Abstract

Unilateral incompatibility (UI) manifests as pollen rejection in the pistil, typically when self-incompatible (SI) species are pollinated by self-compatible (SC) relatives. In the Solanaceae, UI occurs when pollen lack resistance to stylar S-RNases, but other, S-RNase-independent mechanisms exist. Pistils of the wild tomato Solanum pennellii LA0716 (SC) lack S-RNase yet reject cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, SC) pollen. In this cross, UI results from low pollen expression of a farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene (FPS2) in S. lycopersicum. Using pollen from fps2−/− loss-of-function mutants in S. pennellii, we identified a pistil factor locus, ui3.1, required for FPS2-based pollen rejection. We mapped ui3.1 to an interval containing 108 genes situated on the IL 3-3 introgression. This region includes a cluster of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC2) genes, with four copies in S. pennellii, versus one in S. lycopersicum. Expression of ODC2 transcript was 1,034-fold higher in S. pennellii than in S. lycopersicum styles. Pistils of odc2−/− knockout mutants in IL 3-3 or S. pennellii fail to reject fps2 pollen and abolish transmission ratio distortion (TRD) associated with FPS2. Pollen of S. lycopersicum express low levels of FPS2 and are compatible on IL 3-3 pistils, but incompatible on IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids, which express both ODC2 and ui12.1, a locus thought to encode the SI proteins HT-A and HT-B. TRD observed in F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 points to additional ODC2-interacting pollen factors on both chromosomes. Thus, ODC2 genes contribute to S-RNase independent UI and interact genetically with ui12.1 to strengthen pollen rejection.

Ornithine decarboxylase genes expressed in pistils underly a major unilateral incompatibility locus required for S-RNase-independent pollen selection/rejection in the wild tomato Solanum pennellii.

Introduction

Various pre- and postfertilization reproductive barriers restrict hybridization between related species or populations. One barrier, unilateral incompatibility (UI), manifests as an arrest of pollen tube growth within the style, and is unidirectional, i.e. pollen of species A are rejected by pistils of species B, but not vice versa. The occurrence of UI is often associated with the evolutionary breakdown of self-incompatibility (SI), a correlation known as the “SI × SC” rule because pollen of self-compatible (SC) species or populations are typically incompatible on pistils of related SI species or populations (e.g. Baek et al., 2015). Exceptions to the SI × SC rule include forms of pollen rejection that are independent of SI.

The mechanisms of pollen rejection by UI are complex and overlap with SI (Bedinger et al., 2017). In the Solanaceae, SI is the gametophytic S-RNase-based mechanism, wherein a polymorphic S-locus encodes highly variable pistil S-RNases and multiple S-locus F-box proteins (SLFs) expressed in pollen (Fujii et al., 2016). The SLFs are components of SCFSLF E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes that target specific S-RNase proteins for ubiquitylation, leading to their degradation in the proteasome. Each S-haplotype encodes an array of ca. 20 SLF genes (Kubo et al., 2010, 2015; Williams et al., 2014; Li and Chetelat, 2015). Under the collaborative non-self recognition model (Kubo et al., 2010, 2015), the cluster of SLF genes comprising a given S-haplotype collectively recognizes all S-RNases except the S-RNase encoded by that haplotype. Thus, pollen are normally resistant to all non-self S-RNases (compatibility) but not to self-S-RNase (incompatibility). While the S-RNase and SLF genes are the genetic determinants of SI specificity, additional modifier genes (MGs) are required for SI functionality. Known pistil-side MGs include those encoding the cysteine-rich HT proteins, a thioredoxin reductase (NaTrxh), a proteinase inhibitor (NaStEP), and a 120-KDa protein (McClure et al., 1999; Hancock et al., 2005; Jimenez-Duran et al., 2013; Torres-Rodriguez et al., 2020). Pollen-side MGs include genes encoding the Skp1 and Cullin1 proteins, which are essential components of the SCFSLF complex (Li and Chetelat, 2010; Zhao et al., 2010), and a mitochondrial phosphate carrier protein, NaSIPP (Garcia-Valencia et al., 2017). Cultivated tomato, Solanum lycopersicum, is SC and lacks several essential SI factors. Its pollen lack functional Cullin1 protein, and as a result are rejected by UI on pistils of all related SI species that express any functional S-RNase (Li and Chetelat, 2010). Cultivated tomato also lacks several pistil-side SI factors, including the S-RNase and HT proteins (Kondo et al., 2002; Covey et al., 2010). Transgenic expression of both S-RNase and HT proteins in tomato pistils confers the ability to reject S. lycopersicum pollen via UI (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017).

In addition to the S-RNase-based form of UI described above, there are other mechanisms of pollen rejection in Solanum that act either in concert with or independently of S-RNase and SI (Bedinger et al., 2017). On the pistil-side, three major QTLs controlling the strength of pollen rejection have been mapped in BC or F2 progeny of S. lycopersicum × S. habrochaites (Bernacchi and Tanksley, 1997) and S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (Hamlin et al., 2017; Jewell et al., 2020). One of these loci, ui1.1, maps to the S-locus on chromosome 1 and presumably encodes the S-RNase (Jewell et al., 2020). The other two pistil-side QTLs are ui3.1 on chromosome 3 and ui12.1 on chromosome 12. The ui12.1 QTL maps near a pair of HT coding genes, HT-A and -B (Covey et al., 2010; Jewell, 2016), which contribute to both S-RNase dependent and independent UI (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017). The ui3.1 gene, as yet unidentified, interacts genetically with ui12.1 (HT-A/-B) to strengthen UI pollen rejection (Hamlin et al., 2017). As single loci, ui3.1 or ui12.1 are insufficient for pistils to reject S. lycopersicum pollen, however combining both QTLs from S. pennellii in S. lycopersicum establishes a pistil barrier that rejects tomato pollen (Hamlin et al., 2017).

Major pollen-side UI factor loci have been mapped to chromosomes 1, 6, and 10 (Chetelat and DeVerna, 1991). The loci on chromosomes 1 and 6, ui1.1 and ui6.1, encode a suite of SLFs and a Cullin1 protein, respectively, that act in S-RNase-dependent UI (Li and Chetelat, 2010, 2015). The chromosome 10 factor is a farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene (FPS2) expressed in pollen that functions in S-RNase independent UI (Qin et al., 2018). Pistils of S. pennellii, including accessions that lack S-RNase, reject pollen of S. lycopersicum by UI. We showed that compatibility on pistils of S. pennellii requires high level expression of FPS2 in pollen (Qin et al., 2018). CRISPR-generated knock out mutants (fps2−/−) in S. pennellii reject their own pollen via UI. Cultivated tomato pollen expresses 18-fold lower levels of FPS2 transcript than S. pennellii pollen. F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii populations show strong transmission ratio distortion (TRD) at the FPS2 locus, with an excess of FPS2P/P and FPS2L/P genotypes, resulting from the selective elimination of pollen bearing the FPS2L allele (Qin et al., 2018). FPS2-linked TRD occurs in crosses with either SC accessions of S. pennellii that do not express S-RNase (Qin et al., 2018), or with SI accessions that do (Trujillo-Moya et al., 2011). Therefore, the FPS2-based pollen rejection mechanism is independent of S-RNase expression. F2 populations made with the fps2 mutant of S. pennellii show strong TRD in the opposite direction, i.e. an excess of FPS2L alleles, due to selective elimination of fps2− knockout pollen. Pistils of S. pennellii and its F1 hybrid with S. lycopersicum are thus FPS2 selective. In contrast, pistils of S. lycopersicum are FPS2 nonselective, i.e. equally compatible with pollen bearing the FPS2L hypomorph allele, the high expressing FPS2P allele, or the fps2 knockout allele (Qin et al., 2018).

The biochemical basis for FPS2-based pollen rejection is not understood. FPS enzymes catalyze the synthesis of farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), a key building block in isoprenoid biosynthesis and an intermediate in several biochemical pathways. FPP is also required for protein farnesylation, a posttranslational modification used to target proteins to the cell membrane.

The objective of the present research was to isolate the pistil-side UI gene responsible for FPS2-based pollen selectivity. We show that a single locus, ui3.1, is required and sufficient for elimination of fps2 mutant pollen. A cluster of closely related ornithine decarboxylase coding genes (ODC2s) underlie the ui3.1 locus and FPS2 selectivity. The S. pennellii genome contains four ODC2 genes and expresses much higher transcript levels in pistils than S. lycopersicum, which contains a single gene. Pistils expressing wild-type S. pennellii ODC2 genes reject fps2 pollen, whereas odc2 knockout mutants fail to do so. These results suggest that polyamines (PAs)—the product of ODC activity—synthesized in the pistil contribute to S-RNase independent pollen rejection. We also show that ODC2 genes interact genetically with ui12.1, a UI locus thought to encode the SI proteins HT-A and HT-B, to strengthen pollen rejection, suggesting the ODC2-dependent pollen rejection mechanism may overlap with SI.

Results

A pistil-side UI locus on chromosome 3 is required for FPS2-based pollen rejection

To understand the biochemical basis for FPS2-based pollen rejection, we sought to identify the corresponding pistil factor(s) that establish FPS2 selectivity. We hypothesized that the pistil factor(s) would correspond to one of several UI loci that contribute to pollen rejection in tomato interspecific hybrids, i.e. ui1.1, ui3.1, or ui12.1. Of these, ui1.1 maps to the S-locus and likely encodes an S-RNase (Jewell et al., 2020). Since FPS2-based pollen rejection does not require S-RNase (Qin et al., 2018), we ruled out ui1.1. The ui12.1 locus maps near two genes encoding HT proteins, which function in both S-RNase dependent and S-RNase independent pollen rejection (Covey et al., 2010; Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017). The ui3.1 locus maps to chromosome 3, but the underlying gene was unknown.

To evaluate the possible role of ui3.1 and ui12.1 in FPS2-based pollen rejection, we used the S. pennellii introgression lines IL 3-3 and IL 12-3, containing the ui3.1 and ui12.1 loci, respectively. Both IL 3-3 and IL 12-3 accept pollen of S. lycopersicum cv M-82 and S. pennellii LA0716 pollen. IL 12-3 accepts pollen of fps2−/− mutants in S. pennellii, while IL 3-3 rejects fps2 pollen (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). This result indicates that one or more S. pennellii gene(s) on the IL 3-3 introgression establish a pistil barrier that blocks pollen lacking high level FPS2 expression.

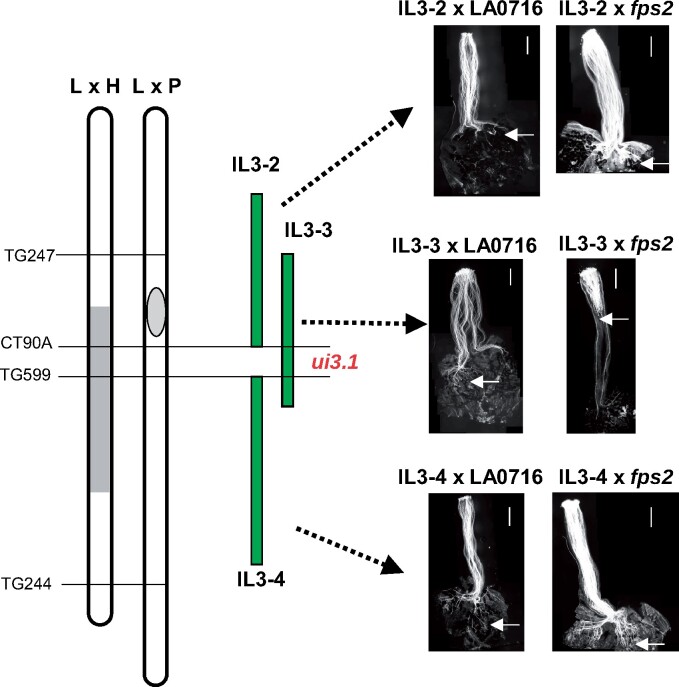

Figure 1.

