Abstract

PPM1D/Wip1 is a negative regulator of the tumor suppressor p53 and is overexpressed in several human solid tumors. Recent reports associate gain-of-function mutations of PPM1D in immune cells with worse outcomes for several human cancers. Here we show that mice with genetic knockout of Ppm1d or with conditional knockout of Ppm1d in the hematopoietic system, in myeloid cells, or in neutrophils all display significantly reduced growth of syngeneic melanoma or lung carcinoma tumors. Ppm1d knockout neutrophils infiltrate tumors extensively. Chemical inhibition of Wip1 in human or mouse neutrophils increases anti-tumor phenotypes, p53-dependent expression of co-stimulatory ligands, and proliferation of co-cultured cytotoxic T cells. These results suggest that inhibition of Wip1 in neutrophils enhances immune anti-tumor responses.

Subject terms: Cancer, Cell biology, Immunology, Molecular medicine

Wip1 is a negative regulator of the tumor suppressor p53 and is overexpressed in several human cancers. Here the authors show that inactivation of Wip1 in neutrophils promotes p53-dependent expression of co-stimulatory ligands and anti-tumor immune responses, reducing tumor growth in preclinical cancer models.

Introduction

Immunosurveillance by innate and adaptive immune cells can eliminate aberrant cells and provide effective suppression of tumor initiation1. However, sustained interactions between tumors and the immune system may lead to immunosuppression through immunoediting2. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-based anticancer therapies employ reducing immunosuppression as an effective therapeutic strategy3. However, current anticancer immunotherapies are only fully effective for a fraction of patients, reflecting the complexity of the immune response to tumors4. Along with other hematopoietic cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME), neutrophils shape the antitumor immune response and affect the efficacy of immunotherapeutic protocols. Neutrophils belong to the myeloid lineage of the innate immune system and play a dual role in cancer. At the early stages of tumorigenesis, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) stimulate antitumor immune responses5. Under continuous pathological signaling from tumor cells, neutrophils may acquire immunosuppressive properties and negatively regulate the principal antitumor effector cells, CD8 + cytotoxic lymphocytes, and NK cells6,7.

Modulation of immune responses in the TME by p53 is becoming recognized as a key aspect of its tumor-suppressive functions8–10. Wild-type p53-induced phosphatase, Wip1, the product of the PPM1D gene, is a metal-dependent serine/threonine protein phosphatase that is transcriptionally induced by p53 after exposure to DNA-damaging agents11,12. Cell-based studies have demonstrated that Wip1 negatively regulates several tumor suppressors, including p53, ATM, and MAPK13–16. The PPM1D gene is amplified and/or the Wip1 protein is overexpressed in several human cancers; tumors overexpressing Wip1 often retain wild-type p53, albeit with compromised functionality17–19. Wip1 accelerates tumorigenesis in several mouse tumor models and increases the incidence of spontaneous tumors13,20–23.

PPM1D exerts cell-type-specific effects during immune cell differentiation24,25. It positively regulates T- and B-cell development but negatively regulates neutrophil development26–30. Recent work suggests that the level of PPM1D/Wip1 activity in immune cells affects tumor progression. The presence of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) of PPM1D in immune cells but not in tumors of breast and ovarian cancer patients was associated with worse outcomes31. These somatic PTVs of the PPM1D gene were clustered in exon 6 and conferred “gain-of-function” through increased protein stability and activity32. For several additional cancers, the presence of PTVs of PPM1D in immune cells correlated with worse outcomes for patients33–36. Interestingly, in the recently recognized prepathological condition of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), the same PTVs were found and PPM1D was identified as a driver gene37. Unlike other CHIP driver genes, PPM1D mutations were not associated with increased risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML)38. Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) resulting from PPM1D exon 6 mutations was also found to be significantly associated with increasing age39 or prior exposure to chemotherapy40,41 and was generally associated with worse outcomes42.

We hypothesize that the Wip1 expression level in immune cells affects tumor progression by altering the degree of immunosuppression in the TME. We initiated a study of the effects of Wip1 expression levels or activity on antitumor immune responses.

In this work, we show that PPM1D is overexpressed in tumor-infiltrating neutrophils, both in humans and mice, and its genetic deletion or chemical inhibition in myeloid cells increases their anti-tumor phenotypes and suppresses tumorigenesis.

Results

Wip1 deficiency in the hematopoietic system suppresses tumor growth

To investigate the effects on tumor progression of reducing Wip1 expression in immune cells, we established mouse lines with conditional knockout of the Ppm1d gene. Through the Knock-Out Mouse Project (KOMP)43, exon 3 of the Ppm1d gene was identified as a critical exon, deletion of which results in loss of Wip1 expression and function (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We injected ES cells bearing the Ppm1dTm1a(KOMP)Wtsi gene-trapped allele into pseudopregnant C57Bl/6 mice. Through subsequent crosses of F2 progeny with C57Bl/6 β-actin-cre mice or C57Bl/6 β-actin-flp mice, respectively, we generated mice bearing the Ppm1dTm1b(KOMP)Wtsi allele, a germline Ppm1d knockout (referred to herein as Ppm1dKO2) that expresses the LacZ reporter protein under the control of the endogenous Ppm1d promoter, or mice bearing the conditional knockout allele Ppm1dTm1c(KOMP)Wtsi (referred to herein as Ppm1dfl), which expresses wild-type Wip1. Upon whole-body or tissue-selective exposure to cre recombinase, recombination between LoxP sites flanking exon 3 produces the knockout allele, Ppm1dTm1d(KOMP)Wtsi, referred to as Ppm1dKO3. The human FES promoter is highly active in hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cells; mice expressing the Fes-cre transgene are useful for studying gene deletion in the hematopoietic system44,45. Through successive intercrosses of Fes-cre mice with Ppm1dfl/fl mice, we produced Ppm1dfl/fl;Tg(Fes-cre) mice, referred to herein as Ppm1dFes-cre mice, which lack expression of Wip1 in hematopoietic cells (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Analysis of genomic DNA from Ppm1dfl/fl mice demonstrated the presence of the floxed exon 3 allele in both skin fibroblasts and liver samples (Supplementary Fig. 1c, left panel). In Ppm1dFes-cre mice, which express cre recombinase from the Fes-cre transgene only in hematopoietic progenitor cells, genomic DNA from liver sample, which contains liver-residing hematopoietic cells as well as hepatic cells, exhibited loss of exon 3 producing the 296-bp product that represented knockout allele (Supplementary Fig. 1c, right panel and Supplementary Fig. 1d). At the same time, skin fibroblasts, which lack hematopoietic cells, demonstrated the absence of the knockout allele in accordance with their respective hematopoietic cell content. Furthermore, we crossed R26R-EYFP reporter mice46 with Fes-cre mice to demonstrate successful cre-based recombination occurring in hematopoietic cells but not in other tissue types such as the intestinal epithelium (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Mice homozygous for the floxed allele, Ppm1dfl/fl, express wild-type Wip1 and are phenotypically indistinguishable from wild-type mice. In agreement with the results described previously for germline Wip1-knockout mice (Ppm1dtm1Lad/tm1Lad)27,28,47, Ppm1dFes-cre mice displayed reduced lymphocyte and increased granulocyte numbers in peripheral blood, with lymphopenia and neutrophilia progressing with age (Fig. 1a).

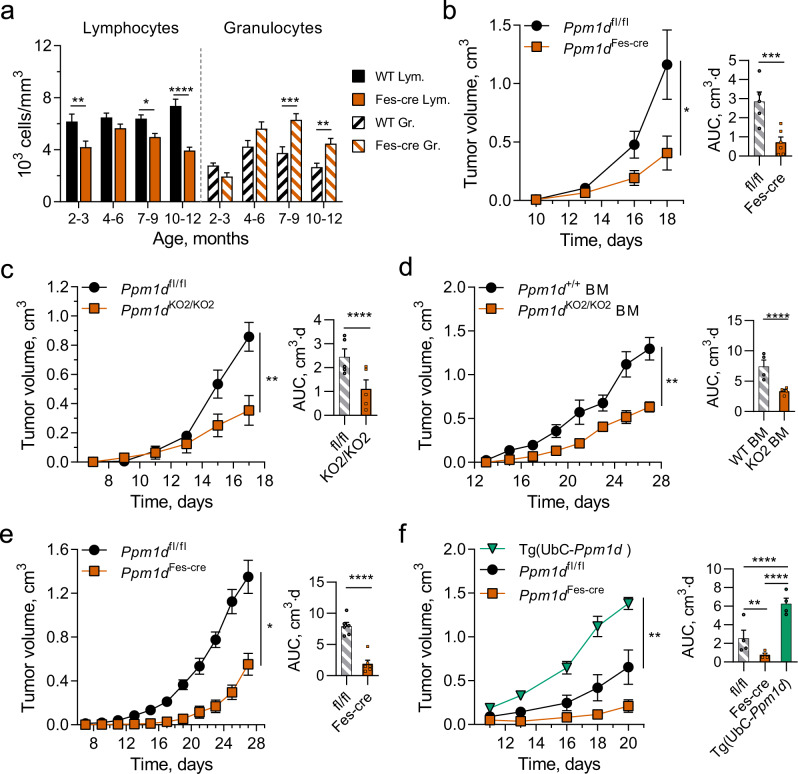

Fig. 1. Wip1 deficiency in hematopoietic cells suppresses the growth of solid tumors.

