Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is a heavy metal of great public health concern. Recent studies suggested a link between Cd exposure and cognitive decline in humans. The ε4 allele, compared with the common ε3 allele, of the human apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE) is associated with accelerated cognitive decline and increased risks for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). To investigate the gene-environment interactions (GxE) between ApoE-ε4 and Cd exposure on cognition, we used a mouse model of AD that expresses human ApoE-ε3 (ApoE3-KI [knock-in]) or ApoE-ε4 (ApoE4-KI). Mice were exposed to 0.6 mg/l CdCl2 through drinking water for 14 weeks and assessed for hippocampus-dependent memory. A separate cohort was sacrificed immediately after exposure and used for Cd measurements and immunostaining. The peak blood Cd was 0.3–0.4 µg/l, within levels found in the U.S. general population. All Cd-treated animals exhibited spatial working memory deficits in the novel object location test. This deficit manifested earlier in ApoE4-KI mice than in ApoE3-KI within the same sex and earlier in males than females within the same genotype. ApoE4-KI but not ApoE3-KI mice exhibited reduced spontaneous alternation later in life in the T-maze test. Finally, Cd exposure impaired neuronal differentiation of adult-born neurons in the hippocampus of male ApoE4-KI mice. These data suggest that a GxE between ApoE4 and Cd exposure leads to accelerated cognitive impairment and that impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis may be one of the underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, male mice were more susceptible than female mice to this GxE effect when animals were young.

Keywords: cadmium, neurotoxicity, ApoE, cognition

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder which exhibits accelerated cognitive decline and memory loss over years, placing a heavy burden on society (Reitz et al., 2011). The majority of all AD cases are sporadic and late onset. Although the exact etiology remains unclear, late-onset AD is most likely caused by a combination of genetic and environmental risk factors (Reitz et al., 2011). A gene-environment interaction (GxE) between genetic risk factors and environmental risk factors may lead to more severe or accelerated cognitive decline. However, there is a paucity of data supporting this hypothesis (Piaceri et al., 2013).

Most AD cases are non-familial with the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE4) being the strongest known genetic modulators of risk (Piaceri et al., 2013). There are three human ApoE alleles: ε2, ε3, and ε4, with an allele frequency of 8.4%, 77.9%, and 13.7%, respectively. ApoE4 is associated with increased risk for AD relative to the common ApoE3 allele (Bu, 2009; Liu et al., 2013). However, the presence of the ApoE4 allele is not sufficient for the development of AD, suggesting that additional risk factors must interact with ApoE4 to increase AD risks (Reitz et al., 2011).

Cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal that is released into the environment through both natural processes and human activities resulting in accumulation in plants including leafy vegetables, rice, and tobacco (Satarug et al., 2010). Consequently, food consumption and cigarette smoking are the 2 major sources of Cd exposure in the general population (Li et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2017).

Long-term chronic Cd exposure in humans can lead to damage in various organs including kidney, liver, and bones (Rodriguez and Mandalunis, 2018; Torra et al., 1995) and several studies indicate that Cd is also a neurotoxicant. Cd is able to cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the brain, causing neurotoxicity by activating various signaling pathways involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal apoptosis (Chen et al., 2008; Wang and Du, 2013; Yuan et al., 2018).

Several epidemiology studies have suggested an association between Cd exposure and cognitive decline in humans (Ciesielski et al., 2012, 2013). However, these studies, although extremely interesting, provide only correlative evidence due to other potential confounding factors. A recent study in our laboratory showed a clear causal relationship between Cd exposure and cognitive deficits in male C57BL/6 mice (Wang et al., 2018). Building on these observations, we hypothesized that a GxE interaction between ApoE and Cd exposure may exacerbate cognitive impairment in the presence of ApoE4 allele compared with the ApoE3 allele.

In this study, we used humanized homozygous ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice to examine the effects of Cd exposure at the behavioral and cellular levels. The human ApoE3 or ApoE4 allele in these knock-in transgenic mice replaces the endogenous mouse ApoE gene and is expressed at physiological levels under the control of the endogenous mouse ApoE promoter. Our goal was to investigate whether a GxE interaction between ApoE4 and Cd exposure leads to accelerated cognitive deficiency and to begin elucidating the underlying mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Humanized ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice were provided by Dr. Nobuyo Maeda at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (Xu et al., 1996) and maintained in our laboratory. Mice were housed in standard conditions (12 h light/dark cycle) with food and water provided ad libitum. All animal care and treatments were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cd exposure

ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice were weaned at 28 days and littermates of the same sex were randomly separated into groups of 3–5 mice per cage. Starting at 8 weeks of age, the mice in the treatment group were switched from normal drinking water to drinking water with 0.6 mg/l CdCl2. These mice were exposed to the Cd drinking water for 14 weeks and then switched back to normal drinking water for the remainder of the study. Mice were not left on treatments until the end of the study because we wanted to determine if the effects of Cd were persistent after exposure to Cd was ceased. The mice in the control groups were given normal drinking water throughout the study. The drinking water with CdCl2 (Cat. 202908, MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, Missouri) was prepared from a stock solution and replaced every week. Body weight was recorded every 1–2 weeks throughout the study. We used 2 separate cohorts of mice in our study, one for behavioral experiments and one for cellular immunostaining experiments. The behavior cohort had n = 8–10 mice per genotype/treatment/sex, and the cellular cohort had n = 5 mice per genotype/treatment/sex. The preparation, use, and disposal of hazardous reagents were conducted according to the guidelines set forth by the Environmental Health and Safety Office at the University of Washington.

Open field test

The open-field test was conducted before and after the Cd exposure (at age of 5 weeks and 22 weeks) to assess the effects of Cd on locomotor activity and anxiety. Mice were placed into a 10 × 10 × 16 inches TruScan Photo Beam Tracking arena (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, Pennsylvania) with clear Plexiglas sidewalls and their movement was monitored with 2 sets of infrared beams spaced 0.6 inch apart, providing a spatial resolution of 0.3 inch. Each animal was allowed to freely explore the arena without prehabituation for 20 min, and the data were collected by TruScan 2.0 software (Coulbourn Instruments). The arena was cleaned with 5% acetic acid after each session. The total move distance, total move time, and average speed were used to assess the effects of Cd on locomotor activity. The time and distance spent in the margin, as well as margin/center distance and time ratios, were used to assess the effects of Cd on anxiety. The margin was defined as the area within 1.5 inches of the arena wall, whereas center was defined as the area more than 1.5 inches away from the arena wall.

Elevated plus maze test

The elevated plus maze test was conducted at the age of 69 weeks to investigate the effects of Cd on anxiety. The elevated plus maze apparatus (26 × 26 × 15.25 inches, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, California) consists of 2 open arms, 2 closed arms, and a center area. Each closed arm has a 7-inch wall on both sides, and the center area measures 2 × 2 inches. During the test, the maze was placed in the center of the behavior room, and each animal was placed into the center of the apparatus facing an open arm and allowed to freely explore the maze for 5 min. The apparatus was cleaned with 5% acetic acid after each session. The open and closed arm ends were defined as the distal one-third of the arms. Animal behavior was recorded by a video camera from above and ANYmaze software (San Diego Instruments) was used to analyze animal movement.

