Abstract

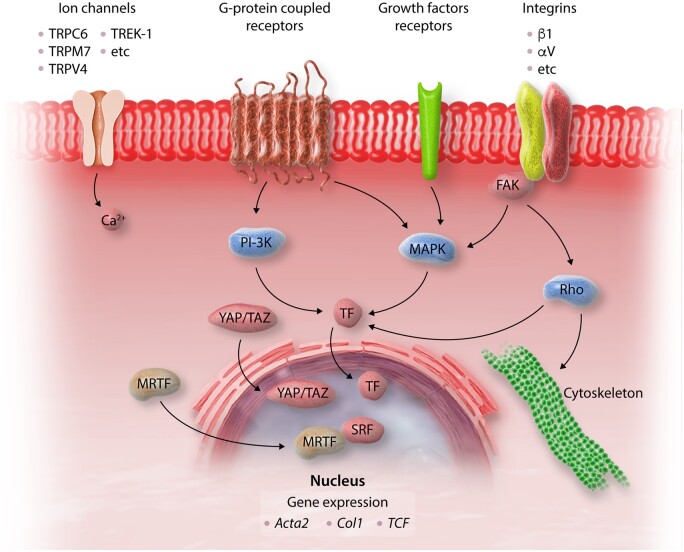

Myocardial fibrosis, the expansion of the cardiac interstitium through deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, is a common pathophysiologic companion of many different myocardial conditions. Fibrosis may reflect activation of reparative or maladaptive processes. Activated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are the central cellular effectors in cardiac fibrosis, serving as the main source of matrix proteins. Immune cells, vascular cells and cardiomyocytes may also acquire a fibrogenic phenotype under conditions of stress, activating fibroblast populations. Fibrogenic growth factors (such as transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factors), cytokines [including tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-4], and neurohumoral pathways trigger fibrogenic signalling cascades through binding to surface receptors, and activation of downstream signalling cascades. In addition, matricellular macromolecules are deposited in the remodelling myocardium and regulate matrix assembly, while modulating signal transduction cascades and protease or growth factor activity. Cardiac fibroblasts can also sense mechanical stress through mechanosensitive receptors, ion channels and integrins, activating intracellular fibrogenic cascades that contribute to fibrosis in response to pressure overload. Although subpopulations of fibroblast-like cells may exert important protective actions in both reparative and interstitial/perivascular fibrosis, ultimately fibrotic changes perturb systolic and diastolic function, and may play an important role in the pathogenesis of arrhythmias. This review article discusses the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis in various myocardial diseases, including myocardial infarction, heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction, genetic cardiomyopathies, and diabetic heart disease. Development of fibrosis-targeting therapies for patients with myocardial diseases will require not only understanding of the functional pluralism of cardiac fibroblasts and dissection of the molecular basis for fibrotic remodelling, but also appreciation of the pathophysiologic heterogeneity of fibrosis-associated myocardial disease.

Keywords: Fibrosis, Myofibroblast, Growth factor, Heart failure, Extracellular matrix

1. Introduction

The term fibrosis is used to describe the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in parenchymal tissues, and typically reflects inappropriate or unrestrained activation of a reparative programme. Fibrosis is an important cause of organ dysfunction in many different diseases, including interstitial lung diseases, liver cirrhosis, progressive systemic sclerosis, and diabetic nephropathy.1

Myocardial fibrosis, the expansion of the cardiac interstitium due to net accumulation of ECM proteins, accompanies most cardiac pathologic conditions.2,3 Although in most myocardial diseases, the extent of cardiac fibrosis predicts adverse outcome, fibrosis is not necessarily the primary cause of dysfunction. The adult mammalian heart has negligible regenerative capacity and heals through formation of a scar. Thus, in many cases, cardiac fibrosis is reparative, reflecting replacement of dead cardiomyocytes with a collagen-based scar. Myocardial infarction (MI) is a typical example of reparative fibrosis, as sudden death of a large number of cardiomyocytes stimulates inflammation and subsequent activation of reparative myofibroblasts, leading to formation of a scar. The scar lacks contractile capacity, but serves a critical protective role, maintaining the structural integrity of the chamber, and in the case of a transmural infarction, preventing catastrophic mechanical complications, such as cardiac rupture.4 In other cardiac diseases, fibrosis predominantly involves the interstitium, and develops insidiously in the absence of significant cardiomyocyte loss. For example, systemic hypertension is associated with progressive interstitial and perivascular deposition of ECM proteins that increase myocardial stiffness and cause diastolic dysfunction. Ageing, obesity, and diabetes can also promote myocardial interstitial fibrosis and reduce ventricular compliance, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Thus, cardiac fibrosis is not a single disease entity that would predictably benefit from a standardized therapeutic intervention, but rather a pathologic response that may be appropriate or inappropriate, depending on the pathophysiologic context. This review article discusses the pathophysiologic heterogeneity of myocardial fibrotic responses, focusing on the functional consequences of cardiac fibrosis, the key cellular effectors, and the main molecular mechanisms. The article also highlights the unique characteristics of fibrotic remodelling in various myocardial diseases and discusses the benefits and perils of possible therapeutic interventions.

2. The normal cardiac interstitium

In adult mammalian hearts, cardiomyocytes occupy approximately 75% of the myocardial volume and are organized into laminae, 2–5 cells thick. These layers of cardiomyocytes are surrounded by an interstitial ECM network, comprised predominantly of fibrillar collagens.5,6 The cardiac ECM not only serves as a mechanical scaffold but is also important for transmission of contractile force. In addition to type I collagen (the most abundant protein in the cardiac ECM) and type III collagen,7,8 the cardiac ECM also contains a wide range of glycoproteins, glycosaminoglycans, and proteoglycans, and a reservoir of stored latent growth factors and proteases, that can be rapidly activated following injury to stimulate repair. Several different cell types are enmeshed within the interstitial ECM. Vascular endothelial cells are the most abundant non-cardiomyocytes in adult mouse hearts, reflecting the rich microvasculature of the myocardium.9 Smaller populations of immune cells (macrophages, mast cells, and dendritic cells), and vascular mural cells (smooth muscle cells and pericytes) are also found in the normal cardiac interstitium.10–13 Cardiac fibroblasts, the main matrix-producing cells, form one of the largest cell populations in normal mammalian hearts and are typically enmeshed in the endomysium and perimysium.14,15 The abundance of fibroblasts in uninjured hearts may suggest an important homeostatic role; however, the functions of cardiac fibroblasts in the absence of injury remain poorly defined. Resident cardiac fibroblasts may serve to maintain the structural integrity of the matrix network,16 regulating collagen turnover, a process that requires ongoing synthesis and degradation of ECM proteins.17,18 Fibroblast-specific baseline activation of Smad3 signalling has been reported to maintain normal ECM content in adult mouse hearts,19 whereas platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α signalling was found to be important for fibroblast survival and optimal support of the normal microvascular network.20 However, these actions had no significant effects on baseline organ function. It has been suggested that cardiac fibroblast subpopulations may also support cardiomyocyte survival and function; however, robust evidence documenting such actions in normal adult hearts is lacking. In uninjured mouse hearts, fibroblasts exhibit heterogeneity and can be subclassified into several subsets on the basis of their transcriptomic profile.21 Whether these subsets exhibit distinct roles in cardiac homeostasis remains unknown.

3. Classification of myocardial fibrotic lesions

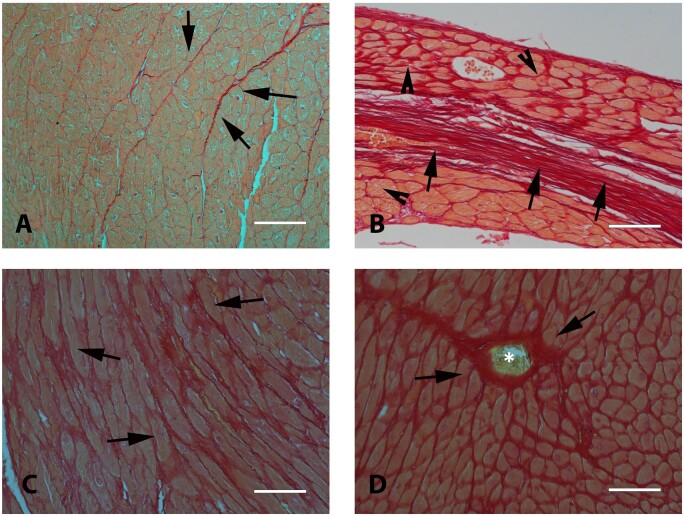

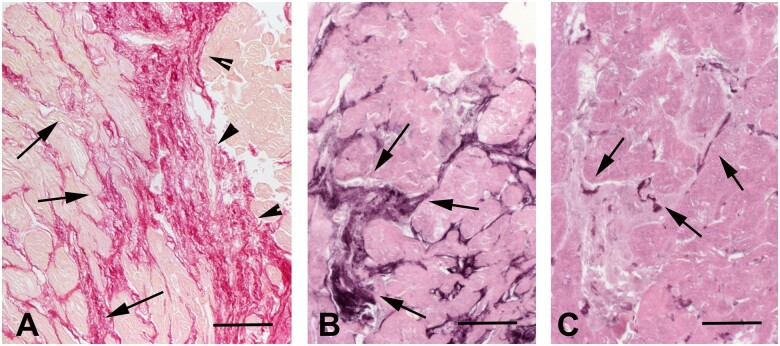

Basic histopathological analysis allows classification of cardiac fibrotic lesions into three distinct forms (Figure 1). In MI, necrotic cardiomyocytes are replaced by collagen-based scar, causing ‘replacement fibrosis’. ‘Interstitial fibrosis’ describes the expansion of the endomysial and perimysial space, caused by net accumulation of ECM proteins in the absence of significant cardiomyocyte loss. The term ‘perivascular fibrosis’ is used to describe the expansion of the microvascular adventitia. This simple and crude classification has major implications regarding the pathophysiologic basis of the fibrotic lesion and its effects on cardiac function. Replacement fibrosis is typically reparative, reflecting the absence of regenerative capacity of the adult mammalian heart in response to primary necrotic injury. Interstitial and perivascular fibrosis on the other hand may result from prolonged activation of fibrogenic stimuli and may represent primary injurious processes. Perivascular fibrotic changes are prominent in hypertensive heart disease and may reflect fibroblast conversion or fibrogenic activation of vascular endothelial or mural cells,22,23 or stimulation of adventitial fibroblasts.24 Whether perivascular and interstitial fibrotic changes have distinct cell biological origins remains unknown. Replacement fibrosis is predominantly associated with systolic dysfunction. In contrast, interstitial and perivascular fibrosis typically reduce left ventricular compliance perturbing diastolic function with less pronounced or late effects on systolic function. Moreover, perivascular fibrosis may perturb coronary follow and induce microvascular dysfunction25,26 precipitating diastolic dysfunction and worsening the severity of ischaemia.

