Abstract

Background

The excessive consumption of free sugars, including fructose, is considered a cause of overweight and metabolic syndrome throughout the Western world. In Germany, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults (54%, 18%) and children (15%, 6%) has risen in the past few decades and has now become stable at a high level. The causative role of fructose is unclear.

Methods

This review is based on publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed and the Cochrane Library, with special attention to international guidelines and expert recommendations.

Results

The hepatic metabolism of fructose is insulin-independent; because of the lack of a feedback mechanism, it leads to substrate accumulation, with de novo lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis. Recent meta-analyses with observation periods of one to ten weeks have shown that the consumption of fructose in large amounts leads to weight gain (+ 0.5 kg [0.26; 0.79]), elevated triglyceride levels (+ 0.3 mmol/L [0.11; 0.41]), and steatosis hepatis (intrahepatocellular fat content: + 54% [29; 79%]) when it is associated with a positive energy balance (fructose dose + 25–40% of the total caloric requirement). Meta-analyses in the isocaloric setting have not shown any comparable effects. Children, with their preference for sweet foods and drinks, are prone to excessive sugar consumption. Toddlers under age two are especially vulnerable.

Conclusion

The effects that have been observed with the consumption of large amounts of fructose cannot be reliably distinguished from the effects of a generally excessive caloric intake. Further randomized and controlled intervention trials of high quality are needed in order to determine the metabolic effects of fructose consumed under isocaloric conditions. To lessen individual consumption of sugar, sugary dietary items such as sweetened soft drinks, fruit juice, and smoothies should be avoided in favor of water as a beverage and fresh fruit.

Cardiovascular diseases are still among the main causes of death in the Western world, despite a recent decline in incidence (1). They are usually due to the metabolic syndrome, whose main manifestations are predominantly truncal obesity, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, and impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus (2– 4).

Free sugars.

Free sugars are mono- and disaccharides that are either naturally present in food and beverages or are added to them during processing. They are essentially a rapidly mobilizable energy source that provides little or no physiological nutritional benefit.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Western world has risen sharply in the past few decades and has now become stable at a high level (3, 5). According to current data, 47% of all women and 62% of all men in Germany are overweight (body mass index >25 kg/m²), while 18% of all adults are obese (BMI >30 kg/m²) (6, e1, e2). Among children aged 3 to 17, 15% are overweight (above the 90th Kromeyer–Hauschild percentile), while 6% are obese (above the 97th Kromeyer-Hauschild percentile) (7, e3). Positive caloric balance and the consumption of free sugars are important contributory causes of overweight and the metabolic syndrome. The term “free sugars” refers to monosaccharides (glucose, fructose) and disaccharides (saccharose, i.e., household sugar; lactose) that are either naturally present in food and beverages or are added to them during processing. Unlike oligosaccharides and polysaccharides, free sugars are essentially a rapidly mobilizable energy source that provides little or no physiological nutritional benefit. It is recommended in the current WHO guideline that the amount of free sugars consumed should be less than 10% of the recommended daily calorie intake (RDCI) of adults and children. With an RDCI of 2000 kcal, this corresponds to 50 g of sugar (17 sugar cubes ≈ 12 teaspoons of household sugar ≈ 500 ml of orange juice) per day (table 1). This recommendation pertains both to sugars that have been added to foods and beverages during their production and to free sugars contained naturally in honey, syrup, fruit juices, and fruit juice concentrates (8, 9). The sugar intake of children is particularly important, as they have an inborn, evolutionarily advantageous preference for sweet foods and drinks, and their nutritional requirement undergoes major shifts during infancy and the pubertal growth spurt (10). Children are more sensitive to sugar and prefer a higher sugar content in water and soft drinks than adults do (11, 12, e4, e5). Pre- and postnatal exposure to certain types of taste via the amniotic fluid and breast milk affects future taste preferences (e6, e7). Breast milk, compared to formula, offers the infant a wider variety of taste sensations and seems to promote children’s acceptance of a more diverse range of foods (13). Taste preferences and dietary habits develop largely in the first two years of life and persist throughout childhood. Children who regularly drink sweet beverages at a young age continue to prefer them when they are older. Because of this so-called flavor learning, children under age 2, whose taste preferences can still be influenced, are a vulnerable group for excessive sugar intake (10). Because of this, the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recommends that children and adolescents aged 2–18 years should consume no more than 5% of their recommended daily caloric intake in the form of sugar, corresponding to 16 g of sugar (4 teaspoons) for a 4-year-old boy. Children under age 2 should consume even less sugar (table 1) (13). At present, the actual amount of free sugars consumed as a percentage of overall caloric intake is 13–14% in adults and 15–17.5% in children, which is far above the recommended upper limit (9, 14, e8). Most of the free sugar intake in childhood is accounted for by sweets (34%) and fruit juices (22%), but sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) play a role as well, as they have little satiating effect despite their high energy density (14, 15, e9). The individual sugar intake can be reduced by replacing sugary products such as SSB, fruit juices, and smoothies with water as a beverage and fresh fruit (Box).

Table 1. Quantitative recommendations for free sugar intake in adults and children*.

| Recommending body | Region | Target group | Quantitative reommendation |

| WHO, 2015 (8) | global | general population | < 10% of rdci (strong) |

| < 5% of rdci (conditional) | |||

| DAG/DDG/DGE, 2018 (9) | Germany | general population | < 10% of rdci |

| ESPGHAN, 2017 (13) | Europe | children, adolescents (2 to 18 years old) | < 5% of rdci |

| infants, toddlers (<2 years old) | less |

* The WHO recommendation for further reduction of free sugar intake to less than 5% of the recommended daily caloric intake, in order to lower the risk of dental caries, is of conditional applicability.

