Abstract

Background:

Substance use-related stigma is a significant barrier to care among persons who use drugs (PWUD). Less is known regarding how intersectional identities, like gender, shape experiences of substance use-related stigma. We sought to answer the following question: Do men or women PWUD experience more substance use stigma?

Methods:

Data were drawn from a systematic review of the global, peer-reviewed scientific literature on substance use-related stigma conducted through 2017 and guided by the Stigma and Substance Use Process Model and PRISMA guidelines. Articles were included in the present analysis if they either qualitatively illustrated themes related to the gendered nature of drug use-related stigma, or quantitatively tested the moderating effect of gender on drug use-related stigma.

Results:

Of the 75 studies included, 40 (53%) were quantitative and 35 (47%) were qualitative. Of the quantitative articles, 22 (55%) found no association between gender and drug use-related stigma, 4 (10%) identified women who use drugs (WWUD) were more stigmatized, and 2 (5%) determined men who use drugs (MWUD) were more stigmatized. In contrast, nearly all (34; 97%) of the qualitative articles demonstrated WWUD experienced greater levels of drug use-related stigma.

Conclusion:

The quantitative literature is equivocal regarding the influence of gender on drug use-related stigma, but the qualitative literature more clearly demonstrates WWUD experience greater levels of stigma. The use of validated drug use-related stigma measures and the tailoring of stigma scales to WWUD are needed to understand the role of stigma in heightening the disproportionate harms experienced by WWUD.

Keywords: Gender, Drug Use, Stigma, Intersectionality, Systematic Review, Mixed Methods

1. Background

The stigmatization and criminalization of psychoactive drug use is common across most modern societies (Kulesza, Larimer, & Rao, 2013; Room, 2009). Among persons who use drugs (PWUD), substance use stigma is associated with poor psychological well-being and is a significant barrier to accessing health care, drug screening, and drug treatment services (Kulesza et al., 2013; Room, 2009). Health care utilization is further impeded when health professionals ascribe stereotypes of poor motivation, violence, and manipulation to patients with substance use disorders (SUDs) (van Boekel et al., 2014), despite SUDs being a clinically diagnosed and treatable condition.

Existing evidence suggests gender may influence the perspectives of non-substance using individuals towards drug use (Mclaughlin & Long, 1996; Mundon et al., 2016). For example, women who do not use drugs may hold more negative views, and be less tolerant of, drug misuse compared to men (Kauffman et al., 1997; Mundon et al., 2016). Within this research, it has been hypothesized that women hold more stigmatizing views of drug use because they either have had less contact with PWUD and/or they believe substance use to be more severe (Brown, 2015; Kauffman et al., 1997). Additionally, limited research indicates that women who use drugs (WWUD) encounter intersectional stigma, including within existing drug using networks and drug policy environments, due to gendered social norms and societal expectations that women be primary caregivers (El-Bassel et al., 2012; Iverson et al., 2015). Intersectional stigma places WWUD at greater risk of injection-related harms like HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) (Iverson et al., 2015). Additionally, WWUD experience high rates of violence from intimate partners, strangers, and acquaintances which has been linked to harm reduction service avoidance, HIV-, and HCV-related risk behaviors for this population (Iverson et al., 2015).

Additional gender-responsive research and tailored intervention efforts are needed to better understand the intersectional nature of the gender- and substance use-related stigma experiences of WWUD, and to mitigate stigma-related substance use harms. While a small body of research has highlighted the multiplicative effect of gender and substance use-related stigmas on the risk of HIV and other blood borne pathogens (El-Bassel et al., 2012; Iverson et al., 2015), little is known regarding their combined impact on a range of health and social outcomes (e.g. drug misuse). To that end, intersectionality researchers have argued that examining stigmatized identities (e.g., drug use or gender) in isolation or in an additive manner can serve to obfuscate complex experiences of multiple stigmas and their impacts on health disparities (Bowleg, 2008).

The aim of the current study is to systematically review the scientific literature on the intersection of gender- and substance use-related stigma, from both the perspective of PWUD and the perspective of persons that do not use drugs, and to assess how this intersection impacts trajectories into drug misuse (i.e., frequency of use, types of drugs used, drug misuse, and related drug risk behaviors [e.g., injection drug use]).

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

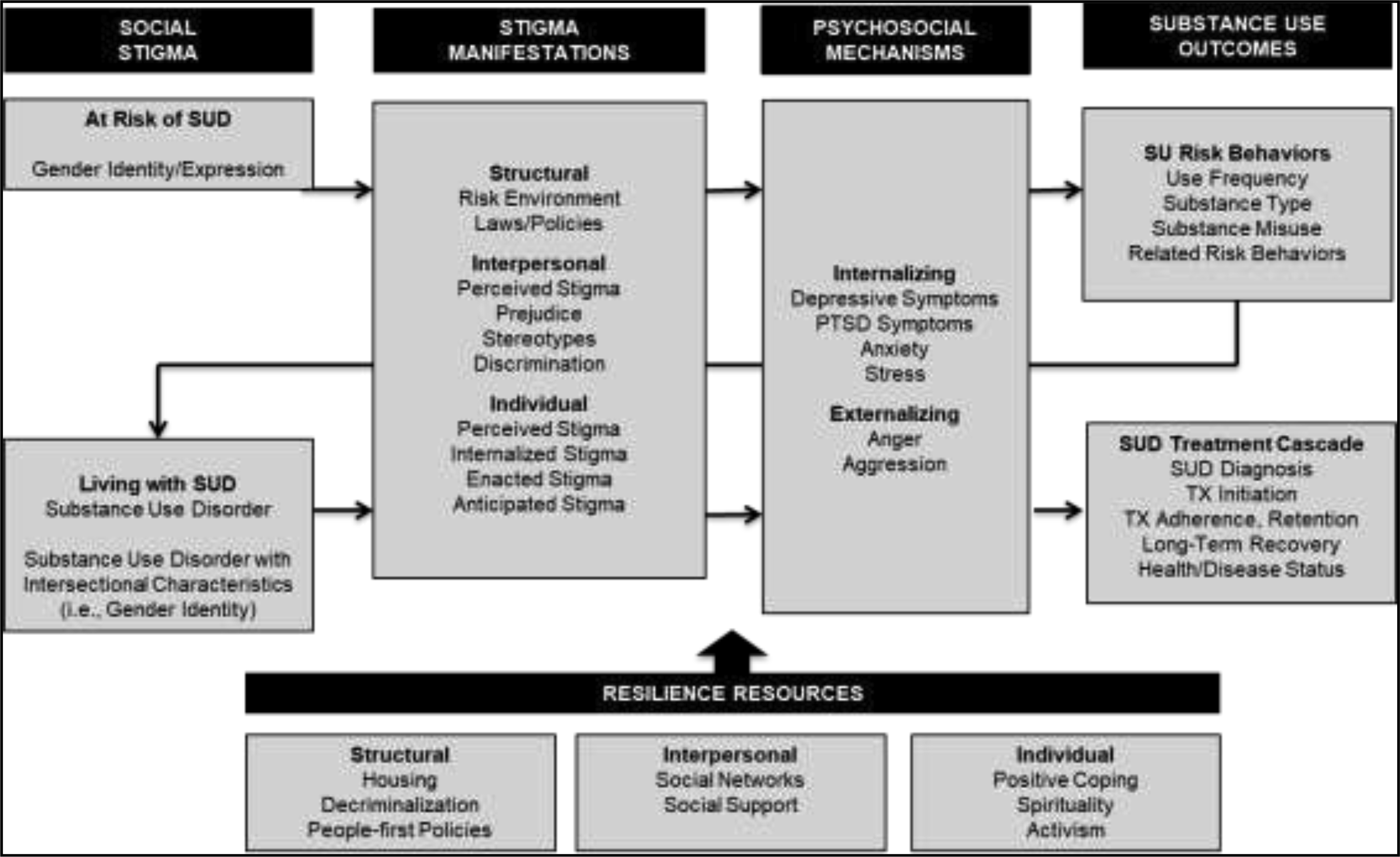

The Stigma and Substance Use Process Model was adapted for the purposes of the present study (See Figure 1) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). This model describes: (1) how social stigma is associated with behaviors that place individuals at risk for developing SUDs (top half of Figure 1), and (2) how substance use-related stigma, and the intersection of other stigmatized characteristics, serve to undermine substance use-related treatment and health outcomes (bottom half of Figure 1) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017).

Figure 1. The Stigma and Substance Use Process Model adapted to focus on intersectional gender- and substance use-related stigma processes.

• SUD Substance Use Disorder; PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; SU: Substance Use; TX: Treatment.

This model also delineates that social stigma is experienced at three levels: structural, interpersonal, and individual. Structural stigma consists of the macrosocial ways in which individuals are disadvantaged outside of individual-level interactions (i.e., social structures, policies, laws, and institutions) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Hatzenbuehler & Link, 2014; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). Interpersonal manifestations of stigma consist of the ways in which social stigma is perpetrated and experienced by those who are not members of the stigmatized group (e.g., perceived stigma, prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). Individual manifestations of stigma consist of experiences of social stigma among individuals within a socially devalued group or with socially devalued characteristics (e.g., perceived, internalized, anticipated, and enacted stigma) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). The process model further hypothesizes that these stigma manifestations (i.e., structural, interpersonal, and individual) impact substance use-related behaviors (e.g., substance misuse and substance risk behaviors [e.g., injection drug use]) via a series of psychosocial mechanisms (i.e., internalizing and externalizing symptoms), that can be mitigated via a series of resilience resources (i.e., decriminalization, social support, spirituality) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). Among PWUD, the three levels of stigma manifestations coupled with an individual’s psychological well-being serve to impact substance use treatment outcomes (i.e., SUD diagnosis, treatment initiation, treatment adherence, long-term recovery, and health/disease status) (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). The Stigma and Substance Use Process Model informed both a parent systematic review from which the current review is derived and guided the development of the coding framework, and thematic analysis for the current review.