Figure 1.

Histological types of cardiac fibrosis. Images show sections of adult mouse hearts stained with picrosirius red in order to label collagen fibres. (A) The normal adult mammalian heart contains an intricate network of collagenous matrix. Every cardiomyocyte is surrounded by a thin network of endomysial collagen. Thicker perimysial collagen fibres (arrows) enwrap bundles of cardiomyocytes. (B) Following myocardial infarction, dead cardiomyocytes are replaced by collagen-based scar. Replacement fibrosis is shown in a mouse model of reperfused myocardial infarction (arrows, 1 h ischaemia–7 days reperfusion). Infarction is midmyocardial; interstitial fibrosis is noted in remodelling subendocardial and subepicardial areas (arrowheads). (C) Interstitial fibrosis (arrows) is noted in a model of left ventricular pressure overload, induced through transverse aortic constriction (7 days). (D) Perivascular fibrosis (arrows) is also noted in the pressure-overloaded myocardium, with large amounts of collagen surrounding an intracoronary vessel (*). Scalebar = 80 µm.

More sophisticated analysis of the cellular composition, molecular and biochemical profile of fibrotic lesions could be used to gain additional information with mechanistic, diagnostic and potentially also prognostic significance. The relative abundance of immune cells, the phenotype and level of activation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, the expression of matricellular proteins and the levels of ECM cross-linking could provide key insights into the pathogenesis, activity and reversibility of myocardial fibrosis. In human patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy undergoing aortocoronary bypass surgery, highly cellular interstitial fibrosis, characterized by increased inflammatory activity, and higher levels of the matricellular protein tenascin-C was associated with more dynamic lesions and with an increased likelihood of recovery after aortocoronary bypass surgery.27,28 On the other hand, higher levels of ECM cross-linking and a hypocellular interstitium may mark fibrotic lesions with low potential reversibility.29

4. The cell biology of cardiac fibrosis

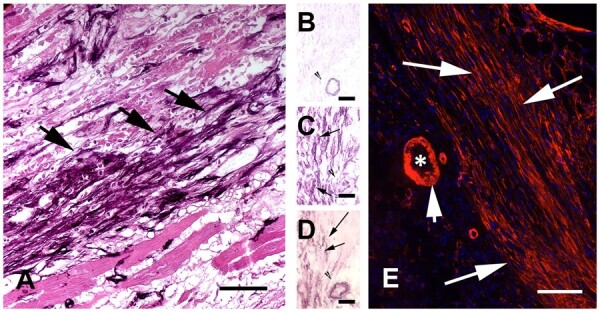

Activated fibroblasts are the central cellular effectors of myocardial fibrosis, serving as the main ECM-producing cells. Conversion of fibroblasts into secretory, matrix-producing and contractile cells, called myofibroblasts, is a crucial cellular event in many fibrotic conditions (Figure 2). Activated myofibroblasts are the main source of structural ECM proteins in fibrotic hearts,31 produce large amounts of matricellular proteins,32,33 and can also contribute to the regulation of matrix remodelling by producing proteases, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and their inhibitors.34 The expansion and activation of fibroblasts in remodelling hearts may involve direct effects of fibrogenic mediators, or upstream stimulation of other cell types, including immune cells, vascular cells and cardiomyocytes. Immune cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, mast cells, and eosinophils) may promote fibroblast activation by secreting cytokines, growth factors, and matricellular proteins. Vascular endothelial cells and pericytes may also secrete fibroblast-activating mediators, and have been reported to undergo myofibroblast conversion. Injured cardiomyocytes are also capable of producing fibrogenic mediators in response to stress, contributing to fibroblast activation. Moreover, in MI, death of cardiomyocytes and other myocardial cells results in release of damage-associated molecular patterns that activate inflammation, ultimately leading to fibrosis. The relative role of various cell types in the fibrotic response is dependent on the type of myocardial injury.

Figure 2.

The myofibroblasts are the main cellular effectors of fibrosis in injured and remodelling hearts. Myofibroblasts are activated fibroblasts that express contractile proteins, such as α-SMA and secrete large amounts of ECM proteins. Images show abundant myofibroblasts in infarcted hearts in both large animal and rodent models. (A) Immunohistochemical staining identifies non-vascular α-SMA+ myofibroblasts in the border zone of a reperfused canine infarct (arrows, 1 h ischaemia/7 days reperfusion). (B–D) Serial staining of frozen sections from the infarcted canine heart show that border zone infarct myofibroblasts express α-SMA (D) and the embryonal isoform of smooth muscle myosin (SMemb) (C), but not the SM2 isoform, a marker of mature smooth muscle cells (B). Thus, these cells (arrows) are myofibroblasts and not smooth muscle cells. Arrowhead shows an arteriole, exhibiting expression of α-SMA (D) and SM2 (B). (E) Abundant α-SMA+ myofibroblasts are found in the border zone of a mouse infarct (7 days ischaemia). The short arrow points to the vascular smooth muscle cells on the arteriolar (*) media, which are also strongly positive for α-SMA. Scalebar = 80 µm. Original data published in ref.30

4.1 Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: the central effector cells in cardiac fibrosis

The term fibroblast is used to describe cells of mesenchymal origin that populate connective tissues, lack a basement membrane and are capable of producing significant amounts of ECM proteins. Under this broad definition, a wide range of cardiac interstitial cells can be identified as fibroblasts. Fibroblasts can be distinguished from other myocardial interstitial cells on the basis of the expression of discoidin domain-containing receptor 2, PDGFR-α, and the transcription factor Tcf21.15 Identification and characterization of fibroblast populations is further complicated by their dynamic phenotypic alterations in injured tissues.35 In infarcted and stressed hearts, fibroblasts undergo conversion to myofibroblasts, cells that exhibit a prominent endoplasmic reticulum (indicating a synthetically active phenotype), while expressing contractile proteins, such as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).36,37 Infiltration of the heart with activated myofibroblasts has been reported in a wide range of pathologic conditions, including MI,30,38 non-infarctive ischaemic cardiomyopathy,27,39 myocarditis,40 diseases associated with cardiac pressure or volume overload,41,42 and alcoholic cardiomyopathy.43 However, myofibroblast conversion is not required for activation of a pro-fibrotic programme. In a model of diabetic fibrotic cardiomyopathy, deposition of interstitial collagen and acquisition of a matrix-synthetic phenotype by cardiac fibroblasts was found to be independent of myofibroblast transdifferentiation.44 Moreover, single-cell transcriptomic analysis in a model of angiotensin II-induced fibrosis identified fibroblast subsets expressing Cartilage Intermediate layer protein 1 (Cilp) or Thrombospondin-4 (Thbs4) as the predominant fibrogenic cell types, in the absence of α-SMA-expressing myofibroblasts.45

Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that myofibroblasts exhibit a range of phenotypic profiles. Although α-SMA expression is often used to identify ‘differentiated myofibroblasts’ in injured tissues, early stage myofibroblasts may not express α-SMA, but may have a robust stress fibre network and form focal adhesions. These cells were termed ‘proto-myofibroblasts’,46,47 and may be prominent in early interstitial fibrotic lesions triggered by mechanical stress. Transcriptomic analysis suggests that in myocardial injury sites, infiltration with activated fibroblasts expressing the matricellular protein periostin precedes their conversion to myofibroblasts.21 Whether these activated periostin+/α-SMA− cells represent proto-myofibroblasts remains unknown.

In the era of single-cell transcriptomics, it is increasingly appreciated that both fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are heterogeneous populations, comprised of several subsets with distinct transcriptomic profiles. In healing infarcts subpopulations of myofibroblasts with high expression of fibrogenic mediators, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, have been identified, along with other myofibroblasts that expressed transcripts encoding proteins with anti-fibrotic properties, such as the matricellular gene Wisp/CCN5 and the Wnt antagonist Sfrp.21 Whether these transcriptomic profiles are associated with pro- vs. anti-fibrotic properties remains unknown.

