Abstract

The metabolome represents a complex network of biological events that reflects the physiologic state of the organism in health and disease. Additionally, specific metabolites and metabolic signaling pathways have been shown to modulate animal ageing, but whether there are convergent mechanisms uniting these processes remains elusive. Here, we used high resolution mass spectrometry to obtain the metabolomic profiles of canonical longevity pathways in C. elegans to identify metabolites regulating life span. By leveraging the metabolomic profiles across pathways, we found that one carbon metabolism and the folate cycle are pervasively regulated in common. We observed similar changes in long-lived mouse models of reduced insulin/IGF signaling. Genetic manipulation of pathway enzymes and supplementation with one carbon metabolites in C. elegans reveal that regulation of the folate cycle represents a shared causal mechanism of longevity and proteoprotection. Such interventions impact the methionine cycle, and reveal methionine restriction as an underlying mechanism. This comparative approach reveals key metabolic nodes to enhance healthy ageing.

Subject terms: Metabolomics, Molecular biology

Metabolic pathways are closely intertwined with longevity. Here the authors perform metabolomic profiling of canonical longevity pathways and show that folate and methionine cycle intermediates are changed in common, and further, genetic manipulation of pathway enzymes and supplementation with metabolites indicates that they causally regulate longevity.

Introduction

Cellular metabolism encompasses a highly integrated, complex network that supports the development, growth, and reproduction of the organism. Small molecule metabolites comprise basic building blocks for macromolecules and serve as essential carriers of energy and redox potential. Metabolites can also work as signaling molecules that regulate metabolic flux, epigenetic landscapes, gene regulatory networks as well as nutrient and growth signaling pathways1. Metabolic dysregulation contributes significantly to diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and inflammation, and manipulating metabolite levels in vivo can help restore metabolic balance and health2.

More recently endogenous metabolites have also emerged as crucial modulators of animal longevity. These include various amino acids, alpha-ketoglutarate, spermidine, hexosamines, bile acids, nicotinamides, cannabinoids, ascarosides, and other natural compounds that regulate diverse aspects of signaling, metabolism, and homeostasis3. Moreover, many of the major longevity pathways are conserved regulators of metabolism, nutrient sensing, and growth4. Downregulation of insulin/IGF and mTOR signaling, reduced mitochondrial respiration, dietary restriction, and hormonal signals from the reproductive system can remodel metabolism, proteostasis, stress pathways, and immunity towards extended survival and longevity5. The question arises, do these diverse signaling pathways converge on shared metabolic outputs that are causal for an extended life? Here we show that canonical longevity pathways converge on the one-carbon folate cycle, and cause a decrease in levels of the intermediate 5 methyl tetrahydrofolate (5MTHF) and various methionine cycle intermediates. Genetic manipulation of pathways enzymes and supplementation experiments reveal that reduction of specific folate intermediates promotes longevity and proteoprotection as a common conserved mechanism that acts through methionine restriction.

Results

Metabolomic fingerprint of long-lived mutants

To understand whether longevity pathways converge on common metabolic outputs, we performed high-resolution mass spectrometry on several long-lived mutant strains in C. elegans, to retrieve metabolic fingerprints. We used four canonical longevity mutants, namely insulin/IGF signaling (IIS)-deficient daf-2(e1370), dietary restriction (DR) model eat-2(ad465), mitochondrial respiration deficient isp-1(qm150) and germline-less glp-1(e2141)ts worms. Differentially regulated metabolites were characterized by mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics, using reverse-phase liquid chromatography combined with electrospray ionization high-resolution accurate mass (ESI-HRAM) spectrometry. Using this method, we identified and quantified 145 unique metabolites representing different metabolic modules (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a–c, Supplementary Data 1). Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of the biological replicates revealed a clear grouping according to genotype (Supplementary Fig. 1b), showing the high quality of the samples. In addition, both glp-1 and WT grown at 25 °C as well as eat-2 separated from the main cluster of isp-1, daf-2, and WT grown at 20 °C.

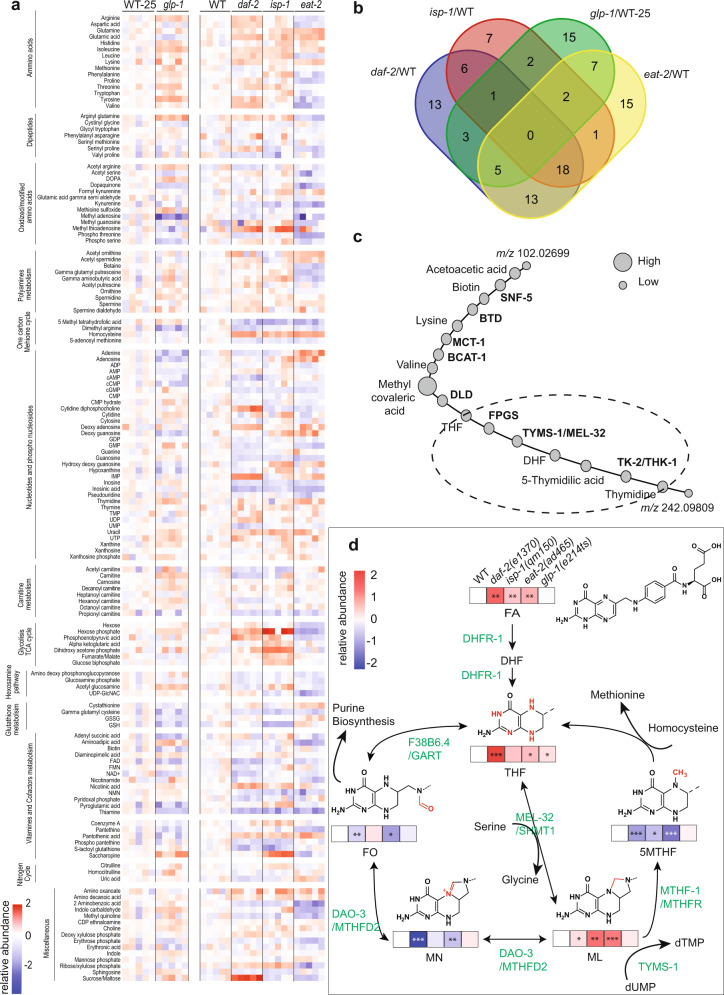

Fig. 1. Regulation of the folic acid cycle is altered in longevity mutants.

a Untargeted metabolomic analysis of daf-2(e1370), eat-2(ad465), isp-1(qm150), and glp-1(e2141)ts worms at day 1 of adulthood. glp-1(e2141)ts worms are compared with wild-type (WT) control, which undergoes the same 25 °C thermal shift as the mutant. Heat map containing all biological replicates, indicates the relative abundance of metabolite concentrations relative to the wild-type average, including both significant and non-significant changes, (listed in Supplementary Data 1). Metabolites are manually grouped into different functional categories. b Venn diagram of the significantly changed metabolites (adj p < 0.05) for each genotype showing unique and overlapping compounds. c Metabolic-protein network of unknown and known features created by the PIUMet algorithm (http://fraenkel-nsf.csbi.mit.edu/piumet2/). The degree of confidence of the PPI algorithm is represented by node diameters. Additional parameters are found in Supplementary Table 5. Dotted circle indicates the region of the network chosen for further investigation. Abbreviations in the chart: SNF-5 (Sodium: Neurotransmitter symporter Family, orthologous to SLC6A8), BTD (biotinidase), MCT-1 (Mono carboxylate Transporter family, orthologous to SLC16A14), BCAT-1 (branched amino acids transporter), DLD (dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase), FPGS (folylpolyglutamate synthase), TYMS-1 (thymidylate synthetase), MEL-32 (orthologue of SHMT1 serine hydroxymethyl transferase 1) THK-1 (thymidine kinase-1). d Quantitation of folic acid intermediates using targeted metabolomic analysis in longevity mutants (day 1 adult). FA, THF, and ML accumulate in three out of four longevity mutants. 5MTHF significantly decreases in three longevity mutants. Abbreviations in the chart: FA (folic acid), DHF (dihydrofolic acid), THF (tetrahydrofolic acid), 5MTHF (5‐methyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid), ML (5,10‐methylene‐tetrahydrofolic acid), MN (5,10‐methenyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid), FO (formyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid). a, d N = 5 independent biological replicates. a, d Normalized metabolite concentrations are converted to log2 for heat map generation. a, b Statistics were performed using one-sided Fisher test and Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (adj p < 0.05) and d using one-way-ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Supplementary Table 6, for statistics).

We first examined the metabolic signatures of each genotype individually. As expected, the relative levels of numerous metabolites were significantly changed (adj p < 0.05) in and glp-1 (35), daf-2 (59), isp-1 (37), and eat-2 (61), compared to wild-type (WT) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 1). Some of these changes have been observed previously6–11, confirming the validity of the approach, while others appeared novel (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The number of metabolites that were uniquely regulated in only one genotype relative to WT was 13 in daf-2, 7 in isp-1,15 in glp-1, and 15 in eat-2 (adj p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 1).

