Abstract

The symbiotic relationship between an animal and its gut microbiota is known to influence host neural function and behavior. The mechanisms by which gut microbiota influence brain function are not well understood. This study measures the impact of gut microbiota on olfactory behavior of Drosophila larvae and explores possible mechanisms by which gut microbiota communicate with neural circuits. The microbiota load in Drosophila larvae was altered by treating them with antibiotics or probiotics. Control larvae and larvae with altered microbiota loads were subjected to olfactory assays to analyze the chemotaxis response of larvae to odorants. Larvae treated with antibiotics had reduced microbiota load and exhibited reduced chemotaxis response toward odorants compared to control animals. This behavioral phenotype was partially rescued in larvae treated with probiotics that resulted in partial recovery of microbiota loads. Expression levels of several olfactory genes in larvae subjected to different treatments were analyzed. The results suggest that the expression of certain components of the GABA signaling pathway is sensitive to microbiota load. The study concludes that the microbiota influences homeostatic mechanisms in the host that control GABA production and GABA-receptor expression, which are known to impact host olfactory behavior. These results have implications for understanding the bidirectional communication between a host organism and its microbiota as well as for understanding the modulation of olfactory neuron function.

Keywords: GABA signaling, olfaction, olfactory receptor neurons

Introduction

A wealth of recent articles highlight the bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and the brain (Aziz and Thompson, 1998; Bercik et al., 2012; Cryan and Dinan, 2012; Konturek et al., 2004; Mayer, 2011; O’Mahony et al., 2009; Rhee et al., 2009). The symbiotic relationship that has developed between an organism and its microbiota has become an increasingly popular topic of interest, contributing to the NIH launch of the Human Microbiome Project in 2008 (hmpdacc. org). Estimates report that the number of bacterial cells within the human body are at least equivalent to the number of human cells (Sender et al., 2016). These populations contribute to homeostasis, or conversely disease states, of our digestive tract, nasal passageways, urogenital tract, mouth, and skin.

With capabilities of modulating host gene expression (Lutay et al., 2013), an unbalanced microbiome has the potential to dramatically affect the host in which it lives. Microbiota impacts mating behavior in Drosophila melanogaster (Sharon et al., 2010). Independent studies have also measured the impact of Drosophila microbiota on host longevity. Antibiotic treatment to remove gut bacteria within the first week of adult life led to reduced longevity; however, removal of gut bacteria 30 days into adulthood led to increased longevity (Brummel et al., 2004). Antibiotic-treated flies have altered energy homeostasis, carbohydrate allocation patterns, and developmental effects compared to control flies (Ridley et al., 2012). The presence of microbiota ensures viability and sustains growth when the host is malnourished (Shin et al., 2011).

An unbalanced microbiome also has the potential to impact brain function in its host. Bacteria may signal to the brain through multiple routes, including neural, metabolic, endocrine, and immune pathways. Studies with germ-free mice have demonstrated that the microbiota play a key role in modulating the levels and turnover of neurotransmitters and other factors within the host nervous system (Sampson and Mazmanian, 2015; Yang and Chiu, 2017). Several strains of gut bacteria known to colonize human and Drosophila intestines have been shown to be robust producers of the neurotransmitter GABA (γ-amino butyric acid; Barrett et al., 2012; Li and Cao, 2010; Yunes et al., 2016). A bacterial species that is often identified in both larval and human intestines, Lactobacillus brevis, is one of the most efficient producers of GABA among groups of lactobacillus strains (Barrett et al., 2012).

GABA is also an important neurotransmitter conserved throughout the animal kingdom. It plays an important role in the insect olfactory circuit. The enzyme GAD1 helps to produce GABA within the inhibitory local neurons (LNs) in the olfactory circuit from where it is secreted and received by GABA-receptors expressed on surrounding neurons (Wang, 2012; Watanabe et al., 2002). GABAB-receptor subunits, such as GABABR1, GABABR2, and GABABR3, are found at the axon terminals of the first-order olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) in Drosophila (Root et al., 2008). ORNs sense odorants in the environment and convey that information to downstream projection neurons (PNs; Harrison et al., 1996; Ng et al., 2002; Root et al., 2008). GABA signaling plays an important modulatory role during olfactory information processing (Wang, 2012). In insects, the antennal lobe is also immunoreactive to GABAAR (Harrison et al., 1996). While precise localization of GABAAR on the terminals of ORNs and/or PNs remains unclear, it could play a modulatory role. The production of GABA by the microbiome could potentially impact olfactory information processing in the peripheral olfactory circuit and thereby influence host olfactory behavior.

While several molecules, including GABA, released by the gut microbiota have been implicated in modulation of central and peripheral neurons in the host, the molecular mechanisms through which the microbiota influences brain function and physiology of the host are not well understood. In this light, the use of a simple model system to evaluate and clarify the impact of intestinal bacteria on their host’s behavior and physiology can be helpful. The relative simplicity of the fruit-fly gut microbiota (Erkosar et al., 2013), coupled to the genetic tractability of both the host and its commensals, allow one to focus on the basic principles and mechanisms governing their mutualistic association that are likely conserved throughout the animal kingdom.

This study measures the impact of gut microbiota on host olfactory behavior. We hypothesize that gut microbial load in the Drosophila larva influences larval olfactory behavior by influencing homeostatic mechanisms in the host that control GABA production and GABA-receptor expression. To address this hypothesis, we optimized a method to alter microbiota load in Drosophila larvae. We then compared the olfactory behavior of wild-type Drosophila larvae and larvae with different amounts of microbiota load. Finally, we performed gene expression analyses to explore possible mechanisms by which the microbiota influences host olfactory behavior.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

Animal care and use guidelines were followed for all experiments. A Canton-S (CS) line was used as the wild type line in behavioral experiments. Antibiotic-treated and probiotic-treated larvae used in this study were derived from CS flies using the protocol described below. Flies were grown in polypropylene bottles containing Nutri-Fly Bloomington formulation medium prepared according to manufacturer’s protocol (Genesee Scientific Inc.).

