Abstract

Background

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States. Reporting of all medical errors is important to better understand the problem and to implement solutions based on root causes. Underreporting of medical errors is a common and a challenging obstacle in the fight for patient safety. The goal of this study is to review common barriers to reporting medical errors.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the literature by searching the MEDLINE and SCOPUS databases for studies on barriers to reporting medical errors. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guideline was followed in selecting eligible studies.

Results

Thirty studies were included in the final review, 8 of which were from the United States. The majority of the studies used self-administered questionnaires (75%) to collect data. Nurses were the most studied providers (87%), followed by physicians (27%). Fear of consequences is the most reported barrier (63%), followed by lack of feedback (27%) and work climate/culture (27%). Barriers to reporting were highly variable between different centers.

1. Introduction

Medical errors (ME) are among the most important patient safety challenges facing hospitals and healthcare systems nowadays. Since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report in 1999 “To Err is Human,” an increasing number of studies have shown how prevalent and deleterious ME are, especially in hospital medicine [1]. With this, healthcare leaders invested time and resources toward identifying and reducing ME [2].

A medical error is defined as “an incidence when there is an omission or commission in planning or execution that leads or could lead to unintended result” [3]. While the majority of ME do not lead to an apparent adverse effect, a significant number of patients either suffer a permanent injury or death from ME every year in the United States and around the world as a result of those errors [4].

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States after heart diseases and cancer [4]. It is estimated that more than 200,000 patients die annually in the United States from ME [5]. Furthermore, in addition to the harm inflicted on patients, medical errors are associated with an increased healthcare cost [6]. In a 2008 report, it was estimated that medical errors costed the healthcare system in the United States more than 17 billion dollars annually [7, 8].

The first step in combating ME and improving patient safety is to study the different types of medical errors to better understand why medical errors happen. The causes, types, and rates of ME can vary from one institution to the other and change over time, especially as we implement changes in our healthcare delivery. Therefore, it is important to capture, track, and analyze all medical errors as possible at the institutional level [2, 9, 10].

As most of the nonmedication medical errors are hard to capture electronically and manual chart review is both cumbersome and time consuming, self-reporting is still the most reliable approach to capture ME [11]. Unfortunately, underreporting of ME is a commonly reported challenge even when healthcare institutions mandated reporting [12]. While there is no consensus on what defines “underreporting of ME,” it commonly refers to the lack of reports on significant ME events. The goal of this study is to review the reported perceived barriers to reporting medical errors by healthcare providers in hospital settings and to identify common themes.

Most of the reports on barriers to reporting ME are single centers; in this systematic review of the literature, we try to investigate whether the barriers to reporting ME varies from institution to the other or not and what common barriers are reported.

2. Methodology

We conducted a systemic review in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline [13].

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

We queried MEDLINE (2000–2020) and SCOPUS (2000–2020) databases for eligible studies. The year 2000 was chosen as the start date for eligibility as the vast of majority of publications regarding ME came after the IOM report in 1999 [1].

On MEDLLINE, a combination of the following search terms was used: (i) errors (medical subject heading (MeSH)), medication errors (MeSH) or near mess, and healthcare (MeSH), (ii) hospitals (MeSH), and (iii) disclosure (MeSH), “report$” (in the title), “ident$” (in the title), or “recog$” (in the title).

On Scopus, the following search string was used: (TITLE ((medica∗ AND error) AND (report∗ OR captur∗)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))).

We manually removed duplicate studies, and we also evaluated additional eligible studies in the references of the final selected studies.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

