Abstract

Background

Safe and effective long‐term treatments that reduce the need for corticosteroids are needed for Crohn's disease. Although purine antimetabolites are moderately effective for maintenance of remission patients often relapse despite treatment with these agents. Methotrexate may provide a safe and effective alternative to more expensive maintenance treatment with TNF‐α antagonists. This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review.

Objectives

To conduct a systematic review of randomized trials examining the efficacy and safety of methotrexate for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

Search methods

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PUBMED, EMBASE, and the Cochrane IBD/FBD Group Specialized Trials Register were searched from inception to June 9, 2014. Study references and review papers were also searched for additional trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared methotrexate to placebo or any other active intervention for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently reviewed studies for eligibility, extracted data and assessed study quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission as defined by the studies and expressed as a percentage of the total number of patients randomized (intention‐to‐treat analysis). We calculated the pooled risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes. The overall quality of the evidence supporting the primary outcome was assessed using the GRADE criteria.

Main results

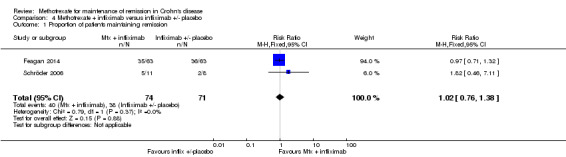

Five studies (n = 333 patients) were included in the review. Three studies were judged to be at low risk of bias. Two studies were judged to be at high risk of bias due to blinding. Intramuscular methotrexate was superior to placebo for maintenance of remission at 40 weeks follow‐up. Sixty‐five per cent of patients in the intramuscular methotrexate group maintained remission compared to 39% of placebo patients (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.67; 76 patients).The number needed to treat to prevent one relapse was four. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (40 events). There was no statistically significant difference in maintenance of remission at 36 weeks follow‐up between oral methotrexate (12.5 mg/week) and placebo. Ninety per cent of patients in the oral methotrexate group maintained remission compared to 67% of placebo patients (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.67; 22 patients). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was low due to very sparse data (17 events). A pooled analysis of two small studies (n = 50) showed no statistically significant difference in continued remission between oral methotrexate (12.5 mg to 15 mg/week) and 6‐mercaptopurine (1 mg/kg/day) for maintenance of remission. Seventy‐seven per cent of methotrexate patients maintained remission compared to 57% of 6‐mercaptopurine patients (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.00). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was very low due to high risk of bias in one study (no blinding) and very sparse data (33 events). One small (13 patients) poor quality study found no difference in continued remission between methotrexate and 5‐aminosalicylic acid (RR 2.62, 95% CI 0.23 to 29.79). A pooled analysis of two studies (n = 145) including one high quality trial (n = 126) found no statistically significant difference in maintenance of remission at 36 to 48 weeks between combination therapy (methotrexate and infliximab) and infliximab monotherapy. Fifty‐four percent of patients in the combination therapy group maintained remission compared to 53% of monotherapy patients (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.38, P = 0.95). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was low due to high risk of bias in one study (no blinding) and sparse data (78 events). Adverse events were generally mild in nature and resolved upon discontinuation or with folic acid supplementation. Common adverse events included nausea and vomiting, symptoms of a cold, abdominal pain, headache, joint pain or arthralgia, and fatigue.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate quality evidence indicates that intramuscular methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/week is superior to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Intramuscular methotrexate appears to be safe. Low dose oral methotrexate (12.5 to 15 mg/week) does not appear to be effective for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Combination therapy (methotrexate and infliximab) does not appear to be any more effective for maintenance of remission than infliximab monotherapy. The results for efficacy outcomes between methotrexate and 6‐mercaptopurine and methotrexate and 5‐aminosalicylic acid were uncertain. Large‐scale studies of methotrexate given orally at higher doses for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease may provide stronger evidence for the use of methotrexate in this manner.

Keywords: Humans; Administration, Oral; Crohn Disease; Crohn Disease/drug therapy; Drug Administration Schedule; Immunosuppressive Agents; Immunosuppressive Agents/administration & dosage; Immunosuppressive Agents/adverse effects; Injections, Intramuscular; Maintenance Chemotherapy; Maintenance Chemotherapy/methods; Methotrexate; Methotrexate/administration & dosage; Methotrexate/adverse effects; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Methotrexate for treatment of inactive Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the intestines that frequently occurs in the lower part of the small intestine, called the ileum. However, Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain and diarrhea. Prevention of clinical relapse (resumption of symptoms of active disease) in patients in remission is an important objective in the management of Crohn’s disease. Methotrexate is a drug that suppresses the body's natural immune responses and may suppress inflammation associated with Crohn’s disease. The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effectiveness and side effects of methotrexate used to maintain remission in Crohn's patients.

This review identified five studies that included a total of 333 participants. Two studies compared methotrexate (administered by pill or intramuscular injection) to a placebo (a sugar pill or a saline injection). One of these two studies also compared methotrexate to 6‐mercaptopurine (an immunosuppressive drug). One small study compared methotrexate to both 6‐mercaptopurine and 5‐aminosalicylic acid (an anti‐inflammatory drug). Two studies compared combination therapy with methotrexate and infliximab (a biological drug that is a tumour necrosis factor‐alpha antagonist) to infliximab used by itself. One high quality study (76 patients) shows that methotrexate (15 mg/week) injected intramuscularly (i.e. into muscles located in the arm or thigh) for 40 weeks is superior to placebo for preventing relapse (return of disease symptoms) among patients whose disease became inactive while taking higher doses of intramuscular methotrexate (25 mg/week). Side effects occurred in a small number of patients. These side effects are usually mild in nature and include nausea and vomiting, cold symptoms, abdominal pain, headache, joint pain and fatigue. One small study (22 patients) found no difference in continued remission between low dose methotrexate (12.5 mg/week) taken orally and placebo and suggests that low dose oral methotrexate is not an effective treatment for inactive Crohn's disease. However this result is uncertain due to the small number of patients assessed in the study. Large‐scale studies of methotrexate given orally at higher doses for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease may provide stronger evidence for the use of methotrexate in this manner. A pooled analysis of two studies (50 patients) found no difference in continued remission between oral methotrexate (12.5 to 15 mg/week) and 6‐mercaptopurine (1 mg/kg/day). No firm conclusions can be drawn as these results are uncertain due to poor study quality and small numbers of patients. A small study (13 patients) found no difference in continued remission between methotrexate and 5‐aminosalicylic acid. No conclusions can be drawn from this study as the results are very uncertain due to poor study quality and small numbers of patients. A pooled analysis of two studies (145 patients) found no difference in continued remission between combination therapy and infliximab. Combination therapy with methotrexate and infliximab does not appear to be any more effective for maintenance of remission than infliximab used by itself. This result is uncertain because one study was of poor quality (the other was high quality) and small numbers of patients.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Methotrexate compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Methotrexate compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with quiescent Crohn's disease Settings: Outpatient Intervention: Methotrexate Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Methotrexate | |||||

| Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission Follow‐up: 36‐40 weeks | 458 per 10001 | 720 per 1000 (504 to 1000) | RR 1.57 (1.10 to 2.23) | 98 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | |

| Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission (high dose intramuscular methotrexate 15 mg/week) Follow‐up: 40 weeks | 389 per 10001 | 650 per 1000 (408 to 1000) | RR 1.67 (1.05 to 2.67) | 76 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 | |

| Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission (low dose oral methotrexate 12.5 mg/week) Follow‐up: 36 weeks | 667 per 10001 | 900 per 1000 (574 to 1000) | RR 1.35 (0.86 to 2.12) | 22 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of study 2 Sparse data (57 events) 3 Sparse data (40 events) 4 Very sparse data (17 events)