Generating antibiotic-treated and probiotic-treated larvae

Antibiotic media was prepared by adding Rifamycin (200 μg/mL; MP Biomedicals Inc.), Ampicillin (500 μg/mL; Alfa Aesar Inc.), Tetracycline hydrochloride (50 μg/lL; Alfa Aesar Inc.), and propionic acid (4.8 μL/lL Sigma-Aldrich Inc. St. Louis, MO) to 1.0 L of autoclaved fly-food media. The combination of antibiotics helps to eliminate bacteria, while propionic acid helps to eliminate mold growth in the media. After mixing, the antibiotic-treated media is poured into autoclaved polypropylene bottles under sterile conditions. To generate antibiotic-treated larvae, CS adults were allowed to feed on antibiotic-treated media for 48 h. Under sterile conditions, the adults were transferred to fresh antibiotic-treated media and allowed to lay eggs for a period of 48 h. Third-instar larvae generated (96 h after egg laying) were used in subsequent bacterial growth medium validation, PCR validation, and behavioral assays.

Probiotic media was prepared by adding a commercially available probiotic complex (American Health Inc.) to autoclaved fly food. The probiotic complex contains Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus brevis, and Bacillus lactis. One probiotic capsule was mixed with 2.0 mL of sterile distilled water. 400 μL of this solution (0.4 billion colony forming units) was added to each bottle of autoclaved, solidified fly food media 24 h before using the medium for egg laying. Antibiotic-treated flies were allowed to lay eggs on probiotic media for a period of 48 h. Third-instar larvae (96 h after egg laying) were tested to validate the germ +/− state of larvae and also used for PCR and behavioral experiments.

Validation of germ +/− state of Drosophila larvae

Bacterial presence was assayed using patching techniques. Individual third-instar larva from each test line were homogenized in 25 μL of sterile phosphate buffered saline (Life Technologies Inc.) using a sterilized pestle. The homogenate was then spread on to Luria broth plates (Fisher Scientific Inc.). Plates were incubated for three days at 37°C and monitored for bacterial growth. Each sample was categorized as “positive” if there were bacteria on the plate after three days, or otherwise denoted as “negative” if there were no bacteria on the plate. Each experimental condition was tested a minimum of eight times.

Bacterial presence was also assayed using PCR. Third-instar larvae (96 h after egg laying) were collected. Approximately 50 mg of larvae were homogenized in 180 μL ATL buffer (Qiagen Inc.) in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube using a handheld homogenizer and disposable pestle (VWR Inc.). DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc.) following the Qiagen supplementary protocol for insect DNA extraction. The extracted DNA was subjected to multiplex-PCR using primers specific to fly and bacterial genes and Apex Taq Master Mix (Genesee Inc.). The Or94a/b gene sequence that encodes olfactory receptors in D. melanogaster was used as a marker for Drosophila DNA, and primers that amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were used as a marker for nonspecific strains of bacterial DNA (Brummel et al., 2004). Five different bacterial strains were identified in the gut of Drosophila melanogaster larvae: L. brevis, L. fructivoran, A. pomorum, L. plantarum, and A. tropicalis (Wong et al., 2011). We obtained primers designed by Wong and colleagues in their study. These primers are unique to each of these strains’ bacterial 16S rRNA in order to evaluate the presence of specific bacteria (all primers are listed in Table 1). The PCR products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis to detect marker genes with Apex Bioresearch DNA Ladder III (Genesee Inc.). Images were obtained using a ChemiDoc Touch Imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Each assay was performed in three biological replicates.

Table 1.

DNA primers used in multiplex PCR reactions.

| Target | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Size (bp) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila Olfactory Receptor 94a | GTTAAACCAACGGCCACAAAG | CCTCCAGCCACATGAGTCC | 357 | PrimerBLAST |

| Drosophila Olfactory Receptor 94a&b | GTTAAACCAACGGCCACAAAG | CAGAACTTGACCAGCTTCCTCA | 2,381 | PrimerBLAST |

| Non specific Bacterial 16S rRNA | GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 1,500 | Brummel et al., 2004 |

| Lactobacillus brevis 16S rRNA | ACGTAGCCGACCTGAGAGGGT | AGCTTAGCCTCACGACTTCGCA | 955 | Wong et al., 2011 |

| Lactobacillus fructivoran 16S rRNA | TGGATCCGCGGCGCATTAGC | GCCCCCGAAGGGGACACCTA | 809 | Wong et al., 2011 |

| Acetobacter pomorum 16S rRNA | TGGGTGGGGGATAACACTGGGA | AGAGGTCCCTTGCGGGAAACA | 866 | Wong et al., 2011 |

| Acetobacter plantarum 16S rRNA | TCCATGTCCCCGAAGGGAACG | TGGATGGTCCCGCGGCGTAT | 821 | Wong et al., 2011 |

| Acetobacter tropicalis 16S rRNA | AGGGCTTGTATGGGTAGGCT | CAGAGTGCAATCCGAACTGA | 332 | Wong et al., 2011 |

Behavioral assay

Third-instar larvae (approximately 96 h after egg laying) were extracted from food using a high-density (15%) sucrose (Sigma Aldrich Inc.) solution. Larvae that floated to the surface of the sucrose solution were separated into a 1000 mL glass beaker and washed four times with distilled water. Washed larvae were allowed to rest for 10 min before being subjected to behavior assays. Temperature of the behavior room was maintained between 22°C and 23°C. Humidity of the room was maintained between 45% and 50% relative humidity (RH).

Two-choice assays were conducted as described previously (Kreher et al., 2008; Monte et al., 1989; Rodrigues and Siddiqi, 1978) to 4-hexene-3-one, ethyl acetate, and pentyl acetate (≥ 98% purity) diluted to 10−2 in paraffin oil (Sigma Aldrich Inc.). Briefly, Apex high purity Agarose (Genesee Scientific Inc.) gel was used to prepare the crawling surface for larvae during chemotaxis behavior experiments. Odor was added to a 6.0 mm filter disc (General Electric-Whatman) on one side of a 10 cm diameter Petri dish and the diluent (paraffin oil) was added to a filter disc on the opposite side. Odor gradients formed remain stable for the duration of the assay (Mathew et al., 2013). Approximately 50 third-instar larvae were placed in the center of the dish and allowed 5.0 min to disperse in the dark. After 5.0 min, the number of larvae on each half of the dish was counted to generate the response index (RI), calculated as RI = (S-C)/ (S+C). S represents the number of larvae that were on the half of the plate containing odorant and C is the number on the half containing the control disc. Ten assays were done in each group and the data are presented as RI ± SEM. To test for significance, ANOVA along with Bonferroni post-hoc tests were performed.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

Third-instar larval heads were dissected and collected in RNAlater (Thermo Scientific Inc.) on ice. Approximately 15 larval heads were homogenized in lysis buffer with the help of a handheld homogenizer. For each sample, the total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit with gEliminator columns (Qiagen Inc.). An additional gDNA digestion was conducted with TURBO DNA-free kit (Thermo Scientific Inc.). RNA quantification was performed using a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc.). The cDNA library from each sample was constructed using 1 lg of the total RNA using Superscript VILO Master Mix (Thermo Scientific Inc.) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Primer sequences for individual genes were either derived from literature, FlyPrimerBank (flyrnai.org) or designed using PrimerBlast (Table 2). Melt curve analyses were performed for each reaction to confirm specificity. Standard curves were used to calculate primer efficiency and were performed using a minimum of three serial dilutions of cDNA within an amplifiable range (0.32 −7.0 ng).

