Abstract

Constructing synthetic cells has recently become an appealing area of research. Decades of research in biochemistry and cell biology have amassed detailed part lists of components involved in various cellular processes. Nevertheless, recreating any cellular process in vitro in cell-sized compartments remains ambitious and challenging. Two broad features or principles are key to the development of synthetic cells—compartmentalization and self-organization/spatiotemporal dynamics. In this review article, we discuss the current state of the art and research trends in the engineering of synthetic cell membranes, development of internal compartmentalization, reconstitution of self-organizing dynamics, and integration of activities across scales of space and time. We also identify some research areas that could play a major role in advancing the impact and utility of engineered synthetic cells.

Keywords: artificial cells, in vitro reconstitution, protein compartment, synthetic cell

1 |. INTRODUCTION

As James Danielli first envisioned in 1972, biology, like all sciences, is going through an evolutionary process consisting of three phases, namely the observation phase, the analytical phase, and the synthetic phase (Danielli, 1972). We are currently witnessing the peak of the analytical phase of biology, as we continue to unravel cellular mechanisms that still have not been characterized. Nevertheless, like physics and chemistry before it, biology is starting to transition to its synthetic phase, as in the last decades we discovered and optimized methodologies for synthesizing DNA, RNA and proteins. In this regard, synthetic cells (also known as artificial cells) represent the natural evolution of biology as a science. Currently, synthetic cells are defined as encapsulated biochemical systems that can recapitulate one or a few of the functions that a natural cell can perform (Noireaux & Liu, 2020; Xu, Hu, & Chen, 2016; Figure 1). The engineering of synthetic cells can have a variety of purposes. Simple synthetic cells (often known as “protocells”), composed of chemically simple fatty acid membranes enclosing primitive biochemical processes, can be designed to probe the mechanisms of the origin of life on prebiotic Earth (I. A. Chen, Salehi-Ashtiani, & Szostak, 2005; Oberholzer, Wick, Luisi, & Biebricher, 1995). Alternatively, synthetic cells can be designed to recreate specific cellular functions, thus enabling the study of discrete mechanisms or properties outside the complexity of a cell. Finally, although the technology is still in its infancy, synthetic cells hold great promise in biomedicine and biotechnology, they can be engineered to release molecules (e.g., insulin) in response to external stimuli (e.g., presence of glucose [Z. Chen, Wang, et al., 2018]), or acting as programmable nano factories of bioactive drugs or as replacements of natural cells (T. Einfalt et al., 2018; Majumder & Liu, 2017).

FIGURE 1.

Recent advances in constructing synthetic cells involve engineering synthetic cell membranes, development of compartmentalization strategies, and reconstituting dynamic processes in space and time. Black arrows depict the flow of molecules and the exchange of information happening across lipid/protein membranes or between the phase-separated liquid condensates of a membrane-less compartment

2 |. THE BOUNDARY OF SYNTHETIC CELLS

Simply put, a cell is not a cell without a membrane. A membrane boundary is necessary to (1) separate the cellular materials from the external environment and (2) permit selective communication of a cell with its surroundings via membrane-resident channels and transporters. In this section, we briefly discuss the importance of synthetic cell boundaries, the type of molecules used to build the boundary, and efforts in functionalizing this boundary.

2.1 |. The importance of a boundary in synthetic cells

Physically, the presence of a boundary of a synthetic cell permits the sensing of various mechanical stimuli, including tension, fluid shear, or osmotic stresses. Biochemically, the cellular membrane acts as a semi-permeable barrier, permitting nonselective passive diffusion of some molecules, but also allows selective passive or active diffusion by using protein transporters and ion channels. In this way, biochemical reactions inside a cell are regulated by allowing the exchange of chemical information in and out of a cell. Nevertheless, the vast majority of molecules cannot cross the amphiphilic membrane. The diffusion across membranes has been exploited in artificial cell research to allow the bidirectional flow of chemicals. For instance, artificial cells consisting of an encapsulated cell-free expression reaction and genetic circuits have been engineered to uptake chemical messages that Escherichia coli typically cannot sense and translate them into signals that are released via a synthesized pore protein to induce a response in E. coli (Lentini et al., 2014). This highlights the crucial role of a compartment to maintain concentrated transcription and translation machineries while actively exchanging messaging molecules with the external environment. However, relying on nonspecific pore proteins or passive diffusion across the bilayer is often a limiting factor in synthetic cell communication applications. Ideally, only effector molecules should be allowed to diffuse out of the synthetic compartment, while other intermediates and substrates for transcription and translation should be retained in order to prevent premature cessation of protein synthesis.

Another crucial feature that a membrane can exhibit is the nonpermeability to ions. The ability to segregate different ions on the inner and outer surfaces of a membrane creates an electrochemical gradient. The capability to generate, maintain, and modify potential differences through the action of specialized membrane proteins is the core characteristic of excitable cells. Although to-date largely ignored, harnessing membrane potentials in synthetic cell research is a promising endeavor that could lead to a better understanding of electrical intra- and intercellular communications.

2.2 |. Building blocks for a synthetic cell boundary

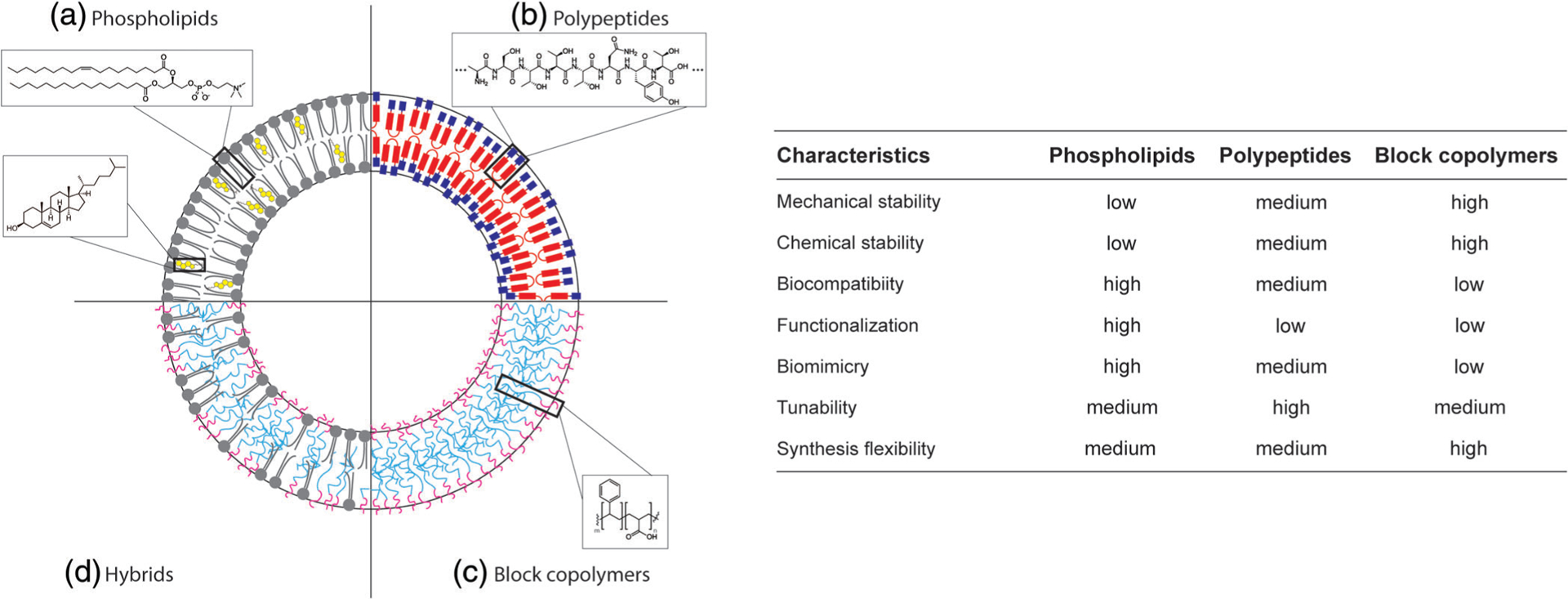

A variety of self-assembling building blocks have been used as the chassis of synthetic cell boundaries (Figure 2). Most notably, phospholipids, polypeptides, and block copolymers have been utilized to construct the membrane of synthetic cells. As the main building blocks of natural cell membranes, phospholipid bilayers maintain natural permeability as well as natural mechanical (e.g., elastic and flexible) and physical (e.g., fluid) properties. It is also the native substrate for hosting membrane proteins. Although microfluidic technologies have greatly facilitated the generation of phospholipid-bound synthetic cells (Majumder, Wubshet, et al., 2019; Trantidou, Friddin, Salehi-Reyhani, Ces, & Elani, 2018), cell-sized liposomes remain mechanically fragile, especially when encapsulating cell-free expression systems.

FIGURE 2.

