Abstract

Whole genome sequencing data mining efforts have revealed numerous histone mutations in a wide range of cancer types. These occur in all four core histones in both the tail and globular domains and remain largely uncharacterized. Here we used two high-throughput approaches, a DNA-barcoded mononucleosome library and a humanized yeast library, to profile the biochemical and cellular effects of these mutations. We identified cancer-associated mutations in the histone globular domains that enhance fundamental chromatin remodeling processes, histone exchange and nucleosome sliding, and are lethal in yeast. In mammalian cells, these mutations upregulate cancer-associated gene pathways and inhibit cellular differentiation by altering expression of lineage-specific transcription factors. This work represents a comprehensive functional analysis of the histone mutational landscape in human cancers and leads to a model in which histone mutations that perturb nucleosome remodeling may contribute to disease development and/or progression.

Introduction

Establishment and maintenance of chromatin underlies transcription, DNA replication, and DNA repair, and disruption of these processes often occurs in human cancers1,2. More recently, mutations in histone proteins have been linked to rare cancers3,4, including H3.3K27M (pediatric gliomas), H3.3G34W/L (giant cell tumors of bone), and H3.3K36M (chondroblastomas and sarcomas)5–11. A key feature of these founding “oncohistone” mutations is their occurrence at or near sites of histone post-translational modification (PTM). Indeed, mutations at H3K27, H3G34, and H3K36 disrupt regulatory mechanisms by which key PTMs are installed and maintained6,11–14. Histone mutations also have been found in other cancers, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and uterine and ovarian carcinosarcoma, although these remain less studied15–18. Recent efforts to catalogue and characterize the histone missense mutational landscape of human cancers19,20 have revealed thousands of somatic mutations in genes encoding all four core histones across diverse tumor types (Fig. 1a). Many of these histone mutations occur with a frequency similar to that of somatic mutations in well-established, cancer-associated genes, such as BRCA2, TET2, SMAD4, and NOTCH1. Some of these histone mutations occur at or near sites of PTM (e.g. the aforementioned oncohistone mutations), however, the majority of high-frequency mutations occur in the folded, globular domains. Relatively few of these globular domain sites are known to be post-translationally modified, raising the question of whether these mutations function through mechanisms distinct from those of established oncohistones. Furthermore, although a select few of these histone mutations have been the subject of recent studies20–22, the vast majority remain entirely uncharacterized.

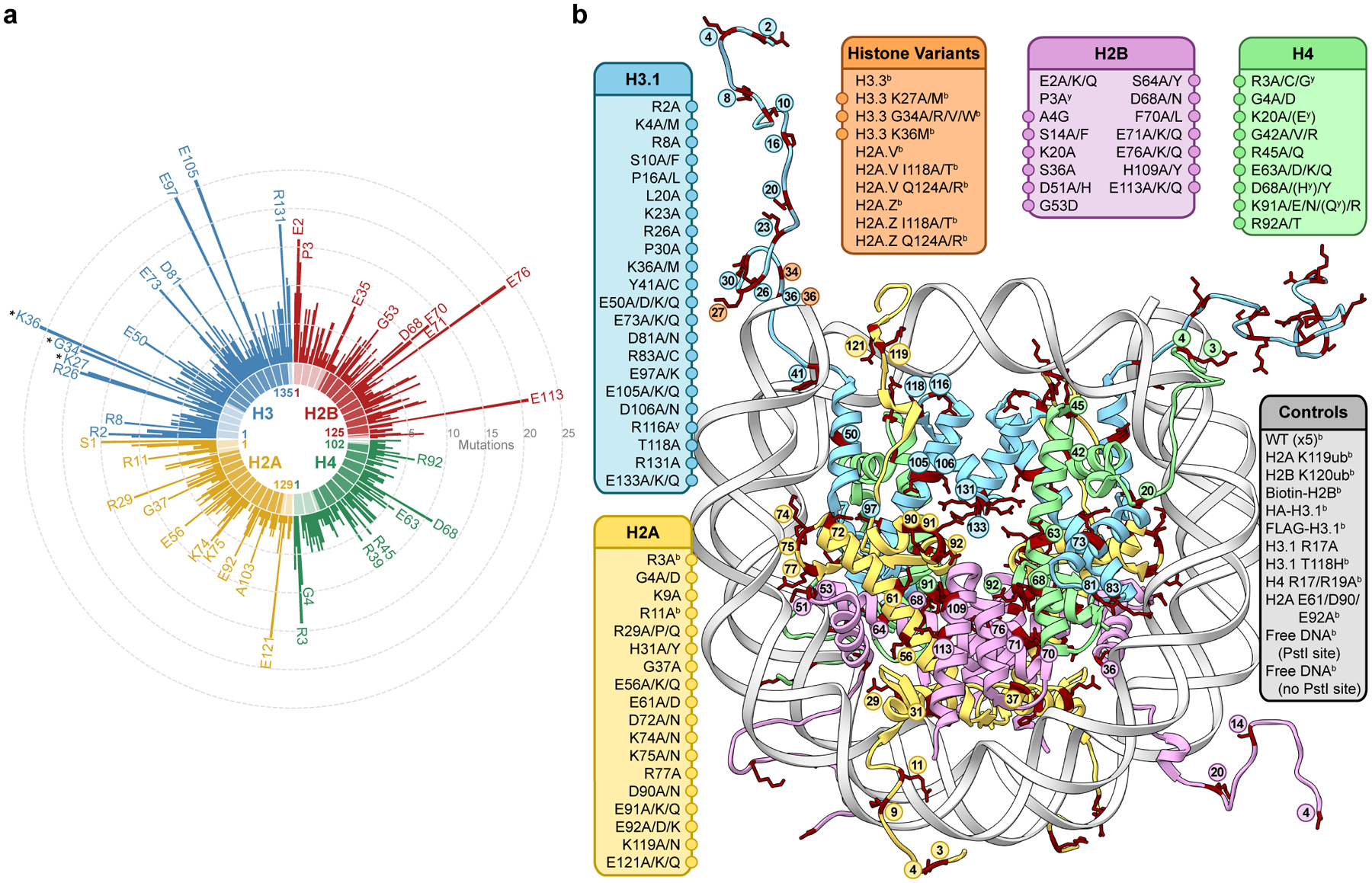

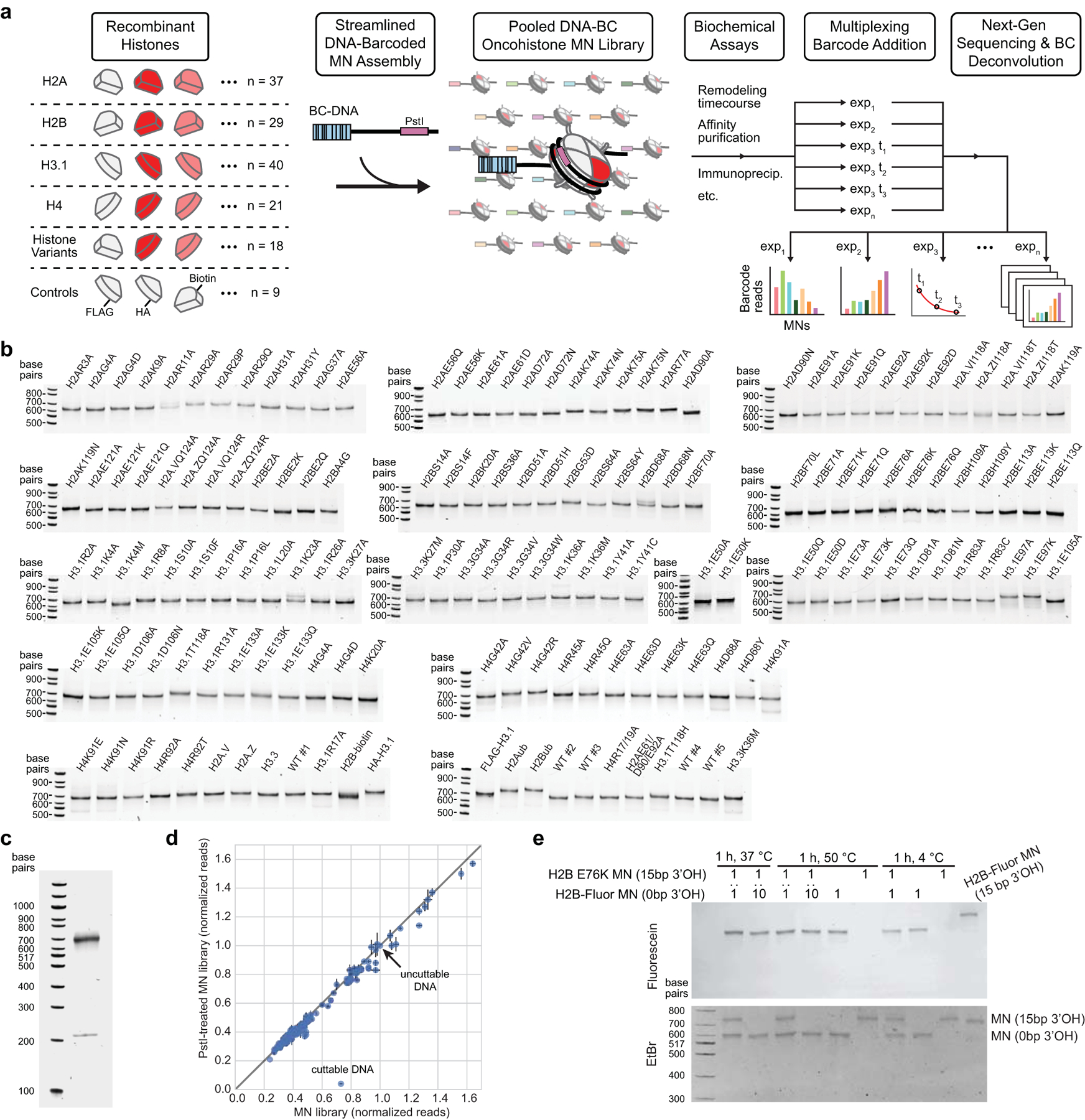

Figure 1 |. A library of cancer-associated histone mutations.

a, Circular barplot showing mutation counts in the four core histones in human cancers (data from Nacev et al., 2019)19. Select highly mutated sites are labeled, and established oncohistone mutations are denoted with an asterisk. Darker and lighter regions in each histone represent the globular and tail domains, respectively. b, Diagram depicting all histone mutants, variants, and controls included in the barcoded mononucleosome and humanized yeast libraries. Mutations with adjacent circles are displayed on the nucleosome structure with coordinated colors and labeled by residue. In addition to any specific missense mutations that were overrepresented in the dataset, alanine mutations were included at every site, offering both experimental redundancy as well as the ability to distinguish between loss and gain of function at a given amino acid residue. Indicated mutants are found only in the barcoded mononucleosome (b) or humanized yeast libraries (y), respectively (PDB 1kx5).

Here we report the systematic biochemical and cellular characterization of the newly identified oncohistone mutational landscape. We developed two complementary high-throughput screening tools for the rapid interrogation of these mutations: a DNA-barcoded mononucleosome (MN) library, which enabled single-pot biochemical evaluation of the effects of these mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS), and a “humanized” yeast library, which allowed evaluation of the phenotypic effects of human histone mutations in a cellular context. Together, these libraries enabled identification of mutations that alter fundamental chromatin remodeling processes, namely histone exchange and nucleosome sliding, and are lethal in yeast. Notably, unlike the aforementioned classical “oncohistone” mutations, many of these mutations occur in the histone globular domains. Expression of these mutant histones in mammalian cells caused significant changes in transcription, dysregulating cell-signaling and cancer-associated gene pathways, and impaired cellular differentiation. Collectively, this study presents an experimental platform for rapid biochemical and cellular interrogation of histone mutations and demonstrates the utility of these tools by identifying mutations that affect fundamental chromatin processes and alter cell fates. Moreover, this work suggests that cancer-associated histone globular domain mutations may contribute to disease development via perturbation of nucleosome remodeling.

Results

Generation of libraries to profile histone mutations

To enable expeditious interrogation of cancer-associated histone mutations, we narrowed the set of histone mutations found in over 3000 cancer patient samples to an experimentally tractable set likely to have functional effects in vitro and in cells (Extended Data Fig. 1, see methods for discussion of selection criteria). Importantly, for every mutated site chosen for analysis, we included an Ala mutation in addition to any specific missense mutations that were overrepresented in the dataset. This approach offered both experimental redundancy as well as the ability to distinguish between loss and gain of function at a given amino acid residue. The resulting list contained ~160 distinct histones, including experimental controls, which were incorporated into subsequent high-throughput screening approaches (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1). These mutations are distributed throughout all four core histones (including variants), providing broad biochemical and structural coverage of the nucleosome. Therefore, the experimental libraries described herein not only enable analysis of disease-associated histone mutations but also facilitate coarse-grained profiling of nucleosome structure-activity relationships. Thus, these libraries may additionally offer insight into the role of specific nucleosome regions or histone residues in normal chromatin physiology.