Table 2.

Primers used in qRT-PCR analysis.

| Target | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Size (bp) | Spans exon? | Primer source | Primer efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APPL | AGTGGAGTTCGTCTGCTGTC | TGGCGCTATTGATCTGAGCTG | 101 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP32134 | 98.30% |

| GABAAR | CACAGGCAACTATTCGCGTTT | GCGATTGAGCCAAAATGATACC | 130 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP25107 | 97.30% |

| GABABR1 | GATGTCAACAAGCAGCCAAATC | CGGGCTCACACTCACTGTC | 76 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP15543 | 104.20% |

| GABABR2 | CGCCTTGGGTCACGTTAATGA | GCATTGCACTGAGTGTCGTTC | 84 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP22487 | 103.60% |

| GABABR3 | TGCTGCTCGGACTCTTTGAG | AGCTCCCAATTCGCTCAGAC | 71 | No | PrimerBLAST | 95.00% |

| Elongation Factor 1 | GCGTGGGTTTGTGATCAGTT | GATCTTCTCCTTGCCCATCC | 125 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP5891 | 92.10% |

| Synaptotagmin | TCCCTATGTCAAGGTGTACTTGC | GTTGAAGACCGGACTCAGTGT | 88 | No | FlyPrimerBank: PP5891 | 104.80% |

| Nervana 2 | TCGAATGACTTGCCCGCGAA | GCCCTCGCACGATACCCAAA | 108 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP5891 | 99.40% |

| GAD1 | TGAATCCCAACGGGTATAAACTG | TCACTGTTGTGGGCATGAGAT | 75 | Yes | FlyPrimerBank: PP383 | 109.90% |

Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out to quantify the expression of several Drosophila genes. A 10 μL qRT-PCR reaction included 1 ng/lL cDNA template, 0.4 μM of each primer and SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The qRT-PCR was performed on a BIO-RAD CFX96 C1000 Touch™ Real-Time PCR detection system with thermal cycling conditions as follows: an initial denaturation of 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Each qRT-PCR was conducted in technical triplicates for each sample from three biological replicates. Data analyses were performed using the BIO-RAD CFX Manager Software (ver 3.1) and presented as relative normalized expression ± SEM. Expression data were normalized to Appl, Nrv2, and Syt1 gene expression. The software measured the collective reference gene expression stability yielding a mean coefficient variance of 0.1138 and a mean M value, a measure of reference gene expression stability, of 0.2677. The proprietary BIO-RAD CFX software determines mean values and standard deviations and statistical differences were evaluated using t-tests and one-way ANOVA.

