Graphical abstract

1. Introduction:

Explored and described by Lise Meitner [1] and Pierre Auger [2], the Auger effect has been explored as a potential source for targeted radiotherapy. The Auger effect is based on the emission of a low energy electron from an atom post electron capture (EC), internal conversion (IC), or incident X-rays excitation. This phenomenon can cause the emission of a primary electron and multiple electron tracks typically in the nearest proximity of the emission site (2–500 nm). The short range of the emitted Auger cascade results in medium/high levels of linear energy transfer (4–26 keV/μm) exerted on the surrounding tissue [3–7]. This property makes Auger emitters the ideal candidates for delivering high levels of targeted radiation to a specific target with dimensions comparable to, for example, the DNA [4, 8–11]. By using a targeting vector such as a small molecule, peptide or antibody, one has the potential of delivering high levels of radiation to tumor specific biomarkers while circumventing off-site toxicity in healthy cells; a challenge which is harder to overcome when using other, longer range sources of radiation such as beta and alpha emitting radionuclides [12]. Several reviews on Auger emitters have been published over the years with two recent examples [13, 14], including a very informative one discussing the advancements of the field in the 2015–2019 time period [15]. For these reviews and others, we support their analysis and therefore to avoid simple repetition, this commentary will seek to address additional aspects and viewpoints. Specifically, we will focus on those most promising preclinical and clinical studies using small molecules, peptides, antibodies and how these studies may serve as a template for future studies (Figure 1A). The authors of this review believe that Auger radiotherapy is at a point of change and offers great opportunities to those scientists who wish to embark in the mission of bringing preclinical Auger concepts to the clinic. We believe that this commentary will serve as a concise starting point and overview for the coming works on Auger radiotherapy.

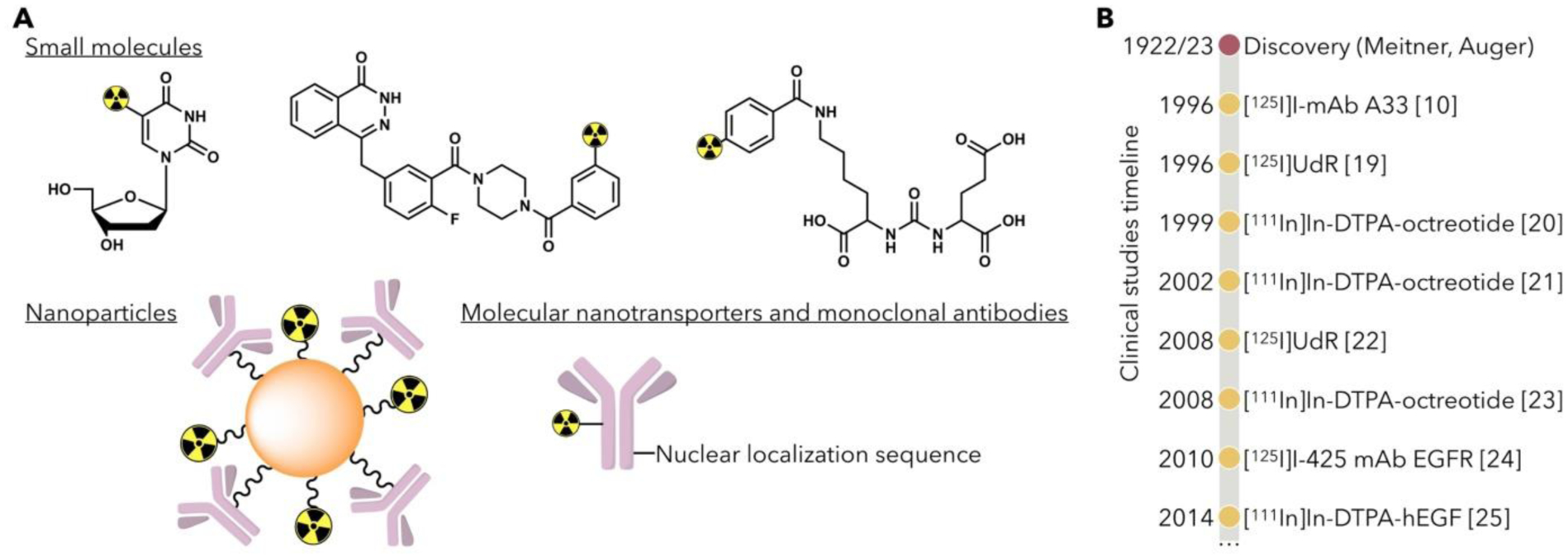

Figure1. Auger radiotherapy.