As multiple individual metabolites were changed in each of the longevity pathways (Fig. 1a), we first sought to evaluate KEGG pathway enrichment for each genotype. We uploaded the significantly changed (p adj < 0.05) metabolites to MetaboAnalyst (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca). This platform uses a reference metabolome to determine if the experimental metabolite set is overrepresented for certain KEGG-defined metabolic terms compared to random chance. Major enriched terms in glp-1 vs WT-25 comparison included purine metabolism, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, glutamine, and glutamate metabolism, and branched-chain amino acids. daf-2 vs WT comparisons revealed enrichment in purine, glutamine, and glutamate metabolism, branched-chain amino acids, pantothenate and CoA, and arginine biosynthesis. isp-1 vs WT comparisons showed enrichment in glutamine and glutamate metabolism, arginine metabolism, pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis, purine metabolism, alanine, aspartate metabolism, and butanoate metabolism. eat-2 vs WT comparisons showed enrichment for glutamine and glutamate metabolism, purine metabolism, arginine, nicotinamide, and branched-chain amino acid metabolism. (Supplementary Fig. 1d–g and Supplementary Table 3). Several KEGG terms were shared by all genotypes, including d-glutamine and d-glutamate metabolism, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, and purine metabolism, reflecting general regulation of amino acid and nucleotide metabolism in common. A caveat of enrichment analysis is that it is biased towards metabolites that can be readily measured on our platform, and might not highlight individual metabolites that are significantly changed but whose metabolic pathways are not necessarily enriched.

Changed metabolites common across pathways

We next leveraged changes in individual metabolites across all four mutants to determine if there were any common specific features. Although several metabolites showed trends in common across pathways, none emerged as significant (adj p < 0.05) from this analysis (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 1). Uracil, isoleucine, glutamine, lysine, appeared higher in all genotypes (Fig. 1a), but reached significance only in 2 or 3 backgrounds (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1). Erythronic acid, phosphothreonine, propionyl carnitine, kynurenine, gamma-glutamyl cysteine, methyl quinoline, glucosamine phosphate, phospho pantethine, FAD, thiamine, 2-amino benzoic acid, S-adenosyl methionine, dimethylarginine, appeared lower in all genotypes (Fig. 1a), but significant only in 1–3 backgrounds (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1).

glp-1 mutants are sterile and lack germline, which could give rise to a disparate metabolic profile. We, therefore, limited our search to the metabolites that were commonly and significantly regulated in three non-sterile genotypes, daf-2, eat-2, and isp-1 (adj p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1). From this comparison, significantly upregulated metabolites included several amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, glutamine, glutamic acid). Folate and methionine metabolism intermediates were downregulated (5 methyl tetrahydrofolate, S-adenosyl methionine, dimethylarginine), whereas homocysteine was increased. Nucleotides and related metabolites were also variously dysregulated (uracil, guanosine, inosine, cyclic GMP, NMN, FAD). Moreover, we found changes in phosphothreonine, propionyl carnitine, kynurenine, pantethine monophosphate, pantothenic acid, glucosamine phosphate, gamma-glutamyl cysteine, thiamine, and 2-amino benzoic acid (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1).

Taking advantage of our unbiased metabolomics acquisition, we additionally retrieved sixty unassigned m/z values that were differentially regulated in all genotypes (Supplementary Table 4). These uncharacterized m/z values were submitted to a pathway predictor software (PIUMet)12. The PIUMet algorithm identified 75% of the submitted features, correctly assigned the already reported metabolites, and pinpointed 10 new m/z features. To find the connection between the assigned features and a common pathway, the algorithm linked the identified compounds together based on high-confidence protein–protein and protein–metabolites interactions (PPI) (Supplementary Table 5). The network revealed high-confidence links of organic acids, branched-chain amino acid, and folic acid metabolism (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 5). Given the biological importance of the folic acid pathway in human health and the large degree of differential regulation we observed in our data (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Data 1), we decided to follow up on the possible role of these metabolites in longevity.

One carbon metabolism folate cycle is altered in longevity mutants

One-carbon metabolism mediated by folate cofactors supports multiple physiological processes including amino acid homeostasis (methionine, glycine and serine), biosynthesis of nucleotides (purines, thymidine), epigenetic maintenance, and redox defense13–15. Folate is obtained from the diet and is converted to tetrahydrofolate (THF), which serves as the backbone for one-carbon reactions. Enzymes of the folate cycle catalyze the various reactions that transition carbon through three different oxidation states typified by 5,10‐methenyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid (MN), 5,10‐methylene‐tetrahydrofolic acid (ML), and 10-formyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid (FO)16,17 (Fig. 1d). Many such oxidation and reduction steps are NADPH/NADP dependent, and the folate cycle is actually a major generator of cellular NADPH.

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR-1) carries out the first two reaction steps, reducing folic acid to dihydrofolic acid (DHF) and on to tetrahydrofolate (THF) (Fig. 1d). Using serine as a methyl donor, serine hydroxymethyl transferase 1 (MEL-32) then produces 5,10‐methylene‐tetrahydrofolic acid (ML), a key hub intermediate. Thereafter methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR-1) converts ML to 5MTHF, feeding into the methionine cycle (and reconstituting THF in the process). Methylene tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (DAO-3) converts ML to MN, and on to 10-formyl‐tetrahydrofolic acid (FO)16. Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase (GART) ortholog F38B6.4 transfers the formyl group from FO for use in purine biosynthesis (and converts FO back to THF in the process). Thymidylate synthase TYMS-1 also uses ML to convert dUMP to dTMP for DNA synthesis (and restores DHF in the process). DHFR also acts closely with TYMS-1 to recycle DHF back to THF. Notably, DHFR1 and TYMS1 are intimately linked as bifunctional enzymes in parasites, and copurify in plants, and together represent the rate-limiting enzymes for one-carbon metabolism18–20.

Because our untargeted metabolomic analysis revealed a significant decrease of 5 methyl tetrahydrofolate (5MTHF) in three out of four longevity mutants, we subsequently performed targeted metabolomics and quantified all major folic acid forms, except those conjugated to glutamate. We observed that FA, THF, and ML were more abundant in daf-2, eat-2, and isp-1 by 2 to 4-fold. 5MTHF and MN were 2-fold lower in these three genetic backgrounds, while FO was decreased in 3 of 4 genotypes (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 6). Additionally, THF was significantly elevated in glp-1 mutants. These results show that metabolites of the FA pathway undergo extensive quantitative changes in multiple long-lived strains, and that 5MTHF, in particular, is robustly and reproducibly reduced.

Folate cycle genes dhfr-1 and tyms-1 regulate life span

As we observed a common accumulation of folic acid in several long-lived worm mutants, we next asked if dietary supplementation of this compound influenced life span. Labeled FA entered the worm (Supplementary Fig. 3a), yet feeding physiological concentrations of FA (10 nM) had no effect on WT life span, pharyngeal pumping rate, or brood size (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). Bacteria are the main dietary source of folates for worms, but supplementation of submolar FA concentrations did not significantly affect levels of bacterial folate pathway intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f).

To manipulate the intracellular concentration of folic acid intermediates in vivo, we utilized RNAi against key enzymes of the pathway combined with supplementation experiments. We focused on folate cycle enzymes and first performed a mini-screen using RNAi against dhfr-1, mel-32, mthf-1, dao-3, tyms-1, and F38B6.4 from L4 stage on (Supplementary Fig. 3g). RNAi knockdown of these genes reduced mRNA expression to 20–60% of controls (Supplementary Fig. 3h). Only tyms-1i and dhfr-1i, however, increased mean life span significantly, by 25% and 28%, respectively (Supplementary Table 7). Further ageing experiments confirmed that dhfr-1 RNAi administered from L4 stage on consistently extended worm mean life span by 17–26% (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 7), with little effect on food intake as measure by pharyngeal pumping rates or reproductive capacity as measured by brood size (Supplementary Fig. 3i, j). Similarly, RNAi knockdown of tyms-1 also led to a 20% increase in worm median life span (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 7), consistent with its close association with dhfr-1.

