Abstract

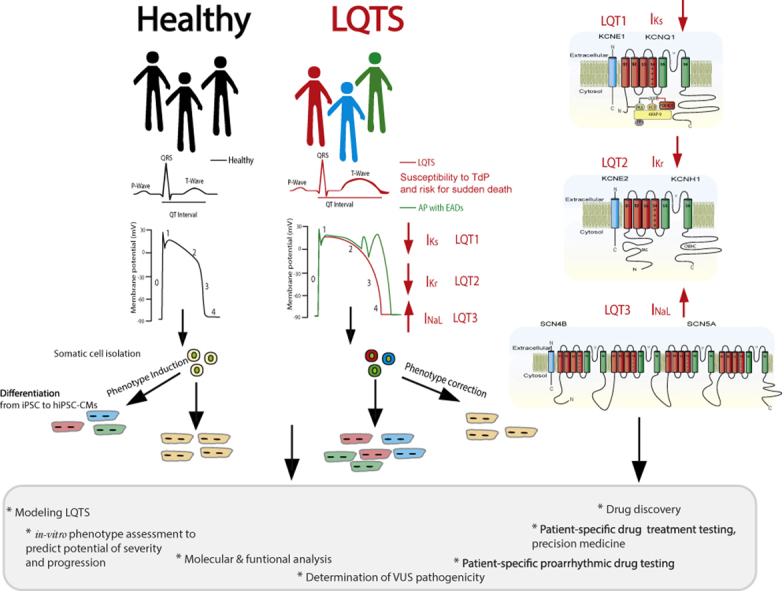

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiovascular disorder characterized by an abnormality in cardiac repolarization leading to a prolonged QT interval and T-wave irregularities on the surface electrocardiogram. It is commonly associated with syncope, seizures, susceptibility to torsades de pointes, and risk for sudden death. LQTS is a rare genetic disorder and a major preventable cause of sudden cardiac death in the young. The availability of therapy for this lethal disease emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis. Additionally, understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying LQTS could help to optimize genotype-specific treatments to prevent deaths in LQTS patients.

In this review, we briefly summarize current knowledge regarding molecular underpinning of LQTS, in particular focusing on LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3, and discuss novel strategies to study ion channel dysfunction and drug-specific therapies in LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3 syndromes.

Keywords: Genetic variants, Induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocyte (iPSC-CM), Long QT syndrome, Potassium channel, Precision medicine, Sodium channel

Graphical abstract

Key Findings.

-

▪

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiovascular disorder characterized by an abnormality in cardiac repolarization leading to a prolonged QT interval. It is commonly associated with syncope, seizures, susceptibility to torsades de pointes and risk for sudden death.

-

▪

At this time there are 17 subtypes of congenital LQTS, each associated with a different gene. The most frequent LQTS subtypes are LQT1, associated with mutations in KCNQ1; LQT2, caused by mutations in KCNH2; and LQT3, associated with mutations in SCN5A.

-

▪

Hundreds of LQTS mutations are found in KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A genes. Yet even within 1 gene, the mutations present with different mechanisms and different severity and, even more importantly, variability is also seen for the same mutation among different patients.

-

▪

Early diagnosis is important to identify LQTS patients at lower vs higher risk of cardiac events, to determine the appropriate therapy, and to identify LQTS patients displaying incomplete penetrance with different clinical phenotypes.

-

▪

In general, beta-blocker therapy is the drug treatment of choice for LQTS patients.

-

▪

The use of human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes, next-generation sequencing, high-throughput patch-clamping, and deep mutation scanning are all relatively recent new approaches that have been applied to the study of LQTS and we are starting to see the benefits by translating our findings from bench to bedside.

Introduction

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiovascular disorder characterized by an abnormality in cardiac repolarization leading to a prolonged QT interval and T-wave irregularities on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG).1, 2, 3, 4 It is commonly associated with syncope, seizures, susceptibility to torsades de pointes, and risk for sudden death.1, 2, 3, 4 Actually, the diagnostic criteria proposed for LQTS are a heart rate–corrected QT interval (QTc) ≥ 480 ms or a “Schwartz” score > 3 points for clinical diagnosis. In the presence of unexplained syncope, however, a QTc ≥ 460 ms is sufficient to make a diagnosis.1,2 Classically, LQTS assumes 2 clinically recognized forms: autosomal-dominant Romano-Ward syndrome and autosomal-recessive Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, which presents with a malignant cardiac phenotype along with congenital bilateral sensorineural deafness.5,6 The prevalence of congenital LQTS is estimated to be close to 1 in 2000 individuals.7 LQTS is a rare genetic disorder and a major preventable cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young. The availability of therapy for this lethal disease emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis. Additionally, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying LQTS could help to optimize genotype-specific treatments to prevent deaths in LQTS patients.

There are 17 subtypes of congenital LQTS, each associated with a different gene (Table 1). The most frequent LQTS subtypes are type 1 (LQT1), type 2 (LQT2), and type 3 (LQT3).8 LQT1 is associated with mutations in KCNQ1 (IKs potassium channel [Kv7.1]), LQT2 is caused by mutations in KCNH2 (IKr potassium channel [Kv11.1]), and mutations in SCN5A (INa sodium channel [NaV1.5]) are linked to LQT3. These 3 genes combined account for approximately 65% of all LQTS and approximately 80% of genotype-positive LQTS cases9, 10, 11, 12 (Table 2). Less frequently, LQTS-associated mutations exist in many other genes (KCNJ2, KCNJ5, CACNA1C, KCNE1, KCNE2, AKAP9, ANK2, SCNA4B, SNTA1, CALM1-3, CAV3, and TRDN) encoding for ion channels, regulatory channel subunits, and signaling or adaptor-associated proteins.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Table 1.

Subtypes of congenital long QT syndrome and their associated genes, proteins and effects on cardiac currents

| LQTS type | Gene | Protein | Function | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQT1 | KCNQ1 | Kv7.1 | α-subunit IKs | Loss of function | Wang et al 1996 |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 | Kv11.1 | α-subunit IKr | Loss of function | Sanguinetti et al 1995; |

| Curran et al 1995 | |||||

| LQT3 | SCN5A | NaV1.5 | α-subunit INa | Gain of function | Wang et al 1995 |

| LQT4 | ANK2 | Ankyrin B | Adaptor | Loss of function | Mohler et al 2003; |

| Schott et al 1995 | |||||

| LQT5 | KCNE1 | minK | β-subunit IKs | Loss of function | Splawski et al 1997; |

| Schulze-Bahr et al 1997 | |||||

| LQT6 | KCNE2 | MiRP1 | β-subunit IKr | Loss of function | Abbott et al 1999 |

| LQT7 (Andersen syndrome) | KCNJ2 | Kir2.1 | α-subunit IK1 | Loss of function | Plaster et al 2001 |

| LQT8 (Timothy syndrome) | CACNA1C | CaV1.2 | α-subunit ICa | Gain of function | Splawski et al 2004 |

| LQT9 | CAV3 | Caveolin | Adaptor | Loss of function | Vatta et al 2006 |

| LQT10 | SCN4B | NaVβ4 | β-subunit INa | Loss of function | Medeiros-Domingo et al 2007 |

| LQT11 | AKAP9 | Yotiao, (A- anchor protein 9) | Adaptor | Loss of function | Chen et al 2007; |

| Bottigliero et al 2019 | |||||

| LQT12 | SNTA1 | α1-syntrophin | scaffolding | Loss of function | Ueda et al 2008 |

| LQT13 | KCNJ5 | Kir3.4 | α-subunit IK-Ach | Loss of function | Yang et al 2010 |

| LQT14 | CALM1 | Calmodulin 1 | Signaling protein | Dysfuntional Ca2+ Signaling |

Pipilas et al 2016; |

| Boczek et al 2016 | |||||

| LQT15 | CALM2 | Calmodulin 2 | Signaling protein | Dysfunctional Ca2+ Signaling |

Boczek et al 2016 |

| LQT16 | CALM3 | Calmodulin 3 | Signaling protein | Dysfuntional Ca2+ Signaling |

Reed et al 2015; |

| Chaix et al 2016; | |||||

| Boczek et al 2016 | |||||

| LQT17 | TRDN | Triadin | Ca2+ homeostasis regulation | Loss of function | Altmann et al 2015 |

Table 2.

