Abstract

Objective.

To develop an evidence-based guideline for the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), as a collaboration between the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF).

Methods.

We identified critical outcomes in PsA and clinically relevant PICO (population/intervention/comparator/outcomes) questions. A Literature Review Team performed a systematic literature review to summarize evidence supporting the benefits and harms of available pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies for PsA. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology was used to rate the quality of the evidence. A voting panel, including rheumatologists, dermatologists, other health professionals, and patients, achieved consensus on the direction and the strength of the recommendations.

Results.

The guideline covers the management of active PsA in patients who are treatment-naive and those who con tinue to have active PsA despite treatment, and addresses the use of oral small molecules, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, interleukin-12/23 inhibitors (IL-12/23i), IL-17 inhibitors, CTLA4-Ig (abatacept), and a JAK inhibitor (tofaciti nib). We also developed recommendations for psoriatic spondylitis, predominant enthesitis, and treatment in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, or serious infections. We formulated recommendations for a treat-to-target strategy, vaccinations, and nonpharmacologic therapies. Six percent of the recommendations were strong and 94% conditional, indicating the importance of active discussion between the health care provider and the patient to choose the optimal treatment.

Conclusion.

The 2018 ACR/NPF PsA guideline serves as a tool for health care providers and patients in the selection of appropriate therapy in common clinical scenarios. Best treatment decisions consider each individual patient situation. The guideline is not meant to be proscriptive and should not be used to limit treatment options for patients with PsA.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disease associated with psoriasis, manifesting most commonly with peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, and spondylitis. Nail lesions, including pitting and onycholysis, occur in ~80–90% of patients with PsA. The incidence of PsA is ~6 per 100,000 per year, and the prevalence is ~1–2 per 1,000 in the general population (1). The annual incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis is 2.7% (2), and the reported prevalence of PsA among patients with psoriasis has varied between 6% and 41% (1). In the majority of patients the skin symptoms develop first, followed by the arthritis; however, in some patients the skin and joint symptoms present at the same time, and in 10–15% the arthritis presents first (2).

PsA affects men and women equally. The distribution of the peripheral arthritis varies from asymmetric oligoarthritis (involving ≤4 joints) to symmetric polyarthritis (involving ≥5 joints). Distal interphalangeal joints are commonly affected and, in some patients, are the only affected joints. Axial disease, when present, usually occurs together with peripheral arthritis. Some patients present with rapidly progressive and destructive PsA–arthritis mutilans. PsA is associated with an adverse impact on health-related quality of life (3–5) and high health care costs and utilization (6,7). Greater disease activity is associated with progressive joint damage and higher mortality (8–11). Early identification of PsA and early initiation of therapy are important for improving long-term outcomes (12).

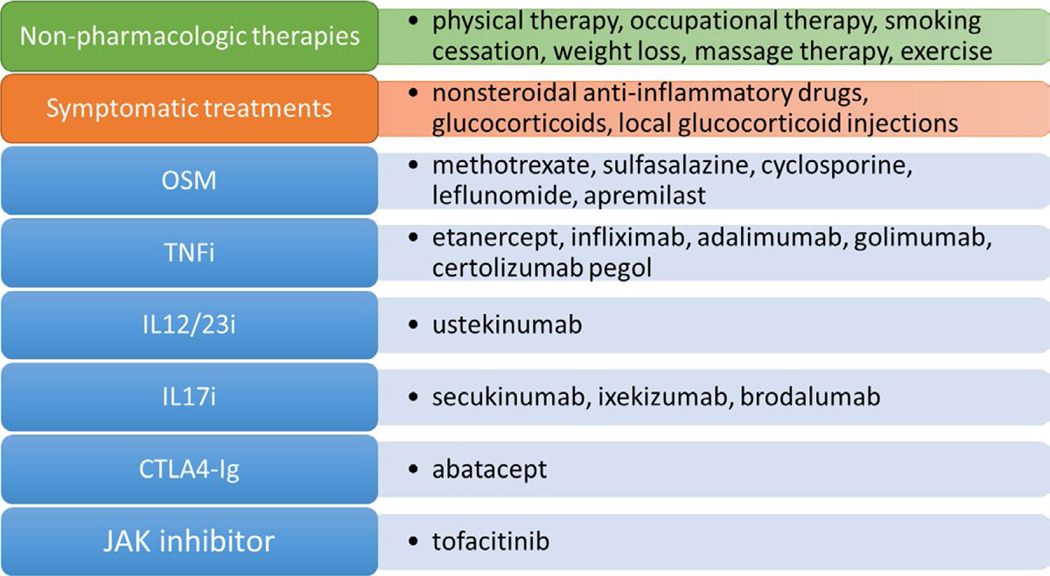

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment can ameliorate PsA symptoms and can occasionally result in disease remission (Figure 1). Clinicians and patients can now choose from a wide variety of pharmacologic therapies, including symptomatic treatments such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and intraarticular injections, as well as immunomodulatory therapies.

Figure 1.

Pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, and symptomatic therapies for psoriatic arthritis. Pharmacologic therapies are displayed in the blue boxes and include oral small molecules (OSMs), tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) biologics, interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) biologics, an IL-12/23i biologic, CTLA4-immunoglobulin, and a JAK inhibitor. While there are numerous nonpharmacologic therapies available, 6 of these are addressed in this guideline. Symptomatic therapies include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, systemic glucocorticoids, and local glucocorticoid injections. Systemic glucocorticoids or local injections are not addressed in this guideline.

The presentation of PsA is heterogeneous, and health care providers frequently face challenges when considering the various treatment options. Our objective was to develop evidence-based treatment recommendations for the management of active PsA in adults, using pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies. These PsA treatment recommendations can help guide both clinicians and patients to arrive at optimal management decisions.

METHODS

Methodology overview.

This guideline followed the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline development process (http://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines). This process includes using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology (13–15) (www.gradeworkinggroup.org) to rate the quality of the available evidence and to develop the recommendations. ACR policy guided disclosures and the management of conflicts of interest. The full methods are presented in detail in Supplementary Appendix 1, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract.

This work involved 4 teams selected by the ACR Quality of Care Committee after reviewing individual and group volunteer applications in response to an open request for proposals announcement: 1) a Core Leadership Team, which supervised and coordinated the project and drafted the clinical questions and manuscript; 2) a Literature Review Team, which completed the literature search and abstraction; 3) an Expert Panel, composed of patients, patient advocates, rheumatologists, dermatologists, 1 dermatologist-rheumatologist, and 1 rheumatology nurse practitioner, which developed the clinical questions (PICO [population/intervention/comparator/outcomes] questions) and decided on the scope of the guideline project; and 4) a Voting Panel, which included rheumatologists, 1 dermatologist, 1 dermatologist-rheumatologist, 1 rheumatology physician assistant, and 2 patients (1 of whom was also a physical therapist), who provided input from the patient perspective and voted on the recommendations. Additionally, a Patient Panel consisting of 9 adults with PsA reviewed the evidence and provided input on their values and preferences, which was reviewed before discussion of each section of PsA management (e.g., treatment-naive, treated, comorbidities), and was incorporated into discussions and formulation of recommendations. Supplementary Appendix 2 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract) presents rosters of the team and panel members. In accordance with ACR policy, the principal investigator and the leader of the literature review team were free of conflicts, and within each team, >50% of the members were free of conflicts.

Framework for the PsA guideline development and scope of the guideline.

Because there are numerous topics within PsA that could be addressed, at the beginning of the process the guideline panels made several decisions regarding the focus of this guideline and how to define aspects of the disease (e.g., active disease). At an initial scoping meeting, the Voting Panel and Expert Panel agreed that the project would include the management of patients with active PsA, defined as symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient and judged by the examining health care provider to be due to PsA based on the presence of at least 1 of the following: actively inflamed joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and/or extraarticular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The health care provider may, in deciding if symptoms are due to active PsA, consider information beyond the core information from the history and physical examination, such as inflammation markers (C-reactive protein [CRP] or erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) and imaging results. At the scoping meeting, the panels decided that the guideline would address both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies for the treatment of PsA. We examined evidence regarding vaccinations, treatment in the presence of common comorbidities, and implementing a treat-to-target strategy.