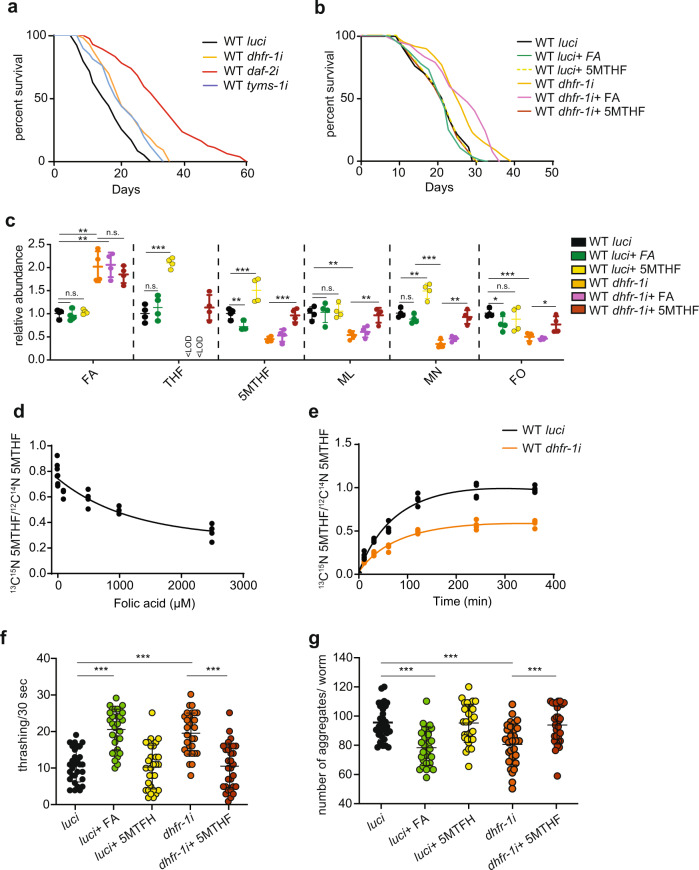

Fig. 2. dhfr-1i prolongs nematode life span in a 5MTHF dependent manner.

adhfr-1 and tyms-1 RNAi treatment increase wild-type life span (from L4 stage). b Supplementation of 10 nM 5MTHF abolishes dhfr-1i longevity (from L4 stage). c Quantitation of folic acid intermediates using targeted mass spectrometry in wild-type worms (day 1) with luci and dhfr-1i treatment in the presence or absence of folic acid and 5MTHF. dhfr-1i increases folic acid and decreases 5MTHF and downstream intermediates. d Increasing concentrations of FA inhibit 13C15N labeled 5MTHF incorporation within a 2 h time period (day 1 adult). e Incorporation of 13C15N labeled 5MTHF over time in worms with luci (black line) and dhfr-1i (orange line) (day 1 adult) each dot represents a single biological replicate. f Thrashing assay of polyQ35 worms (day 7 adult). g Protein aggregate quantitation in polyQ40 model (day 7 adult). dhfr-1i or FA supplementation are beneficial, whereas 5MTHF is detrimental for motility and aggregate accumulation. Each dot represents a single worm. a, b n = 150 worms per repeat per condition, N = 3 biological replicates. c N = 5 biological replicates. d, e N = 4 independent biological replicates. f, g n = 30 worms, N = 3 independent biological replicates, only one biological replicate is shown. a, b Statistics were performed with the two-sided Mantel–Cox log-rank test (Supplementary Table 7 for statistics). c, f, g Significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (Supplementary Table 8 for statistics).

We then measured the levels of folate cycle intermediates upon dhfr-1i knockdown by targeted metabolomics (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 6). dhfr-1i led to an accumulation of upstream FA, concomitant with a reduction in downstream intermediates THF, 5MTHF, MN, ML, and FO, confirming our previous results21. Consistent with a critical role as a rate-limiting enzyme in the one-carbon cycle, supplementation of dhfr-1i-treated worms with the downstream intermediate 5MTHF restored near-normal levels of all folate cycle intermediates, except for upstream FA, which remained high. In luci controls, dietary 5MTHF also elevated levels of THF, 5MTHF, MN beyond untreated animals, but had no effect on levels of ML or FO (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 6). On the other hand, supplementation of folic acid to dhfr-1i did not alter any folate intermediates. Given that 5MTHF uptake by the worm largely restored folate pools, we next asked whether supplementation would impact longevity. Whereas 10 nM 5MTHF supplementation had little effect on luci controls, it abolished extension of life by dhfr-1i (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 7), indicating that dhfr-1i longevity arises from lower levels of 5MTHF (or altered levels of other folate intermediates).

FA regulates 5MTHF uptake

Interestingly, we noticed that dhfr-1i led to the accumulation of FA, and that FA supplementation led to similar changes in folate intermediates as dhfr-1i knockdown in the worm, though not to the same extent. Specifically, both conditions led to a lowering of 5MTHF, MN, and FO (Fig. 2c). This suggested that the FA-induced decrease in these downstream intermediates might arise via inhibition of uptake or negative feedback. To test this idea, we measured the incorporation of 5MTHF in adult worms, by quantifying the uptake ratio of 13C 15N double-labeled versus non-labeled 5MTHF. We found that increasing concentrations of FA diminished labeled 5MTHF incorporation in vivo (Fig. 2d). Similarly, dhfr-1 RNAi reduced the rate of 5MTHF uptake and assimilation over time (Fig. 2e). These findings suggest an inhibitory role of FA in the assimilation of folate cycle intermediates, supporting previous in vitro work22,23.

High FA and low 5MTHF ameliorate models of polyQ proteotoxicity

Many long-lived strains exhibit improved protein homeostasis that is often manifested as greater resistance to toxic aggregate-prone proteins during aging. Various polyglutamine repeats expressed in C. elegans muscle, modeling Huntington’s disease, form aggregates and induce age-related progressive paralysis, with severity and age of onset related to repeat length24.To explore other possible benefits of FA supplementation or dhfr-1i treatment, we investigated the effect of folates on polyQ repeat proteotoxicity models. Whereas supplementation of FA or endogenous accumulation of FA via dhfr-1i significantly enhanced the motility of polyQ35 worms, supplementation with 5MTHF in both conditions was detrimental (Fig. 2f). We also tested the polyQ40 proteotoxicity model, and found that dhfr-1i reduced the number of visible protein aggregates, while 5MTHF supplementation brought such aggregates back to WT levels (Fig. 2g). These findings suggest that elevated FA and lower 5MTHF ameliorate proteotoxicity and improve healthspan.

dhfr-1i induces methionine restriction

5MTHF provides essential substrates for methionine synthase (MS) and is the main source of carbon units for the methionine cycle13. Homocysteine captures the methyl group from 5MTHF to form methionine and is rapidly converted to S-adenosyl methionine (SAM). SAM then donates its methyl group to various molecular acceptors, and in the process generates adenosyl-homocysteine, which is then converted to homocysteine. Methylation of homocysteine completes the methionine cycle (Fig. 3a). Aside from the methionine cycle, homocysteine can be channeled into transsulfuration, glutathione, and pyruvate pathways.

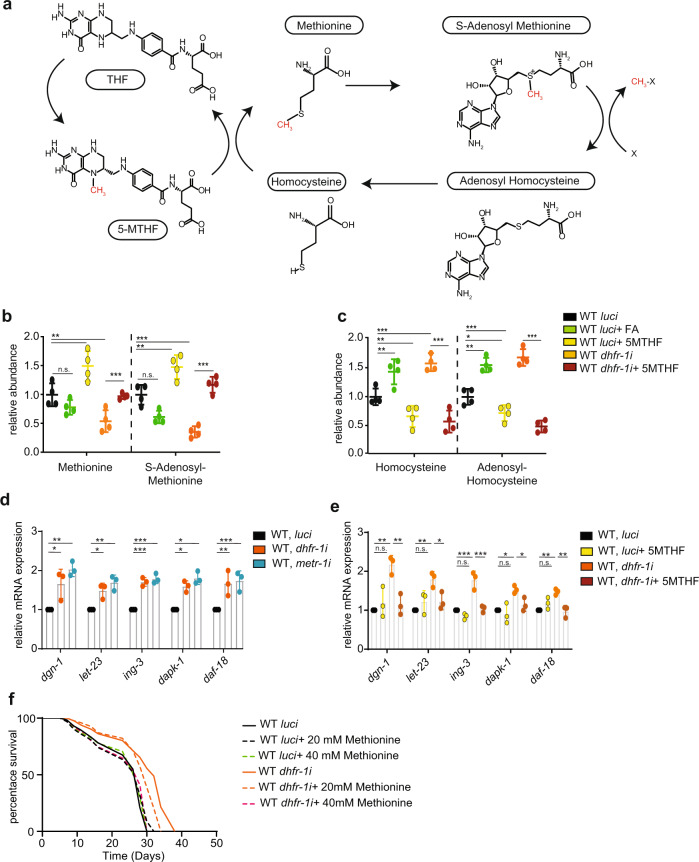

Fig. 3. dhfr-1i affects the methionine cycle and mimics methionine restriction.

a Schematic of the methionine cycle. b, c Quantitation of methionine cycle intermediates using targeted mass spectrometry in dhfr-1i and luci, with or without FA and 5MTHF supplementation (day 1 adult). dhfr-1i decreases methionine and S-adenosyl methionine levels and increases homocysteine and adenosyl-homocysteine levels. This increase is reversed by supplementation with 5MTHF. d dhfr-1i and metr-1i. show similar regulation of mRNA expression of selected genes implicated in methionine restriction (dgn-1, let-23, ign-3, dapk-1, and daf-18), day 1 adults. e Methionine restriction specific gene signature is increased by dhfr-1i and reversed by 5MTHF supplementation, day 1 adults. f Methionine supplementation (20 mM, 40 mM) suppresses dhfr-1i longevity. b, c N = 5 independent biological replicates. d, e N = 3 independent biological replicates. f n = 150 worms per repeat per condition, N = 3 biological replicates. b–e Significance was assessed using one-way anova with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. f Statistics were performed with the two-sided Mantel–Cox log-rank test. *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (Supplementary Table 8 for statistics).