Distinguishing features of long QT syndrome for the most common genetic mutations

| Genotype | LQT1 | LQT2 | LQT3 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetics | KCNQ1 | KCNH2 | SCN5A | Wang et al 1996 |

| Sanguinetti et al 1995; | ||||

| Curran et al 1995 | ||||

| Wang et al 1995 | ||||

| Frequency,% | 42-49% | 39-45% | 8-10% | Splaswski et al 2000 |

| Napolitano et al 2005 | ||||

| Function | Loss-of function | Loss-of function | Gain-of-function | Wang et al 1996 |

| Sanguinetti et al 1995; | ||||

| Curran et al 1995 | ||||

| Wang et al 1995 | ||||

| Ion current affected | ↓ IKs | ↓ IKr | ↑ INa | Wang et al 1996 |

| Sanguinetti et al 1995; | ||||

| Curran et al 1995 | ||||

| Wang et al 1995 | ||||

| Incidence of cardiac events frequently triggered by,% | Exercise, (swimming and water activities) 55% Arousal, 14% Sleep/rest, 21% Other, 10% |

Arousal-triggers, (sudden loud noise), 44% Exercise, 13% Nonexercise/nonarousal, 43% |

Rest, 29% Sleep, 39% Exercise, 13% |

Schwartz et al 2001 |

| Sakaguchi et al 2008 | ||||

| Goldenberg et al 2012 | ||||

| Kim et al 2010 | ||||

| Likelihood of dying during a cardiac event,% | 4% | 4% | 20% | Zareba et al 1998 |

| Wilde et al 2016 | ||||

| Response to β-blockade | + + + | + + | Controversial | Priori et al 2013 |

| Priori et al 2016 | ||||

| Ahn et al 2017 | ||||

| Mazzanti et al 2018 | ||||

| MacIntyre et al 2020 | ||||

| Response to sodium channel blockers | + + | Chorin et al 2018 | ||

| Mazzanti et al 2016 | ||||

| Blich et al 2019 | ||||

| Chorin et al 2016 | ||||

| Moss et al 2008 |

+, low likelihood; + +, moderate likelihood; + + +, high likelihood.

Molecular underpinning of LQTS

The normal electrophysiological behavior of the heart is determined by ordered propagation of excitatory stimuli that result in rapid depolarization and slow repolarization, thereby generating cardiac action potentials (APs) in individual myocytes.29 The cardiac AP depends on the orchestrated voltage- and time-dependent opening and closing of selective ion channels formed by proteins that are embedded in the lipid bilayer of the cardiomyocyte membrane. The cardiac electrical system is designed to ensure the appropriate rate and timing of contraction in all regions of the heart, which are essential for effective cardiac function.29, 30, 31 Abnormalities of impulse generation, propagation, or the duration and configuration of individual cardiac AP waveform are the basis of disorders of cardiac rhythm and contractile dysfunction.

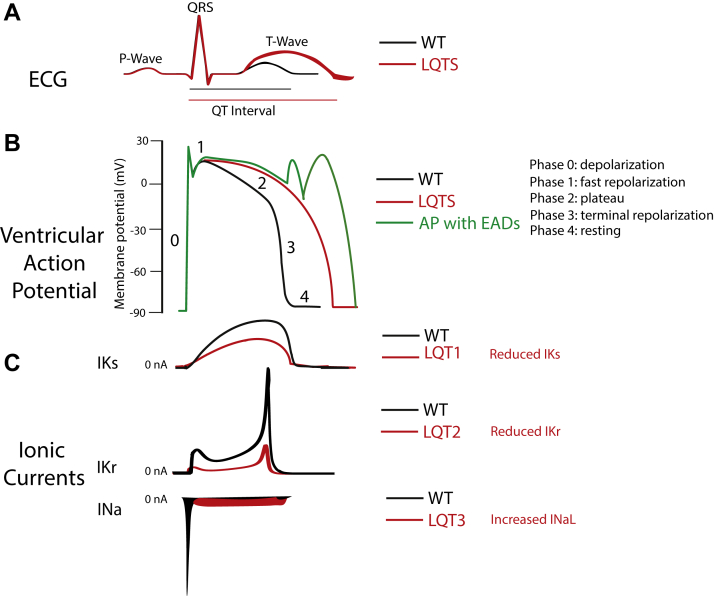

On the surface ECG, the QT interval reflects the duration of the ventricular AP generated by various cardiac ion currents, including sodium, calcium, and potassium currents.29 The QT prolongation is the hallmark of LQTS, and it may form via 1 of 2 pathways: reduction in the outward potassium currents during phase 3 of the AP (“loss of function”) or an increase in late entry of sodium or calcium currents (“gain of function”) during the AP repolarization phase. Prolongation of the AP duration occurs regardless of the underlying mechanism of QT prolongation. Increased cardiomyocyte refractoriness generates an electrical substrate that can give rise to early afterdepolarizations and transmural dispersion of repolarization, providing the substrate for cardiac events and fatal arrhythmias as torsades de pointes29 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

From the electrocardiogram (ECG) to cellular ion currents. Voltage-activated Na+ and K+ currents define the ventricular action potential and the QT interval of the ECG. A: Simulated ECG trace in normal conditions (black trace) and LQTS (red trace). The rapid upstroke of the ventricular action potential gives rise to the QRS complex. The duration of the QT interval is determined by the time of the ventricular repolarization. B: Simulated ventricular action potential in physiological situation (black trace), the rapidly activating and inactivating peak INa drives membrane depolarization; a very small sustained or late INaL is present. Two K+ currents, IKs and IKr, contribute mostly to the plateau phase and repolarization phase of the action potential, which restores the membrane resting potential. Simulated functional effect of loss of function of either IKs or IKr or gain of function of INaL on the ventricular action potential result in prolongation of ventricular action potential associated with LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3, respectively (red trace). Simulated action potential with early afterdepolarization events (green trace). C: Simulated normal time course and amplitude of IKs, IKr, and INa currents (black traces). Simulated different mechanisms that can be responsible for LQTS. IKs loss of function associated with LQT1, IKr loss of function associated with LQT2, and gain-of-function INaL associated with LQT3 (currents not drawn to scale). Currents of other ion channels contribution to the action potential (eg, ICa,L, Ito, IK1, and INCX) are not shown for clarity.

LQT1, IKs loss of function

IKs,KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel

KCNQ1 is the pore- forming α-subunit of the slowly activated delayed-rectifier K+ current (Kv7.1). In cardiac cells, KCNQ1 co-assembles with the β-subunit KCNE1 (MinK) to form IKs. IKs is the outward K+ current generated by KCNQ1/KCNE1 complex and is one of the repolarizing K+ currents that contribute to the termination of the cardiac AP.32,33 IKs primarily contributes to AP repolarization during β-adrenergic stimulation, when its current amplitude is increased and rate of activation accelerated.34,35

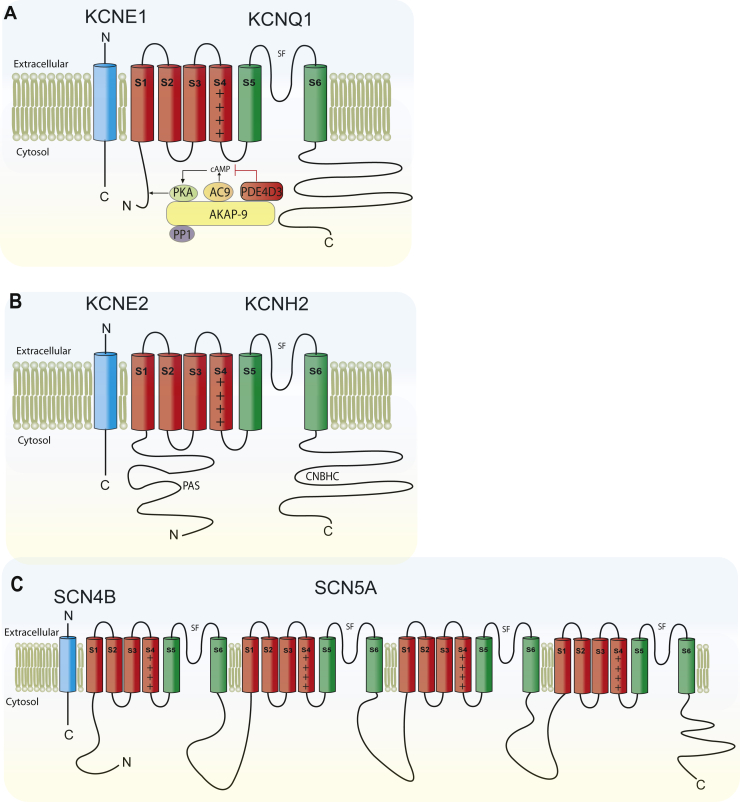

Like other voltage-gated ion channels, KCNQ1 shares a common core structure of 4 identical α-subunits, each containing 6 membrane-spanning segments with a voltage-sensing domain (S1–S4) and a pore loop domain (S5–S6) that contributes to the ion selectivity filter in the homotetramers to create the KCNQ1 channel. Additionally, KCNQ1 subunits possess a large COOH terminus, which is important for channel gating, assembly, and trafficking36,37 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Overall topology of KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A. A:KCNQ1 topology. Four KCNQ1 tetramerize to comprise the pore-forming α-subunit; each α-subunit contains 6 transmembrane segments, labeled as S1–S6. SF denotes the selectivity filter. Additionally, IKs macromolecular complex is illustrated, including β-subunit KCNE1, and associated scaffolding and signaling proteins. B:KCNH2, known as the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG). Pore-forming α-subunit transmembrane segments are labeled S1–S6; SF denotes the selectivity filter topology. PAS denotes Per-Arnt-Sim domain, also referred to as “eag domain.” CNBHC denotes cyclic nucleotide-binding homology domain. Additionally, the β-subunit KCNE2 (MiRP1), which associates with KCNH2 α subunits resembling native cardiac IKr channels, is illustrated. C:SCN5A topology of α subunit with auxiliary SCN4B β subunit.

