Abstract

The rust fungi (Pucciniales) with 7000+ species comprise one of the largest orders of Fungi, and one for which taxonomy at all ranks remains problematic. Here we provide a taxonomic framework, based on 16 years of sampling that includes ca. 80 % of accepted genera including type species wherever possible, and three DNA loci used to resolve the deeper nodes of the rust fungus tree of life. Pucciniales are comprised of seven suborders – Araucariomycetineae subord. nov., Melampsorineae, Mikronegeriineae, Raveneliineae subord. nov., Rogerpetersoniineae subord. nov., Skierkineae subord. nov., and Uredinineae – and 18 families – Araucariomycetaceae fam. nov., Coleosporiaceae, Crossopsoraceae fam. nov., Gymnosporangiaceae, Melampsoraceae, Milesinaceae fam. nov., Ochropsoraceae fam. & stat. nov., Phakopsoraceae, Phragmidiaceae, Pileolariaceae, Pucciniaceae, Pucciniastraceae, Raveneliaceae, Rogerpetersoniaceae fam. nov., Skierkaceae fam. & stat. nov., Sphaerophragmiaceae, Tranzscheliaceae fam. & stat. nov., and Zaghouaniaceae. The new genera Araucariomyces (for Aecidium fragiforme and Ae. balansae), Neoolivea (for Olivea tectonae), Rogerpetersonia (for Caeoma torreyae), and Rossmanomyces (for Chrysomyxa monesis, Ch. pryrolae, and Ch. ramischiae) are proposed. Twenty-one new combinations and one new name are introduced for: Angiopsora apoda, Angiopsora chusqueae, Angiopsora paspalicola, Araucariomyces balansae, Araucariomyces fragiformis, Cephalotelium evansii, Cephalotelium neocaledoniense, Cephalotelium xanthophloeae, Ceropsora weirii, Gymnotelium speciosum, Lipocystis acaciae-pennatulae, Neoolivea tectonae, Neophysopella kraunhiae, Phakopsora pipturi, Rogerpetersonia torreyae, Rossmanomyces monesis, Rossmanomyces pryrolae, Rossmanomyces ramischiae, Thekopsora americana, Thekopsora potentillae, Thekopsora pseudoagrimoniae, and Zaghouania notelaeae. Higher ranks are newly defined with consideration of morphology, host range and life cycle. Finally, we discuss the evolutionary and diversification trends within Pucciniales.

Citation: Aime MC, McTaggart AR (2020). A higher-rank classification for rust fungi, with notes on genera. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 7: 21–47. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2021.07.02

Keywords: host alternation, life cycles, Uredinales, Urediniomycetes, 37 new taxa

INTRODUCTION

Rust fungi (Pucciniomycotina, Pucciniales) comprise one of the largest orders in Fungi, containing ca. 25 % of described Basidiomycota. All are obligate pathogens of plants and at ca. 7 000+ accepted species (Kirk et al. 2008) form the most species-rich group of plant pathogens. Diseases caused by rust fungi have impacted human agriculture and history through time. Rusts likely caused the earliest recognized diseases of agricultural plants (Carefoot & Sprott 1967), and have continued to impact anthropogenic ecosystems through epidemics and localized host extinctions (Carnegie & Pegg 2018). The Green Revolution in the mid to late 20th century that heralded the era of host resistance breeding targeted rust fungi (Philips 2013).

Pucciniales has a suite of characteristics that are rare or unique within Fungi, including alternation of generations with separate gametothalli (spermogonia and aecia) and sporothalli (uredinia and telia) that may infect unrelated hosts (heteroecious); and the production of up to five different morphs within the life cycle. These characteristics, together with many instances of convergent evolution within morphs, repeated evolution of derived life cycle variants, and varying taxonomic emphases on different morph characteristics, have contributed to the development of numerous classification schemes for rust fungi (Fig. S1). Further taxonomic confusion within Pucciniales at the species rank has been shaped by separate naming systems under prior nomenclatural codes for sexual and asexual morphs. For instance, prior to the use of molecular data to link morphs, only through painstaking inoculation studies could complete life cycles be elucidated (e.g., Cummins 1978). Consequently, many asexual morphs were unplaceable within a sexual morph-based classification system. Recent changes to the nomenclatural code now allow the placement of taxa within natural genera, regardless of morph (McNeill et al. 2012, Turland et al. 2018). Although most asexual genera have been reduced to synonymy (Aime et al. 2018b), some, such as Uredo and Aecidium contain species that occur in over 50 sexual genera, and it will be non-trivial to assign these to natural genera.

Generic-rank classification, even for sexual morph species, is similarly difficult. At least 334 generic names have been described in Pucciniales; most researchers accept ca. 130 of these (e.g., Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). Studies have shown that many diagnostic characters are homoplasious, such as the number of cells per teliospore (Aime 2006, Maier et al. 2007, van der Merwe et al. 2007, Yun et. al. 2008, Beenken & Wood 2015). As a result, most taxon-rich genera – the largest being Puccinia (ca. 4 000 species), Uromyces (ca. 800 species), and Ravenelia (ca. 200 species) – are polyphyletic and will need thoughtful re-evaluation for how to reassign these species into monophyletic genera.

At the higher ranks, classification of rust fungi has varied through time as well (Fig. S1). Rust fungi were initially classified into families by characteristics of basidia and teliospores (e.g., Cunningham 1931). This approach divided rusts into three (or four) families, Melampsoraceae, (Coleosporiaceae), Pucciniaceae and Zaghouaniaceae (Sydow & Sydow 1915, Cunningham 1931). Arthur (1907–1931), Sydow & Sydow (1915) and Dietel (1928) further classified rusts in subfamilies or tribes based on morphology of telia. Other workers, such as Hiratsuka & Cummins (1963) placed greater emphasis on the gametothallus, especially spermogonial morphology, resulting in conflicting taxonomic hypotheses. This approach was later combined with teliospore morphology (Cummins & Hiratsuka 1983, 2003) to achieve a 13-family classification that became the most broadly applied in the pre-molecular era.

The first molecular systematic study to test the familial classification of Cummins & Hiratsuka (2003) subdivided the rust fungi into three major radiations, Mikronegeriineae, Melampsorineae, and Uredinineae, that mostly correspond to the earlier three-family approach of Cunningham (1931) (Aime 2006). Within these radiations were (i) several lineages more or less corresponding to families circumscribed by Cummins & Hiratsuka (2003), such as Coleosporiaceae, Melampsoraceae, Zaghouaniaceae (as Mikronegeriaceae), Phragmidiaceae, Pileolariaceae, Pucciniaceae, Pucciniastraceae and Raveneliaceae; (ii) families, such as Chaconiaceae and Phakopsoraceae that were comprised of polyphyletic assemblages that could not be effectively resolved without data from type species; and (iii) several so-called “orphan” genera that could not confidently be assigned to families (Aime 2006).

Numerous subsequent studies have focused on resolution of single families, e.g., Sphaerophragmiaceae (Beenken 2017); polyphyletic genera, e.g., segregation of Neophysopella from Phakopsora (Ji et al. 2019); as well as conservation efforts to stabilize use of generic names (e.g., Aime et al. 2018b, 2019a, b). Despite these efforts, a stable and resolved higher-rank classification for the rust fungi has not been achieved. A major bottleneck has been limited sampling of taxa that represent the type species of genera, especially for genera with convergent morphologies, that are polyphyletic, and/or contain species with multiple competing names for different morphs.

The purpose of the present study is to provide a stable higher-rank classification for Pucciniales that will serve as a framework for future systematic studies. We have assembled a dataset over the last 16 years that includes exemplars from 113 (ca. 80 %) rust genera, including 108 that are represented by sequences from type species (86) or type species proxies (22). Our phylogenetic hypotheses are based on DNA data from three loci (nuclear large subunit and small subunit rDNA, and Cytochrome-c-oxidase subunit 3) with varying evolutionary rates across Pucciniales (e.g., Aime 2006, Vialle et al. 2009, Feau et al. 2011, Aime et al. 2018a, McTaggart & Aime 2018). We propose a natural classification for Pucciniales based on combined evidence from morphology, life cycles, hosts, and phylogenetic data. Several new suborders, families, genera, and combinations are proposed, and suborders and families are redefined. Finally, we discuss the evolutionary trends that led to diversification within Pucciniales and highlight unresolved areas of the rust family tree for future research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Taxon selection

Priority was given to species that represent generic types of rust fungi. If type species were unavailable, wherever possible two congeneric species similar to the type in respect to host genus, morphology, and geography were chosen as proxies (e.g., Skierka, Tranzschelia, Uredopeltis and Uropyxis). At least one exemplar was included for every major lineage of Pucciniales that had been previously identified (e.g., Aime 2006e.g., Aime 2018a, Beenken 2017). Additional genera were targeted (i) from families that appeared polyphyletic in prior studies (e.g., Chaconiaceae, Phakopsoraceae); (ii) from previously undersampled families, e.g., Uropyxidaceae; and (iii) to broaden sampling of endocyclic species (e.g., Baeodromus, Chardoniella, Cionothrix, Dietelia, Pucciniosira). If possible, more than one species was included for genera (i) previously determined as orphaned taxa sensu Aime (2006) (e.g., Gymnosporangium, Prospodium, Ochropsora, and Tranzschelia) or incertae sedis sensu Cummins & Hiratsuka (2003) (Elateraecium, Masseeëlla); and (ii) previously demonstrated as polyphyletic (e.g., Maravalia, Phakopsora, Pucciniastrum, Ravenelia). Additional taxa were also included for genera if complete data at the three sequenced loci were available (e.g., Gymnosporangium, Hamaspora, Melampsora, Neophysopella, and Phragmidium). An initial dataset of 130 rust taxa and three loci (Table 1) was used to determine the familial placement of genera and the relationships between families in an overview tree. The overview tree was rooted with Eocronartium muscicola, from the sister order to Pucciniales (Aime et al. 2006).

Table 1.

