Abstract

We conducted an empirical examination of derived relational responding as a generalized operant and concurrently evaluated the validity and efficacy of program items contained in the Promoting the Emergence of Advanced Knowledge - Equivalence (PEAK-E) curriculum. A first study utilized a multiple-baseline across-skills experimental arrangement to determine the efficacy of equivalence-based instruction guided by PEAK-E, replicated across 11 children with autism. A total of 33 individualized skills were taught, and the subsequent emergence of untrained relations was tested throughout the investigation. The mastery criterion was achieved for 29 of the 33 instructional targets. Additionally, for 3 participants, results were again replicated with a novel set of stimuli. A second study evaluated the degree to which multiple-exemplar equivalence-based instruction led to the emergence of derived relational responding as a generalized operant. The organized nature of the PEAK curriculum allowed the impact on derived relational responding to be compared to that produced by earlier PEAK models that are focused on the direct training of traditional verbal operants. PEAK-E instruction was introduced in a multiple-baseline design across two participants, with a third staying in a training baseline throughout. Increases in derived relational responding using novel, untrained stimuli were only observed when multiple-exemplar equivalence-based instruction was introduced. Taken together, these results provide support for derived relational responding as a generalized operant and demonstrate the utility of conducting larger scale evaluations of higher order behavioral phenomena in single-case experimental arrangements.

Keywords: Autism, Derived responding, Equivalence-based instruction, PEAK

Behavior-analytic language-training technologies that emerge from a derived relational account of language development are increasingly being applied with children with autism and other language-learning disorders (Rehfeldt, 2011; Rehfeldt & Barnes-Holmes, 2009). Approaches that emphasize derived relational responding, including relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), stimulus equivalence (Sidman, 1971; Sidman & Tailby, 1982), and bidirectional naming (Miguel & Petursdottir, 2009) stress the importance of relational repertoires that, once established, foster learning in the absence of direct-acting contingencies. Training programs focused on these repertoires have the potential to improve the efficiency of language instruction for socially significant populations (Dixon, Daar, Rowsey, & Belisle, 2015; Sidman & Tailby, 1982), and offer alternative behavior-analytic accounts of complex verbal behavior events than that proposed by Skinner (see Barnes & Holmes, 1991; Hayes et al., 2001; Hayes & Wilson, 1993, for a review).

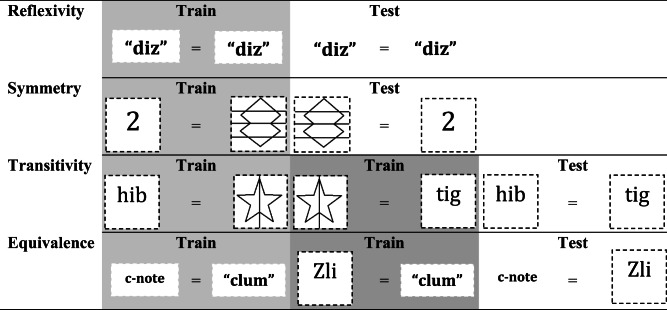

The first behavior-analytic demonstrations of derived relational responding were provided within a stimulus-equivalence framework, where three events are required for demonstration of derived equivalence: reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity. Reflexivity refers to matching a stimulus (A) to an identical stimulus (A; A-A) and is the simplest relational subunit required for stimulus equivalence. Symmetry occurs when a participant is directly reinforced for responding to a sample stimulus (A) in terms of another arbitrarily related comparison stimulus (B; A-B), and the participant can respond bidirectionally to the comparison stimulus as a sample (B) in terms of the original sample stimulus as a comparison (A; B-A). Transitivity is shown when a participant responds to a stimulus in terms of another arbitrarily related stimulus based on a common relationship with a third stimulus. For example, when taught to respond to a stimulus (A) in terms of a second stimulus (B; A-C), and to respond to the second stimulus (B) in terms of the third stimulus (C; B-C), the participant can also respond to the first stimulus (A) in terms of the third stimulus (C) without direct training. Both symmetry and transitivity are demonstrated when a bidirectional transitive response is also demonstrated. In the previous example, demonstration of an equivalence relationship would require that the participant demonstrates both the derived A-C relation and a derived C-A relation.

If an individual can derive relations in any or all of the aforementioned ways, rates of learning are considerably increased (e.g., if 4 relations are directly reinforced, a total of 12 relations can be demonstrated). Research spanning at least four decades has established that direct-reinforcing contingencies are not required for the emergence of conditional discriminations once prior, related conditional discriminations have been established (Guinther & Dougher, 2015; Hughes & Barnes-Holmes, 2014; Sidman, 1971). Stimulus equivalence and related phenomena have been shown to increase the efficiency of language training, and as instructional strategies for elementary and complex academic skills (Albright, Reeve, Reeve, & Kisamore, 2015; Keintz, Miguel, Kao, & Finn, 2011), flexible conversation skills (Daar, Negrelli, & Dixon, 2015; O’Neill & Rehfeldt, 2017), and early perspective-taking skills (Belisle et al., 2016; Lovett & Rehfeldt, 2014), many in application with individuals with autism (see McLay, Sutherland, Church, & Tyler-Merrick, 2013, for a review).

Perhaps the greatest limitation of stimulus equivalence within a functional-analytic account of language development is that it is merely a behavioral outcome until the functional processes that give rise to it are known and are shown to be consistent with Skinner’s basic premise: that verbal behavior is operant behavior (D. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Cullinan, 2000). A way to do that was provided by RFT (Hayes, 1991; Hayes et al., 2001). Within RFT, deriving relations among stimuli provides an example of a generalized operant behavior that, once learned, is analogous to generalized motor imitation or any other higher order operant response class (D. Barnes-Holmes & Barnes-Holmes, 2000; Healy, Barnes-Holmes, & Smeets, 2000). Reflexivity provides the simplest demonstration in that reflexivity does not require that an individual is provided direct reinforcement following every instance of a matching response across all knowable stimulus object topographies; rather, once multiple exemplars of matching have contacted direct reinforcement, an individual will be able to match any two identical novel objects regardless of topography. Similarly, when an individual is provided reinforcement for deriving multiple exemplars of symmetrical and transitive relations, these relations occur with a higher probability in the future and are not limited to the exemplars in which deriving as an operant has been reinforced. For example, if an individual is reinforced for deriving multiple A-C and C-A relations following A-B and B-C linear relational training, the probability that the individual will derive A-C and C-A relations in the absence of reinforcement in the future is increased when A-B and B-C relations are directly taught.

Although each of these relational subunits has been experimentally demonstrated with both individuals with autism and individuals without language-learning impairments, early critics of an operant account of derived relational responding questioned how individuals could come to derive relations in the absence of direct-acting contingencies (McIlvane, 2003; Palmer, 2004a, 2004b), and instead put forward hypotheses, such as mediating verbal response chains, perhaps covert, that may account for the untrained emergence of derived relations (Malott, 2003; Palmer, 2004a). If these events do occur, they at best provide a more atomistic and mechanistic description of the event of interest. Allusion to these possible covert events is reductionistic, as indeed the covert behaviors, if they occur at all, are part of the derived response rather than separate from, and causally related to, the derived response. Indeed, some research has demonstrated that reinforcing derived relational responding as a generalized operant behavior can improve mediating behaviors that participate in some instances of relational responding, though this research was published as support of mediating events (Ma, Miguel, & Jennings, 2016; Miguel, 2016). From a pragmatic perspective, reducing derived relational responding to mediating events is only useful insofar as their manipulation is required to demonstrate improvement in derived relational responding. Conversely, it appears to be the case that manipulating derived relational responding as an operant may be required to effect changes in mediating events. Regardless of theoretical differences, the common theme running through RFT and other conceptualizations is that the behaviors (i.e., relating, naming, intraverbal response chains) all emerge through multiple-exemplar training and can be applied to any number of untrained, novel stimuli once the generalized operant response is acquired.

In a pragmatic science, the best experimental way to determine if treating derived relational responding as a generalized operant in its own right holds utility is to train derived relational responding as an operant through multiple exemplars and to test using novel exemplars for untrained emergence. To some degree, that has been done with more elaborate derived relations than equivalence, such as comparison (e.g., Berens & Hayes, 2007), but it has proven difficult with stimulus equivalence because typically developing individuals demonstrate derived equivalence relations at a very young age and in the absence of targeted intervention (Lipkens, Hayes, & Hayes, 1993), and animal models are nonexistent because no nonhuman animal has yet consistently demonstrated equivalence responding (Dugdale & Lowe, 2000; Hayes, 1989; Lionello-DeNolf & Urcuioli, 2002; Sidman et al., 1982). Both events have limited experimental evaluations of derived relational operant development in its earliest stages (Y. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & McHugh, 2004; Hayes et al., 2001). An initial attempt by Luciano, Becerra, and Valverde (2007) provided some supportive data, but in the absence of extensive experimental control.

One way to make progress on this point is to turn to applied behavior-analytic work with individuals with autism, who often have clear deficits both in language more generally and in derived relational responding (Rehfeldt & Barnes-Holmes, 2009; Rehfeldt, Dillen, Ziomek, & Kowalchuk, 2007). Some individuals with autism have shown elaborate relational networks in prior investigations of equivalence-based instructional strategies (e.g., Keintz et al., 2011; Lovett & Rehfeldt, 2014), but these are only possible if the participants can derive relations in the first place. Indeed, this has been discussed as a limitation in prior research, where the authors have suggested that the demonstrated relational classes may not have occurred if the procedures had been applied with other participants with fewer prerequisite relational abilities (e.g., Dixon, Belisle, Stanley, Munoz, & Speelman, 2017b).