We then designed a DNA-barcoded mononucleosome (MN) library to enable high-throughput biochemical evaluation of the effects of these histone mutations using next-generation sequencing. We previously reported DNA-barcoded MN libraries to profile the effects of histone PTMs on various chromatin effectors23,24. Here we used an analogous approach to evaluate the impact of cancer-associated histone mutations on chromatin remodeling. Utilizing a streamlined MN reconstitution procedure (see methods), we assembled a MN library from purified recombinant mutant and wild-type human histones and a set of double-stranded DNAs, each containing the Widom 601 nucleosome positioning sequence flanked by a unique 6-bp molecular identifier (i.e. barcode) (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). Importantly, the presence of these barcodes allowed all subsequent biochemical experiments to be performed on the pooled mixture, exploiting the sensitivity and throughput afforded by an NGS-based readout. Additionally, we included five wild-type MN controls to assess potential variation in nucleosome behavior due to barcode sequence-specific effects and/or differences in nucleosome assembly. We confirmed the faithful assembly of this library via deep sequencing and demonstrated that barcode-histone scrambling does not occur, even under harsh conditions (Extended Data Fig. 2d, e).

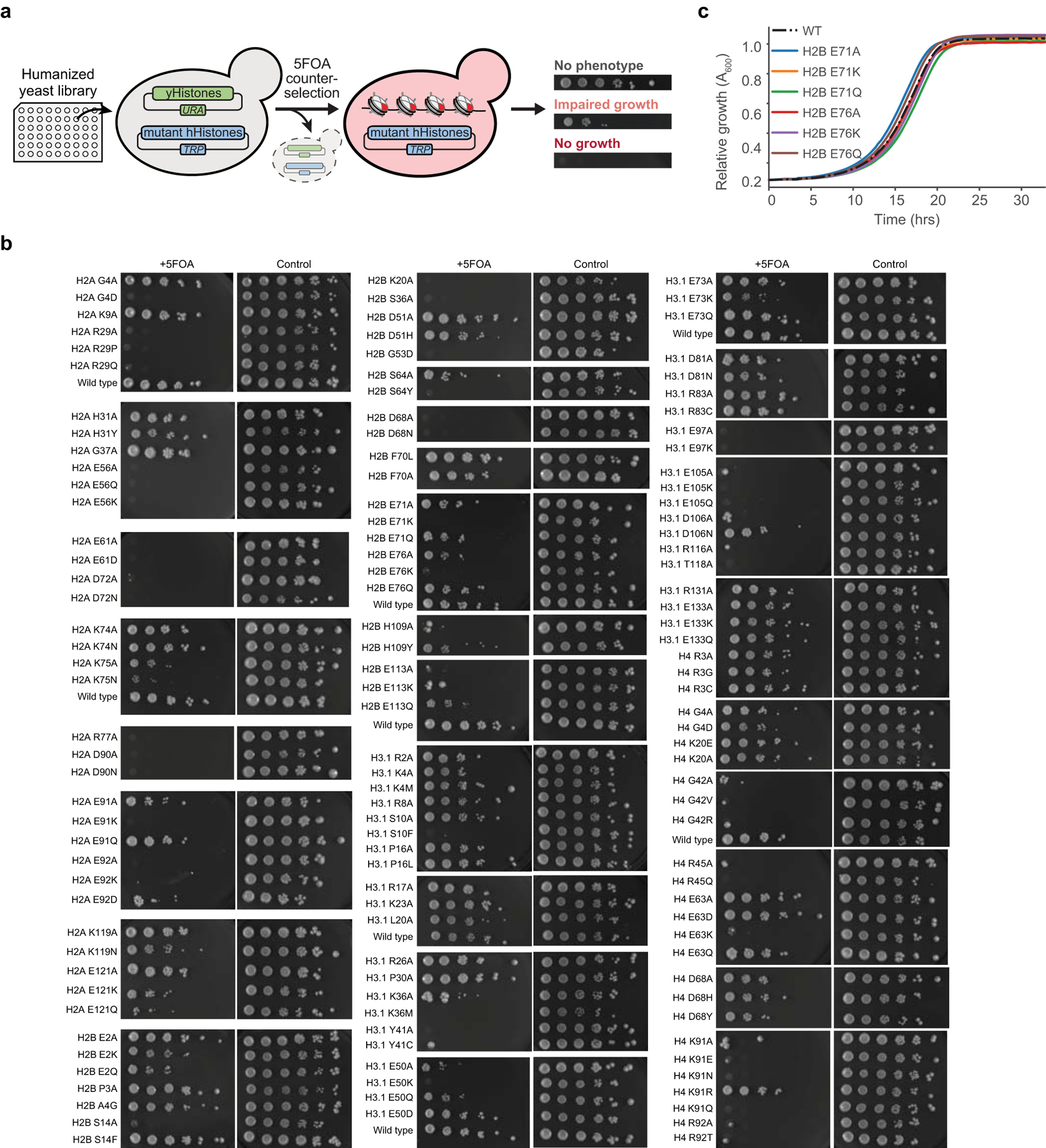

We also sought to develop an additional screening tool to assess the effects of histone mutations in more complex cellular environments. Previous studies have employed yeast (S. cerevisiae) as a model system for performing comprehensive mutagenesis of histones, wherein endogenous histone genes were replaced with yeast histone mutant sequences of interest25,26. To provide consistency between our biochemical and cellular libraries and avoid instances where the yeast corollary of human histone mutants was unclear, we adapted a screening platform that allows yeast histones to be fully replaced with human histones using a 5-fluoroorotic acid (5FOA) plasmid shuffle approach27. Yeast with humanized chromatin (hereafter “humanized yeast”) were originally generated to probe the fundamental relationship between chromatin, histone variants, and cellular functions. We envisioned that this system could be repurposed to assess the effects of cancer-associated histone mutations on cell viability (Extended Data Fig. 3a). With this in mind, we generated a library of 130 yeast strains containing a set of mutations similar to that present in our barcoded library (Extended Data Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 2). Importantly, phenotypic effects are not attributable to differential growth rates prior to 5FOA selection (Extended Data Fig. 3c), suggesting that observed growth defects instead reflect histone mutants that are compromised in an essential function. A notable advantage of this yeast screening approach is that, unlike in polygenic mammalian cells, the mutated histone gene is the only copy present in the organism, likely amplifying phenotypic effects and making them more readily detectable. Additionally, the structural effects of mutations that perturb nucleosome assembly, stability, and remodeling are likely preserved and detectable in this system (vide infra). Together, these libraries offered a versatile approach for rapidly assessing the biochemical and cellular effects of cancer-associated histone mutations.

Identification of mutations affecting dimer exchange

Although some newly identified histone mutations occur at or near sites of post-translational modification on histone tails, as do classical oncohistone mutations, the majority appear in the folded globular domains (Fig. 1a). Relatively few of these globular domain sites are known to be post-translationally modified, raising the question whether these mutations function through mechanisms distinct from those of established oncohistone mutations. We hypothesized that histone core mutations might affect the structural stability of the nucleosome and rates of histone exchange. Therefore, we adapted an H2A/H2B dimer exchange assay28 in which the histone chaperone nuclear assembly protein-1 (Nap1) was used to mediate the exchange of tagged wild-type H2A/H2B dimers into mutant MNs (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b). As Nap1 also serves as an H3/H4 tetramer chaperone, we verified that under our assay conditions, histone tetramer exchange does not occur (Extended Data Fig. 4c). We then applied this approach to our DNA-barcoded MN library, using biotinylated dimers and streptavidin affinity purification to enrich for less stable mutant MNs (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 3). Note that, including biological replicates, this corresponded to over 600 biochemical experiments and utilized only 3 pmol (or 0.3%) of the library. Overall, histone mutations tended to increase dimer exchange compared to their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2b), with mutations in the globular domains exhibiting the most pronounced effects (Fig. 2c). The locations of highly destabilizing mutations within the nucleosome structure revealed a striking convergence at the dimer-tetramer interface between histones H2B and H4, including mutations at H2BD68, F70, E71, E76, and H4D68 and K91 (Fig. 2d, e). Other sites of enhanced exchange included H2AR29 (a histone-DNA contact), H2AE56 (an acidic patch residue), and H3E50, E97, and H4G42 (sites buried within the H3/H4 tetramer). Interestingly, other acidic patch mutations at H2AE61, E91, E92 and H2BE113 did not increase dimer exchange, suggesting a distinct role for the H2AE56 residue in nucleosome stability (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

