Abstract

Introduction

People who are homeless experience higher morbidity and mortality than the general population. These outcomes are exacerbated by inequitable access to healthcare. Emerging evidence suggests a role for peer advocates—that is, trained volunteers with lived experience—to support people who are homeless to access healthcare.

Methods and analysis

We plan to conduct a mixed methods evaluation to assess the effects (qualitative, cohort and economic studies); processes and contexts (qualitative study); fidelity; and acceptability and reach (process study) of Peer Advocacy on people who are homeless and on peers themselves in London, UK. People with lived experience of homelessness are partners in the design, execution, analysis and dissemination of the evaluation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval for all study designs has been granted by the National Health Service London—Dulwich Research Ethics Committee (UK) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s Ethics Committee (UK). We plan to disseminate study progress and outputs via a website, conference presentations, community meetings and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Keywords: primary care, public health, qualitative research, statistics & research methods, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a mixed methods evaluation, offering multiple perspectives on the effect and mechanisms.

For cohort study outcomes we used the National Health Service Hospital Episode Statistics database, an objective source with direct applications for policy.

The cohort study outcomes excludes care received at general practitioner surgeries, an important site of healthcare.

The cohort study findings are subject to bias from unmeasured confounders.

Introduction

Homelessness has been increasing in England since 2010;1 it is estimated that over a quarter of a million people were homeless in England in 2019, mostly in temporary accommodation, but also in hostels and rough sleeping.2 These numbers are likely to increase further following the economic impact of COVID-19.3 People who are homeless are more likely to experience physical, mental and substance use disorders,4 often in combination,4 5 than people who are stably housed; these disorders may have precipitated or contributed to homelessness, or were instigated by or aggravated by it.6 Frequent health challenges faced by people who are homeless in England and Wales are evidenced by the average age of death: 45 years for men and 43 years for women.7

In addition to managing poor mental and physical health, uptake and access to health services is often restricted for people experiencing homelessness. Structural challenges such as cost of transportation or services, navigating complicated booking systems and stigma from service providers can create significant barriers, combined with difficulties in reconciling daily demands of being homeless that can deter people from prioritising care.8 9 As a result, people experiencing homelessness are disproportionately likely to use accident and emergency departments (37% in the past 6 months) and to be admitted to the hospital (27% in past 6 months).4 In the UK, this pattern of service use results in per capita hospital costs which are four to eight times higher than the general population,10 motivating policy focus on socially excluded groups.11

To improve equity of health outcomes for excluded groups such as people who are homeless, researchers and advocates have been developing the Inclusion Health agenda,12 within which interventions developed and delivered by people with lived experience have been identified as a promising strategy. A 2017 systematic review of peer-delivered interventions for adults who were homeless13 found consistent, though low quality, evidence of improved outcomes in several different domains of well-being, including physical health, mental health, substance use and housing. Of the four studies in the systematic review which measured the effect on healthcare use,14–17 all had positive findings but only one15 was judged to be of high quality. Alongside measurement of healthcare outcomes, there is also a need to elaborate on the mechanisms linked to peer-delivered interventions. A realistic synthesis of peer support models pointed towards the role of peers in providing empathy, understanding and acceptance,13 and others hypothesise the effect through role-modelling health-seeking behaviours and providing social support,18 but there is a paucity of evidence for these mechanisms.

There is a need for highquality evidence to measure the effects of peer interventions on a range of clinical and social outcomes and to elaborate on the mechanisms and context linked to improve health and well-being of this vulnerable and growing population. Here, we set out the protocol for an evaluation of a peer-delivered advocacy intervention on healthcare use for people who are experiencing homelessness in London, UK.

Methods and analysis

The aim of the project is to evaluate the impact, cost efficacy and process mechanisms through which peer advocacy intervention improves healthcare attendance, and health and social outcomes among people experiencing homelessness in London. Objectives will be achieved through the implementation of four linked studies: a qualitative study, a cohort study, a cost–consequence analysis and a process evaluation.