2.2. Search Strategy

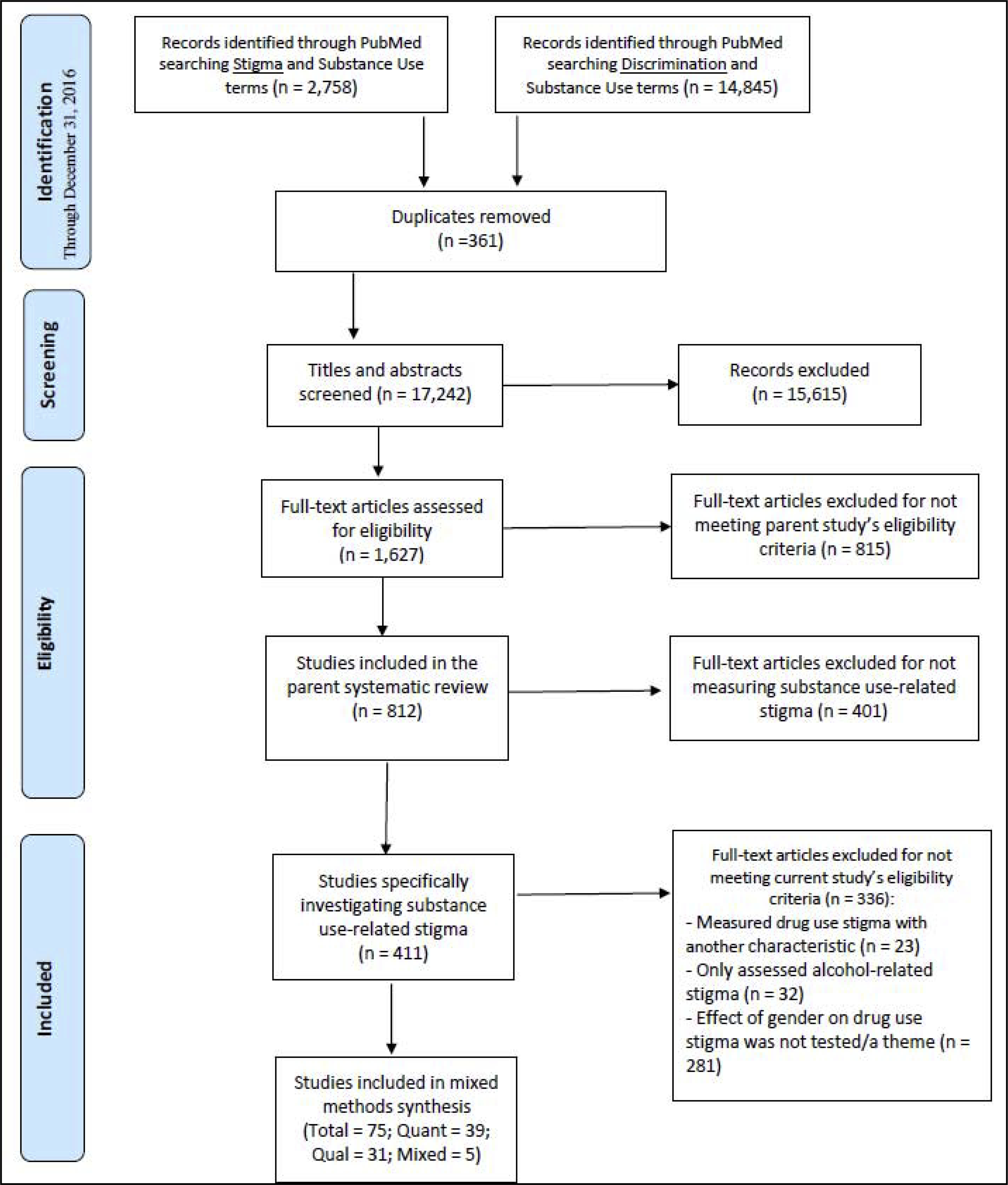

The current study was drawn from a larger parent systematic review of the global scientific literature on substance use stigma conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). The current study extends the scope of the parent systematic review to investigate the impact of intersectional gender- and drug use identities on the relationship between experiences of drug use-related stigma and drug use-related outcomes, defined as frequency of use, drug misuse, and risky drug-related behaviors. Search terms were developed and piloted to capture published articles that examined (1) stigma and (2) substance use-related terms (e.g., addiction, alcoholism, alcohol use, substance use, drug use) in PubMed. The initial search was conducted on April 8th, 2016, yielded 2,435 unique titles, and was updated on May 24th, 2017 censoring the publication date at December 31st, 2016, yielding an additional 323 unique titles. To ensure we captured all manuscripts that examined stigma and/or discrimination, the search was then amended to replace the term ‘stigma’ with ‘discrimination’ and rerun on May 24th, 2017, obtaining 14,845 unique titles after removing 361 titles duplicated from the previous searches. Combined, the titles and abstracts of 17,242 unique articles were screened for inclusion in the parent systematic review.

2.3. Full-Text Review

All articles were reviewed by two independent trained coders at each stage of the review and coding process. Coding decisions were reviewed at weekly team meetings held by the senior author (LRS) and any discrepancies in codes were resolved by group consensus. First, the titles and abstracts of 17,242 unique articles were screened to identify articles that potentially assessed stigma/discrimination and any substance use related experience (e.g., substance use/misuse/dependence, SUD diagnosis/disclosure/treatment), and that would warrant a full-text review for the parent systematic review. A total of 15,615 articles were excluded that lacked both stigma/discrimination and substance use-related topics in the title or abstract. Next, inclusion was determined via a full-text review of the remaining 1,627 articles. Articles were excluded from the parent study if: (1) the article was not an original, peer-reviewed, research article, (2) the article did not quantitatively measure stigma or identify stigma as a qualitative theme, (3) the authors measured a stigmatized characteristic other than substance use stigma and did not also measure substance use-related outcomes, and (4) the article was not in English. No exclusion criteria regarding the publication year, populations sampled, study methods employed, or the geographic region studied were applied in the parent systematic review. Following the full text review, 815 articles were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria and 812 articles meeting the parent study’s criteria were retained for coding.

For the current study, trained coders (SAM, BD) reviewed the 812 parent study articles for the following inclusion criteria: (1) stigma related to drug use was assessed (i.e., measured stigma for drugs other than alcohol or tobacco), (2) drug use-related stigma was assessed independent of other stigmatized characteristics (e.g., mental health diagnoses) allowing for the true effect of gender on drug use-related stigma to be determined, and either (3) contained qualitative themes related to the gendered nature of drug use-related stigma, or (4) quantitatively tested the moderating effect of gender on drug use-related stigma.

2.4. Coding Process

A standardized codebook was developed iteratively by the senior author (LRS) to capture information related to the Stigma and Substance Use Process Model (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). Trained coders then documented whether or not each of the 812 articles assessed the following quantitative or qualitative information: (1) level of stigma manifestation (structural, interpersonal, individual), and (2) drug use outcome (i.e., frequency of use, drug type, drug misuse, or other risk behaviors) and/or (3) drug use treatment (e.g., treatment initiation and adherence). The trained coders also assessed the studies’ methods: study duration (cross-sectional or longitudinal), data type (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods), whether the study was an intervention or was observational, study characteristics, and participant characteristics. For the current review, the specific stigma scale employed in the quantitative studies was also coded.

2.5. Analysis of Data

Aligned with standard review methodology (Kulesza et al., 2013; Leibovici & Falagas, 2009; Uman, 2011; Werb et al., 2013), this review evaluated the following quantitative criteria: (1) study characteristics: sample size, study location, study method, and year published, (2) participant characteristics: gender (i.e., men, women, or transgender), age, and race/ethnicity, (3) stigma-related variables: how stigma was defined and stigma type (i.e., substance use stigma and/or gender-related stigma), and (4) substance use-related variables (i.e., frequency of use, substance type used, substance misuse, and substance related risk behavior). The primary outcomes of interest were the stigma-related variables, and the secondary outcomes were the substance use variables. Data were extracted from each article and organized in tables for analysis.

Our thematic synthesis of the qualitative data used methods developed by Thomas and Harden (2008) and was guided by the Stigma and Substance Use Process Model (Earnshaw & Smith, 2017; Smith & Earnshaw, 2017). Thematic synthesis is a method in which descriptive and analytical themes are developed through the coding of original studies (Guise, Horniak, Melo, McNeil, Werb, 2017; Thomas & Harden, 2008), where the focus of the coding and analysis is on the constructs identified by study authors (i.e., second order constructs). This is done to avoid introducing bias through the reinterpretation of primary data given our limited understanding of the context in which the original data were collected, and the potential for misinterpreting isolated fragments of data (Guise, Horniak, Melo, McNeil, Werb, 2017; Thomas & Harden, 2008). The descriptive themes generated from this synthesis examines the findings from the original studies in an effort to identify common and overlapping areas of focus and to provide a novel synthesis of the literature (Guise, Horniak, Melo, McNeil, Werb, 2017; Thomas & Harden, 2008). The aim of this analysis, then, was to identify themes that describe and explain the intersection of gender and substance use stigma.

After reviewing the included qualitative articles, a coding framework to guide the thematic synthesis was iteratively developed and refined by two authors (SM, LRS). The coding framework and coding process allowed for the “reciprocal translation” of the findings (Guise, Horniak, Melo, McNeil, Werb, 2017; Thomas & Harden, 2008), in which the findings and concepts from different studies were able to be combined. Additionally, the study team worked together to discuss the coding and analysis process, the translation of concepts from different studies, the comparison of codes within code categories, and the grouping of codes into categories. Code categories were reviewed, discussed, and revised until consensus was reached among the study team.

Lastly, the quality of the study methods for all articles that met inclusion criteria were evaluated to aid in the interpretation of the analysis (Guise, Horniak, Melo, McNeil, Werb, 2017; Werb et al., 2016). Quantitative methods quality was evaluated with the Downs and Black checklist, which is composed of 27 items for intervention studies (Range: 0–27) and 18 items for observational studies (Range: 0–18) and assesses five domains of study quality: reporting, external validity, risk of bias, confounding, and statistical power (Downs & Black, 1998; Werb et al., 2016). Qualitative methods quality was assessed with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist, which is comprised of 10 items (Range: 0–10) that assess three domains of study quality: study validity, results, and local impact (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). For both checklists higher scores represent higher study quality. Members of the study team (SM, NC) independently rated the study quality of all included articles and any discrepancies were discussed (SM, NC, LRS) until consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristic.

