Summary

Controlling cell fate has great potential for regenerative medicine, drug discovery, and basic research. Although transcription factors are able to promote cell reprogramming and transdifferentiation, methods based on their upregulation often show low efficiency. Small molecules that can facilitate conversion between cell types can ameliorate this problem working through safe, rapid, and reversible mechanisms. Here, we present DECCODE, an unbiased computational method for identification of such molecules based on transcriptional data. DECCODE matches a large collection of drug-induced profiles for drug treatments against a large dataset of primary cell transcriptional profiles to identify drugs that either alone or in combination enhance cell reprogramming and cell conversion. Extensive validation in the context of human induced pluripotent stem cells shows that DECCODE is able to prioritize drugs and drug combinations enhancing cell reprogramming. We also provide predictions for cell conversion with single drugs and drug combinations for 145 different cell types.

Keywords: cell conversion, reprogramming, bioinformatics, small molecules

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

DECCODE method for identification of drugs that promote cell conversion

-

•

Predicts drugs that alone or in combination increase reprogramming efficiency

-

•

Validated for reprogramming of human fibroblast to hiPSCs

-

•

Treatment suggestions provided for 145 target cell types

In this article, Napolitano, Rapakoulia, and colleagues present DECCODE, a method for automatic identification of drugs that alone or in combination promote cell conversion and reprogramming. They validate the method for reprogramming of human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), and provide predicted treatments for conversion to 145 target cell types.

Introduction

Controlling cell fate has enormous potentials for regenerative medicine (Cohen and Melton, 2011), drug discovery (Avior et al., 2016), and cell-based therapy (Kikuchi et al., 2017). A milestone discovery by Yamanaka and colleagues, who induced human stem cells via genetic reprogramming of mature somatic cells using four transcription factors (TFs) (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006) (Takahashi et al., 2007), has recently revolutionized the field of stem cell biology. To date, numerous studies have revealed distinct sets of TFs that achieve or promote cell reprogramming (Soufi et al., 2015) and transdifferentiation (Rosa et al., 2018; Sekiya and Suzuki, 2011). However, these methods often suffer from low efficacy due to partly unknown barriers that need to be overcome for complete conversion (Smith et al., 2016).

Optimizing the reprogramming system using non-invasive approaches, such as small-molecule treatment is a promising strategy that may increase the reprogramming potential. The cellular effects of small-molecule treatment are often rapid, dose dependent, and reversible (Zhang et al., 2012), and have potential for in situ regeneration therapeutic interventions (Biswas and Jiang, 2016). Recently, several methods relying fully or partially on drug treatment to enhance cell conversion have emerged (Federation et al., 2014). Many of these use fibroblasts as the starting cell type, reprogrammed toward pluripotency (Hou et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2010) or transdifferentiated to specialized cell types, including neurons (Ladewig et al., 2012), endothelial cells (Sayed et al., 2015), pancreatic like cells (Zhu et al., 2016), cardiomyocytes (Cao et al., 2016), hepatocytes (Lim et al., 2016), or other cell types (Cheng et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016). Such studies provide a proof of principle for drug-based reprogramming, the exact mechanisms of which, however, are often poorly understood, making extensive trial-and-error unavoidable. Indeed, methods for identifying small-molecule candidates include either exhaustive screenings of drug libraries followed by marker gene readout (Li et al., 2013) or application of drugs known to modulate specific pathways involved in the desired lineage commitment (Federation et al., 2014). While these methods are promising, they are laborious and do not scale.

Whereas computational approaches to identify novel combinations of TFs to facilitate cell reprogramming have been developed and validated (Cahan et al., 2014; Rackham et al., 2016), no similar tools exist for small molecules. Here, we present a methodology to automatically identify small molecules that either alone or in combination enhance cell reprogramming and cell conversion. We analyzed 447 genome-wide expression profiles of untreated primary cells from the FANTOM5 project (Forrest et al., 2014) together with 107,404 transcriptional responses to small-molecule treatment from the LINCS project (Keenan et al., 2018) to identify small molecules that drive the cell transcriptional program toward the one of the desired lineage. We make the results available in an online tool named DECCODE (Drug Enhanced Cell COnversion using Differential Expression), that, when queried, returns the top compounds predicted to enhance conversion toward the desired cell type. We extensively validated DECCODE to identify single or combined small molecules enhancing reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). DECCODE is unbiased, as it does not rely on previous knowledge, and it can scale up to identify drugs to enhance cell conversion to any desired cell type. We make the results available in an online tool (available at the following: https://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/cellconv/), which, when queried, returns the top compounds predicted to enhance conversion toward a large collection of primary cell types.