The specific objectives and study designs are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Objectives and study designs for Homeless Health Peer Advocacy evaluation, London, UK, 2020–2022

| Objective | Design |

| 1. To explore the mechanisms, contexts and outcomes for peer advocacy and how they interplay with broader social and structural factors that shape health and social welfare and affect access to services to develop a Theory of Change | Qualitative |

| 2. To explore the range of social and health outcomes the peer support programme brings to the peers themselves, and the mechanisms and contexts for these outcomes | Qualitative |

| 3. To estimate the effect of engagement with peer advocacy on health service use (ie, outpatient appointments, use of emergency services and hospital admissions) | Cohort |

| 4. To estimate change in health service use before and after engagement with peer advocates | Cohort |

| 5. To measure associations between (non)engagement with peer advocacy on health and social outcomes, and access to health services, including the mediating effect of other macrostructural, community and individual factors | Cohort |

| 6. To perform an economic evaluation of peer advocacy compared with no provision on attendance at health services and the health and social welfare of homeless populations | Cost–consequence |

| 7. To assess the fidelity, acceptability and reach of the intervention | Process |

Patient and public involvement

The studies are informed through a participatory approach,19 which is increasingly used within social science and epidemiological research with excluded populations. People with lived experience of homelessness are included as co-researchers in all aspects of the study design, data collection and analysis and are included as members of our study steering committee, which also includes clinicians, researchers and local government officials. The committee will be consulted for reviewing study instruments; collecting, analysing and disseminating data for qualitative and quantitative designs; and for guidance across all designs and dissemination activities.

Setting and context

We will draw on the UK government legal definition of homelessness comprising: people sleeping rough, people sleeping in a hostel, and people in insecure or short-term accommodation, such as in a squat or on a friend’s floor, or who cycle into rough sleeping and the hostel system.20 It has been estimated that 170 000 people in London were homeless as of December 2019,2 a figure which includes 10 726 people who sleep rough.21 According to a 2015 health needs audit of England, 71% of people experiencing homelessness are men, 78% report a physical health problem and 44% have been diagnosed with a mental health condition.4

All legal residents of the UK are entitled to healthcare through the National Health Service (NHS), which is free at the point of care. Primary and emergency care is open and free to all, though undocumented persons are without recourse to public funds and required to pay for prescriptions, dental care, secondary care and community care. In London, current efforts to improve healthcare accessibility for adults currently homeless include street outreach services, peripatetic nursing, mobile tuberculosis testing, hospital discharge teams,5 specialist hostels (eg, for people affected by substance dependency or severe mental disorders) and five specialist primary care clinics.

This protocol describes the evaluation of a peer advocacy programme that has been commissioned by several local government councils within London, and which has been run by a third sector organisation, Groundswell, following its development in 2010.

Our working definition of peer advocacy is the provision of support by trained advocates with experience of homelessness to those currently homeless, to help them overcome the practical, personal and systemic barriers to accessing health and social care, and to increase their confidence and skills to independently access services. The Groundswell model of peer advocacy fits within a broader typology of peer involvement in healthcare processes.22 Peer advocacy differs from informal support such that people might give each other within a hostel or street setting, or organised support groups and communities since it is unidirectional and intentional.13 It is further distinguished by being service and professional led, rather than community led23 as in other forms of community mobilisation and activism. Groundswell’s peers are volunteers who have cleared a background check which enables them to volunteer in NHS settings, have two references, including one from a key worker, and who have completed 22 days of training (online supplemental file 1), with ongoing training provided as necessary alongside monthly supervision meetings. Peers are provided with a smartphone and are reimbursed for travel costs. Some peers progress to paid positions, including within Groundswell or the NHS.

bmjopen-2021-050717supp001.pdf (854.9KB, pdf)

As of 2020, the Groundswell’s peer advocacy programme had been commissioned by 10 of the 32 local government authorities in London, and typically key workers (eg, social workers, hostel staff and day centre staff) in these areas refer clients who have problems managing their health and/or need help attending a general practitioner (GP), outpatient or other medical appointment. Peers also periodically visit hostels and day centres in these 10 areas to raise awareness of health and care for people who are homeless, and to sign up individuals as clients or occasionally as potential future peer advocates.