Interacting ion channel subunits KCNQ1 and KCNE1 have received intense investigation owing to their critical importance in human cardiovascular health. In addition to KCNE1, the other 4 members of the KCNE family (KCNE2–5) are capable of associating with KCNQ1, to also regulate channel behavior and to confer specific pharmacological features to the IKs current.38, 39, 40 Interactions between the transmembrane domains of the α- and β-subunits determine the activation kinetics of IKs.41 Additionally, a physical and functional interaction between COOH termini of the proteins has also been identified that impacts deactivation rate and voltage dependence of activation, enhancing phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate sensitivity.42,43 This proximal COOH termini region of functional interaction between KCNQ1/KCNE1 complexes is between the KCNQ1 residues 352–374 and KCNE1 residues 70–81.44 Additionally, there is strong evidence that deleterious mutations in either gene KCNQ110,45 or KCNE146,47 are associated with loss of IKs function and result in LQT1 and LQT5, respectively.

Ca2+- and calmodulin modulation of KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel

KCNQ1/KCNE1 complex interaction is a dynamic process; it has been shown that under basal conditions, KCNE1 in adult ventricular myocytes maintains a stable presence on the surface, whereas KCNQ1 is dynamic on its localization. KCNQ1 is largely in intracellular reservoirs but can traffic to the cell surface and boost the IKs amplitude in response to stress in a Ca2+- and calmodulin (CaM)-dependent manner.34 CaM acts as an additional essential auxiliary subunit of the KCNQ1/KCNE1 complex, with CaM binding to the proximal COOH termini of the KCNQ1 channel. CaM binding to KCNQ1 is essential for correct channel folding and assembly and for conferring Ca2+-sensitive IKs stimulation, which increases the cardiac repolarization reserve.37 Mutations associated with LQT syndrome located near the IQ motif mediate Ca2+-free CaM binding to KCNQ1 at the COOH termini, which impairs CaM binding to KCNQ1, alters channel assembly, and stabilizes inactivation, which results in a decrease in current density.37

PIP2 regulation of KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel

The channel activity of KCNQ1 is also regulated by signaling lipid PIP2. PIP2 functions as a co-factor of KCNQ1 homotetramers as well as its complexes with different KCNEs. PIP2 is required to stabilize the KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel open state, leading to an increased current amplitude, slowed deactivation kinetics, and a shift in the activation curve toward negative potentials.43 In addition, the auxiliary β-subunit KCNE1 increases PIP2 sensitivity over channels formed by the pore-forming α-subunit KCNQ1 alone.48 Several LQT-associated mutations reduce PIP2 affinity for KCNQ,49 and there is evidence that KCNE1 can alter the function of IKs by modulating the interaction between PIP2 and the heteromeric ion channel complex. Mutations of the putative PIP2 interaction site in KCNE1 (R67C, R67H, K70M, and K70N) have also been identified in LQT patients as disease-associated mutations.48

β-adrenergic receptor modulation of KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel

The A-kinase anchoring protein 9 (AKAP-9) is another critical protein that modulates adrenergic response of the KCNQ1/KCNE1 complex.50 AKAP-9, also known as yotiao protein, is a scaffolding protein that dynamically recruits signaling molecules and presents them to downstream targets to achieve efficient spatial and temporal control of their phosphorylation state.51 In the heart, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) regulation of the action potential duration (APD) mediated by β-adrenergic receptor requires assembly of AKAP-9 with IKs α subunit. AKAP-9 directly binds to KCNQ1 by a leucine zipper motif localized in its COOH termini and recruits the signaling molecules adenosine 3′, 5′–monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase, phosphatase 1, phosphodiesterase, and adenylyl cyclase 9 to KCNQ1 through its binding.50,52, 53, 54 Mutations that disrupt IKs–AKAP-9 interaction result in reduced protein kinase–dependent phosphorylation of IKs subunit KCNQ1 and inhibition of the SNS stimulation of IKs, which can lead to LQTS. Different AKAP-9 mutations have been associated with LQTS55,56 classified as LQT11. In addition, AKAP-9 has been identified as a genetic modifier of LQT1 syndrome contributing to phenotypic variability in patients with the same primary-causing mutation.20

Clinical aspects and arrhythmic triggers

Under normal physiological conditions, sympathetic activation promotes IKs, which shortens ventricular repolarization against the activation of L-type Ca2+ channel and thereby protects against Ca2+- related arrhythmogenicity. When IKs is defective owing to KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel mutations, the ventricular repolarization or QT intervals fails to shorten appropriately, thus creating a highly arrhythmogenic condition.57

In patients with LQT1 syndrome, cardiac events are more frequently triggered by adrenergic stimuli (eg, physical and emotional stress). Studies indicated that LQT1 patients experience the majority of their events during exercise (55%), with arousal (14%), with sleep/rest (21%), and with other triggers (10%).58, 59, 60 Additionally, analysis showed that male LQT1 patients are younger than female at first event, and male patients <13 years old had a 2.8-fold increase in the risk for exercise-trigger events, whereas female patients ≥13 years showed a 3.5-fold increase in the risk for sleep/rest nonarousal events.59, 60, 61 Moreover, during adulthood, LQT1 female patients have a significantly higher risk of cardiac events compared to respective male patients.62 It has been suggested that patients with LQT1 may need greater attention and advanced treatment early during their lifetime since they exhibited an increased probability of cardiac events during the first 20 years of life.63 Together, these reports stress the importance of age-related therapy for genotype LQTS patients.

Several studies have focused on determining factors associated with the occurrence of cardiac events in LQTS patients. Principally, clinical and genetic findings associated swimming and water activities with precipitation of cardiac events in LQT1 patients.64,65 Recently, an in vivo study aimed to compare LQTS responses to arrhythmia triggers reported that in response to simulated diving, a slower heart rate was observed in LQT1 patients. The authors of the study mentioned that although bradycardia is a well-established risk factor for arrhythmias in LQTS patients, further studies are needed to fully understand the association with swimming-associated events.66

Furthermore, genotype-phenotype studies in LQT1 syndrome indicated that LQT1 patients with mutations located in the transmembrane portion of the ion channel are at the highest risk of congenital LQTS-related cardiac events and have greater sensitivity to sympathetic stimulation compared with patients with COOH terminal mutations.67,68 In addition, the degree of ion channel dysfunction caused by the mutations is an important independent risk factor influencing the clinical course of this disorder.68

Several studies were aimed at determining the relation between arrhythmic risk factors and mutation location; yet the factors that could determine the genotype-phenotype severity in LQT1 syndrome patients remain unclear. However, further examination of this correlation will be important to offer an efficient management and treatment of the patients with LQT1 syndrome. Great advances in high-throughput screening of mutations will certainly greatly help toward this goal, as described later on in this review.

LQT2, IKr loss of function

IKr, KCNH2/KCNE2 channel

KCNH2 is also known as the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG).69 Two channel α subunits encoded by KCNH2 (hERG 1a and 1b) are expressed in cardiac tissues70, 71, 72, 73 and both isoforms encode the voltage-gated KV11.1 channel α subunit, which underlies the rapid component of the delayed inward-rectifying K+ current (IKr).69,74 IKr is characterized by slow activation and deactivation kinetics, coupled to rapid inactivation and recovery from inactivation, which are partially responsible in determining the prolonged plateau phase typical of the ventricular AP.75, 76, 77 The most distinct and physiologically significant gating characteristics of hERG channel are its rapid inactivation and slow deactivation.75,77

The presence of rapid inactivation means that with the cell membrane depolarization, the channel opens but it very quickly enters the inactivated state (nonconducting), passing very little current in the outward direction. As the AP repolarization begins, hERG channels recover from inactivation, so the channel retraces its conformational steps and passes through the open state on the way back to its closed configuration, which occurs when the membrane returns to its normal resting potential near -80 mV. The hERG channel return to the closed state (referred to as deactivation) is very slow, and consequently a large “tail K+” current is observed hastening repolarization and ensuring that repolarization is relatively rapid and robust.75, 76, 77 This hERG channel gating characteristic plays an important role in cardiac electrical excitability by governing the length of the AP.74