Genetic map of chromosome 3 introgression lines and pollen tube growth of WT and fps2 mutant LA0716 pollen on pistils of IL 3-2, IL 3-3, and IL 3-4. Only pistils of IL 3-3 reject fps2 pollen, which places the ui3.1 locus in the genomic region unique to the IL 3-3 introgression. A genetic map based on S. lycopersicum × S. habrochaites (“L × H” map) shows the approximate location (gray rectangle) of the ui3.1 locus reported by Bernacchi and Tanksley (1997). A genetic map from F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (“L × P”) shows the approximate positions of each introgressed segment based on the EXPEN 2000 genetic map (https://solgenomics.net). Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tube. Scale bar: 1 mm.

To evaluate whether the rejection of fps2 mutant pollen by IL 3-3 is a dominant or recessive trait, heterozygous IL 3-3 plants were generated by crossing M-82 pollen onto IL 3-3 homozygotes. Mutant fps2 pollen is also rejected by heterozygous IL 3-3 plants, while wild-type FPS2 pollen is compatible (Supplemental Figure S1), indicating that pollen rejection is at least partially dominant in the pistil. This result is consistent with the rejection of fps2 pollen by pistils of the interspecific hybrid, F1 S. lycopersicum cv VF36 × S. pennellii LA0716 (Qin et al., 2018). Expression of the ui3.1 phenotype in heterozygotes suggests the gene encodes an active pistil barrier factor(s).

To more precisely map the ui3.1 locus we pollinated introgression lines IL 3-2 and IL 3-4, which overlap IL 3-3, with fps2 mutant pollen (Figure 1). Unlike IL 3-3, both IL 3-2 and IL 3-4 accept fps2 pollen (Figure 1). Therefore, ui3.1 must be located in the region unique to IL 3-3, which corresponds to the interval between markers CT90A and TG599, a distance of about 8.5 cM on the EXPEN 2000 genetic map (Alseekh et al., 2013). This places ui3.1 at position 65.38–66.42 Mbp on the physical map of chromosome 3 in S. pennellii, or 54.79–56.58 Mbp in the S. lycopersicum (SL4.0) genome (Bolger et al., 2014; https://solgenomics.net). This position is consistent with and more precise than previous estimates for the location of ui3.1 (Bernacchi and Tanksley, 1997; Jewell, 2016; Song et al., 2016).

Candidate genes in the ui3.1 region

Chitwood et al. (2013) genotyped the S. pennellii IL library by low pass reduced representation sequencing (RESCAN). This analysis presented IL 3-3 as comprised of two introgressions: a short segment located at the top of the short arm and a longer segment covering most of the middle part of the chromosome. (However, Alseekh et al. (2013) report a single introgression in IL 3-3.) There are 108 annotated genes between markers CT90A and TG599 in the S. pennellii and S. lycopersicum genome (Supplemental Table S1). These genes were evaluated for a possible role in pistil-side UI based on their annotations (Chitwood et al., 2013; https://solgenomics.net). To our knowledge, none have been linked to SI or UI. We predicted that the ui3.1 gene would be expressed in pistils, and would likely be more abundant in S. pennellii than in S. lycopersicum pistils. Four genes were on the list of the top 1,000 differentially expressed genes when comparing pistils of S. pennellii and S. lycopersicum (Jewell, 2016; Pease et al., 2016): Solyc03g098300 (ornithine decarboxylase-like protein, ODC-like protein, herein ODC2), Solyc03g098310 (ODC-like protein, herein ODC3), Solyc03g098480 (chromosome alignment-maintaining phosphoprotein 1-like isoform X2), and Solyc03g098490 (DUF761 domain-containing protein).

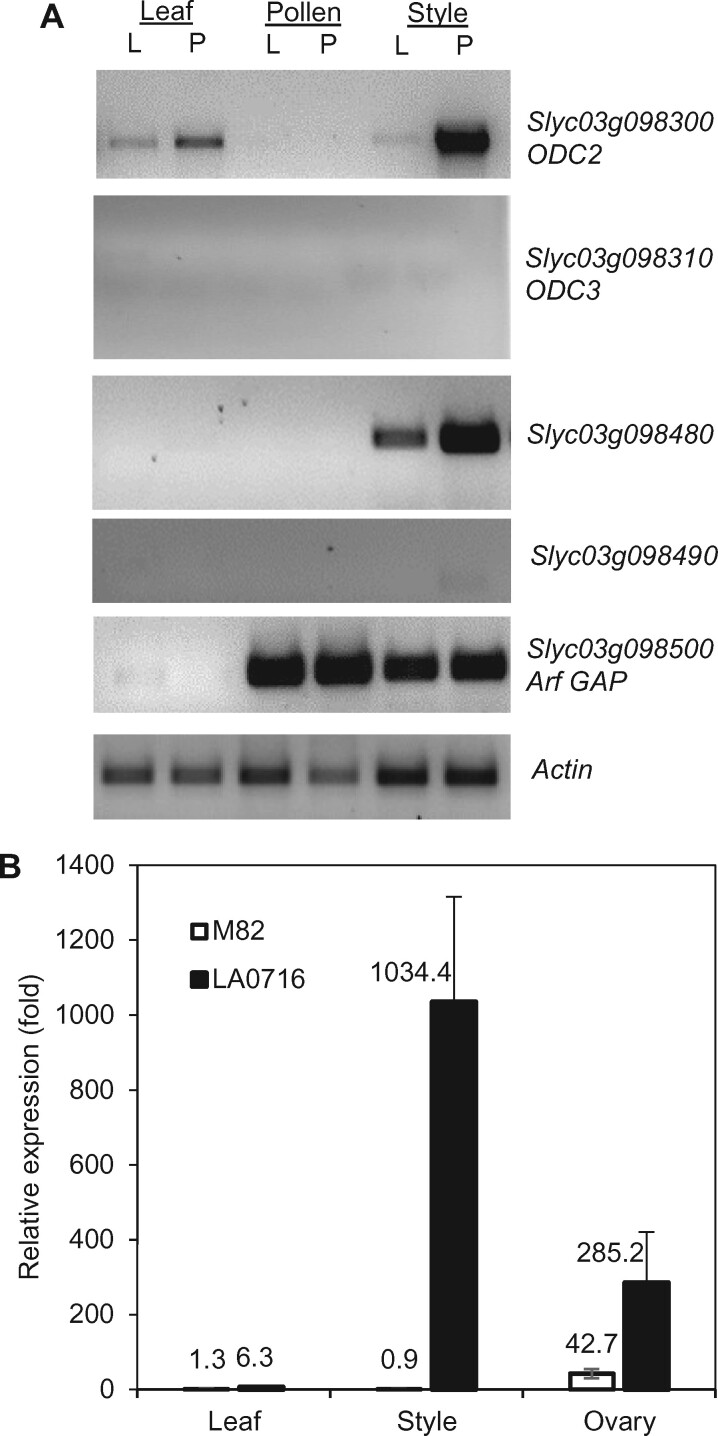

RT-PCR was used to evaluate the differential expression of these four genes in leaf, pollen, and pistil tissues of S. lycopersicum cv VF36 and S. pennellii LA0716 (Figure 2, A). In addition, we selected several genes indicative of regulatory functions to assess their expression patterns. We confirmed that Solyc03g098300 (ODC2) is expressed in pistils, with higher expression noted in LA0716 than in VF36, and very low levels in leaves or pollen. Solyc03g098310 (ODC3) and Solyc03g098490 were not expressed in any tissues examined. Solyc03g098480 also showed pistil-specific expression and was more abundant in LA0716 pistils than in VF36 pistils (Figure 2, A). Of the other genes analyzed, four were expressed in both pollen and pistils (Solyc03g098400, Solyc03g098450, Solyc03g098500, and Solyc03g098590), and two were expressed in pistils only (Solyc03g098320 and Solyc03g098640). However, no significant difference in expression levels was observed between VF36 and LA0716 (Supplemental Figure S2). Sequence comparisons of these genes in S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii revealed the Solyc03g098500 (Arf-GAP) gene has an amino acid difference that could be functionally significant: the amino acid at position 114 is arginine in S. pennellii versus glutamine in S. lycopersicum.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of ui3.1 candidate gene expression. A, Qualitative RT-PCR analysis of transcript abundance in leaves, pollen, and styles of S. lycopersicum (L) and S. pennellii (P). B, RT-qPCR analysis of ODC2 mRNA levels in S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii leaves, styles, and ovaries. Data are presented as the mean ± se (n = 3).

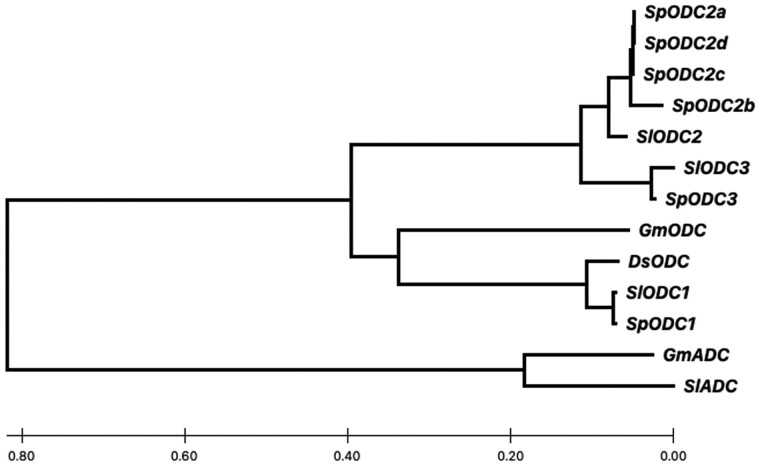

This region of the S. lycopersicum genome was compared with the corresponding region of the S. pennellii genome (Supplemental Table S1) to see whether there are major insertion or deletion events that result in a gain or loss of genes. We noted significant copy number variation for ODC genes. Two tandem gene copies are present in the S. lycopersicum genome: Solyc03g098300 and Solyc03g098310, herein referred to as ODC2 and ODC3 to distinguish them from a previously described (Alabadi and Carbonell, 1998) ODC gene on chromosome 4, Solyc04g082030, herein referred to as ODC1. In contrast, the S. pennellii genome has six tandem ODC genes on chromosome 3: Sopen03g029010, Sopen03g029020, Sopen03g029030, Sopen03g029040, Sopen03g029050, and Sopen03g029060 (https://solgenomics.net). Sopen03g029010 is a partial sequence and most likely nonfunctional. Protein sequence alignment of the other five ODC gene products indicates Sopen03g029060 is closely related to Solyc03g098310 (ODC3; Figure 3). The four remaining S. pennellii ODCs are grouped together with Solyc03g098300 (ODC2); they share 96.17%–100.00% amino acid identity and likely represent multiple ODC2 paralogs. We herein refer to these four genes, Sopen03g029020, Sopen03g029030, Sopen03g029040, and Sopen03g029050, as SpODC2a, SpODC2b, SpODC2c, and SpODC2d, respectively (Figure 3). SpODC2a, SpODC2c, and SpODC2d are nearly identical, while SpODC2b has a 22-bp deletion at the 3′-end of the gene that results in a frame shift at amino acid 381 and a longer translated protein with 10 additional amino acids (402 aa versus 392 aa). We used RT-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to compare the total ODC2 transcript levels in styles and ovary tissues of S. pennellii and S. lycopersicum (Figure 2, B). We observed an average of 1,034-fold higher expression in S. pennellii styles compared with S. lycopersicum styles. A lower level of ODC2 transcript was expressed in the ovaries of both species. However, the most substantial difference was in the styles of S. pennellii versus S. lycopersicum.