Novel object location test

We conducted 1-h novel object location (NOL) tests to assess the effects of Cd on hippocampus-dependent spatial working memory at various time points (6, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 25, 33 weeks). This test was performed as previously described with a few modifications (Pan et al., 2012). Each animal was placed into an open field arena (Coulbourn Instruments) with 2 identical objects placed in 2 different corners. During the training session, the mouse was allowed to freely explore the 2 objects for 5 min and then returned to its home cage. After 1 h, one object remained in its original corner and the other was moved to a new corner in the arena. The animal was then returned to the arena and allowed to explore the 2 objects for 5 min. The arena and the objects were cleaned with 5% acetic acid after each session. All training and test sessions were recorded by cameras and the time spent by each animal investigating each object was scored afterward. All scoring was done by an experimenter blinded to the animal treatment and genotype. The exploration behavior includes sniffing, biting, and licking of the objects. The cutoff criteria for NOL assays were a minimum of 1 s exploration time on each object. The cutoff time was chosen based on our previous studies in which we optimized the protocol for the assay. The discrimination index was calculated by dividing the differences in exploring time between old and novel locations by the total exploring time.

T-maze continuous alternation test

We conducted T-maze continuous alternation tests at the age of 23 and 48 weeks to assess spontaneous alternation by following a continuous alternation T-maze protocol with minor modifications (Spowart-Manning and van der Staay, 2004). We used a black plastic T-maze apparatus with 2-goal arms and 1 start arm (12.2 × 4.5 × 8.26 inches). During the experiment, it was placed on a platform (22.5 inches) in the center of a behavior room. The test started with a forced trial followed by 14 free-choice trials. To start, the animal was sequestered with a plastic guillotine door in the distal one-third of the start arm for 5 s. Then, the door was raised, but one of the goal arms was randomly blocked with the guillotine door and the mouse would be forced to enter the other goal arm. Once the animal returned to the start arm, it was sequestered in the start arm for 5 s before the start of the 14 free-choice trials. For each free-choice trial, no goal arm was blocked and the mouse was allowed to enter either of the goal arms; once it entered a goal arm, the other goal arm was immediately blocked with the guillotine door. When the animal eventually returned to the start arm, it was sequestered for 5 s whereas all of the goal arms were unblocked. This cycle was repeated for a total of 14 times. We allowed 30 min for each mouse to complete 14 free-choice trials. For the majority of the cohort, it took less than 10 min per mouse. The apparatus was cleaned with 5% acetic acid after each session. We defined arm entry as the animal’s whole body including tail tip entering the arm. The alternation percentage was calculated by dividing the number of times the animal entered alternating arms by 14 (free-choice trials). All tests were scored in session by an experimenter blinded to animal treatment and genotype.

5-bromo-2ʹ-deoxyuridine administration

The 5-bromo-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was purchased from MilliporeSigma (Cat. B9285, MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, Missouri) and aliquoted and stored as a 20 mg/ml stock in saline with 0.007% NaOH at −20°C. The mice in the cellular cohort were dosed with 100 mg/kg BrdU by intraperitoneal injection twice a day for 3 days 3 weeks prior to sacrifice at the end of the 14-week Cd exposure.

Blood and brain sample collection

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, and then blood was drawn from the heart and collected with blood collection tubes (Cat. 368381, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for trace element testing. Mice were euthanized by decapitation and brains were dissected out for further analysis. The cortex was removed from one brain hemisphere and freshly frozen for Cd analysis, whereas the other hemisphere was post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Cat. P6148, MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, Missouri) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) overnight. The fixed brain tissues were then incubated in 30% (wt/vol) sucrose (Cat. 8360-06, Avantor Performance Materials, Center Valley, Pennsylvania) in PBS solution at 4°C until tissues sank. Tissue samples were stored in O.C.T. Compound (Cat. 4583, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, California) at −80°C until sectioning.

Blood and cortex Cd analysis

All blood and cortex samples were collected from the cellular cohort (n = 5 per group) at sacrifice immediately after the cessation of Cd exposure. The Environmental Health Laboratory at the University of Washington measured blood and cortex Cd levels using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). All measurements were made using an Agilent 7900 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) which has a detection limit of 0.08 ng/ml.

Immunohistochemistry

Coronal brain sections (30-µm thick) were used for immunohistochemistry following a free-floating antibody staining protocol as described previously (Pan et al., 2012). The primary antibodies and dilutions used in these experiments were: rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:500, Bio-Rad Laboratories AbD Serotec, Raleigh, North Carolina), mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN (1:1000, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, Massachusetts) and goat polyclonal anti-DCX (1: 200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas). The Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies, including goat anti-rat, goat anti-mouse, and donkey anti-goat, as well as Hoechst 33342 (2.5 µg/ml) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California). All the primary and secondary antibodies were diluted into the appropriate blocking buffer (10% donkey or goat serum and 1% BSA).

Imaging and quantification of immunostained cells

Every eighth serial section was immunostained for each cellular marker or combination of markers. All images were captured with an Olympus Fluoview-1000 laser scanning confocal microscope under a 20× lens with a numerical aperture of 0.75. Optical Z-series stacks (1 µm per image) were collected and processed with the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland). The number of positively stained cells in the subgranular zone and granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus (DG) was quantified by an experimenter blinded to the treatment and genotype of each sample. This number was multiplied by 8 to estimate the total number of positively stained cells in the entire DG. Marker colocalization of double-positive cells was defined as overlapping fluorescent signal in a Z-series stack of confocal images.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 3.6.0). For blood/cortex Cd concentrations, the open field test, elevated plus maze test, T-maze test, and all immunohistochemical studies, 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to account for the main effect of genotype (ApoE3-KI vs ApoE4-KI), treatment (control vs Cd-treated), sex (females vs males), as well as interactions between 2 of these variables. When 2-way ANOVA showed significant results, pairwise post hoc tests were conducted with Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons (α = 0.05). Student’s 2-tailed t-test (α = 0.05) was used for within-genotype comparisons in each sex for the NOL data in Figure 5. Mixed-effects linear regression (α = 0.05) was used for longitudinal analysis of mouse body weight in Figure 2 and the discrimination index for within-genotype comparisons in each sex in NOL in Figure 6. Within-treatment comparisons for the discrimination index in Figure 7 was conducted by fitting the data to sigmoidal time-response curves and estimating t 1/2 values (R package “drc”). Pairwise comparisons of t 1/2 values were made using 2-tailed t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. All data are reported as means ± SEM; ns, not significant; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

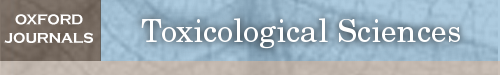

Figure 5.

The effects of Cd exposure on hippocampus-dependent short-term spatial memory in the NOL test (n = 8–10/group). The time each mouse spent exploring the objects in the old location (location A) and the new location (location C) was quantified and compared. A, C, E, G, I, ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI male mice were unable to distinguish between the old and new locations starting at 9 and 3 weeks, respectively. B, D, F, H, J, ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI female mice no longer distinguished between the old and new locations starting at 11 and 9 weeks, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed t-test: ns, not significant, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001.