Summary of findings 2. Methotrexate compared to 6‐mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Methotrexate compared to 6‐MP for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with quiescent Crohn's disease Settings: Outpatient Intervention: Methotrexate Comparison: 6‐MP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| 6‐MP | Methotrexate | |||||

| Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission Follow‐up: 36‐76 weeks | 571 per 10001 | 777 per 1000 (526 to 1000) | RR 1.36 (0.92 to 2.00) | 50 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of study 2 Lack of blinding in Maté‐Jiménez 2000 trial 3 Very sparse data (33 events)

Summary of findings 3. Methotrexate + infliximab compared to Infliximab +/‐ placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Methotrexate + infliximab compared to Infliximab +/‐ placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease Settings: Outpatient Intervention: Methotrexate + infliximab Comparison: Infliximab +/‐ placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Infliximab +/‐ placebo | Methotrexate + infliximab | |||||

| Proportion of patients maintaining remission Follow‐up: 36‐48 weeks | 535 per 10001 | 546 per 1000 (407 to 739) | RR 1.02 (0.76 to 1.38) | 145 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of study 2 Schröder 2006 is an open‐label trial 3 Sparse data (78 events)

Background

Crohn's disease is a condition of transmural intestinal inflammation that is often discontinuous and can involve any portion of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a chronic illness characterized by periods of remission and recurrences. Goals of management include control of acute exacerbation, induction of remission, and maintenance of remission.

Many patients require long‐term maintenance therapy to prevent relapse. Corticosteroids are not effective for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease (Steinhart 2003). Patients with steroid‐dependent or refractory disease require immunosuppressive agents to maintain disease remission. Although azathioprine and 6‐mercaptopurine are modestly effective for maintenance of remission, they can have significant toxicity (Chebli 2007; Prefontaine 2009).

Infliximab, a chimeric human‐murine monoclonal antibody against tumor‐necrosis factor‐alpha, is effective for maintenance of clinical remission in Crohn's disease (Hanauer 2002). It is administered intravenously and maintenance therapy usually requires regular repeat dosing (every 8 weeks). Although the safety profile of infliximab is considered to be favorable over the short‐term, the data on long‐term toxicity are still preliminary. In addition, the formation of antibodies to infliximab may lead to infusion reactions and reduced efficacy over time (Baert 2003). Infliximab is generally reserved for Crohn's disease patients who have had an inadequate response to standard therapies. This is due to the cost of drug acquisition, inconvenient intravenous dosing, and immunogenicity. Thus, other alternatives to infliximab may need to be considered for maintenance therapy.

Methotrexate, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, has been shown to be effective for induction of remission in Crohn's disease (Feagan 1995; Rampton 2001). Methotrexate has also been studied for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997; Schröder 2006). This systematic review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Patel 2009).

Objectives

To conduct a systematic review of randomized trials examining the efficacy and safety of methotrexate for maintenance of remission in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials comparing methotrexate with placebo or an active comparator (including randomized open‐label studies) were considered for inclusion. Studies published as abstracts were only included if the authors could be contacted for further information to allow for evaluation of quality and main outcomes. Any duration of follow‐up was allowed.

Types of participants

Adult patients (> 18 years of age) with chronic active Crohn's disease or quiescent Crohn's disease as defined by conventional clinical, radiographic and endoscopic criteria were eligible for inclusion. Patients were categorized as having active Crohn's disease (defined by a Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) of > 150)) with a response to induction therapy with methotrexate or another agent (e.g. infliximab) in the presence or absence of concomitant steroid therapy, and patients with Crohn's disease (either active or in remission) that were unable to wean corticosteroids.

Types of interventions

Methotrexate given by any route including oral, subcutaneous injection, intramuscular injection and intravenous infusion.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission as defined by the studies and expressed as a percentage of the total number of patients randomized (intention‐to‐treat analysis). Remission may be defined as a CDAI score of < 150 with or without the need for continued corticosteroid therapy.

Secondary outcome measures included: 1. Clinical relapse; 2. Time to clinical relapse; 3. Quality of life; and 4. Occurrence of adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

A computer assisted search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Cochrane IBD/FBD Review Group Specialized Trials Register and the on‐line databases MEDLINE and EMBASE was performed to identify relevant publications from inception to 9 June 2014. Manual searches of reference lists from potentially relevant papers were performed in order to identify additional studies that may have been missed using the computer assisted search strategy. Review articles and conference proceedings were also searched to identify additional studies. The search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection: The above search strategy was used to select potentially relevant trials (papers or abstracts). Two authors (YW and JKM) independently reviewed the selected trials and determined eligibility for inclusion based on the above criteria. Studies published in abstract form were only included if the authors could be contacted for further information.

Data extraction: Two authors (YW and JKM) independently extracted data. The outcome data of interest were the number of patients randomized into each treatment group and the number of patients in each group who failed to maintain remission. The numbers lost to follow‐up and the duration of follow‐up were also recorded. Treatment and control modalities were summarized, as were the demographics of the study population. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment

Two authors (YW and JKM) independently assessed the risk of bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Factors assessed included:

sequence generation (i.e. was the allocation sequence adequately generated?);

allocation sequence concealment (i.e. was allocation adequately concealed?);

blinding (i.e. was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?);

incomplete outcome data (i.e. were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?);

selective outcome reporting (i.e. are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?); and

other potential sources of bias (i.e. was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?).

A judgement of 'Yes' indicates low risk of bias, 'No' indicates high risk of bias, and 'Unclear' indicates unclear or unknown risk of bias. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Study authors were contacted when insufficient information was provided to determine risk of bias.

We used the GRADE criteria to assess the overall quality of evidence used for specific outcomes in this review. Evidence from randomized controlled trials begin as high quality evidence. They can then be downgraded due to: (1) risk of bias from the studies, (2) indirect evidence, (3) inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity), (4) imprecision in data, and (5) publication bias. The overall quality of evidence for each outcome was determined and classified as high quality (i.e. further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect); moderate quality (i.e. further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate); low quality (i.e. further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate); or very low quality (i.e. we are very uncertain about the estimate) (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011).

Statistical analysis Data were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3.3). Data were analyzed on an intention‐to‐treat basis, and treated dichotomously. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission as defined by the studies. Data were combined for analysis where appropriate. If a comparison was only assessed in a single trial, P‐values were derived using the Chi2 test. If the comparison was assessed in more than one trial, summary test statistics were derived by calculating the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using a fixed‐effect model. The presence of heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Chi2 test (a P value of 0.10 was regarded as statistically significant) and the I2statistic (Higgins 2003).

