Abstract

Introduction

Divergent attitudes towards fever have led to a high level of inconsistency in approaches to its management. In an attempt to overcome this, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the symptomatic management of fever in children have been produced by several healthcare organizations. To date, a comprehensive assessment of the evidence level of the recommendations made in these CPGs has not been carried out.

Methods

Searches were conducted on Pubmed, google scholar, pediatric society websites and guideline databases to locate CPGs from each country (with date coverage from January 1995 to September 2020). Rather than assessing overall guideline quality, the level of evidence for each recommendation was evaluated according to criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM). A GRADE assessment was undertaken to assess the body of evidence related to a single question: the threshold for initiating antipyresis. Methods and results are reported according to the PRISMA statement.

Results

74 guidelines were retrieved. Recommendations for antipyretic threshold, type and dose; ambient temperature; dress/covering; activity; fluids; nutrition; proctoclysis; external applications; complementary/herbal recommendations; media; and age-related treatment differences all varied widely. OCEBM evidence levels for most recommendations were low (Level 3–4) or indeterminable. The GRADE assessment revealed a very low level of evidence for a threshold for antipyresis.

Conclusion

There is no recommendation on which all guidelines agree, and many are inconsistent with the evidence–this is true even for recent guidelines. The threshold question is of fundamental importance and has not yet been answered. Guidelines for the most frequent intervention (antipyresis) remain problematic.

Introduction

Clinical observation has shown that fever is a physiologically controlled elevation of temperature with a strongly regulated upper limit (via protective endogenous antipyretics and inactivity of thermosensitive neurons at temperatures above 42˚C). It rarely reaches 41˚C and does not spiral out of control [1] as is feared by many parents and health professionals [2–4]. Divergent attitudes towards fever have led to a high level of inconsistency in approaches to its management. Many healthcare providers and parents view fever as a dangerous condition or a discomfort to be eliminated [5], despite evidence that fever is an evolutionary resource that aids in overcoming acute infections [6]. Antipyretic treatment can be harmful: in 2006, accidental paracetamol overdose caused 100 deaths in the USA alone [7]. A number of organizations have responded to this situation by developing clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for management of fever in children with goals of guiding antipyretic treatment, responding to discrepancies between evidence and clinical practice, and diminishing irrational fear of fever and overzealous attempts at its suppression. Nevertheless, a published review addressing the quality of seven such CPGs [8] concluded that even guidelines judged as “high quality” are neither comprehensive in content nor in agreement with each other in their recommendations. Whether these conclusions apply to the full spectrum of guidelines for management of fever in children remains uncertain. Therefore, we have summarized all recommendations made by existing fever management CPGs, and assessed the level of evidence for each recommendation. This systematic review was not registered.

Methods

All methods were structured according to the PRISMA statement (S1 Checklist). Relevant medical guideline databases were identified through a google search for ‘medical guideline databases’ and then searched using the following search terms: ((((((children[MeSH Terms]) OR (pediatric[MeSH Terms])) OR (children[Title/Abstract])) OR (pediatric[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((treatment[MeSH Terms]) OR (therapy[MeSH Terms])) OR (management[Title/Abstract])) OR (intervention[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((guideline[MeSH Terms]) OR (principles[MeSH Terms])) OR (guideline[Title/Abstract])) OR (principles[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((((fever[MeSH Terms]) OR (pyrexia[MeSH Terms])) OR (fever[Title/Abstract]))) OR (pyrexia[Title/Abstract])). 1. A search for CPGs (defined as documents on symptomatic fever management in children, issued by governmental organizations, pediatric associations or other healthcare groups) was conducted on the medical databases listed below, as well as websites of the above-mentioned organizations. 2. Google searches incorporating the country name in addition to the original search criteria were then carried out for each of the 195 countries in an attempt to identify any documents that had been missed by the previous methods. 3. A list of national pediatric associations was obtained from the International Pediatric Association’s website (http://ipa-world.org/society.php) and the website of each association was searched for relevant documents using the term “fever” in the language of each. All CPGs, whether intended for healthcare workers or parents,between the dates of 1995 and September 1, 2020 in the 57 languages available on Pubmed, were included. Only the latest CPG of each series was included. Articles that did not focus on the symptomatic management of fever, or were exact copies of other guidelines, were excluded. The process of screening the retrieved documents, as well as eligibility determination and inclusion in the review were carried out by one author.

The following databases were included in the search: PubMed, Google Scholar, National Guideline Clearing House (https://www.guideline.gov/), Canadian Medical Association CPG Infobase (https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/clinical-practice-guidelines.aspx), Danish Health Authority National Clinical Guidelines (https://www.sst.dk/en/national-clinical-guidelines), Haute Autorite de Sante (https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/fc_1249693/en/piliers), German Agency for Quality in Medicine (http://www.leitlinien.de/nvl/), Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement (http://www.cbo.nl/), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (http://www.sign.ac.uk/), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance), Malaysia Ministry of Health (http://www.moh.gov.my/english.php/pages/view/218).

Data

Data from all sources was extracted to an excel table by one reviewer. The table summarized guideline information (country, title, source, date); pharmacologic recommendations (threshold temperature for antipyretic treatment, recommended medications, posology) and non-pharmacologic recommendations (ice/cold/tepid sponge baths, hydration status, nutrition, ambient temperature, dress, covering, compresses, activity level, complementary/herbal recommendations) according to age group (S1 Table).

Quality of evidence assessment

For each recommendation, two authors conducted a search for the highest level of supporting evidence as defined by a modified version of the OCEBM Criteria (Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine) [9]. Systematic reviews of randomized trials provided the highest quality evidence (level 1); systematic reviews of observational and single randomized control trials, the second level of evidence (level 2); individual prospective observational studies and systematic reviews of case reports the third (level 3); individual case reports the fourth (level 4); and mechanistic explanations the fifth (level 5). Our modifications to the OCEBM included assigning systematic reviews of prospective observational studies to Level 2 and systematic reviews of case reports to Level 3, as well as relevant non-human studies of high quality to level 5. We also rated the rigour of systematic reviews using AMSTAR criteria (“A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews”) [10]; if the review met fewer than 7 out of the 11 AMSTAR criteria we rated the quality of evidence down one level (e.g. if a systematic review of randomized trials failed AMSTAR criteria we classified the quality of evidence as level 2 rather than level 1) [10]. Apart from one main question (see below), we did not perform a formal quality assessment of each body of evidence. We created a table categorizing and comparing the CPG statements and the highest level of evidence found in the literature in support of each statement. Two authors independently rated the quality of the evidence and resolved disagreement through discussion.

GRADE assessment of the threshold question

We found conflicting statements and a lack of evidence regarding one fundamental category that affects almost all other recommendations. This concerns the question: “is there a temperature above which antipyresis should be attempted in acute febrile infections in children?”–in short: the threshold question. Since the NICE guidelines [11] have previously been judged to be of high quality [8], and make a recommendation to treat distress rather than body temperature, we thoroughly examined their data for evidence supporting a lack of temperature threshold and determined that the conclusion they came to was unjustified based on the evidence that they provided.

Two authors then independently attempted to address this question using the GRADE method [12]. One author used the search terms: “fever AND temperature threshold AND children AND guideline AND permissive treatment” and identified a pilot RCT trial [13] and 8 papers related to threshold that were surveys and thus deemed ineligible for inclusion in a GRADE analysis. The other author used the terms: ((("acetaminophen"[MeSH Terms] OR "acetaminophen"[All Fields]) OR ("acetaminophen"[MeSH Terms] OR "acetaminophen"[All Fields] OR "paracetamol"[All Fields]) OR antipyresis[All Fields] OR ("ibuprofen"[MeSH Terms] OR "ibuprofen"[All Fields]) OR threshold[All Fields] OR ("antipyretics"[Pharmacological Action] OR "antipyretics"[MeSH Terms] OR "antipyretics"[All Fields] OR "antipyretic"[All Fields])) AND (harm[All Fields] OR benefit[All Fields] OR outcome[All Fields] OR ("mortality"[Subheading] OR "mortality"[All Fields] OR "mortality"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("epidemiology"[Subheading] OR "epidemiology"[All Fields] OR "morbidity"[All Fields] OR "morbidity"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("immune system phenomena"[MeSH Terms] OR ("immune"[All Fields] AND "system"[All Fields] AND "phenomena"[All Fields]) OR "immune system phenomena"[All Fields] OR ("immune"[All Fields] AND "function"[All Fields]) OR "immune function"[All Fields]) OR distress[All Fields])) AND ((peak[All Fields] AND ("body temperature"[MeSH Terms] OR ("body"[All Fields] AND "temperature"[All Fields]) OR "body temperature"[All Fields])) OR ("fever"[MeSH Terms] OR "fever"[All Fields]) OR ("fever"[MeSH Terms] OR "fever"[All Fields] OR "febrile"[All Fields]) OR ("fever"[MeSH Terms] OR "fever"[All Fields] OR ("elevated"[All Fields] AND "temperature"[All Fields]) OR "elevated temperature"[All Fields])) and identified 1704 papers.