4.2 Where do activated cardiac myofibroblasts come from?

The abundant fibroblasts that reside in the normal cardiac interstitium are capable of activation following injury and can account for the injury-associated expansion of matrix-secreting myofibroblasts. Despite this fact, several studies have suggested that other cell types, including haematopoietic fibroblast progenitors,48–51 macrophages,52 and endothelial cells22,53 may also contribute to myofibroblast accumulation in injured hearts by transdifferentiating to fibroblasts or myofibroblasts. The relative contribution of these cells remains controversial. Several robust studies combining lineage tracing strategies, bone marrow transplantation experiments, and parabiosis models have demonstrated that the vast majority of activated myofibroblasts in both infarctive and in pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis are derived from resident fibroblast populations, and that the contributions of vascular endothelial cells and haematopoietic cells are very limited.54–57 Several factors may explain the conflicting observations. First, some of the studies use associative data based on co-expression of various markers to imply haematopoietic or endothelial cell origin of fibroblasts. Second, in some studies the use of non-specific markers for identification of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, such as fibroblast-specific protein-1 which is also highly expressed by macrophages and vascular cells,58 may explain erroneous conclusions regarding cellular identity. Third, in some cases, the use of non-specific Cre drivers to trace endothelial cells or leucocytes may limit the value of the observations. Fourth, conflicting findings may reflect disease-specific and context-dependent alterations in the cellular composition of the cardiac interstitium. Generalizing cell biological paradigms to all types of myocardial injury are inherently problematic, and do not take into account the distinct profile of cellular responses caused by various injurious stimuli. For example, in inflammatory myocardial diseases, such as myocarditis, the intense chemokine-dependent infiltration of the heart with immune cells may also recruit abundant circulating progenitors that may contribute to fibroblast expansion, independently of the resident fibroblast population. Experiments using bone marrow chimeric mice in a model of autoimmune myocarditis suggested that a large fraction of activated fibroblasts originate from a population of prominin+ haematopoietic cells that infiltrate the myocardium.59 On the other hand, in MI, contributions of various cell types may be context-dependent. In a reperfused infarct, most fibroblasts in the area at risk likely survive the ischaemic event and may account for myofibroblast expansion. In contrast, when the coronary artery is permanently occluded, the majority of cardiac interstitial cells may die along with the neighbouring cardiomyocytes; thus, limiting their contribution to the reparative myofibroblast population, which may be derived predominantly from fibroblasts recruited from non-infarcted segments, or from other remote cell types (including circulating haematopoietic cells). Unfortunately, studies on myocardial cell death following infarction have focused almost exclusively on cardiomyocytes; information on the fate of fibroblasts and other interstitial cells is extremely limited. The unique cell biological characteristics of disease-specific fibrotic myocardial responses remain underappreciated and understudied.

4.3 Mechanisms involved in myofibroblast activation in fibrotic hearts

Activated myofibroblasts contribute to matrix remodelling, not only by secreting large amounts of structural ECM proteins but also by releasing proteases and their inhibitors and by producing enzymes involved in matrix processing. Although the mechanisms of myofibroblast activation are dependent on the specific type of injury causing the myocardial fibrotic response, some common patterns have emerged. Neurohumoral mediators, cytokines and growth factors are released and activated following myocardial injury and bind to cell surface receptors, transducing fibrogenic intracellular signalling cascades. Moreover, specialized matrix proteins and matricellular macromolecules enrich the matrix network and serve to locally activate fibrogenic growth factors at the site of injury providing spatial regulation of the fibroblast-activating signals.

In addition to the fibroblasts, several other cell types contribute to the fibrogenic environment. Immune cells, including macrophages, mast cells, and lymphocytes are recruited and activated in remodelling hearts and may play an important role in fibroblast activation by secreting a wide range of fibrogenic mediators, including cytokines, growth factors, and matricellular proteins.60–65 Endothelial cells, pericytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells may also secrete molecular signals that regulate fibroblast behaviour.66 Cardiomyocytes are also highly sensitive to microenvironmental changes and typically respond to injurious stimuli by activating inflammatory and fibrogenic programmes.67 It should be emphasized that the actions of leucocytes, vascular cells and cardiomyocytes on fibroblast phenotype are not necessarily activating. Several studies have demonstrated injury-associated induction and release of anti-fibrotic mediators in leucocytes,68 endothelial cells,69,70 and cardiomyocytes71 that may serve to restrain fibrogenic responses.

5. Fibroblast-activating neurohumoral pathways

5.1 The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

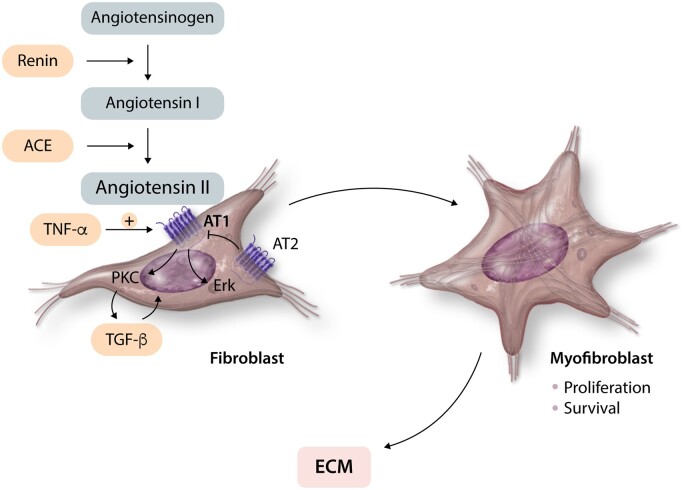

5.1.1 The angiotensin II/AT1 axis

The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is activated in fibrotic and remodelling hearts regardless of the underlying aetiology and plays an important role in myofibroblast activation. Stressed cardiomyocytes, immune cells and fibroblasts produce renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), contributing to angiotensin II generation72–74 (Figure 3). When released in the cardiac interstitium, angiotensin II is a potent activator of cardiac fibroblasts. In vitro studies have demonstrated that angiotensin II stimulates cardiac fibroblast proliferation,75 inhibits fibroblast apoptosis,76 stimulates fibroblast migration77,78 inducing integrin expression,79 promotes myofibroblast conversion,80 and markedly increases synthesis of structural ECM proteins.81,82 All these activating effects of angiotensin II involve signalling through the type 1 angiotensin receptor (AT1). In contrast, the type 2 receptor AT2 acts as a negative regulator of angiotensin II-mediated fibrogenic responses, inhibiting AT1 actions and suppressing fibroblast proliferation and matrix synthesis.83,84

Figure 3.

Fibrogenic effects of angiotensin II. Angiotensin II generated in injured or remodelling myocardium exerts potent fibrogenic actions on cardiac fibroblasts through interactions with the AT1 receptor, promoting myofibroblast conversion, fibroblast proliferation and survival and stimulating ECM synthesis. In contrast, signalling through the AT2 receptor inhibits the pro-fibrotic effects of AT1. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, induce AT1 in cardiac fibroblasts and may accentuate the activating effects of angiotensin II. Fibrogenic effects of angiotensin II are mediated through activation of PKC and Erk signalling. Some of the effects of angiotensin II may involve downstream induction and activation of TGF-β.

The activating effects of the angiotensin II/AT1 axis in cardiac fibroblasts are mediated at least in part through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), protein kinase C (PKC) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) cascades.75,85–87 Some fibrogenic angiotensin II actions require induction,88,89 or activation of TGF-β.90 Moreover, responsiveness of fibroblasts to angiotensin II is modulated by a wide range of mediators that regulate expression of the angiotensin receptors. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines may make fibroblasts more responsive to the effects of angiotensin II by inducing AT1 synthesis.91 In contrast, angiotensin II has been reported to downmodulate AT1 expression,92 providing a negative feedback mechanism that may restrain uncontrolled fibrogenic actions.

There is abundant in vivo evidence, predominantly derived from pharmacologic interventions, supporting the role of AT1 signalling in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. AT1 inhibition attenuated interstitial fibrosis in models of MI93 and left ventricular pressure overload.94 Despite the lack of evidence documenting the role of fibroblast-specific AT1 signalling in vivo using cell-specific genetic approaches, the potent in vitro effects of the angiotensin II/AT1 axis suggest that cardiac fibroblasts may be major targets of angiotensin II. Thus, the beneficial effects of ACE inhibition and AT1 blockade in heart failure patients may reflect, at least in part, attenuation of angiotensin-mediated fibrosis. Evidence in isolated cardiomyocytes has suggested that AT1 signalling may not always require angiotensin II stimulation but may be directly activated by mechanical stress, stimulating a hypertrophic response.95 Whether angiotensin-independent AT1 signalling is involved in myofibroblast activation and in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis remains unknown.

5.1.2 The fibrogenic actions of aldosterone

Extensive evidence suggests that aldosterone may play an important role in fibroblast activation following myocardial injury.96,97 In isolated cardiac fibroblasts, aldosterone triggers a proliferative response,98 stimulates migration,99 and promotes a matrix-synthetic phenotype,100 at least in part through activation of MAPK cascades.101 Whether these actions are responsible for the fibrogenic actions of aldosterone in vivo is unclear. In addition to its effects on fibroblasts, aldosterone has been suggested to modulate cardiomyocyte, macrophage, lymphocyte, and vascular cell phenotype, leading to activation of a fibrogenic programme. Experiments using cell-specific mineralocorticoid receptor knockout mice suggested that aldosterone actions on myeloid cells,102 T lymphocytes,103 and cardiomyocytes104 may contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis.

