Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of depression in patients attending eye clinics?

Findings

In this meta-analysis, depression was found to be common (prevalence of 25%) in patients with visual impairment and those aged older than 65 years.

Meaning

These results suggest that depression in patients with visual impairment is a relatively common health problem in the clinic and in patients with cognitive impairment.

This meta-analysis uses data from a MEDLINE and Embase search to assess the prevalence of depression among patients with visual impairment.

Abstract

Importance

Given that depression is treatable and some ocular diseases that cause visual loss are reversible, early identification and treatment of patients with visual impairment who are most at risk of depression may have an important influence on the well-being of these patients.

Objective

To conduct a meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in patients with visual impairment who regularly visit eye clinics and low vision rehabilitation services.

Data Sources

MEDLINE (inception to June 7, 2020) and Embase (inception to June 7, 2020) were searched.

Study Selection

Studies that obtained data on the association between acquired visual impairment and depression among individuals aged 18 years or older were identified and included in this review. Exclusion criteria comprised inherited or congenital eye diseases, review studies, unpublished articles, abstracts, theses, dissertations, and book chapters. Four independent reviewers analyzed the results of the search and performed the selection and data extraction to ensure accuracy.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Meta-analyses of prevalence were conducted using random-intercept logistic regression models. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of depression.

Results

A total of 27 studies were included in this review, and all but 2 included patients older than 65 years. Among 6992 total patients (mean [SD] age, 76 [13.9] years; 4195 women [60%]) with visual impairment, in 1687 patients with depression, the median proportion of depression was 0.30 (range, 0.03-0.54). The random-effects pooled estimate was 0.25 (95% CI, 0.19-0.33) with high heterogeneity (95% predictive interval, 0.05-0.70). No patient characteristic, measured at the study level, influenced the prevalence of depression, except for the inclusion of patients with cognitive impairment (0.33; 95% CI, 0.28-0.38 in 14 studies vs 0.18; 95% CI, 0.11-0.30 in 13 studies that excluded this with major comorbidities; P = .008). The prevalence of depression was high both in clinic-based studies (in 6 studies, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.23-0.47) and in rehabilitation services (in 18 studies, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.33 vs other settings in 3 studies, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.05-0.38; P = .17), and did not vary by visual impairment severity of mild (in 8 studies, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.14-0.38), moderate (in 10 studies, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.21-0.39), and severe (in 5 studies, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.12-0.56; P = .51).

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that depression in patients with visual impairment is a common problem that should be recognized and addressed by the health care professionals treating these patients.

Introduction

Low vision negatively affects quality of life and is associated with reduced functional ability, increased disability, falls, social isolation, institutionalization, and mortality. A recent systematic review identified hearing and visual loss as markers of frailty in community-based studies, with depression being a primary associated morbidity.1 Depression is common in older adults and even more common in those with visual impairment. Clinically significant subthreshold depression has been found in one-third of older adults with visual impairment, approximately twice as high as the lifetime prevalence rates in older adults without visual impairment, where depressive symptoms are present roughly in 15%.2,3,4,5,6,7 Depression is a serious medical condition, and even mild symptoms may affect quality of life.6 Patients with vision loss may experience a greater burden of their disability, as depression is often accompanied by low energy levels, sleep problems, cognitive problems, or disproportionate worrying. Depression can also affect a person’s learning capacity or the ability to retain information, make decisions, or achieve goals.8 Therefore, treatment of depression has increasingly gained attention within eye care settings as shown by numerous mental health care programs that have been tested and often found effective.9 A Cochrane systematic review investigated the effect of several interventions to improve the quality of life of patients with low vision and found that psychological therapies or group programs may reduce depression and increase self-esteem in people with low vision.10

Depression screening has been recommended as a part of low vision services, with appropriate training of rehabilitation professionals and the use of standardized questions in both high-income and low-middle–income countries.11,12 In low vision services in Wales, barriers to optimal depression screening have been identified, including perceived patient reluctance to discuss depression, time constraints, and lack of confidence in addressing depression.11 On the other hand, low vision professionals were found to lack confidence in their knowledge and skills to address depression.13 Because recent projections show a large increase in people with vision loss due to population growth and demographic aging,14 it is also important to understand the increasing burden of mental health needs in eye clinics and low vision and mental health centers. To our knowledge, no recent reviews or meta-analyses have been published on the prevalence of depression in patients visiting eye clinics and low vision services, regardless of ocular causes or age ranges. Our study aimed to investigate this prevalence with the goal of developing public health strategies for people accessing eye services.

Methods

This meta-analysis included a search of MEDLINE (via PubMed) and Embase databases from inception to June 7, 2020. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.

Inclusion Criteria

This meta-analysis included cross-sectional studies of adult patients (18 years or older) attending primary or secondary care eye services and low vision rehabilitation services. We included baseline data from randomized controlled trials only if they were considered representative of populations with visual impairment.

We accepted the diagnostic category of visual impairment as applied by the authors of each study, and we used the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11)15 to form study subgroups according to distance visual impairment severity, defined according to the best-corrected visual acuity in the better-seeing eye as mild (20/40 or better), moderate-severe (better than 20/200 but worse than 20/40), or blindness (worse than 20/400).