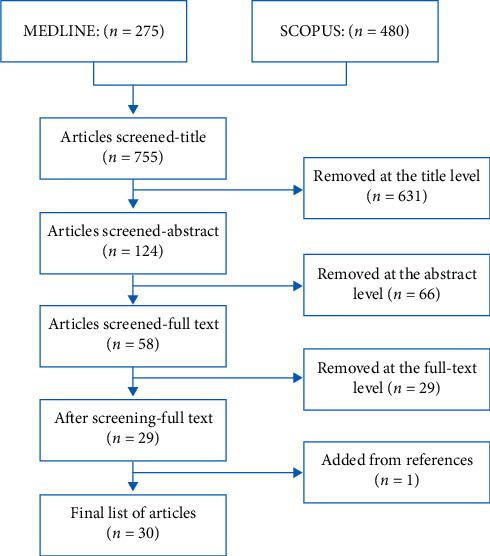

The returned studies were evaluated for proper content. Studies were screened for the following inclusion criteria: (i) English language, (ii) the focus of the research is to identify barriers to ME reporting, (iii) medical errors as defined above, not diagnostic errors or management errors, (iv) in hospital settings, and (v) full-text articles. The overview of the selection process is summarized in Figure 1. The primary investigator screened the citations from the initial search using two-step approach. First, the titles and abstracts of all selected articles were screened for eligibility. Then, for the citations that considered relevant, the full-text we obtained was screened for eligibility.

Figure 1.

The study selection process using the PRISMA guideline.

The following data elements were extracted from the final list of eligible studies: primary objective, study design, sample size, study setting, study subjects, country of the study, year of publication, recruitment of subjects, response rate in survey studies, pertinent results, primary outcomes, and limitations of the study.

3. Results

The search yielded 755 studies of which 30 studies met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 highlights the studies selection process. Table 1 is a brief summary of the included studies [14–43]. Eight of the selected studies were from the United States. The majority of the studies (74%) used self-administered questionnaires to identify perceived barriers for ME reporting. Three studies did post hoc analysis of national databases; those national databases were the results of self-administered questionnaires.

Table 1.

Summary of the selected studies.

| Reference | Country | Publication year | Objective | Study design | Sample size (response rate, %) | Subjects | Setting | Results (most important barriers reported by themes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrison et al. [12] | Iran | 2020 | Medical errors | Survey | 164 (78) | Nurses (n = 77) Physicians (n = 87) |

Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Lack of feedback | ||||||||

| Moher et al. [13] | Turkey | 2019 | Medication errors | Survey | 135 (53) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Poo understanding of ME and importance of reporting | ||||||||

| Mahdaviazad et al. [14] | South Korea | 2019 | Medication errors | Survey | 218 (81) | Nurses | Multicenter (7 hospitals) | Fear of consequences |

| Dirik et al. [15] | Iran | 2019 | Medical errors | Interviews | 18 (NA) | Nurses | Unit specific (pediatric inpatient) | Fear of consequences |

| Work climate/culture | ||||||||

| Kim and Kim [16] | USA | 2018 | Medication errors | Survey | 357 (36) | Nurses | Single hospital | Time consuming |

| Fear of consequences | ||||||||

| Mousavi-Roknabadi et al. [17] | Qatar | 2018 | Medication errors | Survey | 1604 (NA) | Nurses (n = 1089) Physicians (n = 213) Pharmacists (n = 207) |

Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Rutledge et al. [18] | Iran | 2017 | Medication errors | Survey | 328 (65) | Nurses | Multicenter (7 hospitals) | Time consuming |

| Fear of consequences | ||||||||

| Stewart et al. [19] | Saudi | 2017 | Medication errors | Survey | 367 (73) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Fathi et al. [20] | Turkey | 2017 | Medical errors | Interviews | 23 (NA) | Nurses (n = 15) Physicians (n = 8) |

Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Lack of feedback | ||||||||

| Lack of a reporting system | ||||||||

| Hammoudi and Yahya [21] | South Korea | 2017 | Medication errors | Survey | 245 (33) | Pharmacists | Multicenter (32 hospitals) | Lack of understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME |

| Soydemir et al. [22] | Iran | 2017 | Medical errors | Survey | 140 (NA) | Nurses | Unit specific (obstetric ward) | Fear of consequences |

| Kang et al. [23] | USA | 2017 | Medication errors | Survey | 71 (45) | Nurses | Unit specific (ER) | Lack of feedback |

| Work climate/culture factors | ||||||||

| Mobarakabadi et al. [24] | UAE | 2016 | Medication errors | Interviews | 29 (NA) | Nurses (n = 10) Pharmacists (n = 10) Physicians (n = 9) |