Figure 3.

Neighbor-joining tree of ornithine decarboxylases and related protein sequences. The predicted amino acid sequences are from SpODC2a (Sopen03g029020), SpODC2b (Sopen03g029030), SpODC2c (Sopen03g029040), SpODC2d (Sopen03g029050), SlODC2 (Solyc03g098300), SlODC3 (Solyc03g098310), SpODC3 (Sopen03g029060), GmODC (NP_001238629.1), DsODC (X87847), SlODC1 (Solyc04g082030), SpODC1 (Sopen04g035680), GmADC (AAD09204.1), and SlADC (NP_001234649.2). Sp = S. pennellii, Sl = S. lycopersicum, Ds = Datura stramonium, Gm = Glycine max. ADC, arginine decarboxylase; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase. The scale indicates the average number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Notably absent from the ui3.1 interval were any homologs of genes known to function in SI or UI. We therefore selected four genes for CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis to evaluate their function in rejection of fps2 mutant pollen. Solyc03g098300 (ODC2) and Solyc03g098480 were chosen based on their high levels of expression in S. pennellii pistils. Solyc03g098500 (Arf-GAP) was selected because of its high expression in pistils and the presence of an amino acid substitution between the parents. Solyc03g098310 (ODC3) was chosen because it also encodes an ODC protein and was reportedly upregulated in UI competent tissues (Pease et al., 2016).

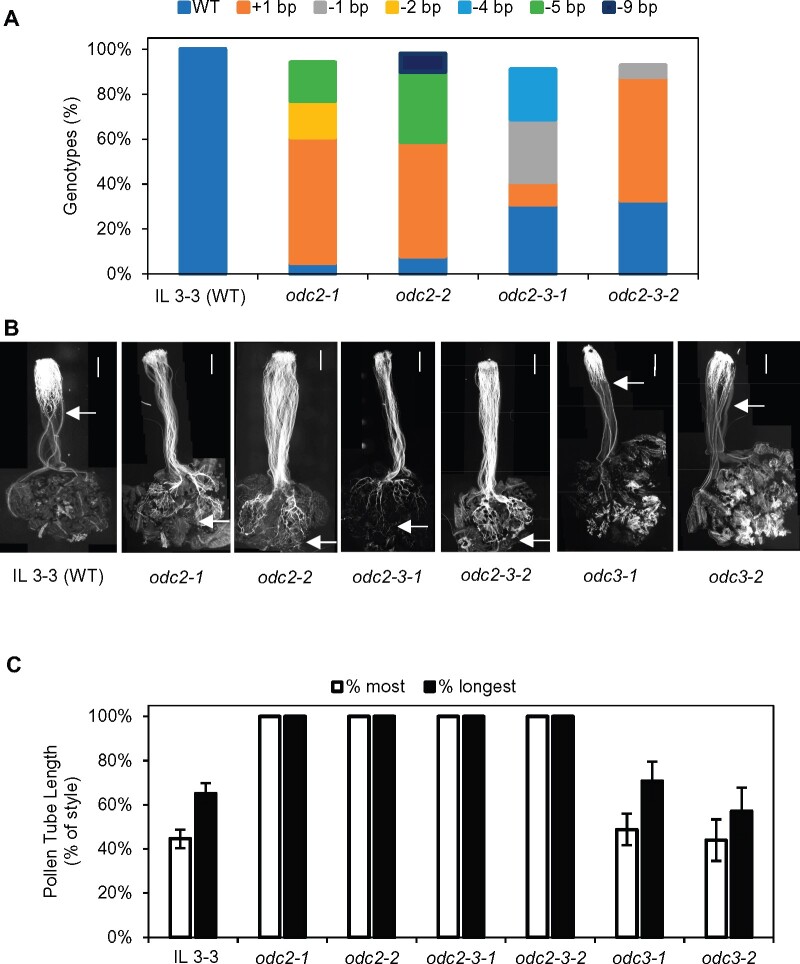

odc2 loss of function mutants accept fps2 mutant pollen

Each CRISPR-Cas9 construct was introduced into IL 3-3 and S. pennellii LA0716 by Agrobacterium transformation. Multiple independent T0 transgenic lines were obtained for each target gene. A preliminary phenotypic evaluation was conducted on putative mutants identified in the IL 3-3 T0 transgenic lines. Because CRISPR-Cas9 often introduces small insertions or deletions near the PAM site (Fauser et al., 2014), we designed gRNAs that have restriction enzyme sites for three of the targeted genes, so mutants can be easily identified by CAPS markers. Small insertions or deletions would eliminate the restriction sites, resulting in a larger, uncut PCR product. Complete absence of the wild-type band in the odc3 and arf-gap transgenic lines indicated those plants were null mutants. Both mutant and WT alleles were present in the three odc2 transgenic lines (Supplemental Figure S3, A). Analysis of the mutations in those lines is complicated by the presence of four ODC2 genes in the S. pennellii locus. Thus, the CRISPR-Cas9 construct could induce mutations in zero, one, two, three, or four genes, potentially leading to quantitative effects on ODC2 expression and pollen rejection. Assessment of Slyc03g098480 mutations was based on sequencing PCR products because no suitable restriction site was found for gRNA design. Pollination tests revealed that only the odc2 mutant lines accepted fps2 mutant pollen. Knockout lines of the other three genes in IL3-3 rejected fps2 pollen (Supplemental Figure S3, B). Three independent T0 odc2 transgenic lines were advanced to the T1 and T2 generations to sequence their specific mutations and further evaluate their compatibility with fps2 mutant pollen. Because the four ODC2 genes (i.e., eight gene copies) are nearly identical at the DNA sequence level, we used a combination of CAPS markers, TIDE analysis (Brinkman et al., 2014), and sequencing individual clones from ODC2 PCR products to determine the mutations in each transgenic line. The mutant alleles in the three T0 plants odc2-1, odc2-2, and odc2-3 were 28%, 53%, and 49% of total, according to TIDE analysis. The frequency of T-DNA transmission to the T1 generation for the three lines was 75:5, 48:0, and 74:6, respectively, suggesting multiple independent insertions of the CRISPR-Cas9 construct in each plant. Different levels of mutation were achieved in the T2 lines. The highest mutation rates were seen in T2 progeny of odc2-1 and odc2-2, both of which retained the CRISPR-Cas9 T-DNA insertions, hence were subject to continued mutation. CAPS marker analysis showed no visible wild-type band. TIDE analysis indicated very low levels of wild type (8% and 5%) remaining, suggesting that most of the ODC2 gene copies were mutated in these two lines. Two T-DNA-free T2 progeny of odc2-3 had intermediate levels of mutant alleles, they retained 31% and 33% of wild-type ODC2 genotype and they segregated into two different patterns of mutations. All of the insertion and deletion mutations were confirmed by sequencing cloned PCR products. Most of the mutations result in truncated proteins with stop codons around aa 39–43 (Table 1), which are presumably non-functional. Pollination tests showed all four odc2 knockout lines accept fps2 mutant pollen. Pollen tubes reached the ovaries and penetrated ovules (Figure 4), resulting in fruit and seed set (Table 1). In contrast, no fruit or seeds were produced from 33 crosses of fps2 mutant pollen onto wild-type IL 3-3. Consistent with the results from T0 plants, T1 generation of odc3 mutants odc3-1 (−4/−4 bp) and odc3-2 (+1/+1 bp) rejected fps2 pollen. These results demonstrate that complete or partial loss of ODC2 function abolishes the pistil rejection of fps2 mutant pollen. We conclude that ODC2 genes are functionally responsible for the ui3.1 phenotype.

Table 1.

Mutations in ODC2 knockout lines and compatibility phenotypes after pollination with pollen from fps2 mutant S. pennellii

| Crosses with fps2− pollen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Generation | TIDE analysisa | Cloned sequencesb | Predicted change in protein sequencec | Pollen tubes | Seed and fruit set | |

|

IL 3-3 | |||||||

| WT | – | WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG | Rejected | 0 seeds, 0 ft from 33 crosses | |||

| odc2-1 | T2 |

WT: 5% +1: 56% −2: 16% −5: 17% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGWTACTGG −2 GGCAACCATTTTA- - -TACTGG −5 GGCAACCATT- - - - - -TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Tfs *42 Y35Tfs *41 |

Accepted | 21 seeds/ft | |

| odc2-2 | T2 |

WT: 8% +1: 51% −5: 31% −9: 8% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGWTACTGG −5 GGCAACCATT- - - - - -TACTGG −9 GGCAAC- - - - - - - - - -TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 Y35Tfs *41 P33-Y35del |

Accepted | 34 seeds/ft | |

| odc2-3 |

T2 odc2-3-1 |

WT: 31% +1: 10% −1: 28% −4: 22% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGWTACTGG −1 GGCAACCATTTTAT- -TACTGG −4 GGCAACCATTT- - - - -TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Yfs*39 V36Wfs*38 |

Accepted | 12 seeds/ft | |

| odc2-3 |

T2 odc2-3-2 |

WT: 33% +1: 55% −1: 5% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGHTACTGG −1 GGCAACCATTTTAT- - TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Yfs*39 |

Accepted | 67 seeds/ft | |

| LA0716 | |||||||

| WT | − | WT: 100% | WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG | Rejected | 0 seeds, 0 ft from 10 crosses | ||

| odc2-4 | T0 |

WT: 56% +1: 21% −2: 7% −4: 7% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGWTACTGG −2 GGCAACCATTTTA-- - TACTGG −4 GGCAACCATTT- - - - -TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Tfs *42 V36Wfs*38 |

Accepted | 61 (±5) seeds/ft | |

| odc2-5 | T0 |

WT: 54% +1: 31% −1: 5% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGDTACTGG −1 GGCAACCATTTTAT--TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Yfs*39 |

Accepted | 61 (±6) seeds/ft | |

| odc2-6 | T0 |

WT: 71% +1: 10% −1: 6% −4: 7% |

WT GGCAACCATTTTATG-TACTGG +1 GGCAACCATTTTATGWTACTGG −1 GGCAACCATTTTAT- -TACTGG −4 GGCAACCATTT- - - - -TACTGG |

L37Tfs*43 V36Yfs*39 V36Wfs*38 |

Accepted | 24 (±7) seeds/ft | |

Values represent the number of base pairs added or deleted, and the proportion of each sequence out of the total.

Inserted bases are shown in bold. W (T or A); H: (T, A, or C); and D: (T, A, or G). The PAM sites of each sequence are underlined.

Mutation symbols indicate the amino acid position and change, and the type of mutation (fs = frameshift, del = deletion, * = stop codon). For example, L37Tfs*43 is a frame shift introduced at amino acid 37, changing L to T, with a stop codon introduced at the position 43, counting from the start codon. P33-Y35del is a deletion of aa 33–35.

Figure 4.