Results

Microbiota load is reduced in antibiotic-treated larvae

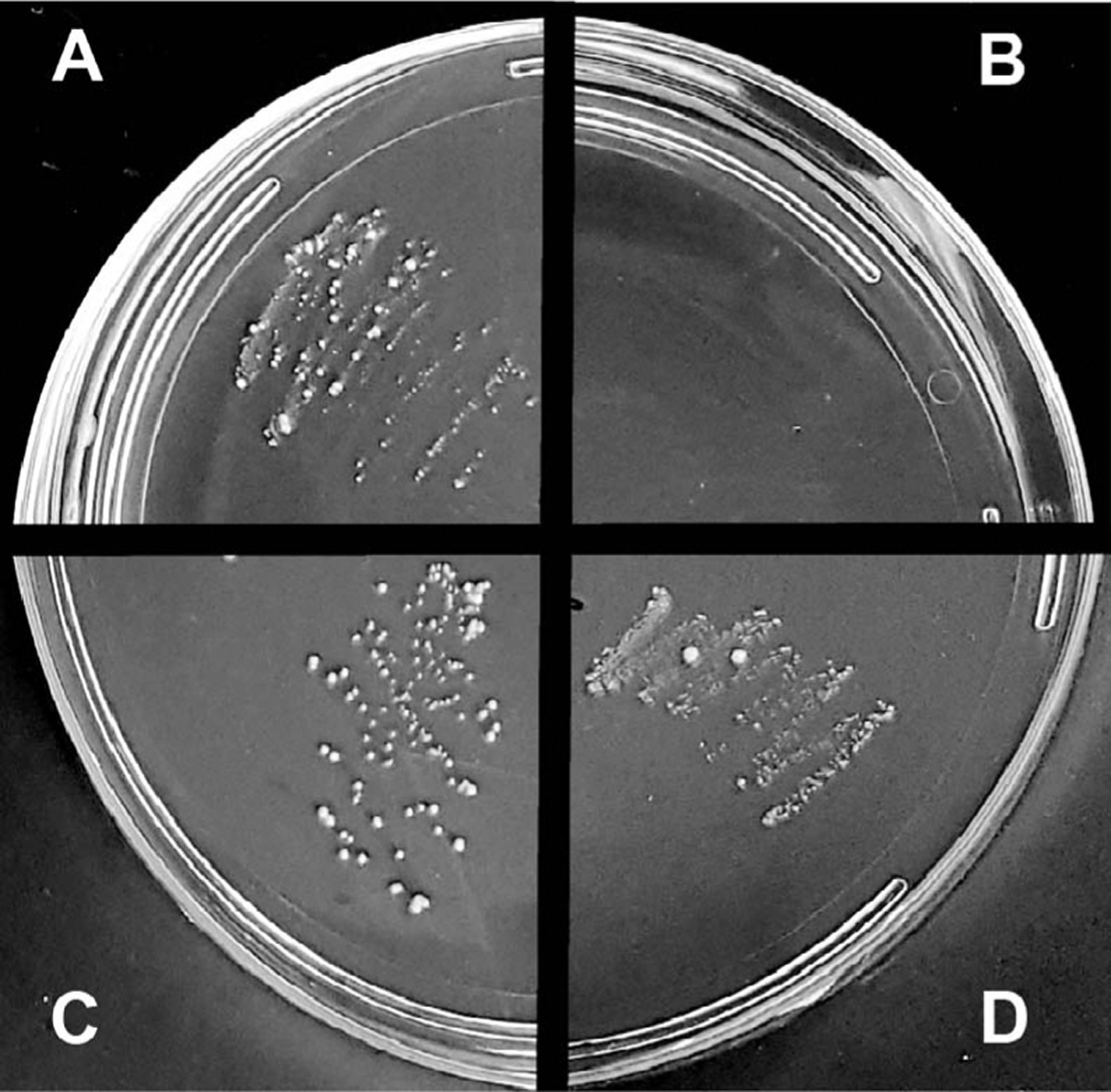

The presence of bacteria was assayed in two different ways to confirm that they were eliminated or reduced in antibiotic-treated larvae. Growth of bacteria on LB plates indicated the presence of microbiota load in homogenate from our positive control (wild-type larvae fed normal food; Fig. 1A) while complete absence of bacterial growth indicated zero or reduced microbiota load in the homogenate from our test-larvae (wild-type larvae fed antibiotic containing food; Fig. 1B). Homogenates were also tested from larvae of antibiotic-treated parents that laid their eggs on autoclaved fly food without (Fig. 1C) or with (Fig. 1D) probiotic supplementation. The plate assay revealed the presence of bacteria in both these homogenates.

Figure 1. Monitoring microbiota load in larvae using a bacterial growth medium.

Each quadrant represents homogenate from a single larvae grown on normal food (A), larvae grown on antibiotic food (B), larvae from antibiotic-treated parents grown on normal food (C), and probiotic food (D). The image is a representative image from 8 separate trials.

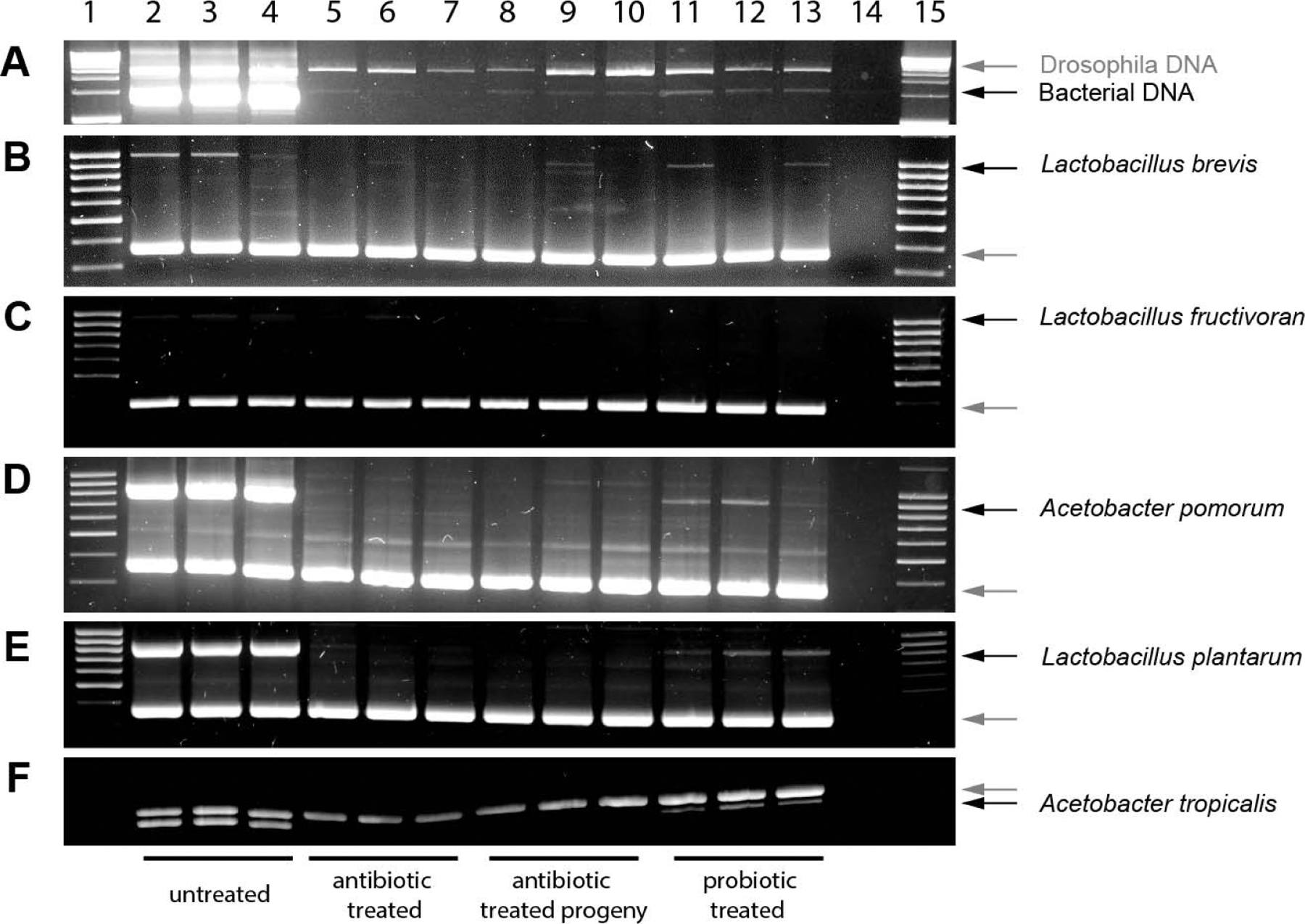

Multiplex PCR was used to amplify bacteria- and Drosophila-specific DNA from total DNA isolates from larvae. Drosophila DNA amplicons are present in all samples as a positive PCR control (Fig. 2A–F). The ‘minus-template’ control (lane 14) confirms the absence of Drosophila and Bacterial DNA in the PCR reactions. Non-specific bacterial 16s amplicons were present in larvae fed normal food as well as larvae from antibiotic-treated parents subsequently grown on sterile fly food with or without probiotic, but not present in larvae raised on antibiotic-treated medium (Fig. 2A). In order to verify the presence of individual bacterial strains (L. brevis, L. fructivoran, A. pomorum, A. plantarum, and A. tropicalis), bacterial 16s rRNA primers specific to each individual strain were used as marker genes (Wong et al., 2011; Table 1). L. brevis 16s rRNA (Fig. 2B) is amplified across all samples except the antibiotic-treated samples where the amplicon is consistently negative in all replicates. L. fructivoran 16s rRNA (Fig. 2C) is poorly amplified throughout all replicates. A. pomorum, L. plantarum, and A. tropicalis 16s rRNA (Fig. 2D–F) are each amplified in the untreated and probiotic-treated larval replicates but not in the antibiotic-treated larvae or their progeny.