Possible molecular composition for the boundaries of synthetic cells. Left. (a) A membrane composed by phospholipids and cholesterol is shown. Enlargements show the molecular structures of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and cholesterol. (b) Membrane structure of a proteinosome, showing the spatial organization of oleosin molecules. The enlargement shows a random peptide sequence. (c) Polymerosomal membrane composed by block copolymers. The enlargement shows the molecular structure of polystyrene-b-polyacrilic acid (PS-b-PAA). (d) A phospholipid/block copolymer hybrid membrane is shown. The illustrations are not drawn to scale. Right. Relative comparison of different characteristics between phospholipids, polypeptides, and block copolymers as a chassis material for synthetic cells

Another type of self-assembling molecule that has gained interest recently is polypeptide copolymers. One example is elastin-like protein (ELP), which is an amphiphilic polypeptide that can self-assemble to compartmentalize biochemical reactions. Membranes of synthetic cells made of ELPs have tunable properties as these genetically encoded polypeptides have high chemical diversity (W. Kim & Chaikof, 2010). Through facile cell-free synthesis of ELPs inside an ELP-based vesicle, a synthetic cell with the ability to grow in size was realized, demonstrating the possibility to use ELPs as a membrane constituent of synthetic cells (Vogele et al., 2018). In another study, vesicles of different sizes were constructed by diblocks of polypeptides that are responsive to external chemical stimuli (Bellomo, Wyrsta, Pakstis, Pochan, & Deming, 2004). However, the polypeptide hydrophilic block from Bellomo et al. was composed of ethylene glycol-modified lysine residues. The use of modified amino acids makes it difficult to use a natural protein synthesis approach, and the diblock chain length flexibility was also quite limited. The resulting vesicles were responsive to stimuli only in high pH that makes them impractical in physiological conditions. Additionally, the reversible self-assembling property of ELPs as a function of their transition temperature provides the opportunity of constructing temperature-responsive synthetic cells (Martín, Castro, Ribeiro, Alonso, & Carlos Rodríguez-Cabello, 2012). Nevertheless, ELPs are not the only peptides that can form enclosed structures that are able to host a biological system. For instance, surfactant proteins such as oleosins have been shown to self-assemble into micron-sized compartments whose physical characteristics can be tuned by engineering the sequence of the peptide (Vargo, Parthasarathy, & Hammer, 2012). However, the structural tunability of oleosin polypeptides was limited to truncations from the N- and C- termini of proteins, and the effects of mutations in the sequence of the recombinant oleosin have not been extensively characterized.

Block copolymers represent the third group of molecules as building blocks of synthetic cell membranes. Block copolymers are made of a few domains of polymeric chains with variable lengths that show amphiphilic behavior. The advantage of block copolymer compartments, also known as polymersomes, over liposomes is their higher stability and stiffer structure. Depending on the structural design, polymersomes usually have thicker membranes that are less permeable compared to liposomes. As a step toward constructing multi-compartmentalized synthetic cells, micron-sized polymersomes encapsulating enzyme-filled nano-sized polymersomes can carry out an enzymatic cascade reaction (Peters et al., 2014). Even though the referenced study shows the possibility of mimicry of subcellular organization in a compartment, the practical application of this system as a platform for drug delivery in physiological conditions is limited. Illustration of enzymatic cascade reactions in compartments made of biocompatible materials such as lipids or proteins can be envisioned as the next steps. Besides, the transport between synthetic organelles in this study relies solely on chemical diffusion that may not be optimal in more complex enzymatic reactions. Similarly, multi-compartmentalization of liposomes in polymersomes as a protected environment resembles natural organelles in living cells (Peyret, Ibarboure, Pippa, & Lecommandoux, 2017). Combining the natural properties of phospholipids with the stability of block copolymers brings the possibility of hybrid membranes (Schulz & Binder, 2015). Another example of a hybrid membrane employed organoclay/DNA that self-assembles into a giant compartment that can withstand the nucleation and growth of oxygen bubbles without breaking (Kumar, Patil, & Mann, 2018).

The possibility to build hybrid membranes to compartmentalize enzymatic or cell-free expression reactions will allow the generation of synthetic cells with tunable biophysical and mechanical properties. The inclusion of compatible lipids or polymers in the hybrid membrane will likely allow the incorporation of membrane proteins in the envelope, vastly increasing the versatility of such synthetic cells. The consideration of components of membrane is critical given a major interest in synthetic cell engineering is to create a synthetic cell with the ability to grow and divide robustly in a controlled fashion.

2.3 |. Adding membrane proteins to synthetic cells

In natural cells, a plethora of membrane proteins carry out essential cellular functions ranging from transportation of nutrients to sensing of physical and chemical information. The majority of biological functionalities that have been recreated in synthetic cells have relied on different soluble enzymes or structural proteins that are encapsulated. The potential of synthetic cells for both basic research and translational applications could be greatly expanded by enriching the membrane with membrane proteins having specific functions. The incorporation of membrane proteins in synthetic cells is not trivial, but there have been a number of successes in recent years from either using purified or cell-free expressed proteins.

When it comes to communication across the membrane, the use of a nonspecific pore alpha-hemolysin, either constitutively present or under genetic circuit control, has been a popular choice (Dwidar et al., 2019; Hilburger, Jacobs, Lewis, Peruzzi, & Kamat, 2019) since its pore size of 14 Angstrom allows for the retention of genetic material and most proteins yet allowing small molecules to pass through. Most importantly, it has a strong tendency to insert into lipid membranes upon reconstitution or by cell-free expression.

Among the most significant recent works based on reconstituting purified membrane proteins are a photosynthetic cell that couples light stimulation to drive ATP production for stimulating actin assembly (K. Y. Lee et al., 2018) or for driving protein synthesis (Berhanu, Ueda, & Kuruma, 2019) and the reconstitution of integrin into vesicles for fibrinogen binding (Weiss et al., 2018). An emerging paradigm for membrane engineering relies on the synthesis and incorporation of membrane proteins in situ by the means of a cell-free expression system. Both prokaryotic and mammalian cell-free expression systems have been shown to successfully express structurally intact membrane proteins in mixed micelles or lipid bilayers (Shinoda et al., 2016; Majumder, Willey, et al. 2019). Also, it has been demonstrated that mechanosensitive channel proteins can be successfully expressed and incorporated into synthetic cells (Garamella, Majumder, Liu, & Noireaux, 2019; Hindley et al., 2019; Majumder et al., 2017). Nevertheless, this approach is still in the early stages and only a few membrane proteins have been successfully expressed by prokaryotic and eukaryotic transcription–translation (TX–TL) systems and used in the membrane of synthetic cells to date.

Although lipid bilayers are the natural substrate for membrane proteins, synthetic cells with membranes of block copolymers or hybrid membrane hosting functional membrane proteins or pores have been constructed (Choi & Montemagno, 2007; Einfalt et al., 2015; Jacobs, Boyd, & Kamat, 2019). However, the effect of polymer properties including the length of each block on the membrane protein functionality or its folding characteristics has not been thoroughly investigated. It is worth noting that the translocation of membrane proteins into the polymer or hybrid membranes, in general, may not necessarily be better than phospholipid bilayer membranes.(Göpfrich, Platzman, & Spatz, 2018; Schwille et al., 2018; Wang, Du, Wang, Mu, & Han, 2020) In another work, the bottom-up reconstitution of an artificial mitochondrion was demonstrated in both polymersomes and hybrid membrane vesicles by reconstituting an ATP synthase and a terminal oxidase, furthering the possibility of using hybrid membranes in synthetic cells (Otrin et al., 2017).

2.4 |. Perspectives on the engineering of synthetic cell membranes

Synthetic cell research could be greatly advanced by engineering new functionalities at the synthetic cell boundary. For instance, generalized methods for the incorporation of in situ cell-free expressed adhesion proteins, ion channels, transporters, and signaling receptors would allow sensing of different stimuli, for example, light, ligands, or voltage. Combined with biochemical or genetic circuits, we envision the reconstitution of signaling pathways in synthetic cells. Synthetic cells with an “active” membrane could enable the study of mutant membrane proteins outside of the complexity of a cell. If successfully developed, a synthetic cell platform for membrane protein reconstitution would be much simpler compared to conventional membrane protein purification and would be amenable for drug screening studies as well in building smart drug delivery vehicles.