We next investigated how levels of methionine cycle intermediates varied upon dhfr-1i and 5MTHF feeding using targeted metabolomics. dhfr-1i resulted in significantly lower levels of methionine and S-adenosyl methionine. dhfr-1i or FA supplementation also resulted in the accumulation of homocysteine and adenosyl-homocysteine (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Table 6). Supplementation of 10 nM 5MTHF was sufficient to significantly restore methionine levels in dhfr-1i, and reduce levels of homocysteine and S-adenosyl-homocysteine.

metr-1 encodes the C. elegans homolog of methionine synthase, and metr-1i induces methionine restriction in the worm16,25. A comparison of methionine cycle intermediates in dhfr-1i and metr-1i revealed several similarities, including reduced methionine, S-adenosyl methionine, and increased homocysteine (Supplementary Fig 4a, b and Supplementary Data 2). Thus, dhfr-1i not only reduced 5MTHF, but also perturbed the methionine pool in a manner similar to metr-1i. dhfr-1i and metr-1i also shared a more extensive metabolomic signature. Twenty-two metabolites were found in common (p < 0.05), including those known to change upon methionine restriction, such as tryptophan, methionine sulfoxide, nucleosides, uracil, and thymidine as well as metabolites associated with energy metabolism26,27 (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Data 2).

In mammalian cells, methionine restriction induces a characteristic transcriptional profile that can be used to monitor the process28. We first used metr-1i to characterize gene expression changes upon methionine restriction in the worm and validated that several nematode orthologues of genes found in the mammalian study were similarly regulated (Supplementary Table 8). We then characterized dhfr-1i knockdown, and found that it induced a similar signature, causing a significant 1.5-2-fold increase in the expression of these genes similar to metr-1i (Fig. 3d). This increase was specific, as 5MTHF supplementation of dhfr-1i-treated animals reverted expression to control levels (Fig. 3e) thereby indicating a specific gene response resembling methionine restriction27,28.

To test the idea that methionine limitation is causal for dhfr-1i longevity, we next performed methionine supplementation experiments. Notably, we observed a dose-dependent reduction in dhfr-1i longevity upon 20 and 40 mM methionine supplementation, with 40 mM fully suppressing long life (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Table 7). Similar supplementation of luci controls had little effect. These findings confirm that dhfr-1i induces longevity via methionine restriction.

To investigate more globally how dhfr-1i affects other metabolic pathways, we performed untargeted metabolomics on dhfr-1i with and without 5MTHF supplementation (Supplementary Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Data 2). In particular, we found that changes in methionine sulfoxide, uracil, thymidine as well as components of spermine and energy metabolism were partially or fully reversed upon 5MTHF supplementation (p < 0.05).

These data reveal possible novel connections between the one-carbon metabolism and other metabolic processes.

5MTHF affects the longevity of long-lived IIS and mitochondrial mutants

Our original metabolomic analysis indicated that C. elegans longevity mutants, daf-2 and isp-1 exhibit a prominent reduction in 5MTHF and other FA intermediates (Fig. 1d). We asked whether lower levels of 5MTHF play a role in life span regulation in these mutants by supplementing 5MTHF. 5MTHF treatment modestly reduced mean and max life span of daf-2 (mean: −15.8%, max: −22%) and isp-1 (mean: −13%, max:−15%), suggesting that lower levels of the 5MTHF contribute partially towards longevity in these mutants (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Table 7).

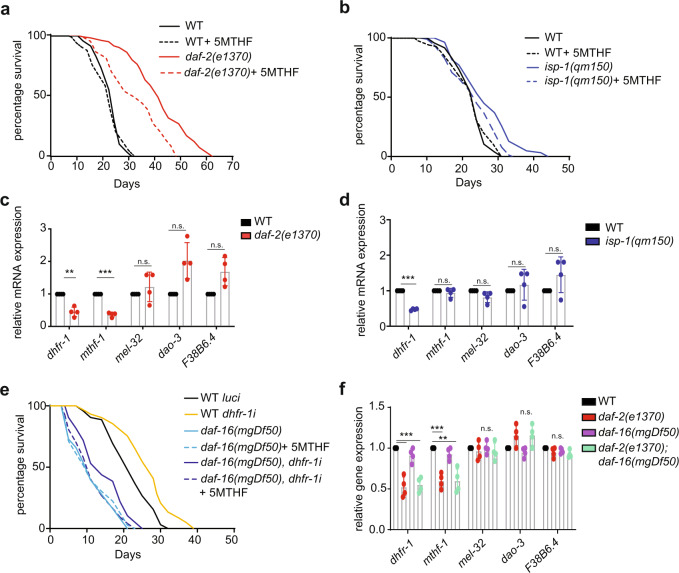

Fig. 4. dhfr-1 and 5MTHF act within insulin/IGF and mitochondrial signaling pathways.

a Life span of daf-2(e1370) supplemented with 10 nM 5MTHF (from L4 stage). b Life span of isp-1(qm150) supplemented with 10 nM 5MTHF (from L4 stage). 5MTHF does not alter WT life span but reduces daf-2 and isp-1 longevity. c, d Relative mRNA expression of folate cycle genes in daf-2(e1370) and isp-1(qm150) (day 1 adult). dhfr-1 mRNA expression is lower in both genotypes. e Life span experiment of wild-type and daf-16(mgDf50) with luci and dhfr-1i in the presence or absence of 5MTHF (from L4 stage). dhfr-1i extends daf-16 mutant life span and supplementation with 5MTHF abolishes this extension. f Relative mRNA expression of folate cycle genes in daf-16 and daf-16,daf-2 backgrounds. daf-16 mutation has little or no effect on dhfr-1 or mthf-1 mRNA expression in the daf-2 background. a, b, e n = 150 per repeat per condition, N = 3 independent biological replicates. c, d, f N = 3 biological replicates. a, b, e Statistics were analyzed by the two-sided Mantel–Cox log-rank test (Supplementary Table 7 for statistics). c, d, f Significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (Supplementary Table 6 for statistics).

To further investigate the cause of the lower 5MTHF level in these two genotypes, we quantified the mRNA expression of various folic acid cycle genes. Interestingly, dhfr-1 mRNA expression was decreased by more than 50% in both mutants. mtfh-1 expression was also ca. 50% lower in the daf-2 background (Fig. 4c, d). Other folic acid cycle genes (mthr-1, mel-32, dao-3, and F38B6.4) were unchanged. Further, we found that dhfr-1 mRNA expression was also downregulated in the dietary restriction model eat-2 relative to wild-type based on published RNA-seq data29 (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

The DAF-16/FOXO winged helix transcription factor is a major regulator of longevity whose mutation negates life extension in both daf-2 and isp-1 pathways30,31. In response to reduced insulin/IGF or mitochondrial signaling, DAF-16 localizes to the nucleus to control transcription of target genes involved in oxidative stress response, heat shock, and lipogenesis32. Because we found that dhfr-1 mRNA levels were regulated by daf-2 and isp-1 (Fig. 4c, d), we asked if dhfr-1i life span extension also showed daf-16 dependence. Aging experiments showed that the median life span of daf-16(mgDf50) was modestly increased upon dhfr-1i by 6–8% (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 7). This increase was reversed upon supplementation with 5MTHF. We next asked whether dhfr-1i affects daf-2 longevity. Aging experiments showed that dhfr-1i did not further extend the mean and maximum life span in the daf-2 background (Supplementary Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 7). These findings suggest that dhfr-1i life span extension might act within the insulin/IGF pathway, downstream or parallel to daf-16. To further address this idea, we examined dhfr-1 mRNA expression in daf-2, daf-16, and daf-16;daf-2 double mutants. We saw that daf-16 mutation either on its own or in the daf-2 background had little or no effect on dhfr-1 and mthf-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 4f). We also examined whether dhfr-1 impacts daf-16 dependent genes, gst-4, dod-3 and sod-333; but their expression was unchanged upon dhfr-1i and 5MTHF treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Altogether, these findings indicate that dhfr-1 is downregulated in response to reduced insulin/IGF signaling, but in a manner independent of daf-16. Thus, the regulation of dhfr-1 likely works through other transcription factors.

Conserved regulation of folate and methionine cycle intermediates

Because dhfr-1 affected the methionine cycle (Fig. 3), and dhfr-1 and daf-2 had overlapping longevity phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 5c) we wondered whether daf-2 mutation also perturbs methionine metabolism. To address this, we performed targeted metabolomics. We saw that, like dhfr-1i, daf-2 mutation resulted in significantly higher levels of homocysteine and adenosyl-homocysteine, lower levels of S-adenosyl methionine, as well as a trend towards lower levels of methionine, though the latter did not reach significance (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, a subset of genes induced by methionine restriction was also induced in daf-2 mutants (Fig. 5b). None of these gene expression changes, however, showed daf-16 dependence.