Individuals with autism respond well to operant language-training procedures, which are currently predominantly based on a limited Skinnerian framework (Skinner, 1957) emphasizing elementary forms of verbal operant responding (Dixon, Small, & Rosales, 2007; Dymond, O’Hora, Whelan, & O’Donovan, 2006). What has been missing is a clear and applicable language-teaching curriculum that would enable a direct test of derived relational responding per se as operant behavior. Building on earlier, preliminary efforts (Rehfeldt & Barnes-Holmes, 2009), the Promoting the Emergence of Advanced Knowledge Relational Training System (Dixon, 2014a, 2014b, 2015) eliminates that barrier. The PEAK Equivalence Module (PEAK-E; Dixon, 2015) is the first instructional protocol focused on derived relational responding that is intended for use with individuals with autism (Dixon et al., 2015). PEAK-E is the third of four modules in the PEAK Relational Training System. The two prior PEAK modules are the PEAK Direct Training Module (PEAK-DT; Dixon, 2014a), which focuses exclusively on verbal operant behavior under the control of direct-acting contingencies (e.g., tacts, mands, intraverbals; Dixon, Whiting, & Daar, 2014b), and the PEAK Generalization Module (PEAK-G; Dixon, 2014b), which teaches more complex topographies of verbal behavior and tests for the untrained emergence of generalized verbal skills (Dixon, Whiting, Daar, & Rowsey, 2014a). These first two modules are systematized forms of traditional Skinnerian-based language instruction, whereas PEAK-E branches out into equivalence (and the fourth module branches out into derived relations other than equivalence). All modules contain a preassessment (e.g., PEAK-E-PA; Dixon, 2015), a 184-item instructional assessment (e.g., PEAK-E-A), and 184 instructional programs that correspond directly to items in the instructional assessment.

Although several single-case and between-groups evaluations have supported the efficacy of single programs contained in the PEAK modules for teaching a variety of socially important skill topographies, research evaluating the entirety of the curriculum, or any applied behavior analysis (ABA) curriculum, is almost absent (Dixon, Belisle, McKeel, Whiting, Speelman, Daar, & Rowsey, 2017a). We know, for example, that three children in a multiple-baseline design can be taught basic academic content using equivalence procedures, but we do not know (a) with whom will the procedures be effective, given large variations in language impairments associated with autism, or (b) the degree to which teaching numerous skills, not just three academic skills, can lead to improvements in derived relational responding in general, regardless of skill topography.

The first question is somewhat dealt with through the use of the PEAK assessments, which are designed to isolate specific skills for targeted instruction. Although the convergent and other forms of construct validity of the PEAK assessments have been evaluated in prior research (e.g., Dixon, Belisle, Whiting, & Rowsey, 2014a; Rowsey, Belisle, & Dixon, 2015), these types of validity are more often assessed in terms of norm-referenced assessments (e.g., the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fifth Edition; Canivez, 2014), and hypothetico-deductive construct creation in the behavioral sciences is largely avoided (Hayes & Brownstein, 1986). Criterion validity, alternatively, refers to the degree to which an assessment is predictive of specific outcomes. Given that the general purpose of criterion-referenced assessments in ABA is to identify target skills for training, the criterion validity of an assessment would necessitate that the assessment identifies skills that participants can and cannot reliably demonstrate and can and cannot learn utilizing current ABA technologies (i.e., they have a sufficient preexisting skill repertoire). Empirically, criterion validity and training efficacy are unified concepts, as demonstrating that an assessment identifies skills that a participant can learn would require teaching that skill. This type of validity has also been referred to as “intervention validity,” in that behavioral assessment is considered valid only insofar as the measure leads to meaningful intervention strategies (Cone, 1997; Elliott, Gresham, Frank, & Beddow, 2008).

The second question is perhaps more important than the first and concerns the degree to which teaching several exemplar topographies can lead to the emergence of higher order generalized operant behaviors. The existence of these modules allows a highly similar contingency-based approach to be applied seamlessly to traditional verbal operants, to their increased complexity and generalization, and to the derived relational responses that make up stimulus equivalence. If derived relational responses are generalized operant behavior, increases in derived relational performances should at least initially require operant training that goes beyond training of verbal operant behavior under the control of direct-acting contingencies. If that proves to be the case, it would also suggest that it is a mistake to limit verbal training to these forms. Given that derived relational responding is known to be key to verbal development (e.g., Devany, Hayes, & Nelson, 1986), as an applied matter, if derived relational responding is generalized operant behavior as RFT suggests, then training protocols need to be expanded to include these key targets, as is done in the PEAK system. A successful curricular package, assuming that derived relational responding is a generalized operant behavior, should therefore accomplish four goals: (a) determine current levels of derived relational responding of any participant; (b) determine relational skill topographies that are not in the participant’s repertoire for targeted instruction; (c) establish several new skill topographies based on the results of a valid assessment, using equivalence-based training technologies; and (d) improve derived relational responding as a generalized operant, such that derived relations occur across any novel untrained stimulus following training of multiple topographical exemplars.

In the current study, we conducted two experiments to determine if the procedures in the PEAK-E module could meet the aforementioned goals, where doing so would serve to both evaluate the validity and efficacy of the PEAK system and support derived relational responding as a generalized operant. The first experiment sought to evaluate the criterion validity and corresponding efficacy of PEAK-E. In evaluating the criterion validity and efficacy of the entire PEAK-E system, we sought to determine if the results of the PEAK-E-PA and the PEAK-E-A provided individualized targets for each of the participants in the study (i.e., produced differentiated results) and if the procedures described in the PEAK-E curriculum were efficacious in teaching the target skills. The second experiment sought to evaluate the development of derived relational responding as a generalized operant behavior over the course of a regular school year with individuals with autism. Equivalence-based multiple-exemplar training of socially relevant skill topographies was guided by the PEAK-E curriculum, and the subsequent emergence of novel, untrained patterns of derived relational responding was compared to a training baseline guided by the prior two PEAK modules (PEAK-DT/G). The procedures demonstrate the use of a concurrent multiple-baseline design conducted over the course of approximately 9 months, where several new verbal response topographies were established, and more global changes in higher order responding were evaluated using time-series logic.

Experiment 1: Examining the Validity and Efficacy of Individual PEAK-E Items

Method

Participants and settings

A total of 11 children recruited from four unique ABA service providers throughout the Midwestern United States participated in the first experiment. All participants were receiving ABA services either in their homes or at their schools, ranging from 5 to 15 hr of ABA services per week. None of the ABA services were guided by the PEAK-E protocol at the time of the study, and the participants had no prior exposure to PEAK-E. All participants had a diagnosis of autism. Regular therapy sessions outside of the study were partially conducted with the participants by four of the authors of the current investigation, who also implemented the procedures described in the study. The authors who primarily worked with each participant prior to the study were the implementers of the procedures with that participant throughout the study. This was done to avoid exposure effects that could have occurred with the use of a novel implementer.

- Participants

- Tim. Tim was an 8-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a specialized elementary school for children with autism and related disabilities. He did not receive specialized behavioral services for challenging behavior. Tim received approximately 10 hr of in-home ABA services per week, including discrete-trial training and naturalistic teaching strategies.

- Clara. Clara was a 4-year-old girl with a diagnosis of autism. She attended a special education preschool 2 days per week. She was not receiving specialized behavioral services for challenging behavior at the time of the study. Clara also received approximately 10 hr of in-home ABA services per week, utilizing discrete-trial training and naturalistic teaching approaches.

- Jace. Jace was an 8-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a regular kindergarten classroom during the day and had a regular one-on-one paraprofessional. Jace had been receiving behavioral services at his school for moderate challenging behavior, including vocal disruptions and off-task behavior. He also received 10 hr of weekly in-home ABA therapy.

- Rob. Rob was a 4-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism and a comorbid developmental delay. He attended a public early childhood center and received specialized education and regular assistance from a paraprofessional. He received regular speech-language instruction at the center and 5 hr of in-home ABA instruction. Center staff did not report any challenging behaviors at the time of the study.

- Joseph. Joseph was an 8-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a general education classroom and received specialized educational support with access to a classroom paraprofessional. He also received speech-language services at school and approximately 10 hr of weekly in-home ABA instruction. At the time of the study, no challenging behaviors were reported by Joseph’s guardians.

- Jillian. Jillian was a 15-year-old girl with diagnoses of autism and cerebral palsy. She attended a regular education high school and was enrolled in special education courses. Jillian received approximately 10 hr of ABA instruction at home, focusing on improving social and daily living skills, and her guardians did not report any challenging behavior at the time of the study.

- Kris. Kris was a 6-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a regular education classroom and received special education services with the assistance of a paraprofessional. He received approximately 12 hr of in-home ABA services per week, focusing on discrete-trial training and naturalistic instructional strategies. Kris was not receiving specialized services for challenging behavior at the time of the study.

- Sam. Sam was an 11-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism and was Kris’s biological brother. He attended a specialized education classroom in a public school, where he additionally received speech-language services. He also received approximately 12 hr of weekly in-home ABA services. Although Sam did not have a formal behavior plan for challenging behaviors, staff reported that Sam engaged in infrequent disruptive vocalizations.

- Lucy. Lucy was a 5-year-old girl with a diagnosis of autism. Lucy attended a full-day kindergarten program that was cotaught by a special education teacher and a regular education teacher. She received speech-language and occupational therapy services at school and approximately 15 hr of in-home ABA services. School staff did not report any challenging behaviors at the time of the study.

- Lawton. Lawton was a 5-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a full-day kindergarten program at a Montessori school, where he was provided special education services for half of each school day. He received approximately 10 hr of in-home ABA services, and his guardians did not report any challenging behavior at the time of the study.

- Ladd. Ladd was an 8-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He attended a general education classroom at a public school. He received in-home ABA services for approximately 15 hr per week, focusing on skill acquisition and social skills training. His guardians did not report any challenging behavior at the time of the study.

- Instructional settings

- School-based instruction. School-based instruction was conducted for Rob, Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd, which took place in an area of the participants’ regular classrooms separated from other students or in a separate room in the school (e.g., the library). The work area contained a desk and two chairs, and attempts were made to ensure the work area was free of distracting stimuli. In addition, the area contained three to five preferred stimuli specific to each of the participants, as well as any materials needed to conduct the PEAK-E assessments or target programs. All preferred stimuli were provided by the classroom teacher prior to the onset of the sessions.