Results

Guideline selection

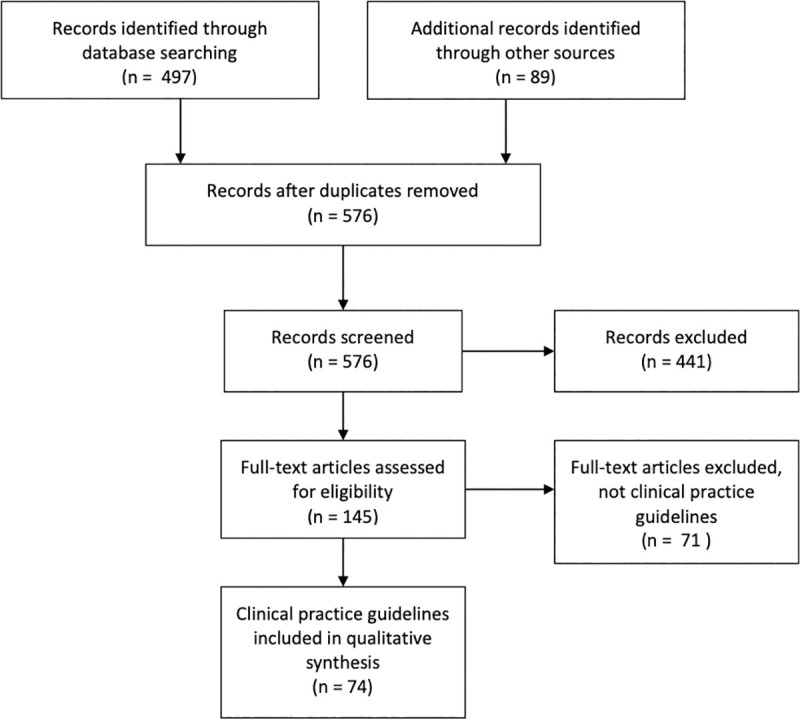

The search procedure identified 586 documents, of which 441 were excluded due to lack of relevance or duplication after screening titles and abstracts. The remaining records (n = 145) were retrieved in full text. After examining the full text version, a further 71 documents were excluded because they were not CPGs.

Finally, 74 guidelines [11, 14–86] were included: three international guidelines as well as the national guidelines for 49 countries (multiple guidelines published by different associations exist in some countries) (S1 Table). Six countries follow the recommendations of another national or international guideline. Therefore, our study represents the fever management recommendations of at least 55 countries.

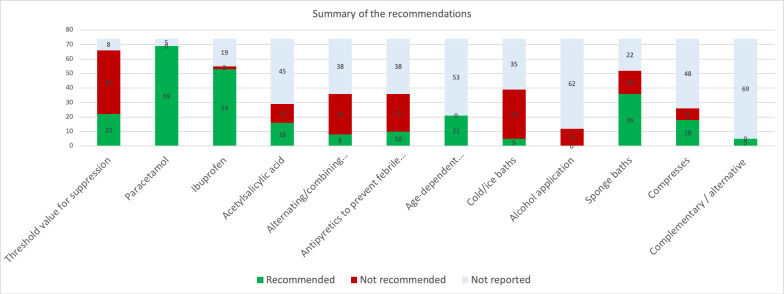

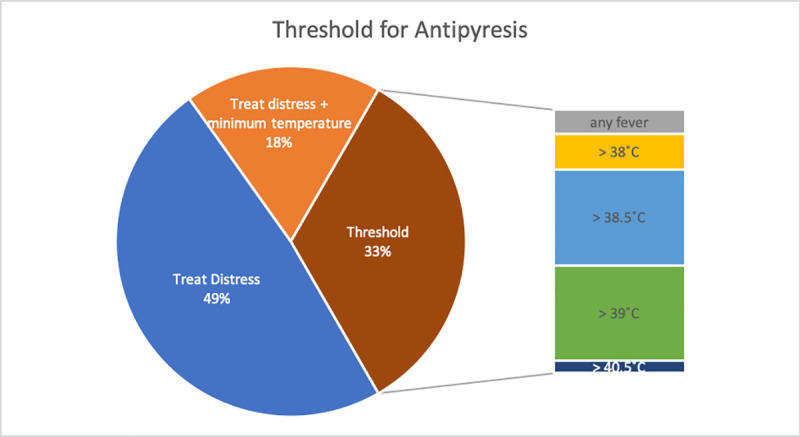

A detailed inventory of the categories and sub-categories of recommendations revealed conflicting advice in all categories. Furthermore, only a few CPGs provided references to substantiate their recommendations. Table 1 and Fig 1–3 summarize the results; for full details, see S1 Table.

Table 1. Recommendations and evidence level.

| Threshold for treating fever | |||

| Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (69) | OCEBM Evidence Level | |

| No: treat distress | 32 | Level 5; physiological reasoning and clinical experience [87] | |

| No: treat distress + minimum temperature | 12 | ||

| Yes | 22 | Level 4; small pilot RCT that 39.5°C is the minimum temperature [13] but no direct published evidence that a threshold is necessary at all | |

| Paracetamol | |||

| General information | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (69) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Recommended | 69 | Level 1; lowers temperature compared to placebo (multiple SRs) [88, 89] | |

| Level 3; relieves discomfort in febrile illness (down-graded because SR only included 3 studies and only 44% of children showed less discomfort compared to ibuprofen 69%); (SR) [88] | |||

| Sole recommended antipyretic | 9 | No published evidence comparing ibuprofen and paracetamol shows a superior effect or safety profile of paracetamol (Review appraisal) [90] | |

| As the 1st line antipyretic | 17 | Level 1; review appraisal [90] SR [89] | |

| As 2nd line antipyretic after ibuprofen/physical methods | 1 | Level 2; RCT, meta-analysis [91] | |

| Dose determination | Follow doctor’s advice | 6 | Level 1; dose by weight and/or age; SR [89] |

| Follow package instructions | 4 | ||

| Dose by age and weight | 3 | ||

| Dose by weight | 8 | ||

| Dosage (mg/kg/dose) | 10 | 2 | Level 3; non-randomized clinical study [92] |

| 10–15 | 14 | Level 1; SR [89] | |

| 15 | 13 | Level 1; SR [93] | |

| 20 | 1 | Level 3 against! (upgraded due to clear causality); case reports showing harm at 20 mg/kg/day over 3–4 days [94] | |

| Dose interval | Give every 4 hours | 7 | No direct published evidence comparing intervals with same dose |

| Give every 4–6 hours | 17 | ||

| Give every 6 hours | 6 | ||

| Level 5 for every six hours [93] | |||

| Give every 6–8 hours | 4 | ||

| Maximum number of doses per day | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (9) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 2 doses | 1 | Level 5; 4 doses/day, regularly every 6 hours to maintain plasma concentration; physiology [93] | |

| 4 doses | 4 | ||

| 5 doses | 3 | ||

| 6 doses | 1 | ||

| Maximum dosage per 24 hours | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (15) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 40 mg/kg/day | 1 | Level 3 for max 60 mg/kg/day; prospective study showing risks over >60 mg/kg/day [95] | |

| 60 mg/kg/day | 9 | ||

| 65 mg/kg/day | 1 | ||

| 80 mg/kg/day | 1 | ||

| Level 4 for 75 mg [96] | |||

| 90 mg/kg/day | 3 | ||

| Maximum duration of treatment | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (10) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 24 hours | 1 | Level 3 for 72 hours [97] | |

| 48 hours | 6 | No published evidence directly comparing duration of treatment | |

| 72 hours | 3 | ||

| Ibuprofen | |||

| General information | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (55) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Recommended | 53 | Level 1 for temperature reduction [88, 91, 98, 99] | |

| Level 2 for relief of discomfort, SR (downgraded because it it only included 3 studies and only 69% of children showed reduced distress) [88] | |||