A. Potential carriers of Auger radiation emitting nuclides for cancer therapy have included small molecules ([125I]UdR [16], [123I]I-MAPi [17], [125I]DCIBzL[18]), nanoparticles, and monoclonal antibodies. B. Timeline of select clinical trials using Auger radiotherapy since their discovery in 1922/1923.

2. Technological development strategy:

The choice of the best strategy for the development of Auger-based medical biotechnology must be based on a combination of factors. These include (i) the relative potency – i.e., the total energy release in form of emitted electrons per decay, or electron yield. (ii) The amount of X- and γ-Rays emitted per decay, which can be used for imaging, biodistribution, and dosimetry studies. (iii) The isotope’s half-life. (iv) The available radiochemistry for labelling a shuttle molecule. (v) The biology of the chosen strategy – i.e., the ability to actually carry the Auger emitter close enough to its target and allow enough energy to be deposited to present cytotoxicity. The most common Auger-emitting isotopes available for such applications are Iodine-123, Iodine-125, Gallium-67, Technetium-99m, Indium-111, Thallium-201. In addition to these, there is a published list of several possible Auger emitters which is much more advanced, and which could include other “next-generation” therapeutic Auger isotopes [26].

The ability to seek the nucleus of the cell, specifically the DNA, is a fundamental goal when developing new Auger theranostics agents. To attempt this, various cancer-specific molecular targets have been explored using small molecules, antibodies, and peptides.

3. Small Molecules:

Early successful examples of small molecules carrying an Auger isotope payload were mainly focused on the thymidine analog 5-iodo-2’-deoxyuridine ([123I]UdR/[125I]UdR), a nucleoside analogue which is incorporated directly into the DNA. This strategy has been developed in vitro, in vivo, and in clinical trials with promising results [19, 27]. Another successful approach has been the preclinical and clinical targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) via characterization of [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF [28] and 111In- or 125I-labelled anti-EGFR antibodies, however limited to Phase I trials [29]. Other approaches included the radiolabeling of Anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin and daunorubicin), and Cisplatin, showing synergism in killing cancer cells without major increase in toxicity [13]. Another recent preclinical work is [123I]I-MAPi, a PARP inhibitor (PARPi) derived Auger theranostic agent [17, 30]. In 2020, our group demonstrated [123I]I-MAPi to be a viable agent for the treatment of glioblastoma. In this instance, the scaffold inhibitor known as Olaparib was utilized to shuttle Auger radiation to the site of DNA, a strategy which may serve as an inspiration for future works.

4. Peptides:

A challenge with small molecules is that typically, in order to incorporate an Auger emitter, major structural changes are required to achieve this. This challenge has been compounded by the limited number of Auger emitting radionuclides amenable to covalent bond formation. Consequently, several groups have sought to harness peptides for the delivery of Auger radiation. Peptides are typically larger in mass compared to small molecules and more robust to chemical modifications. Off the back of their success as imaging agents and beta-emitting therapeutics, investigations into Auger containing PSMA ([125I]DCIBzL) and octreotide ([111In]In-DTPA-Octreotide ) molecules have been explored [18, 31]. A very promising example was published in 2020 by Shen and co-workers, who demonstrate improved survival in PSMA expressing micro-metastasis models without significant off-site toxicity, as confirmed through weight monitoring and histopathology of critical organs. In this instance, the success of this work can be recognized in the matching of a highly expressed biomarker combined with a probe amenable to cellular internalization. In tandem to these efforts, there is a growing body of literature discussing the potential for combining targeted peptides with nuclear localization sequences (NLS). NLS typically take the form of highly charged species that allow for rapid internalization into cell nuclei. [32] One example, originally disclosed in its unmodified form in 2007, is hEGF [33]. Modified in 2014 using a nuclear localization sequence, Koumarianou and coworkers demonstrated superior nuclear uptake compared to the unmodified hEGF [34].