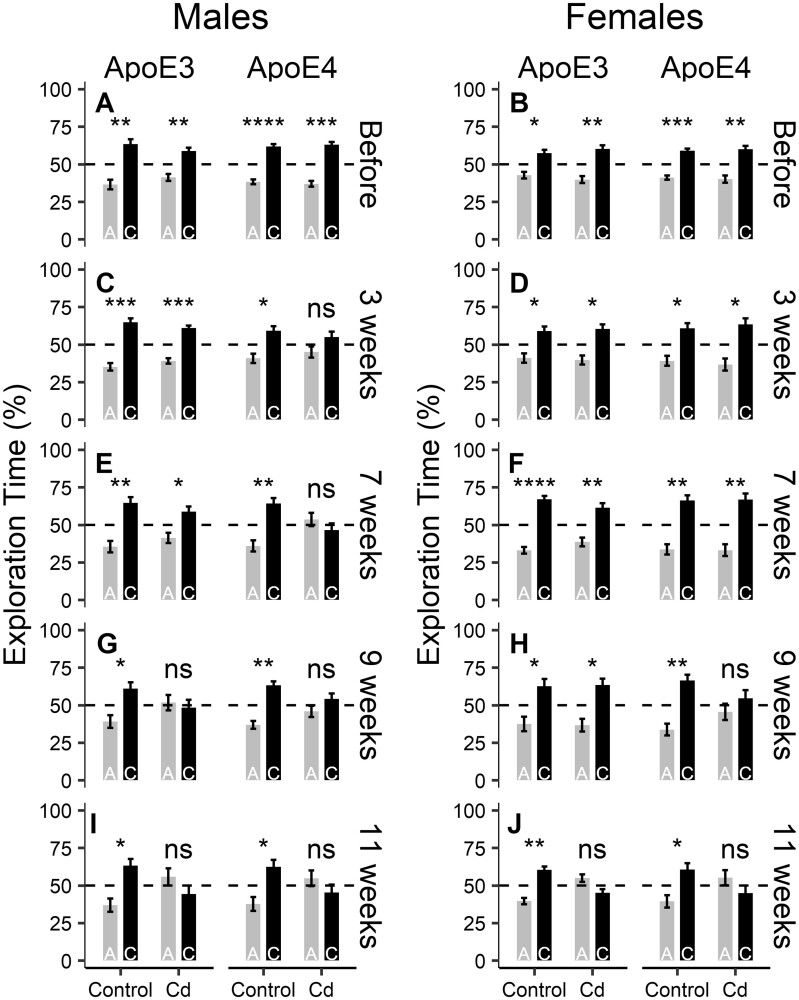

Figure 2.

Body weights of ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 8–10/group) during and after the period of Cd exposure. A, Schematic illustration of the experimental design and timeline for the behavior cohort. Asterisks indicate time points of NOL assays. B, Body weight of each mouse was measured every 1–2 weeks during and after the Cd exposure. The Cd-treated mice did not exhibit any weight loss compared with their respective control mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. NOL, novel object location.

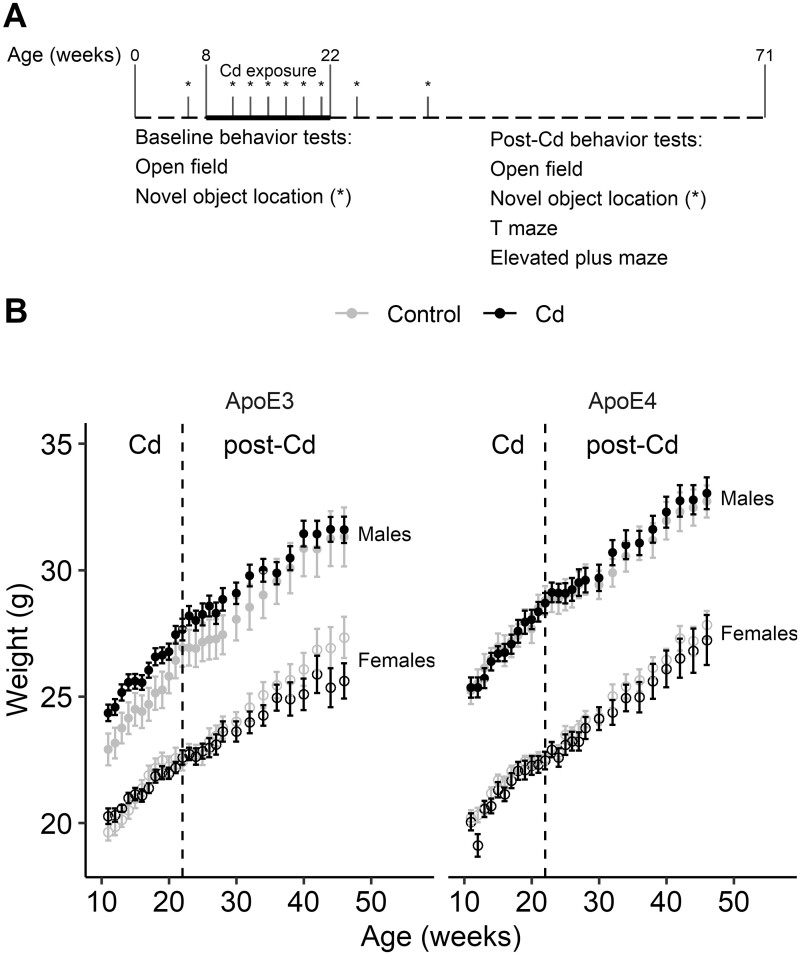

Figure 6.

Changes of the discrimination indices of the ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 8–10/group) in the NOL test during and after Cd exposure. The discrimination index was calculated by dividing the difference in exploration time between the novel location (location C) and old location (location A) by the total exploration time. There was a significant difference between the Cd-treated group and the control group for ApoE3-KI males (A), ApoE4-KI males (B), ApoE3-KI females (C), and ApoE4-KI females (D). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the discrimination indices of the Cd-treated group and the control group for each time point. Tukey’s post hoc tests: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of the discrimination indices of the Cd-treated groups (n = 8–10/group) in the NOL test fitted with sigmoidal time-response curves. Time-response curves were fitted to compare ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI males (A), ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI females (B), ApoE3-KI males and females (C), and ApoE4-KI males and females (D). (E) Pairwise comparisons of the t 1/2 values estimated by curve fitting in (A–D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed t-test: ns, not significant, *p < .05, **p < .01.

RESULTS

Cd Concentrations in Mouse Blood and Cortex

It has been reported that exposure to 10 mg/l CdCl2 via drinking water leads to adverse neurological effects in mice (Chen et al., 2013; Honda et al., 2013). Our recent study using C57BL/6 mice demonstrated that exposure to 3 mg/l CdCl2 impairs hippocampus-dependent memory and short-term olfactory memory (Wang et al., 2018). In order to assess Cd neurotoxicity at blood Cd levels comparable to that found in the U.S. general population and to mimic environmental exposure by ingestion, we exposed 8-week-old ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice to 0.6 mg/l CdCl2 via drinking water for 14 weeks. Mice were sacrificed at the end of the 14-week exposure; blood and brain cortex samples were collected to test for Cd concentrations.