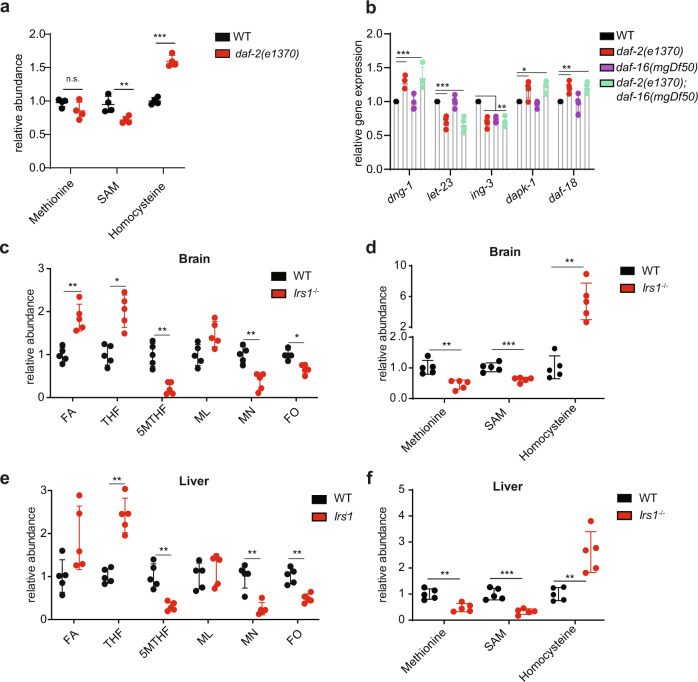

Fig. 5. Reduced insulin/IGF signaling alters folic acid and methionine cycle intermediates.

a Relative abundance of methionine cycle intermediates in daf-2 mutants and WT animals using targeted metabolomics. b Relative mRNA expression level of methionine restriction gene signature in daf-2 and daf-2;daf-16 backgrounds. dgn-1, ing-3, dapk-1, and daf-18 are upregulated and let-23 and ing-3 downregulated in the daf-2 background, independent of daf-16. c, e Targeted metabolomics of folic acid intermediates in brain and liver in wild-type and Irs1−/− full body knockout mice. Folic acid and THF increase in Irs1−/−, whereas 5MTHF decreases in the mutant. d, f Quantitation of methionine cycle intermediates in brain and liver in wild-type and Irs1−/− knockout mice. Methionine and SAM decrease and homocysteine increases in the mutant. a N = 4 independent biological replicates. b N = 3 independent biological replicates, c–f N = 5 mice, each dot represents a single animal. a–f Significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (Supplementary Table 6 for statistics).

The insulin receptor substrate protein 1 (Irs1) is a key mediator of insulin/IGF signaling (IIS) in mammals. Homozygous disruption of Irs1 in mice results in life span extension, resistance to several age-related pathologies including bone and motor dysfunction, skin, and protection against glucose intolerance34,35. Because reduced insulin/IGF signaling in worms altered folate and methionine homeostasis (Figs. 1d and 5a), we wondered if similar changes occur in the Irs1−/− mouse model. Targeted metabolomic analysis of folic acid intermediates using brain and liver tissues from female Irs1−/− knockout mice revealed a profile similar to worm daf-2 mutants (Fig. 5c, e and Supplementary Table 6). THF was significantly increased up to 2-fold in both brain and liver in Irs1−/−, while FA, and ML also tended to increase though these did not always reach significance. In addition, 5MTHF, MN, and FO were significantly decreased in both tissues. We also quantified methionine cycle intermediates and observed significantly lower levels of methionine and S-adenosyl methionine, and a large increase in homocysteine in these tissues (Fig. 5d, f and Supplementary Table 6). Altogether these data suggest that the insulin/IGF signaling pathway similarly regulates the folate and methionine cycle from worms to mammals.

Discussion

Folates are essential vitamins derived from dietary sources and the microbiome. The folate cycle provides one-carbon units for an extensive metabolic network that fuels the methionine cycle, transsulfuration pathway, de novo purine synthesis, thymidine production, serine, glycine, glutathione, and NADPH pools, and thereby regulates cellular redox state, growth, and proliferation16,36. The major canonical longevity pathways also profoundly regulate metabolism, growth, and organismal physiology in numerous ways37. By generating the metabolic profiles of several different long-lived mutants in C. elegans, we discovered that folate cycle intermediates represent a convergent focal point for longevity regulation across conserved signaling pathways.

Generally, we found that several folate intermediates were consistently altered. 5 methyl tetrahydrofolate levels were specifically decreased in long-lived models of downregulated insulin/IGF signaling (daf-2), mitochondrial respiration (isp-1), and dietary restriction (eat-2), while THF was upregulated in reproductive signaling (glp-1) mutants. In accord with a physiological role in longevity, knockdown of folate cycle enzyme dhfr-1 in the wild-type background was sufficient to similarly decrease 5MTHF, extend life span and reduce polyQ proteotoxicity. Supplementation with this metabolite restored the folate pool and reversed these phenotypes. Consistently, daf-2/InsR and isp-1/Rieske longevity were reduced by 5MTHF supplementation, and these mutant strains downregulated levels of dhfr-1 mRNA, supporting regulation of folate metabolism by these signaling pathways. Thus, reduced 5MTHF and other intermediates of folate are causal and/or associated with longevity as part of a shared mechanism in several pathways.

Previous studies in C. elegans have described various effects of FA on longevity. The anti-diabetic drug metformin extends C. elegans life span by disrupting microbial folate production and inducing methionine restriction38, while inhibition of endogenous C. elegans genes for folate uptake or folate polyglutamase activity had little effect on longevity39. By contrast, Rathor and colleagues reported that µM levels of FA extend life span40. We saw no effect of 10 nM FA supplementation on worm life span, but observed an improvement in polyglutamine proteotoxicity models, suggesting folates as potential therapeutics for proteoprotection41. These seemingly disparate observations probably reflect differences in compound dose and availability on uptake or feedback, as well as the complex interplay between diet, microbiome, and host16,25. In our case, we targeted rate-limiting interlinked enzymes of the C. elegans folate pathway, dhfr-1 and tyms-1, and saw coherent changes in folate intermediates and extension of worm life span. Supplementation with nanomolar amounts of 5MTHF were sufficient to restore folate pools of dhfr-1i, with little effect on bacterial folate pools. Knockdown of other folate cycle enzymes might not have elicited these phenotypes in our hands because of RNAi efficiency or pleiotropic effects on other processes. Interestingly, a link between longevity and folate metabolism has been recently reported in budding yeast: Rpl22 ribosomal protein mutants increase yeast replicative life span, show lower levels of metabolites associated with folate, serine, and methionine metabolism, and deletion of 1C enzymes enhanced wild-type longevity42. Interestingly, folate supplementation has also been shown to modulate the DNA methylation aging clock14.

What is the mechanism by which dhfr-1i and 5MTHF reduction trigger longevity? Several lines of evidence argue that it acts through methionine restriction (MR) and modulation of methionine cycle intermediates. First, we observed that dhrf-1 knockdown perturbs the methionine cycle, leading to reduced levels of methionine and S-adenosyl methionine and elevated levels of homocysteine. Second, we observed changes in gene expression associated with this process. Third, a comparison of metabolomic profiles from dhfr-1i and metr-1i methionine synthase revealed significant overlap. Fourth, methionine supplementation of dhfr-1i reversed longevity in a dose-dependent manner. Altogether these findings indicate that methionine restriction is causally linked to dhfr-1i life extension. Strikingly we saw similar changes in folate and methionine pools in tissues of Irs1−/− knockout mice and daf-2/InsR mutant worms, revealing that the control of the folate cycle by insulin/IGF signaling is evolutionarily conserved. Whether these changes are causally connected to life span regulation in mammals remains to be seen.

Though the metabolic link between 5MTHF and methionine seems clear, it should be pointed out that 10 nM 5MTHF and 40 mM methionine were required for dhfr-1i rescue, showing large differences in concentration. These concentration levels are consistent with the literature43,44, and probably reflect differences in the uptake or utilization of these compounds, but also raise the possibility that other 5MTHF/methionine derived metabolites or substrates could be involved. It also seems likely that additional amino acids other than methionine regulate the longevity of dhfr-1i, namely glycine and serine, which act in the folate cycle16. In this analysis, however, we were not able to measure levels of these amino acids, and thus cannot exclude their contribution in our proposed model.

Methionine restriction has a profound effect on physiology and regulates longevity through multiple mechanisms. First described to prolong life span in rodents, it shows overlapping but also distinct features from other longevity models45,46. Notably, MR reduces adiposity, IGF-1, insulin, thyroid hormone levels, increases stress resistance, energy expenditure, insulin sensitivity as well as adiponectin and FGF21 levels47. In concert with these changes, MR reportedly alters mitochondrial function, increasing aerobic capacity, and fatty acid oxidation utilization, as well as affecting redox state, reducing mitochondrial ROS production and altering glutathione and peroxidase levels48. Further, it can prolong life span in progeria models, and delay age-related decline in immune and cardiovascular function, as well as reduce cellular senescence in the kidney45. More recent work has suggested possible benefits of MR on human health including obesity, cancer, and various serum biomarkers49–51.

MR also promotes longevity in invertebrate models. In Drosophila, MR stimulates longevity under low but not high amino acid status, possibly via mTOR signaling52. Flies with reduced IIS show evidence of methionine restriction and dependence on enzymes involved in the methionine cycle for longevity53. In C. elegans, the biguanide anti-diabetic drug, metformin, reduces microbial folates in their bacterial food, resulting in methionine restriction and life span extension dependent on aak-2/AMPK and skn-1/NFE-225,54. While metr-1 mutation itself had little effect on life span, it enhanced the life-extending properties of metformin. In yeast, MR has been shown to extend chronological life span, regulate the mitochondrial retrograde response, amino acid general control pathways, and mTOR signaling as well as enhance autophagy and mitophagy55–57.