Of the 812 articles that fulfilled the parent study’s inclusion criteria, 411 specifically measured substance use-related stigma and were evaluated for the current study. Of these 411 articles 336 were excluded from this analysis: 32 only assessed alcohol-related stigma, 23 assessed drug use-related stigma in conjunction with another stigmatized characteristic in such a way that the unique effect of gender on drug use-related stigma was unable to be determined, gender did not emerge as a theme within discussions of drug use-related stigma for 174 qualitative studies, and 107 quantitative articles did not test the moderating effect of gender on drug use-related stigma. Seventy-five articles met all inclusion criteria for the current study and were retained for analysis (See Figure 2). Of these 75 articles, 39 (52%) were quantitative studies, 31 (41%) were qualitative, and 5 (7%) were mixed methods. Mixed methods studies were analyzed as quantitative (n = 1) or qualitative (n = 4) based on the portion of that study’s analyses that pertained to this review.

Figure 2. A flow chart of the systematic review process for the current study investigating the intersection of gender- and drug use-related stigma according to PRISMA guidelines.

3.1.1. Methodological Quality Assessment

Of the 39 included quantitative articles and one mixed methods article, 3 studies were interventions, and the remaining 37 studies were observational. The mean checklist score for the intervention studies was 13 and ranged from 10 to 18 (Max: 27; IQR: 10.5–12), whereas the mean for the observational studies was 11 and ranged from 7 to 15 (Max: 18; IQR: 10–13). Twenty-nine (74%) did not report pertinent information on study methods, characteristics, or results, and none adequately addressed issues of external validity, risk of bias, confounding, or power. Specifically, 34 (87%) did not sufficiently address external validity, 17 (44%) did not adequately adjust for confounding, and one study (3%) did not have adequate power.

Of the 31 included qualitative and four mixed methods articles, the mean checklist score was 8.1 and ranged from 6 to 9 (Max: 10; IQR: 8–9). Thirty-three (94%) of the articles failed to adequately address issues of validity and five (14%) did not provide details on necessary ethical considerations. All 35 articles, however, adeptly discussed the value of the presented research.

3.2. Quantitative Synthesis

Of the 40 articles that are included in this review of the quantitative literature, 27 (68%) assessed stigma from the perspective of non-substance using individuals (i.e., the interpersonal perspective), and 13 (32%) were from the perspective of PWUD (i.e., the individual perspective).

3.2.1. Quantitative Synthesis of Interpersonal Stigma

The majority of the interpersonal perspective articles (15; 55%) were from North America, with fewer from Europe (4; 15%), Australia (3; 11%), Asia (3; 11%), and Africa (1; 4%). One article (4%) did not specify the study location. Nearly all of the interpersonal perspective articles reported participant gender (26; 96%), though only 1 of these 27 articles (4%) moved past a binary measurement of gender to include persons who are transgender. See Table 1 for the full analysis of the quantitative articles assessing stigma from the interpersonal perspective.

Table 1.

A systematic review of quantitative studies investigating the intersection of gender and drug use stigma from the interpersonal perspective (n = 27).

| Actor Manifestations of Stigma | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Author (Year) | Study characteristics | Participant characteristics | Stigma-related variables | Summary of results | Quality Score | |||||

| n | Population | Location | Design | Age | Gender | Race | |||||

| 1 | Fonti (2016) | 147 | Maternity health care workers (71% midwives) | Australia | Cross-sectional survey design. | 51% were older than 40. | NR | NR | Adapted measure of attitudes of health care professionals towards women who use substances during pregnancy. | The majority of participants held positive or neutral views towards women who use s ubstances in pregnancy. Midwives had the lowest attitudinal scores (i.e., most positive views) when compared to other health care professionals. | 10 |

| 2 | Mundon (2015) | 155 | Clinical psychology doctoral students | San Franciscob Bay Area (US) | Factorial survey-vignette design. | 50% 20–29 years, 37.2% 30–39, 9% 40–49, 3.8% 50–59 | 72.3% women, 24.% men, 1.9% transgender, 1.3% other | 66.2% Caucasian/White, 14.9% Asian, 6.1% Hispanic/Latino, 4.7% Black/African American, 5.2% Other, 3.4% Mixed | Ratings of Emotional Attitudes of Clients by Treaters (REACT). *Onfy negative items. Perceived Causes of Vignette Conditions (PCVC). | Across diagnoses (MDD, cocaine dependence, and alcohol dependence) women had higher REACT scores (i.e. more negative emotional attitudes) when compared to men and transgender participants. | 13 |

| 3 | Brown (2015) | 250 | College students | Midwestern, US | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 18.8 years, Range: 18–25 | 52% women | 90% Caucasian | The Social Distance Scale for Substance Users (SDS)

The Affect Scale of Substance Users (AS) Adapted Forcing Treatment Scale (FTS) |

Women reported significantly higher levels of stigma

than men on the AS for marijuana and heroin. No gender difference in SDS scores. |

12 |

| 4 | Challapallisri (2015) | 226 | Doctors | Hyderabad, India | Prospective survey design. | NR | 50% men, 50% women | NR | A questionnaire that measured perceptions about people with 7 psychiatric disorders. (Hayward & Bright) | No significant gender differences in stigma towards drug addiction. | 7 |

| 5 | Kulesza (2015) | 899 | Adults | Project Implicit Website (US) | Web-based, cross-sectional, survey design. | Mean: 38.97 years, Range: 19–90 | 62.4% women, 37.6% men. | 69.9% Caucasian, 13.2% Black/African American, 7.3% mixed race, | Adapted Social Distance Scale to reference PWID.

2 items measuring support for NSPs and SIFs. 1 item assessing inclination toward helping/punishing PWID. |

Male gender was associated with higher support for NSPs and SIFs. | 14 |

| 6 | Flórez (2015) | 1,235 | Latinx and African American church-based participants | Long Beach, CA (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | 45.6% 31–50, 29.2% 18–30, 25.2% 51+ | 63.2% women, 36.8% men. | 34.4% Black/African American, 65.7% Latinx | A modified Ronzani’s alcoholism stigma scale consisting of 5 items exploring stereotypes of people who use drugs. | Men had higher drug use stigma scores, as did older adults and those with less education. | 13 |

| 7 | Meurk (2014) | 1,263 | Queensland residents | Queensland, Australia | Cross sectional computer assisted telephone interview. | 30.6% 65+, 22.6% 5564, 18.6% 45–54, 16.5% 35–44, 7% 25–34, 4.3% 18–24 | 50.3% women, 49.7% men. | NR | Participants presented with 2 scenarios: John

(addicted to alcohol) and Peter (addicted to heroin) Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire (AMIQ) |

Women were 0.73 times less likely to agree with coerced heroin addiction treatment. | 13 |

| 8 | van Boekel (2015) | 723 | Stakeholders (general public, general practitioners, mental health/addiction specialists, and clients) | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional online survey. | Public: 9.06 (mean), GP’s: 47.6 (mean), Specialists: 43.52 (mean), Clients: 40.92 (mean) | 47.3% women, 52.4% men | NR | 1. Stereotypical beliefs about people with SUDs (7

items) 2. Attribution beliefs about people with SUDs (5 items) 3. Perceptions of the chances for SUDs to lead a normal life (3 items) 4. Social distance (9 items) |

There is no association between gender and desired social distance for people with SUDs. | 14 |

| 9 | Luo (2013) | 848 | Residents | Hunan Province, China | Cross sectional survey design. | Mean: 38 Range: 16–65 | 45.9% women, 54.1% men | NR | Vignettes: heroin, ketamine, meth, and “normal”. Stereotyping & Social Distance Scales (Link) | No association between gender and views of drug dependence. | 12 |

| 10 | Crisp (2000) | 1,737 | Adults | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional survey design. | 11% 16–24, 68.1% 25–64, 20.8% 65+ | 55% women, 45% men | 95% White | Scale developed from work of Hayward & Bright (1997) | There were “only minor differences” in opinions of people with drug dependence. | 11 |

| 11 | Palamar (2013) | 531 | Adults | United States | Cross-sectional internet-based survey. | Mean: 29.14 Range: 18–64 | 70.6% women, 29.4% men | 32.2% Nonwhite, 67.8% White | Drug Use Stigmatization Scale | Females were less likely to report that addiction is a choice. Females and those that reported high levels of stigmatization were more likely to report that cocaine use is always unsafe. | 12 |

| 12 | van Boekel (2014) | 347 | Healthcare professionals: General practitioners, general psychiatry services, & addiction specialists. | Netherlands | Cross-sectional survey design. | GP Mean: 47.6, Psychiatry Mean: 44.8, Addiction Mean: 42.0. |

54.5% women, 45.5% men. | NR | Medical Condition Regard Scale (MCRS) and Comparable questions from the Attribution Questionnaire | Genderof healthcare professional does not predict MCRS score. | 15 |

| 13 | Palamar (2012) | 1021 | Young adults | New York (US) | Cross-sectional street-and internet-based survey design. | Mean: 20.32 Range: 18–25 | 53.5% women, 46.5% men. | 43.7% White, 13.4% Black, 16.7% Hispanic/Latinx, 18.1% Asian American, 8.1% Other. | Drug Use Stigmatization Scale for each of the following substances (Marijuana, Powder Cocaine, Ecstasy, Opioids, & Amphetamines) | Gender was not associated with the stigmatization of any of the drugs investigated. | 13 |

| 14 | Sorsdahl (2012) | 868 | Members of the general public. | South Africa | Cross-sectional street-based survey method with vignettes. | Mean: 27 | 51% women, 49% men. | 56% Black, 13% White/Asian, 30% Coloured. | 8 vignettes portraying alcohol, cannabis, meth, and

heroin. Attribution Questionnaire-Short Form (AQ-9) |

Respondents were more likely to feel coercion into

treatment was more acceptable for males who use substances. Respondents also reported avoiding female cannabis users more than male cannabis users and that coercion into treatment was acceptable for female methamphetamine users compared to their male counterparts. Participant gender was associated with the attribution stereotype of “anger” to vignette characters. |