| Not recommended | 2 | No published evidence supports this | |

| As the 1st line antipyretic | 0 | Level 1 SR [88, 91, 98, 99] | |

| As 2nd line antipyretic after paracetamol | 11 | No published evidence shows as inferior to paracetamol [90] | |

| Caution/avoid in: | Kawasaki disease | 1 | Level 5 pharmacologically sensible [100] |

| Influenza | 1 | Level 5 (SR of animal studies [101] + mention of unpublished data [102]; rewiew [103] | |

| Hemorrhagic fever | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Level 5 against! [104] | |||

| Liver disease | 3 | Level 4, several case reports summarized in review [90, 105, 106] | |

| Chicken pox | 12 | Level 3, 5 observational studies [90, 107] | |

| Allergy/asthma/hypersensitivity | 3 | Level 4, Retrospective [108] | |

| Level 2 against! [90] and SR [109, 110] | |||

| Dehydration | 8 | Level 4, summary of 11 case reports/retrospective [90] | |

| Renal insufficiency | 2 | Level 4, summary of 11 case reports/retrospective [90] | |

| GI disease | 2 | Level 4, summary of 12 case reports and retrospective studies [90] | |

| Bacterial infection | 1 | Level 4, retrospective study, case control [111–114] | |

| Complex medical conditions | 2 | No direct published evidence | |

| Dose determination/instructions | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (32) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Take with food | 1 | Level 5 against! [115] | |

| Follow doctor’s advice | 6 | No direct published evidence | |

| Follow package instructions | 4 | ||

| Dose by weight | 4 | ||

| Dosage (mg/kg/dose) | 5–10 mg/kg /dose | 3 | Level 2, RCT [116] |

| 7–10 mg/kg/dose | 1 | Level 2, RCT [117] | |

| 10mg/kg/dose | 8 | Level 2, RCT [118] | |

| 10-15mg/kg/dose | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Interval between doses | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (17) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 6 hours | 5 | No direct published evidence comparing | |

| 6–8 hours | 11 | ||

| 8 hours | 1 | ||

| Maximum number of doses per day | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (10) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 2 doses | 1 | No direct published evidence comparing | |

| 3 doses | 3 | ||

| 4 doses | 6 | ||

| Maximum dosage per 24 hours (mg/kg/day) | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (10) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| 20–30 | 2 | No direct published evidence comparing | |

| 30 | 2 | ||

| 40 | 4 | ||

| 45 | 1 | ||

| 1200 mg/day | 1 | ||

| Maximum duration of treatment | 72 hours | 3 | No direct published evidence |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | |||

| General | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (29) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Not recommended <18 years | 16 | Level 4, based on epidemiological association with Reyes syndrome, aspirin should not be used to treat acute febrile viral illness in children [119] | |

| Recommended/possible | 13 | ||

| Minimum age | >5 years | 1 | No direct published evidence stating exactly which age aspirin is safe |

| >10 years | 1 | ||

| >12 years | 2 | ||

| >14 years if they have already had varicella | 1 | ||

| >15 years | 1 | ||

| >16 years | 2 | ||

| Dosage | 60 mg/kg/day | 1 | No direct published evidence |

| 1g/3 times per day | 1 | ||

| Avoid in | Chicken pox | 2 | Level 4, case report [120] |

| Hemorrhagic disorders | 1 | Level 5, due to effect on platelets and bleeding diathesis [121] | |

| Other antipyretics | |||

| Ketoprofen | Recommended | 4 | Level 2, RCT [122, 123], |

| Follow doctor’s advice | 1 | Level 2, RCT for 0.5 mg/kg/dose [122] | |

| 2mg/kg/day in 4 doses | 3 | ||

| Diclofenac | Recommended 2nd line | 1 | Level 3, RCT [124, 125] |

| Every 12 hours | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Mefenamic acid | Recommended | 3 | Level 3, RCT [126] |

| Not recommended | 1 | Level 4 [127] | |

| Follow doctor’s advice | 1 | No published evidence | |

| 6–7 mg/kg/dose max 3 times per day | 2 | Level 3, RCT [126] | |

| Metamizole | Recommended | 2 | Level 3, RCTs downgraded [128, 129] |

| Not recommended | 3 | Level 3, Single blind clinical trial [130] | |

| Prescription only | 1 | No published evidence | |

| 10–15 mg/kg, every 6–8 hours | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Naproxen sodium | Recommended | 1 | Level 3, RCT [131] |

| Not recommended | 1 | No published evidence | |

| 220 mg every 8–12 hours (>12 years) | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Alternating/combining antipyretics | |||

| Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (39) | OCEBM Evidence Level | |

| Not recommended | 28 | Level 1, SR [132–134] | |

| Alternate and/or combine if necessary | 8 | No published evidence that makes this conclusion; Level 4 against! Retrospective analysis [135] found 4 times more likely to suffer acute kidney injury | |

| Insufficient evidence to make recommendation | 1 | Level 1, Cochrane review [136] | |

| Switching to other drug if 1st line drug fails | 3 | No published evidence showing a benefit to this | |

| Prevention of febrile seizures | |||

| Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (37) | OCEBM Evidence Level | |

| Antipyretics not recommended for prevention | 26 | Level 1, SR [137–139] RCT | |

| Evidence is inconclusive | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Recommended for prevention | 10 | Level 3, Prospective study [140] | |

| Age dependent treatment recommendations | |||

| General | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (21) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| <2 months | Extend interval between paracetamol doses to 6–8 hours | 1 | Level 5, review of pharmacokinetics/dynamics [141] |

| No paracetamol < 2 months | 2 | No direct published evidence | |

| No paracetamol <6 weeks | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Only paracetamol is recommended for neonates | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Paracetamol not recommended for neonates | 4 | No direct published evidence | |

| Neonatal dosage 10mg/kg/dose 3–4 times per day | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Neonatal dosage 7.5 mg/kg/dose max 30 mg/kg/day | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Premature infants <32 weeks 15mg/kg/dose, 8–12 hours, 2 doses per day | 1 | Level 5 [141] | |

| 32–36 weeks 15mg/kg/dose, 6–8 hours,3 doses per day | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| >37 weeks 15mg/kg/dose, 4–6 hours, 4 times per day | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| <4 months | Paracetamol recommended from 3 months | 3 | No direct published evidence |

| Follow doctor’s advice when child is less than 3 months | 1 | ||

| Follow doctor’s advice when child is less than 4 months | 1 | ||

| Avoid ibuprofen <3 months | 4 | ||

| Maximum dose paracetamol <3 months 60mg/kg/day | 1 | ||

| Maximum dose paracetamol >3 months 80mg/kg/day | 1 | ||

| <6 months | Avoid ibuprofen <6 months | 11 | Level 4 review of evidence [142]; can be used safely age 3–6 months, dosage 5–10 mg/kg |

| Ibuprofen has more side effects in children <6 months | 1 | ||

| Ibuprofen 5mg/kg/dose | 1 | ||

| Follow doctor’s advice when child is less than 6 months | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Avoid mefenamic acid if child is less than 6 months | 2 | ||

| Avoid ketoprufen if child is less than 6 months | 2 | ||

| <1 year | Ibuprofen should be avoided if child is less than 1 year | 1 | No direct published evidence supports this; safe from 3rd month [142] |

| Diclofenac should be avoided if child is less than 1 year | 1 | ||

| Avoid compresses in children less than 1 year | 1 | ||

| >10 years | Paracetamol dose is 500mg-1g every 6–8 hours, max 4g per day | 1 | No direct published evidence |

| >12 years | Nimesulide is an option | 1 | Level 2, SR [143] suggests it is possible >6 months |

| Nurofen is an option | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Naproxen sodium is an option | 1 | No published evidence | |

| Physical methods | |||

| Cool/ice bath | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (39) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Not recommended | 34 | Level 2 (for temporary antipyretic effect but unphysiological) RCT [144]; Level 2, RCT [144] causes discomfort | |

| Recommended | 5 | No published evidence | |

| Alcohol rubs | Not recommended | 12 | Level 1, dramatic effect case reports [145–149] |

| Lukewarm baths | Recommended | 4 | See tepid sponge baths |

| Physical measures should be 1st line | Recommended | 1 | No published evidence |

| Tepid sponging | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (49) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Not recommended | 16 | Level 1, SR [150, 151] | |

| Recommended | 33 | No direct published evidence | |

| Instructions for sponge baths | Water temperature 37˚C and progressively cool | 1 | No direct published evidence; RCT showed that adding sponging to antipyretic not effective [152] |

