Abstract

Introduction

Healthcare systems are being bombarded during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding burnout, compassion fatigue, and potential protective factors, such as compassion satisfaction, will be important in supporting the vital healthcare workforce. The goal of the current study was to understand the key factors of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among healthcare employees during the pandemic within the U.S. in April 2020.

Methods

The authors conducted a single-center, cross-sectional online survey using the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Questionnaire and three open-ended questions around stress and responses to stress during COVID-19 at a large Midwestern academic medical center with nearly 16,000 employees.

Results

Healthcare employees (613) representing over 25 professions or roles and 30 different departments within the health system were surveyed. Participants reported low levels of compassion fatigue and burnout, but moderate levels of compassion satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction was notably higher than prior literature. Key areas of stress outside of work included family, finances and housing, childcare and homeschooling, and personal health.

Conclusions

This was a cross-sectional survey, limiting causal analyses. Also, based on the qualitative responses, the ProQOL was somewhat insufficient in assessing the breadth of stressors, particularly outside of work, that healthcare employees faced due to the pandemic. Although compassion satisfaction was elevated during the initial phases of the pandemic, providing some possible protection against burnout, this may change as COVID-19 continues to surge. Healthcare systems are encouraged to assess and address the broad range of work and non-work-related stressors to best serve their vital workforce.

Keywords: psychological burnout, professional burnout, compassion fatigue, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic uniquely has stressed the modern healthcare landscape. Systems are being pushed to the edge of their resources, and fast-paced circumstances have required all who work within healthcare settings to make frequent and sometimes drastic changes to their professional and personal lives. For medical providers and other healthcare workers already at risk for burnout and compassion fatigue,1,2 the importance of understanding the impact of COVID-19 on mental health3,4 and emotional and mental well-being is paramount.5

Early evidence of the impact of COVID-19 for healthcare workers included a recent cross-sectional study of healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in China which demonstrated high levels of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34.0%), and general distress (71.5%) during the COVID-19 pandemic.6 Another study examining psychological status of medical workers at a single center in China found higher levels of fear, anxiety, and depression for clinical staff compared to non-clinical staff.7

Prior research around sentinel events showed a range of typical psychological effects, including impairments in functioning, lost resources, points of resiliency, and use of coping responses to mitigate the impact of the disaster.8,9 Prior to COVID-19, there had been growing concern about burnout in the medical workforce as a response to chronic and acute stressors.10,11 Burnout is the “chronic psychological syndrome of perceived demands from work outweighing perceived resources in the work environment”.12 Signs of burnout include negative work-related attitudes, cynicism, dissatisfaction, and some apathy around work-related issues. While related, there has been less attention on compassion fatigue, which occurs “when caregivers have such deep empathy, they develop symptoms of trauma similar to the patient”.13 Signs of compassion fatigue can encompass physical (e.g., fatigue, insomnia, headaches), psychological (e.g., irritability, sadness, despair), relational (e.g., emotional numbness toward others, blaming patients), and cognitive disturbances (e.g., feeling disorganized or scattered, difficulty with focus).14 Therefore, one might anticipate compassion fatigue and burnout to be especially important factors to monitor in the medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inversely, constructs such as resiliency and compassion satisfaction have been shown to be protective factors for healthcare workers.15 Compassion satisfaction allows helpers to derive a sense of value, meaning, and purpose from their challenging work. Slocum-Gori et al.16 explained this as “the emotional reward for caring for others”. While increased levels of stress from the rapid changes in healthcare due to the pandemic may impact healthcare workers negatively, the elevation of their status as highly “essential” and their celebration as “heroes” may yield positive implications for them as well. Prior research looking at burnout and compassion satisfaction among healthcare workers has shown that roughly one-quarter of providers may experience high levels of compassion fatigue and burnout, with 50% or more at moderate levels.17,18 Inversely, only around 20 – 30% of healthcare workers reported a high level of compassion satisfaction from their work.19

During the time of our study (April 2020), national headlines contained a regular stream of developments: COVID-19 related hospitalizations and deaths in New York City, widespread deficiencies in access to personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline healthcare workers,20 and growing prevalence and incidence rates occurring nationally as well as locally.21,22 Local institution guidelines were calling for changes to nearly all aspects of daily activities. Like most medical centers across the country, many clinicians, students, and researchers were sent to work remotely as distance service became “the new normal”, and local, regional, and national outlets began to communicate messages emphasizing potential risks and demonstrating efforts to ascertain individuals’ needs and promote resiliency.

