Abstract

Background

Milk feedings can be given via nasogastric tube either intermittently, typically over 10 to 20 minutes every two or three hours, or continuously, using an infusion pump. Although the theoretical benefits and risks of each method have been proposed, their effects on clinically important outcomes remain uncertain.

Objectives

To examine the evidence regarding the effectiveness of continuous versus intermittent bolus tube feeding of milk in preterm infants less than 1500 grams.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to run comprehensive searches in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2020, Issue 7) in the Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions; and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) on 17 July 2020. We also searched clinical trials databases and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs comparing continuous versus intermittent bolus nasogastric milk feeding in preterm infants less than 1500 grams.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed all trials for relevance and risk of bias. We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal to extract data. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence. Primary outcomes were: age at full enteral feedings; feeding intolerance; days to regain birth weight; rate of gain in weight, length and head circumference; and risk of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC).

Main results

We included nine randomised trials (919 infants) in this updated Cochrane Review. One study is awaiting classification. Seven of the nine included trials reported data from infants with a maximum weight of between 1000 grams and 1400 grams. Two of the nine trials included infants weighing up to 1500 grams.

Type(s) of milk feeds varied, including human milk (either mother's own milk or pasteurised donor human milk), preterm formula, or mixed feeding regimens. In some instances, preterm formula was initially diluted. Earlier studies also used water to initiate feedings.

We judged six trials as unclear or high risk of bias for random sequence generation. We judged four trials as unclear for allocation concealment. We judged all trials as high risk of bias for blinding of care givers, and seven as unclear or high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors. We downgraded the certainty of evidence for imprecision, due to low numbers of participants in the trials, and/or wide 95% confidence intervals, and/or for risk of bias.

Continuous compared to intermittent bolus (nasogastric and orogastric tube) milk feeding

Babies receiving continuous feeding may reach full enteral feeding almost one day later than babies receiving intermittent feeding (mean difference (MD) 0.84 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.13 to 1.81; 7 studies, 628 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding in terms of number of days of feeding interruptions (MD ‐3.00 days, 95% CI ‐9.50 to 3.50; 1 study, 171 infants; very low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on days to regain birth weight (MD ‐0.38 days, 95% CI ‐1.16 to 0.41; 6 studies, 610 infants; low‐certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence is low and the 95% confidence interval is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm.

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on rate of gain in weight compared with intermittent feeding (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.46; 5 studies, 433 infants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in length compared with intermittent feeding (MD 0.02 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.08; 5 studies, 433 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in head circumference compared with intermittent feeding (MD 0.01 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.05; 5 studies, 433 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on the risk of NEC compared with intermittent feeding (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.11; 4 studies, 372 infants; low‐certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence is low and the 95% confidence interval is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm.

Authors' conclusions

Although babies receiving continuous feeding may reach full enteral feeding slightly later than babies receiving intermittent feeding, the evidence is of low certainty. However, the clinical risks and benefits of continuous and intermittent nasogastric tube milk feeding cannot be reliably discerned from current available randomised trials. Further research is needed to determine if either feeding method is more appropriate for the initiation of feeds. A rigorous methodology should be adopted, defining feeding protocols and feeding intolerance consistently for all infants. Infants should be stratified according to birth weight and gestation, and possibly according to illness.

Plain language summary

Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for preterm infants less than 1500 grams

Review question

Is continuously feeding through a tube placed into the stomach through the nose or mouth better than feedings given every two to three hours through a tube, in premature, very low birth weight babies?

Background

Preterm infants born weighing less than 1500 grams are not able to coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing. Feeding into the stomach (enteral feeding) helps with gastrointestinal tract development and growth. Therefore, in addition to feeding through a tube into a vein (parenterally), preterm infants may be fed milk through a tube placed either up their nose and into the stomach (nasogastric feeding) or through their mouth and into the stomach (orogastric feeding). Usually, a set amount of milk is given over 10 to 20 minutes every two to three hours (intermittent bolus gavage feeding). Some clinicians prefer to feed preterm infants continuously. Each feeding method has potential beneficial effects but may also have harmful effects.