- Home-based instruction. Instruction for Tim, Clara, Jace, Joseph, Jillian, Sam, and Kris took place in the participants’ homes. All home-based instruction was conducted in a room separate from other household members, as designated by the families for therapy. Rooms minimally contained a desk and two chairs. In addition, rooms contained stimuli required to implement the PEAK-E assessments and target programs, as well as preferred stimuli specific for each of the participants. All preferred stimuli were provided by the guardians of the participants at the onset of each session.

Materials

PEAK-E Preassessment (PEAK-E-PA)

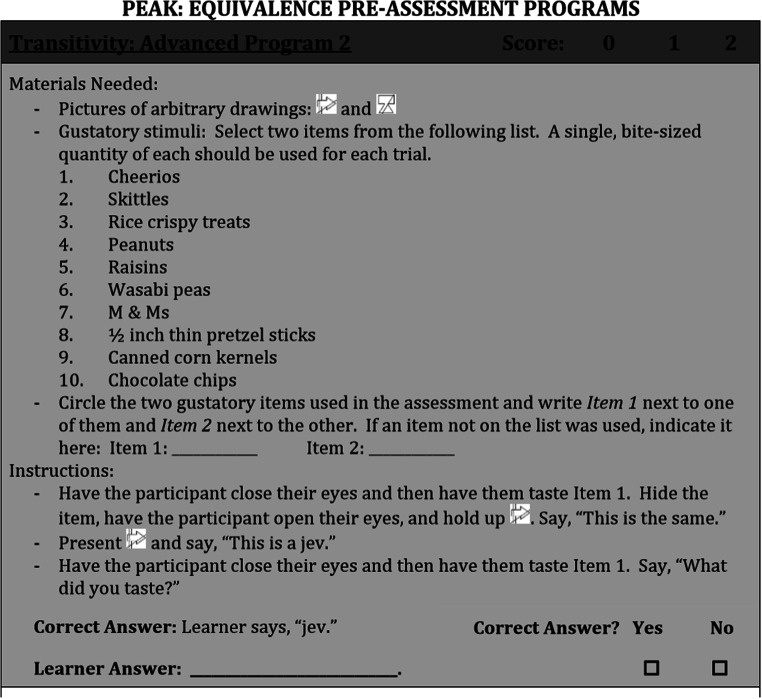

The PEAK-E-PA is a 48-item criterion-referenced assessment of participants’ abilities to derive reflexive, symmetrical, transitive, and equivalence relations. The assessment has four subtests, each corresponding with a type of relational responding (i.e., reflexivity, symmetry, transitivity, and equivalence). Participant scores on each subtest range from 0 to 12, and these scores are summed to arrive at a PEAK-E-PA total score ranging from 0 to 48. An exemplar test item is shown in Fig. 1. The items in each subtest range in complexity from basic, to intermediate, to advanced skills. For example, a Basic Reflexivity program may evaluate a participant’s picture matching skill, whereas an Advanced Reflexivity item may evaluate a participant’s skill at the sequential matching of presented tactile stimuli. There are two items at each level (e.g., Basic Symmetry 1 and Basic Symmetry 2). If the PEAK-E-PA Long Form assessment is conducted, each item is assessed two times using different stimuli, and each correct answer is given a score of 1. If the PEAK-E-PA Short Form assessment is conducted, each item is only assessed one time, and each correct answer is given a score of 2. A train-and test-strategy is used for each of the items to evaluate participants’ derivations of increasingly complex relations. Table 1 provides a summary of the train-and-test strategy across each of the relational subtests. Throughout all subtests, training is delivered in the form of “rule statements.” For example, a Basic Symmetry item may involve a participant being given an arbitrary stimulus (A) and an array of two items (B), and then being provided the rule “This (A1), is the same as this (B1).” After providing the rule statement, the assessor would then provide an array of two comparison (A) stimuli and ask, “Which is the same as this (B1)?” where the correct response would involve pointing to A1. All relations assessed in the PEAK-E-PA are arbitrary to ensure that participants do not have a differential learning history with the stimuli. Stimuli are cross-modal, including visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, and tactile stimuli. The results of the PEAK-E-PA, in addition to providing a measure of each participants’ demonstration of derived arbitrarily applicable relations, are also used to determine which items on the PEAK-E-A will be directly tested, to develop individualized instructional programs for each participant.

Fig. 1.

Exemplar PEAK-E-PA item (Transitivity: Advanced Program 2; Dixon, 2015) providing a description of materials needed, instructions for assessment item administration, the correct participant answer, a field to show the participant answer, and checkboxes to indicate if the participant’s answer was correct

Table 1.

PEAK-E Preassessment Exemplar Items Across Each of the Relational Subtypes

Note. Dashed boxes represent visual stimuli, quotations represent vocal/auditory stimuli, and “C note” represents a musical C note. Filled cells show where training occurred

PEAK-E Assessment (PEAK-E-A)

The PEAK-E-A is a 184-item criterion-referenced assessment of participant skills, where the demonstration of each skill involves (a) learning through direct training of a relation or subset of relations and (b) deriving either reflexive, symmetrical, transitive, or equivalence relations, depending on the complexity of the assessment item. Items in the PEAK-E-A increase in complexity both in terms of the general complexity of the skill (e.g., addition will appear prior to multiplication regardless of the type of derived relation assessed) and in terms of the complexity of the derived relation necessary for demonstration of the skill (e.g., all reflexivity items are tested prior to testing symmetry items). Similar to the PEAK-E-PA, the assessor begins by delivering “rule statements” for each of the trained relations; for example, “(A) is the same as (B), and (B) is the same as (C).” After the delivery of the rule statements, the assessor then tests the participant’s demonstration of the trained and tested relations, where each relation is tested separately in five-trial blocks. If the participant demonstrates the correct response for at least 80% of the trials within each trial block, then the skill is considered mastered, and the assessor progresses to the next skill. The assessor will begin conducting the assessment at differing points based on the participant’s scores on the PEAK-E-PA. If participants score less than 12 on the Reflexivity subtest of the PEAK-E-PA, then the experimenter begins the PEAK-E-A at Item 1A. If participants scored 12 on the Reflexivity subtest and less than 12 on the Symmetry subtest of the PEAK-E-PA, then the experimenter begins the PEAK-E-A at Item 4B. If the participants scored 12 on both the Reflexivity and Symmetry subtests and scored less than 12 on the Transitivity subtest of the PEAK-E-PA, then the experimenter begins the PEAK-E-A at Item 9N. If the participants scored 12 on the Reflexivity, Symmetry, and Transitivity subtests of the PEAK-E-PA but less than 12 on the Equivalence subtest of the PEAK-E-PA, then the experimenter begins the PEAK-E-A at Item 10L. The criterion for discontinuing the assessment will vary across participants depending on the number of programs that are being conducted with a participant; in the context of the present study, the assessment was discontinued once the participants failed to demonstrate mastery of three skills.

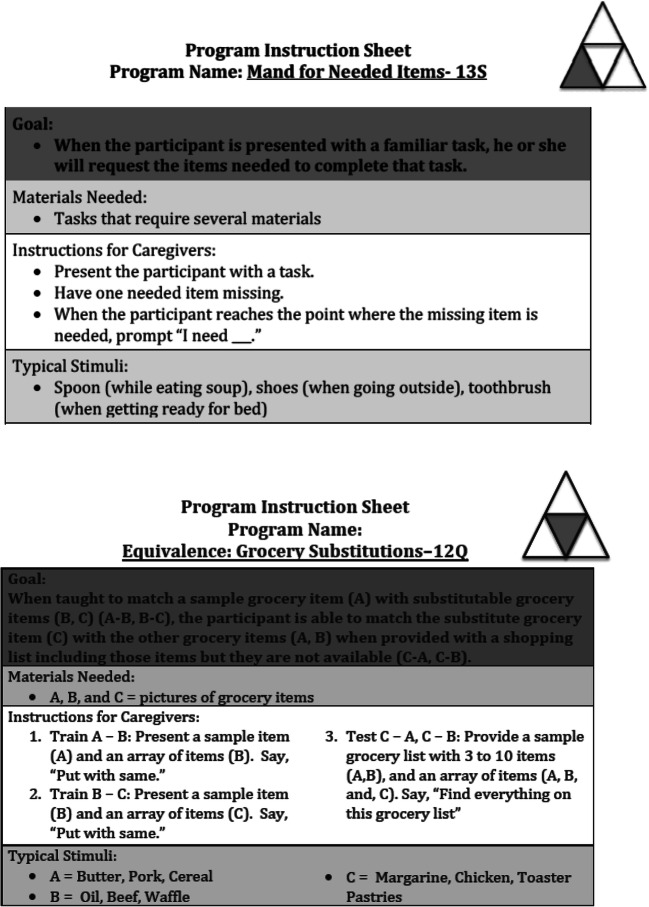

PEAK-E relational training (PEAK-E)

The PEAK-E curriculum includes a set of programs that provide instructions for how to teach unmastered skills identified in the PEAK-E-A. Each item on the PEAK-E-A has a corresponding program in PEAK-E. An example PEAK-E program is provided in Fig. 2. Each program is one page in length and provides a goal statement for the program, stimuli used in training and testing trials for the program, instructions for conducting the program, typical stimuli used to conduct the program, and a space for implementers to write stimuli for up to eight classes that will be used in training and testing. The goal statement has point-to-point correspondence with the description of the item provided in the PEAK-E-A. The stimulus description provides information regarding what stimuli are used in each program, corresponding with the alphabetical nomenclature typically used in relational training (e.g., A = food source, B = food item). The instructions provide the steps for (a) directly training necessary relations, where several different training arrangements are provided (e.g., match to sample, vocal communicative), and (b) testing derived relations, again using several different testing arrangements (e.g., go/no-go, match to sample). The typical stimuli section provides implementers with examples of stimuli that may be used (e.g., A = cow, pig, plant; B = steak, bacon, lettuce). Finally, the stimulus class table provides a place for implementers to write the stimuli that they will use when implementing the particular program, and is used to guide relational training and testing throughout program implementation. PEAK-E has data sheets that provide information regarding prompting level and skill mastery. It also contains instructions for promoting the emergence of derived relations when they do not occur in the absence of training (for more detail, see Dixon, 2015).