a Age-stratified lymphocyte and granulocyte numbers in peripheral blood of Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dFes-Cre (Ppm1dfl/fl;Fes-Cre) mice (n = 12 each genotype). b Tumor volume (left) and tumor growth area under the curve (AUC) (right) for growth of B16 F10 melanoma in Ppm1dfl/fl (n = 5) and Ppm1dFes-Cre (n = 6) mice. c Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (n = 5 each genotype). d Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in lethally irradiated WT mice with subsequent adoptive transfer of WT or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 bone marrow (BM) cells (n = 4 each genotype). e Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of LLC1 lung carcinoma tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dΔHSC mice (n = 6 each genotype). f Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of LLC1 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl, Ppm1dFes-Cre, and Tg(UbC-Ppm1d) mice (n = 4 each genotype). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. Student’s t test (two-tailed) (b–e), ordinary one-way ANOVA (f), and ordinary one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test (a): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (one representative experiment out of 3 is shown for Panel b–f). Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

We investigated the effects of depleting Wip1 in the hematopoietic system on tumor growth using the C57Bl/6 syngeneic B16 F10 melanoma and LLC1 Lewis lung carcinoma tumor models48,49. Compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice, we observed significantly reduced rates of B16 F10 tumor growth in Ppm1dFes-cre mice (Fig. 1b). We observed similar reductions in B16 tumor growth in Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (germline-knockout) mice compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice (Fig. 1c). To test whether the tumor-suppressive characteristic of Ppm1d-depleted immune cells is transferable to wild-type mice, we transplanted bone marrow (BM) cells isolated from wild-type or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice into lethally irradiated wild-type mice. We observed reduced rates of B16 tumor growth in WT recipient mice engrafted with BM cells from knockout compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1d). As deficiency of Wip1 has been reported to impair HSC functionality50, we confirmed effective engraftment of YFP-labeled Ppm1dKO2/KO2 donor cells 12 weeks after transfer into lethally irradiated WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, we challenged Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dFes-cre mice with LLC1 Lewis lung carcinoma cells. Similarly, the growth of LLC1 tumors was delayed in Ppm1dFes-cre mice compared with mice expressing wild-type Wip1 (Fig. 1e). Human population studies have demonstrated an association of less favorable patient outcomes with the presence, in blood cells, of PPM1D PTV variants that confer increased protein stability31,36,42. To investigate the effects of Wip1 overexpression, we used transgenic mice bearing the UbC-Ppm1d transgene, which ubiquitously expresses 2- to 4-fold higher levels of Wip151,52. Importantly, the growth of LLC1 carcinoma tumors was significantly faster in UbC-Ppm1d transgenic mice compared with either Ppm1dfl/fl or Ppm1dFes-cre mice (Fig. 1f). These experiments suggest that high levels of Wip1 in hematopoietic cells increase tumor progression.

Wip1-deficient neutrophils extensively infiltrate tumors

Tumor-bearing Ppm1dFes-cre mice exhibited significantly reduced lymphocyte counts and significantly increased granulocyte counts in peripheral blood, compared with tumor-bearing Ppm1dfl/fl mice (Fig. 2a). To investigate the mechanisms of tumor suppression resulting from depletion of Wip1 in hematopoietic cells, we characterized immune infiltrates in B16 melanoma tumors in Wip1 WT and Fes-cre mice by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 3). The numbers of CD45 + leukocytes infiltrated into B16–F10 tumors were higher in Ppm1dFes-cremice compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice, but the differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2b). The proportions of CD3 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, or CD8 + T cells (Fig. 2c) did not differ appreciably between Ppm1dFes-cre and Ppm1dfl/fl mice, despite substantial peripheral blood lymphopenia. Compared with tumors in WT mice, tumor-immune infiltrates in Ppm1dFes-cre mice exhibited significantly increased proportions of CD11b + myeloid cells, unchanged proportions of F4/80+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and significantly increased proportions of Ly6G+ tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) (Fig. 2d). Moreover, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed substantially increased numbers of neutrophil elastase-positive TANs in tumors from Ppm1dFes-crecompared with control mice (Fig. 2e).

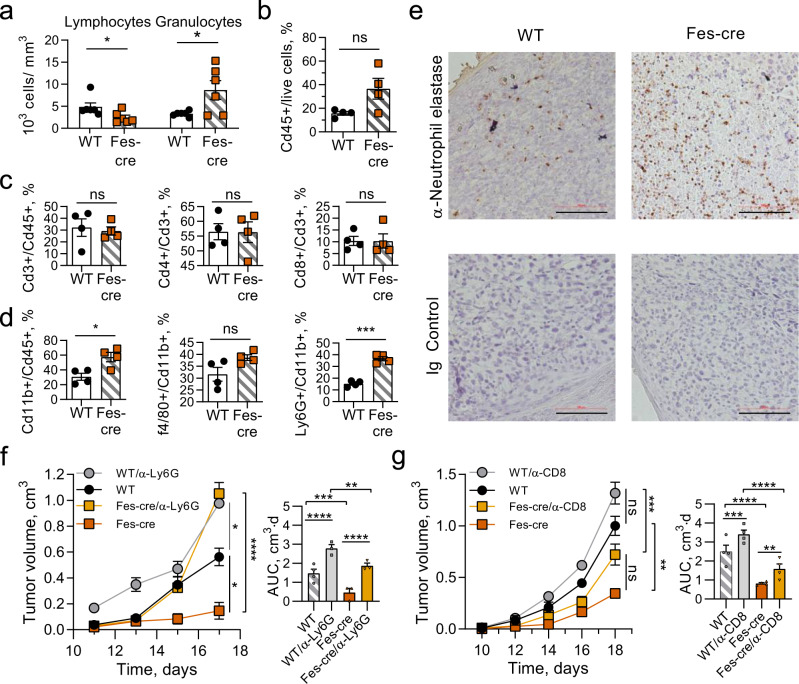

Fig. 2. Wip1-deficient neutrophils infiltrate tumors extensively and their depletion accelerates tumorigenesis in Wip1-deficient mice.

a Peripheral blood composition in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT) and Ppm1dFes-Cre (Fes-Cre) mice bearing B16. F10 melanoma tumors (day 16, n = 6 each genotype). Panels b–d: Infiltration of immune cells into B16 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT) and Ppm1dFes-Cre (Fes-Cre) mice (n = 4 each genotype). b Cd45+ leukocytes. c Cd3+ T cells, Cd4+ helper T cells, and Cd8+ cytotoxic T cells. d Cd11b+ myeloid cells, f4/80+ macrophages, and Ly6G+ neutrophils. e Neutrophil infiltration of B16 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dFes-Cre mice visualized by IHC. Neutrophil elastase-positive cells (α-Elane, brown) with counterstain (blue) (one representative experiment out of 4 is shown). f, g Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in WT and Ppm1dFes-Cre mice undergoing immune cell depletion by serial injection of neutralizing anti-Ly6G+ antibodies (panel f, n = 4 for WT and n = 3 for the remaining groups) or neutralizing anti-CD8+ antibodies (panel g, n = 4 for each group). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. Student’s t test (two-tailed) (a–d) or ordinary one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparison test (f, g): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, ns—nonsignificant (one representative experiment out of 2 is shown for panels f and g). Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

To test whether Wip1-deficient neutrophils directly contributed to tumor suppression, we depleted peripheral neutrophils through serial IV injections of neutralizing anti-Ly6G antibodies. Although neutrophil depletion resulted in increased tumor growth in both wild-type and Ppm1dFes-cre mice, neutrophil depletion in Ppm1dFes-Cremice markedly accelerated tumor growth, especially in the later stages (Fig. 2f). Similarly, we depleted peripheral cytotoxic CD8 + T lymphocytes (CTLs) through serial IV injections of neutralizing anti-CD8 antibodies (Fig. 2g). CTL depletion significantly accelerated tumor growth in Ppm1dFes-cremice, but the effects were smaller than the effects of neutrophil depletion. CTL depletion produced a slightly increased endpoint tumor volumes in both genotypes, but the increase did not reach statistical significance. Together, these observations suggest that genetic deletion of Ppm1d in immune cells suppressed the growth of isograft tumors in immune-competent mice through increased infiltration of neutrophils.

Wip1 inhibition affects neutrophil phenotypes

Recent work has demonstrated that neutrophils are heterogeneous, but the ontogenies and phenotypes of neutrophil subtypes remain incompletely understood53–55. A relevant aspect of neutrophil diversity is their potential polarization as antitumor N1 or pro-tumor N2 subtypes56,57. We investigated the effects of inhibition of Wip1 phosphatase activity by GSK2830371, a potent and specific inhibitor58, or genetic knockout of Ppm1d on the characteristics of isolated human and mouse neutrophils. When cultured in normal media, isolated human donor blood neutrophils are short-lived, with only 30% surviving 24 h and 5% surviving 36 h; inhibition of Wip1 phosphatase activity with GSK2830371 did not discernably alter the survival of nonactivated neutrophils (Fig. 3a). Compared with normal media, incubation with tumor-conditioned media (TCM) significantly extended their survival, both at 24 h and 36 h, whereas activation with TCM in the presence of GSK2830371 resulted in further significantly increased survival. Correspondingly, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) isolated from B16F10 tumors engrafted in Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice compared with Ppm1d+/+ mice exhibited significantly increased survival during TCM culturing (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Hence, loss of Wip1 activity by chemical inhibition or genetic deletion acts synergistically with soluble factors secreted by tumor cells to extend neutrophil lifespan. Transient production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through a respiratory burst is a neutrophil effector capability associated with antimicrobial and antitumor activity. Inhibition of Wip1 by GSK2830371 produced a dose-dependent increase in ROS production following PMA stimulation of TCM-activated human donor blood neutrophils (Fig. 3b). Similarly, PMA activation of TCM-stimulated murine BM neutrophils isolated from Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice exhibited significantly increased ROS production, compared with similarly treated Ppm1d+/+ BM neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 4b), consistent with a previous report27. Treatment of WT BM neutrophils with GSK2830371 in TCM prior to PMA stimulation did not significantly increase ROS production. Human neutrophils isolated from healthy donor blood displayed multilobed nuclei characteristic of mature neutrophils; incubation with TCM for 6 h resulted in the prevalence of neutrophils with highly segmented nuclei; addition of GSK2830371 further increased the frequency of highly segmented nuclear morphology (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 4c). In the absence of GSK2830371, prolonged incubation with TCM resulted in sparse neutrophil survival amid apoptotic neutrophils displaying condensed nuclei, whereas addition of GSK2830371 reduced the incidence of apoptotic cells. In agreement with a previous report27, genetic knockout of Ppm1d increased the prevalence of neutrophils with highly segmented nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Hence, genetic ablation of Ppm1d or chemical inhibition of Wip1 alters cell-intrinsic characteristics of human or mouse neutrophils consistent with increased N1 polarization.