Study characteristics

We included nine studies that involved 919 babies. One further study is awaiting classification. Seven of the nine included trials reported data from infants with a maximum weight of between 1000 grams and 1400 grams. Two of the nine trials included infants weighing up to 1500 grams. The search is up to date as of 17 July 2020.

Key results

Babies receiving continuous feeding may reach full enteral feeding slightly later than babies receiving intermittent feeding. Full enteral feeding is defined as the baby taking a specified volume of human or formula milk feeds by the required route. This promotes the development of the gastrointestinal system, reduces the risk of infection from intravenous catheters used to deliver parenteral nutrition, and may reduce the length of hospital stay.

It is uncertain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding in terms of number of days to regain birth weight, days of feeding interruptions, and rate of gain in weight.

Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in length or head circumference compared with intermittent feeding.

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on the risk of necrotising enterocolitis (a common and serious intestinal disease among premature babies) compared with intermittent feeding.

Certainty of evidence

The certainty of the evidence is low to very low because of the low numbers of babies in the studies and because the studies were conducted in ways that may have introduced errors in their results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Continuous compared to intermittent bolus (nasogastric and orogastric tube) milk feeding ‐ all preterm infants less than 1500 grams.

| Continuous compared to intermittent bolus (nasogastric and orogastric tube) milk feeding ‐ all preterm infants less than 1500 grams | ||||||

| Patient or population: preterm infants less than 1500 grams Setting: neonatal units in maternity hospitals in the USA, Israel, UK, the Netherlands and India Intervention: continuous Comparison: intermittent bolus (nasogastric and orogastric tube) milk feeding ‐ all infants | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with intermittent bolus (nasogastric and orogastric tube) milk feeding ‐ all infants | Risk with Continuous | |||||

| Age at full enteral feedings (days) | The mean age at full enteral feedings in the intermittent group ranged from 8 to 28.8 days | MD 0.84 days more (0.13 fewer to 1.81 more) | ‐ | 628 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa, b | Continuous feeding may result in a slight increase in age at full enteral feedings compared to intermittent feeding. |

| Feeding intolerance: number of days of feeding interruptions | The mean number of days of feeding interruptions in the intermittent group was 13 | MD 3 days lower (9.5 lower to 3.5 higher) | ‐ | 171 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWc, d | It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on number of days of feeding interruptions compared to bolus feeding. |

| Days to regain birth weight | The mean time to regain birth weight in the intermittent group ranged from 7.8 to 25 days | MD 0.38 days fewer (1.16 fewer to 0.41 more) | ‐ | 610 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa, b | It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on days to regain birth weight compared to intermittent feeding. |

| End of intervention: rate of gain in weight | ‐ | SMD 0.09 SD higher (0.27 lower to 0.46 higher) | ‐ | 433 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb, e | It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on rate of gain in weight compared to intermittent feeding. (SMD < 0.20 = trivial effect; SMD 0.20 to 0.49 = small effect; SMD 0.50 to 0.79 = moderate effect; SMD > 0.80 = large effect). Heterogeneity was significant (P value for Chi2 was 0.004). |

| End of intervention: rate of gain in length (cm/week) | The mean rate of gain in length in the intermittent group ranged from 0.62 to 1.05 cm/week | MD 0.02 cm/week higher (0.04 lower to 0.08 higher) | ‐ | 433 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWe, f | Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in length compared to intermittent feeding. |

| End of intervention: rate of gain in head circumference (cm/week) | The mean rate of gain in head circumference in the intermittent group ranged from 0.53 to 0.99 cm/week | MD 0.01 days higher (0.03 lower to 0.05 higher) | ‐ | 433 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWe, f | Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in head circumference compared to intermittent feeding. |

| Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) | Study population | RR 1.19 (0.67 to 2.11) | 372 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa, g | It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on the risk of NEC compared to intermittent feeding. | |