5. Antibodies:

The field of antibody based radioimmunotherapy is rapidly growing, with beta and alpha emitters becoming well established in pre-clinical models for their efficacy towards a range of antigens [35]. The use of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has been also successful in combination with Auger emitters. However, due to the short range of the emitted radiation, an internalizing sequence is typically added to the antibody to allow its cellular penetration. As an example, the preclinical and clinical use of the monoclonal antibody A33, radiolabeled with Iodine-125 ([125I]I-mAb A33), has been reported [10]. [125I]I-CO17–1 mAbs have been tested in colon cancer cells and in clinical trial with limited toxicities but also limited curative potential at the tested dosage [36]. As highlighted for peptides, NLS peptides have seen increased use within the community. For instance, [111In]In-NLS-Trastuzumab proved efficacious in the treatment of athymic mice bearing HER-positive human breast cancer xenografts [37].

Studies of the efficacy of Auger emitters in correlation to their subcellular localization have been performed showing that also the cell membrane targeting could be a cytotoxic target [38, 39] [40].

6. The Auger Pipeline:

To date, there are a wide number of examples of Auger containing molecules to be reported within a preclinical setting [13]. Within these, there are few examples of Auger containing agents which have reached clinical trials, often with promising outcomes (Figure 1B). [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF [25] and [125I]I-mAb 425 [24] represent two examples to make it into clinical trials in the past decade. Clinical improvement was often observed when patients were treated with Auger biotechnology. However, total remissions have been rare. In part, this is due to variable response rates within cohorts being observed for these agents, and in certain cases the relatively small patient cohorts considered or a modest observed effect compared to the preclinical settings. With this in mind, it may be important that any pre-clinical studies not only demonstrate reliable efficacy, but also, that the necessary toxicity studies be carried out. The constant improvement of our understanding of cancer-specific molecular processes, combined with the recent improvement in radiopharmaceutical tools for the design of novel Auger molecules, open the doors to the development of novel strategies for the clinical translation of Auger radiation.

7. Moving the field forward

The field of Auger therapy has seen a renaissance over recent years within the pre-clinical space, suggesting that this may result in additional translational efforts. Previously seen as being out of reach for targeted radiotherapy due to its limited efficacy range distance, the previous scientific attempts, some of which are highlighted in this commentary, prove that through rational design, Auger emitters have great potential as therapeutic agents. Indeed, with the growing pipeline of Auger-carrying small molecules, peptides and monoclonal antibodies, it is clear that the limited range of action of Auger isotopes represents a real opportunity for precision energy deposition and extremely limited off-target interaction. With many agents offering improved levels of therapeutic efficacy, we are beginning to see a larger number of studies take the next steps in their evaluation for clinical translatability. Investigations into metabolic behavior, dose optimization and toxicity studies are fundamentally important for bridging the gap between the pre-clinical and clinical space. Furthermore, the advances in computational techniques for dosimetry simulations are expanding the understanding of dose distribution at the organ, cellular, and subcellular level, providing a clearer understanding of the potential of Auger as a non-toxic dose provider. The next stage will be to drive these promising candidates into clinical studies. Proof-of-concept within the clinical space with regards to consistent response rates and limited off-site toxicity is the ultimate goal; this may establish Auger emitters as an elegant novel strategy for targeted therapy, i.e., an extremely useful tool for clinical application.

8. Acknowledgements

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA204441, P30 CA008748, R43 CA228815. The authors thank the Tow Foundation and MSK’s Center for Molecular Imaging & Nanotechnology and Imaging and Radiation Sciences Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: T.R. is shareholder of Summit Biomedical Imaging, LLC. and co-inventor on U.S. patent (WO2016033293) held by MSK that covers methods for the synthesis and use of [18F]F-PARPi, [131I]I-PARPi and [123I]I-MAPi. T.R. is a paid consultant for Theragnostics, Inc. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article exist.