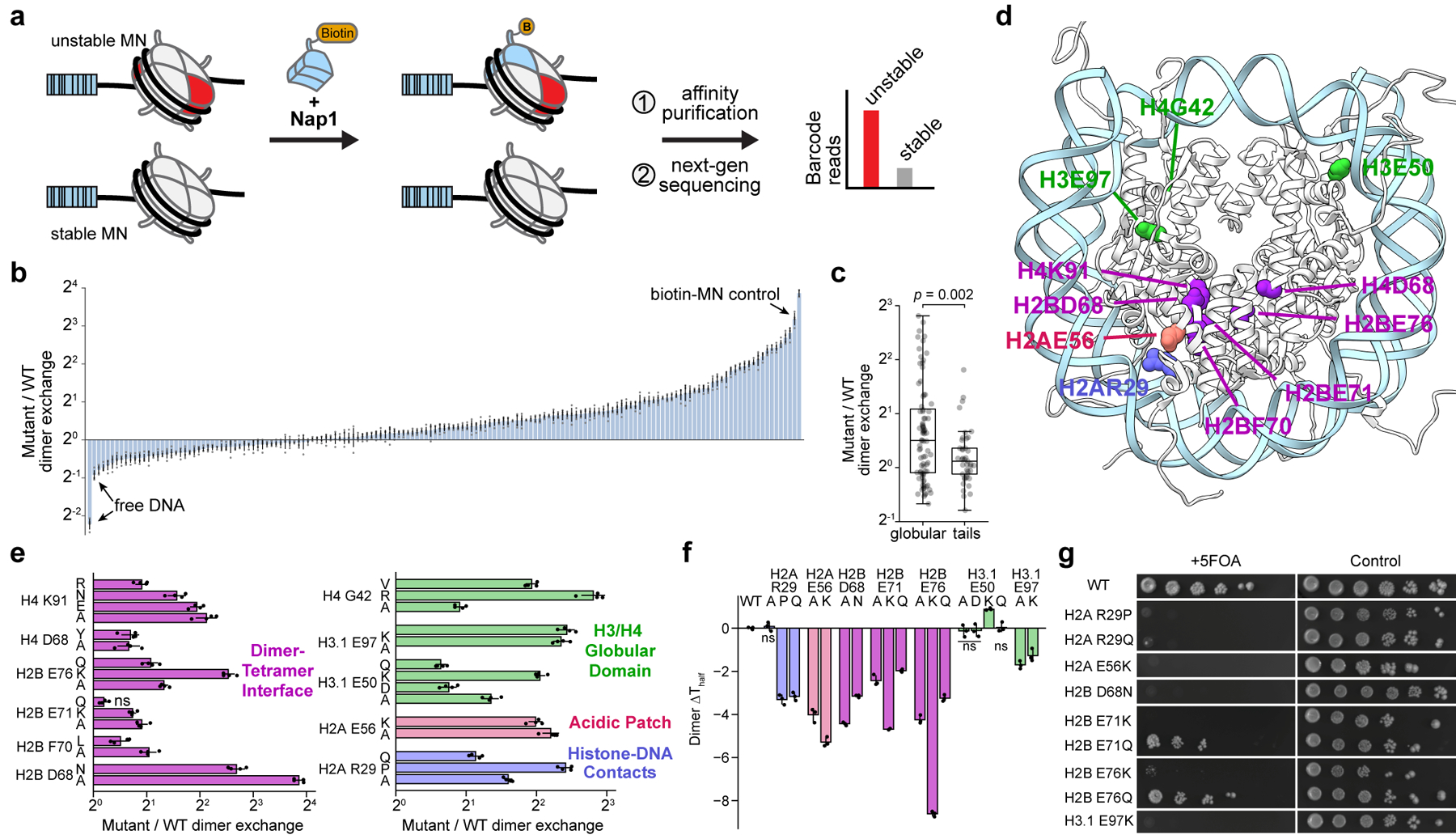

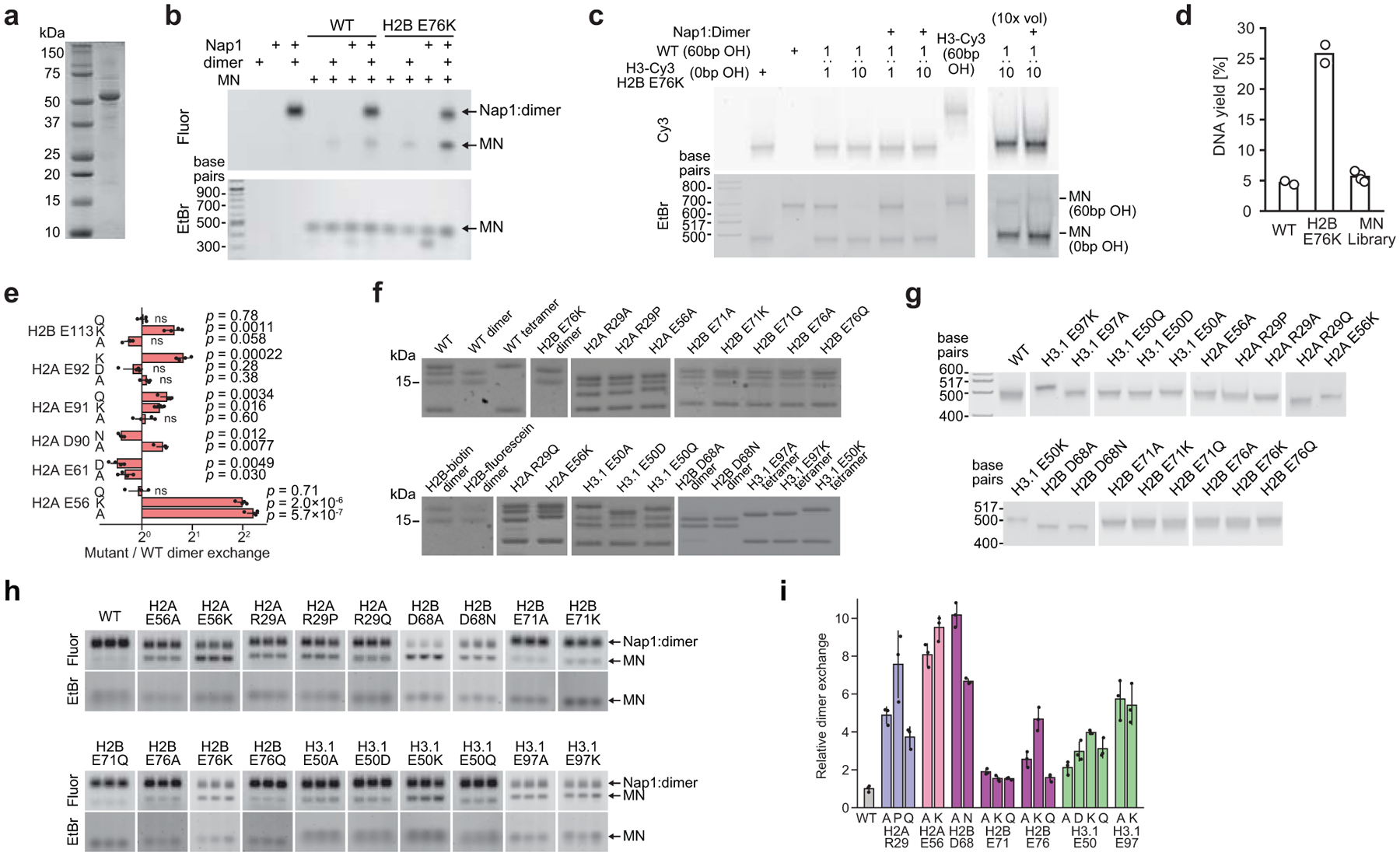

Figure 2 |. An H2A/H2B dimer exchange assay identifies histone mutations that destabilize nucleosomes.

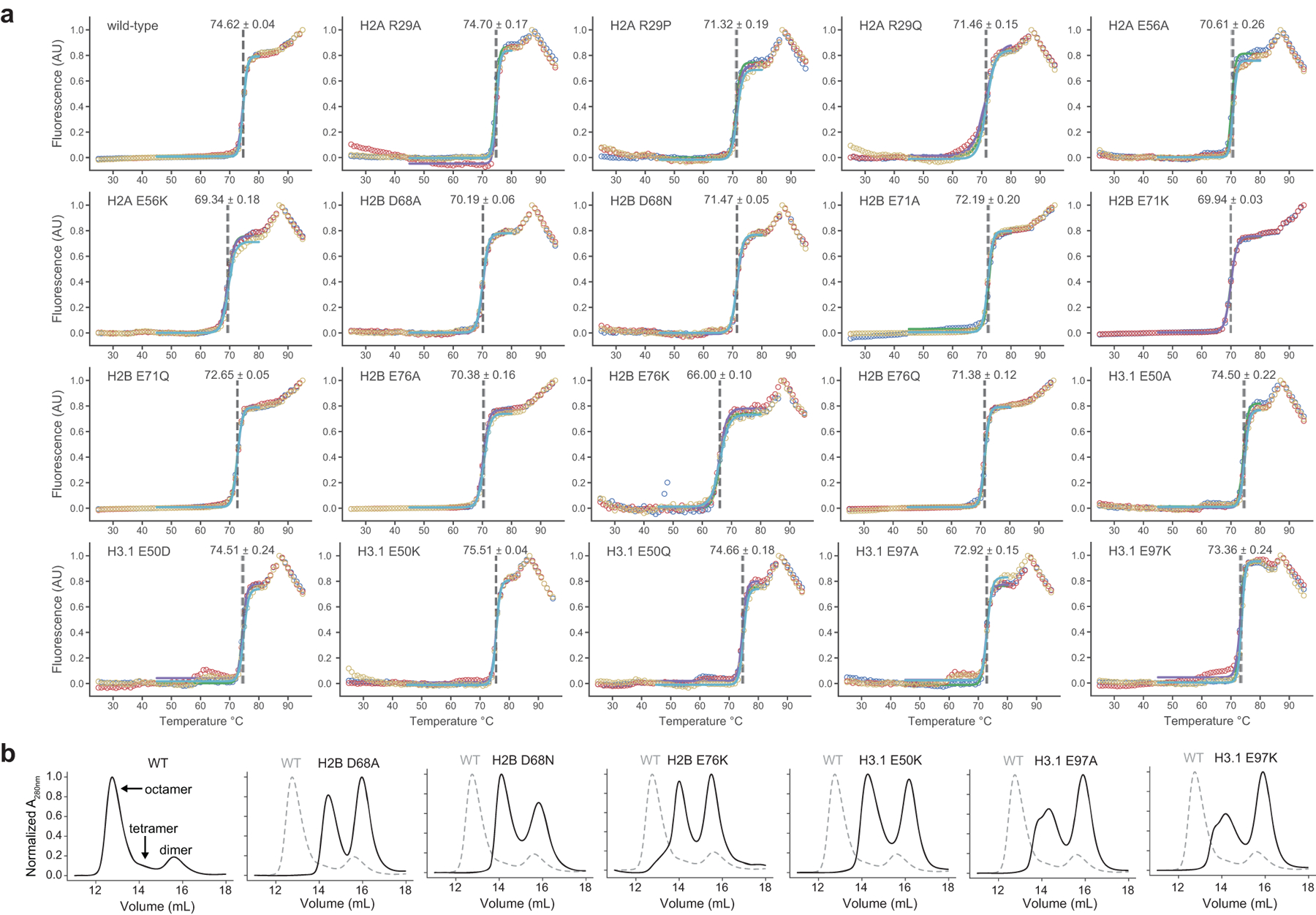

a, Nap1-mediated dimer exchange assay schematic. b, Waterfall plot of results from the H2A/H2B dimer exchange assay on the barcoded MN library. Each bar represents a unique MN library member. Controls are denoted with arrows. Mutant and wild-type nucleosome barcode counts were normalized to their pre-enrichment counts and dimer exchange reported as the ratio of these values. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 biologically independent samples). c, Box-and-whisker plot of average MN dimer exchange values from panel b, grouped by mutation location in either the histone globular (n = 84 distinct MNs) or tail (n = 41 distinct MNs) domains. Box, upper and lower quartiles; center line, median; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range. p-value calculated via a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. d, Locations of dimer exchange-enhancing histone mutant residues shown on the nucleosome structure (PDB 1kx5). e, Dimer exchange data for select nucleosomes from panel b, grouped by nucleosome location and indicated by color (see panel d): dimer-tetramer interface (purple), H3/H4 globular domain (green), acidic patch (red), and histone-DNA contacts (blue). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 biologically independent samples). f, Thermal stability measurements of mutant relative to wild-type nucleosomes. Numbers shown are changes in Thalf values, the temperature at which half of the H2A/H2B dimers are melted off the nucleosome (see methods). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Values from mutant MNs in panels e and f exhibit statistically significant differences relative to wild-type (p < 0.05) in a two-sample, unequal variances t-test, unless otherwise noted. ns, not significant. g, Serial dilutions of humanized yeast with mutant (non-alanine) histones that decreased nucleosome thermal stability.

To validate results from the barcoded library, we prepared individual nucleosome substrates containing histone mutants that showed both increased dimer exchange and high mutational frequency (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 4f, g). All of these MNs were assembled using identical, Widom 601 DNA, thus eliminating any potential sequence-specific effects. Mutations at H2AE56 and R29, H2BD68, E71, and E76, and H3E50 and E97 resulted in increased dimer exchange, as measured by in-gel fluorescence, which corresponded with the respective increases observed in the barcoded MN library experiments (Extended Data Fig. 4h, i). These nucleosomes also exhibited decreased thermal stability, with the exception of those with mutations at H3E50 (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 5a). Notably, histone mutations H2BD68A/N, H2BE76K, H3E50K, and H3E97A/K did not form stable octamer complexes with wild-type histones under standard assembly conditions, providing additional evidence of the perturbative effects of these mutations on nucleosome structure (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Mutants that enhanced dimer exchange and reduced thermal stability in MNs exhibited significant growth defects in humanized yeast (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 3b). Agreement between the biochemical and yeast datasets extended to the level of amino acid identity. For example, charge-swap mutations H2BE71K and H2BE76K did not support yeast growth, whereas charge-neutralizing mutations H2BE71Q and H2BE76Q were better tolerated.

Asymmetric mutant nucleosomes are destabilized

Due to the polygenic nature of mammalian histones, mutations in these genes represent only a subset of the total histone pool11. Stochastic incorporation of histone mutants into mammalian chromatin predominantly gives rise to asymmetric nucleosomes, containing one mutant and one wild-type histone (as opposed to two mutant histones per nucleosome). To determine the destabilizing effects of histone mutations on asymmetric MNs, we developed a method for the synthesis of heterotypic nucleosomes using split inteins (Fig. 3a, see methods for further discussion). To generate heterotypic nucleosomes, mixtures of hexasomes and nucleosomes were produced by under-titrating H2A/H2B dimers relative to H3/H4 tetramers during nucleosome assembly. This approach generates uniformly oriented hexasomes due to the inherent asymmetry of histone-DNA binding strength in the Widom 601 sequence29. Hexasomes were then complemented by the addition of wild-type dimers fused to the N-terminal fragment of the engineered split intein, CfaN30, forming tagged heterotypic nucleosomes (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Tagged MNs were subsequently affinity purified and eluted via on-resin split intein complementation and thiolysis31, tracelessly yielding purified heterotypic nucleosomes. As a proof of concept, we generated asymmetric ubiquitinated H2B MNs, which can be discriminated from their homotypic counterparts by size on both native and denaturing gels (Extended Data Fig. 6b).

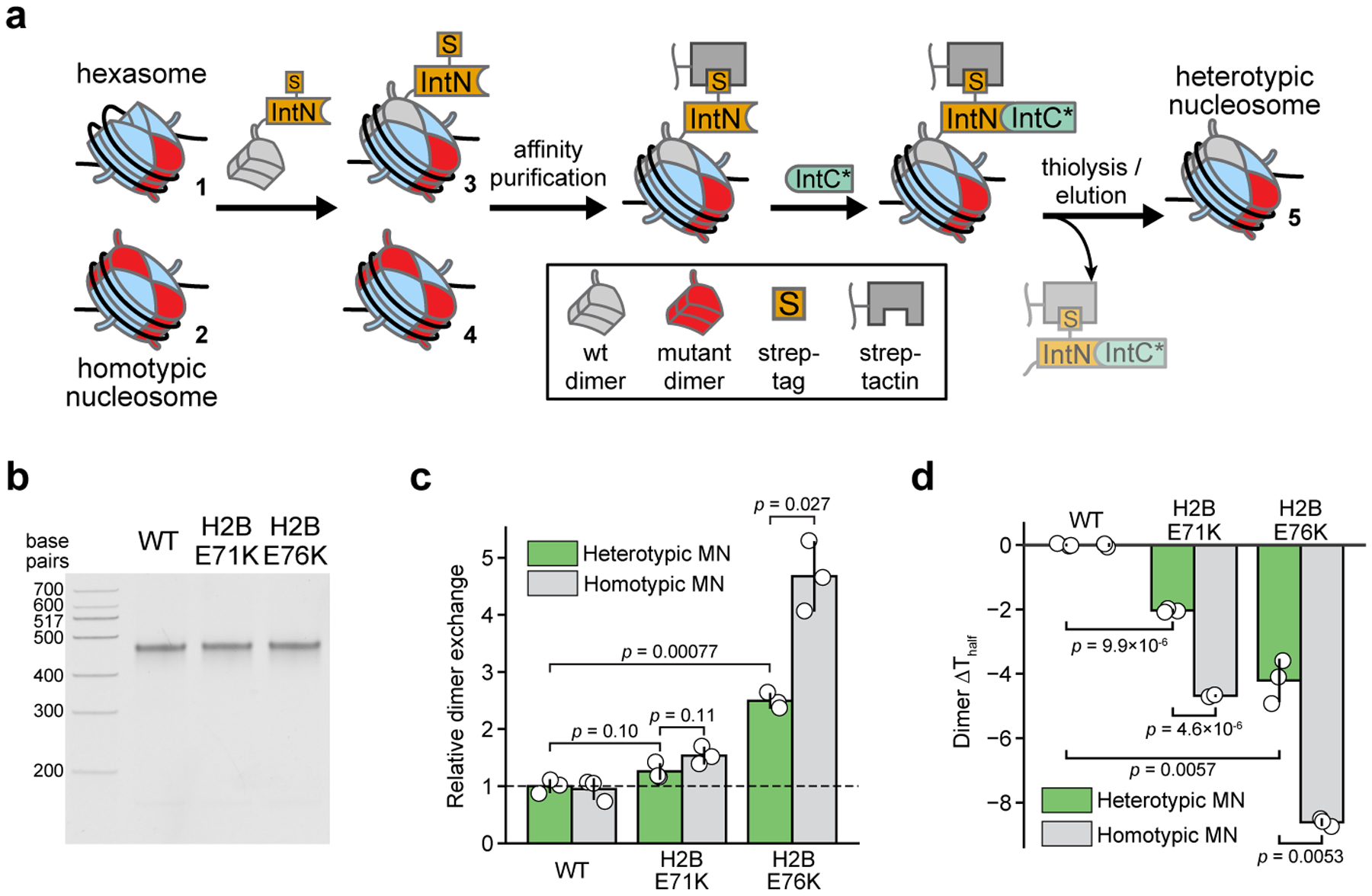

Figure 3 |. Asymmetric mutant H2B nucleosomes are destabilized.

a, Schematic of the streamlined assembly and purification of heterotypic nucleosomes using split inteins (see methods). Mixtures of hexasomes and nucleosomes are treated with H2A/H2B dimers tagged with a split N-intein fragment (IntN), producing asymmetric MNs which are subsequently isolated via affinity purification. Captured MNs are then eluted by on-resin thiolysis using a catalytically dead C-intein fragment (IntC*), yielding tracelessly purified heterotypic MNs. b, Native gel analysis of heterotypic nucleosomes containing cancer-associated histone mutations. The wild-type nucleosome is homotypic but assembled via the method in panel a to serve as a control for the process. c, Nap1-mediated dimer exchange of heterotypic mutant nucleosomes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). d, Thermal stability measurements for heterotypic mutant nucleosomes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Values from heterotypic mutant MNs in panels c and d exhibit statistically significant differences relative to wild-type MNs or homotypic mutant MNs (p < 0.05) in a two-sample, unequal variances t-test, unless otherwise noted.