13 |

| 15 | Li (2013) | 211 | MMT clients and providers | Sichuan, China | A longitudinal randomized MMT CARE intervention. | Standard: 40.5% ≤ 35, 36% 36–40, 23.6%

41+ Treatment: 25.6% ≤ 35, 47.8% 36–40, 26.7% 41+ |

Standard: 66.3% men, 33.7% women. Treatment: 64.4% men, 35.6% women |

NR | A scale assessing provider’s perceived stigma associated with working in a drug-related locale (9 items). | Service provider gender was not associated with perceived stigma. | 18 |

| 16 | Korszun (2012) | 760 | Medical students | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional, national online survey. | Mean: 23.8 Range: 17–31 | 67% women, 33% men. | 64.9% White, 19.1% South Asian, 5.9% Chinese, 2% Black, 1.6% Other | Medical Condition Regard Scale (MCRS) | Female medical students had significantly higher regard for IV drug users than male students. | 12 |

| 17 | Nabors (2012) | 425 | College students | Location not specified (author is based in Ohio, US) | Mixed methods, cross-sectional vignette study. | Range: 18–60 53% between 18 and 20, 41% 21 and 30. |

58.4% women, 41.6% men. | 83% Caucasian, 9% African American, 1% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 6% Other. | Five vignettes depicting an adolescent who misuses

alcohol, uses marijuana, or occasionally drinks and whether they’ve

received treatment. Items assessing participants’ liking of, desire to help, and beliefs about the adolescent’s academic progress. |

Female participants reported stronger desire to help

across vignette types when compared to males. Males, however, reported higher levels ofliking and beliefs about academic progress when compared to females. |

8 |

| 18 | Brown (2011) | 565 | College Students | Midwestern University (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | Range: 18–25 Mean: 18.6 | 68.5% women, 31.5% men. | 96.1% Caucasian | *Three mental illness stigma measures were modified to target substance users: Social Distance Scale (SDS) Dangerousness Scale (DS) Affect Scale (AS) | Women had higher scores on the SDS and AS when compared to men (indicating women held more stigmatizing views), but no significant gender difference was found for the DS measure. | 10 |

| 19 | Adlaf (2009) | 4,078 | 7th-12th graders | Ontario, Canada | Cross sectional survey design. | Mean: 14.9 | 48.7% women, 51.3% men. | NR | Four drug addiction social distance items adapted from the World Psychiatric Association’s Schizophrenia Open the Door project. | There is no relationship between gender and drug addiction stigma. | 13 |

| 20 | Corrigan (2007) | 968 | Adults | United States | Cross-sectional internet-based survey and vignette design. | Mean: 47.0 | 51.9% women, 48.1% men. | 72.5% White, 11.7% Black, 11% Hispanic, 4.8% Other. | Attribution Questionnaire (Primary Stigma) Seven items assessing family s tigma/courtesy s tigma. | Women were more likely to endorse dangerousness for schizophrenia and substance dependence (though this was not significant). Across conditions: Women were less likely to endorse stigma, more likely to expresspity and help and less likely to avoid and blame. | 11 |

| 21 | Kulesza (2016) | 899 | Volunteers at Project impliCi. | United States-based website | Implicit association test and internet-based survey design. | Mean: 39.0 | 62.4% women, 37.6% men. | 69.9% White, 13.2% African American, 7.3% Hispanic/Latinx, 7.3% more than one ethnicity, 4.2%, 3.1% Other, 1.4% Native American/Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | The Brief Implicit Association Test (Addiction Stigma) Explicit stigma vignette & six items about PWID punishment/help. | There was no significant effect of gender on implicit or explicit addiction stigma. | 13 |

| 22 | Kennedy- Hendricks (2016) | 1,620 | Adults | United States | Internet-based experiment and vignette design. Participants were randomly assigned to vignette naratives. | 12.2% 18–24, 18.4% 25–34, 15.9% 35–44, 16.5% 45–54, 19.7% 55–64, 17.4% 65+ | 51.6% women, 48.4% men. | 73.4% Whťe only, 11.4% Black only, 23.1 % Other. u.2% Hispanic and 84.8% NonHispanic | Beliefs about people with addiction to opioid pain relievers, perceptions of the effectiveness of treatment, attitudes about policy. Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) | Support for punitive policy (i.e. reporting requirements for pregnant women) was higher among women in the control group at baseline. | 14 |

| 23 | Morton (1976) | 83 | People who attended a symposium on employing ex-addicts. | White Plains, NY | Cross sectional survey design. | 24.% Under 30, 75.9% Over 30. | 42.2% women, 57.8% men. | NR | Attitudes regarding employing ex-addicts. | Gender was not related to attitudes towards employing ex-addicts. | 10 |

| 24 | Diaz (2008) | 421 | Health professionals | Puerto Rico (US) | Exploratory mixed methods design, QUAL → quan. | NR | 76% women, 24% men. | NR | Translated and adapted version of the Old Fashioned and Modern Sexism Scale (9 items). Translated and adapted Substance Abuse Attitude Survey (12 items). | Sexism scores were positively correlated with substance uses tigma scores among health care professionals (Though the highest correlation was between homophobia and AIDS-related stigma). | 8 |

| 25 | Brener (2016) | 90 | Alcohol or other drugs (AOD) workers | New South Wales, Australia | Cross-sectional vignette and survey design. | Mean: 41 | 52.2% women, 47.8% men. | NR | Brener and von Hippel’s scale of Attitudes towards PWID (10 items). | Male gender is positively associated with negative attitudes towards PWID | 9 |

| 26 | Nielson (2010) | 864 | Adults | United States | Cross sectional survey design. | Mean: 46.0 | 57% women, 43% men. | 100% White | Attitudes towards drug rehabilitation spending. | Male gender was negatively associated with attitudes toward drug rehabilitation spending. | 13 |

| 27 | Dunn (2009) | 155 | Residents of University of New Mexico Schoolof Medicine | New Mexico (US) | Cross-sectional survey and vignette design. | Mean: 31.8 | 44.7% women, 55.3% men. | 69% White, 16% Hispanic, 16% Other. | Items assessing perceived stigma, concern about training status jeopardy, and likelihood of avoiding care at the training institution for a variety of health conditions (including alcohol and other drug problems) | There were no gender differences in concern for potential jeopardy to training s tatus for drug problems. | 12 |

NR = Not Reported.

Of the interpersonal perspective articles, 12 (45%) found no significant relationship between gender and drug use-related stigma [article numbers: 4,8,9,10,12,13,15,19,21,23,27; See Tables 1–4 for corresponding article information; article numbers will be referenced in brackets throughout results section]. For example, van Boekel and colleagues (2015, [8]) sampled 723 key stakeholders (e.g., the general public, general practitioners, and mental health specialists) in the Netherlands and found that participant gender did not significantly predict desired social distance (a measure of discrimination) from people with SUDs (van Boekel et al., 2015).

The remaining 15 (55%) articles observed a significant relationship between gender and drug use-related stigma: 5 (33%) of these studies observed women held more stigmatizing views of PWUD [2,3,5,18,22], 6 (40%) observed men held more stigmatizing views of PWUD [6,7,16,20,25,26], and 2 (13%) reported mixed results in which men scored higher on one indicator of drug use-related stigma and women scored higher on another indicator [11,17]. For example, Brown and colleagues (2015, [3]) recruited 250 college students from a Midwestern university in the United States and observed women desired greater social distance (i.e., discrimination) and had more negative affect (i.e., prejudice) towards people who use marijuana compared to men (Brown, 2015). In contrast, Meurk et al. (2014, [7]), in a survey of 1,263 residents of Queensland, Australia, observed men were significantly more likely to endorse coercion into to treatment for a vignette character with heroin dependence compared to women (Meurk et al., 2014). While Nabors et al. (2012, [17]) observed women college students were more likely to report a desire to help in response to a vignette character with marijuana dependence, but men were more likely to score higher on ratings of liking and expectations for academic progress for this vignette character (Nabors et al., 2012).

Two additional studies (13%) from the interpersonal perspective reported that participants had more negative views of WWUD [14,24], and 1 study (7%) found that participants held more negative views of MWUD (Sorsdahl et al., 2012). For example, Sorsdahl and colleagues (2012,[14]) found, among 868 members of the South African general public, that participants were more likely to endorse coercion into treatment for MWUD, but were more likely to report avoiding women who use cannabis (Sorsdahl et al., 2012).

3.2.2. Quantitative Synthesis of Individual Stigma

Among the 13 quantitative studies assessing stigma from the individual perspective, most (8; 62%) were from North America, 2 (15%) were from Australia, 2 (15%) were from Asia, and 1 (8%) was from Europe. All studies reported the gender of recruited participants, though only 3 (23%) moved past a binary measurement of gender to include persons who are transgender, and only 2 of these three included transgender participants in their analyses. See Table 2 for the full analysis of the quantitative articles assessing stigma from the individual perspective.

Table 2.

