Abstract

Background

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) interventions can improve functional ability and reduce mortality in older adults, but the effectiveness of CGA intervention on the quality of life, caregiver burden, and length of hospital stay remains unclear. The study aimed to determine the effectiveness of CGA intervention on the quality of life, length of hospital stay, and caregiver burden in older adults by conducting meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods

A literature search in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library was conducted for papers published before February 29, 2020, based on inclusion criteria. Standardised mean difference (SMD) or mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated using the random-effects model. Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, and publication bias analyses were also conducted.

Results

A total of 28 RCTs were included. Overall, the intervention components common in different CGA intervention models were interdisciplinary assessments and team meetings. Meta-analyses showed that CGA interventions improved the quality of life of older people (SMD = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.03 to 0.21; P = 0.009) compared to usual care, and subgroup analyses showed that CGA interventions improved the quality of life only in participants’ age > 80 years and at follow-up ≤3 months. The change value of quality of life in the CGA intervention group was better than that in the usual care group on six dimensions of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36). Also, compared to usual care, the CGA intervention reduced the caregiver burden (SMD = − 0.56; 95% CI = − 0.97 to − 0.15, P = 0.007), but had no significant effect on the length of hospital stay.

Conclusions

CGA intervention was effective in improving the quality of life and reducing caregiver burden, but did not affect the length of hospital stay. It is recommended that future studies apply the SF-36 to evaluate the impact of CGA interventions on the quality of life and provide supportive strategies for caregivers as an essential part of the CGA intervention, to find additional benefits of CGA interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-021-02319-2.

Keywords: Comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention, Quality of life, Caregiver burden, Length of hospital stay, Meta-analysis

Background

People aged > 60 years will account for 22% of the world’s population by 2050 [1]. With worldwide population aging, increasing numbers of older adults are living with multiple chronic conditions and complex psychological and social problems [2]. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic intervention process centred on the older adults, through a comprehensive assessment of the physical, psychological, functional and socio-economic dimensions, to develop a comprehensive individual treatment plan for the betterment of the overall health of the older adults [3]. As a core technology in geriatrics, CGA has developed different intervention models applied in hospitals, outpatient clinics and in the community [4]. Numerous reviews have confirmed the benefits of CGA interventions for older adults compared to usual care: improved functional ability [4–6], reduced mortality [3, 4, 7], more probability to live at home after discharge [5, 8]. However, the effects of CGA interventions on the quality of life, caregiver burden and length of hospital stay are not yet clear [9, 10].

Quality of life is an important outcome measure in clinical research and its multidimensional connotations are aligned with the multidimensional intervention characteristics of CGA [11], enabling a comprehensive reflection of the effects of CGA interventions from the patient-reported perspective [12]. There were only 2 systematic reviews evaluating the impact of CGA interventions on the quality of life of older adults [13, 14]. One of the reviews only included 1 clinical trial and was not able to conduct meta-analysis, with the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36) as the evaluation instrument, and the results suggested that the CGA intervention group scored higher than the usual care group on physical component summary and mental component summary, which were statistically different but did not meet the criteria for clinical improvement [13]. Another review showed that neither of the two CGA intervention models (CGA unit and CGA-team) had an effect on the quality of life compared to usual care, and proposed that strength of the evidence for the finding was limited and that there was a need to further explore the impact of CGA interventions on quality of life [14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on “Integrated Caring for Older People” pointed out that caregiver burden should be a concern when caring for older people [15]. CGA interventions are primarily targeted at older people. There were only 2 systematic reviews that attempted to evaluate the impact of CGA interventions on the caregiver burden, but both did not report the results due to the lack of relevant studies [13, 14]. The length of hospital stay is an important economic outcome measure for evaluating CGA interventions. Some previous reviews only summarised the effects of CGA interventions on the length of hospital stay descriptively and did not conduct meta-analyses to clarify the specific effects [5, 6, 8, 16]. Other reviews conducted meta-analyses, but their results were controversial [17–20].

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses related to CGA evaluated the effectiveness of one or two CGA intervention models [5–8, 13, 14, 16–20], with only Stuck et al. [4] in 1993 providing a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of various CGA intervention models. Therefore, this study comprehensively collected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of various CGA intervention models and conducted meta-analyses to determine the effectiveness of CGA interventions on the quality of life, caregiver burden, and length of hospital stay for older adults.

Methods

This systematic review was reported according to the recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) main statement [21]. PRISMA checklist can be found in Additional file 1. It was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews database (PROSPERO: CRD42020178811).

Search strategy

The electronic databases of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library were systematically searched for studies published before February 29, 2020, with language restriction to English. The search strategy was developed initially in PubMed and then adapted for other databases. The search strategies of the three databases are available in Additional file 2. The reference lists of retrieved studies and previous relevant reviews were reviewed by manual searches to select any additional eligible studies.

Study selection and exclusion criteria

Two researchers (C.Z.Y. and D.Z.S.) independently screened all titles and abstracts from the search results. Full-text articles for all potentially eligible studies were independently reviewed by each researcher to determine final inclusion. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved through discussion, with the third researcher (C.C.X.) available to address any disagreements.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) participants: the age of adults meets the criteria for older people in the country where the study was being conducted. (2) intervention: various comprehensive geriatric assessment interventions were included. They are divided into inpatient CGA and outpatient CGA [4, 9]. The inpatient CGA includes two types of intervention models [4, 9]. The first is the CGA-team, which is delivered in the non-geriatric ward by a mobile multidisciplinary team as a consultation [4, 9]. The second is the CGA-unit. It is provided in geriatric-based wards or units by a multidisciplinary team that is the primary care provider for the older adults [4, 9]. The outpatient CGA includes three types of intervention models [4, 9]. The first is the outpatient assessment service (OAS) with CGA intervention provided in an outpatient setting [4, 9]. The second is the hospital home assessment service (HHAS) with in-home CGA intervention for patients recently discharged from the hospital [4, 9]. The third is home assessment service (HAS) with in-home CGA intervention for community-dwelling older people [4, 9]. (3) comparator: control group with usual care was included. (4) outcomes: studies that reported any of the following outcome measures were included: quality of life, caregiver burden and length of hospital stay. (5) study design: only RCTs were included. (6) publication type: only full original publications were considered. (7) language: only studies published in English were included.