Results

The DECCODE approach

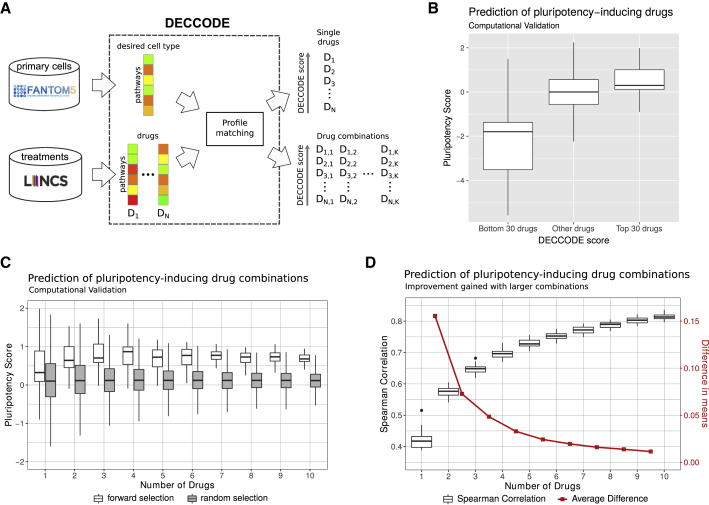

A schematic representation of our approach is illustrated in Figure 1A. Given a target cell type, we constructed its cell-type-specific differential gene expression profile using the FANTOM5 database (Noguchi et al., 2017), the most extensive atlas of gene expression profiles across primary human cells (Forrest et al., 2014), thus obtaining 447 expression profiles corresponding to 145 different cell types (see the supplementary methods). Specifically, the target cell-type expression profile was compared against the profiles of all the remaining cell types to detect differentially expressed genes specific to the target cell type. We then compared the target cell-type profile with drug-induced transcriptional profiles obtained from the LINCS database (GEO: GSE70138). LINCS contains 107,404 differential gene expression profiles corresponding to the transcriptional responses of 41 cell lines to 1,768 different drugs spanning different concentrations and time points, far exceeding any other publicly available resource of cellular perturbations (Keenan et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

Computational identification of drugs facilitating cell conversion

(A) Workflow of the DECCODE approach. Target cell profiles are constructed from the FANTOM5 collection of human primary cell samples. Drug-induced consensus profiles are created for each of the treated cell lines included in the LINCS database. Single drugs or drug combinations are then prioritized based on their similarity with the target cell-type profile.

(B) In silico validation of single drugs facilitating conversion to hiPSCs. Drugs are grouped by their DECCODE scores and the Pluripotency scores (PSs) of the drug-induced gene expression profiles within each group are computed and represented as a boxplot.

(C) In silico validation of drug combinations of increasing size facilitating conversion to hiPSCs. PSs for drugs within each of the top 30 combinations are compared with random sets of the same size (see supplemental experimental procedure for the details). Random selection was repeated 100 times.

(D) Improvement obtained when using drug combinations of increasing size. The Spearman correlation between predicted drug combination profiles and hiPSC profile as more drugs are added is reported in the boxplot. The red line highlights the difference between the means of subsequent sets.

Since FANTOM5 and LINCS use different expression profiling technologies, we first converted differential gene expression profiles in both datasets to differential pathway-based expression profiles (DPEPs) (Napolitano et al., 2018) (supplemental experimental procedure) to enable an integrative analysis over the two datasets. Subsequently, we generated a consensus profile for each drug by merging together DPEPs across different time points and dosages. Finally, given a cell type of interest, we searched among the 1,768 drugs that induce a transcriptional response similar to the expression profile of the target cell type. The underlying hypothesis is that the selected drugs will induce a change in gene expression in the starting cell type by making it more transcriptionally similar to the target cell type, and thus facilitating the cell conversion process.

We also developed an extension of this method to predict drug combinations that synergize to enhance cell conversion. In previous work, we showed that combinatorial drug treatment is effectively described by a linear combination of the individual drug responses (Rapakoulia et al., 2017) at the transcriptional level. The same finding has also been proven at the protein level, where protein dynamics in drug combinations can be explained by a linear superposition of their responses to individual drugs (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2010). After confirming that the linear relationship also holds at the pathway level (supplemental experimental procedure), we used a multivariable linear regression model to describe the combined effect of drug combinations. First, for each drug, we selected the profile having the highest DECCODE score across the treated cell lines, thus obtaining a single profile for each drug. Then we used forward selection to pick out the drug subsets yielding the most significant correlation with the target cell profile (supplementary methods).

Application of DECCODE to hiPSC conversion

We first applied DECCODE in the single-drug mode to identify drugs enhancing cell reprogramming to hiPSCs. We thus selected hiPSCs as the target cell type and DECCODE returned the list of all 1,768 drugs ranked according to their predicted efficacy in enhancing cell reprogramming. We performed Drug Set Enrichment Analysis (Napolitano et al., 2016) of the first 25 drugs in the ranking to identify those pathways that are consistently modulated by most of the drugs. As a result, we observed a consistent enrichment of pathways associated with pluripotency, such as differentiation and proliferation (Table S1).