5.2 The β-adrenergic response in fibroblast activation

Adrenergic stimulation activates fibroblasts and induces fibrotic cardiac remodelling. In vivo, infusion of the non-specific β adrenergic receptor (AR) agonist isoproterenol,105 or the α1 AR agonist phenylephrine,106 and transgenic overexpression of β2-ARs107 cause marked myocardial fibrosis. The pro-fibrotic effects of adrenergic stimulation may be indirect, reflecting reparative fibrosis in response to cardiomyocyte necrosis, release of fibrogenic mediators by stimulated cardiomyocytes, or immune cell activation.105,108–110 Although direct effects of adrenergic agonists on cardiac fibroblasts are well-documented, their in vivo significance is unclear. β-AR activation stimulates proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts,111,112 activating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K)113 and MAPK114 signalling Moreover, proliferative effects of β-AR stimulation in fibroblasts have been attributed to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation and downstream activation of ERK signalling.115

The relative role of β1- and β2-AR responses in regulating the fibrotic response is unknown. Although in some experimental animal models of heart failure, non-selective β-AR inhibition and administration of β1-AR blockers attenuated cardiac fibrosis,116,117 such effects may represent an epiphenomenon reflecting reduced blood pressure or attenuated cardiomyocyte death. Moreover, β2-AR signalling in myofibroblasts has been reported to exert pro-hypertrophic actions through paracrine mechanisms.118 Although the role of β3-AR signalling in fibroblasts is unknown, recent evidence suggests that cardiomyocyte-specific β3-AR signalling may exert anti-fibrotic actions by downmodulating expression of cardiomyocyte-derived fibrogenic proteins, such as the matricellular protein CCN2.119

AR signalling induces conformational changes in G protein βγ subunits, ultimately resulting in activation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2). Activation of GRK2 in fibroblasts has been implicated in cardiac fibrosis in experimental models of MI.120,121 However, the molecular targets responsible for the fibrogenic actions of GRK2 remain poorly understood.

5.3 Inflammatory mediators as regulators of fibroblast function

Inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis through direct actions on fibroblasts, by stimulating recruitment and activation of fibrogenic macrophages and lymphocytes, and by triggering a fibrogenic programme in vascular cells and cardiomyocytes. Moreover, prolonged chronic inflammation may cause cardiomyocyte necrosis, triggering a reparative form of fibrosis.

5.3.1 Chemokines as regulators of cardiac fibrosis

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines with a prominent role in leucocyte trafficking.122 From a structural perspective, chemokines are classified into four subfamilies (CC, CXC, CX3C, and XC), on the basis of the number of aminoacids between their first two cysteine residues. This classification has important functional implications: CC chemokines are predominantly mononuclear cell chemoattractants, whereas CXC chemokines, and in particular the subgroup containing the conserved ELR sequence motif (glutamic acid–leucine–arginine) near the aminoternimal end, are involved in recruitment of neutrophils. Actions of chemokines in regulation of fibrosis are predominantly mediated through chemotactic recruitment of leucocytes. Although several members of the family may directly modulate fibroblast phenotype and function, the in vivo significance of these effects in cardiac fibrotic remodelling remains unclear.123

5.3.2 CC chemokines

Extensive experimental evidence suggests that the CC chemokine CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis in a wide range of models, including ischaemic cardiomyopathy, pressure overload-induced myocardiac remodelling and inflammatory heart diseases (Table 1).125,126,129 The fibrogenic actions of CCL2 has been predominantly attributed to recruitment and activation of monocytes and macrophages expressing the main CCL2 receptor, CCR2, resulting in up-regulation of fibrogenic mediators, such as TGF-β and osteopontin.128,129,137 Although CCL2 has been suggested to promote direct fibrogenic actions in hepatic, cutaneous and pulmonary fibroblasts,138–140 in isolated cardiac fibroblasts, no significant effects of CCL2 were noted on profibrotic gene expression profile and proliferative activity.129 Some studies have suggested that CCL2 may promote fibrosis by recruiting circulating fibroblast progenitors.49,50 However, the evidence supporting this notion is associative and based on co-expression of haematopoietic cell and fibroblast markers by the same cells. Considering the robust evidence from several studies using lineage tracing strategies suggesting that most activated fibroblasts in the remodelling heart are derived from resident populations and not from haematopoietic cells55–57 the role of circulating fibroblast progenitors in cardiac fibrosis remains controversial.141

Table 1.

The CCL2/CCR2 axis in cardiac fibrosis

| Experimental model of cardiac fibrosis | Findings | Cellular target and molecular mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic CCL2 overexpression | Cardiomyocyte-specific CCL2 overexpression in mice induced myocardial inflammation and fibrotic changes. | Fibrogenic actions presumed due to inflammatory cell recruitment and activation. | 124 |

| Rat model of cardiovascular remodelling through chronic inhibition of NO synthesis | Treatment with anti-CCL2 antibody attenuated inflammation and reduced coronary vascular remodelling but did NOT affect fibrosis. | NA | 125 |

| Rat model of pressure overload through suprarenal aortic constriction | Anti-CCL2 antibody attenuated myocardial fibrosis. | Anti-fibrotic effects were presumed due to decreased macrophage recruitment and attenuated TGF-β release | 126 |

| Mouse model of non-reperfused myocardial infarction | Anti-CCL2 gene therapy attenuated interstitial fibrosis without affecting infarct size. | Anti-fibrotic effects were attributed to decreased macrophage infiltration and attenuated TNF-α and TGF-β levels. | 127 |

| Mouse model of reperfused myocardial infarction | CCL2 KO mice had attenuated myofibroblast proliferation and delayed granulation tissue formation after MI, associated with reduced dilative remodelling. | Anti-fibrotic effects were attributed to reduced macrophage recruitment and impaired macrophage activation, associated with markedly decreased expression of TGF-β and osteopontin. | 128 |

| Mouse model of ischaemic cardiomyopathy induced through brief repetitive ischaemia/reperfusion | CCL2 KO mice had attenuated interstitial fibrosis, associated with reduced macrophage recruitment and decreased fibroblast proliferation. | CCL2 did not have direct effects on proliferation or expression of fibrosis-associated genes by cardiac fibroblasts. Thus, the profibrotic effects of CCL2 were attributed to actions on macrophages. | 129 |

| Mouse model of angiotensin II-induced fibrosis | CCL2 KO mice had attenuated fibrosis. | Fibrogenic effects of CCL2 were attributed to recruitment of circulating fibroblast precursors. This notion was based on the presence of CD34+/CD45+ collagen-expressing fibroblast-like cells in the myocardium. | 50 |

| Mouse model of angiotensin II-induced fibrosis | CCR2 KO mice had attenuated angiotensin II-mediated cardiac fibrosis. | Fibrogenic effects of CCR2 were attributed to recruitment of bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors. This notion was based on the presence of CD34+/CD45+ collagen-expressing fibroblast-like cells in the myocardium. | 130 |

| Mouse model of angiotensin II-induced fibrosis | CCR2 KO mice had attenuated angiotensin II-mediated cardiac fibrosis. | Fibrogenic effects of CCR2 were attributed to attenuated recruitment of fibroblast progenitors. This notion was based on detection of CD45/α-SMA+ cells. CCR2-mediated fibrosis was attributed to actions of CCL12 (and not CCL2), based on associative data. | 131 |

| Mouse model of mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated cardiac fibrosis | In a deoxycorticosterone (DOC)/salt model, CCL2 KO mice had 35% less myocardial fibrosis. | Fibrogenic effects of CCL2 were attributed to actions on macrophage recruitment and activation. However, CCL2 KO mice also had lower blood pressure, suggesting that the fibrogenic actions of CCL2 may be indirect, reflecting effects on blood pressure regulation. | 132 |

| Mouse model of ageing | Aged CCL2 KO mice had reduced fibrosis and attenuated diastolic dysfunction. | Attenuated fibrosis in CCL2 KO mice was associated with reduced leucocyte infiltration. | 133 |

| Mouse model of angiotensin-induced fibrosis | Administration of a CCR2 antagonist attenuated myocardial inflammation and fibrosis. | CCL2 up-regulation was stimulated by angiotensin-induced CaMKIIδ activation. The mechanisms for the fibrogenic effects of the CCL2/CCR2 axis were not investigated. | 134 |

| Mouse model of left ventricular pressure overload | Depletion of CCR2+ monocytes ameliorated cardiac fibrosis. | The findings highlighted the role of the monocytes recruited through CC chemokines in the pathogenesis of myocardial fibrosis. | 135 |

| Mouse model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes | Diabetic CCR2 KO mice had attenuated myocardial fibrosis. | The fibrogenic actions were attributed to macrophage-driven inflammation and oxidative stress. | 136 |

5.3.3 CXC chemokines

Several members of the CXC chemokine family have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. CXC chemokines that bind to the CXCR2 receptor may exert fibrogenic actions through recruitment of neutrophils or monocytes with fibrogenic properties. In spontaneously hypertensive rats, CXCR2 inhibition was found to attenuate fibrosis142; however, CXCR2-mediated fibrosis may involve effects on blood pressure regulation, rather than pro-fibrotic actions. CXCL1, one of the CXCR2 ligands has been reported to contribute to the development of angiotensin-induced cardiac fibrosis through recruitment of a fibrogenic monocyte subpopulation.143

CXCL12 has a broad range of actions in injured and remodelling hearts and has been involved in angiogenesis, recruitment of inflammatory and progenitor cells, and in regulation of cardiomyocyte survival following injury.144,145 Several studies have suggested that CXCL12 may exert fibrogenic actions through CXCR4 activation. CXCR4 antagonism reduced cardiac fibrosis in a genetic model of murine cardiomyopathy,146 and in models of diabetic fibrosis147 and cardiorenal syndrome.148 The fibrogenic actions of CXCL12 were attributed to direct pro-migratory effects on fibroblasts, to recruitment of fibroblast progenitors, or to activation of macrophages.149