DAG, German Obesity Society (Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft); DDG, German Diabetes Society (Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft); DGE,German Society for Nutrition (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung); ESPGHAN, European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; RDCI, recommended daily caloric intake; WHO, World Health Organization

Practical recommendations for lowering free sugar intake.

The individual intake of free sugars can be lowered by replacing dietary items that contain sugar by alternatives that do not. The drinking of water, rather than sugary soft drinks and fruit juices, is recommended. A further possible alternative is unsweetened tea; however, as the consumption of large amounts of tea over the long term poses a health risk for children, pregnant women, and nursing mothers because of a potentially high pyrrolizidine alkaloid content (mainly in herbal teas), these persons should drink tea only in alternation with other beverages (e30). Fruit purees and smoothies are particularly popular among toddlers and contain large amounts of free sugar, yet, unlike fresh fruit, they yield hardly any dietary fiber. In the selection of dairy products and cereals, unsweetened alternatives should be chosen preferentially; these can be sweetened with fresh fruit if necessary. Replacing sugary soft drinks with soft drinks that have been sweetened with non-caloric substances (aspartame, acesulfam K) has a beneficial effect on weight development in children (e31, e32). Nonetheless, the long-term effects of these sweeteners, particularly in children, have not been adequately studied, and their consumption can therefore not be recommended. Special so-called children’s foods often contain large amounts of free sugars and cannot be recommended (13).

Obesity prevalence and sugar consumption.

Sugar consumption and the prevalence of obesity rose in parallel from 1980 to 2005; in the past decade, the prevalence of obesity in Germany has stabilized, while sugar consumption has declined

Recommended sugar intake for adults.

The amount of free sugars consumed should be less than 10% of the recommended daily calorie intake (RDCI). With an RDCI of 2000 kcal, this corresponds to 50 g of sugar.

In the past, emphasis was laid on the adverse metabolic effects of glucose, including elevated blood sugar levels and hyperinsulinism. In this review article, we will devote particular attention to the special metabolism of fructose and its association with the metabolic syndrome and with steatosis hepatis, and we will discuss the preventive measures that can be taken.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed and the Cochrane Library, with special attention to international guidelines and expert recommendations. The following search terms were used: “fructose AND weight gain AND obesity,” “fructose AND hypertension AND uric acid,” “fructose AND metabolism AND triglycerides AND insulin,” and “fructose AND non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.” Clinical trials and meta-analyses from countries with a Western lifestyle, published in either English or German in the period 1987–2020, were considered.

Chemical properties and metabolism

Fructose is a ketohexose found naturally in fruits and vegetables. It plays a major role in industrial food production, e.g., as a component of saccharose or high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). Sugared soft drinks account for much of the fructose intake. In Europe, such drinks are sweetened with household sugar (saccharose), which consists of equal portions of fructose and glucose connected by a glycoside bond. In the USA, saccharose has been replaced to an increasing extent in recent decades by HFCS, which is less expensive. HFCS is a mixture of free fructose and free glucose, with the fructose contribution varying from 42% to 55%. Fructose alone is a more powerful sweetener than saccharose (× 1.17 in comparison to saccharose) or glucose alone (× 0.67 in comparison to saccharose). Fructose also has a lower glycemic index than glucose, i.e., it elevates blood sugar to a lesser extent than glucose does (fructose: 19 vs. glucose: 100) (e10– e12) (figure 1).

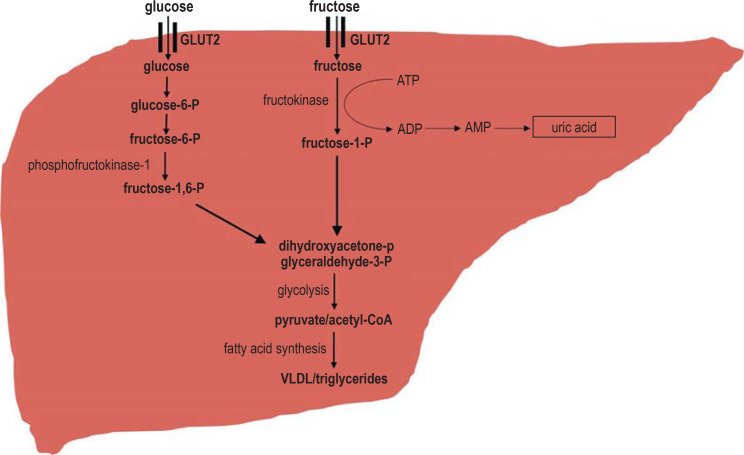

Figure 1.

The hepatic metabolism of fructose and glucose

The uptake of fructose in the intestinal epithelium and its transport into the portal venous circulation take place independently of insulin by means of the highly specific fructose transporter GLUT5. In the liver, hepatocellular uptake of fructose and glucose is facilitated by the insulin-independet transporter GLUT2. Degradation of glucose to fructose-1,6-phosphate occurs with the aid of the key enzyme of glycolisis phosphofructokinase-1, whereas degradation of fructose circumvents this regulatory mechanism. The metabolism of both monosaccharides leads to the generation of dihydroxyacetone phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, which are degraded to pyruvate in glycolysis. As there is no feedback mechanism regulating fructose metabolism, acetyl-CoA substrate accumulation ensues, exceeding the capacity of the citrate cycle. Excess citrate serves as a substrate for de novo lipogenesis. Fructose is converted to fructose-1-phosphate with the consumption of ATP. The resulting ADP is degraded to uric acid, which inhibits endothelial NO synthase, thereby contributing to arterial hypertension. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter; P, phosphate; VLDL, very low density lipoproteins. Adapted from (e25).