Multicenter (3 hospitals) | Lack of feedback |

| Work climate/culture | ||||||||

| Farag et al. [25] | USA | 2016 | Medical errors | Post hoc analysis of a national database | 5339 (NA) | Pharmacists | Multicenter (NA) | Lack of feedback |

| Work climate/culture | ||||||||

| Alqubaisi et al. [26] | Taiwan | 2016 | Medication errors | Survey | 15 (41) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear from consequences |

| Patterson and Pace [27] | Iran | 2015 | Medical errors | Survey | 348 (16) | Physicians, nurses, and others | Multicenter (5 hospitals) | Lack of a reporting system |

| Lack of understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME | ||||||||

| Yung et al. [28] | USA | 2015 | Medical errors | Post hoc analysis of a national database | NA | All employees | Multicenter (NA) | Work climate/culture |

| Poorolajal et al. [29] | USA | 2015 | Medical errors | Survey | 40 (60%) | Nurses | Unit specific (surgical) | Work climate/culture |

| Derickson et al. [30] | USA | 2014 | Medical errors | Survey | 300 (75) | Nurses (n = 186) Physicians (n = 26) Paramedics (n = 78) |

Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Farag and Anthony [31] | South Korea | 2014 | Medical | Survey | 522 (77) | Nurses | Multicenter (2 hospitals) | Work climate/culture |

| Jahromi et al. [32] | UK | 2014 | Medication errors | Interviews | 50 (NA) | Nurses | Unit specific (psychiatric hospital) | Time consuming |

| Lack of understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME | ||||||||

| Fear of consequences | ||||||||

| Hwang and Ahn [33] | Iran | 2014 | Medication errors | Survey | 100 (NA) | Nurses | Single hospital | Lack of a reporting system |

| Lack of feedback | ||||||||

| Lack of understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME | ||||||||

| Haw et al. [34] | USA | 2013 | Medical errors | Post hoc analysis of a national database | 5339 (NA) | Pharmacists | Multicenter (NA) | Work climate/culture |

| Mostafaei et al. [35] | Saudi | 2013 | Medication errors | Survey | 307 (88) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Patterson et al. [36] | Canada | 2012 | Medication errors | Focus group | NA | NA | Multicenter (4 hospitals) | Time consuming |

| Fear of consequences | ||||||||

| Aboshaiqah [37] | Turkey | 2012 | Medication errors | Survey | 119 (72) | Nurses | Unit specific (pediatrics) | Fear of consequences |

| Hartnell et al. [38] | Taiwan | 2010 | Medication errors | Survey | 838 (84) | Nurses | Multicenter (5 hospitals) | Fear of consequences |

| Toruner and Uysal [39] | UK | 2009 | Medical errors | Survey | 134 (66) | Nurses (n = 82) Physicians (n = 55) |

Unit specific (surgical units) | Lack of understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME |

| Lack of feedback | ||||||||

| Chiang [40] | Taiwan | 2006 | Medication errors | Survey | 597 (74) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

| Time consuming | ||||||||

| Lack of feedback | ||||||||

| Kreckler et al. [41] | USA | 2005 | Medication errors | Survey | 25 (41) | Nurses | Single hospital | Fear of consequences |

As shown in Figure 2, most of the included studies are relatively recent. Nurses were the most surveyed/studied healthcare providers, included in 26 (87%) included studies, followed by physicians (27%) and pharmacists (17%). Some of the studies (23%) recruited subjects from specific inpatient units, and the rest recruited subjects from all inpatient units. Eighteen of the included studies evaluated perceived barriers to reporting medication errors or medication administration errors, and the rest evaluated perceived barriers to reporting any medical error which included medication errors.

Figure 2.

Year of publication of the selected studies.

3.1. Barriers to Reporting ME

We identified 7 common themes to the barriers reported in the included studies (Table 2). We discuss the common themes in the following sections.

Table 2.