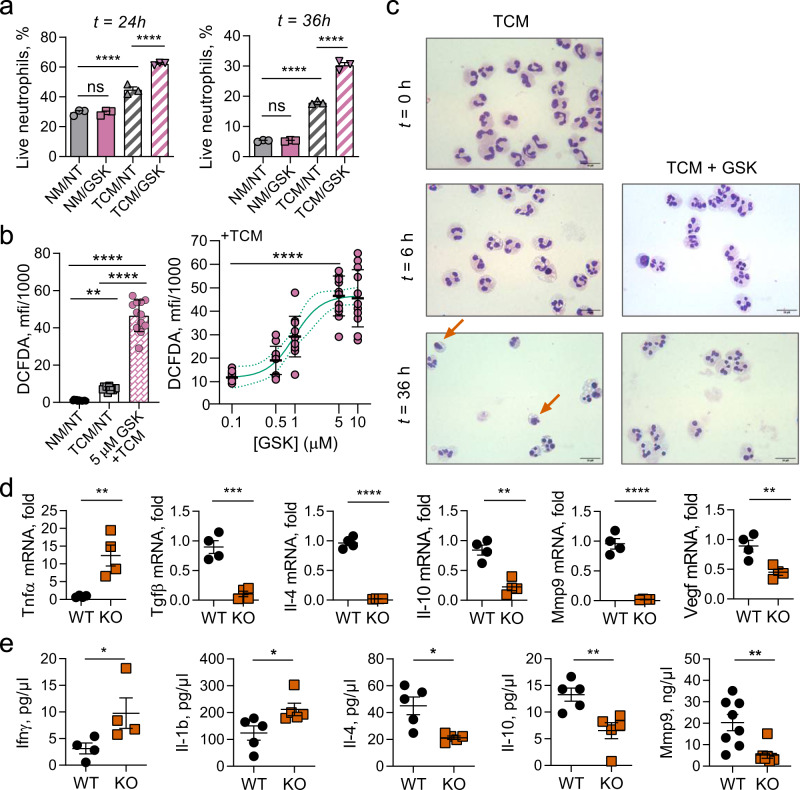

Fig. 3. Ppm1d-deficient mouse and Wip1-inhibited human neutrophils exhibit characteristics of N1 neutrophils.

a Survival of human donor blood neutrophils. Freshly isolated neutrophils were cultured in regular media (NA) or in tumor-conditioned media (TCM) and treated with vehicle (NT) or 5 μM GSK2830371 (GSK) for 24 h (left panel) or 36 h (right panel; n = 3 for each condition). b DFCDA (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) fluorescence as an indicator of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by donor blood human neutrophils preincubated with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of GSK2830371 for 6 h before activation with PMA (n = 12 for each condition). One-way ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis’ multiple- comparison test, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001; ****. c Morphology of human donor blood neutrophils cultured in tumor-conditioned medium (TCM) with vehicle (TCM) or 5 μM GSK2830371 (TCM + GSK) for 6 or 36 h. Red arrows indicate apoptotic neutrophils with condensed nuclei. Cytospin spreads were stained with May–Grünwald Giemsa solution and visualized by light microscopy. Scale bar, 20 μm (one representative experiment out of 6 is shown). d Relative mRNA levels of various cytokines in B16 melanoma tumors isolated 16 days after engraftment in Ppm1d +/+ (WT) or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (KO) mice (n = 4 for each genotype). e Multiplexed bead-based (Luminex) determination of selected cytokine protein levels in B16 tumor lysates from Ppm1d+/+ (WT) and Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (KO) mice (n = 4 for each genotype for IFNϒ, n = 5 for each genotype for Il-1b,4,10, and n = 8 for each genotype for MMP9). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. Student’s t test (two-tailed) (d), Mann–Whitney test (two-tailed) (e), or ordinary one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparison test (a): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

Through interactions with tumor cells, stromal cells, and other immune cells, neutrophil polarity can influence the cytokine posture of the TME59,60. We determined the levels of selected pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs in B16 F10 melanoma tumors isolated from WT or Wip1 KO hosts. Tumors from Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice expressed increased levels of TNFα mRNA and reduced levels of Il-4, Il-10, Mmp9, Tgfβ, and Vegf mRNAs, compared with tumors isolated from Ppm1d+/+ mice (Fig. 3d). TNFα has been shown to induce N1 phenotypes in neutrophils61. In contrast, Tgfβ has been implicated in tumor immune suppression and has been shown to induce N2 phenotypes in neutrophils56. Compared with N1 neutrophils, N2 neutrophils express higher levels of the cytokines Il-4 and Il-10, the extracellular remodeling factor Mmp9, and the angiogenesis-promoting factor Vegf62. We further used a multiplexed bead-based method to quantify the levels of selected cytokines in B16 tumors from Ppm1d+/+ and Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice. The levels of IFNγ and IL-1B were significantly higher and the levels of IL-4, IL-10, and MMP9 were significantly lower in tumors from Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice compared with Ppm1d+/+ mice (Fig. 3e). Exposure to high levels of IFNγ can increase N1 neutrophil polarization61.

Inactivation of Wip1 in neutrophils promotes tumor suppression

To confirm that Wip1-deficient neutrophils suppressed tumor growth in the absence of Wip1 deletion in adaptive immune cells, we generated mouse lines with myeloid targeting of Wip1 knockout. Among available mouse strains, none exhibits exclusive activity in neutrophils; we chose two models, LysM-cre and Mrp8-creTg, that exhibit high cre activity in neutrophils and differ in their activity profile in other myeloid immune subtypes63. In MRP8-creTg mice, expression of cre recombinase is driven by the Mrp8 (S100a8) promoter and is highly active in neutrophils and granulocyte–macrophage precursors64. We successively crossed Ppm1dfl/fl mice with MRP8-creTg mice to produce Ppm1dfl/fl; Tg(S100A8-cre-EGFP)1Ilw mice, referred to herein as Ppm1dMRP8-cre mice. Ppm1dMRP8-cre mice exhibited significantly reduced growth of B16 melanoma tumors (Fig. 4a). To further test the importance of deletion of Wip1 in myeloid cells, we used a second myeloid-targeting model. In LysM-cre mice, expression of cre recombinase is driven by the lysozyme 2 gene, which is highly active in myeloblasts and their monocyte, macrophage, and granulocyte progeny63,65. Through successive intercrosses of LysM-cre mice with Ppm1dfl/fl mice, we produced Ppm1dfl/fl; Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo mice, referred to herein as Ppm1dLysM-cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We further crossed Ppm1dLysM-cre mice with R26R-EYFP reporter mice46 to demonstrate genetic deletion of Ppm1d (Supplementary Fig. 5b) and loss of Wip1 protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 5c) in Cd11b + , YFP + myeloid cells. Similar to the above results, Ppm1dLysM-cre mice exhibited significantly reduced growth of B16 melanoma tumors (Fig. 4b) and LLC1 lung tumors (Fig. 4c), compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice.

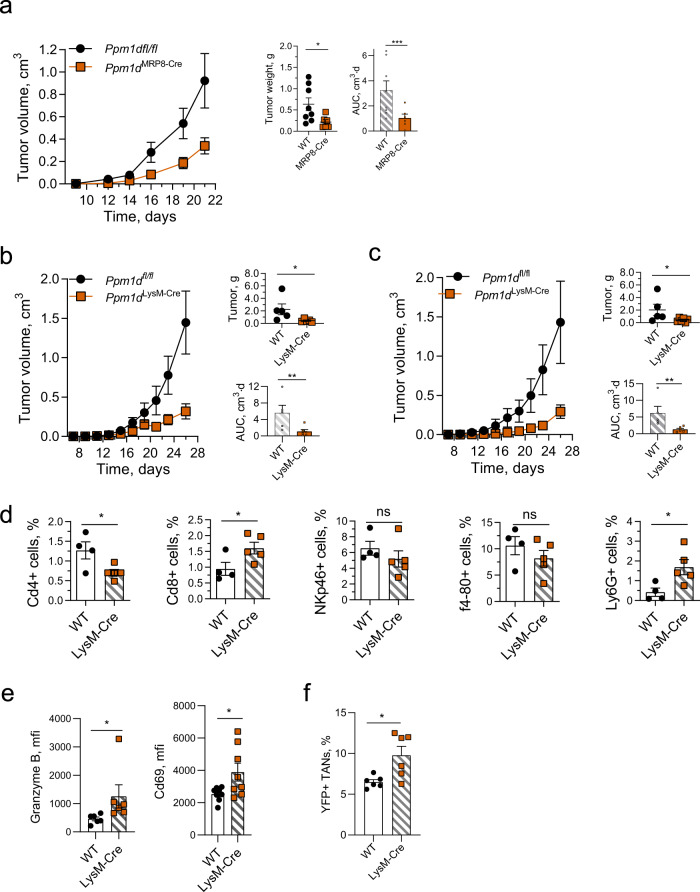

Fig. 4. Wip1 deficiency in myeloid immune cells suppresses the growth of solid tumors.