Studies without the data of result were excluded. When there were duplicate reports in different studies, only the study providing the most detailed data were included in this systematic review. Stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trials were also excluded.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the included studies by two independent researchers (C.Z.Y. and D.Z.S.) respectively. The details of extracted data were shown in Table 1 and Additional file 3. Disagreements in data extraction between the two researchers were resolved through discussion to gain agreement, with the third researcher (C.C.X) available to address any disagreements.

Table 1.

Summary of outcomes of included studies

| Study | Outcomes | Evaluation instruments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life (measure time) |

Caregiver burden (measure time) |

Length of hospital stay (measure time) |

||

| Gayton 1987 [28] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Hogan 1987 [29] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Thomas 1993 [30] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Nikolaus 1999 (CGA) [31] |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 12 months) |

|||

| Nikolaus 1999 (CGA + home) [31] |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 12 months) |

|||

| Naglie 2002 [32] |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 6 months ǂ) |

|||

| Shyu 2005 [33] |

√ (1 month after discharge ǂ; 3 months after discharge ǂ) |

√ (Discharge) |

Quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire(SF-36) ǁ | |

| Vidan 2005 [34] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Kircher 2007 [35] |

√ (At follow up 3 months; at follow up 12 months) |

√ (At follow up 12 months) |

Quality of life: Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale(PGCMS) | |

| Pitkala 2008 [36] |

√ (Discharge) |

Quality of life: 15D questionnaire | ||

| Prestmo 2015 [37] |

√ (1 month after surgery; 4 month after surgery; 12 month after surgery) |

√ (Discharge) |

Quality of life:EQ-5D-3L | |

| Partridge 2017* [38] |

√ (Discharge ǂ) |

|||

| Applegate 1990* [39] |

√ (12 months after randomisation ǂ) |

|||

| Karppi 1995 [40] |

√ (At follow up 12 months; at follow up 24 months) |

|||

| Covinsky 1997 [41] |

√ (90 days after dischargeǂ) |

√ (Discharge) |

Caregiver burden: The Robinson Caregiver Strain Index ǁ | |

| Asplund 2000 [42] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Counsell 2000 [43] |

√ (Discharge) |

|||

| Cohen 2002(unit) [44] |

√ (Discharge; 12 months after randomisation) |

Quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire(SF-36) | ||

| Saltvedt 2004 [45] |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 6 months) |

|||

| Ekerstad 2016 [46] |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 3 months) |

√ (Discharge; at follow up 3 months) |

Quality of life: EuroQoL-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS); Health Utilities Index-3 ǁ | |

| Silverman 1995 [47] |

√ (12 months after randomisation) |

Caregiver burden: Family strain scale developed and validated by Morycz; a global burden questionnaire ǁ | ||

| Reuben 1999 [48] |

√ (At follow up 15 months) |

Quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire(SF-36) | ||

| Burns 2000 [49] |

√ (At follow up 12 months; at follow up 24 months) |

Quality of life: Rand general well-being (GWB) inventory; Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale ǁ; perceived global life satisfaction (GLS) ǁ | ||

| Weuve 2000 [50] |

√ (At follow up 12 months) |

Caregiver burden: previously developed inventory that consists of 22 equally weighted statements about perception of burden | ||

| Cohen 2002(outpatient) [44] |

√ (12 months after randomisation) |

Quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire(SF-36) | ||

| Ekdahl 2015 [51] |

√ (At follow up 12 months; at follow up 24 months) |

√ (At follow up 24 months) |

Quality of life: EQ-5D-3L | |

| Zintchouk 2018* [52] |

√ (At follow up 3 months ǂ) number of improvement |

√ (At follow up 3 months ǂ) |

Quality of life: Depression List (DL) ǁ | |

| Counsell 2007 [53] |

√ (At follow up 24 months) |

√ (At follow up 12 months ǂ; at follow up 24 months ǂ) |

Quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire(SF-36) | |

| Fairhall 2015 [54] |

√ (At follow up 3 months; at follow up 12 months) |

Quality of life: EQ-5D | ||

| Edmans 2013 [55] |

√ (At follow up 90 days) |

Quality of life: EQ-5D; ICEpop CA Pability measure for older people (ICECAP-O) ǁ | ||

CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment

* study not included in meta-analysis; ǂoutcome data at the endpoint not included in meta-analysis; ǁ outcome data measured by the evaluation instruments not included in meta-analysis

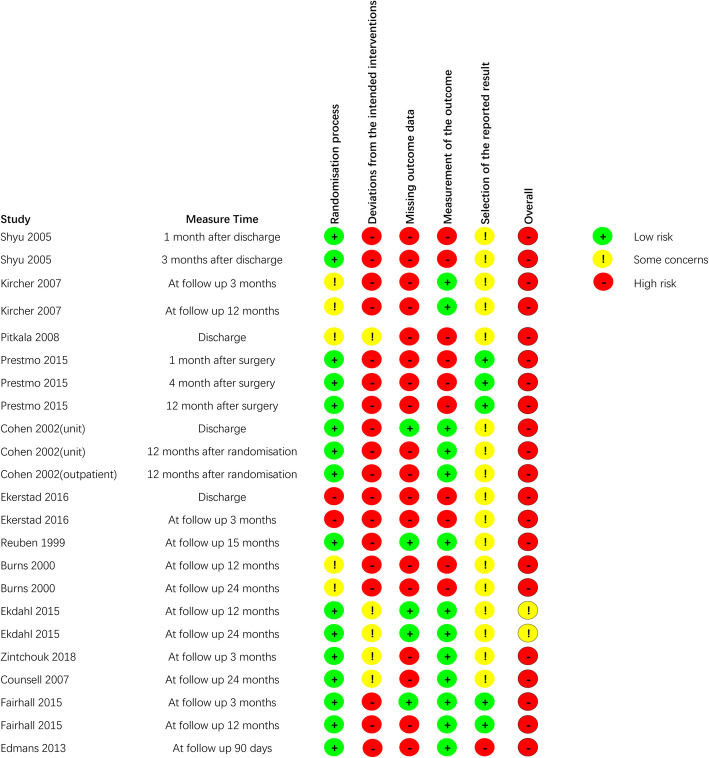

Assessment of risk of bias

Two researchers (C.Z.Y. and D.Z.S.) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB2) [22]. Risk of bias was evaluated in the five different domains: (1) randomisation process; (2) deviations from intended interventions; (3) missing outcome data; (4) measurement of the outcome; and (5) bias in selection of the reported result. Each domain was rated as having a low risk of bias, some concerns, or a high risk of bias. Because the risk of bias assessed is for a specific outcome or endpoint [22], we evaluated the risk of bias for each study separately for different evaluation indicators and for different outcome measure time. If any disagreements existed, the third researcher (J.Y.Y) was consulted to reach an agreement.