Figure 2. Monitoring presence of microbiota in larvae using multiplex PCR of Drosophila and bacterial DNA.

Multiplex PCR reactions containing primers for Drosophila (grey arrows) and bacterial (black arrows) targets were performed on larval DNA samples. Nonspecific bacterial 16S (A), L. brevis (B), L. fructivoran (C), A. pomorum (D), L. plantarum (E), and A. tropicalis (F) were targeted separately. Lanes were loaded as follows: larvae grown on normal food (lanes 2–4), larvae grown on antibiotic food (lanes 5–7), and larvae from antibiotic-treated parents grown on normal (lanes 8–10), and probiotic food (lanes 11–13) minus-template control (lane 14), DNA ladder (lanes 1, 15).

Microbiota load impacts olfactory behavior

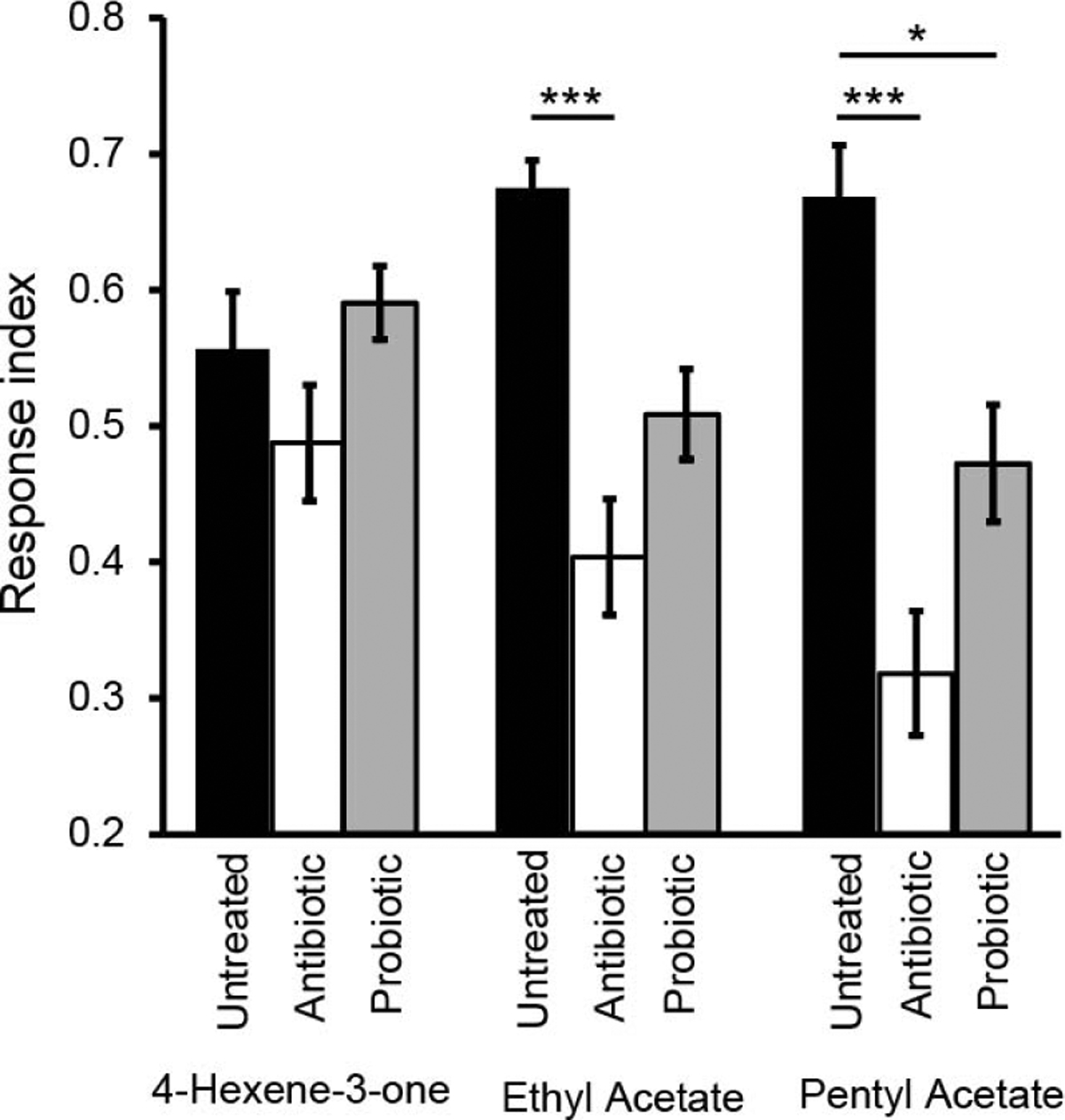

Behavioral responses of larvae with different microbiota loads to three odorants were measured. These odorants were selected based on their ability to elicit strong, specific physiological responses from one or few ORNs (ORN42a::4-Hexen-3-one, ORN47a::pentyl acetate, ORN42a & 42b::ethyl acetate; (Kreher et al., 2008; Mathew et al., 2013). Similar trends in behavior were observed for the three odorants tested (Fig. 3). Untreated larvae were strongly attracted to each of the three odorants (4-hexene-3-one; RI = 0.56 ± 0.13; ethyl acetate; RI = 0.68 ± 0.02; and pentyl acetate; RI = 0.67 ± 0.04). Antibiotic-treated larvae showed reduced attraction to the odor 4-hexene-3-one (RI = 0.49 ± 0.04) and significantly reduced responses to ethyl acetate (RI = 0.40 ± 0.04; p < 0.001) and pentyl acetate (RI = 0.32 ± 0.05; p < 0.001) compared to untreated larvae. Larvae from antibiotic-treated parents grown on probiotic food showed partial rescue of olfactory behavior to all three odors (4-hexene-3-one, RI = 0.59 ± 0.02; ethyl acetate, RI = 0.51 ± 0.03; pentyl acetate, RI = 0.47 ± 0.04) compared to antibiotic-treated larvae. Only in the case of pentyl acetate, the RI of the probiotic treated larvae remained significantly different from the untreated larvae (p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Microbiota load impacts larval olfactory behavior as assayed in a two-choice small-format paradigm.

