Abstract

Rationale:

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a mortal clinical syndrome without effective therapies. We recently demonstrated in mice that a combination of metabolic and hypertensive stress recapitulates key features of human HFpEF.

Objective:

Using this novel preclinical HFpEF model, we set out to define and manipulate metabolic dysregulations occurring in HFpEF myocardium.

Methods and Results:

We observed impairment in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation associated with hyperacetylation of key enzymes in the pathway. Down-regulation of sirtuin 3 and deficiency of NAD+ secondary to an impaired NAD+ salvage pathway contribute to this mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation. Impaired expression of genes involved in NAD+ biosynthesis was confirmed in cardiac tissue from HFpEF patients. Supplementing HFpEF mice with nicotinamide riboside or a direct activator of NAD+ biosynthesis led to improvement in mitochondrial function and amelioration of the HFpEF phenotype.

Conclusions:

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that HFpEF is associated with myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction and unveil NAD+ repletion as a promising therapeutic approach in the syndrome.

Keywords: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, mitochondria, acetylation, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, Metabolic Syndrome, Remodeling

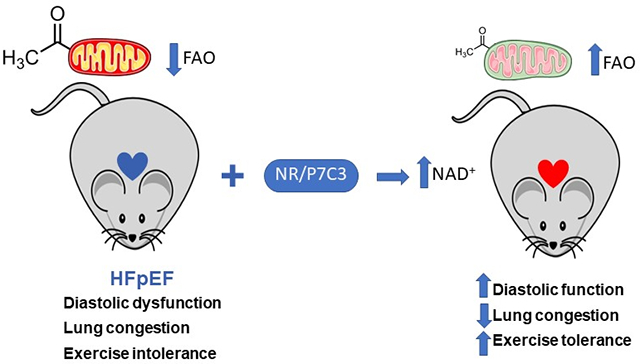

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) accounts for ≈50% of all HF and is associated with morbidity and mortality comparable to HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)1, 2. At present, there are no evidence-based therapies with demonstrated efficacy in HFpEF2. Commonly coexisting with other metabolic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, HFpEF is considered the cardiac manifestation of a systemic metabolic disturbance3. However, little is known regarding underlying mechanisms.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of metabolic disorders. Therefore, we hypothesized that myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to HFpEF pathogenesis and ameliorating those defects is a therapeutic strategy with potential clinical impact. In the present study, we tested this hypothesis using a novel “two hit” murine model of HFpEF in which concomitant metabolic and hypertensive stress elicited by HFD coupled with inhibition of constitutive nitric oxide synthases (NOS) with L-NAME (N[w]-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester) recapitulates the numerous and myriad features of human HFpEF4.

METHODS

Data Availability.

The authors will make their data, analytic methods, and study materials available to other researchers based on reasonable request.

HFpEF experimental model.

The mouse HFpEF model was established as described previously4. All experiments involving animals conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication 8th edition, update 2011) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas. All studies were in compliance with ethical regulations. C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Only male adult (8 -10 week old) mice were used in the experiments as our recent work demonstrated that female mice are less susceptible to HFD+L-NAME treatment5. Mice were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle from 6 AM to 6 PM and had unrestricted access to food (#2916, Teklad and D12492, Research Diet Inc. for the CHOW and HFD groups, respectively) and water. N[w]-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; 0.5 g/L, Sigma Aldrich) was supplied in the drinking water for the indicated periods of time, after adjusting the pH to 7.4. For treatment, nicotinamide riboside (NR, Chromadex) (400 mg/kg body weight/d) was added to the mouse diet6, and the food was exchanged twice per week. P7C3-A20 (MedChemExpress HY-15978) was dissolved in DMSO initially and then diluted with sterile sesame oil (Sigma Aldrich) and injected daily (1 mg/kg body weight/d) via an intraperitoneal route (5 d per week for 4 weeks)7.

Sirtuin3 (Sirt3) floxed mice (Sirt3fl/fl) were crossed with αMHC Cre mice. Mouse genotypes were confirmed by PCR. Tissue-specific deletion of Sirt3 was confirmed by Western Blot. Cardiomyocyte-specific Sirt3 knockout (KO) mice (αCre;Sirt3fl/fl), and control groups (αCre mice and Sirt3fl/fl mice) were subjected to the same HFpEF treatment (HFD+L-NAME) as described above.

Conventional echocardiography and Doppler imaging.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a VisualSonics Vevo 2100 system equipped with MS400 transducer (Visual Sonics Inc)4. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and other indices of systolic function were obtained from short axis M-mode scans at the mid-ventricular level, as indicated by the presence of papillary muscles, in conscious, gently restrained mice. Apical 4-chamber views were used in anesthetized mice to obtain diastolic function measurements using pulsed-wave and tissue Doppler at the level of mitral valve. Anesthesia was induced by 5% isoflurane and confirmed by lack of response to firm pressure on one of the hind paws. During echocardiogram acquisition under body temperature-controlled conditions, isoflurane was reduced to 1.0-1.5% and adjusted to maintain heart rate in the range of 400-500 beats per min. Parameters collected include: heart rate (HR), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVID,d), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVID,s), end-diastolic interventricular septal wall thickness (IVS,d), left ventricular end-diastolic posterior wall (LVPW,d), left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), peak Doppler blood inflow velocity across the mitral valve during early diastole (E), peak Doppler blood inflow velocity across the mitral valve during late diastole (A), and peak tissue Doppler of myocardial relaxation velocity at the mitral valve annulus during early diastole (E’). At the end of the procedures all mice recovered from anesthesia without difficulty. All parameters were measured at least 3 times, and averages are presented.

Tail cuff blood pressure recordings.

Systolic blood pressure was measured noninvasively in conscious mice using the tail-cuff method and a CODA instrument (Kent Scientific)4. Animals were placed in individual holders on a temperature-controlled platform (37°C), and recordings were performed under steady-state conditions. Before testing, all mice were trained to become accustomed to short-term restraint. Blood pressure was recorded for at least 4 consecutive days and readings were averaged from at least 8 measurements per session.

Exercise exhaustion test.

After 3 days of acclimatization to treadmill exercise, an exhaustion test was performed4. Animals ran uphill (20°) on a treadmill (Columbus Instruments) starting at a warm-up speed of 5 m/min for 4 min after which time speed was increased to 14 m/min for 2 min. Every subsequent 2 min, the speed was increased by 2 m/min until the animal was exhausted. Exhaustion was defined as inability of the animal to return to running within 10 s of direct contact with an electric-stimulus grid. Running time was measured and running distance calculated.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests were performed by injection of glucose (2 g/kg in saline) after 6-hour fasting. Tail blood glucose levels [mg/dL] were measured with a glucometer before (0 min) and at 15, 30, 45, 60 and 120 min after glucose administration.

Isolation of adult mouse ventricular myocytes (AMVMs).

AMVMs were isolated as described previously4. Briefly, hearts were retrogradely perfused with perfusion medium (PM) (123 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM Na2HPO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM HEPES, 22 mM NaHCO3, 30 mM taurine, 10 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime, and 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4) for 2 min (2-4 ml/min) and then switched to PM supplemented with 0.025 mg/mL Liberase TM (Roche) and 0.025% trypsin for 15 min. After digestion, ventricles were dissected and mechanically dissociated in PM using forceps and pipetting. Cell yield was approximately 90% viable, and only quiescent cardiomyocytes with clear and defined striations were used in this study. Cells were used immediately for experiments.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Mouse hearts were retrogradely fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer, embedded in 2% agarose, post-fixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide and stained in 2% uranyl acetate, dehydrated with an ethanol graded series and embedded in EMbed-812 resin as described previously8. Thin sections were cut on an ultramicrotome and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images were acquired on a FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit electron microscope equipped with a LaB6 source and operating at 120 kV. Mitochondrial cross-sectional areas were traced and measured using the Multi-Measure ROI tool in ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Mitochondrial density was assessed by counting the number of mitochondria versus sarcomeres in a given field.