In addressing pharmacologic therapies, we focused on immunomodulatory agents for long-term management rather than addressing acute symptom management (i.e., through intraarticular injections and the use of systemic glucocorticoids). Tofacitinib and ixekizumab were submitted for review and potential approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at the time of formulation of this guideline (16,17) and for this reason, these drugs were addressed in the guideline. Both drugs have been approved for PsA since then (18,19). Tofacitinib is not included within the oral small molecules (OSM) category since its benefit/risk profile differs from that of the rest of the OSMs, especially with regard to risks (20–22), and consistent with its being considered separately in other treatment guidelines (23,24). Additionally, the panel addressed alternatives in patient subpopulations (e.g., patients with predominant enthesitis, axial disease, dactylitis, comorbidities), and greater versus lesser disease severity.

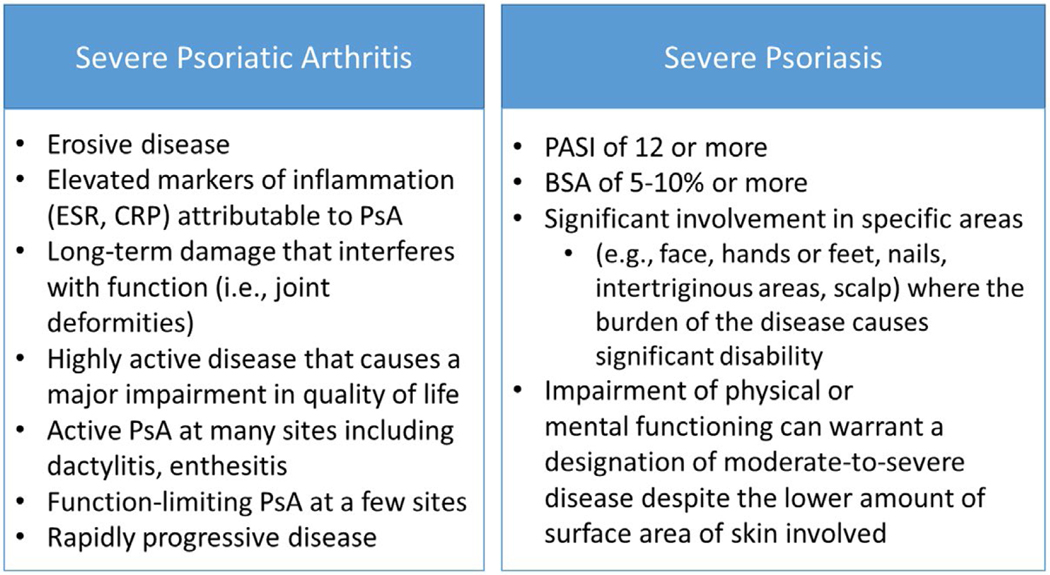

There are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity in PsA or psoriasis. Thus, health care providers and patients should judge PsA and psoriasis severity on a case-by-case basis. For the purpose of these recommendations, severity includes not only the level of disease activity at a given time point, but also the presence or absence of poor prognostic factors and long-term damage. Examples of severe PsA disease include the presence of 1 or more of the following: a poor prognostic factor (erosive disease, dactylitis, elevated levels of inflammation markers such as ESR and CRP attributable to PsA), long-term damage that interferes with function (e.g., joint deformities), highly active disease that causes a major impairment in quality of life (i.e., active psoriatic inflammatory disease at many sites [including dactylitis, enthesitis] or function-limiting inflammatory disease at few sites), and rapidly progressive disease (Figure 2). In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) (25) score of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. However, because it is cumbersome, physicians seldom use the PASI in clinical practice. Examples of definitions of severe PsA and severe psoriasis are shown in Figure 2. Finally, because the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) and American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing psoriasis treatment guidelines, the treatment of skin psoriasis separately from the inflammatory arthritis was not included in the current ACR/NPF PsA guideline.

Figure 2.

Examples of “severe” psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and psoriasis. The guideline development group defined severe PsA and psoriasis as the presence of 1 or more of the items listed. This is not a formal definition. There have been many definitions of severe psoriasis used over time—the items here are adapted from the 2007 National Psoriasis Foundation expert consensus statement for moderate-to-severe psoriasis (68). In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of ≥12 and a body surface area (BSA) score of ≥10 (25). ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP = C-reactive protein.

Systematic synthesis of the literature.

Systematic searches of the published English-language literature included Ovid Medline, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Health Technology Assessments) from the beginning of each database through November 15, 2016 (Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract); we conducted updated searches on May 2, 2017 and again on March 8, 2018. DistillerSR software (https://distillercer.com/products/distillersr-systematic-reviewsoftware/) (Supplementary Appendix 4; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract) was used to facilitate duplicate screening of literature search results. Reviewers entered extracted data into RevMan software (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman), and evaluated the risk of bias in primary studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (http://handbook.cochrane.org/). We exported RevMan files into GRADEpro software to formulate a GRADE summary of findings table (Supplementary Appendix 5; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract) for each PICO question (26). Additionally, a network meta-analysis was performed when sufficient studies were available. GRADE criteria provided the framework for judging the overall quality of evidence (13).

The panels chose the critical outcomes for all comparisons at the initial scoping; these included the American College of Rheumatology 20% response criteria (ACR20) (the primary outcome for most PsA clinical trials), the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (a measure of physical function), the PASI 75% response criteria (PASI75) (a measure of skin psoriasis improvement), and serious infections. Both the ACR20 and the PASI75 are accepted outcome measures specified by regulatory agencies, including the US FDA, for the approval of treatments for PsA (27). Serious infections are among the issues of greatest concern for patients and physicians when selecting among therapies. Other specific harms (e.g., liver toxicity with methotrexate [MTX]) were included as critical outcomes for individual comparisons. We included other outcomes, such as total infections (regardless of severity), when appropriate.

Moving from evidence to recommendations.

GRADE methodology specifies that panels make recommendations based on the balance of benefits and harms, the quality of the evidence (i.e., confidence in effect estimates), and patients’ values and preferences. Deciding on the balance between desirable and undesirable outcomes requires estimating the relative value patients place on those outcomes. When the literature provided very limited guidance, the experience of the Voting Panel members (including physicians, a rheumatology physician assistant, and the 2 patients present) in managing the relevant cases and issues became an important source of evidence. Values and preferences, crucial to all recommendations, derived from input from the members of the Patient Panel were particularly salient in such situations. GRADE methodology allows the panels the possibility of not coming to a decision, and a summary of the discussion is noted in such cases. However, during the development of this guideline, the Voting Panel came to a conclusion in each case scenario, and such a situation did not arise.

Consensus building.

The Voting Panel voted on the direction and strength of the recommendation related to each PICO question. Recommendations required a 70% level of agreement, as used previously in other similar processes (28) and in the previous ACR guidelines (23,29,30); if 70% agreement was not achieved during an initial vote, the panel members held additional discussions before revoting. For all conditional recommendations, a written explanation is provided, describing the reasons for the decision and conditions under which the alternative choice may be preferable.

Moving from recommendations to practice.

These recommendations are designed to help health care providers work with patients in selecting therapies. The presence or absence of concomitantly occurring conditions, such as IBD, uveitis, diabetes, and serious infections, and the knowledge of previous therapies, influence decisions regarding optimal management. In the context of PsA, the physical examination, which is also required for selecting therapy, includes assessment of the peripheral joints (including for dactylitis), the entheses, the spine, the skin, and the nails. Health care providers and patients must take into consideration all active disease domains, comorbidities, and the patient’s functional status in choosing the optimal therapy for an individual at a given point in time.

RESULTS/RECOMMENDATIONS

How to interpret the recommendations

A strong recommendation means that the panel was confident that the desirable effects of following the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects (or vice versa), so the course of action would apply to all or almost all patients, and only a small proportion of clinicians/patients not wanting to follow the recommendation. We use the phrase “should use” or “should be used” for strong recommendations.