Common themes of barriers to reporting medical errors.

| Theme | Number of studies reported this theme as a significant barrier |

|---|---|

| Fear of consequences | 19 |

| Lack of feedback | 8 |

| Work climate/culture | 8 |

| Poor understanding of ME and the importance of reporting ME | 6 |

| Time consuming | 5 |

| Lack of a reporting system | 3 |

| Personal factors | 3 |

3.1.1. Fear of Consequences

Fear of consequences is the most reported factor for underreporting ME. 19 out of the 30 studies reported that fear is a significant barrier to report ME [14–16, 20–22, 25, 37–40, 42].

Fear of being blamed for the error is by far the most reported fear. But additionally, providers reported fear of losing one's job, fear of patient's or family's response to the ME, fear of being recognized as incompetent, fear of legal consequences, fear of punishment, and fear of losing respect by coworkers were also commonly reported [14–16, 20–22, 25, 32, 37–40, 42].

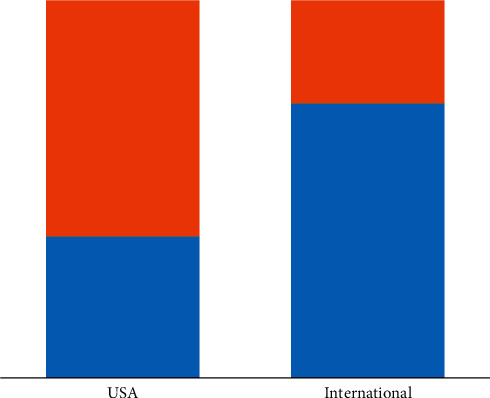

Not only is “fear of consequences” the most reported factor for underreporting, it also happens to be the most significant factor for underreporting in most of the included studies [14–16, 20–22, 25, 32, 37–40, 42]. While fear of consequences might be more prominent in certain cultures than others and more prominent in hospitals with hierarchical structures [16], it has been reported at both local and international levels and in different management styles. Additionally, fear as a factor has not changed over the years. It is unclear whether an option to anonymously report ME would eliminate the fear barrier [14–16, 20–22, 25, 32, 37–40, 42]. It does, however, seem that “fear of consequences” as a barrier to reporting is less prevalent in the United States compared to other countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of studies where “fear of consequences” is an important barrier. Blue, yes, “fear of consequences” is an important barrier. Orange, no, “fear of consequences” is not an important barrier.

It is important to highlight that some of the included studies did not find “fear of consequences” as a significant factor for underreporting [41]. Findings from those studies suggest that we can overcome “fear of consequences” as a barrier.

3.1.2. Lack of Feedback

Both lack of feedback by administration and/or negative feedback have been associated with underreporting. While some studies reported the negative impact of improper feedback, some reported the positive impact of appropriate feedback. Specifically, it was evident that feedback to the reporting person about the error supports the provider who committed the error and communication openness regarding errors all improved reporting of ME [14, 22, 27, 29, 31, 36, 40–42].

3.1.3. Work Climate/Culture

The administration's attitude toward ME and the work environment are important factors that influence ME reporting [17, 21, 40, 42]. It has been observed that when hospital administrators' responses to ME focus on the individuals, rather than the system, reporting rates of ME decrease [21]. Additionally, the lack of safety culture and error prevention programs is associated with underreporting [27]. On the other hand, work environments with a strong teamwork perception and psychological safety amongst employees are associated with better reporting of ME [30, 32]. Work climate/culture issues as a barrier to reporting medical errors is the most reported barrier in studies from the United States (Table 1).

3.1.4. Poor Understanding of ME and the Importance of Reporting ME

A number of studies reported poor understanding by providers as to what constitute a medical error as a barrier to reporting. Providers in a number of studies reported the lack of clear definition of medical errors and the lack of a clear protocol on what incidents need to be reported, as a significant barrier to reporting ME. Additionally, poor understanding of the importance of reporting ME is a significant barrier to reporting as well [21, 23, 35, 38, 41, 44].