We accepted the diagnostic category of depression as applied by the authors of each study, including validated tools and questionnaires, depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition; DSM-III) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition; DSM-IV) or standard psychiatric diagnostic criteria, and self-reported depressive disorder. Original research had to be reported in English with adequate information on the prevalence of depression. We used the following exclusion criteria: inherited or congenital eye diseases only, review studies, unpublished articles, abstracts, theses, dissertations, and book chapters.

Search Strategy

The MEDLINE and Embase search strategies are shown in detail in the eMethods in the Supplement. Four independent reviewers (E.M., F.M., D.P., and M.P.) analyzed the results of the search and performed the selection, classification of literature, and data extraction to ensure accuracy. Discrepancies were addressed by discussion or with a fifth reviewer (G.V.).

Risk of Bias Assessment

All included studies were subject to methodologic critical appraisal using an adapted risk of bias assessment for prevalence studies.16 The risk of bias assessment used 5 domains, which included lack of generalizability bias, record bias, attrition bias, detection bias, and reporting bias. Every domain received a maximum of 2 points (eMethods in the Supplement).

Statistical Methods

Study prevalence was pooled using the metaprop command in R software (R Foundation) with the following specifications, according to Schwarzer et al17: we fitted a random-intercept logistic regression model, used a maximum-likelihood estimator for tau2, a logit transformation of proportions, and a Clopper-Pearson CI for individual studies.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed graphically by inspecting the overlap of study CIs and also estimating and presenting the 95% predictive interval, which comprises between-study variance. A preplanned heterogeneity investigation was conducted, adding study-level categorical covariates to the model: age (median, 75 years or older vs younger than 75 years), inclusion of patients with major chronic conditions (vs exclusion), types of validated questionnaires or scales used to diagnose depression (most common tools in studies), and severity of visual loss (mild, moderate, or severe according to the reported better-seeing eye visual acuity distribution). Post-hoc subgroup analyses were conducted by sample size (median, 125 patients or more vs 125 patients or fewer). Further subgroup analyses by causes of low vision were not conducted, because studies generally included people with multiple diseases. Significance was set at P < .05, and all P values were 2-sided.