We then synthesized heterotypic MNs containing nucleosome-destabilizing mutants H2BE71K and H2BE76K (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 6c). Asymmetric mutant nucleosomes showed intermediate (between wild type and homotypic mutant) effects both in terms of Nap1-mediated dimer exchange and thermal stability (Fig. 3c, d, Extended Data Fig. 6d, e). Therefore, the destabilizing effects observed for homotypic nucleosomes (assessed in the barcoded MN and humanized yeast libraries) also occur in a heterotypic context.

Identification of mutations affecting nucleosome sliding

ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling complexes share a common mechanism in which ATP hydrolysis is utilized to translocate (slide) DNA around the nucleosome, facilitating chromatin assembly, access, and editing32. Histone core residues form many key electrostatic interactions with DNA, and these interfaces must be disrupted for efficient nucleosome sliding to occur. We therefore reasoned that histone globular domain mutations might affect nucleosome sliding. To determine the effects of histone mutations on nucleosome remodeling rates, we performed a restriction enzyme accessibility (REA) assay24 on the DNA-barcoded MN library using ACF as a representative ATP-dependent remodeler (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 7a, Supplementary Table 4). All told, this experiment corresponded to over 6500 measurements when factoring in replicates and controls, again highlighting the advantages of the barcoded MN library platform, in particular the ability to multiplex experiments. Analysis of the remodeling data revealed that cancer-associated histone mutations can lead to both increased and decreased rates of ACF remodeling (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 7b). Notably, mutations at sites of histone-DNA contact, including H2AR29, K74, K75, and R77, H2BG53, and H4R45, primarily showed enhanced remodeling rates (Fig. 4c, d). The exception to this trend occurred at H3R83, however, where mutations showed decreased rates of sliding. Consistent with previous results24,33, mutations in the nucleosome acidic patch reduced or completely abolished ACF activity, with the exception of mutations at H2AE56 and H2BE113 which enhanced activity. Likewise, nucleosomes bearing the R17/19A mutations in the basic patch of the H4 tail were poor ACF substrates24,34,35.

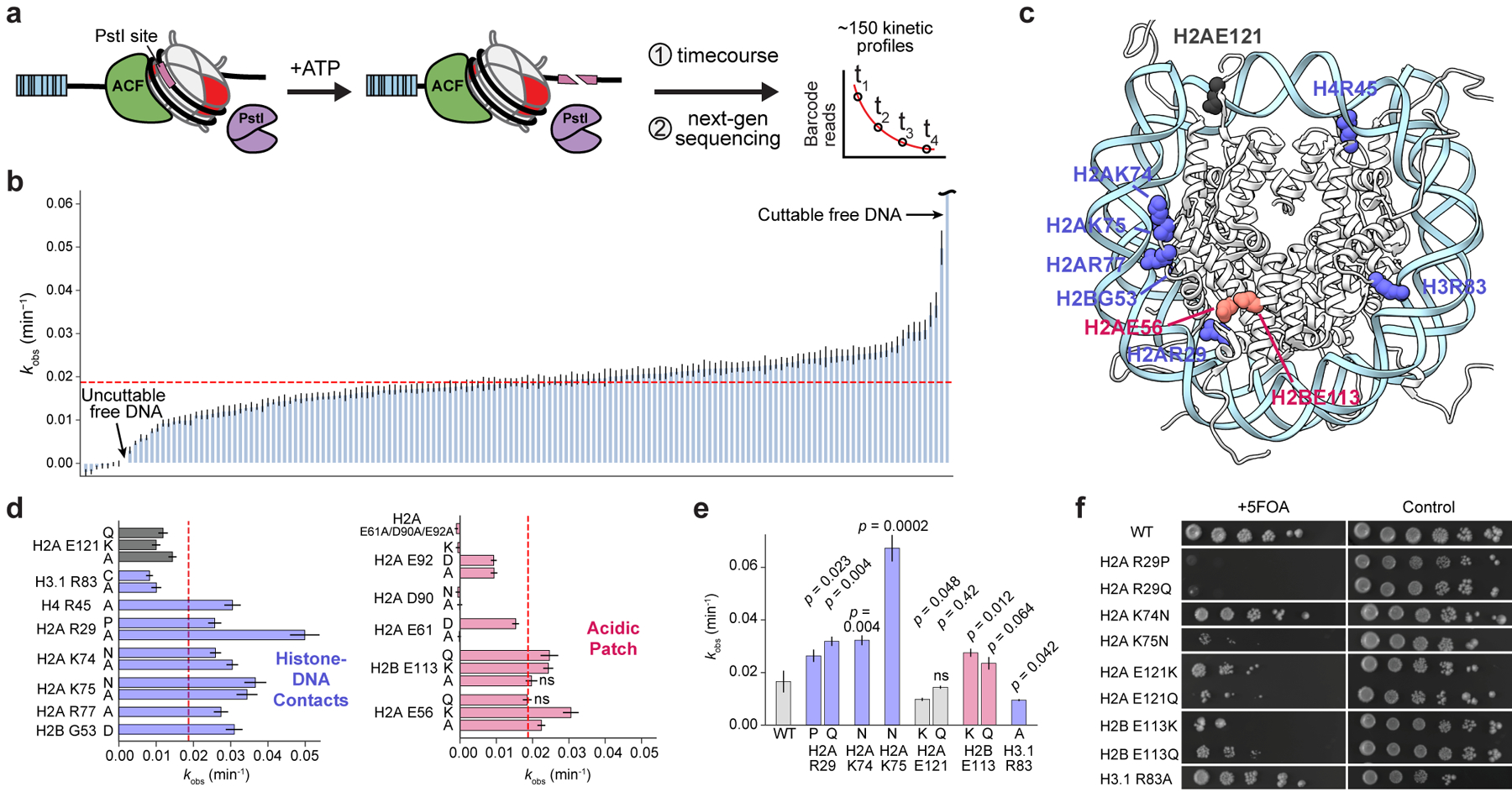

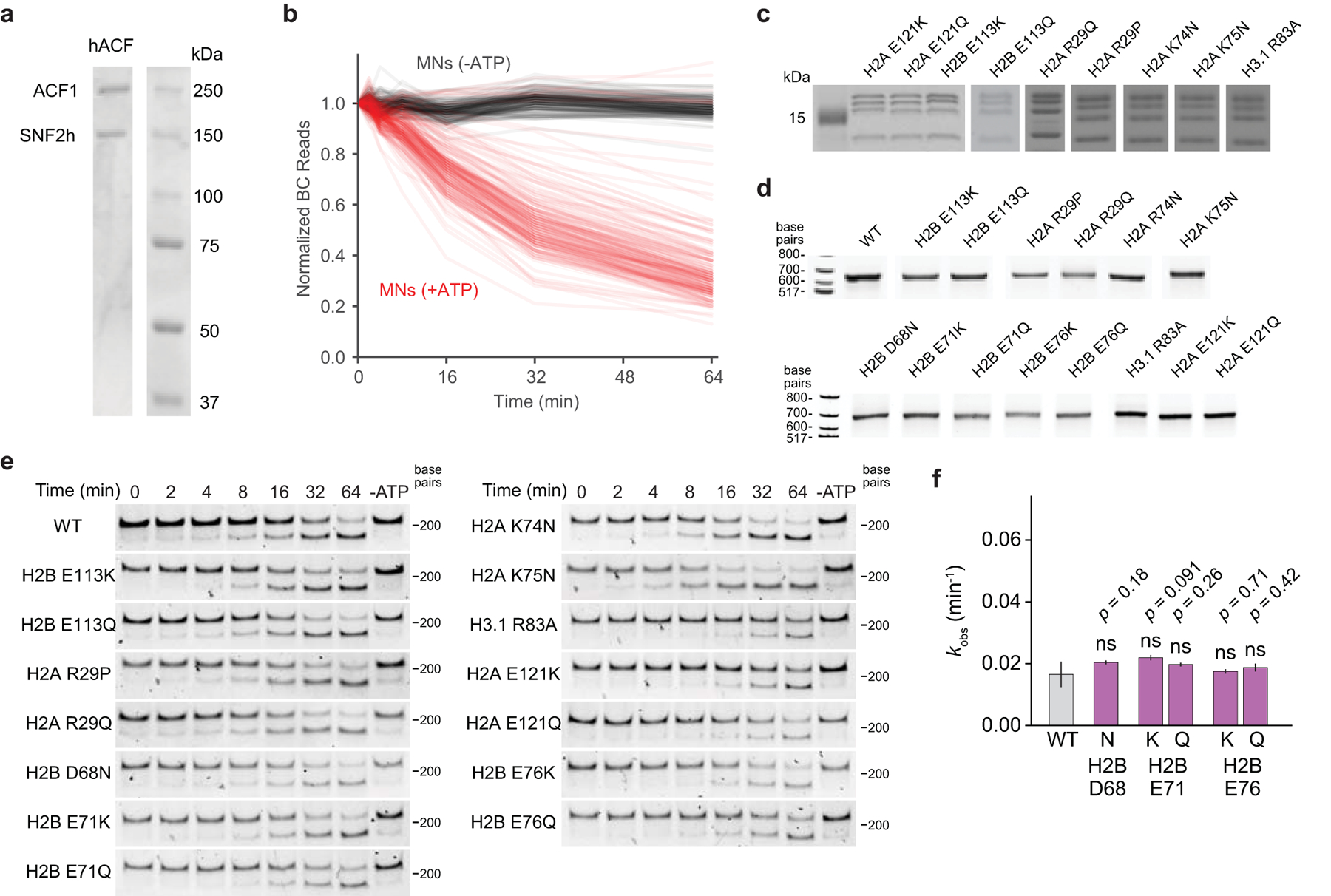

Figure 4 |. A chromatin remodeling assay uncovers histone mutations that affect nucleosome sliding.

a, Schematic of the restriction enzyme accessibility assay used to assess rates of nucleosome sliding by ACF. PstI cutting of DNA on remodeled nucleosomes manifests as fewer barcode reads since truncated DNA is not sequenced. Plots of barcode reads vs. time were modeled as single-phase exponential decays from which observed rate constants were extracted. b, Waterfall plot of observed nucleosome remodeling rates (kobs) for the barcoded MN library. Each bar represents a unique MN library member. Remodeling rates were determined from a collective fit of the time-course data to a single one-phase exponential decay function, yielding kobs values and their corresponding errors. The dotted red line indicates the average remodeling rate for wild-type nucleosomes. Data are presented as the fit kobs parameter ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). c, Locations of mutant histone residues that alter nucleosome sliding depicted on the nucleosome structure (PDB 1kx5). d, Remodeling rates of select mutants from panel b, grouped by color based on nucleosome location (see panel c): histone-DNA contacts (blue) and acidic patch (red). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). e, Observed rate constants for validated mutant nucleosomes. Data are presented as the fit kobs parameter ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Values from mutant MNs in panels d and e exhibit statistically significant differences relative to wild-type (p < 0.05) in a two-sample, unequal variances t-test, unless otherwise noted. ns, not significant. f, Serial dilutions of humanized yeast with mutant histones that altered nucleosome sliding rates.

We validated select histone mutations that increased (H2AR29P/Q, K74N, K75N, and H2BE113K/Q) and decreased (H2AE121K/Q and H3R83A) rates of ACF remodeling via gel-based quantification of REA assay products using individual MN substrates assembled on sequence-identical DNA (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 7c–e). Interestingly, we did not observe significant changes in nucleosome sliding rates for several mutations that had pronounced effects on dimer exchange (Extended Data Fig. 7f), suggesting that not all mutations affect various chromatin remodeling processes alike. Mutations at residues that alter ACF remodeling rates also conferred yeast growth defects, again demonstrating consistency between biochemical and cellular screening platforms (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 3b). Yeast were particularly sensitive to mutations in the nucleosome acidic patch, where 12 of 16 mutations exhibited a no-growth phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Importantly, we and others have recently shown that asymmetric disruption of the nucleosome acidic patch through mutation can lead to dysregulation of chromatin remodeling enzymes33,36.