Fig. 2.

Exemplar PEAK-DT (top; Dixon, 2014a) and PEAK-E (bottom; Dixon, 2015) curricular programs including the goal statement, description of materials, implementation instructions, and typical stimuli used in conducting the program

Design and procedure

To start, each of the participants was assessed using the PEAK-E-PA to determine his or her derived reflexive, symmetrical, transitive, and equivalence relations. The results of the PEAK-E-PA were then used to determine which items on the PEAK-E-A to directly assess. Once three skills were identified as target skills on the PEAK-E-A, procedures described in the PEAK-E were implemented as described in the protocol to teach each of the target skills and test for derived relations. Following the conclusion of PEAK-E training, each of the participants was reassessed using the PEAK-E-A to determine if the mastered skills transferred to assessment stimuli and if the participants acquired new skills without being directly trained.

PEAK-E Preassessment (PEAK-E-PA)

The PEAK-E-PA was implemented at the onset of the study in order to determine which items on the PEAK-E-A to assess, and subsequently which skills to target during PEAK-E relational training. To conduct the PEAK-E-PA, the assessor followed the directions precisely as described in the PEAK-E-PA. All items on the PEAK-E-PA were assessed using the PEAK-E-PA Long Form assessment method to better ensure that the obtained results were indicative of the participants’ relational abilities. Therefore, the participants were given a score of 1 for each correct item and a score of 0 for each incorrect item. The assessors began the assessment at Basic Reflexivity 1 for all participants, and the assessment was discontinued once the participants achieved a score of 0 across five consecutive items. All stimuli used for each of the assessment items were those specified in the PEAK-E-PA. No alternative stimuli were used for any of the assessment items. Participant scores on the PEAK-E-PA were then used to determine the starting point for each participant on the PEAK-E-A.

PEAK-E Assessment (PEAK-E-A)

The PEAK-E-A was implemented and evaluated at the onset and conclusion of the study in an uncontrolled pre-post experimental design. The skills that were assessed were determined based on the participants’ scores on the PEAK-E-PA. To conduct the PEAK-E-A, the experimenter evaluated each of the PEAK-E-A items in five-trial blocks. Two stimulus classes were included in each test item (e.g., two different pictures were used when testing the Reflexivity: Pictures program). The experimenter alternated between trials of the train and test relations across both classes, where each relation was tested five times in a block and the stimuli presented for each trial were randomized. If the participant demonstrated the correct response specific to each item for 80% or more of the trials, the skill was considered mastered, and the experimenter progressed to the next item on the PEAK-E-A. Items were assessed in descending order based on the progression of the items in the assessment (e.g., 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, etc.). The experimenter continued the assessment until the participant failed to demonstrate mastery of three skills. Those three skills were then targeted through PEAK-E instruction. The stimuli used in the PEAK-E-A were different from those used during PEAK-E instruction training, so the post-PEAK-E-A evaluation also served as a demonstration of a transfer of the skill to novel, untrained stimuli.

PEAK-E instruction (PEAK-E)

Training conducted in the current study was implemented as described in the PEAK-E curriculum, and the efficacy of the procedures was assessed in a multiple-baseline across-skills experimental arrangement with an embedded multiple probe of test relations, replicated across each of the 11 participants. Three programs were implemented for each participant based on his or her results on the PEAK-E-PA and PEAK-E-A. For each program, three classes were targeted, and the number of class members ranged from two to five, depending on the complexity of the target program. A baseline phase was implemented to determine if the participants could demonstrate the target skills prior to PEAK-E instruction. The procedures in baseline were identical to the procedures used during instruction, except differential consequences were not delivered following correct or incorrect responses. Training was implemented in increasing complexity based on the progression of the training programs in PEAK-E (i.e., programs that appeared earlier in PEAK-E were conducted first). For example, if programs 2A, 5B, and 5E were targeted, training would be introduced in that respective order (i.e., training was introduced on program 2A first and 5E last). Baseline phases were staggered across the three programs, and participants did not progress from the baseline phase into the training phase until a stability criterion was achieved in baseline. The stability criterion was two two consecutive data points in the train trial block within 10% of the mean of those two data points. For Tim, Clara, Jace, Rob, Joe, and Jillian, all trial blocks consisted of 5 trials. For Sam, Kris, Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd, all trial blocks consisted of 10 trials. The number of trial blocks differed across participants to increase the external validity of the procedures. For the first eight participants, if there were multiple trained relations (e.g., train A-B and A-C) and/or multiple test relations (e.g., test A-D and D-A), then these relations were equally presented within a given trial block in an alternating fashion. For example, if the program required training of both A-B and B-C relations, then trials within a train trial block alternated between A-B and B-C. For Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd, only a single relation was targeted within each block. For example, if a program required training of both A-B and A-C relations, both relational types were trained exclusively in two trial blocks. This different structure was used with these three participants to provide further detail as to which relations were specifically mastered during the PEAK instruction phase. In addition, PEAK-E instruction was replicated with a second set of three stimuli with these participants to increase confidence in the obtained results.

During train trial blocks in the PEAK-E instruction phase, participants were provided access to their identified preferred items contingent on demonstration of a correct response, or they were provided least-to-most intrusive prompts to evoke the correct response when they demonstrated an incorrect response. For train trials where the participant response was vocal, participants were provided a verbal prompt following the first error (e.g., “Try again.”) and were provided a model of the correct answer following the second error (e.g., “Say yes.”). For train trials where the participant response was match to sample or involved another physical movement (e.g., pointing, engaging in an activity), the participants were provided a verbal prompt following the first error (e.g., “Not that one. Try again.”), a gestural prompt following the second error (i.e., the implementer pointed to the correct comparison stimulus), and a physical prompt following the third error. No preferred items nor prompts were delivered following participant responses during the test trial blocks in both the baseline and training phases. A mastery criterion was set at two or more consecutive train trial blocks at an average of 90% response accuracy and two consecutive test trial blocks at an average of 90% response accuracy. Both criteria had to be met for the skill to be considered mastered. The trained and tested relations specific to each program for each of the participants are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Program Names, Stimulus Types, and Train and Test Relations for Each of the Target Skills Across Participants

| Program / Participant | Stimulus Type | Train Relations | Test Relations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tim | |||

| 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources | A = food sources; B = food items | A-B | B-A |

| 7H – Symmetry: Synonyms | A = vocal words; B = synonyms for vocal words | A-B | B-A |

| 7I – Symmetry: Body Parts Game | A = body part names; B = synonyms | A-B | B-A |

| Clara | |||

| 1B – Reflexivity: Textual Matching | A = textual words; B = identical textual words | A-B | B-A |

| 2A – Reflexivity: Pictures | A = pictures; B = identical pictures | A-B | B-A |

| 2B – Reflexivity: Objects | A = objects; B = identical objects | A-B | B-A |

| Jace | |||

| 5D – Symmetry: Tacting Letters | A = textual letters; B = vocal letter names | A-B | B-A |

| 6G – Symmetry: Phonetic Blends and Digraphs | A = vocal phonetic blends or digraphs; B = textual phonetic blends or digraphs | A-B | B-A |

| 7I – Symmetry: Body Parts Game | A = vocal body part names; B = synonyms for body parts | A-B | B-A |

| Rob | |||

| 8E – Symmetry: Proverbs | A = vocal proverb; B = vocal meaning | A-B | B-A |

| 8G – Symmetry: Basic Algebra | A = textual numbers; B = textual letters; C = textual math problems | A-B (solve C with A stimuli) | B-A (solve C with B stimuli) |

| 8H – Symmetry: Conjunctive Logic | A = vocal person’s name; B = vocal noun; C = vocal context | CA1-B1; CA2-B2 | CB1-A1; CB2-A2 |

| Joe | |||

| 13U – Equivalence: Leisure Activities | A, B, C = vocal leisure activities; D = vocal situations | D-A; A-B; A-C | B-D; C-D |

| 13X – Equivalence: What Does It See? | A = vocal settings; B = vocal animals; C = vocal objects | A-B; A-C | B-C |

| 14D – Equivalence: Rules-Actions-Functions | A, B, C = modeled actions; D = vocal actions | D-A; A-B; A-C | D-A; D-B; D-C |

| Jillian | |||

| 14E – Equivalence: SD Function (Pre-class) | A, B, C = vocal arbitrary words; D = modeled actions | A-D; A-B; B-C | B-D; C-D |

| 14F – Equivalence: SD Function (Post-class) | A, B, C = vocal arbitrary words; D = modeled actions | A-B; B-C; A-D | B-D; C-D |

| 14Q – Equivalence: Context and Tracks | A = vocal activities; B, C = vocal outcomes; D, E = vocal conditions | DA-B; EA-C | AB-D; AC-E |

| Kris | |||

| 5A – Symmetry: Picture to Textual | A = pictures; B = textual stimuli | A-B | B-A |

| 5B – Symmetry: Translation | A = native word; B = foreign word | A-B | B-A |

| 5C – Symmetry: Textual Number Identification | A = textual numbers; B = pictures with a number of items | A-B | B-A |

| Sam | |||

| 5B – Symmetry: Translation | A = native word; B = foreign word | A-B | B-A |

| 6I – Symmetry: Auditory to Syllables | A = auditory sound; B = syllable text | A-B | B-A |

| 6J – Symmetry: Sight Reading | A = vocal words; B = textual words | A-B | B-A |

| Lucy | |||

| 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources | A = food sources; B = food items | A-B | B-A |

| 5B – Symmetry: Translation | A = native word; B = foreign word | A-B | B-A |

| 6A – Symmetry: Simple Geometry | A = vocal shape feature; B = vocal name | A-B | B-A |

| Lawton | |||

| 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources | A = food sources; B = food items | A-B | B-A |

| 5A – Symmetry: Picture to Textual | A = picture; B = written word | A-B | B-A |

| 5B – Symmetry: Translation | A = textual numbers; B = pictures with a number of items | A-B | B-A |

| Ladd | |||

| 9N – Transitivity: Representing Numbers | A = number of items; B = textual numbers; C = textual Roman numerals | A-B; B-C | A-C |

| 10E – Transitivity: Intraverbals and Idioms | A = vocal question; B = vocal answer; C = vocal idiomatic expression | A-B; B-C | A-C |

| 10F – Transitivity: Informational Resources | A = vocal question; B = vocal name of informational resource; C = picture of informational resource | A-B; B-C | A-C |