A core activity of peer advocacy is to accompany clients to a scheduled healthcare appointment. On first contact, a peer meets their client at a designated meeting point, usually at or near the client’s place of sleep, where the peer briefs the clients about their remit and clients give oral consent to proceed. A peer advocacy engagement can include several components. Before the appointment, peers help clients understand the nature of their appointment, take inventory of concerns which must be discussed at the appointment, and manage transport. For clients with severe mobility impairment, advocates arrange a taxi. Clients can request accompaniment to appointments with the peer, who ensures that the clients’ concerns are raised and adequately addressed. After the appointment, peers offer advice on managing follow-up appointments or preparing for inpatient admission. Peers are provided discretionary funds to meet at a café to discuss healthcare needs and are encouraged to use a four item Planning and Debrief Tool to aid with planning and evaluation. Clients will typically have a different peer at each health appointment, though will be matched to a specific peer if they are fluent in the same language or have a specialist appointment type. Ultimately, peers provide support for clients to increase their ability to independently manage their healthcare. Notably, peers do not provide medical advice, direct support or counselling for drug, alcohol or mental health problems, and are not a befriending service. While it is not in their remit to offer support for issues which are not directly linked to healthcare (eg, housing, food and benefits), peers can signpost to other services. Information disclosed during peer advocacy meetings is kept confidential within the advocacy team. If a client makes a credible threat of harm to self or another person, a peer is obliged to report the incident to the volunteer manager, who in turn will disclose the concern to a relevant authority such as a key worker, police or health provider.

There are no formal eligibility criteria to become a client. No one is excluded by residency status or language fluency. The most common route to a peer engagement is for a key worker at a hostel or day centre, or street outreach workers, to refer to Groundswell when someone needs support for an upcoming health appointment (eg, hospital outpatient care, dentist or GP). There is no minimum or maximum number of visits for which a client can request support.

Qualitative study

The qualitative study seeks to understand the context, mechanisms and outcomes associated with the peer advocacy programme, to develop a theoretical model (‘Theory of Change’) to illustrate how peer advocacy works and for whom (objective 1), and explore and define the range of social and health outcomes the peer advocacy programme brings to the peers themselves (objective 2).

Sample size

We aim to conduct interviews with four different participant groups: people who are homeless (with and without experience of peer advocacy, n=50 each), peer advocates (n=20), and Groundswell staff and other stakeholders (n=10) (discussed below). Data collection will continue until we anticipate theoretical ‘saturation’24—the point at which further data no longer offers novel analytical insights—has been achieved. When possible, we will supplement these interviews by shadowing healthcare appointments and following a cohort of peer advocates as they are recruited, trained and begin volunteering. We will also conduct ethnographic observation in the Groundswell offices in order to build rapport with staff and volunteers, and deepen our understanding of the environment within which peers are trained and engaged.

Interviews with Groundswell staff and stakeholders (online supplemental material) will compare experiences of peer advocacy among staff from a variety of professional contexts and explore their perspectives on how, why and for whom peer advocacy works. These interviews will also investigate the potential influence of the wider health system and the politicoeconomic context. Meanwhile, interviews with clients will focus on understanding experiences of peer advocacy, with a focus on health and social outcomes. These interviews will explore the configurations elaborated in an emergent Theory of Change as well as the acceptability, fidelity and reach of the peer advocacy programme. The subsample of interviews with people who are homeless and who are not peer advocacy clients will explore experiences of accessing healthcare, barriers to accessing peer advocacy, reasons for disengagement, and any possible network and diffusion effects of peer advocacy.

Interviews will be semistructured and will aim to capture in-depth insight. However, as interview length and depth will ultimately respond to the external contingencies of the interview—principally the time available from interviewees—we expect the interviews to vary in length from 20 min to 1 hour. Clients and non-clients will be offered £10 to thank them for their participation, along with the latest edition of the Pavement magazine,25 which contains an updated list of support services for people who are homeless in London.

Data collection and recruitment

Qualitative data collection will take the form of semistructured interviews (online supplemental file 2) with the following four groups of people: (1) clients (people who accessed peer advocacy at least once); (2) non-clients (people who are homeless, age 25+ years and who have never accessed peer advocacy); (3) peers (including those in training, those currently volunteering, and those who have moved on to paid employment or other opportunities); and (4) Groundswell staff (including those who are currently employed by Groundswell and involved in supporting or managing peers, and stakeholders who are working in service delivery, support or policy in relation to homelessness in London).

bmjopen-2021-050717supp002.pdf (122.3KB, pdf)

We will initially recruit participants purposively via Groundswell, day centres and hostels, seeking to engage a range of participants according to age, gender, ethnicity, health status and contact with the peer advocates. Recruitment will subsequently extend to stakeholders from NHS primary and secondary care sites. Further sampling will be increasingly theoretical, following the initial purposive exploration and responding to emerging analyses and the experiences of subgroups identified as having particular outcomes and experiences of peer advocacy.