Fructose, obesity, and lipid metabolism

The increasing prevalence of obesity in the Western world since the 1980s and the parallel increase in the consumption of free sugars suggest that sugar, and fructose in particular, may be playing a harmful role. This suspicion remains even though, in the past decade, the prevalence of obesity in Germany has stabilized, while sugar consumption has declined, mainly among children (4, 7, 9, 14, 16, e13).

It must be asked, however, whether fructose poses a particular danger because of its special metabolism, or whether the observed adverse effects are due merely to increased caloric intake by way of fructose. There is no question that a high caloric intake, exceeding the individual’s energy requirement over a long period of time, will lead to weight gain (17), and excessive calorie intake via fructose is certainly a major part of this. In a retrospective cohort study involving 628 children, Disse et al. found that primary fructose malabsorption, a phylogenetically impaired capacity to absorb fructose, is negatively associated with obesity (odds ratio: 0.35, 95% confidence interval [0.13; 0.97]) (18). Experiments in rats have shown weight gain with high fructose intake (20% of the total caloric requirement) under isocaloric conditions, but meta-analyses to date have not revealed any such effect on human body weight (e14, e15). In human trials, the consumption of large quantities of fructose (40% of the RDCI) in addition to the subjects’ usual diet for periods of 1 to 10 (median: 3) weeks resulted in significant weight gain (+ 0.53 kg, [0.26; 0.79]) (17, 19) (table 2).

Table 2. Overview of recent meta-analyses on fructose and metabolic parameters *.

| Design | Source | Studies analyzed | RCT | N | Follow-up (weeks) | Fructose dose | Control | Remarks |

| Fructose and obesity | ||||||||

| i | Sievenpiper et al. (17) | 31 | 18/31 | 637 | 8 (1–52) | 69 g/d, 17% RDCI (22.5–300 g/d) | fructose vs. starch, glucose, saccharose, HFCS | no effect of fructose on body weight |

| i | Te Morenga et al. (19) | 12 | 12/12 | 135 | 4 (4– 24) | – | high-fructose diet vs. low-fructose, isocaloric diet | no weight gain with isocaloric exchange of free sugars |

| h | Sievenpiper et al. (17) | 10 | 6/10 | 119 | 3 (1– 10) | + 182 g/d, 37.5% RDCI (104–250 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | no weight gain with hypercaloric fructose intake |

| h | Te Morenga et al. (19) | 10 | 10/10 | 382 | 4 (4– 24) | + 19% RDCI (80–132 g/d) | increased vs. decreased intake of free sugars | 0.75 kg weight gain with increased free sugar intake |

| x | Te Morenga et al. (19) | 5 | 5/5 | 1285 | 24 (10– 32) | − 8% RDCI (44–71 g/d) | decreased free sugar intake vs. normal diet | 0.8 kg weight loss with decreased free sugar intake |

| Fructose and lipid metabolism | ||||||||

| i | Wang et al. (20) | 14 | 8/14 | 290 | 13 (1–95) | 120 g/d, 20% RDCI (22.5–168 g/d) | fructose vs. starch, glucose, saccharose, HFCS | no difference in post-prandial triglycerides |

| i | Chiavaroli et al. (21) | 51 | 24/51 | 943 | 4 (1–95) | 97 g/d, 20% RDCI (25–300 g/d) | fructose vs. starch, glucose/saccharose/HFCS | no effect on LDL, HDL, triglycerides, or apolipoprotein B |

| i/h | Kelishadi et al. (28) | 15 | – | 452 | 2 (0.3–10) | 150 g/d, 25% RDCI (40–250 g/d) | – | increased triglycerides,decreased HDL-cholesterol |

| h | Wang et al. (20) | 2 | 0/2 | 33 | 5 (2– 8) | + 175 g/d, 25% RDCI(168–182 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | increased postprandial triglycerides |

| h | Chiavaroli et al. (21) | 8 | 4/8 | 125 | 2 (1– 10) | + 193 g/d, 25% RDCI (150–213 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | increased apolipoprotein B and triglycerides |

| Fructose and arterial hypertension/uric acid level | ||||||||

| i | Wang et al. (26) | 18 | 8/18 | 390 | 16 (1–52) | 94 g/d, 5–33% RDCI (25–213 g/d) | fructose vs. starch/glucose/saccharose | hepatic insulin resistance, no systemic insulin resistance |

| y | Jayalath et al. (27) | 3 | – | 223,330 | 14–20 years | 5.7–14.3% RDCI | – | no association between fructose intake and arterial hypertension |

| i/h | Kelishadi et al. (28) | 15 | – | 452 | 2 (0.3–10) | 150 g/d, 25% RDCI (40–250 g/d) | – | increased systolicblood pressure |

| h | Wang et al. (26) | 3 | 3/3 | 35 | 1 (1) | + 215 g/d, 35% RDCI (213–219 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | increased uric acid level (+ 0.5 mg/dL) |

| Fructose and insulin metabolism | ||||||||

| i | Ter Horst et al. (33) | 32 | 17/32 | 826 | 4 (1–95) | 98 g/d, 18% RDCI (26–250 g/d) | fructose vs. starch, glucose, saccharose, HFCS | hepatic insulin resistance, no systemic insulin resistance |

| i/h | Kelishadi et al. (28) | 15 | – | 452 | 2 (0.3–10) | 150 g/d, 25% RDCI(40–250 gld) | – | increased fasting blood sugar |

