Key Points

Question

Does the use of family vouchers for future kidney transplant help to expand the living donor pool, and are voucher redemptions capable of facilitating timely kidney allografts?

Findings

In this cohort study of 250 family voucher–based kidney donations across 79 transplant centers in the US, the use of vouchers precipitated 573 downstream kidney transplants. Although the reasons were multifactorial, the waiting time until transplant among candidate recipients in this kidney exchange registry decreased by 3 months since the inception of family voucher–based donation.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the family voucher program facilitated living kidney donations that may not otherwise have occurred by overcoming chronological incompatibility between donor-recipient pairs.

Abstract

Importance

Policy makers, transplant professionals, and patient organizations agree that there is a need to increase the number of kidney transplants by facilitating living donation. Vouchers for future transplant provide a means of overcoming the chronological incompatibility that occurs when the ideal time for living donation differs from the time at which the intended recipient actually needs a transplant. However, uncertainty remains regarding the actual change in the number of living kidney donors associated with voucher programs and the capability of voucher redemptions to produce timely transplants.

Objective

To examine the consequences of voucher-based kidney donation and the capability of voucher redemptions to provide timely kidney allografts.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter cohort study of 79 transplant centers across the US used data from the National Kidney Registry from January 1, 2014, to January 31, 2021, to identify all family vouchers and patterns in downstream kidney-paired donations. The analysis included living kidney donors and recipients participating in the National Kidney Registry family voucher program.

Exposures

A voucher was provided to the intended recipient at the time of donation. Vouchers had no cash value and could not be sold, bartered, or transferred to another person. When a voucher was redeemed, a living donation chain was used to return a kidney to the voucher holder.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Deidentified demographic and clinical data from each kidney donation were evaluated, including the downstream patterns in kidney-paired donation. Voucher redemptions were separately evaluated and analyzed.

Results

Between 2014 and 2021, 250 family voucher–based donations were facilitated. Each donation precipitated a transplant chain with a mean (SD) length of 2.3 (1.6) downstream kidney transplants, facilitating 573 total transplants. Of those, 111 transplants (19.4%) were performed in highly sensitized recipients. Among 250 voucher donors, the median age was 46 years (range, 19-78 years), and 157 donors (62.8%) were female, 241 (96.4%) were White, and 104 (41.6%) had blood type O. Over a 7-year period, the waiting time for those in the National Kidney Registry exchange pool decreased by more than 3 months. Six vouchers were redeemed, and 3 of those redemptions were among individuals with blood type O. The time from voucher redemption to kidney transplant ranged from 36 to 155 days.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, the family voucher program appeared to mitigate a major disincentive to living kidney donation, namely the reluctance to donate a kidney in the present that could be redeemed in the future if needed. The program facilitated kidney donations that may not otherwise have occurred. All 6 of the redeemed vouchers produced timely kidney transplants, indicating the capability of the voucher program.

This cohort study uses data from the National Kidney Registry between 2014 and 2021 to examine the family voucher–based kidney donation and the capability of voucher redemption to provide timely kidney allografts.

Introduction

Vouchers for future kidney transplant provide a means of overcoming the chronological incompatibility that occurs when the ideal time for the donor to give a kidney differs from the time at which the intended recipient actually needs a kidney transplant.1 Potential donors are able to donate a kidney and secure a voucher for their intended recipient, which can be redeemed, with the kidney of a different donor, if needed in the future. Policy makers, transplant professionals, and patient organizations agree that there is a need to increase the number of kidney transplants by facilitating living donation.2,3 In July 2019, the White House announced that it would be adopting measures to expand kidney transplants, which would include increasing public education, decreasing the organ discard rate, and removing barriers to donation.4

The removal of disincentives for living kidney donation has received increasing attention from health care professionals and policy.2,3,4,5,6,7 The US government, including the Department of Health and Human Services, has responded to this consensus with actions aimed at assisting with accrued costs to make living donation a financially neutral process.7,8,9,10 The use of vouchers in living donation offers a means of increasing donations that does not require regulatory change or additional government spending.5 Moreover, the benefits of using vouchers to expand living donation are not speculative and have been reported over the past 6 years.3 However, uncertainty remains regarding the actual increase in the number of living kidney donors associated with these measures. This cohort study aimed to examine the consequences of family voucher–based kidney donation and the capability of voucher redemptions to provide timely kidney allografts.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. A waiver of informed consent was granted for research performed through the National Kidney Registry (NKR) because the information is recorded in a manner in which participants cannot be identified. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Operation of the Family Voucher Program

The process of voucher-based donation and redemption has been described previously.1 In brief, the nondirected (ie, altruistic) kidney donor is able to identify a recipient, who then obtains a voucher that may be redeemed at a later date if a kidney is needed. When a voucher is redeemed, a living donation chain is used to return a kidney to the voucher holder. Vouchers have no cash value and cannot be sold, bartered, or transferred to another person. The NKR is a nonprofit organization, and patients are not required to pay for participation in the voucher program. Voucher redemption is currently the third of 6 categories in the NKR priority schema. Although vouchers provide priority status for a living donor transplant if a kidney is needed, they do not guarantee that a kidney will be available. At present, vouchers neither help nor harm a person’s status on the deceased donation waiting list.