The ELR-negative CXC chemokines do not stimulate neutrophil chemotaxis, but recruit lymphocyte subsets and have been suggested to exert actions on fibroblasts and endothelial cells. The ELR-CXC chemokine CXCL10/interferon-γ-inducible protein (IP)-10 is consistently up-regulated following cardiac injury and has been suggested to exert anti-fibrotic actions. Inhibition of fibrosis by CXCL10 may involve recruitment of yet unidentified leucocyte subsets that suppress fibroblast function, or direct de-activating effects on cardiac fibroblasts.69,70In vitro, CXCL10 was found to inhibit growth-factor-mediated fibroblast migration,69 through interactions with proteoglycans that were independent of the main CXCL10 receptor, CXCR3.150

5.3.4 The pro-inflammatory cytokines in cardiac fibrosis

Levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 are markedly increased in many myocardial pathologic conditions associated with fibrosis. Several clinical studies have demonstrated correlations between pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and fibrosis-related endpoints. For example, in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, elevated myocardial IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA levels were associated with collagen deposition and gelatinase expression,151 and in transplanted human hearts myocardial IL-6 levels were associated with fibrotic remodelling.152 These associations suggest a link between pro-inflammatory cytokines and fibroblast activation. The fibrogenic effects of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 may involve direct actions on fibroblasts, or indirect effects, related to recruitment of macrophages, induction of matricellular proteins and up-regulation of growth factors with prominent fibroblast-activating properties, such as TGF-β.

5.3.5 TNF-α

Abundant in vivo evidence suggests an important role for TNF-α in cardiac fibrosis (Table 2). Transgenic mice with myocardial TNF-α overexpression develop heart failure associated with fibrotic changes.153,154 The time course of ECM remodelling in TNF-α overexpressing hearts suggests that early protease-mediated matrix degradation is followed by late up-regulation of TGF-βs and activation of a matrix-preserving programme.155 Experiments using loss-of-function models have implicated endogenous TNF-α in the pathogenesis of fibrosis induced through pressure overload157,163 through actions involving the type 1 TNF receptor (TNFR1).161

Table 2.

The role of TNF-α in cardiac fibrosis

| Model | Findings | Cellular mechanism of fibrosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac-specific TNF-α overexpression | Terminally ill mice with myocardial overexpression of TNF-α had biventricular fibrosis. This was accompanied by chamber dilation, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and transmural myocarditis. | Not studied. TNF-induced fibrosis may reflect activation of immune cells that release fibrogenic cytokines, cardiomyocyte death activating a reparative programme, or direct effects of TNF-α on fibroblasts. | 153 |

| Cardiac-specific TNF-α overexpression | Cardiac overexpression of TNF-α caused heart failure associated with cardiac fibrosis. | Fibrosis was associated with marked induction of collagen synthesis and activationg of matrix-degrading proteases (MMP2 and MMP9). The primary cellular targets of TNF-α are unclear. | 154 |

| Cardiac-specific TNF-α overexpression | Cardiomyocyte-specific TNF-α overexpression caused progressive ventricular dilation and fibrosis. | Early activation of matrix-degrading MMPs was followed by late increases in TGF-β levels and fibrillar collagen content. Thus, TNF-α may promote an early matrix-degrading response, followed by a late TGF-β-driven matrix-preserving process. | 155 |

| Global TNFR1 and TNFR2 KO mice undergoing non-reperfused MI protocols. | Interstitial fibrosis was increased in TNFR2, but not in TNFR1 KO mice. Infarct size was comparable between groups. | Unclear cellular targets. TNFR2 loss was associated with increased post-infarction IL-1β and IL-6 levels that may account for fibrogenic actions. | 156 |

| TNF-α KO mice undergoing transverse aortic constriction (TAC) protocols | TNF-α loss attenuated cardiac fibrosis following TAC, associated with improved cardiac function. | TNF-α mediates fibrosis and protease activation in the pressure-overloaded heart. Cellular targets unclear. | 157 |

| Anti-TNF monoclonal antibody treatment in streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy | TNF-α inhibition reduced myocardial fibrosis and improved LV function. | TNF-α mediates fibrosis activating a matrix-synthetic programme. Cellular targets unclear. | 158 |

| TNF-α KO mice undergoing TAC protocols | TNF loss attenuated cardiac fibrosis following TAC. | Profibrotic effects of TNF-α were attributed to activation of a superoxide/MMP axis more prominently in cardiomyocytes and at a lower level in fibroblasts. | 159 |

| Cardiac-specific TNF-α overexpression | TNF overexpression was associated with mast cell expansion and subsequent fibroblast activation. Mast cell deficiency abrogated TNF-induced fibrosis. | Profibrotic effects of TNF-α may involve mast cell growth and activation, and subsequent release of mast-cell-derived fibrogenic mediators. | 160 |

| TNFR1 and TNFR2 KO mice undergoing angiotensin II infusion protocols | TNFR1 loss, but not TNFR2 absence, attenuated cardiac fibrosis. | Fibrogenic actions of TNF-α/TNFR1 signalling were attributed to recruitment of circulating fibroblast progenitors. This notion was based on identification of CD34+/CD45+ fibroblast-like cells. | 161 |

| Mdx dystrophic mice receiving anti-TNF treatment (Remicade) | Remicade attenuated cardiac fibrosis but worsened systolic function. | The basis for the effects of TNF blockade was not studied. | 162 |

| TNF-α KO mice undergoing angiotensin II infusion protocols | TNF-α KO mice had reduced perivascular and interstitial fibrosis following angiotensin II infusion. | Fibrogenic actions were attributed to effects on oxidative stress-dependent MAPK, TGF-β, and nuclear factor (NF)-κB signalling. Fibrogenic effects may be in part related to hypertensive actions of TNF-α. | 163 |

TNF-α may promote fibrosis through direct actions on cardiac fibroblasts, or through effects on other myocardial cell types. It should be noted that TNF-α does not directly induce a matrix-synthetic programme in cardiac fibroblasts, but rather decreases collagen synthesis and stimulates MMP expression.164 Thus, TNF-α-mediated fibrosis may reflect a response to ECM degradation. In vitro experiments have suggested several additional mechanisms that may be responsible for TNF-α-induced fibroblast activation. TNF-α stimulated synthesis of the matricellular protein CCN4 and subsequent fibroblast proliferation,165 induced TGF-β expression,166 and may potentiate fibrogenic effects of angiotensin II, by stimulating AT1 receptor synthesis.91 TNF-α may also promote fibrogenic activation of immune cell populations in the injured myocardium. In TNF-α− overexpressing mice, the fibrogenic actions of TNF-α in the myocardium have been attributed, at least in part, to expansion of cardiac mast cells.160

5.3.6 The fibrogenic actions of the IL-1 family of cytokines

Studies in experimental models of MI have implicated IL-1 in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Global loss of IL-1 signalling in mice lacking the type 1 IL-1 receptor (IL-1R1) attenuated adverse fibrotic remodelling in a model of reperfused MI.167 Moreover, in a model of viral myocarditis local inhibition of IL-1 through overexpression of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) significantly reduced fibrosis.168 Much like for TNF-α, the fibrogenic actions of IL-1 likely involve effects in both fibroblasts and immune cells. Experiments in animals with fibroblast-specific loss of the IL1R1 receptor documented the significance of direct actions of IL-1 on cardiac fibroblasts. Fibroblast-specific IL-1R1 KO mice had lower myocardial collagen levels in the infarcted heart, and exhibited improved function and attenuated remodelling following MI.169In vitro studies suggest that the fibrogenic effects of IL-1 are not mediated through direct activation of myofibroblast-driven ECM synthesis. In fact, both IL-1α and IL-1β inhibit conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts,170–172 inhibit fibroblast proliferation,173 and decrease collagen synthesis by cardiac fibroblasts.164 IL-1-mediated fibrosis may be due to primary activation of pro-inflammatory and matrix-degrading pathways. IL-1 potently stimulates MMP expression and activity,167,170 while reducing synthesis of MMP inhibitors.174 Generation of matrix fragments and induction of TGF-βs by IL-1 may be responsible for indirect activation of a fibrogenic programme.