Collection and accession data for sequences used in Pucciniales overview tree (Fig. 1).

| Taxon | Type statusa | Voucher number (Collection number)b | 28S | 18S | CO3 | Host | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achrotelium ichnocarpi | T | BRIP 55685 | KT199393 | KT199381 | KT199404 | Ichnocarpus frutescens | McTaggart et al. (2016) |

| Aecidium kalanchoe | BPI 843633 (U18, HOLOTYPE) | AY463163 | DQ354524 | NA | Kalanchoe blossfeldiana | Hernandez et al. (2004) | |

| Allodus podophylli | T | BPI 842277 (U2, NEOTYPE):28S,18S; PUR N16753:CO3 | DQ354543 | DQ354544 | MG907270 | Podophyllum peltatum | Aime (2006); Aime et al. (2018a) |

| Angiopsora paspalicola | * | BRIP 55625 | MW049243 | NA | MW036496 | Paspalum sp. | this paper |

| Aplopsora nyssae | T | BPI 877823 (U1191) | MW049244 | NA | NA | Nyssa sylvatica | this paper |

| Araucariomyces fragiformis | T | BRIP 68996 | MW049245 | MW049292 | MW036497 | Agathis robusta | this paper |

| Austropuccinia psidii | T | BRIP 58164 | KF318449 | KF318457 | KT199419 | Rhodamnia angustifolia | Pegg et al. (2014); McTaggart et al. (2016) |

| Baeodromus eupatorii | * | PUR N16312 (U1386) | MW049246 | NA | NA | Ageratina sp. | this paper |

| Bibulocystis pulcherrima | T | BRIP 58450 | MW049247 | NA | MW036498 | Daviesia latifolia | this paper |

| Blastospora smilacis | T | PUR N270 | DQ354568 | DQ354567 | NA | Smilax sieboldii | Aime (2006) |

| Bubakia argentinensis (as Phakopsora argentinensis) | * | ZT:RB 8248 | KF528009 | NA | NA | Croton cf. anisodontus | Beenken (2014) |

| Calyptospora goeppertiana | T | BPI 882188 (U866) | MW147023 | NA | NA | Abies balsamea | this paper |

| Catenulopsora flacourtiae | T | PUR N13865 (U669) | MW049248 | MW049293 | NA | Flacourtia indica | this paper |

| Cephalotelium macowaniana (as Ravenelia macawaniana) | T | PREM 61222 | MG946007 | NA | NA | Vachellia karroo | Ebinghaus et al. (2018a) |

| Cephalotelium neocaledoniense (as Ravenelia neocaledoniensis) | BRIP 56908 | KJ862348 | NA | KJ862460 | Vachellia farnesiana | McTaggart et al. (2015) | |

| Ceratocoma jacksoniae | T | BRIP 57717 | KT199394 | KT199382 | KT199405 | Davesia sp. | McTaggart et al. (2016) |

| Ceropsora weirii (as Chrysomyxa weirii) | * | 916CHWPCGSG8 | FJ666465 | NA | NA | n.d. | Vialle et al. (2009) |

| Chaconia ingae | * | BPI 863575 (GUY74) | MW049249 | NA | NA | Inga sp. | this paper |

| Chardoniella gynoxidis | T | R15 | MW049250 | NA | NA | Gynoxys sp. (cf.) | this paper |

| Chrysocelis lupini | T | PUR N11562 (U1570) | MW049251 | NA | NA | Lupinus sp. | this paper |

| Chrysomyxa arctostaphyli | CUW CFB 22246 | AF522163 | AY657009 | NA | n.d. | Matheny et al. unpublished | |

| Cionothrix praelonga | T | PUR 90104 | MW049252 | NA | NA | Eupatorium sp. | this paper |

| Coleopuccinia sinensis | T | BJFC R02506 | MF802285 | NA | NA | Cotoneaster microphyllus | Cao et al. (2018) |

| Coleosporium senecionis | T | PDD 98309 | KJ716348 | KJ746818 | NA | Senecio sp. | Padamsee & McKenzie (2014) |

| Cronartium flaccidum | T | PUR N16561 (MCA4165) | MW049253 | MW049294 | NA | Vincetoxicum hirundinaria | this paper |

| Cronartium harknessii (≡Endocronartium harknessii) | (T) | CFB22250 | AF522175 | AY665785 | NA | Pinus sp. | Szaro & Bruns unpublished; Matheny et al. unpublished |

| Crossopsora fici | BRIP 58118 | MH047207 | MH047212 | MH047204 | Ficus virens var. sublanceolata | this paper | |

| Crossopsora ziziphi | T | BPI 877877 (U904) | MG744558 | NA | NA | Ziziphus mucronata | Souza et al. (2018) |

| Cumminsiella mirabilissima | T | BPI 871101 (U480) | DQ354531 | DQ354530 | NA | Mahonia aquifolium | Aime (2006) |

| Dasyspora gregaria | T | ZT Myc 3397 | JF263477 | JF263502 | JF263518 | Xylopia cayennensis | Beenken et al. (2012) |

| Desmella aneimiae | T | BRIP 60995 | KM249867 | NA | NA | Nephrolepis hirsutula | McTaggart et al. (2014) |

| Diaphanopellis purpurea | * | BJFC R02448 | MK874622 | NA | NA | Picea brachytyla | Yang & Wang unpublished |

| Didymopsora solani-argentei | T | PUR N3728 | MW049254 | NA | NA | Solanum argentum | this paper |

| Dietelia codiaei | * | PUR N16488 | MW049255 | NA | NA | Codiaeum variegatum | this paper |

| Dipyxis mexicana | T | BPI 871906 | MW049256 | NA | NA | Adenocalymna sp. | this paper |

| Edythea quitensis | T | QCAM6453 | MG596499 | NA | NA | Berberis hallii | Barnes & Ordonez unpublished |

| Elateraecium salaciicola | T | PUR F17677 | MW049257 | MW049295 | NA | Salacia sp. | this paper |

| Endophylloides portoricensis (as Dietelia portoricensis) | T | BPI 844288 (U322):28S; n.d.:18S | DQ354516 | AY125389 | NA | Mikania micrantha | Aime (2006); Wingfield et al. (2004) |

| Endophyllum cassiae | BPI 871369 (U525) | MW049258 | NA | NA | Cassia obtusifolia | this paper | |

| Endophyllum circumscriptum | BPI 872271 | MW049259 | NA | NA | Cissus sp. | this paper | |

| Endoraecium acaciae | T | BPI 871098 (MCA2957) | DQ323916 | DQ323917 | NA | Acacia koa | Scholler & Aime (2006) |

| Eocronartium muscicola | MIN796447:28S; DUKE:DAH(e1):18S | AF014825 | DQ241438 | NA | NA | Bruns & Szaro unpublished; Henk & Vilgalys (2007) | |

| Gerwasia rubi | T | BRIP 58440 | KT199397 | NA | KT199408 | Rubus sp. | McTaggart et al. (2016) |

| Gymnoconia interstitialis | T | BPI 747600 | JF907677 | DQ521422 | NA | Rubus allegheniensis | Yun et al. (2011); Matheny et al. unpublished |

| Gymnosporangium clavariiforme (≡Podisoma clavariiforme) | (T) | BRIP 59471 | MW049261 | MW049296 | MW036499 | Crataegus sp. | this paper |

| Gymnosporangium sabinae | T | TNM F0030477 | KY964764 | KY964764 | NA | Pyrus communis | Shen et al. (2018) |

| Gymnotelium blasdaleanum | * | PUR N10018 (U1469) | MG907218 | MG907206 | MG907269 | Amelanchier alnifolia | Aime et al. (2018a) |

| Hamaspora acutissima | BRIP 56949 | KT199398 | KT199385 | KT199409 | Rubus moluccanus | McTaggart et al. (2016) | |

| Hamaspora longissima | T | BPI 871506 (U305) | MW049262 | MW049297 | NA | Rubus ludwigii | this paper |

| Hapalophragmium derridis | T | PUR N16494 | MW049263 | NA | NA | unidentified Fabaceae | this paper |

| Hemileia vastatrix | T | BRIP 61233 | KT199399 | DQ354565 | KT199410 | Coffea robusta | McTaggart et al. (2016); Aime (2006) |

| Hyalopsora aspidiotus | T | PUR N4641 | MW049264 | NA | NA | Gymnocarpium dryopteris | this paper |

| Kernkampella breyniae | * | BRIP 56909 | KJ862346 | KJ862428 | KJ862459 | Breynia cernua | McTaggart et al. (2015) |

| Kuehneola uredinis | T | BPI 871104 (MCA2830) | DQ354551 | DQ092919 | NA | Rubus argutus | Aime (2006); Matheny & Hibbett unpublished |

| Kweilingia bambusae | T | PUR F18200 | MW147026 | NA | NA | Bambusa sp. | this paper |

| Lipocystis acaciae-pennatulae (as Ravenelia acaciae-pennatulae) | BPI 864189 (U115) | MG907213 | MG907204 | MG907264 | Vachellia pennatula | Aime et al. (2018a) | |

| Lipocystis caesalpiniae | T | BPI 863966 | MW049265 | NA | NA | Mimosa ceratonia | this paper |

| Macruropyxis fraxini | T | ZT Myc 56551 | KP858145 | KP858144 | NA | Fraxinus platypoda | Beenken & Wood (2015) |

| Maravalia limoniformis | * | BRIP 59649 | MW049266 | NA | MW036500 | Austrosteenisia blackii | this paper |

| Masseeëlla capparis | T | BRIP 56844 | JX136798 | NA | KT199413 | Flueggea virosa | McTaggart et al. (2016) |

| Melampsora euphorbiae | T | BPI 863501 (U138) | DQ437504 | DQ789986 | MW036501 | Euphorbia macroclada | Aime (2006); this paper |

| Melampsora laricis-populina | strain 98AG31 | NW6768836 | NW6768836 | NW6768836 | Populus sp. | Duplessis et al. unpublished | |

| Melampsorella caryophyllacearum | T | PUR ex-MPPD-40507 | MG907233 | NA | NA | Cerastium fontanum | Aime et al. (2018a); this paper |

| Melampsoridium betulinum | T | BPI 871107 (MCA2884):28S; n.d.: 18S | DQ354561 | AY125391 | NA | Alnus sp. | Aime (2006); Wingfield et al. (2004) |

| Mikronegeria fagi | T | PUR N16373 | MW049267 | MW049298 | NA | Nothofagus obliqua | this paper |

| Mikronegeria fuchsiae | PDD 101517 | KJ716350 | KJ746826 | NA | Phyllocladus trichomanoides | Padamsee & McKenzie (2014) | |

| Milesia polypodii (as Milesina polypodii) | T | KRM0043190 | MK302190 | NA | NA | Polypodium vulgare | Bubner et al. (2019) |

| Milesina kriegeriana | T | KRM0048480 | MK302207 | NA | NA | Dryopteris dilatata | Bubner et al. (2019) |

| Miyagia pseudosphaeria | * | BPI 842230 (U63):28S; n.d.: 18S | DQ354517 | AY125411 | NA | Sonchus oleraceus | Aime (2006); Wingfield et al. (2004) |

| Naohidemyces vaccinii | T | BPI 871754 (MCA2780) | DQ354563 | DQ354562 | NA | Vaccinium ovatum | Aime (2006) |

| Neoolivea tectonae | T | PUR N15331 (MCA6480) | MW049282 | MW049307 | MW036507 | Tectona grandis | this paper |

| Neophysopella ampelopsidis (as Phakopsora ampelopsidis) | T | IBA 8597 | AB354738 | NA | NA | Ampelopsis brevipedunculata | Chatasiri & Ono (2008) |

| Neophysopella kraunhiae | PUR N15073 | MW049242 | NA | NA | Wisteria floribunda | this paper | |

| Neophysopella meliosmae-myrianthae | BRIP 58404 | MW049270 | NA | NA | Vitus sp. | this paper | |

| Newinia heterophragmatis | T | PUR N16505 | MW049271 | NA | NA | Kigelia cf. africana | this paper |

| Nothoravenelia japonica | T | HMJAU8598 | MK296509 | NA | NA | n.d. | Ji unpublished |

| Nyssopsora echinata | T | KR-0012164 (U1022):28S; ESS244:18S | MW049272 | U77061 | NA | Meum athamanticum | this paper; Swann & Taylor (1995) |