Data synthesis and analysis

Results were quantitatively synthetized by means of meta-analysis using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 software. For studies that reported only means, standard errors, t values or P values, we calculated standard deviations (SD) [23–26]. For studies that reported only range or 95% confidence intervals (CIs), we calculated means [23–26]. We also calculated means and SD of change values based on specific data at baseline and at endpoint [26]. Where possible and available, intent-to-treat data were preferred. For the continuous outcomes “quality of life” and “caregiver burden”, standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs were reported. The SMD is used as a summary statistic in meta-analysis when studies assess the same outcome but measure it in different ways [26]. For the continuous outcomes “length of hospital stay”, mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs were presented. A priori random-effects model was preferred based on the foreseeable complexity and multicomponent nature of CGA interventions. For each meta-analysis, statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and I2 statistic [26, 27]. If a P value < 0.1 or an I2 value > 50%, it represents a substantial or considerable heterogeneity [26]. If the pooled result included clinical heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was performed to search for the source of heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was performed based on intervention model, participants’ age, outcome measure time and evaluation instruments. Publication bias was explored by constructing the funnel plot and computing the Egger test using metafunnel and metabias commands in Stata software version 12.0 respectively. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis and sensitivity analyses based on risk of bias were performed to check the robustness of the results.

Results

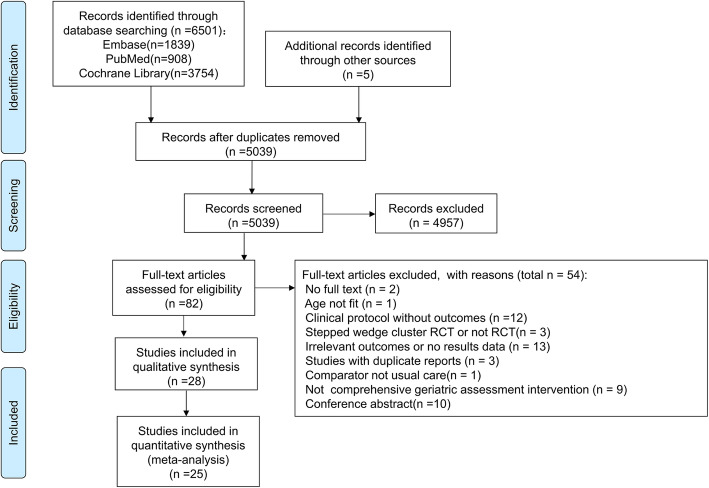

Selection of studies

Figure 1 showed the search and selection of studies based on the PRISMA flowcharts. The electronic search retrieved a total of 6501 relevant studies in the three databases, and 5 additional studies were identified by hand searching of these studies. Of these studies, 1467 studies were removed due to duplicates, and 4957 studies were excluded based on title and abstract content. The remaining 82 studies were retrieved for further full-text evaluations, 54 of which were excluded because they did not meet eligibility criteria. Finally, 28 randomised clinical trials were included in this review [28–55], and 25 randomised clinical trials were included in the meta-analysis [28–37, 40–51, 53–55].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Characteristics of included studies

We counted Cohen 2002 [44] as two studies (Cohen 2002(unit); Cohen 2002(outpatient)), as the researches used a 2 × 2 factorial design that compared care received in an inpatient geriatric evaluation and management unit versus usual care, followed by outpatient geriatric evaluation and management versus usual outpatient care. We also counted Nikolaus 1999 [31] as two studies (Nikolaus 1999(CGA); Nikolaus 1999(CGA + home)) owing to the different CGA interventions evaluated. Therefore, a total of 13,261 participants from 30 studies were included in this study. A summary of the 30 included studies is presented in Table 1 and Additional file 3. Studies were published between 1987 and 2018. The CGA intervention model included in the study consisted of CGA-team (n = 12) [28–38], CGA-unit (n = 8) [39–46], OAS (n = 7) [44, 47–52], HHAS (n = 2) [53, 54] and HAS (n = 1) [55]. The sample size of the studies varied from 98 to 1388 subjects. The mean age of participants ranged from 71.8 years to 85.7 years. The intervention components common in different CGA intervention models were interdisciplinary assessments (n = 30) [28–55] and team meetings (n = 15) [28–30, 32, 34, 35, 39, 42–45, 48, 51, 53, 54]. Fourteen studies used quality of life as an outcome measure [33, 35–37, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51–55], and 12 studies could be included in a meta-analysis [35–37, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 53–55]. The outcome measure time varied ranging from discharge to follow-up for 24 months. Three studies [41, 47, 50] used caregiver stress as an evaluation indicator and 2 studies [47, 50] could be included in a meta-analysis. The outcome measure time ranged from the 90 day after discharge to follow-up for 12 months. Twenty-one [28–35, 37–43, 45, 46, 51–53] studies used length of hospital stay as an evaluation indicator and 17 studies [28–31, 33–35, 37, 40–43, 45, 46, 51] could be included in a meta-analysis. The outcome measure time ranged from discharge to follow-up for 24 months.