Voucher holders were identified at the time of kidney donation. Government-issued identification, ABO blood type, and human leukocyte antigen typing via cheek swabs were recorded and used to confirm identity at the time of voucher redemption. Only 1 voucher could be redeemed per donation. After voucher redemption, all other vouchers associated with the donation were nullified. If the person (or persons) to whom a voucher was issued died or was deemed permanently ineligible for kidney transplant, the unredeemed voucher became void. Consent forms for both donors and voucher recipients are shown in eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

The NKR family voucher program is an advancement in kidney-paired donation that operates within the framework of a network of transplant centers. Several centers participate (ie, offer voucher-based donation); however, not all centers have actually performed a voucher-based donation. In 2019, the NKR Medical Board approved 2 major amendments to voucher donation.11 First, vouchers may be issued to healthy individuals (ie, those without kidney disease). Second, a single donor is permitted to designate up to 5 intended recipients. The new family voucher model is expected to increase nondirected (altruistic) living donation by providing additional security to donors should a healthy family member require a kidney in the future.

Data Extraction

The NKR database was queried from January 1, 2014, to January 31, 2021, for all voucher-based donations. Deidentified demographic and clinical data from each donation were evaluated, including the downstream patterns in kidney-paired donation. Family voucher redemptions were separately evaluated and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corp).

Results

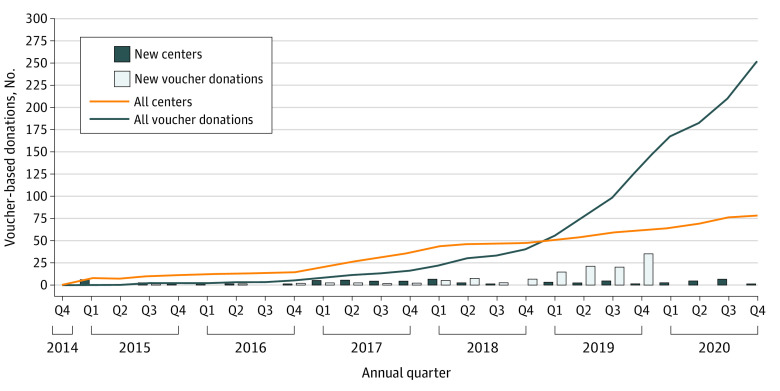

Since the inception of the NKR family voucher program, the number of participating centers and voucher donations has increased rapidly (Figure 1). A total of 79 centers across the US currently offer family voucher–based donation, and 250 family voucher donations have been facilitated. Each voucher donor identified a mean (SD) of 3.3 (1.9) voucher holders (in response to the 2019 NKR Medical Board decision that allowed up to 5 healthy voucher holders per donation), and 818 vouchers were issued. Each donation precipitated a chain with a mean (SD) length of 2.3 (1.6) downstream kidney transplants, facilitating 573 total transplants. Of those, 111 transplants (19.4%) were performed in highly sensitized recipients, with a calculated panel of reactive antibodies of more than 80%.

Figure 1. Patterns in Voucher-Based Kidney Donation and Increases in Donation by Annual Quarter.

A total of 250 voucher-based donations occurred between 2014 and 2020.