SAM metabolism ramifies into multiple intermediates and pathways associated with longevity. Strikingly, we observed reduced levels of SAM in all four longevity pathways including glp-1, as well as Irs1−/− knockout mice, suggesting a convergent mechanism (though levels of SAM are likely controlled through different routes in glp-1 given the differences in 5MTHF regulation). As a potent methyl donor, SAM catalyzes the methylation of rRNA, DNA, epigenetic factors, and aids spermidine synthesis, and thus could impact longevity at multiple levels55,58. Indeed, mutants in sams-1 and sams-5 have been shown to extend worm life span, while tissue-specific downregulation of similar enzymes in Drosophila enhances health and life52,59,60. Another methionine cycle intermediate, homocysteine, can be diverted to transsulfuration reactions, producing cysteine, H2S, and glutathione, and itself can modulate insulin/IGF signaling61,62. In multiple species, sulfur amino acid limitation activates transsulfuration pathways, leading to changes in the production of H2S, a signaling gas that stimulates survival mechanisms63. Clearly then folate and methionine cycle metabolism have broad effects on the physiology of ageing36,47,64–68, and manipulation of pathway enzymes and metabolites may provide new entry points to enhance health and longevity.

Metabolomics has emerged as a powerful approach to identify not only markers of health, disease, and ageing68, but also causal mechanisms69. Our profiles of the different longevity pathways can now be cross-referenced with other studies to generate testable hypotheses, and serve as a useful resource for the field. Interestingly, our analysis revealed congruent changes in other crucial metabolic pathways that could additionally contribute to life extension10. Among the changes, we saw modulation of kynurenine and nicotinamide metabolism, which are biochemically interlinked, and have been previously shown to regulate longevity70,71. We detected consistent changes in various nucleoside-related metabolites involved in the nucleic acid synthesis and signaling, some of which have been also associated with longevity (thymine, adenosine72,73). As well, we observed changes in propionyl carnitine, which impacts acyl-CoA and succinate metabolism, and gamma-glutamyl cysteine involved in glutathione metabolism74. We also saw changes in 2-amino benzoic acid in three longevity mutants. Derived from tryptophan by the action of the kynurenine pathway, this metabolite has been suggested as an endogenous marker of organismal mortality in the nematode75. We also observed many interesting changes in the metabolome upon dhfr-1i. Some changes were expected (e.g., folate intermediates, methionine cycle, pyrimidine, polyamine metabolism, carnitines)76. Other changes were unexpected (e.g., AMP, cAMP, NMN, alpha-ketoglutarate, dihydroxyacetone phosphate), suggestive of alterations in TCA, glycolytic, fat, and energy metabolism. Conceivably, some of these metabolic modules could further regulate longevity of reduced insulin/IGF signaling and mitochondrial function, since daf-2 or isp-1 mutants had stronger effects on life span than dhfr-1i, and 5MTHF supplementation only partially reduced longevity of these two strains. It will be interesting to validate these various changes by targeted metabolomics, and determine the potential roles of these and related metabolites in impacting health and life span.

One limitation of this work is that it only provides a broad snapshot of the steady-state levels of the various metabolites and does not measure the metabolic flux. Whether levels change because of altered synthesis or removal remains to be seen. Additionally, this study focused mainly on polar metabolites, and does not represent an extensive analysis of lipids. Nevertheless, the approach does reveal the power of leveraging multiple longevity pathways to uncover molecules that can impact the aging process and suggest several new hypotheses to be tested.

Our discovery that the regulation of the folate and methionine cycles are convergent mechanisms underlying multiple longevity pathways, and whose regulation by insulin/IGF signaling is conserved in evolution, could provide new ways to improve health during aging.

Methods

Worm strains and culture

All strains were grown and maintained on NGM agar seeded with E. coli (OP50) at 20 °C except for the glp-1(e2141)ts strain, which underwent a thermal shift to 25 °C leading to germline loss. Because of differing growth rates, worms were harvested for metabolomic analyses after 60 h for WT and eat-2, 72 h for daf-2, and 145 h for isp-1 worms to ensure similar biological age. Standard procedures for culturing and maintaining strains were used77. NGM was prepared using 3 g/L NaCl (Sigma S3014), 2.5 g/L Bacto peptode (BD 211820), 18 g/L Bacto Agar (BD 214010), 25 mM KPO4, 0.005 mg/mL Cholesterol (Sigma C8667), 1 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM CaCl2.

E. coli OP50 Bacteria were grown overnight (18 h) in LB media composed of 10 g/L Bacto tryptone (Sigma 95039), 5 g/L Bacto yeast extract (BD 212720), and 5 g/L NaCl.

The complete strain list is provided in Supplementary Table 9.

RNAi

Worm RNAi was conducted as described previously78,79. Briefly, WT wild‐type worms were fed with HT115 (DE3) bacteria transformed with L4440 vector that expresses a double‐stranded RNA against the targeted gene. HT115 strains were diluted prior to seeding till OD 0.2. Synchronized worms were obtained by performing an egg lay on corresponding RNAi plates containing isopropyl‐β‐d‐thiogalactoside and ampicillin. Luciferase (L4440::Luc, i.e., luci) RNAi vector was used as a non‐targeting control. C36B1.7 (dhfr‐1), C06A8.1(mthf-1), C05D11.11(mel-32), Y110A7A.4 (tyms-1), F38B6.4, K07E3.3 (dao-3), Y55D5A.5 (daf-2), R03D7.1(metr-1), RNAi clones were obtained from the Vidal or Ahringer RNAi libraries. The gene targeted by RNAi is indicated with an “i” after the gene name. All RNAi experiments were blinded.

Folic acid intermediates and methionine supplementation

Folic acid and 5MTHF acid were added in an aqueous solution into the NGM agar at the indicated final concentrations of 10 nM. For bacteria, folic acid and 5MTHF were added to the medium and incubated 1 or 24 h prior to extraction. Methionine was added in an aqueous solution to NGM agar at the indicated final concentration of 20 or 40 mM.

Pharyngeal pumping rate assay

Pharyngeal pumping was assessed by observing the number of pharyngeal contractions during a 30 s interval using twenty synchronized day 1 adult worms in three biological replicates. Experiments were blinded.

Brood size

L4 larvae (n = 10 animals per strain) were maintained individually under standard conditions. Synchronized young adult worms were singled to 3 cm plates containing OP50. Worms were transferred to fresh plates every 24 h and progeny number counted during a period of 7 days. A minimum of 10 worms were used for each genotype. Experiments were blinded.

Life span analysis

Life span analyses were performed at 20 °C as previously reported78,79. Data were plotted to calculate mean, median, and maximum lifespans using Microsoft Excel 16.12 and GraphPad Prism 7 Software. For all RNAi life span assays, 150 worms were fed with RNAi from L4 stage on. To determine significance between the life span curves log-rank Mantel–Cox analysis was used. Experiments were blinded.

RNA extraction and qPCR

Synchronized day 1 worms (three to four 10 cm plates, ≈8000 worms) were collected in Trizol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini spin column (QIAGEN). The concentration and purity of the RNA was measured by NanoDrop. cDNA was generated using iScript (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCR was performed with Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Four technical replicates were averaged for each sample per primer reaction. cdc-42, act-1, and amu-1 were used as internal controls. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 10.

Fluorescent microscopy

For fluorescent images of transgenic C. elegans, live animals were immobilized with 5 mM sodium azide and mounted on 2% agarose pads. Images were obtained with an Axio Imager Z1 Zeiss microscope. Puncta of the Q40 strain on day 7 were counted from at least 30 worms in three biological replicates. Experiments were blinded.

Thrashing assay

Motility was determined by measuring thrashing in liquid. Individual transgenic animals (Q35) on day 7 of adulthood were picked to a 10 µL drop of M9 on a microscope slide and were given a 30 s adjustment period before counting the thrashing rate. Thrashes (defined as the head crossing the vertical midline of the body) were counted for 30 s. A minimal n-number of n = 30 in three biological replicates was assayed for each genotype. Experiments were blinded.

Metabolite extraction from worms

Worm synchronization was achieved using thirty worms to perform an egg lay for two hours on a single plate. Five 10 cm plates (≈10,000 worms) per genotype were combined to obtain one biological replicate. This procedure was repeated five times. Worms in single tubes were washed three times with buffer solution M9 and 0.1% of butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) was added to prevent auto-oxidation as previously reported on our work21,80. Samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before use. Worm pellets were homogenized using a Qiagen tissue lyser for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit. A volume of worm lysate, which corresponds to 150 µg of proteins for each sample was subjected to Bligh and Dyer extraction (chloroform: methanol, 2:1) for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 min at 4 °C and supernatant was transferred into a new tube for drying. Before LC injections samples were reconstituted in 10% aqueous acetonitrile. Samples were analyzed using an untargeted method for total metabolomics and for targeted methods to evaluate the abundance of folic acid analogs and methionine cycle intermediates.