When expressed heterologously, hERG1a homomeric and 1a/1b heteromeric channels yield robust currents. In contrast, homomeric hERG 1b channels produce undetectable or very small currents.78 Furthermore, hERG1a/1b channel subunits directly interact and preferentially form heteromeric channels.79 The hERG 1a/1b channels share the general architecture with other voltage-gated ion channels, composed of 4 subunits surrounding a central pore. However, hERG 1a/1b channels differ in their primary structure and functional properties. hERG 1a are distinguished by the presence of an NH2 terminal PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim) domain, also referred to as “eag domain,” that is preceded by a shorter PAS-CAP region, whereas hERG 1b has a shorter NH2 terminal and lacks PAS domain.70, 71, 72,79,80 Furthermore, the KCNH channels COOH termini region contains a C-linker and cyclic nucleotide-binding homology domain (CNBHC).69,81 Findings reveal that an inter-subunit interaction between the eag domain and the C-linker CNBHC regulates slow deactivation in the hERG channels at the plasma membrane.82, 83, 84 The region between the S4 and S5 transmembrane domains (S4–S5 linker) is also implicated in regulating slow deactivation of KCNH channels82 (Figure 2B). Under heterologous expression, hERG 1a forms homotetrameric channels, which have robust and slow kinetics of channel closing, whereas hERG 1b forms homotetrameric channels with small currents and faster kinetics of closing than hERG 1a. Fast deactivation of hERG 1b is attributable to the lack of the eag domain, which promotes slow deactivation in hERG 1a.79,82, 83, 84, 85, 86 Findings indicate that IKr in human cardiac myocytes and cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC-CMs) are minimally composed of hERG 1a and hERG 1b α subunits.72,73,85

Genetic mutations in both hERG 1a and hERG 1b subunits are associated with LQT2 syndrome, indicating the pathophysiological importance of both isoforms.74,87,88 Mutations in hERG channel that cause LQT2 can reduce the amplitude of IKr by several different mechanisms, which can be defined in 4 classes, including abnormal channel synthesis (transcription/translation) class 1, deficient protein transport or trafficking class 2, abnormal channel gating/kinetics class 3, and disrupted channel permeability or selectivity class 4.89, 90, 91 All these alterations reduce outward current through hERG channels during repolarization, thus lengthening the cardiac APD, which is reflected on the surface ECG as prolonged QT interval.85

In regards to the association of both KCNH2 isoforms (hERG 1a-1b), it has also been shown that the β-subunit KCNE2 (MiRP1) associates with KCNH2 α subunits resembling native cardiac IKr channel characteristics in their gating, unitary conductance, regulation by potassium, and distinctive biphasic inhibition by the class III antiarrhythmic E-4031.92 The functional interactions between hERG 1a-1b/KCNE2 ion channel subunits have been investigated, with initial reports suggesting that mutations within KCNE2 β-subunit are implicated as causative of LQT6 syndrome.92,93 However, later studies showed that KCNH2 rare variants resulting in loss of function do not seem sufficient in isolation to cause LQT6 syndrome but may confer proarrhythmic susceptibility when provoked by additional environmental or genetic factors.94 Moreover, lines of evidence suggest that variants in KCNE2 contribute to a significant fraction of cases of drug-induced LQTS,95 highlighting the importance of the KCNE2 β-subunit. However, collectively, the importance of KCNH2 β-subunit in LQT6 syndrome remains unclear, and further studies are needed to better understand the physiological significance of the role of KCNH2 for arrhythmia susceptibility or as a disease-cause gene.

Clinical aspects and arrhythmic triggers

After LQT1 syndrome, type 2 LQTS is the second most common LQTS.9 Diminution in the repolarizing IKr current contributes to lengthening of the QT interval.74 In patients with LQT2, the majority of cardiac event stimuli are sudden arousal triggers, whereas a lower portion of events are associated with exercise activity.58 Forty-four percent of cardiac events in LQT2 patients are associated with arousal-triggers (like sudden loud noise), 13% with exercise activity, and 43% with nonexercise/nonarousal triggers.96 Principally, auditory stimuli have been related with triggered cardiac events in LQT2 patients.64,66 Sex has also been identified as an important independent contributor to cardiac event risks in LQT2, as adolescent and adult women were shown to have higher risk for cardiac events than the corresponding men in this population.59,61, 62, 63 Furthermore, reports show that women with LQTS have a reduced risk for cardiac events during pregnancy, but an increased risk during the 9-month postpartum period, especially among women with LQT2.97

In addition to these phenotype-genotype associations, patients with mutations in the pore region of KCNH2 gene are at markedly higher risk for arrhythmia-related cardiac events compared with patients with non-pore mutation.98,99 Thus, it has been suggested that the risk assessment in LQT2 patients should include trigger-specific recommendations for lifestyle modifications and medical therapy that relate to the age, sex, and location of the mutation of an affected patient.96

LQT3, INa gain of function

INa, NaV1.5 channel

The gene SCN5A encodes the cardiac voltage-gated pore-forming α-subunit of the Na+ channel (NaV1.5).100 Two SCN5A splice variants are commonly present in human hearts: 1 comprises 2016 amino acids and contains a glutamine at position 1077 (Q1077) and 1 has only 2015 amino acids because of the absence of this amino acid (Q1077del).101 The NaV1.5 α-subunit is composed of 4 homologous domains (DI-DIV), each with 6 transmembrane segments (S1–S6).102, 103, 104, 105 The actual Na+ conducting channel pore is formed by the S5–S6 segments with the pore loop between them. The 3 intracellular linker loops as well as the NH2 and COOH terminus of the channel are cytoplasmic102, 103, 104, 105 (Figure 2C).

Although the NaV1.5 α-subunit is functional on its own, NaV1.5 forms complexes with auxiliaries’ β subunits that modulate functional NaV1.5 expression.106, 107, 108 Furthermore, beside β subunits, NaV1.5 channels interact with other proteins that regulate its function or membrane expression.109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129

The NaV1.5 channel permeates inward sodium current (INa), which is the main depolarizing current (phase 0 of the AP) in cardiomyocytes and thus is critical for normal electrical conduction. Upon depolarization, NaV1.5 channel quickly inactivates.86 While this process happens for the majority of the Na+ channels, there is a small fraction of channels that do not remain inactivated, allowing them to reopen and/or stay open during the repolarization phase of the AP. This current is called “sustained current” or “late current, INaL.”130,131 Finally, some channels may reactivate during the repolarizing phase of the AP at a range of potentials where inactivation is not complete and shows overlap with activation, generating the “window current.”132

Mutations in SCN5A are associated with LQT3 syndrome.133 At least 3 distinct common forms of gain-of-function mutations in SCN5A have been linked to LQT3 syndrome. The most common result in gain of function owing to transient inactivation failure, termed “bursting,” which produces sustained Na+ channel activity over the plateau voltage range of the AP.134 A second is owing to an increase in window current.135,136 The third mechanism is owing to NaV1.5 channels recovering from inactivation faster, resulting in reopening during AP repolarization.137

Furthermore, mutations in several NaV1.5 channels’ interacting protein partners form part of the rare LQTS susceptibility genes. They include mutations in the gene SCN4B encoding the β4 subunit. Mutations in SCN4B have been linked to LQT10138 and they result in an increase in INaL. Variants in the CAV3 gene are associated with LQT9 syndrome18,139 and result in enhanced INaL. Mutations in the SNTA1 gene, which encodes for the scaffold protein α1-syntrophin, have been shown to induce INaL gain of function and thus join the list of rare LQTS susceptibility genes, as LQT12 syndrome.19

Clinical aspects and arrhythmic triggers

LQT3 syndrome is the third in frequency compared to the 17 forms currently known of congenital LQTS.8,9 However, cardiac events are less frequent in LQT3 when compared with cardiac events in LQT1 and LQT2 patients. Studies have shown that LQT3 patients are less likely to have cardiac events during exercise (13%) and more likely to have events during rest/sleep (29% and 39%).58,59 While the first cardiac event seems to occur later in childhood during or after puberty,140 the first cardiac event is more likely to be lethal; indeed, dying during a cardiac event is higher in LQT3 patients (20%) than LQT1 (4%) and LQT2 (4%).140,141 Moreover, similar lethality from cardiac events was observed between male and female LQT3 patients, at 19% and 18%, respectively.62 Furthermore, mutational-specific risk in patients with 2 relatively common LQT3 mutations has shown that patients with the deletion mutation (ΔKPQ) had a significantly higher risk of cardiac events as compared with patients carrying the missense mutation D1790G,142 which, much like for LQT1 and LQT2, highlights the importance of genotype-specific diagnosis and intervention.