a Tumor volume (left), endpoint tumor weights (center), and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (n = 8) and Ppm1dMRP8-CRE (n = 6) mice. b Tumor volume (left), endpoint tumor weights (upper right), and tumor growth area under the curve (AUC) (lower right) for growth of B16 F10 melanoma tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (n = 5) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre (n = 6) mice. c Tumor volume (left), endpoint tumor weights (upper right), and AUC (lower right) for growth of LLC1 lung carcinoma tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (n = 5) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre mice (n = 6). d Infiltration by immune cell subsets into LLC1 tumors engrafted in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT, n = 4) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre (LysM-Cre, n = 5) mice. e Expression of activation markers in CD8 + T cells infiltrated in B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre (LysM-Cre) mice on day 16 (Granzyme B—n = 6, Cd69—n = 8 each genotype). f Infiltration of B16 F10 tumors by YFP + WTLysM-cre or YFP + Ppm1dLysM-cre neutrophils after their adoptive transfer in wild-type tumor-bearing mice (n = 6 for each genotype). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. Student’s t test (two-tailed) (panels d, e and panels a, b, c: tumor weights) or Mann–Whitney test (two-tailed) (panels a, b, e: AUC, and panel f): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (one representative experiment out of 3 is shown for panel a, b and one out of 2 is shown for panel f). Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

We characterized immune infiltrates in LLC1 lung cancer tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dLysM-cre mice (Fig. 4d). The numbers of CD4+ T cells were significantly reduced and the numbers of CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in Ppm1dLysM-cre mice compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice, suggesting an increased antitumor engagement of the adaptive immune system. The numbers of NKp46+ natural killer cells and of F4–80+ macrophages did not differ significantly in tumors from Ppm1dLysM-cre mice compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice. Similar to Ppm1dFes-cre mice, the numbers of TANs were approximately fourfold higher in tumors engrafted in Ppm1dLysM-cre compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice (p = 0.031). Moreover, as indicated by significantly higher expression of Granzyme B and CD69 markers, CD8 + cells infiltrated in B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dLysM-cremice were more highly activated, compared with WT mice (Fig. 4e). We confirmed the increased infiltration of neutrophils in Ppm1dLysM-cre mouse tumors by IHC (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). The chemokine receptor Cxcr2 regulates important aspects of neutrophil behavior, including release from the bone marrow and retention at sites of inflammation, including tumors66. Previously, neutrophilia in Ppm1dKO/KO mice was attributed to increased neutrophil Cxcr2 expression27. We found that the expression levels of Cxcr2 mRNA were significantly higher in Ppm1dKO2/KO2 TANs infiltrated in B16 F10 tumors, compared with Ppm1dfl/fl TANs (Supplementary Fig. 5f). To test whether this is a cell-intrinsic characteristic, we adoptively transferred YFP+, Ppm1d+/+, LysM-cre, or YFP+, Ppm1dfl/fl, and LysM-cre neutrophils to wild-type mice bearing B16 F10 tumors; YFP + neutrophils with deletion of Wip1- infiltrated tumors in significantly higher numbers compared with wild-type Wip1 YFP + neutrophils (Fig. 4f).

Based on EYFP reporter activity, both the LysM-cre and MRP8-cre models effectively produce deletion in 70–80% of neutrophils63. Based on the activity profiles of the LysM-cre and MRP8-cre models, we cannot exclude a possible involvement of Wip1-deficient macrophages in tumor suppression. The possible roles of Wip1-deficient macrophages in the TME lie outside the scope of the current investigation. In combination, the observed substantial increase in tumor infiltration by Wip1-deficient neutrophils, but not Wip1-deficient macrophages (Fig. 2d), and the complete reversal of tumor suppression in Wip1-deficient mice by depletion of neutrophils (Fig. 2f), suggests that Wip1-deficient neutrophils are primarily responsible for the observed phenotype in our models.

Wip1 inhibition increases expression of 4-1BBL and OX-40L

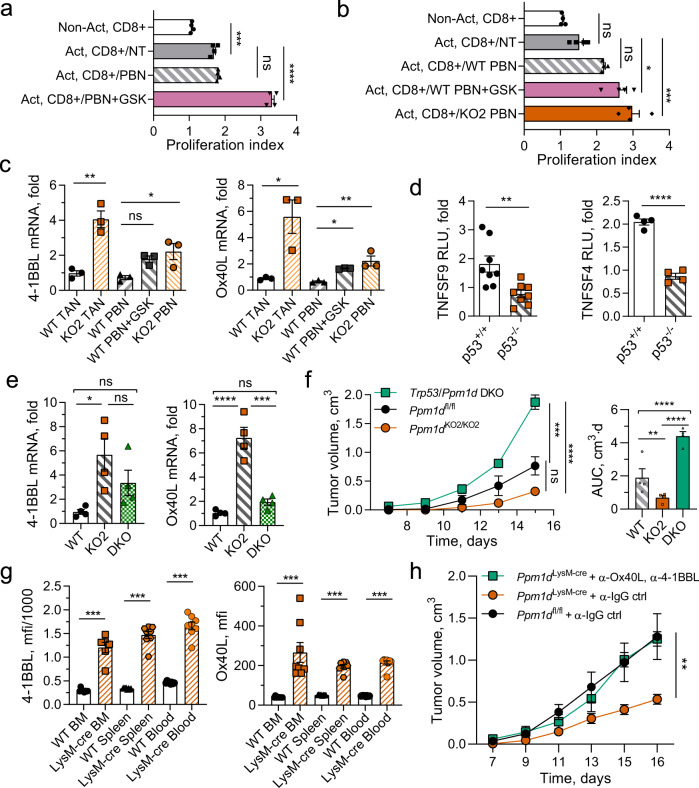

The activity of cytotoxic CD8 + T cells, the main mediators of antitumor immunity, can be modulated through interactions with neutrophils59,67. At early stages of human lung cancer, neutrophils contribute to the antitumor response by stimulating CD8 + T cells through the 4-1BBL/4-1BB and OX-40L/OX-40 pathways5. We investigated the effects of chemical inhibition of Wip1 in neutrophils isolated from human donor blood on their ability to costimulate the proliferation of human donor blood T cells (Fig. 5a). CD3/28-activated human CD8 + T cells exhibited significantly increased proliferation compared with nonactivated CD8 + T cells; coculturing with GSK2830371-pretreated human neutrophils further increased proliferation, whereas coculturing with nontreated human neutrophils had no additional effect. In addition, we observed significantly increased proliferation of CD3/28-activated murine CD8 + T cells following coculturing with Ppm1d+/+ (WT) neutrophils, GSK2830371-treated WT neutrophils, or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (KO) neutrophils, compared with activated CD8 + T cells cultured alone (Fig. 5b). Activation of murine CD8 + T cells by itself did not significantly increase their proliferation. Genetic deletion of Ppm1d or chemical inhibition of Wip1 activity in neutrophils increased the proliferation of coincubated human or mouse T cells.

Fig. 5. Chemical inhibition of Wip1 or genetic knockout of Ppm1d in neutrophils increased cytotoxic T-cell survival through p53-dependent induction of costimulatory ligands.

a Proliferation of human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Human donor blood CD8 + lymphocytes were not activated (Non-Act) or activated by incubation with CD3/28 beads (Act.) and cultured alone (NT), or coincubated with isolated human donor blood neutrophils pretreated for 6 h with vehicle (PBN) or 5 μM GSK2830371 (PBN + GSK) (n = 4 each condition). b Proliferation of murine cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Ppm1d+/+ peripheral blood Cd8+ lymphocytes were not activated (NT) or activated by incubation on CD3/28-coated plates (Act.) and cultured alone (NT), coincubated with Ppm1d+/+ neutrophils pretreated for 6 h with vehicle (WT PBN) or 5 μM GSK2830371 (WT PBN + GSK), or coincubated with Ppm1dKO2/KO2 neutrophils (KO PBN) (n = 4 each condition). c Expression of 4-1BBL mRNA (left panel) and OX40L mRNA (right panel) in neutrophils isolated from B16 tumors engrafted in Ppm1d+/+ mice (WT TAN) or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice (KO TAN), isolated from PB of Ppm1d+/+ mice and treated for with vehicle (WT PBN) or 5 μM GSK2830371 (WT PBN + GSK), or isolated from PB of Ppm1d KO2/KO2 mice (KO PBN) (n = 3 each condition). d Luciferase reporter assay of HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with pGL3 vector expressing luciferase under regulation of the human TNFSF9 (4-1BBL) promoter (left panel, n = 8) or the human TNFSF4 (OX40 L) promoter (right panel, n = 4). e Relative levels of 4-1BBL mRNA (left panel) and OX40L mRNA (right panel) in PBN isolated from Ppm1d+/+ mice (WT), Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice (KO), or Ppm1dKO2/KO2/Trp53KO/KO double-knockout mice (DKO) (n = 4 each genotype). f Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT), Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (KO2), or Trp53/Ppm1d double-knockout (DKO) mice (n = 4 each genotype). g Expression of 4-1BBL (left panel) and OX40L (right panel) protein levels on the surface of PPM1DKO2/KO2 neutrophils isolated from bone marrow, spleen, and blood (n = 8 each, except LysM-Cre BM n = 6). h Tumor volume for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dLysM-Cre mice after inactivation of 4-1BBL and OX-40L ligands on the surface of cells with serial injection of neutralizing anti-4-1BBL and anti-OX40L antibodies (n = 4 for each group, except Ppm1dfl/fl + α-IgG ctrl n = 7). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. Student’s unpaired t test (two-tailed) (panel d) and Mann–Whitney’s test (two-tailed) (panel g), one-way ANOVA (panels a–c, e, f), or two-way ANOVA (h): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (one representative experiment out of three is shown for panels f and h). Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

Proliferation of CD8 + T cells requires combined signaling through the T-cell receptor (TCR) and costimulatory pathways that include the 4-1BB and OX-40 receptors; the respective ligands, 4-1BBL and OX40 L, are often expressed by antigen-presenting cells and are critical for stimulating the proliferation and activation of cytotoxic T cells68,69. We investigated whether expression of these costimulatory ligands in neutrophils was affected by Wip1 phosphatase. The relative levels of 4-1BBL and OX40 L mRNAs were significantly higher in B16 TANs from tumors engrafted in Ppm1dKO2/KO2 compared with Ppm1d+/+ (WT) mice (Fig. 5c). For both 4-1BBL and OX-40L, the respective mRNA levels were nearly the same in WT PBNs as in WT TANs, but the levels were higher in KO PBNs or following incubation with GSK2830371. These results suggest that genetic deletion of Ppm1d or the loss of Wip1 activity in neutrophils increased the expression of the costimulatory ligands 4-1BBL and OX40L in neutrophils.