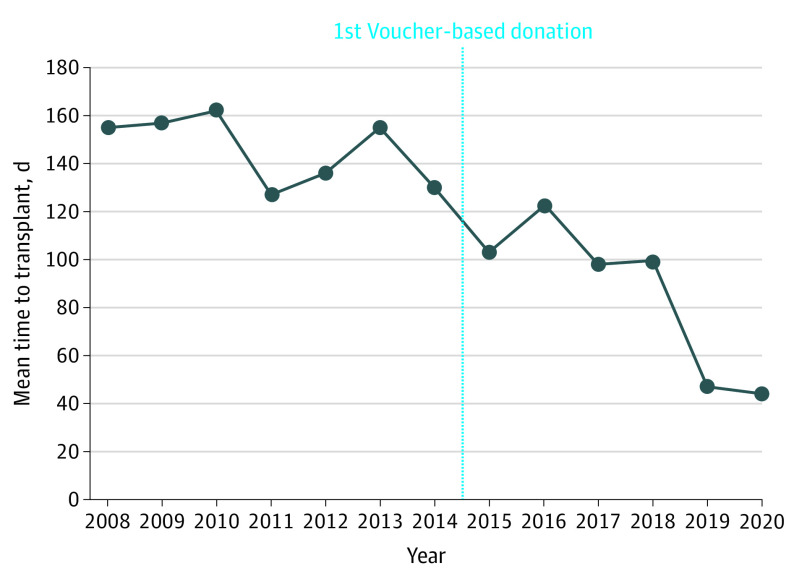

The demographic and clinical characteristics of voucher donors are shown in Table 1. The median age of kidney donation was 46 years (range, 19-78 years), and 19 donors (7.6%) were 65 years or older. Most family voucher donors were female (157 individuals [62.8%]) and White (241 individuals [96.4%]) with blood type O (104 individuals [41.6%]). Before the inception of the family voucher program, incompatible kidney-paired donations spent a mean (SD) of 146.0 (13.8) days waiting for exchange transplant. After the implementation of the family voucher program, waiting times decreased to a mean (SD) of 46.0 (32.4) days, a reduction of more than 3 months. Figure 2 shows the mean waiting times to transplant for kidney-paired donations before and after inception of the family voucher program.

Table 1. Demographic, Clinical, and Transplant-Associated Characteristics of Family Voucher Donors.

| Characteristic | Donors, No. (%) (N = 250) |

|---|---|

| Age at time of donation, median (range), y | 46 (19-78) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 93 (37.2) |

| Female | 157 (62.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 241 (96.4) |

| Black | 2 (0.8) |

| Latino | 1 (0.4) |

| Asian | 6 (2.4) |

| Blood type | |

| A | 109 (43.6) |

| B | 28 (11.2) |

| AB | 9 (3.6) |

| O | 104 (41.6) |

| Recipient waiting time, mean (SD), d | 20.9 (13.4) |

| Transplants facilitated, median (range) | 2.3 (1.0-9.0) |

Figure 2. Mean Waiting Time for Kidney-Paired Donation From 2008 to 2019.

To date, 6 vouchers have been redeemed. Demographic, clinical, and transplant details of these redemptions are shown in Table 2. Of the 6 redeemed vouchers, 3 vouchers (50%) were redeemed by individuals with blood type O. One of the voucher redeemers had 2 previous kidney transplants and was highly sensitized, with calculated panel reactive antibodies of 92%. The time from kidney donation (ie, voucher issuance) to voucher redemption ranged from 167 to 876 days. The time from voucher redemption to kidney transplant ranged from 36 to 155 days.

Table 2. Demographic, Clinical, and Transplant Details of Family-Based Voucher Redemptions.

| Recipient No. | Recipient sex | Recipient age range, y | Recipient race/ethnicity | Recipient blood type | HLA match points | CPRA, % | Relationship of voucher holder to donor | Time from donation to redemption, d | Time from redemption to transplant, d | Transplants facilitated, No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 60-65 | White | A | 25 | 20 | Friend | 876 | 52 | 5 |

| 2 | Female | 50-55 | White | O | 0 | 68 | Spouse | 440 | 122 | 3 |

| 3 | Male | 40-45 | White | O | 0 | 51 | Spouse | 307 | 126 | 3 |

| 4 | Male | 40-45 | White | B | 0 | 0 | Friend | 167 | 41 | 1 |

| 5 | Male | 50-55 | White | O | 10 | 92 | Friend | 359 | 155 | 1 |

| 6 | Male | 65-70 | White | B | 20 | 0 | Spouse | 450 | 36 | 2 |

Abbreviations: CPRA, calculated panel reactive antibodies; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

Discussion

This cohort study found that 250 family voucher–based kidney donations occurred between 2014 and 2021, precipitating living donor chains that produced 573 kidney transplants, and 6 vouchers were redeemed.