A systematic review of quantitative studies investigating the intersection of gender and drug use stigma from the individual perspective (n = 13).

| Individual Perspective of Stigma | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Author (Year) | Study characteristics | Participant characteristics | Stigma-related variables | Summary of results | Quality Score | |||||

| n | Population | Location | Design | Age | Gender 4 | Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| 28 | Khuat (2015) | 403 | Women who inject drugs | Hanoi& Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | Cross-sectional survey design. | Hanoi Mean: 32.8 HCMC Mean 27.3 | 100% women | NR | Asked participants 3 questions about how they perceived society viewed WWID. | Over 80% of the sample agreed society viewed WWID to be worse than MWID and of “bad character.” Over half of the sample agreed society viewed female drug use as worse than sex work. | 7 |

| 29 | van Boekel (2016) | 186 | Individuals in treatment for substance use disorders. | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 40.9 Range: 16–70 | 31.2% women, 67.7% men. | NR | The Dutch version of the Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC-12) assessed experienced and anticipated stigma. | Gender did not significantly predict experienced or anticipated substance use stigma. | 13 |

| 30 | Rivera (2014) | 132 | People who inject drugs accessing syringe pharmacy | Manhattan/the Bronx, New York US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 42.7 | 19.9% women, 80.1% men. | 55.3% Lantinx, 31.1% White/Other, 13.6% Black | The Attitudes Towards Injection Drug Users Scale | Gender was not significantly related to PWID-related stigma scores. | 13 |

| 31 | Wilson (2014) | 236 | Needle and syringe program clients | Western Sydney, Australia | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 39.0 | 34.3% women, 64.8% men, 0.8% trans gender | 22% Aboriginal, 78% Non-Aboriginal | Five items assessing perceived discrimination from NSP staff/health care workers. | Perceived stigma and discrimination from general health workers was not correlated with gender or any injection outcome variables. | 11 |

| 32 | Crawford (2012) | 647 | Recently initiated people who inject drugs and PWUD (heroin, cocaine, crack) | New York City, NY (US) | Cross-sectional survey study. | Median: 33 | 29.5% women, 70.5% men. | 48.8% Black, 37.1% Hispanic, 14.1% White/Other | Items assessing experiences of dis crimination for a variety of characteristics (including drug use) | No significant gender differences in drug use discrimination. | 12 |

| 33 | Luoma (2009) | 252 | Adults in treatment for substance use related problems. | United States | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 30.5 Range: 18–63 | 42.1% women, 57.5% men. | 7 % Caucasian, 12% Latinx, 7% Other, 4% African American, 4% Native American, 1% Asian/Pacific Islander | Perceived Stigma of Addiction Scale (PSAS) Internalized Shame Scale (ISS) Internalized Stigma of Substance Abuse (ISSA) Stigma-Related Rejection Scale (SRS) - Adapted for substance use. | Perceived stigma (PSAS scores) was not related to gender. | 10 |

| 34 | Semple (2007) | 146 | Heterosexual, HIV negative adult women who use meth. | San Diego, CA (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 35.4 Range: 18–56 | 100% women | 45.2% Caucasian, 30.8% African American, 13.7% Latina, & 10.3% Other | Social stigma of meth use (14 items) | Women who had higher depressive symptoms had higher scores on social stigma of meth use. | 12 |

| 35 | Semple (2005) | 292 | Heterosexual adults who use meth. | san Diego, CA (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 37.8 | 27.7% women, 72.3% men. | 54.8% Caucasian | Three stigma scales developed for the study: (1) Expectations of rejection, (2) Experiences of rejection, & (3) Stigma coping strategies. | Gender was not correlated with experiences or expectations of rejection. | 11 |

| 36 | Friedman (2016) | 751 | People who inject drugs, High-risk heterosexuals, & men who have sexwith men | New York (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | PWID Mean: 40.9 HRH Mean: 32.6 MSM Mean: 25.6 | PWID: 44% women, 56% men. HRH: 48% women, 52% men, (4 trans participants not in anlyses) MSM: 100% men | PWID: 54% Black, 57% Hispanic. HRH: 71% Black, 66% Hispanic. MSM: 56% Black, 54% Hispanic. | Five items assessing perceived attacks on participant dignity, witnessing dignity attacks on others, characteristics participants were attacked for, reactions to dignity attacks, and who committed the dignity attack. | 1% of PWID reported their dignity being attacked due to their gender - though MSM were more likely to report this than PWID. Also, 41% of dignity attacks for PWID came from mothers. And mothers were more likely to be reported as sources of dignity attacks for PWID than HRH or MSM. | 13 |

| 37 | Cama (2016) | 102 | People who inject drugs accessing an NSP | Sydney, Australia | Cross-sectional survey design. | lean: 39.4 | 23% women, 75% men, 2% transgender | NR | Seven items from an adapted Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) Five items to assess perceptions of discriminatory treatment by staff at the NSP. | Gender was not correlated with internalized stigma. | 11 |

| 38 | Semple (2009) | 402 | Heterosexual adults who use meth | San Diego, CA (US) | Cross-sectional survey design. | Mean: 36.9 Range: 18–63 | 33% women, 67% men. | 55% Caucasian, 29.9% African American, 15.1% Latinx | 14 item social stigma scale comprised of two dimensions: (1) Culturally-induced expectations of rejection, and (2) experiences of rejection. | In ethnicity by gender analyses - no significant gender differences in rejection were found. | 10 |

| 39 | Palamar (2012) | 700 | Adults | United States | Internet-based survey design. | Mean: 29.3 | 69% women, 31% men. | 67.1% White, 12.2% Hispanic, 9.1% Asian American, 7.3% Black, 4.3% Other | 10-item Stigma of Drug Users Scale. Measures perceptions of public stigma towards users. Developed a pe ceiv d rejection anc secrecy scale: 2 %ctors - (1) perceived rejection and (2) secrecy (anticipated stigma) | Older and male PWUD reported greater perceived rejection for substance use. There were no gender differences in secrecy regarding substance use. | 12 |

| 40 | Heath (2016) | 440 | Adult PWID | Bangkok, Thailand | Cross sectional survey design. | Median: 38 | 19.5% women, 80.5% men. | NR | One item of health care avoidance: “Do you sometimes avoid accessing healthcare services because you are a drug user?” | There were no gender differences in health care avoidance. | 13 |

NR = Not Reported.

Three-quarters (10; 77%) of these individual perspective articles, including the 2 studies that moved past the binary measurement of gender, found no significant relationship between gender and drug use-related stigma [29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,40]. Further illustrating this, Cama et al. (2016, [37]) observed, among 102 persons who inject drugs from Sydney, Australia, that gender was not associated with internalized injection drug use stigma (Cama et al., 2016).

Three (23%) articles did observe a significant relationship between gender and drug use-related stigma: 2 (67%) of these studies observed that WWUD perceived or experienced greater levels of drug use-related stigma [28,34], and 1 (33%) study reported that MWUD experienced greater levels of drug use-related stigma (Palamar, 2012) [39]. For example, Khuat et al. (2015. [28]) found, among a sample 403 women who inject drugs (WWID) in Vietnam, that over 80% agreed that society perceives WWID to be “worse” than men who inject drugs, and 55% agreed that the community views women’s substance use more negatively than sex work (Khuat et al., 2015). In contrast, research from Palamar and colleagues (2012, [39]) observed, among a sample of 700 PWUD in the United States, MWUD reported higher levels of perceived drug use-related rejection compared to WWUD (Palamar, 2012). Additionally, 6 (46%) of these studies also measured drug use-related outcomes, though none tested the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between drug use-related stigma and drug use outcomes.

3.2.3. Quantitative Stigma Measurement

There was large variability in the measures employed to assess drug use-related stigma. Among the 27 articles that assessed stigma from the interpersonal perspective: 12 (44%) studies used 11 different pre-existing measures of drug use-related stigma, 7 (26%) studies developed drug use-related stigma items for their respective studies, 9 studies (33%) adapted an existing mental illness stigma measure, 3 (11%) used select items from an existing mental illness stigma measure, and 1 (3%) adapted an HIV stigma measure. A little over half (56%) of these studies either reported, or provided a reference for, the reliability of the employed measures, 11 (41%) studies provided information on the validity of the measure used, and only 6 (22%) reported both the reliability and validity of the measure.

Among the 13 articles that assessed stigma from the individual perspective: 5 (39%) studies used four different pre-existing measures of drug use-related stigma, 4 (31%) employed drug use-related stigma items developed for their respective studies, 6 (46%) adapted a mental health stigma measure, 1 (8%) adapted an HIV stigma measure, and 1 (8%) adapted an HCV stigma measure. Additionally, 9 (69%) studies reported the reliability of the measures employed, 5 (39%) reported the validity, and 4 (31%) reported both. Both the variability in the stigma measures used and the absence of information on the psychometric properties of these measures limit our ability to assess whether the mixed results regarding the impact of gender on drug use stigma might have been influenced by the way stigma was measured.

3.3. Qualitative Thematic Synthesis

Of the 35 included qualitative articles, 7 (20%) assessed stigma from the perspective of non-substance using individuals (i.e., the interpersonal perspective) and 28 (80%) from the perspective of PWUD (i.e., the individual perspective). The thematic synthesis, however, examined interpersonal and individual articles collectively.

For those seven interpersonal perspective articles, most (4; 57%) were from North America, with fewer from Africa (2; 29%), and Asia (1; 14%). Four articles (4% did not report participants’ age, gender, or race/ethnicity. Nearly half (3; 43%) of the articles reported participant gender, though none of these moved past a binary measurement of gender. See Table 3 for the full analysis of the interpersonal perspective qualitative articles.

Table 3.

A systematic review of qualitative studies investigating the intersection of gender and drug use stigma from the interpersonal perspective (n = 7).

| Interpersonal Perspective of Stigma | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | First author (year) | Study characteristics | Participant characteristics | Theme(s) | Quality Score | |||||

| n | Population | Location | Method | Age | Gender | Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| 41 | McKenna (2011) | 10 novels, 3 seasons of Breaking Bad, 8 movies, 6 TV episodes | Media portrayals of meth use. | United States | Content analysis of popular media. | NR | NR | NR |

Theme: Societal Expectations of

Womanhood Code - Cleanliness/Attractiveness |

8 |

| 41 | Myers (2009) | 20 | Key informants from a Historically Disadvantaged Community | Cape Town, South Africa | In-depth interviews. | NR | NR | NR |

Theme: Societal Expectations of

Womanhood Code- Morality |

8 |

| 43 | Beckerleg (2008) | 300 (survey) | Producers and consumers of khat | Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda | Field work and survey interviews. | NR | NR | NR |

Theme: Stereotypes of Promiscuity for

WWUD; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Code - Morality |

6 |

| 44 | Deng (2007) | 34 | HIV+ PWUD, their family members, and key informants in the Dai community | Yunnan, China | Participatory observations, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, & community mapping. | Range: 25–51 |

7.7% women, 92.3% men | NR |

Theme: Societal Expectations of

Womanhood Code - Motherhood |

9 |

| 45 | Laudet (1999) | 62 | Male partners of crack-dependent mothers | New York City, NY (US) | Semi-structured life history interviews. | Range: 21–58 |

100% men | 81% African American, 13% Hispanic, 6% White |

Theme: Stereotypes of Promiscuity for

WWUD; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Codes - Motherhood & Cleanliness/Attractiveness |

8 |

| 46 | Fielder (2005) | 25 | People who use drugs (HIV+ and HIV−) | Connecticut (US) | Mixed methods study with qualitative focus groups. | NR | 60% wer women | NR | Theme: Substance Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

| 47 | Greenfield (2014) | 32 | Substance use treatment agencies/stakeholder | Albuquerque, NM (US) | Semi-structured interviews. | NR | NR | NR | Theme: Substance Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

NR = Not Reported.