Currently, it is well recognized that patients with LQT3 frequently present with coexistence of associated characteristics, including discrete conduction disturbances, bradycardia, atrial arrhythmias, and Brugada syndrome (BrS). Therefore, in patients with LQT3, overlapping syndromes have been observed.143, 144, 145, 146 Importantly, it has also been shown that a single specific SCN5A mutation associated with LQT3 can result in multiple phenotypes in different families or even among members of 1 family.147, 148, 149 Moreover, clinical evidence showed that an overlapping syndrome with a phenotype mixed between LQT3 and Purkinje-related premature ventricular contractions can also exist.150 In addition, reports show that there is an association between the LQT3 genotype and risk of early onset of atrial fibrillation.151 Consequently, recognizing the overlapping phenotypes of an SCN5A mutation in a particular patient is of utmost importance not only for designing patient-specific treatment strategies, as drugs used to treat one phenotype may aggravate the other, but also for better risk stratification, as a risk for adverse events may increase when a second phenotype is present.152,153

Other less frequent LQTS-associated mutations

Mutations in 3 more ion channels are also associated with LQTS: CaV1.2, Kir2.1, and Kir3.4. Gain-of-function mutations in the CACNA1C gene encoding the cardiac voltage-gated pore-forming α subunit Ca2+ channel (CaV1.2) lead to LQT8 syndrome (Timothy syndrome).16 Increase in ICa will delay cardiomyocyte repolarization, resulting in QT interval prolongation.16 Loss-of-function mutations in KCNJ2 and KCNJ5 genes encoding cardiac inward rectifier K+ pore-forming α subunits of Kir2.1 and Kir3.4 channels, which underline IK1 and IKAch, are associated with LQT7 (Andersen’s syndrome) and LQT13 syndromes, respectively.17,21 IK1 contributes significantly to the repolarizing current during the terminal phase of the cardiac AP and serves as primary conductance controlling the diastolic resting membrane potential in atrial and ventricular myocytes. Reduction in Kir2.1 function would be expected to prolong the cardiac AP and QT interval.21 The IKAch role in ventricular repolarization is clearly relevant, as illustrated by the link between loss-of-function IKAch and LQT13 syndrome.17

Additionally, mutations in adaptor- and signaling-associated proteins are also linked to LQTS. Loss-of-function mutations in ANK2 gene encoding the membrane adaptor proteins ankyrin-B are associated with LQT4 syndrome.24,154 LQT14, LQT15, and LQT16 are caused by variants in CaM encoding genes CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3, respectively.22,23,25,26 Studies have shown that CaM mutations associated with LQTS impair Ca2+ binding affinity and impair modulation of cellular targets, particularly the Ca2+ channel. Specifically, reports have shown that CaM mutants associated with LQTS impair Ca2+ channel–dependent inactivation and induce accentuation in INaL and these effects have been demonstrated to prolong the plateau of the cardiac AP.22,26 At this time, the last type of LQTS identified is LQT17, associated with cardiac mutations in the TRDN gene encoding for the triadin protein,27 which is critical to the structure and functional regulation of cardiac muscle calcium release units and excitation-contraction coupling.155 It was speculated that a decrease in ICaL inactivation caused by loss of triadin could lead to prolonged cardiac AP and LQTS phenotype27; however, the precise molecular mechanism of how loss of triadin generates the LQT17 phenotype remains unknown. Furthermore, 2 case report studies suggested that mutations in the RyR2 gene that encode the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channel may play a role in LQTS.156,157 Additionally, findings indicate an association in patients with prolonged QT with deleterious mutations in the SCN10A gene encoding the voltage-gated pore-forming α subunit of NaV1.8.158 Thus, possibly RyR2 and SCN10A gene mutations will be part of less frequent LQTS-associated genes. Screening and early detection of prolonged QT remains a central approach for risk stratification and primary prevention against fatal arrhythmias in affected subjects. Therefore, it remains essential to identify all genetic causes in LQTS.

LQTS diagnosis

The diagnosis of LQTS has traditionally relied on the demonstration of prolonged QTc interval as well as the use of a clinical scoring system (Schwartz score) that incorporates surface ECG findings with patient and family histories that include symptoms of syncope, seizures, or aborted cardiac arrest and/or SCD.1,159 Although the typical LQTS cases present no diagnostic difficulty, the diagnosis is particularly challenging in asymptomatic LQTS patients, because the Schwartz criteria rely on the presence of symptoms and QT prolongation1; consequently, borderline cases are more complex to diagnose.160 The fact that cardiac events are more often associated with sympathetic stimulation (physical or emotional stress) forms the basis of different provocative tests to uncover concealed LQTS.161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171 Therefore, in order to further improve identification of LQTS and to augment the diagnostic sensitivity to further unmask concealed LQTS, different solutions have been proposed: heart rate dependent of QT interval,161 mental stress test,162 standing response,163 sympathetic stimulation,164, 165, 166,171 and exercise test.167, 168, 169, 170 Additionally, the use of provocative drug challenges with epinephrine can be used to facilitate diagnosis.

Moreover, since multiple genes have been implicated in LQTS, clinical genetic testing has now become more commonly performed to identify the causative rare variant.9,10,12 The clinical value of genetic testing has been demonstrated by the evidence that carriers of LQTS mutations lacking QT interval prolongation, who therefore escape clinical diagnosis, have a 10% risk of major cardiac events by age 40 when left untreated.172 This is where the involvement of a clinical geneticist can play a key role. Indeed, the consequences of missing the LQTS diagnosis in a genetically affected individual or family member with a normal QTc can literally become a question of life or death. In a genotype-positive family, especially with a history of sudden death, it becomes essential for a clinical geneticist to get involved to provide counseling on genetic testing and consequence of the outcome, especially for asymptomatic individuals. This is impactful, since asymptomatic individuals without the knowledge of their genetic predisposition will not receive treatment, will not be aware of the risk of transmitting LQTS to offspring, and will not be informed about avoiding environmental risk factors, such as QT-prolonging drugs, strenuous physical exercise, and extreme psychological stress.12

LQTS therapeutic interventions

LQTS treatments are targeted at (1) reducing symptomatic arrhythmias, (2) preventing life-threatening arrhythmic events, and (3) reducing SCD risk.2,173 Evidence for a major role of the SNS in triggering cardiac events in most LQTS patients provided the rationale for antiadrenergic interventions.58,174 In general, congenital LQTS management strategies are similar, independent of the LQTS genotype.2,173 The international guidelines advise universal beta-blocker therapy as the drug treatment of choice for LQTS patients who are class I (symptomatic or QTc ≥ 470 ms) or class II (asymptomatic with QTc ≤ 470 ms).2,173 Beta-blockers are indeed very effective, but some LQTS patients continue to have arrhythmic recurrences despite the therapy. Thus, in these patients other management strategies are recommended, such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), left cardiac sympathetic denervation, and sodium channel blockers, which can be useful as an add-on therapy for LQT3 patients with a QTc > 500 ms.2,173 Table 3 presents the international ESC and HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus guidelines on management and recommendations for LQTS patients.2,173

Table 3.

Risk stratification and management in long QT syndrome

| Class | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Class I |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Class IIa |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Class III |

|

Adapted from references Priori et al 2013 and Priori et al 2016.

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LCSD = left cardiac sympathetic denervation; LQTS = long QT syndrome.

An essential component of comprehensive LQTS management is recognizing that clinical expressivity is variable, with some patients having concealed and asymptomatic disease with minimal to no LQTS expressivity, in contrast to those with malignant LQTS. A study has shown that in a highly select group of LQTS patients with clinical profile that includes asymptomatic status, older age at diagnosis, and QTc < 470 ms, an observation-only/intentional nontreatment strategy can be considered for very low-risk patients with LQTS after careful clinical evaluation, risk assessment, and institution of prudent precautionary measures such as QT-prolongation drug avoidance. The study showed that such low-risk patients could obtain excellent outcomes without the side effects associated with beta-blockers.175 The authors of the study suggested that LQTS patients with this low-risk profile should not receive a prophylactic ICD and that among highly select patients, even guideline-recommended/guideline-supported beta-blocker therapy may be unnecessary; and in such patients, an intentional nontherapy strategy can be considered.175

Moreover, in contrast to LQT1 and LQT2 patients, the use of beta-blocker therapy in LQT3 patients has been more controversial. LQT3 phenotype differs from the more common LQTS. Indeed, LQT3 patient triggers for cardiac events are less likely to be adrenergic and appear to be predominantly bradycardia related.58,59 Nevertheless, it was found that beta-blocker therapy was associated with an 83% reduction in cardiac events in LTQ3 female patients but the efficacy in male patients could not be determined conclusively because of the low number of events.141 Furthermore, a meta-analysis on the efficacy of beta-blockers in LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3 showed that beta-blockers were effective in reducing risks of cardiac events in LQT1 and LQT2 patients but was not able to provide a conclusive statement on the role of beta-blockers on LQT3 owing to data insufficiency.176

