Abstract

This study evaluates changes in rates of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or suspected stroke during COVID-19 surges in the US as a measure of willingness to seek care during the pandemic.

Early during the COVID-19 pandemic, marked declines in patients presenting with acute cardiovascular conditions were observed,1,2 whereas mortality attributed to cardiovascular causes increased.3 This raised concerns that patient reluctance to seek emergency care contributed to preventable complications and excess deaths, and public health campaigns sought to reassure patients that hospitals were safe and to encourage seeking care when needed. As COVID-19 resurged in late 2020, rates of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths exceeded those of previous surges. Many countries reimplemented lockdowns, and recent UK data indicate that presentations for emergent cardiovascular conditions again declined.4 We evaluated changes in rates of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) hospitalizations and suspected ischemic stroke as measures of patient willingness to seek emergency care during the most recent COVID-19 surges in the US.

Methods

We examined data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large, integrated health care delivery system with 21 medical centers and 255 clinics, providing comprehensive care for more than 4.5 million persons throughout Northern California. Its membership is highly representative of the local and statewide population regarding age, sex, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.5

We examined weekly incidence rates for adult members hospitalized for AMI or suspected acute ischemic stroke (ie, “stroke alerts”) who presented to KPNC facilities from January 22, 2019, to January 18, 2021. Acute MI was identified with a combination of discharge diagnosis codes and positive values of serum cardiac troponin I.1 Stroke alerts are tracked through a comprehensive stroke program at 21 Joint Commission stroke-certified KPNC facilities that includes immediate consultation by neurologists for evaluation and treatment for all suspected ischemic strokes.2,6 We excluded patients younger than 18 years, with unknown sex, or with lack of active health plan membership in each weekly cohort.

Weekly incidence rates of events per 100 000 person-weeks and 95% CIs for AMI and stroke alerts during COVID-19 periods (January 21, 2020, to January 18, 2021) and pre–COVID-19 periods (January 22, 2019, to January 20, 2020) were calculated. Incidence rates across 3 COVID-19 surge periods (spring, weeks 8-15; summer, weeks 23-30; and winter, weeks 42-52 of 2020) were compared with the same weeks during the pre–COVID-19 period by using incidence rate ratios (IRRs), with 2-sided P < .05 considered statistically significant. We also plotted the weekly incidence of COVID-19 hospitalizations. Analyses were conducted with R version 4.0.2. The study was approved by the KPNC institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