Analysis

Analysis will principally follow a grounded and abductive strategy26 27 to develop the theory of peer advocacy, which draws on extant empirical research and theoretical literature, while allowing for inductive insight. Specific analytical steps will follow a grounded theory approach,27 by coding data descriptively, before exploring links across the coded data to develop selective conceptual categories. We will subsequently draw on broader social science insight, as well as the insights from co-researchers with lived experience of homelessness, to develop and refine a theoretical model of peer advocacy. Supportive analytical strategies will include: (1) memo writing to explore concepts and theoretical links; (2) comparison between individuals and subgroups through developing framework matrices linked to close attention to deviant cases; and (3) triangulation of data collected from different methods—including both interviews and observation and different members of the research team and including those with and without lived experience of homelessness. Data collection and analysis will be iterative, with analysis beginning directly from the beginning of the study, to inform sampling and to allow emerging theoretical conclusions to be integrated into ongoing data collection and thereby fully developed.

Cohort study

We aim to estimate the effect of peer advocacy on the number of missed outpatient appointments, accident and emergency department visits and inpatient admissions over a 12-month period (objective 3). Objectives 4 and 5 are secondary analyses which we will detail in a future report.

Eligibility criteria

All new peer advocacy clients are eligible to participate in the cohort study, provided they have not yet completed two healthcare appointments with a peer. We will recruit a comparison group of non-clients, who, like the peer advocacy clients, are: (1) currently homeless per UK legal definition;20 (2) facing ongoing physical, mental or substance use problems; and (3) facing challenges in meeting their healthcare needs. Across both arms, participants have to be fluent in English or Polish, and cognitively able to provide informed consent and complete a 30-minute questionnaire.

Sample size

Our primary outcome is the number of outpatient appointments classified as ‘did not attend’ (DNA) in 12 months, as documented in hospital records. Based on historic Groundswell data, we anticipate 150 people will become new clients of peer advocates over a 6-month period, of whom 80% will consent to participate in the research study, of which 70% will link to hospital records, resulting in 84 participants for analysis. Informed by hospital use figures from London28 and by an earlier pilot evaluation of Groundswell’s peer advocacy programme,18 we estimate that peer advocacy clients will have an average of 0.06 DNA appointments over 12 months, similar to that in the general population, compared with 0.42 DNA appointments for non-client participants. To detect this difference with 80% power and two-sided alpha of 0.05, we must analyse 270 participants in the comparison arm, and so will enrol a minimum of 386 participants, allowing for 70% linkage to hospital records.

Recruitment

The data manager at Groundswell will flag new clients who have an upcoming appointment, and will schedule a peer advocate to meet at the client’s preferred location. The peer will ask the client for permission to be contacted for research, affirm that permission is voluntary and has no effect on provision of peer advocacy, and if given, share contact details with the research team.

For recruitment into the comparison arm, we listed all hostels and day centres in London and identified a total of 120 venues where Groundswell are not active but would be if commissioned by the local government. We will request support from managers and key workers at these venues to identify potentially eligible individuals to the research study, and if interest is expressed, to share contact details with the research team.

The research team will recruit participants and collect questionnaire data remotely, though will consider in-person field work as originally envisaged, if local, national and institutional COVID-19-related regulations allow.

Baseline data collection

A co-researcher will phone or video call the recruit to describe the study, discuss contents of the study information sheet and consent form and, if appropriate, proceed with informed consent. Recruits who consent can proceed to the baseline questionnaire. The co-researcher will administer a 120-item structured questionnaire in English or Polish on a tablet device with the Open Data Kit (ODK) collect app. The questionnaire (online supplemental file 3) contains the following sections: sociodemographic characteristics; homelessness characteristics and multiple exclusion homelessness; presence of physical, mental and substance use problems; barriers to healthcare; health-related self-efficacy; health-related social capital; help with healthcare appointments; depression and anxiety screening; substance use; experience of violence and of sex work; contact with police and justice system; smartphone use; willingness to use a COVID-19 contact tracing app; and personally identifying information for linkage to outcome data. The full questionnaire—which includes the source of each item—is available on the project website www.lshtm.ac.uk/hhpa and as online supplemental file 3.