The family voucher program enabled donors, often of older age, to leave behind a legacy to a loved one should the need for a transplant arise. A total of 19 family voucher donors (7.6%) were 65 years or older. Although this number represents a minority of donors in this kidney exchange pool, it indicates a considerable increase from baseline, considering that the median age for living kidney donation is 41 years and the proportion of living donors older than 65 years is approximately 1.5%.12 Voucher donation may encourage some potential donors to donate a kidney when they are younger. One consequence of donating a kidney at a younger age is that those donors will spend more of their lives with a single kidney. A 2016 study examined the estimated long-term risks of developing end-stage kidney disease among living kidney donor candidates, reporting that the 15-year observed risks after donation among US kidney donors were 3.5-fold to 5.3-fold higher than the estimated risks in the absence of donation.13

At present, living donor candidacy is handled by individual transplant programs that evaluate potential living donors and accurately assess risks based on family and social history, age, body mass index, comorbidities, and various other donor risk factors to better inform the potential donor and determine living donor candidacy. Transplant recipients who are expected to outlive their currently functioning allograft are also well suited for the voucher program. Patients with a currently functioning kidney allograft who are expected to outlive their transplanted kidney are not in imminent need of a kidney transplant but will likely require one given the approximate 10-year average life span of a living donor allograft.12 A family voucher donation may provide additional security for another transplant if needed in the future.

The voucher program also has intangible social benefits, namely the increased access of minority populations to high-quality organs through transplant chains.14 Over the past decade, transplant chains have allowed greater inclusion of racial and ethnic minorities, with an increasing pattern of racial and ethnic crossover between donors and recipients over time.15 A recent study of more than 141 000 living donations included in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipient database reported an up to 3.3-fold increase in crossover between White individuals and those of minority races and ethnicities.15 The participation of minority populations in the family voucher program needs to be expanded, primarily through the increased dissemination of information and public awareness of the program’s existence. Nevertheless, minority populations benefit from the greater number of transplant chains initiated by voucher donations. As more chains are initiated, more high-quality kidneys can be provided to patients of all demographic backgrounds, including those in racial and ethnic minority groups. The 573 transplants facilitated by these voucher-initiated chains may not have otherwise occurred. Patients on both living and deceased donor waiting lists were able to move up the list to newly vacated positions. In a sense, this program represents the antithesis of the transplant vending occurring in other parts of the world.

Of the 818 family vouchers issued, 6 have been redeemed to date. The low number of redemptions is expected because, by definition, voucher holders do not have an imminent need for a kidney transplant and may never need one. The time from voucher redemption to transplant ranged from 36 to 155 days. The longer waiting times within this range were because of blood type O status. A total of 3 voucher redeemers (50.0%) had blood type O. One of the voucher redeemers had had 2 previous kidney transplants and was highly sensitized (ie, had calculated panel reactive antibodies >90%). This situation represented perhaps the most difficult voucher-holder scenario. Nevertheless, the patient’s third transplant was successfully completed within 5 months after the voucher was redeemed.

The NKR family voucher program has expanded at a substantial rate since its inception in 2014. The rate of voucher donations has steadily increased on an annual basis (Figure 1), and 79 transplant centers throughout the US now participate in the program. The continued expansion of the program introduces concerns that the demand for future redemptions could exceed the supply of available kidneys. To address these concerns, a recent study used a Monte Carlo computer simulation model to estimate the annual number of voucher redemptions relative to the number of kidneys available over a 50-year period.16 In all simulated scenarios, the number of available kidneys exceeded the number of voucher redemptions each year. In 90% of the simulations, the number of available donors exceeded the number of voucher redemptions by more than 6-fold. For each scenario in the simulation study, the researchers purposely reported only the tenth percentile of the coverage ratio value with the aim of providing a highly conservative estimate for each scenario. Although there are certain limitations in any type of simulation study, Monte Carlo simulation models are commonly used to perform risk analyses for complex situations in which it is not possible to mathematically calculate future values for important outcome variables.

Future studies will be aimed at evaluating patterns in voucher-based and standard altruistic donations. Preliminary analysis suggests that the number of living donations among unrelated individuals has been increasing since the inception of the voucher program, while standard altruistic donation has been decreasing, suggesting that voucher-based donation may be increasing at the expense of standard altruistic donation (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Further studies will also be aimed at surveying motivations for participation in voucher-based donation, with the goal of identifying the greatest barriers to living kidney donation and the variables that help to incentivize potential donors.

The NKR has thus far served as the appropriate organization to fulfill voucher contracts. If the NKR becomes insolvent or ceases operations, all participating centers will be obligated to use good faith efforts to coordinate with other centers to provide kidneys to voucher holders. This obligation reflects a center-to-center agreement and is irrevocable, exists in perpetuity, and survives the termination of all NKR contracts.17 Within the broader context of international strategies to increase living kidney donation, advancements in kidney-paired donation and transplant chains have been initiated within the US and expanded internationally. To our knowledge, there are no international strategies in place that use vouchers or an analogous strategy to encourage living donation.