Among its many functions, the tumor suppressor p53 regulates immune responses in the tumor microenvironment9,10. p53 regulates the expression of several tumor necrosis factor super family (TNFSF) cytokines, including 4-1BBL (TNFSF9) and OX-40L (TNFSF4)70–72. We used the public p53 Binding and Expression Resource (BAER)73 to examine the correlation between p53 binding to chromatin near the TNFSF9 and TNFSF4 genes and changes in their expression. Chip-seq data for the TNFSF9 gene show a peak of p53 occupancy in chromatin +47 kb from the transcription start site (TSS) in lymphocytes and selected cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In the corresponding differential gene expression data sets, TNFSF9 was significantly (adjusted p < 0.01) and substantially (fold change >1.5) upregulated in lymphocytes and fibroblasts treated with doxorubicin (DXR) but not in lymphocytes or U2OS cells treated with Nutlin73,74. Interestingly, the genomic region +47 kb from the TNFSF9 TSS functions as an enhancer to regulate expression of TNFSF9 and CD70, another TNFSF costimulatory cytokine75. In the same datasets, chip-seq data for the TNFSF4 gene show a peak of p53 occupancy in chromatin in intron 1 (+1.3 kb from the TSS or −0.5 kb from an alternative TSS) (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Both regions of high p53 chromatin occupancy contain a sequence resembling the canonical p53 response element (Supplementary Fig. 6c). To provide additional support for p53-dependent induction of the TNFSF9 (4-1BBL) and TNFSF4 (OX-40L) genes, we constructed plasmids expressing luciferase under the control of the TNFSF9 or TNFSF4 promoters and transfected these reporter vectors into HCT116 cells with or without functional p53 (Fig. 5d). With both reporter vectors, we observed significantly increased luciferase activity in HCT116 cells with WT p53 (WT) compared with HCT116 cells lacking p53 (p53−/−).

Through intercrosses of mice bearing the Ppm1dKO2 and Trp53KO 14,15 knockout alleles, we obtained mice with homozygous double knockout of Wip1 and p53 (Ppm1dKO2/KO2;Trp53KO/KO, DKO) and investigated the growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dfl/fl (WT), Ppm1dKO2/KO2, and DKO mice. The levels of 4-1BBL and OX-40L mRNAs in B16 TANs from Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice were significantly increased compared with their respective levels in B16 TANs from WT mice (Fig. 5e). Importantly, the relative mRNA levels for both costimulatory cytokines, although higher, were not significantly increased in B16 TANs from DKO mice compared with B16 TANs from WT mice. We further investigated the rates of B16 melanoma tumor growth WT, KO, and DKO mice (Fig. 5f). In agreement with our earlier results, the growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice was significantly reduced compared with Ppm1dfl/fl mice. Deletion of p53 substantially increased the rate of tumor growth compared with either WT or Ppm1dKO2/KO2. Thus, deletion of p53 attenuated antitumor activity of Wip1-deficient hematopoietic cells both in vitro and in vivo.

In addition, we have verified at protein level, that both ligands 4-1BBL and OX-40L are highly expressed on the surface of Ppm1d-deficient neutrophils isolated from bone marrow, spleen, and blood (Fig. 5g). Moreover, the neutralization of 4-1BBL and OX-40L on the surface of cells with specific antibodies in Ppm1dLysM-cre mice attenuated the tumor-suppressive effect of Ppm1d deletion in myeloid cells and significantly accelerated the tumor growth to the same ratio as in wild-type mice (Fig. 5h).

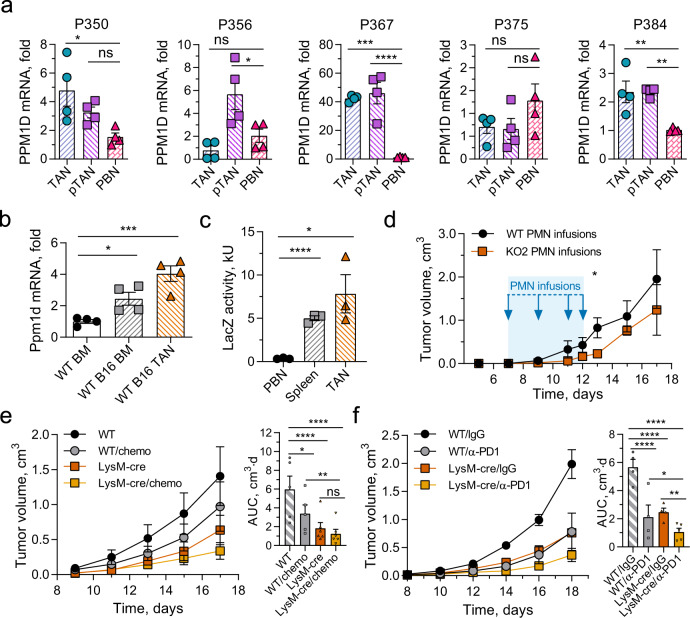

Wip1 inactivation in myeloid cells potentiates antitumor therapies

Our results show that Wip1 is an important modulator of neutrophil behavior, especially as it relates to the organismal antitumor immune response. In four out of five patients with lung cancer, PPM1D mRNA levels were significantly elevated in either TANs, neutrophils isolated from peritumor tissues (pTANs), or both, compared with the patient’s PBN PPM1D mRNA levels (Fig. 6a). In addition, we investigated the expression level of Ppm1d mRNA in neutrophil populations in tumor-free and B16 F10 melanoma tumor-bearing WT mice (Fig. 6b). Compared with Ppm1d mRNA levels in BM neutrophils from tumor-free WT mice, Ppm1d mRNA levels were significantly increased both in BM neutrophils from tumor-bearing mice and in TANs. Next, we used heterozygous Ppm1d+/KO2 mice, in which the KO2 allele expresses Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (LacZ) under the control of the endogenous Ppm1d promoter. Compared with Ppm1d promoter activity in PBNs, Ppm1d promoter activity was significantly higher in B16 TANs and spleen neutrophils (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6. Tumor-associated neutrophils express high levels of Wip1 and inactivation of Wip1 in myeloid cells enhances antitumor responses.

a Relative PPM1D mRNA levels in neutrophils isolated from surgically resected tumors (TAN), peri-tumor tissues (pTAN), or peripheral blood (PBN) from five patients with Stage I–II lung cancer (n = 5 different patients examined over 4 individual experiments). b Relative Ppm1d mRNA levels in neutrophils isolated from bone marrow of naive (WT BM) or B16 tumor-bearing (WT BM B16) Ppm1d+/+ mice and from B16 tumors engrafted in Ppm1d+/+ mice (WT TAN B16) (n = 4 each condition). c Flow cytometry analysis of LacZ activity in neutrophils isolated from peripheral blood (PBN), spleen (Spleen), or B16 tumors (TAN) of tumor-bearing Ppm1d promoter LacZ reporter mice (Ppm1d+/KO2) (n = 3 each condition). d Growth of B16 melanoma tumors in WT mice treated on days 7, 9, 11, and 12 (blue arrows) with injection of neutralizing anti-Ly6G+ antibodies to deplete host neutrophils and infusion of Ppm1d+/+ (WT PMN) or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 (KO PMN) donor neutrophils (n = 4 each genotype). e Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1d+/+ (WT, n = 5 each condition) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre (LysM-Cre, n = 6 each condition) mice without and with oxaliplatin+5FU combination chemotherapy (chemo). f Tumor volume (left) and AUC (right) for growth of B16 F10 tumors in Ppm1d+/+ (WT, n = 4 each condition) and Ppm1dLysM-Cre (LysM-Cre, n = 4, untreated, n = 5 α-PD1) mice without and with anti-PD1 antibody treatment (α-PD1). Data are depicted as means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s (a–c) or Sidak’s (e, f) multiple- comparison test or Student’s t test (two-tailed) (d, day 13): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (one representative experiment out of two is shown for panel d and out of three is shown for panel e, f). Source data are provided as a Source Excel Data file.

Our findings suggest that in the tumor microenvironment, Wip1 deficiency reprograms neutrophils toward higher antitumor potential, in part through increased expression of lymphocyte costimulatory ligands. These observations may have potential therapeutic utility. Although the recently developed Wip1 inhibitor is potent and specific, it exhibits poor pharmacokinetics58. Moreover, systemic inhibition of Wip1 produces both direct effects of Wip1 inhibition in tumor cells and indirect effects of Wip1 inhibition in infiltrated immune cells. To test whether inhibition of Wip1 activity in neutrophils enhances antitumor responses, we treated tumor-bearing WT mice with serial WT or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 neutrophil infusions. Mice receiving Wip1-deficient neutrophil infusions showed significantly slower growth of B16 melanoma tumors compared with mice receiving WT neutrophil infusions (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Interestingly, tumor growth in mice treated with Wip1-deficient neutrophils accelerated rapidly when treatment was stopped after day 12.