Note. Information was taken from the PEAK-E curriculum (Dixon, 2015)

Dependent variables and interobserver agreement

There were several variables that were analyzed in the current study. First, participant results on the PEAK-E-PA were analyzed both in terms of PEAK-E-PA total score (range 0–48) and in terms of component scores across the Reflexivity, Symmetry, Transitivity, and Equivalence subtests (range 0–12 for each component). Interobserver agreement (IOA) was evaluated by having two independent observers score the participants’ responses simultaneously during the assessment. To determine IOA for the PEAK-E-PA, the number of items in which the observers provided the same score was divided by the total number of items, then multiplied by 100:

Second, participant performance during baseline and PEAK-E training was evaluated as a percentage of correct independent responding during 5 or 10 trial blocks. PEAK scores (the scoring metric typically used in the PEAK-E curriculum in clinical settings) were not reported to remain consistent with previous studies on relational training procedures. For Tim, Clara, Jace, Rob, Jillian, and Joe, percentage correct values that were multiples of 20 were possible. For Kris, Sam, Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd, percentage correct values that were multiples of 10 were possible. IOA was assessed by dividing the number of trial blocks in which the observers provided the same score by the total number of trial blocks, then multiplying by 100 (IOA = [agreements/disagreements] × 100).

Results and Discussion

PEAK-E Preassessment (PEAK-E-PA)

The results of the PEAK-E-PA conducted with each of the 11 participants at the onset of the study generated differentiated results across the participants, with a mean PEAK-E-PA total score of 16.3 (34%, SD = 10.8). Mean scores on the Reflexive, Symmetrical, Transitive, and Equivalence subtests were 8.7 (72.5%, SD = 4.0), 5.9 (49.2%, SD = 4.6), 1.5 (12.5%, SD = 3,7), and 0.2 (1.7%, SD = 0.6), respectively. Participant total scores ranged from 1 to 38, suggesting that the assessment was appropriate for each of the participants, as scores of 0 (i.e., floor effect) and 48 (i.e., ceiling effect) were not achieved. Tim’s PEAK-E-PA total score was 9 (6 Reflexivity, 3 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), suggesting that he could demonstrate mastery of basic and intermediate reflexive relations and some basic symmetrical relations. Examples of mastered relations included identity matching, cross-modal sequential matching, and visual symmetrical match-to-sample tasks. Mastery of zero relational skills on the PEAK-E-A was therefore assumed, and testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 1A. Clara’s PEAK-E-PA total score was 11 (5 Reflexivity, 6 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence). She demonstrated mastery of basic and intermediate reflexive and symmetrical relational skills (e.g., cross-modal symmetrical match-to-sample tasks), and testing on the PEAK-E-A also began at Item 1A. Jace achieved a PEAK-E-PA total score of 11 (7 Reflexivity, 4 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), suggesting mastery of basic and intermediate reflexive relations, as well as basic symmetrical relations. Testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 1A. Rob’s PEAK-E-PA total score was 14 (12 Reflexivity, 2 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), suggesting mastery of all reflexive relations (e.g., cross-modal sequential presentation and match-to-sample tasks) and some basic symmetrical relations, and testing began at Item 4B. Joe achieved a PEAK-E-PA total score of 28 (12 Reflexivity, 12 Symmetry, 4 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), suggesting mastery of all reflexive and symmetrical relations, as well as basic transitive relations (e.g., visual match-to-sample tasks). PEAK-E-A testing began at Item 9N. Jillian achieved a PEAK-E-PA Total Score of 38 (12 Reflexivity, 12 Symmetry, 12 Transitivity, 2 Equivalence), suggesting mastery of all reflexive, symmetrical, and transitive relations (e.g., cross-modal match to sample and sequential reasoning), as well as basic equivalence relations (e.g., auditory and visual match-to-sample tasks). Testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 10L. Kris’s PEAK-E-PA total score was 5 (5 Reflexivity, 0 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), showing mastery of basic and some intermediate reflexive relations, and testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 1A. Sam’s PEAK-E-PA total score was 1 (1 Reflexivity, 0 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), showing mastery of only a single reflexive relation. Testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 1A. Lucy achieved a PEAK-E-PA total score of 18 (12 Reflexivity, 6 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), showing mastery of all reflexive relations, as well as basic and several intermediate symmetrical relations. Testing on PEAK-E-A began at Item 4B. Lawton achieved a PEAK-E-PA total score of 20 (12 Reflexivity, 8 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, Equivalence), showing mastery of all reflexive relations, as well as basic and intermediate symmetrical relations. Testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 4B. Finally, Ladd’s PEAK-E-PA Total Score was 24 (12 Reflexivity, 12 Symmetry, 0 Transitivity, 0 Equivalence), suggesting mastery of all reflexive and symmetrical relations, and testing on the PEAK-E-A began at Item 9N. Taken together, six of the participants (Rob, Joe, Jillian, Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd) demonstrated mastery of reflexivity, three demonstrated mastery of symmetry (Joe, Jillian, and Ladd), one demonstrated mastery of transitivity (Jillian), and none of the participants demonstrated mastery of equivalence. IOA was conducted for 27.3% of the assessments, generating an IOA value of 100%.

PEAK-E Assessment (PEAK-E-A)

The PEAK-E-A was conducted on two occasions: at the beginning of the study and following PEAK-E instruction. As noted previously, five of the participants (Tim, Clara, Jace, Kris, and Sam) began the PEAK-E-A at Item 1A, three (Rob, Lucy, and Lawton) at Item 4B, two (Joe and Ladd) at Item 9N, and one (Jillian) at item 10L. These starting points were held constant at both measurement periods and were generated from participants’ initial results on the PEAK-E-PA. The PEAK-E-A was discontinued once participants failed to demonstrate mastery of three target items. Unmastered programs were not required to be consecutive. During the initial PEAK-E-A assessment, Tim mastered 37 items and failed to demonstrate mastery of the following items: 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources, 7H – Symmetry: Synonyms, and 7I – Symmetry: Body Parts Game. Therefore, these three items served as instructional targets in the following phase. Clara mastered 1 item and failed to demonstrate mastery of the following items: 1A – Reflexivity: Textual Matching, 2A – Reflexivity: Pictures, and 2B – Reflexivity: Objects. Jace mastered 37 items but did not demonstrated mastery of the following items: 5D – Symmetry: Tacting Letters, 6G – Symmetry: Phonetic Blends and Digraphs, and 7I – Symmetry: Body Parts Game. Rob mastered 40 items and failed to master the following items: 8E – Symmetry: Proverbs, 8G – Symmetry: Basic Algebra, and 8H – Symmetry: Conjunctive Logic. Joe demonstrated mastery of 88 items but did not master the following items: 13U – Equivalence: Leisure Activities, 13X – Equivalence: What Does It See? and 14D – Equivalence: Rules-Actions-Functions. Jillian mastered 87 items and failed to master the following items: 14E – Equivalence: SD Functions (Pre-class), 14F – Equivalence: SD Functions (Post-class), and 14Q – Equivalence: Context and Tracks. Kris mastered 14 items but failed to demonstrate mastery of the following items: 5A – Symmetry: Picture to Textual, 5B – Symmetry: Translation, and 5C – Symmetry: Textual Number Identification. Sam demonstrated mastery of 29 items and did not master the following items: 5B – Symmetry: Translation, 6I – Symmetry: Auditory to Syllables, and 6J – Symmetry: Sight Reading. Lucy mastered 10 items and did not demonstrate mastery of the following items: 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources, 5B – Symmetry: Translations, and 6A – Symmetry: Simple Geometry. Lawton demonstrated mastery of 3 items but did not demonstrate mastery of the following items: 4E – Symmetry: Food Sources, 5A – Symmetry: Picture to Textual, and 5B – Symmetry: Translations. Finally, Ladd mastered 6 items and failed to demonstrate mastery of the following items: 9N – Transitivity: Representing Numbers, 10E – Transitivity: Intraverbals and Idioms, and 10F – Transitivity: Informational Resources. The highlighted items served as individualized targets during PEAK-E instruction. The total number of unique target skills was 26, representing 14% of the complete PEAK-E curriculum. There was, however, a greater distribution of target items in the first half of the assessment (76.9%) compared to the second half of the assessment (23.1%), suggesting that earlier programs may have been disproportionately represented in the sample, a result of the individualized assessment results. IOA was conducted for 36.4% of the assessments, generating an IOA value of 95%.