To further assess the validity of the DECCODE score, we devised an in silico validation method based on assigning a Pluripotency score (PS) to each drug according to the upregulation of pluripotency-specific genes and downregulation of somatic-specific genes (supplemental experimental procedure). We then compared the DECCODE scores with the PSs. A clear trend can be observed with top-ranked (higher DECCODE scores) drugs exhibiting higher PSs, and bottom-ranked (lower DECCODE scores) drugs exhibiting lower PSs, whereas no obvious correlation existed in the middle-ranked profiles (Figure 1B). The full distribution of the DECCODE scores is reported in Figure S1A.

We then applied DECCODE in the drug combination mode to identify drugs that can jointly enhance reprogramming to hiPSCs. PS and predicted similarity to the hiPSC profile of the top 30 drug combinations significantly improved when increasing the number of drugs, as assessed by Spearman correlation and adjusted R2 values (Figures 1C, 1D, and S2A). However, we observed that the most significant improvement was achieved when adding just one additional drug and gradually decreased as we kept adding more drugs, eventually reaching a plateau. Akaike information criterion further confirmed that the relative goodness of fit increased more than what would be expected by chance as more drugs were added to the single-drug models (Figure S2B). The distribution of the transcriptional similarities between the two drug profiles in each of the top 30 drug pair combinations was compared with randomly chosen drug pairs (Figure S2C). The results indicated that the two selected drugs in each combination tend to be transcriptionally different. Taken together, these in silico results suggest that drug combinations may offer an increased capacity to promote reprogramming compared with single-drug administration.

Experimental validation of DECCODE for conversion to hiPSCs

We set out to experimentally validate predictions of DECCODE in both single-drug and drug combination mode applied to the hiPSCs reprogramming problem. As a biological model of reprogramming, we used human secondary fibroblasts harboring a doxycycline-inducible OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, C-MYC) gene cassette (hiF-T cells) (Cacchiarelli et al., 2015). For the single-drug case, we selected for experimental validation the top-ranked 25 drugs present in either of 2 widely used chemical screening libraries (supplemental experimental procedure) that were predicted by DECCODE to enhance the pluripotency transcriptional program. In addition, we selected 20 drugs with scores in the lower half of the total ranking for comparison. hiF-T cells were treated with a total of 45 drugs in triplicate. After 21 days of treatment, cells were stained for the pluripotency marker TRA-1-60, imaged, and cell colony number and area were quantified for each well (see example in Figure S1D). Increases in efficacy were difficult to detect by visual inspection due to the already highly efficient secondary reprogramming system used in the screening; however, the top-ranked drugs performed significantly better than the lower-ranked drugs, either when considering the number of colonies or the total area covered by the colonies (Figure 2A). Although some drugs with predicted low efficacy performed well in the screen, when ranked, the 45 tested drugs significantly correlated with the observed efficacy based on colony count and covered areas combined (Spearman ρ = 0.32, p = 0.033, see Figure S1B). Several top-ranked drugs have been already associated with enhancement of reprogramming (Table S2), including tranylcypromine, which we previously identified as a new positive regulator of the reprogramming process (Cacchiarelli et al., 2015). Another set of experimentally validated small molecules relevant for hiPSC generation reported in (Chen et al., 2020) (Table S3), which we analyzed as a whole, was also ranked significantly high by DECCODE (Kolmogorov-Smirnov D = 0.33, p = 9.36−3, see Figure S1E).

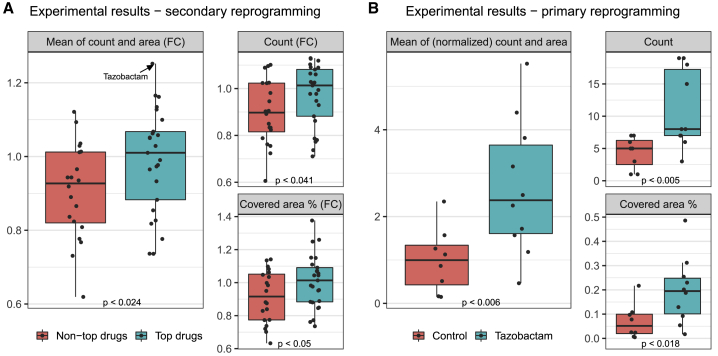

Figure 2.

Experimental validation of DECCODE to identify drugs that enhance conversion to hiPSCs

(A) Secondary reprogramming: fold change (FC) relative to controls of the number of colonies and their total area following treatment either with the 25 drugs ranked by DECCODE at the top of the ranking (green boxes) or with 20 drugs ranked in the bottom half of the ranking (red boxes). Dots represent the effect of individual drugs in terms of the average FC for three replicate experiments against controls. Main panel shows the combined average of both the number of colonies (count) and their area expressed as FCs; smaller panels report counts and areas separately.

(B) Primary reprogramming: number of colonies and percentage of their total area following treatment with tazobactam and OSKM compared with OSKM alone (control). Dots represent the single values for each replicate.