However, a recent study aimed at creating an evidence-based risk stratification scheme to personalize the quantification of the arrhythmic risk in patients with LQTS showed that the estimated risk of life-threatening arrhythmia events increases by 15% for every 10 ms increment in the QTc durations for all genotypes, while intergenotype comparison showed that the risk for patients with LQT2 and LQT3 increased by 130% and 157% at any QTc durations vs patients with LQT1. Additionally, the study demonstrated the superiority of the beta-blocker nadolol in significantly reducing arrhythmic risk in all genotypes, compared with no therapy.177 Furthermore, the authors of the study provided a novel model to estimate a 5-year risk of life-threatening arrhythmic events in beta-blocker-naïve patients with LQTS. This study highlighted the clinical relevance of the model, since it enables discussion with patients for their therapeutic options based on a personalized estimate of the 5-year likelihood for life-threatening arrhythmia events when treatment with beta-blockers is refused or adopted with poor compliance.177

Moreover, the concept of inhibiting INaL or of using different NaV1.5 channel blockers in LQT3 patients has been explored. Lidocaine, mexiletine, and flecainide, which have varying selectivity for INaL over peak INa178, 179, 180, and ranolazine, a more specific INaL inhibitor,181,182 have been tested. However, the enthusiasm to treat LQT3 patients with NaV1.5 channel blockers has been taken very carefully because of the potential adverse effects of this approach owing to potential simultaneous blockade of the peak INa leading to loss-of-function phenotype similar to BrS.146,178 In addition, some NaV1.5 channel blockers may facilitate trafficking of mutant NaV1.5 channel, thus exacerbating QT prolongation.153 Moreover, owing to nonspecific effects, blockade of 1 of the repolarizing potassium currents may result in further prolongation of the APD. Nevertheless, a clinical benefit was observed in some LQT3 patients owing to pharmacological INaL inhibition.178, 179, 180, 181, 182

LQTS genotype-phenotype discordance and single nucleotide polymorphisms

The availability of genetic testing provides and important opportunity to identify and deliver prophylactic treatments to genotype-positive individuals at risk for potential fatal cardiac arrhythmias. However, it has become more and more evident that a mutation in the LQTS-susceptible genes often fails to predict the clinical phenotype, even between members of the same family carrying the same disease-causing mutation. Some genotype-positive patients never develop a clinically relevant disease, some remain asymptomatic (incomplete penetrance), and some show QTc prolongation without cardiac events, whereas others are severely affected and experience serious cardiac events at an early age (variable expressivity).4,183 This variation may indicate the presence of significant environmental factors or genetic modifiers, such as common genetic variants of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in the same or a different gene, which can modulate the functional effect of LQTS mutations and therefore can either exacerbate or mitigate the final LQTS phenotype184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194 (Table 4). SNPs can act either independent of or in concert with the LQTS-causing mutation.195 Thus, in addition to the increased interest in genetic investigations of LQTS in general, study focused on identifying the role of SNP over the vastly different clinical course of LQT patients is rising steadily.190,196, 197, 198, 199 Moreover, efforts to develop systematic detection of SNP assays has similarly been intensified.200,201

Table 4.

Common variants associated with the QTc duration

| Locus | Gene | SNP | MAP | Location | Function | QTc Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q | NOS1AP | rs12143842 | 0.16 | Intergenic | Nitric oxide synthase 1 adaptor protein | ↑ |

| rs2880058 | 0.26 | Intergenic | ↑ | |||

| rs10494366 | 0.33 | Intron | ↓ | |||

| rs12029454 | 0.11 | Intron | ↑ | |||

| rs16857031 | 0.15 | Intron | ↑ | |||

| rs4657178 | 0.18 | Intron | ↑ | |||

| 1q | ATP1B1 | rs10919071 | 0.11 | Intron | β-subunit Na+/K+ATPase | ↑ |

| 1p | RNF207 | rs846111 | 0.26 | 3’UTR | Ring finger protein | ↑ |

| 3p | SCN5A | rs11129795 | 0.34 | Intergenic | α-subunit INa | ↓ |

| rs12053903 | 0.29 | Intron | ↓ | |||

| rs1805124 | 0.18 | Exon (H558R) | ↑ | |||

| 6q | C6orf204 | rs12210810 | 0.08 | Intergenic | Phosphorylation | ↓ |

| rs11970286 | 0.47 | Intergenic | ↑ | |||

| 7q | KCNH2 | rs2968863 | 0.26 | Intergenic | α-subunit IKr | ↓ |

| rs4725982 | 0.18 | Intergenic | ↑ | |||

| rs1805123 | 0.24 | Exon (K897T) | ↑↓ | |||

| 11p | KCNQ1 | rs12296050 | 0.23 | Intron | α-subunit IKs | ↑ |

| rs12576239 | 0.16 | Intron | ↑ | |||

| rs2074238 | 0.08 | Intron | ↓ | |||

| 12q | TBX5 | rs3825214 | 0.22 | Intron | Transcription | ↑ |

| 13q | SUCLA2 | rs2478333 | 0.35 | Intergenic | Mitochondrial enzyme | ↑ |

| 16p | LITAF | rs8049607 | 0.49 | Intergenic | Tumor necrosis factor | ↑ |

| 16q | CNOT1 | rs37062 | 0.27 | Intron | RNA transcription | ↓ |

| 17q | KCNJ2 | rs17779747 | 0.32 | Intergenic | α-subunit IK1 | ↓ |

| 17q | LIG3 | rs2074518 | 0.49 | Intron | DNA ligase III | ↓ |

| 21q | KCNE1 | rs1805128 | 0.03 | Exon | β-subunit IKs | ↑ |

MAP = minor allele frequency; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

Adapted from reference Amin et al 2013.

Symbols are as follows:

↑ QTc prolongation,

↓ QTc shortening.

novel strategies to study ion channel dysfunction and drug-specific therapies in LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3 syndromes

The challenges for clinicians reside in the ability to make an early diagnosis, identify LQTS patients at lower vs higher risk of cardiac events, determine the appropriate therapy, and identify LQTS patients displaying incomplete penetrance with different clinical phenotypes (SCD, syncope, asymptomatic). Incomplete penetrance, which is relatively frequent in LQTS, may be caused by more complex genetic models involving multiple genetic and environmental factors affecting the disease development, which represents a challenge for diagnosis and obstacles for the implementation of successful proactive treatments.

Human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes

The human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocyte (hiPSC-CM)-based models have been considered a new paradigm for the development of precision therapeutics that target specific disease mechanisms, personalized drug screening, and exploration of gene therapy through genome editing. In this context, multiple groups including ours have started to investigate and identify factors—either genetic, pharmacological, or environmental—able to modify the clinical course for LQTS patients by acting as modifiers of genes and/or of protein function, expression, or regulation using the hiPSC-CM system.

Our group, in a synergistic manner pairing 3 emergent technologies using hiPSC-CMs, next-generation exome sequencing, and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, identified contributors to variable expressivity in an LQT2 family. Our strategy was to first generate iPSC-CM from close symptomatic and asymptomatic relatives, all hERG mutation carriers. We first validated that the genotype-phenotype could be observed by measuring their APs, demonstrating that the phenotype is cell autonomous. Surprisingly, full electrophysiological characterization showed that the affected individuals presented with an increase in calcium currents, which could explain the severe phenotype in these individuals. In parallel, through exome sequencing, we identified variants explaining the genotype-phenotype discordance in this family, which were then validated through CRISPR/Cas9. Importantly, our findings highlighted the power of combining complementary physiological and genomic analyses to identify genetic modifiers and potential therapeutic targets of monogenic disorders. Furthermore, our study proposed that this strategy can be deployed to unravel myriad confounding pathologies displaying variable expressivity.202 Furthermore, a similar study aimed at determining functional differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic hERG mutation carriers from the same family using iPSC-CM showed that when comparing asymptomatic and symptomatic single hiPSC-CMs, allelic imbalance, potassium current density, and arrhythmicity on adrenaline exposure were similar, but a difference in Ca2+ transience was observed. However, the major difference observed by the authors was in hiPSC-CMs at the aggregate level, where increased susceptibility to arrhythmias was observed on aggregate hiPSC-CMs derived from the symptomatic patient. The authors of the study suggested the importance of considering the clinical differences in phenotypes observed in single and aggregate hiPSC-CMs, particularly when conducting preclinical drug toxicity tests.203

Moreover, patient-independent hiPSC-CM models combined with CRISPR/Cas9-genome editing have also been used to validate the pathogenicity of “variants of unknown significance” (VUS).204 Furthermore, hiPSC-CMs have also been used to identify complex aberrant messenger RNA variants and recapitulated the clinical phenotype of patients with concealed LQT1 syndrome.205 Overall, hiPSC-CMs have been widely used for LQTS modeling and also as a powerful tool for understanding LQTS disease molecular and cellular mechanisms, as well as to determine in a patient-specific manner drug treatment screening.206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212 The use of this hiPSC-CM model has really allowed for major advancement in the study of LQTS in the last few years and will continue to be the ideal platform to study these cardiac genetic diseases, as they allow for the use of cells containing the whole genetic background of the patients.