Isolation of cardiac mitochondria.

Immediately following euthanasia, hearts were excised and homogenized in ice-cold isolation buffer (10 mM MOPS, 1.0 mM EDTA, 210 mM mannitol, and 70 mM sucrose, pH 7.4) using a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2000 rpm (5 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was filtered through cheese cloth. The mitochondrial pellet was obtained by centrifugation of the supernatant at 10,000 rpm for 10 min (4°C)9. Mitochondria were resuspended in homogenization buffer at a final concentration of 20 mg/mL. Protein determinations were made using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (Pierce) with BSA as standard.

Analysis of mitochondrial respiratory function.

Oxygen consumption was measured using a fluorescence-based oxygen sensor (NeoFox, Ocean Optic) connected to a phase measurement system from the same company. The sensor was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described8. AMVMs were isolated by enzymatic digestion. Cell numbers were counted using a hemocytometer. Only cells with sharp borders and clear striations were selected. Briefly, 1x104 cardiomyocytes were incubated in a solution containing KMES 60 mM, MgCl2 23 mM, KH2PO4 10 mM, Hepes 20 mM, taurine 20 mM, mannitol 110 mM, EGTA 0.5 mM, and DTT 0.3 mM (pH 7.1) at 4°C, and permeabilized with saponin (50 ng/mL) for 5 min before substrates were added. To measure complex I-mediated OCR, glutamate (10 mM) and malate (5 mM) were added. State 3 respiration was activated by adding ADP (2.5 mM), whereas state 4o respiration was measured after adding oligomycin (1 μM). For complex II-mediated OCR, 5 mM succinate was added. To measure pyruvate- or palmitoylcarnitine-mediated OCR, 0.1 mM pyruvate or 25 μM palmitoylcarnitine was added to each experiment10. For isolated mitochondria, mitochondria were diluted to 0.25 mg/mL in 10 mM MOPS, 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, and 5.0 mM K2HPO4 at pH 7.4 containing respiratory substrates (25 μM palmitoylcarnitine or 0.1 mM pyruvate or 10 mM glutamate, 1 mM malate) as indicated. State 3 respiration was initiated by addition of ADP at a final concentration of 0.25 mM, and state 4 was measured after ADP exhaustion.

Evaluation of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity.

Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase was measured as described previously11. Briefly, mitochondria were diluted in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM MOPS, 1.0 mM EDTA at pH 7.2) to a final protein concentration of 1 mg/mL, and sonicated on ice (3 passes of 3s each) using an ultrasonic dismembrator set at 30% maximal power (Fisher Scientific model 100). 20 μg of mitochondrial protein was added to buffer containing 20 mM MOPS, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 200 μM ferriceneum hexafluorophosphate (Fc+PF6) at pH 7.2. Reduction of Fc+PF6 to the corresponding neutral ferrocene derivative by the active enzyme resulted in decreased absorbance at 300 nm upon addition of palmitoylCoA or octanoylCoA (100 μM). The rate of Fc+PF6 reduction was negligible in the absence of acyl-CoA substrate.

Evaluation of PDH activity.

Mitochondria were incubated under specified respiratory conditions at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL for indicated times. Mitochondria were then diluted to 0.05 mg/mL in buffer containing 25 mM MOPS and 0.05% Triton X-100 at pH 7.4. Solubilization of mitochondria with 0.05% Triton X-100 inhibits complex I of the respiratory chain preventing consumption of NADH. PDH activity was measured spectrophotometrically (Agilent, 8452A) as the rate of NAD+ reduction to NADH (340 nm, e = 6,200 M−1cm−1) upon addition of 2.5 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mM CoASH, 0.2 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1.0 mM NAD+, and 5.0 mM MgCl2 at pH 7.49.

Immunoprecipitation (IP).

Cardiac mitochondria were lysed in RIPA buffer and further diluted by IP buffer (0.02% Triton X100 in phosphate-buffered saline). IP buffer pre-washed acetyl-lysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Immunechem, ICP0388) were incubated with the cleared lysate (4°C overnight) with gentle agitation. Agarose bound with acetylated proteins was washed gently with IP buffer three times by centrifugation. Bound acetylated proteins were released by SDS loading buffer (5 min, 95°C). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Measurement of myocardial NAD+ levels.

Cardiac tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and tissue NAD+ and NADH levels were measured using a commercial kit (BioAssay System, E2ND-100).

RNA isolation and qPCR.

Total RNA was extracted from murine hearts using TRIzol reagent and Quick-RNA™ MicroPrep kit (Zymo Reaserch). A total of 500 ng RNA was used for reverse transcription using iScript reagent (Bio-Rad). qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate with SYBR master mix (Bio-Rad). Cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C (30 sec) followed by 40 cycles at 95°C (5 sec) for denaturation and 60°C (15 sec) for annealing/extension. Following the cycling stage, DNA melt curve analysis was carried out to verify amplification specificity (95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 minute and 95°C for 15 sec).

For human hearts, total RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Real time PCR was performed in duplicate using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay probes with specific primers for target sequences. The delta-delta Ct (2 ΔΔCT) relative quantification method, using 18S or GAPDH for normalization, was used to estimate the amount of target mRNA in samples, and fold ratios were calculated relative to mRNA expression levels from control samples. The following PCR primer sequences were used (forward, reverse):

18S-mouse (AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG, CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA);

Nampt-mouse (TGGCCTTGGGGTTAATGTGT, TAACAAAGTTCCCCGCTGGT)

Nmnat1-mouse (GTGCCCAACTTGTGGAAGAT, CAGCACATCGGACTCGTAGA)

Nmnat2-mouse (CCGTCTCATCATGTGTCAGC, ACACACTGCAGGTTGTCTGC)

Nmnat3-mouse (AGTGGATGGAAACGGTGAAG, GAGGCTGATGGTGTCTTGCT)

Nampt-human (TGGCCTTGGGATTAACGTCTT, AACAAAATTCCCTGCTGGCG)

GAPDH-human (TCAACGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA, GCTGGTGGTCCAGGGGTCTTACT)

Immunoblot analysis.

Protein extracts from frozen mouse hearts were prepared by lysis in ice-cold modified RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 1% Triton-X 100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4%-20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. An Odyssey scanner (LI-COR version 3.0) was used as detection system. Protein expression was quantified using LI-COR ImageStudioLite software. Proteins were detected with the following primary antibodies: Cell Signaling - acetylated lysine (9441), Sirt1 (9475), Sirt3 (5490); Proteintech - LCAD (17526-1-AP), MCAD (55210-1-AP), VDAC (10866-1-AP), GCN5L1 (19687-1-AP); Abcam – HADHA (ab54477), ETC complex cocktail (CAD735); GeneTex – VLCAD (GTX114232); Millipore - PDH-E1α (ABS2082), PDHE1α pSerine 232 (AP1063), pSerine300 (AP1064) , pSerine293 (AP1062); Santa-cruz – Tom20 (sc-17764); Trevigen – polyPARylation (4336-APC); Fitzgerald - GAPDH (10R-G109a). PDK4 antibody is a customized antibody from Dr. Luke Szweda’s laboratory as reported previously9.