PEAK-E instruction (PEAK-E)

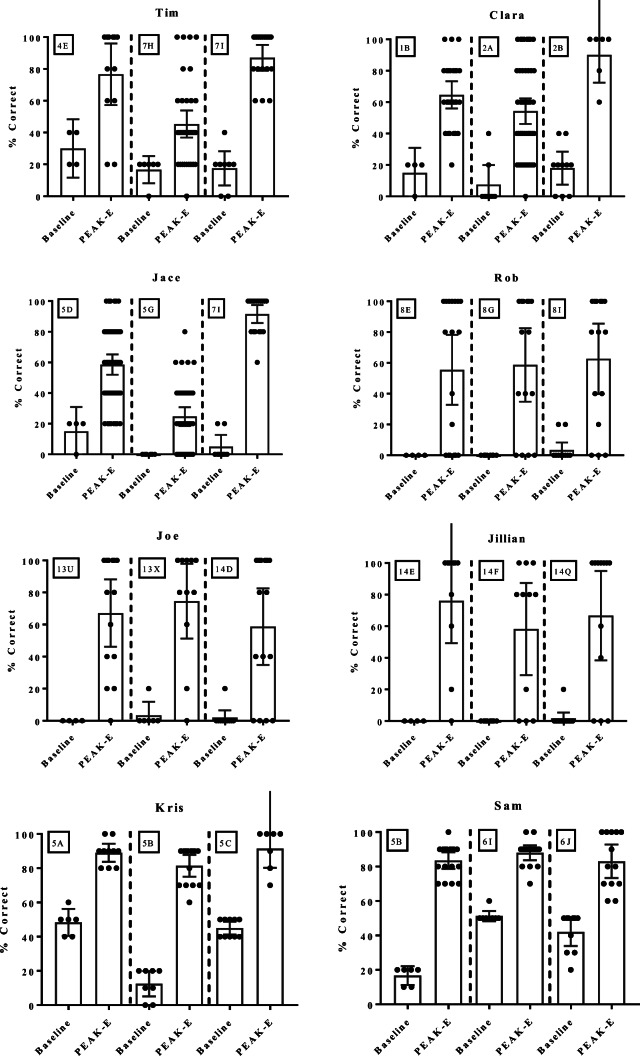

The target skills for PEAK-E instruction were selected based on the participants’ results on the PEAK-E-PA and the PEAK-E-A. Baseline and training performance aggregated across both train and test relations is summarized in a scatter dot plot in Fig. 3 (Tim, Clara, Jace, Rob, Joe, Jillian, Kris, and Sam). Mean performance is shown in the baseline and PEAK-E instructional bar graphs, and individual data points are plotted. These data show that the mean percentage of correct responding for each of the eight participants was greater during PEAK-E instruction compared to baseline phases. Additionally, there was greater variability during PEAK-E instruction. During training, Tim’s mean percentage correct increased from 20% (range 0%–40%) across all baselines to 61.8% (range 0%–100%) across all training conditions; Clara increased from 13.6% (range 0%–40%) to 56.5% (range 0%–100%); Jace increased from 5.6% (range 0%–20%) to 51.2% (range 0%–100%); Rob increased from 1.7% (range 0%–20%) to 58.8% (range 0%–100%); Joe increased from 2% (range 0%–20%) to 6% (range 0%–100%); Jillian increased from 0.8% (range 0%–20%) to 66.7% (range 0%–100%); Kris increased from 35% (range 0%–60%) to 86.1% (range 60%–100%); and Sam increased from 38.8% (range 10%–60%) to 84.9% (range 60%–100%). The percentage of nonoverlapping data (PND) was calculated for each of the 24 programs (3 programs × 8 participants = 24 total programs) and was determined by dividing the number of data points in the instructional phase that were above the highest data point in the corresponding baseline phase by the total number of data points in the instructional phase, and then multiplying by 100. Across the 24 programs, effect sizes included ineffective (i.e., PND < 50%; 1 program), minimally effective (i.e., PND between 50% and 70%; 1 program), moderately effective (i.e., PND between 70% and 90%; 10 programs), and highly effective (i.e., PND above 90%; 12 programs) outcomes. Therefore, the greatest proportion of programs was considered highly effective (50%) or moderately effective (41.7%). The mean PND across the eight participants was 85.9% (Tim, 85.4%; Clara 81%; Jace, 85.3%; Rob, 71.1%; Joe, 83.3%; Jillian, 80.9%, Kris, 100%; and Sam, 100%).

Fig. 3.

Scatter dot plots representing participant scores in baseline and during PEAK-E instruction across each of the three programs. Each dot represents a trial block, bars represent mean percentage correct, and error bars represent 95% confidence interval

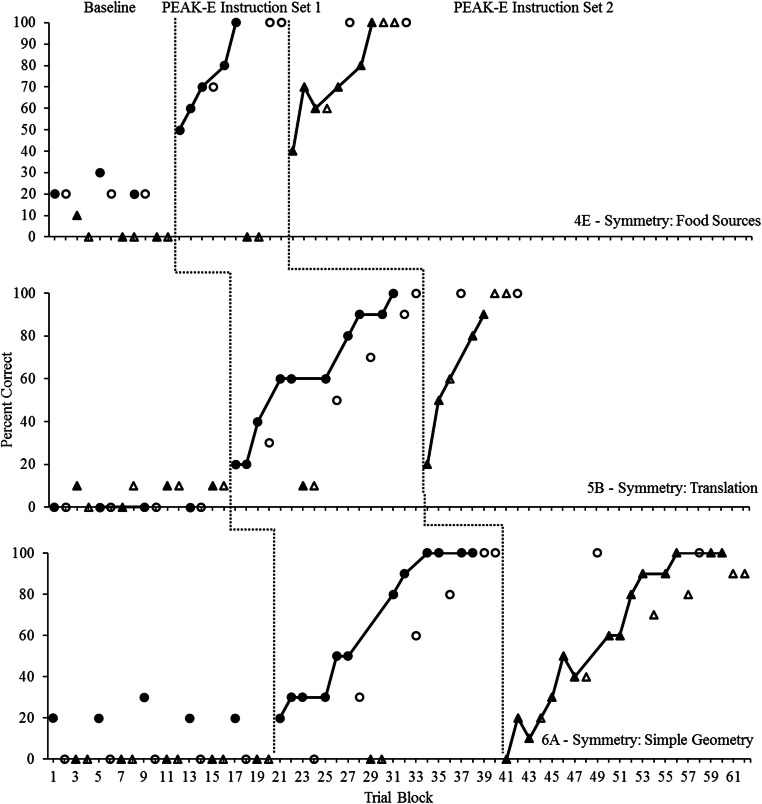

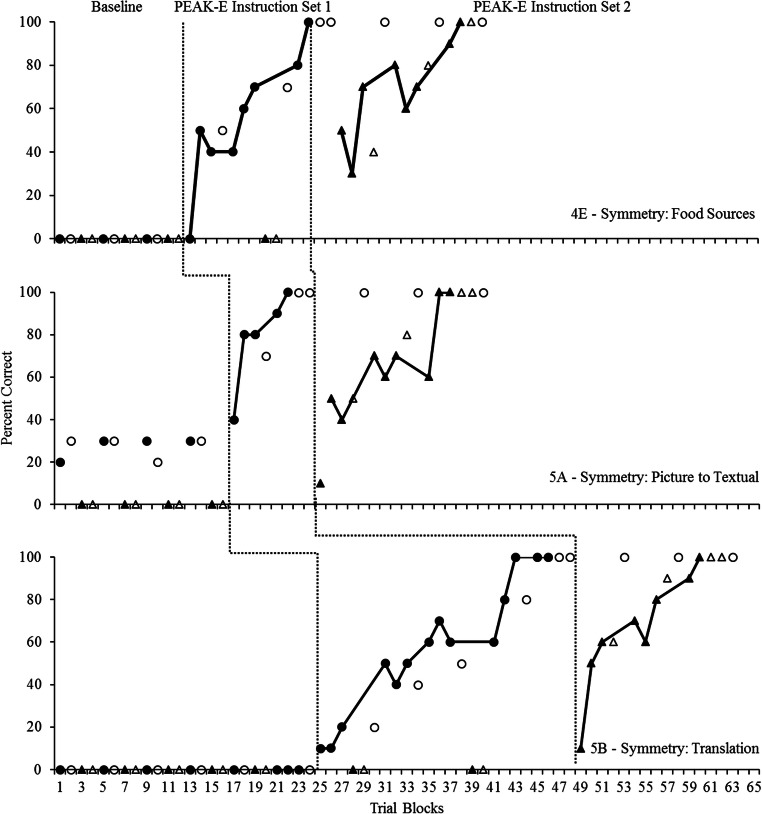

Two sets of stimuli were trained separately to replicate the efficacy of the PEAK-E instructional procedures for Lucy, Lawton, and Ladd, and their results are displayed in Figs. 4, 5, and 6. In baseline, Lucy (Fig. 5) failed to demonstrate mastery of any of the train (A-B) or test (B-A) relations across the three target programs, and this finding was consistent across both stimulus sets. Her mean baseline percentage correct was 10% (range 0%–30%) for Stimulus Set 1 and 2.9% (range 0%–10%) for Stimulus Set 2. In the instructional phase for Stimulus Set 1, Lucy’s mean percentage correct for Set 1 increased to 66.8% (range 0%–100%), and the mastery criterion was achieved for both the train and test relations for all targets. Train and test relations for Stimulus Set 2 remained at or below baseline levels. In the instructional phase for Stimulus Set 2, Lucy’s mean percentage correct increased to 66.7% (range 0%–100%), and the mastery criterion was again met for all train relations and two of the three test relations. The mastery criterion was not met for the test relations for Item 6A – Symmetry: Simple Geometry, with a mean percentage correct of 80% in the final two test trial blocks in this phase. The test relations for Stimulus Set 1 maintained during instruction for Stimulus Set 2. For Lawton (Fig. 6), baseline results again indicate that he was unable to demonstrate mastery of the train (A-B) and test (B-A) relations for both Stimulus Set 1 (M = 9.2%; range 0%–30%) and Stimulus Set 2 (M = 0%). In the instructional phase for Set 1, Lawton’s mean percentage correct increased to 50.1% (range 0%–100%), and he achieved the mastery criterion for train and test relations. A corresponding increase in correct responding for train and test relations for Stimulus Set 2 was not observed. In the instructional phase for Stimulus Set 2, Lawton’s mean percentage correct again increased to 70.3% (range 10%–100%), and he met the mastery criterion for all three programs. Correct responding was maintained for Stimulus Sets 1. Ladd (Fig. 6) failed to demonstrate mastery of most train (A-B and B-C) and test (A-C) relations in baseline for Stimulus Sets 1 (M = 12.5%; range 0%–100%) and 2 (M = 19.4%; range 0%–100%); however, he did demonstrate mastery of the A-B relations for both stimulus for Item 9N – Transitivity: Representing Numbers. He did not demonstrate the other trained relation for this program (B-C) nor the derived transitive relation (A-C) for either of the stimulus sets in baseline. In the instructional phase for Stimulus Set 1, Ladd’s mean percentage correct for Set 1 increased to 83.4% (range 0%–100%), and he met the mastery criteria for train and test relations. His percentage correct did not increase for Stimulus Set 2. In the instructional phase for Stimulus Set 2, Ladd’s mean percentage correct again increased to 90% (range 60%–100%), the mastery criterion was met for all three target programs, and correct responding maintained for the transitive A-C relation for Stimulus Set 1 during this phase. Tau-U analyses were conducted across each of the participants to determine the effect size and the probability that the obtained results occurred by chance. Contrast analyses for the baseline conditions suggested that no corrections were required for subsequent analyses. The results of weighted Tau-U analyses across each of the participants indicated large effect sizes (Lucy, 0.93; Lawton, 0.96; and Ladd, 0.85), and all results were again significant at the 0.01 level.