Genetic and phenotypic analysis of WT and odc mutants in IL 3-3. A, TIDE analysis of SpODC2 gene sequences in WT and several independent T2 generation CRISPR-Cas9 mutants (odc2). B, Pollen tube growth of fps2 pollen on pistils of WT and mutant IL 3-3. Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tube. WT IL 3-3 rejects pollen of fps2 mutants, whereas several independent T2 generation odc2 mutants accept fps2 pollen. Mutations (T1 generation) in the related gene, ODC3, do not affect pollen compatibility. Scale bar: 1 mm. C, fps2 pollen tubes grow to less than 50% of the style length after 48 h on WT IL 3-3 and odc3 mutants, but reach the ovaries on mutant odc2 pistils. Data are presented as the mean ± se (n = 5).

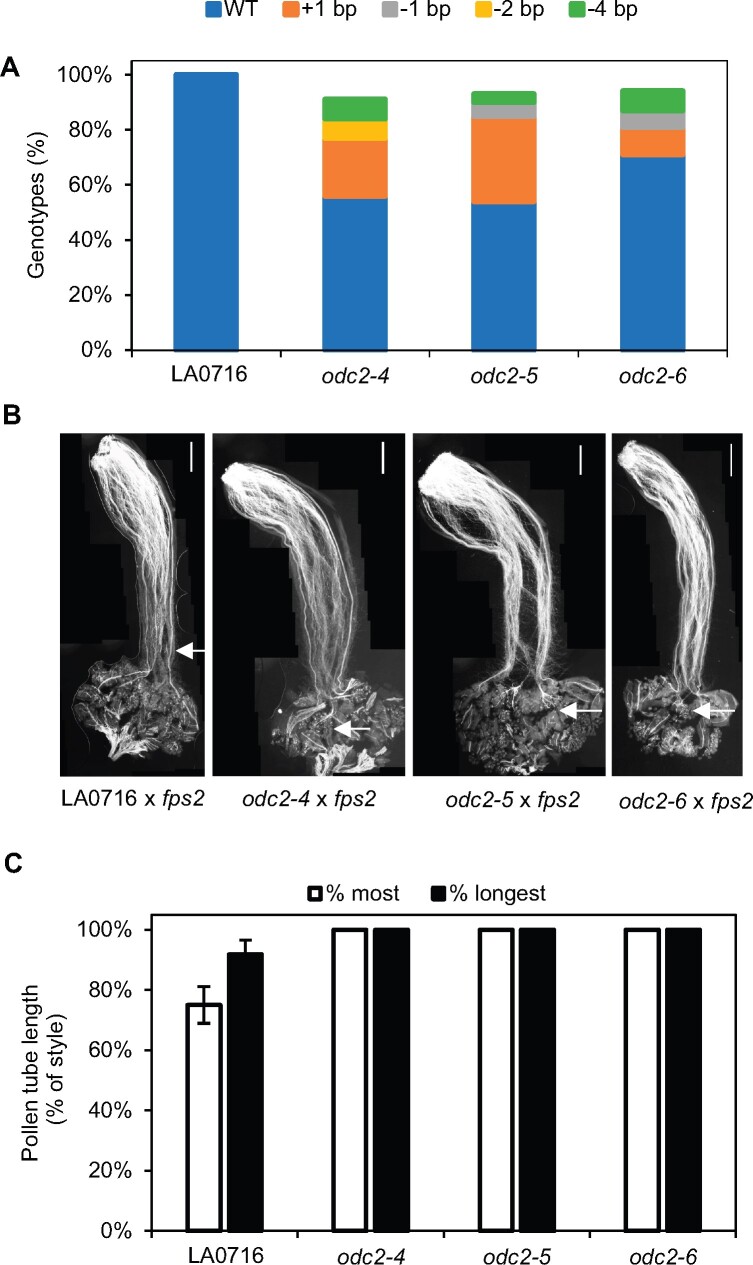

Compatible phenotypes were also observed in S. pennellii LA0716 (odc2) knockout lines. Three T0 transgenic lines (odc2-4, odc2-5, and odc2-6) had mutation rates of 44%, 46%, and 29%, respectively. All three lines accepted fps2 mutant pollen and produced fruits and seeds, in contrast to wild-type LA0716 which rejected fps2 pollen and failed to set fruit (Figure 5 and Table 1).

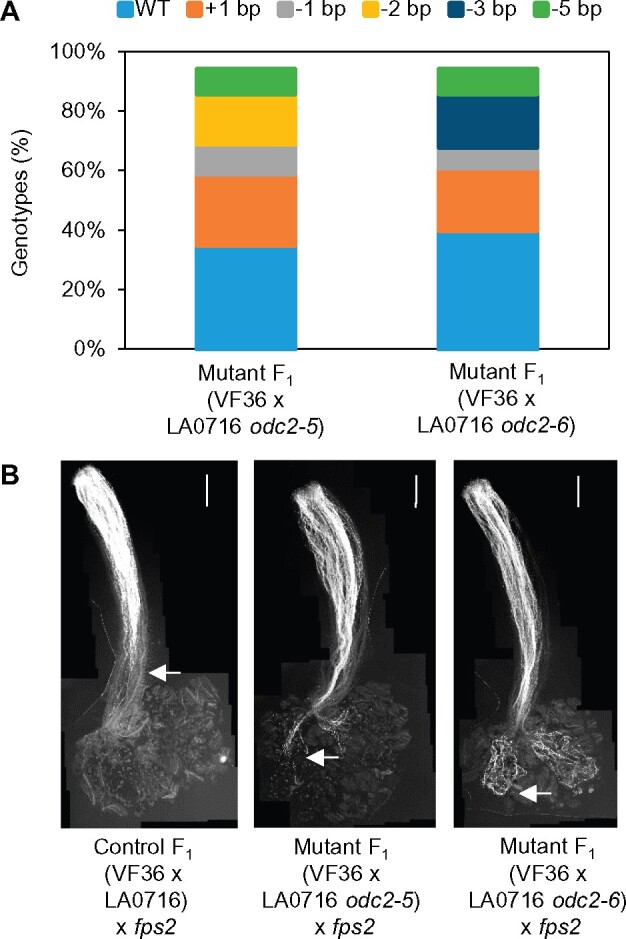

Figure 5.

Genetic and phenotypic analysis of WT and odc2 mutants in S. pennellii LA0716. A, TIDE analysis of SpODC2 sequences. B, Pollen tube growth of fps2 mutant pollen on WT and mutant LA0716. Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tube. Scale bar: 1 mm. C, fps2 pollen tubes grow to ca. 75%–85% of the style length on WT LA0716, but reach the ovaries on odc2 mutants. Data are presented as the mean ± se (n = 5).

Loss of ODC2 expression inhibits FPS2-based pollen selection

We examined whether expression of ODC2-dependent pollen rejection could explain the TRD previously observed at or near the FPS2 locus in which pollen bearing weak or null FPS2 alleles are selectively eliminated (Qin et al., 2018). In F2 progeny from wild-type S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii interspecific hybrids, there is consistent preferential transmission of pollen carrying a marker (CAPS10-18) for the high expressing FPS2P allele, and near total elimination of the weakly expressing FPS2L allele (Table 2). As a result, the F2 segregation ratios deviate strongly from the expected 1:2:1, with roughly equal frequencies of FPS2L/P heterozygotes and FPS2P/P homozygotes, and relatively few FPS2L/L homozygotes (e.g. WT 2 LL: 46 LP: 48 PP versus expected 24 LL: 48 LP: 24 PP, P < 0.0001). Pistils of F1 hybrids made with fps2 loss of function mutants in S. pennellii (i.e. with ODC2 genes intact) selectively reject fps2P mutant pollen, resulting in a reversal of TRD compared with wild-type F2’s (i.e. preferential transmission of FPS2L pollen; Qin et al., 2018). To test the involvement of ODC2, we made an interspecific F1 hybrid by crossing odc2 loss-of-function mutants in S. pennellii LA0716 onto wild-type S. lycopersicum cv VF36. Pistils of multiple independent F1 plants (genotype odc2P/ODC2L) failed to reject fps2 mutant LA0716 pollen in pollination tests (Figure 6), indicating that odc2 mutations abolish rejection of fps2 pollen. F2 progeny from two independent F1 hybrids with different odc2 mutations showed reduction in the strength of TRD for the FPS2-linked marker (Table 2, e.g. odc2-6 17 LL: 50 LP: 28 PP versus expected 20.75 LL: 41.5 LP: 20.75 PP, P = 0.24). These results demonstrate that mutation of odc2 genes from S. pennellii weakens FPS2-based pollen selection in F1 hybrids with S. lycopersicum, thereby reducing TRD at this locus in the F2 generation—further evidence that ODC2 underlies the ui3.1 incompatibility phenotype and FPS2-specific pollen selection.

Table 2.

TRD in wild-type F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii and mutant F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (odc2) populations

| Genotype |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross | Chr | Marker | Mbp | L/L | L/P | P/P | P | |

| F2 VF36 × LA0716 (WT) |

3 |

C2_At4g39630 |

55.8 |

exp 24 13 |

48 60 |

24 23 |

8.08 |

0.018 |

| 10 | CAPS10-18a | 0.518 | 2 | 46 | 48 | 64.7 | <0.0001 | |

| 12 | C2_At5g42740 | 5.31 | 14 | 60 | 22 | 7.33 | 0.026 | |

| F2 VF36 × LA0716 (odc2-6) |

3 |

C2_At4g39630 |

55.8 |

exp 20.75 17 |

41.5 49 |

20.75 27 |

2.42 | 0.30 |

| 10 | CAPS10-18a | 0.518 | 17 | 50 | 28 | 2.81 | 0.24 | |

| 12 | C2_At5g42740 | 5.31 | 8 | 40 | 45 | 31.3 | <0.0001 | |

| F2 VF36 × LA0716 (odc2-5) |

3 |

C2_At4g39630 |

55.8 |

exp 23.5 11 |

47 42 |

23.5 41 |

20.2 |

<0.0001 |

| 10 | CAPS10-18a | 0.518 | 12 | 51 | 31 | 8.36 | 0.015 | |

| 12 | C2_At5g42740 | 5.31 | 9 | 51 | 34 | 14.0 | 0.0009 | |

| F2 Moneymaker × LA0716 (WT)b | 3 |

solcap_snp_sl_30945 |

46.4 |

exp 40 19 |

80 76 |

40 65 |

26.8 | <0.0001 |

| 10 | solcap_snp_sl_46154 | 0.681 | 9 | 80 | 71 | 48.1 | <0.0001 | |

| 12 | solcap_snp_sl_59728 | 6.47 | 19 | 85 | 56 | 17.7 | 0.0001 | |

| F2 VF36 × LA0716 (WT)c |

3 |

TG102 |

47.7 |

exp 14.25 9 |

28.5 23 |

14.25 25 |

11.1 | 0.0039 |

| 10 | TG122 | 1.25 | 1 | 33 | 33 | 30.6 | <0.0001 | |

| 12 | Pgi-1 | 5.30 | 3 | 35 | 27 | 18.1 | 0.0001 | |

Observed genotype frequencies are shown for markers near inferred pollen factor loci on chromosome 3 (ui3.2), chromosome 10 (ui10.1 = FPS2), and chromosome 12 (ui12.2). Marker positions (in Mbp) are from the S. lycopersicum reference genome, SL4.0 (https://solgenomics.net). L = S. lycopersicum allele, P = S. pennellii allele. Chi-square values test the goodness-of-fit to the expected 1:2:1 ratio.

Marker from Qin et al. (2018).