We investigated the potential benefits of combining conventional chemotherapy or current immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy with ablation of Wip1 activity in neutrophils. Treatment with oxaliplatin and 5FU significantly delayed the growth of B16 F10 melanoma tumors in WT mice, but did not significantly delay tumor growth in Ppm1dLysM-cremice; combining chemotherapy with Wip1 deficiency in neutrophils resulted in greater tumor suppression (Fig. 6e). Similarly, combining anti-PD1 antibody treatment with Wip1 deficiency in neutrophils more effectively reduced melanoma tumor growth compared with monotherapy with anti-PD1 or Wip1 deficiency alone (Fig. 6f).

Discussion

Chemotherapy remains one of the main treatment strategies in oncology, but the effects of cytotoxic treatments on the immune system and immune cell–tumor interactions in the TME are currently active areas of investigation. Activation of the DNA damage response pathway by chemotherapeutic drugs not only induces tumor cell lethality, but additionally remodels the TME and alters antitumor immune responses. DNA damage-induced activation of the p53 signaling pathway exerts cell-type- specific selective pressures. In tumors, chemotherapy-induced selection leads to the survival of clones of tumor cells bearing mutations that afford increased resistance to cytotoxic treatments. In the hematopoietic system, chemotherapy-induced selection may lead to CH, in which the presence of somatic mutations of critical genes in hematopoietic progenitors provides survival and proliferative advantages under cytotoxic selection and produces clonal expansion of hematopoietic progeny with altered phenotypes76. Among CH driver genes, mutations in PPM1D and TP53 were most significantly associated with prior exposure to chemotherapy77. PPM1D “gain-of-function” mutations provide selective advantage in tumor cells32,78,79 and in the hematopoietic system, resulting in therapy-induced CH40,80. Interestingly, the splice variant PPM1D430, which shares salient characteristics with CH-associated PPM1D PTVs and has been detected in several cancer cell lines, is expressed only in leukocytes and testes, among normal tissues tested81.

The presence of PPM1D protein-stabilizing PTVs in the blood cells of patients with several types of solid tumors correlates with worse outcomes31,33–36,82 Our study suggests a possible mechanism linking the presence of clonal expansions of blood cells bearing PPM1D PTV mutations with worse outcomes for patients with neoplastic disease. Here we have shown that Wip1 negatively regulates the antitumor functions of myeloid cells.

We observed that overexpression of Ppm1d in blood cells in mice accelerated the growth of solid tumors, whereas deletion of Ppm1d in blood cells suppressed tumor growth. The loss of Wip1 expression in the hematopoietic system significantly increased the infiltration of solid tumors by myeloid granulocytes. Moreover, we observed that the suppression of tumor growth resulting from loss of Wip1 depended on the presence of neutrophils.

Ppm1d-knockout mice exhibit marked neutrophilia that progresses with increasing age28. Increased Ppm1d activity prevents the differentiation of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) to pro-inflammatory mature granulocytes27. We confirmed here that conditional deletion of Ppm1d in the hematopoietic system increased the number of neutrophils in mouse blood and altered neutrophil phenotypes.

During the early phase of tumorigenesis, neutrophils contribute to the antitumor immune response, possibly through stimulation of adaptive immunity and enhancement of CD8 + cytotoxic lymphocyte efficiency5. During the later stages, tumors evade recognition by the immune system and promote an immune-suppressive state through recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs), including polymorphonuclear (PMN-MDSCs), which share phenotypic and morphologic features with neutrophils7. In the TME, MDSCs block the function of the immune effector cells, T-lymphocytes and NK cells, resulting in ineffective removal of tumor cells by the immune system; MDSCs seriously compromise the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies83. Recently, strategies directed either to eliminate MDSCs or to reprogram PMN-MDSCs have been proposed to increase the efficiency of immune checkpoint inhibitors84,85.

In our study, genetic depletion of Ppm1d in neutrophils transformed them into efficient activators of CD8 + cytotoxic lymphocytes, in part, through p53-dependent induction of lymphocyte costimulating ligands 4-1BBL and OX-40L. Due to the limitation of conditional mouse models, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that certain subsets of monocytes/macrophages myeloid cells share some responsibility for the observed phenotype. Though in our model a single Ppm1d targeting anticancer strategy was already very efficient, the depletion of Ppm1d in myeloid cells potentiated both anticancer chemotherapy and anticancer immunotherapy. Increased CTL activation and survival is critical for efficacy of the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) transfer and immune checkpoint therapy86. There is a rationale for combining immune checkpoint therapy with genetic or chemical inhibition of Wip1. Currently, immune checkpoint therapies target negative regulators of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and NK cells, such as PD1. In contrast, Wip1 depletion elevates lymphocyte-stimulatory signals in the tumor microenvironment by inducing expression of the stimulatory ligands OX40L and 4-1BBL on the surface of tumor-associated neutrophils. Therefore, by targeting distinct components of the lymphocyte-regulating system, Wip1 inhibition may potentiate anti-PD1 therapy by making antitumor immunotherapy more efficient.

As a practical approach, inhibition of PPM1D activity by chemical compounds in neutrophils or their precursors could be a valuable strategy to increase the efficiency of current anticancer immunotherapies through CTL stimulation in the TME. This strategy will be particularly important in oncological patients with clonal hematopoiesis driven by PPM1D-activating mutations to improve treatment outcomes.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. This study has complied with all relevant ethical regulations and informed consent from participants was obtained. Five patients with stage I–II lung cancer, who were scheduled for surgical resection, consented to tissue collection of a portion of their tumor and/or blood for research purposes. Detailed characteristics of the patients are provided in Supplementary table 1. For donors’s blood, ethical review and approval were done by the French Blood Transfusion Center (Etablissement Français du Sang Bourgogne Franche-Comté, Besançon, France). The blood samples were collected within the agreement between the EFS and the Bourgogne Franche-Comté University according to a national blood bank (Etablissement Français du Sang) rules and policies, with written informed consent specifying the exclusive research purpose and the respect of ethical guidelines.

Mouse models

All animals were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities in accordance with FELASA and Animal Experimental Ethics Committee guidelines (University of Burgundy, France) or with NCI Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (NCI). This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research and received ethical approval from the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee (University of Burgundy, France) or with the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee (NCI). Animals had water ad libitum and were fed regular chow. All experiments were carried out in accordance with guidelines prescribed by the Ethics Committee at the University of Burgundy and the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed in 8–12-week-old female of the immunocompetent C57Bl/6 background. Littermate animals from different cages were randomly assigned into experimental groups and were either cohoused or systematically exposed to other groups’ bedding to ensure equal exposure to common microbiota.

The following strains were generated by our lab using resources from the trans-NIH Knock-Out Mouse Project:43 Ppm1dKO2 (C57BL6-Ppm1dTm1b(KOMP)Wtsi), Ppm1dfl (C57BL6-Ppm1dTm1c(KOMP)Wtsi), and Ppm1dKO3 (C57BL6-Ppm1dTm1d(KOMP)Wtsi). The mouse strains C57BL/6 J, R26R-EYFP (C57BL6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos/J)46, LysM-cre (B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo/J)65, and MRP8-creTg (B6.Cg-Tg(S100A8-cre-EGFP)1Ilw/J)64 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Tp53KO mice (B6.129-Trp53tm1Brd/N)87 were provided by L. Donehower (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA). β-actin-creTg (C57BL/6J-Tg(β-actin-cre)) mice88 and β-actin-flpTg (C57BL/6J-Tg(β-actin-flp)) mice89 were provided by L. Tessarollo (Mouse Cancer Genetics Program, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA). Fes-cre (C57BL6-Tg(Fes-Cre)31Bsl) mice44 were provided by P. P. Pandolfi (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Ubc-Ppm1d C57BL6-Tg(Ubc-Ppm1d) mice51,52 were provided by D. Bulavin (Institute for Research on Cancer and Aging Nice, France).

Cell lines and primary cell cultures

Cell lines were obtained from ATCC and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (LLC1 and HTC116) or in RPMI-1640 Medium (B16 F10 and DLD-1) with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin/amphotericin B (PSA), and 4 mM of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination. Commonly misidentified cell lines were not used.

Isolated CD3+ T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (heat-inactivated) supplemented with MEM nonessential amino acids (MEM-NEAA), sodium pyruvate, PSA, and 4 mM HEPES and stimulated with plate-bound antibodies against CD3 (2 µg/ml) and CD28 (2 µg/ml).

Cancer cell transplantation and organ harvest

B16 F10 murine melanoma cells (2 × 105) (syngenic with C57BL/6 mice) or murine Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC1) cells (3 × 105) (syngenic with C57BL/6 mice) suspended in 100 μl of Dulbecco-modified phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of C57BL/6 mice. Tumor growth was monitored every second or third day using electronic calipers. Tumor size was calculated as (tumor volume = (length × width2)/2)). The tumor growth Area Under the Curve metric integrates time-series data using trapezoidal approximation90. Mice were euthanized when the tumor reached 1000–2000 mm3, organs were dissected, and single-cell suspensions were prepared from tumor tissue by mechanical disruption followed by enzymatic digestion of 4–6-mm pieces using a cocktail of Collagenases I (45–60 μ/mL), II (15–20 μ/mL) and IV (45–60 μ/mL), and 100 μg/ml DNase I (Roche) in RPMI medium, as described5. Digestion mixtures were sequentially passed through 70-μm and 30-µm cell strainers and washed with PBS supplemented with 2 mM EDTA and 1% FBS. Following lysis of erythrocytes using red blood cell lysis buffer (RBC lysis buffer: 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA), cells were used for immune staining.