A conditional recommendation means that the panel believed the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but a small proportion of clinicians/patients may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of this, conditional recommendations are preference sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. We use the phrase “is recommended over” or “is/would be recommended” for conditional recommendations. We specify conditions under which the less preferred drug may be used by using the phrase “may be used” or “may consider” or “Y (less preferred drug) may be used instead of X (preferred drug)” or “may consider Y instead of X (preferred drug)” for conditional recommendations.

Conditional recommendations were usually based on low- to very-low-quality evidence (in rare instances, moderate-quality evidence). Strong recommendations were typically based on moderate- or high-quality evidence.

For each recommendation, Supplementary Appendix 5 (on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40726/abstract) provides details regarding the PICO questions and the GRADE evidence tables.

In each case, the Voting Panel’s recommendation was based on a judgment of the most likely net benefit, i.e.,1) more benefit with the medication conditionally recommended with no difference in harms between the medications being compared (e.g., choosing a TNFi over OSMs in treatment-naive patients) or 2) less harm with the medication conditionally recommended and no difference in benefit (e.g., choosing abatacept over a TNFi in patients at risk of or with a history of previous infections, or preferring a different OSM over MTX in patients with PsA and diabetes due to an increased risk of liver toxicity in this subpopulation).

This is an evidence-based guideline, in that we explicitly use the best evidence available and present that in a transparent manner for the clinician reader/user (31,32). In some instances, this includes a randomized trial directly comparing the interventions under consideration. In other cases, in the absence of any published evidence, the best evidence comes from the collective experience of the Voting Panel and patient panel members, which in the GRADE system is rated as “very-low-quality” evidence.

Recommendations for pharmacologic interventions

Active PsA in treatment-naive patients (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Table 1.

Recommendations for the initial treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis who are OSM- and other treatment–naive (PICOs 9–15)*

| Level of evidence (evidence [refs.] reviewed)† | |

|---|---|

| In OSM- and other treatment–naive patients with active PsA, | |

| 1. Treat with a TNFi biologic over an OSM (MTX, SSZ, LEF, CSA, or APR) (PICO 10a–e) | Low (53–66) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider an OSM if the patient does not have severe PsA,‡ does not have severe psoriasis,§ prefers oral therapy, has concern over starting a biologic as the first therapy, or has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 2. Treat with a TNFi biologic over an IL-17i biologic (PICO 14) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider an IL-17 i biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis or has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 3. Treat with a TNFi biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 13) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low- quality evidence; may consider an IL-12 /23i biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis, prefers less frequent drug administration, or has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 4. Treat with an OSM over an IL-17i biologic (PICO 12) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider an IL- 17 i biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis and/or severe PsA. | |

| 5. Treat with an OSM over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 11) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low- quality evidence; may consider an IL-12 /23i biologic if the patient has concomitant IBD and/or severe psoriasis and/or severe PsA or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 6. Treat with MTX over NSAIDs (PICO 9) | Very low (67) |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low- quality evidence; may consider NSAIDs before starting MTX in patients with less active disease, after careful consideration of cardiovascular risks and renal risks of NSAIDs. | |

| 7. Treat with an IL-17i biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 15) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider an IL-12 /23i biologic if the patient has concomitant IBD or prefers less frequent drug administration. |

Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as disease causing symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining clinician to be due to PsA based on ≥1 of the following: swollen joints, tender joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and extraarticular inflammatory manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Oral small molecules (OSMs) are defined as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine (SSZ), leflunomide (LEF), cyclosporine (CSA), or apremilast (APR) and do not include tofacitinib, which was handled separately since its efficacy/safety profile is much different from that of other OSMs listed above. OSM- and other treatment–naive is defined as naive to treatment with OSMs, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi,) interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i), and IL-12/23i; patients may have received nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and/or other pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

When there were no published studies, we relied on the clinical experience of the panelists, which was designated very-low-quality evidence.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, PsA severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. For the purposes of these recommendations, severity is considered a broader concept than disease activity in that it encompasses the level of disease activity at a given time point, as well as the presence of poor prognostic factors and long-term damage. Examples of severe PsA disease include the presence of ≥1 of the following: a poor prognostic factor (erosive disease, elevated levels of inflammation markers such as C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate attributable to PsA), long-term damage that interferes with function (e.g., joint deformities, vision loss), highly active disease that causes major impairment in quality of life (i.e., active psoriatic inflammatory disease at many sites [including dactylitis, enthesitis] or function-limiting inflammatory disease at few sites), and rapidly progressive disease.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, psoriasis severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (25) of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. In clinical practice, however, the PASI tool is not standardly utilized given its cumbersome nature. In 2007, the National Psoriasis Foundation published an expert consensus statement, which defined moderate-to-severe disease as a body surface area of ≥5% (68). In cases in which the involvement is in critical areas, such as the face, hands or feet, nails, intertriginous areas, scalp, or where the burden of the disease causes significant disability or impairment of physical or mental functioning, the disease can be severe despite the lower amount of surface area of skin involved. The need to factor in the unique circumstances of the individual patient is of critical importance, but this threshold provides some guidance in the care of patients.

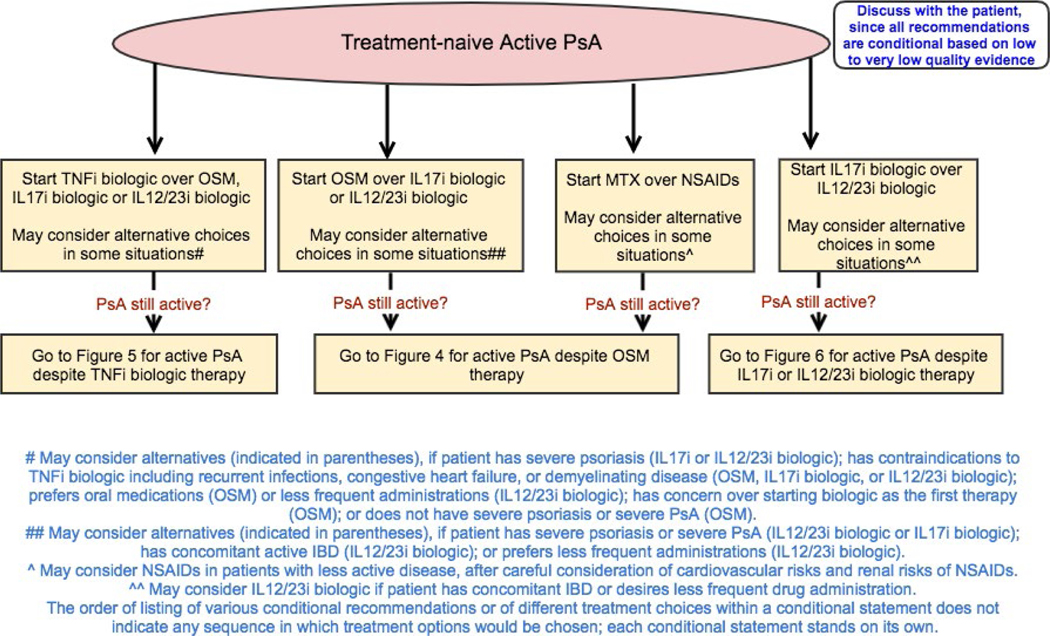

Figure 3.

Recommendations for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who are treatment-naive (no exposure to oral small molecules [OSMs] or other treatments). All recommendations are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence. A conditional recommendation means that the panel believed the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but some may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of this, conditional recommendations are preference sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. Due to the complexity of management of active PsA, not all clinical situations and choices could be depicted in this flow chart, and therefore we show only the key recommendations. For a complete list of recommendations, please refer to the Results section of the text. For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, see Table 1 and the related section in the Results. This figure is derived from recommendations based on PICO (population/intervention/comparator/outcomes) questions that are based on the common clinical situations. Active PsA was defined as symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining health care provider to be due to PsA based on the presence of at least 1 of the following: actively inflamed joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and/or extraarticular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

All recommendations for treatment-naive patients with active PsA are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence.