| 96 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (64 to 202) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; NEC: necrotising enterocolitis | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: unclear randomisation and allocation concealment; high risk of bias due to lack of blinding of care givers and due to incomplete outcome data bDowngraded one level for imprecision: wide 95% CI spans possible benefit and possible harm cDowngraded one level for risk of bias: unclear randomisation and high risk of bias due to lack of blinding of care givers dDowngraded two levels for imprecision: very few infants and wide 95% CI that is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm eDowngraded two levels for risk of bias: unclear randomisation, and high risk of bias due to lack of blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting fAlthough the 95% CI spans possible benefit and possible harm, we did not downgrade for imprecision because the difference on either side would not be clinically important gDowngraded one level for imprecision: few events and wide 95% CI that is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm

Background

Description of the condition

Tube feeding is necessary for most preterm infants less than 1500 grams because of their inability to coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing (Bertoncelli 2012; Schanler 1999), and the danger of aspiration (Bertoncelli 2012; Valman 1972).

Description of the intervention

The conventional tube feeding method is intermittent bolus gavage feeding, where a prescribed volume of milk is given over a short period of time (Aynsley‐Green 1982), usually over 10 to 20 minutes by gravity. The first reported use of the continuous nasogastric tube feeding method for preterm infants was in 1972 (Valman 1972). Some clinicians prefer the continuous nasogastric feeding method for feeding preterm infants less than 1300 grams birth weight. However, intermittent bolus gavage feeding is the method more commonly used in practice (Toce 1987).

How the intervention might work

Theoretical risks and benefits of both continuous nasogastric milk feeding and intermittent bolus milk feeding have been proposed. Continuous nasogastric feedings may improve energy efficiency (by increasing energy absorbed and decreasing energy expenditure) (Grant 1991), reduce feeding intolerance, improve nutrient absorption, and improve growth (Toce 1987). However, continuous infusion of milk into the gastrointestinal tract could alter the cyclical pattern of release of gastrointestinal tract hormones, which might affect metabolic homeostasis, and growth (Aynsley‐Green 1982), and may result in loss of nutrients from feeds into tubing which might affect growth and nutrient accretion (Rogers 2010). Furthermore, a properly functioning lower oesophageal sphincter is an important barrier against the reflux of stomach contents into the oesophagus and aspiration. Apnoea, reflux and aspiration may be compounded in the preterm infant receiving continuous nasogastric feedings (Corvaglia 2014; Newell 1988). Not only do these infants have reduced lower oesophageal sphincter pressure (Newell 1988), but the nasogastric tube remains in situ preventing complete closure of the sphincter.

Milk feedings given by the intermittent bolus gavage method are thought to be more physiologic because they promote the cyclical surges of gastrointestinal tract hormones normally seen in healthy term infants (Aynsley‐Green 1982; Aynsley‐Green 1990). Gastrointestinal hormones such as gastrin, gastric inhibitory peptide, and enteroglucagon are trophic and require the presence of intraluminal nutrients to stimulate secretion. Surges in plasma concentrations of gastrointestinal tract hormones postnatally may be important for gastrointestinal tract development (Aynsley‐Green 1989; Lucas 1986). On the other hand, functional limitations of the preterm infant's gastrointestinal system, such as delayed gastric emptying or intestinal transit, could hinder the preterm infant's ability to handle bolus milk feeds, resulting in feeding intolerance. Additionally, this feeding regimen alternates between periods of feeding and fasting which may challenge the preterm infant's ability to maintain metabolic homeostasis and, therefore, decrease growth (Aynsley‐Green 1982).

The effects of the feeding method on feeding tolerance, weight gain, or days to regain birth weight were examined in two non‐randomised controlled trials (Krishnan 1981; Urrutia 1983). In a retrospective study, Krishnan 1981 found that infants fed milk by continuous nasogastric tube feeding reached enteral intakes of 90 kcal/kg/day almost twice as quickly as those infants fed milk by intermittent bolus gavage feeding (16 +/‐ 6 versus 26 +/‐ 17 days, respectively). In addition, infants in the continuous group achieved steady weight gain sooner than infants in the intermittent group (24 +/‐ 10 versus 32 +/‐ 14 days). Unfortunately, these findings are difficult to interpret due to study design and methodologic limitations. First, the non‐random assignment of infants allows for selection bias. Second, energy intake was not controlled and may have influenced feeding tolerance and weight gain. Third, a convenience sample rather than a predetermined sample size was used, making it difficult to achieve both clinical and statistical significance in a study. Hence, it is difficult to make generalisations regarding these findings to similar populations of infants (Raudonis 1995).