3 |. COMPARTMENTALIZATION OF SPACES

Cellular compartmentalization and spatial control are defining features of life (Diekmann & Pereira-Leal, 2013). Organelles exist to compartmentalize functions in a cell. In this section, we discuss emerging concepts of cellular compartmentalization including several protein-based organelles found in bacteria and biomolecular condensates. We will not discuss lipid- and vesicle-based strategies explicitly in this section as these approaches are more established and already covered in a number of excellent recent review articles (Göpfrich et al., 2018; Schwille et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

3.1 |. Self-assembling protein organelles

Similar to eukaryotes, many prokaryotes compartmentalize their cytosol to carry out specialized metabolic reactions, prevent toxicity, and store nutrients (Cornejo, Abreu, & Komeili, 2014; Martin, 2010). To achieve this goal, prokaryotes rely on protein-based instead of membrane-based strategies (Figure 3a; Giessen & Silver, 2016a; Kerfeld, Aussignargues, Zarzycki, Cai, & Sutter, 2018). Protein organelles are functional analogues of eukaryotic membrane organelles. A semi-permeable protein shell creates a sequestered reaction space separated from the bulk cytosol (Kerfeld & Erbilgin, 2015). This compartmentalization strategy can increase the local concentrations of enzymes and metabolites (Iancu et al., 2010; Ting et al., 2015), prevent the leakage of toxic or volatile intermediates (Bobik, Lehman, & Yeates, 2015) and create unique microenvironments with regard to pH, redox state and cofactor pools (Figure 3b,c; Kerfeld & Melnicki, 2016). Protein organelles enable specialized biochemistry that would not be possible without compartmentalization and are so far known to be involved in carbon fixation (Kerfeld & Melnicki, 2016), carbon source utilization (Axen, Erbilgin, & Kerfeld, 2014), iron metabolism (Bobik et al., 2015), and stress resistance (Nichols, Cassidy-Amstutz, Chaijarasphong, & Savage, 2017). The two main classes of microbial protein organelles are encapsulin nanocompartments and bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) (Bobik et al., 2015; Kerfeld et al., 2018; Nichols et al., 2017). In both cases, specialized enzymatic machinery is selectively encapsulated within a self-assembling protein shell. Genes encoding shell proteins and the enzymatic core cluster together and are organized in co-regulated operons (Axen et al., 2014; Bobik et al., 2015; Giessen, 2016). The fact that protein organelle structure and function are genetically encoded, which is not the case for lipid-based organelles, makes them highly engineerable and promising starting points to build designed compartmentalization systems in a synthetic cell context (Giessen & Silver, 2016a).

FIGURE 3.

Protein organelles and LLPS for designing compartmentalization in synthetic cells. (a) The two known classes of protein organelles, encapsulin nanocompartments (Encs), and bacterial microcompartments (BMCs). (b) Potential problems for enzymes and pathways arising without compartmentalization. (c) The advantages of compartmentalizing metabolic pathways. (d) Integration of different types of designed and modular protein-based compartmentalization systems for optimizing synthetic cell metabolism

3.2 |. Bacterial microcompartments

BMC operons are widely distributed in bacteria and can be found in the majority of bacterial phyla (Axen et al., 2014). BMCs assemble into large cytosolic protein compartments with diameters between 40 and 500 nm composed of a selectively permeable protein shell and an enzymatic core (Tanaka et al., 2008; Cléement Aussignargues, Paasch, Gonzalez-Esquer, Erbilgin, & Kerfeld, 2015; Sutter, Greber, Aussignargues, & Kerfeld, 2017). BMC shells generally consist of 3 types of small proteins that form hexameric, pseudo-hexameric, and pentameric complexes representing individual facets which self-assemble to form the overall BMC shell. BMCs specifically sequester specialized enzymes and are involved in the anabolic fixation of carbon (carboxysomes) and catabolic processes like carbon and nitrogen source utilization (e.g., 1,2-propanediol (PDU), ethanolamine (EUT), choline, l-fucose; Herring, Harris, Chowdhury, Mohanty, & Bobik, 2018; Kerfeld, 2017; Petit et al., 2013; Turmo, Gonzalez-Esquer, & Kerfeld, 2017). All known catabolic BMCs, also known as metabolosomes, encapsulate enzymatic pathways that proceed through toxic aldehyde intermediates and it has been proposed that the compartment shell protects the rest of the cell from these toxic intermediates (Chowdhury, Sinha, Chun, Yeates, & Bobik, 2014). Metabolosomes have been suggested to provide bacteria with competitive advantages in complex environments and have been shown to be important for the virulence of some widespread pathogens like Salmonella typhimurium (Harvey et al., 2011; Klumpp & Fuchs, 2007; Thiennimitr et al., 2011) and Clostridium difficile (Bhardwaj & Somvanshi, 2017; Pitts, Tuck, Faulds-Pain, Lewis, & Marles-Wright, 2012). Recent bioinformatic searches have revealed dozens of uncharacterized BMC systems with unknown functions encoded in human-associated bacteria (Axen et al., 2014).

BMCs have recently attracted the attention of protein engineers and synthetic biologists as modular engineerable systems with which to control protein and even pathway compartmentalization with the ultimate goal of building designer nano-bioreactors (Plegaria & Kerfeld, 2018; Planamente & Frank, 2019; M. J. Lee, Palmer, & Warren, 2019). So far, most studies aimed at engineering BMCs have been carried out in vivo. One important prerequisite for BMCs to be useful tools in cell-free and synthetic cell settings is the ability to decouple the formation of separated spaces, that is, shell formation, from the natively associated enzymatic cargo. This has been achieved through the co-expression of shell components for a number of systems including PDU, EUT, and b-carboxysome BMCs resulting in the in vivo assembly of empty BMC-like shells (Cai, Bernstein, Wilson, & Kerfeld, 2016; Choudhary, Quin, Sanders, Johnson, & Schmidt-Dannert, 2012; Lassila, Bernstein, Kinney, Axen, & Kerfeld, 2014; Mayer et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2010). By combining shell components from different BMC systems, it is also possible to form chimeric BMC shells (Cai, Sutter, Bernstein, Kinney, & Kerfeld, 2015; Fang et al., 2018).

The second prerequisite needed to make BMCs useful tools for synthetic biology is a modular targeting mechanism for selectively localizing arbitrary protein components inside a BMC shell (E. Y. Kim & Tullman-Ercek, 2014). Non-native enzymes can be directed to the BMC interior by genetic fusion of so-called encapsulation peptides (EPs) found either at the N- or C-termini or internal regions of an enzymatic core component (Jakobson, Kim, Slininger, Chien, & Tullman-Ercek, 2015). EPs are generally amphipathic helices and EPs from different BMC systems can often be used interchangeably due to a conserved interaction mechanism. The main drawbacks of using native EPs to target heterologous cargo are their low targeting efficiency and lack of control over stoichiometry (E. Y. Kim & Tullman-Ercek, 2014). This has led to the development of alternative targeting strategies, including rational design and library-based screening of de novo EPs, orthogonal covalent systems like the SpyTag/SpyCatcher targeting system based on split bacterial adhesin domains, and split inteins (Zakeri et al., 2012; Y. Li, 2015; Hagen, Sutter, et al. 2018).

A third prerequisite that needs to be considered is gaining control over BMC shell permeability which controls matter and information exchange between the BMC interior and the bulk cytosol. All BMCs possess distinct pores at the center of their (pseudo)-hexameric and pentameric facets. Two approaches have been used to modulate the permeability of BMCs. First, the residues lining the pores can be altered to change the size, charge, or hydrophobicity of a given pore (Slininger Lee, Jakobson, & Tullman-Ercek, 2017). Second, chimeric facets can be created by combining shell protein monomers from different BMC systems (Cai et al., 2015). Additionally, de novo designed iron-sulfur cluster binding sites have been engineered in heterologous BMC pores which may allow future control over electron transfer into and out of BMCs (Clément Aussignargues et al., 2016). Applying the principles discussed above, BMCs have been repurposed for a number of novel functions including the encapsulation of a non-native two-enzyme metabolic pathway for increased ethanol production in a heterologous host (Lawrence et al., 2014). Engineered BMCs have further been employed for polyphosphate accumulation and enhanced safe expression of toxic proteins (Liang, Frank, Lünsdorf, Warren, & Prentice, 2017; Yung, Bourguet, Carpenter, & Coleman, 2017).

While BMC engineering has been primarily carried out in vivo, some advances have been made on in vitro assembly. A major issue for in vitro reconstitution of BMC shells is the tendency of all individual shell components to self-associate, preventing their easy purification. A number of studies were able to counteract self-association via fusion tags (His6 and SUMO) which allowed purification of individual shell proteins (Lassila et al., 2014; Uddin, Frank, Warren, & Pickersgill, 2018; Hagen, Plegaria, et al. 2018). Upon mixing them in defined stoichiometries followed by tag removal, BMC-like closed shells as well as protein nanotubes could be formed. Notably, in vitro assembled BMC shells are generally smaller than native BMCs, indicating that cargo proteins are important for determining shell dimensions. The importance of relative protein ratios and stoichiometry is further highlighted by the fact that many higher-order and extended architectures can be observed when heterologously expressing BMCs in vivo or assembling them in vitro. These include flat sheets, tubes, filaments, and swiss-roll like structures (Choudhary et al., 2012; Dryden, Crowley, Tanaka, Yeates, & Yeager, 2009; Heldt et al., 2009).