Many barriers exist, including cost, fear of complications, and time away from work; cultural, religious, and familial etiologic factors that preclude living donation also play a major role and cannot be overlooked.18,19 Family vouchers remove an important disincentive to living donation, namely the reluctance to donate lest one’s family member should need a transplant in the future. Family vouchers differ fundamentally from advanced donation because the voucher holder is not yet in need of a transplant and may never be. The initial 7 years of the NKR voucher program have facilitated kidney donations that otherwise may not have occurred. The success of the program may rest on the fact that even the most difficult to match voucher holder received a kidney transplant in a relatively timely manner. The results of the present study indicate the voucher program’s capabilities, which may provide potential donors and transplant professionals with a measure of reassurance.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The analysis was retrospective in nature. In addition, although multicentered in origin, the study examined data from a single kidney exchange consortium.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the family voucher program helped to remove a major disincentive for candidates considering living kidney donation. To date, 250 voucher donations have occurred across the US, precipitating donation chains that produced 573 kidney transplants. All 6 of the patients who redeemed vouchers had timely kidney transplants, which is an indication of the family voucher program’s viability.

eFigure 1. Consent Form for Voucher-Based Living Kidney Donation

eFigure 2. Consent Form for Voucher Recipient

eFigure 3. Kidney Donations by Donor Type

References

- 1.Veale JL, Capron AM, Nassiri N, et al. Vouchers for future kidney transplants to overcome “chronological incompatibility” between living donors and recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101(9):2115-2119. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tushla L, LaPointe Rudow D, Milton J, Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Hays R; American Society of Transplantation . Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1696-1702. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01000115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(4):914-922. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advancing American kidney health. EO No. 13879 of July 10, 2019. Fed Regist. 2019;84(135):33817-33819. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/07/15/2019-15159/advancing-american-kidney-health

- 5.McCormick F, Held PJ, Chertow GM, Peters TG, Roberts JP. Removing disincentives to kidney donation: a quantitative analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(8):1349-1357. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019030242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salomon DR, Langnas AN, Reed AI, Bloom RD, Magee JC, Gaston RS; AST/ASTS Incentives Workshop Group (IWG) . AST/ASTS workshop on increasing organ donation in the United States: creating an “arc of change” from removing disincentives to testing incentives. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(5):1173-1179. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruett TL, Chandraker A. The White House Organ Summit: what it means for our field. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(8):2245-2246. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren PH, Gifford KA, Hong BA, Merion RM, Ojo AO. Development of the National Living Donor Assistance Center: reducing financial disincentives to living organ donation. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(1):76-81. doi: 10.7182/pit2014593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartwright M, Beutler JL. Letter from members of Congress to Health and Human Services secretary urging him to expand the mandate of the National Living Donor Assistance Center. March 8, 2019. Accessed March 20, 2020. https://cartwright.house.gov/sites/cartwright.house.gov/files/letter%20to%20azar.pdf

- 10.Health Resources and Services Administration. Trump administration proposes new rules to increase accountability and availability of the organ supply. HRSA eNews, US Department of Health and Human Services. December 19, 2019. Accessed March 14, 2020. https://www.hrsa.gov/enews/past-issues/2019/december-19

- 11.National Kidney Registry . Info for centers: medical board policies. 2016. Accessed March 20, 2020.http://www.kidneyregistry.org/transplant_center.php#policies

- 12.Davis CL, Cooper M. The state of U.S. living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1873-1880. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01510210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grams ME, Sang Y, Levey AS, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium . Kidney-failure risk projection for the living kidney-donor candidate. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(5):411-421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melcher ML, Leeser DB, Gritsch HA, et al. Chain transplantation: initial experience of a large multicenter program. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(9):2429-2436. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nassiri N, Kwan L, Pearman E, Veale JL. The impact of minorities and immigrants in kidney transplantation. Ann Surg. 2019;270(6):966-968. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper M, Leeser DB, Flechner SM, et al. Ensuring the need is met: a 50-year simulation study of the National Kidney Registry’s family voucher program. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(3):1128-1137. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Kidney Registry . Member Center terms & conditions. National Kidney Registry; 2018. Updated April 23, 2021. Accessed March 20, 2020. https://www.kidneyregistry.org/docs/NKR_MC_Terms_Conditions.pdf

- 18.Wong K, Owen-Smith A, Caskey F, et al. Investigating ethnic disparity in living-donor kidney transplantation in the UK: patient-identified reasons for non-donation among family members. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):3751. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19(4):244-251. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Consent Form for Voucher-Based Living Kidney Donation

eFigure 2. Consent Form for Voucher Recipient

eFigure 3. Kidney Donations by Donor Type