| Ochropsora ariae | T | KR-0015027 (U1036) | MW049273 | NA | NA | Anemone nemorosa | this paper |

| Olivea capituliformis | T | BPI 863670 | MW049274 | NA | NA | Alchornea latifolia | this paper |

| Peridiopsora mori | PUR N11676 (MCA4685) | MW147025 | NA | MW166323 | Morus alba | this paper | |

| Phakopsora crucis-filii | T | ZT Myc 48990 | KF528016 | KF528041 | KF528049 | Annona paludosa | Beenken (2014) |

| Phakopsora fici | BRIP 59463 | MH047210 | MW049299 | MW036502 | Ficus carica | this paper | |

| Phakopsora pachyrhizi | T | BRIP 56941 | KP729475 | MW049300 | MW036503 | Neonotonia wightii | Maier et al. (2016); this paper |

| Phragmidium mucronatum | T | BRIP 60097 | MW049275 | NA | NA | Rosa rubiginosa | this paper |

| Phragmidium tormentillae (≡Frommeëlla tormentillae) | (T) | BPI 843392 (U3) | DQ354553 | DQ354552 | MG907265 | Potentilla canadensis | Aime (2006); Aime et al. (2018a) |

| Pileolaria brevipes | PUR N16525 (MCA3477):28S, CO3; BPI 877989 (MCA3223):18S | MG907216 | MW049301 | MG907267 | Toxicodendron sp. | Aime et al. (2018a); this paper | |

| Pileolaria shiraiana | BRIP 58344 | KJ651957 | NA | NA | Rhus japonica | Doungsa-ard et al. (2018) | |

| Pileolaria terebinthi | T | PUR N11686 (U1282) | KY796222 | NA | NA | Pistacia terebinthus | Ishaq et al. (2019) |

| Porotenus biporus | * | ZT Myc 3414 | JF263494 | JF263510 | NA | Memora flavida | Beenken et al. (2012) |

| Prospodium appendiculatum | T | BPI 879956 (U753) | MW049276 | NA | NA | Tecoma stans | this paper |

| Prospodium lippiae | BPI 843901 (U152) | DQ354555 | DQ831024 | NA | Aloysia polystachya | Aime (2006) | |

| Prospodium tuberculatum | BRIP 57630 | KJ396195 | KJ396196 | MW036504 | Lantana camara | Pegg et al. (2014); this paper | |

| Puccinia graminis | T | BRIP 60137 | KM249852 | MW049302 | MW036505 | Glyceria maxima | McTaggart et al. (2016); this paper |

| Pucciniastrum epilobii | T | PUR N11088 (MCA5308) | MW049277 | NA | NA | Epilobium angustifolium | this paper |

| Pucciniastrum minimum | BRIP 57654 | KC7633401 | KT199391 | KT199422 | Vaccinium corymbosum | McTaggart et al. (2016) | |

| Pucciniosira pallidula | * | BPI 863541 (U282) | DQ354534 | MW049303 | NA | Triumfetta semitriloba | Aime (2006); this paper |

| Pucciniosira solani | n.d. | EU851137 | NA | NA | Solanum aphyodendron | Zuluaga et al. unpublished | |

| Puccorchidium polyalthiae | T | ZT HeRB 251 | JF263493 | JF263509 | JF263525 | Polyalthia longifolia | Beenken & Wood (2015) |

| Ravenelia sp. | * | PUR F19717 | MW147024 | MW166323 | MW166322 | Tephrosia sp. | this paper |

| Rogerpetersonia torreyae (as Caeoma torryeyae) | T | BPI 877825 (U1168):28S,CO3; BPI 877824 (U808):18S | MG907207 | MG907197 | MG907254 | Torreya californica | Aime et al. (2018a) |

| Rossmanomyces pyrolae (as Chrysomyxa pyrolae) | T | 390CHPPCGVF1 | FJ666456 | NA | NA | n.d. | Vialle et al. (2009) |

| Skierka diploglottidis | * | BRIP 59646 | MW049278 | MW049304 | MW036506 | Dictyoneura obtusa | this paper |

| Skierka robusta | * | BPI 879954 (U747) | MW049279 | MW049305 | NA | Rhoicissus rhomboidea | this paper |

| Sorataea arayatensis | U416 | MW049280 | NA | NA | Derris elliptica | this paper | |

| Sphaerophragmium acaciae | T | BRIP 56910 | KJ862350 | KJ862429 | KJ862462 | Albizzia sp. | McTaggart et al. (2015) |

| Sphenorchidium xylopiae | T | n.d. | KM217355 | KM217372 | NA | Xylopia aethiopica | Beenken & Wood (2015) |

| Sphenospora kevorkianii | BPI 863558 (U10) | DQ354521 | DQ354520 | NA | Stanhopea candida | Aime (2006) | |

| Stereostratum corticioides | T | BPI 842314 (U27) | MW049281 | MW049306 | NA | Bambusa sp. | this paper |

| Stomatisora psychotriicola | * | PREM 60886 | NG059953 | NA | NA | Psychotria capensis | Wood et al. (2014) |

| Tegillum scitulum (as Olivea scitula) | * | BPI 871108 (U668) | DQ354541 | DQ354540 | NA | Vitex doniana | Aime (2006) |

| Thekopsora areolata | T | n.d. | KJ546894 | NA | NA | Picea engelmannii | Kaitera et al. unpublished |

| Trachyspora intrusa | T | BPI 84328 (MCA2384) | DQ354550 | DQ354549 | MW036508 | Alchemilla vulgaris | Aime (2006); this paper |

| Tranzschelia discolor | * | BRIP 57662 | KR995082 | KR994969 | KR995082 | Prunus persica | Doungsa-ard et al. (2018) |

| Tranzschelia mexicana | * | KR-M-0040855 | KP308391 | NA | NA | Prunus salicifolia | Blomquist et al. (2015) |

| Triphragmium ulmariae | T | BPI 881364 (MCA2378):28S; n.d.:18S | JF907676 | AY125401 | NA | Filipendula ulmaria | Yun et al. (2011); Wingfield et al. (2004) |

| Uredinopsis filicina | T | WM112 | AF426237 | NA | NA | Phegopteris connectilis | Maier et al. (2003) |

| Uredo cryptostegiae (as Maravalia cryptostegiae) | BRIP 56898 | KT199401 | KT199387 | KT199412 | Cryptostegia grandiflora | McTaggart et al. (2016) | |

| Uredo elephantopodis | BRIP 58415 | MW049283 | NA | MW036509 | Elephantopus scaber | this paper | |

| Uredo hiulca | BRIP 53244 | MW049284 | NA | MW036510 | Dioscorea transversa | this paper | |

| Uredo trichosanthis | PUR N3445 | MW049285 | MW049309 | NA | Trichosanthes bracteata | this paper | |

| Uredopeltis atrides | * | PUR N13866 (U454) | MW049286 | NA | NA | Grewia flavescens | this paper |

| Uredopeltis chevalieri | * | BRIP 56924 | MW049287 | NA | NA | Grewia retusifolia | this paper |

| Uromyces appendiculatus | T | BRIP 60020 | KM249870 | DQ354510 | KX999933 | Phaseolus vulgaris | Aime (2006); McTaggart et al. (2014) |

| Uromycladium simplex | T | BRIP 59214 | KJ632990 | KJ633029 | KJ639078 | Acacia pycnantha | Doungsa-ard et al. (2014) |

| Uropyxis daleae | * | BPI 910337 | KY798364 | NA | NA | Dalea pringlei | Demers & Castlebury unpublished |

| Uropyxis diphysae | * | BPI 864148 | MW049288 | NA | NA | Diphysa americana | this paper |

| Xenodochus carbonarius | T | PUR N15566 (U1534) | MW049289 | NA | NA | Sanguisorba officinalis | this paper |

| Xenostele litseae | * | BRIP 53335 | MW049290 | MW049310 | NA | Neolitsea dealbata | this paper |

| Ypsilospora tucumanensis | * | BPI 863688 | MW049291 | NA | NA | Inga sp. | this paper |

| Zaghouania notelaeae (as Cystopsora notelaeae) | * | BRIP 58325 | KT199396 | KT199384 | KT199407 | Notelaea microcarpa | McTaggart et al. (2016) |

aType Status: T = type species for the genus; * = proxy for generic type (see methods for explanation).

bnumbers in parentheses are collection numbers, preceded by herbarium accession numbers. When sequences from more than one collection are used, data are separated by a /.

n.d. = no data.

NA = not applicable.

bold = new sequences generated for this paper.

With the overview tree as a guide, we divided the data into three subsets, Melampsorineae (73 species), Raveneliineae (77 species) and Uredinineae (164 species), for additional sampling and analyses (Table S1). In expanded sampling, we included taxa only sequenced for one of the three loci in order to broaden both generic representation and species representation for polyphyletic genera. Trees were rooted from the sister lineage as shown by the overview tree, or, in the case of Raveneliineae, midpoint rooted.

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

DNA was extracted from fresh or herbarium material with the UltraClean Plant DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., Solana Beach, CA, U.S.A.). The nuclear large subunit (28S) region of the ribosomal DNA repeat was amplified with Rust2INV (Aime 2006)/LR6 or LR7 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) and, for weak products, nested with Rust28SF (Aime et al. 2018a)/LR5 or LR6 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) following the protocols of Aime et al. 2018a. The small subunit (18S) region of the ribosomal DNA repeat was amplified with NS1 (White et al. 1990)/Rust 18S-R (Aime 2006) and nested with RustNS2-F (Aime et al. 2018a)/NS6 (White et al. 1990) following the protocols of Aime et al. (2018a). Cytochrome-c-oxidase subunit 3 (CO3) of the mitochondrial DNA was amplified with CO3_F1/CO3_R1 (Vialle et al. 2009) following the protocols of Vialle et al. (2009). PCR products were cleaned and sequenced with the amplification primers by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) or Beckman Coulter Sequencing (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). Sequences were edited in Sequencher v. 4.5–5.4 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) and verified by BLASTn against the NCBI database (Altschul et al. 1990). Sequence accession numbers are provided in Tables 1 and S1.

Phylogenetic analyses

The 28S, 18S and CO3 sequences were aligned in four datasets, (i) Pucciniales overview, (ii) Melampsorineae, (iii) Raveneliineae, and (iv) Uredinineae with the GUIDANCE2 webserver (Sela et al., 2015; available at http://guidance.tau.ac.il/ver2/credits.php) (alignments are available from TreeBASE, study TB2:S27114). The aligned loci were concatenated and run as partitioned datasets with maximum likelihood (ML). We searched for the most likely tree in IQTree v. 1.7 beta (Nguyen et al. 2015) with a GTR gamma FreeRate heterogeneity model of evolution and a different rate for each partition (command -spp -m GTR+R), 10 000 ultrafast bootstraps (Hoang et al. 2018), an approximate likelihood ratio test with 10 000 replicates (Guindon et al. 2010) and genealogical concordance factors calculated from each locus (Minh et al. 2018).