All p-values were obtained through single-tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

Tazobactam, an antibiotic of the beta-lactamase inhibitor class previously unexamined in the context of cell reprogramming, achieved the highest performance when considering the area covered by the colonies and the second highest performance when considering the number of colonies (Figures 2A and S1C), thus ranking first when considering both area and colony number together. Tazobactam was further validated by performing primary reprogramming of human primary foreskin fibroblasts through OSKM transduction either in the presence or absence of tazobactam. Both the number of colonies and the total area covered by the colonies confirmed the ability of tazobactam to enhance reprogramming to hiPSCs (Figure 2B).

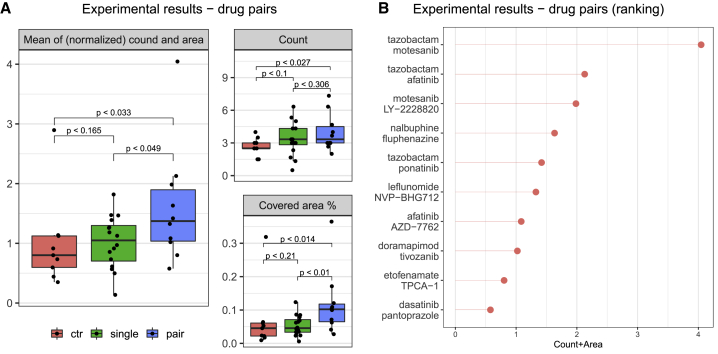

For validation of the drug combinations, we focused on the best drug pairs as ranked by DECCODE. In particular, from the ranked list of drug pairs, we chose the top eight combinations, including a sufficiently variant set of drugs and excluding those already proven not to be effective in single-drug experiments (supplemental experimental procedure). Finally, we experimentally tested the top eight pairs plus two additional top-ranked drug combinations which included tazobactam. The 10 final pairs included 16 different drugs, which were tested individually and in combinations using the same experimental setting as described previously. As shown in Figure 3A, the experimental results demonstrate a clear trend of increasing reprogramming efficacy from the untreated drugs to the single-drug treatments and from the single-drug treatments to the drug pair treatments. The two best performing drug pairs included tazobactam (Figure 3B), highlighting again the efficiency of the drug in reprogramming. The top pair, which is a combination of tazobactam and motesanib, showed a 4-fold performance improvement as compared with untreated cells.

Figure 3.

Experimental validation of DECCODE to identify drug combinations that enhance conversion to hiPSCs

(A) Number of colonies and total area obtained following treatment with the top 10 drug pairs as ranked by DECCODE (blue boxes), with each of the 16 drugs included in the 10 pairs (green boxes), and without drug treatment (red boxes). Dots represent the effects of individual samples for controls or average over triplicates for treatments. The main panel shows the combined outcome of both the number of colonies and area normalized against the respective control average; smaller panels report counts and areas separately.

(B) Reprogramming efficacy (colonies count and area) of the drug combinations tested.

All p-values were obtained through single-tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

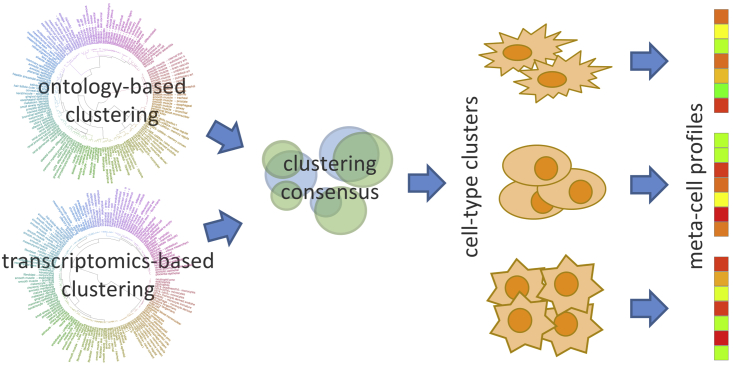

To create a comprehensive resource for drug-assisted cell conversions, we applied DECCODE to the whole FANTOM5 set of primary cells. We observed that closely related cell types exhibit high transcriptional similarity leading to tautological and nonspecific drug predictions. To reduce redundancy, we thus used a two-level hybrid clustering of cell types taking into consideration both knowledge-driven and data-driven similarities (Figure 4). In the first level, we applied the affinity propagation (Frey and Dueck, 2007) algorithm to cluster primary cells using either an ontological similarity (supplemental experimental procedures) or a transcriptional similarity, thus obtaining two different clusterings (Figure 4). For visualization purposes, we also performed a hierarchical clustering for both similarity measures (Figure S3). In the second level, cell types that were grouped together by both ontological and transcriptional clustering, were kept in one cluster, otherwise they were separated into distinct clusters. Finally, DPEPs of cell types in the same cluster were merged together to create a single consensus profile. We thus obtained 69 consensus DPEPs corresponding to distinct “meta-cells,” i.e., an ensemble of different cell types very similar in both ontological and transcriptional terms (the 69 meta-cell clusters are reported in Table S4).

Figure 4.