High-throughput characterization of LQTS genetic variants

To date, many KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A variants have been discovered in LQTS, and with the onset of large population sequencing projects and increase in clinical genetic testing, the number of observed KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A variants is rapidly growing, albeit at a much faster rate than the detailed characterization of these variants. Consequently, an important challenge is the identification and characterization of potentially disease-causing KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A variants found in LQTS individuals with or without a clinical phenotype. Therefore, to overcome this challenge, researchers have been designing accurate high-throughput strategies that allow to distinguish between VUS that are disease-causing mutations and those that are benign variants. Knowing this information will have enormous implications for the diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and family counseling of LQTS patients.

The combination of high-efficiency cell electroporation and automated planar patch-clamp is a novel strategy being used to determine in a high-throughput platform the functional consequences of genetic variants. This strategy has been used for the KCNQ1 gene, promoting data-driven variant classification of a large number of variants and creating new opportunities for precision medicine.213 Furthermore, in a parallel study the same group of researchers used medium-throughput channel trafficking and stability studies combined with channel functional data to assess KCNQ1 variants’ functional and biochemical consequences and to determine their pathogenic mechanisms. The authors of the study discussed the benefits of identifying which KV7.1 loss-of-function mechanism pertains to a given patient. They demonstrated that the appropriate therapeutic approach for a patient with KCNQ1 that traffics normally but has defective channel properties is likely to be different from that of a patient with a KCNQ1 variant that is prone to mistraffic, but may be functional if it reaches the plasma membrane.45 Similarly, a new method combining high-throughput assessment of single variants through flow cytometry, confocal microscopy and planar patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to detect KV11.1 trafficking–defective channels. The authors of this study generated trafficking scores for KCNH2 variants. This assay has the potential to sample all possible amino acids substitution in KCNH2 variants in an unbiased manner, providing a database for patients and clinicians to identify the effect of a previously uncharacterized mutation on patient disease propensity.214 Another strategy put forward was to use high-throughput patch-clamp together with surface enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, which allowed to distinguish between KCNH2 benign, dominant-negative, or haploinsufficient variants, helping with KCNH2 variant classification.215 Additionally, to test specific treatments for potential variants, pharmacological or temperature strategies were used in combination with high-throughput platforms and showed the enormous potential of these new methods to determine a patient-specific therapy treatment.216

High-throughput patch-clamp has also been used to determine VUS pathogenicity in SCN5A-related BrS variants.217 However, although the use of high-throughput patch-clamp to accurately measure INaL and determine VUS pathogenicity on LQT3 variants represents a bigger challenge, scientists will likely overcome this in the future to measure INaL of SCN5A variants on a large scale. Nevertheless, the determination of VUS pathogenicity of SCN5A-related BrS variants is highly relevant to LQT3 patients owing to the sometime coexistence of LQT3 and BrS mixed phenotypes.143,146 Additionally, the accuracy of the high-throughput assay “Deep Mutation Scanning” in SCN5A was validated and identified gain-of-function and loss-of-function pathogenic variants.218 Together, these methodologies will help with the identification and characterization of potentially disease-causing variants, hopefully at a faster pace than variants being identified.

Development of drug-specific therapy

The use of hiPSC-CM-based models for the development of precision therapeutics is a powerful and growing tool. McKeithan and colleagues219 recently described the use of high-throughput physiological screening for arrhythmic phenotypes in hiPSC-CMs derived from patients with LQT3. Their goal was to facilitate the rapid chemical refinement of mexiletine in order to improve its therapeutic potential and reduce toxicity. The authors of the study identified mexiletine analogues with increased potency and selectivity for inhibiting INaL across a panel of 7 LQT3 variants and were able to suppress arrhythmia activity across multiple genetic and pharmacological hiPSC-CM models of LQT3 with diverse backgrounds. The authors of the study highlighted the potential of the mexiletine analogues as mechanistic probes to improve therapeutic potential and reduce toxicity. Another study was aimed at understanding the molecular basis of LQT3 patients’ variable response to mexiletine. In that study, the authors built a predictive model that can be used for personalized mexiletine treatments based on patients’ genetic variants. They found that mexiletine altered the conformation of domain III voltage sensor domain. Based on this new understanding of the molecular mechanisms for mexiletine blockade of NaV1.5 channels, the authors generated a system-based model on a dataset of 32 patients and were able to successfully predict the response of 7 out of 8 LQT3 patients to mexiletine in a blinded retrospective trial. These findings emphasized that patient-specific response to mexiletine can be predicted, which can certainly improve therapeutic decision making.220

An additional challenge with developing drugs that block INaL is that they can act on many other targets, such as other channels (especially hERG channel, IKr) or receptors, resulting in side effects and/or safety concerns. Thus, new drugs have been under development for clinical use. These drugs should have greater potency, efficacy, and selectivity to inhibit INaL without inhibiting IKr and/or prolonging the QT interval. In addition, the drug should not reduce either peak INa or cardiac contractility function. In this context, studies have been focusing on developing next-generation Na+ channel inhibitors that will exhibit increased selectivity for INaL and fulfill all safety concerns.221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226

The current treatment for LQT2 patients is aimed at reducing the incidence of arrhythmia triggers with beta-blockers or terminating the arrhythmia after onset with ICD. However, studies have also considered the alternative strategy of targeting the underlying disease mechanism, which is IKr reduction. Consequently, small molecules have been identified that either enhance KV11.1 expression (enhancers)227,228 or modify KV11.1channel function (activators).229 In this context, different groups assessed shortening of APD in LQT2 hiPSC-CMs using pharmacological tools principally by increasing IKr, but also by testing enhancement of the K+ current IKATP.227, 228, 229, 230 Moreover, it has been shown that KV11.1 channel activators, which target the primary disease mechanism, provide a possible treatment option for LQT2, with the caveat that there may be a risk of overcorrection that could itself be proarrhythmic.231

The novel drug lumacaftor (LUM), a recently FDA-approved cystic fibrosis (CF) protein trafficking chaperone, was used by Mehta and colleagues228 in LQT2 hiPSC-CMs as a potential novel therapy for LQT2 patients. The first attempt to validate the repurposing strategies for cardiovascular disorders showed that LUM+ivacaftor significantly shortened QTc in the 2 same LQT2 patients with trafficking defect whose hiPSC-CMs were used to study the response to LUM in the study by Mehta and colleagues, confirming the findings.228,232 In their conclusion, the authors mentioned that while the findings are encouraging they cautioned that immediate translation into clinical practice, without validation in more patients, would be premature.232 Furthermore, while LUM is an effective hERG channel trafficking chaperone and may be a therapeutic option for LQT2, caution for its potential use and the importance of understanding the functionality of the LQT2 mutant to be rescued were emphasized by the findings that LUM therapy could also be harmful. Indeed, it was shown that following LUM treatment an alarming increase in the APD was observed in hiPSC-CMs carrying the pG604S hERG mutation.233 Therefore, these studies highlight the importance of understanding LQT2 patients’ mutant-specific functional characteristics in order to be able to design a patient-specific treatment. Remarkably though, the hiPSC-CM model system provides a very useful system for evaluating rescue as well as side effects of potential therapies for LQTS patients.

Another strategy that was recently explored to rescue ion channel trafficking focused on ubiquitination. This was tested with an engineered deubiquitinase that enables selective ubiquitin chain removal from target proteins to rescue the functional expression of trafficking defective ion channels that underlie either LQT1 or CF.234 The authors of the study showed that targeted deubiquitination via engineered deubiquitinases provides a powerful protein stabilization method that not only corrects diverse disease caused by impaired ion channel trafficking (LQT1 and CF), but also introduces a new tool for deconstructing the ubiquitin code in situ.234

Conclusion

Altogether, hundreds of LQTS mutations are found in KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A genes. Yet even within 1 gene, the mutations present with different mechanisms and different severity, and even more importantly, variability is also seen for the same mutation among different patients. This variability presents an extraordinary challenge for the physician in determining the best treatment strategy for a specific LQTS patient. However, over the last few years tremendous advances in technologies have allowed characterization of mutations and identification of patient-specific therapies on a large scale. Indeed, the use of hiPSC-CMs, next-generation sequencing, high-throughput patch-clamping, and deep mutation scanning, just to name a few, are all relatively recent new approaches that have been applied to the study of LQTS, and we are starting to see the benefits by translating our findings from bench to bedside. While promising, at this point these novel strategies to study ion channel function and investigation into drug-specific therapies remain mainly limited to the bench and are not yet fully available for the clinician. But by combining multidisciplinary mechanism-based studies and approaches it will help in our understanding of underlying patient-specific abnormalities, and this information will be crucial to the diagnosis and implementation of successful treatments in LQTS patients, finally getting to precision medicine in LQTS in the near future.