In treatment-naive patients with active PsA, a TNFi biologic agent is recommended over an OSM as a first-line option (Table 1). OSMs may be used instead of a TNFi biologic in patients without severe PsA and without severe psoriasis (as defined in Methods and Figure 2; final determination of severity to be made by the patient and the health care provider), those who prefer an oral drug instead of parenteral therapy, or those with contraindications to TNFi treatment, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease.

For treatment-naive patients with active PsA, the use of a TNFi biologic or OSM is recommended over an interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) or IL-12/23i biologic. An IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic may be used instead of TNFi biologics in patients with severe psoriasis or contraindications to TNFi biologics, and may be used instead of OSMs in patients with severe psoriasis or severe PsA. MTX is recommended over NSAIDs in treatment-naive patients with active PsA. NSAIDs may be used instead of MTX after consideration of possible contraindications and side effect profile in patients without evidence of severe PsA or severe psoriasis and in those at risk for liver toxicity (Table 1 and Figure 3). An IL-17i biologic is recommended over an IL-12/23i biologic. IL-12/23i biologics may be used in patients who have concomitant IBD or who desire less frequent drug administration.

Active PsA despite treatment with an OSM (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Table 2.

Recommendations for treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite treatment with an OSM (PICOs 16–25; 67–69; 76–78)*

| Level of evidence (evidence [refs.] reviewed)† | |

|---|---|

| In adult patients with active PsA despite treatment with an OSM, | |

| 1. Switch to a TNFi biologic over a different OSM (PICO 23) | Moderate (62–66, 69–86) |

| Conditional recommendation based on moderate- quality evidence; may consider switching to a different OSM if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, if the patient prefers an oral versus parenteral therapy, or in patients without evidence of severe PsA‡ or severe psoriasis.§ | |

| 2. Switch to a TNFi biologic over an IL-17i biologic (PICO 17) | Moderate (62–66, 72–78, 87–97) |

| Conditional recommendation based on moderate- quality evidence; may consider an IL- 17i if the patient has severe psoriasis and/or has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, and/or a family history of demyelinating disease such as multiple sclerosis. | |

| 3. Switch to a TNFi biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 16) | Moderate (62–66, 72–78, 97–102) |

| Conditional recommendation based on moderate- quality evidence; may consider an IL- 12/23i if the patient has severe psoriasis and/or contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 4. Switch to a TNFi biologic over abatacept (PICO 67) | Low (62–66, 72–78, 103, 104) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider abatacept if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 5. Switch to a TNFi biologic over tofacitinib (PICO 76) | Low (62–66, 72–78, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider tofacitinib if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or prefers oral medication. | |

| 6. Switch to an IL-17i over a different OSM (PICO 25) | Low (79–87, 89–95) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switch- ing to a different OSM if the patient prefers an oral versus parenteral therapy or in patients without evidence of severe PsA or severe psoriasis. | |

| 7. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 18) | Moderate (87, 89–95, 98–100, 106, 107) |

| Conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence; may consider an IL-12 /23i biologic if the patient has concomitant IBD or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 8. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over abatacept (PICO 69) | Low (89–95, 103, 104) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider abata- cept in patients with recurrent or serious infections. | |

| 9. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over tofacitinib (PICO 78) | Low (89–95, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider tofacitinib if the patient prefers an oral therapy or has a history of recurrent Candida infections. | |

| 10. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over a different OSM (PICO 24) | Low (79–86, 98–100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switch- ing to a different OSM if the patient prefers an oral versus parenteral therapy or in patients without evidence of severe PsA or severe psoriasis. | |

| 11. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over abatacept (PICO 68) | Low (98–100, 103, 104) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider abata- cept in patients with recurrent or serious infections. | |

| 12. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over tofacitinib (PICO 77) | Low (98–100, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider tofaci- tinib if the patient prefers an oral therapy. | |

| 13. Add apremilast to current OSM therapy over switching to apremilast (PICO 22b) | Low (83, 84, 108) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider switching to apremilast if the patient has intolerable side effects with the current OSM. | |

| 14. Switch to another OSM (except apremilast) over adding another OSM (except apremilast) to current treatment (PICO 22a) | Low (83, 84, 108) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider adding another OSM (except apremilast) to current treatment if the patient has demonstrated partial response to the current OSM. | |

| 15. Switch to a TNFi biologic monotherapy over MTX and a TNFi biologic combi nation therapy (PICO 19) | Low (109–111) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider MTX and TNFi biologic combination therapy if the patient has severe skin manifestations, has had a partial response to current MTX therapy, has concomitant uveitis (since uveitis may respond to MTX therapy), and if the current TNFi biologic is infliximab or adalimumab. | |

| 16. Switch to an IL-17i biologic monotherapy over MTX and an IL-17i biologic combination therapy (PICO 21) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low-quality evidence; may consider MTX and an IL-17 i biologic combination therapy if the patient has severe skin manifestations, has had a partial response to current MTX therapy, or has concomitant uveitis (since uveitis may respond to MTX therapy). | |

| 17. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy over MTX and an IL-12/23i bio logic combination therapy (PICO 20) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low- quality evidence; may consider MTX and an IL-12 /23i biologic combination therapy if the patient has severe skin manifestations, has had a partial response to current MTX therapy, or has concomitant uveitis (since uveitis may respond to MTX therapy). |

Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as disease causing symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining clinician to be due to PsA based on ≥1 of the following: swollen joints, tender joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and extraarticular inflammatory manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Oral small molecules (OSMs) are defined as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine, leflunomide, cyclosporine, or apremilast and do not include tofacitinib, which was handled separately since its efficacy/safety profile is much different from that of other OSMs listed above. TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor.

When there were no published studies, we relied on the clinical experience of the panelists, which was designated very-low-quality evidence.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, PsA severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. For the purposes of these recommendations, severity is considered a broader concept than disease activity in that it encompasses the level of disease activity at a given time point, as well as the presence of poor prognostic factors and long-term damage. Examples of severe PsA disease include the presence of ≥1 of the following: a poor prognostic factor (erosive disease, elevated levels of inflammation markers such as C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate attributable to PsA), long-term damage that interferes with function (e.g., joint deformities, vision loss), highly active disease that causes major impairment in quality of life (i.e., active psoriatic inflammatory disease at many sites [including dactylitis, enthesitis] or function-limiting inflammatory disease at few sites), and rapidly progressive disease.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, psoriasis severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (25) of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. In clinical practice, however, the PASI tool is not standardly utilized given its cumbersome nature. In 2007, the National Psoriasis Foundation published an expert consensus statement, which defined moderate-to-severe disease as a body surface area of ≥5% (68). In cases in which the involvement is in critical areas, such as the face, hands or feet, nails, intertriginous areas, scalp, or where the burden of the disease causes significant disability or impairment of physical or mental functioning, the disease can be severe despite the lower amount of surface area of skin involved. The need to factor in the unique circum stances of the individual patient is of critical importance, but this threshold provides some guidance in the care of patients.