Urrutia 1983 conducted a non‐randomised prospective study of continuous versus intermittent nasogastric tube milk feedings. They found no difference between groups in days to regain birth weight. These findings are also difficult to interpret because infants were allocated to the continuous or intermittent group based on neonatologists' preference rather than random assignment, and a convenience sample was used.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to determine the clinical risks and benefits of each method of feeding to enable clinicians to make informed decisions regarding the most appropriate feeding method for an individual infant. New studies have been completed since the previous version of this review. Therefore, it is important to incorporate their findings to ensure the review provides up‐to‐date evidence.

Objectives

To examine the evidence regarding the effectiveness of continuous versus intermittent bolus tube feeding of milk in preterm infants less than 1500 grams.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised trials which compared continuous versus intermittent tube milk feeding, delivered via either the nasogastric or orogastric route, as primary feeding strategies in preterm infants less than 1500 grams.

Types of participants

We included infants born with birth weight less than 1500 grams who had no prior history of feeding or feeding intolerance, and no congenital anomalies that might interfere with establishing enteral feeds.

Types of interventions

We included continuous nasogastric feeding versus intermittent feeding with human milk or infant formula for the initiation of feeds and advancement to full enteral feeds. We included trials where infants in the comparator group received intermittent feeding through either nasogastric or orogastric tube feeding.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Age at full enteral feedings (days)

Feeding intolerance as measured by number of days of feeding interruptions

Days to regain birth weight

Rate of gain in weight (grams/week)

Rate of gain in length (cm/week)

Rate of gain in head circumference (cm/week)

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), including suspected and confirmed (Bell's Stage II or greater)

Secondary outcomes

Days to discharge to referral hospital or home

Episodes of apnoea

Days on total parenteral nutrition

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a comprehensive update search in July 2020, including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2020, Issue 7) in the Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions (1 January 2011 to 17 July 2020); and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, via EBSCOhost; 1 January 2011 to 17 July 2020). We have included the search strategies for each database in Appendix 1. We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched clinical trial registries for ongoing or recently completed trials. We searched the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/), and the United States' National Library of Medicine’s ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), via Cochrane CENTRAL. Additionally, we searched the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/) from 2011 onwards, the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR), EU Clinical Trials Register (EU‐CTR), and the Clinical Trial Registry – India (CTRI) (the latter three from February 2020 onwards) for any unique trials not found through the Cochrane CENTRAL search.

This is the third update of this review. Our previous search details are listed in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We cross‐referenced relevant literature, including identified trials and existing review articles, in order to identify additional relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

The systematic review followed the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020, hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook).

Selection of studies

We used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to help assess the search results. Screen4Me comprises three components: known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and been labelled as an RCT or as Not an RCT; the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs; and if appropriate, Cochrane Crowd – Cochrane’s citizen science platform where the Crowd help to identify and describe health evidence.

For more information about Screen4Me, please go to community.cochrane.org/organizational-info/resources/resources-groups/information-specialists-portal/crs-videos-and-quick-reference-guides#Screen4Me. Detailed information regarding evaluations of the Screen4Me components can be found in the following publications: Marshall 2018; Noel‐Storr 2020; Noel‐Storr 2021; and Thomas 2020.

At least two review authors independently assessed relevance of all the articles that were retrieved from the complete search. Criteria for relevance included trials that utilised experimental or quasi‐experimental designs, compared continuous nasogastric tube milk feeding versus intermittent bolus nasogastric tube milk feeding, and reviewed clinically relevant outcomes as stated in the objectives.