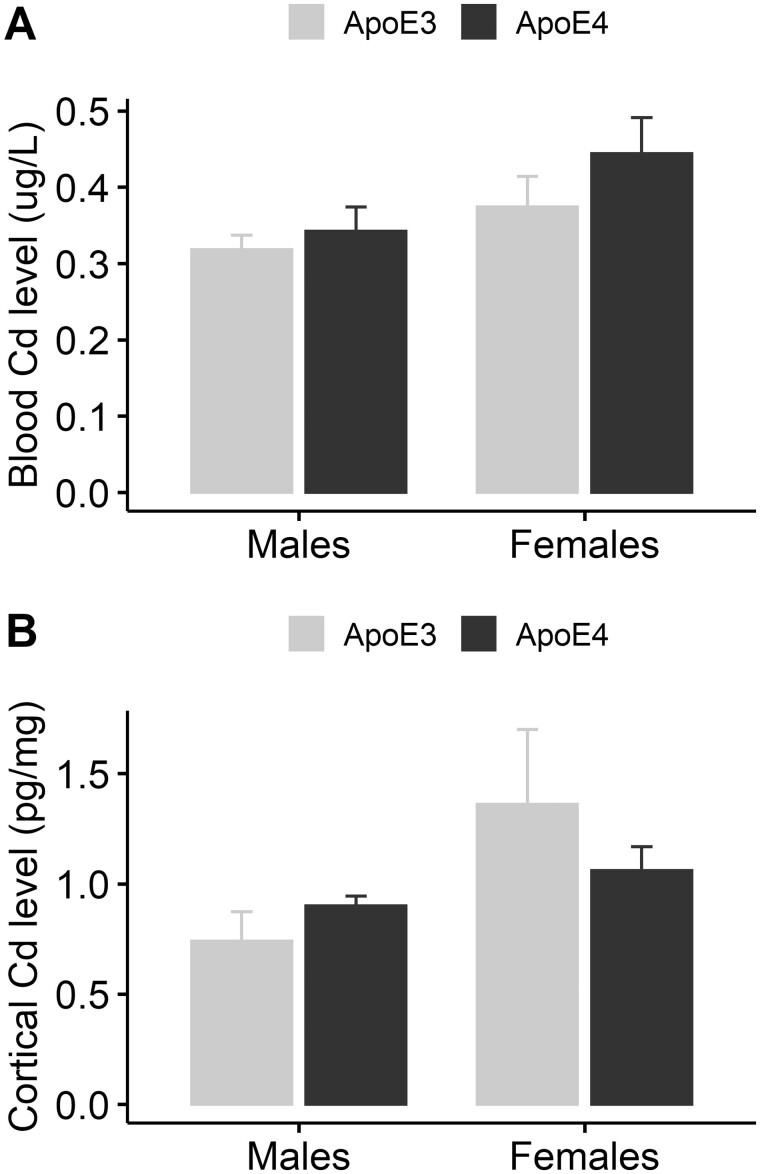

All Cd-treated groups showed blood Cd concentrations of about 0.3–0.4 µg/l and no significant difference was detected between ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI groups (Figure 1A, 2-way ANOVA: Sex, F (1, 16) = 4.80, p = .044, Genotype, F (1, 16) = 1.70, p = .21, Sex × Genotype, F (1, 16) = 0.41, p = .53, Tukey’s: ApoE3 vs ApoE4, Females, p = .19, Males, p = .64). All control groups which were given regular drinking water did not have detectable Cd concentrations in the blood (data not shown). The blood Cd levels detected in Cd-treated mice were within the blood Cd levels in human populations who are nonsmokers (men: 0.21–0.40 µg/l; women: 0.26–0.42 µg/l, 1999–2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). We also measured Cd concentrations in the cerebral cortex. We detected 0.7–1.3 pg/mg Cd in all groups of Cd-treated mice but not in the control groups, suggesting that adult-only Cd exposure was sufficient to cause Cd accumulation in the brain (Figure 1B, 2-way ANOVA: Sex, F (1, 16) = 4.14, p = .059, Genotype, F (1, 16) = 0.13, p = .72, Sex × Genotype, F (1, 16) = 1.44, p = .25). There was no significant difference in cortical Cd levels between ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice.

Figure 1.

Cd concentrations in mouse blood and cortex after 14-week exposure. 8-week-old ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 5/group) were exposed to 0.6 mg/l CdCl2 for 14 weeks. Samples were collected at sacrifice and measured using ICP-MS. A, Blood Cd levels. B, Cortex Cd levels. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Mouse Body Weight, Locomotor Activity, and Anxiety

To assess Cd neurotoxicity in memory, we exposed a separate cohort of 8-week-old ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice to 0.6 mg/l CdCl2 through drinking water for 14 weeks and conducted a series of behavioral experiments before, during, and after the exposure (Figure 2A). We did not observe any significant difference between the body weights of any Cd-treated mice compared with their respective controls during or after Cd exposure (Figure 2B, mixed-effects linear regression: ApoE3-KI males, F (1, 18) = 4.28, p = .053, ApoE3-KI females, F (1, 15) = 2.57, p = .13, ApoE4-KI males, F (1, 16) = 0.20, p = .66, ApoE4-KI females, F (1, 18) = 0.18, p = .68).

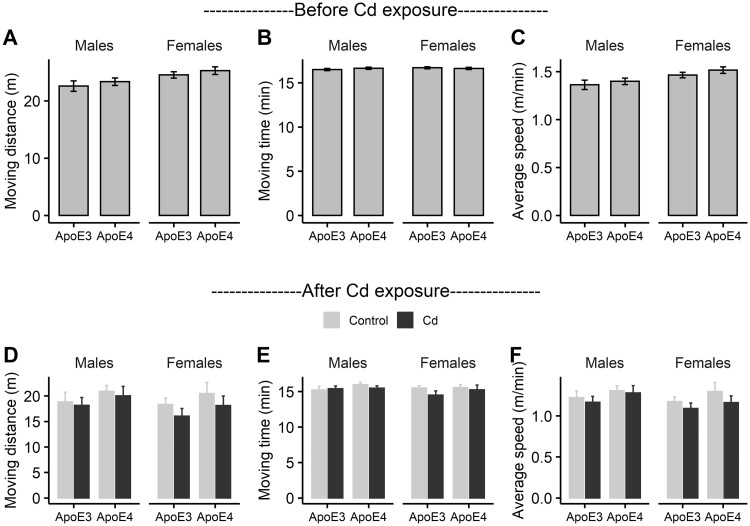

To determine if Cd exposure affects locomotor activity, we performed an open field test for all the animals before and after the Cd exposure. In the pre-exposure test, we did not observe any significant difference in animals’ moving distance, time, or average speed between ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI groups for either sex (Figs. 3A–C, 2-way ANOVA: no significant main effects or interaction). The cohort was then randomly split into control and Cd-treated groups with no significant differences between the assigned groups for each genotype and sex. After Cd exposure, we did not observe any significant effect of Cd on locomotor activity in any groups of mice (Figs. 3D–F, 2-way ANOVA: no significant main effects or interaction), suggesting that Cd treatment does not impair locomotor activity.

Figure 3.

Locomotor activity of ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 8–10/group) measured in the open field test. There were no significant differences between ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI in moving distance (A), moving time (B), or average speed (C) before Cd exposure. Cd exposure did not result in any significant difference between Cd-treated mice and control mice in moving distance (D), moving time (E) or average speed (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