IL-33, another member of the IL-1 family of cytokines has been implicated in the regulation of fibrosis in several different organs.175 In human patients with end-stage heart failure, IL-33 and ST2 up-regulation were associated with fibrotic changes.176 In the pressure-overloaded myocardium, IL-33 was found to exert cardioprotective and anti-fibrotic actions, attributed to its binding to the ST2 receptor in cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts.177 However, considering the potent effects of the IL-33/ST2 axis on cardiomyocytes, macrophages and lymphocytes, whether the protective effects of IL-33 in the remodelling heart are mediated through direct actions on fibroblasts remains unknown. In vitro, IL-33 stimulation did not affect collagen synthesis by cardiac fibroblasts, but inhibited their migratory capacity and enhanced expression of inflammatory genes.178

5.3.7 The IL-6 family of cytokines

The IL-6 family of cytokines (also referred as the gp130 family, indicating the common signal transducer of these molecules) includes IL-6, IL-11, oncostatin-M, leukaemia-inhibitory factor and cardiotrophin-1 and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. The bulk of experimental evidence suggests that IL-6 exerts fibrogenic actions. Genetic absence of IL-6 attenuated cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in models of left ventricular pressure overload,179,180 MI,181 and diabetic cardiomyopathy.182 IL-6 neutralization has also been reported to exert anti-fibrotic actions. In models of aldosterone-mediated cardiac remodelling, left ventricular pressure overload, and genetic cardiomyopathy induced through Hsp20 overexpression, IL-6 neutralization reduced fibrotic changes and attenuated fibroblast activation.183–185 The fibrogenic effects of IL-6 have been attributed to STAT3-dependent stimulation of collagen synthesis by cardiac fibroblasts,186 or to induction of TGF-β.182

Recent studies have suggested that IL-11 may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis not only in the myocardium187 but also in the lung and kidney,188,189 serving as a downstream fibrogenic signal, induced by TGF-β. IL-11 inhibition attenuated TGF-β-mediated fibroblast activation in vitro, and global loss of IL-11Ra in vivo reduced interstitial fibrotic remodelling following pressure overload. The effects of IL-11 on fibroblast activation were attributed to post-transcriptional mechanisms involving ERK signalling. To what extent IL-11 exerts pro-fibrotic actions in human patients remains unclear. Recombinant human IL-11 has been extensively used for the treatment of thrombocytopenias with a good safety record and without any reports of fibrotic disease.190

It should be emphasized that studies examining the role of other gp130 cytokines do not support a consistent fibrogenic role of gp130 signalling. Oncostatin M has been suggested to exert anti-fibrotic actions in the myocardium by inhibiting fibrogenic TGF-β signalling cascades.191 Experimental studies in fibrotic responses of other organs have produced conflicting findings suggesting both pro-fibrotic192 and anti-fibrotic effects193 of oncostatin M. The conflicting data likely reflect the context-dependent actions of gp130 cytokines in vivo, which are driven by the wide range of their actions in many different cell types.

5.3.8 The fibrogenic actions of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13

The anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in several different organs.194,195 Extensive in vivo and in vitro evidence supports the role of endogenous IL-4 in cardiac fibrosis. IL-4 up-regulation has been reported in experimental models of cardiac injury, predominantly localized in mast cells,196 lymphocytes, and macrophages. In myocarditis, eosinophils may be an additional major source of IL-4.197 In a model of angiotensin II infusion, genetic loss of IL-4 reduced collagen deposition in the myocardium by 60%.198 Moreover, in a model of pressure overload induced through TAC, IL-4 neutralization attenuated fibrotic changes.199 IL-4 may exert direct fibrogenic actions by stimulating collagen synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts through activation of STAT6.198

In contrast, the evidence on the role of IL-13 in cardiac fibrosis is more limited. Induction of IL-13 has been documented in infarcted200 and in fibrotic senescent mouse hearts201 and may be localized in Th2 lymphocytes. IL-13 can activate a matrix-synthetic programme in fibroblasts,202 stimulating TGF-β expression and activation,203 and may promote a fibrogenic phenotype in monocytes and macrophages.201 However, the in vivo contribution of these fibrogenic actions of IL-13 in the cardiac fibrotic response has not been documented.

IL-10 up-regulation has been documented in both rodent and large animal models of reparative and pressure overload-induced fibrosis and is localized in T lymphocytes and subsets of macrophages infiltrating the injured and remodelling heart.204–206 In addition to its well-documented anti-inflammatory actions, IL-10 may also regulate the cardiac fibrotic response. Unfortunately, data from in vivo studies are conflicting, suggesting both pro-fibrotic and anti-fibrotic actions of IL-10. In a model of cardiac remodelling induced through unilateral nephrectomy, salt loading and aldosterone infusion, IL-10 was found to critically contribute to fibroblast activation and to the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction.206 The fibrogenic effects of IL-10 were indirect, and were attributed to acquisition of a fibrogenic programme by macrophages. These findings are consistent with in vitro observations suggesting that IL-10 does not significantly affect fibroblast gene expression profile,207 but promotes a matrix-preserving phenotype in macrophages through up-regulation of TIMP-1 synthesis.204 In contrast, other studies suggested that endogenous IL-10 may not significantly contribute to fibrosis, or may even exert anti-fibrotic actions. In a model of reperfused infarction, genetic loss of IL-10 had no significant effects on scar formation, myofibroblast infiltration and adverse remodelling.207 In a model of non-reperfused MI, IL-10 was found to inhibit fibrosis.208 Moreover, in a model of pressure overload, endogenous IL-10 derived from haematopoietic cells inhibited fibrosis, through actions attributed to attenuated maturation of fibroblast progenitors.209 What is the basis for the conflicting evidence? The in vivo effects of IL-10 in the myocardial fibrotic response may be dependent on the balance between anti-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic actions. IL-10-mediated suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression may inhibit downstream activation of fibrogenic pathways and, depending on the context, may outweigh any pro-fibrotic actions.

5.4 The TGF-β superfamily

5.4.1 TGF-βs in cardiac fibrosis

TGF-β is the best characterized fibrogenic growth factor.210,211 In mammals, the TGF-β subfamily is comprised of three isoforms (TGF-β1, 2, and 3)212 that signal through the same receptors and share common cellular targets, but exhibit distinct patterns of regulation and different affinities for their receptors and co-receptors. Thus, the three isoforms likely play different roles in the pathophysiology of fibrotic conditions. Unfortunately, isoform-specific actions have not been systematically studied in vivo. Thus, our knowledge on the role of TGF-β in fibrotic conditions is primarily derived from studies investigating the common downstream signalling pathways of the three isoforms. TGF-β induction and activation has been consistently demonstrated in several different models of cardiac fibrosis,205,213,214 and in human hearts with fibrotic cardiomyopathic changes.215,216

Although many different cell types (including macrophages, fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, and platelets) can produce de novo large amounts of TGF-β in the injured heart, TGF-β signalling in injured tissues is predominantly regulated through activation. The mammalian heart contains latent stores of TGF-β that cannot associate with TGF-β receptors. Injury results in rapid activation of TGF-β, providing a mechanism for appropriate spatially-restricted stimulation of the reparative TGF-β response. Pericellular activation of TGF-β in sites of injury involves several different molecular signals, including proteases,217–219 matricellular proteins,214,220 and integrins.221 The relative contribution of specific TGF-β activating signals in the fibrotic heart has not been investigated.

The role of TGF-β in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis is supported by several lines of evidence. First, gain-of-function studies showed that myocardial overexpression of TGF-β1, and constitutive expression of an activated mutant TGF-β protein trigger ventricular fibrosis, associated with de novo deposition of structural ECM proteins and activation of a matrix-preserving programme.222–224 Surprisingly, transgenic mice with a large proportion of constitutively active TGF-β1 due to a mutation that blocks covalent tethering of the TGF-β1 latent complex to the ECM exhibited only atrial fibrosis,225 possibly reflecting exaggerated responses of atrial fibroblasts to the fibrogenic effects of TGF-β. Second, genetic loss-of-function studies suggest that endogenous TGF-β signalling plays an important role in cardiac fibrosis. Heterozygous TGF-β1+/− deficient mice had delayed interstitial fibrotic changes as they aged.226 Moreover, mice with fibroblast-specific loss of the type I or type II TGF-β receptors (TβRI or TβRII) had reduced cardiac fibrosis in a model of left ventricular pressure overload227 suggesting that fibrotic remodelling involves the activation of the TGF-β signalling cascade. Third, pharmacologic TGF-β inhibition strategies attenuated fibrosis in a model of pressure overload,228 and in the fibrotic cardiomyopathy due to Chagas’ disease.229

TGF-β exerts a broad range of direct effects on fibroblasts that may contribute to the pathogenesis of fibrosis. TGF-β stimulation potently induces myofibroblast conversion,230 and increases ECM protein synthesis by activated fibroblasts.231 Moreover, TGF-β increases expression of integrins,232 and shifts the protease/anti-protease balance towards a matrix-preserving phenotype by inducing protease inhibitors, such as Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor (PAI)-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)1212,233 and by suppressing MMP synthesis.234 It should be noted that the effects of TGF-β on cardiac fibroblast proliferation are dependent on the context. Some studies have reported that TGF-β stimulates proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts,235 whereas other investigations demonstrated anti-proliferative effects.231,236 The contrasting findings likely reflect differences in the state of differentiation of fibroblast populations,237 the presence or absence of other growth factors, and the matrix environment.