| Water temperature 27–35˚C | 1 | ||

| Sponge bath 30min after taking antipyretic | 4 | ||

| Add peppermint oil to bath | 1 | ||

| Alternative in case of allergy to antipyretic | 1 | ||

| max. duration: 30 min | 1 | ||

| Compresses | Number of guidelines reporting | 26 | No direct published evidence |

| Not recommended | 8 | ||

| Recommended | 18 | ||

| Use if antipyretic fails | 2 | ||

| Use after antipyretic | 2 | ||

| Head/face | 5 | ||

| Neck | 1 | ||

| Arms | 1 | ||

| Calves | 6 | ||

| Armpits & groin | 1 | ||

| Avoid if extremities are cold | 1 | ||

| Apply for 20 min and repeat | 1 | ||

| Ice packs over large vessel areas | 1 | ||

| Fluid intake | |||

| Encourage increased fluid intake | Number of guidelines reporting | 56 | Level 3, SR [153] exercise care |

| Type of fluids | Cool drinks | 2 | No direct published evidence |

| Water | 10 | ||

| Fruit juice | 4 | ||

| Dilute fruit juice | 5 | ||

| Breast milk | 3 | ||

| Formula | 1 | ||

| Vegetable stock | 1 | ||

| Electrolyte solution | 1 | ||

| Jello | 1 | ||

| Rice water | 1 | ||

| Coconut milk | 1 | ||

| Fizzy/soft drinks | 2 | ||

| Popsicles | 3 | ||

| Tea | 3 | ||

| Cows milk | 2 | ||

| Cordial | 1 | ||

| Amount | 50-80ml/kg | 1 | No direct published evidence |

| 10cc/kg/˚C rise in temperature | 1 | ||

| Nutrition | |||

| Instructions | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (13) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Normal if child doesn’t want to eat; don’t force | 9 | No direct published evidence | |

| Feed the child if hungry | 1 | ||

| Light, low-fat diet | 2 | ||

| Offer child’s regular foods | 2 | ||

| Offer favourite food | 1 | ||

| Eat small amounts frequently | 1 | ||

| Type of foods recommended | Salty soup | 4 | |

| Fresh fruit | 2 | ||

| Popsicles | 2 | ||

| Gelatine | 2 | ||

| Low fat biscuits | 1 | ||

| Noodles | 1 | ||

| Porridge | 1 | ||

| Environment | |||

| Ambient Temperature | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (24) | OCEBM Evidence Level |

| Warm room | 3 | No direct published evidence | |

| 21–23˚C | 1 | ||

| 20–22 ˚C | 1 | ||

| 20–21˚C | 1 | ||

| Normal/child preference | 4 | ||

| Not too warm | 2 | ||

| Cool | 12 | ||

| Fan/ventilated room | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (19) | No direct published evidence |

| No fanning or ventilation | 2 | ||

| Fan/ventilation recommended | 15 | ||

| No drafts | 1 | ||

| Fan over liquid to increase heat loss | 1 | ||

| Fan if room is stuffy | 1 | ||

| According to comfort of child | 2 | ||

| Possible, but inconclusive research | 1 | ||

| Dress of the child | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (48) | Level 5, physiological; dress appropriately for fever phase [154] |

| Remove excess clothing | 5 | ||

| Dress in light weight clothing | 23 | ||

| Undress/underwear | 10 | ||

| Dress according to child’s comfort | 5 | ||

| Don’t overdress | 2 | ||

| Don’t underdress | 2 | ||

| Dress normally | 1 | ||

| Cover /uncover | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (30) | Level 5; cover according to phase of fever [154] RCT on uncovering [155] vs. paracetamol and sponging that showed very little benefit to unwrapping |

| Cover lightly | 13 | ||

| Cover if cold, uncover if hot, according to child’s comfort | 11 | ||

| Don’t overbundle | 2 | ||

| Cover during phase of temerature rise and remove later | 1 | ||

| Change sheets frequently | 1 | ||

| Uncover | 4 | ||

| Activity Level | Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (14) | Level 3, clinical trial: bed rest not necessary) [156] |

| Promote rest | 7 | ||

| Follow child’s wishes | 3 | ||

| Bed rest is not necessary | 4 | ||

| Stay at home | 3 | ||

| Complementary/alternative recommendations | |||

| Recommendation/Statement | Number of guidelines reporting (5) | Level 3, prospective cohort study [157]; RCT [158] | |

| Anconitum (homeopathy) | 2 | ||

| Belladonna (homeopathy) | 2 | ||

| Ferrum phosphoricum (homeopathy) | 2 | ||

| Chamomile (homeopathy) | 1 | ||

| Mixtures (homeopathy) | 1 | ||

| Enema | 1 | Level 4 [159, 160] case study | |

| Stomach lavage | 1 | No direct published evidence | |

| Vinegar mustard rub | 1 | ||

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Selection of guidelines.

Fig 3. Summary of recommendations.

Y-axis: numbers of guidelines reporting.

Fig 2. Threshold for antipyresis.

Temperatures indicate the height of the given threshold.

GRADE assessment

The search identified several articles addressing the impact of fever management on disease outcome in ICU patients. However, upon closer examination these studies either included a threshold value for rescue therapy and/or specifically excluded children [161]. With the exception of two studies [162, 163] (Table 2), even the placebo arms of antipyretic RCTs operated with a threshold rescue value; and neither study reported outcomes related to temperature and morbidity/mortality. It is likely that permissive management of fever did not result in negative outcomes because this would have been reported but as the outcomes were not measured, the studies could not be included.

Table 2. GRADE analysis: Evidence tables.

| No. of Studies | Intervention | Effect | Quality | Design | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Pub. Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of antipyresis on morbidity/mortality in children with acute febrile infections | ||||||||||

| 1 Dallimore et al., 2018 | Antipyresis (drug or physical) | No Tx or rescue therapy (most studies 39.5 ˚C) | RR 1.01 95% [CI], 0.81–1.28; P = 0.95 | VERY LOW | SR of 13 RCT | Yes (-1) Several trials had method. weaknesses | None | Yes (-1) Population excluded children | Yes (-1) Wide CI estimates | None |

| 1 Peters et. al., 2019 | Antipyretic drug treatment | No Tx or rescue therapy (up to 39.5 ˚C) | Not measured as a primary outcome “rates were similar” | VERY LOW | RCT | Yes (-2) Small sample size, outcomes not quantified | None | Yes (-1) Only children on ventilation assistance were included | None | None |

Tx = Expected treatment, RR = relative risk, CI = Confidence intervall, P = p-value, ˚C = degree celsius, SR = systematic reviews, RCT = randomized controlled trials

Discussion

Main findings

A comparison of worldwide fever management guidelines, revealed striking discrepancies with each other and with scientific literature on all parameters. The heterogeneity of the recommendations and the low quality of evidence on which they are based, point to a need for better data. Our findings are in line with the previous work of other authors and demonstrate, that many discordant suggestions in guidelines at national or international could be improved [8], in particular, our review stated this fact for recommendations for the use of antipyretis, relevant temperature parameters and treatments. In contrast to previous studies of CPGs, which showed what improvements are needed in terms of methodology, the applicability and the editorial independence domains [8], our review complements the previous work by the result of low or indeterminable evidence levels for recommendations and a very low level of evidence for the threshold for antipyresis. Through summarizing and assessing the available evidence, we provide an extensive basis for the development of a consensus and evidence based, interdisciplinary fever guideline.

Temperature threshold for antipyresis: Evidence vs. clinical practice

The majority of CPGs recommend against treatment of fever itself, regardless of temperature. In the guidelines that give a threshold for antipyresis, there is little agreement about the temperature, with values ranging from 37.5˚C to 40.5˚C and no rationale provided. Our GRADE assessment suggests–with a very low quality of evidence–that there is no need for a threshold for antipyresis below 39.5 ˚C because that was the maximum threshold used in the studies [13, 161]. Whether a threshold is necessary remains unclear because there are no adequate studies. Despite the majority of guidelines recommending against giving antipyretics based on body temperature, studies of health care workers have shown that most believe that the risk of heat-related adverse outcomes is increased with temperatures above 40°C (104°F) and that more than 90% of doctors prescribe antipyretic therapy at temperatures >39˚C [164, 165]. Even in the UK, a country with longstanding guidelines that recommend only treating distress, a large study of pediatric ICUs has shown that the threshold for treatment of fever is still 38˚C and that 58% of care-givers asked, considered a fever of 39˚C unacceptable [166].