Results

Description of studies

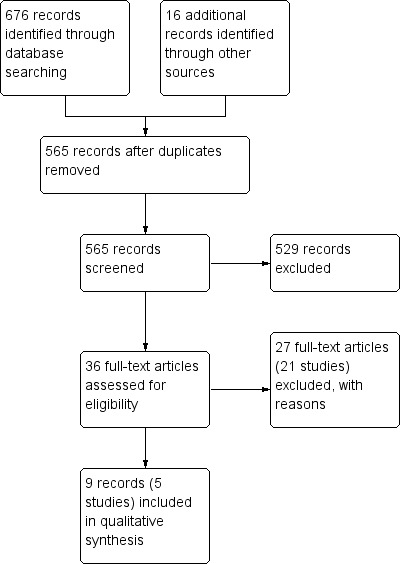

The literature search on 9 June 2014 identified 676 records (See Figure 1). Sixteen additional studies were identified through searching of other sources. After duplicates were removed, a total of 565 records remained for review of titles and abstracts. Two authors (YW and JKM) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these trials and 36 records were selected for full text review. Twenty‐seven of these records (21 studies) were excluded with reasons (See: Characteristics of excluded studies). Nine reports of five studies (333 patients) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997; Schröder 2006; See Characteristics of included studies table).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Feagan 2000 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study investigating the role of methotrexate for maintaining remission in Crohn's disease. Patients were given either methotrexate 15 mg/week intramuscularly (n = 40) or identical placebo (n = 36) for a total of 40 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of relapse at 40 weeks; secondary outcomes included the need for prednisone and adverse drug reactions. The patients were assessed every 4 weeks for a total of 40 weeks. The study medication was discontinued if a patient required treatment for active Crohn's disease. However, of the 36 patients that relapsed in the study, 22 were given methotrexate 25 mg intramuscularly once weekly, in addition to prednisone for treatment of the exacerbation. The intention‐to‐treat principle was used to analyze the results.

Feagan 2014 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial investigating the role of methotrexate when used in combination with infliximab for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Eligible patients needed to have a diagnosis of CD and initiated prednisone for active symptoms within the last six weeks. Patients were given either weekly subcutaneous injections of methotrexate (n = 63) or identical placebo (n = 63) for a total of 50 weeks. In addition, all patients (N = 126) received infliximab 5mg/kg intravenously at weeks 1, 3, 7, 14, 22, 30, 38, and 46. The primary outcome was the time to treatment failure, defined as failure to enter prednisone‐free remission (CDAI < 150) at week 14 or failure to maintain remission through week 50. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients who achieved overall treatment success, the proportion of patients who achieved prednisone‐free remission at week 14, the mean change in the CDAI and SF‐36 scores, the median change in serum C‐reactive protein (CRP) concentration, the median serum infliximab concentration, the proportion of patients who developed antibodies to infliximab, and the proportion of patients experiencing adverse events. Tapering of prednisone began at week 1 and all patients were required to discontinue prednisone by week 14. Aminosalicylates, budesonide, probiotics, systemic antibiotics for the treatment of luminal CD, immunosuppressives, investigational agents, parenteral nutrition, or topical aminosalicylates or corticosteroids were not permitted. Antibiotics were allowed for non‐CD indications and active perianal disease for a maximum of 14 consecutive days.

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 conducted a randomized, unblinded, single‐centre trial comparing 6‐mercaptopurine, methotrexate, and 5‐aminosalicylic acid for the treatment of steroid‐dependent inflammatory bowel disease. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the above medications' efficacy for inducing and maintaining remission in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. The trial duration was 106 weeks and the study was divided into two parts ‐ induction of remission for 30 weeks and maintenance of remission for 76 weeks. Seventy‐two patients were enrolled, including 34 patients with ulcerative colitis and 38 with Crohn's disease. None of the patients had received 6‐mercaptopurine or methotrexate prior to entering the study. Steroid‐dependency was defined as the inability to reduce the dose of prednisone to 20 mg per day without presenting with inflammatory activity (determined by a CDAI ≥ 200 or ≥ 2 episodes in the last 6 months or ≥ 3 episodes within the last 12 months). During the induction phase patients were assigned to receive oral treatment with 6‐mercaptopurine 1.5 mg/kg/day (n = 15), methotrexate 15 mg/week (n = 15), or 5‐aminosalicylic acid 3 g/day (n = 7). There was no placebo comparator. All patients were initially on an individually adjusted dose of prednisone (maximum dose 1 mg/kg/day). At the first patient assessment (week 2), the daily dose of prednisone was decreased by 8 mg/week if the patient's condition was deemed stable or improved. Prednisone was discontinued if clinical remission was achieved. After 30 weeks of induction treatment patients who entered remission were entered into a maintenance phase and were followed every 6 weeks for a total of 76 weeks. Crohn's patients who entered the maintenance phase included 12 methotrexate patients, 15 6‐mercaptopurine patients and 1 5‐aminosalicylic acid patient. Once clinical remission was achieved, the MTX dose was reduced to 10 mg/week, the 6‐MP dose was reduced to 1 mg/kg/day, and the 5‐ASA dose remained the same. Outcome measures included a CDAI every 24 weeks (weeks 54 and 78) and at the end of the maintenance of remission study (week 106), and elapse.

Oren 1997 conducted a randomized, double‐blind, controlled study comparing methotrexate, 6‐mercaptopurine, and placebo for the treatment of chronic, active Crohn's disease. Patients aged 17 to 75 years with chronic, active Crohn's disease who had been diagnosed for at least one year were included. Eighty‐four patients received either oral methotrexate at a dose of 12.5 mg per week (n = 26) or 6‐mercaptopurine 50 mg/day (n = 32) or placebo (n=26). 5‐aminosalicylic acid preparations were being used by 18 patients (72%) in the methotrexate group, 21 patients (63%) in the 6‐mercaptopurine group, and 18 patients (69%) in the placebo group. At entry steroids were being used by 20 patients (80%) in the methotrexate group, 26 patients (79%) in the 6‐mercaptopurine group, and 19 patients (73%) in the placebo group. Patients were assessed at weeks two, six and eight after randomization, and then every four weeks for nine months. The outcome measures were the proportion of patients entering first remission, the time to first remission, the proportion of patients maintaining remission up to nine month follow‐up, decrease in steroid requirements, quality of life as measured by the 'Treatment Goal Score' and adverse events. The Harvey‐Bradshaw index and the 'Treatment Goal Score' were assessed for each patient during each study visit to monitor response to therapy. Steroids were tapered at the direction of the treating physician with the goal of discontinuation within the first two to three months of the trial. Steroids could also be reintroduced or doses increased if deemed necessary.

Schröder 2006 conducted a randomized, open‐label, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of combination therapy with methotrexate and infliximab for treating patients with refractory Crohn's disease. To be eligible for the study, patients needed to be naive to TNF‐α antagonists at entry. Patients receiving stable doses 5‐aminosalicylates (> 4 g/day) or prednisone (< 40 mg/day) or both were also eligible for the study. All patients received infliximab at weeks 0 and 2; and those in methotrexate group received a 20 mg infusion per week at weeks 0 to 5, and then a weekly oral dose for 48 weeks. The primary outcome was clinical remission at the end of the trial (CDAI < 150). The secondary outcomes included time to achieve clinical remission and the corticosteroid‐tapering effect of treatment. Safety of the combination treatment was assessed using adverse events, clinical signs, and laboratory parameters at each visit.