bmjopen-2021-050717supp003.pdf (290.2KB, pdf)

We will not actively follow up participants. We will collect primary outcome data via NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) records.29 HES variables of interest include the date and attendance outcome of scheduled outpatient appointments; date of accident and emergency department visits; date of inpatient admissions; and any clinical information generated through these visits. We will collect other secondary outcome data via the Combined Homelessness and Information Network (CHAIN) database,30 which is supported by the Greater London Authority and is used by government agencies and selected non-governmental organisations to record interactions with people who sleep on the street or in other areas not designed for habitation. CHAIN variables of interest include HIV prevention, testing and treatment services; hepatitis C and tuberculosis testing and diagnoses; registration with a GP; use of dentist/podiatrist; substance use/harm reduction; support for mental health, housing, welfare and immigration; and contact with police or any aspects of the criminal justice services.

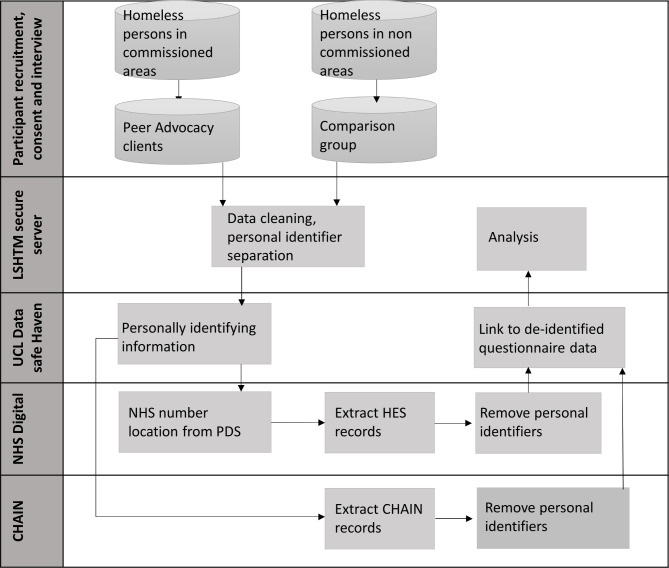

Primary outcome data linkage

As part of the baseline questionnaire, we will collect personal identifying information from all participants, including name, aliases, date of birth, NHS number, and current and past personal and GP addresses, and store these separately from other questionnaire data, though linked with a study identifier (ID). After the cohort’s 12-month follow-up period is complete, the identifying data set will be transmitted to NHS Digital, which will use the Personal Demographics Service to undertake a ‘list clean’ and to identify and complete missing NHS numbers. These NHS numbers are then used to locate relevant HES records and use a two-step deterministic linkage process to ensure the cohort groups are mutually exclusive. NHS Digital will upload a de-identified copy of the records to the University College London Institute of Health Informatics’ Data Safe Haven, which is a robust infrastructure certified for processing and analysing identifiable data according to international and national information security standards (ISO/IEC 27001:2013 and NHS Information Governance Toolkit). Within the Safe Haven, each participant’s HES records are linked to their questionnaire data for analysis. The cohort study processes are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

CHAIN, Combined Homelessness and Information Network; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; LSHTM, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; NHS, National Health Service; PDS, Personal Demographics Service; UCL, University College London.

Co-researchers

We recruited and trained separate sets of co-researchers to conduct baseline study procedures. For English-speaking peer advocacy clients, co-researchers were Groundswell non-peer volunteers who had lived experience of homelessness. For the comparison group and any Polish-speaking participants, co-researchers were research staff who had lived experience of homelessness or experience working with vulnerable groups.

Informed consent

For recruits in both arms, the co-researcher describes the study and its procedures, and gives the recruit an opportunity to ask questions. The co-researcher reads a series of statements off the informed consent form, including a statement that researchers will extract participants’ HES records, and are required to agree with each statement as a condition of participation. Recruits are asked but not required to agree with one statement about researcher’s use of de-identified CHAIN records. The co-researcher documents informed consent or the reason for declining consent on the tablet device. For recruits with uncertain level of cognitive ability, the co-researcher can request witnessing of the informed consent process by a key worker. On completion of the questionnaire, as a token of appreciation, the co-researcher will send a £10 grocery voucher via email or text message to the participant or a key worker of the participant’s choosing, with a copy of the Pavement magazine.25 In the case of face-to-face interviews, participants will be offered cash reimbursement. Participants in the comparison arm will be referred to key workers in case urgent health or welfare needs are identified during the course of the interview.