Folic acid intermediates extraction from mouse tissues

C3B6F1 IRS1 KO and WT control were kindly provided by the lab of Linda Partridge. C57BL/6 Irs1−/− KO mice were originally obtained from the lab of Prof. Dominic Withers’ lab (Imperial College, London). These mice were then backcrossed into the C3H/HeOuJ background by Marker-Assisted Accelerated Backcrossing (MAX-BAX®) conducted by Charles River. In order to generate homozygous C3B6F1 hybrid Irs1−/− KO mice, C3H/HeOuJ Irs1−/+ females were mated with males of the C57BL/6 Irs1−/+ KO strain. To generate C3B6F1 wild type control mice, C3H/HeOuJ females were mated with C57BL/6NCrl males (strain codes 626 and 027, respectively, Charles River Laboratories). All mice were bred on-site at the mouse facility of the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing, Cologne. The Irs1−/− KO mice were homozygous and only females were used for the experiments. Mouse experiments were performed according to the guidelines and approval of LANUV [Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen (State Agency for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection North Rhine-Westphalia), VSG 84-02.04.2014.A215]. Animals were maintained in groups of 5 females in individually ventilated cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions with constant temperature (21 °C), 50–60% humidity, and a 12-h light–dark cycle. The animals were sacrificed at the age of 24 months and tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C. Tissues underwent similar extraction as described for the worms. Tissues were homogenized using a Qiagen tissue lyser for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit and the lysate volume corresponding to 150 µg of protein was subjected to Bligh and Dyer extraction (chloroform: methanol, 2:1) for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 min at 4 °C and supernatant was transferred into a new tube for drying. Before LC injections samples were reconstituted in 10% aqueous acetonitrile. Samples were analyzed using a targeted method to assess the abundance of folic acid and methionine cycle intermediates.

Untargeted metabolomics

Analytes were separated using an UHPLC system (Vanquish, ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled to an HRAM mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive Plus, ThermoFisher Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany) using a modified RP-MS method from Wang et al.81. Briefly, two microliters of the sample extract were injected into a X Select HSS T3 XP column, 100 Å, 2.5 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm (Waters), using a binary system A water with 0.1% formic acid, B: acetonitrile with 0.1 formic acid with a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min, with the column temperature kept at 30 °C. Gradient elution was conducted as follows: isocratic step at 0.1% eluent B for 0.3 min, gradient increase up to 2% eluent B in 2 min, then increase up to 30% eluent B in 6 min and to 95% eluent B in 7 min, isocratic step at 95% eluent B for 2 min. Gradient decreases to 0.1% eluent B in 3 min and held at 0.1% eluent B for 5 min. Mass spectra were recorded from 100–800 m/z at a mass resolution of 70,000 at m/z 400 in both positive and negative ion modes using data-dependent acquisition (Top 3, dynamic exclusion list 10 s). Tandem mass spectra were acquired by performing CID (isolation 1.5 a.u., stepped collision energy 20 and 80 NCE). The m/z of leucine enkephaline was used as lock mass. The sample injection order was randomized to minimize the effect of instrumental signal drift. MS data analysis was performed using Xcalibur software 4.1.

Compound identification and quantitation

Metabolite search was performed using Compound discoverer 2.0 and m/z Cloud as online databases, considering precursor ions with a deviation > 5 ppm, 0.3 min maximum retention time shift, minimum peak intensity 100,000, intensity tolerance 10, FT fragment mass tolerance 0.0025 Da, group covariance [%] less than 30, p-value less than 0.05 and area Max greater or equal to 10000. Metabolites are correctly identified when at least two specific fragments are found in the MS2 spectra. Because of the high mass accuracy < 3 ppm, predicted elemental compositions of the unknown features were submitted to other online databases such as Chemspider (http://www.chemspider.com/), HMDB (http://www.hmdb.org/), KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), and METLIN (http://metlin.scripps.edu/).

Quantitation was performed using Trace finder 4.0, using genesis detection algorithm, nearest RT, S/N threshold 8, min peak height (S/N) equal to 3, peak S/N cutoff 2.00, valley rise 2%, valley S/N 1.10.

Relative quantitation was obtained by dividing the area of individual metabolite peaks to spiked internal standards prior to extraction (Leucine enkephaline 100 nM (Sigma L9133), myristic acid 50 nM (Sigma M3128), cysteamine-S-phosphate 100 nM (Sigma C8397)).

Integration of metabolomics features using the network-based algorithm PIUMet

the identified m/z values that were significantly changed in all genotype comparisons, were uploaded to PIUMet (http://fraenkel-nsf.csbi.mit.edu/piumet2/). We additional included 60 features, which were unidentified but significant in all genotypes (Supplementary Table 4). We used the following parameters: number of trees 10, edge reliability 2, negative prize degree 0.0005, and number of repeats 50.

The Prize-Collecting Steiner Forest algorithm identifies metabolites and represents them as nodes, the higher the assignment score the bigger the node. The algorithm links these features based on high-confidence protein–protein and protein–metabolites interactions using two databases, HMDBv4.0 and Recon3D. Further details such as node frequency and node edge are reported in Supplementary Table 5. The output was processed using the R (Rstudio v.3.3.2) package “gplot” (v3.0.1) in order to visualize the cluster of metabolites and to highlight the connection between the predicted proteins and metabolites.

Targeted analysis of folic acid intermediates

Identification and relative quantitation of folic acid intermediates were performed on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (QqQMS) (TSQ Altis, ThermoFisher Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany), as previously published by our group, and the validation of the folate identity confirmed by standards21. Data were analyzed using Xcalibur version 4.0. Quantitation was performed using Trace finder 4.1, using the genesis detection algorithm, nearest RT, S/N threshold 8, min peak height (S/N) equal to 3, peak S/N cutoff 2.00, valley rise 2%, valley S/N 1.10. The relative response for each folate species was calculated by dividing the peak area of the analyte to the internal standard peak area (pteridinic acid 100 nM, Sigma P1781) and further normalized to protein concentration.

Targeted analysis of methionine cycle intermediates

Methionine cycle intermediates were identified and quantified using a high-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive Plus, ThermoFisher Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany) coupled with an UHPLC system (Vanquish, ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Analytes were separated using a X Select HSS T3 XP column, 100 Å, 2.5 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm (Waters), using a binary system A water with 0.1% formic acid, B: acetonitrile with 0.1 formic acid with a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min and the column temperature was kept at 30 °C. Gradient elution was conducted for untargeted metabolomics analysis. Methionine cycle intermediates were identified using a Targeted-SIM (t-SIM) with a resolution of 70,000, 5e4 AGC target, 200 ms injection time, and 1.0 m/z isolation window. The following ions were quantified: Methionine –> 149.0.5084, S-adenosyl methionine –> 398.13724, homocysteine –> 135.03540, S-adenosyl-homocysteine –> 385.12800. Quantitation was performed using Trace finder 4.1, using genesis detection algorithm, nearest RT, S/N threshold 8, min peak height (S/N) equal to 3, peak S/N cutoff 2.00, valley rise 2%, valley S/N 1.10. The relative response for each methionine intermediate was calculated by dividing the peak area of the analyte to the internal standard peak area and further normalized to protein concentration. l-methionine (2,3,3,4,4-D5; methyl-D3, 98%) (Cambridge isotopes DLM-6797-PK) and S-(5′-Adenosyl)-l-methionine-(S-methyl-13C) (Sigma 798231) were used at a final concentration of 100 nM as internal standards for the analysis.

Inhibition of 5MTHF uptake by folic acid

Synchronized worms were grown on 10 cm NGM plates (three to four plate, ≈8000 worms) containing different concentrations of folic acid (0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, 2500 µM) until they reach the young adult stage. A single pulse of isotopic labeled 5MTHF-glutamic acid 13C15N at a concentration of 5 µM was added on top of the plate. Worms were harvested after 2 h after the addition of the labeled compound. Worms from three plates (≈6000 worms) were collected and washed three times using buffer solution M9. Metabolite extraction was conducted as described above. The quantification of labeled vs unlabeled folates was performed using the previous methodology and adding the MRM transitions for 13C15N label 5MTHF. Each experiment was repeated four times.

Labeled folate incorporation

To elucidate the in vivo kinetics of folic acid and 5MTHF, we used dynamic metabolite flux analysis. Synchronized worms were grown on NGM plates until they reached the young adult stage. A single pulse of isotopic labeled 5MTHF-glutamic acid 13C15N at a concentration of 5 µM or folic acid-glutamic acid-13C5,15N in a concentration of 10 nM was added on top of the plate. RNAi treatment for dhfr-1 knockdown was performed prior to the pulse. For the folic acid-glutamic acid-13C5,15N incorporation experiment (Supplementary Fig. 3), worms were harvested 1 or 2 h after the addition of the labeled compound. For the kinetics experiment (Fig. 2e), worms were collected for metabolite extraction at seven time points (0, 10, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360 min). Worms from three plates were collected and washed three times using M9 buffer solution. Metabolite extraction was conducted as described above. Quantification of labeled vs unlabeled folates was performed using the previous methodology, adding the MRM transitions for 13C15N label 5MTHF and folic acid-(glutamic acid-13C5,15N). Each experiment was repeated four times.