| h | Ter Horst et al. (33) | 14 | 7/14 | 168 | 1 (1– 6) | + 184 g/d, 25% RDCI(36–293 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | increased plasma insulin level, hepatic insulin resistance |

| Fructose and NAFLD | ||||||||

| i | Chiu et al. (38) | 7 | 6/7 | 184 | 4 (1– 10) | 182 g/d, 22% RDCI | fructose vs. starch, glucose, saccharose | no effect |

| h | Chiu et al. (38) | 6 | 1/6 | 76 | 3 (1– 10) | + 193 g/d, 25% RDCI (150–220 g/d) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | increased hepatic fat depositionincreased ALT(+ 5 U/L) |

| h | Chung et al. (39) | 6 | 4/5 | 54 | 2 (1– 4) | + 3.5 g/kg/BW/d (35% RDCI) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | ca. 50% increase in intrahepatic lipids |

| h | Chung et al. (39) | 3 | 3/3 | 51 | 1 (1) | + 3.5 g/kg/BW/d (35% RDCI) | normal diet + fructose vs. normal diet | mild rise of ALT (+ 5 U/L) |

| h | Chung et al. (39) | 3 | 3/3 | 53 | 2 (1– 4) | ≈ + 30% RDCI | fructose vs. glucose | increase in intrahepatic lipids, no difference between fructose and glucose |

| h | Chung et al. (39) | 4 | 4/4 | 98 | 4 (1– 10) | + 40 g/d ± 3.5 g/kg/BW/d | fructose vs. glucose | rise in AST(+ 1.15 U/I) and ALT (+ 2.06 U/L) in both groups; no difference between fructose and glucose |

* Meta-analyses of trials conducted in an isocaloric setting display wide variation in fructose intake and yield no more than low-level evidence. These meta-analyses have failed to show any adverse effects. In trials conducted in a hypercaloric setting, i.e., those involving fructose intake in addition to the subjects’ otherwise usual diet, adverse metabolic effects have been demonstrated. Because of the way these trials are designed, however, there is no way to determine whether the demonstrated effects are due to fructose per se, or rather to the associated caloric surplus. There is an overall lack of methodologically sound randomized and controlled trials under isocaloric conditions. In this table, the median fructose dose is given both in absolute terms and in relation to the RDCI, and its range is indicated in square brackets. Follow-up = median length of follow-up in weeks (range); ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BW, body weight; g/d, grams per day; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HFCS, high fructose corn syrup; h, hypercaloric; i, isocaloric; LDL, low density lipoprotein; n, number of subjects; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; RCT, number of randomized, controlled trials included in each meta-analysis; RDCI, recommended daily caloric intake; studies included, number of studies included in each meta-analysis; x, hypocaloric trial design; y, prospective cohort studies.

The special situation in children.

Children are more sensitive to sugar and prefer sweeter food and beverages compared to adults.

Aside from the adverse effect of fructose on body weight, it is also thought to adversely affect metabolism via substrate accumulation in the liver, leading to lipo- and gluconeogenesis through the activation of SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c) and ChREBP (carbohydrate responsive element binding protein) (20, e16) (eBox). Randomized trials have shown that fructose administration (20% of RDCI) leads to a mild elevation of postprandial triglyceride levels (+ 0.09 mmol/L, [0.01; 0.18 mmol/L]), while meta-analyses have shown that the intake of large amounts of fructose (median daily dose, 175 g and 193 g) significantly raises triglyceride levels (+ 0.26 mmol/L, [0.11; 0.41]) (20, 21, e17– e20). Recent meta-analyses have not revealed any adverse effects on triglyceride or HDL- and LDL-cholesterol concentrations after the consumption of fructose for seven days or longer under isocaloric conditions (22). Nonetheless, in a 10-week intervention trial involving 32 subjects, Stanhope et al. found that the long-term consumption of soft drinks containing fructose (25% of RDCI), compared to soft drinks containing glucose, led to an increase in visceral fat deposits (+ 14.0 ± 5.5 % versus 3.2 ± 4.4 %), in agreement with the animal data (e20– e22).

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 4 February 2022. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

What does the expression “free sugars” refer to in this article?

all mono- and disaccharides in the diet, regardless of source

all monosaccharides in the diet, regardless of source

all mono- and disaccharides that are found naturally in dietary items or are added to processed foods

all mono- and disaccharides that are added to foods

only mono- and disaccharides found naturally in dietary items

Question 2

At present, what percentage of women and men in Germany are overweight?

7% of women, 22% of men

17% of women, 32% of men

27% of women, 42% of men

37% of women, 52% of men

47% of women, 62% of men

Question 3

What type of dietary item accounts for the largest amount of free sugar intake in children?

beverages with added sugar

sweets

fruit juices

dairy products

raw fruit

Question 4

How does fructose differ from glucose?

Fructose is a less powerful sweetener.

Fructose has a higher glycemic index.

Fructose has less of an effect on the insulin level.

Fructose is consumed exclusively via fruit and fruit juice.

Fructose is not used as an additive in industrial food production.