Risk of bias

Assessments of the risk of bias are shown in Fig. 2, Additional file 4 and Additional file 5. There are five aspects that explain the sources of risk of bias. First, many studies with > 5% of data missing increased the risk of bias. Second, appropriate analyses (eg, intention-to-treat analysis) were not used to estimate the effect of assignment to intervention, which threatened the deviations from intended interventions. Third, no blinding of assessors and it was difficult or impossible to blind participants in CGA interventions, so the measurement of subjective outcomes was with increased risk of bias. Fourth, one study was rated as a high risk of randomisation process due to uncertainty of random assignment and impossibility of allocation sequence concealment. Lastly, one study was rated as a high risk of selection of the reported result due to inconsistency with the pre-registered protocol.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias of included studies about the outcome indicator quality of life

Results of meta-analysis

Meta-analysis results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of meta-analysis results

| Outcomes | Group basis | Subgroup name | Number of analyses (number of studies) |

Heterogeneity I2(%) | Effect SMD/MD[95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life level | overall | / | 15 (8) | 49 | 0.12 [0.03, 0.21] | 0.009 |

| Intervention model | CGA-team | 6 (3) | 44 | 0.05 [−0.08, 0.18] | 0.46 | |

| OAS | 4 (2) | 71 | 0.22 [−0.04, 0.48] | 0.09 | ||

| CGA-unit | 2 (1) | 56 | 0.23 [−0.01, 0.46] | 0.06 | ||

| HAS | 2 (1) | 21 | 0.17 [−0.04, 0.38] | 0.11 | ||

| HHAS | 1 (1) | / | 0.00 [−0.23, 0.23] | 1.00 | ||

| Mean age of participants | ≤ 80 years | 4 (2) | 77 | 0.20 [−0.15, 0.55] | 0.26 | |

| > 80 years | 11 (6) | 32 | 0.11 [0.02, 0.19] | 0.01 | ||

| Outcome measure time | ≤ 3 months | 7 (6) | 48 | 0.16 [0.03, 0.29] | 0.01 | |

| 3–12 months | 1 (1) | / | 0.02 [−0.19, 0.23] | 0.83 | ||

| ≥ 12 months | 7 (5) | 57 | 0.10 [−0.06, 0.25] | 0.21 | ||

| Evaluation instruments | EQ-5D | 8 (4) | 0 | 0.05 [−0.03, 0.13] | 0.24 | |

| 15D questionnaire | 1 (1) | / | 0.44 [0.14, 0.74] | 0.004 | ||

| PGCMS | 2 (1) | 0 | −0.06 [−0.26, 0.13] | 0.53 | ||

| EQ-VAS | 2 (1) | 56 | 0.23 [−0.01, 0.46] | 0.06 | ||

| GWB | 2 (1) | 0 | 0.53 [0.24, 0.81] | 0.0003 | ||

| Change of quality of life | overall | / | 5 (3) | 5 | 0.24 [0.10, 0.39] | 0.0008 |

| SF-36 Change values for physical functioning dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 0 | 0.11 [0.05, 0.16] | 0.0002 |

| SF-36 Change values for physical limitation dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 64 | 0.04 [−0.05, 0.14] | 0.39 |

| SF-36 Change values for general health dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 0 | 0.10 [0.05, 0.16] | 0.0003 |

| SF-36 Change values for body pain dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 56 | 0.09 [0.00, 0.18] | 0.04 |

| SF-36 Change values for mental health dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 22 | 0.13 [0.06, 0.19] | 0.0001 |

| SF-36 Change values for emotional limitation dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 0 | 0.04 [−0.02, 0.10] | 0.17 |

| SF-36 Change values for energy dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 65 | 0.15 [0.06, 0.25] | 0.002 |

| SF-36 Change values for social activity dimension | overall | / | 5 (4) | 37 | 0.10 [0.02, 0.17] | 0.01 |

| Caregiver burden | overall | / | 2 (2) | 35 | −0.56 [−0.97, −0.15] | 0.007 |

| Length of hospital stay | overall | / | 22 (17) | 100 | −1.04 [−3.57, 1.49] | 0.42 |

| Intervention model | CGA-unit | 9 (6) | 88 | 0.60 [−1.01, 2.22] | 0.46 | |

| CGA-team | 12 (10) | 100 | −1.59 [−5.23, 2.05] | 0.39 | ||

| OAS | 1 (1) | / | −4.10 [−8.73, 0.53] | 0.08 | ||

| Mean age of participants | ≤ 80 years | 8 (7) | 0 | −0.24 [−0.57, 0.09] | 0.16 | |

| > 80 years | 14 (10) | 100 | −0.85 [−4.17, 2.48] | 0.62 | ||

| Outcome measure time | ≤ 3 months | 15 (14) | 100 | 0.13 [−2.56, 2.82] | 0.93 | |

| 3–12 months | 1 (1) | / | 3.70 [−3.55, 10.95] | 0.32 | ||

| ≥ 12 months | 6 (5) | 100 | −5.17 [−12.35, 2.01] | 0.16 |

SMD, standardised mean difference; MD, mean difference; CI, confidence interval; CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; OAS, Outpatient Assessment Service; HHAS, Hospital Home Assessment Service; HAS, Home Assessment Service; PGCMS, Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale; EQ-VAS, EuroQoL-visual analog scale; GWB, Rand general well-being; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire

Quality of life

The evaluation instruments for the included studies are shown in Table 1.

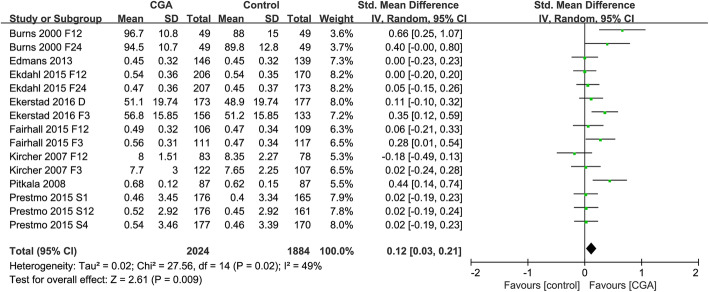

Quality of life level

Eight studies were included in the meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of CGA interventions on the quality of life levels of older people [35–37, 46, 49, 51, 54, 55]. Meta-analysis results showed that CGA interventions improved the quality of life of older people (SMD = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.03 to 0.21; P = 0.009). (Fig. 3) There was moderate heterogeneity (P = 0.02, I2 = 49%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the effect of CGA intervention on quality of life level

Based on the funnel plot asymmetry, evidence of publication bias was found (Additional file 6). Based on Egger’s test (P = 0.029), evidence of small-study effect was found (Additional file 6). Since there was evidence of small-study effect, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding data from Burns 2000 and Piktala 2008. The results unveiled a trend of significant effect in quality of life (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI = − 0.00 to 0.13; P = 0.05), and decreased between-study heterogeneity from 49 to 10%. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis revealed that the direction of the main result were largely unchanged by excluding studies by turns (Additional file 7). However, sensitivity analysis only including studies with low risk of measurement of the outcome changes the direction of the main result (Additional file 8).