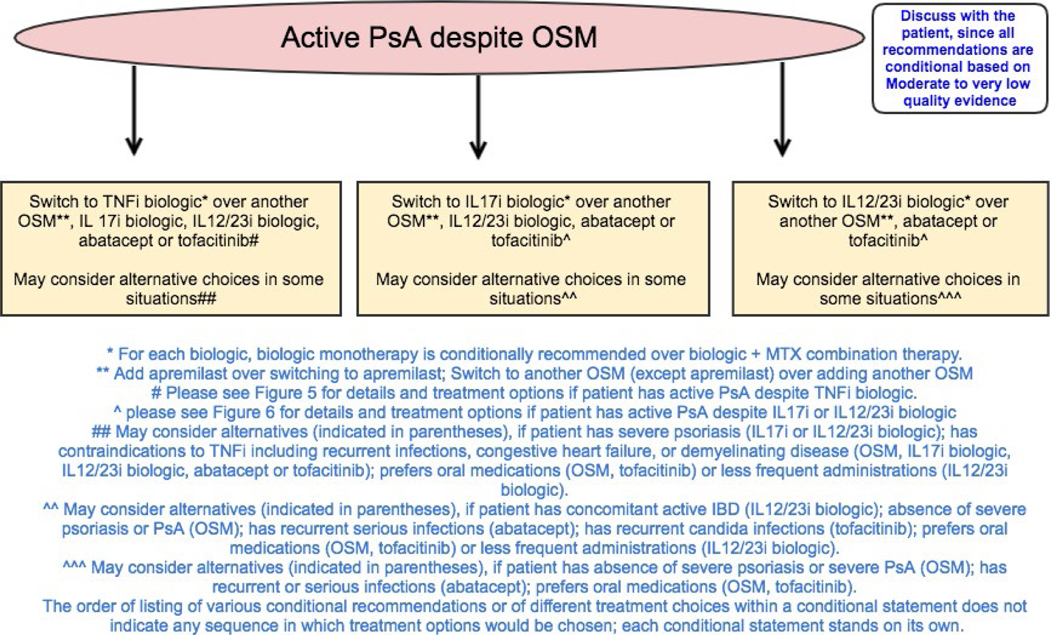

Figure 4.

Recommendations for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) despite treatment with oral small molecules (OSMs). All recommendations are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence. A conditional recommendation means that the panel believed the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but some may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of this, conditional recommendations are preference sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. Due to the complexity of management of active PsA, not all clinical situations and choices could be depicted in this flow chart, and therefore we show only the key recommendations. For a complete list of recommendations, please refer to the Results section of the text. For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, see Table 2 and the related section in the Results. TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate.

All recommendations for patients with active PsA despite treatment with an OSM are conditional based on mostly low- to very-low-quality evidence and, in a few instances, moderate-quality evidence.

In patients with active PsA despite OSM therapy, switching to a TNFi, an IL-17i, or an IL-12/23i biologic is recommended over switching to a different OSM (Table 2 and Figure 4). A different OSM may be used rather than a TNFi, IL-17i, or IL-12/23i in patients who prefer an oral medication or those without evidence of severe PsA or severe psoriasis; a different OSM may be used rather than a TNFi in the presence of contraindications to TNFi biologics. A TNFi biologic is recommended over an IL-17i biologic, an IL-12/23i biologic, abatacept, or tofacitinib. An IL-17i biologic is recommended over an IL-12/23i biologic, abatacept, or tofacitinib. An IL-12/23i is recommended over abatacept or tofacitinib. In patients with contraindications to TNFi agents, an IL-12/23i, an IL-17i, abatacept, or tofacitinib may be used instead of a TNFi. In patients with severe psoriasis, an IL-12/23i or an IL-17i may be used instead of a TNFi. Tofacitinib may be used instead of a TNFi in patients preferring oral medication who do not have severe psoriasis.

Switching to another OSM is recommended over adding another OSM to the current treatment (except in the case of apremilast). Adding another OSM (except apremilast) to current treatment may be considered if the patient has exhibited partial response to the current OSM. Adding apremilast to the current OSM therapy is recommended over switching to apremilast monotherapy since most evidence for benefits of apremilast pertains to apremilast combination therapy. Switching to apremilast monotherapy may be considered instead of apremilast combination therapy if the patient has intolerable side effects with the current OSM.

Biologic monotherapy is recommended over biologic combination therapy with MTX (the most commonly used OSM in combination therapy). When switching to biologic monotherapy, stopping the OSM or tapering of the OSM are both reasonable options and depend on patient and health care provider preferences. A biologic agent in combination with MTX may be used instead of biologic monotherapy if the patient has severe psoriasis, has had a partial response to current MTX therapy, or has concomitant uveitis (since uveitis may respond to MTX therapy), or in patients receiving treatment with a monoclonal antibody TNFi biologic, especially infliximab and adalimumab, to potentially delay or prevent the formation of antidrug antibodies.

Active PsA despite treatment with a TNFi biologic agent as monotherapy or in combination therapy (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Table 3.

Recommendations for treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite treatment with a TNFi biologic, as monotherapy or in combination with MTX (PICOs 26–35; 70–75)*

| Level of evidence (evidence [refs.] reviewed)† | |

|---|---|

| In adult patients with active PsA despite treatment with a TNFi biologic monotherapy, | |

| 1. Switch to a different TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 28) | Low (72, 73, 90–93, 95) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider an IL- 17 i if the patient had a primary TNFi biologic efficacy failure or a TNFi biologic–associated serious adverse event or severe psoriasis.‡ | |

| 2. Switch to a different TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 27) | Low (72, 73, 99, 100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider an IL- 12 /23i if the patient had a primary TNFi biologic efficacy failure or a TNFi biologic–associated serious adverse effect or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 3. Switch to a different TNFi biologic over switching to abatacept (PICO 70) | Low (72, 73, 103, 104) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider abatacept if the patient had a primary TNFi biologic efficacy failure or TNFi biologic–associated serious adverse effect. | |

| 4. Switch to a different TNFi biologic over switching to tofacitinib (PICO 73) | Low (62–66, 72–78, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider tofacitinib if the patient prefers an oral therapy or had a primary TNFi biologic efficacy failure or a TNFi biologic–associated serious adverse effect. | |

| 5. Switch to a different TNFi biologic (with or without MTX) over adding MTX to the same TNFi biologic monotherapy (PICO 26 and 26A) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider adding MTX when patients have demonstrated partial response to the current TNFi biologic therapy, especially if the TNFi biologic is a monoclonal antibody. | |

| 6. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 29) | Low (90–93, 95, 99, 100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider an IL- 12 /23i if the patient has IBD or if the patient prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 7. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over abatacept (PICO 72) | Low (90–93, 95, 103, 104, 112) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider abatacept if the patient prefers IV dosing or in patients with recurrent or serious infections. | |

| 8. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over tofacitinib (PICO 75) | Low (90–93, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider tofacitinib if the patient prefers an oral therapy or in patients with concomitant IBD or a history of recurrent Candida infections. | |

| 9. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over abatacept (PICO 71) | Low (99, 100, 103, 104) |

| Conditional recommendation based on of low-quality evidence; may consider abatacept if the patient prefers IV dosing or in patients with recurrent or serious infections. | |

| 10. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over tofacitinib (PICO 74) | Low (98–100, 105) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider tofacitinib if the patient prefers an oral therapy. | |

| 11. Switch to a different TNFi biologic monotherapy over switching to a different TNFi biologic and MTX combination therapy (PICO 30) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to a TNFi biologic and MTX combination therapy if the current TNFi biologic is infliximab. | |

| 12. Switch to an IL-17i biologic monotherapy over switching to an IL-17i biologic and MTX combination therapy (PICO 32) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL-17i biologic and MTX combination therapy in patients with concomitant uveitis, as uveitis may respond to MTX therapy. | |

| 13. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic and MTX combination therapy (PICO 31) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL-12 /23i biologic and MTX combination therapy if the patient has severe psoriasis. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA despite treatment with a TNFi biologic and MTX combination therapy, | |

| 14. Switch to a different TNFi biologic + MTX over switching to a different TNFi biologic monotherapy (PICO 33) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to a different TNFi biologic monotherapy if the patient has demonstrated MTX-associated adverse events, prefers to receive fewer medications, or perceives MTX as a burden. | |

| 15. Switch to an IL-17i biologic monotherapy over an IL-17i biologic and MTX combina tion therapy (PICO 35) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL-17 i biologic and MTX combination therapy if the patient had had a partial response to the existing regimen or in patients with concomitant uveitis, as uveitis may respond to MTX therapy. Continuing MTX during the transition to an IL-17 i biologic was discussed as potentially beneficial to allow the new therapy time to work. | |

| 16. Switch to IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy over IL-12/23i biologic and MTX combina tion therapy (PICO 34) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL-12 /23i biologic and MTX combination therapy if the patient had had a partial response to the existing regimen or in patients with concomitant uveitis, as uveitis may respond to MTX therapy. Continuing MTX during the transition to an IL-12 /23i biologic was discussed as potentially beneficial to allow the new therapy time to work. |

Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as disease causing symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining clinician to be due to PsA based on ≥1 of the following: swollen joints, tender joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and extraarticular inflammatory manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate; IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor; IV = intravenous.