Question 5

By means of what transporter is fructose taken up by enterocytes?

glucose transporter 1

glucose transporter 2

glucose transporter 3

glucose transporter 4

glucose transporter 5

Question 6

What is the key enzyme of glucose metabolism?

aldolase B

triokinase

fructokinase

phosphofructokinase

hexokinase

Question 7

According to recent meta-analyses, what is the consequence of high fructose intake with a positive caloric balance?

a lower uric acid level

a higher triglyceride level

a lower fasting blood sugar level

a lower intrahepatocellular fat content

a lower ALT level

Question 8

According to the recent meta-analyses of Chung et al. (2014) und Chiu et al. (2014), what effect does fructose consumption have with respect to NASH?

elevated intrahepatocellular fat content with isocaloric fructose intake

elevated ALT level with isocaloric fructose intake

elevated intrahepatocellular fat content with hypercaloric fructose intake

reduced ALT level with hypercaloric glucose intake

improved insulin sensitivity with hypercaloric fructose intake

Question 9

What is a practical way to lessen the intake of free sugars?

drinking water instead of sugary soft drinks and fruit juices

replacing sugary soft drinks with fruit juices, as these contain less sugar

replacing sugar with non-caloric sweeteners, as the long-term consequences of their use have been thoroughly studied and are well known

preferentially consuming fruit purees and smoothies, which are low in sugar

giving children so-called children’s foods such as children’s tea or fruit purees, as these contain less sugar than the usual dietary items do

Question 10

What disease is linked to high fructose consumption?

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

type 1 diabetes mellitus

peripheral arterial occlusive disease

ischemic stroke

gestational diabetes

► Participation is possible only over the internet:

cme.aerzteblatt.de

Fructose, uric acid, and insulin metabolism

Taste preferences in childhood.

Taste preferences and dietary habits develop largely in the first two years of life and persist throughout childhood and are influenced by multiple pre- and postnatal factors.

Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) is produced in the first step of fructose metabolism in the liver and is then broken down into uric acid (Figure 1, eBox). Because uric acid inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase, an elevated uric acid level may lead to diminished release of the vasodilator NO, resulting in arterial hypertension (23). Prospective cohort studies suggest an association between elevated uric acid levels and essential hypertension, particularly in adolescents (23, 24). In a randomized trial, the daily consumption of 200 g of fructose (32% of RDCI) in addition to the subjects’ usual diet raised the uric acid level by 65 ± 6 µmol/L, while also leading to a rise in blood pressure values in 24-hour measurements (systolic, + 6.9 ± 2.3 mm Hg; diastolic, + 4.7 ± 1.6 mm Hg). These effects were significantly counteracted in an intervention group by the administration of allopurinol at a daily dose of 300 mg (uric acid level, - 113 ± 12 µmol/L; systolic blood pressure, + 2.1 ± 1.2 mm Hg; diastolic blood pressure, + 1.0 ± 0.8 mm Hg), in accordance with the findings of animal experiments involving a high fructose intake (60% of overall caloric intake) (25, e23). In a review article, elevation of the uric acid level (+ 31 µmol/l, [15.4; 46.5]) was demonstrated only after the consumption of very large amounts of fructose (> 200 g per day) (26). A meta-analysis of three prospective cohort studies involving more than 200,000 subjects did not reveal any correlation between fructose intake and arterial hypertension; in contrast, Kelishadi et al., in another meta-analysis, found an association between fructose consumption and elevated systolic blood pressure, although they did not evaluate the mean fructose dose (27, 28) (table 2). Finally, a Cochrane Library study found insufficient evidence for the efficacy of blood pressure reduction by drugs that lower the uric acid level (29).

Sugar consumption in children.

At present, children in Germany consume roughly three times as much sugar as the recommended upper limit (5% of daily caloric intake). Children consume sugar mainly in sweets and fruit juices, as well as in soft drinks.

Reducing sugar consumption.

Individual sugar consumption can be lowered by replacing sugary items such as sugared soft drinks, fruit juices, and smoothies with water as a beverage and fresh fruit

Children’s foods.

So-called children’s foods, such as tea for children or fruit purees, often contain large amounts of free sugar.

Fructose metabolism.

Fructose is a more powerful sweetener than glucose and saccharose and also has a lower glycemic index than they do.

In summary, there is no clear evidence that fructose adversely affects uric acid levels and arterial blood pressure under isocaloric conditions, but very large amounts of fructose can indeed affect both of these parameters adversely.

The hepatic metabolism of fructose.

Most of the resorbed fructose is taken up into hepatocytes via GLUT2. The further metabolism of fructose is not subject to any negative feedback mechanism.

Fructose has a low glycemic index and thus does not affect the blood glucose level or the insulin level to any substantial extent. For this reason, fructose was long held to be an ideal sweetener, especially for patients with impaired glucose tolerance (30, e24). Epidemiologic data suggest an association of fructose consumption with type 2 diabetes. For example, a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies showed that persons who drink sugary beverages several times a day are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes mellitus (relative risk: 1.26 [1.12; 1.41]) (31). Romaguera et al. found a positive association between soft drink consumption and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, even after adjusting for caloric intake and BMI (hazard ratio: 1.18 [1.06;1.32]) (32). Ter Horst et al., in a meta-analysis of trials of at least six days’ duration, found that fructose consumption under isocaloric conditions led to hepatic insulin resistance (standardized mean difference [SMD]: 0.47, [0.03; 0.91]), while the consumption of fructose in a median dose of 184 g per day under hypercaloric conditions led not only to hepatic insulin resistance (SMD: 0.77, [0.28; 1.26]), but also to mildly elevated fasting insulin levels (+ 3.38 pmol/L, [0.03; 6.73 pmol/L]) (33).

There are as yet no reliable clinical data showing a clear correlation between fructose consumption and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, because fructose consumption in the available studies was always coupled with glucose consumption, in the form of either saccharose or high-fructose corn syrup.

Fructose and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases

Fructose and obesity.

Hypercaloric fructose intake with a positive caloric balance leads to overweight.

Fructose and lipid metabolism.

Hypercaloric fructose intake leads to elevated triglyceride and uric acid levels.