Table 2 summarizes the results of subgroup analyses. The overall effect on each of the subgroups (CGA-team [35–37], CGA-unit [46], OAS [49, 51], HHAS [55], HAS [54]) did not exert a significant effect on the quality of life, but reflected a trend in favour of CGA interventions, with SMD > 0. (Additional file 9). The subgroup analysis did not substantially explain or reduce the heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis was also performed according to the participants’ age (≤ 80 years and > 80 years). We found that CGA intervention was superior to usual care for the quality of life only in subgroup of participants age > 80 years [36, 37, 46, 51, 54, 55] (Additional file 10).

When we grouped the studies according to the outcome measure time (at follow-up / after surgery ≤ 3 months, 3–12 months, ≥ 12 months), we found that CGA intervention was superior to usual care for the quality of life only at follow-up ≤ 3 months (Additional file 11).

When the studies were grouped according to evaluation instruments (EQ-5D、EQ-VAS、15 D questionnaire、PGCMS, GWB), we found that there was a significant difference between the subgroups(P = 0.0008, I2 = 78.8%). No differences in the scores of quality of life measured by EQ-5D [37, 51, 54, 55], PGCMS [35] and EQ-VAS [46] were found between CGA intervention and usual care. CGA intervention demonstrated benefit for the quality of life when measured by 15D questionnaire [36] and the Rand general well-being (GWB) inventory [49] (Additional file 12).

Change of quality of life

The meta-analysis of the change of quality of life included three studies [36, 49, 54]. The results of the meta-analysis showed a positive effect of the CGA intervention on quality of life (SMD = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.10 to 0.39; P = 0.0008), with negligible heterogeneity (P = 0.38, I2 = 5%).

SF-36 change values for each dimension

The SF-36 does not evaluate the general quality of life. Thus, the eight SF-36 domains (physical functioning, physical limitation, general health, body pain, mental health, emotional limitation, energy and social activity) were analysed separately [56]. A total of 4 studies were included and meta-analyses were conducted on the change values of each dimension of the SF-36 [44, 48, 53]. With the exception of the physical limitations and emotional limitations dimensions, the change values for other six dimensions were significantly better in the CGA intervention group than in the usual care group, and the specific change values are shown in the Table 2.

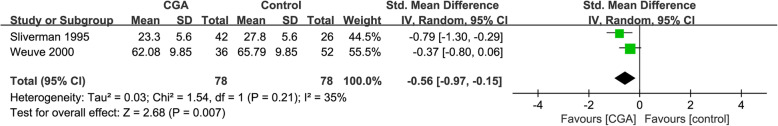

Caregiver burden

Meta-analysis results indicated that the CGA intervention reduced caregiver burden (SMD = − 0.56; 95% CI = − 0.97 to − 0.15; P = 0.007), with low heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.21, I2 = 35%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the effect of CGA intervention on caregiver burden

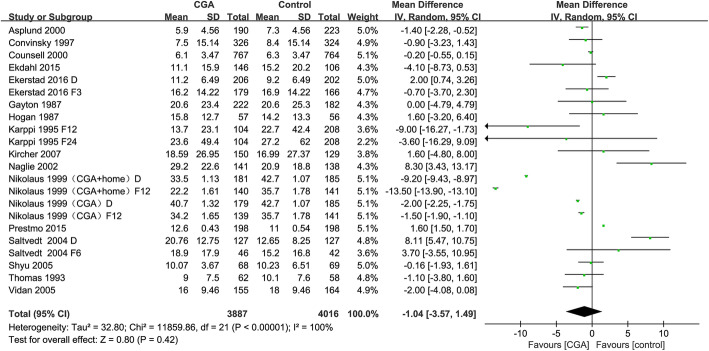

Length of hospital stay

Result of meta-analysis indicated that there was no benefit from the CGA intervention on length of hospital stay (MD = − 1.04; 95% CI = − 3.57 to 1.49; P = 0.42), with high heterogeneity between studies (P < 0.00001, I2 = 100%) (Fig. 5). The heterogeneity was so remarkable (P < 0.00001, I2 = 100%) that it could not be altered by omitting any single study from the sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the direction of the main association were largely unchanged neither by only including studies with some concerns in risk of bias nor by excluding studies by turns (Additional files 8 and 13). Based on the funnel plot asymmetry, no evidence of publication bias was found (Additional file 14). Based on Egger’s test (P = 0.388), no evidence of small-study effect was found (Additional file 14).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the effect of CGA intervention on length of hospital stay

The overall effect on each of the subgroups based on intervention model, participants' age or outcome measure time did not reveal a significant difference between the CGA intervention and usual care (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that extensively included randomised controlled trials of different CGA intervention models to explore the effectiveness of CGA interventions on the quality of life and caregiver burden. In addition, this study also explored the effect of the CGA intervention on the length of hospital stay. The meta-analyses of the included studies showed that CGA interventions improved the quality of life and reduced the caregiver burden compared to usual care, but had a similar impact on the length of hospital stay as usual care.