Pharmacologic treatment: Choice of drug, dosing, adverse effects

Paracetamol is the only medication recommended by all guidelines and 17 give it preference over ibuprofen. Although high quality evidence (Level 1) has shown that they are both effective in lowering temperature, the evidence for effectiveness in distress reduction (the more relevant outcome) is lower (Level 3). There is no justification for paracetamol being the sole, or debatably, even the first-choice antipyretic as no systematic review or RCT comparing it with ibuprofen has shown a superior effect or safety profile. 15 out of 30 RCTs comparing paracetamol and ibuprofen concluded that ibuprofen is superior in effect while the remainder found no significant difference in either effect or safety profiles [90]. This raises the question as to whether paracetamol should be relegated to second-line [91, 167] because while the safety profiles of both drugs are equivalent at therapeutic doses, the toxic level of paracetamol is reached much sooner and causes more deaths than supratherapeutic doses of ibuprofen [7, 168]. Adverse effects caused by ibuprofen generally resolve, although there have been deaths due to triggering of asthma as well as long-term complications from toxic epidermal and soft tissue necrolysis [90]. Also, despite high level evidence [132–134] that combining/alternating antipyretics leads to little additional benefit in temperature control, is associated with a higher risk of supratherapeutic dosing and has not been shown to reduce discomfort, the rate of alternating antipyretics in medical practice is 67% [169]. Given that parents misdose antipyretics in almost half of cases with 15% using supratherapeutic doses [170], arriving at a consensus regarding medication choice and dose, along with methods of communicating this to parents would be a valuable contribution towards standardization of fever management. For a full discussion of dosage recommendations, see e-Supplement.

Antipyretics for prevention of febrile seizures: No evidence

Several systematic reviews and RCTs have shown that antipyretics are ineffective in preventing febrile seizures (Level 1 [137–139]). Interestingly, one trial found that antipyretics are ineffective in lowering the temperature at all during febrile episodes that are associated with febrile seizure [138]. However, a recent study concluded that rectal paracetamol administration significantly decreased the likelihood of recurrent febrile seizures during the same fever episode [140].

Nonpharmacologic measures: Fluid intake, bath, rubs and compressions

Many guidelines recommend an adequate/increased intake of fluids in order to avoid dehydration. Caution should be observed in universally recommending increased fluids as it may cause harm [153]. No direct published evidence was found regarding the optimal amount or type of fluid intake during fever. Proctoclysis is only mentioned in one guideline though the literature suggests that it could be helpful in maintaining hydration status (Level 4), resulting in increased well-being and fewer hospitalizations [159, 160, 171–178]. Nutrition is mentioned in 25% of the guidelines with a majority in agreement that children should not be forced to eat during fever. We did not identify any studies on this.

In terms of other physical recommendations, several seemingly opinion based, contradictory approaches are mentioned: cool to warm room temperatures, ventilated to unventilated rooms, bundling to undressing the child completely, and bedrest to normal activity. A systematic review that attempted to analyze these factors [150] found that there were no studies investigating physiological interventions or environmental cooling measures as separate interventions.

Given the lack of evidence, one may appeal to knowledge of the fever process to determine that appropriate use of physical measures depends on the fever phase: As the fever is rising, the child should be kept warm or even actively warmed–thus reducing the energy needed to develop fever and thereby discomfort. Once the child is warm all the way to its feet and starts sweating, layers of sheets and clothing can be carefully removed (level 5 [154]).

Despite high level evidence (level 1) that tepid sponging increases discomfort and should be avoided [150, 151], 61% of guidelines are still in favor of its use. Recommendations about compresses show a similar distribution (63% in favor) though fewer guidelines address the topic and little directly applicable research is available. The decrease in temperature that results from external cooling is of short duration. A mismatch between the hypothalamic set point and skin temperature leads to peripheral vasoconstriction and metabolic heat production, which results in shivering and increased discomfort of the child. The initial small reduction in body temperature may not be worth the potential discomfort and the use of these methods indicates a continued focus on the reduction of body temperature rather than distress.

Complementary recommendations

Recommendations on complementary treatments only appear in three guidelines, despite their widespread use by parents and health professionals. The evidence for the proposed treatments is low (Level 4)–perhaps partially because most forms of alternative medicine do not advocate fever suppression as a treatment goal. With regard to well-being, the scientific literature suggests greater or equal efficacy and satisfaction compared with conventional treatments, with high safety and tolerability [157, 158, 179–181].

Other potential issues not yet included in the published guidelines

Digital media: None of the guidelines mention screen exposure. Most countries are beginning to formulate recommendations on child screen exposure [182]. We point to the need for recommendations on screen use in illness.

Parental care by interaction and empathy and relationship: None of the guidelines mention the quality of parental care during illness, which may be the most important factor for both immediate well-being and long-term health [183]. Finding ways to reduce fever phobia by education or counseling intervention may contribute to relational and empathetic fever management and facilitate a significant reduction of distress [184, 185].

Limitations and strengths

Only 74 guidelines were retrieved which, considering the high frequency of fever, is fewer than expected. We cannot exclude that other documents exist as some may not be online and our attempts to contact these countries’ pediatric societies per email did not yield any additional documents. Out of a responsibility for resource investment, we refrained from duplicate assessment of guideline eligibility, risk of bias for the individual intervention and duplicate data extraction (except for the GRADE assessment, which was duplicate), judging that minor changes would have no effect on the overall guideline assessment results. Due to a lack of information regarding the developmental procedure of most guidelines, an overall assessment of quality (using AGREE II) was not feasible. Therefore, we chose to examine the supporting evidence for each of the recommendations using the OCEBM criteria [9] and discuss the results based on the highest level of evidence. This is a unique strength of this review.

Conclusion

A comparison of worldwide fever management guidelines, revealed some uniform themes and recommendations supported by a high level of evidence, but also striking discrepancies and a low level of evidence supporting most recommendations. So far, we can conclude that some recommendations should be part of all guidelines:

Parents and carers should be educated about the benefits of fever, and how to recognize and act on othersigns of danger and judge the condition rather than fever alone.

In an otherwise healthy child with an acute febrile infection, treatment should focus on reduction of distress rather than temperature (Level 5). The social and physical environment should be optimized before considering use of antipyretic medications (Level 5).

Antipyretics should not be combined (Level 1), or routinely alternated (Level 1), and be used, if at all, only as long as the child appears distressed (Level 5).

Antipyretics should not be given with the intention of preventing febrile seizures (Level 1)

External cooling may increase discomfort and metabolic strain (Level 1).

None of the CPGs include statements about the potential benefits of fever (level 1). Studies are needed to assess whether educating parents and carers (i.e. about the side effects of antipyretics, the positive immunological effects of fever and how to recognize signs of danger) influences outcomes. The question as to whether or not there should be a threshold for initiating antipyresis must be met with solid evidence.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

Jana Wachmeister, M.Sc., is thanked for systematic literature searches and data curation.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Funding number: 01GY1731 and 01GY1905), the Software AG – Foundation and the University of Witten/Herdecke.

References

- 1.DuBOIS EF. Why are fever temperatures over 106 degrees F. rare? Am J Med Sci. 1949;217: 361–368. doi: 10.1097/00000441-194904000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karwowska A, Nijssen-Jordan C, Johnson D, Davies HD. Parental and health care provider understanding of childhood fever: a Canadian perspective. CJEM. 2002;4: 394–400. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500007892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years? Pediatrics. 2001;107: 1241–1246. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkon-Tamir E, Rimon A, Scolnik D, Glatstein M. Fever Phobia as a Reason for Pediatric Emergency Department Visits: Does the Primary Care Physician Make a Difference? Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2017;8. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purssell E, Collin J. Fever phobia: The impact of time and mortality—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;56: 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duff GW. Is fever beneficial to the host: a clinical perspective. Yale J Biol Med. 1986;59: 125–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nourjah P, Ahmad SR, Karwoski C, Willy M. Estimates of acetaminophen (Paracetomal)-associated overdoses in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15: 398–405. doi: 10.1002/pds.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiappini E, Bortone B, Galli L, de Martino M. Guidelines for the symptomatic management of fever in children: systematic review of the literature and quality appraisal with AGREE II. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e015404. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. In: Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Internet]. 1 May 2016. [cited 13 Sep 2018]. Available: https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358: j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. 2017. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336: 924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters MJ, Woolfall K, Khan I, Deja E, Mouncey PR, Wulff J, et al. Permissive versus restrictive temperature thresholds in critically ill children with fever and infection: a multicentre randomized clinical pilot trial. Crit Care. 2019;23: 69. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2354-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.When the baby has a fever. In: Naver Blog | Yonsei Bärenpädiatrie; [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://blog.naver.com/gomdori4585/221229492288 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Public Health, General Directorate of Pharmaceutical Affairs. National Standard Treatment Guidelines for the Primary Level. 2013. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21744en/s21744en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.L’association des pédiatres libéraux d’Alger (APLA). Childhood fever: what to do? In: apla; [Internet]. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.apla-dz.org/conseils-aux-parents/maladies-infantiles/votre-enfant-a-de-la-fievre/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAP. Argentine Society of Pediatrics | News | Fever. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: http://www.sap.org.ar/