Meta-analyses concerning fructose consumption.

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (which are heterogeneous and provide low-level evidence) have not revealed any metabolic effect of isocaloric fructose consumption with an appropriate, unchanged caloric balance.

Fructose, which is metabolized mainly in the liver, is thought to be a contributing factor in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD). The overall category of NAFLD can be further broken down into potentially reversible non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), defined by a fat concentration of more than 5% of the weight of the hepatic parenchyma, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where mixed-cell inflammatory infiltrates and ballooned hepatocytes are seen in addition (34). The prevalence of NAFLD in industrialized countries around the world is estimated at 20–30%; it is positively correlated with the metabolic syndrome and with hyperalimentation (abdominal girth, body mass index, triglyceride levels), and it can progress to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (35, 36). Fructose is held to be a contributing factor in the development of steatosis hepatis that can itself lead to hepatic energy overload and thus also to increased amounts of fat in the hepatocytes (figure 2) (e25). Retrospective data, some of which are controversial, show higher fructose consumption among patients with NAFLD, as well as an effect on the degree of fibrosis of the liver (e26– e29). In a case-control study, Abid et al. showed that 80% of the NAFLD patients consumed more than 500 mL of soft drinks per day, compared to only 17% of the normal control subjects. Soft-drink consumption was found to be a good predictor of NAFLD in their regression model (odds ratio: 2.0) (37). Two meta-analyses have dealt with the relation between fructose consumption and steatosis hepatis. Chiu et al. and Chung et al., analyzing reported trials in which fructose was given in isocaloric exchange with other carbohydrates, found no effect of fructose on intrahepatocellular fat content or on the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level; but, in contrast, hypercaloric fructose intake (+ 25–35% of RDCI) affected both parameters adversely compared to an isocaloric diet (intrahepatocellular fat content: + 54% [29; 79%], ALT: + 4.94 U/L [0.03; 9.85]) (38, 39) (table 2). Such effects were found with the hypercaloric administration of either fructose or glucose, implying that the excessive caloric intake accounts for the observed effects (38). The informative value of meta-analyses is limited, however, by the heterogeneity of the constituent trials, the controversial state of the evidence, and the often short follow-up intervals. It cannot be stated with certainty whether fructose itself affects human metabolism adversely, or whether such effects are due solely to the excessive caloric intake when large amounts of fructose are consumed. The latter hypothesis is supported by the fact that meta-analyses have revealed adverse metabolic effects mainly in trials with a hypercaloric design.

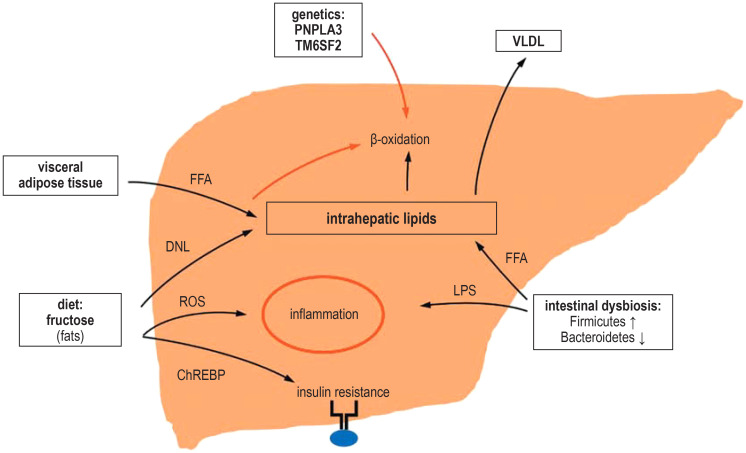

Figure 2.

The multifactorial pathogenesis of NAFLD

Hepatic lipid accumulation due to the arrival of increased amounts of lipids in the liver is sustained by intestinal dysbiosis (dysequilibrium of the intestinal microbiota), free fatty acids from the diet, and visceral fat deposits, as well as by fructose-induced de novo lipogenesis. Lipid degradation via ß-oxidation is inhibited by fructose metabolites and genetic predisposition. The transition from NAFLD to NASH is promoted by inflammation, which is triggered by endotoxins (LPS and others) released by the altered microbiome, as well as by reactive oxygen species (ROS) arising as by-products of fructose metabolism.

ChREBP, carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein; DNL, de novo lipogenesis; FFA, free fatty acids; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PNPLA3, papatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3; TM6SF2, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2; VLDL, very low density lipoproteins.

Figure modified from (e25).

Overview

The high prevalence of overweight and obesity associated with the metabolic syndrome is a problem around the world. In addition to lack of exercise, an important contributing cause is the consumption of large amounts of free sugars, which should be avoided in small children in particular, as their taste preferences can still be influenced. Fructose, either by itself or as a component of common household sugar, plays a special role, as it is mainly metabolized in the liver. Current evidence indicates that very high fructose consumption has adverse metabolic effects, but it remains unclear whether these are due to fructose itself or to the associated increase in caloric intake. Meta-analyses of trials conducted in an isocaloric setting have not confirmed any such effects, or any effect on steatosis hepatis and hepatocellular damage (table 2). There is a general lack of methodologically sound, prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trials, with adequate patient numbers and a sufficient follow-up duration, with which the possible adverse effects of fructose consumption could be studied. Individual sugar consumption can be lowered by replacing sugary items such as sugared soft drinks, fruit juices, and smoothies with water as a beverage and fresh fruit (Box). On the population level, health-promoting behavior can be reinforced with public information, food quality ratings, and taxes placed on products with added sugar.