We used the concatenated three-locus alignment of the familial-overview dataset to estimate the divergence dates of genera with BEAST v. 2.5 (Bouckaert et al. 2019). We calibrated the most recent common ancestor of the Pucciniales at 175 M yr and the Melampsorineae at 91 M yr based on Aime et al. (2018a). The dating analyses were constrained to the topology of the ML tree, and run for 150 M generations, with a BEAST model test for each partition and a relaxed log normal clock. Convergence of all priors was visualised in Tracer v. 1.7 (Rambaut et al. 2018) and 135 001 trees were summarised with TreeAnnotator, part of the BEAST v. 2.5 package.

We attempted to provide better resolution of genera and families within Raveneliineae by multiple means including removal of incongruent (rogue) taxa, constructing alignments with stricter and weaker gap opening penalties, pruning taxa with missing sequence data, removal of 18S and CO3 loci, and rooting with different outgroups from the Melampsorineae and Uredinineae. The 28S data of Raveneliineae were analysed with SplitsTree4 (Huson & Bryant 2005) to visualize the evolution as a network in order to determine if groups were supported when not constrained by dichotomous evolution as imposed by ML analyses.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses

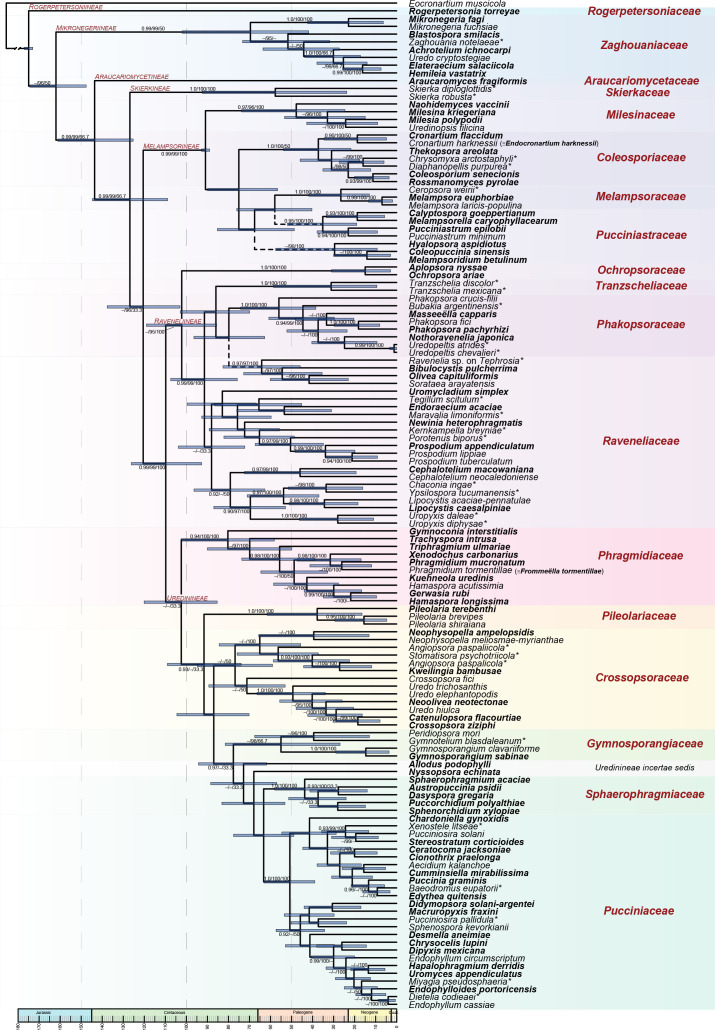

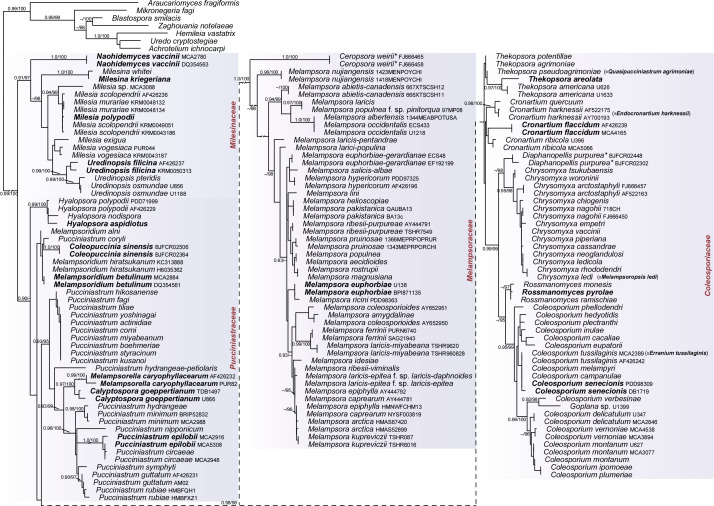

The ML tree based on three concatenated loci (Fig. 1) was mostly congruent with prior studies of more limited taxon and locus sampling (Aime 2006, Beenken & Wood 2015, McTaggart et al. 2016, Aime et al. 2017, Aime et al. 2018a, Beenken 2017, Souza et al. 2018). Sampled trees constrained to the ML topology in the dating analyses converged after 150 M generations, supported by all effective sample size values over 200. We recovered support for placement of previously unsupported or unplaceable taxa such as Tranzschelia. Newly sequenced taxa resolved include the rust fungi on Agathis, genera such as Elateraecium, Masseeëlla, and Skierka, and most of the endocyclic Pucciniosiraceae. Despite numerous attempts with different alignments and taxon selection, some families/genera could not be confidently resolved, namely: Pucciniastrum and Pucciniastraceae; Raveneliaceae; and Allodus, Neopuccinia, and Nyssopsora within Uredinineae. SplitsTree analysis of Raveneliineae recovered a star-shaped pattern of reticulate edges indicative of multiple competing hypotheses of evolution for this lineage (Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

Pucciniales. Phylogram obtained from BEAST constrained to a ML topology from three concatenated loci (28S, 18S, and CO3). The tree is rooted with Eocronartium muscicola. Families are indicated by coloured blocks; dashed lines indicate uncertainty at the referenced nodes. Genera represented by types are indicated in bold; genera represented by type proxies (as explained in methods) are indicated by *. Support for nodes is provided from an approximate likelihood ratio test (≥ 0.90), ultrafast bootstraps (≥ 95 %) and genealogical concordance factors for the three loci at each node as aLRT/UFBoot/gCF.

Taxonomy

Families and sub-orders treated here show strong support at their most recent common ancestor, with the exception of Pucciniastraceae and Raveneliaceae (Figs 1–3). We propose four new suborders (Araucariomycetineae, Raveneliineae, Rogerpetersoniineae, and Skierkineae), seven new families (Araucariomycetaceae, Crossopsoraceae, Milesinaceae, Ochropsoraceae, Rogerpetersoniaceae, Skierkaceae, and Tranzscheliaceae) and four new genera (Araucariomyces, Neoolivea, Rogerpetersonia, and Rossmanomyces); 21 new combinations and one new name are made for species. Suborders and families are arranged from earliest diverging to more recently derived (Fig. 1). We use the terms gametothallus and sporothallus as applied by Berndt (2018) and use the notation 0-I [for spermogonial (0) and aecial (I) stages] to denote the gametothallus, and II-III [for uredinial (II) and telial (III) stages] to denote the sporothallus. We follow the ontogenic system for sorus terminology, which emphasizes function in the life cycle and the nuclear cycle over morphology, as refined by Hiratsuka (1973). Morphological terms for spermogonia follow Hiratsuka & Cummins (1963); terms for aecial and uredinial sori follow the descriptions for asexual genera in Cummins & Hiratsuka (2003) but are indicated in lowercase, non-italics, to delineate use as descriptive terms from generic names.

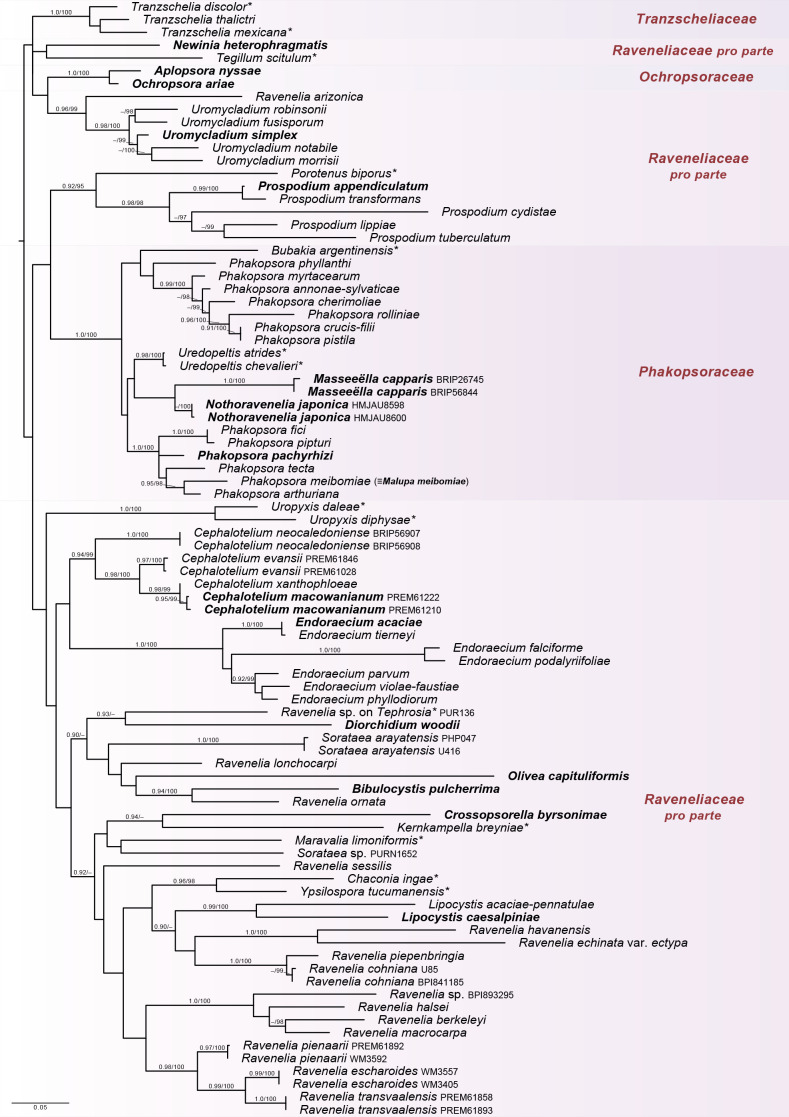

Fig. 3.

Raveneliineae. ML topography generated from 28S with expanded taxon sampling. The tree is mid-point rooted. Families are indicated by colour blocks; Raveneliaceae is not resolved. Only 26 of the estimated 45+ genera in this suborder are represented by types (indicated in bold) and type proxies (indicated by *), and poor resolution may be attributable to missing data (both locus and taxon sampling), combined with long branch lengths (Fig. S2) in this lineage. Support for nodes is provided from an approximate likelihood ratio test (≥ 0.90) and ultrafast bootstraps (≥ 95 %) as aLRT/UFBoot.

Rogerpetersoniineae Aime & McTaggart, subord. nov. MycoBank MB836604.

Type family: Rogerpetersoniaceae Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other Pucciniales in that gametothalli are formed on Taxaceae.