When there were no published studies, we relied on the clinical experience of the panelists, which was designated very-low-quality evidence.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, psoriasis severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (25) of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. In clinical practice, however, the PASI tool is not standardly utilized given its cumbersome nature. In 2007, the National Psoriasis Foundation published an expert consensus statement, which defined moderate-to-severe disease as a body surface area of ≥5% (68). In cases in which the involvement is in critical areas, such as the face, hands or feet, nails, intertriginous areas, scalp, or where the burden of the disease causes significant disability or impairment of physical or mental functioning, the disease can be severe despite the lower amount of surface area of skin involved. The need to factor in the unique circumstances of the individual patient is of critical importance, but this threshold provides some guidance in the care of patients.

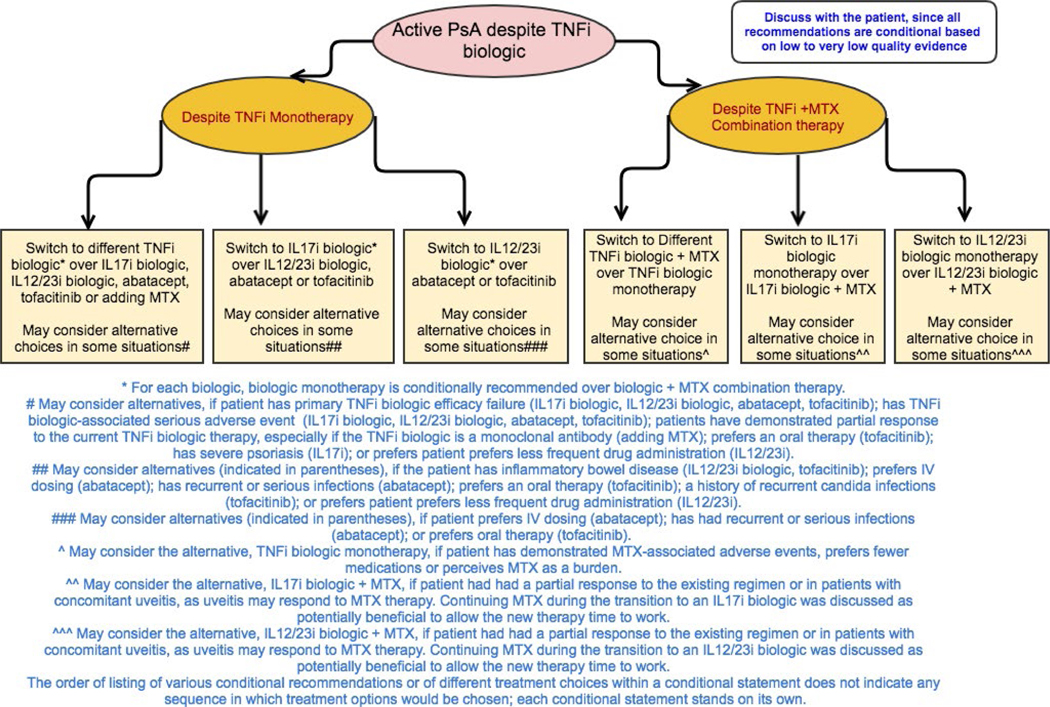

Figure 5.

Recommendations for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) despite treatment with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) as monotherapy or as combination therapy with methotrexate (MTX). All recommendations are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence. A conditional recommendation means that the panel believed the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but some may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of this, conditional recommendations are preference sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. Due to the complexity of management of active PsA, not all clinical situations and choices could be depicted in this flow chart, and therefore we show only the key recommendations. For a complete list of recommendations, please refer to the Results section of the text. For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, see Table 3 and the related section in the Results. IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor; IV = intravenous.

All recommendations for patients with active PsA despite TNFi biologic treatment are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence.

In patients with active PsA despite treatment with TNFi biologic monotherapy, switching to a different TNFi biologic monotherapy is recommended over switching to IL-12/23i biologic, an IL-17i biologic, abatacept, or tofacitinib monotherapy or adding MTX to the current TNFi biologic (Table 3 and Figure 5). An IL-12/23i biologic, IL-17i biologic, abatacept, or tofacitinib may be used instead of a different TNFi biologic monotherapy in the case of a primary TNFi biologic failure or a serious adverse event due to the TNFi biologic. An IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic may be used instead of a different TNFi biologic, particularly in the presence of severe psoriasis. Abatacept may be used instead of a TNFi biologic in patients with recurrent or serious infections in the absence of severe psoriasis, based on indirect evidence of fewer hospitalized infections with abatacept compared to TNFi biologics in a population with rheumatoid arthritis (33). Tofacitinib may be used instead of a TNFi biologic if oral therapy is preferred by the patient.

In patients with active PsA despite treatment with TNFi biologic monotherapy, an IL-17i biologic is recommended over an IL-12/23i biologic, abatacept, or tofacitinib, and an IL-12/23i biologic is recommended over abatacept or tofacitinib. An IL-12/23i biologic may be considered instead of an IL-17i biologic if the patient has IBD or desires less frequent drug administration. Abatacept may be considered instead of an IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic in patients with recurrent or serious infections. Tofacitinib may be considered instead of an IL-17i biologic in patients who prefer oral therapy or have a history of recurrent or severe Candida infections. Tofacitinib may be considered instead of an IL-12/23i biologic in patients who prefer oral therapy. For each biologic (TNFi, IL-12/23i, or IL-17i), monotherapy is recommended over combination with MTX. Combination therapy with biologic and MTX may be used instead of biologic monotherapy in the presence of severe psoriasis, partial response to current MTX therapy, concomitant uveitis (since uveitis may respond to MTX therapy), and if the current TNFi biologic is infliximab or adalimumab (for immunogenicity prevention).

Under circumstances in which combination therapy with a TNFi biologic and MTX is used and active PsA persists, switching to a different TNFi with MTX is recommended over monotherapy with a different TNFi. Continuing MTX treatment during TNFi transition was seen as beneficial because TNFi biologics may have more sustained efficacy when used in combination with MTX, but evidence is limited (34). Monotherapy with a different TNFi biologic may be used if the patient has had MTX-associated adverse events, prefers to receive fewer medications, or perceives MTX treatment as a burden. IL-12/23i or IL-17i biologic monotherapy is recommended over either of these agents in combination with MTX. Combination therapy with an IL-17i or IL-12/23 biologic and MTX may be used instead of switching to biologic monotherapy if the patient had a partial response to the existing regimen and/or has concomitant uveitis that might respond to MTX therapy.

Active PsA despite treatment with an IL-17i biologic agent as monotherapy (Table 4 and Figure 6).

Table 4.

Recommendations for treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite treatment with an IL-17i or an IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy (PICOs 36–43)*

| Level of evidence† | |

|---|---|

| In adult patients with active PsA despite treatment with an IL-17i biologic monotherapy, | |

| 1. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 39) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality-evidence; may consider switching to IL- 12/23i if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 2. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to a different IL-17i biologic (PICO 42) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to a differ ent IL-17 i if the patient had had a secondary efficacy failure to current IL-17 i, or severe psoriasis, or contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 3. Switch to a TNFi biologic over adding MTX to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 41) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider adding MTX to an IL- 17i if the patient had had a partial response to the existing regimen or if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 4. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over switching to a different IL-17i biologic (PICO 43) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to a different IL-17 i if the patient had had a secondary efficacy failure to current IL-17 i or severe psoriasis,‡ or if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 5. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over adding MTX to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 40) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider adding MTX to an IL- 17i if the patient had had a partial response to the existing regimen. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA despite treatment with an IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy, | |

| 6. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 38) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider an IL-17 i if the patient has severe psoriasis or contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 7. Switch to a TNFi biologic over adding MTX to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 36) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider adding MTX in patients in whom the severe psoriasis is not responding to the current therapy, or if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 8. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over adding MTX to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 37). | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider adding MTX in pa- tients with only partial response to the current therapy or in those who potentially have not had enough time to adequately respond. |

Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as disease causing symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining clinician to be due to PsA based on ≥1 of the following: swollen joints, tender joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and extraarticular inflammatory manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. IL-17i = interleukin-17 inhibitor; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate.