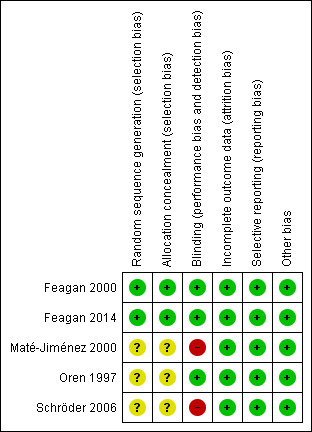

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of all studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

The risk of bias results are summarized in Figure 2. Two studies (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014) reported the methods used for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were rated as low risk of bias for those items (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014). Three studies were rated as low risk of bias for blinding (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014; Oren 1997). However, two studies were open label and were rated as high risk of bias for blinding ( Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Schröder 2006). All of the included trials were rated as low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data and selective reporting (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997; Schröder 2006). No other issues were found with the trials and they were rated as low risk of bias for the other bias item (Feagan 2000; Feagan 2014; Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997; Schröder 2006).

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Feagan 2000 After 40 weeks of treatment, relapse occurred in 14 of 40 (35%) patients assigned methotrexate and 22 of 36 (61%) patients given placebo (OR 0.36; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.87; P=0.02). The NNT (number needed to treat) to prevent one relapse was 4. The mean time to relapse with methotrexate was > 40 weeks, and with placebo it was 22 weeks. Of the 36 patients who relapsed, 22 were subsequently treated with intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg weekly. Twelve (55%) of these patients again were in remission at week 40 compared to 2 of 14 patients (14%) who were not treated with methotrexate after relapse. The overall incidence of adverse events was similar in both groups. Common adverse events included nausea and vomiting, symptoms of a cold, abdominal pain, headache, joint pain or arthralgia, and fatigue. None of the patients in the methotrexate group had a serious adverse event compared to two in the placebo group (cervical dysplasia and viral respiratory tract infection. One methotrexate patient withdrew from the study because of nausea.

Feagan 2014 With regard to the primary outcome, there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups. At week 50, the actuarial rate of treatment failure was 30.6% in the combination therapy group compared with 29.8% in the infliximab monotherapy group (P=0.63, 95% CI, 0.63‐2.17). The lack of difference was confirmed using a multiple Cox regression model with adjustments for CRP, CDAI, prednisone dose, and time since diagnosis at baseline (hazard ratio 1.35, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.67). In terms of secondary outcomes, no clinically meaningful differences were observed. At week 14, 76% of patients treated with the combination of infliximab and methotrexate achieved prednisone‐free remission compared with 78% of patients who received infliximab alone (P = 0.83). At week 50, thirty‐five of 63 patients (56%) in the combination treatment group maintained remission, compared to 36 of 63 patients (57%) in the infliximab alone group (P = 0.86).

Oren 1997 The proportion of patients entering first remission was 10 of 26 (38%) in the methotrexate group, 13 of 32 (41%) in the 6‐mercaptopurine group, and 12 of 26 (46%) in the placebo group. These differences were not statistically significant. Nine patients receiving methotrexate (90%, 95% CI 57% to >99.9%) maintained remission after induction compared to 8 patients receiving 6‐mercaptopurine (62%, 95% CI 35% to 82%) and 8 patients receiving placebo (67%, 95% CI 39% to 86%). There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups. The time to first remission and to first relapse data were similar in all groups (data not available). The methotrexate group did show a greater mean total time (months) in remission and proportion of total study time in remission, but the results were not statistically significant (data not available). One patient in the methotrexate group withdrew due to an adverse event (headache) compared to one patient in the 6‐MP group (leukopenia and stomatitis) and none in the placebo group.

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 After completing 30 weeks of induction therapy, 28 patients with Crohn's disease achieved remission, including 15 of 16 patients (94%) in the 6‐mercaptopurine group, 12 of 15 patients (80%) in the methotrexate group, and 1 of 7 patients (14%) in the 5‐aminosalicylic acid group. After 76 weeks of treatment 8 of 12 methotrexate patients maintained remission compared to 8 of 15 6‐mercaptopurine patients and zero 5‐aminosalicylic acid patients. These differences were not statistically significant. Maté‐Jiménez 2000 did not report adverse events separately for patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Adverse events experienced by patients who received methotrexate included nausea and dyspepsia, mild alopecia, mild increase in AST levels, peritoneal abscess, hypoalbuminemia, severe rash and atypical pneumonia. Three of 26 patients treated with methotrexate withdrew due to adverse events compared to 4 of 30 patients treated with 6‐mercaptopurine.

Schröder 2006 By week 48, 25% (2/8) of patients in the infliximab monotherapy group discontinued study due to lack of efficacy compared to 36% of patients in the combination therapy group. Clinical remission was observed in 45% of combination therapy patients compared to 25% of infliximab monotherapy patients (P = 0.63). In addition, combination therapy led to earlier remission (median time to remission: 2 weeks in combination group versus 18 weeks in monotherapy group, P = 0.08) and less steroid dependence compared to monotherapy (complete corticosteroid tapering at week 48: 7/7 in combination group versus 2/6 in monotherapy group, P = 0.02). No clinically significant differences in adverse events were reported.

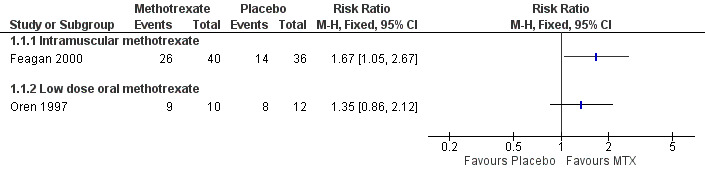

Primary outcome: maintenance of remission (including pooled analyses)

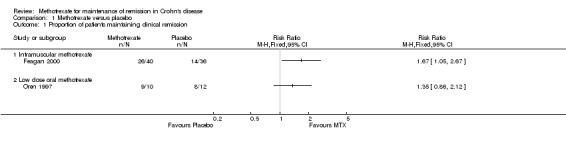

Methotrexate versus placebo Intramuscular methotrexate was superior to placebo for maintenance of remission at 40 weeks follow‐up. Sixty‐five per cent of patients in the intramuscular methotrexate group maintained remission compared to 39% of placebo patients (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.67; 1 study, 76 patients, See Figure 3). The number needed to treat to prevent one relapse was four. A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (40 events). There was no statistically significant difference in maintenance of remission at 36 weeks follow‐up between oral methotrexate (12.5 mg/week) and placebo. Ninety per cent of patients in the oral methotrexate group maintained remission compared to 67% of placebo patients (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.67; 1 study, 22 patients, See Figure 3). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence supporting this outcome was low due to very sparse data (17 events).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Methotrexate versus Placebo, outcome: 1.1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission.