Mutations alter transcription and impair differentiation

Given the biochemical effects of cancer-associated histone mutations on chromatin remodeling processes in vitro, we hypothesized that these mutations might induce transcriptional changes in cells. As these prominent cancer-associated histone mutations that affect nucleosome stability (H2BE71K/Q and H2BE76K/Q) and nucleosome sliding (H2BE113K/Q) are present in a wide range of cancers19,20, we elected to express them in C3H10T1/2 murine mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs), a robust model system for studying defects in cell fate and cellular differentiation6. This MPC model has been used previously to study the impact of the established oncohistone driver H3K36M in a cellular context and, importantly, results in stable expression of mutants at pathologically relevant levels6 (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis showed that MPCs expressing mutant H2B histones exhibit significant differences in transcriptional profiles from those expressing wild-type H2B (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 8c, Supplementary Table 5). Gene ontology analysis revealed that the H2B mutant cell lines shared several dysregulated pathways involved in cell signaling as well as cell adhesion (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 9, Supplementary Table 6). Notably, upregulated pathways included the PI3K-Akt, Wnt, and Rap1 pathways, which have been broadly implicated in tumorigenesis37–39. Other shared transcriptional differences included upregulation of pathways associated with stem cell pluripotency and cancer-associated proteoglycans, as well as downregulation of genes linked to cell adhesion. Altered expression of select genes from these shared pathways was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Extended Data Fig. 8d). The mutant amino acid identity (i.e. Lys vs. Gln) at a specific residue, however, did engender distinct transcriptional changes, suggesting that these mutant-bearing MPCs, despite sharing some similarly regulated pathways, also differ significantly (Fig. 5c).

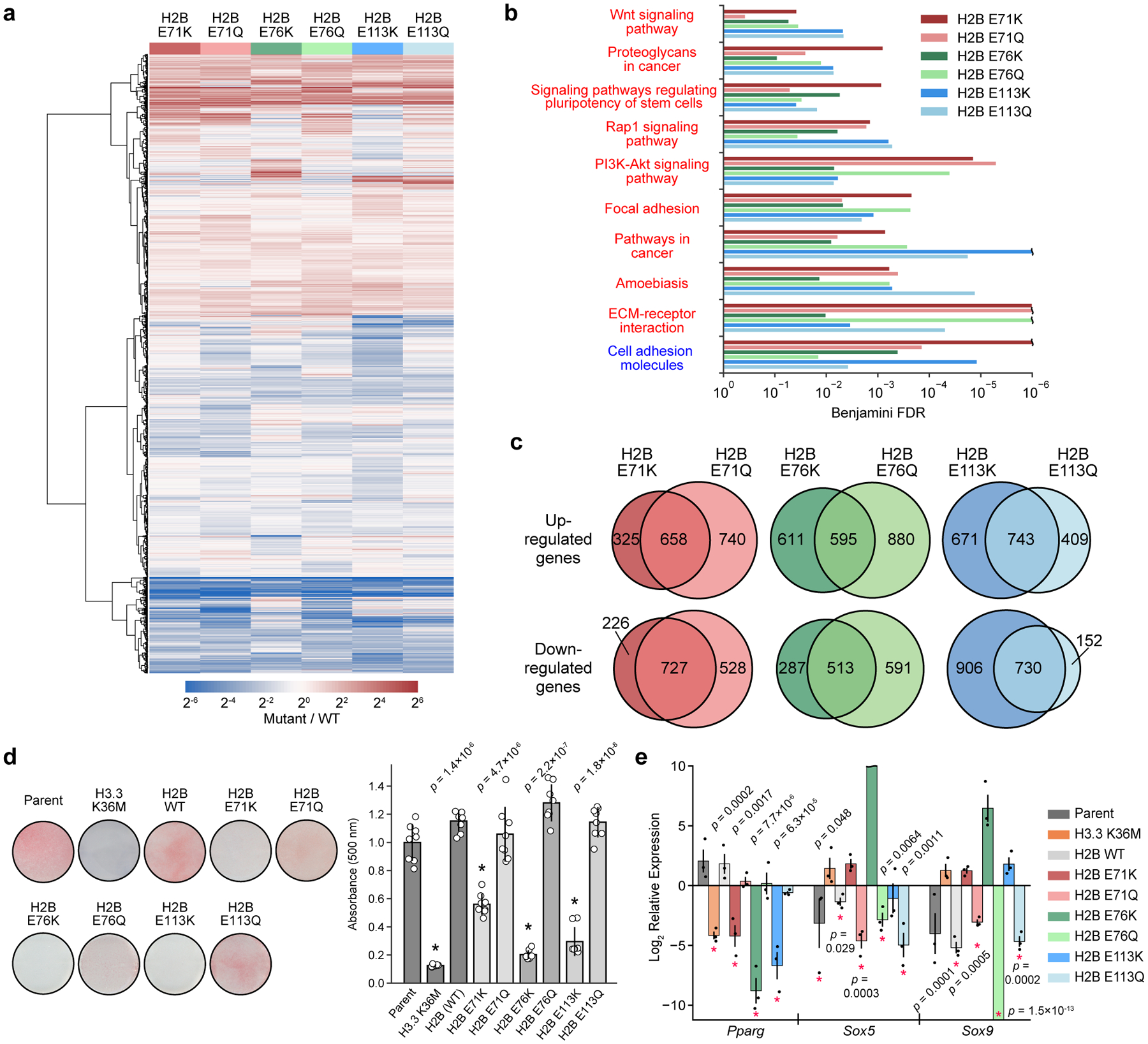

Figure 5 |. Globular domain mutations alter gene expression and impair cell differentiation.

a, Heatmap depicting average differential gene expression in C3H10T1/2 cells stably expressing either wild-type or mutant H2B (n = 3 separately generated cell lines each at distinct passage numbers). b, Gene ontology (GO) analysis showing significantly upregulated (red text) and downregulated (blue text) KEGG pathways for cells expressing mutant histones (n = 3 separately generated cell lines). Pathways significantly affected (Benjamini FDR < 0.05) in at least 4 of the 6 mutants are shown. Expanded GO analyses for individual mutants are shown in Extended Data Fig. 9. c, Venn diagrams comparing significantly upregulated and downregulated genes (FDR < 0.05) for cells expressing Lys and Gln mutations at H2BE71, E76, and E113. d, Mutant and wild-type H2B cell lines were induced to undergo adipocyte differentiation for 7 days. Representative images are shown after Oil Red O staining. The barplot shows the mean ± SD of quantified Oil Red O staining of cell extracts (n = 8 biologically independent samples). An asterisk marks mutant cell lines that caused a significant reduction in staining compared to both the parent line and to cells expressing wild-type H2B (p < 0.05, two-sided unequal variances t-test). e, Expression of master transcriptional regulators at day 4 of adipocyte differentiation as assessed by RT-qPCR. Mutant H2B and H3 values are displayed relative to the wild-type H2B and parent expression levels, respectively, at day 0. Asterisks mark values with significant difference from reference genes at day 0 (p < 0.05, two-sided unequal variances t-test). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 biologically independent samples).

In light of the altered transcriptomes observed in cells expressing mutant histones, specifically the upregulation of genes associated with stem cell pluripotency, we speculated that these cells would exhibit altered cell fates40. Indeed, it has been shown previously that H3K36M inhibits MPC differentiation by derepressing genes that block lineage specificity6,41. Thus, we subjected MPCs expressing H2BE71K/Q, H2BE76K/Q and H2BE113K/Q to analogous adipocyte and chondrocyte differentiation assays. Notably, we observed that charge-swap mutations (Glu to Lys) inhibited MPC differentiation, whereas charge-neutralizing mutations (Glu to Gln) had no effect (Fig. 5d, Extended Data Fig. 8e). Indeed, Glu-to-Lys mutant cell lines showed a significant reduction in the expression of Pparg, a master regulator of adipogenesis, compared to wild-type controls and the corresponding Glu-to-Gln mutant cell lines (Fig. 5e)42. Conversely, genes implicated in the regulation of lineage commitment of MPCs, namely Sox5 and Sox9, were continually expressed in the charge-swap mutant cell lines despite exposure to adipogenic stimuli. Wild-type and charge-neutralizing mutant cells, however, silenced those master regulators during cellular differentiation. These trends are consistent with the greater effects observed for Lys (compared to Gln) mutations in nucleosome thermal stability (H2BE71K and H2BE76K) and nucleosome sliding (H2BE113K) assays (Fig. 2f, 4e), as well as the more detrimental cellular growth phenotypes seen in humanized yeast (H2BE71K, H2BE76K, and H2BE113K) (Fig. 2g, 4f).

Discussion

The sizeable number of mostly uncharacterized histone mutations identified presents a formidable challenge for experimental investigations. Here we present DNA-barcoded MN and humanized yeast libraries that enable facile biochemical and cellular screening of ~150 cancer-associated histone mutations. We used these libraries to determine the effects of histone mutations on the fundamental chromatin remodeling processes of dimer exchange and nucleosome sliding, however, the utility of these resources extends beyond the assays presented herein. Barcoded nucleosome libraries have been used to profile a variety of chromatin processes, including histone acetylation, ADP-ribosylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, effector binding, and ISWI remodeling23,24,43–45. Similarly, the humanized yeast library can, in principle, be used to determine mutation-associated phenotypes beyond growth inhibition, including chromosomal instability, cell cycle inhibitor sensitivity, and DNA damage sensitivity. Furthermore, as a result of the relatively large number of mutations incorporated into these libraries and the broad coverage they provide throughout the tails and globular domains of all four core histones, these libraries also serve as tools for identifying nucleosome structure-activity relationships for a broad set of chromatin effectors, such as histone-modifying enzymes, remodelers, and transcription factors.

This work also presents a new approach for the streamlined, traceless assembly of heterotypic nucleosomes using split inteins. Previously reported methods for generating asymmetric nucleosomes involve laborious, multi-step purification protocols and/or technically challenging protein chemistry methods29,46–48. Our method avoids these potential difficulties and allows for the synthesis of asymmetric nucleosomes with histone mutations or post-translational modifications (Fig. 3a). This approach can be coupled with various genetic and semisynthetic protein production techniques and, since it can be used to synthesize nucleosomes with asymmetric H2A and H2B histones, is complementary to previously established protocols designed for assembling nucleosomes with asymmetrically modified H3 and H4 histones47,48. The need for such methods is imperative as accumulating evidence suggests that breakdown of nucleosome symmetry through heterotypic incorporation of mutant histones (or PTMs) can affect biochemical processes that act on chromatin48–50. Indeed, we and others have recently shown that asymmetric disruption of the nucleosome acidic patch through mutation (including cancer-associated mutations) can lead to dysregulation of chromatin remodeling enzymes33,36. Here we have extended these analyses to mutations that alter nucleosome stability, demonstrating that structurally perturbative dimer-tetramer interface mutants promote dimer exchange and decrease nucleosome thermal stability even in heterotypic contexts.

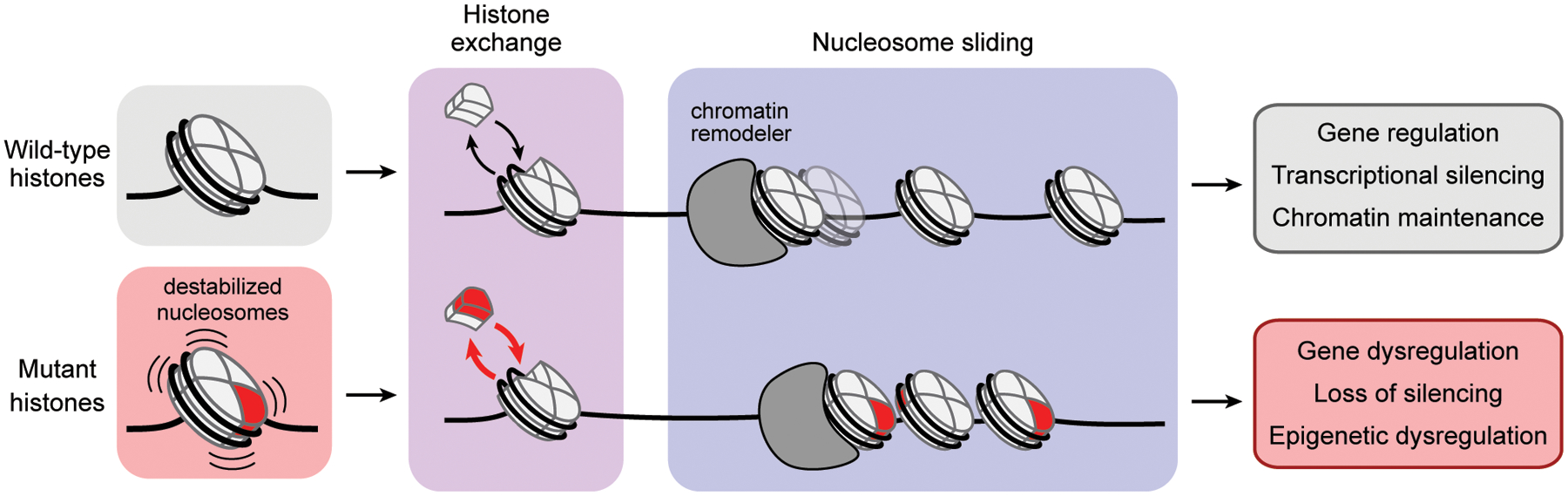

To date, our understanding of the role of histone mutations in cancers has primarily focused on the N-terminal tail of histone H3 either at or near sites of post-translational modification, where mutations inhibit lysine methyltransferase activity and subsequently disrupt local histone PTM installation and maintenance3,4. However, more recent studies have begun to suggest that mutations within the globular, folded domains of histones might also disrupt chromatin state. For example, structural and biochemical studies have shown that H2BE76K and H3.1E97K mutations compromise the structural integrity of the nucleosome, promote colony formation, and, in the case of the former, alter gene expression profiles and chromatin accessibility20,21. Consistent with these previous studies, we found that H2BE76K destabilizes the nucleosomes, even in a heterotypic context, and that this effect extends to several other mutations that map to the dimer-tetramer interface (e.g. those at H2BD68, H2BF70, H2BE71, H4D68, and H4K91) and elsewhere in the nucleosome core (e.g. H2AR29, H2AE56, H4G42, and H3.1E50). Moreover, our work indicates that expression of dimer-tetramer interface and acidic patch mutants in MPCs impacts gene expression profiles, upregulating several cancer-associated pathways, and leads to a profound differentiation blockade. Notably, this phenotype has been previously observed for the well-established H3K36M oncohistone mutant, which, when stably expressed in MPCs, confers tumorigenic potential on these cells as observed using a mouse xenograft tumor model6. Collectively, these studies support a model in which histone core mutations that alter fundamental chromatin remodeling processes can promote human cancers (Fig. 6). These include mutations that disrupt nucleosome-binding interfaces (e.g. the acidic patch) as well as interactions that govern nucleosome structure and stability (e.g. histone-DNA contacts and the H2A/H2B dimer-H3/H4 tetramer interface). The effects of chromatin structure and dynamics on transcriptional potential are well established, and we propose that histone mutations that disrupt the underlying processes that control chromatin organization can cause gene dysregulation and contribute to a diseased state in human cancers. Additionally, the histone mutational landscape converges at critical functional and structural interfaces, raising the possibility that disparate histone mutations may function via shared mechanisms. While it remains to be determined how these mutations engender pathway-specific transcriptional profiles and what effects they have on genome architecture and accessibility, the model and tools developed here will serve to direct and expedite scientific investigations into this newly uncovered oncohistone landscape.