Description: With the characteristics of Rogerpetersoniaceae.

Included family: Rogerpetersoniaceae.

Rogerpetersoniaceae Aime & McTaggart, fam. nov. MycoBank MB836605.

Type genus: Rogerpetersonia Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other Pucciniales in that gametothalli are formed on Taxaceae.

Description: With the characteristics of Rogerpetersonia.

Included genus: Rogerpetersonia.

Host family: Taxaceae (0-I); II-III unknown.

Rogerpetersonia Aime & McTaggart, gen. nov. MycoBank MB836606.

Type species: Rogerpetersonia torreyae (Bonar) Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Etymology: In honour of Roger Peterson, botanist, ecologist, mycologist and plant pathologist, who pioneered studies on Southern Hemisphere conifer rusts.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other rust fungi in forming gametothalli on Taxaceae (Torreya).

Description: With the characteristics of Rogerpetersonia torreyae.

Rogerpetersonia torreyae (Bonar) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836608.

Basionym: Caeoma torreyae Bonar, Mycologia 43: 62. 1951.

Description: Rogerpetersonia torreyae is described and illustrated as C. torreyae in Peterson (1974). Spermogonia are deep-seated, periphysate, otherwise similar to Group III (type 12). Aecia petersonia-like, i.e., without peridium or intercalary cells. Sporothallus unknown.

Notes: Caeoma, as typified by C. berberidis, is a synonym of Puccinia (Aime et al. 2018b), necessitating a new name for the only known rust fungus that infects Torreya. Peterson (1974) hypothesized that R. torreyae belonged to an undescribed early diverging lineage of Pucciniales. Subsequent analyses have shown that R. torreyae is the earliest diverging extant rust sequenced to date and holds an isolated position within Pucciniales (Aime 2006, Aime et al. 2018a) (Fig. 1). No alternate host is known for this rust and it is likely that R. torreyae has adapted to cause systemic infections in the gametothallus host in order to compensate for loss of a sporothallus.

Mikronegeriineae Aime, Mycoscience 47: 120. 2006.

Description: With the characteristics of the family.

Included family: Zaghouaniaceae.

Zaghouaniaceae P. Syd. & Syd., Monogr. Uredin. (Lipsiae) 3(3): 586. 1915. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Synonyms: Hemileieae Dietel, Uredinales in Engler and Prantl., Naturl.: 51. 1928.

Mikronegeriaceae Cummins & Y. Hirats. (as ‘Micronegeriaceae’), Illustr. Gen. Rust Fungi, rev. Edn (St. Paul): 13. 1983.

Type genus: Zaghouania Pat., Bull. Soc. mycol. Fr. 17: 187. 1901.

Description: Spermogonia most often Group III (type 12) (deep seated and non-periphysate), but periphyses noted for some; aecia most commonly of the petersonia-type, i.e., without peridium or intercalary cells, however in Elateraecium accompanied with specialized elaters; uredinia most often uredo-type, in Elateraecium with a weakly developed peridium in young sori; teliospores without dormancy, germinating externally by apical growth, or internally (Achrotelium). Blastospora and Mikronegeria are heteroecious and macrocyclic, Elateraecium and Zaghouania are autoecious and macro- or demi-cyclic; complete life cycles unknown for Achrotelium, Botryorhiza and Hemileia.

Included genera: Achrotelium, Blastospora, Botryorhiza, Elateraecium (= Hiratsukamyces), Hemileia, Mikronegeria, Zaghouania (= Cystopsora); likely includes Desmosorus.

Host families: Araucariaceae, Betulaceae (0-I heteroecious species); Apocynaceae, Araliaceae, Capparidaceae, Celastraceae, Cupressaceae, Dioscoreaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fagaceae, Oleaceae, Orchidaceae, Rubiaceae, Smilacaceae, Verbenaceae (II-III and autoecious species).

Notes: The family Mikronegeriaceae accommodated the heteroecious rust genera Mikronegeria, Blastospora, and Chrysocelis, which have thin-walled basidia that germinate externally without dormancy (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). Hemileia and some Maravalia species formerly placed in Chaconiaceae that share the feature of substomatal sori without paraphyses or peridium, also belong here (Aime 2006). Two additional genera, Achrotelium and Zaghouania (as Cystopsora), were included by McTaggart et al. (2016). Zaghouaniaceae, long considered a synonym for Pucciniaceae (e.g., Kirk et al. 2008), has priority over Mikronegeriaceae and the family is now referred to by the earlier name. The current study adds Elateraecium (syn. Hiratsukamyces; Aime et al. 2018b), whereas Chrysocelis is resolved within the Pucciniaceae (Fig. 4). The formation of basidia is primarily external by apical growth and spermogonia are primarily deep-seated Group III (type 12), or if periphysate, similar to Group V (type 4).

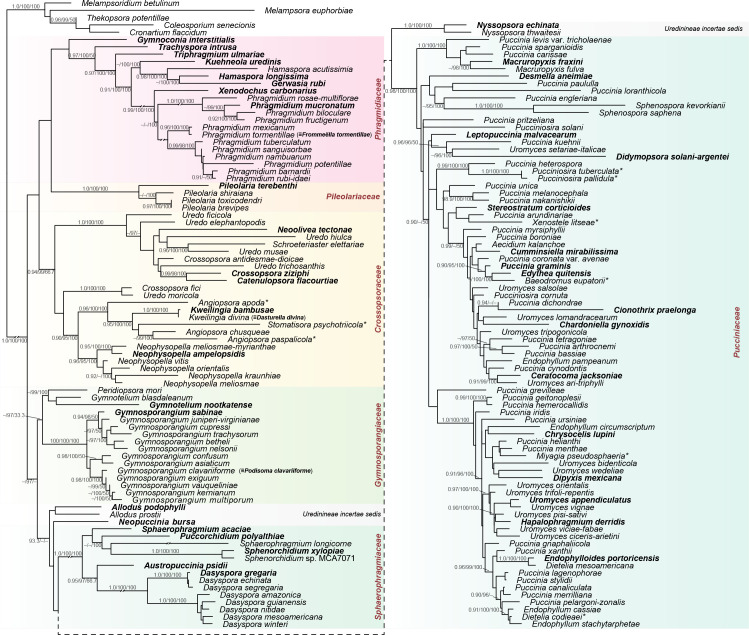

Fig. 4.

Uredinineae. ML topography generated from three concatenated loci (28S, 18S, and CO3) with expanded taxon sampling. The tree is rooted with Melampsorineae. Six families are resolved and indicated by coloured blocks; three genera are unresolved to family and indicated as incertae sedis. Genera represented by types are indicated in bold; genera represented by type proxies (as explained in methods) are indicated by *. Support for nodes is provided from an approximate likelihood ratio test (≥ 0.90), ultrafast bootstraps (≥ 95 %) and genealogical concordance factors for the three loci at each node as aLRT/UFBoot/gCF.

Uredo cryptostegiae (syn. Maravalia cryptostegiae; Scopella cryptostegiae), which has been used as a biocontrol agent for rubber-vine (Cryptostegia grandiflora) is placed in Zaghouaniaceae (Fig. 1). Cummins (1950) transferred M. cryptostegiae to Scopella, while hypothesizing that the rust might belong to Hemileia. Most later workers considered Scopella and Maravalia congeneric and Scopella fell out of use. The type of Maravalia, M. pallida occurs on Fabaceae and is now placed in Raveneliineae. The type of Scopella, S. echinulata, is a subepidermal rust on Sapotaceae (Mains 1939a). Uredo cryptostegiae, which is not congeneric with Maravalia (as represented by M. limoniformis, Fig. 1), is most appropriately retained in Uredo until type data from S. echinulata is obtained.

Zaghouania notelaeae (Syd.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836655.

Basionym: Cystopsora notelaeae Syd., Annls mycol. 35: 351. 1937.

Notes: Zaghouania contains two other species of rust fungi on Oleaceae with pale-walled teliospores that germinate without dormancy (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). There is little to differentiate Cystopsora and Zaghouania (Thirumalachar 1945, Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003) and we treat Cystopsora as a synonym of Zaghouania.

Araucariomycetineae Aime & McTaggart, subord. nov. MycoBank MB836623.

Type family: Araucariomycetaceae Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other Pucciniales in forming gametothalli on Agathis.

Description: With the characteristics of Araucariomycetaceae.

Included family: Araucariomycetaceae.

Araucariomycetaceae Aime & McTaggart, fam. nov. MycoBank MB836624.

Type genus: Araucariomyces Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other Pucciniales in forming gametothalli on Agathis.

Description: With the characteristics of Araucariomyces.

Included genus: Araucariomyces.

Host family: Araucariaceae (0-I); II-III unknown.

Araucariomyces Aime & McTaggart, gen. nov. MycoBank MB836625.

Type species: Araucariomyces fragiformis (Ces.) McTaggart, R.G. Shivas & Aime, this paper.

Entomology: From the host family, Araucariaceae.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other rust genera in forming the gametothallus on species of Agathis (Araucariaceae).

Description: These species are described and illustrated in Peterson (1966). Spermogonia amphigenous, intra-epidermal becoming sub-epidermal as they break through host walls, convex hymenium; similar to Group 1 (type 1) but with scant periphyses not visible in all mounts, similar to Rogerpetersonia. Aecia peridiate, aecidium-type, deep-set within swollen host tissues. Sporothallus unknown. On leaves of Agathis (Araucariaceae). Two known species.

Notes: Two rust fungi with cupulate aecia on Agathis spp., formerly placed in the form-genus Aecidium, belong here. Our analyses consistently place these in a lineage separate from all other sequenced Pucciniales (Fig. 1). Despite over a decade of sampling rust fungi from Australia and Southeast Asia on hosts co-distributed with Agathis species, we have been unable to locate a telial state for these rusts. Peterson (1968) ruled out the possibility that Araucariomyces represents an endocyclic form, because aeciospores of Ar. balansae germinate to produce germ tubes rather than basidia. As is conjectured with Rogerpetersonia, the life cycle may not produce a sporothallus, and instead has adapted to systemically infect their hosts possibly including a cryptic sexual or parasexual cycle.

Araucariomyces balansae (Cornu) McTaggart, R.G. Shivas & Aime, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836626.

Basionym: Aecidium balansae Cornu., Bull. Soc. mycol. Fr. 3: 173. 1887.

Synonym: Peridermium balansae (Cornu) Sacc., Syll. Fung. 9: 326. 1891.

Araucariomyces fragiformis (Ces.) McTaggart, R.G. Shivas & Aime, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836627.

Basionym: Aecidium fragiforme Ces., Atti Accad. Sci. fis. mat. Napoli 8: 26. 1879.

Skierkineae Aime & McTaggart, subord. nov. MycoBank MB836628.

Type family: Skierkaceae Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other rust fungi in that sporothalli sori are deep-seated and subepidermal with mature uredinio- and teliospores single-celled and non-catenulate, these forced through a narrow sorus opening by the production of new spores from sporogenous cells from which they are detached before extrusion.

Description: With the characters of Skierkaceae.

Included family: Skierkaceae.

Skierkaceae (Arthur) Aime & McTaggart, fam. & stat. nov. MycoBank MB836629.

Basionym: Skierkatae Arthur, North American Flora 7(10): 704. 1926.