- 18.What to do and what is forbidden if the baby has a fever [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: http://arabkirjmc.am/baby-high-temperature/

- 19.NSW Department of Health. Children and Infants with Fever—Acute Management. 2010. Available: http://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2010_063.pdf

- 20.Fever Without Source—Kids Health WA (PMH ED Guidelines). In: Kids Health WA (PMH ED Guidelines) [Internet]. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://kidshealthwa.com/guidelines/fever-without-source/

- 21.South Australian Child Health Clinical Network. Management of Fever without Focus in Children (excluding neonates), Clinical Guideline. 2013. Available: http://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/812ad70040d041b4972cbf40b897efc8/Fever+without+Focus_Apr2015.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=812ad70040d041b4972cbf40b897efc8

- 22.Clinical Practice Guidelines: Febrile child. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Febrile_child/

- 23.Joana Briggs Institute. Management of the Child with Fever. 2004. Available: http://www.babyhintsandtips.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/feverhandout.pdf

- 24.Österreichische Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendheilkunde. Fieber und Schmerzen: Was tun? Available: http://www.paediatrie.at/home/Spezialbereiche/Infektiologie/fieber_und_schmerzen_bei_kindern_was_tun.php

- 25.Fever In Children. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.pediatrie.be/fr/xi-la-fievre-chez-l_enfant/251/2

- 26.Arteaga Bonilla R. Fever and the use of antipyretics in children. Revista de la Sociedad Boliviana de Pediatría. 2011;50: 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fever: Beware of fever phobia. SBP [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.sbp.com.br/especiais/pediatria-para-familias/cuidados-com-a-saude/febre-cuidado-com-a-febrefobia/

- 28.The College of Family Physicians Canada. Fever in Infants and Children. 2011 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.cfpc.ca/ProjectAssets/Templates/Resource.aspx?id=3596

- 29.What you need to know: fever. [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.cheo.on.ca/en/resources-and-support/resources/P5325E.pdf

- 30.Government of Manitoba. Healthy Child, Caring for a Child with Fever. 2006. Available: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/documents/fever.pdf

- 31.Canada Pharmacist’s Association. Fever. 2010. Available: http://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/file/store/PSC-Fever.pdf

- 32.Canadian Pediatric Society. Fever and temperature taking—Caring for Kids. 2015 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/fever_and_temperature_taking

- 33.SOCHIPE—Soc. Chilena de Pediatría. Fever: Outpatient Treatment. 2013 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.sochipe.cl/v3/presenta_dos.php?id=610

- 34.Colombian Society of Pediatrics | SCP Colombian Society of Pediatrics. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://scp.com.co/

- 35.Fever in the child. In: ACOPE C.R. [Internet]. 11 Apr 2018 [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://acopecr.com/fiebre-en-el-nino/

- 36.Nurse performance at a fever in children. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.revista-portalesmedicos.com/revista-medica/actuacion-enfermera-cuadro-febril/

- 37.Fever and fever phobia Cyprus Pediatric Society. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.child.org.cy/phobia-of-fever/

- 38.When the child has a fever. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 2008;46: 17–21. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2008.03.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asociación de Pediatría de El Salvador. What you need to know about your child’s fever. In: Asopedes; [Internet]. 24 Sep 2015. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://asopedes.org/lo-que-debe-saber-sobre-la-fiebre-de-su-hijo/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haute Autorite de Sante. Management of fever in children. 2016. Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-03/dir5/guidance_leaflet_management_of_fever_in_children.pdf

- 41.Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé (Afssaps). Update on the management of fever in children. Available: http://ansm.sante.fr/var/ansm_site/storage/original/application/8a3e72e8fec9c0f68797a73832372321.pdf

- 42.Société Française de Pédiatrie. Symptomatic Management of Young Childhood Fever. 2004 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.sfpediatrie.com/recommandation/prise-en-charge-symptomatique-de-la-fi%C3%A8vre-du-jeune-enfant

- 43.Der Berufsverband der Kinder- und Jugendärzte. Fever. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.kinderaerzte-im-netz.de/erste-hilfe/sofortmassnahmen/fieber

- 44.Fever in children patient guideline. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.patientenleitlinien.de/Fieber_Kindesalter/fieber_kindesalter.html

- 45.Niehues T. The febrile child: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110: 764–773; quiz 774. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parents info fever. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.dgkj.de/eltern/dgkj-elterninformationen/elterninfo-fieber

- 47.Ministry of Health, Republic of Ghana. Standard Treatment Guidelines:—Ch 19 Fever. 2010. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s18015en/s18015en.pdf

- 48.Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) | Search. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://iapindia.org/search.php

- 49.Jehangir Apollo hospital. Fever in children. 2013. Available: http://www.jehangirhospital.com/blog/item/2-fever-in-children

- 50.Handling Fever in Children. In: IDAI [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.idai.or.id/artikel/klinik/keluhan-anak/penanganan-demam-pada-anak

- 51.Irish College of General Practitioners. Antipyretic Prescribing 2013. 2013 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item/6686EC55-D046-1DCB-B9ED227FA2C07DA6

- 52.Chiappini E, Venturini E, Remaschi G, Principi N, Longhi R, Tovo P-A, et al. 2016 Update of the Italian Pediatric Society Guidelines for Management of Fever in Children. J Pediatr. 2017;180: 177–183.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kodomo QQ Kids Emergency (ONLINE-QQ)—Go to the hospital by car/taxi. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: http://kodomo-qq.jp/en/?pname=hatsunetsu%2Fr2

- 54.Jordan Pediatric Society. Fever in children. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://jps.org.jo/

- 55.Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya.: 356.

- 56.Al Salam Hospital. Fever and Its Treatment. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.sih-kw.com/Fever_En.cms?ActiveID=1132

- 57.Ministère-Direction de la Santé. Fièvre. 2005 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.sante.public.lu/fr/maladies/zone-corps/sang/fievre/index.html

- 58.La fièvre chez les enfants | Kannerklinik. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://kannerklinik.chl.lu/fr/dossier/la-fievre-chez-les-enfants

- 59.Dutch College of General Practitioners. Children with Fever (Page 25). 2016. Available: https://assortiment.bsl.nl/files/e27c6c2f-8fa3-4f91-9c60-39597b8ecf7d/voorbeeldhoofdstuk.pdf

- 60.NVK—Document. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.nvk.nl/themas/kwaliteit/overige-kennisdocumenten/document?documentregistrationid=8257539

- 61.Starship Children’s Hospital of New Zealand. Fever Investigation and Management. 2009 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.starship.org.nz/for-health-professionals/starship-clinical-guidelines/f/fever-investigation-and-management/

- 62.Fever in children. In: Ministry of Health NZ [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/conditions-and-treatments/diseases-and-illnesses/fever/fever-children

- 63.The Norwegian Medical Association. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.legeforeningen.no/

- 64.Png Paediatric Society. Standard Treatment forCommon Illnesses of Children in Papua New Guinea (Page 61). 2016. Available: http://pngpaediatricsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/PNG-Standard-Treatment-Book-10th-edition-2016.pdf

- 65.Isolated fever. In: Issuu [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://issuu.com/protocoale_pediatrie/docs/45_febra_izolata

- 66.Union of Pediatricians of Russia. In: Union of Pediatricians of Russia [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.pediatr-russia.ru/parents_information/soveti-roditelyam/likhoradka.php

- 67.Fever: What is it, medication, other measures and when to consult a doctor. | KKH. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.kkh.com.sg/patient-care/conditions-treatments/fever-childhood-illnesses

- 68.Green R, Jeena P, Kotze S, Lewis H, Webb D, Wells M, et al. Management of acute fever in children: guideline for community healthcare providers and pharmacists. S Afr Med J. 2013;103: 948–954. doi: 10.7196/samj.7207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fever: what to do when the child has a fever? In: EnFamilia. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://enfamilia.aeped.es/temas-salud/que-hacer-cuando-nino-tiene-fiebre