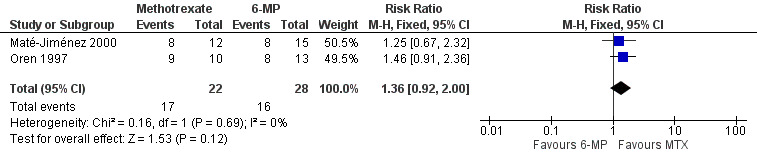

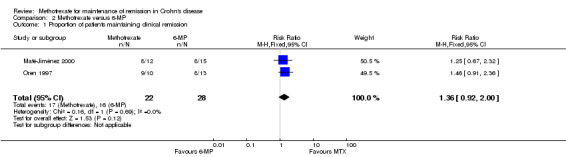

Methotrexate versus 6‐mercaptopurine A total of 50 patients were included in the pooled analysis (Maté‐Jiménez 2000; Oren 1997). More patients who were assigned to methotrexate (77%, 17/22) maintained remission compared to patients who received 6‐MP (57%, 16/28). However, this difference was not statistically significant (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.00; See Figure 4). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence for this outcome was very low due to very sparse data (17 events) and lack of blinding in the Maté‐Jiménez 2000 trial.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Methotrexate versus 6‐MP, outcome: 2.1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission.

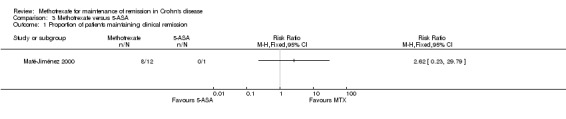

Methotrexate versus 5‐aminosalicylic acid A total of 13 patients were included in the analysis (Maté‐Jiménez 2000). More patients who were assigned to methotrexate (67%, 8/12) maintained remission compared to patients who received 5‐aminosalicylic acid (0%, 0/1). However, this difference was not statistically significant (RR 2.62, 95% CI 0.23 to 29.79).

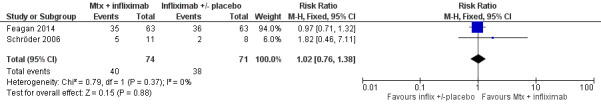

Methotrexate + infliximab versus infliximab +/‐ placebo A total of 145 patients were included in the pooled analysis (Feagan 2014; Schröder 2006). After 36 to 48 weeks of treatment, 54% (40/74) of patients treated with methotrexate and infliximab maintained remission compared to 54% (38/71) of patients treated with infliximab alone. The pooled risk ratio for maintenance of remission was 1.02 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.38; See Figure 5). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of evidence was very low due to very sparse data (67 events) and open‐label design in Schröder 2006 study.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Methotrexate + infliximab versus infliximab +/‐ placebo, outcome: 4.1 Proportion of patients maintaining remission.

Discussion

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gut that is characterized by periods of remission and exacerbations. Once remission is induced, patients often require long‐term maintenance therapy in order to prevent relapse and avoid chronic corticosteroid use. This generally requires the use of immunosuppressive agents (as steroid sparing agents).

Methotrexate, an immunosuppressive, is an effective drug for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease (Feagan 1995; McDonald 2014). Accordingly, current practice guidelines recommend the use of methotrexate for this purpose (Lichtenstein 2006).

Five randomized, controlled studies that investigated the efficacy of methotrexate for maintenance of remission of Crohn’s disease were identified for this review. The five studies differed significantly with respect to methodology. Two studies investigated the efficacy of methotrexate compared to placebo. Feagan 2000 was a well‐designed trial that establishes methotrexate as an effective and safe drug for maintenance therapy in Crohn’s disease. This study had the largest number of patients and used intramuscular injections of methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg weekly. The trial showed that in Crohn’s patients who had been induced into remission with methotrexate, significantly more patients remained in remission while taking methotrexate compared to placebo. The other study, Oren 1997, also compared methotrexate to placebo. Oren 1997 used oral methotrexate at a lower dose (12.5 mg weekly) and showed no difference between patients treated with methotrexate or placebo. The lower dose of methotrexate, oral route of administration, and small patient population may have been factors contributing to the lack of benefit seen with methotrexate.

Two studies compared methotrexate to 6‐mercaptopurine. Maté‐Jiménez 2000 was a randomized, controlled trial that used oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly in patients that had achieved remission on a higher dose (15 mg orally weekly). When compared to patients treated with 6‐mercaptopurine, there was no statistically significant difference with respect to maintenance of remission. Oren 1997 also did not show a statistically significant difference in continued remission between the methotrexate and 6‐mercaptopurine groups. Although methotrexate was superior to 6‐mercaptopurine in a pooled analysis of both studies, the difference was not statistically significant. A GRADE analysis indicates that the evidence supporting this outcome is of very low quality due to sparse data (57 events) and high risk of bias (due to blinding) in the Maté‐Jiménez 2000 study. Both of these studies used a low dose of oral methotrexate and enrolled small numbers of patients. Neither of these studies used a power calculation to determine how many patients needed to be enrolled to be able to detect clinically important differences between study groups.

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 also compared oral methotrexate to 5‐aminosalicylic acid. Thirteen patients were included in this analysis and no conclusions can be drawn from these results.

Two clinical trials studied the effects of methotrexate in combination with infliximab on maintenance of remission of Crohn's disease (Feagan 2014; Schröder 2006). Feagan 2014 was a well‐designed adequately powered trial, however, it did not find any significant clinical benefits for combination therapy relative to infliximab monotherapy. A pooled analysis of both studies suggests that there is no difference in continued remission between combination therapy and infliximab monotherapy groups. A GRADE analysis indicates that the evidence supporting this outcome is of low quality due to sparse data (78 events) and high risk of bias (due to blinding) in the Schröder 2006 study.

Only one study examined the effect of methotrexate on quality of life. In Oren 1997, an analysis of the 'Treatment Goal Score' revealed that patients treated with methotrexate did better than the other groups with respect to general well‐being and abdominal pain. Although these results need to be interpreted cautiously, the trend towards improvement in quality of life parameters is encouraging.

In Feagan 2000, there were no severe adverse events reported in the methotrexate group. Maté‐Jiménez 2000 had three patients withdraw due to adverse events associated with methotrexate use. All symptoms resolved and laboratory values normalized after the medications were discontinued. Folic acid supplementation was used in the methotrexate group to treat mild side effects. There were also no statistically significant differences in withdrawals and adverse events between the treatment groups in Oren 1997. The three studies suggest that methotrexate is safe and well tolerated with most minor adverse drug events being managed by folic acid supplementation.

One well‐designed trial provides evidence that methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg intramuscularly weekly is safe and effective for maintenance of remission in quiescent Crohn’s disease (Feagan 2000). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall quality of the evidence supporting this outcome was moderate suggesting that further research may have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effects. The Maté‐Jiménez 2000 and Oren 1997 studies suggest that lower dose oral methotrexate is safe, but failed to show a benefit.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Moderate quality evidence indicates that intramuscular methotrexate at a dose of 15 mg/week is superior to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Intramuscular methotrexate appears to be safe. Intramuscular and subcutaneous routes have similar pharmacokinetics; however, self‐injecting via a subcutaneous route may be easier and better tolerated by patients (Balis 1988; Egan 1999b; Arthur 2002). Accordingly, methotrexate is usually administered subcutaneously in practice. Low dose oral methotrexate (12.5 to 15 mg/week) does not appear to be effective for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Combination therapy (methotrexate and infliximab) does not appear to be any more effective for maintenance of remission than infliximab monotherapy. The results for efficacy outcomes between methotrexate and 6‐mercaptopurine and methotrexate and 5‐aminosalicylic acid were uncertain.

Implications for research.