Results

Results of Searches

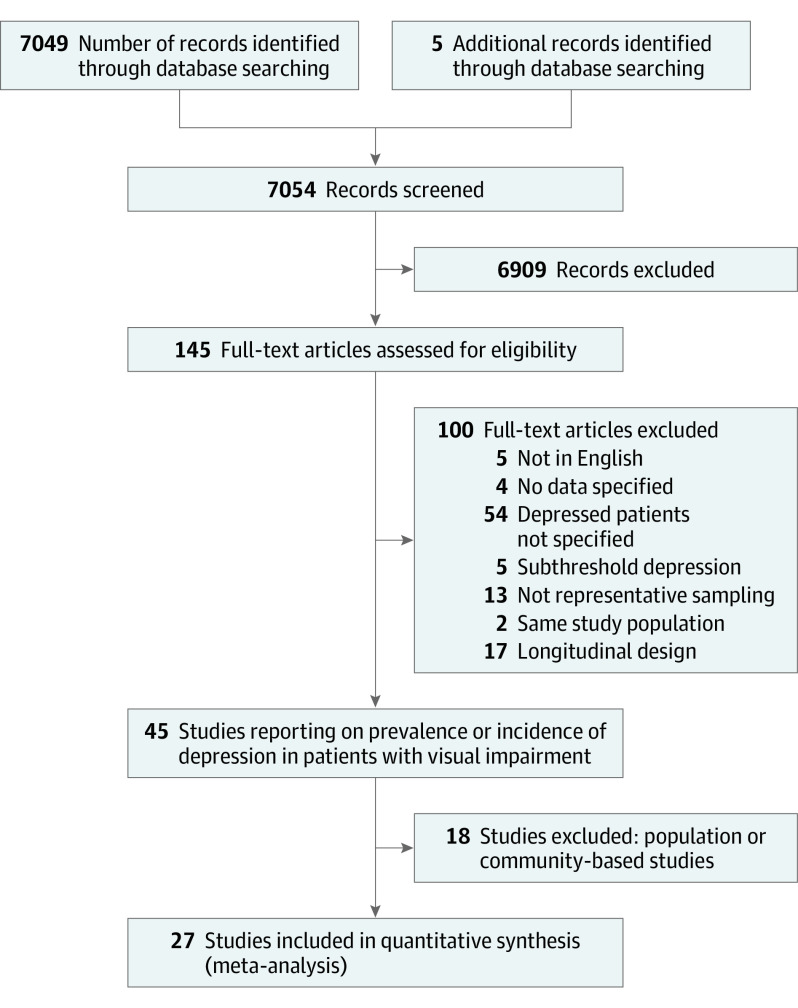

Our search found 7054 potentially related studies; 6909 articles were rejected as obviously unsuitable because they were unrelated to depression in people with visual impairment. Of the 145 remaining articles, 100 were rejected for a variety of reasons, including articles not written in English; those with unspecified data, ie, the number of people with depression and visual impairment was not available; subthreshold depression was used as a target disease definition; there was no representative sampling; the study population was identical to that of other included studies; or a longitudinal design was used. Forty-five remaining studies included patients with low vision in whom depression status was investigated. Of these, 18 studies were community- or population-based and will be considered in a future review. The remaining 27 studies were conducted in eye clinics or low vision centers and were included in this review, and all but 2 included patients older than 65 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trial Flow Diagram Summarizing the Process for Selecting Original Articles for Review.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A summary of the main characteristics of the included 27 studies4,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 is presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Seven studies were conducted in Europe,19,20,25,26,30,33,35 8 in the US,4,22,27,31,34,38,39,42 3 in Asia,18,21,43 8 in Oceania,23,24,28,29,32,37,40,41 and 1 in Africa.36 The number of participants ranged from 53 to 990.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Source | Clinical setting | No. of participants | Mean age, y | Level of visual impairment | Depression diagnostic tool | Exclusions for comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al,18 2019, South Korea | Low vision clinic | 70 | 45 | Moderate | BDI | None |

| Crewe et al,29 2011, Australia | Association for the Blind register | 156 | 74 | Severe | SR | HTN, CVD, diabetes, CeV, cancer |

| Dreer et al,31 2005, United States | Low vision clinic | 51 | 74 men, 69 women | NS | CESDS | None |

| Girdler et al,37 2010, Australia | Low vision clinic | 77 | 79 | Mild | GDS | None |

| Goldstein et al,38 2012, United States | Low vision clinic | 764 | 77 | Mild | GDS | Diabetes, CVD, HTN, TD, Parkinson, PD, cancer, stroke, others |

| Goldstein et al,39 2014, United States | Low vision clinic | 779 | 76 | Moderate | GDS | Memory disorder, others NS |

| Hayman et al,40 2007, New Zealand | Trial on fall prevention in visual impairment | 391 | 83 | Moderate | GDS | None |

| Holloway et al,41 2015, Australia | Low vision clinic | 124 | 77 | Mild | PHQ-2 | None |

| Holloway et al,32 2015, Australia | Low vision clinic | 168 | 70 | Mild | PHQ | None |

| Horowitz et al,4 2005, United States | Low vision clinic | 584 | 80 | Mild | DSM-IV, CESDS | None |

| Horowitz et al,42 2005, United States | Low vision clinic | 95 | 77 | NS | CESDS | None |

| Ip et al,43 2000, China | Nursing home for blind people | 53 | 86 | Severe | GDS | None |

| Kempen et al,19 2014, the Netherlands | Low vision clinic | 149 | 77 | Severe | HADS | None |

| King et al,33 2007, United Kingdom | Registered and not registered blind people and those with visual impairment | 66 | 80 | Severe | GDS | None |

| Mayro et al,34 2020, United States | Eye clinic | 42 | 52 | Moderate | PHQ | Diabetes, HTN, CVD |

| Mylona et al,35 2020, Greece | Eye clinic | 100 | 68 | Severe | BDI II | Diabetes, HTN, Hyperlipidemia |

| Nollet et al,20 2019, Britain | Low vision clinic | 990 | 79 | Moderate | GDS | Diabetes, epilepsy, stroke, TD, CVD, HTN, PD, others NS |

| Noran et al,21 2008, Malaysia | Eye clinic | 430 | 69 | Moderate | GDS | None |

| Owsley et al,22 2004, United States | Drivers with visual impairment involved in car accident | 397 | 74 | Mild | CESDS | None |

| Onwubiko et al,36 2020, Nigeria | Eye clinic | 124 | ≥40a | Mild | HADS | None |

| Rees et al,23 2010, Australia | Eye clinic | 143 | 76 | Mild | PHQ-9 | None |

| Rees et al,24 2019, Australia | Residents with visual impairment living in a facility for older adults | 131 | 84 | Mild | CSDD | None |

| Renieri et al,25 2013, Germany | Low vision clinic | 87 | 75 | Severe | HADS | CVD, MD, OAD |

| Robertson et al,26 2006, United Kingdom | Society for the Blind database | 124 | 71 | Moderate | HADS | None |

| Shmuely-Dulitzky et al,27 1995, United States | Low vision clinic | 70 | 78 | Moderate | DSM-III | None |

| Sturrock et al,282014, Australia | Eye clinic | 161 | 70 | Moderate | PHQ | None |

| Van der Aa et al,30 2015, Belgium | Low vision clinic | 871 | 73 | Moderate | MINI | OAD, PD, cancer, DM, CVD, CeV, stroke, others |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CESDS, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CeV, cerebrovascular disease; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition); GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HTN, hypertension; MD, metabolic disease; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NS, not specified; OAD, osteoarticular disease; PD, pulmonary disease; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SR, self-report; TD, thyroid disease.

A total of 89% of patients were aged 40 years or older.