Among the 28 individual perspective articles, a little over half (15; 53%) were from North America, 6 (21%) were from Asia/the Middle East, 3 (11%) were from Australia/New Zealand, 1 (4%) was from Europe, 1 (4%) was from Africa, and 2 (7%) were global in scope. Most (26; 93%) studies reported the gender of recruited participants, 2 of which (8%) moved past a binary measurement of gender to include persons who are transgender. See Table 4 for the full analysis of the individual perspective qualitative articles.

Table 4.

A systematic review of qualitative studies investigating the intersection of gender and drug use stigma from the individual perspective (n = 28).

| Individual Perspective of Stigma | ||||||||||

| # | First author (year) | Study characteristics | Particiant characteristics | Themes | Quality Score | |||||

| n | Population | Location | Method | Age | Gender | Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| 48 | King (2016) | 94 | Key populations (female sex workers, people who inject drugs, people living with HIV, recently incarcerated) and outreach workers/stakeholders | Tajikistan | Key informant interviews, roundtables, and focus groups. | NR | NR | NR |

Themes: WWUD Experience

“Double” Stigma; Societal Expectations of Womanhood

Code - Cleanliness/Attractiveness |

8 |

| 49 | Myers (2016) | 37 | Young women who use alcohol and other drugs (AODs) and service providers | South Africa | Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. | Mean: 18.7 Range: 16–21 |

100% women | 52% Black/African American, 48% Coloured | Themes: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma; Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

| 50 | Howard (2015) | 20 | Postpartum women who had opioid use disorders (prescription medicates and synthetic narcotic analgesics only) | Maine, Massachusetts, Rho de Island (US) | Focus group interviews. | Range: 20–38 Mean: 28 |

100% women | 100% White | Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 9 |

| 51 | Orza (2015) | 766 | Women living with HIV | 94 countries (global) | Mixed methods study with open ended questions on an online survey. | Mean: 32.98 | 100% women | 8.1% Indigenous | Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

| 52 | Morse (2015) | 24 | Women in drug treatment court, service providers, and staff. | New York (US) | Focus groups. | DTC Mean: 39.9 Provider Mean: 45.7 Staff Mean: 42.8 |

79.2% women, 20.8% men | NR | Theme: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma | 8 |

| 53 | Benoit (2015) | 34 | Parents who have used, or currently use, substances. | Victoria, British Columbia (Canada) | In-person interviews (part of a larger mixed methods parent study) | Mean: 29 | 76% women, 24% men. | 50% Aboriginal, 44% White, 6% Visible Minority | Theme: Societal Expectations of Womanhood Subtheme - Motherhood | 8 |

| 54 | Spooner (2015) | 19 | Women who inject drugs | Java, Indonesia | In-depth interviews. | Range: 9–36 Mean: 25 |

100% women | Most were Javanese, 10.5% had mixed ethnic background. | Themes: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma; Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

| 55 | Jessell (2015) | 46 | Young adults who reported non-medical pres cription opioid use. | New York (US) | Mixed methods study with in-depth semi-structured interviews. | Range: 18–32 Mean: 25.3 |

39% women, 59% men, and 2% transgender | 69.6% White, 19.6% Latinx, 6.5% Black/African American, 4.3% Asian/Pacific Islander | Theme: Stereotypes of Promiscuity for WWUD | 9 |

| 56 | McNeil (2015) | 23 | People who smoke crack and access the SSR | Vancouvei, Canada | Ethnographic observation and in-depth interviews. | Range: 27–59 | 48% women, 52% men. | 35% identified as a visible minority. | Theme: Gender-Based Violence for WWUD | 8 |

| 57 | Chandler (2014) | 19 | Opioid-dependent adults in the antenatal/postnatal period | Scotland, UK | Longitudinal qualitative interviews. | Range: 23–39 | 74% women, 26% men. | 100% White | Theme: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma | 8 |

| 58 | Morse (2014) | 25 | Key stakeholders (women drug court participants, court staff, service providers) | New York (US) | Focus groups. | DTC:19–58 Provider: 3255 Staff: 30–52 |

DTC:100%

women Provider: 77.8% women, 22% men. Staff: 55.6% women, 37.5% men. |

DTC: 62.5% White, 37.5% Black Provider: 22.2% Hispanic, 22.2% White, 55.6% Black Staff: 100% White |

Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 8 |

| 59 | Otiashvili (2013) | 89 | Women who use drugs and service providers | Republic of Georgia | Secondary analysis of in-depth interviews. | PWUD: Range: 18–55 Mean: 35.7 | PWUD:100% women | PWUD:100% Georgian |

Themes: Drug Use Stigma for Women in

Health Care; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Code - Morality |

8 |

| 60 | Davidson (2012) | 47 | People who inject drugs | Tijuana, Mexico | In-depth focus groups. | NR | NR | NR |

Themes: Drug Use Stigma for Women in

Health Care; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Code - Motherhood |

9 |

| 61 | Chan (2010) | 15 | Women who had been pregnant in a methadone program & methadone clinic staff. | New Zealand | A mixed methods study with semi-structured inters interviews.. | NR | 100% women | NR | Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 7 |

| 62 | van Olphen (2009) | 17 | Women who had recently left jail. | San Francisco, CA (US) | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. | Range: 22–43 Mean: 40 |

100% women | 58.8% African American, 11.8% White, 11.8% Asian, 11.8% Mixed Race, 5.9% Native America | Theme: Gender-Based Violence for WWUD | 9 |

| 63 | Razani (2007) | 106 | People who inject drugs & key informants | Tehran, Iran | Key informant interviews and focus group discussions. | Interview Range: 19–55 Mean: 36.5 Focus Group Range: 20–61 Mean: 32 |

Interviews : 7.6% women, 92.4% men Focus Groups:100% women |

NR | Theme: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma | 8 |

| 64 | Bobrova (2006) | 86 | People who inject drugs | Volgograd & Barnaul, Russia |

Semi-structured qualitative interviews. | Range: 16–44 Mean: 27 |

18.6% women, 91.4% men | NR | Theme: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma | 9 |

| 65 | Copeland (1997) | 32 | women who had recovered from alcohol or other drug problems. | Australia | Interviews with closed and open-ended questions. | Range: 21–77 | 100% women | 94% AngloSaxon |

Themes: WWUD Experience

“Double” Stigma; Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care;

Stereotypes of Promiscuity for WWUD; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Code -Morality & Motherhood |

6 |

| 66 | Mora-Rios (2017) | 35 | People who use drugs, family members, and service providers | Mexico City, Mexico | In-depth interviews. | Family Range: 33–70 Provider range: 27–59 PWUD Range: 22–53 |

54% women, 46% men. | NR | Theme: Gender-Based Violence for WWUD | 8 |

| 67 | Lozano-Verduzco (2016) | 13 | Women who resided in a mutual-aid rehabilitation center | Mexico City, Mexico | Semi-structured interviews. | Range: 18–55 Mean: 20.4 |

100% women | NR | Themes: Gender-Based Violence for WWUD; Stereotypes of Promiscuity for WWUD | 8 |

| 68 | Gunn (2016) | 58 | Young adult former Soviet Union (FSU) immigrants who reported recent opioid use, FSU mothers of opioid using youth, and service providers. | New York City, NY (US) | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. | Young FSU: Range: 18–29 Mean: 23.3 |

Young FSU immigrants: 31% women, 69% men. FSU mothers of opioid using youth: 100% women. Service providers: 60% women, 40% men. |

NR |

Themes: WWUD Experience

“Double” Stigma; Stereotypes of Promiscuity for

WWUD; Societal Expectations of Womanhood Codes-Morality & Motherhood |

7 |

| 69 | Haritavorn (2016) | 30 | Mothers who inject drugs. | Bangkok, Thailand | In-depth interviews. | Range: 20–47 | 100% women | NR |

Theme: Societal Expectations of

Womanhood Code -Motherhood |

9 |

| 70 | Lawless (1996) | 27 | Women living with HIV | Sydney, Australia | In-depth interviews. | Range: 22–55 | 100% women | NR | Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 7 |

| 71 | Bungay (2011) | 60 | Women constructing crack smoking harm reduction kits & women with a self-reported history of crack use. | Downtown East Side neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada | Informal and in-depth interviews. | NR | 100% women | NR | Theme: Gender-Based Violence for WWUD | 9 |

| 72 | Oliva (1999) | 63 | Women at high-risk for HIV | San Francisco, CA (US) | Focus group discussions. | Range: 21–47 Mean: 35 |

100% women | 42% African American, 42% White, 10% Latina, 6% Other | Theme: Drug Use Stigma for Women in Health Care | 7 |

| 73 | Gunn (2015) | 30 | Women in residential drug treatment | Midwestern, US | In-depth interviews | Range: 19–56 | 100% women | 62% African American, 24% Caucasian, 14% Latina |

Theme: Societal Expectations of

Womanhood Codes -Morality & Motherhood |

9 |

| 74 | Krug (2015) | 132 | People who inject drugs | 14 Countries | Community consultations | 18–20: 37% 21–25: 48% 26–30: 15% | 25.7% women, 73.5% men, & .8% transgender | NR | Theme: WWUD Experience “Double” Stigma | 9 |

| 75 | Earnshaw (2013) | 12 | Methadone Maintenance Treatment Patients | New Haven, CT (US) | Secondary qualitative analysis | Range: 22–52 | 33.3% women, 66.7% men. | 83.3% White, 16.7% African American | Theme: Stereotypes of Promiscuity for WWUD | 9 |

NR = Not Reported.