Large‐scale studies of methotrexate given orally at higher doses for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease may provide stronger evidence for the use of methotrexate in this manner. In addition, studies investigating absorption of methotrexate in the gastrointestinal tract may help determine which patients can be treated orally.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 June 2014 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantively updated review with new conclusions and authors |

| 9 June 2014 | New search has been performed | New literature search was conducted on June 9, 2014. Two new studies included in the review |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2008 Review first published: Issue 4, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

Funding for the IBD/FBD Review Group (September 1, 2010 ‐ August 31, 2015) has been provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Knowledge Translation Branch (CON ‐ 105529) and the CIHR Institutes of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD); and Infection and Immunity (III) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (HLTC3968FL‐2010‐2235).

Miss Ila Stewart has provided support for the IBD/FBD Review Group through the Olive Stewart Fund.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search Strategies

MEDLINE search strategy

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. crossover procedure/

14. double blind procedure/

15. single blind procedure/

16. triple blind procedure/

17. randomized controlled trial/

18. or/1‐17

19 (CROHN or crohn's).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

20. inflammatory bowel disease*.ti. or inflammatory bowel disease*.ab. or IBD.ti. or IBD.ab.

21. 19 or 20

22. 18 and 21

23. methotrexate.mp. or exp methotrexate derivative/ or exp methotrexate/ or exp methotrexate gamma aspartic acid/ or exp methotrexate polyglutamate/

24. 22 and 23

EMBASE search strategy

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. crossover procedure/

14. double blind procedure/

15. single blind procedure/

16. triple blind procedure/

17. randomized controlled trial/

18. or/1‐17

19 (CROHN or crohn's).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

20. inflammatory bowel disease*.ti. or inflammatory bowel disease*.ab. or IBD.ti. or IBD.ab.

21. 19 or 20

22. 18 and 21

23. methotrexate.mp. or exp methotrexate derivative/ or exp methotrexate/ or exp methotrexate gamma aspartic acid/ or exp methotrexate polyglutamate/

24. 22 and 23

CENTRAL search strategy

#1 crohn* or "inflammatory bowel disease" or IBD

#2 methotrexate

#3 #1 and #2

SR‐IBD

Crohn AND methotrexate

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Methotrexate versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Intramuscular methotrexate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.04, 0.48] | |

| 1.2 Low dose oral methotrexate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.23 [‐0.09, 0.56] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Methotrexate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission.

Comparison 2. Methotrexate versus 6‐MP.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission | 2 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.92, 2.00] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Methotrexate versus 6‐MP, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission.

Comparison 3. Methotrexate versus 5‐ASA.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Methotrexate versus 5‐ASA, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients maintaining clinical remission.

Comparison 4. Methotrexate + infliximab versus infliximab +/‐ placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of patients maintaining remission | 2 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.76, 1.38] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Methotrexate + infliximab versus infliximab +/‐ placebo, Outcome 1 Proportion of patients maintaining remission.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Feagan 2000.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial; multi‐centre | |

| Participants | Patients with chronically, active Crohn's disease in whom remission was induced with intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg once weekly for a minimum of 16 weeks (N = 76) Remission was defined as the absence of the need for prednisone therapy and a Crohn's Disease Activity Index score of 150 or less |

|

| Interventions | Methotrexate 15 mg IM weekly (n = 40) vs. placebo (n = 36) for a total of 40 weeks Other treatments for Crohn's disease including aminosalicylates, antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, infliximab, tube feeding, or parenteral nutrition were not permitted |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: occurrence of a relapse of Crohn’s disease at 40 weeks (defined as an increase in the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score of at least 100 points above the base‐line value or the initiation of prednisone, an antimetabolite, or the two in combination for the treatment of symptoms of Crohn’s disease) Secondary outcomes: need for prednisone therapy, the proportion of patients that reentered remission after being treated with a higher dose of MTX (25 mg IM weekly) for relapse, adverse drug events All data analysis was performed on an intention to treat basis |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated randomization code |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment was adequate. Medication was administered in coded identical pre‐filled vials which were administered serially to participants |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Active and placebo medications were identical in appearance and were prepared in prefilled vials Clinical data were independently reviewed by two investigators who were unaware of the patients' treatment assignments |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There was only one drop‐out. A patient withdrew from the methotrexate group due to an adverse event (nausea) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The published report includes all expected outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Feagan 2014.

| Methods | Randomized, multi‐center, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | Patients with a diagnosis of CD who had initiated prednisone (15 to 40 mg/day) for active symptoms within 6 weeks of the screening visit (N = 126) | |

| Interventions | Weekly subcutaneous injections of methotrexate (initially 10 mg/wk, escalating to 25 mg/wk, n = 63) or identically appearing placebo (n = 63) Infliximab 5 mg/kg of body weight given intravenously at weeks 1, 3, 7, 14, 22, 30, 38, and 46. (with 200 mg hydrocortisone prophylaxis for infusion reaction) Aminosalicylates, budesonide, probiotics, systemic antibiotics for the treatment of luminal CD, immunosuppressives, investigational agents, parenteral nutrition, or topical aminosalicylates or corticosteroids were not permitted Antibiotics were allowed for non‐CD indications and active perianal disease for a maximum of 14 consecutive days. |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcome: the time to treatment failure (defined as failure to enter prednisone‐free remission (CDAI <150) at week 14 or failure to maintain remission through week 50 The occurrence of a relapse was defined by a CDAI score of 150 or greater and an increase in the CDAI score of 70 or more points higher than the week 14 score or the initiation of new medical or surgical therapy for the treatment of active CD Secondary outcomes: the proportion of patients who achieved overall treatment success (defined by achieving prednisone‐free remission at week 14 and maintenance of this remission through week 50), the proportion of patients who achieved prednisone‐free remission at week 14, the mean change in the CDAI and SF‐36 scores, the median change in serum CRP concentration, the median serum infliximab concentration, the proportion of patients who developed antibodies to infliximab, and the proportion of patients experiencing adverse events |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated randomization in 1:1 ratio |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralized randomization |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Active and placebo medications were identical in appearance |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Six patients withdrew from the study for reasons not related to treatment failure; 2 of these patients were assigned to methotrexate (both patients withdrew because of adverse events) and 4 patients were assigned to placebo (2 patients withdrew consent, 1 patient withdrew because of an adverse event, and 1 patient was lost to follow‐up evaluation) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The published study includes all expected outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of biases |

Maté‐Jiménez 2000.