Two-level clustering to obtain cell-type-specific consensus profiles

We applied DECCODE to the 69 meta-cells profiles and found several drugs experimentally proved to facilitate cell conversions among the top 5% of ranked drugs (Table S5). Of note, 2 small molecules (Y-27632 and PD0325901) that were ranked among the top 20 candidates for conversion into the neuronal cell type were previously experimentally proven to promote neural conversion. Y-27632, a ROCK inhibitor that assists in neuron survival, was used in combination with six other small molecules to convert human fibroblasts into neuronal-like cells (Hu et al., 2015). PD0325901, a MEK-ERK inhibitor, facilitated the direct conversion of somatic cells to induced neuronal cells in a chemical cocktail of six compounds (Dai et al., 2015).

Our method has been pre-computed on 69 meta-cells representing all the primary cell types included in the FANTOM5 database, and the top single- and multi-drug predictions are publicly available through the DECCODE website (https://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/cellconv/) to provide an extensive resource that may support and complement future chemical enhanced cell conversion studies.

Discussion

Therapies based on cell reprogramming and conversion are becoming a reality (Mandai et al., 2017; Stoddard-Bennett and Reijo Pera, 2019) along with the need for methods that improve efficacy and safety of these processes. In the field of reprogramming and in general cell conversion, the genomic integrity and safety of the approach are often overlooked and difficult to globally evaluate. Maximizing the efficiency and speed is not only a means to improve the generation throughput of the cell of interest (particularly important in the case of conversion to non-replicating cells, such as neurons and hepatocytes) but also a means to bypass clonal expansion of subtypes resulting from of possible gain-of-function selections. The use of small molecules, rather than genetic factors, is a promising approach to address these issues. In addition to the ultimate goal of finding combinations that can fully convert one cell type to another, the identification of small molecules that can perform a partial conversion, or make the conversion more effective, also represents an important improvement on current methods. Here, we developed an unbiased method, DECCODE, which does not rely on expert knowledge of lineage-specific genes and pathways, scales to large numbers of cell conversions and drugs, and relies on publicly available data, thus not requiring massive screening efforts. Our method is the first validated computational approach for prioritizing small molecules promoting cell reprogramming. We have applied DECCODE to 145 human primary cell types from FANTOM5 and made the results available, providing a comprehensive resource, including both single drugs and combinations of two drugs predicted to facilitate conversion to a variety of cell types. Together with such resources, we also released the full automated pipeline used for colony quantification, including source code and high-resolution plate scans (Napolitano et al., 2020) (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3732772).

Although the number of gene expression profiles following drug treatment available in public databases is substantial, the number of unique small molecules profiled is not. Indeed, only a subset of small molecules that have been experimentally validated to facilitate cell conversions, were transcriptionally profiled in LINCS. Moreover, considering that many of the profiled agents are kinase inhibitors, relevant for cancer therapy, publicly available drug profile resources represent a small portion of the “druggable genome” in cell conversion applications. Future profiling efforts that include additional libraries of small molecules will increase the utility of our approach.

Since our method relies on the analysis of transcriptomic data, there are some restrictions regarding the small molecules that can be captured. For example, epigenetic modifiers, such as HDAC inhibitors are extensively used in cell conversions to tackle the epigenetic barriers between different types of cells. The broad action and the nonspecific transcriptional behavior (Chen et al., 2015) of these drugs limits their identifiability by DECCODE. In contrast, our approach gives priority to compounds exhibiting strong transcriptional regulation toward the target cell type. Looking forward, results from our validation experiments could be used in future studies to identify and weigh the most relevant but less transcriptionally evident pathways. On the other hand, it may be advisable to combine compounds identified in this study with treatment with epigenetic modifiers to further increase the efficacy of cell conversion.

Experiments on human fibroblasts confirmed the ability of DECCODE to predict single or combined small molecules facilitating cell reprogramming to iPSCs. Although we see no reason to believe that adding small molecules predicted by DECCODE to the reprogramming protocol would affect pluripotency in a negative way compared with other compounds in the reprogramming cocktails already present, full understanding of the efficacy of DECCODE for conversion to iPSCs, and other cell types, will require deep characterization of converted cells in terms of karyotype, pluripotency, and other relevant parameters. Deeper examination of reprogrammed cells may also reveal additional insights, as our validation experiments showed that increased efficacy was sometimes due to increased colony counts and at other times due to increased colony sizes, which may in turn be due to different drug treatments having different effects on processes, such as proliferation or reprogramming kinetics. The efficiency of reprogramming when treating cells with the best-ranked drugs was increased when compared with the control case and even more when using drug pairs. In the screening of high- and low-ranking drugs, a secondary reprogramming system highly optimized for hiPSC generation was used and, consequently, although statistically significant, the biological effects from drug treatment on colony formation were moderately strong and in many cases hardly visible by eye. Indeed, in the follow-up primary reprogramming experiment with tazobactam, the biological and statistical effects were considerably higher as this assay is less efficient.