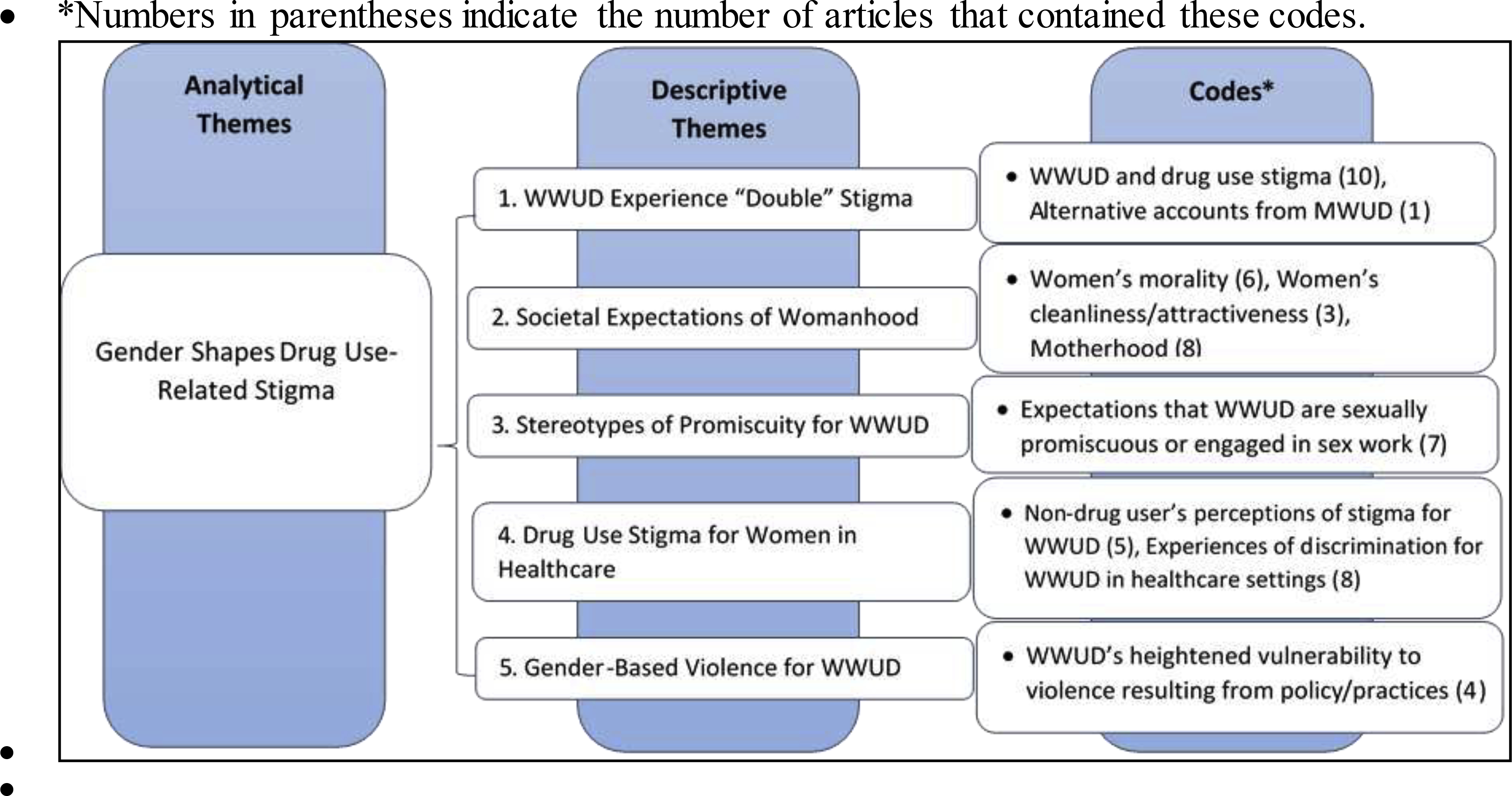

All of the included articles contained themes related to either men or women experiencing heightened drug use-related stigma, though none referenced themes related to transgender participants’ experiences with drug use stigma. Nearly all of these articles (34, 97%) highlighted experiences of WWUD with heightened drug use-related stigma [41–56,58–75]. One article (3%), however, illustrated that there may be contexts in which MWUD experience greater drug use-related stigma (described below) [57]. The overarching analytical theme for this synthesis explored how gender serves to shape manifestations of drug use-related stigma. Five descriptive themes further emerged; (1) WWUD’s experiences of “double” stigma, (2) societal expectations of womanhood and their impact on drug use-related stigma, (3) stereotypes of promiscuity for WWUD, (4) drug use-related stigma for WWUD in healthcare settings, and (5) gender-based violence for WWUD (See Figure 3). These descriptive themes capture unique facets of the intersection of gender and drug use-related stigma, but these themes were not mutually exclusive and there were instances in which they overlapped and intersected (See Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 3. The analytical themes, descriptive themes, and codes developed for a synthesis of the qualitative studies exploring the intersection of gender and drug use-related stigma (n = 35).

3.3.1. Women Who Use Drugs’ Experiences of “Double” Stigma

Ten (29%) of the included articles contained themes focusing on WWUD’s experiences with heightened levels of stigma due to their intersecting identities as a woman and as a PWUD [48,49,51,52,54,63,64,65,68,74]. These articles explored how these intersectional identities can lead WWUD to experience “double” the stigma and can negatively impact their well-being as well as lead to social isolation. This sentiment was further illustrated through the ‘hard to reach’ nature of WWUD in research, and the potential for the underrepresentation of WWUD due to anticipated stigma. One study in Tehran, Iran observed that drug use among women was so stigmatized that it was causing a high “no-show” rate for WWUD interviewees (Razani et al., 2007, [63]). As such, the investigators determined it was inappropriate to recruit a woman-only focus group in this context, thereby missing valuable information from a key sub-population of PWUD (Razani et al., 2007). A single alternative account from Scotland suggests there may be contexts in which MWUD may experience more severe drug use-related stigma related to the gendered-associations of specific drug types (Chandler et al., 2014, [57]) (i.e., the stereotype that benzodiazepines are “mother’s little helper,” which contributes to the greater stigmatization of a father’s benzodiazepine use). Despite this anomalous account, however, most of the included articles observed ways in which WWUD are differentially impacted by drug use-related stigma. See the Supplemental Table for a full list of narratives corresponding to each descriptive theme.

3.3.2. Societal Expectations of Womanhood

Several articles explored how societal expectations of women’s morality (6; 17%) [41,43,59,65,68,73], cleanliness and attractiveness (3; 9%) [41,45,48], and roles as mothers (8; 23%) [44,4553,60,65,68,69,73], shaped experiences of drug use-related stigma for WWUD. These studies described how drug use-related stigma can be amplified for WWUD due to the higher moral standards society has for women compared to men. As such, drug use by women is seen as a violation of these moral expectations and results in the greater stigmatization of WWUD.

‘For example, almost all respondents suggested that HDCs [historically disadvantaged communities] believe “these are good women gone bad” For female “addicts”, these discourses are defined against commonly-held discourses about what it means to be a “good woman.”’ (Myers, 2009, South Africa, pg. 3, [41]).

Studies also reported that WWUD were often seen as “dirty” or as lacking womanhood, even within drug using networks, and therefore were no longer viewed as attractive. These social norms regarding what it means to be a “good”, “clean”, and “attractive” woman serve to exacerbate drug use-related stigma for WWUD.

Lastly, women face societal expectations surrounding motherhood, and studies reported that drug use was perceived to be a transgression that impeded WWUD’s ability to be “good” mothers, especially when children were removed from their care. This stigmatization of WWUD occurred not only from non-drug using individuals, but also from WWUD themselves in the form of internalized stigma. One study from Victoria, Canada observed that many WWUD described guilt and self-judgement regarding their drug use during parenting or pregnancy, regardless of the relative harms of their use (Benoit et al., 2015, [53]). In one alternative account, motherhood was viewed as an identity that could potentially supersede and mitigate the identity of “drug user” for WWUD accessing syringe services (Davidson et al., 2012, [60]). This dynamic was rare, however, and the intersection between cultural expectations of motherhood with drug use often contributed to increased stigmatization for WWUD.

3.3.3. Stereotypes of Promiscuity for Women Who Use Drugs

Seven articles (20%) also highlighted existing stereotypes related to promiscuity and sex work for WWUD [43,45,55,65,67,68,75]. Both WWUD and non-drug using individuals reported either encountering or believing negative stereotypes regarding the sexual propriety of WWUD. These stereotypes focused on the idea that WWUD engage in sexual behavior that violates social norms for women, including sex work, resulting from their drug use. The stereotypes accounted for the increased stigmatization of WWUD, and in some instances, the sexual devaluation and exploitation of WWUD:

‘One participant noted that female employees with a history of drug addiction are often stereotyped by male employers as prostitutes. She stated: “It’s like men employers … the managers are sleaze bags. Like, they try to get with you. You know they know you’re a drug addict, they know you’re in a program, you may not have money … So it’s like they characterize you, you know ‘cause you’re a drug addict or you’re a prostitute or whatever the case may be. ”’ (Earnshaw, 2013, Connecticut, US, pg. 7, [75]).

As such, existing societal mores regarding women’s sexuality and the negative stereotypes regarding WWUD’s sexual behavior can serve to place WWUD in precarious positions that adversely impact their health and wellbeing.