Human myocardial tissue.

Human myocardial tissue samples were collected under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Johns Hopkins University (Maryland, USA) and consent for biopsy procedures or use of explanted tissues prospectively obtained in all cases. HFpEF patients were referred for cardiac catheterization and right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy due to clinical suspicion of infiltrative cardiomyopathy. HFrEF samples were obtained from the right ventricular septum of explanted dilated failing hearts prior to orthotopic heart transplantation. Control samples were obtained from the right ventricular septum of nonfailing, explanted unused donor hearts. Control and HFrEF samples were provided by collaborators at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) through an IRB-approved protocol.

Statistical analysis.

Values are shown as mean ±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism v8. Data normality was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test (with α=0.05) and by visual inspection of normal Q-Q plots to ensure that there were no significant deviations from normality. For normally distributed data, the Student’s t-test (unpaired two-tailed) was used for two-group analysis. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used for multiple group analysis, and two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used for analysis of experiments with two independent variables. For non-normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney test was used for two-group analysis, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used for multiple-group analysis.

A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. No additional corrections for multiple testing were made across experiments. No statistical analyses were used to predetermine sample sizes; estimates were made based on our previous experience, experimental approach, and availability and feasibility required to obtain statistically significant results. Experimental animals were randomly assigned to each experimental/control group. No animals were excluded from the analysis. All possible pairwise comparisons were performed. All p values are raw. Investigators were blinded to the genotypes of the individual animals during the experiments and outcome assessments. When representative images are shown, the selected images are those that most accurately represent the average data obtained in all the samples.

RESULTS

Impaired Mitochondrial Function in HFpEF Myocardium.

Consistent with our previous report4, 5 weeks of exposure to HFD plus L-NAME triggered obesity, glucose intolerance, and hypertension (Online Figure IA–D). In the heart, we observed hallmark features of HFpEF, including left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), diastolic dysfunction, each coupled with clinical manifestations of HF, including exercise intolerance and lung congestion (Online Figure IF–I), whereas left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) remained preserved (Online Figure IE). To simplify nomenclature, we refer to these mice henceforth as “HFpEF mice”.

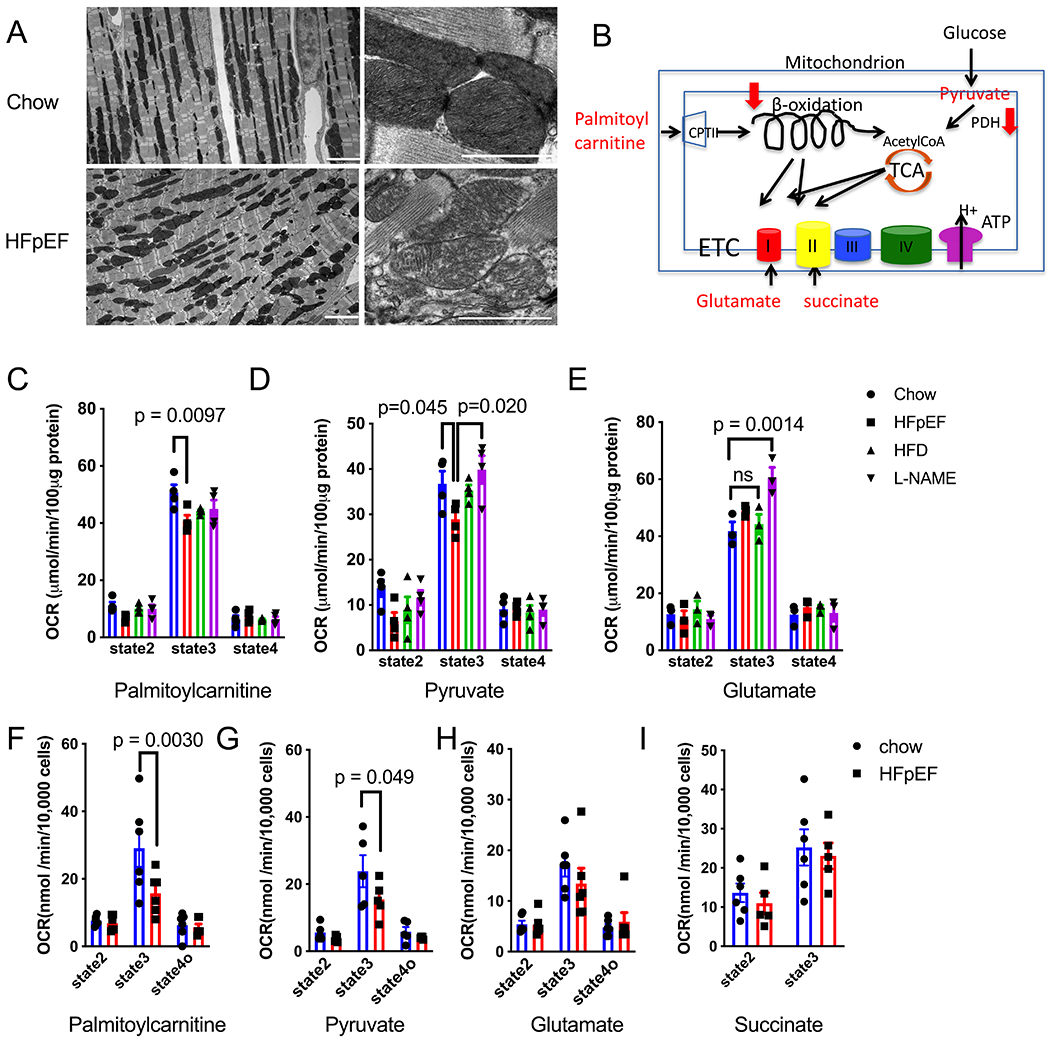

Electron microscopic analysis revealed striking mitochondrial morphological changes in the cardiac tissue of HFpEF mice. Whereas myofibrillar structures were grossly normal, mitochondria in HFpEF myocardium are misaligned and segmented (Figure 1A, Online Figure IJ&K) as compared with normal chow-fed mouse heart. Furthermore, the mitochondrial cristae appeared swollen (Figure 1A), indicating possible mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial Morphological and Functional Changes in HFpEF Hearts.

(A) Representative electron microscopy images of cardiac tissue isolated from control and HFpEF mice. Scale bar = 1 μm.

(B) Schematized image depicting mitochondrial metabolic pathways.

(C) Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) of isolated mitochondria exposed to palmitoylcarnitine as substrate. State 2 is the basal level, state 3 is the maximal level after adding ADP, and state 4 is the level after ADP exhaustion. N=4 mice in each group.

(D) OCR of isolated mitochondria exposed to pyruvate as substrate. State 2 is the basal level, state 3 is the maximal level after adding ADP, and state 4 is the level after ADP exhaustion. N=4 mice in each group.

(E) OCR of isolated mitochondria exposed to glutamate as substrate. State 2 is the basal level, state 3 is the maximal level after adding ADP, and state 4 is the level after ADP exhaustion. N=4 mice in each group.

(F) OCR of permeabilized adult mouse ventricular myocytes (AMVM) exposed to palmitoylcarnitine as substrate. State 4o is the level after adding oligomycin 1μM. N=6 mice in each group. Each point is the average of 2 experiments from each mouse.

(G) OCR of permeabilized AMVM exposed to pyruvate as substrate. State 4o is the level after adding oligomycin 1μM. N=5 mice in each group. Each point is the average of 2 experiments from each mouse.