Bone marrow transplantation and chimeric mice

Bone marrow chimeric mice were obtained as described elsewhere91,92. Briefly, pooled tibial and femoral bone marrow cells from donor mice were lysed with RBC lysis buffer and assessed for viability with trypan blue. Bone marrow cells were injected retro-orbitally into recipient WT mice (107 cells per each recipient mouse) irradiated with a single dose of 9 Gy. Animals were maintained on trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (Hi-Tech Pharmacal) antibiotic water from 1 day prior through 2 weeks after irradiation. Tumor transplantation into chimeric mice was performed at least 8 weeks after reconstitution. Hematopoietic reconstitution of all animals was verified by blood composition analysis using a Scil Vet hemocytometer and by flow cytometry at the end of the experiment.

Mouse in vivo treatments

Depletion of neutrophils or T cells was affected by intravenous (IV) injection of 200 μg of anti-mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8) or anti-mouse CD8α (clone YTS 169.4) antibodies (Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH, USA). Immune cell depletion was verified by blood composition analysis using Scil Vet hemocytometer and flow cytometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). Depleting antibodies were first injected 48 h before tumor isograft implantation; subsequent injections of depleting antibodies were repeated every 3–4 days. BM cells were isolated from WT or Ppm1dKO2/KO2 mice, and BM PMNs were purified using MACS enrichment following the manufacturer’s protocol, yielding BM PMNs of >90% purity and 95% viability, as determined by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Mice were transfused with 2 × 106 BM PMNs in 200 µL of physiological serum by retro-orbital injection (at days 7, 9, 11, and 12). For adoptive transfer of YFP + WTLysM-cre and YFP + Ppm1DLysM-cre neutrophils, neutrophils were isolated using Neutrophil Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and sorted by FACS (ARIA III, BD Bioscience) (Supplementary Fig. 7b); B16 F10 tumor-bearing mice were then transfused 2 days before the endpoint with 2 × 106 cells in 200 µL of physiological serum by retro-orbital injection. For chemotherapy treatment, mice received 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (5 mg/kg) and oxaliplatin (6 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection once weekly (treatment on days 9 and 13). For anti-PD1 treatment, mouse received 200 µg of anti-PD1 (InVivoMab anti-mouse PD1) (Cd279) (clone RMP1–14) via intraperitoneal injection twice weekly (treatment on days 8, 11, 14, and 17). For anti-OX-40L and 4-1BBL treatment, mouse received 250 µg of anti-OX-40L (InVivoMab anti-mouse OX-40L) (Cd134L) (clone RM34L) and anti-4-1BBL (InVivoMab anti-mouse 4-1BBL) (Cd137L) (clone TKS-1) via intraperitoneal injection every 3 days (treatment on days 6, 9, 12, and 15).

Blood composition analysis

Age-dependent blood composition was analyzed in cohorts of Ppm1dfl/fl and Ppm1dΔHSC mice (n = 10 each genotype). At intervals, a drop of blood from the tail vein was deposited in an EDTA-coated tube (BD Bioscience). Complete blood counts were performed using an automatic hematoanalyser (ScilVet ABC plus).

Cell purification and in vitro coculture

Mouse

Naive CD3+ T cells were obtained from spleens and lymph nodes of C57BL/6 wild-type mice. Cells were purified using the MACS Cell Separation system (Pan T Cell isolation kit, Miltenyi Biotec). Neutrophils were obtained using a mouse Neutrophil Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of isolated T-cell and neutrophil populations routinely exceeded 90%. Naive CD3+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound antibodies against CD3 (2 µg/ml) and CD28 (2 µg/ml) (BioLegend) in the absence or presence of neutrophils. B16F10 cells were used as a source of TCM for ex vivo experiments with murine neutrophils.

Human

CD3+ T cells were obtained from buffy coat preparations of human healthy donor blood. T cells were purified using a Pan T Cell Isolation Kit and restimulated with a human T Cell Activation/Expansion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Neutrophils from the same donor were obtained by density-gradient centrifugation. TCM (tumor-conditioned media) was prepared by culturing human melanoma SK-MEL cells in DMEM/10% FBS for 72 h under standard cell culture conditions followed by filtration through a sterile 0.45-μm PVDF filter (Millipore).

Preparation of a single-cell suspension from tumor and adjacent lung tissue

Surgically removed fresh lung tumors and adjacent uninvolved lung tissue were processed within 20 min of removal from the patient following the protocol as previously described5,93. Briefly, tumor and adjacent uninvolved lung tissue was sliced into 1–2-mm3 pieces and digested by enzymes. After 45 min, any visible tumor pieces were vigorously pipetted and then further incubated for 30–50 min under the same conditions. The supernatant was passed through a 70-μM nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon). The remaining pieces in the tube underwent further pipetting before being passed through the same cell strainer. Typically, less than 5% of the tissue remained on the cell strainer. After filtration, the red blood cells were lysed using 1x Red Blood Cell (RBC) Lysis Buffer (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX). The remaining cells were washed twice in RPMI supplemented with 2% FBS and resuspended in the cell culture media.

Neutrophil isolation from human lung tumors

Since temperature gradients can activate neutrophils, all tissues and reagents were maintained at a constant temperature during preparation. After tumor harvest, the neutrophil populations used in this study were prepared at room temperature (RT) and rapidly utilized. TANs were isolated from tumor single-cell suspensions using positive selection of CD66b + cells with microbeads as previously described5,93. PBNs were obtained from EDTA anticoagulated peripheral blood collected from lung cancer patients during surgery or from healthy donors. The PBNs were obtained from Lymphoprep (Accu-Prep, 1.077 g/ml, Oslo, Norway) density-gradient centrifugation followed by erythrocyte lysis with 1x RBC Lysis Buffer. To account for any possible effect of tissue digestion enzymes on the function neutrophils, peripheral blood granulocytes were processed in a similar manner. Specifically, peripheral blood granulocytes were incubated with enzymatic cocktail before positive selection using microbeads.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were resuspended in BD stain buffer (BD Bioscience) for 15 min prior to staining with specific antibodies. Antibodies against cell markers: anti-CD45, anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8a, anti-CD11b, anti-F4/80, anti-Ly6G, anti-Ly6C, anti-NKp46(CD335), anti-B220, and anti-CD69, were purchased from BD Bioscience and BioLegend; anti-OX40L and anti-41BBL from Miltenyi Biotec (detailed in Supplementary table 4). Samples were mixed with FVS700 (1/7000) and data were acquired on an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). ROS generation in cultured neutrophils was determined using either DCFDA/H2DCFDA-Cellular ROS Assay Kit (ab113851) following the manufacturer’s protocol or a dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescent probe. Cells were incubated with DHE (10 μM) in HBSS containing 1.5 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 for 30 min at 37 °C and analyzed by flow cytometry. LacZ activity was determined by flow cytometry using Fluorescein di[β-D-galactopyranoside (Sigma, F2756) as described elsewhere94.

Immunohistochemistry

FFPE tumor sections (5 µm) from B16–F10 or LLC1 tumors were used to determine the infiltration of neutrophils by immunohistochemistry using rabbit anti-neutrophil elastase antibody (ab68672) (Abcam). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, washed, and incubated with secondary antibodies (Dako EnVision+ System HRP Labelled Polymer Anti-Rabbit) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin counterstain and coverslips were mounted using nonaqueous mounting media.

Measurement of cytokines

The profiling of selected cytokines and chemokines was performed by a Mouse Luminex assay (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using fresh tumor lysates from equivalent tumor pieces and read on Bio-Plex 200 system (BioRad).

For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were cultured as described above and then stimulated for 4 h at 37 °C in culture medium containing Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml, Sigma) and monensin (2 μM, BioLegend). After staining for surface markers (cf. Flow cytometry section), cells were fixed and permeabilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences), then intracellular staining was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the fixation/permeabilization solution (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA from T cells was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen). In all, 300 ng of total RNA was transcribed into cDNA by M-MLV reverse transcriptase with random primers in the presence of RNaseOUT RNAse inhibitor (Invitrogen). cDNAs were quantified by real-time PCR with a SYBR Green Real-time PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) on a Viaa7 detection system (Applied Biosystems, France). Relative mRNA levels were determined with the ΔCt method. Oligonucleotides used for qRT-PCR are described in Supplementary table 2.

Transient transfections and luciferase transactivation assay

The pTNFSF4-luc and pTNFSF9-luc luciferase reporter constructs were generated by inserting the promoter sequences of the human TNFSF4 and TFNS9 genes, respectively, into the multicloning site of the pGL3 basic vector (Promega). Human genomic DNA was isolated from DLD-1 cells by standard methods. Fragments were amplified by high-fidelity PCR using human DNA as the template and specific primers given in Supplementary table 3.

HCT116 (p53+/+) or HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with reporter plasmids (pTNFSF4-Luc, pTNFSF9-Luc, or pGL3 basic vector) and pSV-β-Galactosidase control vector (Promega) using GenJet™ In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (Ver. II) (Sinagen). β-Galactosidase activity was measured using the β-Galactosidase Enzyme Assay System (Promega) after 30 min of incubation at 37 °C with detection at 420 nm. Luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luciferase activity was measured using an EnVision 2105 Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer).