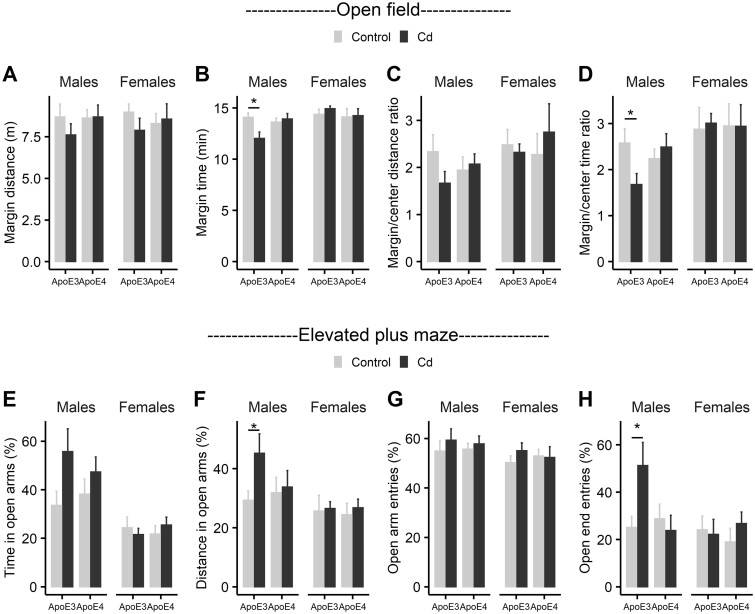

To determine if Cd exposure caused anxiety, we further analyzed data collected in the open field test to determine if Cd exposure leads to increased margin move distance, margin move time, margin/center distance ratio, or margin/center time ratio as signs of anxiety. None of these metrics was affected by Cd treatment in females (Figs. 4A–D, 2-way ANOVA: no significant main effects or interaction). Cd-treated ApoE3-KI male mice spent less time in the margin compared with ApoE3-KI control males (Figure 4B, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 34) = 8.29, p = .0069, Genotype, F (1, 34) = 0.38, p = .54, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 34) = 5.11, p = .030, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .0069, ApoE4, p = .70; Figure 4D, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 34) = 5.86, p = .021, Genotype, F (1, 34) = 0.78, p = .38, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 34) = 4.53, p = .041, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .021, ApoE4, p = .53), indicating a potential anxiolytic effect. To further assess the effect of Cd exposure on anxiety, we performed an elevated plus maze test after Cd exposure. Rodents naturally prefer dark sheltered spaces, and the elevated plus maze test is widely used to assess anxiogenic (increased tendency to stay in the closed arms) or anxiolytic (increased tendency to explore open arms) behaviors (Walf and Frye, 2007). We investigated 4 metrics: percentages of time as well as distance in open arms, percentage of open arm entries, and percentage of open end entries. We did not observe any significant effect of Cd exposure on all females or ApoE4-KI male (Figs. 4E–H, 2-way ANOVA: no significant main effects or interaction). Cd-treated ApoE3-KI male mice traveled more distance in the open arms and exhibited more open-end entries compared with the control ApoE3-KI males (Figure 4F, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 30) = 5.18, p = .030, Genotype, F (1, 30) = 0.11, p = 0.74, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 30) = 1.76, p = .19, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .030, ApoE4, p = .81; Figure 4H, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 30) = 7.58, p = .0099, Genotype, F (1, 30) = 0.13, p = .72, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 30) = 4.74, p = .038, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .0099, ApoE4, p = .64). Taken together, these data suggest that 14-week exposure to 0.6 mg/l Cd did not affect locomotor activity or cause anxiety in ApoE3-KI or ApoE4-KI mice. If anything, Cd treatment may be anxiolytic in ApoE3-KI males.

Figure 4.

Anxiety of ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 8–10/group) measured in the open field test and the elevated plus maze test after Cd exposure. In the open field test, Cd-treated females did not show any difference compared with controls in margin distance (A), margin time (B), margin/center distance ratio (C), or margin/center time ratio (D). Cd-treated ApoE3-KI males showed a decrease in margin time (B) and margin/center time ratio (D). In the elevated plus maze test, Cd-treated females did not show any difference compared with controls in time in open arms (E), distance in open arms (F), open arm entries (G), or open-end entries (H). Cd-treated ApoE3-KI males showed an increase in distance in open arms (F) and open-end entries (H). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*p < .05).

The NOL Test

To assess if Cd exposure has any effect on hippocampus-dependent spatial working memory, we conducted a 1-h NOL test before, during, and after Cd exposure. Importantly, in all NOL tests we performed, none of the mice exhibited a significant difference in time spent on exploring each object/location during the training session, indicating no preference for either location or object (data not shown).

Before Cd exposure, in the test session of NOL, all groups of ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice spent significantly more time exploring the object in the novel location (location C) than exploring the object in the original location (location A), indicating that they were able to remember the original object location (Figs. 5A and 5B). Upon Cd treatment, ApoE4-KI male mice started to show a memory deficit after 3 weeks of Cd exposure, indicated by a failure to distinguish between the old and new locations (Figure 5C). This deficit persisted throughout the remaining duration of the experiment (Figs. 5E, 5G, and 5I). Cd-treated ApoE3-KI males did not develop this memory deficit until after 9 weeks of Cd exposure (Figure 5G). For female mice, ApoE4-KI and ApoE3-KI animals did not show memory deficits until 9 or 11 weeks of Cd treatment, respectively (Figs. 5D, 5F, 5H, and 5J). These data showed that both male and female ApoE4-KI mice are more susceptible to Cd exposure than their ApoE3-KI counterparts in this test, suggesting a GxE interaction between ApoE4 genotype and Cd treatment.

To further analyze the GxE interaction statistically, we calculated the discrimination index for each mouse in each NOL test (Figure 6). The use of the discrimination index is to normalize the differences of time spent by each mouse on exploring objects in the novel and old locations. There was an effect of Cd exposure on the discrimination index in all Cd-treated mice (mixed-effects linear regression, Time × Treatment: ApoE3-KI males, F (8, 127) = 2.19, p = .032, ApoE4-KI males, F (8, 102) = 2.72, p = .0094, ApoE3-KI females, F (7, 90) = 3.48, p = .0024, ApoE4-KI females, F (7, 88) = 3.87, p = .0010).

The Cd-treated ApoE3-KI or ApoE4-KI males started to show a significantly lower discrimination index than their control groups at 9 or 7 weeks into Cd exposure, respectively (Figs. 6A and 6B), whereas ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI females had a significantly lower discrimination index starting at 11 and 9 weeks, respectively, after Cd exposure (Figs. 6C and 6D). Once occurred, the deficits persisted 3 months post Cd exposure in all Cd-treated animals.

To quantify the differences between ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice in response to Cd exposure over time, we fitted the data of Cd-treated groups to sigmoidal time-response curves (Figs. 7A–D). This allowed us to estimate an important parameter to compare the effect of Cd exposure on ApoE3-KI versus ApoE4-KI mice: the time latency parameter t 1/2, reflecting the time to reach 50% of the maximal memory impairment (Figure 7E). Notably, the mean t 1/2 values of all Cd-treated mice were comparable to their respective onset time of memory deficits we observed in Figure 5, meaning that a 50% decrease in the discrimination index is a valid estimate for the onset time. Interestingly, for Cd-treated mice, the t 1/2 of ApoE4-KI was smaller than that of ApoE3-KI within the same sex; this genotype difference was statistically significant in males (p = .0064; Figure 7E). Furthermore, t 1/2 was smaller in males than in females within the same genotype; this sex difference was statistically significant in both ApoE3-KI mice (p = .049) and ApoE4-KI mice (p = .0030). These data suggest that ApoE4-KI males were most susceptible to Cd impairment of memory in the NOL test whereas ApoE3-KI females were the least sensitive.