Intervention

The Peer Advocacy programme has been described above. Participants in the client arm of the study receive the same type and level of peer advocacy as clients who decline to participate, and are not compelled to remain clients. Participants in the comparison arm of the study are not prohibited from becoming a Peer Advocacy client if they have the opportunity to do so, for example, by moving to a hostel in an area where Groundswell has been commissioned.

Analysis

We will estimate the difference in the number of missed outpatient appointment over 12 months for peer advocacy clients versus comparison participants using Poisson regression, with the number of missed appointments as the dependent variable and study arm as independent variable. To balance the arms for differences in baseline characteristics, we will use inverse probability of treatment weights in the regression model. The treatment weights (also known as propensity scores) are calculated from a logistic regression model with arm as the dependent variable (0/1), and as independent variables, we will consider measures thought to be predictive of joining peer advocacy which were collected from the questionnaire (eg, age, gender, national origin, health problems, depression/anxiety screening score, last sleeping location, barriers to healthcare, substance use and history of incarceration), and from historic HES data (eg, number of missed outpatient visits and diagnoses) subject to linkage. After calculating the treatment weights, we will assess the weight-adjusted standardised differences for participants’ characteristics and revise the propensity score model as needed to achieve better balance across arms (eg, by adding quadratic and interaction terms, and trimming/truncating weights).

If more than 5% of outcome data are missing, which will occur if we are unable to link a participant to HES, we will use multiple imputation with chained outcomes and include all variables from the main regression and propensity score models. When there is sufficient variation in the data, we will consider exploratory subgroup analysis, for example, estimating whether the effect of peer advocacy on missed appointment differs by gender, nationality or morbidity. We will follow the steps as described above and will stratify propensity score estimates within each subgroup.

We will use similar approaches for analyses of the other primary outcomes (ie, number of accident and emergency visits and number of inpatient admissions), though may use logistic regression with a binary outcome instead of Poisson regression when the zero counts are inflated. We will detail analyses for objectives 4 and 5, and for secondary outcomes from the CHAIN data set in future reports.

Economic evaluation

For the economic evaluation, we aim to estimate the costs and cost-effectiveness of peer advocacy on attendance at health services and the health and social welfare of homeless populations (objective 6).

Data collection

We will assess the cost-effectiveness of the peer advocacy, drawing on the impact estimates from the quantitative study. Both health and non-health care costs will be included in addition to the costs of the intervention. We will interview staff and review project documents and programme data to define the range of activities to be costed in order to cost the intervention. Costs will include those that are fixed (training and overheads) and variable (salaries to cover time spent in peer training and with clients). We will follow standard methods for costing, including all costs regardless of payer, and estimate a shadow cost where the price does not represent the values of resources.31 NHS resource use will be estimated using the linked HES data and NHS reference costs will be used to value them. Resource items to be included will be planned and unplanned hospital visits. Self-reported non-NHS resource use, such as contacts with drug/alcohol services, will also be costed using information available from the Personal Social Services Research Unit.

Analysis

The results will be presented as the costs and outcomes for the peer and comparison arms separately rather than aggregating them into a single statistic (ie, incremental cost per quality adjusted life year). We will therefore perform a cost–consequence analysis, which follows the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence evaluation approach for public health interventions;32 cost-consequence analysis is an appropriate form of evaluation to use when it is thought that quality-adjusted life years are unlikely to capture all the intervention benefits of interest. We do not intend to supplement the analysis with decision modelling. The robustness of the results will be assessed using appropriate forms of sensitivity analysis.

Programmatic study

We will collate programmatic data collected by Groundswell, including: (1) nature and frequency of contact with peer advocate; (2) location of recruitment; (3) demographic characteristics of clients and peer advocates; (4) type of health condition (using International Classification of Diseases-10 chapter headings); and (5) location of health appointment, whether the appointments took place and the reason for cancellation (objective 7). These data will also enable us to define our exposure to peer advocacy as well as inform our quantitative sampling strategy.