Data from Sim et al. (2012).

Data from Chetelat and DeVerna (1991).

Figure 6.

Genetic and phenotypic analysis of WT and odc2 mutant F1 (VF36 × LA0716) hybrids. A, TIDE analysis of SpODC2 gene sequences in two independent mutant F1’s. B, Pollen tube growth of fps2 mutant pollen on pistils of F1 (VF36 × LA0716 WT) and F1 (VF36 × LA0716 odc2). Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tube. Scale bar: 1 mm.

ODC2 interacts genetically with a major pistil UI QTL on chromosome 12

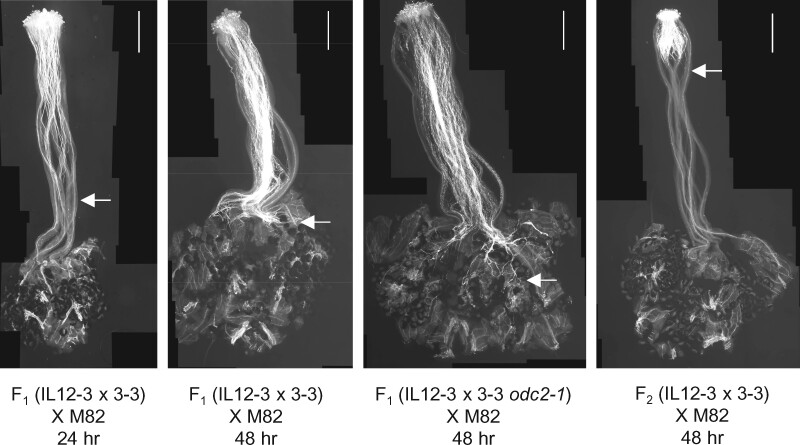

Hamlin et al. (2017) showed that IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 double introgression lines homozygous for both the ui3.1 and ui12.1 regions from S. pennellii reject tomato pollen, while the single introgression lines do not. We obtained similar results using heterozygous double ILs: pistils of F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids reject M-82 pollen (Figures 7, 8) and these crosses failed to produce seeds (0 seeds obtained from 12 flowers pollinated). We confirmed that both IL 3-3 and IL 12-3 individually accept M-82 pollen by pollinating both lines with M-82 pollen, resulting in an average of 17 and 50 seeds per fruit, respectively. These results show that rejection of S. lycopersicum pollen requires both ui3.1 and ui12.1, whereas rejection of fps2 pollen only requires ui3.1. Rejection of S. lycopersicum pollen is at least partially dominant in heterozygous double ILs, suggesting an active pistil barrier, consistent with our finding that IL 3-3/+ heterozygotes reject fps2 pollen. Interestingly, a homozygous double IL selected out of F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 rejected M-82 pollen earlier in the style compared with heterozygotes (Figure 7), suggesting the pistil barrier is strengthened by additional doses of ui3.1 and/or ui12.1.

Figure 7.

Growth of S. lycopersicum M-82 pollen tubes on pistils of heterozygous double introgression line hybrids combining introgressions on chromosomes 3 and 12 from S. pennellii. M-82 pollen is rejected on WT IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids, but not IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2) mutants. An F2 plant homozygous for both introgressions (right) rejects M-82 pollen earlier in the style compared with the heterozygotes. Scale bar: 1 mm. Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tube in each pistil.

To demonstrate that ODC2 is the gene on the IL 3-3 introgression that interacts genetically with ui12.1, we created heterozygous double ILs using mutant IL 3-3 (odc2-1) plants, i.e. F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2). M-82 pollen were compatible on these mutant double ILs (Figure 7), and resulted in fruit and seed set (48 average seeds per flower pollinated ±3), comparable to the seed set obtained from crosses onto IL 12-3 alone (50 average seeds per flower). This confirms that ODC2 interacts genetically with ui12.1 to strengthen the pistil-side UI barrier, thereby enabling rejection of S. lycopersicum pollen in the style.

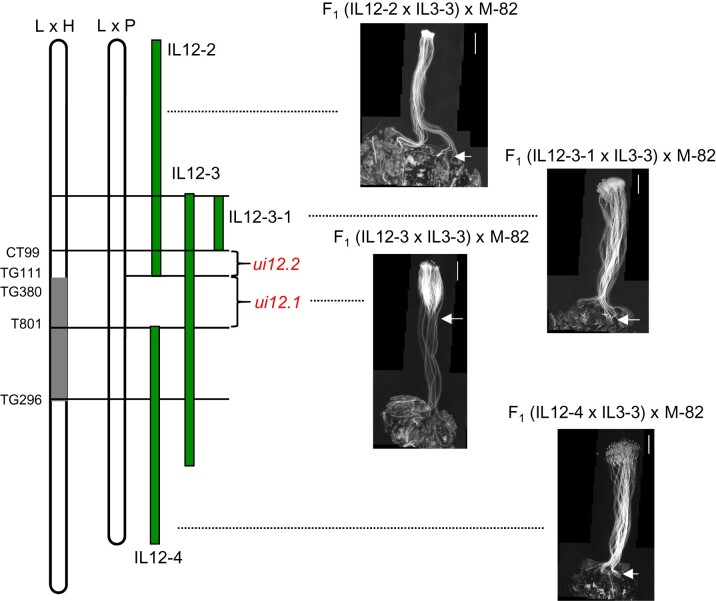

To narrow down the region of chromosome 12 that interacts with IL 3-3 (ODC2), additional heterozygous double ILs were produced by crossing IL 12-2 × IL 3-3, IL12-3-1 × IL 3-3, and IL 12-4 × IL 3-3. Among the four tested double IL heterozygotes, only F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids were capable of rejecting M-82 pollen (Figure 8). This indicates that the ui12.1 gene is located in the region unique to IL 12-3, which matches estimates from previous studies (Bernacchi and Tanksley, 1997; Covey et al., 2010; Hamlin et al., 2017). There are 218 annotated genes in this mapping bin, including the SI MGs HT-A and HT-B.

Figure 8.

Growth of M-82 pollen tubes on pistils of IL 12-3 × IL 3-3, IL 12-2 × IL 3-3, or IL 12-4 × IL 3-3 hybrids. Arrows indicate the position reached by the longest pollen tubes. Scale bar: 1 mm. M-82 pollen are rejected only by IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 pistils, which places the ui12.1 locus in the bin unique to IL 12-3. The previous approximate location of ui12.1 estimated by Bernacchi and Tanksley (1997) in S. lycopersicum × S. habrochaites cross (L × H map) is shown in gray. The map positions of the IL breakpoints are from an F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (L × P map) by Alseekh et al. (2013). The position of a putative pollen factor locus, ui12.2, is also shown.

Evidence for pollen UI loci on chromosomes 3 and 12

We observed significant TRD for markers on chromosomes 3 and 12 in F2 progeny from wild-type IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids. There was strong preferential transmission of the IL 12-3 introgression, with nearly equal proportions of LP heterozygotes and PP homozygotes (Table 3). This pattern is consistent with gametophytic selection against pollen lacking the IL 12-3 introgression. The IL 3-3 introgression showed a similar pattern of TRD, albeit less pronounced. All plants recovered were at least heterozygous for IL 3-3 or IL 12-3, i.e. no plants lacked both introgressions, suggesting pollen must contain at least one of the two introgressions to be compatible. In the mutant F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2-1) population, on the other hand, both introgressed regions segregated in normal Mendelian ratios (Table 3). This suggests there are pollen factor loci, hereinafter referred to as ui3.2 and ui12.2, on each introgression that increase compatibility of pollen tubes growing in pistils of F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrids. On mutant F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2-1) pistils, the UI barrier is weakened by the loss of ODC2 such that the ui3.2 and ui12.2 alleles from S. pennellii make little or no difference to pollen compatibility, hence they are transmitted at equal frequencies to the S. lycopersicum alleles. These results demonstrate that pollen selection at ui3.2 and ui12.2, as measured by TRD in the progeny, requires expression of ODC2 genes in the style. These results also provide further evidence of a specific genetic interaction between ui3.1 (ODC2) and ui12.1 (HT?) in contributing to the strength of pollen rejection by UI.

Table 3.

TRD in F2 progeny of IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (wild type) and IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2-1)

| F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (WT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL 12-3 genotype |

||||

| IL 3-3 genotype | LL | LP | PP | Total |

| LL | 0 (3.88) | 3 (7.75) | 6 (3.88) | 9 (15.5) |

| LP | 1 (7.75) | 15 (15.5) | 14 (7.75) | 30 (31.0) |

| PP | 3 (3.88) | 9 (7.75) | 11 (3.88) | 23 (15.5) |

| Total | 4 (15.5) | 27 (31.0) | 31 (15.5) | 62 |

| X2 IL3-3 | 6.39 | P < 0.041 | ||

| X2 IL12-3 | 24.6 | P < 0.0001 | ||

| F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2-1) | ||||

| IL 12-3 genotype |

||||

| IL 3-3 genotype | LL | LP | PP | Total |

| LL | 2 (2.69) | 3 (5.38) | 0 (2.69) | 5 (10.75) |

| LP | 9 (5.38) | 11 (10.75) | 6 (5.38) | 26 (21.5) |

| PP | 2 (2.69) | 7 (5.38) | 3 (2.69) | 12 (10.75) |

| Total | 13 (10.75) | 21 (21.5) | 9 (10.75) | 43 |

| X2 IL3-3 | 4.16 | P = 0.125 | ||

| X2 IL12-3 | 0.77 | P = 0.68 | ||

| ♀ (IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (WT)) × ♂ (IL 12-3-1 × IL 3-3) | ||||

| IL 12-3-1 genotypea |

||||

| IL 3-3 genotype | LL | LP | PP | Total |

| LL | 0 (2.9) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (11.8) |

| LP | 11 (5.9) | 11 (11.8) | 12 (5.9) | 34 (23.5) |

| PP | 2 (2.9) | 7 (5.9) | 2 (2.9) | 11 (11.8) |

| Total | 13 (11.8) | 19 (23.5) | 15 (11.8) | 47 |

| X2 IL3-3 | 12.83 | P = 0.0016 | ||

| X2 IL12-3-1 | 1.89 | P = 0.39 | ||

| ♀ (IL 12-3-1 × IL 3-3 (WT)) × ♂ (IL 12-3 × IL 3-3) | ||||

| IL 12-3 genotypea |

||||

| IL 3-3 genotype | LL | LP | PP | Total |

| LL | 1 (1.6) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (1.6) | 6 (6.5) |

| LP | 2 (3.2) | 8 (6.5) | 5 (3.2) | 15 (13) |

| PP | 1 (1.6) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (1.6) | 5 (6.5) |

| Total | 4 (6.5) | 15 (13) | 7 (6.5) | 26 |

| X2 IL3-3 | 0.69 | P = 0.71 | ||

| X2 IL12-3 | 1.31 | P = 0.52 | ||

| ♀ (IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (WT)) × ♂ (IL 12-4 × IL 3-3) | ||||

| IL 12-3 genotypeb |

||||

| IL 3-3 genotype | LL | LP | PP | Total |

| LL | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (12.5) |

| LP | 4 (6.3) | 14 (12.5) | 11 (6.3) | 29 (25) |

| PP | 8 (3.1) | 7 (6.3) | 2 (3.1) | 17 (12.5) |

| Total | 13 (12.5) | 23 (25) | 14 (12.5) | 50 |

| X2 IL3-3 | 8.04 | P = 0.018 | ||

| X2 IL12-3 | 0.36 | P = 0.84 | ||

Expected values are in parentheses. Chi-square goodness-of-fit statistics test for deviation from the expected 1:2:1 segregation ratio.