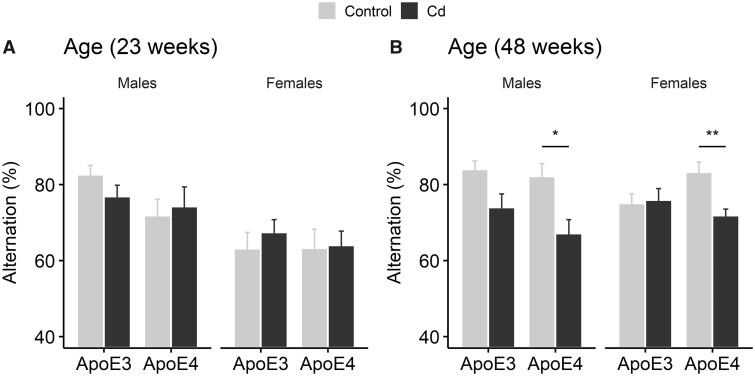

The GxE in the T-Maze Test

In the T-maze settings, mice tend to spontaneously alternate the arms they enter in a period of time, a behavior that is partially due to hippocampus-dependent spatial working memory (Gerlai, 1998). We first assessed spontaneous alternation behavior of the cohort 1 week after the end of Cd exposure when mice were 23 weeks old; by this time all Cd-treated mice had developed deficits in the NOL test. We did not observe any differences in alternation between Cd-treated groups and their respective control groups (Figure 8A, 2-way ANOVA: Males, Treatment, F (1, 34) = 0.98, p = .33, Genotype, F (1, 34) = 3.28, p = .079, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 34) = 0.94, p = .34; Females, Treatment, F (1, 33) = 0.38, p = .54, Genotype, F (1, 33) = 0.00059, p = .98, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 33) = 0.14, p = .71). However, about 6.5 months after the end of Cd exposure when the mice were at a much older age (about 11-months old), both Cd-treated ApoE4-KI males and females exhibited a significant decrease in spontaneous alternation compared with their respective controls (Figure 8B, 2-way ANOVA: Males, Treatment, F (1, 34) = 11.54, p = .0017, Genotype, F (1, 34) = 1.42, p = .24, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 34) = 0.48, p = .49, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .055, ApoE4, p = .0075; Females, Treatment, F (1, 32) = 4.35, p = .045, Genotype, F (1, 32) = 0.76, p = .39, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 32) = 4.54, p = .041, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .84, ApoE4, p = .0056). For Cd-treated ApoE3-KI mice, there was a small but statistically insignificant decrease in spontaneous alternation in males whereas no change was observed in females. Thus, Cd-induced deficits in spontaneous alternation which occurred later in life than deficits in the NOL test. These data also support the notion that there is a GxE interaction between ApoE4 genotype and Cd exposure in cognition.

Figure 8.

Spontaneous alternation in ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 8–10/group) in the T-maze tests after Cd exposure. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (A) There was no significant difference between the Cd-treated group and the control group of either sex at 23 weeks of age. (B) Spontaneous alternation was decreased in both Cd-treated ApoE4-KI females and males, but not in Cd-treated ApoE3-KI mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < .05, **p < .01.

The GxE in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis

Our behavior experiments demonstrated that Cd exposure differentially affected ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice in hippocampus-dependent spatial working memory, suggesting that the hippocampus may play an important role in mediating the GxE interaction. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is a process in which adult neural stem cells in the DG of the hippocampus generate adult-born neurons, which are crucial for hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (Deng et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014).

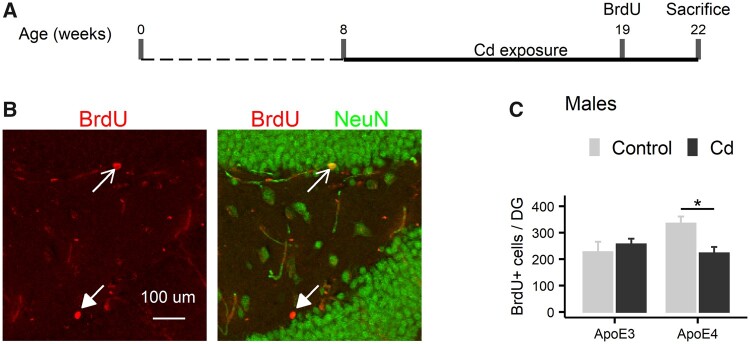

To elucidate mechanisms underlying the GxE effect of Cd exposure on cognitive impairment in male ApoE4-KI and ApoE3-KI mice, we investigated whether there is a GxE interaction between ApoE4 and Cd exposure on adult neurogenesis. Separate cohorts of male ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice were used to address this issue. We injected BrdU 11 weeks after the start of Cd exposure and animals were sacrificed 3 weeks later at the end of the Cd exposure (Figure 9A). Anti-BrdU immunostaining was used to identify 3-week-old, adult-born cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Figure 9B). There was a significant decrease in the total number of BrdU+ cells in the DG of ApoE4-KI, but not in the ApoE3-KI mice (Figure 9C, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 16) = 2.14, p = .16, Genotype, F (1, 16) = 1.67, p = .22, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 16) = 6.23, p = .024, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .47, ApoE4, p = .013).

Figure 9.

The effect of Cd exposure on the total numbers of adult-born neurons in ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI male mice (n = 5/group). (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design and timeline for the cohort of the immunostaining study. BrdU was administered 3 weeks prior to sacrifice. (B) Representative images of BrdU and NeuN immunostaining in the DG of control and Cd-treated ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI male mice. The open arrow indicates a BrdU+ NeuN+ cell and the closed arrow indicates a BrdU+ cell. (C) Cd exposure caused a decrease in the total numbers of BrdU+ cells in the DG of ApoE4-KI males but not in ApoE3-KI males. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*p < .05). DG, dentate gyrus.

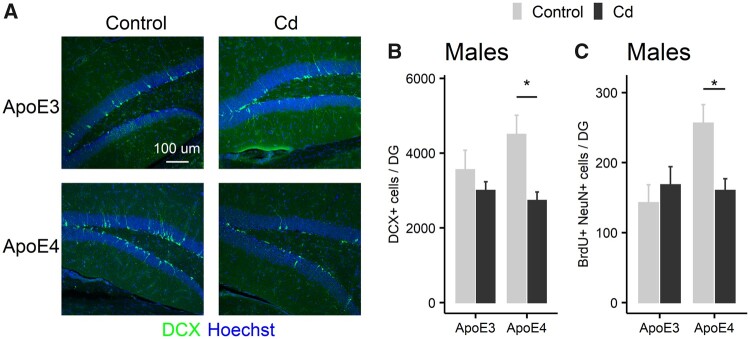

To examine the effect of Cd on neuronal differentiation during adult hippocampal neurogenesis, we performed immunostaining using DCX (Figure 10A) and NeuN (Figure 9B) as markers of immature and mature neurons, respectively. There was a significant decrease in the total number of DCX+ cells in the DG of ApoE4-KI but not ApoE3-KI mice (Figure 10B, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 16) = 8.36, p = .011, Genotype, F (1, 16) = 0.71, p = .41, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 16) = 2.27, p = .15, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .34, ApoE4, p = .0067). Furthermore, Cd exposure significantly reduced the number of adult-born mature neurons, identified by double-positive staining for BrdU and NeuN, in the DG of ApoE4-KI but not ApoE3-KI mice (Figure 10C, 2-way ANOVA: Treatment, F (1, 16) = 2.10, p = .17, Genotype, F (1, 16) = 4.74, p = .045, Treatment × Genotype, F (1, 16) = 6.29, p = .023, Tukey’s: Control vs Cd, ApoE3, p = .46, ApoE4, p = .013). These data suggest that Cd exposure inhibits hippocampal adult neurogenesis in ApoE4-KI males.

Figure 10.