The effects of large amounts of fructose.

High doses of fructose are associated with adverse metabolic effects. The current state of the evidence does not allow any conclusion as to whether these effects are due to a positive caloric balance or to fructose per se.

The current state of the evidence.

Because of the heterogeneity of the available studies and the low level of evidence that they provide, current RCTs and meta-analyses are of limited informative value. There is a lack of methodologically sound randomized and controlled clinical trials with sufficient follow-up under isocaloric conditions.

Further Information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 4 February 2022. Submissions by letter,e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

Once a new CME module comes online, it remains available for 12 months. Results can be accessed 4 weeks after you start work on a module. Please note the closing date for each module, which can be found at cme.aerzteblatt.de

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

A comparison of fructose and glucose metabolism.

Fructose, unlike glucose, is taken up into enterocytes by an insulin-independent mechanism via the highly specific fructose transporter GLUT5 and then passes into the portal venous circulation. Most of the fructose resorbed in the gut is taken up by hepatocytes via GLUT2 and metabolized. The blood sugar level rises only by a small amount compared to glucose, and there is neither a compensatory insulin secretion nor a negative feedback effect on gluconeogenesis. While glucose in the liver and other peripheral tissues primarily becomes a substrate for glycolysis and thus serves as a direct energy carrier, the intermediate products of fructose metabolism are mainly used for the synthesis of triglycerides. Glycolysis, under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, is the first step of the degradation of glucose to pyruvate and is subject to a feedback mechanism involving the key enzyme phosphofructokinase-1, which impedes glycolysis in the setting of a high concentration of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) or citrate. Because fructose metabolism takes place independently of phosphofructokinase-1, there is no feedback mechanism, and there may be an accumulation of acetyl-CoA, which serves as a substrate for fatty acid synthesis. In addition, the first step of fructose metabolism consumes ATP, which, in its further catabolism, is degraded to uric acid as an end product.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jagannathan R, Patel SA, Ali MK, Narayan KMV. Global updates on cardiovascular disease mortality trends and attribution of traditional risk factors. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19 44. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti G, Zimmet P, Shaw J, Grundy SM. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. www.idf.org/e-library/consensus-statements/60-idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome (last accessed on 22 July 2019) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley RA, Ruck DJ, Fouts HN. U.S. obesity as delayed effect of excess sugar. Econ Hum Biol. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100818. 100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schienkiewitz A, Mensink GB, Kuhnert R, Lange C. Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. JoHM. 2017;2:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schienkiewitz A, Brettschneider A, Damerow S, Schaffrath Rosario A. Übergewicht und Adipositas im Kindes- und Jugendalter in Deutschland - Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2 und Trends. JoHM. 2018;1:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. www.gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=2033879 (last accessed on 21 July 2019) 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst J, Arens-Azevedo U, Bitzer B, et al. Konsensuspapier: Quantitative Empfehlung zur Zuckerzufuhr in Deutschland. www.dge.de/fileadmin/public/ doc/ws/stellungnahme/Konsensuspapier_Zucker_DAG_DDG_DGE_2018.pdf (last accessed on 14 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:41–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mennella JA, Finkbeiner S, Lipchock SV, Hwang L-D, Reed DR. Preferences for salty and sweet tastes are elevated and related to each other during childhood. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092201. e92201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segovia C, Hutchinson I, Laing DG, Jinks AL. A quantitative study of fungiform papillae and taste pore density in adults and children. Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fidler Mis N, Braegger C, Bronsky J, et al. Sugar in infants, children and adolescents: a position paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:681–696. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perrar I, Schadow AM, Schmitting S, Buyken AE, Alexy U. Time and age trends in free sugar intake from food groups among children and adolescents between 1985 and 2016. Nutrients. 2019;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabenberg M, Mensink GBM für Robert Koch-Institut Berlin Limo, Saft & Co - Konsum zuckerhaltiger Getränke in Deutschland. GBE kompakt. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson RJ, Segal MS, Sautin Y, et al. Potential role of sugar (fructose) in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:899–906. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, et al. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:291–304. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disse SC, Buelow A, Boedeker R-H, et al. Reduced prevalence of obesity in children with primary fructose malabsorption: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:255–258. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7492. e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang DD, Sievenpiper JL, Souza de RJ, et al. Effect of fructose on postprandial triglycerides: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiavaroli L, Souza de RJ, Ha V, et al. Effect of fructose on established lipid targets: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001700. e001700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwingshackl L, Neuenschwander M, Hoffmann G, Buyken AE, Schlesinger S. Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk factors: a network meta-analysis on isocaloric substitution interventions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:187–196. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker de B, Borghi C, Burnier M, van de Borne P. Uric acid and hypertension: a focused review and practical recommendations. J Hypertens. 2019;37:878–883. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feig DI, Kang D-H, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Pozo SE, Schold J, Nakagawa T, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ, Lillo JL. Excessive fructose intake induces the features of metabolic syndrome in healthy adult men: role of uric acid in the hypertensive response. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:454–461. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang DD, Sievenpiper JL, Souza de RJ, et al. The effects of fructose intake on serum uric acid vary among controlled dietary trials. J Nutr. 2012;142:916–923. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.151951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayalath VH, Sievenpiper JL, Souza de RJ, et al. Total fructose intake and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:328–339. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2014.916237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelishadi R, Mansourian M, Heidari-Beni M. Association of fructose consumption and components of metabolic syndrome in human studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2014;30:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gois PHF, Souza ERdM. Pharmacotherapy for hyperuricemia in hypertensive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008652.pub3. CD008652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans RA, Frese M, Romero J, Cunningham JH, MIlls KE. Fructose replacement of glucose or sucrose in food or beverages lowers postprandial glucose and insulin without raising triglycerides: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:506–518. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.145151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2477–2483. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romaguera D, Norat T, Wark PA, et al. Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1520–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2899-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ter Horst KW, Schene MR, Holman R, Romijn JA, Serlie MJ. Effect of fructose consumption on insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diet-intervention trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1562–1576. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.137786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiß J, Rau M, Geier A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—epidemiology, clincal course, investigation and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:447–452. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roeb E, Steffen HM, Bantel H, et al. S2k Leitlinie Nicht-alkoholische Fettlebererkrankungen AWMF Register Nr. 021-025. 2015. www.awmf.org/ uploads/tx_szleitlinien/021-025l_S25_NASH_Nicht_alkoholische Fettlebererkrankung_2015-01.pdf (last accessed on 16 February 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abid A, Taha O, Nseir W, Farah R, Grosovski M, Assy N. Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver disease independent of metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol. 2009;51:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu S, Sievenpiper JL, Souza de RJ, et al. Effect of fructose on markers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:416–423. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung M, Ma J, Patel K, Berger S, Lau J, Lichtenstein AH. Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:833–849. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.086314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Thelen J, Kirsch N, Hoebel J. Health in Europe - Data from the EU Health Monitoring Programme Robert Koch-Institut Berlin. GBE kompakt. 2012;3 [Google Scholar]