Table 2. Quality Assessment of Included Studiesa.

| Source | Lack of generalizability bias | Record bias | Attrition bias | Detection bias | Reporting bias | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al,18 2019 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Crewe et al,29 2011 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Dreer et al,31 2005 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Girdler et al,37 2010 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Goldstein et al,38 2012 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Goldstein et al,39 2014 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Hayman et al,40 2007 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Holloway et al,41 2015 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Holloway et al,32 2015 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Horowitz et al,4 2005 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Horowitz et al,42 2005 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Ip et al,43 2000 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Kempen et al,19 2014 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| King et al,33 2006 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Mayro et al,34 2020 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Mylona et al,35 2020 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nollet et al,20 2019 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Noran et al,21 2008 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Owsley et al,22 2004 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Onwubiko et al,36 2020 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Rees et al,23 2010 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Rees et al,24 2019 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Renieri et al,25 2013 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Robertson et al,26 2006 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Shmuely-Dulitzky et al,27 1995 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Sturrock et al,28 2014 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Van der Aa et al,30 2015 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

The number of points (0, 1, or 2) within a domain in the quality scale used for each category are shown.

Studies were conducted in clinical eye care settings(6 studies, 796 patients),21,23,28,34,35,36 rehabilitation settings (18 studies, 5615 patients), or other health care settings (3 studies, 581 participants). Rehabilitation settings included low vision clinics and blindness-related society services,4,18,19,20,25,27,29,30,31,32,37,38,39,41,42 registered and nonregistered patients with visual impairment,33 patients included in a randomized controlled trial on fall prevention,40 and patients from the Society for the Blind database.26 Other health care settings included residents with visual impairment living in a care facility for older adults24 or in a nursing home for blind people,43 and the assessment of drivers with visual impairment who had been in a car crash.22

Various definitions of visual impairment were adopted in the studies (Table 1); 12 studies (44.4%) did not provide a definition of visual impairment.4,19,20,25,26,27,31,33,36,38,39,42 In all but 1 study (3.7%),22 patients were attending or were scheduled to attend low vision rehabilitation and were consistent with our target population. Six studies (22.2%) defined visual impairment as best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or worse in the better-seeing eye.23,24,28,32,37,41 Three studies (11.1%) expressed visual acuity in logMAR, considering visual impairment to be visual acuity worse than 20/80.18,34,40 One study (3.7%) used a visual impairment diagnosis based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).21

Depression was assessed using a number of different tools: the Geriatric Depression Scale-15,44 used in 8 studies (29.6%)20,21,33,37,38,39,40,43; the Patient Health Questionnaire-9,45,46 used in 3 studies (11.1%)23,28,34; the Patient Health Questionnaire-2,47 used in 2 studies (7.4%)32,41; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,48 used in 4 studies (14.8%)19,25,26,36; and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESDS),49 used in 4 studies (14.8%).4,22,31,42 Two studies (7.4%)27,42 used a depression diagnosis based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III or DSM-IV).50,51 Other tools used for depression diagnosis were the Beck Depression Inventory, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Self-reported depression was accepted in 1 study (3.7%).29

Table 2 summarizes the risk of bias assessment for all included studies. Most studies had 1 or 2 points in the major domains of the quality scale used. Nine of the 27 studies (33.3%) reached a total score between 8 and 9 points,18,21,23,27,28,32,34,39,43 whereas 18 (66.7%) reached a total score between 6 and 7 points.4,19,20,22,24,25,26,29,30,31,33,35,36,37,38,40,41,42

Generalizability bias reached a score of 2 points in 7 of the 27 studies (25.9%)18,23,28,34,35,41,43 and 1 point in 20 (74.1%).4,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,38,39,40,42 The main problems related to this quality domain were lack of clarity regarding the definition of visual impairment and/or depression. All studies were prospective and gained 2 points for record bias, although it was sometimes unclear whether consecutive patients were included. Regarding attrition bias, we assigned a score of 0 points to 3 studies (11.1%) in which the percentage of patients enrolled was not specified.4,19,37 Seventeen studies (63.0%) gained 1 point because more than 10% of the eligible patients were not included.20,22,24,25,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,40,41,42 Only 1 study (3.7%)29 obtained 2 points for detection bias, because all the other studies provided no information about masking with respect to vision status and were assigned 1 point. Regarding reporting bias, we assigned 1 point to 4 studies (14.8%),29,33,35,36 and 23 studies (85.2%)4,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 gained 2 points. More details can be found in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Findings

We included 27 studies with a median sample size of 125 patients (range, 42-990 patients). Among 6992 total patients (mean [SD] age, 76 [13.9] years; 4195 women [60%]) with visual impairment, in 1687 patients with depression, the median proportion of depression was 0.30 (range, 0.03-0.54).