When there were no published studies—as was the case with all of the recommendations presented in this table—we relied on the clinical experience of the panelists, which was designated very-low-quality evidence.

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, psoriasis severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (25) of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. In clinical practice, however, the PASI tool is not standardly utilized given its cumbersome nature. In 2007, the National Psoriasis Foundation published an expert consensus statement, which defined moderate-to-severe disease as a body surface area of ≥5% (68). In cases in which the involvement is in critical areas, such as the face, hands or feet, nails, intertriginous areas, scalp, or where the burden of the disease causes significant disability or impairment of physical or mental functioning, the disease can be severe despite the lower amount of surface area of skin involved. The need to factor in the unique circumstances of the individual patient is of critical importance, but this threshold provides some guidance in the care of patients.

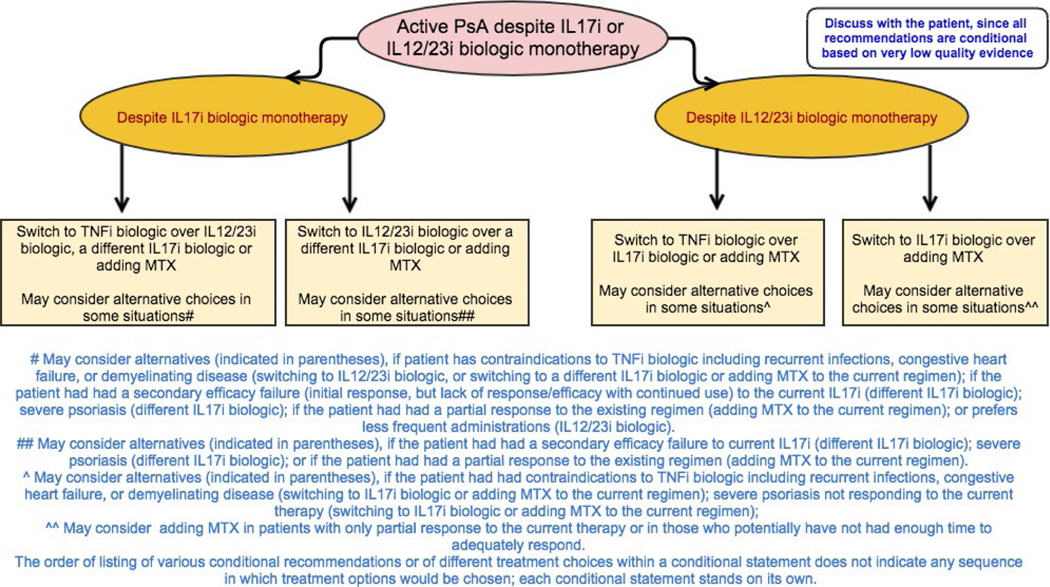

Figure 6.

Recommendations for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) despite treatment with interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) or IL-12/23i biologic monotherapy. All recommendations are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality of evidence. A conditional recommendation means that the panel believed the desirable effects of following the recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, so the course of action would apply to the majority of the patients, but some may not want to follow the recommendation. Because of this, conditional recommendations are preference sensitive and always warrant a shared decision-making approach. Due to the complexity of management of active PsA, not all clinical situations and choices could be depicted in this flow chart, and therefore we show only the key recommendations. For a complete list of recommendations, please refer to the Results section of the text. For the level of evidence supporting each recommendation, see Table 4 and the related section in the Results. TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; MTX = methotrexate.

All recommendations for patients with active PsA despite IL-17i biologic treatment are conditional based on very-low-quality evidence.

In patients with active PsA despite treatment with an IL-17i biologic, switching to a TNFi biologic is recommended over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic, adding MTX to the current IL-17i biologic, or switching to a different IL-17i biologic (Table 4 and Figure 6). Switching to an IL-12/23i biologic is recommended over adding MTX to the current IL-17i biologic or switching to a different IL-17i biologic. Treatment may be switched to an IL-12/23i biologic instead of a TNFi biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis or a contraindication to TNFi biologic treatment. Another IL-17i biologic may be used instead of switching to a TNFi or IL-12/23i biologic if the patient had a secondary efficacy failure with the current IL-17i biologic, severe psoriasis, or a contraindication to TNFi treatment. MTX may be added to the current IL-17i regimen instead of switching to a TNFi or IL-12/23i biologic in patients who have had a partial response to the current IL-17i biologic.

Active PsA despite treatment with an IL-12/23i biologic agent as monotherapy (Table 4 and Figure 6).

All recommendations for patients with active PsA despite IL-12/23i biologic treatment are conditional based on very-low-quality evidence.

In patients with active PsA despite treatment with an IL-12/23i biologic, switching to a TNFi biologic is recommended over adding MTX to the current regimen or switching to an IL-17i biologic (Table 4 and Figure 6). Switching to an IL-17i biologic is recommended over adding MTX to the current therapy. Treatment may be switched to an IL-17i biologic instead of a TNFi biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis or a contraindication to TNFi biologic treatment. MTX may be added to the current IL-12/23i biologic therapy instead of switching to a TNFi or an IL-17i biologic in patients with a partial response to the current therapy; MTX may also be added to the current IL-12/23i biologic therapy instead of switching to a TNFi biologic in the presence of contraindications to TNFi biologics.

Treat-to-target (Table 5).

Table 5.

Recommendations for treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis including treat-to-target, active axial disease, enthesitis, or active inflammatory bowel disease (PICOs 44–55; 58–62)*

| Level of evidence (evidence [refs.] reviewed)† | |

|---|---|

| In adult patients with active PsA, | |

| 1. Use a treat-to-target strategy over not following a treat-to-target strategy (PICO 44) | Low (113) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider not following a treat-to- target strategy in patients in whom higher frequency and/or severity of adverse events, higher cost of therapy, or higher patient burden of medications with tighter control are a concern. | |

| In patients with active PsA with psoriatic spondylitis/axial disease despite treatment with NSAIDs,‡ | |

| 2. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 46) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very- low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL- 17i biologic if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or if the patient has severe psoriasis.§ | |

| 3. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 45) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; switching to an IL-12 /23i biologic is not considered since recent trials in axial SpA were stopped. | |

| 4. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over switching to an IL-12/23i (PICO 47) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; switching to an IL-12 /23i biologic is not considered since recent trials in axial SpA were stopped. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA and predominant enthesitis who are both OSM- and biologic treatment–naive,¶ | |

| 5. Start oral NSAIDs over an OSM (specifically apremilast) (PICO 48) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider starting an OSM (specifically apremilast) if the patient has active joint disease and/or skin disease or contraindications to the use of NSAIDs, including cardiovascular disease, peptic ulcer disease, or renal disease or impairment. | |

| 6. Start a TNFi biologic over an OSM (specifically apremilast) (PICO 48A) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider starting an OSM (specifically apremilast) if the patient prefers an oral treatment as the first therapy or the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including recurrent infections, congestive heart failure, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 7. Start tofacitinib over an OSM (specifically apremilast) (PICO 55) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider starting an OSM (specifically apremilast) if the patient has recurrent infections. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA and predominant enthesitis despite treatment with OSM, | |