(H) OCR of permeabilized AMVM exposed to glutamate as substrate. State 4o is the level after adding oligomycin 1μM. N= 6 mice in each group. Each point is the average of 2 experiments from each mouse.

(I) OCR of permeabilized AMVM exposed to succinate as substrate. State 4o is the level after adding oligomycin 1μM. N=6 mice in chow group, and N= 5 in HFpEF group

Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test for all experiments.

To test for specific defects in mitochondrial function, we measured oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in response to different substrates in freshly isolated mitochondria (Figure 1B). Despite lack of obvious change in glutamate-initiated complex I respiration, both palmitoylcarnitine- and pyruvate-initiated respiration were reduced in mitochondria isolated from HFpEF mouse hearts, as compared with control groups (mice fed normal Chow, HFD only, or exposed to L-NAME only) (Figure 1C–E). To confirm these findings and obviate possible artifactual over-representation of certain mitochondrial subgroups during isolation, we measured OCR in freshly isolated, saponin-permeabilized, adult mouse cardiomyocytes. The results confirmed that both glutamate-initiated complex I and succinate-initiated complex II respirations were unchanged in HFpEF hearts (Figure 1H,I), suggesting normal tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and electron transport chain (ETC) function (Figure 1B). This is consistent with unaltered steady state levels of ETC complex proteins (Online Figure IIA) and NADH dehydrogenase activity (Online Figure IIB). However, consistent with our findings in isolated mitochondria, both palmitoylcarnitine- and pyruvate-initiated respiration were significantly reduced in cardiomyocytes isolated from HFpEF mice (Figure 1F,G), suggesting defects in upstream pyruvate and fatty acid metabolism (Figure 1B).

Increased PDK4 Activity and Suppressed PDH Activity.

Consistent with previous reports that HFD is associated with suppressed pyruvate oxidation in the heart9, we observed that pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) was significantly upregulated in mice fed with HFD (both HFpEF and HFD-only groups) (Online Figure IIE,F). This, in turn, led to hyperphosphorylation and suppressed activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (Online Figure IIE,G,H), the rate-limiting enzyme in pyruvate oxidation. These data are not unexpected and are in agreement with inhibition of pyruvate metabolism detected by OCR.

Protein Hyperacetylation-mediated FAO Suppression.

Our observation that palmitoylcarnitine-initiated respiration was suppressed in HFpEF cardiomyocytes suggested a defect in FAO capacity. Of note, we did not observe significant changes in the protein abundance of key enzymes involved in FAO (Online Figure IIC, D), including very long-, long-, and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD, LCAD and MCAD, respectively), as well as trifunctional enzyme subunit α (HADHA). In contrast, direct measurement of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACAD) activity revealed a significant defect in the oxidization of 16-carbon chain palmitoylCoA (Figure 2A), and a trend in 8-carbon chain octanoylCoA (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Protein Hyperacetylation-mediated FAO Suppression.

(A) ACAD activity using C16 palmitoylCoA as substrate. Values were normalized to the Chow group. N=4 tests from 4 mice in each group. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

(B) ACAD activity using C8 OctanoylCoA as substrate. Values were normalized to the Chow group. N=4 tests from 4 mice in each group. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

(C) Immunoblot image of acetylated proteins in the mitochondrial fraction isolated from left ventricle (LV) of control and HFpEF mice. Tom20 was used as loading controls.

(D) Densitometric analysis ratio between total acetylated protein and Tom20. Values were normalized to the Chow group. N= 6 tests from 6 mice in each group. Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Immunoblot image of acetylated proteins in the mitochondrial fraction isolated from left ventricle (LV) of control, HFpEF, HFD alone, and L-NAME alone mice. VDAC was used as loading controls.

(F) Densitometric analysis ratio between total acetylated protein and VDAC. Values were normalized to the Chow group. N=8 mice in chow and HFpEF groups, and N=4 for HFD and L-NAME groups. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test

(G) Representative image of immunoprecipitate using anti-acetylated lysine antibody and probed with anti-VLCAD, HADHA and VDAC antibodies.

(H) Ratio of acetylated protein to total protein. N=4 tests from 4 mice for each group. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test

Post-translational modifications, especially acetylation, play an important role in regulating mitochondrial enzyme activities12. Hyperacetylation has been linked with decreased enzymatic activities of multiple mitochondrial proteins13. Using an anti-acetylated lysine antibody, we detected significantly increased acetylation of mitochondrial proteins in HFpEF hearts (Figure 2C–F). This was confirmed in whole heart lysates (Online Figure IIIA,B) and in lysates isolated from adult cardiomyocytes (Online Figure IIIC,D), indicating that this modification exists within myocardial mitochondria. By immunoprecipitation, we found that both VLCAD and HADHA are hyperacetylated in HFpEF myocardium, as compared with controls (Figure 2G,H). These data reveal that the decrease in FAO in HFpEF-derived cardiomyocytes occurs in association with increased protein acetylation of VLCAD and HADHA.

Impaired Sirt3 Expression and NAD+ Bioavailability in HFpEF Hearts.