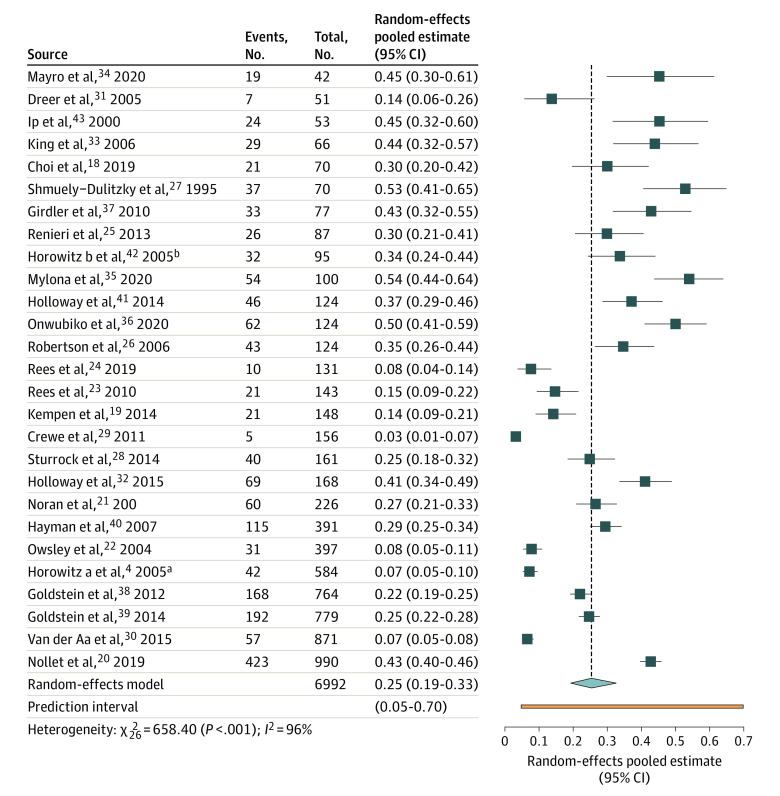

Figure 2 presents the meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression in all studies. Overall, the random-effects pooled estimate was 0.25 (95% CI, 0.19-0.33), with high heterogeneity (95% predictive interval, 0.05-0.70).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression in All Studies.

Studies are sorted according to their sample size. No meta-analysis weights are displayed because a logistic random-effects model was used and weights, being parameter estimations based on an iterative, likelihood-function procedure, are not available.

Subgroup Analyses

We investigated whether study-level variables were associated with differences in prevalence of depression (forest plots and data are presented in eFigures 1-6 the Supplement).

Regarding patients’ characteristics, the proportion of depression did not differ according to median age of 75 years or older (in 16 studies,4,19,20,22,23,24,25,27,33,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.34) vs younger than 75 years (in 11 studies,18,21,26,28,29,30,31,32,34,35,36 0.26; 95% CI, 0.15-0.39; P = .96) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Depression prevalence did not vary significantly with increasing severity of visual impairment of mild (in 9 studies,22,23,24,32,36,37,38,41,42 0.24; 95% CI, 0.14-0.38), moderate (in 10 studies,18,20,21,26,27,28,30,34,39,40 0.29; 95% CI, 0.21-0.39), and severe (in 5 studies,25,29,33,35,43 0.29; 95% CI, 0.12-0.56). The severity of visual impairment was unclear in 3 studies (0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.26; overall P = .51) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).4,19,31 Depression was significantly higher in 14 studies with no exclusion on comorbidities (0.33; 95% CI, 0.28-0.38)4,18,20,21,25,27,31,33,34,38,39,40,41,43 compared with 13 studies that excluded patients with major comorbidities, mainly cognitive impairment (0.18; 95% CI, 0.11-0.30; P = .02)19,22,23,24,26,28,29,30,32,35,36,37,42 (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Regarding study design features, we found that smaller studies with a sample size below the median 125 patients showed a higher depression prevalence (0.39; 95% CI, 0.34-0.45) than larger studies (0.16; 95% CI, 0.11-0.24; P < .001) (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). Prevalence was slightly higher in clinic-based studies (in 6 studies,21,23,28,34,35,36 0.34; 95% CI, 0.23-0.47) compared with those conducted in rehabilitation services (18 studies,4,18,19,20,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,37,38,39,40,41,42 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.33) and other settings (3 studies,22,24,43 0.15; 95% CI, 0.05-0.38; overall P = .17), but overall these differences were not significant (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

There were significant differences in depression rates using different questionnaires or criteria to diagnose depression (eFigure 6 in the Supplement). Higher levels of depression were found in 2 studies18,35 using the Beck Depression Inventory (0.42; 95% CI, 0.26-0.59) compared with 17 studies19,20,21,23,25,26,28,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,43 using the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (0.33; 95% CI, 0.27-0.40), Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (0.31; 95% CI, 0.21-0.42), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (0.31; 95% CI, 0.19-0.46) (overall P < .001). Lower levels of depression were found when the CESDS (in 4 studies,4,22,31,42 0.13; 95% CI, 0.06-0.24) or other tools (in 3 studies,24,27,30 0.16; 95% CI, 0.04-0.44) were used.

The pooled prevalence estimate of depression did not change (0.25; 95% CI, 0.19-0.33) after excluding 6 studies4,19,29,33,36,37 with a risk of bias score of less than 7 points and only slightly increased to 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.34) after the exclusion of 3 studies22,24,43 conducted in other health care settings.

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that 1 in 4 patients with visual impairment who attended eye care services were affected by depression. Studies in this review included mostly patients aged 65 years or older. The finding of depression was similar, or even more common, among patients in clinical services compared with rehabilitation services, which could reflect patients’ initial shock of receiving a diagnosis of an irreversible eye disease.52 Alternatively, the lower rates of depression associated with rehabilitation services could be due to the fact that initiating low vision rehabilitation has beneficial effects on perceived depression, or it could be due to self-selection of patients who were less depressed seeking help in low vision services. The high rates of depression in adults with visual impairment are often overlooked or underestimated in primary care offices and eye clinics. Although the high prevalence of depression among patients with visual impairment is more likely to be recognized by low vision rehabilitation specialists, these patients are commonly not assessed with appropriate diagnostic procedures nor referred for adequate treatment.53,54,55,56

Further study-level factors associated with lower depression rates were investigated, but a similarly high prevalence was found across subgroups of age and visual impairment severity. Depression was more common in studies that included patients with both visual and cognitive impairment, in studies with a smaller sample size with the primary aim of detecting depression rather than multiple disabilities, and in studies that varied by type of diagnostic tool, with the CESDS commonly used in low prevalence studies. The CESDS may have yielded lower prevalence estimates because it is multidimensional and also has items related to anxiety, sleep, and loneliness. Despite differences in depression, these subgroup outcomes did not support the exclusion of specific patient subgroups from depression screening because a significant proportion of patients with visual impairment were depressed in all subpopulations and settings.