Fig. 4.

Multiple-baseline across-skills design for Lucy. Closed circles show the train (A-B) relations for Stimulus Set 1, and open circles show the test (B-A) relations for Stimulus Set 1. Closed triangles show the train (A-B) relations for Stimulus Set 2, and open triangles show the test (B-A) relations for Stimulus Set 2. Data paths indicate where training occurred

Fig. 5.

Multiple-baseline across-skills design for Lawton. Closed circles show the train (A-B) relations for Stimulus Set 1, and open circles show the test (B-A) relations for Stimulus Set 1. Closed triangles show the train (A-B) relations for Stimulus Set 2, and open triangles show the test (B-A) relations for Stimulus Set 2. Data paths indicate where training occurred

Fig. 6.

Multiple-baseline across-skills design for Ladd. Closed circles (A-B) and closed squares (B-C) show the train relations for Stimulus Set 1, and open circles show the test (A-C) relations for Stimulus Set 1. Closed triangles (A-B) and closed diamonds (B-C) show the train relations for Stimulus Set 2, and open triangles show the test (A-C) relations for Stimulus Set 2. Data paths indicate where training occurred

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 demonstrated that, with few exceptions, the participants demonstrated mastery of trained and derived relations across reflexive, symmetrical, and transitive relational categories, consistent with prior research in stimulus equivalence. These results extend this research by suggesting that the assessments contained in PEAK-E can be used to develop equivalence-based instruction that will lead to meaningful skill acquisition across participants, all of whom vary in their preexperimental relational response histories and degrees of intellectual impairment. Indeed, given the varied nature of neurodegenerative disorders consistent with autism, such an assessment contains immediate social validity in application with this population. In addition, we showed that individualized equivalence-based instruction can lead to the acquisition of several socially valid skills for children with autism.

As noted by several authors (e.g., Hayes et al., 2001), however, stimulus equivalence describes an outcome, where the process that gives rise to such an outcome needs to be ascertained. In the context of the current study, the PEAK-E-PA suggested that participants could already derive any or all of the reflexive, symmetrical, or transitive relations, which guided the selection of programs in PEAK-E, and that participants could undoubtedly master given their preexperimental relational histories. Thus, it should come as no surprise that when subsets of relations were directly taught, the participants also demonstrated the accompanying derivations. The true utility of using a standardized equivalence-based curriculum may be in that, when several of these programs are conducted over an extended period (i.e., more than the three programs in Experiment 1), the programs serve as multiple exemplars that improve the complexity of derived relational responding as a higher order generalized operant response class. Several authors have suggested that derived responding may emerge through multiple-exemplar instruction (e.g., Healy et al., 2000), but this assertion remains relatively untested. In Experiment 2 of the present study, we sought to provide a preliminary investigation of the role of multiple-exemplar instruction, guided by PEAK-E, in improving derived relational responding across individuals with autism as a generalized operant class. The PEAK-E-PA provides a psychometric measure of relational responding. Therefore, we conducted several programs from the PEAK-E system with two children with autism and intermittently probed for improvements in relational responding, all over the course of just under 9 months. These improvements were compared to a verbal operant training baseline and to derived relational responding exhibited by a third control subject who never underwent exemplar equivalence instruction. If improvements in relational responding were observed, corresponding with the implementation of equivalence-based programs such as those shown in Experiment 1, then this would provide some of the first evidence of derived relational responding as an outcome that emerges as a generalized operant through multiple-exemplar instruction. Our intention is to provide an initial demonstration in this capacity.

Experiment 2: Examining the Emergence of Derived Relational Responding as a Generalized Operant

Method

Participants and setting

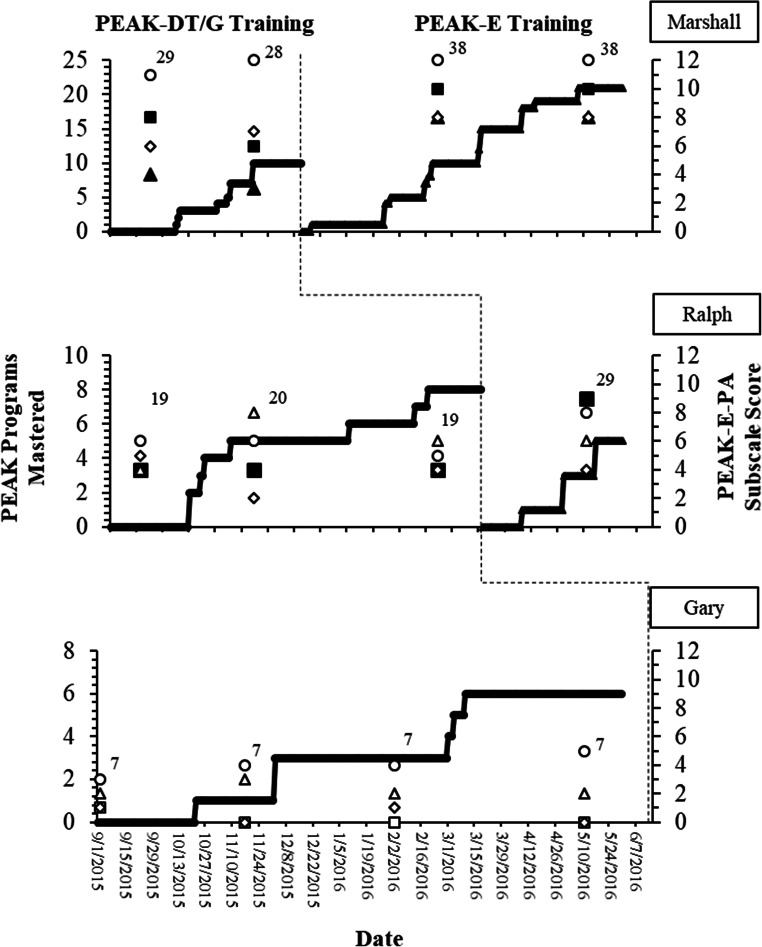

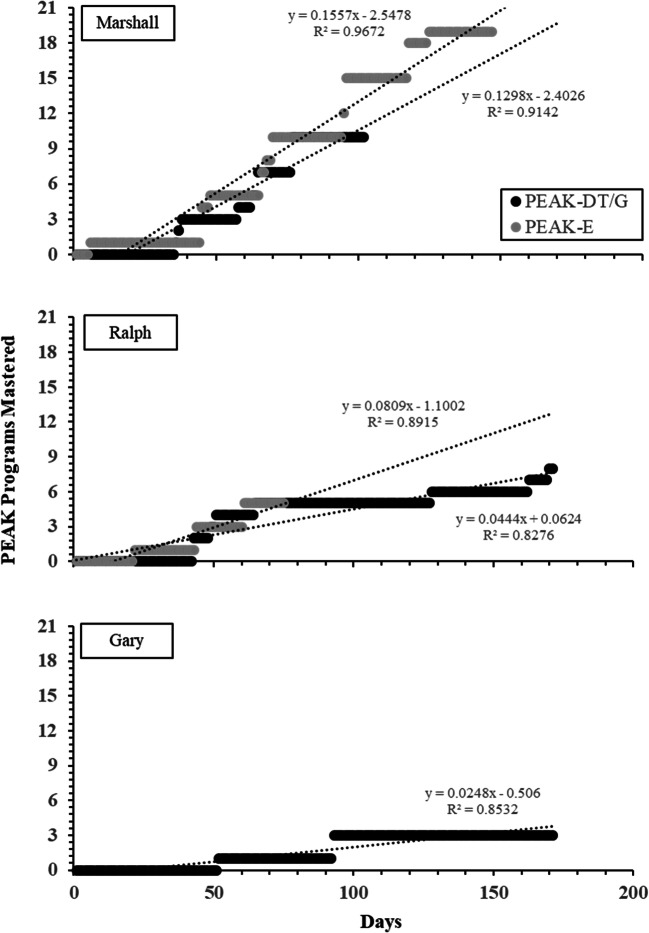

Participants were three males, aged 10 to 11 years, and all had a diagnosis of autism with no other diagnoses at the time of the current study. The participants attended an ABA-based school program specialized for individuals with autism and related disabilities. They were referred to the school due to academic delays and behavior challenges impeding academic functioning. Although each of the participants demonstrated challenging behaviors, no challenging behaviors were observed while trials and test probes were conducted in the current study. ABA-based instruction at the school was consistent with a Skinnerian-based framework of language development, guided by the PEAK-DT and PEAK-G protocols. The participants were actively completing 5–10 programs each day at the time of the study. All PEAK programs were discontinued for the purposes of the study, where ABA language instruction included only the programs that were prescribed as part of the current study. None of the participants had prior experience with programs from the PEAK-E protocol. PEAK-DT, PEAK-G, and PEAK-E-PA assessments were conducted at the onset of the current investigation.