While recent studies showed that healthcare workers were being stressed and strained in this current crisis,6,7 less is known about how the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting compassion fatigue and burnout, and whether a sense of purpose or shared mission in response to the crisis can increase compassion satisfaction and possibly protect healthcare workers from lasting distress. To address this question, an online survey was designed and administered using the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Questionnaire to measure these variables among healthcare workers at one Midwestern academic medical center. To our knowledge, this was the largest study conducted in the U.S to measure the professional quality of life and well-being during COVID-19 for the medical workforce.

METHODS

Study Design and Instrument

A 45-item survey was designed which included demographics, basic employee information (i.e., profession/ role, department), open-ended questions on resources and stressors, and the ProQOL Questionnaire, ProQOL 5.19 The ProQOL is a well-established and validated measure23 and includes three scales: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress (a component of compassion fatigue). Three open-ended questions exploring experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic also were included: 1) What supportive resources are you using?; 2) What additional stressors are you facing?; and 3) Further comments/suggestions. These optional questions yielded open text responses varying from a few words to several sentences.

Study Context and Data Collection

Survey responses were collected from April 15 through April 30, 2020, prior to the anticipated peak of local COVID-19 cases at our academic medical center. Table 1 outlines the global, national, regional, and local COVID-19 context at the time of data collection. The RedCap® survey was sent via email to each academic, clinical, and research department in the health system, and also was published on an internal research message board and internal employee website. Survey completion was voluntary and anonymous. All employees at one large, academic medical center in the Midwest were invited to participate, including the hospital system, university, and physicians’ group with a total estimated population of 15,784 healthcare employees.

Table 1.

Timeline of national and local COVID-19 events (April 15 through April 30, 2020).

| Worldwide |

|---|

|

|

|

|

| National |

|

| Regional |

|

|

| Institutional |

|

| Contextual |

|

|

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS Version 24. Descriptive statistics were completed for variables related to participants’ demographics as well as scores on the three scales of the ProQOL. Pearson’s correlational matrix was completed to determine relationships between scores on the ProQOL scales. Single sample t-tests were used to compare ProQOL scores between those who had or had not cared directly for COVID positive patients. Exploratory analysis using ANOVA also tested for differences in ProQOL scores between most common professions in the sample.

Open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis to identify themes within the responses. Thematic analysis allows for the organization of data into patterns and themes that arise.24 Two team members conducted analysis of the qualitative data. After first completing an initial review of the responses, each research member reviewed and organized the data into individual codes. An individual’s response could have multiple codes if they provided unique items. From this, they reviewed codes, discussing similarities and discrepancies until they gained consensus. Themes were established by grouping similar codes and labeled based on the groupings, in some instances using exact descriptions as appropriate (i.e., “childcare”). They conducted an additional review of the data to refine code definitions further and ensure accurate coding.

RESULTS

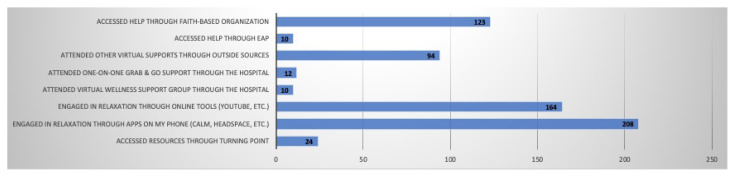

Respondents (n = 613) completed the survey from April 15 – April 30, 2020, which represents around 3.8% of the total health system employee population. Participants’ mean age was 42.72 years (SD = 11.62), A total of 76.6% of participants identified as female, and 82.2% identified as White/Caucasian. The mean years working in healthcare was 15.70 years (SD = 10.89, range of < 1 to 50 years). Participants represented over 25 professions/roles and more than 30 departments/ divisions within the medical center (Table 2, Figure 1). Notably, the survey link was sent out to the chairs or directors of 30 departments across the health system, and at least one survey response was received from each of these departments. Descriptive statistics for the types of coping strategies or resources used are summarized in Figure 2. across the health system, and at least one survey response was received from each of these departments. Descriptive statistics for the types of coping strategies or resources used are summarized in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Departments responding to the survey.