Data will be analysed descriptively to assess (1) the fidelity (the extent to which the intervention is delivering what it set out to); (2) dose (the intensity in which the intervention is delivered); and (3) reach (what proportion of the population are in contact with the intervention) in line with published recommendations on utilising routine data for process evaluations.33 We will link to the quantitative questionnaire data for descriptive analysis of clients, for example, characteristics of once-off versus recurrent clients.

Ethics and dissemination

Study-wide ethics approval has been granted by the Dulwich Research Ethics Committee (IRAS 271312) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s Ethics Committee (Ref: 18021), both in the UK.

The main ethical and safety considerations for the study concerned loss of confidentiality and feelings of distress. To minimise feelings of distress (eg, for the section on personal violence and substance dependency) we pilot tested our questionnaire extensively, including with people with lived experience. In response to feedback, we added prompts with reminders about the ability to refuse questions, the rationale for including those questions, and that data would only be used for analysis by the research team. Participants in any study component were told during the informed consent process that any threats to harm themselves or another person would be taken seriously; research staff would contact a key worker or emergency services as appropriate, and emphasise they would prefer to do so with the assent of the participant.

Quantitative and economic study: confidentiality protections

The ODK app used to administer the questionnaire encrypts data on completion. Data are transmitted to a secure server at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), with decryption ability limited to SDR and LP. Personal identifying information are stored separately from other questionnaire responses, linked with a study ID. The personally identifying data set will be uploaded to the University College London Institute of Health Informatics’ Data Safe Haven. Once HES data are linked, personal identifiers are removed, the study ID is maintained, and the data set is sent back to the Safe Haven for linkage to questionnaire data and analysis. No data are handed over to the NHS other than personal identifiers necessary for linkage.

A similar process will be used for CHAIN data set linkage: we will send a data set of only personal identifiers and study ID to CHAIN administrators. The administrators will link this data set with requested outcome data, remove the personal identifiers, keep the study ID and send the resulting data set to LSHTM for re-linkage with the other questionnaire data. These processes are summarised in figure 1.

Qualitative study: confidentiality protections

Interviews will be recorded on an encrypted device and uploaded to an encrypted container accessible only to AG and PJA. Recordings will be transcribed and stored using identification numbers rather than referring to participants’ names, and any potential identifying information will be removed from the transcript content itself.

Dissemination plan

We will post updates on the project website at www.lshtm.ac.uk/hhpa, where we will make available data collection instruments, standard operating procedures, training manuals and a data sharing policy. We have contributed to a feature about this project in the Pavement magazine,34 which is distributed freely in hostels and day centres across London. We plan to submit four manuscripts for peer review: impact evaluation, qualitative study, economic study and integrated analyses, including programmatic data. As it is not practicable to recontact our individual participants, we plan two dissemination workshops specifically for people who are homeless to report on preliminary and end-of-project findings. At these workshops, we aim to get feedback, reflect on findings and solicit proposals for changes to policy and practice. We will carry forward these proposals with our findings at two more dissemination events: one with policy makers and general service providers, another with homeless specialist service providers. Throughout the duration of the project, we will approach our study steering committee for further advice and support for dissemination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the Study Steering Committee, including Alex Marshall and Louisa McDonald of Groundswell, Suzanne Fitzpatrick of Heriot-Watt University, and Mark Lunt of Manchester University. We thank Jocelyn Elmes and Chrissy H Roberts of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); Mani Cudjoe, Martin Murphy and the Peer Advocates at Groundswell; our co-researchers; and our participants. Open Data Kit servers and support were provided by the LSHTM Global Health Analytics Group (odk.lshtm.ac.uk).

Footnotes

Twitter: @rob_aldridge

Contributors: SDR drafted the manuscript. AG, AM, RWA, AS and AH conceived the study with LP, the principal investigator. SDR, AG, PJA, PH, EW, AM, KB, MB, RWA, SL, DM, AS, AH and LP edited the draft manuscript and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding: This work was supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research (PHR Project 17/44/40).