Clinic-based studies did not always report visual impairment in their inclusion criteria, but the setting was consistent with low vision services and eye clinics, suggesting that our results may be widely applicable to these settings. However, nearly all studies were conducted in high-income countries, to which the applicability of our results should be restricted.

These results suggest that all primary and specialized eye care professionals, not only those working in low vision services, should have an appropriate knowledge of this topic and adequate clinical experience to decide when and how to investigate the presence of depression in people with visual impairment and eventually refer patients with depression for appropriate treatment. Treatment and follow-up visits of integrated care, which coordinates ophthalmologists and psychiatric or psychological referrals, may maximize efficiency and lead to effective patient-centered care.9,10,53,54,55,56

Our review of observational cross-sectional studies did not aim to prove a causal relationship between visual impairment and depression. Moreover, the definitions of visual impairment and the cutoffs used for depression diagnosis differed between studies. Nonetheless, the results of our review suggest the need for depression screening in patients attending eye clinics who are 65 years or older and have mild to severe visual loss, regardless of comorbidities.

Longitudinal studies have shown that visual impairment is associated with incident depression, which can be due to difficulties with reading, mobility, and driving.57,58,59 However, longitudinal studies have also found that baseline depression is a predictor of the development of visual impairment.60 The complexity of the interrelationship between depression and visual impairment should also be seen in the framework of the multiplicity of associations between ocular diseases and systemic diseases, specifically neurologic disease. The existence of common causal factors is also key to understanding such complex relationships. Previous studies have demonstrated that diseases of the eye, particularly age-related macular degeneration (AMD), may be associated with higher rates of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease.61,62 On the other hand, smoking, alcohol intake, and lack of exercise are all independent risk factors for AMD, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease,63,64,65,66,67 as well as for cardiovascular disease and cancer. Regardless of the difficulty in assessing causal associations between different systemic diseases, our study results suggest that visual impairment may be used as a cross-sectional marker of multimorbidity and frailty in older patients.

We found few other reviews summarizing the association between depression and visual impairment in clinical settings.68 Among older adults with visual impairment, patients with AMD seem to be at particularly high risk of depression compared with patients with other eye diseases.69 Popescu et al70 compared rates of depression in older adults with AMD, glaucoma, and Fuchs corneal dystrophy and found that the highest rate of depression (39%) was in the AMD group. In their review, Nyman et al71 found that working-age adults were more likely to report mental health issues; however, inconsistent results were found specifically for depression.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Our review did not aim to explore the relationship between visual impairment and depression. Moreover, the definitions of visual impairment and the cutoffs used for depression diagnosis differed between studies. A further limitation of our review is that studies yielded heterogeneous results, as is common for meta-analyses of prevalences, which limits the power of heterogeneity investigations.

Conclusions

Given that depression is treatable and some ocular diseases that cause visual impairment are reversible, early identification and treatment of people most at risk for depression could be associated with their overall well-being.72 The guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence suggest that practitioners working in primary care and general hospital clinics should be aware that patients with a chronic physical health problem, especially those with a functional impairment such as visual impairment, are at high risk of depression. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that patients with positive screening results to at least 1 of 2 standard questions (“During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?”) be referred to their general practitioner for appropriate assessment. The results of this meta-analysis suggest that screening should occur in both low vision settings, such as rehabilitation clinics, and in primary care and general clinical settings, where a high prevalence of visual impairment has been reported.73

These findings also suggest that further research should address the clinical effectiveness of depression screening and treatment among patients with visual impairment. This would mean integrating a screening protocol to detect and treat depression in general eye clinics, low vision, and rehabilitation settings. In cases of major depression, a patient should be referred to their general practitioner or directly to a psychiatrist for appropriate care.74

eMethods. Full Search Strategy

eAppendix. Risk of Bias Assessment of Each Study

eFigure 1. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Age

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Severity of Vision Impairment

eFigure 3. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Exclusions of Other Comorbidities

eFigure 4. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Sample Size

eFigure 5. Forest Plot of Overall Prevalence of Depression According to Setting

eFigure 6. Forest Plot of Overall Prevalence of Depression According to Depression Diagnostic Tool