References:

- [1].Meitner L Über die entstehung der β-strahl-spektren radioaktiver substanzen. Zeitschrift für Physik. 1922;9:131–44. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Auger P Sur les rayons β secondaires produits dans un gaz par des rayons X. CR Acad Sci(F). 1923;177:169. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hofer KG, Hughes WL. Radiotoxicity of intranuclear tritium, 125 iodine and 131 iodine. Radiat Res. 1971;47:94–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bavelaar BM, Lee BQ, Gill MR, Falzone N, Vallis KA. Subcellular Targeting of Theranostic Radionuclides. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kassis AI. Cancer therapy with Auger electrons: are we almost there. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1479–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Falzone N, Fernández-Varea JM, Flux G, Vallis KA. Monte Carlo Evaluation of Auger Electron-Emitting Theranostic Radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee H, Riad A, Martorano P, Mansfield A, Samanta M, Batra V et al. PARP-1-Targeted Auger Emitters Display High-LET Cytotoxic Properties In Vitro but Show Limited Therapeutic Utility in Solid Tumor Models of Human Neuroblastoma. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Buchegger F, Perillo-Adamer F, Dupertuis YM, Delaloye AB. Auger radiation targeted into DNA: a therapy perspective. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1352–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kiess AP, Minn I, Chen Y, Hobbs R, Sgouros G, Mease RC et al. Auger Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Targeting Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Welt S, Scott AM, Divgi CR, Kemeny NE, Finn RD, Daghighian F et al. Phase I/II study of iodine 125-labeled monoclonal antibody A33 in patients with advanced colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14:1787–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Daghighian F, Barendswaard E, Welt S, Humm J, Scott A, Willingham MC et al. Enhancement of radiation dose to the nucleus by vesicular internalization of iodine-125-labeled A33 monoclonal antibody. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1052–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gill MR, Falzone N, Du Y, Vallis KA. Targeted radionuclide therapy in combined-modality regimens. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ku A, Facca VJ, Cai Z, Reilly RM. Auger electrons for cancer therapy – a review. EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry. 2019;4:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Martin RF, Feinendegen LE. The quest to exploit the Auger effect in cancer radiotherapy–a reflective review. International journal of radiation biology. 2016;92:617–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Howell RW. Advancements in the use of Auger electrons in science and medicine during the period 2015–2019. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 20201–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bloomer WD, Adelstein SJ. 5–125I-iododeoxyuridine as prototype for radionuclide therapy with Auger emitters. Nature. 1977;265:620–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pirovano G, Jannetti SA, Carter LM, Sadique A, Kossatz S, Guru N et al. Targeted Brain Tumor Radiotherapy Using an Auger Emitter. American Association for Cancer Research; 2020:2871–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shen CJ, Minn I, Hobbs RF, Chen Y, Josefsson A, Brummet M et al. Auger radiopharmaceutical therapy targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen in a micrometastatic model of prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2020;10:2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Macapinlac HA, Kemeny N, Daghighian F, Finn R, Zhang J, Humm J et al. Pilot clinical trial of 5-[125I]iodo-2’-deoxyuridine in the treatment of colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:25S–9S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Krenning EP, De Jong M, Kooij PPM, Breeman WAP, Bakker WH, De Herder WW et al. Radiolabelled somatostatin analogue (s) for peptide receptor scintigraphy and radionuclide therapy. Annals of Oncology. 1999;10:S23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Valkema R, De Jong M, Bakker WH, Breeman WA, Kooij PP, Lugtenburg PJ et al. Phase I study of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with [In-DTPA]octreotide: the Rotterdam experience. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:110–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rebischung C, Hoffmann D, Stefani L, Desruet MD, Wang K, Adelstein SJ et al. First human treatment of resistant neoplastic meningitis by intrathecal administration of MTX Plus 125IUdR. International journal of radiation biology. 