The effect of Cd exposure on adult-born neuron differentiation in the DG of ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice (n = 5/group). A, Representative images of DCX immunostaining in the DG of control and Cd-treated ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI male mice. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. B, Cd exposure caused a decrease in the total number of DCX+ cells in ApoE4-KI males. (C) Cd exposure caused a decrease in the total numbers of BrdU+ NeuN+ cells in the DG of ApoE4-KI males, but not in ApoE3-KI males (*p < .05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. DG, dentate gyrus.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have identified cerebrovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking as some of the AD risk factors (Reitz et al., 2011). However, it is unclear whether and how environmental exposures and especially interactions between gene and environmental exposures contribute to AD pathogenesis. In this study, we present evidence that an interaction between ApoE4 and Cd exposure accelerates the onset of cognitive decline at blood levels commonly found in the general U.S. population. In young animals, there was a sex difference with the GxE interaction most prominent in ApoE4-KI males.

To investigate the GxE interaction between ApoE4 and environmental exposure, animals were exposed to 0.6 mg/l Cd through drinking water to model oral exposure. Previously, we demonstrated that Cd exposure at 3 mg/l in drinking water induces persistent impairments of several forms of hippocampus-dependent spatial working memory in C57BL/6 mice (Wang et al., 2018). We reported that after 13 weeks of exposure, the blood Cd level was 2.25 ± 0.48 µg/l (Wang et al., 2018). Although this is lower than the standard trigger level of Cd (5 µg/l) for workers to be removed from the workplace in Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulation, this level is still higher than the blood Cd levels of the general U.S. population including smokers who have higher blood Cd levels than nonsmokers (male smokers: 0.58–0.94 µg/l; female smokers: 0.69–1.17 µg/l; Adams and Newcomb, 2014). In the current study, we aim to develop an exposure protocol that would yield blood Cd levels comparable to those found in the general U.S. population. We report here that 14 weeks of exposure to 0.6 mg/l Cd resulted in peak blood Cd concentrations at 0.3–0.4 µg/l, within the range of Cd blood levels in nonsmokers (men: 0.21–0.40 µg/l; women: 0.26–0.42 µg/l, 1999–2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

We performed the NOL before, during, and after Cd exposure to probe the onset and persistence of memory impairment. Cd treatment impaired the short-term spatial working memory in all animals. The impairment appeared as early as 3 weeks of exposure and when animals were still as young as 3 months old. It was also long-lasting, persisting months after Cd exposure ended. Furthermore, we observed an earlier onset of spatial working memory deficits in Cd-treated ApoE4-KI mice compared with ApoE3-KI mice. However, when the t 1/2 for memory impairment was compared, this difference was statistically significant only between males. When we compared the 2 sexes within the same genotype, males had an earlier onset than females for both ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice. These data provide direct evidence that a GxE between ApoE4 and Cd exposure accelerates the impairment of hippocampus-dependent memory, at least in males.

Alternation behavior in T-maze is sensitive to hippocampal lesions, but is not entirely hippocampus-dependent (Dudchenko, 2004; Gerlai, 1998). A test of spontaneous alternation is frequently used in other AD animal models. We observed that in the T-maze test Cd exposure decreased spontaneous alternation in ApoE4-KI mice about 6.5 months after the cessation of exposure, when the mice were at an older age (48 weeks/11 months). Interestingly, we did not observe such an effect soon after exposure ended when the mice were younger (23 weeks). These data suggest that the GxE between ApoE4 and subchronic Cd exposure in young adult causes long-lasting and long-term changes in the brain. Although some forms of cognitive impairment, such as memory for NOL, occurred sooner and were long-lasting, other forms of cognition such as that detected by the alternative behavior in the T-maze, were aging-dependent and did not manifest until much later, even long after exposure has ended. This result is consistent with age-associated memory impairment as a part of the aging process observed in elderly people (Sharma et al., 2010). It is possible that the GxE between ApoE4 and Cd exposure may accelerate cognitive decline during aging. The delayed onset of cognitive deficit in the T-maze also underscores the importance of long-term follow-ups when studies are designed to investigate the effect of environmental exposure on health.

What are the potential mechanisms underlying the interaction between ApoE4 and Cd on accelerated memory decline? It is possible that ApoE4 may cause leakage on the blood-brain barrier (Bell et al., 2012) and lead to higher degree of Cd accumulation in the ApoE4 brain. However, there was no statistic significant difference between ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice in their blood or brain Cd concentrations at the end of the 14-week exposure. Future studies should examine if the kinetics of Cd absorption into the blood and distribution into the brain is faster in ApoE4 than in ApoE3 mice.

Another possible mechanism is that there might be a combinatorial adverse effect of ApoE4 and Cd on adult neurogenesis. Neural stem cells in the adult brain proliferate and differentiate into neurons that functionally integrate into the neuron network, serving critical functions in learning and memory formation (Deng et al., 2010). This process does not affect locomotion but its role in anxiety-like behavior is still controversial (Snyder et al., 2011; Zou et al., 2015). Adult neurogenesis is vulnerable to environmental stimuli, including neurotoxicants (Lledo et al., 2006). However, little is known about the effects of GxE on adult neurogenesis. ApoE is expressed in adult hippocampal neural stem cells (Yang et al., 2011). Adult neurogenesis is impaired in ApoE4 mice compared with ApoE3 mice (Tensaouti et al., 2018). We observed a significant reduction in the number of total surviving adult-born cells (3-week-old BrdU+), adult-born immature neurons (DCX+ cells), and mature neurons (BrdU+ NeuN+ cells) in Cd-treated ApoE4-KI but not in ApoE3-KI males. These cellular changes are consistent with our behavioral findings that ApoE4-KI males are more vulnerable to Cd-induced cognitive impairment than ApoE3-KI males. Thus, inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may be a potential mechanism underlying the GxE effect between ApoE4 and Cd exposure on cognitive impairment.

We previously reported that exposure to lead (Pb), another neurotoxic heavy metal, caused deficits in contextual fear memory and an earlier onset of spatial working memory deficits in the NOL test in ApoE4-KI mice compared with ApoE3-KI mice (Engstrom et al., 2017). Furthermore, there was a GxE between ApoE4 and Pb exposure on impairment of adult hippocampal neurogenesis, especially neuronal differentiation. Together with data presented in this study, our results provide strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that a GxE interaction between ApoE4 and exposure to environmental toxicants including heavy metals such as Pb and Cd may lead to more severe or accelerated cognitive decline and potentially contribute to AD. Furthermore, impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis may be a common mechanism underlying this GxE.

Little is known about the difference between the effects of GxE on males and females. In this study, we observed a sex difference in response to the GxE effect. In the NOL test, males were more vulnerable than females and there was a significant GxE effect between ApoE4 and Cd in males only. Although there was an effect of GxE between ApoE4 and Cd in both sexes in the T-maze test, the memory deficits required a much longer time to develop than that in the NOL test, indicating that the effect of GxE in the T-maze may become more evident when the memory formation is more vulnerable during aging. One possibility is that female mice become more susceptible to the effect of GxE when the levels of estrogens are decreased during aging. In humans, estrogens serve a neuroprotective role which coordinates multiple signaling pathways to protect neurons from neurodegenerative diseases (Arevalo et al., 2015). Before menopause, females are less susceptible to posttraumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases, likely due to the neuroprotective effects of estrogen (Dye et al., 2012; Roof and Hall, 2000). Although rodents do not have a human-like menopause, they undergo reproductive senescence and cessation of reproductive cycles during aging. Our observation that the GxE effect between ApoE4 and Cd is significant in males but not in females when animals are young is consistent with the estrogen neuroprotection theory.