| Department Name | Percentile |

|---|---|

| Oncology/Hematology | 16.4 |

| Non-Clinical Other | 11.9 |

| Bone Marrow Transplant/Hematologic Malignancies and Cellular Therapeutics | 5.8 |

| Psychiatry and Behavioral Services | 5.5 |

| Clinical Other | 4.8 |

| Emergency | 4.1 |

| Radiation/Oncology | 3.7 |

| Case Management | 3.6 |

| Pharmacy | 3.6 |

| Plastic Surgery | 3.4 |

| Clinical Trials | 3.2 |

| Police/Safety/Parking | 3.2 |

| Respiratory Therapy | 3.1 |

| Family Medicine | 2.9 |

| Internal Medicine | 2.9 |

| Pathology | 2.7 |

| Patient Navigation | 2.7 |

| Neurology | 2.6 |

| Neurosurgery | 2.2 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 2.2 |

| Urology | 2.0 |

| Radiology | 1.7 |

| Clinical Nutrition | 1.5 |

| Cardiology/Cardiac Surgery | 1.0 |

| Orthopedics | 0.9 |

| Performance Excellence | 0.9 |

| Ophthalmology | 0.7 |

| Pediatrics | 0.7 |

| Population Health | 0.7 |

| Rehabilitation Medicine | 0.5 |

| Otolaryngology | 0.3 |

Figure 1.

Professions represented in sample.*

*Clinical Other includes: Behavioral Health Tech, Psychologist, Chaplin, Clinical Dietitian, Lab, Physical Therapy, Patient Scheduling; Non-Clinical Other includes: Compliance Auditor, Police/Security, Optimization Analyst

Figure 2.

Types of coping strategies or resources used by respondents (n = 305).

ProQOL Results

ProQOL results demonstrated that participants reported low levels of compassion fatigue and burnout, but moderate levels of compassion satisfaction (Table 3). No participants scored in the high range (defined by scores of 42+) for compassion fatigue or burnout, 36.04% of respondents scored in the moderate range for compassion fatigue, and 41.80% in the moderate range for burnout. Only five participants scored in the low range for Compassion Satisfaction, and 52.81% reported high compassion satisfaction.

Table 3.

ProQol results.

| Scale | Mean | SD | Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion fatigue | 21.54 | 5.67 | Low |

| Burnout | 22.27 | 5.43 | Low |

| Compassion satisfaction | 40.85 | 5.70 | Moderate |

Note: Range of scales is 10 to 44, with descriptors falling at 22 or lower indicating Low, 23 to 41 Moderate, and 42 or above noting High levels of the given construct.

Compassion satisfaction was significantly and negatively correlated with compassion fatigue (r = −0.217, p < 0.01), and burnout (r = −0.646, p < 0.01). Burnout and compassion fatigue were found to be significantly and positively correlated (r = −0.560, p < 0.01). Both clinical (66.4%) and non-clinical (33.6%) healthcare workers participated. At the time of the initial survey, only 15.8% of participants had provided direct care to a COVID-19 positive patient. There were no significant differences in compassion fatigue, burnout, or compassion satisfaction between those who had or had not provided this direct care to COVID-19 positive patients. Additionally, ProQOL scores were not found to be related significantly to participants’ ages or years working in healthcare. Compared to prior studies,25 the current study failed to demonstrate significant differences between nurses and physicians on ProQOL scores. However, clinical healthcare workers reported significantly higher compassion fatigue (F = 2.04, p < 0.05) compared to participants not involved in direct clinical service.

Open-ended Responses

Most participants (77.3%, n = 474) provided at least one open-ended response. There was no significant demographic or ProQOL score differences between open-ended responders and non-responders. Of the total 613 respondents, 44.8% (n = 275) reported what supportive resources they were using, 70% (n = 429) responded about additional stressors they faced, and 14.7% (n = 90) provided a comment or suggestion.

Thematic analysis identified significant themes for all three questions (Tables 4 – 6). The focus was on themes from the additional stressors questions that received the most responses (n = 429). Analysis identified five “additional stressors” themes that our sample faced during the initial weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic: 1) family; 2) financial sustainability and housing; 3) impact on personal health; 4) childcare; and 5) work. While not directly prompted, many respondents also described how they were negotiating and responding to these stressors.

Table 4.

Themes from open-ended responses: Other supportive resources used.