Data collection and analysis

Flow cytometry data were collected using FACSDiva (BD Biosciences, version 8.0.1). qPCR data were collected using ViiA™ 7 Software (Applied Biosystems, version 1.2). Luminescence data were collected using PerkinElmer Envision Manager (v1.13.3009.1401). Flow cytometry data were analyzed on FlowJo software (Tree Star, v10.0.2).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The results are shown as mean ± SD or SEM, and data sets was compared using unpaired Student’s t-test or ordinary one-way or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. We performed statistical calculations with GraphPad Prism 8.3. All p values were two-tailed. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all experiments.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by La Ligue contre le Cancer, Russian Science Foundation grant 19-75-20128, Foundation ARC, Russian Foundation for Basic Research grants 19-315-51035, the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Russian Foundation for Basic Research grants 18-29-09144, and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER No. 2016-00110366 and EX005756). The mouse strain C57BL6-Ppm1dTm1a(KOMP)Wtsi was generated by the Mouse Cancer Genetics Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, using ES cells generated by the trans-NIH Knock-Out Mouse Project and obtained from the KOMP Repository (www.komp.org). NIH grants to Velocigene at Regeneron Inc (U01HG004085) and the CSD Consortium (U01HG004080) funded the generation of gene-targeted ES cells for 8500 genes in the KOMP Program and archived and distributed by the KOMP Repository at UC Davis and CHORI (U42RR024244). We would like to thank Laurent Delva (INSERM UMR1231) for providing Fes-cre mice, and Lionel Apetoh and Dmitry Bulavin for productive discussions.

Source data

Author contributions

Conceptualization by O.N.D. and A.R.G.; methodology by B.U., A.R.G., E.E., and F.L.; formal analysis by S.J.M.; investigation by B.U., A.R.G., A.A., T.H., E.E., B.B.G., O.N.D., A.V.P., L.T., L.L., J.C., and H.S.; resources by C.G., E.A., O.N.D., F.L., and A.V.P.; writing, reviewing, and editing by O.N.D., E.A., and S.J.M.; supervision by O.N.D, E.A., and E.E; funding acquisition by C.G., O.N.D., and E.A.

Data availability

The p53 ChIP-seq data and linked expression data73,74 were obtained from the human p53 Binding And Expression Resource (BAER) data hub [https://orio.niehs.nih.gov/ucscview/nguyen/p53BAER/p53BAER.html] for the human genome assembly hg19 and are available through the UCSC Genome Browser [https://genome.ucsc.edu]. Source data are provided with this paper. The remaining data are available within the paper, Supplementary Information or available from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Zvi Fridlender, Peiqing Sun, and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Burhan Uyanik, Anastasia R. Goloudina.

Contributor Information

Carmen Garrido, Email: Carmen.Garrido-Fleury@u-bourgogne.fr.

Ettore Appella, Email: appellae@mail.nih.gov.

Oleg N. Demidov, Email: Oleg.Demidov@u-bourgogne.fr

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-23330-6.

References

- 1.Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1267–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.314617.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sambi M, Bagheri L, Szewczuk MR. Current challenges in cancer immunotherapy: multimodal approaches to improve efficacy and patient response rates. J. Oncol. 2019;2019:4508794. doi: 10.1155/2019/4508794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eruslanov EB, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:5466–5480. doi: 10.1172/JCI77053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Nefedova Y, Lei A, Gabrilovich D. Neutrophils and PMN-MDSC: their biological role and interaction with stromal cells. Semin. Immunol. 2018;35:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui, Y. & Guo, G. Immunomodulatory function of the tumor suppressor p53 in host immune response and the tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1942 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Miciak J, Bunz F. Long story short: p53 mediates innate immunity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1865:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munoz-Fontela C, Mandinova A, Aaronson SA, Lee SW. Emerging roles of p53 and other tumour-suppressor genes in immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:741–750. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiscella M, et al. Wip1, a novel human protein phosphatase that is induced in response to ionizing radiation in a p53-dependent manner. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6048–6053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi M, Demidov ON, Anderson CW, Appella E, Mazur SJ. Induction of PPM1D following DNA-damaging treatments through a conserved p53 response element coincides with a shift in the use of transcription initiation sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:7168–7180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulavin DV, et al. Inactivation of the Wip1 phosphatase inhibits mammary tumorigenesis through p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the p16(Ink4a)-p19(Arf) pathway. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ng1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, Nannenga B, Donehower LA. PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1162–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shreeram S, et al. Wip1 phosphatase modulates ATM-dependent signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takekawa M, et al. p53-inducible wip1 phosphatase mediates a negative feedback regulation of p38 MAPK-p53 signaling in response to UV radiation. EMBO J. 2000;19:6517–6526. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellino RC, et al. Medulloblastomas overexpress the p53-inactivating oncogene WIP1/PPM1D. J. Neurooncol. 2008;86:245–256. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauta J, et al. The serine-threonine protein phosphatase PPM1D is frequently activated through amplification in aggressive primary breast tumours. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006;95:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito-Ohara F, et al. PPM1D is a potential target for 17q gain in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1876–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demidov ON, et al. The role of the MKK6/p38 MAPK pathway in Wip1-dependent regulation of ErbB2-driven mammary gland tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:2502–2506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demidov ON, et al. Wip1 phosphatase regulates p53-dependent apoptosis of stem cells and tumorigenesis in the mouse intestine. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nannenga B, et al. Augmented cancer resistance and DNA damage response phenotypes in PPM1D null mice. Mol. Carcinog. 2006;45:594–604. doi: 10.1002/mc.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shreeram S, et al. Regulation of ATM/p53-dependent suppression of myc-induced lymphomas by Wip1 phosphatase. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2793–2799. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen XF, Zhao Y, Jiang JP, Guan WX, Du JF. Phosphatase Wip1 in immunity: an overview and update. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uyanik B, Grigorash BB, Goloudina AR, Demidov ON. DNA damage-induced phosphatase Wip1 in regulation of hematopoiesis, immune system and inflammation. Cell Death Discov. 2017;3:17018. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamada R, Kudoh F, Yoshimura F, Tanino K, Sakaguchi K. Inhibition of Ser/Thr phosphatase PPM1D induces neutrophil differentiation in HL-60 cells. J. Biochem. 2017;162:303–308. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvx032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu G, et al. Phosphatase Wip1 negatively regulates neutrophil development through p38 MAPK-STAT1. Blood. 2013;121:519–529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schito ML, Demidov ON, Saito S, Ashwell JD, Appella E. Wip1 phosphatase-deficient mice exhibit defective T cell maturation due to sustained p53 activation. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4818–4825. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun L, et al. Phosphatase Wip1 is essential for the maturation and homeostasis of medullary thymic epithelial cells in mice. J. Immunol. 2013;191:3210–3220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi W, et al. Phosphatase Wip1 controls antigen-independent B-cell development in a p53-dependent manner. Blood. 2015;126:620–628. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-624114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruark E, et al. Mosaic PPM1D mutations are associated with predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer. Nature. 2013;493:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature11725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleiblova P, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of PPM1D/Wip1 impair the p53-dependent G1 checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:511–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akbari MR, et al. PPM1D mutations in circulating white blood cells and the risk for ovarian cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt323. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artomov M, Rivas MA, Genovese G, Daly MJ. Mosaic mutations in blood DNA sequence are associated with solid tumor cancers. npj Genom. Med. 2017;2:22. doi: 10.1038/s41525-017-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardoso M, Paulo P, Maia S, Teixeira MR. Truncating and missense PPM1D mutations in early-onset and/or familial/hereditary prostate cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55:954–961. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zajkowicz A, et al. Truncating mutations of PPM1D are found in blood DNA samples of lung cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112:1114–1120. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steensma DP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126:9–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogawa S. Genetics of MDS. Blood. 2019;133:1049–1059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-844621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zink F, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis, with and without candidate driver mutations, is common in the elderly. Blood. 2017;130:742–752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu JI, et al. PPM1D mutations drive clonal hematopoiesis in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:700–713 e706. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pharoah, P. D. P. et al. PPM1D mosaic truncating variants in ovarian cancer cases may be treatment-related somatic mutations. J. Natl Cancer Inst.108, djv347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Gibson CJ, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes after autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:1598–1605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayadi A, et al. Mouse large-scale phenotyping initiatives: overview of the European Mouse Disease Clinic (EUMODIC) and of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Project. Mamm. Genome. 2012;23:600–610. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller P, et al. FES-Cre targets phosphatidylinositol glycan class A (PIGA) inactivation to hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:581–589. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visconte V, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of a mouse model of targeted Pig-a deletion in hematopoietic cells. Haematologica. 2010;95:214–223. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivas S, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev. Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi J, et al. Mice deficient for the wild-type p53-induced phosphatase gene (Wip1) exhibit defects in reproductive organs, immune function, and cell cycle control. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:1094–1105. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1094-1105.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertram JS, Janik P. Establishment of a cloned line of Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells adapted to cell culture. Cancer Lett. 1980;11:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(80)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fidler IJ. Biological behavior of malignant melanoma cells correlated to their survival in vivo. Cancer Res. 1975;35:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Z, et al. Wip1 deficiency impairs haematopoietic stem cell function via p53 and mTORC1 pathways. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6808. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goloudina AR, et al. Wip1 promotes RUNX2-dependent apoptosis in p53-negative tumors and protects normal tissues during treatment with anticancer agents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E68–E75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107017108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong ES, et al. p38MAPK controls expression of multiple cell cycle inhibitors and islet proliferation with advancing age. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evrard M, et al. Developmental analysis of bone marrow neutrophils reveals populations specialized in expansion, trafficking, and effector functions. Immunity. 2018;48:364–379.e368. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng LG, Ostuni R, Hidalgo A. Heterogeneity of neutrophils. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:255–265. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zilionis R, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human and mouse lung cancers reveals conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species. Immunity. 2019;50:1317–1334.e1310. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fridlender ZG, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Cancer-related circulating and tumor-associated neutrophils - subtypes, sources and function. FEBS J. 2018;285:4316–4342. doi: 10.1111/febs.14524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilmartin AG, et al. Allosteric Wip1 phosphatase inhibition through flap-subdomain interaction. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:181–187. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giese MA, Hind LE, Huttenlocher A. Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2019;133:2159–2167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-844548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]