The purpose of DECCODE is to provide a completely unbiased, data-driven approach to prioritize small molecules facilitating cell conversion. Alternative methods specialized for the case of specific cell types may also have utility. We used a knowledge-based approach, the PS, as an indication of the DECCODE performance, and indeed the PS itself, or other cell-type-specific transcriptional scoring approaches, may be useful in identifying suitable drug treatments for distinct target lineages. An unbiased method like DECCODE may identify different sets of molecules than more targeted methods. As an example, tazobactam, which proved to be effective in reprogramming, had a high DECCODE score and a low PS and consequently would have been missed by PS prioritization. Although this does not prove that the DECCODE score is superior to the PS in the particular case of iPSC reprogramming, it does provide evidence that DECCODE is complementary to knowledge-based approaches, and thus more generally applicable.

In summary, our work demonstrates that DECCODE is able to distinguish and prioritize small molecules based on their potential to promote reprogramming and its usefulness in facilitating cell conversion should not be underestimated. We identified the core reprogramming chemicals for each lineage commitment, which could aid in establishing the role of various small molecules in different cell fates. We made our results available via a user-friendly interface to facilitate the design of cell conversion experiments involving chemical compounds. Our method provides a significant head start toward the development of systematic chemical-based reprogramming strategies.

Experimental procedures

Gene expression data

We used untreated primary cell profiles from the FANTOM5 collection and drug-induced gene expression profiles from the LINCS collection. We selected all primary human cells having at least two biological replicates from the FANTOM5 database (http://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/data), resulting in 447 samples, which correspond to 145 different cell types. Expression tables of robust CAGE peaks for these samples were processed as follows: we kept only the promoters located within 500 bp of known RefSeq transcripts (87,400 promoters). We added read counts of all the promoters sharing the same Entrez id annotation, resulting in 18,980 genes (Figure S4A). Read counts of samples were converted in counts per million values and averaged across the same cell type. Z score normalization was applied to each gene across cell types to obtain differential expression profiles for each cell type. Subsequently, genes in every cell type were ranked according to their expression, from the most expressed to the least expressed gene.

LINCS database is available as gene-based expression profiles. We downloaded the fifth level of differential gene expression signatures released on the GEO website (GEO: GSE70138), which includes 107,404 profiles corresponding to 1,768 different drugs in 41 cell lines, 83 concentrations, and 4 treatment durations. Data access was performed through the cmapR package (Enache et al., 2019). Genes in each drug profile were ranked according to their expression, from the most upregulated to the most downregulated gene.

Single- and multi-drug DECCODE scores

We converted LINCS and target cell-type PEPs to ranks based on their enrichment score (from the most enriched to the least enriched pathway). Then, we ranked each LINCS PEP by computing its L1 distance from the target cell-type PEP:

where di is the LINCS PEP for drug i, i = 1, …, 17,259 (number of drug-induced PEPs), t is the target cell type PEP, p = 1, …, 250 (number of pathways in C2 collection). We finally converted the distance to the target cell type to a similarity measure:

For further analysis, we considered only the top-ranked profile for each small molecule, resulting in 1,768 profiles (number of unique small molecules). The DECCODE score ranges from 0 to 1, where a score close to 1 signifies a strong predicted similarity to the target profile, whereas a score close to 0 means no predicted similarity. Figure S1F shows the distribution of the top 30 DECCODE drug scores against all the 1,768 DECCODE scores for all meta-cell cluster profiles.

To produce DECCODE scores for drug combinations, we considered only the top-ranked PEP for each drug based on its L1 distance to the target cell type. For each drug PEP (1,768), we fitted a simple linear regression model and we ranked drugs based on the Spearman correlation between fitted and observed values. We picked the top 30 drug PEPs and searched through the remaining drugs to find out which one should be added to the current models to best improve the Spearman correlation. Repeated occurrences of the same drug sets in different order were discarded. We continued to add variables to the top 30 models until we reached 10 predictors. DECCODE multi-drug score in each step is the Spearman correlation between fitted and target PEPs.

Human cellular reprogramming

All the reprogramming experiments and procedures were performed as described previously (Cacchiarelli et al., 2015). In summary, secondary reprogramming was performed by seeding, on a confluent irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layer, clonal TERT-immortalized secondary fibroblasts (hiF-T) harboring a doxycycline-inducible OSKM cassette. The day after seeding reprogramming was initiated by doxycycline supplementation and protracted for 21 days. For primary reprogramming, BJ foreskin fibroblasts were infected with a lentivirus harboring the constitutive OSKM cassette (pLM-fSV2A) (Papapetrou et al., 2011) split onto an irradiated MEF feeder layer and reprogrammed for 15 days.

The secondary reprogramming experiment to test drug combinations was performed in sub-optimal conditions to allow easier identification of gain-of-function events. As the split of hiF-T at confluence above 60% deeply impinge the reprogramming efficiency, sub-optimal conditions were obtained by splitting cells only upon semi-confluency before reprogramming them, thus creating a reduction of reprogramming efficiency of at least 10 times, as evident by the reduced colony number. At the end of each reprogramming, quantitative analysis of colony number and area was performed using a TRA-1-60 chromogenic staining in bright field. All candidate drugs for reprogramming were tested for the entire duration of the reprogramming process at a final concentration of 10 nM in several technical or biological replicates, as indicated.