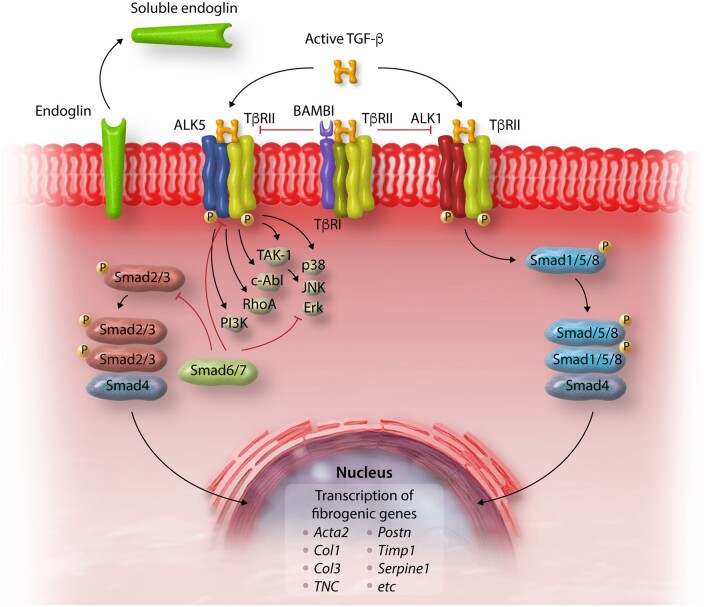

Considering the broad effects of TGF-β in many cellular responses, and the need to develop strategies to specifically inhibit its fibrogenic actions, dissection of pro-fibrotic TGF-β-driven molecular signals has attracted significant interest. TGF-β signals through a series of intracellular effector proteins, the Smads, and through Smad-independent pathways (Figure 4). In vitro and in vivo evidence suggests that both canonical Smad-dependent cascades and non-canonical Smad-independent signalling contribute to fibroblast activation in fibrotic hearts. In vivo studies have demonstrated that Smad3 signalling is critically involved in activation of reparative fibroblasts following MI, inducing ECM protein synthesis, integrin transcription, and α-SMA expression,231,233 and contributing to the formation of an organized scar.232 Smad3 signalling in infarct myofibroblasts restrained cell proliferation,231–233 generating well-aligned arrays of activated myofibroblasts that preserve the structural integrity of the infarcted heart through activation of a reparative integrin-reactive oxygen species (ROS) axis.232 These findings highlight the reparative function of fibroblasts in the presence of significant cardiomyocyte loss. In contrast, Smad2 does not seem to play a major role in mediating fibroblast activation in fibrotic hearts.238 The contrasting effects of Smad2 and Smad3 may reflect differences in their patterns of activation and nuclear translocation following TGF-β stimulation, or distinct interactions with transcriptional regulators in the nucleus. On the other hand, some actions of TGF-β on cardiac fibroblasts may involve activation of Smad-independent p38 MAPK, ERK, or Transforming Growth Factor-β-activated kinase (TAK)1 signalling.114,239,240 However, considering the wide range of mediators that signal through these common kinase pathways, the relative contribution of TGF-β in their activation is unclear.

Figure 4.

Regulation of TGF-β signalling in cardiac fibrosis. Active TGF-β binds to type II and type I receptors, activating downstream Smad-dependent signalling cascades and Smad-independent pathways. TGF-β binding to the ALK5 type 1 receptor and downstream activation of Smad3 signalling, induces a matrix-preserving programme in cardiac fibroblasts and plays an important role in their activation following cardiac injury. In contrast, the role of ALK1/Smad1/5 signalling in regulation of fibroblast phenotype is poorly understood. Activation of Smad-independent pathways, including RhoA and MAPK signalling, mediates some of the effects of TGF-β in cardiac fibroblasts. Endogenous pathways for negative regulation of TGF-β cascades may protect from excessive or unrestrained fibrotic responses. The inhibitory Smads (Smad6/7), pseudoreceptors such as BAMBI, and soluble endoglin may serve as endogenous inhibitors of TGF-β signalling, limiting pro-fibrotic responses.

In addition to the direct actions of TGF-β on transcription of fibrosis-associated genes, some TGF-β-mediated fibrogenic effects may be mediated through induction of other secreted mediators. It has been suggested that TGF-β-mediated fibrosis may require downstream release of the matricellular protein CCN2/connective tissue growth factor.241 However, experiments using both loss- and gain-of-function approaches have challenged the in vivo significance of CCN2 in mediating the pro-fibrotic actions of TGF-β.224,242 The gp130 cytokine IL-11 has also been suggested to act as a critical downstream signal mediating TGF-β-driven fibrosis not only in the heart187 but also in other organs.188,189

Considering its broad cellular targets, some of the in vivo fibrogenic actions of TGF-β may involve indirect activation of other cell types. Direct in vivo evidence supporting this notion is lacking. Although myeloid cell-specific loss of Smad3 markedly attenuated TGF-β synthesis by macrophages, collagen deposition in the infarct and interstitial fibrosis in non-infarcted areas was not affected in a model of non-reperfused MI.243

5.4.2 Other members of the TGF-β superfamily

Information on the role of other members of the TGF-β superfamily in cardiac fibrosis is limited. Several members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) subfamily, including BMP2, BMP4, and BMP6, are up-regulated in infarcted hearts and may exert pro-inflammatory actions244; however, their potential involvement in the fibrotic response has not been investigated. Two members of the BMP subfamily, BMP7 and BMP10, have been reported to exert anti-fibrotic effects. Several independent investigations suggested that BMP7 administration attenuates collagen deposition in models of pressure overload and diabetic cardiomyopathy.22,245,246 The antifibrotic effects were attributed to blockade of TGF-β signalling and were associated with attenuated endothelial to mesenchymal transition.22,247 Moreover, gain-of-function studies have suggested that BMP10 may exert anti-fibrotic actions in the isoproterenol-treated heart.248 Whether these effects involve direct modulation of fibroblast phenotype, or indirect actions involving other cell types is unclear.

The follistatins bind with high affinity with TGF-β superfamily proteins (such as activins, BMPs and growth differentiation factors) disrupting their function. In addition to these effects, several members of the follistatin family have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis through direct activation of cardiac fibroblasts. Follistatin-like 1 activated a reparative programme in infarct fibroblasts through ERK signalling and protected the infarcted ventricle from cardiac rupture.249In vitro studies have suggested that follistatin-like 3 may also have fibroblast-activating effects.250

5.5 The PDGFs

The PDGFs (PDGF-AA, -BB, AB, CC, and DD) are homo- or hetero-dimeric growth factors that signal through two different receptors: PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β. Abundant evidence suggests that PDGF isoforms play a role in activation of the fibrotic response following myocardial injury. PDGF-A, PDGF-C, and PDGF-D have potent fibrogenic effects on the myocardium, mediated through direct actions and, at least in part, through up-regulation of TGF-β.251In vitro, PDGF-A and PDGF-D potently stimulate cardiac fibroblast proliferation and ECM protein synthesis.252,253In vivo, overexpression of PDGF-A or PDGF-D cause marked fibrotic cardiomyopathy associated with fibroblast activation.254,255 PDGF isoforms and PDGFRs are up-regulated in fibrotic hearts256 and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrotic responses. Consistent with its high expression in fibroblasts, PDGFR-α activation has been consistently involved in myocardial fibrosis. In a model of reperfused MI, treatment with a neutralizing anti-PDGFR-α antibody attenuated collagen deposition.256 Moreover, in pressure-overloaded hearts, PDGFR-α blockade reduced atrial fibrosis and protected from atrial fibrillation.257 Although such effects likely reflect direct inhibition of PDGFR − α-driven fibroblast activation, actions on other cell types cannot be excluded. Moreover, broad PDGFR blockade through administration of the non-specific small molecule kinase inhibitor imatinib was found to reduce interstitial fibrosis in models of MI258 and viral myocarditis.259

The PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β axis on the other hand is predominantly activated in vascular mural cells; thus, its fibrogenic actions may be more limited. PDGFR-β activation through an integrin β1-mediated mechanism was suggested to augment fibroblast proliferation and matrix synthesis in a model of cardiac pressure overload.260 However, mice overexpressing PDGF-B had only focal fibrotic changes, much less severe than PDGF-A overexpressing animals.255 Neutralization of PDGFR-β signalilng in infarcted mice reduced collagen deposition, but had much more impressive effects in perturbation of vascular maturation, highlighting the significance of PDGFRβ actions on vascular mural cells.256,261

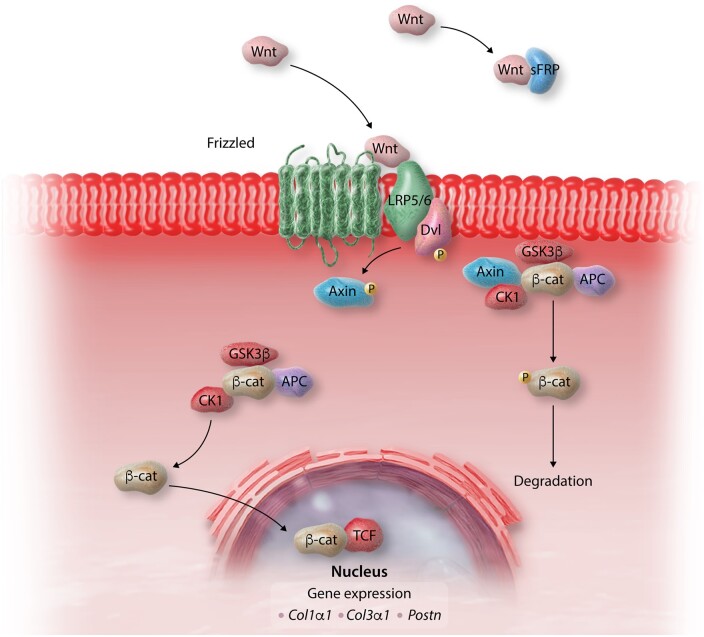

5.6 The Wnt/β-catenin axis

In mammals, the Wnt signalling pathway is involved in embryonic development, but becomes quiescent in adult low turnover tissues, such as the heart. Members of the Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins are secreted following injury,53,262 bind to Frizzled family transmembrane receptors and initiate signalling through canonical pathways involving β-catenin, or through non-canonical pathways. Activation of the canonical β-catenin pathway requires Wnt-mediated dissociation of the β-catenin degradation complex, stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm, followed by nuclear translocation and interactions with transcription factors and transcriptional co-activators that regulate gene expression (Figure 5). Wnt/β-catenin activation has broad effects on a wide range of cellular responses,263 involved in repair, remodelling and regeneration.