The sex difference we found here may seem contradictory to that we previously reported for ApoE4 and Pb exposure (Engstrom et al., 2017). Although the current study showed a significant GxE between ApoE4 and Cd exposure in males, females were more susceptible to the GxE between ApoE4 and Pb exposure (Engstrom et al., 2017). This difference may be due to the differences in the dose of exposure and/or in the brain accumulation of Cd versus Pb. In the present study, the peak blood Cd level after exposure was very low and the same as the blood Cd concentration in the general human population. Moreover, there were no differences in blood or brain Cd concentrations among different genotypes or sexes. However, the peak Pb concentration in the blood in our previous study was closer to occupational exposure levels but higher than that found in the general U.S. population. Furthermore, Pb-exposed female ApoE4-KI mice had the highest Pb deposition in the brains among all ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI mice, which could explain why the female ApoE4 mice were most sensitive to lead impairment of cognition.

In summary, we provide direct evidence that subchronic Cd exposure at a blood level relevant to that found in the general U.S. population leads to cognitive impairment and that mice with ApoE4-KI genotype are more susceptible to the adverse effects of Cd exposure than ApoE3-KI, suggesting a GxE interaction between ApoE4 and Cd exposure. Furthermore, there is a sex difference in this GxE effect; males are more vulnerable than females when animals are young. Finally, inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may be an underlying mechanism for this GxE interaction in males.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Nobuyo Maeda from University of North Carolina for providing ApoE3-KI and ApoE4-KI transgenic mice. We thank the Environmental Health Laboratory at the University of Washington for providing ICP-MS services to measure blood and brain Cd. We thank members of the Xia laboratory for discussions of experimental design and data analysis and critically reading the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Environmental Pathology/Toxicology training (grant T32 ES007032-37 to L.Z.) and NIH (R01 ES 026591 to Z.X.).

REFERENCES

- Adams S. V., Newcomb P. A. (2014). Cadmium blood and urine concentrations as measures of exposure: NHANES 1999–2010. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 24, 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo M. A., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L. M. (2015). The neuroprotective actions of oestradiol and oestrogen receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Winkler E. A., Singh I., Sagare A. P., Deane R., Wu Z., Holtzman D. M., Betsholtz C., Armulik A., Sallstrom J., et al. (2012). Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 485, 512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu G. (2009). Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: Pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Fourth Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- Chen L., Liu L., Huang S. (2008). Cadmium activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway via induction of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of protein phosphatases 2A and 5. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Ren Q., Zhang J., Ye Y., Zhang Z., Xu Y., Guo M., Ji H., Xu C., Gu C., et al. (2013). N-acetyl-L-cysteine protects against cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting ROS-dependent activation of Akt/mTOR pathway in mouse brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 40, 759–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski T., Bellinger D. C., Schwartz J., Hauser R., Wright R. O. (2013). Associations between cadmium exposure and neurocognitive test scores in a cross-sectional study of US adults. Environ. Health 12, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski T., Weuve J., Bellinger D. C., Schwartz J., Lanphear B., Wright R. O. (2012). Cadmium exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in U.S. children. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 758–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Aimone J. B., Gage F. H. (2010). New neurons and new memories: How does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudchenko P. A. (2004). An overview of the tasks used to test working memory in rodents. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye R. V., Miller K. J., Singer E. J., Levine A. J. (2012). Hormone replacement therapy and risk for neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 258454.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom A. K., Snyder J. M., Maeda N., Xia Z. (2017). Gene-environment interaction between lead and Apolipoprotein E4 causes cognitive behavior deficits in mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlai R. (1998). A new continuous alternation task in T-maze detects hippocampal dysfunction in mice. A strain comparison and lesion study. Behav. Brain. Res. 95, 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda A., Watanabe C., Yoshida M., Nagase H., Satoh M. (2013). Microarray analysis of neonatal brain exposed to cadmium during gestation and lactation. J. Toxicol. Sci. 38, 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Chang Q., Yuan X., Li J., Ayoko G. A., Frost R. L., Chen H., Zhang X., Song Y., Song W. (2017). Cadmium transfer from contaminated soils to the human body through rice consumption in southern Jiangsu Province, China. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 19, 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.-C., Liu C.-C., Kanekiyo T., Xu H., Bu G. (2013). Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo P. M., Alonso M., Grubb M. S. (2006). Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. W., Chan G. C. K., Kuo C. T., Storm D. R., Xia Z. (2012). Inhibition of adult neurogenesis by inducible and targeted deletion of ERK5 mitogen-activated protein kinase specifically in adult neurogenic regions impairs contextual fear extinction and remote fear memory. J. Neurosci. 32, 6444–6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaceri I., Nacmias B., Sorbi S. (2013). Genetics of familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed) 5, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C., Brayne C., Mayeux R. (2011). Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 7, 137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter P., Faroon O., Pappas R. S. (2017). Cadmium and cadmium/zinc ratios and tobacco-related morbidities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J., Mandalunis P. M. (2018). A review of metal exposure and its effects on bone health. J. Toxicol. 2018, 4854152.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof R. L., Hall E. D. (2000). Gender differences in acute CNS trauma and stroke: Neuroprotective effects of estrogen and progesterone. J. Neurotrauma 17, 367–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satarug S., Garrett S. H., Sens M. A., Sens D. A. (2010). Cadmium, environmental exposure, and health outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Rakoczy S., Brown-Borg H. (2010). Assessment of spatial memory in mice. Life Sci. 87, 521–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. S., Soumier A., Brewer M., Pickel J., Cameron H. A. (2011). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature 476, 458–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spowart-Manning L., van der Staay F. J. (2004). The T-maze continuous alternation task for assessing the effects of putative cognition enhancers in the mouse. Behav. Brain Res. 151, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tensaouti Y., Stephanz E. P., Yu T. S., Kernie S. G. (2018). ApoE regulates the development of adult newborn hippocampal neurons. eNeuro 5, pii: ENEURO.0155-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torra M., To-Figueras J., Rodamilans M., Brunet M., Corbella J. (1995). Cadmium and zinc relationships in the liver and kidney of humans exposed to environmental cadmium. Sci. Total Environ. 170, 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf A. A., Frye C. A. (2007). The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2, 322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Du Y. (2013). Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2013, 898034.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang L., Abel G. M., Storm D. R., Xia Z. (2018). Cadmium exposure impairs cognition and olfactory memory in male C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol. Sci. 161, 87–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Pan Y. W., Zou J., Li T., Abel G. M., Palmiter R. D., Storm D. R., Xia Z. (2014). Genetic activation of ERK5 MAP kinase enhances adult neurogenesis and extends hippocampus-dependent long-term memory. J. Neurosci. 34, 2130–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.-T., Schmechel D., Rothrock-Christian T., Burkhart D. S., Qiu H.-L., Popko B., Sullivan P., Maeda N., Saunders A. M., Roses A. D., et al. (1996). Human apolipoprotein E2, E3, and E4 isoform-specific transgenic mice: Human-like pattern of glial and neuronal immunoreactivity in central nervous system not observed in wild-type mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 3, 229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. P., Gilley J. A., Zhang G., Kernie S. G. (2011). ApoE is required for maintenance of the dentate gyrus neural progenitor pool. Development 138, 4351–4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Zhang Y., Zhao S., Chen J., Yang J., Wang T., Zou H., Wang Y., Gu J., Liu X., et al. (2018). Cadmium-induced apoptosis in neuronal cells is mediated by Fas/FasL-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathway. Sci. Rep. 8, 8837.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Wang W., Pan Y. W., Abel G. M., Storm D. R., Xia Z. (2015). Conditional inhibition of adult neurogenesis by inducible and targeted deletion of ERK5 MAP kinase is not associated with anxiety/depression-like behaviors. eNeuro. 2, 0014-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]