Data and code availability

DECCODE top single- and multi-drug predictions for 69 meta-cells are publicly available through the DECCODE website (https://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/cellconv/). The full automated pipeline used for colony quantification, including source code and high-resolution plate scans are available on (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3732772).

Author contributions

Data analysis was performed by F.N. and T.R. and supervised by X.G., D.d.B., and E.A. Additional analysis was performed by S.N. and A.I. Validation experiments were performed by P.A., L.V., and L.G.W., supervised by D.C. and D.L.M. The database and website were implemented by M.C. and A.H., and supervised by T.K. The manuscript was drafted by T.R., F.N., D.d.B., and E.A. with additional input from all other co-authors. The study was conceived by E.A. and jointly supervised by E.A., D.d.B., X.G., and D.C.

Acknowledgments

E.A. was supported by a Research Grant from MEXT to the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences. X.G. was supported by funding from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), under award number FCC/1/1976-18-01, FCC/1/1976-23-01, FCC/1/1976-25-01, FCC/1/1976-26-01, FCS/1/4102-02-01, REI/1/4216-01-01, and REI/1/4437-01-01. D.L.M. was supported by the Italian Telethon Foundation under project number TMDMCBX16TT. D.C. was supported by Fondazione Telethon Core Grant, Armenise-Harvard Foundation Career Development Award, European Research Council (grant agreement 759154, CellKarma), and the Rita-Levi Montalcini program from MIUR.

Published: April 22, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.028.

Contributor Information

Davide Cacchiarelli, Email: d.cacchiarelli@tigem.it.

Xin Gao, Email: xin.gao@kaust.edu.sa.

Diego di Bernardo, Email: dibernardo@tigem.it.

Erik Arner, Email: erik.arner@riken.jp.