2008;84:1123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Limouris GS, Chatziioannou A, Kontogeorgakos D, Mourikis D, Lyra M, Dimitriou P et al. Selective hepatic arterial infusion of In-111-DTPA-Phe 1-octreotide in neuroendocrine liver metastases. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2008;35:1827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li L, Quang TS, Gracely EJ, Kim JH, Emrich JG, Yaeger TE et al. A phase II study of anti–epidermal growth factor receptor radioimmunotherapy in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Journal of neurosurgery. 2010;113:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vallis KA, Reilly RM, Scollard D, Merante P, Brade A, Velauthapillai S et al. Phase I trial to evaluate the tumor and normal tissue uptake, radiation dosimetry and safety of 111In-DTPA-human epidermal growth factor in patients with metastatic EGFR-positive breast cancer. American journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2014;4:181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Filosofov D, Kurakina E, Radchenko V. Potent candidates for Targeted Auger Therapy: Production and radiochemical considerations. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ. Radiobiologic principles in radionuclide therapy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:4S–12S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reilly RM, Kassis A. Targeted Auger Electron Radiotherapy of Malignancies. Monoclonal antibody and peptide-targeted radiotherapy of cancer. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. p. 289–348. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Michel RB, Castillo ME, Andrews PM, Mattes MJ. In vitro toxicity of A-431 carcinoma cells with antibodies to epidermal growth factor receptor and epithelial glycoprotein-1 conjugated to radionuclides emitting low-energy electrons. Clinical cancer research. 2004;10:5957–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wilson TC, Jannetti SA, Guru N, Pillarsetty N, Reiner T, Pirovano G. Improved radiosynthesis of 123I-MAPi, an auger theranostic agent. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2020;0:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Capello A, Krenning EP, Breeman WAP, Bernard BF, de Jong M. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in vitro using [111In-DTPA0] octreotide. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sobolev AS. Modular nanotransporters for nuclear-targeted delivery of auger electron emitters. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2018;9:952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bailey KE, Costantini DL, Cai Z, Scollard DA, Chen Z, Reilly RM et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition modulates the nuclear localization and cytotoxicity of the Auger electron–emitting radiopharmaceutical 111In-DTPA–human epidermal growth factor. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:1562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Koumarianou E, Slastnikova TA, Pruszynski M, Rosenkranz AA, Vaidyanathan G, Sobolev AS et al. Radiolabeling and in vitro evaluation of 67Ga-NOTA-modular nanotransporter–A potential Auger electron emitting EGFR-targeted radiotherapeutic. Nuclear medicine and biology. 2014;41:441–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Herrmann K, Schwaiger M, Lewis JS, Solomon SB, McNeil BJ, Baumann M et al. Radiotheranostics: a roadmap for future development. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e146–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meredith RF, Khazaeli MB, Plott WE, Spencer SA, Wheeler RH, Brady LW et al. Initial Clinical Evaluation of Iodine-125-Labeled Chimeric 17-lA for Metastatic Colon Cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1995;36:2229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Costantini DL, Chan C, Cai Z, Vallis KA, Reilly RM. 111In-labeled trastuzumab (Herceptin) modified with nuclear localization sequences (NLS): an Auger electron-emitting radiotherapeutic agent for HER2/neu-amplified breast cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:1357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Paillas S, Ladjohounlou R, Lozza C, Pichard A, Boudousq V, Jarlier M et al. Localized Irradiation of Cell Membrane by Auger Electrons Is Cytotoxic Through Oxidative Stress-Mediated Nontargeted Effects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;25:467–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pouget JP, Santoro L, Raymond L, Chouin N, Bardiès M, Bascoul-Mollevi C et al. Cell membrane is a more sensitive target than cytoplasm to dense ionization produced by auger electrons. Radiat Res. 2008;170:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ladjohounlou R, Lozza C, Pichard A, Constanzo J, Karam J, Le Fur P et al. Drugs That Modify Cholesterol Metabolism Alter the p38/JNK-Mediated Targeted and Nontargeted Response to Alpha and Auger Radioimmunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4775–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]