Figure 5.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays an important role in cardiac fibrosis. In the absence of Wnt, cytoplasmic β-catenin is continuously degraded by the Axin complex, which involves casein kinase 1 (CK1), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3). Wnts are released in injured and remodelling myocardium and bind to Frizzled transmembrane receptors and their co-receptors LRP5/6. This complex recruits the scaffolding protein Dishevelled (Dvl) and inhibits axin-mediated β-catenin phosphorylation, which is required for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Thus, through the effects of Wnts, β-catenin is stabilized and translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with T cell Factor (TCF), regulating gene expression. Activation of β-catenin in cardiac fibroblasts has been implicated in fibrogenic signalling and in paracrine hypertrophic effects on cardiomyocytes. Secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRP) bind to Wnts and inhibit their actions.

In the injured heart, Wnt signalling is activated in many different cell types and has been suggested to contribute to reparative, regenerative and fibrotic responses. Secretion of Wnt proteins may be mediated through growth factors, such as TGF-β,40 and requires post-translational modification by the acyltransferase Porcupine (Porcn), a process that supplies a single fatty acid adduct necessary for Wnt protein secretion. In vitro, Wnt family members promote conversion of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and stimulate cytokine synthesis.264,265In vivo, administration of a small molecule inhibitor that disables Porcn, thus preventing secretion of Wnt proteins, reduced fibrosis in a model of MI.266 Wnt-mediated fibroblast activation in the injured heart likely involves signalling through the β-catenin pathway.267,268 Cell-specific genetic loss-of-function studies demonstrated that fibroblast-specific activation of β-catenin mediates both fibrosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in the pressure-overloaded heart.268 The downstream molecular targets of the Wnt/β-catenin axis remain unknown. It should be emphasized that Wnt-induced fibrogenic actions may not be due exclusively to direct fibroblast activation, but may also involve effects on other cell types, including cardiomyocytes, vascular cells, and immune cells.269,270

5.7 Endothelin-1

Endothelin (ET)-1 exerts potent fibrogenic effects, acting downstream of cytokines and neurohumoral mediators,271 thus linking inflammation and fibrosis.272 Angiotensin II and TGF-β induce ET-1 in vitro,273 and in experimental models of cardiac fibrosis.274 Up-regulation of ET-1 is consistently noted in many fibrosis-associated cardiac pathologies, including MI, heart failure, hypertensive heart disease, diabetes, and ageing.275–277 Fibrogenic effects of ET-1 in myocardial disease are suggested by both genetic models and by pharmacologic inhibition studies. Cardiac ET-1 overexpression in mice induced myocardial fibrosis associated with both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.278 Moreover, endothelial-specific loss of ET-1 attenuated fibrosis in a model of angiotensin II infusion.279 In experimental animal models of hypertensive heart disease and of reparative myocardial fibrosis, ET-1 inhibition reduced fibrotic remodelling.280,281 The anti-fibrotic effects of ET-1 blockade may have therapeutic implications. Endothelin receptor antagonists reduced myocardial stiffness, suppressing collagen I deposition and attenuating interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in rat and mouse models of aldosterone infusion that recapitulate features of human HFpEF.282,283

To what extent the fibrogenic effects of ET-1 are due to direct activation of fibroblasts vs. indirect actions on other cellular targets, such as endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes, remains unknown. In vitro, cardiac fibroblasts are highly responsive to ET-1 stimulation, exhibiting increased proliferative activity,284 accentuated ECM protein synthesis,285 and resistance to apoptosis.286 In a model of type 1 diabetes, ET-1-mediated EndMT has been suggested to contribute to the myocardial fibrotic response.287 Unfortunately, the evidence supporting this specific cellular mechanism was limited to dual staining with non-specific markers for fibroblasts and endothelial cells.

5.8 The ECM as a modulator of the fibrosis-associated cellular response

The profound changes in the amount and biochemical profile of the ECM proteins in fibrotic hearts, not only has consequences on cardiac function and conduction of the electrical impulse, but may also play a major role in regulation of cellular responses and in transduction of fibrogenic signalling pathways. Generation of matrix fragments (termed matricryptins and matrikines) by activated proteases ,288 deposition of provisional matrix proteins (such as fibronectin and fibrin), and induction of matricellular macromolecules that enrich the interstitial matrix are the best-documented mechanisms for matrix-mediated regulation of fibrogenic cellular responses in injured hearts. Cardiac remodelling is intricately regulated by this crosstalk between the cells and the surrounding ECM: the cells secrete ECM molecules with regulatory properties, but also respond to changes in the matrix environment by interacting with specific functional domains of ECM macromolecules.65,289

5.8.1 Matrikines and matricryptins

Many forms of cardiac injury, including myocardial ischaemia and pressure overload, induce rapid release and activation of proteases that degrade the native ECM, generating bioactive peptides termed matrikines and matricryptins.290,291 Matrikines are fragments of ECM macromolecules with biological properties distinct from those of the full-length form of the molecule. The term matricryptin is used to describe a matrikine that requires proteolytic processing to expose a bioactive functional domain.292 These matrix fragments bind to cell surface receptors on fibroblasts, vascular cells or immune cells, and can modulate the fibrotic response. In a protease-rich environment, all constituents of the cardiac ECM, (including collagens I, IV, and XVIII, elastin, fibronectin, hyaluronan, and tenascin-C) can generate fragments.288,293 Most of the evidence on the role of ECM fragments in tissue injury suggests actions that regulate angiogenesis, and effects on immune cells that activate inflammatory signalling cascades,291,294 and may indirectly promote fibrosis. In addition to these actions, in vitro studies have demonstrated that matrix fragments may also modulate fibroblast phenotype, potentially exerting direct actions in cardiac fibrosis.295–298 However, the in vivo role of specific matrix fragments in fibrotic myocardial conditions has not been investigated.

5.8.2 The provisional matrix components: fibrin and fibronectin

Myocardial injury increases microvascular permeability, causing extravasation of plasma fibrinogen and fibronectin and generating a provisional matrix network that is particularly prominent during the inflammatory and proliferative phase of MI.299 The provisional matrix provides a dynamic substrate for interactions between integrins expressed by fibroblasts and immune cells, and functional domains of fibrin and fibronectin, thus facilitating cell migration and transducing activating signals.300,301 The ED-A variant of cellular fibronectin plays an important role in activation of TGF-β and in subsequent myofibroblast conversion.47,302–304 Moreover, the plasma-derived provisional matrix is later enriched with cell-derived matrix components, including non-fibrillar collagens, cellular fibronectin, proteoglycans and a wide range of matricellular macromolecules.

5.8.3 Deposition and cross-linking of fibrillar collagens

Secretion of the major fibrillar collagens, collagen I and collagen III is the hallmark of cardiac fibrosis.8,31 The relative amounts of type I vs type III collagen fibres may be important in regulation of the mechanical properties of the myocardium. Collagen I fibres are thicker and stiffer; in contrast the finer reticular collagen III fibres are more compliant. The accentuated and prolonged up-regulation of type I collagen in hypertensive hearts has been suggested to increase myocardial stiffness.305,306 Moreover, in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy enrichment of the cardiac ECM with collagen I fibres was associated with reduced ventricular compliance.307 Other members of the fibrillar collagen subfamily may play important regulatory roles in cardiac fibrosis. Collagen V is known to regulate collagen fibril diameter and assembly. Recent studies in a model of MI suggested that collagen V induction in healing scars restrains fibroblast activation by regulating expression of mechanosensitive integrins.308

Following their secretion by activated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, procollagen chains are processed, assembled into fibrils and cross-linked. Cross-linking enzymes, such as the members of the lysyl-oxidase (LOX) and transglutaminase (TG) families play a crucial role in formation of intermolecular covalent links between collagen chains. The LOX family is the main enzymatic system responsible for cross-linking of extracellular collagen in fibrotic hearts309–313; its members act on specific lysine or hydroxylysine residues, catalysing allysine aldehyde formation, leading to subsequent spontaneous formation of the cross-links. TG2, (also known as tissue transglutaminase) is the highest-expressed member of the transglutaminase family in remodelling hearts314–316 and catalyzes formation of an isopeptide bond between the ε-amino group of a lysine and the γ-carboxamide group of a glutamine. In addition to its enzymatic effects, TG2 may also regulate fibroblast phenotype through non-enzymatic mechanisms, modulating integrin-dependent responses.317 Cross-linking is a major determinant of collagen fibre stiffness and resistance to degradation and has major implications in regulation of cardiac function.318 Although some matrix cross-linking activity is required to provide mechanical support and to prevent chamber dilation under conditions of stress319 excessive collagen cross-linking increases myocardial stiffness and can contribute to the pathogenesis of diastolic dysfunction.320

5.8.4 Non-fibrillar collagens

In addition to the increased synthesis and deposition of structural fibrillar collagens, cardiac fibrosis is also associated with overexpression of several non-fibrillar collagens, including collagen IV, VI, and VIII.321,322 Fibrogenic growth factors, such as TGF-β, are responsible for induction of non-fibrillar collagens in activated fibroblasts and in fibrotic hearts. Collagen VI and collagen VIII have been implicated in fibroblast activation in experimental models of cardiac remodelling. Collagen VI promotes myofibroblast conversion,323 and enhances fibrosis in experimental MI.324 Collagen VIII stimulates fibroblast migration and enhances TGF-β synthesis, accentuating fibrosis in the pressure-overloaded heart.325

5.8.5 Matricellular proteins, galectins and proteoglycans