Liu Y. Zhu D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1489–1502. doi: 10.1039/B813123F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang Y. Sun L. Wang C. Yang F. Ren X. Zhang X. Dong H. Hu W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:1492–1530. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00406D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang J. Yan D. Jones T. S. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:5570–5603. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee C. Lee S. Kim G.-U. Lee W. Kim B. J. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:8028–8086. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Vidal F. Jäkle F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:5846–5870. doi: 10.1002/anie.201810611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pop F. Zigon N. Avarvari N. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:8435–8478. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stolar M. Baumgartner T. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:3311–3322. doi: 10.1039/C8CC00373D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hirai M. Tanaka N. Sakai M. Yamaguchi S. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:8291–8331. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dhbaibi K. Favereau L. Crassous J. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:8846–8953. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Baumgartner T. Réau R. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4681–4727. doi: 10.1021/cr040179m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Parke S. M. Boone M. P. Rivard E. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:9485–9505. doi: 10.1039/C6CC04023C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Priegert A. M. Rawe B. W. Serin S. C. Gates D. P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:922–953. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00725A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zeng Z. Shi X. Chi C. Lopez Navarrete J. T. Casado J. Wu J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:6578–6596. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00051C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gopalakrishna T. Y. Zeng W. Lu X. Wu J. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:2186–2199. doi: 10.1039/C7CC09949E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakano M. Fukuda K. Ito S. Matsui H. Nagami T. Takamuku S. Kitagawa Y. Champagne B. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2017;121:861–873. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b11647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nakano M. Chem. Rec. 2017;17:27–62. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201600094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang Y. Davidson E. R. Yang W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E5098–E5107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606021113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Su Y. Wang X. Zheng X. Zhang Z. Song Y. Sui Y. Li Y. Wang X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:2857–2861. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Casado J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017;375:73. doi: 10.1007/s41061-017-0163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Simpson M. C. Protasiewicz J. D. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013;85:801–815. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pantazis D. A. McGrady J. E. Lynam J. M. Russell C. A. Green M. Dalton Trans. 2004:2080–2086. doi: 10.1039/B405609D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dillon K. B., Mathey F. and Nixon J. F., Phosphorus: The Carbon Copy, John Wiley & Sons, New York: 1998 [Google Scholar]

- (a) Schmidt M. W. Truong P. N. Gordon M. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5217–5227. doi: 10.1021/ja00251a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schleyer P. v. R. Kost D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:2105–2109. doi: 10.1021/ja00215a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Fischer R. C. Power P. P. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3877–3923. doi: 10.1021/cr100133q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nyulaszi L. Veszpremi T. Reffy J. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:4011–4015. doi: 10.1021/j100118a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Szűcs R. Bouit P.-A. Nyulászi L. Hissler M. ChemPhysChem. 2017;18:2618–2630. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201700438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nyulászi L. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:1229–1246. doi: 10.1021/cr990321x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hicks R. G., Stable Radicals: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, 2010 [Google Scholar]; (b) Kundu S. Sinhababu S. Chandrasekhar V. Roesky H. W. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:4727–4741. doi: 10.1039/C9SC01351B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tan G. W. Wang X. P. Chin. J. Chem. 2018;36:573–586. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201700802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim Y. Lee E. Chem.–Eur. J. 2018;24:19110–19121. doi: 10.1002/chem.201801560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Su Y. Kinjo R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;352:346–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Soleilhavoup M. Bertrand G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:256–266. doi: 10.1021/ar5003494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Martin C. D. Soleilhavoup M. Bertrand G. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3020–3030. doi: 10.1039/C3SC51174J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Chivers T. and Konu J., in Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II: From Elements to Applications, ed. J. Reedijk and K. Poeppelmeier, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2013, vol. I, pp. 349–373 [Google Scholar]; (i) Konu J. and Chivers T., in Stable Radicals: Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds, ed. R. G. Hicks, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2010, pp. 381–406 [Google Scholar]; (j) Breher F. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007;251:1007–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (k) Power P. P. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:789–809. doi: 10.1021/cr020406p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Grützmacher H. Breher F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:4006–4011. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4006::AID-ANIE4006>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Mondal K. C. Roy S. Roesky H. W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:1080–1111. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00739A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hinchley S. L. Morrison C. A. Rankin D. W. H. Macdonald C. L. B. Wiacek R. J. Cowley A. H. Lappert M. F. Gundersen G. Clyburne J. A. C. Power P. P. Chem. Commun. 2000:2045–2046. doi: 10.1039/B004889P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Armstrong A. Chivers T. Parvez M. Boeré R. T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:502–505. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ito S. Kikuchi M. Yoshifuji M. Arduengo III A. J. Konovalova T. A. Kispert L. D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4341–4345. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Agarwal P. Piro N. A. Meyer K. Müller P. Cummins C. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3111–3114. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Back O. Donnadieu B. von Hopffgarten M. Klein S. Tonner R. Frenking G. Bertrand G. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:858–861. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00027F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Beweries T. Kuzora R. Rosenthal U. Schulz A. Villinger A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:8974–8978. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hinz A. Schulz A. Villinger A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:668–672. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Gu L. Zheng Y. Haldón E. Goddard R. Bill E. Thiel W. Alcarazo M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:8790–8794. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Chen X. Hinz A. Harmer J. R. Li Z. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:2549–2553. doi: 10.1039/C8DT04842H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Li Z. Hou Y. Li Y. Hinz A. Harmer J. R. Su C.-Y. Bertrand G. Grützmacher H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018;57:198–202. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Tondreau A. M. Benko Z. Harmer J. R. Grützmacher H. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:1545–1554. doi: 10.1039/C3SC53140F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Back O. Celik M. A. Frenking G. Melaimi M. Donnadieu B. Bertrand G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10262–10263. doi: 10.1021/ja1046846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Back O. Donnadieu B. Parameswaran P. Frenking G. Bertrand G. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:369–373. doi: 10.1038/nchem.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kinjo R. Donnadieu B. Bertrand G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:5930–5933. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ménard G. Hatnean J. A. Cowley H. J. Lough A. J. Rawson J. M. Stephan D. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:6446–6449. doi: 10.1021/ja402964h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pan X. Su Y. Chen X. Zhao Y. Li Y. Zuo J. Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5561. doi: 10.1021/ja402492u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Pan X. Chen X. Li T. Li Y. Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3414–3417. doi: 10.1021/ja4012113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Su Y. Zheng X. Wang X. Zhang X. Sui Y. Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6251–6254. doi: 10.1021/ja502675d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Brückner A. Hinz A. Priebe J. B. Schulz A. Villinger A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:7426–7430. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Pan X. Wang X. Zhang Z. Wang X. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:15099–15102. doi: 10.1039/C5DT00656B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cantat T. Biaso F. Momin A. Ricard L. Geoffroy M. Mézailles N. Le Floch P. Chem. Commun. 2008:874–876. doi: 10.1039/B715380E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pi C. Wang Y. Zheng W. Wan L. Wu H. Weng L. Wu L. Li Q. Schleyer P. v. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:1842–1845. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pan X. Wang X. Zhao Y. Sui Y. Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9834–9837. doi: 10.1021/ja504001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan G. Li S. Chen S. Sui Y. Zhao Y. Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:6735–6738. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Asami S.-s. Ishida S. Iwamoto T. Suzuki K. Yamashita M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:1658–1662. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Mondal M. K. Zhang L. Feng Z. Tang S. Feng R. Zhao Y. Tan G. Ruan H. Wang X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:15829–15833. doi: 10.1002/anie.201910139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Appel R. Kündgen U. Knoch F. Chem. Ber. 1985;118:1352–1370. doi: 10.1002/cber.19851180407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Appel R. Knoch F. Kunze H. Chem. Ber. 1984;117:3151–3159. doi: 10.1002/cber.19841171014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Appel R. Barth V. Knoch F. Chem. Ber. 1983;116:938–950. doi: 10.1002/cber.19831160311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (d) Breit B. Memmesheimer H. Boese R. Regitz M. Chem. Ber. 1992;125:729–732. doi: 10.1002/cber.19921250328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (e) Seidl M. Stubenhofer M. Timoshkin A. Y. Scheer M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:14037–14040. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Mackewitz T. W. Ullrich D. Bergsträßer U. Leininger S. Regitz M. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1997;1997:1827–1839. doi: 10.1002/jlac.199719970906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (g) Guillemin J. C. Cabioch J. L. Morise X. Denis J. M. Lacombe S. Gonbeau D. Pfister-Guillouzo G. Guenot P. Savignac P. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:5021–5028. doi: 10.1021/ic00075a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Xie Y. Wei P. King R. B. Schaefer III H. F. Schleyer P. v. R. Robinson G. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14970–14971. doi: 10.1021/ja807828t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back O. Kuchenbeiser G. Donnadieu B. Bertrand G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5530–5533. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottschäfer D. Sharma M. K. Neumann B. Stammler H.-G. Andrada D. M. Ghadwal R. S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2019;25:8127–8134. doi: 10.1002/chem.201901204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M. K. Rottschäfer D. Blomeyer S. Neumann B. Stammler H.-G. van Gastel M. Hinz A. Ghadwal R. S. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:10408–10411. doi: 10.1039/C9CC04701H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Rottschäfer D. Neumann B. Stammler H.-G. Kishi R. Nakano M. Ghadwal R. S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2019;25:3244–3247. doi: 10.1002/chem.201901204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sharma M. K. Blomeyer S. Neumann B. Stammler H. G. Ghadwal R. S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2019;25:8249–8253. doi: 10.1002/chem.201901857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sharma M. K. Blomeyer S. Neumann B. Stammler H.-G. van Gastel M. Hinz A. Ghadwal R. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:17599–17603. doi: 10.1002/anie.201909144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallo V. Canac Y. Präsang C. Donnadieu B. Bertrand G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5705–5709. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- No reaction between {(IPr)C(Ph)PCl2} (1) and a weak π-acceptor NHC (IPr or SIPr) was observed under similar experimental conditions

- Manz B. Bergsträßer U. Kerth J. Maas G. Chem. Ber. 1997;130:779–788. doi: 10.1002/cber.19971300617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kühl O., Phosphorus-31 NMR Spectroscopy, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 2008 [Google Scholar]; (b) Gudimetla V. B. Ma L. Washington M. P. Payton J. L. Cather Simpson M. Protasiewicz J. D. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010:854–865. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200900870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P. Atsumi M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009;15:186–197. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathey F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:1578–1604. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchley S. L. Morrison C. A. Rankin D. W. H. Macdonald C. L. B. Wiacek R. J. Voigt A. Cowley A. H. Lappert M. F. Gundersen G. Clyburne J. A. C. Power P. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9045–9053. doi: 10.1021/ja010615b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.