References

- 1.Tan BKJ, Man REK, Gan ATL, et al. Is sensory loss an understudied risk factor for frailty? a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(12):2461-2470. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL. Depression and anxiety in visually impaired older people. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):283-288. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casten R, Rovner BW, Leiby BE, Tasman W. Depression despite anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(4):506-508. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.24 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Kennedy GJ. Major and subthreshold depression among older adults seeking vision rehabilitation services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):180-187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.van der Aa HPA, Comijs HC, Penninx BWJH, van Rens GHMB, van Nispen RMA. Major depressive and anxiety disorders in visually impaired older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):849-854. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beekman ATF, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174(4):307-311. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffens DC, Fisher GG, Langa KM, Potter GG, Plassman BL. Prevalence of depression among older Americans: the Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):879-888. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Donnell C. The greatest generation meets its greatest challenge: vision loss and depression in older adults. J Vis Impair Blind. 2005; 99(4):197-208. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0509900402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Aa HPA, Margrain TH, van Rens GHMB, Heymans MW, van Nispen RMA. Psychosocial interventions to improve mental health in adults with vision impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36(5):584-606. doi: 10.1111/opo.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Nispen RM, Virgili G, Hoeben M, et al. Low vision rehabilitation for better quality of life in visually impaired adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):CD006543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006543.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nollett C, Bartlett R, Man R, Pickles T, Ryan B, Acton JH. Barriers to integrating routine depression screening into community low vision rehabilitation services: a mixed methods study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):419. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace S, Mactaggart I, Banks LM, Polack S, Kuper H. Association of anxiety and depression with physical and sensory functional difficulties in adults in five population-based surveys in low and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0231563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nollett C, Bartlett R, Man R, Pickles T, Ryan B, Acton JH. How do community-based eye care practitioners approach depression in patients with low vision? A mixed methods study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):426. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2387-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne R, Adelson J, Flaxman S, et al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years and contribution to the global burden of disease in 2020. SSRN Electron J. 2020. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3582742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.International Classification of Diseases. ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics (ICD-11 MMS). Accessed September 16, 2020. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- 16.Bonifazi M, Franchi M, Rossi M, et al. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity in early breast cancer: a cohort study. Oncologist. 2013;18(7):795-801. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ, Rücker G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):476-483. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi SU, Chun YS, Lee JK, Kim JT, Jeong JH, Moon NJ. Comparison of vision-related quality of life and mental health between congenital and acquired low-vision patients. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(10):1540-1546. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0439-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempen GIJM, Zijlstra GAR. Clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety and depression in low-vision community-living older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):309-313. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nollett C, Ryan B, Bray N, et al. Depressive symptoms in people with vision impairment: a cross-sectional study to identify who is most at risk. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e026163. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noran NH, Izzuna MG, Bulgiba AM, Mimiwati Z, Ayu SM. Severity of visual impairment and depression among elderly Malaysians. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2009;21(1):43-50. doi: 10.1177/1010539508327353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owsley C, McGwin G Jr. Depression and the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire in older adults. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(12):2259-2264. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rees G, Tee HW, Marella M, Fenwick E, Dirani M, Lamoureux EL. Vision-specific distress and depressive symptoms in people with vision impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(6):2891-2896. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rees G, McCabe M, Xie J, et al. High vision-related quality of life indices reduce the odds of depressive symptoms in aged care facilities. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(10):1596-1604. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1650889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renieri G, Pitz S, Pfeiffer N, Beutel ME, Zwerenz R. Changes in quality of life in visually impaired patients after low-vision rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36(1):48-55. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328357885b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson N, Burden ML, Burden AC. Psychological morbidity and problems of daily living in people with visual loss and diabetes: do they differ from people without diabetes? Diabet Med. 2006;23(10):1110-1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shmuely-Dulitzki Y, Rovner BW, Zisselman P. The impact of depression on functioning in elderly patients with low vision. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;3(4):325-329. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199503040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturrock BA, Xie J, Holloway EE, et al. The prevalence and determinants of desire for and use of psychological support in patients with low vision. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2014;3(5):286-293. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crewe JM, Morlet N, Morgan WH, et al. Quality of life of the most severely vision-impaired. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(4):336-343. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Aa HPA, Hoeben M, Rainey L, van Rens GHMB, Vreeken HL, van Nispen RMA. Why visually impaired older adults often do not receive mental health services: the patient’s perspective. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(4):969-978. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreer LE, Elliott TR, Tucker E. Social problem-solving abilities and health behaviors among persons with recent-onset spinal cord injury. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11(1):7-13. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCS.0000016265.62022.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holloway EE, Sturrock BA, Lamoureux EL, Keeffe JE, Rees G. Help seeking among vision-impaired adults referred to their GP for depressive symptoms: patient characteristics and outcomes associated with referral uptake. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(2):169-175. doi: 10.1071/PY13085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King E, Gilson S, Peveler R. Psychosocial needs of elderly visually impaired patients: pilot study of patients’ perspectives. Prim Care Ment Heal. 2006;4:185-197. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayro EL, Murchison AP, Hark LA, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors in an urban, ophthalmic population. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;1120672120901701(January). doi: 10.1177/1120672120901701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mylona I, Floros G, Dermenoudi M, Ziakas N, Tsinopoulos I. A comparative study of depressive symptomatology among cataract and age-related macular degeneration patients with impaired vision. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(9):1130-1136. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1728351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onwubiko SN, Nwachukwu NZ, Muomah RC, Okoloagu NM, Ngwegu OM, Nwachukwu DC. Factors associated with depression and anxiety among glaucoma patients in a tertiary hospital South-East Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2020;23(3):315-321. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_140_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girdler SJ, Boldy DP, Dhaliwal SS, Crowley M, Packer TL. Vision self-management for older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(2):223-228. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.147538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT, et al. ; Low Vision Research Network Study Group . Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(8):1028-1037. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein JE, Chun MW, Fletcher DC, Deremeik JT, Massof RW; Low Vision Research Network Study Group . Visual ability of patients seeking outpatient low vision services in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(10):1169-1177. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayman KJ, Kerse NM, La Grow SJ, Wouldes T, Robertson MC, Campbell AJ. Depression in older people: visual impairment and subjective ratings of health. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(11):1024-1030. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318157a6b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holloway EE, Sturrock BA, Lamoureux EL, Keeffe JE, Rees G. Depression screening among older adults attending low-vision rehabilitation and eye-care services: characteristics of those who screen positive and client acceptability of screening. Australas J Ageing. 2015;34(4):229-234. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Boerner K. The effect of rehabilitation on depression among visually disabled older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(6):563-570. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ip SP, Leung YF, Mak WP. Depression in institutionalised older people with impaired vision. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(12):1120-1124. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol J Aging Ment Heal. 1986;5(1-2):165-173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamoureux EL, Chong E, Wang JJ, et al. Visual impairment, causes of vision loss, and falls: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(2):528-533. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(4):596-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1701-1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 51.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 1997.