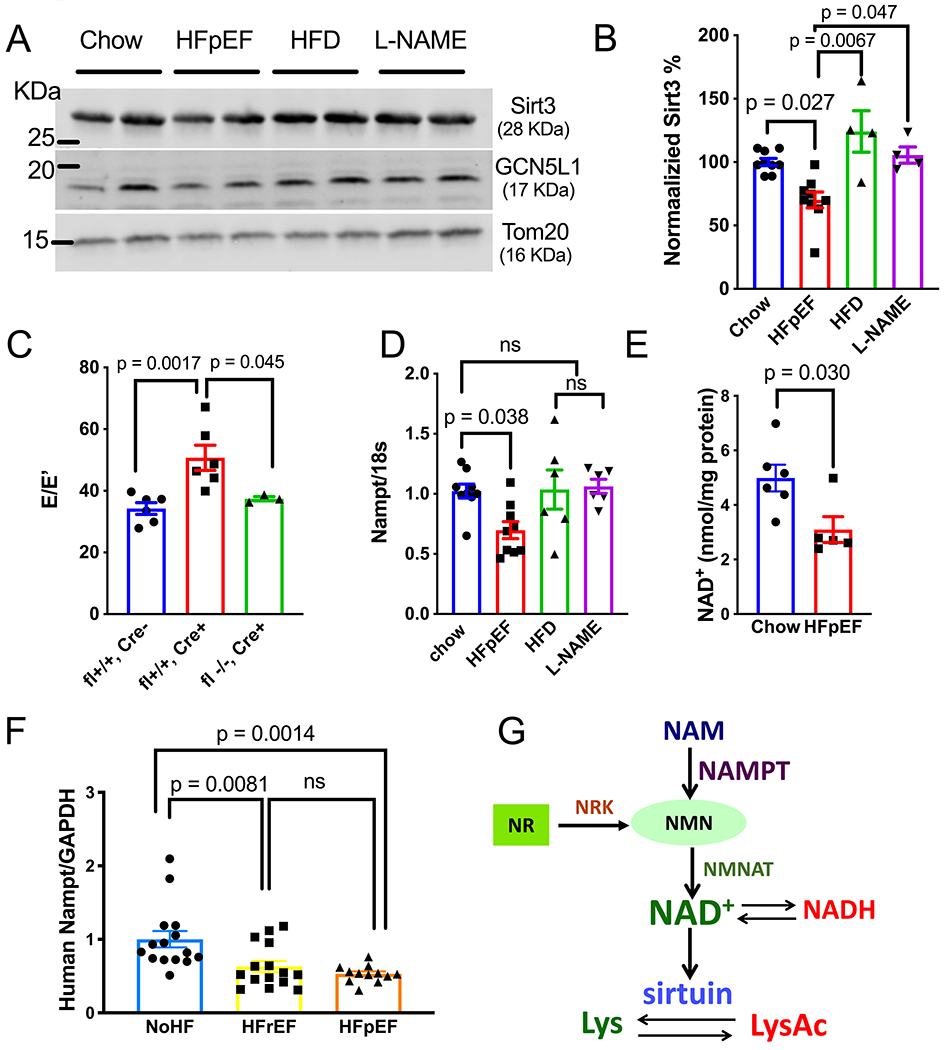

VLCAD and HADHA are known targets of sirtuin 3 (Sirt3)14, 15, a key mitochondrial deacetylase that plays a critical role in regulating mitochondrial protein acetylation levels16. In HFpEF hearts, we detected a significant reduction in the steady state levels of Sirt3 (Figure 3A,B). In contrast, no change in the steady state levels of GCN5L1 (General Control of amino acid synthesis 5-Like 1), the key mitochondrial protein acetylase, was observed (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3. Impaired Sirt3 Levels and NAD+ Bioavailability in HFpEF Hearts.

(A) Representative immunoblot image of Sirt3, GCN5L1 and Tom20 protein abundance in mitochondria fraction isolated from LV tissue of control, HFpEF, HFD alone, and L-NAME alone mice.

(B) Densitometric analysis ratio between Sirt3 and Tom20. Values were normalized to the Chow group. N=9 mice in chow and HFpEF groups, and N=4 for HFD and L-NAME groups. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test

(C) E/E’ measured by tissue Doppler echocardiography in Sirt3 fl+/+, αMHC Cre-(Flox mice), Sirt3 fl+/+, αMHC Cre+ (KO mice), and Sirt3 fl−/−, αMHC Cre+ (Cre mice) fed by HFD+L-NAME for 7-8 weeks. N = 6, 6, and 3 mice in each group. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test

(D) Nampt mRNA level in LV tissue of control, HFpEF, HFD alone, and L-NAME alone mice, normalized to 18s. N=9 mice in chow and HFpEF groups, and =6 for HFD and L-NAME groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(E) NAD+ level in LV tissue of control and HFpEF mice. N=6 and 5 in control and HFpEF group. Mann-Whitney test.

(F) mRNA levels of Nampt in human myocardial biopsies from non-failing (NoHF), HFrEF and HFpEF subjects. N=15 subjects each in nonHF and HFrEF group, n=12 subjects in HFpEF group). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(G) Schematic depicting the NAD+ salvage pathway and its relationship with sirtuins.

To further assess the role of Sirt3 in HFpEF pathogenesis, we subjected cardiomyocyte-restricted Sirt3 KO mice to HFpEF treatment (Online Figure IVA,B,C). We observed that Sirt3 KO mice (αMHC-Cre; Sirt3fl/fl) developed more pronounced diastolic dysfunction as demonstrated by tissue Doppler analysis of mitral inflow (E/E’) when compared with control mice (αMHC-Cre mice and Sirt3fl/fl mice) (Figure 3C, Online Table II), suggesting a protective effect of cardiomyocyte Sirt3 in HFpEF pathogenesis. Interestingly, we observed no significant changes in LV hypertrophy across these mouse lines (Online Figure IVD).

Activities of sirtuin enzymes are dependent on the required co-substrate NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), and impaired NAD+ bioavailability has been reported in a variety of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases17, 18. As cardiac NAD+ is mainly produced via the salvage pathway17 (Figure 3G), we evaluated the abundance of Nampt (nicotinamide phosphoribo-syltransferase), the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway. We found that Nampt transcript was significantly decreased in HFpEF hearts as compared with control groups (Figure 3D), whereas the mRNA of Nmnat (nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase), another key enzyme, remained unchanged (Online Figure IVE). Consistent with this, we observed a significant reduction in NAD+ levels (Figure 3E) in HFpEF heart, likely contributing to suppressed Sirt3 activities.

To test for human relevance, we turned to endomyocardial biopsies of control and failing human hearts (Online Table I). Strikingly, and in accordance with our observations in HFpEF mice, Nampt transcript was also reduced in human HFpEF hearts as compared with controls (Figure 3F). Similar suppression of Nampt was observed in samples from HFrEF patients, as well. These data suggest that impaired NAD+ homeostasis is a common feature of both subtypes of heart failure and could potentially serve as a shared therapeutic target.

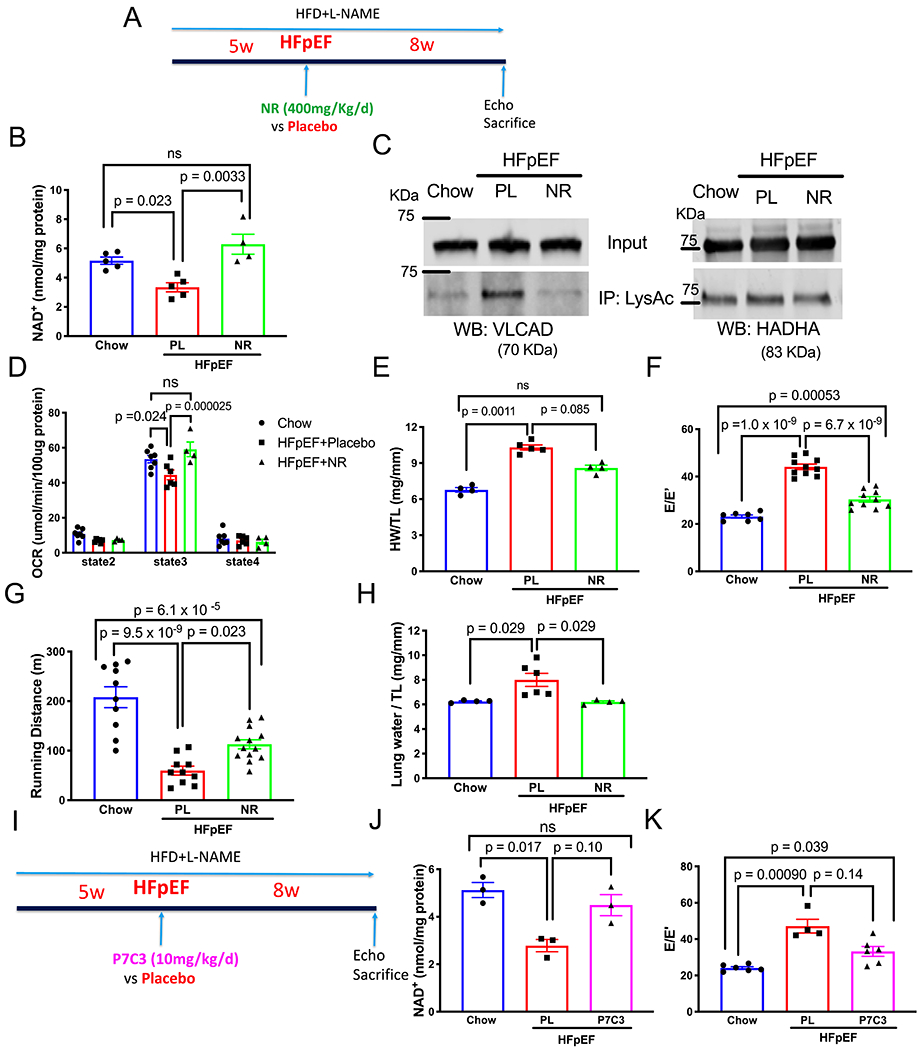

NAD+ Repletion Improved Mitochondrial Function and Reversed HFpEF Phenotype.