Genotype based on a marker for the region of overlap between IL 12-3-1 and IL 12-3.

Genotype based on a marker for the region of overlap between IL 12-4 and IL 12-3.

TRD was also observed in interspecific F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii LA0716 (WT) populations near both putative pollen factor loci. Markers in the ui3.2 and ui12.2 regions showed strong TRD in several independent F2’s, always with an excess of LP and PP genotypes (Table 2). The degree of TRD was not as strong as for the FPS2 region on chromosome 10, suggesting ui3.2 and ui12.2 have smaller effects on pollen fitness. Of two mutant F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii LA0716 (odc2) populations analyzed, crosses with the odc2-6 mutant showed less severe TRD on chromosome 3, suggesting that pollen selection at ui3.2, like FPS2, requires ODC2 expression. The other population (odc2-5) did not show a reduction in TRD on chromosome 3. TRD in the ui12.2 region was not reduced in progeny of either mutant (odc2-6 or odc2-5) compared with WT F2’s (Table 2). This contrasts with the F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 results (above), wherein loss of ODC2 eliminated or reduced TRD on chromosome 12. The difference might be due to other pistil-side UI factor(s) present in S. pennellii, but not on the IL 12-3 or IL 3-3 introgressions, that contribute to TRD on chromosome 12.

To map the ui12.2 pollen-side UI factor locus on IL 12-3, we crossed heterozygous IL 12-2 × IL 3-3, IL 12-3-1 × IL 3-3, and IL 12-4 × IL 3-3 hybrids as pollen donors onto F1 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 hybrid pistils. Pollen from the IL 12-2 × IL 3-3 hybrids produced progeny showing TRD, with a deficiency of LL homozygotes and an excess of LP heterozygotes and PP homozygotes for both chromosomes 3 and 12 (Table 3). Pollen from IL 12-4 × IL 3-3 and IL 12-3-1 × IL 3-3 hybrids, on the other hand, generated progeny that segregated in normal Mendelian ratios. Thus, the ui12.2 locus must lie in the region of overlap between IL 12-2 and IL 12-3, but not IL 12-3-1, which corresponds to position 5.27–61.8 Mbp on the physical map, or 54.5–66.0 cM on the genetic map (Alseekh et al., 2013, https://solgenomics.net). This mapping bin encompasses the region of maximum TRD observed in the F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii population, which lies near marker solcap_snp_sl_59728 at position 6.47 Mbp or 56.6 cM (Table 3; Sim et al., 2012, https://solgenomics.net).

To map the ui3.2 pollen factor, we looked at the region of maximum TRD on chromosome 3 in independent F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii mapping populations (Table 2). A low density map (Chetelat and DeVerna, 1991) found strong TRD for marker TG102, which is located at 53.1 Mbp. A high density map (Sim et al., 2012) showed a relatively broad area affected by TRD, with the peak bracketed between markers solcap_snp_sl_30945 to solcap_snp_sl_10377, or roughly 46.4–54.1 Mbp. This location is within the IL 3-3 introgression, which extends from marker At1g02140 to T0794-1, or ca. 49.9–59.8 Mbp (Alseekh et al., 2013, https://solgenomics.net).

Discussion

Pollen rejection in wide crosses is genetically complex, involving multiple overlapping mechanisms. In the Solanaceae, there are at least five UI mechanisms involving different pistil or pollen proteins (Bedinger et al., 2017). A widespread and well characterized type is the S-RNase- and HT-dependent UI mechanism, which occurs when pistils of SI species are pollinated by SC species, a pattern known as the SI × SC rule (Baek et al., 2015). UI arises when pollen lack one or more proteins required for resistance to pistil S-RNases, including SLFn, Cul1-P, and SSK1 proteins (Li and Chetelat, 2010, 2015; Sun and Kao, 2018). The SI-related HT proteins function in S-RNase-dependent and S-RNase-independent forms of pollen rejection (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017). Pistils of S. pennellii accession LA0716 lack S-RNase yet reject pollen of S. lycopersicum in a relatively strong and early acting form of UI (Covey et al., 2010; Baek et al., 2015). We previously characterized FPS2, a pollen factor required for compatibility on LA0716 pistils (Qin et al., 2018). Pollen lacking functional FPS2 (fps2 mutants) are incompatible, and pollen with the low expressing FPS2L allele from S. lycopersicum are outcompeted by pollen with the high expressing FPS2P allele from S. pennellii.

FPS enzymes catalyze the synthesis of FPP, a substrate in the synthesis of isoprenoids, brassinosteroids, carotenoids, ubiquinones, gibberellins, and prenylated proteins, among others (Manzano et al., 2016). Several of these end products are important in pollen tube growth. In Arabidopsis, brassinosteroids promote pollen tube growth, but evidence suggests they are produced in the transmitting tract of the style rather than within the pollen tube (Vogler et al., 2014). Gibberellins are required for pollen tube growth and pollen containing a GA-suppressing transgene are outcompeted by wild-type pollen (Singh et al., 2002). Rop (Rho of Plants) GTPase proteins are required for polar pollen tube elongation and must be prenylated (posttranslational farnesylation or geranylgeranylation) to be functional (Zheng and Yang, 2000). Thus, variation in FPS2 expression could potentially impact pollen tube growth through several different biochemical pathways. However, none of these end products of FPP synthesis have been linked to SI or UI, that we are aware of. We therefore used a genetic approach to study the mechanism of FPS2-based pollen rejection by isolating the pistil barrier factor(s) required for elimination of FPS2-deficient pollen.

We hypothesized that this pistil factor would likely correspond to a previously mapped UI QTL in wide crosses of tomato. Major pistil factor loci on chromosomes 1, 3, and 12 have been reported in S. pennellii and its close relative S. habrochaites (Bernacchi and Tanksley, 1997; Hamlin et al., 2017; Jewell et al., 2020). The chromosome 1 factor maps near the S-locus (Jewell et al., 2020), and probably encodes an S-RNase. However, S. pennellii accession LA0716 lacks S-RNase (Covey et al., 2010; Li and Chetelat, 2015), and introgression lines containing the ui1.1 region accept S. lycopersicum pollen (Hamlin et al., 2017). We therefore excluded ui1.1 on chromosome 1. The gene on chromosome 12, ui12.1, maps to the same region as genes encoding the HT-A and HT-B proteins (Covey et al., 2010; Hamlin et al., 2017), which are essential SI modifier factors in the pistil, and play a role in S-RNase independent pollen rejection (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017). The chromosome 3 QTL, ui3.1, which had not been isolated, interacts genetically with ui12.1 to strengthen UI (Hamlin et al., 2017). We therefore examined whether ui3.1 or ui12.1 expression in the pistil is required for FPS2-based pollen rejection.

A single pistil factor locus is required and sufficient for rejection of fps2 pollen

We previously generated fps2−/− loss of function mutants in S. pennellii LA0716, which lacks S-RNase (Qin et al., 2018). We used fps2 pollen as a tester on pistils of introgression lines containing the ui3.1 or ui12.1 genomic regions from S. pennellii in the background of S. lycopersicum (Eshed and Zamir, 1994; Alseekh et al., 2013). Only one line, IL 3-3, among three overlapping chromosome 3 ILs representing the ui3.1 region, rejected fps2 pollen. This suggests a single pistil factor locus (ui3.1) in the region unique to IL 3-3 is required and sufficient for FPS2-based pollen rejection. The inferred position of ui3.1 is consistent with but more precise than previous estimates (Jewell, 2016; Song et al., 2016). Interestingly, pollen of cultivated tomato, which express low levels of FPS2 transcript (Qin et al., 2018), are compatible on IL 3-3 pistils. Therefore, the fps2 null mutants are a more sensitive pollen tester genotype than S. lycopersicum pollen, which facilitated isolation of the interacting pistil factor locus.

Candidates for ui3.1

We mapped ui3.1 to a genomic region corresponding to ca. 55 and 64 Mbp on the reference genomes of tomato and S. pennellii, respectively (https://www.solgenomics.net), or ca. 8.0 cM on the EXPEN 2000 genetic map (Alseekh et al., 2013). Within this region, the S. pennellii genome contains 108 annotated genes, none of which were known to function in SI or UI. However, genes Solyc03g098300 (herein ODC2) and Solyc03g098310 (herein ODC3) were described as upregulated in UI competent tissues, with ca. 142-fold and 400-fold greater abundance of Solyc03g098300 and Solyc03g098310 transcripts, respectively, in S. pennellii versus S. lycopersicum or immature S. pennellii styles (Pease et al., 2016). However, our analysis of expression using gene-specific primers and RT-PCR found no evidence that Solyc03g098310 is expressed in styles. In contrast, we found Solyc03g098300 (ODC2) transcripts are at least 1,034-fold more abundant in S. pennellii than S. lycopersicum styles.

Furthermore, comparison of the genome assemblies of the two species reveals copy number variation for this gene: the S. lycopersicum genome contains one ODC2 gene, while the S. pennellii LA0716 genome contains four. An independent de novo genome assembly of S. pennellii accession LA5240 also contains four ODC2 gene copies (https://plabipd.de/portal/solanum-pennellii), indicating the copy number variation is real and not limited to accession LA0716. The extra gene copies would account for only a four-fold difference in expression, however, so there must be other factors involved (e.g. promoters). Based on the observed differences in expression and gene copy number, we considered Solyc03g098300 the mostly likely ui3.1 candidate. Two other genes, one encoding a chromosome alignment-maintaining phosphoprotein 1-like protein, the other annotated as an Arf-GAP protein, were also considered as possible candidates based on pistil expression and/or amino acid substitutions. Mutants in all four were generated by CRISPR-Cas9 in the background of IL 3-3 and tested for their reaction to fps2 mutant pollen. Only the odc2 CRISPR-Cas9 knockout lines showed a change in phenotype and failed to reject fps2 pollen.

odc2−/− mutants are FPS2-nonselective

Introduction of odc2 loss-of-function frameshift and deletion mutations into IL 3-3 using CRISPR-Cas9 abolished the ability of pistils to reject fps2 mutant pollen. The four ODC2 genes in S. pennellii are nearly identical, so we designed a single gRNA that would target all copies simultaneously. Analysis of the ODC2 sequence traces in the transgenic IL 3-3 lines using the TIDE algorithm (Brinkman et al., 2014) showed that each of the independent transformants retained some proportion of WT ODC2 sequences, especially the two T2 progeny of odc2-3 line which retained >30% of WT ODC2 genotype. Nonetheless, these odc2 knockout mutants accepted fps2 pollen. One possible explanation is that there is a quantitative effect of ODC2 expression level on pollen rejection, with a minimum threshold of ODC2 function needed for rejecting fps2 mutant pollen. Alternatively, it’s possible that only a subset of the four ODC2 genes are highly expressed and are functional, and that only those genes were mutated in line odc2-3, i.e. the remaining, WT ODC2(s) genes are non-functional. However, it is difficult to test this due to their high sequence similarity. In either case, it is important to identify the biochemical product of the ODC2 genes and how it acts as a barrier to pollen tube growth. Based on the compatible phenotype resulting from loss of function mutations in ODC2, we conclude that high level expression is an essential component of the pistil barrier that establishes FPS2-based pollen rejection/selection.