Figure 6 |.

Proposed model of how histone mutations may contribute to cancer development or progression by perturbing fundamental chromatin remodeling processes.

Methods

General lab protocols

Common lab reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. All commercial reagents were used as provided by the manufacturer without further purification. Oligonucleotides used for cloning were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Plasmids and gene constructs were produced using standard cloning and site-directed mutagenesis techniques and were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz). Amino acid derivatives for Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) were purchased from Novabiochem and coupling reagents were purchased from Matrix Innovation. Peptide synthesis was performed either by hand or with a CEM Liberty peptide synthesizer using standard Fmoc SPPS protocols.

Preparative-scale reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed using a Waters 2545 Binary Gradient Module with 2489 UV/Visible Detector with a Vydac C18 preparative column (19 × 250 mm, 10 μm) at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. Semi-preparative RP-HPLC was performed on either an Agilent 1100 Series or an Agilent 1260 Infinity system with a Waters XBridge Peptide BEH C18 OBD column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 4 mL/min at 40 °C. Analytical RP-HPLC was performed on either an Agilent 1100 Series or an Agilent 1260 Infinity system with a Vydac C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Mobile phases for all histone purifications and analyses were 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water (HPLC solvent A) and 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water (HPLC solvent B). Mass spectrometric analysis was performed on a MicrOTOF-Q ESI-Qq-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker).

Protein and DNA gels were imaged with an ImageQuant LAS-4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and densitometry measurements performed using Image Studio Lite (LI-COR Biosciences). Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF Chimera version 1.13.1, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco51. Data analyses and visualization were performed with Python 2.7.10 and the Matplotlib 2.2.3 library.

Selection of histone mutants to include in libraries

We developed a series of filtering criteria to reduce the number of candidate histone mutations to an experimentally tractable set. First, in an effort to distinguish mutations that serve as potential cancer drivers from those that are merely passengers, we focused our analysis on mutations from samples with a tumor mutational burden (TMB) ≤ 10 mutations per megabase. This TMB threshold significantly enriched known oncohistone mutations at H3K27, G34, and K36 above mutational background19. Second, we identified histone mutations that show statistical overrepresentation either when considering the total number of amino acid mutations at a given residue or only when considering mutation of a residue to a specific amino acid (e.g. Lys to Met) (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). Third, we included mutations for which we had a priori hypotheses about their functional repercussions, including H2A/H2B acidic patch mutations, switch-independent (Sin-) mutations, candidate amino acid neomorphs, other Lys to Met mutations, as well as previously identified oncohistone mutations. We also included mutations that exhibit tumor type specificity and mutations at several mutationally silent residues. Finally, we included an Ala mutation at every site in addition to any specific missense mutations that were overrepresented in the dataset. This strategy offered both experimental redundancy as well as the ability to distinguish between loss and gain of function at a given amino acid residue.

Production of recombinant histones

Recombinant human histones were expressed in and purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Standard site-directed mutagenesis techniques were used to generate histone mutant plasmids. E. coli were transformed with histone expression plasmids and grown in LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 2–3 hr at 37 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and washed once with cold PBS (10 mL/L culture). Cell pellets were resuspended in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.6 at 4 °C) (10 mL/L culture) and lysed with a Fisherbrand Model 505 Sonic Dismembrator. Inclusion bodies were isolated by centrifugation at 31,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and washed twice with cold lysis buffer containing 1% (w/v) Triton X-100 (10 mL/L culture; 15 min centrifugations at 31,000 g and 4 °C). Inclusion bodies were washed one final time with lysis buffer (10 mL/L culture) and centrifuged at 31,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Inclusion bodies were resuspended in 15 mL/L culture resuspension buffer (6 M GuHCl, 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.6 at 4°C) and nutated for 3 hr at room temperature. Resuspensions were acidified with 0.1% (v/v) TFA, centrifuged at 31,000 g for 30 min, and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter prior to purification. Wild-type histones were purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative scale, and mutant histones were purified on a semi-preparative scale. Purified histones were characterized by analytical RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 1).

H2Aub and H2Bub synthesis

Production of α-thioesters for expressed protein ligation

Synthesis of H2AK119ub(G76A) and H2BK120ub(G76A) was carried out using the general expressed protein ligation strategy that has been described previously23. An α-thioester corresponding to the N-terminal portion of H2A (residues 1–112) was generated by thiolysis of the corresponding histone-intein fusion construct containing H2A(1–112)-GyrA-7xHis. Note that the histone amino acid numbering convention is used which excludes the initiator methionine. After a standard purification with HisPur™ Ni-NTA Resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), eluted protein was refolded by stepwise dialysis from 6 M to 0.5 M GuHCl. Thiolysis was initiated by adding sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA, Sigma-Aldrich) to a concentration of 0.2 M. His-tagged intein was then removed by a reverse Ni-NTA column, and the H2A(1–112)-MES thioester was purified by preparative-scale RP-HPLC. Protein purity was confirmed by analytical HPLC and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 2a), and protein was subsequently lyophilized and stored at −80 °C until use. Thioesters containing the N-terminal portion of H2B (residues 1–116) and ubiquitin (residues 1–75) were produced analogously (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

H2A K119Ub(G76A)

Ubiquitinated H2A was assembled as previously described23 by semi-synthesis from three pieces: recombinant truncated H2A (residues 1–112) containing an α-thioester, a synthetic C-terminal H2A peptide (residues 113–129) with alanine 113 replaced by a cysteine protected as a thiazolidine derivative and a cysteine residue conjugated to the ԑ-amino group of lysine 119 through an isopeptide bond, and a recombinant truncated ubiquitin (residues 1–75) containing an α-thioester. The H2A peptide was synthesized using automated Fmoc SPPS. The ԑ-amino group of lysine 119 was protected with an orthogonal alloc group, which allowed for the selective coupling of cysteine to this side chain, forming an isopeptide linkage. The N-terminal cysteine residue was protected as a thiazolidine derivative to ensure selectivity in the first ligation. The ubiquitinated H2A peptide was generated via expressed protein ligation with Ubiquitin(1–75)-MES. The thiazolidine group was deprotected using methoxylamine under acidic conditions, and a second expressed protein ligation was used to generate full-length ubiquitinated H2A. Radical-initiated desulfurization of the two cysteine residues yielded the final product, which was purified by semi-preparative HPLC and characterized by analytical RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 1).

H2B K120Ub(G76A)

Ubiquitinated H2B was assembled as previously described23 by semi-synthesis from three pieces: a recombinant truncated H2B (residues 1–116) containing an α-thioester, a synthetic C-terminal H2B peptide (residues 117–125) with alanine 117 replaced by cysteine protected as a thiazolidine derivative and a cysteine residue conjugated to the ԑ-amino group of lysine 120 through an isopeptide bond, and a recombinant truncated ubiquitin (residues 1–75) containing an α-thioester. Semi-synthesis was carried out following the protocols as described for H2A K119ub(G76A). Purified ubiquitinated H2B was characterized by analytical RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 1).

H2B-biotin, H2B-fluorescein, and H3-Cy3 synthesis

H2B T115C and H3 G33C were expressed and purified as described previously for mutant histones. Maleimide reactions were performed with EZ-Link Maleimide-Peg2-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Fluorescein-5-Maleimide (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Cy3-Maleimide (Lumiprobe) to produce the corresponding H2B-biotin, H2B-fluorescein, and H3-Cy3 proteins, respectively. Lyophilized protein was dissolved in 6 M GuHCl, 20 mM Tris, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.2 at a concentration of 3 mg/mL. A 10-fold molar excess of maleimide reagent was then added to the protein and allowed to react for 5 hr at 4 °C. Reactions were quenched with DTT and subsequently purified by semi-preparative RP-HPLC. Purified protein was characterized by mass spectrometry and analytical RP-HPLC (Supplementary Fig. 1, 2b, 2d).

Assembly of histone octamers, tetramers, and dimers

Histone octamers used for assembly of the nucleosome library were generated as described previously24. To assemble histone octamers for all other experiments, purified histones were dissolved in histone unfolding buffer as described above and combined in ratios of 1:1:0.91:0.91 of wild-type or mutant H2A:H2B:H3:H4, such that all mutant octamers were composed of a single mutant histone mixed with the remaining wild-type histones. For histone tetramer assembly, histones H3 and H4 (or mutants) were mixed in equimolar quantities, and for histone dimer assembly, histones H2A and H2B (or mutants) were mixed in equimolar quantities. The total protein (histone) concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/mL and histone mixtures were placed in Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (3.5 kDa MWCO, Themo Fisher Scientific) and dialyzed 3 × 4 L against octamer refolding buffer as described above. Samples were then concentrated to volumes <500 μL in Vivaspin 500 centrifugal concentrators (10 kDa MWCO, Sartorius) and injected onto a gel filtration column (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) pre-equilibrated with octamer refolding buffer. Fractions containing octamer (or tetramer or dimer), as assessed by the FPLC UV chromatogram and SDS-PAGE analysis, were pooled and concentrated (Vivaspin 500 concentrators). Glycerol was added to a final concentration of 50% (v/v) and concentrations determined by UV spectroscopy at 280 nm. Octamers, tetramers, and dimers were stored at −20 °C until use in nucleosome assemblies.

DNA preparation

Barcoded 601 (BC-601) DNA

Unique nucleosome identifier barcodes were added via PCR. First, the linear DNA template was generated by amplifying off of a KS BlueWhite screening vector bearing the 147-bp 601 sequence with a PstI site24. Primers were designed to amplify the 601 sequence with a 9-bp 5’ overhang and a 15-bp 3’ overhang generated from the surrounding vector.

Forward: 5’-CACCGCGTGACAGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-CCTAGGTCTCTGATGCTGG-3’

171-bp DNA fragment generated (bold, 601 sequence, bold underlined, PstI site):

5’-CACCGCGTGACAGGATGTATATATCTGACACGTGCCTGGAGACTAGGGAGTAATCCCCTTGGCGGTTAAAACGCGGGGGACAGCGCGTACGTGCGTTTAAGCGGTGCTAGAGCTGTCTACGACCAATTGAGCGGCTGCAGCACCGGGATTCTCCAGCATCAGAGACCTAGG-3’

The resultant PCR product was subjected to DpnI (New England Biolabs) digest and purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). This linear DNA fragment (above) was then used as a template for all PCR reactions for the addition of unique barcodes. Primers were designed to amplify this fragment and add on a unique hexanucleotide nucleosome identifier barcode, yielding DNA with a 45-bp 5’ overhang (inclusive of the 6-bp barcode) and a 15-bp 3’ overhang. Hexanucleotide MN identifier barcode sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Forward (underlined, unique barcode):

5’-TACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGCGTNNNNNNCACCGCGTGACAGG-3’

Reverse (common to all reactions): 5’-ATCCAAAAAACTGTGCCGCAGTCGG-3’

207-bp barcoded DNA sequence generated (bold, 601 sequence; bold underlined, PstI site; underlined, unique hexanucleotide nucleosome identifier barcode):

5’-TACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGCGTNNNNNNCACCGCGTGACAGGATGTATATATCTGACACGTGCCTGGAGACTAGGGAGTAATCCCCTTGGCGGTTAAAACGCGGGGGACAGCGCGTACGTGCGTTTAAGCGGTGCTAGAGCTGTCTACGACCAATTGAGCGGCTGCAGCACCGGGATTCTCCAGCATCAGAGACCTAGG-3’

In total, 157 unique DNA sequences (of the above general format) were produced. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). DNA was quantified by UV spectroscopy at 260 nm and stored at −20 °C.