Only Ekdahl et al. has conducted a meta-analysis of the impact of CGA interventions on quality of life, and its results are consistent and inconsistent with the results of this study [14]. It included five related RCTs published before 2007, and the results of the subgroup analysis (CGA-team and CGA-unit subgroup) as well as the overall combined effect showed no effect of the CGA intervention on quality of life in hospitalised frail older people. This is consistent with our results of subgroup analysis based on the CGA intervention model, but inconsistent with the overall combined effect. There are two main reasons for the inconsistency in the overall combined effect: firstly, the number of studies included in our meta-analysis was 8 (with 15 analyses), and the included studies contained studies published after 2007. The feasibility and acceptability of recent CGA intervention studies was better as the CGA intervention protocol was refined; when excluding related RCTs published before 2007, positive results in terms of improved quality of life were still found (SMD = 0.09; 95% CI = 0.01to 0.17; P = 0.03), while heterogeneity was reduced (I2 = 33%). Second, our subgroup analysis showed that there was no statistical difference in the effect of the 5 CGA intervention models versus usual care on quality of life, but the SMD was greater than 0 for all 4 subgroups except for the HHAS subgroup (SMD = 0), suggesting a trend towards improved quality of life in all 4 subgroups [57]. However, the SMD for 2 subgroups of Ekdahl et al. was less than 0. Therefore, the trend towards positive outcomes for the 4 subgroups in our study contributed to the overall positive results. As health professionals, we are concerned about the effects of CGA interventions and also the circumstances in which positive CGA intervention effects are more likely to be achieved. This study found that positive effects of CGA interventions (quality of life improvements) were more likely to occur in the following situations: firstly, only when participants were older than 80 years, CGA interventions improved their quality of life. However, as there were only 2 studies in the subgroup of participants aged ≤80 years, there may have been insufficient data for chance results. Previous systematic review suggested that the effect of age differences on the effectiveness of CGA interventions is uncertain and needs to be further explored in future studies [8]. Second, CGA interventions improved the quality of life of older people only at follow up ≤3 months. Functional status is the most significant predictor of quality of life [58, 59], and the focus of comprehensive geriatric assessment, and different CGA intervention models include appropriate rehabilitation interventions and multidisciplinary interventions to maintain the patient’s function [9]. A meta-analysis showed that the effect of multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation interventions to improve function in older people only occurred in the short term and the effect disappeared at 3–12 months follow-up [16], suggesting that the positive results of multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation interventions on quality of life may only occur in the short term, which supports the findings of this study to some extent. Third, the selection of instruments with high sensitivity to changes in quality of life in older people contributed to the positive results observed. The most used scale in the studies included in this review was the EQ-5D, followed by the SF-36. No differences in the scores of quality of life measured by EQ-5D were found between CGA intervention and usual care, which were inconsistent with the results of the meta-analysis of overall quality of life levels as well as change of quality of life. This may be possibly related to the limited reflection [60], poor responsiveness and sensitivity of EQ-5D to quality of life of older adults, which was found in previous studies [54, 61]. Previous studies found some evidence that SF-36 was sensitive to changes in the quality of life of older people [59, 62]. Our meta-analysis of SF-36 change values for each dimension found that the CGA intervention was able to improve quality of life in older adults across six dimensions. To facilitate future meta-analyses to further clarify the impact of CGA interventions on quality of life, it is recommended that the SF-36 be used consistently when evaluating the effects of CGA interventions. Previous evidence suggested that caregiver burden can lead to reduced quality of life for caregiver, increased risk of caregiver death and increased risk of institutionalisation of older people [63, 64]. There has been concern about how caregiver burden changes after CGA interventions [65]. Our result of meta-analysis showed that CGA interventions reduced caregiver burden compared to usual care. This may be related to the fact that the CGA intervention in the 2 RCTs included in the meta-analysis contained supportive strategies for caregivers (providing recommendations and consultation regarding caregiving) [47, 50]. Silliman et al. [66] found that providing recommendations and family education for caregivers of older people was beneficial to their general health. Previous research suggested that providing supportive caregiver education can improve not only the quality of life of the caregiver, but also potentially the quality of life of the patient [67]. Therefore, providing supportive strategies for caregivers should be an essential part of CGA interventions in order to discover the greater benefits of CGA interventions. The results of this review showed that the CGA intervention had no significant effect on the length of hospital stay. The results of previous reviews are controversial, with some studies having similar results to ours [19, 20] and others inconsistent [17, 18]. The results of the sensitivity analysis suggested that our results are robust and stable, but due to the presence of high heterogeneity (heterogeneity was not reduced by subgroup analysis) and the controversial results of previous reviews, the strength of evidence for the results was limited. Therefore, future studies should further clarify the effect of CGA interventions on the length of hospital stay.

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. Firstly, the overall risk of bias among the included studies is generally “high” or “some concerns”, and caution is needed in the interpretation of the results. Second, there was moderate or even high heterogeneity between included studies, which persisted despite subgroup analyses; studies included in the overall quality of life level meta-analysis had publication bias, and its sensitive analyses that included only studies with low risk of measurement of outcome were inconsistent with the overall combined results, so its meta-analysis results may not be robust. Third, there were fewer included studies for the caregiver burden meta-analysis, so the strength of evidence for the results was limited. Fourth, the applicability of the results of this review is limited by the fact that the studies included in this review were mainly located in in European and American countries, with few studies from other regions. Fifth, as the included studies were limited to English-language published RCTs and did not include unpublished studies, there is a risk of increased publication bias.

Conclusions

Compared to usual care, CGA intervention was effective in improving quality of life and reducing caregiver burden in older adults, but had no effect on the length of hospital stay. It is recommended that future studies apply the SF-36 to evaluate the impact of CGA interventions on quality of life and provide supportive strategies for caregivers as an essential part of the CGA intervention, with a view to finding additional benefits of CGA interventions.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2. Search strategies of the three databases.

Additional file 3. Characteristics and summary findings of included studies.

Additional file 4. Risk of bias of included studies about the outcome indicator caregiver burden.

Additional file 5. Risk of bias of included studies about the outcome indicator length of hospital stay.

Additional file 6. Publication bias test results of the quality of life.

Additional file 7. Sensitivity analysis for the quality of life by excluding studies by turns.

Additional file 8. Sensitivity analyses for primary outcome.

Additional file 9. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on different intervention models.

Additional file 10. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on participants' age.

Additional file 11. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on outcome measure time.

Additional file 12. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on evaluation instrument.

Additional file 13. Sensitivity analysis for length of hospital stay by excluding studies by turns.

Additional file 14. Publication bias test results of the length of hospital stay.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the authors of the included studies.