Currently, a number of major challenges exist which preclude the easy use of BMCs in cell-free contexts. BMCs are many megadalton in size and their shells are often made up of between 3 and sometimes more than 10 components. Formation of closed BMC-like shells relies on the precise control over relative protein ratios, otherwise aberrant and nonclosed structures will be formed. This can be addressed by developing cell-free systems where the relative expression levels of many components (shell and cargo) can be precisely controlled. Another useful future strategy will be the removal of redundant shell components to build more streamlined minimal shell systems. This will allow the controlled assembly of very large shells acting as genetically encoded sub-compartments in cell-free systems and synthetic cells.

3.3 |. Encapsulin nanocompartments

Recent genome-mining studies have shown that encapsulin operons are widely distributed in bacterial and archaeal genomes (Giessen & Silver, 2017a; Tracey et al., 2019). Encapsulins self-assemble into icosahedral protein compartments between 20 and 50 nm in diameter and are able to selectively encapsulate cargo enzymes involved in specialized metabolic functions (Akita et al., 2007; McHugh et al., 2014; Sutter et al., 2008). Encapsulin shells consist of a single type of shell protomer and cargo encapsulation is mediated by short C-terminal sequences found in all cargo proteins called targeting peptides (TPs) (Cassidy-Amstutz et al., 2016; Tamura et al., 2015). Encapsulin capsid proteins possess the HK97 phage-like fold and most likely originate from defective prophages whose capsid components have been co-opted by host metabolism (Giessen & Silver, 2017a; Nichols et al., 2017). This molecular domestication of a viral capsid-forming shell protein by microbes represents an intriguing example of the evolutionary entanglement of viral and cellular protein folds. Encapsulin systems have been implicated in oxidative and nitrosative stress resistance, iron and redox homeostasis, and the biosynthesis or degradation of so far uncharacterized metabolites (Contreras et al., 2014; Giessen & Silver, 2017a; Nichols et al., 2017; Rahmanpour & Bugg, 2013).

So far, no study producing encapsulins in a cell-free system has been published with most of the encapsulin engineering work having been done in vivo (Giessen, 2016; Giessen & Silver, 2017b). Similar to BMCs, encapsulins represent promising systems for controlled compartmentalization of proteins and enzymatic pathways as well as engineered spatial control at the molecular level. Targeting of non-native cargo proteins to the interior of encapsulins has been reported multiple times by genetic fusion of TPs to proteins of interest (Cassidy-Amstutz et al., 2016; Choi, Kim, Choi, & Kang, 2018; Künzle, Mangler, Lach, & Beck, 2018; Lau, Giessen, Altenburg, & Silver, 2018; Tamura et al., 2015). Various non-native protein fusions to either the N- or C-terminus of the encapsulin capsid protein have been reported resulting in the encapsulation or external display of a fused protein of interest. These engineered encapsulin systems have been used in a number of biotechnological and biomedical applications including targeted drug delivery and synthesis (Bae et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2016; Lee, Carpenter, D’haeseleer, Savage, & Yung, 2020; Moon, Lee, Min, & Kang, 2014; Sonotaki et al., 2017) biomaterials and nanoparticle synthesis (Giessen & Silver, 2016b; Künzle et al., 2018), vaccine design (Lagoutte et al., 2018), nano-bioreactors for improved biocatalysis (Lau et al., 2018; Putri et al., 2017) and subcellular labelling reagents (Sigmund et al., 2018, 2019). Further, encapsulin pores, found at the five- and threefold symmetry axes of the icosahedral shell, have been engineered to modulate shell permeability (Williams, Jung, Coffman, & Lutz, 2018).

The fact that encapsulin shells are able to assemble into closed structures from a single type of shell protein makes it more straightforward to use them in in vitro settings compared to BMCs. Reversible in vitro assembly and disassembly of encapsulins has been achieved based on pH shifts (Cassidy-Amstutz et al., 2016). This is encouraging for potential future applications of encapsulins as dynamic stimulus-responsive compartmentalization systems in cell-free and synthetic cell systems. Even though encapsulin self-assembly in cell-free systems has not yet been reported, other protein compartments of similar size and complexity have been successfully expressed and assembled using bacterial cell-free systems. This includes the cell-free production of T7, ΦX174, and MS2 bacteriophage capsids which share many features with encapsulin shells (Garamella, Marshall, Rustad, & Noireaux, 2016; Shin, Jardine, & Noireaux, 2012).

Overall, encapsulins face fewer hurdles than BMCs with regard to their application in synthetic cells primarily due to their smaller size and more straightforward cargo loading and assembly pathways. Ideally, both encapsulins and BMCs will be used in parallel in future synthetic cell systems to provide genetically encoded and dynamic compartmentalization strategies that span several orders of magnitude of volume (20–500 nm in diameter).

3.4 |. Liquid–liquid phase separation and membraneless protein organelles

In recent years, there is mounting evidence that liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) represents a key cellular mechanism for the formation of membraneless protein compartments (Hyman, Weber, & Jülicher, 2014). The liquid nature of protein- and RNA-rich compartments was first established in P granules found during germ cell specification in Caenorhabditis elegans (Brangwynne et al., 2009). The drivers of LLPS in many cases involve intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or regions (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015). For instance, both LAF-1 and PGL-3, which are P granule proteins, contain arginine/glycine-rich (RGG) domains which are necessary and sufficient for LLPS (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015; Saha et al., 2016). LLPS observed in membraneless compartments has been recapitulated biochemically using purified proteins in vitro (P. Li et al., 2012; Molliex et al., 2015; Jain & Vale, 2017; Schuster et al., 2018; Du & Chen, 2018), making it another promising experimental platform to explore approaches for organizing intracellular activity in synthetic cells. Encapsulation of a two-phase system in a synthetic cell context was first demonstrated many years ago using dextran and PEG solutions where their mixing/demixing is controlled by concentration or temperature (Long, Jones, Helfrich, Mangeney-Slavin, & Keating, 2005). With increasing appreciation of LLPS in biological organization, recent studies have shown that formation of protein-rich condensates can support bacterial cytoskeleton dynamics or enzymatic polymerization of nucleic acids (Deshpande et al., 2019; Monterroso et al., 2019). Coacervate droplets have been repurposed as artificial organelles for spatial organization of bio-reactions and incorporating LLPS as artificial organelles in synthetic cells is a frontier of current synthetic cell research (Crowe & Keating, 2018; Deng & Huck, 2017). Recently, protease-triggered assembly and disassembly of RGG-based protein droplets has been demonstrated as well (Schuster et al., 2018). Other recent examples of dynamically controlling compartmentalization in cell-free liposome-based systems rely on the pH-responsiveness of polylysine/adenosine triphosphate or spermine/RNA to dynamically form single coacervate droplets within lipid vesicles (Last, Deshpande, & Dekker, 2020). In one study, the enzyme formate dehydrogenase was shown to partition and concentrate within these liquid–liquid phase separated droplets which led to a concentration-based activation of enzyme activity (Love et al., 2020).

By integrating protein shell- and liquid condensate-based approaches for the spatial and temporal control of biochemical reaction networks in synthetic cells (Figure 3d), it will be possible in the future to create a general platform technology adaptable to investigate and engineer many aspects of synthetic cell metabolism. This will not only allow novel insights into how compartmentalized spaces at the nanoscale facilitate the proper functioning of natural cells, but also the creation of programmable synthetic cells for applications as nanoreactors and production platforms, biosensors, delivery devices, and building blocks for biomimetic materials.

4 |. SELF-ORGANIZATION, POSITIONING, AND DYNAMICS

A fascinating feature of living cells is their ability to self-organize and position molecules in space and time. In the following section, we describe several reconstitution systems related to bacterial chromosome organization, segregation, and cell division that are particularly attractive in the context of synthetic cell research.

4.1 |. Chromosomal organization

Bacterial chromosomes are typically orders of magnitude longer than their cellular confines. Physical and biochemical processes organize chromosomes into a compact, but accessible nucleoid (Jun, 2015). Polymer dynamics of the chromosome provides ~100-fold compaction by molding it into a globule (Surovtsev & Jacobs-Wagner, 2018). Cellular confinement, crowding, and excluded volume effects further aid in compaction (Cunha, Woldringh, & Odijk, 2001; Murphy & Zimmerman, 1997; Odijk, 1998). DNA supercoiling by topoisomerases is also essential in sustaining a compact yet accessible genome. Nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) are key to compacting and organizing bacterial chromosomes. NAPs are functionally analogous to eukaryotic histones, compacting the chromosome by kinking and bridging the DNA (Amit, Oppenheim, & Stavans, 2003; Dame, Noom, & Wuite, 2006; Thompson & Landy, 1988). Structural maintenance of chromosome (SMC) complexes are also of critical importance, and likely function by co-entrapment of DNA loops within the circumference of the SMC ring (Gligoris et al., 2014). In many bacteria, a single SMC complex is sufficient for normal growth of cells (Hutchison et al., 2016).