Marshall. Marshall (age 10) had a PEAK-DT total score of 150, which corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 7 to 8 years based on the normative sample reported by Dixon et al. (2014a), and a PEAK-G total score of 61, which also corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 7 to 8 years based on the normative sample reported by Dixon, Rowsey, Gunnarsson, Belisle, Stanley, & Daar, (2017d). Marshall’s PEAK-E-PA assessment suggested that he could demonstrate basic, intermediate, and advanced reflexive relations, as well as basic and intermediate symmetrical relations. He was unable to demonstrate cross-modal symmetrical relations, nor any transitive or equivalence relations.

Ralph. Ralph (age 10) had a PEAK-DT total score of 102, which corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 5 to 6 years, and a PEAK-G total score of 37, which corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 3 to 4 years. Ralph’s PEAK-E-PA assessment suggested that he could demonstrate basic and intermediate reflexivity, as well as basic symmetry. He was unable to demonstrate cross-modal symmetrical relations, sequentially presented symmetrical relationships, nor any transitive or equivalence relations.

Gary. Gary (age 11) had a PEAK-DT total score of 80, which corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 3 to 4 years, and a PEAK-G total score of 37, which also corresponds with an age equivalent of at least 3 to 4 years. Gary’s PEAK-E-PA assessment suggested that he could demonstrate basic reflexive and symmetrical relations. He was unable to demonstrate cross-modal symmetrical relations, sequentially presented symmetrical relations, nor any transitive or equivalence relations.

Setting. Sessions in the current study took place in the participants’ home classrooms, in an area away from the other students in the room to avoid distractions. Training areas consisted of a single table and two chairs. Training sessions lasted between 30 min and 1 hr each day. PEAK-E-PA assessment test probes were conducted in the same location as the training sessions.

Materials

PEAK Relational Training System

Three protocols from the PEAK Relational Training System were used in the present study: PEAK-DT, PEAK-G, and PEAK-E. Each of the protocols contains assessments that provide a measure of participants’ verbal operant skills (PEAK-DT and PEAK-G) or a measure of participants’ deriving of reflexive, symmetrical, transitive, and equivalence relations (PEAK-E). For each of the assessments, materials included those specified within each item in the assessment, such as common picture stimuli (e.g., pictures of animals) and common objects (e.g., preferred toys), and for the PEAK-E-A, additional materials included various tactile (e.g., sandpaper), olfactory (e.g., scented candles), and gustatory (e.g., preferred candy) stimuli. Materials for the corresponding PEAK-DT, PEAK-G, and PEAK-E programs were the same materials that were used in each of the assessments. In addition, preferred edible and tangible objects were used to reinforce correct responding during training, guided by the PEAK-DT and PEAK-G protocols in baseline and the PEAK-E protocol in the training phase. Classroom staff identified preferred objects at the beginning of each work period, which were delivered contingent on correct responding during the study and included small edible items such as pretzels, candy, or crackers, as well as manipulatable tangible objects such as toy cars, spinning tops, or stuffed animals. A formal preference assessment was not conducted during the present study.

PEAK-E Preassessment (PEAK-E-PA)

The same PEAK-E-PA assessment and materials that were used in Experiment 1 were used in Experiment 2 of the present study. The assessment, however, was administered on multiple occasions with each of the participants throughout the study to evaluate changes in derived relational responding corresponding with the training method utilized (i.e., traditional or equivalence-based instruction).

Design and procedure

A multiple-baseline across-subjects design with an embedded multiple probe of derived relational responding was used in the present study. The baseline phase in the present study was a training baseline guided by the PEAK-DT and PEAK-G protocols. We elected to use a training baseline in the present study to simulate training conditions that are typically used in ABA language instruction. Specifically, baseline involved instruction that was based on traditional, direct-reinforcement-centered instructional strategies as described in PEAK-DT and PEAK-G. By using a training baseline approach, the baseline condition had the same look and feel throughout all phases of the study in that participants were always receiving instruction, where the instructional approach was the independent manipulation. Prior research has supported the use of these protocols in establishing directly trained and generalized verbal skills in individuals with autism (Dixon, Peach, Daar, & Penrod, 2017c; McKeel et al., 2015). All procedures were conducted by trained classroom staff (teachers and paraprofessionals), simulating an environment in which curricula such as PEAK may be used. Implementers had attended at least 3 hr of workshop-based instructional training in a behavioral skills training model, had received in situ feedback and modeling from the first author and developer of PEAK, and had been implementing PEAK assessments and training for at least 4 months prior to the present study.

The training phase in the present study was guided by the PEAK-E relational training protocol, which utilizes equivalence-based training technologies. Prior research has supported the use of PEAK-E in promoting the emergence of socially significant derived relations as well, such as common academic skills (Dixon, Belisle, Stanley, Daar, & Williams, 2016a), categorization and emergent intraverbals (Dixon, Belisle, Stanley, Daar, & Williams, 2016a, Dixon et al., 2017b, Dixon, Belisle, Stanley, Speelman, Rowsey, Kime, & Daar, 2016b), and cross-modal gustatory relations (Dixon et al., 2017b), which highlight the efficacy of single programs taken directly from PEAK-E with individuals with autism. To date, however, research has not evaluated whether promoting the untrained emergence of these socially relevant derived relations leads to improvements in derived relational responding more generally, as indicated on the PEAK-E-PA.

The study was conducted over the course of 8 months, 25 days, corresponding to the regular school year. Assessment probes were conducted at 22 days; 2 months, 10 days; 5 months, 22 days; and 8 months, 12 days, where the introduction of the PEAK-E training phase was staggered across two of the participants (Marshall and Ralph). The remaining participant, Gary, served as a control subject, where PEAK-E training was never implemented to determine if stable results on the PEAK-E-PA would persist if derived relational training procedures were never introduced. The procedures specific to each phase of the study are described in the following sections.

PEAK-DT/PEAK-G training baseline

In baseline, participant instruction was guided by the PEAK-DT and the PEAK-G protocols. Both protocols contain a 184-item assessment that utilizes indirect observation and direct implementation approaches to determine verbal operant skills that the participant can demonstrate. In the current study for both assessments, teachers or paraprofessionals at the school who had worked with the student for at least 4 months prior to the onset of the study completed the indirect assessment procedure. This involved going through each item on the assessment and indicating “Y,” “N,” or “?” where “Y” indicated that the assessor had seen the participant demonstrate the skill in the past, “N” indicated that the assessor had not seen the participant demonstrate the skill and was certain that the participant could not demonstrate the skill, and “?” indicated that the assessor had not seen the participant demonstrate the skill and was uncertain whether the participant could demonstrate the skill. All items indicated as a “?” were directly tested. Direct testing in the current study involved the assessor conducting 10 trials of the program corresponding to the assessment item (i.e., delivering the discriminative stimulus, allowing time for a response), and withholding reinforcement or praise for correct participant responses. If the participant demonstrated 80% correct responding or greater during the testing trial block, the item was considered mastered and a “Y” was indicated on the assessment. Alternatively, if the participant demonstrated less than 80% correct responding, the item was not considered mastered and an “N” was indicated. The total number of “Y” scores were tallied to arrive at the PEAK-DT and PEAK-G total score values identified in the Participants and Setting section of this experiment. In addition, the results of the assessments were used to select programs that were used for training in the baseline phase of the current study. To select programs, the assessments were used to complete the performance matrices where cells corresponding with assessment items were highlighted. Once done, the unhighlighted cells closest to the top of the triangle, from left to right, identified the programs that were used in the baseline training phase of the current study.

A total of five programs were conducted with each of the participants at a given time throughout the baseline phase, and the module that the programs were taken from (i.e., PEAK-DT or PEAK-G) was based on clinical decisions corresponding to each participant’s individualized education plan. When a participant mastered a program, the next unhighlighted program on the performance matrix from top to bottom, left to right, replaced the mastered program. Training was guided by the program instruction sheet that corresponded with the target item. An exemplar program sheet from a PEAK-DT program is shown in Fig. 2 for comparison to the PEAK-E program. The instruction sheets contain a written goal statement, a list of materials needed to conduct the program, detailed instructions for caregivers regarding how to conduct the program, and a list of typical stimuli used. The PEAK-G instruction sheet differs from the PEAK-DT instruction sheet in that it provides instructions for both training trials and testing trials. The testing trials are conducted throughout training to ensure that trained responses generalize to untrained formally similar stimulus conditions, and mastery of both trained and tested responses was required for program mastery in the current study. The progression of training trials involved the following steps, after establishing motivation (i.e., conducting a preference assessment): the instructor delivers a discriminative stimulus consistent with the target program, allows time for the participant to respond, and delivers either reinforcement for the correct response or prompts the correct response before providing reinforcement. For testing trials in PEAK-G, no reinforcement or prompts are provided dependent on participants’ responses. Trial blocks of each program were conducted each day that the participants were present at school. In the current study, and for determining program mastery, the scoring metric provided in the PEAK curriculum was used (see Dixon, Whiting, Daar, & Rowsey, 2014c, for review). The scoring metric provides a measure of the number of representations of the discriminative stimulus and the prompting level required to evoke the correct response during a given trial. A score of 10 on a trial represents an independent correct response, 8 represents a single prompt of a visual or vocal nature, 4 represents two prompts with a full stimulus array presented, 2 represents multiple prompts or a reduced array, and 0 represents no correct response despite multiple prompts (or, in the case of testing trials in PEAK-G, an incorrect response). A program was considered mastered when participants achieved a PEAK score of 90 for the program across three consecutive trial blocks. Progression from the training baseline phase to the PEAK-E training phase was determined a priori to ensure that PEAK-E-PA test probes were staggered across participants in the multiple-baseline experimental design.

PEAK-E training