Two-choice behavior paradigm were performed on all larval treatments for odors 4-Hexene-3-one, ethyl acetate, and pentyl acetate; mean response indices (RI) are shown. Each bar represents RI ± SEM (n = 10). ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-hoc test (* = p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001) was performed to test for significance.

To control for the effect of antibiotics in the antibiotic-treated medium, behavior of antibiotic-treated larvae were compared to antibiotic-treated larvae transferred to regular food for one generation. No significant changes in behavior response were observed to 4-hexene-3-one (RI = 0.50 ± 0.04), ethyl acetate (RI = 0.43 ± 0.11) nor pentyl acetate (RI = 0.35 ± 0.04) compared to larvae grown directly on antibiotic medium (p > 0.05). These results rule out any effect of antibiotics in the growth medium on reduction of olfactory behavior observed in antibiotic-treated larvae compared to wild-type larvae.

Microbiota load alters levels of GABA signaling components

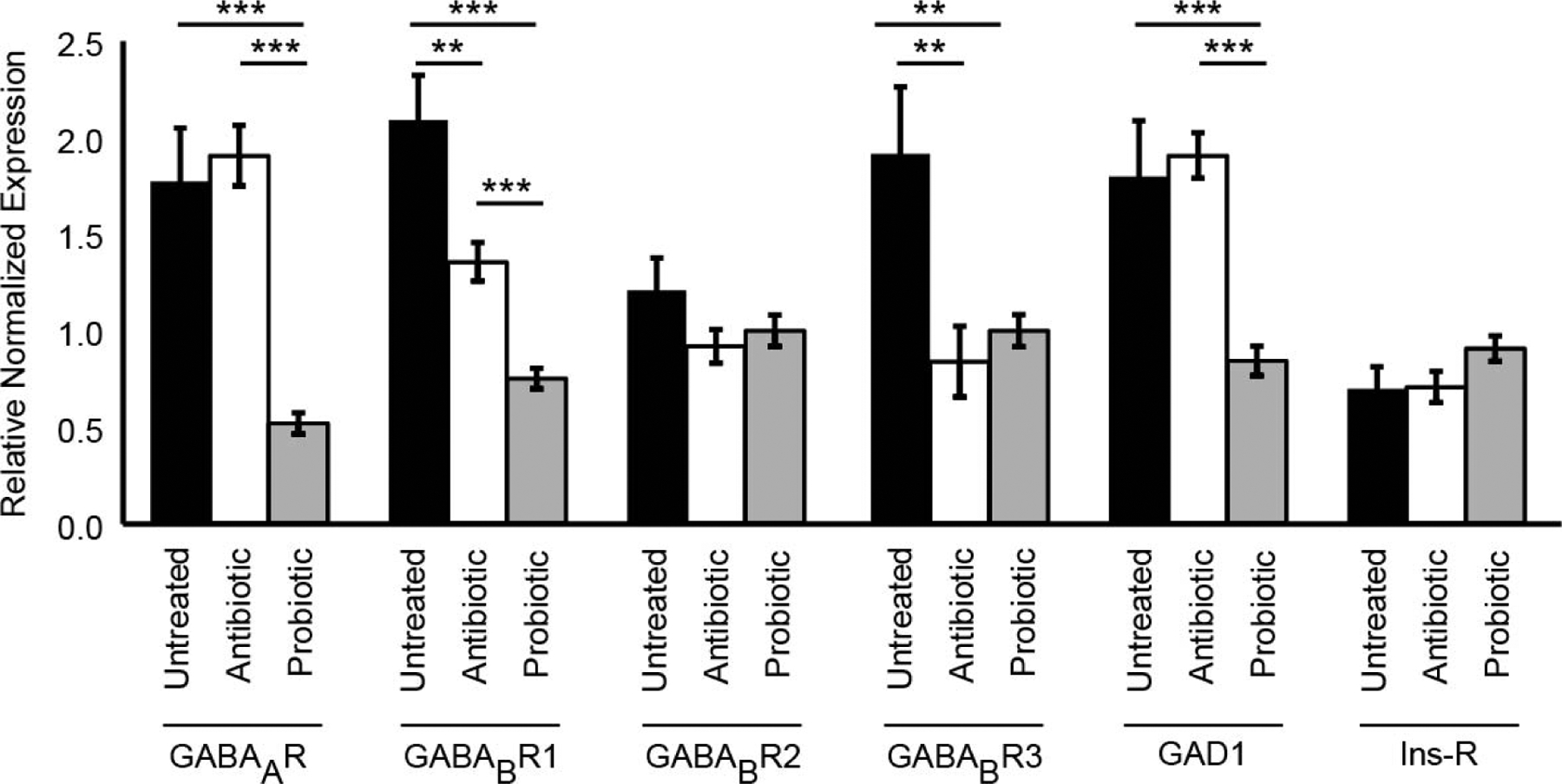

We used qRT-PCR to quantify the expression levels of GAD1, GABAAR, GABABR1, GABABR2, and GABABR3 RNA in wild-type larvae, antibiotic-treated larvae, and probiotic-treated larvae. Antibiotic-treated larvae showed a significant decrease in relative expression (RE) of GABABR1 (65%, p < 0.01) and GABABR3 (44%, p < 0.001) compared to untreated controls. Compared to antibiotic-treated larvae, probiotic-treated larvae show significantly decreased RE of GABAAR (27%, p < 0.001) and GAD1 (44%, p < 0.001), and a further significant and incremental decrease in GABABR1 compared to antibiotic-treatment (55%, p < 0.001) and untreated control (36%, p < 0.001). Probiotic-treated larvae showed significant decreases in GABAAR (29%, p < 0.001), GABABR1 (35%, p < 0.001), GABABR3 (25%, p < 0.01), and GAD1 (47%, p < 0.001) expression compared to untreated controls. No significant changes in expression levels of GABABR2 and Insulin receptor (Ins-R) genes were observed among treatments (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Microbiota load impacts expression levels of GABA signaling components measured using qRT-PCR analysis.