The molecular mechanism underlying SMC-based chromosome compaction has remained elusive. Recently, the Dekker group provided direct visualization of an SMC complex forming and processively extruding DNA loops in a cell-free setup using purified components (Ganji et al., 2018; E. Kim, Kerssemakers, Shaltiel, Haering, & Dekker, 2020). These studies are significant steps forward in the bottom-up reconstitution of chromosome compaction. An attractive next step would be to combine circular DNA molecules with SMC complexes and topoisomerases within liposomes. Such experiments would determine if physical processes (polymer dynamics, confinement, and crowding) combined with supercoiling and SMC-based looping are necessary and sufficient in the formation of a minimal nucleoid.

4.2 |. DNA segregation

Prior to cell division, replicated DNA must be segregated and positioned to opposite sides of the cell to ensure faithful genetic inheritance. Many bacterial chromosomes and plasmids employ partition (Par) systems. Par systems are minimal and self-organizing, encoding a cis-acting DNA-binding site on the chromosome (or plasmid) and two trans-acting proteins (Baxter & Funnell, 2014). The DNA-binding site is bound by one protein, while the other protein is an NTPase that uses ATP or GTP hydrolysis to drive the segregation reaction. Par systems are grouped according to the NTPase type—whether it contains a Walker ATP-binding motif (ParA), or is structurally similar to eukaryotic actin (such as ParM) or tubulin (such as TubZ; Gerdes, Howard, & Szardenings, 2010). All three types have been reconstituted and imaged in cell-free setups using purified and fluorescently labeled components.

The ParM system and its polymer-based mechanism for segregating DNA is well understood because of cell-free reconstitution data that correlates strongly with in vivo function and dynamics. Through a mechanism of insertional polymerization, ParM filaments push plasmids to opposite cell poles in vivo (Møller-Jensen et al., 2003). In a cell-free setup, ParM undergoes ATP-dependent polymerization; pushing apart beads coated with the partner protein (ParR) bound to its cognate DNA-binding site (parC) (Garner, Campbell, & Dyche Mullins, 2004; Garner, Campbell, Weibel, & Dyche Mullins, 2007). TubZ polymers have also been reconstituted (Fink & Löwe, 2015) and show dynamic instability (Erb et al., 2014) and treadmilling (Larsen et al., 2007) in the presence of GTP.

ParA-based systems are encoded by 70% of all sequenced bacterial chromosomes and also found on most low copy plasmids (Baxter & Funnell, 2014). Studies on plasmid partitioning have been particularly useful in elucidating the ParA-based mechanism. In vivo, the ParA ATPase coats the nucleoid, while its partner protein, ParB, binds and spreads from its DNA-binding site (parS) on the plasmid. The ParB-parS complex stimulates the release of ParA proteins from the nucleoid in the vicinity of the plasmid, resulting in a concentration gradient of ParA. Following replication, plasmid copies segregate as they chase the ParA gradient in opposite directions. This gradient-based mechanism ensures that each daughter cell inherits the plasmid after division. Gradient-based mechanisms for ParA-based chromosome segregation have also been proposed (Le Gall et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2014; Walter et al., 2017).

The Mizuuchi group reconstituted ParA-based DNA segregation, movement, and positioning using purified and fluorescently labeled components imaged on a DNA-carpeted flow cell, which served as a biomimetic of the nucleoid (Hwang et al., 2013; Vecchiarelli, Hwang, & Mizuuchi, 2013; Vecchiarelli, Neuman, et al., 2014). Purified and fluorescently labeled variants of ParA and ParB were mixed with either plasmid or DNA-coated beads containing the parS binding site. Similar to in vivo dynamics, ParA coated the DNA carpet and its concentration was depleted in the vicinity of ParB-bound plasmid or bead substrates. These “DNA-cargoes” utilized the ParA gradient on the DNA carpet for directed movements.

4.3 |. Positioning cell division

Cell division machinery in bacteria can be positioned by several positive and negative regulators (Monahan, Liew, Bottomley, & Harry, 2014). But to date, only the Min/FtsZ system has been reconstituted. The Min system acts on a tubulin-like GTPase called FtsZ; a highly conserved protein among bacteria and also found in chloroplasts and mitochondria (Chen, MacCready, et al., 2018; Leger et al., 2015). FtsZ is the most extensively studied protein involved in the division of a bacterial cell (den Blaauwen, Hamoen, & Levin, 2017). FtsZ polymerizes into a structure called the Z ring. The Z ring (i) acts as a scaffold for the recruitment and assembly of several other division proteins, (ii) contributes to the invagination force, and (iii) organizes cell wall remodeling during septation (den Blaauwen & Luirink, 2019). FtsZ does not directly bind to the membrane but depends on adaptor proteins such as FtsA and ZipA. In the presence of GTP, treadmilling FtsZ polymers have been reconstituted on supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) using its native membrane anchors FtsA and ZipA (Pazos, Natale, & Vicente, 2013; Rico, Krupka, & Vicente, 2013). FtsZ and FtsA have also been shown to form helical co-polymers that mechanically constrict liposomes and generate narrow necks, but complete division did not occur (Szwedziak, Wang, Bharat, Tsim, & Löwe, 2014). Very recently, FtsA-FtsZ ring-like structures were reconstituted by way of a cell-free gene expression system both on planar membranes and inside liposome compartments (Godino et al., 2019; Godino et al., 2020). The “cytoskeletal structures” were found to constrict the membrane and generate a few budding vesicles. How to faithfully generate robust division events via an FtsZ-based mechanism in a liposome remains unclear.

The Min system consists of three proteins that self-organize into a cell pole-to-cell pole oscillator on the inner membrane, which aligns Z-ring assembly at mid-cell by preventing FtsZ polymerization at the cell poles (Szwedziak & Ghosal, 2017). MinD, when bound to ATP, associates with the inner membrane (Hu & Lutkenhaus, 2003; Zhou & Lutkenhaus, 2003). MinE also has membrane-binding activity and can interact with membrane-bound MinD (Hu, Gogol, & Lutkenhaus, 2002; Vecchiarelli et al., 2016). MinE interactions with MinD have been shown to recruit, stabilize, release, and inhibit MinD interactions on the membrane (Mizuuchi & Vecchiarelli, 2018). This dynamic interplay between MinD and MinE results in a pole-to-pole oscillation on the membrane (Raskin & De Boer, 1999). The third protein, MinC, is not required for oscillation, but is the inhibitor of Z-ring assembly (Lutkenhaus, 2007). MinC acts as a passenger protein, associating with MinD on the membrane and inhibiting FtsZ polymerization. The pole-to-pole oscillation of MinD therefore recruits the inhibitory activity of MinC at the poles, which promotes Z-ring formation and symmetric cell division at mid-cell.

The Min system has been shown to form a wide-variety of patterns when unleashed from cellular confines (Figure 4a) and reconstituted in a variety of cell-free formats (Caspi & Dekker, 2016; Kretschmer, Zieske, & Schwille, 2017; Loose, Fischer-Friedrich, Herold, Kruse, & Schwille, 2011; Loose, Fischer-Friedrich, Ries, Kruse, & Schwille, 2008; Kohyama, Yoshinaga, Yanagisawa, Fujiwara, & Doi, 2019; Martos, Petrasek, & Schwille, 2013; Ramm, Glock, & Schwille, 2018; Schweizer et al., 2012; Vecchiarelli et al., 2016; Vecchiarelli, Li, et al., 2014; Zieske & Schwille, 2014): (i) open-well and flow-channel microfluidics, (ii) E.coli extracts and synthetic lipid mixtures of defined composition, (iii) SLBs and liposomes, and (iv) various 2D and 3D confinement geometries. In these setups, the biochemistry driving Min patterning can be visualized. MinD and MinE mutants, changes in protein concentration and stoichiometry, and changes in buffer conditions (i.e., salt concentration and molecular crowding) have allowed for the development of comprehensive molecular mechanisms.

FIGURE 4.