| Methods | Randomized, single‐centre, 3‐arm trial This study was not blinded |

|

| Participants | Patients who achieved clinical remission in the induction of remission portion of the study (at 30 weeks) were included in the 76 week maintenance of remission study Patients participating in the maintenance study (N = 28) included: 12 MTX patients, 15 6‐MP patients and 1 5‐ASA patient |

|

| Interventions | Maintenance of remission study: MTX 10 mg PO weekly vs. 6‐MP PO 1 mg/kg/day vs. 5‐ASA PO 3 g/day | |

| Outcomes | Remission: prednisone stopped and CDAI < 150 and normal serum orosomucoid concentration at 30 weeks (normal value to 88 mg/dl) Relapse: CDAI > 150 and serum orosomucoid concentration > 100 with no response to 6 g/day 5‐ASA and need of prednisone therapy at 76 weeks (or week 106 of the study) Adverse events |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The manuscript does not describe the method used for randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The manuscript does not describe methods used for allocation concealment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding was not used |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A similar proportion of MTX and 6‐MP patients dropped out of the remission study due to relapse |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The published report included all expected outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Oren 1997.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multi‐center trial | |

| Participants | Chronic active Crohn's disease (HBI > 7), on steroids (> 7.5 mg/day; prednisone equivalent dose) and/or immunosuppressives for at least 4 months during the past year, no immunosuppressives 3 months prior to entry Unacceptable steroid side effects or failure to respond to high‐dose steroids were also considered reasons for inclusion (N = 84) | |

| Interventions | Oral methotrexate (12.5 mg/wk, n = 26), 6‐mercaptopurine (50 mg/day, n = 32) or placebo (n = 26) for 9 months Prednisone and 5‐ASA were continued at the discretion of the physician | |

| Outcomes | Remission (HBS < 3) and not receiving steroids Maintenance of remission in patients entering first remission up to the 9 month follow‐up Relapse was defined as a rise of 3 or more points on the HBI and/or a reintroduction of steroids at a dose of > 300 mg/month Decrease in steroid requirement General well being All data analysis was performed on an intention to treat basis |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The manuscript does not describe the method used for randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The manuscript does not describe methods used for allocation concealment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The investigators were blinded to treatment assignment An unblinded independent observer and the pharmacist were the only persons who had access to the drug key |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropouts and treatment failures were not significantly different between the three groups ITT analysis was used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The published report included all expected outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Schröder 2006.

| Methods | Randomized, open‐label, pilot study | |

| Participants | Eligible patients had a history of chronic active CD, as defined by refractoriness to or dependency on corticosteroids and resistance or intolerance to azathioprine (N = 19) | |

| Interventions | Infliximab infusion, 5 mg/kg (week 0 and 2) for all patients Methotrexate 20 mg/week (IV infusions for weeks 0 to 5, then switch to oral administration) for patients randomly assigned at study entry (n = 11) Patients in the control group did not receive a methotrexate placebo (n = 8) |

|

| Outcomes | The primary outcome: clinical remission at the end of the trial as defined by a CDAI score of less than 150 Secondary outcomes: the time to clinical remission and the corticosteroid‐tapering effect of treatment Safety parameters: incidence of adverse events, changes in vital signs, and routine laboratory measures monitored during each infusion and at each study visit |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The published report did not describe the method used for randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The methods used for allocation concealment were not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The study design was open‐label |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients were accounted for in the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported in the published reports |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appeared to be free of other sources of biases |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ardizzone 2003 | A randomized, active comparator controlled, induction of remission study (IV methotrexate 25 mg/week versus azathioprine 2 mg/kg/day) |

| Arora 1999 | A randomized, placebo‐controlled, induction of remission study (oral methotrexate 15 mg/week) |

| Clark 2005 | A retrospective chart review |

| Domènech 2008 | A retrospective chart review |

| Egan 1999a | A randomized, dose ranging induction study (15 mg/week versus 25 mg/week IM methotrexate) |

| Feagan 1995 | A randomized, placebo‐controlled, induction of remission study (intramuscular methotrexate 25mg/week) |

| Fishman 2001 | A commentary on Feagan 2000 study |

| Hayee 2005 | A case series report |

| Houben 1994 | A retrospective chart review |

| Kurnik 2003 | A randomized, pharmacokinetic study |

| Lahaire 2011 | A non‐randomized prospective study evaluating mucosal healing as the primary outcome |

| Lampen‐Smith 2011 | A retrospective chart review |

| Lémann 2000 | The study was not randomized and there was no control group |

| Martreau 2000 | A commentary for Feagan 2000 study |

| Roseau 2000 | A commentary for Feagan 2000 study |

| Roznowski 2001 | A commentary for Feagan 2000 study |

| Schröder 1996 | A commentary for Feagan 1995 study |

| Suares 2012 | The study was not a randomized control trial |

| Sun 2005 | A review article |

| Wilson 2013 | A pharmacokinetic study |

| Yang 2001 | A commentary for Feagan 2000 study |

Declarations of interest

Nilesh Chande has received fees for consultancy from Abbott/AbbVie and Ferring, fees for lectures from Abbott and Janssen, travel expenses from Merck and has stock/stock options in Pfizer, Glaxo Smith Kline, Proctor and Gamble and Johnson and Johnson. All of these financial activities are outside the submitted work.

John WD McDonald was a coauthor of one of the original publications reviewed in the preparation of this Cochrane review.

The other authors have no known declarations of interest.

New search for studies and content updated (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

Feagan 2000 {published data only}

- Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, Steinhart AH, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2000;342(22):1627‐32. [PUBMED: 2000197470] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild GE, Sutherland LR, Steinhart AH, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2000;118(4 Suppl 2):A190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feagan 2014 {published data only}

- Feagan B, McDonald JW, Panaccione R, Enns RA, Bernstein CN, Ponich TP, et al. A randomized trial of methotrexate in combination with infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2008;135(1):294‐5. [Google Scholar]

- Feagan BG, McDonald JWD, Panaccione R, Enns R, Bernstein CN, Ponich T, et al. A randomized trial of methotrexate in combination with infliximab for the treatment of Crohn's disease. United European Gastroenterology Week. Vienna, Austria, 2008:Abstract OP301.

- Feagan BG, McDonald JWD, Panaccione R, Enns RA, Bernstein CN, Ponich TP, et al. Methotrexate in combination with infliximab is no more effective than infliximab alone in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146(3):681‐8. [PUBMED: 24269926] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maté‐Jiménez 2000 {published data only}

- Hermida C, Cantero J, Moreno‐Otero R, Maté‐Jiménez J. Methotrexate and 6‐mercaptopurine in steroid‐dependent inflammatory bowel disease patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. 1999 Gut;45(Suppl V):A132. [Google Scholar]

- Maté‐Jiménez J, Hermida C, Cantero‐Perona J, Moreno‐Otero R. 6‐Mercaptopurine or methotrexate added to prednisone induces and maintains remission in steroid‐dependent inflammatory bowel disease. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2000;12(11):1227‐33. [PUBMED: 11111780] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oren 1997 {published data only}

- Oren R, Moshkowitz M, Odes S, Becker S, Keter D, Pomeranz I, et al. Methotrexate in chronic active Crohn's disease: a double‐blind, randomized, Israeli multicenter trial. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1997;92(12):2203‐9. [PUBMED: 1997381066] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schröder 2006 {published data only}

- Schröder O, Blumenstein I, Stein J. Combining infliximab with methotrexate for the induction and maintenance of remission in refractory Crohn's disease: a controlled pilot study. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2006;18(1):11‐6. [PUBMED: 16357613] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ardizzone 2003 {published data only}

- Ardizzone S, Bollani S, Manzionna G, Imbesi V, Colombo E, Bianchi Porro G. Comparison between methotrexate and azathioprine in the treatment of chronic active Crohn's disease: a randomised, investigator‐blind study. Digestive and Liver Disease 2003;35(9):619‐27. [PUBMED: 14563183] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzone S, Bollani S, Manzionna G, Molteni P, Bareggi E, Bianchi Porro G. Controlled trial comparing intravenous methotrexate and oral azathioprine for chronic active Crohn's disease: preliminary report. Gastroenterology 1999;116(4 (Part 2)):A662‐3. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Porro G, Ardizzone S, Bollani S, Duca A, Manzionna G, Molteni P. Controlled trial comparing intravenous methotrexate and oral azathioprine for chronic active Crohn's disease: preliminary report. Gut 1982;23(10):295. [Google Scholar]