Type genus: Skierka Racib., Parasit. Alg. Pilze Javas (Jakarta) 2: 30. 1900.

Diagnosis: Differs from all other rust fungi in that sporothalli sori are deep-seated and subepidermal with mature uredinio- and teliospores single-celled and non-catenulate, these forced through a narrow sorus opening by the production of new spores from sporogenous cells from which they are detached before extrusion.

Description: With the characteristics of Skierka as described and illustrated in Mains (1939b). Spermogonia deep-seated with convex hymenium, subepidermal, periphysate; aecia and uredinia uredo-type; teliospores strongly adherent, extruded in hair-like columns, germination external, without dormancy. Autoecious and macrocyclic.

Included genus: Skierka.

Host families: Burseraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Sapindaceae.

Notes: Skierka species are tropical and autoecious (Mains 1939c, Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). All sori are subepidermal and deep-seated; non-catenulate teliospores are extruded in hair-like columns. Skierka has long held an isolated placement within Pucciniales. Arthur (1907–1931) and Dietel (1928) placed Skierka in a separate subfamily or tribe, respectively, in the Pucciniaceae; Cummins & Hiratsuka (2003) treat it as incertae sedis within the rusts. Mains (1939c) hypothesised that Skierka represented an intermediate taxon between the Melampsoraceae and Pucciniaceae (equivalent to the subordinal ranks Melampsorineae and Raveneliineae/Uredinineae, under the present classification), a position largely congruent with our placement (Fig. 1).

Melampsorineae Aime, Mycoscience 47: 120. 2006.

Type family: Melampsoraceae Dietel, in Engler & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 1(1): 38. 1897.

Description: Mostly macrocyclic and heteroecious, forming the gametothallus on species of Pinaceae. Teliospores germinate after a period of dormancy.

Included families: Coleosporiaceae, Melampsoraceae, Milesinaceae, Pucciniastraceae.

Milesinaceae Aime & McTaggart, fam. nov. MycoBank MB836630.

Type genus: Milesina Magnus, Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 27: 325. 1909.

Diagnosis: Similar to other Melampsorineae, differing in either production of colourless urediniospores in species that infect ferns, or in production of milesia-type aecia in species that infect Ericaceae.

Description: With typically colourless sori, although urediniospores of Naohidemyces are orange, otherwise similar to Pucciniastraceae. Spermogonia Group I (mostly type 1, also type 2 and 3); aecia peridermium-type, milesia-type in Naohidemyces; uredinia milesia-type. Teliospores with dormant germination, 1- to many-celled, barely differentiated, sometimes laterally adherent, typically formed within host epidermal cells. Most species macrocyclic and heteroecious with sporothalli on ferns (excepting Naohidemyces on Ericaceae), and gametothalli on Pinaceae.

Included genera: Milesia, Milesina, Naohidemyces, Uredinopsis.

Host families: Pinaceae (Abies, Tsuga) (0-I); Ericaceae and some ferns in Polypodiales and Lygodium (II-III).

Notes: Early workers considered rust fungi on early diverging plant hosts (i.e., ferns) to be the “ancestral” Pucciniales. Several molecular phylogenetic studies have shown this not to be the case (e.g., Sjamsuridzal et al. 1999). However, the fern rusts are among the earliest diverging members of Melampsorineae (Fig. 2), the second major radiation of the rust fungi, and belong to the two earliest families in this suborder (Milesinaceae and Pucciniastraceae). Most of the species in Milesinaceae form sporothalli on fern species, except for Naohidemyces, which alternates between Tsuga and Vaccinium.

Fig. 2.

Melampsorineae. ML topography generated from three concatenated loci (28S, 18S, and CO3) with expanded taxon sampling. The tree is rooted with Araucariomycetaceae and Zaghouaniaceae. Four families are indicated by coloured blocks; Pucciniastraceae is recovered as a grade in these analyses. Genera represented by types are indicated in bold; genera represented by type proxies (as explained in methods) are indicated by *. Support for nodes is provided from an approximate likelihood ratio test (≥ 0.90) and ultrafast bootstraps (≥ 95 %) as aLRT/UFBoot.

Aime et al. (2018b) recommended protecting the name Milesina Magnus over Milesia F.B. White. However, our data show that the type of Milesina, M. kriegeriana (Magnus) Magnus, is not congeneric with the type of Milesia, M. polypodii F.B. White (Fig. 2), thus we recommend retaining both genera at this time. Should future work demonstrate that Uredinopsis is polyphyletic, then disposition of these taxa will need revision.

Coleosporiaceae Dietel, In: Engler & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., Teil. I (Leipzig) 1: 548. 1900. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Synonym: Cronartiaceae Dietel, in Engler and Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 1(1) (Suppl.): 548. 1900.

Type genus: Coleosporium Lév., Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. III, Ser. 8: 373. 1847.

Description: Spermogonia Group I (type 2 or 3) (but Group II, type 9 in Cronartium); aecia of peridermium-type; uredinia either of caeoma-type or milesia-type. Teliospores packed to loosely adherent, often extruded in columns and/or gelatinous; not dormant, with external germination. Most are heteroecious and macrocyclic, with some derived microcyclic or endocyclic species.

Included genera: Chrysomyxa, Coleosporium, Cronartium, Diaphanopellis, Rossmanomyces, Thekopsora (= Quasi-pucciniastrum).

Host families: Pinaceae (primarily Pinus) (0-I); various, including Apocynaceae, Asteraceae, Campanulaceae, Convolvulaceae, Ericaceae, Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Rutaceae, Violaceae (II-III).

Notes: Coleosporiaceae was shown to include Cronartiaceae (Aime 2006) as well as Thekopsora s.s. (Aime et al. 2018a). Aecia are peridermium-type in contrast to most Milesinaceae. Telial states show variable morphology but tend to form the sporothallus on herbaceous rather than woody plants (cf. Pucciniastraceae) or ferns. Dietel (1900) established both Coleosporiaceae and Cronartiaceae in the same publication. We follow Sydow & Sydow (1915) in applying Coleosporiaceae over Cronartiaceae, which is discussed in Aime (2006). Endocronartium is a later synonym of Cronartium (Aime et al. 2018b).

Rossmanomyces Aime & McTaggart, gen. nov. MycoBank MB836632.

Type species: Rossmanomyces pyrolae (Rostr.) Aime & McTaggart, this paper.

Etymology: In honour of Amy Rossman, biologist, mycologist, plant pathologist, and mentor.

Diagnosis: Similar to Chrysomyxa but differs in forming a systemic sporothallus; differs from all other rust fungi in forming sporothalli on Moneses and Orthilia (Ericaceae).

Description: See Saville (1950) and Feau et al. (2011). Gametothalli systemic in cones of Picea species; sporothalli systemic in Moneses, Orthilia, and Pyrola species.

Rossmanomyces monesis (Ziller) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836633.

Basionym: Chrysomyxa monesis Ziller, Canad. J. Bot. 32: 435. 1954.

Rossmanomyces pyrolae (Rostr.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836634.

Basionym: Chrysomyxa pyrolae Rostr., Botan. Zbl. 5: 127. 1881.

Rossmanomyces ramischiae (Lagerh.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836635.

Basionym: Chrysomyxa ramischiae Lagerh., Svensk bot. Tidskr. 3: 26. 1909.

Notes: Chrysomyxa is typified by C. abietis, a microcyclic species for which there are no sequence data. In our analyses (Fig. 2) most species of Chrysomyxa were monophyletic, excluding C. weirii now placed in Ceropsora, and species that infect wintergreens, now placed in Rossmanomyces. The species of Rossmanomyces are the only known rust species that form sporothalli on species of Moneses and Orthilia, and the only Coleosporiaceae that form sporothalli on species of Pyrola. The gametothalli are produced on Picea and are systemic within the cones, in contrast to gametothalli of Chrysomyxa species, which infect needles.

Thekopsora americana (Farl.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. et stat. nov. MycoBank MB836637.

Basionym: Pucciniastrum arcticum var. americanum Farl., Rhodora 10: 16. 1908.

Synonym: Pucciniastrum americanum (Farl.) Arthur, Bull. Torrey bot. Club 47: 468. 1920.

Thekopsora potentillae (Korn.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836636.

Basionym: Pucciniastrum potentillae Korn., in Jaczewski et al., Fungi Rossiae Exsicc. fasc. 7: 327. 1900 [1899].

Notes: Delimitation between Thekopsora and Pucciniastrum has never been satisfactory (e.g., Hiratsuka 1958, Sato et al. 1993). While prior works mostly consider these confamilial or even congeneric, Thekopsora s.s., as typified by T. areolata, belongs to Coleosporiaceae (Aime et al. 2018a; Fig. 2). New combinations are proposed for ex-Pucciniastrum species. Other former Thekopsora species, such as P. minima and P. rubiae are placed in Pucciniastraceae (Fig. 2).

Thekopsora pseudoagrimoniae Aime & McTaggart, nom. nov. MycoBank MB836638.

Basionym: Quasipucciniastrum agrimoniae X.H. Qi et al., Mycology 10(3): 145. 2019.

Description: See Qi et al. (2019).

Notes: The recently described monotypic Quasipucciniastrum based on Q. agrimoniae is congeneric with Thekopsora (Fig. 2). In addition to the phylogenetic data, Quasipucciniastrum shares key morphological features, ecology, and hosts with Thekopsora. This paper highlights the importance of including type species and adequate sampling in phylogenetic studies of known polyphyletic genera. The name Thekopsora agrimoniae Dietel is already in use, thus a new name is proposed for this taxon. However, there is little to differentiate T. pseudoagrimoniae from T. agrimoniae and the two may be conspecific.

Pucciniastraceae Gäum. ex Leppik, Ann. bot. fenn. 9: 139. 1972. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Type genus: Pucciniastrum G.H. Otth, Mitt. Naturforsch. Ges. Bern 1861: 71. 1861.

Description: Similar to Milesinaceae, but most species with cytoplasmic pigmentation, at least within urediniospores. Spermogonia Group I (type 2 or 3). Aecia peridermium-type; uredinia milesia-type. Telia undergo dormancy with external germination; either formed within epidermal cells, or as a subepidermal crust, which is gelatinous in Coleopuccinia. Most species heteroecious, macrocyclic; Calyptospora is demicyclic, Coleopuccinia is microcylic, producing only teliospores.

Included genera: Calyptospora, Coleopuccinia, Hyalopsora, Melampsorella, Melampsoridium, Pucciniastrum.

Host families: Pinaceae (Abies, Larix, Picea, Tsuga) (0-I); Aceraceae, Betulaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Ericaceae, Fagaceae, Onagraceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae and some ferns in the Polypodiales (II-III).