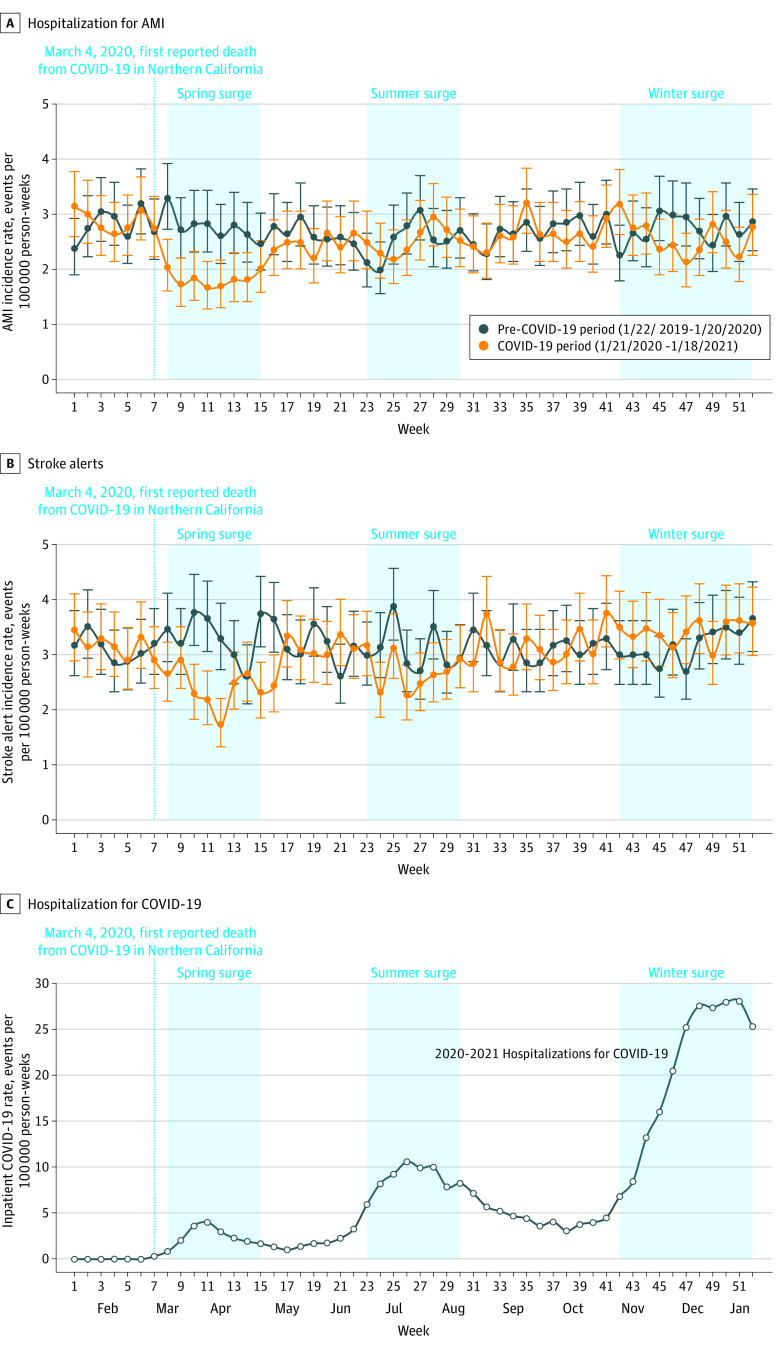

During 183 928 759 person-weeks from January 21, 2020, to January 18, 2021, weekly AMI hospitalization rates declined up to 41% (ie, incidence rate per 100 000 person-weeks, 1.66 vs 2.82; 95% CI, 1.29-2.14 vs 2.32-3.44; P = .001 for week 11, 2020 vs 2019) during the spring COVID-19 surge (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59-0.74; P < .001 for weeks 8 to 15) but recovered to 2019 rates in weeks 16 to 19 (IRR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.75-1.01; P = .07) (Figure, A). Similarly, weekly rates of stroke alerts declined during the spring surge (IRR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65-0.79; P < .001) but recovered in weeks 16 to 19 (IRR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.78-1.02; P = .10) (Figure, B). Despite larger increases in COVID-19 hospitalizations (Figure, C), no significant declines in AMI were observed during the summer COVID-19 surge (IRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.10; P = .65) or the winter surge (IRR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.86-1.03; P = .20). A statistically significant decline in stroke alerts was observed during the summer COVID-19 surge (IRR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79-0.96; P = .006), whereas no significant decline in stroke alerts was observed during the winter surge (IRR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.99-1.17; P = .07).

Figure. Acute Myocardial Infarction Hospitalizations and Stroke Alert Incidence During COVID-19 Surges Compared With the Pre–COVID-19 Period and Weekly COVID-19 Hospitalization Incidence.

Data are from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health system. The data are the estimated weekly incidence rates (events per 100 000 person-weeks) for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) hospitalizations (A) and stroke alerts (B) during the COVID-19 period (January 21, 2020, to January 18, 2021) compared with data from the pre–COVID-19 period (January 22, 2019, to January 20, 2020). C, Weekly incidence of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 per 100 000 person-weeks (based on the inpatient census at the start of each weekly period). The vertical dotted line marks the date of the first publicly reported COVID-19 death in Northern California (March 4, 2020). The shaded areas denote the spring (March 10 to May 4, 2020), summer (June 23 to August 17, 2020), and winter (November 3, 2020, to January 18, 2021) COVID-19 surges in Northern California.

Discussion

In contrast to the initial COVID-19 surge during March to April 2020 in the US and to recent data from the UK, no significant declines in AMI hospitalization or stroke alerts were observed during the largest and most recent surge during October 2020 to January 2021 in KPNC. A modest decline was observed for stroke alerts during the summer COVID-19 surge but quickly rebounded. Study limitations include an inability to delineate specific reasons for observed declines in AMI and stroke alerts and potential lack of generalizability to other regions or systems. These patterns may reflect changing patient attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic or the success of health system and public health campaigns to reassure patients about the safety of seeking emergency care when needed.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, et al. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):691-693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen-Huynh MN, Tang XN, Vinson DR, et al. Acute stroke presentation, care, and outcomes in community hospitals in Northern California during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51(10):2918-2924. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadhera RK, Shen C, Gondi S, Chen S, Kazi DS, Yeh RW. Cardiovascular deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(2):159-169. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J, Mamas MA, de Belder MA, Deanfield JE, Gale CP. Second decline in admissions with heart failure and myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(8):1141-1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon N, Lin T. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California adult member health survey. Perm J. 2016;20(4):15-225. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen-Huynh MN, Klingman JG, Avins AL, et al. ; KPNC Stroke FORCE Team . Novel telestroke program improves thrombolysis for acute stroke across 21 hospitals of an integrated healthcare system. Stroke. 2018;49(1):133-139. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]