Arora 1999 {published data only}

- Arora S, Katkov W, Cooley J, Kemp JA, Johnston DE, Schapiro RH, et al. Methotrexate in Crohn's disease: results of a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46(27):1724‐9. [PUBMED: 10430331] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Katkov WN, Cooley J, Kemp A, Schapiro RH, Kelsey PB, et al. A double blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of methotrexate in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1992;102(4 Part 2):A591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clark 2005 {published data only}

- Clark LL, Lightbody E, Morgan A, Gaya D, Winter JW, Gillespie RJ. The efficacy of long term intramuscular methotrexate in difficult to treat Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2005;136(5 Suppl 1):A659. [Google Scholar]

Domènech 2008 {published data only}

- Domènech E, Mañosa M, Navarro M, Masnou H, Garcia‐Planella E, Zabana Y, et al. Long‐term methotrexate for Crohn's disease: safety and efficacy in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2008;42(4):395‐9. [PUBMED: 18277899] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egan 1999a {published data only}

- Egan L, Sandborn W, Tremaine W, Leighton J, Mays D, Pike M, et al. A randomized, single‐blind, pharmacokinetic and dose response study of subcutaneous methotrexate, 15 and 25 mg/week, for refractory ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1998;114(4 Pt2):A‐227. [Google Scholar]

- Egan LJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Leighton JA, Mays DC, Pike MG, et al. A randomized dose‐response and pharmacokinetic study of methotrexate for refractory inflammatory Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1999;13(12):1597‐604. [PUBMED: 10594394] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feagan 1995 {published data only}

- Feagan BG, North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators. A Multicentre trial of methotrexate (MTX) for chronically active Crohn's disease (CD). Gut 1994;35 Suppl 4:A121. [Google Scholar]

- Feagan BG, Rochon J, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of Crohn's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 1995;332(5):292‐7. [PUBMED: 7816064] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigators, T.N.A.C.s.S.G. A multicentre trial of methotrexate (MTX) treatment for chronically active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1994;106(4 Part 2):A745. [Google Scholar]

Fishman 2001 {published data only}

- Fishman M. Methotrexate and maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology 2001;15(7):428. [PUBMED: 11493943] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hayee 2005 {published data only}

- Hayee BH, Harris AW. Methotrexate for Crohn's disease: experience in a district general hospital. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2005;17(9):893‐8. [PUBMED: 16093864] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Houben 1994 {published data only}

- Houben MH, Wijk HJ, Driessen WM, Spreeuwel JP. Methotrexate as possible treatment in refractory chronic inflammatory intestinal disease. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 1994;138(51):2552‐6. [PUBMED: 7830804] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kurnik 2003 {published data only}

- Kurnik D, Loebstein R, Fishbein E, Almog S, Halkin H, Bar‐Meir S, et al. Bioavailability of oral vs. subcutaneous low‐dose methotrexate in patients with Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2003;18(1):57‐63. [PUBMED: 12848626] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lahaire 2011 {published data only}

- Laharie D, Reffet A, Belleannée G, Chabrun E, Subtil C, Razaire S. Mucosal healing with methotrexate in Crohn's disease: a prospective comparative study with azathioprine and infliximab. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2011;33(6):714‐21. [PUBMED: 21235604] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lampen‐Smith 2011 {published data only}

- Lampen‐Smith A, Khan I, Claydon A. Methotrexate in patients with Crohn's disease: a regional experience. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2011;26:61‐2. [PUBMED: 70627238] [Google Scholar]

Lémann 2000 {published data only}

- Lémann M, Zenjari T, Bouhnik Y, Cosnes J, Mesnard B, Rambaud JC, et al. Methotrexate in Crohn's disease: long‐term efficacy and toxicity. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000;95(7):1730‐4. [PUBMED: 10925976] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martreau 2000 {published data only}

- Martreau P. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators [Demonstration de l'efficacite du methotrexate par voie parenterale pour maintenir en remission la maladie de Crohn]. Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique 2000;24(12):1243‐4. [PUBMED: 11277090] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roseau 2000 {published data only}

- Roseau E. Crohn's disease: prevention of relapse with methotrexate or growth hormone [Maladie de Crohn: Prevention des rechutes par le methotrexate ou l'hormone de croissance]. Presse Medicale 2000;29(30):1652‐3. [PUBMED: 11089504] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roznowski 2001 {published data only}

- Roznowski AB, Dignass A. Sustaining remission in Crohn disease with methotrexate‐‐a placebo controlled study [Remissionserhaltung bei Morbus Crohn mit Methotrexat‐‐eine plazebokontrollierte Untersuchung]. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie 2001;39(3):265‐7. [PUBMED: 11324144] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schröder 1996 {published data only}

- Schröder O, Stein J. Methotrexate in therapy of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases [Methotrexat (MTX) in der Therapie chronische‐entzundlicher Darmerkrankungen]. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie 1996;34(7):457‐8. [PUBMED: 8928541] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suares 2012 {published data only}

- Suares NC, Hamlin PJ, Greer DP, Warren L, Clark T, Ford AC. Efficacy and tolerability of methotrexate therapy for refractory Crohn's disease: a large single‐centre experience. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2012;35(2):284‐91. [PUBMED: 22112005] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sun 2005 {published data only}

- Sun JH, Das KM. Low‐dose oral methotrexate for maintaining Crohn's disease remission: where we stand. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2005;39(9):751‐6. [PUBMED: 16145336] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wilson 2013 {published data only}

- Wilson A, Patel V, Chande N, Ponich T, Urquhart B, Asher L, et al. Pharmacokinetic profiles for oral and subcutaneous methotrexate in patients with Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2013;37(3):340‐5. [PUBMED: 23190184] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yang 2001 {published data only}

- Yang YX, Lichtenstein GR. Methotrexate for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2001;120(6):1553‐5. [PUBMED: 11313329] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Arthur 2002

- Arthur V, Jubb R, Homer D. A study of parenteral use of methotrexate in rheumatic conditions. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2002;11(2):256‐63. [PUBMED: 11903725] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baert 2003

- Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Assche G, D' Haens G, Carbonez A, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long‐term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2003;348(7):601‐8. [PUBMED: 12584368] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Balis 1988

- Balis FM, Mirro J Jr, Reaman GH, Evans WE, McCully C, Doherty KM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous methotrexate. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1988;6(12):1882‐6. [PUBMED: 3199171] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chebli 2007

- Chebli JM, Gaburri PD, Souza AF, Pinto AL, Chebli LA, Felga GE, et al. Long‐term results with azathioprine therapy in patients with corticosteroid‐dependent Crohn's disease: open‐label prospective study. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2007;22(2):268‐74. [PUBMED: 17295882] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egan 1999b

- Egan LJ, Sandborn WJ, Mays DC, Tremaine WJ, Fauq AH, Lipsky JJ. Systemic and intestinal pharmacokinetics of methotrexate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1999;65(1):29‐39. [PUBMED: 9951428] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Alonso‐Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hanauer 2002

- Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359(9317):1541‐9. [PUBMED: 12047962] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [PUBMED: 12958120] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

Lichtenstein 2006