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Socializing with others | Virtual interactions with family and friends. |

| Exercise/diet | Exercising outdoors & taking advantage of online workouts at home. |

| Recreation/hobbies/ games | Reading, listening to music, watching foreign films, gardening, playing cards, cooking, sitting in the sun, furniture and art re-arranging and deep cleaning. |

| Faith/belief system | I use my faith and church resources we have available to us online. |

| Mental healthcare/counseling | I have a therapist and a couples therapist that have been extremely helpful during this time. |

| Meditation/relaxation | Readings on stillness, meditation, writing and reading the work of others. |

| News | …staying informed in the news and being pro-active. |

| Other | …relaxing at the end of the day with a glass of wine. |

Table 5.

Themes from open-ended responses: Additional stressors faced-domains and relevant quotes.

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Family | Mother-in-law passed away and my husband and I were not able to attend the funeral. Elderly father had pacemaker surgery during the crisis, and I was not able to be there to help as I normally would have. Other family members have jobs that put them at high risk of exposure. |

| Family: COVID-19 specific | Wife who is immunosuppressed and son with asthma, I do not want to bring the virus home to them. |

| Financial/ sustainability/ housing | I am the only one in my house working right now, and have become the sole provider for them, and my income alone is not enough. |

| Impact on health and health practice | Loss of sleep, headaches, back and shoulder pain, anxiety. |

| Childcare | My kids have to be homeschooled, so I divide my time at being a mom, homeschool teacher, and professional. |

| Work | …work stressors. Coming home and crying because all the changes at work are so hard to keep up with. And I’m afraid to get sick because of my patient numbers and if I don’t get patient numbers I can’t graduate. |

| Social impact | Missing face to face human contact. As socializing with friends. |

| No stressor | Absolutely none. Our lives have not changed at all. |

| Political stress | …the national government’s handling of the situation. Local (county, city and state, and work) government has been much better source of reliable information. |

| Training/education | I stress that I won’t be as good of a surgeon because COVID has robbed me of the majority of my senior surgical training experience, since elective cases have been cancelled. I stress that this will extend into my fellowship, which is only 1 year in length, and further rob me of my training after I have worked 12 years to get to this point in my training. I stress that the job market will be terrible in the coming few years, and that will affect me and my family significantly. |

| Other | All the unknowns of how this will impact us. |

Table 6.

Themes from open-ended responses: Comments and suggestions-domains and relevant quotes.

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Feedback regarding institution system and administration | The health system leadership has done a better job of open, honest, and transparent communication, but their tendency is to conceal information. I hope they have learned the importance of transparency, but I worry they will revert to concealment. |

| Workflow/adjusting to home | For me, working from home has actually decreased my work-related stress and my productivity has remained stable. I recognize this is in part personal preference and fortunate circumstances, but the fact that the university and my department has encouraged this and been supportive with IT help and weekly updates has been enormously comforting as well. |

| Need for mental health services and coping strategies | I need a therapist after this. It feels like the stress and anxiety are consuming my life. |

| Expressed appreciation for the study | This survey made me feel little better by just expressing how I feel! |

| Feedback on specific survey items | Though it may confound the data you’ve already collected, I would have appreciated more guidance on what “help” means, unless it was intentionally left that open to interpretation. |

| Concern for COVID-19 status | It would be nice to have antibody testing to check for immunity. It would be nice to have more tests for COVID-19 that are rapid. It would be nice to have reassurance that we have enough masks and gloves. It seems we have enough. |

| Other | A vocation to serve is deeply satisfying. The trauma/PTSD of truly caring for all around you from patients, colleagues, staff to family...are all one and the same. Stress of infecting my wife and likely death has made her stressed and I am the vector/risk factor...but will not stop serving others. |

Family

Roughly 173 (28.2%) participants commented on family- related stressors. Many respondents reported worry for family members who were at increased risk for COVID due to personal health reasons, as well as concern about potentially spreading the virus to family due to their jobs. Many other respondents expressed concerns about how family members were coping with how the pandemic was re-structuring life and daily routines. Family life transitions across the continuum were reported, including stress around infertility treatment disruptions, concerns about childbirth, illnesses, death, and funerals. A desire to ensure health and provide support for family and friends emerged as prominent in the data, illustrated by this response: “(concern for) wife who is immunosuppressed and son with asthma, I do not want to bring the virus home to them.”

Financial Sustainability and Housing

Participants (127, 20.7%) described broad concerns about financial stability due to potential lost wages within their family. Some noted that their partner had lost their job already or that they feared that this could be the case in the future. Additionally, some described facing with the prospect of moving and exploring new residence in the midst of the pandemic. The elements of “unknown” related to how the pandemic impacts their livelihood, was especially notable: “I am the only one in my house working right now, and have become the sole provider for them, and my income alone is not enough.”