Similar odc2 mutants induced in the background of S. pennellii LA0716 also failed to reject fps2 pollen. In addition, they showed nearly normal Mendelian transmission of the two parental FPS2 alleles (FPS2L versus FPS2P) in F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (odc2). These observations suggest that other pistil factor loci in S. pennellii cannot complement odc2 mutations for FPS2-based pollen rejection or selection.

These results establish a functional link between ODC2 expression in the pistil and selective inhibition of pollen tube growth according to their FPS2 expression level. ODC enzymes catalyze the conversion of ornithine to putrescine, the first committed step of PA biosynthesis. PAs have been implicated in a variety of plant developmental and stress response processes, including pollen development, germination, and pollen tube growth (Tiburcio et al., 2014). The PA spermidine promotes Arabidopsis pollen germination in vitro, but inhibits pollen tube elongation (Rodriguez-Enriquez et al., 2013). PAs can also be precursors in the synthesis of gamma amino butyric acid (GABA; Shelp et al., 2012), a signaling molecule produced by the pistil that regulates pollen tube growth and guidance via concentration gradient from stigma to ovule micropyle (Palanivelu et al., 2003); at low concentrations GABA stimulates pollen tube growth, but at high levels is inhibitory. In Citrus, which also has S-RNase-based SI (Liang et al., 2020), higher PA levels (putrescine and spermidine) were observed in pistils after incompatible self pollinations than after compatible cross pollinations (Aloisi et al., 2020).

ui12.1 strengthens ODC2-dependent pollen rejection

Our results show that ODC2 interacts genetically with a UI pistil factor locus on chromosome 12 that strengthens pollen selection at FPS2. Expression of functional ODC2 from S. pennellii is required for rejection of pollen lacking functional FPS2. However, it is not sufficient for rejection of pollen from S. lycopersicum, which express low but detectable levels of FPS2 transcript (Qin et al., 2018). Since WT IL 3-3 (ODC2) pistils fail to reject tomato pollen, there must be additional UI factors involved. Pistils of hybrids containing both the IL 3-3 (ODC2) and IL 12-3 (ui12.1) introgressions from S. pennellii are able to reject S. lycopersicum pollen. We show that the ODC2-interacting locus (ui12.1) maps to the same genetic interval as a tandem repeat of genes encoding the HT-A and -B proteins, which function in both S-RNase dependent and independent self- and interspecific pollen rejection (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2014, 2017). Our results thus support earlier evidence that ui12.1 likely encodes the HT proteins (Covey et al., 2010; Hamlin et al., 2017). The biochemical basis for the genetic interaction between ODC2 and ui12.1 is unknown.

Because the phenotype of ui3.1 and ui12.1 is partially dominant in heterozygous double ILs, both loci must express an active pistil barrier factor that inhibits pollen tube growth, in this case according to its level of FPS2 expression. This contrasts with other possible causes of pollination failure, including loss or divergence of pollen–ovule guidance or chemoattractant factors, such as the LURE1 peptides (Okuda et al., 2009). Interestingly, fps2 pollen are compatible on IL 12-3 pistils, suggesting that in the absence of ODC2, ui12.1 alone does not confer FPS2 selectivity. This is supported by our finding that the FPS2 region segregates in normal Mendelian fashion in F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii (odc2); the F1 hybrid pistils in this case express functional ui12.1 but not ODC2. Together these results suggest that high expression of ODC2 is essential for FPS2-based pollen rejection/selection, while ui12.1 (HT?) appears to amplify the effect of ODC2.

TRD points to additional pollen factor loci

We detected significant TRD for markers on chromosomes 3 and 12, consistent with gametophytic selection at pollen factor loci. In each case there was an excess transmission of the S. pennellii parental allele. TRD was manifested only when the female parent was heterozygous for both IL 3-3 (ODC2) and IL 12-3 (ui12.1) regions from S. pennellii. The TRD was seen in F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 progeny, as well as in interspecific F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii. The pattern of TRD was consistent with the selective elimination of pollen carrying the S. lycopersicum alleles at pollen factor loci on the IL 3-3 and IL 12-3 introgressions. While other causes of TRD, such as differential postzygotic survival, cannot be ruled out, the fact that nearly normal Mendelian transmission ratios were observed on pistils homozygous for odc2 loss of function mutations strongly supports the hypothesis of pollen selection, in this case specifically dependent on ODC2 expression. Similar TRD on chromosomes 3, 10, and 12 has been consistently observed in multiple independent F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii populations, from both SC and SI accessions of S. pennellii (Chetelat and DeVerna, 1991; Trujillo-Moya et al., 2011; Sim et al., 2012), indicating the trends are robust and do not result from the loss of SI per se. The genetic positions of these pollen factor loci were estimated from the chromosomal regions exhibiting maximum TRD, in this case where the LL homozygote frequency was lowest and where the LP and PP genotype frequencies approached 50%, and by comparing overlapping ILs near each locus.

Conclusions

The major finding of this study is that the ODC2 locus in S. pennellii, comprised of four nearly identical gene copies, is required for FPS2-based, S-RNase independent pollen rejection. This conclusion is supported by four lines of functional evidence: (1) pistils of odc2 knockout lines in the IL 3-3 background fail to reject pollen of fps2 mutants in S. pennellii; (2) pistils of IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2) hybrids fail to reject pollen of S. lycopersicum, which expresses low levels of FPS2; (3) odc2 knockout mutants in S. pennellii exhibit nearly equal pollen transmission of FPS2 alleles in F2 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii and (4) odc2 mutations abolish TRD at putative pollen factor loci on chromosomes 3 and 12 in F2 IL 12-3 × IL 3-3 (odc2). ODC2 encodes an active pistil barrier factor that interacts genetically with ui12.1 (HT?) to strengthen FPS2-based pollen rejection. Our results thus provide direct genetic evidence that PA biosynthesis in the pistil and isoprenoid synthesis in pollen are required components of this pollen rejection mechanism.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The plant materials used in this work include S. lycopersicum cultivars M-82 (LA3475) and VF-36 (LA0490), S. pennellii accession LA0716 (SC biotype lacking S-RNase), and the S. pennellii introgression lines IL 3-2 (LA4044), IL 3-3 (LA3488), IL 3-4 (LA4046), IL 12-2 (LA4099), IL 12-3 (LA4100), IL 12-3-1 (LA4101), and IL 12-4 (LA4102). Seeds of all accessions were obtained from the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center at UC Davis (https://tgrc.ucdavis.edu/). All of the IL lines were confirmed by genotyping with relevant CAPS markers (Supplemental Table S2). FPS2 loss of function mutants (fps2−/−) in the background of LA0716 were obtained by CRISPR-Cas9 as previously described (Qin et al., 2018) and were used as pollen testers to map and clone the interacting pistil factor ui3.1. All plants were grown in the Department of Plant Sciences greenhouse facility at UC Davis.

Crosses and pollen tube staining analysis

Controlled crosses were made using standard emasculation and pollination techniques. Unopened flowers at 1–2 d pre-anthesis were emasculated then pollinated 1 d later. For pollen tube growth observations, pollinated flowers were harvested 48 h after pollination. Pistils were stored in fixative solution (3:1 ethanol 95% (v/v): glacial acetic acid). Pollen tube staining and imaging were performed as previously described (Li and Chetelat, 2010). At least five flowers per plant were analyzed for each pollination test.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted as described previously (Li and Chetelat, 2010). Standard PCR reactions were set up in 20 µL volume with Amplitaq DNA polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific). Ten microliters of PCR product was used to set up restriction enzyme digestions in a total volume of 20 µL with 2 unit of enzymes. Marker sequences and restriction enzyme used for revealing polymorphism are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

RNA extraction

Analysis of expression of candidate genes was performed using leaf, pollen, and style total RNA extracted by TRIZOL reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For RT-PCR, 2 µg of RNA was treated with DNaseI, then used for cDNA synthesis with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Inc.). Each PCR reaction contained 0.5 µL cDNA in a total volume of 20 µL. For real-time quantitative PCR, RNA was isolated from three biological replicates each from M-82 or LA0716 leaf, style, and ovary. For style and ovary tissues, 10–20 flowers were dissected and pooled for each replicate. Total RNAs were treated with DNaseI (New England Biolabs, Inc.). Synthesis of cDNA was carried out with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time qPCR analyses were carried out as previously described (Qin et al., 2012) using the iTaq SYBR Green Universal mix (Bio-Rad). Actin was used as a control gene. Primers for RT-PCR and RT-qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

CRISPR-Cas9 vector construction and plant transformation

The CRISPR-Cas9 system was used to generate loss of function mutants for candidate genes. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) for each candidate gene were designed with the CRISPR-PLANT program (https://www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr/index.html; Supplemental Table S2). Because of the high similarities between ODC2 and ODC3 genes, we selected PAM sites unique to each gene to provide specific targeting of ODC2 or ODC3 (Supplemental Figure S4). Due to the near identical sequences among the four ODC2 genes, it was impossible to design gRNAs unique to specific gene copies. Therefore, a single gRNA sequence was designed to target all four genes, while carrying enough mismatch so as not to target ODC3 or ODC1. This ODC2 gRNA also has a restriction site (RsaI) near the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) NGG site to facilitate the identification of mutant plants by loss of the restriction site.

The GATEWAY cloning system used in this study is based on Fauser et al. (2014). Protospacers were first introduced to the gRNA entry vector pEn-Chimera (Supplemental Table S3). The plant expression destination vector pDe-kan-CAS9 was modified by replacing the BAR resistance cassette with the NPT II gene (kanamycin resistance) driven by the NOS promoter. All plasmids (Supplemental Table S3) were then transformed into ElectroMax Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 cells (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Transformations of S. pennellii LA0716 and introgression line IL 3-3 were carried out as previously described (Qin et al., 2018).

Genotyping and sequencing mutations in the transgenic lines

CAPS markers were used to initially assess transgenic lines targeting the ODC2, ODC3, or Arf-GAP genes. In each case, the WT sequences contain restriction sites adjacent to the PAM site. Mutations would likely result in the loss of the restriction site, resulting in a larger band after restriction digestion of the PCR product. No suitable restriction sites were present in the Solyc03g098480 gRNA, so mutations were identified by sequencing PCR product. For ODC2 transgenic lines, SpODC2 genes were amplified by CAPS ODC2 F/R primers (Supplemental Table S2) from genomic DNA; the primer set was designed to specifically amplify the S. pennellii, not the S. lycopersicum ODC2 genes . PCR product was purified by GenElute PCR clean-Up kit (Sigma–Aldrich) and subjected to Sanger sequencing. Sequencing traces of LA0716 and transgenic lines were analyzed by TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition, Brinkman et al., 2014). PCR product was also cloned to pGEM-T easy vectors and transformed to Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Multiple clones were sequenced for each transgenic line to characterize their specific mutations.

Statistical analyses

The significance of TRD was assessed using chi-square goodness-of-fit statistics calculated at http://www.vassarstats.net. Gene trees of predicted ODC protein sequences were generated with MEGAX (https://www.megasoftware.net) and were based on the neighbor-joining method.

Accession numbers

The following ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) gene sequences were retrieved from Solgenomics (https://solgenomics.net/): SpODC2a (Sopen03g029020), SpODC2b (Sopen03g029030), SpODC2c (Sopen03g029040), SpODC2d (Sopen03g029050), SlODC2 (Solyc03g098300), SlODC3 (Solyc03g098310), SpODC3 (Sopen03g029060), SlODC1 (Solyc04g082030), and SpODC1 (Sopen04g035680). The sequences of GmODC (NP_001238629.1), DsODC (X87847), GmADC (AAD09204.1), and SlADC (NP_001234649.2) were obtained from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank). Sp = S. pennellii, Sl = S. lycopersicum, Ds = Datura stramonium, Gm = Glycine max; ADC, arginine decarboxylase.