Disclaimer: The National Institute for Health Research had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data or decision to submit results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer-reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Fransham M, Dorling D. Homelessness and public health. BMJ 2018;360:k214. 10.1136/bmj.k214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelter . This is England: a picture of homelessness in 2019. London, UK: Shelter, 2019. https://england.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/policy_and_research/policy_library/policy_library_folder/this_is_england_a_picture_of_homelessness_in_2019 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office for National Statistics . Early insights of how the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic impacted the labour market [Internet], 2020. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/earlyinsightsofhowthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicimpactedthelabourmarket/july2020#authors

- 4.Homeless Link . The unhealthy state of homelessness. Health audit results 2014. London: Homeless Link, 2014. https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/TheunhealthystateofhomelessnessFINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewett N, Halligan A, Boyce T. A general practitioner and nurse led approach to improving hospital care for homeless people. BMJ 2012;345:e5999. 10.1136/bmj.e5999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014;384:1529–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics . Deaths of homeless people in England and Wales: 2018 [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/articles/ukhomelessness/2005to2018

- 8.Harris M. Normalised pain and severe health care delay among people who inject drugs in London: adapting cultural safety principles to promote care. Soc Sci Med 2020;260:113183. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunner E, Chandan SK, Marwick S, et al. Provision and accessibility of primary healthcare services for people who are homeless: a qualitative study of patient perspectives in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e526–36. 10.3399/bjgp19X704633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.et alEdmunds A, Hill P-S, McCormick B. Healthcare for Single Homeless People [Internet]. Office of the Chief Analyst, Department of Health, 2010. Available: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130123201505/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_114250

- 11.Department of Health of Great Britain . Inclusion health, improving the way we meet the primary health care needs of the socially excluded. Cabinet Office Social Exclusion Task force, Dept of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW, et al. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. Lancet 2018;391:266-280. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker SL, Maguire N. Experts by experience: peer support and its use with the homeless. Community Ment Health J 2017;53:598–612. 10.1007/s10597-017-0102-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy K, Burton M, Miescher A, et al. Mentorship for alcohol problems (MAP): a peer to peer modular intervention for outpatients. Alcohol Alcohol 2012;47:42–7. 10.1093/alcalc/agr136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felton CJ, Stastny P, Shern DL, et al. Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 1995;46:1037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galanter M, Dermatis H, Egelko S, et al. Homelessness and mental illness in a Professional- and Peer-Led cocaine treatment clinic. PS 1998;49:533–5. 10.1176/ps.49.4.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boisvert RA, Martin LM, Grosek M, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-support community in addiction recovery: participation as intervention. Occup Ther Int 2008;15:205–20. 10.1002/oti.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlayson S, Boelman V, Young R, et al. How homeless health peer advocacy reduces health inequalities. London: Young Foundation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whyte WF. Advancing scientific knowledge through participatory action research. Sociol Forum 1989;4:367–85. 10.1007/BF01115015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Public Health England . Homelessness: applying All Our Health [Internet]. gov.uk, 2019. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/homelessness-applying-all-our-health/homelessness-applying-all-our-health

- 21.Combined Homelessness and Information Network . Chain annual Bulletin greater London 2019/20. London, UK: Greater London Authority, 2020. https://data.london.gov.uk/download/chain-reports/b2d0a4d2-17f4-4bdc-b263-9d7395a3d3c7/GreaterLondonbulletin2019-20.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:321–32. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawford S, Bath N. Peer support models for people with a history of injecting drug use undertaking assessment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(Suppl 2):S75–9. 10.1093/cid/cit297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998: 312. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Pavement [Internet], 2020. Available: https://www.thepavement.org.uk/services

- 26.Tavory I, Timmermans S. Abductive analysis: theorizing qualitative research. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014: 172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research [Internet], 2018. Available: https://nls.ldls.org.uk/welcome.html?ark:/81055/vdc_100054735706.0x000001

- 28.et alBrodie C, Carter S, Perera G. Rough Sleepers: health and healthcare [Internet]. Inner North West London Primary Care Trusts & Broadway, 2013. Available: https://www.jsna.info/sites/default/files/Rough%20Sleepers%20Health%20and%20Healthcare%20Summary.pdf

- 29.NHS Digital . Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) [Internet]. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/hospital-episode-statistics

- 30.Greater London Authority . Rough sleeping in London (CHAIN reports) [Internet]. Available: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/chain-reports

- 31.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . How NICE measures value for money in relation to public health interventions [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/guidance/LGB10-Briefing-20150126.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Pavement Team . What’s the point of evaluating research on health care and homelessness? The Pavement [Internet], 2021. Available: https://www.thepavement.org.uk/stories/2495

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050717supp001.pdf (854.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050717supp002.pdf (122.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050717supp003.pdf (290.2KB, pdf)