Notes: Most species of Pucciniastraceae produce spores with pigmented cytoplasm and telia that may be subepidermal, in contrast to Milesinaceae. Hyalopsora is the only genus in Pucciniastraceae that infects ferns. Coleopuccinia is known only from teliospores (Cao et al. 2018). Pucciniastraceae s.l. has been difficult to resolve and appears polyphyletic with varying degrees of support in earlier studies (e.g., Maier et al. 2003, Aime 2006, Aime et al. 2016a, Ji et al. 2019). In this work, we find weak support for Pucciniastraceae in some analyses (data not shown) but not all (e.g., Fig. 1). In nearly all analyses Pucciniastraceae is resolved into two groups: (i) Calyptospora, Melampsorella, and Pucciniastrum; and (ii) Coleopuccinia, Hyalopsora, and Melampsoridium. These often form a grade (Fig. 2) and may or may not represent separate family-rank lineages. Pending additional analyses, we broadly define Pucciniastraceae to include both groups. Pucciniastrum is also difficult to resolve with confidence, and is most likely paraphyletic, even after removing the ex-Pucciniastrum elements that were reassigned to Thekopsora (Fig. 2). We retain Coleopuccinia, Calyptospora, and Melampsorella at this time, although future work may show that the latter two are synonyms for Pucciniastrum.

Melampsoraceae Dietel, in Engler & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., Teil. I (Leipzig) 1: 38. 1897.

Type genus: Melampsora Castagne, Obs. Plantes Acotylédonées Fam. Urédinié 2: 18. 1843.

Description: Spermogonia Group I (type 2 or 3). Aecia mostly caeoma-type; uredinia uredo-type. Teliospores subepidermal, laterally adherent in crusts, 1-celled, often with a sterile basal cell; germination external or semi-external (Ceropsora). Most species heteroecious, macrocyclic; Ceropsora species are microcyclic.

Included genera: Melampsora; likely includes Ceropsora.

Host families: Primarily Pinaceae (0-I); primarily Salicaceae, also Apocynaceae, Asteraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Hypericaceae, Linaceae, Passifloraceae, Saxifragaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Thymelaeaceae (II-III)

Ceropsora weirii (H.S. Jacks.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836631.

Basionym: Chrysomyxa weirii H.S. Jacks., Phytopathology 7: 353. 1917.

Notes: Most of the ca. 30 species of Chrysomyxa are heteroecious with gametothalli on Pinaceae and are allied within Coleosporiaceae (Fig. 2). Chrysomyxa weirii, an autoecious microcyclic pathogen of Picea species, is unique among described Chrysomyxa in forming laterally adherent teliospores that act as diaspores, are adapted for dispersal in water, and germinate to produce 2-celled basidia (Crane 2000, Crane et al. 2000). Crane et al. (2000) conjectured that Ch. weirii is not a true Chrysomyxa, which is supported with molecular data (Feau et al. 2011, Aime et al. 2018a, Fig. 2). The type and only other species of Ceropsora, C. picea, is a teliospore-only species infecting Picea in India (Bakshi & Singh 1960). While we have been unable to sequence a representative of the type species, C. weirii and C. picea are both microcyclic producing telia on Picea species. In both species, the telia contain some thin-walled sterile cells on the sides that have been interpreted as remnants of a peridermium. And in both, teliospores are subtended by sterile basal cells forming initially adherent crusts that separate at dispersal; germination is semi-external (Bakshi & Singh 1960, Crane et al. 2000).

Raveneliineae Aime & McTaggart subord. nov. MycoBank MB836639.

Type family: Raveneliaceae Leppik, Ann. Bot. Fenn. 9(3): 139. 1972.

Diagnosis: Similar to Uredinineae differing in that the majority of species form Group VI spermogonia whereas the majority of Uredinineae form Group V spermogonia.

Description: With the characteristics of the included families. Most species form Group VI spermogonia; many species form elaborate, multi-celled teliospores.

Included families: Ochropsoraceae, Phakopsoraceae, Raveneliaceae, Tranzscheliaceae.

Notes: The Raveneliineae is the most challenging suborder in which to resolve families due to: (i) a pattern of multiple, parallel radiations in this lineage (Fig. S2); (ii) multiple instances of convergent morphologies; (iii) polyphyly; and (iv) incomplete sampling and missing data in our analyses. Raveneliineae is the second richest suborder in terms of taxonomic diversity, with ca. 45 accepted genera, of which we were only able to sample representatives from about half and most of these with incomplete locus data.

Host range may be an informative character to place taxa of Raveneliineae in families. For example, Savile (1989) predicted Maravalia sensu Ono (1984) was polyphyletic, and hypothesised that species on Fabaceae belonged to Raveneliaceae, supported here with the placement of the Fabaceae-infecting M. limoniformis within Raveneliineae (Figs 1, 3) and the Apocynaceae-infecting U. cryptostegiae (syn. M. cryptostegiae) within Zaghouaniaceae (Fig. 1). Likewise, Triphragmium Link has evolved elaborate teliospores similar to those in some Raveneliaceae where it has been allied in the past (e.g., Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003); Triphragmium species are now known to belong to Phragmidiaceae with other Rosaceae-infecting rusts (Aime 2006).

We treat four families within Raveneliineae, taking into account life cycle and host data, and have taken a conservative approach to assigning genera within families and species to genera until data from type species and/or exemplars from key missing taxa as well as additional loci can be obtained.

Ochropsoraceae (Arthur) Aime & McTaggart, fam. & stat. nov. MycoBank MB836640.

Basionym: Ochropsoratae Arthur, Rés. Sci. Congr. Int. Bot. Vienne: 336. 1906.

Type genus: Ochropsora Dietel, Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 13: 401. 1895.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 7). Aecia aecidium-type; uredinia malupa-type; aecial states systemic overwintering as mycelium; telia forming crusts, 1-cell deep, at first subepidermal, then erumpent; teliospores germinate without dormancy, either internally (Ochropsora) or externally (Aplopsora). Species likely macrocyclic and heteroecious, although gametothallus not known for Aplopsora.

Included genera: Aplopsora, Ochropsora; likely includes Ceraceopsora.

Host families: Ranunculaceae (0-I); Rosaceae, Cornaceae (II-III)

Notes: A monophyletic Ochropsoraceae as the earliest diverging lineage of Raveneliineae was recovered in all of our analyses. Aplopsora and Ochropsora were previously treated within the artificial Chaconiaceae (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003) where they shared the convergent character of teliospore germination without dormancy.

Tranzscheliaceae (Arthur) Aime & McTaggart, fam. & stat. nov. MycoBank MB836641.

Basionym: Tranzschelieae Arthur, Rés. Sci. Congr. Int. Bot. Vienne: 340. 1906.

Type genus: Tranzschelia Arthur, Rés. Sci. Congr. Int. Vienne: 340. 1906.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 7). Aecia aecidium-type; uredinia uredo-type. Teliospores 2-celled, pedicellate, produced from sterile basal cells. Species are macrocyclic and heteroecious, with some derived microcyclic species.

Included genera: Leucotelium, Tranzschelia.

Host families: Ranunculaceae (0-I and autoecious species); Rosaceae (II-III in heteroecious species).

Notes: Tranzschelia has held an isolated position within Pucciniales in prior molecular studies (Aime 2006) and appears as an independent lineage of Raveneliineae in this work (Fig. 1). Leucotelium has been treated as a synonym of Sorataea (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003) but retained by Thirumalachar & Cummins (1940) due to the presence of a sterile basal cell layer from which the teliospores develop that is lacking in Sorataea. Two non-type species of Sorataea were included in our analyses and are referable to Raveneliaceae (Fig. 3). Leucotelium is the sister genus to Tranzschelia (Scholler et al. 2019), with which it shares a similar host range and teliospore production from sterile sporogenous cells (Thirumalachar & Cummins 1940, López-Franco & Hennen 1990). Many species of Tranzschelia are microcyclic on Ranunculaceae in accordance with Tranzschel’s Law (Scholler et al. 2019).

Phakopsoraceae Cummins & Y. Hirats., Illustr. Gen. Rust Fungi, rev. Edn (St. Paul): 13. 1983. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Type genus: Phakopsora Dietel, Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 13: 333. 1895.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 7). Aecia caeoma-type, some Masseeëlla with aecidium-type aecia; uredinia lecythea- or uredo-type. Teliospores 1-celled. Bubakia, Masseeëlla and Nothoravenelia species are autoecious and macrocyclic. The majority of Phakopsora and Uredopeltis species are only known from the sporothallus.

Included genera: Bubakia, Masseeëlla, Nothoravenelia, Phakopsora, Uredopeltis; likely includes Arthuria, Cerotelium, Dicheirinia, Monosporidium, Phragmidiella, Pucciniostele, Scalarispora.

Host families: Annonaceae, Bignoniaceae, Burseraceae, Commelinaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Myrtaceae, Rubiaceae, Urticaceae (0-III).

Notes: Both Phakopsora and the Phakopsoraceae are known to be polyphyletic (e.g., Aime 2006), with more than 100 species currently classified in Phakopsora s.l. However, lack of data and differing interpretations of the type have hampered taxonomic progress. The recent designation of a new type species for Phakopsora, P. pachyrhizi (Aime et al. 2019a, b), has stabilized use of the name as applied here, for those genera and species that share a common ancestor with P. pachyrhizi. Phakopsora remains poorly resolved with our data and consists of two supported clades, one containing P. pachyrhizi and its allies and the other containing most of the Annonaceae-infecting species, which may represent a separate genus, but were recovered as monophyletic in some analyses (not shown).

The name Bubakia is often treated as a synonym of Phakopsora (e.g., Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). Our study shows that Bubakia argentinensis belongs to a distinct lineage within Phakopsoraceae (Figs 1, 3). Further, B. argentinensis shares similar hosts (Croton spp.) and characteristics with the type, B. crotonis, and we accept Bubakia for these species (Mundkur 1943). Masseeëlla has previously been treated as incertae sedis within Pucciniales (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003), but our data place it within Phakopsoraceae (Figs 1, 3).

The majority of Phakopsora and Uredopeltis species are known only from sporothalli. It is unknown whether gametothalli occur on an alternate host, or whether these species are autoecious. Sporothalli have been described for a few Phakopsora species, i.e., P. breyniae, P. innata, P. phyllanthi-discoidei, and P. stratosa, which are all autoecious (Berndt & Wood 2012, Ono 2015b), although it is unclear whether these should be retained in Phakopsora s.s. or are allied with one of the segregate ex-Phakopsora genera.

Phakopsora pipturi (Syd.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836642.

Basionym: Pucciniastrum pipturi Syd., Annls mycol. 29(3/4):171. 1931.

Synonym: Uredo pipturi (Syd.) Hirats. f., Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan 5: 4. 1957.

Raveneliaceae Leppik, Ann. bot. fenn. 9: 139. 1972. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Synonyms: Chaconiaceae Cummins & Y. Hirats., Illustr. Gen. Rust Fungi, rev. Edn (St. Paul): 14. 1983.

Uropyxidaceae Cummins & Y. Hirats., Illustr. Gen. Rust Fungi, rev. Edn (St. Paul): 14. 1983.

Type genus: Ravenelia Berk., Gard. Chron. 13:132. 1853.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 5 or 7); aecia uredo- (rarely aecidium-, caeoma-, or lecythea-) type; uredinia uredo-type. Teliospores 1- to many-celled, some species with elaborate compound or multi-celled teliospores. Majority of species autoecious and macrocyclic, with a few derived microcyclic species; many species on mimosoid (Caesalpinioideae) hosts.