| 8. Switch to a TNFi biologic over an IL-17i biologic (PICO 53) | Low (72, 73, 76, 89, 90, 92) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL- 117i if the patient has severe psoriasis or contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 9. Switch to a TNFi biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 52) | Low (72, 73, 76, 98, 100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL- 12/23i if the patient has severe psoriasis or contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or if the patient prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 10. Switch to a TNFi biologic over switching to another OSM (PICO 49) | Low (72, 73, 76, 83–85) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switching to another OSM# if the patient prefers an oral medication over an injection, or if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| 11. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 54) | Low (89, 90, 92, 93, 98–100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL- 12/23i if the patient has concomitant IBD or if the patient prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 12. Switch to an IL-17i biologic over switching to another OSM (PICO 51) | Low (83–86, 89, 90, 92, 93) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switching to another OSM if the patient prefers an oral medication. | |

| 13. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over switching to another OSM (PICO 50) | Low (83–86, 98, 100) |

| Conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence; may consider switching to an- other OSM# if the patient prefers an oral medication over an injection, or if there are contraindications to an IL- 12/23i, such as severe recurrent infections. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA and concomitant active IBD who are both OSM- and biologic treatment–naive, | |

| 14. Start a monoclonal antibody TNFi biologic over an OSM (PICO 62) | Very low (114) |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider starting an OSM if the patient prefers an oral medication, or if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease. | |

| In adult patients with active PsA and concomitant active IBD despite treatment with an OSM, | |

| 15. Switch to a monoclonal antibody TNFi biologic over a TNFi biologic soluble receptor biologic (i.e., etanercept) (PICO 58) | Moderate (115–117) |

| Strong recommendation supported by moderate- quality evidence, showing TNFi monoclonal antibody biologics are effective in IBD but indirect evidence shows a TNFi biologic soluble receptor biologic is not effective for the treatment of IBD. | |

| 16. Switch to a TNFi monoclonal antibody biologic over an IL-17i biologic (PICO 59) | Moderate (50) |

| Strong recommendation supported by moderate- quality evidence showing monoclonal antibody TNFi biologics are effective for IBD while an IL- 17i biologic is not effective for IBD. | |

| 17. Switch to a TNFi biologic monoclonal antibody biologic over an IL-12/23i biologic (PICO 61) | Very low |

| Conditional recommendation based on very-low- quality evidence; may consider switching to an IL- 12/23i biologic if the patient has contraindications to TNFi biologics, including congestive heart failure, previous serious infections, recurrent infections, or demyelinating disease, or prefers less frequent drug administration. | |

| 18. Switch to an IL-12/23i biologic over switching to an IL-17i biologic (PICO 60) | Moderate (50) |

| Strong recommendation supported by moderate- quality evidence showing IL- 12/23i biologic is effective for IBD while an IL- 17i biologic is not effective for IBD. |

Active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as disease causing symptoms at an unacceptably bothersome level as reported by the patient, and judged by the examining clinician to be due to PsA based on ≥1 of the following: swollen joints, tender joints, dactylitis, enthesitis, axial disease, active skin and/or nail involvement, and extraarticular inflammatory manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

When there were no published studies, we relied on the clinical experience of the panelists, which was designated very-low-quality evidence.

Axial disease is generally treated according to the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for spondyloarthritis (SpA).

Because there are currently no widely agreed-upon definitions of disease severity, psoriasis severity should be established by the health care provider and patient on a case-by-case basis. In clinical trials, severe psoriasis has been defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (25) of ≥12 and a body surface area score of ≥10. In clinical practice, however, the PASI tool is not standardly utilized given its cumbersome nature. In 2007, the National Psoriasis Foundation published an expert consensus statement, which defined moderate-to-severe disease as a body surface area of ≥5% (68). In cases in which the involvement is in critical areas, such as the face, hands or feet, nails, intertriginous areas, scalp, or where the burden of the disease causes significant disability or impairment of physical or mental functioning, the disease can be severe despite the lower amount of surface area of skin involved. The need to factor in the unique circumstances of the individual patient is of critical importance, but this threshold provides some guidance in the care of patients.

Oral small molecules (OSMs) are defined as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine, leflunomide, cyclosporine, or apremilast and do not include tofacitinib, which was handled separately since its efficacy/safety profile is much different from that of other OSMs listed above. OSM- and biologic treatment–naive is defined as naive to treatment with OSMs, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi,), interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i), and IL-12/23i; patients may have received nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and/or other pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

It should be noted that for the enthesitis questions (PICO 49, 50, and 51), the existing evidence was mainly drawn from the apremilast studies, as no randomized controlled trial report described enthesitis outcomes for the other OSMs.

This recommendation for patients with active PsA is conditional based on low-quality evidence.

In patients with active PsA, using a treat-to-target strategy is recommended over not following a-treat-to-target strategy. One may consider not using a treat-to-target strategy in patients in whom there are concerns related to increased adverse events, costs of therapy, and patient burden of medications associated with tighter control.

Active PsA with psoriatic spondylitis/axial disease despite treatment with NSAIDs (Table 5).

All recommendations for patients with active PsA with psoriatic spondylitis/axial disease despite NSAID treatment are conditional based on very-low-quality evidence.

The ACR/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for patients with axial spondyloarthritis (35) should be followed for patients with axial PsA. OSMs are not effective for axial disease (35). In patients with active axial PsA despite NSAID treatment, a TNFi biologic is recommended over an IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic, and an IL-17i biologic is recommended over an IL-12/23i biologic. An IL-17i biologic may be used instead of a TNFi biologic if the patient has severe psoriasis or a contraindication to TNFi biologic treatment (Table 5). We recommend not using an IL-12/23i biologic since 3 randomized trials of an IL-12/23i biologic (ustekinumab) in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (a related condition) were stopped because the key primary and secondary end points were not achieved (36–38); the safety profile was reportedly consistent with that observed in past ustekinumab studies.

Active PsA with predominant enthesitis in treatment-naive patients and despite treatment with an OSM (Table 5).

All recommendations for patients with active PsA with predominant enthesitis are conditional based on low- to very-low-quality evidence. (This section names apremilast among all OSMs specifically for recommendations, since of the OSMs, only apremilast has shown efficacy for enthesitis.)

In treatment-naive PsA patients with predominant enthesitis, a TNFi biologic is recommended over an OSM as a first-line option. Apremilast may be used instead of a TNFi biologic if the patient prefers an oral therapy or has contraindications to TNFi. Oral NSAIDs are recommended over starting an OSM unless the patient has cardiovascular disease, peptic ulcer disease, renal disease (or impairment), or severe psoriasis or PsA, in which case apremilast may be given instead of NSAIDs. Tofacitinib is recommended over apremilast for treatment-naive patients with predominant enthesitis. Apremilast may be used instead of tofacitinib in patients with recurrent infections.

In patients with active PsA with predominant enthesitis despite treatment with an OSM (used for other manifestations of PsA), a TNFi biologic, an IL-17i biologic, or an IL-12/23i biologic is recommended over switching to another OSM. Apremilast may be used in patients who prefer oral therapy or who have recurrent infections or contraindications to TNFi biologics. A TNFi biologic is recommended over an IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic. An IL-17i or IL-12/23i biologic may be used instead of a TNFi biologic in patients with severe psoriasis or contraindications to TNFi. An IL-17i biologic is recommended over an IL-12/23i biologic. An IL-12/23i biologic may be used instead of a TNFi biologic in patients who prefer less frequent drug administration, and instead of an IL-17i biologic in patients with concomitant IBD or who prefer less frequent drug administration.

Active PsA with concomitant active IBD (Table 5).

All recommendations for patients with active PsA with concomitant active IBD are strong based on moderate-quality evidence, except for 2 conditional recommendations based on very-low-quality evidence.

Active PsA in OSM- and biologic treatment–naive patients with concomitant active IBD. In patients with active PsA with concomitant active IBD who have not received OSM or biologic treatment, a monoclonal antibody TNFi biologic (excludes etanercept, which is a fusion molecule/soluble receptor biologic) is recommended over an OSM (Table 5). An OSM may be used in patients without severe PsA who prefer oral therapy or have contraindications to TNFi biologics.