Impact on Personal Health

One hundred and four participants (17%) described concern for how the pandemic impacts their own health, with particular concern about sleep. The impact on pre-existing mental health concerns, including anxiety and depression, were also of concern. Additionally, participants described concern for their own increased risk of contracting COVID due to exposure while at work: “I normally have some anxiety but feel my anxiety has hit its maximum. Hardly sleeping, isolation feels terrible, mourning the loss of my normal life, have the ability to work from home but having so much trouble with motivation with EVERYTHING. I’m depressed, worried and feel that life is a complete nightmare right now.”

Childcare and Homeschooling

While childcare certainly is related to family stressors, it was coded separately due to its frequency and specificity in the data. One hundred participants mentioned this stressor specifically. As schools and daycares closed, many participants had to manage new work-from-home and homeschooling responsibilities simultaneously, adding another element of stress. Limited resources available to help with childcare made this new reality especially challenging. Even for participants who retained their typical childcare arrangements, there was stress as they worried about whether they should send their children or keep them home due to various safety and cost concerns: “I’m a single parent, so I’m juggling extended days of working at home with homeschooling a kindergartner. I have no family or other resources to assist with her care. Her school is cancelled for the rest of the year and her summer program is not opening in June as planned.”

Work

For 83 participants, stress related to work was reported. Some reported stress around learning to work via telehealth or from home, and some expressed concern for the impact of these adjustments and the new threat of COVID-19 on their colleagues: “I feel that sometimes our staff is being cut to the bare minimum and that can make me a little uneasy. I sometimes feel that I do not have the support of extra coworkers to help with my stressful patient load.”

A Note on Grief

Respondents’ answers about additional stressors conveyed a high level of distress in some instances, and an overall theme of grief, that cut across all five reported themes. Participants articulated that they were grieving the loss of “important things that were planned”, grieving the inability to see a new grandchild or be with a sick relative, grieving the inability to grieve death of loved ones and patients, and grieving the obstacles to and an overall loss of “normalcy”.

DISCUSSION

The current COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every area of life. Those working in healthcare, in both clinical and non-clinical operations, serve vital roles in managing the welfare of society during this uniquely challenging time. The current study measured rates of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction19 among employees at a large academic medical center in the Midwest during the initial wave of COVID-19 cases in April 2020. The inclusion of three open-ended survey questions also allowed participants to describe personal aspects of stress and resilience.

Findings showed that the healthcare employees were experiencing moderate levels of compassion fatigue and burnout, and somewhat elevated levels of compassion satisfaction compared to prior research on nurses, emergency room physicians, primary care, and palliative care professionals.26–28 Our data suggested that even in the midst of the pandemic, healthcare employees were able to find a sense of value and meaning in the work they do, perhaps bolstered by the public’s emphasis of the “essential” or even “heroic” nature of their roles.29 Further analyses demonstrated that compassion satisfaction was correlated negatively with burnout and compassion fatigue, again indicating that it may serve as a protective factor. Of note, our study was conducted in the early weeks of the pandemic, and it is unclear whether and how this protective effect might shift through time as the pandemic continues.

Despite reporting somewhat moderate levels of problematic concerns related to their work via burnout and compassion fatigue, the 70% of healthcare employees who responded to our optional open-ended question about additional stressors described increased stress outside of the work setting. This suggested that while the ProQOL may aid in understanding the impact of work-related stress for those in healthcare and related fields, it may be insufficient at capturing the broader scope of stress that workers have experienced during the pandemic.

Additionally, the current study demonstrated a breadth of responses from employees across the academic health center, including groups that typically have not been reported in the compassion fatigue and burnout literature (i.e., EMR technicians, researchers).2 Like previous studies finding differences in fear and anxiety between clinical and non-clinical workers during COVID-19,7 our findings also showed higher levels of compassion fatigue for participants involved in direct patient care compared to non-clinical respondents. However, the fact that 70% of our sample responded to an optional question about additional stressors in their lives showed that the stress of COVID-19 was not limited to clinical workers but extended to the entire healthcare system. This emphasized the need to assess and address the stress impacting our healthcare workforce from a broad perspective, as the pandemic in particular has invaded both professional and personal areas of life. of our sample responded to an optional question about additional stressors in their lives showed that the stress of COVID-19 was not limited to clinical workers but extended to the entire healthcare system. This emphasized the need to assess and address the stress impacting our healthcare workforce from a broad perspective, as the pandemic in particular has invaded both professional and personal areas of life.