Drosophila larvae grown on normal untreated food (black bars), antibiotic-treated food (white bars), and larvae grown on probiotic food from antibiotic-treated parents (grey bars) are shown. Bars represent average fold change in expression (relative to three neuronal genes) ± SEM. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Discussion

The specific conclusions of this study are that the microbiota load influences host olfactory behavior as well as the levels of host GABA signaling components. To undertake this study, first, we successfully optimized protocols to generate Drosophila larval strains that had different microbiota loads (Figs. 1 and 2). Next, we tested the behavior responses of the larval strains to test odorants in a simple two-choice olfactory assay. Larval strains with different microbiota loads responded differently to the odorants (Fig. 3). We noted that for two of the three odorants tested, reducing the microbiota load significantly reduced attractiveness toward the odorants while partially replenishing the microbiota load with probiotics partially rescued this behavior response (Fig. 3). Finally, RNA-expression analyses in the individual larval strains revealed that expression levels of specific GABA-receptor subunits and GAD1, an enzyme involved in GABA production, are sensitive to microbiota load (Fig. 4).

The expression of GABA-receptor subunits: GABABR1 and GABABR3 were lower in antibiotic treated larvae compared to untreated larvae. GABAAR, GABABR1, and GAD1 expression were lower in probiotic treated larvae compared to antibiotic-treated larvae. The sensitivity of GABA related gene expression to microbiota load suggests that there are homeostatic mechanisms that alter GABA production and GABA-receptor expression based on interactions with gut microbiota. Throughout all experimental conditions, GABABR2 levels remained unchanged. This result is consistent with the relative importance of individual GABAB-receptor subunits reported in previous studies. Sleep deprivation in mice led to changes in GABABR1 but not GABABR2 levels in the mouse hippocampus (Tadavarty et al., 2011). Out of the three subunits of the heteromeric GABAB-receptor, the role of GABABR1 is to bind agonists while the role of GABABR2 is to mediate coupling to G-proteins and facilitate downstream signal transduction (Nomura et al., 2008). Together, our study along with previous studies suggests that GABABR1 levels are likely the target of physiological-state dependent modulation.

This study is consistent with several studies that have explored the symbiotic relationship between an organism and its microbiota. An organism’s microbiome contributes to homeostasis, or conversely to disease states. With capabilities of modulating host gene expression, an unbalanced microbiome has the potential to dramatically affect the host organism (Lutay et al., 2013). Bacteria possess genes that are conserved among other species including humans and insects. Several gut bacterial strains are known to produce neurotransmitters like dopamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, noradrenaline and GABA (Clarke et al., 2014). Several Lactobacillus strains including L. brevis are robust producers of GABA via GAD expression (Barrett et al., 2012; Li and Cao, 2010). It has been suggested that the high levels of microbiota-produced neurotransmitters may be an important intermediate for communication between bacteria and neurons (Yang and Chiu, 2017). Thus, one possible explanation of the observations in this study is that larval-gut microbiota produce GABA, which impacts homeostatic production of GABA by the local neurons that regulate ORNs, and/or expression of GABA receptors on the ORN terminals. Any disruption in this homeostasis could affect information processing in the larval olfactory circuit, which, in turn, could impact behavioral responses of host larvae to odorants. In support of this explanation, presynaptic inhibition of ORN terminals mediated by GABA signaling has been implicated in modulating the neural representations of different odors in both insects and mammals (McGann et al., 2005; Vucinic et al., 2006; Wilson and Laurent, 2005).

This study also sheds light on the differential modulation of individual ORNs. The three odorants used in this study were specifically chosen because they not only elicited attractive behavior responses from larvae but also elicited strong specific physiological responses from single or few ORNs (Kreher et al., 2008; Mathew et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that individual ORNs contribute differently to the olfactory circuit and have raised the possibility that there is functional individuality among the repertoire of ORNs (Mathew et al., 2013; Newquist et al., 2016). While the molecular basis for this individuality is not clear, one implication of these studies is that individual ORNs are differentially modulated by the animal’s physiological state. Here, we observe that reducing microbiota load significantly impacted host-larval behavior driven by the ORNs sensing ethyl acetate and pentyl acetate, while it did not significantly impact host-larval behavior driven by the ORN sensing 4-hexen-3-one (Fig. 3). This suggests that reducing the microbiota load differentially impacted individual ORNs, consistent with recent theories about ORN individuality.

The present study possesses several limitations of note: 1) while the use of antibiotics drastically reduced or eliminated antibiotic-sensitive bacteria from the larvae, this study does not rule out the presence of other microorganisms including yeast and fungi that are insensitive to antibiotics. Thus, this study cannot claim the experimental strain to be ‘axenic’; 2) the reception of odor molecules by sensory neurons followed by the processing of olfactory information into a behavioral response is a complicated process. While GABA signaling has previously been implicated in modulating this process (Ko et al., 2015; McGann et al., 2005; Root et al., 2008; Vucinic et al., 2006; Wilson and Laurent, 2005), our experiments do not rule out the role of other factors secreted by larval microbiota that could impact olfactory circuit function; 3) while qRT-PCR experiments performed on RNA isolated from larval heads showed significant changes in GABA signaling components, the localization of these changes to olfactory neurons were not performed. A more precise localization of the effects of microbiota on specific olfactory neurons would require isolation of RNA from single neurons (Ma and Weake, 2014). Immunocytochemistry experiments using antibodies targeted to GABA or specific GABA receptors could also help localize the effects of microbiota on specific olfactory neurons; and 4) while a homeostatic regulation of GABA signaling components by larval microbiota is a likely explanation for the effects seen in this study, further experiments would be required to confirm this hypothesis and determine a precise mechanism for this regulation. For instance, does the GABA released by gut microbiota directly impact olfactory neurons? Or, are there sensory afferents that detect GABA in the gut, which, in turn, trigger the CNS to modulate olfactory function?

The ability of olfactory neurons to detect food odors underlies survival in most species of the animal kingdom. This ability of olfactory neurons to process environmental information is modulated by several internal and external factors. Overall, this study suggests that microbiota load is one of the internal factors that impacts host olfactory neuron function and that this occurs via modulating levels of GABA signaling components. Analysis of the impact of host microbiota on the function of a simple, tractable olfactory circuit of the Drosophila larva has implications for elucidating the mechanisms by which different internal factors modulate neural function. In order to build effective computational models of odor coding, it is essential to consider, in addition to the activity of individual circuit neurons, the modulation of individual neurons by homeostatic mechanisms that are influenced by various factors such as host microbiota load and physiological state.