Abbreviations

- CGA

comprehensive geriatric assessment

- RCTs

randomised controlled trials

- SMD

standardised mean difference

- MD

mean difference

- CIs

confidence intervals

- CI

confidence interval

- SF-36

36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire

- WHO

World Health Organization

- RevMan

Review Manager

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- OAS

outpatient assessment service

- HHAS

hospital home assessment service

- HAS

home assessment service

- SD

standard deviations

- IG

intervention group (comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention group)

- CG

control group (usual care group)

- EQ-VAS

EuroQoL-visual analog scale

- PGCMS

Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale

- GWB

Rand general well-being inventory

- GLS

perceived global life satisfaction

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale

- ICECAP-O

ICEpop CA Pability measure for older people

- DL

Depression List

- D

discharge

- F3

at follow up 3 months

- F6

at follow up 6 months

- F12

at follow up 12 months

- F24

at follow up 24 months

- S1

1 month after surgery

- S4

4 month after surgery

- S12

12 month after surgery

- R12

12 months after randomisation

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: C.Z.Y, D.Z.S, C.C.X, J.Y.Y. and S.Y.F. Data acquisition, screening, and coding: C.Z.Y, D.Z.S, J.Y.Y. and L.F.L. Risk of bias assessment and meta-analysis: C.Z.Y, C.C.X, S.Y.F. and W.S.S. Study supervision: D.Z.S, C.C.X and J.Y.Y. Initial writing and drafting of the manuscript: C.Z.Y. All authors interpreted the data and revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be submitted.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wuxi Science and Technology Development Fund (Grant WX0302B010507180074PB), and the Launching Fund of Research Office of Chronic Disease Management and Rehabilitation, Wuxi School of Medicine, Jiangnan University.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dann T. Global elderly care in crisis. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):927. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S, Barakovic Husic J, Tomsone S, Krejcar O, et al. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age - a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1431. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7762-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenstein LZ, Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland D. Impacts of geriatric evaluation and management programs on defined outcomes: overview of the evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(9 Pt 2):8S–16S. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb05927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O'Neill D, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d6553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baztán JJ, Suárez-García FM, López-Arrieta J, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eamer G, Saravana-Bawan B, van der Westhuizen B, Chambers T, Ohinmaa A, Khadaroo RG. Economic evaluations of comprehensive geriatric assessment in surgical patients: a systematic review. J Surg Res. 2017;218:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD006211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilotto A, Cella A, Pilotto A, Daragjati J, Veronese N, Musacchio C, et al. Three Decades of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Evidence Coming From Different Healthcare Settings and Specific Clinical Conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(2):192.e1–192.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, McCleod A, Arora S, Nockels K, Kennedy S, Roberts H, Conroy S. What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing. 2018;47(1):149–155. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panzini RG, Mosqueiro BP, Zimpel RR, Bandeira DR, Rocha NS, Fleck MP. Quality-of-life and spirituality. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(3):263–282. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2017.1285553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Church J. Quality of life and patient-reported outcomes. Br J Surg. 2018;105(3):157–158. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conroy SP, Stevens T, Parker SG, Gladman JR. A systematic review of comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve outcomes for frail older people being rapidly discharged from acute hospital: 'interface geriatrics'. Age Ageing. 2011;40(4):436–443. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekdahl AW, Sjöstrand F, Ehrenberg A, Oredsson S, Stavenow L, Wisten A, et al. Frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment organized as CGA-ward or CGA-consult for older adult patients in the acute care setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6(6):523–40. 10.1016/j.eurger.2015.10.007.

- 15.World Health Organization. Evidence profile: caregiver support. In: Integrated care for older people (ICOPE) -Guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-ALC-ICOPE_brochure.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 16 June 2021. [PubMed]

- 16.Bachmann S, Finger C, Huss A, Egger M, Stuck AE, Clough-Gorr KM. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c1718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eamer G, Taheri A, Chen SS, Daviduck Q, Chambers T, Shi X, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):CD012485. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012485.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, O'Brien K, Brooks D, Tregunno D, Schraa E. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2237–2245. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Craen K, Braes T, Wellens N, Denhaerynck K, Flamaing J, Moons P, et al. The effectiveness of inpatient geriatric evaluation and management units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(1):83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deschodt M, Flamaing J, Haentjens P, Boonen S, Milisen K. Impact of geriatric consultation teams on clinical outcome in acute hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.JAC S, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(6):1785–1805. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knopp-Sihota JA, Patel P, Estabrooks CA. Interventions for the Treatment of Pain in Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(12):1163.e19–1163.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JPT, Li T, Deeks JJ. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. Version 6.2, 2021. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06. Accessed 16 June 2021.