- E2.Steigender Zuckerkonsum. Sachstand WD 9 - 3000 - 053/16. Zahlen, Positionen und Steuerungsmaßnahmen. www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/480534/ 0ae314792d88005c74a72378e3a42aec/wd-9-053-16-pdf-data.pdf (last accessed on 14 July 2019) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- E3.Kurth B-M, Schaffrath Rosario A. Die Verbreitung von Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des bundesweiten Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) [The prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents living in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:736–743. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A, Haliburton S, Shorkey A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001069.pub5. CD001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Gibbins S, Stevens B. Mechanisms of sucrose and non-nutritive sucking in procedural pain management in infants. Pain Res Manag Spring. 2001;6:21–28. doi: 10.1155/2001/376819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Mennella JA, Coren PJ, Jagnow MS, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2012;107 doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e88. E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Nehring I, Kostka T, Kries von R, Rehfuess EA. Impacts of in utero and early infant taste experiences on later taste acceptance: a systematic review. J Nutr. 2015;145:1271–1279. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.203976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Bagus T, Roser S, Watzl B, für Max Rubner-Institut Bundesforschungsinstitut für Ernährung und Lebensmittel Reformulierung von verarbeiteten Lebensmitteln - Bewertungen und Empfehlungen zur Reduktion des Zuckergehalts 2016. www.mri.bund.de/fileadmin/MRI/Themen/Reformulierung/Reformulierung_Thema-Zucker.pdf (last accessed on 22 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E9.Richter A, Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Roosen J, Thiele S, Mensink GB. Dietary patterns of adolescents in Germany—associations with nutrient intake and other health related lifestyle characteristics. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Hanover LM, White JS. Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;(Suppl 58):724–732. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.724S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Bantle JP, Slama G. Is fructose the optimal low glycemic index sweetener? Nutritional management of diabetes mellitus and dysmetabolic syndrome. Nestlé Nutr Workshop Ser Clin Perform Program. 2006;11:83–95. doi: 10.1159/000094427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Gaby AR. Adverse effects of dietary fructose. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:294–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:537–543. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Jürgens H, Haass W, Castaneda TR, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened beverages increases body adiposity in mice. Obes Res. 2005;13:1146–1156. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Bocarsly ME, Powell ES, Avena NM, Hoebel BG. High-fructose corn syrup causes characteristics of obesity in rats: increased body weight, body fat and triglyceride levels. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Nagai Y, Yonemitsu S, Erion DM, et al. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 beta in the pathogenesis of fructose-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Chong MF, Fielding BA, Frayn KN. Mechanisms for the acute effect of fructose on postprandial lipemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1511–1520. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, Dingfelder CS. Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. J Nutr. 2008;138:1039–1046. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Macedo RCO, Vieira AF, Moritz CEJ, Reischak-Oliveira A. Effects of fructose consumption on postprandial TAG: an update on systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:364–372. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Crescenzo R, Bianco F, Coppola P, et al. Adipose tissue remodeling in rats exhibiting fructose-induced obesity. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, et al. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: a 6-mo randomized intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:283–289. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1322–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Nakagawa T, Hu H, Zharikov S, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F625–F631. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00140.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Teff KL, Elliott SS, Tschöp M, et al. Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2963–2972. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Ter Horst KW, Serlie MJ. Fructose consumption, lipogenesis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. 2017;9:981. doi: 10.3390/nu9090981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Mosca A, Nobili V, De Vito R, et al. Uric acid concentrations and fructose consumption are independently associated with NASH in children and adolescents. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Abdelmalek MF, Suzuki A, Guy C, et al. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1961–1971. doi: 10.1002/hep.23535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Kanerva N, Sandboge S, Kaartinen NE, Männistö S, Eriksson JG. Higher fructose intake is inversely associated with risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in older Finnish adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1133–1138. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.086074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Pyrrolizidinalkaloide in Kräutertees und Tees - Stellungnahme 018/2013 des BfR vom 5. Juli 2013. www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/pyrrolizidinalkaloide-in-kraeutertees-und-tees.pdf (last accessed on 26 September 2020) [Google Scholar]

- E31.Ruyter de JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1397–1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1407–1416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]