- 70.Sri lanka college of paediatrician. 2019 Standard Treatment Protocols—PAEDIATRICS. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://slcp.lk/

- 71.Ministry Of Health Government Of Southern Sudan. Prevention & Treatment Guidelines for Primary Healthcare Centers and Hospitals. 2006. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21010en/s21010en.pdf

- 72.Fever in children [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.1177.se/Other-languages/Engelska/Barn/Feber—vad-kan-man-gora-sjalv/

- 73.Swiss Pediatrics Association. When children are ill: some advice for parents. 1995. Available: http://www.swiss-paediatrics.org/sites/default/files/parents/10-16_ans/maladie/pdf/2012.12.31_ryan_kate_e_homepage.pdf

- 74.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Standard Treatment Guidelines and Essential Medicines List. 2013. Available: http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/country_lists/Tanzania_STG_052013.pdf

- 75.Ministry of Health Tuvalu. Standard Treatment Guidelines. 2010. Available: https://srhr.org/abortion-policies/documents/countries/02-Tuvalu-Standard-Treatment-Guidelines-2010.pdf

- 76.Asssociation of Ukranian Pediatricians. Fever and Hyperperexia In Children. Available: http://www.uf.ua/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Georgiyants_Lyhomanka_giperpireksiya_dity_ENG_R_verstka_c.pdf

- 77.Mayo Clinic. Fever: First aid. 2015 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/first-aid/first-aid-fever/basics/ART-20056685?p=1

- 78.American Academy of Pediatrics. Fever. In: HealthyChildren.org [Internet]. 2016 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/fever/Pages/default.aspx

- 79.UpToDate. Fever in children (Beyond the Basics). 2017. Available: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/fever-in-children-beyond-the-basics

- 80.PubMed Health. Fever in children: How can you reduce a fever? 2016 [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072637/

- 81.Sullivan J E. Fever and Antipyretic Use in Children | From the American Academy of Pediatrics | Pediatrics. 2011. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/3/580 doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fever in Infants and Children—Pediatrics. In: MSD Manual Professional Edition [Internet]. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/symptoms-in-infants-and-children/fever-in-infants-and-children

- 83.SVPP. [cited 24 Sep 2020]. Available: http://www.svpediatria.org/

- 84.Medecins Sans Frontieres. Clinical Guidelines: Diagnosis and Treatment Manual. 2016. Available: http://refbooks.msf.org/msf_docs/en/clinical_guide/cg_en.pdf

- 85.WHO/Unicef. Handbook IMCI: Integrated management of childhood illness. 2007. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42939/1/9241546441.pdf

- 86.World Health Organization. WHO pocketbook of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common childhood illness. 2013. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/81170/1/9789241548373_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 87.Mackowiak PA, Boulant JA. Fever’s Glass Ceiling. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;22: 525–536. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.3.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Narayan K, Cooper S, Morphet J, Innes K. Effectiveness of paracetamol versus ibuprofen administration in febrile children: A systematic literature review: Antipyretics in paediatric fever. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2017;53: 800–807. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Temple AR, Temple BR, Kuffner EK. Dosing and antipyretic efficacy of oral acetaminophen in children. Clin Ther. 2013;35: 1361–1375.e1–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Martino M, Chiarugi A, Boner A, Montini G, de’ Angelis GL. Working Towards an Appropriate Use of Ibuprofen in Children: An Evidence-Based Appraisal. Drugs. 2017;77: 1295–1311. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0751-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perrott DA, Piira T, Goodenough B, Champion GD. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children’s pain or fever: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158: 521–526. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.6.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.George M, Phelps MA, Kitzmiller JP. Acetaminophen pediatric dose selection: caregiver satisfaction regarding the antipyretic efficacy of acetaminophen in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51: 1030–1031. doi: 10.1177/0009922812456592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Martino M, Chiarugi A. Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management. Pain Ther. 2015;4: 149–168. doi: 10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shahroor S, Shvil Y, Ohali M, Granot E. [Acetaminophen toxicity in children as a “therapeutic misadventure”]. Harefuah. 2000;138: 654–657, 710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kozer E, Barr J, Bulkowstein M, Avgil M, Greenberg R, Matias A, et al. A prospective study of multiple supratherapeutic acetaminophen doses in febrile children. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2002;44: 106–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heard K, Bui A, Mlynarchek SL, Green JL, Bond GR, Clark RF, et al. Toxicity from repeated doses of acetaminophen in children: assessment of causality and dose in reported cases. Am J Ther. 2014;21: 174–183. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182459c53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Temple AR, Zimmerman B, Gelotte C, Kuffner EK. Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of 2 Acetaminophen Dosing Regimens in Febrile Infants and Children: A Report on 3 Legacy Studies. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22: 22–32. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-22.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Southey ER, Soares-Weiser K, Kleijnen J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in paediatric pain and fever. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25: 2207–2222. doi: 10.1185/03007990903116255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Purssell E. Treating fever in children: paracetamol or ibuprofen? Br J Community Nurs. 2002;7: 316–320. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2002.7.6.10477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alvarez-Coca González J, Caballero Mora FJ, Alonso Martín B, Martínez Pérez J. Es aconsejable evitar el ibuprofeno en la enfermedad de Kawasaki? [Is it advisable to avoid ibuprofen in Kawasaki disease?]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009. Jul;71(1):83–4. Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2009.03.019 Epub 2009 May 29. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eyers S, Weatherall M, Shirtcliffe P, Perrin K, Beasley R. The effect on mortality of antipyretics in the treatment of influenza infection: systematic review and meta-analyis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2010;103: 403–411. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.090441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Plaisance KI, Mackowiak PA. Antipyretic therapy: physiologic rationale, diagnostic implications, and clinical consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160: 449–456. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eyers S, Jefferies S, Shirtcliffe P, Perrin K, Beasley R. Antipyretic therapy for influenza infection—benefit or harm? In: https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2011/vol-124-no-1338/letter-eyers. 8 Jul 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kellstein D, Fernandes L. Symptomatic treatment of dengue: should the NSAID contraindication be reconsidered? Postgrad Med. 2019;131: 109–116. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1561916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zoubek ME, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Stephens C. Systematic review: ibuprofen-induced liver injury. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51: 603–611. doi: 10.1111/apt.15645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shen X, Huang Y, Guo H, Peng H, Yao S, Zhou M, et al. Oral ibuprofen promoted cholestatic liver disease in very low birth weight infants with patent ductus arteriosus. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mikaeloff Y, Kezouh A, Suissa S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of severe skin and soft tissue complications in patients with varicella or zoster disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65: 203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02997.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fu L-S, Lin C-C, Wei C-Y, Lin C-H, Huang Y-C. Risk of acute exacerbation between acetaminophen and ibuprofen in children with asthma. PeerJ. 2019;7: e6760. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kanabar D, Dale S, Rawat M. A review of ibuprofen and acetaminophen use in febrile children and the occurrence of asthma-related symptoms. Clin Ther. 2007;29: 2716–2723. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sherbash M, Furuya-Kanamori L, Nader JD, Thalib L. Risk of wheezing and asthma exacerbation in children treated with paracetamol versus ibuprofen: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20: 72. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1102-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.François P, Desrumaux A, Cans C, Pin I, Pavese P, Labarère J. Prevalence and risk factors of suppurative complications in children with pneumonia: Suppurative complications of pneumonia. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99: 861–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Elemraid MA, Thomas MF, Blain AP, Rushton SP, Spencer DA, Gennery AR, et al. Risk factors for the development of pleural empyema in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50: 721–726. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Voiriot G, Dury S, Parrot A, Mayaud C, Fartoukh M. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs May Affect the Presentation and Course of Community-Acquired Pneumonia. CHEST. 2011;139: 387–394. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Le Bourgeois M, Ferroni A, Leruez-Ville M, Varon E, Thumerelle C, Brémont F, et al. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug without Antibiotics for Acute Viral Infection Increases the Empyema Risk in Children: A Matched Case-Control Study. J Pediatr. 2016;175: 47–53.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rainsford KD, Bjarnason I. NSAIDs: take with food or after fasting? Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2012;64: 465–469. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Marriott SC, Stephenson TJ, Hull D, Pownall R, Smith CM, Butler A. A dose ranging study of ibuprofen suspension as an antipyretic. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66: 1037–1042. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.9.1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Autret-Leca E. A general overview of the use of ibuprofen in paediatrics. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2003; 9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Walson PD, Galletta G, Chomilo F, Braden NJ, Sawyer LA, Scheinbaum ML. Comparison of Multidose Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen Therapy in Febrile Children. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146: 626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160170106025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Diseases C on I, Fulginiti VA, Brunell PA, Cherry JD, Ector WL, Gershon AA, et al. Aspirin and Reye Syndrome. Pediatrics. 1982;69: 810–812. 7079050 [Google Scholar]