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gayton D, Wood-Dauphinee S, de Lorimer M, Tousignant P, Hanley J. Trial of a geriatric consultation team in an acute care hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35(8):726–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb06350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogan DB, Fox RA, Badley BW, Mann OE. Effect of a geriatric consultation service on management of patients in an acute care hospital. CMAJ. 1987;136(7):713–717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas DR, Brahan R, Haywood BP. Inpatient community-based geriatric assessment reduces subsequent mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(2):101–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolaus T, Specht-Leible N, Bach M, Oster P, Schlierf G. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and home intervention in the care of hospitalized patients. Age Ageing. 1999;28(6):543–550. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naglie G, Tansey C, Kirkland JL, Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Detsky AS, Etchells E, Tomlinson G, O'Rourke K, Goldlist B. Interdisciplinary inpatient care for elderly people with hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2002;167(1):25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shyu YI, Liang J, Wu CC, Su JY, Cheng HS, Chou SW, et al. A pilot investigation of the short-term effects of an interdisciplinary intervention program on elderly patients with hip fracture in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):811–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vidán M, Serra JA, Moreno C, Riquelme G, Ortiz J. Efficacy of a comprehensive geriatric intervention in older patients hospitalized for hip fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1476–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kircher TT, Wormstall H, Müller PH, Schwärzler F, Buchkremer G, Wild K, Hahn JM, Meisner C. A randomised trial of a geriatric evaluation and management consultation services in frail hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(1):36–42. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H, Sintonen H, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: effects on costs and health-related quality of life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(1):56–61. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prestmo A, Hagen G, Sletvold O, Helbostad JL, Thingstad P, Taraldsen K, Lydersen S, Halsteinli V, Saltnes T, Lamb SE, Johnsen LG, Saltvedt I. Comprehensive geriatric care for patients with hip fractures: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1623–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Partridge JS, Harari D, Martin FC, Peacock JL, Bell R, Mohammed A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and optimization in vascular surgery. Br J Surg. 2017;104(6):679–687. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Applegate WB, Miller ST, Graney MJ, Elam JT, Burns R, Akins DE. A randomized, controlled trial of a geriatric assessment unit in a community rehabilitation hospital. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(22):1572–1578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karppi P, Tilvis R. Effectiveness of a Finnish geriatric inpatient assessment. Two-year follow up of a randomized clinical trial on community-dwelling patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1995;13(2):93–98. doi: 10.3109/02813439508996743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covinsky KE, King JT, Jr, Quinn LM, Siddique R, Palmer R, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J, Landefeld CS. Do acute care for elders units increase hospital costs? A cost analysis using the hospital perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(6):729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asplund K, Gustafson Y, Jacobsson C, Bucht G, Wahlin A, Peterson J, Blom JO, Ängquist KA. Geriatric-based versus general wards for older acute medical patients: a randomized comparison of outcomes and use of resources. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(11):1381–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic DM, Quinn LM, Allen KR, Covinsky KE, Landefeld CS. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C, Pennypacker L, Smith DM, Ainslie N, Hornick T, Brodkin K, Lavori P. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saltvedt I, Saltnes T, Mo ES, Fayers P, Kaasa S, Sletvold O. Acute geriatric intervention increases the number of patients able to live at home. A prospective randomized study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(4):300–306. doi: 10.1007/BF03324555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekerstad N, Karlson BW, Dahlin Ivanoff S, Landahl S, Andersson D, Heintz E, et al. Is the acute care of frail elderly patients in a comprehensive geriatric assessment unit superior to conventional acute medical care? Clin Interv Aging. 2016;12:1–9. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S124003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silverman M, Musa D, Martin DC, Lave JR, Adams J, Ricci EM. Evaluation of outpatient geriatric assessment: a randomized multi-site trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(7):733–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuben DB, Frank JC, Hirsch SH, McGuigan KA, Maly RC. A randomized clinical trial of outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment coupled with an intervention to increase adherence to recommendations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(3):269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(1):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weuve JL, Boult C, Morishita L. The effects of outpatient geriatric evaluation and management on caregiver burden. Gerontologist. 2000;40(4):429–436. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ekdahl AW, Wirehn AB, Alwin J, Jaarsma T, Unosson M, Husberg M, Eckerblad J, Milberg A, Krevers B, Carlsson P. Costs and effects of an ambulatory geriatric unit (the AGe-FIT study): a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zintchouk D, Gregersen M, Lauritzen T, Damsgaard EM. Geriatrician-performed comprehensive geriatric care in older adults referred to an outpatient community rehabilitation unit: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;51:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, Ricketts GD. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623–2633. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Kurrle SE, Lord SR, Lockwood K, Howard K, Hayes A, Monaghan N, Langron C, Aggar C, Cameron ID. Economic evaluation of a multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention versus usual care to reduce frailty in frail older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edmans J, Bradshaw L, Franklin M, Gladman J, Conroy S. Specialist geriatric medical assessment for patients discharged from hospital acute assessment units: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f5874. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Cai J, An L, Hui F, Ren T, Ma H, Zhao Q. Does music therapy enhance behavioral and cognitive function in elderly dementia patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tyack Z, Frakes KA, Barnett A, Cornwell P, Kuys S, McPhail S. Predictors of health-related quality of life in people with a complex chronic disease including multimorbidity: a longitudinal cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(10):2579–2592. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klompstra L, Ekdahl AW, Krevers B, Milberg A, Eckerblad J. Factors related to health-related quality of life in older people with multimorbidity and high health care consumption over a two-year period. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1194-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Schmidt LJ, Mackintosh AE, Fitzpatrick R. Health Status and Quality of Life in Older People: a Structured Review of Patient-reported Health Instruments Report from the Patient- reported Health Instruments Group (formerly the Patient-assessed Health Outcomes Programme) to the Department of Health, April 2004. https://s10.aconvert.com/convert/p3r68-cdx67/aefjd-ugmkp.html. Accessed 17 June 2021.

- 61.Hage C, Mattsson E, Ståhle A. Long-term effects of exercise training on physical activity level and quality of life in elderly coronary patients--a three- to six-year follow-up. Physiother Res Int. 2003;8(1):13–22. doi: 10.1002/pri.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brazier JE, Walters SJ, Nicholl JP, Kohler B. Using the SF-36 and Euroqol on an elderly population. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(2):195–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00434741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alltag S, Conrad I, Riedel-Heller SG. Pflegebelastungen bei älteren Angehörigen von Demenzerkrankten und deren Einfluss auf die Lebensqualität : Eine systematische Literaturübersicht [caregiver burden among older informal caregivers of patients with dementia and its influence on quality of life : a systematic literature review] Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;52(5):477–486. doi: 10.1007/s00391-018-1424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hedrick SC, Barrand N, Deyo R, Haber P, James K, Metter J, et al. Working group recommendations: measuring outcomes of care in geriatric evaluation and management units. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(9 Pt 2):48S–52S. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb05935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silliman RA, McGarvey ST, Raymond PM, Fretwell MD. The senior care study. Does inpatient interdisciplinary geriatric assessment help the family caregivers of acutely ill older patients? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(4):461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig C, Brewer BW, Sannes TS, Kilbourn K, Gutman J, McSweeney P. A randomized control trial of stress management for caregivers of stem cell transplant patients: effect on patient quality of life and caregiver distress. Psychooncology. 2019;28(8):1614–1623. doi: 10.1002/pon.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Additional file 2. Search strategies of the three databases.

Additional file 3. Characteristics and summary findings of included studies.

Additional file 4. Risk of bias of included studies about the outcome indicator caregiver burden.

Additional file 5. Risk of bias of included studies about the outcome indicator length of hospital stay.

Additional file 6. Publication bias test results of the quality of life.

Additional file 7. Sensitivity analysis for the quality of life by excluding studies by turns.

Additional file 8. Sensitivity analyses for primary outcome.

Additional file 9. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on different intervention models.

Additional file 10. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on participants' age.

Additional file 11. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on outcome measure time.

Additional file 12. Quality of life-subgroup analysis based on evaluation instrument.

Additional file 13. Sensitivity analysis for length of hospital stay by excluding studies by turns.

Additional file 14. Publication bias test results of the length of hospital stay.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.