3.1.5. Time Consuming

Busy work schedule and high workload have been reported as significant factors for underreporting. Additionally, reporting itself is time consuming and cumbersome. Both forms of reporting systems (paper and electronic) are time consuming [20, 23, 25, 38, 41, 44]. Physicians more than nurses reported time constrains as a barrier to reporting ME [41].

3.1.6. Lack of the Reporting System

It is no surprise that the lack of a reporting system is a barrier. Many studies, mostly international, reported the lack of a reporting system as a barrier to reporting [22, 29, 35]. A number of studies showed better reporting with electronic systems compared to paper reporting [45].

3.1.7. Personal Factors

A number of personal factors influence the reporting of ME. Younger and/or less experienced nurses are less likely to report ME. The longer the employment period is, the more likely it is for an employee to report ME. Additionally, personal experience with ME affected the rates of reporting medical errors [17, 36, 40, 42].

4. Discussion

In this systematic review of literature, we present reported barriers to ME reporting in hospital setting. We identified and presented common themes to the reported barriers. We also highlighted the variation in perceived barriers between different centers and countries.

The healthcare system and healthcare delivery vary from one country to the other. Thus, it is no surprise that perceived barriers to reporting were also variable between different countries. For example, “fear of consequences” is more prevalent in East Asia and Middle East compared to the United States. On the other hand, work climate/culture is more reported as barrier in centers across the United States. Reported barriers also varied from one center to the other within the same country. These differences are probably secondary to different management strategies, reporting systems, different work place culture, and whether patient safety is a focus of the hospital administration or not.

Nurses, physicians, and pharmacists are the most studied groups of providers regarding ME and the reporting of ME. Unfortunately, none of the studies directly compared the barriers perceived by these different groups. It is logical to anticipate different perception of barriers between these groups of the provider. Additionally, current studies failed to include other groups of clinical providers such as respiratory therapists, physical/occupational therapists, and laboratory and radiology technicians, despite their significant role in hospital medicine.

Fear of consequences is reported in most of the studies we reviewed as one of the important barriers to reporting ME. Some of the sources for fear are modifiable, for example, fear of being blamed for the error or fear of losing one's job. Changing workplace culture and strategies in addressing reporting ME is an imperative step to overcome this barrier. A work culture that promotes patient safety, encourages error reporting, and implements system changes is essential. On the other hand, fear secondary to concern over patients' and their families' reactions to medical error is not modifiable or predictable. Educating the providers on the importance of ME disclosure to the patients/families and providing them with the necessary tools to better communicate ME and adverse events can help overcome some of these nonmodifiable fears.

The most challenging and probably most effective change to overcome barriers to reporting medical errors is the adoption of patient safety culture. Under patient safety culture, employees are rewarded and feel empowered to report and act on medical errors. This safety culture helps overcome the employee's fear of consequences and provides a work environment that is supportive of error recognition and reporting.

The reviewed studies showed that a significant number of healthcare providers lack proper understanding of what constitutes a medical error. Poor understanding of medical errors and the importance of reporting both lead to underreporting. Educating healthcare providers on what constitutes medical errors, the benefit of reporting medical errors even in the absence of apparent harm, and that medical error reports are used to identify system deficiencies rather than individual faults, can help improve ME reporting and eventually decrease ME.

As hospitals across the world are adopting changes in their management and care delivery to improve patient's safety, the barriers to reporting medical errors may change. Periodic evaluation of this matter is needed to continue the improvement process.

Healthcare institutions are encouraged to evaluate their ME reporting rates, perform root cause analysis for underreporting at the local level, and finally implement changes to improve reporting. The common themes we identified in this study can guide healthcare institutions in their local root cause analysis. Causes of ME and factors for underreporting ME may change with time as we implement changes to our healthcare delivery. Thus, continuous tracking of ME and periodic evaluation of the root causes is needed to continue the improvement process. In some institutions, deep changes in the hospital's management strategy to align with and encourage patient safety culture might be needed.

Our study has several limitations. The first limitation is inherent to the nature of survey and interview studies. All published reports on this matter used either self-administered questionnaires or interviews. The second limitation is inherent to the nature of systematic review of the literature. The variability of study methodology and study population makes it challenging to draw an objective conclusion. Due to the variability in the methodology and study population in the selected studies, a meta-analysis is not feasible and only a subjective conclusion can be presented.