Our study had several limitations. Because our survey was available to all employees via our intranet, and additional emails were sent to department chairs to facilitate recruitment, we were unable to calculate an exact response rate, as we cannot know how many employees were aware of the study. However, our sample represented respondents from many different roles in the healthcare system. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of our study limited causal conclusions or the ability to report on how these measures were changing over time. Finally, the ProQOL is focused on aspects related to one’s role in work and may not capture the wider array of factors that contribute to stress for healthcare workers. Our data suggested that healthcare systems should assess for outside burdens that may impact employees’ well-being external to their daily work tasks.

Our study was the largest to-date examining burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among the healthcare workforce in the U.S. during COVID-19. Our data showed higher compassion satisfaction scores than prior research on a variety of healthcare professionals, 2,26–28 suggesting that early in the pandemic, respondents may have experienced protective effects from community and national support that encouraged these elevated levels. While encouraging, our study was conducted at an early point in the COVID-19 pandemic when local cases were relatively limited. As cases surge and the pandemic wears on, future research must prioritize and study the emotional well-being of our healthcare workforce.3,5 We urge healthcare systems to continue to monitor and support both the work and non-work-related stressors of their employees.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to each of the colleagues from our institution who took time to generously respond to this survey and share their experiences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L, Mijovic-Kondejewski J, Smith-MacDonald L. Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor WD, Blackford JU. Mental health treatment for front-line clinicians during and after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: A plea to the medical community. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):574–575. doi: 10.7326/M20-2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krystal JH. Responding to the hidden pandemic for healthcare workers: Stress. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):639. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewey C, Hingle S, Goelz E, Linzer M. Supporting clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):752–753. doi: 10.7326/M20-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedy JR, Shaw DL, Jarrell MP, Masters CR. Towards an understanding of the psychological impact of natural disasters: An application of the conservation resources stress model. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5(3):441–454. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makwana N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(10):3090–3095. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2485–2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter P, Deshields T, Divanbeigi J, et al. Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(5):E56–62. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.E56-E62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendenhall TJ. Trauma response teams: Inherent challenges and practical strategies in interdisciplinary fieldwork. Families, Systems & Health. 2006;24(3):357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyson J. Compassion fatigue in the treatment of combat-related trauma during wartime. Clin Soc Work J. 2007;35(3):183–192. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slocum-Gori S, Hemsworth D, Chan WWY, Carson A, Kazanjian A. Understanding compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliat Med. 2013;27(2):172–178. doi: 10.1177/0269216311431311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abendroth M, Flannery J. Predicting the risk of compassion fatigue: A study of hospice nurses. J Hospice Palliati Nurs. 2006;8(6):346–356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkema K, Linton JM, Davies R. A study of the relationship between self-care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout among hospice professionals. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2008;4(2):101–119. doi: 10.1080/15524250802353934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamm B. The Concise ProQOL Manual. 2010. [Accessed October 16, 2020]. http://proqol.org .

- 20.Ravelo J, Jerving S. COVID-19- A timeline of the coronavirus outbreak. [Accessed October 16, 2020]. https://www.devex.com/news/covid-19-a-timeline-of-the-coronavirus-outbreak-96396 .

- 21.University of Kansas Health System. Novel Coronavirus Update for Physicians and APPs. Kansas City, KS: University of Kansas Health System; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. [Accessed February 24, 2021]. https://health.mo.gov/living/healthcondiseases/communicable/novel-coronavirus/

- 23.Heritage B, Rees CS, Hegney DG. The ProQOL-21: A revised version of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale based on Rasch analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocker F, Joss N. Compassion fatigue among healthcare, emergency and community service workers: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(6):618. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13060618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Shafei DA, Abdelsalam AE, Hammam RAM, Elgohary H. Professional quality of life, wellness education, and coping strategies among emergency physicians. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(9):9040–9050. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samson T, Shvartzman P. Association between level of exposure to death and dying and professional quality of life among palliative care workers. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(4):442–451. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felsenthal E. Front Line Workers Tell Their Own Stories. Apr 9, 2020. [Accessed November 23, 2020]. https://time.com/collection/coronavirus-heroes/5816805/coronavirus-front-line-workers-issue/

- 30.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Apr 15, 2020. [Accessed December 4, 2020]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- 31.The White House. Proclamation on Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Apr 15, 2020. [Accessed December 4, 2020]. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/