- 52.Nyman SR, Dibb B, Victor CR, Gosney MA. Emotional well-being and adjustment to vision loss in later life: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(12):971-981. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.626487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216-226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lêng CH, Wang J-D. Long term determinants of functional decline of mobility: an 11-year follow-up of 5464 adults of late middle aged and elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(2):215-220. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee DJ, Gómez-Marín O, Lam BL, Zheng DD, Caban A. Visual impairment and morbidity in community-residing adults: the national health interview survey 1986-1996. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005;12(1):13-17. doi: 10.1080/09286580490907751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renaud J, Bédard E. Depression in the elderly with visual impairment and its association with quality of life. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:931-943. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S27717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heesterbeek TJ, van der Aa HPA, van Rens GHMB, Twisk JWR, van Nispen RMA. The incidence and predictors of depressive and anxiety symptoms in older adults with vision impairment: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2017;37(4):385-398. doi: 10.1111/opo.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keay L, Munoz B, Turano KA, et al. Visual and cognitive deficits predict stopping or restricting driving: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Driving Study (SEEDS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(1):107-113. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pérès K, Matharan F, Daien V, et al. Visual loss and subsequent activity limitations in the elderly: the French Three-City Cohort. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):564-569. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frank CR, Xiang X, Stagg BC, Ehrlich JR. Longitudinal associations of self-reported vision impairment with symptoms of anxiety and depression among older adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(7):793-800. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsai D-C, Chen S-J, Huang C-C, Yuan M-K, Leu H-B. Age-related macular degeneration and risk of degenerative dementia among the elderly in Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):2327-2335.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung S-D, Ho J-D, Hu C-C, Lin H-C, Sheu J-J. Increased risk of Parkinson disease following a diagnosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):464-469.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Velilla S, García-Medina JJ, García-Layana A, et al. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: review and update. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:895147. doi: 10.1155/2013/895147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams MKM, Chong EW, Williamson E, et al. 20/20–Alcohol and age-related macular degeneration: the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(4):289-298. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi D, Choi S, Park SM. Effect of smoking cessation on the risk of dementia: a longitudinal study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(10):1192-1199. doi: 10.1002/acn3.633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255-2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bettiol SS, Rose TC, Hughes CJ, Smith LA. Alcohol consumption and Parkinson’s disease risk: a review of recent findings. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015;5(3):425-442. doi: 10.3233/JPD-150533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Casten RJ, Rovner BW. Update on depression and age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(3):239-243. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835f8e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eramudugolla R, Wood J, Anstey KJ. Co-morbidity of depression and anxiety in common age-related eye diseases: a population-based study of 662 adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:56. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Popescu ML, Boisjoly H, Schmaltz H, et al. Explaining the relationship between three eye diseases and depressive symptoms in older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):2308-2313. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nyman SR, Gosney MA, Victor CR. Psychosocial impact of visual impairment in working-age adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(11):1427-1431. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.164814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carrière I, Delcourt C, Daien V, et al. A prospective study of the bi-directional association between vision loss and depression in the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):164-170. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.NICE . Depression In Adults: Recognition and Management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2009. [PubMed]

- 74.van der Aa HPA, van Rens GHMB, Comijs HC, et al. Stepped care for depression and anxiety in visually impaired older adults: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351(November):h6127. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Full Search Strategy

eAppendix. Risk of Bias Assessment of Each Study

eFigure 1. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Age

eFigure 2. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Severity of Vision Impairment

eFigure 3. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Exclusions of Other Comorbidities

eFigure 4. Forest Plot of Prevalence of Depression According to Sample Size

eFigure 5. Forest Plot of Overall Prevalence of Depression According to Setting

eFigure 6. Forest Plot of Overall Prevalence of Depression According to Depression Diagnostic Tool