Funding Sources

NIH/NHLBI 1R01HL094450 (ID) and AHA Career Development Award 20CDA35320040 (DPB).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authorship

All authors attest they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

References

- 1.Schwartz P.J., Moss A.J., Vincent G.M., Crampton R.S. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation. 1993;88:782–784. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priori S.G., Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Mazzanti A. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016;69:176. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Timothy K.W., Vincent G.M. Spectrum of ST-T-wave patterns and repolarization parameters in congenital long-QT syndrome: ECG findings identify genotypes. Circulation. 2000;102:2849–2855. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent G.M., Timothy K.W., Leppert M., Keating M. The spectrum of symptoms and QT intervals in carriers of the gene for the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:846–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209173271204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jervell A., Lange-Nielsen F. Congenital deaf-mutism, functional heart disease with prolongation of the Q-T interval and sudden death. Am Heart J. 1957;54:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser G.R., Froggatt P., Murphy T. Genetical aspects of the cardio-auditory syndrome of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen (congenital deafness and electrocardiographic abnormalities) Ann Hum Genet. 1964;28:133–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1964.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz P.J., Stramba-Badiale M., Crotti L. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1761–1767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler A., Novelli V., Amin A.S. An International, multicentered, evidence-based reappraisal of genes reported to cause congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2020;141:418–428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Splawski I., Shen J., Timothy K.W. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation. 2000;102:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tester D.J., Will M.L., Haglund C.M., Ackerman M.J. Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landstrom A.P., Shah S.H. Rare things being common: implications for common genetic variants in rare diseases like long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2020;142:339–341. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Napolitano C., Priori S.G., Schwartz P.J. Genetic testing in the long QT syndrome: development and validation of an efficient approach to genotyping in clinical practice. JAMA. 2005;294:2975–2980. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu G., Ai T., Kim J.J. Alpha-1-syntrophin mutation and the long-QT syndrome: a disease of sodium channel disruption. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:193–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.769224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Z., Wu C.Y.C., Jiang Y.P. Suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling and alteration of multiple ion currents in drug-induced long QT syndrome. Science Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003623. 131ra50–131ra50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohler P.J., Splawski I., Napolitano C. A cardiac arrhythmia syndrome caused by loss of ankyrin-B function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:9137–9142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402546101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splawski I., Timothy K.W., Sharpe L.M. Ca(V)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y., Yang Y., Liang B. Identification of a Kir3.4 mutation in congenital long QT syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vatta M., Ackerman M.J., Ye B. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2006;114:2104–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueda K., Valdivia C., Medeiros-Domingo A. Syntrophin mutation associated with long QT syndrome through activation of the nNOS-SCN5A macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9355–9360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801294105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Villiers C.P., van der Merwe L., Crotti L. AKAP9 is a genetic modifier of congenital long-QT syndrome type 1. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:599–606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plaster N.M., Tawil R., Tristani-Firouzi M. Mutations in Kir2.1 cause the developmental and episodic electrical phenotypes of Andersen's syndrome. Cell. 2001;105:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pipilas D.C., Johnson C.N., Webster G. Novel calmodulin mutations associated with congenital long QT syndrome affect calcium current in human cardiomyocytes. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:2012–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed G.J., Boczek N.J., Etheridge S.P., Ackerman M.J. CALM3 mutation associated with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohler P.J., Schott J.J., Gramolini A.O. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature. 2003;421:634–639. doi: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaix M.A., Koopmann T.T., Goyette P. Novel CALM3 mutations in pediatric long QT syndrome patients support a CALM3-specific calmodulinopathy. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2016;2:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boczek N.J., Gomez-Hurtado N., Ye D. Spectrum and prevalence of CALM1-, CALM2-, and CALM3-encoded calmodulin variants in long QT syndrome and functional characterization of a novel long QT syndrome-associated calmodulin missense variant, E141G. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9:136–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altmann H.M., Tester D.J., Will M.L. Homozygous/compound heterozygous triadin mutations associated with autosomal-recessive long-QT syndrome and pediatric sudden cardiac arrest: elucidation of the triadin knockout syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131:2051–2060. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohnen M.S., Peng G., Robey S.H. Molecular pathophysiology of congenital long QT syndrome. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:89–134. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roden D.M., Balser J.R., George A.L., Jr., Anderson M.E. Cardiac ion channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:431–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.083101.145105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schram G., Pourrier M., Melnyk P., Nattel S. Differential distribution of cardiac ion channel expression as a basis for regional specialization in electrical function. Circ Res. 2002;90:939–950. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018627.89528.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bers D.M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barhanin J., Lesage F., Guillemare E., Fink M., Lazdunski M., Romey G.K.(V. LQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the I(Ks) cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanguinetti M.C., Curran M.E., Zou A. Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang M., Wang Y., Tseng G.N. Adult ventricular myocytes segregate KCNQ1 and KCNE1 to keep the IKs amplitude in check until when larger IKs is needed. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jost N., Virag L., Bitay M. Restricting excessive cardiac action potential and QT prolongation: a vital role for IKs in human ventricular muscle. Circulation. 2005;112:1392–1399. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.550111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiener R., Haitin Y., Shamgar L. The KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) COOH terminus, a multitiered scaffold for subunit assembly and protein interaction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5815–5830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamgar L., Ma L., Schmitt N. Calmodulin is essential for cardiac IKS channel gating and assembly: impaired function in long-QT mutations. Circ Res. 2006;98:1055–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218979.40770.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendahhou S., Marionneau C., Haurogne K. In vitro molecular interactions and distribution of KCNE family with KCNQ1 in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundquist A.L., Manderfield L.J., Vanoye C.G. Expression of multiple KCNE genes in human heart may enable variable modulation of I(Ks) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinel N., Diochot S., Borsotto M., Lazdunski M., Barhanin J. KCNE2 confers background current characteristics to the cardiac KCNQ1 potassium channel. EMBO J. 2000;19:6326–6330. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melman Y.F., Domenech A., de la Luna S., McDonald T.V. Structural determinants of KvLQT1 control by the KCNE family of proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6439–6444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J., Zheng R., Melman Y.F., McDonald T.V. Functional interactions between KCNE1 C-terminus and the KCNQ1 channel. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loussouarn G., Park K.H., Bellocq C., Baro I., Charpentier F., Escande D. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2, controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K+ channels. EMBO J. 2003;22:5412–5421. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J., Liu Z., Creagh J., Zheng R., McDonald T.V. Physical and functional interaction sites in cytoplasmic domains of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 channel subunits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H212–H222. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00459.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang H., Kuenze G., Smith J.A. Mechanisms of KCNQ1 channel dysfunction in long QT syndrome involving voltage sensor domain mutations. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaar2631. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Splawski I., Tristani-Firouzi M., Lehmann M.H., Sanguinetti M.C., Keating M.T. Mutations in the hminK gene cause long QT syndrome and suppress IKs function. Nat Genet. 1997;17:338–340. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schulze-Bahr E., Wang Q., Wedekind H. KCNE1 mutations cause jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:267–268. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y., Zaydman M.A., Wu D. KCNE1 enhances phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) sensitivity of IKs to modulate channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9095–9100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100872108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park K.H., Piron J., Dahimene S. Impaired KCNQ1-KCNE1 and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate interaction underlies the long QT syndrome. Circ Res. 2005;96:730–739. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161451.04649.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marx S.O., Kurokawa J., Reiken S. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science. 2002;295:496–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1066843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McConnachie G., Langeberg L.K., Scott J.D. AKAP signaling complexes: getting to the heart of the matter. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Efendiev R., Dessauer C.W. A kinase-anchoring proteins and adenylyl cyclase in cardiovascular physiology and pathology. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:339–344. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821bc3f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terrenoire C., Houslay M.D., Baillie G.S., Kass R.S. The cardiac IKs potassium channel macromolecular complex includes the phosphodiesterase PDE4D3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9140–9146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805366200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y., Chen L., Kass R.S., Dessauer C.W. The A-kinase anchoring protein Yotiao facilitates complex formation between adenylyl cyclase type 9 and the IKs potassium channel in heart. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29815–29824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L., Marquardt M.L., Tester D.J., Sampson K.J., Ackerman M.J., Kass R.S. Mutation of an A-kinase-anchoring protein causes long-QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20990–20995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710527105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bottigliero D., Monaco I., Santacroce R. Novel AKAP9 mutation and long QT syndrome in a patient with torsades des pointes. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2019;56:171–172. doi: 10.1007/s10840-019-00606-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]