Acknowledgments:

Research reported in this publication was supported by TriBeta under-graduate research awards to CL and KMH, and by startup Funds from the University of Nevada, Reno and by NIGMS of the National Institute of Health under grant number P20 GM103650 to DM.

References

- Aziz Q, and Thompson DG (1998). Brain-gut axis in health and disease. Gastroenterology 114, 559–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E, Ross RP, O’Toole PW, Fitzgerald GF, and Stanton C (2012). Gamma-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J Appl Microbiol 113, 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P, Collins SM, and Verdu EF (2012). Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroent Motil 24, 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummel T, Ching A, Seroude L, Simon AF, and Benzer S (2004). Drosophila lifespan enhancement by exogenous bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 12974–12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, and Dinan TG (2014). Minireview: Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol 28, 1221–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, and Dinan TG (2012). Mind-altering micro-organisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 13, 701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkosar B, Storelli G, Defaye A, and Leulier F (2013). Host-intestinal microbiota mutualism: “Learning on the fly”. Cell Host Microbe 13, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JB, Chen HH, Sattelle E, Barker PJ, Huskisson NS, Rauh JJ, Bai D, and Sattelle DB (1996). Immunocytochemical mapping of a C-terminus anti-peptide antibody to the GABA receptor subunit, RDL in the nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res 284, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Choii G, and Um JW (2015). The balancing act of GABAergic synapse organizers. Trends Mol Med 21, 256–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konturek SJ, Konturek JW, Pawlik T, and Brzozowki T (2004). Brain-gut axis and its role in the control of food intake. J Physiol Pharmacol 55, 137–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreher SA, Mathew D, Kim J, and Carlson JR (2008). Translation of sensory input into behavioral output via an olfactory system. Neuron 59, 110–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HX, and Cao YS (2010). Lactic acid bacterial cell factories for gamma-aminobutyric acid. Amino Acids 39, 1107–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutay N, Ambite I, Hernandez JG, Rydstrom G, Ragnarsdottir B, Puthia M, Nadeem A, Zhang JY, Storm P, Dobrindt U, et al. (2013). Bacterial control of host gene expression through RNA polymerase II. J Clin Invest 123, 2366–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JQ, and Weake VM (2014). Affinity-based isolation of tagged nuclei from Drosophila tissues for gene expression analysis. Jove-J Vis Exp 85, 51418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew D, Martelli C, Kelley-Swift E, Brusalis C, Gershow M, Samuel AD, Emonet T, and Carlson JR (2013). Functional diversity among sensory receptors in a Drosophila olfactory circuit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, E2134–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA (2011). Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 12, 453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGann JP, Pirez N, Gainey MA, Muratore C, Elias AS, and Wachowiak M (2005). Odorant representations are modulated by intra- but not interglomerular presynaptic inhibition of olfactory sensory neurons. Neuron 48, 1039–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte P, Woodard C, Ayer R, Lilly M, Sun H, and Carlson J (1989). Characterization of the larval olfactory response in Drosophila and its genetic basis. Behav Genet 19, 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newquist G, Novenschi A, Kohler D, and Mathew D (2016). Differential contributions of olfactory receptor neurons in a Drosophila olfactory circuit. Eneuro 3 e0045–16, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Roorda RD, Lima SQ, Zemelman BV, Morcillo P, and Miesenbock G (2002). Transmission of olfactory information between three populations of neurons in the antennal lobe of the fly. Neuron 36, 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura R, Suzuki Y, Kakizuka A, and Jingami H (2008). Direct detection of the interaction between recombinant soluble extracellular regions in the heterodimeric metabotropic gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283, 4665–4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EMM, Cryan JF, and Dinan TG (2009). Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiat 65, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, and Mayer EA (2009). Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 6, 306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley EV, Wong ACN, Westmiller S, and Douglas AE (2012). Impact of the resident microbiota on the nutritional phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster. PloS one 7, e36765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues V, and Siddiqi O (1978). Genetic-analysis of chemosensory pathway. Proc Indian Acad Sci [B] 87, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Root CM, Masuyama K, Green DS, Enell LE, Nassel DR, Lee CH, and Wang JW (2008). A presynaptic gain control mechanism fine-tunes olfactory behavior. Neuron 59, 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson TR, and Mazmanian SK (2015). Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 17, 565–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sender R, Fuchs S, and Milo R (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS biology 14, e1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon G, Segal D, Ringo JM, Hefetz A, Zilber-Rosenberg I, and Rosenberg E (2010). Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 20051–20056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, Kim B, Kim AC, Lee KA, Yoon JH, Ryu JH, and Lee WJ (2011). Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science 334, 670–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadavarty R, Rajput PS, Wong JM, Kumar U, and Sastry BR (2011). Sleep-deprivation induces changes in GABA(B) and mGlu receptor expression and has consequences for synaptic long-term depression. PloS one 6, e24933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucinic D, Cohen LB, and Kosmidis EK (2006). Interglomerular center-surround inhibition shapes odor-ant-evoked input to the mouse olfactory bulb in vivo. Journal of Neurophysiology 95, 1881–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW (2012). Presynaptic modulation of early olfactory processing in Drosophila. Developmental Neurobiology 72, 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Maemura K, Kanbara K, Tamayama T, and Hayasaki H (2002). GABA and GABA receptors in the central nervous system and other organs. International Review of Cytology - a Survey of Cell Biology 213, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, and Laurent G (2005). Role of GABAergic inhibition in shaping odor-evoked spatiotemporal patterns in the Drosophila antennal lobe. The Journal of Neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 25, 9069–9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CNA, Ng P, and Douglas AE (2011). Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol 13, 1889–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang NJ, and Chiu IM (2017). Bacterial signaling to the nervous system through toxins and metabolites. Journal of Molecular Biology 429, 587–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunes RA, Poluektova EU, Dyachkova MS, Klimina KM, Kovtun AS, Averina OV, Orlova VS, and Danilenko VN (2016). GABA production and structure of gadB/gadC genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains from human microbiota. Anaerobe 42, 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]