3.3.4. Substance Use Stigma for Women in Healthcare

The articles included within this descriptive theme illustrate experiences of intersectional drug use stigma for WWUD within healthcare settings. These articles include accounts of drug use-related stigma from both the interpersonal (5; 14%) [46,47,49,51,60] and individual perspectives (8; 23%) [50,54.58,59,61,65,70,72]. In a South African study, non-drug using individuals reported that WWUD are not viewed as a “policy or funding priority,” and that this omission from the policy and funding discussion within the healthcare arena further results in women being an underserved population of PWUD (Myers et al., 2016 [49]). These structural level oversights result in a lack of gender-specific drug treatment and other health-related services, which creates important barriers to care and serves to further perpetuate vulnerability for WWUD.

Studies from the individual perspective also highlight that healthcare settings are frequently sites of discrimination for WWUD based on their identities as women and as PWUD. Authors described women receiving poor quality health care, including obstetric and gynecological care, due to healthcare providers’ prejudice against WWUD. Further, many articles reported women feared child protective services (CPS) involvement when accessing health care, due to mandatory reporting policies that penalize WWUD. As such, past experiences of discrimination, WWUD’s own internalized stigma, and anticipated stigma from CPS involvement served as significant barriers to accessing care for this population:

‘Many drug-using women reported negative experiences with medical providers and only sought health care when they were so ill they had no choice. The women generally felt that medical personnel were hostile and did not take their problems seriously … Many women reported feeling pain and discomfort during vaginal exams because doctors used the wrong size speculum or conducted the exam in a rough or rushed fashion. Others reported that providers refused to provide care once they learned of their drug use.’ (Oliva, 1999, California, US, pg. 9, [72]).

This indicates that existing intersectional gender- and drug use-related stigma has negative consequences for the physical health and treatment of WWUD.

3.3.5. Gender-Based Violence for Women Who Use Drugs

In addition to accounts of WWUD experiencing stigmatization and discrimination in healthcare settings, the included articles also discussed how current drug use-related stigma can be intertwined with gender-based violence for WWUD (5; 14%) [56,62,66,67,70]. This violence can occur within unregulated drug use settings, in drug treatment environments, and even in the social environments of families and intimate partnerships. For example, the following excerpt illuminates how the societal prejudice against, and devaluation of, WWUD can contribute to coercion and violence towards this group: ‘Female substance users are usually the object of greater social rejection. One informant described having been sedated by family members and forced to sign away her inheritance. Another related her alcohol abuse to depression caused by her partner’s violence, which led her to attempt suicide and resulted in hospitalization’ (Mora-Rios, 2016, Mexico City, Mexico, pg. 8, [66]).

4. Conclusion

4.1. Summary of the Evidence

There was a lack of consensus across 40 quantitative studies regarding the association between gender and drug use-related stigma.. In contrast, the majority of the 35 qualitative studies evaluated (34; 97%) observed WWUD experienced heightened stigma resulting from their intersectional gender- and drug use-related identities. One study (1; 3%), illustrated that MWUD may also face intersectional gender- and drug use-related stigma in specific geo-cultural contexts. Further, though structural manifestations of drug use-related stigma were included in the a priori coding scheme, all included quantitative studies, and most qualitative studies, only assessed individual and interpersonal manifestations of drug use-related stigma. Similarly, though drug use-related outcomes (e.g., drug misuse or drug use risk behaviors) were included in the a priori codebook, no quantitative studies tested the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between drug use-related stigma and those drug-related outcomes.

The discrepancies in the impact of gender on drug use-related stigma observed across the quantitative studies, in contrast with the consistency observed across the qualitative studies, suggest the current quantitative drug use stigma measures may not adequately capture the intersectional nature and multiplicative effect of gender- and drug use-related stigmas, particularly for WWUD. This could be due, in part, to the large variability in stigma measures employed across studies. Nearly half (17; 43%) of the included quantitative studies employed one or more of 15 different drug use-related stigma measures. Additionally, 15 (37%) studies adapted a measure of mental health stigma while the remaining studies (8; 20%) either adapted measures of other stigmatized characteristics (i.e., HIV or HCV), selected specific items from existing drug use stigma measures, or developed their own items to assess drug use-related stigma. These varied approaches to measuring drug use-related stigma are similar to the documented variability in employed measures assessing mental illness stigma (Fox et al., 2018), and underscore the need for synchronization regarding the operationalization of definitions and terms in drug use-related stigma, as well as the standardization of quantitative measures. Also, notably, across all quantitative measures, item content reflects PWUD as a homogeneous archetype, and does not reflect the dimensions by which gender might shape how drug use stigma is experienced (e.g., in the context of parenthood).

In contrast with the quantitative literature, the synthesis of the qualitative literature demonstrates that there is nearly universal agreement that WWUD experience heightened levels of drug use-related stigma, particularly in healthcare settings, from societal expectations of women’s morality, cleanliness, and motherhood. Qualitative research methods are uniquely positioned to explore WWUD’s experiences, processes, and meaning-making surrounding drug use-related stigma through describing these phenomena in women’s own words (Atieno, 2009; Ryan et al., 2007). As such, the qualitative literature on gender- and drug use-related stigma has been able to capture the intersectional nature of stigmatized identities for WWUD in a way that the quantitative measures of stigma have, thus far, not been designed to. Consequently, future research should draw from the existing qualitative literature, as well as existing intersectional stigma measures (i.e., measures assessing gendered racism), to better incorporate intersectionality in the tailoring of drug use-related stigma measures to the study populations of interest (e.g., WWUD), which could serve to better capture the magnitude of intersectional gender- and drug use stigma on WWUDs’ health and well-being (Rosenthal & Lobel, 2018; Turan et al., 2019). Accurately capturing the intersectional nature of drug use-related stigma for WWUD will serve as the foundation for the development of tailored interventions targeting stigma and associated harms among WWUD (i.e., depression symptoms, reduced healthcare utilization, and gender-based violence) (Kulesza et al., 2013; Room, 2009).

4.2. Limitations

This systematic review was limited in a few important ways. First, only articles published in English were included based on language limitations among the study team. A total of 35 non-English articles were excluded; 10 (28%) were in Spanish, 9 (25%) in German, 6 (17%) in French, 2 (6%) in Chinese, 2 (6%) in Japanese, 2 (6%) in Dutch, 2 (6%) in Swedish, 1 (3%) in Greek, and 1 (3%) in Portuguese. Despite most of the included and excluded articles originated from North America, Western Europe, and Australia, the exclusion of these articles could have potentially biased our findings. Additionally, the lack of a consensus on the definition of stigma in the extant literature (Kulesza et al., 2013), the heterogeneity of stigma measures, and the omission of sample characteristics limits the robustness of the systematic review’s findings and made undertaking a meta-analysis impractical (Leibovici & Falagas, 2009). However, this review exposed these existing gaps and inconsistencies in the scientific literature, providing an important foundation for future research on intersectional gender- and drug use-related stigma. In an effort to protect against bias, inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined prior to analyses, and coding was implemented by two independent raters screening all articles for inclusion (SAM, BD) and scoring the study quality of all included articles (SAM, NC) (Mueller et al., 2018). To guard against bias introduced by individual researchers in the interpretation of the qualitative synthesis, all themes and codes were developed iteratively and agreed upon by two social scientists with previous qualitative research experience (SAM, LRS). Given the sensitive nature of drug use and stigma, there may be response bias in each individual study included in the review. To further assess for this source of bias, and to aid in the interpretation of results, study quality scores were presented for each included study.

4.3. Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the intersection of gender- and drug use-related stigma. The results of current review and synthesis contribute valuable insights into the experiences of WWUD with drug use-related stigma and the gendered social norms that produce heightened levels of intersectional drug use- and gender-related stigma and gender-based violence for WWUD. Furthermore, this review serves to identify potential methodological weaknesses in the existing measurement of the gendered impact of drug use-related stigma on drug use-related behavioral outcomes. Current quantitative approaches to assessing drug use-related stigma are not only lacking a consistent operationalization of stigma, but also have not been designed or adapted to address the unique gendered stigma experiences of WWUD. As such, the equivocal nature of the conclusions drawn across the quantitative studies in contrast with the near-consensus observed across the qualitative studies highlights the need for intersectional approaches to drug use-related stigma research and the tailoring of stigma measures to be gender-responsive. Furthermore, none of the included studies assessed structural manifestations of drug use-related stigma or the moderating impact of gender on the relationship between drug use-related stigma and drug use-related outcomes (e.g., drug misuse or drug use risk behaviors). Future research should seek to understand how intersectional gender- and drug use-related stigma, particularly at the structural level, impact drug use processes for MWUD and WWUD. This information could be crucial for the development of gender-responsive treatments and interventions that target substance use and related risk behaviors, and thereby alleviate the disproportionate harms WWUD experience.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This is the first review of drug use stigma to employ an intersectional lens.

Quantitative studies are equivocal on the impact of gender on drug use stigma.

No quantitative studies tested the moderating effect of gender on this stigma.

Qualitative studies demonstrate that women experience greater drug use stigma.

Validated intersectional scales are needed to fully understand drug use stigma.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants and investigators whose work collectively informed this review. Additionally, we wish to thank Pearl Kuang, Lindsey Depledge, Nicholas Lee, Charles Marks, Jennifer Jain, Julie Bender, and Katherine Tarantowicz whose work informed both the parent and current systematic reviews. Investigators of the current work were supported through awards from the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (K01 DA039767, PI: Smith; DP2 DA040256–01, PI: Werb, K01 DA042881, PI: Earnshaw); the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R21 TW011785, PI: Smith); the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) via a New Investigator Award (Werb); the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science via an Early Researcher Award (Werb); and the St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation (Werb).

Stephanie Meyers was supported through NIDA grant R01 DA039950. Portions of this work were presented by the senior author (LRS) at the Society of Behavioral Medicine 38th Annual Meeting (April 2017, San Diego, CA) and the United Nations office of Drugs and Crime Expert Group Meeting on Stigma around Substance Use (January 2020, Vienna, Austria), and by the first author (SAM) at the Society of Behavioral Medicine 41st annual Meeting (April 2020, via the SBM app due to COVID-19).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.