Our data reveal an increase in the acetylation of key FAO enzymes in HFpEF heart that may be driven, in part, by a deficit in NAD+. Studies have shown that oral supplementation of nicotinamide riboside (NR), a NAD+ precursor, boosts tissue NAD+ levels in both rodents and humans6, 19. In light of this, we tested whether oral NR could correct the NAD+ deficiency and improve mitochondrial function in HFpEF hearts. Remarkably, after full development of HFpEF (5 weeks of HFD+L-NAME), 8 weeks of NR supplementation (Figure 4A) ameliorated NAD+ deficiency (Figure 4B), and reversed hyperacetylation of VLCAD (Figure 4C, Online Figure VF) in animals maintained on HFpEF treatment. This was associated with recovery of mitochondrial function as demonstrated by improved palmitoylcarnitine-mediated OCR (Figure 4D). Notably, NR supplementation had no effect on total mitochondrial protein acetylation level, nor Sirt3 or Sirt1 expression (Online Figure VA,B). We did not observe significant changes in pyruvate oxidation either, as shown by persistent up-regulation of PDK4 and suppressed pyruvate-mediated OCR in both NR- and placebo-treated groups (Online Figure VC–E).

Figure 4. NAD+ Repletion Improved Mitochondrial Function and Reversed HFpEF Phenotype.

(A) Schematic depicting the experimental design of nicotinamide riboside (NR) vs placebo treatment.

(B) NAD+ level in LV tissue of control mice (Chow), HFpEF mice treated with placebo (HFpEF+Pl) vs NR (HFpEF+NR). N= 5, 5, 4 mice in each group, respectively. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

(C) Representative image of immunoprecipitate using anti-acetylated lysine antibody and probed with anti-VLCAD and HADHA antibodies.

(D) OCR of isolated mitochondria using palmitoylcarnitine as substrate from control mice, HFpEF mice treated with placebo vs NR. N=7,6, 4 mice for each group. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

(E) Ratio of heart weight (HW) to tibia length (TL) from control mice, HFpEF mice treated with placebo vs NR. N = 4, 5, 4 in each group. Results of Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test depicted in figure (results of one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: Chow vs HFpEF+Pl, p=9.0x10−7; HFpEF+Pl vs HFpEF+NR, p=0.00052; Chow vs HFpEF+NR, p=0.00046).

(F) Ratio between mitral E wave and E’ wave (E/E’). N = 7, 10, 10 mice in each group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(G) Running distance during exercise exhaustion test. N = 10, 10, 13 mice per group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(H) Ratio between lung water (subtraction between wet and dry lung weight) and TL. N= 4, 6, 4 mice per group. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

(I) Schematic depicting the experimental design of P7C3-A20 vs placebo treatment.

(J) NAD+ level in LV tissue of control mice (Chow), HFpEF mice treated with placebo (HFpEF+Pl) vs P7C3-A20 (HFpEF+P7C3). N=3 from 3 mice in each group. Results of Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test depicted in figure (results of one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: Chow vs HFpEF+Pl, p=0.0074; HFpEF+Pl vs HFpEF+P7C3, p 0.031; Chow vs HFpEF+P7C3, p=0.45).

(K) Ratio between mitral E wave and E’ wave (E/E’). N = 6,4,6 mice per group. Results of Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test depicted in figure (results of one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: Chow vs HFpEF+Pl, p=6.8x10−5; HFpEF+Pl vs HFpEF+P7C3, p=0.0053; Chow vs HFpEF+P7C3, p=0.036).

We next evaluated the functional effects of restored FAO in these HFpEF hearts. Phenotypically, we found that HFpEF mice fed NR manifested ameliorated cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 4E), attenuated diastolic dysfunction (Figure 4F), improved exercise capacity (Figure 4G), and reduced lung congestion (Figure 4H) without impacting LVEF (online Figure VIG). Taken together, these data demonstrate that oral NR supplementation corrected cardiac NAD+ deficiency, restored mitochondrial function, improved pathological cardiac remodeling, and ameliorated signs and functional manifestations of HFpEF in this preclinical model.

As HFpEF is a systemic syndrome, we also monitored for non-cardiac effects of NR supplementation. HFpEF mice fed NR exhibited normal food intake and remained obese and hypertensive (Online Figure VIA–D). However, they manifested a trend toward improved glucose tolerance profiles (Online Figure VIE,F), consistent with previously reported protective effects of NR on diabetes20.

To confirm the direct causal link between NAD+ homeostasis and HFpEF, we tested the therapeutic effect of P7C3-A20, a Nampt activator21 (Figure 4I). Whereas four-week treatment with P7C3-A20 had no impact on body weight and insulin sensitivity (Online Figure VIIA–C), P7C3-A20 restored cardiac NAD+ levels and attenuated diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF hearts (Figure 4J,K, Online Figure VIID,E), supporting the notion that NAD+ repletion yields therapeutic benefit in HFpEF.

DISCUSSION

Mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic remodeling play important roles in HFrEF22. However, little is known about mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in HFpEF. Using a novel murine model we recently developed that recapitulates the myriad features of human HFpEF4, we observed morphological changes in mitochondrial ultrastructure similar to those reported in heart tissue obtained from HFpEF patients23. Using this model, we have unveiled molecular changes in myocardial mitochondria that may contribute to HFpEF pathogenesis. Furthermore, we were able to mitigate the mitochondrial dysfunction in these murine HFpEF hearts with NAD+ repletion therapy, leading to marked improvements in cardiac structure and function.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in HFpEF.

Using a platform of two different mitochondrial preparations, we detected specific defects in the oxidation of both pyruvate and fatty acids in HFpEF mitochondria. Importantly, TCA cycle and ETC function were normal in these mitochondria. These data suggest a possible metabolic “two-hit” attack on mitochondrial function. The decrease in pyruvate oxidation could be considered one “hit”. Indeed, increases in PDK4 levels that we detected, and consequent declines in PDH function, mirror what we have observed previously in long-term HFD exposure24. Then, impairment in FAO oxidation in HFpEF hearts could be considered the second “hit”. Indeed, the effectiveness of NAD+ repletion in mitigating the defect in FAO, but not that of pyruvate oxidation, suggests that both “hits” are required for the HFpEF phenotype, and rescuing either pathway might yield therapeutic benefit.

Impaired myocardial energetic reserve secondary to mitochondrial dysfunction is thought to be a major contributor to HFrEF pathogenesis25. Consistent with our observation of mitochondrial dysfunction in HFpEF myocardium, previous studies have reported impaired myocardial energetics, including reduced PCr/ATP ratios, in the heart of HFpEF patients26, suggesting that energy deficiency resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction likely plays a critical role in both HFpEF and HFrEF. It is worth noting that in the present initial study, we mainly used OCR to tease out specific defects in the mitochondria, a strategy based on measuring maximum metabolic capacity in the presence of excess substrate. Further studies to evaluate substrate preference in HFpEF hearts under different conditions are warranted.

In mitochondria, the acetylation level of various proteins is tightly associated with their enzymatic activities and under the orchestrated control of key enzymes, including sirtuin deacetylases and the protein acetylase GCN5L127. The important role of Sirt3, the major mitochondrial sirtuin, in maintaining basal cardiac function and stress responsiveness has been demonstrated in previous studies, as Sirt3 knockout mice manifest accelerated age-related cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis28 and increased susceptibility to cardiac stressors29. We found that Sirt3 is significantly down-regulated in HFpEF hearts, which likely contributes to the observed mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation. The fact that cardiomyocyte-specific Sirt3 KO mice developed accelerated diastolic dysfunction under HFpEF conditions further supports the notion of protective effects of Sirt3 in HFpEF pathogenesis.