- 120.Çaksen H, Güler E, Alper M, Üstünbaş HB. A Fatal Case of Reye Syndrome after Varicella and Ingestion of Aspirin. The Journal of Dermatology. 2001;28: 286–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Moroz LA. Increased blood fibrinolytic activity after aspirin ingestion. N Engl J Med. 1977;296: 525–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197703102961001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kokki H, Kokki M. Dose-finding studies of ketoprofen in the management of fever in children: report on two randomized, single-blind, comparator-controlled, single-dose, multicentre, phase II studies. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30: 251–258. doi: 10.2165/11534520-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kokki H, Kokki M. Ketoprofen versus paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen in the management of fever: results of two randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, repeated-dose, multicentre, phase III studies in children. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30: 375–386. doi: 10.1007/BF03256907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Polman HA, Huijbers WA, Augusteijn R. The use of diclofenac sodium (Voltaren) suppositories as an antipyretic in children with fever due to acute infections: a double-blind, between-patient, placebo-controlled study. J Int Med Res. 1981;9: 343–348. doi: 10.1177/030006058100900508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sharif MR, Haji Rezaei M, Aalinezhad M, Sarami G, Rangraz M. Rectal Diclofenac Versus Rectal Paracetamol: Comparison of Antipyretic Effectiveness in Children. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18: e27932. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.27932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Khubchandani RP, Ghatikar KN, Keny S, Usgaonkar NG. Choice of antipyretic in children. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;43: 614–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kamour A, Crichton S, Cooper G, Lupton DJ, Eddleston M, Vale JA, et al. Central nervous system toxicity of mefenamic acid overdose compared with other NSAIDs: an analysis of cases reported to the United Kingdom National Poisons Information Service. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83: 855–862. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Prado J, Daza R, Chumbes O, Loayza I, Huicho L. Antipyretic efficacy and tolerability of oral ibuprofen, oral dipyrone and intramuscular dipyrone in children: a randomized controlled trial. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124: 135–140. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31802006000300005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wong A, Sibbald A, Ferrero F, Plager M, Santolaya ME, Escobar AM, et al. Antipyretic effects of dipyrone versus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen in children: results of a multinational, randomized, modified double-blind study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001;40: 313–324. doi: 10.1177/000992280104000602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Giovannini M, Longhi R, Besana R, Michos N, Sarchi C. Clinical experience and results of treatment with suprofen in pediatrics. 5th communication: a single-blind study on antipyretic effect and tolerability of suprofen syrup versus metamizole drops in pediatric patients. Arzneimittelforschung. 1986;36: 959–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cashman TM, Starns RJ, Johnson J, Oren J. Comparative effects of naproxen and aspirin on fever in children. J Pediatr. 1979;95: 626–629. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80784-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Purssell E. Systematic review of studies comparing combined treatment with paracetamol and ibuprofen, with either drug alone. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96: 1175–1179. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pereira GL, Dagostini JMC, Pizzol T da SD. Alternating antipyretics in the treatment of fever in children: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2012;88: 289–296. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Trippella G, Ciarcià M, de Martino M, Chiappini E. Prescribing Controversies: An Updated Review and Meta-Analysis on Combined/Alternating Use of Ibuprofen and Paracetamol in Febrile Children. Front Pediatr. 2019;7. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yue Z, Jiang P, Sun H, Wu J. Association between an excess risk of acute kidney injury and concomitant use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children, retrospective analysis of a spontaneous reporting system. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70: 479–482. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1643-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wong T, Stang AS, Ganshorn H, Hartling L, Maconochie IK, Thomsen AM, et al. Cochrane in context: Combined and alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen therapy for febrile children. Evid Based Child Health. 2014;9: 730–732. doi: 10.1002/ebch.1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Offringa M, Newton R, Cozijnsen MA, Nevitt SJ. Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children. Cochrane Epilepsy Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017. [cited 9 Apr 2018]. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003031.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rosenbloom E, Finkelstein Y, Adams-Webber T, Kozer E. Do antipyretics prevent the recurrence of febrile seizures in children? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2013;17: 585–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mewasingh LD. Febrile seizures. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3908738/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Murata S, Okasora K, Tanabe T, Ogino M, Yamazaki S, Oba C, et al. Acetaminophen and Febrile Seizure Recurrences During the Same Fever Episode. Pediatrics. 2018;142. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Arana A, Morton NS, Hansen TG. Treatment with paracetamol in infants. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45: 20–29. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.450104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ziesenitz VC, Zutter A, Erb TO, van den Anker JN. Efficacy and Safety of Ibuprofen in Infants Aged Between 3 and 6 Months. Pediatric Drugs. 2017;19: 277–290. doi: 10.1007/s40272-017-0235-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gupta P, Sachdev HPS. Safety of oral use of nimesulide in children: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40: 518–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Aluka TM, Gyuse AN, Udonwa NE, Asibong UE, Meremikwu MM, Oyo-Ita A. Comparison of Cold Water Sponging and Acetaminophen in Control of Fever Among Children Attending a Tertiary Hospital in South Nigeria. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2: 153–158. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.117409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Senz EH, Goldfarb DL. Coma in a child following use of isopropyl alcohol in sponging. J Pediatr. 1958;53: 322–323. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(58)80219-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.McFadden SW, Haddow JE. Coma produced by topical application of isopropanol. Pediatrics. 1969;43: 622–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Moss MH. Alcohol-induced hypoglycemia and coma caused by alcohol sponging. Pediatrics. 1970;46: 445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Arditi M, Killner MS. Coma following use of rubbing alcohol for fever control. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141: 237–238. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460030015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wise JR. Alcohol sponge baths. N Engl J Med. 1969;280: 840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196904102801518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Watts R, Robertson J. Non-pharmacological Management of Fever in Otherwise Healthy Children. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10: 1634–1687. doi: 10.11124/01938924-201210280-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Purssell E. Physical treatment of fever. Arch Dis Child. 2000;82: 238–239. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.3.238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Thomas S, Vijaykumar C, Naik R, Moses PD, Antonisamy B. Comparative effectiveness of tepid sponging and antipyretic drug versus only antipyretic drug in the management of fever among children: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46: 133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Guppy MPB, Mickan SM, Mar CBD. “Drink plenty of fluids”: a systematic review of evidence for this recommendation in acute respiratory infections. BMJ. 2004;328: 499–500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38028.627593.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Martin DD. Fever: Views in Anthroposophic Medicine and Their Scientific Validity. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016: 1–13. doi: 10.1155/2016/3642659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kinmonth AL, Fulton Y, Campbell MJ. Management of feverish children at home. BMJ. 1992;305: 1134–1136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6862.1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Gibson JP. How much bed rest is necessary for children with fever? The Journal of Pediatrics. 1956;49: 256–261. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(56)80181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rabe A, Weiser M, Klein P. Effectiveness and tolerability of a homoeopathic remedy compared with conventional therapy for mild viral infections: Effectiveness and Tolerability of Homoeopathic Remedy. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2004;58: 827–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.van Haselen R, Thinesse-Mallwitz M, Maidannyk V, Buskin SL, Weber S, Keller T, et al. The Effectiveness and Safety of a Homeopathic Medicinal Product in Pediatric Upper Respiratory Tract Infections With Fever. Glob Pediatr Health. 2016;3. doi: 10.1177/2333794X16654851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Lyons N, Nejak D, Lomotan N, Mokszycki R, Jamieson S, McDowell M, et al. An alternative for rapid administration of medication and fluids in the emergency setting using a novel device. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015;33: 1113.e5–1113.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tremayne V. Emergency rectal infusion of fluid in rural or remote settings. 2010. [cited 23 May 2018]. Available: https://web.a.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=13545752&AN=48329032&h=v1IVL0qBvq8mmA4VOif%2fK%2fBLm1kF6DP6ByiDDmGa2AID6nzeeef7mgBWUrUALz7AfXpbQ7hwzyASOebUmheEvg%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d13545752%26AN%3d48329032 doi: 10.7748/en2010.02.17.9.26.c7537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]