Included genera: Bibulocystis, Cephalotelium, Crossopsorella, Diorchidium, Endoraecium, Kernkampella, Lipocystis, Newinia, Olivea, Porotenus, Prospodium, Ravenelia, Sorataea, Uromycladium, Uropyxis, Ypsilospora; likely includes Allotelium, Anthomyces, Anthomycetella, Apra, Atelocauda, Chaconia, Cystomyces, Diabole, Diochordiella, Esalque, Hennenia, Maravalia, Mimema, Phragmopyxis, Spumula, Tegillum.

Host families: Bignoniaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Sapotaceae, Verbenaceae (0-III).

Notes: Leppik (1972) limited Melampsoraceae to rust species that are heteroecious and temperate, reassigning the autoecious and tropical species to a new family, Raveneliaceae. Savile (1989) provided an in-depth study of Raveneliaceae and hypothesised that the most recent common ancestor of Raveneliaceae was heteroecious, but that the family diversified as autoecious species on mimosoid (Caesalpinioideae) hosts after an environmental event severed their association with the initial sporothallus host. This hypothesis finds support in our work, which shows that the two early diverging families of Raveneliineae, Ochropsoraceae and Tranzscheliaceae (Fig. 1), are heteroecious with sporothalli hosts in Ranunculaceae.

Chaconia, which we place within Raveneliaceae, has been placed variously in the Melampsoraceae or with other rust genera in the artificial Chaconiaceae. This and prior works have shown Chaconiaceae, and most of the genera therein, as polyphyletic. The morphological character on which they were based, specifically thin-walled, pale teliospores that germinate without dormancy, was derived multiple times within Pucciniales (Aime, 2006, Aime et al. 2018a), as a result of convergent morphologies in species adapted to tropical climates that do not need to overwinter (Savile 1989).

Uropyxidaceae consists of an artificial assemblage of rust fungi combining (mostly) 2-celled, transversely septate teliospores and Group VI (type 5) spermogonia (where present). In this study, we sampled nearly all genera of Uropyxidaceae as circumscribed by Cummins & Hiratsuka (1983, 2003), most of which had not been previously sequenced; from our results the family is clearly polyphyletic. Many of the genera placed in Uropyxidaceae by Cummins & Hiratsuka (1983, 2003) were once considered allied within Pucciniaceae due to similarities in teliospore morphology. Our analysis shows that several of these, i.e., Desmella, Dipyxis, Edythea, Macruropyxis, belong to Pucciniaceae (Fig. 4). Dasyspora is allied in Sphaerophragmiaceae and Tranzschelia in Tranzscheliaceae (Fig. 1). The remaining genera – Newinia, Porotenus, Prospodium, Sorataea, and Uropyxis – are included within a broadly defined Raveneliaceae (Fig. 3).

Raveneliaceae is not resolved in our analyses, with strong support for some genera with multiple sampling, but almost no support for infra-familial nodes (Figs 1, 3, S2). Branch lengths for species of Raveneliaceae are comparatively long (Figs 3, S2) and may indicate an accelerated evolutionary rate in this family. 28S data alone can be informative for other Pucciniales lineages (e.g., Ji et al. 2019), but are inadequate for resolving relationships of genera, and in many cases even species, within Raveneliaceae (Fig. S2).

No sequence data are available for the generic type, R. glandulosa, a Western Hemisphere rust of Tephrosia. Ravenelia sp. (PUR F19717, Fig. 3) shares a host with R. glandulosa and may be congeneric with the type. Maravalia s.s. as represented by M. limoniformis (Figs 1, 3) is likely to belong here.

The genus Olivea, as circumscribed in the past, contains a polyphyletic assemblage of species that form a hymenial layer of probasidia that germinate via apical extension. Three species formerly placed in Olivea were included in our analyses: (i) O. capituliformis, the type for the genus; (ii) O. scitula; and (iii) O. tectonae, none of which are related to each other (Figs 3 & S2). Neoolivea tectonae (syn. O. tectonae) is placed in the Crossopsoraceae and discussed there. Olivea scitula was considered by Mains (1940) as most similar to Tegillum fimbriatum, and we apply the name T. scitulum to this species, although further work is necessitated to determine if it is, indeed, congeneric with the type species, T. fimbriatum. Olivea capituliformis is the only described species in this complex that infects hosts in Euphorbiaceae; the ex-Olivea species that we treat infect hosts in Verbenaceae (Ono & Hennen 1983).

Cephalotelium evansii (Syd. & P. Syd.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836643.

Basionym: Ravenelia evansii Syd. & P. Syd. Annls mycol. 10: 440. 1912.Synonym: Dendroecia evansii (Syd. & P. Syd.) Syd., Annls mycol. 19: 165. 1921.

Cephalotelium neocaledoniense (B. Huguenin) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB837616.

Basionym: Ravenelia neocaledoniensis B. Huguenin, Bull. trimest. Soc. mycol. Fr. 82: 263 (1966).

Cephalotelium xanthophloeae (M. Ebinghaus et al.) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836644.

Basionym: Ravenelia xanthophloeae M. Ebinghaus et al., MycoKeys 43: 11. 2018.

Notes: Of the ca. 200 species currently placed in Ravenelia, our data consistently resolved as congeneric those we now refer to Cephalotelium (Figs 3, S2). These species were also strongly supported as one of two monophyletic groups in Ravenelia s.l. by Ebinghaus et al. (2018b). Cephalotelium macowanianum (syn. Ravenelia macowanianum) is the type of Cephalotelium. The formation of telial galls is sometimes induced by infection of Ravenelia species, but not by Cephalotelium species. In contrast, C. evansii, C. macowanianum and C. xanthophloeae induce aecial gall formation in host tissues, which is a trait that appears to be confined to the Cephalotelium lineage (Ebinghaus et al. 2018a, b). Cephalotelium species infect members of Vachellia (Caesalpinioideae) in the Eastern Hemisphere (Sydow 1921). Cephalotelium is possibly a later synonym for Dendroecium, however, the type, D. farlowiana, occurs on Senegalia (Caesalpinioideae) species in the Western Hemisphere (Dietel 1894).

Lipocystis acaciae-pennatulae (Dietel) Aime & McTaggart, comb. nov. MycoBank MB836645.

Basionym: Ravenelia acaciae-pennatulae Dietel, Beih. bot. Zbl., Abt. 2 20: 373. 1906.

Notes: Lipocystis with the type species L. caesalpiniae was described as a monotypic genus for a rust on Mimosa from the West Indies. A second species, Lipocystis acaciae-pennatulae, infects Acacia species in Central America and is congeneric with L. caesalpiniae (Figs 1, 3, S2).

Uredinineae Engl., Syllabus der Vorlesungen über spezielle und medizinisch-pharmazeutische Botanik: 36. 1892. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Synonym: Pucciniineae Doweld, Index Fungorum 77: 1. 2014.

Type family: Pucciniaceae Chevall.

Description: With the characteristics of the included families. Most species form Group V but also Group VI spermogonia and 1- or 2-celled teliospores but multi-celled telia formed in some or most Nyssopsora, Phragmidiaceae, and Sphaerophragmiaceae.

Included families: Crossopsoraceae, Gymnosporangiaceae, Phragmidiaceae, Pileolariaceae, Pucciniaceae, Sphaero-phragmiaceae.

Notes: Uredinineae is the largest suborder in both species numbers and generic diversity. Pucciniineae is a superfluous name for the older Uredinineae. We were able to sample types or type representatives for 50 of the ca. 70 genera placed here as well as several species currently assigned to form-genera.

We were unable to resolve the placement for three genera: Allodus, Neopuccinia, and Nyssopsora. Allodus was long considered a synonym of Puccinia due to its pedicellate, 2-celled teliospores. Minnis et al. (2012) resurrected Allodus as an orphan genus of uncertain placement. Our analyses occasionally resolved Allodus as sister to Peridiopsora mori with weak support (not shown). Only a single 28S sequence is available for the newly described Neopuccinia, which shares many similarities with Kimuromyces (Dianese et al. 1995). Connections between Nyssopsora and Sphaerophragmium have been noted by Lohsomboon et al. (1994). Nyssopsora was recovered as sister to Sphaerophragmiaceae in some but not all of our analyses (Figs 1, 4) and may represent a separate family lineage.

Phragmidiaceae Corda Icon. fung. (Prague) 1: 6. 1837.

Type genus: Phragmidium Link, Mag. Ges. Naturfr. Freunde Berlin 7: 30. 1816.

Description: Spermogonia of Group IV (various types); aecia variable, caeoma-, petersonia- or uredo-type; uredinia lecythea- or uredo-type. Teliospores mostly multi-celled, usually by transverse septa. Species autoecious on Rosoideae subfamily of Rosaceae.

Included genera: Gerwasia, Gymnoconia, Hamaspora, Kuehneola, Phragmidium, Trachyspora, Triphragmium, Xenodochus; likely includes Joerstadia.

Host family: Rosaceae (0-III).

Notes: Convergence in teliospore morphology between some genera of Phragmidiaceae and Raveneliaceae has been previously noted (e.g., Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003); Aime (2006) showed that Phragmidiaceae species are confined almost exclusively to the Rosoideae in contrast to Raveneliaceae.

Pileolariaceae (Arthur) Cummins & Y. Hirats., llustr. Gen. Rust Fungi, rev. Edn (St. Paul): 14. 1983. emend. Aime & McTaggart

Type genus: Pileolaria Castagne, Obs. Plantes Acotylédonées Fam. Urédinées 1: 22. 1842.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 7). Aecia and uredinia uredo-type. Teliospores 1-celled with characteristic sculpted appearance; germination external after dormancy. Species mostly macrocyclic and autoecious.

Included genus: Pileolaria.

Host family: Anacardiaceae (0-III).

Notes: Pileolariaceae was established for autoecious rusts in Pileolaria, Uromycladium and Endoraecium (Arthur 1906, Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). The latter two have been resolved within Raveneliaceae, while Pileolaria holds an isolated position within Pucciniales (Aime 2006, Scholler & Aime 2006, Figs 1, 4). Pileolaria species are autoecious on Anacardiaceae, with very characteristic sculpted discoid teliospores.

Crossopsoraceae Aime & McTaggart, fam. nov. MycoBank MB836646.

Type genus: Crossopsora Syd. & P. Syd., Annls mycol. 16(3/6): 243. 1919.

Diagnosis: Similar to Phakopsoraceae, differing in that the majority of sporothalli infect Poaceae, Vitaceae, Lamiaceae, and Rhamnaceae with none known on Annonaceae and Euphorbiaceae and that some species are known to be heteroecious.

Description: Spermogonia Group VI (type 7) where known; aecia aecidium-type where known; uredinia typically paraphysate, malupa-type; teliospores germinate externally, with or without dormancy, 1-celled, compact, often produced in catenulate chains of a few to many cells. Most species only known from the sporothallus; Neophysopella is macrocyclic and heteroecious, as may be other species in this family.

Included genera: Angiopsora, Catenulopsora, Crossopsora, Kweilingia (= Dasturella), Neoolivea, Neophysopella, Stomatisora.

Host families: Papaveraceae, Sabiaceae, Rubiaceae (0-I); Lamiaceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rubiaceae, Salicaceae, Vitaceae (II-III).