Studies using genetically modified mice manifesting mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation under different physiological/pathological conditions have yielded conflicting results regarding the impact of lysine acetylation on mitochondrial function30–32. This suggests that the effect could be context-specific depending on target protein, stoichiometry, or specific lysine sites, etc.

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent deacetylases, and reduced NAD+ bioavailability has been reported in a wide variety of conditions, including aging, HFrEF, and more27. In myocardial tissue, NAD+ is mainly synthesized via the salvage pathway in which Nampt is the rate-limiting enzyme18. Nampt down-regulation has been reported in a variety of cardiac pathologies, including ischemia and pressure overload33, and mice with Nampt selectively up-regulated in cardiomyocytes are protected from these conditions34. Here, for the first time, we report that Nampt down-regulation-mediated NAD+ deficiency also plays a role in HFpEF pathogenesis. Importantly, we confirmed this finding in cardiac tissue of HFpEF patients, suggesting strongly that our observations pertain to human HFpEF.

Potential Therapeutic Intervention.

NAD+ precursors, including NR, have manifested promising therapeutic benefits in several preclinical models of HFrEF6, 35, 36. This protective effect is likely Sirt3 dependent37, indicating the potential critical role of restoring the mitochondrial acetylome in HF therapy. We have discovered that oral NR effectively corrected cardiac NAD+ deficiency, reversed the hyperacetylation status of key FAO enzymes, and improved mitochondrial function in our murine HFpEF model. This correlated with remarkable attenuation of LVH and diastolic dysfunction, and dramatic improvement of HFpEF functional manifestations, suggesting that NR could potentially emerge as a promising therapeutic agent for HFpEF. It is worth emphasizing that restoration of all these parameters occurred in the continued presence of the HFpEF-triggering comorbidities of mechanical and metabolic stress.

Consistent with previous findings, NR supplementation improved systemic insulin sensitivity in our mouse model. Therefore, it is possible that the observed improvement in cardiac mitochondrial function and HFpEF symptoms in NR-treated mice is the consequence of improved systemic insulin sensitivity. To test for a causal link between NAD+ homeostasis and HFpEF, we employed a direct Nampt activator P7C3-A20, initially discovered as a pro-neurogenic compound38 and later found to exert therapeutic effects via stimulating Nampt21. Despite promising benefits in multiple preclinical models of neurodegenerative diseases21, its impact in HF has never been tested. We have discovered that P7C3-A20, similar to NR, boosts cardiac NAD+ levels and improves cardiac function in HFpEF mice. Importantly, this therapeutic benefit was independent of its impact on systemic insulin signaling. Therefore, our study suggests that Nampt-mediated NAD+ deficiency plays a critical role in HFpEF pathogenesis, and therapies targeting this defect hold promise in clinical application.

Traditional HFrEF therapies targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and adrenergic axes have failed in clinical trials targeting HFpEF39, indicating that those pathways are likely not shared between these two subtypes of HF. Work reported here reveals, for the first time, that mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly NAD+ deficiency-associated mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation, is likely a mechanism contributing to both HFrEF and HFpEF pathogenesis. Therefore, therapies that target this common pathway could emerge as a new avenue for the treatment of both HF syndromes. Clinical trials testing the effect of NR in HFrEF are ongoing (NCT03423342), and evaluation of its clinical impact in the HFpEF population is in preparation at our institution.

Limitations and Perspective.

Our murine HFpEF model is established based on the presence of both hypertensive and metabolic stress, therefore likely only representing a subgroup of HFpEF patients with significant metabolic disturbance2. This is important in selecting the optimal patient population in future clinical trials. Second, although we detected hyperacetylation of key FAO enzymes and suppressed FAO activity in HFpEF hearts, we did not establish a direct mechanistic link between protein hyperacetylation and mitochondrial dysfunction. The fact that we observed attenuated hyperacetylation of specific FAO enzymes, but no changes in total acetylation levels in NR-treated hearts, suggests that the modification is specific. Further work is required to delineate additional details. Although we confirmed down-regulation of Nampt transcript in human HFpEF myocardium, further work is needed to test for NAD+ deficiency in human tissue. Finally, as this is the first proof-of-concept study, clinical characteristics of our patient groups are not ideally matched. A larger, better matched clinical study is indicated.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a highly prevalent and mortal clinical syndrome without evidence-based therapies.

Metabolic diseases commonly coexist with HFpEF. However, metabolic alterations in HFpEF hearts are poorly understood.

A novel “two hit” murine model of HFpEF in which concomitant metabolic and hypertensive stress recapitulates the myriad features of human HFpEF.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation associated with hyperacetylation of key enzymes in the pathway was observed in HFpEF myocardium.

Down-regulation of sirtuin 3 and deficiency of NAD+ secondary to an impaired NAD+ salvage pathway contribute to the observed mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation.

NAD+ repletion by supplementing HFpEF mice with nicotinamide riboside or a direct activator of NAD+ biosynthesis led to improvement in mitochondrial function and amelioration of the HFpEF phenotype.

The pathophysiology of HFpEF is poorly understood, hampering development of effective therapeutics. Here, using our recently reported “two hit” murine model that recapitulates the myriad clinical features of HFpEF, we unveiled specific metabolic changes in HFpEF myocardium and identified mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation secondary to NAD+ deficiency as an underlying mechanism. Our data support the notion that NAD+ repletion could serve as a promising therapeutic approach for HFpEF.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from NIH: HL-120732 (J.A.H.), HL-128215 (J.A.H.), HL-126012 (J.A.H.), HL-147933 (J.A.H.), HL-155765 (J.A.H.) F32HL142244 (D.T.); American Heart Association (AHA): 14SFRN20510023 (J.A.H.), 14SFRN20670003 (J.A.H.), AHA and the Theodore and Beulah Beasley Foundation 18POST34060230 (G.G.S.), University Federico II of Naples and Compagnia di San Paolo STAR program (G.G.S.), Fondation Leducq TransAtlantic Network of Excellence11CVD04 (J.A.H.), Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas RP110486P3 (J.A.H.) and by Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico, FONDAP 15130011 (S.L.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- L-NAME

N[w]-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- HFD

High fat diet

- Sirt3

Sirtiun3

- AMVMs

Adult mouse ventricular myocytes

- NR

Nicotinamide riboside

- VLCAD

Very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- GCN5L1

General Control of amiNo acid synthesis 5-Like 1

- NAD+

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- Nampt

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

Footnotes

This article is published in its accepted form. It has not been copyedited and has not appeared in an issue of the journal. Preparation for inclusion in an issue of Circulation Research involves copyediting, typesetting, proofreading, and author review, which may lead to differences between this accepted version of the manuscript and the final, published version.