Examples of Min/FtsZ system reconstitutions. (a) MinD and MinE have been shown to form a variety of patterns when reconstituted in cell-free setups. In this example, GFP-MinD (cyan) and MinE-Alexa647 (magenta) were preincubated with ATP and infused into a flowcell coated with a SLB. Still images show the different types of patterns supported by the decreasing protein density in the flowcell from inlet to outlet. Adapted with permission from (Mizuuchi & Vecchiarelli, 2018). (b) Reconstitution of Min oscillations in a rod-shaped trough has been shown to confine FtsZ-YFP-MTS polymerization to the middle of the compartment. Adapted from (Zieske & Schwille, 2014) under the CC BY 4.0 license

The Schwille group has reconstituted the entire Min/FtsZ system in rod-shaped, lipid-coated troughs that mimic the geometry of an E. coli cell (Zieske & Schwille, 2014). In this cell-free setup, a fluorescent version of FtsZ was fused to a membrane targeting sequence (FtsZ-YFP-mts), which allowed FtsZ to directly bind membrane, bypassing the need for membrane recruitment by FtsA and ZipA. Strikingly, the pole-to-pole oscillation of the MinCDE system restricted Z-ring assembly to the mid-point of the rod-shaped trough (Figure 4b). The reconstitution of the Min oscillator inside free-standing lipid vesicles was recently achieved (Godino et al., 2019; Litschel, Ramm, Maas, Heymann, & Schwille, 2018). Litschel et al encapsulated purified MinE and fluorescent MinD into vesicles 5–100 μm in diameter, which allowed for precise control of the relative and absolute concentrations of Min components. Godino et al., on the other hand, synthesized MinD and MinE de novo in vesicles 1–20 μm in diameter using the PUREfrex2.0 TX-TL system. A purified fluorescent fusion of the MinC protein was also added at a fixed concentration. As a result, the absolute and relative concentrations of all three proteins were highly variable for experiment-to-experiment. But in both cases, the Min system was observed to form patterns that are similar to those formed on SLBs: pulsing vesicles (global binding and release from the membrane), pole-to-pole oscillation, circling waves, and trigger waves. Intriguingly, vesicle shape oscillations were also observed, and in some cases, these deformations led to periodic vesicle splitting. This finding suggests that it may be possible to divide a liposome-based synthetic cell via “budding” induced by Min oscillations, and without FtsZ. Godino et al. (2020) in a separate publication, were also recently successful in cell-free gene expression of FtsZ-FtsA ring-like structures that could constrict liposomes; generating elongated membrane necks and, on occasion, budding vesicles. To date, however, these stepwise additions of divisome components have yet to show consistent abscission of liposomes. The next important step is to combine the Min/FtsZ system (MinCDE with FtsZ and one or more of its membrane anchors such as FtsA) into a liposome. Additional downstream division proteins are likely required for reconstituting an FtsZ-based division machine from scratch.

5 |. SCALES IN TIME AND SPACE

Cells operate over an astounding range of scales in both time and space. From nanoscale enzymes that catalyze reactions in microseconds to micron-sized cells that divide in tens of minutes, cellular life is as versatile as it is complex. Therefore, designing synthetic cells poses the unique challenge of reproducing processes at this breadth of spatio-temporal scales. In what follows, we will review the recent achievements in the reconstitution of cellular processes and point out how they contribute to achieving a multiscale functioning synthetic cell. Then, we will discuss the integration of these processes and the crucial role of modeling in the endeavor of engineering synthetic cells.

5.1 |. Time

Cells are intrinsically dynamic across a large range of temporal scales (Figure 5). On the fast end (fractions of a second to a few minutes), macromolecular interactions and post-translational modifications serve as a platform for cellular signaling. On the slow end (hours to days), biomolecular networks, including gene regulation networks and metabolic networks, coordinate to fulfill essential functions like cell cycles, metabolism, and multicellular aggregation. A key challenge in designing a comprehensive synthetic cell is to construct self-organizing processes that couple both slow and fast timescales to provide versatile while accurate performance. Over the last decade, scientists have begun to achieve the reproduction of certain biological processes spanning a considerable range of cellular dynamics (Figure 5). Below, we will review recent synthetic cell research focusing on cell cycle and division, metabolism, multicellularity, and scalability.

FIGURE 5.

Several temporal scales involved in biological cells (left) and synthetic cells (right). The in vitro reconstituted phenomena range from oscillations with multi-second periods up to multicellular structures whose aggregation unfolds in the order of days. In between, temporal scales range from metabolic processes that can be sustained for several hours, the oscillations of coupled micro-compartments, the formation of self-organized structures in Xenopus laevis egg extracts, and the fast timescale response of the engineered phosphorylation regulatory networks. Some illustration images in were created with BioRender.com

The cell cycle is a fundamental self-organizing process that governs when a cell is to divide. The temporal length between two successive divisions can vary from tens of minutes in bacteria and some eukaryotic cells including yeast and early embryonic cells, to about a day in somatic cells. Unlike binary fission of how most prokaryotes divide, eukaryotic cell cycle is regulated by a more sophisticated regulatory network that may involve hundreds of genes, proteins, and signaling molecules (e.g., KEGG human cell cycle pathway: hsa04110), making it difficult to reproduce the process from scratch. Different strategies have been applied to mimic both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell cycle oscillations and divisions in synthetic cells. As aforementioned in Section 4.3, using a cell-free TX-TL system known as PURE (Shimizu et al., 2001), a Min oscillatory system has been integrated with the cytoskeletal proteins to dynamically regulate FtsZ patterns, as a way to regulate the prokaryotic cell division in vitro (Godino et al., 2019). The oscillation, at a period of 25 s, was observed for up to 6 hr. Utilizing Xenopus laevis egg cytoplasm with recombinant proteins, mRNAs, and DNA, a self-sustained eukaryotic cell cycle has also been reconstituted in cell-sized water-in-oil microemulsion droplets in both cytosolic-only and nuclei-assembled forms (Guan, Wang, et al. 2018; Guan, Li, et al. 2018; Sun, Li, Wang, Maryu, & Yang, 2019). The cell cycles in microdroplets featured a period tunable from tens to hundreds of minutes and lasted for several days. Additionally, in a 2D chamber environment, the cycling egg cytoplasm supplied with sperm DNA self-organizes into cell-like compartments that display mitotic divisions at each cell cycle (Cheng & Ferrell, 2019). These cell-like in vitro microenvironments, comparing to biological cells, have a great flexibility in circuit dissection, speed tuning, and manipulation of concentration, stoichiometry, size, nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, energy, and so on, providing a powerful platform for quantitative characterization of cell-cycle machinery. Despite these advantages, most cell-cycle reconstructions so far relied on cell-extracted materials (e.g., cytosol, sperm chromatin, etc.) that are still too complex to gain insight into a minimal design for the self-organizing process. An interesting next step in bottom-up synthetic biology is to reconstruct a cell cycle completely from scratch. Computational studies have shown that even with complicated biological clock networks, a minimal core architecture is sufficient for self-sustained oscillations, while those evolutionary-conserved peripheral network structures may provide additional modifications to promote functions such as robustness (Z. Li, Liu, & Yang, 2017) and tunability (Tsai et al., 2008). Indeed, a landmark study has successfully reconstituted a temperature-compensated bacterial circadian clock in a test tube with components as simple as three Kai proteins and ATP (Nakajima et al., 2005), exemplifying a minimal design of a circadian clock. Constructing a minimal cell-cycle circuit from the bottom-up, for instance, starting from a set of hypothetical central mitotic regulators including cyclin B1, cyclin dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1), and anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), can not only test our existing understanding of the core architecture but also serve as a foundation with auxiliary structures added one at a time, a step forward toward a synthetic cell with well-predicted cell-cycle functions. A foreseeable challenge of building a bottom-up out-of-equilibrium system like cell cycles is to self-sustain energy. Incorporation of metabolic cycles with cell cycles can be an additional interesting goal in this direction. In the paragraph below, we will review the recent effort in building machinery to replenish energy as well as other consumable components.

Metabolism is another cornerstone process in living systems. The central challenge is to achieve bottom-up integration of sustainable metabolic functions in synthetic cells. Two important studies achieved this result: one using E. coli inverted membrane vesicles to create a minimal metabolism containing an NAD reaction and an NAD-regeneration module (Beneyton et al., 2018), and the other creating light-driven artificial organelles by proteoliposomes formed of bacteriorhodopsin and ATP synthase to allow photo-synthesizing ATP inside a giant unilamellar vesicle (GUV) (Berhanu et al., 2019). Both systems were able to function autonomously for hours. The presence of metabolic activity is considered a key factor in discerning between living and nonliving matter. Refilling energy and other cellular consumables (e.g., lipid membranes, see Section 5.2) is important for an autonomously functioning and growing synthetic cell. Studies that have thus far implemented a few different sustaining machineries like NAD and photosynthetic pathways are the beginning steps by synthetic biologists into this exciting field. Moreover, the design of repair mechanisms as well as routes for the elimination of byproducts, appear to be future challenges in this area of research. Finally, greater integration between these cyclic biochemical processes and other physical and mechanical activities can serve as a way to further empowering a synthetic cell for controlling its own life cycle.

Besides reproducing intracellular processes, it is also important to emulate the higher-order intercellular interactions observed among biological cells. Applying engineered regulatory networks and synthetic signaling pathways, studies have achieved multicellularity or cell–cell communications through various strategies. Examples include programming synNotch signaling for cell adhesion and multicellular structures (Toda, Blauch, Tang, Morsut, & Lim, 2018), engineering genetic circuit-containing synthetic minimal cells (synells) to enable liposome interaction and fusion (Adamala, Martin-Alarcon, Guthrie-Honea, & Boyden, 2017), creating quorum sensing machinery in phospholipid vesicle-based artificial cells (Lentini et al., 2017), and communicating nonlipid microcapsules through DNA strand displacement (Joesaar et al., 2019). However, all these processes need to be responsive to an ever-changing environment. Typically, cells sense inputs that are transduced by signaling pathways which ultimately change the expression level of a group of genes. Therefore, it is important to comprehensively study the connection between long-timescale responses and short-timescale input sensing. Using motifs called phospho-regulons to create a dual-timescale regulatory network, cell responses can be controlled, and tuned over a wide dynamic range (Gordley et al., 2016). Despite efforts of the synthetic biology community to standardize biological parts, rational design of transcription factors remains challenging. To overcome this issue and to promote scalability and modularity, a workflow for an exhaustive characterization of transcription factors was recently presented (Swank, Laohakunakorn, & Maerkl, 2019) and an integrated regulatory network with multiple functional modules was created (Schaffter & Schulman, 2019).