We resolved differences through discussion and consensus of the review authors.

Data extraction and management

Two of the three review authors (SSP, LC, or FS) independently extracted data from studies. We resolved discrepancies through discussion, and if required, by consulting the third review author. We entered data into Review Manager software (Review Manager 2020), and checked for accuracy.

We contacted investigators for additional information or clarification, or both, where necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two of the three review authors (SSP, LC, or FS) independently assessed the risk of bias of all included trials using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011), for these domains:

sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective reporting (reporting bias);

any other bias.

We resolved any disagreements through discussion or by consulting a third assessor. See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal. We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). We analysed categorical outcomes such as the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis using risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We reported mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs for continuous outcomes such as days of feeding intolerance.

Where different scales were used to measure continuous outcomes, we combined the data using standardised mean difference (SMD), with the following interpretation:

SMD greater than or equal to 0.2 and less than 0.5 = small effect;

SMD greater than or equal to 0.5 and less than 0.8 = moderate effect;

SMD greater than 0.8 = large effect.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating infant in individually randomised trials, and an infant was considered only once in the analysis. For trials with three arms (e.g. continuous feeding versus bolus feeding by gravity versus bolus feeding by infusion), where continuous outcomes were reported, we divided the intervention group denominator by two in order to avoid double‐counting in the meta‐analysis.

The participating neonatal unit or section of a neonatal unit or hospital was the unit of analysis in cluster‐randomised trials. In future updates, if we identify eligible cluster‐RCTs, we will analyse them using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from a similar trial or from a study with a similar population, as described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2020). If we use ICCs from a similar trial or from a study with a similar population, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC.

We planned to only combine results from cluster‐RCTs with individually randomised trials in the same analysis if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs, and the interaction between the effect of the intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely. We planned to investigate any possible heterogeneity in the randomisation unit, and perform sensitivity analysis to investigate possible effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

We made every effort to contact study authors to ask for data that were missing from their published reports; for example, where P values only were reported instead of presenting the data in full.

Where studies reported median (interquartile range (IQR)), we used the methods described in Wan 2014 to convert to mean and SD. If there were no substantial differences between the median and mean, we included the mean and standard deviation (SD) in meta‐analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated the treatment effects of individual trials and examined heterogeneity between trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, according to the following guidance in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2020).

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

If we detected statistical heterogeneity, we explored the possible causes (for example, differences in risk of bias, participants, intervention regimens, or outcome assessments).

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if we identify 10 or more trials for meta‐analysis, we will assess possible publication bias by inspection of a funnel plot. If we uncover reporting bias that could, in the opinion of the review authors, introduce serious bias, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of including and excluding these studies in the analysis.

Data synthesis

Where we identified studies that were similar enough in terms of population, intervention and comparator, we conducted fixed‐effect meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). Where we identified substantial statistical heterogeneity, we conducted random‐effects meta‐analysis.

For estimates of typical relative risk and risk difference, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method. For measured quantities, we used the inverse‐variance method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for primary outcomes based on birth weight groups (< 1000 grams, 1000 to 1249 grams and 1250 to 1499 grams) where there were sufficient data.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes in the following situations.

We removed studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were judged as unclear or high risk.

Where the analysis included trials whose interventions were delivered by a mix of nasogastric and orogastric feeding, we removed those trials, leaving only data from infants fed by nasogastric feeding in the analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence of the following (clinically relevant) outcomes.

Age at full enteral feedings (days).

Feeding intolerance as measured by number of days of feeding interruptions.

Days to regain birth weight.

Rate of gain in weight (grams/week).

Rate of gain in length (cm/week).

Rate of gain in head circumference (cm/week).

Necrotising enterocolitis, including suspected and confirmed (Bell's Stage II or greater).

Two review authors (SSP and FS) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create Table 1 to report the certainty of the evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence as one of four grades.