5. Conclusion

We identified and presented 7 common themes of barriers to report medical errors. Fear of consequences is the most reported barrier worldwide, while work climate/culture is the most reported barrier in the United States. Barriers to reporting can vary from one center to the other. Each healthcare institution should identify local barriers to reporting and implement potential solutions. Overcoming the barriers may require changes in the hospital's management strategy to align with and encourage a patient safety culture. Further studies are needed to investigate whether an anonymous reporting system can help overcome the fear barrier and to compare perceived barriers to report ME between different healthcare providers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kohn L. T., Corrigan J., Donaldson M. S. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press (US); 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann B., Rohe J. Patient safety and error management. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2010;107(6):92–99. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grober E. D., Bohnen J. M. Defining medical error. Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. 2005;48(1):39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makary M. A., Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ Journal. 2016;353 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139.i2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James J. T. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. Journal of Patient Safety. 2013;9(3):122–128. doi: 10.1097/pts.0b013e3182948a69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andel C., Davidow S. L., Hollander M. D., Moreno D. A. Quality of care in the Korean health system. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Korea 2012. 2012;39 1:39–75. doi: 10.1787/9789264173446-5-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shreve J., Bos J.V. D., Gray T. K., Halford M. M., Rustagi K., Ziemkiewicz E. The economic measurement of medical errors sponsored by society of actuaries’ health section prepared by. Society of Actuaries’ Health Section. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bos J. V. D., Rustagi K., Gray T., Halford M., Ziemkiewicz E., Shreve J. The $17.1 billion problem: the annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Affairs. 2011;30(4):596–603. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf Z. R., Hughes R. G. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Error reporting and disclosure. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaldjian L. C., Jones E. W., Wu B. J., Forman-Hoffman V. L., Levi B. H., Rosenthal G. E. Reporting medical errors to improve patient SafetyA survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(1):40–46. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Classen D. C., Holmgren A. J., Co Z., et al. National trends in the safety performance of electronic health record systems from 2009 to 2018. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5547.e205547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison M., Cope V., Murray M. The underreporting of medication errors: a retrospective and comparative root cause analysis in an acute mental health unit over a 3-year period. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2018;27(6):1719–1728. doi: 10.1111/inm.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahdaviazad H., Askarian M., Kardeh B. Medical error reporting: status quo and perceived barriers in an orthopedic center in Iran. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;11:p. 14. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_235_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dirik H. F., Samur M., Intepeler S. S., Hewison A. Nurses’ identification and reporting of medication errors. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019;28(5-6):931–938. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M. S., Kim C.-H. Canonical correlations between individual self-efficacy/organizational bottom-up approach and perceived barriers to reporting medication errors: a multicenter study. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mousavi-Roknabadi R. S., Momennasab M., Askarian M., Haghshenas A., Marjadi B. Causes of medical errors and its under-reporting amongst pediatric nurses in Iran: a qualitative study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2019;31(7):541–546. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutledge D. N., Tina R., Gary O. Barriers to medication error reporting among hospital nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(9-10):1941–1949. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart D., Thomas B., MacLure K., et al. Exploring facilitators and barriers to medication error reporting among healthcare professionals in qatar using the theoretical domains framework: a mixed-methods approach. PLoS One. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204987.e0204987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fathi A., Hajizadeh M., Moradi K., et al. Medication errors among nurses in teaching hospitals in the west of iran: what we need to know about prevalence, types, and barriers to reporting. Epidemiology and Health. 2017;39 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017022.e2017022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammoudi B. M., Yahya O. A. Factors associated with medication administration errors and why nurses fail to report them. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017;32(3):1038–1046. doi: 10.1111/scs.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soydemir D., Intepeler S. S., Mert H. Barriers to medical error reporting for physicians and nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2010;39(10):1348–1363. doi: 10.1177/0193945916671934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang H.-J., Park H., Oh J. M., Lee E.-K. Perception of reporting medication errors including near-misses among Korean hospital pharmacists. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(39) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007795.e7795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mobarakabadi S. S., Ebrahimipour H., Najar A. V., Janghorban R., Azarkish F. Attitudes of mashhad public hospital’s nurses and midwives toward the causes and rates of medical errors reporting. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR. 2017;11 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23958.9349.QC04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farag A., Blegen M., Gedney-Lose A., Lose D., Perkhounkova Y. Voluntary medication error reporting by ED nurses: examining the association with work environment and social capital. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2017;43(3):246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alqubaisi M., Tonna A., Strath A., Stewart D. Exploring behavioural determinants relating to health professional reporting of medication errors: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2016;72(7):887–895. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson M. E., Pace H. A. A cross-sectional analysis investigating organizational factors that influence near-miss error reporting among hospital pharmacists. Journal of Patient Safety. 2016;12(2):114–117. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yung H.-P., Yu S., Chu C., Hou I.-C., Tang F.-I. Nurses’ attitudes and perceived barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors. Journal of Nursing Management. 2016;24(5):580–588. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poorolajal J., Rezaie S., Aghighi N. Barriers to medical error reporting. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;6:p. 97. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.166680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derickson R., Fishman J., Osatuke K., Teclaw R., Ramsel D. Psychological safety and error reporting within veterans health administration hospitals. Journal of Patient Safety. 2015;11(1):p. 7. doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farag A. A., Anthony M. K. Examining the relationship among ambulatory surgical settings work environment, nurses’ characteristics, and medication errors reporting. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 2015;30(6):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jahromi Z. B., Parandavar N., Rahmanian S. Investigating factors associated with not reporting medical errors from the medical team’s point of view in jahrom, Iran. Global Journal of Health Science. 2014;6(6):p. 96. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang J.-I., Ahn J. Teamwork and clinical error reporting among nurses in Korean hospitals. Asian Nursing Research. 2015;9(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haw C., Stubbs J., Dickens G. L. Barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors and near misses: an interview study of nurses at a psychiatric hospital. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2014;21(9):797–805. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mostafaei D., Barati Marnani A., Mosavi Esfahani H., et al. Medication errors of nurses and factors in refusal to report medication errors among nurses in a teaching medical center of Iran in 2012. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2014;16(10) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.16600.e16600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson M. E., Pace H. A., Fincham J. E. Associations between communication climate and the frequency of medical error reporting among pharmacists within an inpatient setting. Journal of Patient Safety. 2013;9(3):129–133. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e318281edcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aboshaiqah A. E. Barriers in reporting medication administration errors as perceived by nurses in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research. 2013;17(2):130–136. doi: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.17.02.76110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartnell N., MacKinnon N., Sketris I., Fleming M. Identifying, understanding and overcoming barriers to medication error reporting in hospitals: a focus group study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2012;21(5):361–368. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toruner E. K., Uysal G. Causes, reporting, and prevention of medication errors from a pediatric nurse perspective. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of the Royal Australian Nursing Federation. 2012;29(4):28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang H.-Y., Lin S.-Y., Hsu S.-C., Ma S.-C. Factors determining hospital nurses’ failures in reporting medication errors in Taiwan. Nursing Outlook. 2010;58(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreckler S., Catchpole K., McCulloch P., Handa A. Factors influencing incident reporting in surgical care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):116–120. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.026534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiang H.-Y., Pepper G. A. Barriers to nurses’ reporting of medication administration errors in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(4):392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulanimo V. M. Nurse’s perceptions of causes of medication errors and barriers to reporting. Master’s Projects. 2005;822 doi: 10.31979/etd.nr6d-3nhy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uribe C. L., Schweikhart S. B., Pathak D. S., Studies E., Marsh G. B. Perceived barriers to medical-error reporting: an exploratory investigation. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2002;47(4):263–280. doi: 10.1097/00115514-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unal A., Seren İntepeler S. Medical error reporting software program development and its impact on pediatric units’ reporting medical errors. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;36(2):10–15. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]