Different processes have been reproduced in vitro across the relevant timescales of cellular life (Figure 5). However, in a biological cell all these processes need to run in parallel cooperatively. Therefore, moving forward, two avenues of research will probably thrive in the field of synthetic cells. On the one hand, new processes and modules will be built to enrich the existing arsenal of building blocks. On the other hand, the readily available building blocks will be integrated to achieve increasingly complex cellular behaviors. Importantly, the accomplishments in the time domain of synthetic cells have to be mirrored by similar developments in the spatial domain.

5.2 |. Space

From molecules (~nm) to developing eggs (~μm to mm), cellular life is a remarkable multi-scale system. Like temporal scales, spatial scales are crucial to cell functions. Dynamics in bulk, usually characteristic of ensemble averages, cannot represent behaviors in single cells. Moreover, certain processes including cell cycles (Guan et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2017) can progress in a size-dependent manner. Therefore, constructing a synthetic cell requires creating micrometric cellular and subcellular compartments filled with components compatible with cellular life (Figure 6). One of the most prominent experimental techniques for achieving these scales is the encapsulation of cellular processes in water-in-oil emulsions and GUVs via microfluidics. Such a platform permits precision, reproducible, and high-throughput generation of encapsulated systems at a wide range of cell-sized and subcellular scales.

FIGURE 6.

A range of spatial scales in natural cellular life (left) and in synthetic cells (right). In the synthetic cell context, nanometric functional compartments have been generated as well as millimeter-sized protein expression patterns. Energy modules were constructed with nanometer-sized proteoliposomes and inverted membranes. Synthetic cells or Synells have also been developed which can interact with each other. Additionally, a plausible mechanism for de novo liposome production was developed yielding compartments of compatible size with biological cells. Subcellular structures and their dependence on cell volume were studied by reconstructing mitotic spindles in droplets. Finally, protein expression patterns, compartments capable of mitosis, and multicellular structures have been produced in relevant spatial scales where eukaryotic cells and tissues operate. Some illustration images in were created with BioRender.com

The versatility of microfluidics allows the creation of micrometric chambers (Swank et al., 2019; Tayar, Karzbrun, Noireaux, & Bar-Ziv, 2017) and cell-like (Pautot, Frisken, & Weitz, 2003) or subcellular mitochondria-like (Beneyton et al., 2018) droplets. These artificial compartments can be further designed to interact with each other via diffusively coupled (Tayar et al., 2017) or signaling-based (Adamala et al., 2017) mechanisms or to harbor key pieces of the prokaryotic division machinery (Godino et al., 2019). Besides direct encapsulation, these techniques can be used to generate droplets-in-droplets structures such that as many as 104 light-harvesting proteoliposomes can be encapsulated inside GUVs (Berhanu et al., 2019). However, compartments produced in most studies have a fixed amount of membrane material. Bearing one ultimate goal of developing a synthetic cell capable of growth and division, it is also critical to create mechanisms for cells to form their own membranes. By engineering a soluble protein system, researchers have made feasible the de novo synthesis of phospholipid membranes (Bhattacharya, Brea, Niederholtmeyer, & Devaraj, 2019). Although this system does not require pre-existing membranes to function, it does need single-chain reactive lipid precursors, amine-functionalized lysolipids, and ATP. Moreover, the current implementation produces vesicles of various sizes and lamellarity in an uncontrolled way with the soluble enzyme Fad10 spontaneously associating with the de novo formed membranes. All these characteristics might pose difficulties for future implementations where controlled liposome composition and type is needed.

Cell size dominates the length scales of cellular life because any other cellular structures have to physically fit inside the cell. Understanding the relationship between subcellular structures and cell dimensions is crucial to build cells with functional subcellular compartments; on the other hand, synthetic cells also provide a uniquely powerful tool to investigate the mechanisms behind such a relationship. For example, the encapsulation of mitotic spindles in vesicles of different sizes showed that the spindle size scales with the compartment’s volume (Good, Vahey, Skandarajah, Fletcher, & Heald, 2013). This points to the mechanisms in which cells sense and control their sizes. Some recent studies exploring this relationship suggested possible venues for implementing such mechanisms in synthetic cell systems. Cells utilize multiple strategies to control and maintain their size such as volume and area sensing (Facchetti, Knapp, Flor-Parra, Chang, & Howard, 2019), but also maintain specific ratios between subcellular structures and the total volume. A prominent example of the latter is the homeostasis of nuclear size relative to cytoplasmic volume (Cantwell & Nurse, 2019a). By extensive screening of the genes involved in aberrant nuclear to cytoplasmic volume ratio, RNA processing, and LINC complexes have been identified to regulate nuclear size. Additionally, different cytoplasmic factors are involved in nuclear size control. In particular, importin-alpha has been indicated as a key component in nuclear size homeostasis (Brownlee & Heald, 2019). For a comprehensive review of the results in this area, see (Cantwell & Nurse, 2019b). Finally, a key player in regulating cell size and shape is the cytoskeleton. A comprehensive review summarizing the recent efforts in cytoskeleton reconstitution in synthetic cells can be found here (Bashirzadeh & Liu, 2019).

Besides micrometric scales, long-range communication and macroscopic pattern formation depend on microscopic rules between cell-sized agents. Therefore, by integrating cellular processes with agent communication, complex behaviors can be achieved such as those observed in biological communities. Moving forward, the homeostasis and size-control of synthetic cells and structures can only be achieved from a thorough understanding of their in vivo counterparts. The integration of processes across the different spatial scales of cellular life will ultimately lead to a complex functioning synthetic cell.

5.3 |. Perspectives on using mathematical modeling for bridging scales

Mathematical and computational modeling is key for studying artificial systems. Modeling can help in the design and explanation of synthetic constructs as well as making predictions that suggest new experiments. Additionally, a goal of synthetic biology is to produce standardized biological parts with robust and reproducible behaviors. Therefore, modeling is one of the main quantitative tools that facilitates the process of constructing synthetic cells.

Traditionally, the dynamics of chemical reactions and gene regulatory networks are described with ordinary differential equations (ODEs). In general, and when copy numbers are high, these models are useful. However, a recurrent problem is the parameterization of large sets of equations. Recently, new methods are used to solve this caveat, such as training a neural network with machine learning algorithms that can significantly improve computational efficiency (Wang et al., 2019). When dealing with small volumes, another branch of modeling becomes more relevant: stochastic modeling. Droplet compartmentalization can introduce partitioning noise that makes data interpretation difficult with ODE models (M. Weitz et al., 2014). In those cases, the stochastic analysis of experimental data becomes indispensable. Also, stochasticity sometimes produces results that are not present in mean-field ODE descriptions. For example, stochastic Turing patterns are studied and long-range order is found in regions of parameter space where a deterministic version of the model would not produce patterns (Karig et al., 2018).

When constructing a synthetic cell, the integration of spatially heterogeneous processes at different scales is a challenging task. The aforementioned tools typically work under assumptions of well-mixed reactions with single time/space discretization These gaps can be filled using two modeling approaches, namely, agent-based models (ABMs) and multiscale modeling. ABMs naturally include the heterogeneities of cellular processes while providing a framework for exploring agent-based rules. Importantly, large-scale behaviors and patterns can be studied as a function of cell–cell interaction rules. Multiscale modeling, instead, explicitly integrates simulations across the different temporal, spatial, and functional scales involved in a complex multiscale system. Using different levels of resolution in the same model, these techniques allow the observation of behaviors across multiple scales. For further reading on ABMs and multiscale modeling, please refer to (Gorochowski, 2016) and (Walpole, Papin, & Peirce, 2013), respectively.

Capturing every aspect of cellular life in a single model appears unattainable. However, such an approach might be unnecessary as a model may only need to capture the important characteristics or a phenomenon of interest. If heterogeneities (ABMs), noise (stochastic modeling), dimensions (multiscale approaches), and mean-field behaviors (ODEs) are considered when modeling, effective quantitative descriptions can be constructed to aid in the design of synthetic cell functions that accounts for different time and space scales.

6 |. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In this review article, we described the engineering of synthetic cells as a natural progression of the study of biology by our increased ability to synthesize and manipulate biological components and integrating them into cell-like systems. The field is growing rapidly with creative approaches and new discoveries being generated. We summarize by highlighting some promising directions and also where challenges in synthetic cell research lie.