DISCLOSURES

G.G.S., T.G.G. and J.A.H. are co-inventors on a patent application (PCT/US/2017/037019) that was filed in June 2017 (provisional application filed in June 2016). The patent relates to the diet used for modeling HFpEF.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunlay SM, Roger VL and Redfield MM. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2017;14:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, van Heerebeek L, Zile MR, Kass DA and Paulus WJ. Phenotype-Specific Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Multiorgan Roadmap. Circulation. 2016;134:73–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitzman DW and Shah SJ. The HFpEF Obesity Phenotype: The Elephant in the Room. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:200–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, French KM, Villalobos E, Kim SY, Luo X, Jiang N, May HI, Wang ZV, Hill TM, Mammen PPA, Huang J, Lee DI, Hahn VS, Sharma K, Kass DA, Lavandero S, Gillette TG and Hill JA. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. 2019;568:351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong D, Schiattarella GG, Jiang N, May HI, Lavandero S, Gillette TG and Hill JA. Female Sex Is Protective in a Preclinical Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2019;140:1769–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diguet N, Trammell SAJ, Tannous C, Deloux R, Piquereau J, Mougenot N, Gouge A, Gressette M, Manoury B, Blanc J, Breton M, Decaux JF, Lavery GG, Baczko I, Zoll J, Garnier A, Li Z, Brenner C and Mericskay M. Nicotinamide Riboside Preserves Cardiac Function in a Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;137:2256–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauman MD, Schumann CM, Carlson EL, Taylor SL, Vazquez-Rosa E, Cintron-Perez CJ, Shin MK, Williams NS and Pieper AA. Neuroprotective efficacy of P7C3 compounds in primate hippocampus. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parra V, Altamirano F, Hernandez-Fuentes CP, Tong D, Kyrychenko V, Rotter D, Pedrozo Z, Hill JA, Eisner V, Lavandero S, Schneider JW and Rothermel BA. Down Syndrome Critical Region 1 Gene, Rcan1, Helps Maintain a More Fused Mitochondrial Network. Circ Res. 2018;122:e20–e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crewe C, Kinter M and Szweda LI. Rapid inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase: an initiating event in high dietary fat-induced loss of metabolic flexibility in the heart. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuznetsov AV, Veksler V, Gellerich FN, Saks V, Margreiter R and Kunz WS. Analysis of mitochondrial function in situ in permeabilized muscle fibers, tissues and cells. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:965–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason KE, Stofan DA and Szweda LI. Inhibition of very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase during cardiac ischemia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;437:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stram AR and Payne RM. Post-translational modifications in mitochondria: protein signaling in the powerhouse. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:4063–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Grueter CA, Harris C, Biddinger S, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD, Li Y, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Bain JR, Newgard CB, Farese RV Jr., Alt FW, Kahn CR and Verdin E. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464:121–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Bharathi SS, Rardin MJ, Uppala R, Verdin E, Gibson BW and Goetzman ES. SIRT3 and SIRT5 regulate the enzyme activity and cardiolipin binding of very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson BS, Campbell JE, Ilkayeva O, Grimsrud PA, Hirschey MD and Newgard CB. Remodeling of the Acetylproteome by SIRT3 Manipulation Fails to Affect Insulin Secretion or beta Cell Metabolism in the Absence of Overnutrition. Cell Rep. 2018;24:209–223 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Huang JY, Schwer B and Verdin E. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial protein acetylation and intermediary metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershberger KA, Martin AS and Hirschey MD. Role of NAD(+) and mitochondrial sirtuins in cardiac and renal diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:213–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matasic DS, Brenner C and London B. Emerging potential benefits of modulating NAD(+) metabolism in cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314:H839–H852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martens CR, Denman BA, Mazzo MR, Armstrong ML, Reisdorph N, McQueen MB, Chonchol M and Seals DR. Chronic nicotinamide riboside supplementation is well-tolerated and elevates NAD(+) in healthy middle-aged and older adults. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshino J, Mills KF, Yoon MJ and Imai S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011;14:528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G, Han T, Nijhawan D, Theodoropoulos P, Naidoo J, Yadavalli S, Mirzaei H, Pieper AA, Ready JM and McKnight SL. P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals function by activating the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD salvage. Cell. 2014;158:1324–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou B and Tian R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3716–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaanine AH, Joyce LD, Stulak JM, Maltais S, Joyce DL, Dearani JA, Klaus K, Nair KS, Hajjar RJ and Redfield MM. Mitochondrial Morphology, Dynamics, and Function in Human Pressure Overload or Ischemic Heart Disease With Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battiprolu PK, Hojayev B, Jiang N, Wang ZV, Luo X, Iglewski M, Shelton JM, Gerard RD, Rothermel BA, Gillette TG, Lavandero S and Hill JA. Metabolic stress-induced activation of FoxO1 triggers diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:1109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neubauer S The failing heart--an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phan TT, Abozguia K, Nallur Shivu G, Mahadevan G, Ahmed I, Williams L, Dwivedi G, Patel K, Steendijk P, Ashrafian H, Henning A and Frenneaux M. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is characterized by dynamic impairment of active relaxation and contraction of the left ventricle on exercise and associated with myocardial energy deficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:402–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane AE and Sinclair DA. Sirtuins and NAD(+) in the Development and Treatment of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ Res. 2018;123:868–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hafner AV, Dai J, Gomes AP, Xiao CY, Palmeira CM, Rosenzweig A and Sinclair DA. Regulation of the mPTP by SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of CypD at lysine 166 suppresses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:914–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parodi-Rullan RM, Chapa-Dubocq XR and Javadov S. Acetylation of Mitochondrial Proteins in the Heart: The Role of SIRT3. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams AS, Koves TR, Davidson MT, Crown SB, Fisher-Wellman KH, Torres MJ, Draper JA, Narowski TM, Slentz DH, Lantier L, Wasserman DH, Grimsrud PA and Muoio DM. Disruption of Acetyl-Lysine Turnover in Muscle Mitochondria Promotes Insulin Resistance and Redox Stress without Overt Respiratory Dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2020;31:131–147 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson MT, Grimsrud PA, Lai L, Draper JA, Fisher-Wellman KH, Narowski TM, Abraham DM, Koves TR, Kelly DP and Muoio DM. Extreme Acetylation of the Cardiac Mitochondrial Proteome Does Not Promote Heart Failure. Circulation research. 2020;127:1094–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen T, Liu J, Li N, Wang S, Liu H, Li J, Zhang Y and Bu P. Mouse SIRT3 attenuates hypertrophy-related lipid accumulation in the heart through the deacetylation of LCAD. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu CP, Oka S, Shao D, Hariharan N and Sadoshima J. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates cell survival through NAD+ synthesis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105:481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto T, Byun J, Zhai P, Ikeda Y, Oka S and Sadoshima J. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, an intermediate of NAD+ synthesis, protects the heart from ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee CF and Tian R. Mitochondrion as a Target for Heart Failure Therapy-Role of Protein Lysine Acetylation. Circ J. 2015;79:1863–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CF, Chavez JD, Garcia-Menendez L, Choi Y, Roe ND, Chiao YA, Edgar JS, Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Bruce JE and Tian R. Normalization of NAD+ Redox Balance as a Therapy for Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;134:883–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin AS, Abraham DM, Hershberger KA, Bhatt DP, Mao L, Cui H, Liu J, Liu X, Muehlbauer MJ, Grimsrud PA, Locasale JW, Payne RM and Hirschey MD. Nicotinamide mononucleotide requires SIRT3 to improve cardiac function and bioenergetics in a Friedreich’s ataxia cardiomyopathy model. JCI Insight. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pieper AA, Xie S, Capota E, Estill SJ, Zhong J, Long JM, Becker GL, Huntington P, Goldman SE, Shen CH, Capota M, Britt JK, Kotti T, Ure K, Brat DJ, Williams NS, MacMillan KS, Naidoo J, Melito L, Hsieh J, De Brabander J, Ready JM and McKnight SL. Discovery of a proneurogenic, neuroprotective chemical. Cell. 2010;142:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make their data, analytic methods, and study materials available to other researchers based on reasonable request.