Supplemental information

References

- Avior Y., Sagi I., Benvenisty N. Pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:170–182. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D., Jiang P. Chemically induced reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotent stem cells and neural cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:226. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacchiarelli D., Trapnell C., Ziller M.J., Soumillon M., Cesana M., Karnik R., Donaghey J., Smith Z.D., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Zhang X. Integrative analyses of human reprogramming reveal dynamic nature of induced pluripotency. Cell. 2015;162:412. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahan P., Li H., Morris S.A., Lummertz da Rocha E., Daley G.Q., Collins J.J. CellNet: network biology applied to stem cell engineering. Cell. 2014;158:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao N., Huang Y., Zheng J., Spencer C.I., Zhang Y., Fu J.-D., Nie B., Xie M., Zhang M., Wang H. Conversion of human fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by small molecules. Science. 2016;352:1216–1220. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Guo Y., Li C., Li S., Wan X. Small molecules that promote self-renewal of stem cells and somatic cell reprogramming. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020;16:511–523. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-09965-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.P., Zhao Y.T., Zhao T.C. Histone deacetylases and mechanisms of regulation of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2015;20:35–47. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.2015012997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Gao L., Guan W., Mao J., Hu W., Qiu B., Zhao J., Yu Y., Pei G. Direct conversion of astrocytes into neuronal cells by drug cocktail. Cell Res. 2015;25:1269–1272. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D.E., Melton D. Turning straw into gold: directing cell fate for regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:243–252. doi: 10.1038/nrg2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P., Harada Y., Takamatsu T. Highly efficient direct conversion of human fibroblasts to neuronal cells by chemical compounds. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2015;56:166–170. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.15-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache O.M., Lahr D.L., Natoli T.E., Litichevskiy L., Wadden D., Flynn C., Gould J., Asiedu J.K., Narayan R., Subramanian A. The GCTx format and cmap{Py, R, M, J} packages: resources for optimized storage and integrated traversal of annotated dense matrices. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1427–1429. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federation A.J., Bradner J.E., Meissner A. The use of small molecules in somatic-cell reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest A.R.R., Kawaji H., Rehli M., Baillie J.K., de Hoon M.J.L., Lassmann T., Itoh M., Summers K.M., Suzuki H., Daub C.O. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature. 2014;507:462–470. doi: 10.1038/nature13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey B.J., Dueck D. Clustering by passing messages between data points. Science. 2007;315:972–976. doi: 10.1126/science.1136800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva-Zatorsky N., Dekel E., Cohen A.A., Danon T., Cohen L., Alon U. Protein dynamics in drug combinations: a linear superposition of individual-drug responses. Cell. 2010;140:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou P., Li Y., Zhang X., Liu C., Guan J., Li H., Zhao T., Ye J., Yang W., Liu K. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Qiu B., Guan W., Wang Q., Wang M., Li W., Gao L., Shen L., Huang Y., Xie G. Direct conversion of normal and Alzheimer’s disease human fibroblasts into neuronal cells by small molecules. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan A.B., Jenkins S.L., Jagodnik K.M., Koplev S., He E., Torre D., Wang Z., Dohlman A.B., Silverstein M.C., Lachmann A. The library of integrated network-based cellular signatures NIH program: system-level cataloging of human cells response to perturbations. Cell Syst. 2018;6:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T., Morizane A., Doi D., Magotani H., Onoe H., Hayashi T., Mizuma H., Takara S., Takahashi R., Inoue H. Human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in a primate Parkinson’s disease model. Nature. 2017;548:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature23664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladewig J., Mertens J., Kesavan J., Doerr J., Poppe D., Glaue F., Herms S., Wernet P., Kögler G., Müller F.-J. Small molecules enable highly efficient neuronal conversion of human fibroblasts. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:575–578. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Casteels T., Frogne T., Ingvorsen C., Honoré C., Courtney M., Huber K.V.M., Schmitner N., Kimmel R.A., Romanov R.A. Artemisinins target GABAA receptor signaling and impair α cell identity. Cell. 2017;168:86–100.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Li K., Wei W., Ding S. Chemical approaches to stem cell biology and therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K.T., Lee S.C., Gao Y., Kim K.-P., Song G., An S.Y., Adachi K., Jang Y.J., Kim J., Oh K.-J. Small molecules facilitate single factor-mediated hepatic reprogramming. Cell Rep. 2016;15:814–829. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai M., Watanabe A., Kurimoto Y., Hirami Y., Morinaga C., Daimon T., Fujihara M., Akimaru H., Sakai N., Shibata Y. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:1038–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F., Sirci F., Carrella D., Di Bernardo D. Drug-set enrichment analysis: a novel tool to investigate drug mode of action. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:235–241. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F., Carrella D., Mandriani B., Pisonero-Vaquero S., Sirci F., Medina D.L., Brunetti-Pierri N., di Bernardo D. gene2drug: a computational tool for pathway-based rational drug repositioning. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1498–1505. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F., Rapakoulia T., Annunziata P., Hasegawa A., Cardon M., Napolitano S., Vaccaro L., Iuliano A., Wanderlingh L.G., Kasukawa T. 2020. Automatic Identification of Small Molecules that Promote Cell Conversion and Reprogramming—Plate Scans, Colony Quantification Scripts, and DECCODE Ranking. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi S., Arakawa T., Fukuda S., Furuno M., Hasegawa A., Hori F., Ishikawa-Kato S., Kaida K., Kaiho A., Kanamori-Katayama M. FANTOM5 CAGE profiles of human and mouse samples. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170112. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papapetrou E.P., Lee G., Malani N., Setty M., Riviere I., Tirunagari L.M.S., Kadota K., Roth S.L., Giardina P., Viale A. Genomic safe harbors permit high β-globin transgene expression in thalassemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:73–81. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackham O.J.L., Firas J., Fang H., Oates M.E., Holmes M.L., Knaupp A.S., Suzuki H., Nefzger C.M., Daub C.O., Shin J.W. A predictive computational framework for direct reprogramming between human cell types. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:331–335. doi: 10.1038/ng.3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapakoulia T., Gao X., Huang Y., De Hoon M., Okada-Hatakeyama M., Suzuki H., Arner E. Genome-scale regression analysis reveals a linear relationship for promoters and enhancers after combinatorial drug treatment. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3696–3700. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa F.F., Pires C.F., Kurochkin I., Ferreira A.G., Gomes A.M., Palma L.G., Shaiv K., Solanas L., Azenha C., Papatsenko D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaau4292. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed N., Wong W.T., Ospino F., Meng S., Lee J., Jha A., Dexheimer P., Aronow B.J., Cooke J.P. Transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to endothelial cells: role of innate immunity. Circulation. 2015;131:300–309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya S., Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Z.D., Sindhu C., Meissner A. Molecular features of cellular reprogramming and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:139–154. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soufi A., Garcia M.F., Jaroszewicz A., Osman N., Pellegrini M., Zaret K.S. Pioneer transcription factors target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming. Cell. 2015;161:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard-Bennett T., Reijo Pera R. Treatment of Parkinson’s disease through personalized medicine and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cells. 2019;8:26. doi: 10.3390/cells8010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Qin J., Wang S., Zhang W., Duan J., Zhang J., Wang X., Yan F., Chang M., Liu X. Conversion of human gastric epithelial cells to multipotent endodermal progenitors using defined small molecules. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li W., Laurent T., Ding S. Small molecules, big roles—the chemical manipulation of stem cell fate and somatic cell reprogramming. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:5609–5620. doi: 10.1242/jcs.096032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Li W., Zhou H., Wei W., Ambasudhan R., Lin T., Kim J., Zhang K., Ding S. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Russ H.A., Wang X., Zhang M., Ma T., Xu T., Tang S., Hebrok M., Ding S. Human pancreatic beta-like cells converted from fibroblasts. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10080. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

DECCODE top single- and multi-drug predictions for 69 meta-cells are publicly available through the DECCODE website (https://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/5/cellconv/). The full automated pipeline used for colony quantification, including source code and high-resolution plate scans are available on (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3732772).