Statistical data

GraphPad Prism Version 8.1 software was used for graphics and statistical testing. Metabolomics data sets were analyzed using the Fisher test and Hochberg–Benjamin false discovery rate test. Individual metabolites and targeted metabolomics were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s correction test. Life span experiments were analyzed using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Orsolya Symmons for the critical reading of the manuscript and the MPG for research support. We additionally thank the bioinformatics core facility for assistance (MPI-AGE).

Source data

Author contributions

A. Antebi and A. Annibal designed experiments and wrote the paper. A. Annibal carried out all experiments. R.G.T. performed isp-1 supplemented with 5MTHF life span and isp-1 qPCR. M.F.S. performed flux analysis experiments. H.T. performed Q35 and Q40 experiments and daf-2(e1370) dhfr-1i life span. M.M.K.A. prepared mouse samples and extracted metabolites from tissues. M.F.S., H.T., and C.L. gave technical assistance. S.G. and L.P. generated the transgenic mouse line and provided the tissue sample for the targeted metabolomic analysis.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The following databases were used: HMDB (v4.0) (https://hmdb.ca/), KEGG pathway 2020 (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html), Chemspider (http://www.chemspider.com/), METLIN 2008 (http://metlin.scripps.edu/). The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper (and supplementary information files) or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

Mouse tissues were kindly provided by Linda Partridge. This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations and guidelines of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). The protocol was approved by the “Landesamt fuer Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen”.

Footnotes

Peer review informationNature Communications thanks and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/12/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41467-021-24840-z

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-23856-9.

References

- 1.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laíns I, et al. Metabolomics in the study of retinal health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019;69:57–79. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemieux GA, Ashrafi K. Investigating connections between metabolism, longevity, and behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;27:586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efeyan A, Comb WC, Sabatini DM. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature. 2015;517:302–310. doi: 10.1038/nature14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan QL, et al. Metabolomic signature associated with reproduction-regulated aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging. 2017;9:447–474. doi: 10.18632/aging.101170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs S, et al. A metabolic signature of long life in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Biol. 2010;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pontoizeau C, et al. Metabolomics analysis uncovers that dietary restriction buffers metabolic changes associated with aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:2910–2919. doi: 10.1021/pr5000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler JA, Mishur RJ, Bhaskaran S, Rea SL. A metabolic signature for long life in the Caenorhabditis elegans Mit mutants. Aging cell. 2013;12:130–138. doi: 10.1111/acel.12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao AW, et al. Identification of key pathways and metabolic fingerprints of longevity in C. elegans. Exp. Gerontol. 2018;113:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings J, et al. Multi-omics and genome-scale modeling reveal a metabolic shift during C. elegans aging. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirhaji L, et al. Revealing disease-associated pathways by network integration of untargeted metabolomics. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:770–776. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizzolo F, et al. Folic acid effects on S-adenosylmethionine, S-adenosylhomocysteine, and DNA methylation in patients with intermediate hyperhomocysteinemia. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2011;30:11–18. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2011.10719939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sae-Lee C, et al. Dietary intervention modifies DNA methylation age assessed by the epigenetic clock. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018;62:e1800092. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, Cantley LC. Toward a better understanding of folate metabolism in health and disease. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:253–266. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu YJ, et al. Glycine promotes longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans in a methionine cycle-dependent fashion. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan J, et al. Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature. 2014;510:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nature13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorelova V, et al. Dihydrofolate reductase/thymidylate synthase fine-tunes the folate status and controls redox homeostasis in plants. Plant Cell. 2017;29:2831–2853. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antosiewicz A, et al. Human dihydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthase form a complex in vitro and co-localize in normal and cancer cells. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017;35:1474–1490. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2016.1186560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schober AF, et al. A two-enzyme adaptive unit within bacterial folate metabolism. Cell Rep. 2019;27:3359–3370. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annibal A, Tam H, Latza C, Antebi A. Comparison of ESI-MS/MS and APCI-MS methods for the quantification of folic acid analogs in C. elegans. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019;54:316–327. doi: 10.1002/jms.4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D, et al. Folic acid impairs the uptake of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 2017;70:271–275. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietrzik K, Bailey L, Shane B. Folic acid and L-5-methyltetrahydrofolate: comparison of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:535–548. doi: 10.2165/11532990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moronetti Mazzeo LE, Dersh D, Boccitto M, Kalb RG, Lamitina T. Stress and aging induce distinct polyQ protein aggregation states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:10587–10592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108766109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabreiro F, et al. Metformin retards aging in C. elegans by altering microbial folate and methionine metabolism. Cell. 2013;153:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh S, Forney LA, Wanders D, Stone KP, Gettys TW. An integrative analysis of tissue-specific transcriptomic and metabolomic responses to short-term dietary methionine restriction in mice. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai Z, Mentch SJ, Gao X, Nichenametla SN, Locasale JW. Methionine metabolism influences genomic architecture and gene expression through H3K4me3 peak width. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1955. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang X, et al. Comprehensive profiling of amino acid response uncovers unique methionine-deprived response dependent on intact creatine biosynthesis. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heestand BN, et al. Dietary restriction induced longevity is mediated by nuclear receptor NHR-62 in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senchuk MM, et al. Activation of DAF-16/FOXO by reactive oxygen species contributes to longevity in long-lived mitochondrial mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tepper RG, et al. PQM-1 complements DAF-16 as a key transcriptional regulator of DAF-2-mediated development and longevity. Cell. 2013;154:676–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zecic, A. & Braeckman, B. P. DAF-16/FoxO in Caenorhabditis elegans and Its role in metabolic remodeling. Cells9, 10.3390/cells9010109 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tullet JM. DAF-16 target identification in C. elegans: past, present and future. Biogerontology. 2015;16:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10522-014-9527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selman C, et al. Evidence for lifespan extension and delayed age-related biomarkers in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice. FASEB J. 2008;22:807–818. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9261com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selman C, Partridge L, Withers DJ. Replication of extended lifespan phenotype in mice with deletion of insulin receptor substrate 1. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabil H, Kabil O, Banerjee R, Harshman LG, Pletcher SD. Increased transsulfuration mediates longevity and dietary restriction in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16831–16836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102008108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finkel T. The metabolic regulation of aging. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1416–1423. doi: 10.1038/nm.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Virk B, et al. Excessive folate synthesis limits lifespan in the C. elegans: E. coli aging model. BMC Biol. 2012;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virk B, et al. Folate acts in E. coli to accelerate C. elegans aging independently of bacterial biosynthesis. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1611–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathor L, Akhoon BA, Pandey S, Srivastava S, Pandey R. Folic acid supplementation at lower doses increases oxidative stress resistance and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Age. 2015;37:113. doi: 10.1007/s11357-015-9850-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DK, et al. Cell-to-cell transmission of polyglutamine aggregates in C. elegans. Exp. Neurobiol. 2017;26:321–328. doi: 10.5607/en.2017.26.6.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maitra, N. et al. Translational control of one-carbon metabolism underpins ribosomal protein phenotypes in cell division and longevity. eLife9, 10.7554/eLife.53127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Giese, G. E. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans methionine/S-adenosylmethionine cycle activity is sensed and adjusted by a nuclear hormone receptor. eLife9, 10.7554/eLife.60259 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Edwards C, et al. Mechanisms of amino acid-mediated lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Genet. 2015;16:8. doi: 10.1186/s12863-015-0167-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perrone CE, Malloy VL, Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Metabolic adaptations to methionine restriction that benefit health and lifespan in rodents. Exp. Gerontol. 2013;48:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun L, Sadighi Akha AA, Miller RA, Harper JM. Life-span extension in mice by preweaning food restriction and by methionine restriction in middle age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A. 2009;64:711–722. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayer AL, Fraker CA. The folate cycle as a cause of natural killer cell dysfunction and viral etiology in type 1 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2017;8:315. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou K, et al. Life span extension by glucose restriction is abrogated by methionine supplementation: cross-talk between glucose and methionine and implication of methionine as a key regulator of life span. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaba1306. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong Z, Sinha R, Richie JP., Jr. Disease prevention and delayed aging by dietary sulfur amino acid restriction: translational implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018;1418:44–55. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao X, et al. Dietary methionine influences therapy in mouse cancer models and alters human metabolism. Nature. 2019;572:397–401. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1437-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olsen T, et al. Effects of dietary methionine and cysteine restriction on plasma biomarkers, serum fibroblast growth factor 21, and adipose tissue gene expression in women with overweight or obesity: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot study. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:122. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02288-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee BC, et al. Methionine restriction extends lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster under conditions of low amino-acid status. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3592. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tain LS, et al. Longevity in response to lowered insulin signaling requires glycine N-methyltransferase-dependent spermidine production. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13043. doi: 10.1111/acel.13043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogawa T, et al. Stimulating S-adenosyl-l-methionine synthesis extends lifespan via activation of AMPK. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:11913–11918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604047113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parkhitko AA, Jouandin P, Mohr SE, Perrimon N. Methionine metabolism and methyltransferases in the regulation of aging and lifespan extension across species. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e13034. doi: 10.1111/acel.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ables GP, Johnson JE. Pleiotropic responses to methionine restriction. Exp. Gerontol. 2017;94:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruckenstuhl C, et al. Lifespan extension by methionine restriction requires autophagy-dependent vacuolar acidification. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]