6.1 |. Challenges and issues to be addressed

A large portion of the research in synthetic biology focuses on genetic networks, leaving the realm of signaling systems less-explored; in particular, communication via post-translational modifications. Tools for engineering signaling systems to better control the relationship between reactions with fast and slow timescales are needed to improve the dynamic range and flexibility in the time domain of synthetic cells.

Protein modifications are one of the challenges with synthetizing signaling systems as compared to genetic systems. Advances in protein engineering and eukaryotic TX-TL systems will help in this direction.

Both 1 and 2 will help in the reconstitution of more complex eukaryotic systems such as an artificial cell cycle system from the bottom-up.

Integrating diverse modules remains a challenge because the cell-free conditions used to optimize the function of one module might not be suitable for another.

Optimizing TX–TL systems is needed for the production of controlled and coordinated expression of multiple protein operons or whole systems of operons at the same time.

Byproduct elimination and substrate/energy replenishment is a critical issue for creating synthetic cells with expanded life cycles and control thereof.

Functional expression of membrane proteins in synthetic cells is still challenging.

Robust control of self-dividing liposomes remains a challenge in the field.

Shape and size control in synthetic cells can be a fruitful challenge to understand both natural mechanisms and synthetic ones.

Methodologies for reliable scale-up of TX-TL systems are needed for all future endeavors.

6.2 |. Opportunities and areas to be further explored

Exciting new approaches toward protein-based compartmentalization and spatial control are on the horizon. In addition to the discovery and engineering of novel natural protein organelles or IDPs involved in LLPS, computational or de novo design of protein compartments and IDPs has recently gained attention (Baker, 2019; Koepnick et al., 2019). Substantial advances have been made with regard to computationally designed protein shells and cages (Bale et al., 2016; Brouwer et al., 2019; Cannon et al., 2020; Hsia et al., 2016). In addition, novel design concepts based on symmetry relationships and metal-mediated assembly have also been achieved (Badieyan et al., 2017; Cannon, Ochoa, & Yeates, 2019; Cristie-David et al., 2019; Cristie-David & Marsh, 2019; Malay et al., 2019). So far, these systems have not been used in a synthetic cell context or as functional protein organelles with enzymatic cargo. The widespread adoption of de novo designed protein compartments will necessitate developing specific mechanisms with which to easily target arbitrary protein components to their interior. Another current limitation lies with the difficulty of designing protein shells larger than about 40 nm. IDPs represent even more challenging targets for computational protein design due to substantial limitations in our basic understanding of how IDP sequence is connected to structure, dynamics, and ultimately function. However, some progress has been made with computationally designing IDPs (Cohan, Ruff, & Pappu, 2019; Holehouse, Das, Ahad, Richardson, & Pappu, 2017; Schramm, Lieutaud, Gianni, Longhi, & Bignon, 2017; Staller et al., 2018). Future advances in computational protein design and engineering have the potential to address the issues raised above and yield more advanced and tailor-made protein components for controlling compartmentalization in cell-free systems and synthetic cells.

Although DNA is typically used as the information carrier, there are new ways to integrate DNA as part of synthetic cell architecture. Recently, a DNA-based cortex was incorporated into giant vesicles, endowing them with significantly higher mechanical stability toward osmotic shock (Kurokawa et al., 2017). Additionally, the powerful toolbox of DNA origami promises to enable the creation of structures supporting the membrane or even shaping the compartment (Dong et al., 2017; Noireaux & Liu, 2020). The use of DNA as a structural material can extend our degree of control on the shape of synthetic cells and improve the flexibility in the range of stresses and stimuli they can withstand and respond to.

Many of the self-organizing principles required for a synthetic cell have been reconstituted to varying degrees. However, the buffer conditions, protein concentrations, and technical approaches (i.e., microfluidic methodologies) have been specifically tailored toward one system and may therefore not be compatible with others. To produce a functional synthetic cell, the integration of processes across diverse scales is necessary. We believe multiscale modeling will provide important physical insights. Additionally, because high-order communication between synthetic cells is being explored, ABM becomes relevant. In the end, hybrid modeling approaches need to be employed to grasp the complexity of modularity and multi-scales that cellular life poses. Integration of different cellular processes will be a significant milestone achievement in synthetic cell research. Ideally, as an example, a successfully integrated reconstitution involves spatiotemporally coordinating the segregation of a sufficiently compacted minimal genome with the growth and division of a liposome.

7 |. CONCLUSION

The creation of synthetic cells is truly an interdisciplinary discipline built upon a strong foundation in physics, chemistry, and biology—but also closely relates to engineering. Besides the potential for deciphering design principles of natural living cells, synthetic cells have significant potential as valuable biomedical and biotechnological tools. Synthetic cells can be designed to be invisible to the immune system, compared to engineered living cells, or be decorated with specific antigens used for the development of vaccines. The versatility of synthetic cells is only limited by the imagination of their creators and this promises an exciting final phase of biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Allen P. Liu acknowledges funding from NSF (MCB-1935265; CBET-1844132; MCB-1817909; DMR-1939534). Qiong Yang acknowledges funding from NSF (MCB-1817909; MCB-1553031), NIH (NIGMS- R35GM119688), and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Anthony G. Vecchiarelli acknowledges funding from NSF (MCB-1817478 and CAREER Award MCB-1941966). Tobias W. Giessen acknowledges funding from NIH (NIGMS-R35GM133325) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Grant: 5506).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

RELATED WIREs ARTICLES

The engineering of artificial cellular nanosystems using synthetic biology approaches

FURTHER READING

- Ahmad MR, Nakajima M, Kojima S, Homma M, & Fukuda T (2008). The effects of cell sizes, environmental conditions, and growth phases on the strength of individual W303 yeast cells inside ESEM. IEEE Transactions on Nanobioscience, 7(3), 185–193. 10.1109/TNB.2008.2002281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Golic KG, & Hawley RS (2005). Drosophila: A laboratory handbook (2nd ed., p. 164). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Wang J, Sun W, Archibong E, Kahkoska AR, Zhang X, … Gu Z (2018). Synthetic Beta cells for fusion-mediated dynamic insulin secretion. Nature Chemical Biology, 14(1), 86–93. 10.1038/nchembio.2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston TC, & Oster G (1997). Protein turbines I: The bacterial flagellar motor. Biophysical Journal, 73(2), 703–721. 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78104-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guet CC, Bruneaux L, Min TL, Siegal-Gaskins D, Figueroa I, Emonet T, & Cluzel P (2008). Minimally invasive determination of MRNA concentration in single living Bacteria. Nucleic Acids Research, 36(12), e73. 10.1093/nar/gkn329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver G (1875). On the size and shape of red corpuscles of the blood of vertebrates, with drawings of them to a uniform scale, and extended and revised tables of measurements. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1875, 474–495. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch N, Zimmerman LB, & Grainger RM (2002). Xenopus, the next generation: X. Tropicalis genetics and genomics. Developmental Dynamics, 225, 422–433. 10.1002/dvdy.10178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markow TA, Beall S, & Matzkin LM (2009). Egg size, embryonic development time and Ovoviviparity in Drosophila species. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(2), 430–434. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamoro-Vidal A, Salazar-Ciudad I, & Houle D (2015). Making quantitative morphological variation from basic developmental processes: Where are we? The case of the Drosophila wing. Developmental Dynamics, 244(9), 1058–1073. 10.1002/dvdy.24255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi MR (1992). Proteases and protein degradation in Escherichia coli. Experientia, 48(2), 178–201. 10.1007/bf01923511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, & Young KD (2000). Penicillin binding protein 5 affects cell diameter, contour, and morphology of Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology, 182(6), 1714–1721. 10.1128/jb.182.6.1714-1721.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, & D’Ari R (2007). Escherichia coli physiology in Luria-Bertani broth. Journal of Bacteriology, 189(23), 8746–8749. 10.1128/JB.01368-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz J (2016). Quantitative viral ecology: Dynamics of viruses and their microbial hosts (p. 55). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Kroenke CD, Song J, Piwnica-Worms D, Ackerman JJH, & Neil JJ (2008). Intracellular water-specific MR of microbead-adherent cells: The HeLa cell intracellular water exchange lifetime. NMR in Biomedicine, 21(2), 159–164. 10.1002/nbm.1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- Adamala KP, Martin-Alarcon DA, Guthrie-Honea KR, & Boyden ES (2017). Engineering genetic circuit interactions within and between synthetic minimal cells. Nature Chemistry, 9(5), 431–439. 10.1038/nchem.2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akita F, Chong KT, Tanaka H, Yamashita E, Miyazaki N, Nakaishi Y, … Nakagawa A (2007). The crystal structure of a virus-like particle from the hyperthermophilic archaeon pyrococcus furiosus provides insight into the evolution of viruses. Journal of Molecular Biology, 368(5), 1469–1483. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]