Supplemental data

The following Supplemental Materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Pollen tube growth of S. pennellii LA0716 fps2 mutant pollen on pistils of M-82, homozygous IL 12-3 and IL 3-3 introgression lines, and heterozygous IL 3-3.

Supplemental Figure S2. Qualitative RT-PCR analysis of transcript levels for genes in the ui3.1 region.

Supplemental Figure S3. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of T0 transgenic IL 3-3 lines containing CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations in several ui3.1 gene candidates.

Supplemental Figure S4. Alignment of S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii ODC2 and ODC3 gene sequences.

Supplemental Table S1. List of S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii genes in the bin unique to IL 3-3

Supplemental Table S2. List of primers and markers

Supplemental Table S3. Vectors and constructs used in this research

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center for providing seed of the parental lines used in this study, Akash Mishra for assistance with pollen tube visualization, and Dr. Martha Mutschler for helpful input.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation, grant no. MCB 1127059.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

X.Q. designed and carried out the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. R.T.C. conceived the original research, helped to analyze the data, and wrote the article with contributions from X.Q.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Roger T. Chetelat (trchetelat@ucdavis.edu).

References

- Alabadi D, Carbonell J (1998) Expression of ornithine decarboxylase is transiently increased by pollination, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and gibberellic acid in tomato ovaries. Plant Physiol 118: 323–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi I, Distefano G, Antognoni F, Potente G, Parrotta L, Faleri C, Gentile A, Bennici S, Mareri L, Cai G, Del Duca S (2020) Temperature-dependent compatible and incompatible pollen-style interactions in Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan. Show different transglutaminase features and polyamine pattern. Front Plant Sci 11: 1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alseekh S, Ofner I, Pleban T, Tripodi P, Di Dato F, Cammareri M, Mohammad A, Grandillo S, Fernie AR, Zamir D (2013) Resolution by recombination: breaking up Solanum pennellii introgressions. Trends Plant Sci 18: 536–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek YS, Covey PA, Petersen JJ, Chetelat RT, McClure B, Bedinger P (2015) Testing the ‘SI × SC rule’: pollen–pistil interactions in interspecific crosses between members of the tomato clade (Solanum section Lycopersicon, Solanaceae). Am J Bot 102: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedinger PA, Broz AK, Tovar-Mendez A, McClure B (2017) Pollen–pistil interactions and their role in mate selection. Plant Physiol 173: 79–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi D, Tanksley SD (1997) An interspecific backcross of Lycopersicon esculentum × L. hirsutum: linkage analysis and a QTL study of sexual compatibility factors and floral traits. Genetics 147: 861–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A, Scossa F, Bolger ME, Lanz C, Maumus F, Tohge T, Quesneville H, Alseekh S, Sørensen I, Lichtenstein G, et al. (2014) The genome of the stress-tolerant wild tomato species Solanum pennellii. Nat Genet 46: 1034–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B (2014) Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res 42: e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetelat RT, DeVerna JW (1991) Expression of unilateral incompatibility in pollen of Lycopersicon pennellii is determined by major loci on chromosomes 1, 6 and 10. Theor Appl Genet 82: 704–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DH, Kumar R, Headland LR, Ranjan A, Covington MF, Ichihashi Y, Fulop D, Jimenez-Gomez JM, Peng J, Maloof JN, et al. (2013) A quantitative genetic basis for leaf morphology in a set of precisely defined tomato introgression lines. Plant Cell 25: 2465–2481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey P, Kondo K, Welch L, Frank E, Sianta S, Kumar A, Nuez R, Lopez-Casado G, van der Knaap E, Rose J, et al. (2010) Multiple features that distinguish unilateral incongruity and self-incompatibility in the tomato clade. Plant J 64: 367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Zamir D (1994) A genomic library of Lycopersicon pennellii in L. esculentum: a tool for fine mapping of genes. Euphytica 79: 175–180 [Google Scholar]

- Fauser F, Schiml S, Puchta H (2014) Both CRISPR/Cas‐based nucleases and nickases can be used efficiently for genome engineering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 79: 348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S, Kubo K, Takayama S (2016) Non-self- and self-recognition models in plant self-incompatibility. Nat Plants 2: 16130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Valencia LE, Bravo-Alberto CE, Wu HM, Rodriguez-Sotres R, Cheung AY, Cruz-Garcia F (2017) SIPP, a novel mitochondrial phosphate carrier, mediates in self-incompatibility. Plant Physiol 175: 1105–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JAP, Sherman NA, Moyle LC (2017) Two loci contribute epistastically to heterospecific pollen rejection, a postmating isolating barrier between species. G3 7: 2151–2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock CN, Kent L, McClure BA (2005) The stylar 120kDa glycoprotein is required for S-specific pollen rejection in Nicotiana. Plant J 43: 716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell CP (2016) Genetics and evolution of reproductive behavior in Solanaceae. Ph.D. thesis, Indiana University

- Jewell CP, Zhang SV, Gibson MJS, Tovar-Mendez A, McClure B, Moyle LC (2020) Intraspecific genetic variation underlying postmating reproductive barriers between species in the wild tomato clade (Solanum sect. Lycopersicon). J Hered 111: 216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Duran K, McClure B, Garcia-Campusano F, Rodriguez-Sotres R, Cisneros J, Busot G, Cruz-Garcia F (2013) NaStEP: a proteinase inhibitor essential to self-incompatibility and a positive regulator of HT-B stability in Nicotiana alata pollen tubes. Plant Physiol 161: 97–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Yamamoto M, Matton DP, Sato T, Hirai M, Norioka S, Hattori T, Kowyama Y (2002) Cultivated tomato has defects in both S-RNase and HT genes required for stylar function of self-incompatibility. Plant J 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Entani T, Takara A, Wang N, Fields AM, Hua Z, Toyoda M, Kawashima S, Ando T, Isogai A, et al. (2010) Collaborative non-self recognition system in S-RNAse-based self-incompatibility. Science 330: 796–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Paape T, Hatakeyama M, Entani T, Takara A, Kajihara K, Tsukahara M, Shimizu-Inatsugi R, Shimizu KK, Takayama S (2015) Gene duplication and genetic exchange drive the evolution of S-RNase-based self-incompatibility in Petunia. Nat Plants 1: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Chetelat RT (2010) A pollen factor linking inter- and intraspecific pollen rejection. Science 330: 1827–1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Chetelat RT (2015) Unilateral incompatibility gene ui1.1 encodes an S-locus F-box protein expressed in pollen of Solanum species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 4417–4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang M, Cao Z, Zhu A, Liu Y, Tao M, Yang H, Xu Q Jr, Wang S, Liu J, Li Y, et al. (2020) Evolution of self-compatibility by a mutant Sm-RNase in citrus. Nat Plants 6: 131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano D, Andrade P, Caudepon D, Altabella T, Arro M, Ferrer A (2016) Suppressing farnesyl diphosphate synthase alters chloroplast development and triggers sterol-dependent induction of jasmonate- and Fe-related responses. Plant Physiol 172: 93–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure BA, Mou B, Canevascini S, Bernatzky R (1999) A small asparagine-rich protein required for S-allele-specific pollen rejection in Nicotiana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 13548–13553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda S, Tsutsui H, Shiina K, Sprunck S, Takeuchi H, Yui R, Kasahara RD, Hamamura Y, Mizukami A, Susaki D, et al. (2009) Defensin-like polypeptide LUREs are pollen tube attractants secreted from synergid cells. Nature 458: 357–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanivelu R, Brass L, Edlund AF, Preuss D (2003) Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell 114: 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease JB, Guerrero RF, Sherman NA, Hahn MW, Moyle LC (2016) Molecular mechanisms of postmating prezygotic reproductive isolation uncovered by transcriptome analysis. Mol Ecol 25: 2592–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Zhang W, Dubcovsky J, Tian L (2012) Cloning and comparative analysis of carotenoid beta-hydroxylase genes provides new insights into carotenoid metabolism in tetraploid (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum) and hexaploid (Triticum aestivum) wheat grains. Plant Mol Biol 80: 631–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin XQ, Li WT, Liu Y, Tan ML, Ganal M, Chetelat RT (2018) A farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene expressed in pollen functions in S-RNase-independent unilateral incompatibility. Plant J 93: 417–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Enriquez MJ, Mehdi S, Dickinson HG, Grant-Downton RT (2013) A novel method for efficient in vitro germination and tube growth of Arabidopsis thaliana pollen. New Phytol 197: 668–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp BJ, Bozzo GG, Trobacher CP, Zarei A, Deyman KL, Brikis CJ (2012) Hypothesis/review: contribution of putrescine to 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) production in response to abiotic stress. Plant Sci 193–194: 130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim S-C, Durstewitz G, Plieske J, Wieseke R, Ganal MW, Van Deynze A, Hamilton JP, Buell CR, Causse M,, Wijeratne S, et al. (2012) Development of a large SNP genotyping array and generation of high-density genetic maps in tomato. PLoS ONE 7: e40563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh DP, Jermakow AM, Swain SM (2002) Gibberellins are required for seed development and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 3133–3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Cui L, Wang X, Gao J, Guo Y, Huang Z, Du Y (2016) Fine mapping of UI3a, a gene controlling unilateral incompatibility in tomato. Acta Horticult Sin 43: 1275–1285 [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Kao T-h (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of PiSSK1 reveals essential role of S-locus F-box protein-containing SCF complexes in recognition of non-self S-RNases during cross-compatible pollination in self-incompatible Petunia inflata. Plant Reprod 31: 129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiburcio AF, Altabella T, Bitrian M, Alcazar R (2014) The roles of polyamines during the lifespan of plants: from development to stress. Planta 240: 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Rodriguez MD, Cruz-Zamora Y, Juarez-Diaz JA, Mooney B, McClure BA, Cruz-Garcia F (2020) NaTrxh is an essential protein for pollen rejection in Nicotiana by increasing S-RNase activity. Plant J 103: 1304–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Mendez A, Kumar A, Kondo K, Ashford A, Baek YS, Welch L, Bedinger PA, McClure BA (2014) Restoring pistil-side self-incompatibility factors recapitulates an interspecific reproductive barrier between tomato species. Plant J 77: 727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Mendez A, Lu L, McClure B (2017) HT proteins contribute to S-RNase-independent pollen rejection in Solanum Plant J 89: 718–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo-Moya C, Gisbert C, Vilanova S, Nuez F (2011) Localization of QTLs for in vitro plant regeneration in tomato. BMC Plant Biol 11: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler F, Schmalzl C, Englhart M, Bircheneder M, Sprunck S (2014) Brassinosteroids promote Arabidopsis pollen germination and growth. Plant Reprod 27: 153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JS, Der JP, dePamphilis CW, Kao TH (2014) Transcriptome analysis reveals the same 17 S-locus F-box genes in two haplotypes of the self-incompatibility locus of Petunia inflata. Plant Cell 26: 2873–2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Huang J, Zhao Z, Li Q, Sims TL, Xue Y (2010) The Skp1-like protein SSK1 is required for cross-pollen compatibility in S-RNase-based self-incompatibility. Plant J 62: 52–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZL, Yang ZB (2000) The Rop GTPase: an emerging signaling switch in plants. Plant Mol Biol 44: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.