Biotinylated MMTV ‘buffer’ DNA

Biotinylated MMTV ‘buffer’ DNA was prepared as previously described24.

207-bp 601 DNA

The 207-bp, 601-containing DNA used in gel-based (non-library) ACF remodeling assays on individual nucleosomes was generated via PCR using the 171-bp DNA template described above and the following primers:

Forward:

5’-TACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGCGTGTCAGTCACCGCGTGACAGG-3’

Reverse: 5’-CCTAGGTCTCTGATGCTGG-3’

207-bp DNA sequence generated (bold, 601 sequence; bold underlined, PstI site):

5’-TACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGCGTGTCAGTCACCGCGTGACAGGATGTATATATCTGACACGTGCCTGGAGACTAGGGAGTAATCCCCTTGGCGGTTAAAACGCGGGGGACAGCGCGTACGTGCGTTTAAGCGGTGCTAGAGCTGTCTACGACCAATTGAGCGGCTGCAGCACCGGGATTCTCCAGCATCAGAGACCTAGG-3’

147-bp 601 DNA

DNA containing the 147 bp 601 positioning sequence was produced and purified as described previously with some modifications52. E. coli DH5α cells were grown with a pUC19 vector containing 32 × 601 sites separated by EcoRV restriction sites53, pelleted, and subjected to alkaline lysis. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation, filtered, and isopropanol was added to 0.52 volumes to precipitate plasmid DNA. Precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 5000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, resuspended in TE 10/50 buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), and treated with RNase A (Qiagen) at 30 μg/mL overnight at 37 °C. DNA was isolated via three sequential phenol:chloroform:isoamyl-alcohol (25:24:1) extractions, and then precipitated by addition of 0.2 volumes of 4 M NaCl and 0.4 volumes of 40% (w/v) PEG 6000 and incubation at 4 °C for 30 min. DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and dissolved in TE 10/0.1 buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). PEG was removed by two chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extractions, and DNA was precipitated by addition of 0.1 volumes of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volumes of cold absolute ethanol. DNA was pelleted by centrifugation and dissolved in TE 10/0.1. Plasmid DNA was then digested overnight with EcoRV-HF (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C. Digested 601 fragments were purified by PEG precipitation at a PEG 6000 concentration of 9% (v/v, a percent empirically determined by titration to separate digested 601 fragments from plasmid vector). PEG was removed by two chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extractions followed by cold ethanol precipitation, as performed previously, to give purified 601 DNA.

Nucleosome reconstitution for the MN library

Nucleosomes were reconstituted as previously described24 with the following modification. Following peristaltic pump addition of nucleosome assembly end buffer, samples were removed from dialysis devices, placed into microcentrifuge tubes, and incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min to promote uniform positioning of octamers on the DNA. All 155 unique nucleosomes were prepared in this fashion with the exception of the nucleosome containing H2B-biotin, which was prepared as described in the following section. Nucleosome quality was assessed by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5% acrylamide gel, 0.5x TBE, 190 V, 35 min) followed by SYBR™ Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Invitrogen) staining. Nucleosome bands appeared to migrate around 600–700 bp, depending on the nucleosome variant (Extended Data Fig. 2b). To prepare the final nucleosome library, normalized amounts (9 pmol) of each nucleosome were combined and concentrated using a Vivaspin 500 centrifugal concentrator (10 kDa MWCO, Sartorius). For storage, PMSF and glycerol were added to final concentrations of 0.5 mM and 20% (v/v), respectively. The final MN library was analyzed by native gel electrophoresis as described above and determined to have a concentration of approximately 1.2 μM by UV spectroscopy (260 nm). Library aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

MN formation for follow-up assays

Purified octamers were combined with 601 DNA (either without overhangs in dimer exchange and thermal stability experiments or with 45/15-bp overhangs for remodeling experiments) in empirically determined ratios in octamer refolding buffer. In cases where a histone mutation prevented octamer formation, H2A/H2B dimers and H3/H4 tetramers were used in stoichiometric ratios (2:1). Mixtures were placed in Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis devices (3.5 kDa MWCO, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and dialyzed against 200 mL nucleosome assembly start buffer for 1 hr at 4 °C. 330 mL nucleosome assembly end buffer was then added via peristaltic pump at a rate of 1 mL/min, after which samples were removed to tubes and heated at 37 °C for 30 min to promote repositioning, as described above. Samples were then placed on ice for 10 min and spun down for 10 min at 17,000 g and 4 °C. Supernatants were placed back into dialysis devices and dialyzed 2 × 200 mL against nucleosome assembly end buffer (first dialysis for 4 hr, second dialysis overnight) at 4 °C. Samples were then removed to microcentrifuge tubes, centrifuged at 17,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove any precipitate, and final supernatants transferred to fresh tubes. Nucleosomes were quantified by UV spectroscopy (260 nm) and stored at 4 °C. Nucleosome quality was assessed by native gel electrophoresis as described above.

Multiplex barcode and Illumina adaptor addition

Approximately 10 pg DNA from each purified experimental sample from either dimer exchange or remodeling assays on the nucleosome library (described in the corresponding sections below) were amplified using the following primers:

Forward: 5’-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAG-3’

Reverse (XXXXXX, unique hexanucleotide multiplexing barcode):

5’-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATXXXXXXCCTAGGTCTCTGATGCTGGAGA-3’

Hexanucleotide multiplexing barcodes used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 7. Full-length (un-cut) DNA from each experiment was amplified using a Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Kit (New England Biolabs) (0.2 mM dNTPs, 10 pg DNA, 0.5 μM each primer, 0.50 μL polymerase, 50 μL total reaction volume) with the above primers and the following amplification conditions: step 1: 50 °C for 2 min; step 2: 95 °C for 2 min; step 3: 95 °C for 15 sec; step 4: 60 °C for 1 min. Steps 3–4 were repeated for a total of 12 cycles. To ensure reactions remained in the exponential phase, thus preserving the relative abundances of DNA fragments, qPCR analysis was performed using 10 pg of select library experimental samples and PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix reagent (Applied Biosystems) with detection on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Identical conditions were used as described above and a mean Ct value of 13.8 was determined (compare to 12 cycles used for amplification of DNA prior to Illumina sequencing). The following is the general amplicon sequence that was generated to be compatible with Illumina sequencing (bold, 601 sequence; bold underlined, PstI site; NNNNNN, unique hexanucleotide nucleosome identifier barcode; XXXXXX, unique hexanucleotide multiplexing barcode):

5’-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGCGTNNNNNNCACCGCGTGACAGGATGTATATATCTGACACGTGCCTGGAGACTAGGGAGTAATCCCCTTGGCGGTTAAAACGCGGGGGACAGCGCGTACGTGCGTTTAAGCGGTGCTAGAGCTGTCTACGACCAATTGAGCGGCTGCAGCACCGGGATTCTCCAGCATCAGAGACCTAGGXXXXXXTCAGATCTGGTACCCAGCTTTTGT-3’

The full forward adaptor sequence is 5’ of the nucleosome identifier barcode (NNNNNN), and the full reverse adaptor sequence is 3’ of the multiplexing barcode (XXXXXX). For each sample, correct amplicon size (242 bp) was verified by gel electrophoresis and staining with SYBR™ Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Invitrogen). Approximately equal amounts of DNA samples with multiplexing barcodes were pooled and purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). After purification, samples were subjected to high-throughput DNA sequencing as described in the following section.

Illumina sequencing

Single-read sequencing of barcoded DNA libraries (starting from the forward adaptor and covering the unique nucleosome identifier barcode) was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument with a read length of 185 bp. Due to the substantial sequence homogeneity present in all library samples, DNA sequencing libraries were diluted with a PhiX control library to enable sequencing. Sequencing reads from library experiments were imported into Galaxy (Princeton University installation) and separate FASTQ files generated based on multiplexing barcodes using the Galaxy Barcode Splitter tool. FASTQ files were exported from Galaxy, and the number of MN barcode reads were counted in each experiment (i.e. each FASTQ file) using a custom R script24. The resulting output provided read counts for each individual MN in each multiplexed experiment.

Assessment of MN library assembly using next-generation sequencing

MN fidelity in the final, assembled MN library was determined using a modified version of the restriction enzyme accessibility assay. This assay, described in the ACF remodeling assays section below, enables determination of rates of MN sliding based on liberation of a PstI restriction site embedded in the nucleosome 601 positioning sequence. The restriction enzyme digestion employed in this assay can also be used to quantify the fraction of disassembled nucleosomes for each individual MN in the library. Aliquots of the DNA-barcoded MN library were treated with or without 2 U/μL PstI-HF (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 64 min. Barcoded DNA was amplified and prepared for and subjected to next-generation sequencing as described above. MN barcode read counts were first normalized among samples to the ‘uncuttable’ (PstI site absent) non-nucleosomal DNA barcode read counts. The ‘cuttable’ (PstI site present) non-nucleosomal DNA barcode served as a positive control for PstI digestion. These data confirmed that MNs in the library were well assembled (98 ± 5%) (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

Assessment of MN library stability

Nucleosomes were assembled as described above for the nucleosome library. H2BE76K-containing nucleosomes were assembled on 207-bp DNA. H2B-fluorescein-containing nucleosomes were assembled on 192-bp DNA. This difference in DNA length (207-bp vs. 192-bp) enabled differentiation of these nucleosome species by native gel polyacrylamide electrophoresis (Extended Data Fig. 2e). To assess whether barcodes would exchange between nucleosomes or if nucleosomes would fall apart under standard assay (37 °C) or stringent (50 °C) conditions, nucleosomes were incubated either alone, in 1:1, or in 1:10 ratios at concentrations similar to what might be used in a library assay for 1 hr at the indicated temperatures. Following incubation, samples were analyzed by native gel polyacrylamide electrophoresis along with MNs containing H2B-fluorescein generated on 207-bp DNA as a positive control for exchange. Neither barcode exchange nor denaturation of nucleosomes was observed (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

Humanized yeast library

The yDT51 yeast strain27 was used for the development of the humanized yeast library. yDT51, which contain a URA3 plasmid bearing yeast histones (pDT105), were transformed with an ‘8-swap’ human histones TRP plasmid (pDT130) containing either wild-type or mutant histones. Standard site-directed mutagenesis techniques were used to generate histone mutant plasmids, and transformations were accomplished using a lithium acetate and DMSO approach as described previously54. Transformations were plated on SC-URA-TRP and individual colonies isolated after four days. Liquid SC-URA-TRP cultures were then grown overnight. Cultures were diluted and allowed to double twice to mid/late log phase, and then 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on SC-URA-TRP + 5-FOA plates. Plates were imaged 6–7 days after spotting using an ImageQuant LAS-4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Images shown (Fig. 2g, 4f, and Extended Data Fig. 3b) are representative of two separate transformations (biological replicates), each performed in technical duplicate. All histone mutants included in the humanized yeast library, along with their phenotypes, are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Nap1 dimer exchange assays

The mammalian Nap1 protein (Mus musculus, NP_056596.1) was expressed and purified as described previously55. Nap1-mediated H2A/H2B dimer exchange assays were performed with fluorescein-labeled dimers for in-gel fluorescence experiments and with biotinylated dimers for MN library experiments. Assays were carried out at a MN concentration of 50–100 nM in 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5. Nap1, H2A/H2B dimers, and MN substrates ratios were fixed at 50:5:1 for all assays. Prior to addition to the MN substrates, Nap1 and H2A/H2B dimers were first co-incubated at 4 °C for 1 hr to allow for complex formation. Dimer exchange assays were initiated by addition of complexed Nap1 and H2A/H2B dimers to MN substrates and samples incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr.

For in-gel fluorescence analysis of dimer exchange, an experimental sample volume corresponding to 0.5 pmol of MN was immediately separated on 2% UltraPure™ Agarose (Invitrogen) native gels. Fluorescence from fluorescein-labeled H2A/H2B dimers was measured using a Typhoon FLA 9500 biomolecular imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Native gels were then stained with ethidium bromide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 hr to detect MN substrates and densitometry measurements determined as described under general lab protocols.

Nap1 dimer exchange assays on the MN library were performed in quadruplicate, with samples collected both before and after streptavidin affinity purification for Illumina sequencing (8 samples total). Barcoded DNA reads pre- and post-enrichment were used to control and normalize barcode counts intra-sample, allowing for robust calculation of barcode enrichment (indicative of H2A/H2B dimer exchange). Specifically, 2% of each Nap1 dimer exchange assay sample was quenched into 500 μL Qiagen PB buffer and barcoded DNA was later purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). The remainder of the samples were incubated with magnetic streptavidin resin (Dynabeads™ MyOne™ Streptavidin T1, Invitrogen) and allowed to bind for 1 hr at 4 °C. The resin was then washed three times with 10x volume (relative to resin slurry volume) MN wash buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) IPEGAL CA-630, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.5). These wash conditions effectively removed non-specific MN-resin interactions without disrupting biotin-captured MNs. Affinity purified nucleosomes were eluted with 5x volume elution buffer (100 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 10 mM BME, 1/1000 (v/v) Proteinase K (New England Biolabs), pH 7.5) at 50 °C for 1 hr at 750 rpm in a thermomixer (Eppendorf). DNA was then purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and prepared as described for Illumina sequencing. Barcode reads were first normalized among samples by the uncuttable, non-nucleosomal DNA standard. Relative enrichment values were calculated for each of the four experimental replicates by dividing MN barcode reads in post-enrichment samples by their corresponding values before streptavidin enrichment. Enrichment values were then divided by the average value of the five wild-type MN controls to give enrichment measurements of mutant MNs as a fold-change relative to wild-type. Nap1 dimer exchange values were reported as the average of these values (with standard deviations) from the four experimental replicates. Raw read counts and subsequent calculations can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Assays to determine whether H3/H4 tetramers swap between nucleosomes during Nap1 dimer exchange assays were performed using similar conditions with the following modifications. Mixtures of wild-type MNs and MNs containing H2BE76K and a fluorescently-labeled H3 (H3-Cy3) were subjected to the Nap1 dimer exchange assay at either a 1:1 or 1:10 ratio. Total MN concentration was fixed at 100 nM in all assays. Samples were separated on a 5% TBE native gel and Cy3 and ethidium bromide fluorescence were measured by a Typhoon FLA 9500 biomolecular imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Thermal stability assays

Nucleosome stability was measured using the SYPRO Orange (Sigma-Aldrich) thermal stability assay56. Nucleosomes were assembled with 147 bp 601 DNA and stored in 10 mM TEK (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for less than a week prior to use. SYPRO Orange was supplied as a 5000x concentrated solution from the manufacturer and was used at a final concentration of 5x in the assay. Assays were performed in a 10 μL reaction volume in 10 mM TEK with a MN concentration of 0.5–1 μM and SYPRO Orange concentration of 5x. Samples were analyzed in triplicate in 384-well plates in a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Thalf values were calculated by fitting fluorescence measurements at temperatures between 45 and 83 °C, inclusive, to a standard sigmoid function and calculating the inflection point. Thalf values statistics were reported as the average and standard deviation from three experimental replicates, each fit independently. Fits were performed in Python 2.7.10 using the optimize.curve_fit function in the SciPy library (0.15.1).

ACF remodeling assays

The human ACF complex was expressed and purified from Sf9 cells as previously described24. All remodeling assays were conducted using a restriction enzyme accessibility (REA)-based strategy and performed similarly to those previously described24. Each remodeling reaction utilized 10 nM nucleosome substrate (MN library or individual MNs) and 0.4 nM ACF in a total reaction volume of 60 μL, concentrations that resulted in approximately 60% of the wild-type nucleosomes remodeled in 64 min. Remodeling assays were carried out in REA buffer (12 mM HEPES, 4 mM Tris, 60 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.6, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.02% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630) in the presence of 2 U/μL PstI-HF restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs). All reaction components except ATP were pre-incubated together at 30 °C for 10 min to allow for cutting of any free DNA. Then ATP, or equivalent buffer volume for no ATP control samples, was added to a final concentration of 2 mM to initiate the remodeling reaction. Remodeling assays were carried out for a total of 64 min at 30 °C, with 6 μL aliquots removed at 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 min and each quenched with 9 μL quench buffer (20 mM Tris, 70 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% SDS).

For gel-based analysis of ACF remodeling, reactions were performed in triplicate with seven time points taken per reaction (t = 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 min). Additionally, one sample was prepared without ATP and incubated for 64 min at 30 °C to serve as a negative control. Samples (7 μL) were analyzed directly on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (0.5x TBE, 195 V, 35 min) and staining was performed with SYBR™ Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Invitrogen). Gel imaging and densitometry calculations were performed as described under general lab protocols.

ACF remodeling experiments on the MN library were performed in triplicate, with and without ATP, over the same seven time points. Samples were then deproteinized with 30 U/mL proteinase K (New England Biolabs) for 1 hr at 37 °C. DNA was subsequently purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and prepared as described for Illumina sequencing. Barcode reads were first normalized among samples by the uncuttable, non-nucleosomal DNA standard. In order to compare remodeling rates of different MNs, barcode reads for each MN were re-scaled by their corresponding values at t = 0 min (as in Extended Data Fig. 7b). Remodeling rates were determined from a collective fit of the time-course data to a single one-phase exponential decay function with a y-intercept fixed at a value of 1, yielding kobs rate values and their corresponding errors. Fits were performed with Python 2.7.10 using the optimize.curve_fit function in the SciPy library (0.15.1). Raw read counts and subsequent calculations can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Production of H2B-CfaN-TwinStrepTag-HisTag

The fusion construct H2B-CfaN-TwinStrepTag-HisTag was produced using standard cloning techniques in the same pET expression vectors described previously. The final construct had the following amino acid sequence:

MPEPAKSAPAPKKGSKKAVTKAQKKDGKKRKRSRKESYSVYVYKVLKQVHPDTGISSKAMGIMNSFVNDIFERIAGEASRLAHYNKRSTITSREIQTAVRLLLPGELAKHAVSEGTKAVTKYTSAKCLSYDTEILTVEYGFLPIGKIVEERIECTVYTVDKNGFVYTQPIAQWHNRGEQEVFEYCLEDGSIIRATKDHKFMTTDGQMLPIDEIFERGLDLKQVDGLPWSHPQFEKGGGSGGGSGGSAWSHPQFEKGSHHHHHH

Protein was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified with standard Ni-NTA affinity chromatography protocols under denaturing conditions. Protein was then further purified by semi-preparative RP-HPLC, characterized by analytical HPLC and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 2c), and subsequently lyophilized and stored at −80 °C until use. H2A/H2B-CfaN dimers were assembled and purified by FPLC as described above with the addition of TCEP (5 mM) to all buffers to prevent disulfide formation.

Generation of heterotypic MNs

601 DNA, H3/H4 tetramers, and H2A/H2B dimers were mixed in ratios of 1:1:1.2, which produced approximately equal amounts of hexasomes and nucleosomes. During this step, non-wild-type dimers were used (e.g. mutant or ubiquitinated dimers), since wild-type dimers were used throughout the rest of the protocol. Hexasome-nucleosome mixtures were then diluted to a concentration of 0.6 μM in complementation buffer (20 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM TCEP, pH 7.6) and H2A/H2B-CfaN-Streptag dimers were added at a DNA:dimer ratio of 1:1 and allowed to incubate for 60 min at room temperature. Note that the optimal quantity of intein-tagged dimers was determined empirically, as over-addition of these dimers caused nucleosome precipitation. Nucleosome complementation was complete after 60 min, as assessed by native gel electophoresis on a 5% TBE gel. To aid in resin purification of intein-tagged asymmetric nucleosomes, 0.02% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. For thermal stability experiments using SYPRO Orange dye, however, use of IGEPAL CA-630 resulted in high background signals. Therefore, for these experiments 0.01% (w/v) octylglucoside (Alfa Aesar) was used as a replacement for IGEPAL CA-630. Intein-tagged nucleosomes were then bound to Strep-Tactin Superflow Plus resin (Qiagen) pre-washed with complementation buffer, using approximately 200 μL resin slurry for 300 pmol 601 DNA. Resin was washed with 4 volumes of nucleosome wash buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.6, and 0.02% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630 or 0.01% (w/v) octylglucoside) and 2 volumes of nucleosome splicing buffer (10 mM Tris, 250 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.6, and 0.02% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630 or 0.01% (v/v) octylglucoside). Nucleosomes were eluted via on-resin thiolysis with the catalytically dead C-intein CfaC30 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Bolded residues denote mutations in CfaC that prevent intein splicing:

VKIISRKSLGTQNVYDIGVEKDHNFLLKNGLVASAAFN

Dead CfaC was diluted to 20 μM in nucleosome splicing buffer and two volumes were added to the resin and allowed to incubate for 8 hr with periodic mixing. Eluted heterotypic nucleosomes were separated from the resin using empty Micro Bio-Spin columns (Bio-Rad) and subsequently concentrated and buffer exchanged into 10 mM TEK buffer using 30 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius). Heterotypic nucleosomes were visualized by native gel electrophoresis on a 5% TBE gel and concentrations were determined by UV spectroscopy at 260 nm.

Generation of mutant H2B-expressing cell lines

HEK293T (CRL-11268, ATCC) and C3H10T1/2 (CCL-226, ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals) at 37 °C, 20% oxygen, and 5% CO2. Cells were dissociated with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) during passaging and regularly tested and found free of mycoplasma.

The murine HIST2H2B cDNA sequence (shown below) was used to generate all H2B constructs:

ATGCCTGAACTGGCCAAATCTGCCCCGGCTCCCAAGAAGGGTTCCAAGAAGGCTGTCACCAAGGCGCAAAAGAAAGATGGCAAGAAGCGCAAGCGCAGCCGCAAGGAGAGCTACTCCATCTATGTGTACAAAGTGCTGAAGCAGGTGCACCCGGACACCGGCATCTCGTCCAAGGCCATGGGCATCATGAACTCGTTTGTCAATGACATCTTTGAGCGCATAGCAAACGAGGCTTCTCGCCTGGCGCATTACAACAAGCGGTCTACAATCACATCGCGGGAGATCCAGACGTCGGTGCGCCTTCTACTGCCCGGAGAACTGGCCAAGCACGCCGTGTCGGAGGGCACCAAGGCCGTCACCAAGTACACCAGCGCCAAGGCGGCCGCTGGAGGAGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGTCGGCCGCTGGAGGATACCCCTACGACGTGCCCGACTACGCCTAG

HA-FLAG-tagged wild-type and mutant H2B constructs were cloned into pCDH-EF1-MCS-Puro lentiviral vectors (Systems Biosciences) as previously described11. To produce lentivirus, HEK293T cells (ATCC) were transfected with the lentiviral vectors and helper plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G). After 72 hr, the supernatant (containing lentivirus) was collected, filtered, and concentrated. C3H10T1/2 cells (ATCC) were transduced with concentrated lentivirus (2 × 107 IFU) and grown under puromycin selection (2 μg/mL) 48 hr after transduction.

Acid histone extraction and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed with hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Hepes, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, protease inhibitors) for 1 hr at 4 °C. The nuclei pellet was resuspended in 0.2 N H2SO4 overnight at 4°C with agitation. After centrifugation (16,000 g, 10 min at 4 °C), supernatants were collected and histone proteins were precipitated in 33% TCA. The histone pellet was washed with acetone and resuspended in deionized water. Sample concentrations were quantified using a protein quantification assay (BioRad, cat #5000006) using a mixture of histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 as a standard. Before gel analysis, samples were resuspended in SDS-Laemmli buffer and boiled for 10 min. Samples were run on Novex™ 16% Tris-Glycine gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then blocked (PBS with 5% milk and 0.1% Tween-20) and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight in PBS with 2% milk and 0.1% Tween-20: rabbit anti-histone H2B antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 12364) and mouse anti-HA tag antibody (BioLegend, 901501) at 1:1000 diliutions. HRP-coupled secondary anti-mouse (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, NA931) and anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad, 1706515) antibodies were used at 1:5000 dilutions and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Immobilon Western, Millipore) using an Amersham Imager 600. To quantify relative expression levels of mutant histones, a standard curve of untagged murine H2B (mH2B) and tagged mH2B (mH2B-FLAG-HA) were loaded adjacent to samples from cellular histone fractions, allowing the estimation of relative histone expression by comparison of anti-HA and anti-H2B signals (Extended Data Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Immunofluorescence

C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded onto sterile coverslips. After 24 hr, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, washed twice with PBS, and then blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 20 min. Coverslips were rinsed with PBS and incubated overnight with mouse Alexa Fluor 488 anti-HA antibody (BioLegend, 901509) at a dilution of 1:100. Coverslips were then washed five times with PBS and samples stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Fluorescent images were obtained with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

RT-qPCR and RNA-seq analyses

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). For quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), extracted RNA was treated with DNase and cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). qPCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and data normalized to a GAPDH reference gene. All qPCR primers are listed in Supplementary Table 8. For RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), libraries were prepared according to the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit (New Enbland Biolabs) protocol and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq instrument.

Quantification of RNA transcripts was performed with the k-mer counting software Salmon57, and a reference genome produced using Illumina’s iGenomes UCSC mm10 package. Expression levels were estimated by counting reads with featureCounts (v1.4.4) using default settings. Read summarization was performed at the gene symbol level using UCSC mm10 known gene exons obtained from the UCSC table browser. The gene symbol-summarized read counts were normalized using the variance stabilized transformation technique (VST), and expression levels clustered using Euclidean distance and hierarchical clustering with the Ward variance minimization algorithm to produce heatmaps. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the DESeq Package58,59. Differentially expressed genes were determined by a log2 fold-change cutoff of ±1 with a 5% FDR. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed with DAVID and top GO and KEGG pathway terms were plotted against their Benjamini FDR values on a logarithmic scale.

Cellular differentiation assays

Adipocyte differentiation was performed by stimulating confluent C3H10T1/2 cells with a cocktail of 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 μM dexamethasone, 5 μg/ml insulin, and 5 μM troglitazone (all from Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM with 10% FBS. After two days, cells were maintained in DMEM with insulin for an additional five days. On day seven, cells were washed in PBS and then fixed with 3% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were then stained with Oil Red O solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and the extent of differentiation quantified by measuring absorbance at 500 nm.

Chondrocyte differentiation was performed by stimulating confluent C3H10T1/2 cells with a cocktail of 10 μg/mL insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), 30 nM sodium selenite (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL human transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 ng/mL rhBMP-2 (R&D Systems) in DMEM with 1% FBS. Medium was replaced with fresh cocktail every 2–3 days until day nine when cells were washed in PBS and then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were stained with 1% Alcian Blue 8GX (pH 1.0, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr at room temperature. For quantification, cells were lysed in 1% SDS and absorbance measured at 605 nm.

Statistics and Reproducibility