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

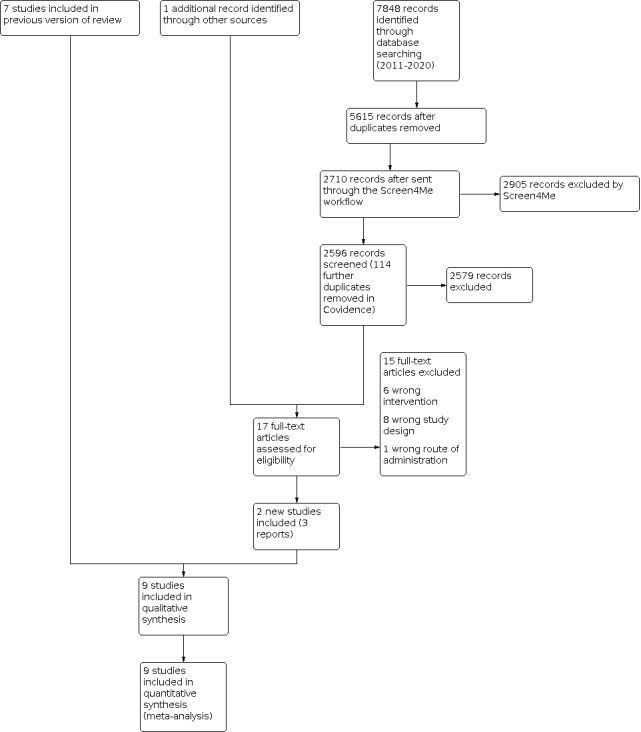

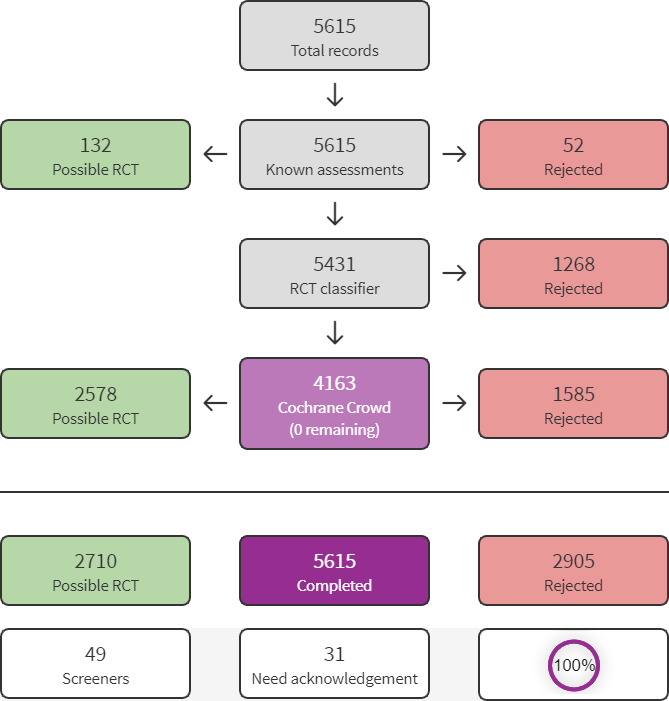

Our search identified a total of 7848 search results (see Figure 1). In assessing the studies, we used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to help identify potential reports of randomised trials. The results of the Screen4Me assessment process can be seen in Figure 2. We then assessed the remaining 2596 records left after Screen4Me. The review author team (at least two of SSP, LC and FS) screened these records. From these, we obtained 17 full texts for further screening. We identified two new studies (three reports) to include in the review (Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015).

1.

Study flow diagram

2.

Screen4Me summary diagram

Included studies

We included nine studies (919 randomised infants) in this updated review.

See Characteristics of included studies for full details.

Study design

All but one of the nine included studies are RCTs (Toce 1987). Toce 1987 used alternative assignment rather than randomisation to allocate infants to treatment groups.

Setting

Eight studies took place in high‐resource settings: four in the USA (Akintorin 1997; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987); and one each in Israel (Dollberg 2000); Sweden (Dsilna 2005); the United Kingdom (UK) (Macdonald 1992); and the Netherlands (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). One study took place in a lower‐middle‐income setting, India (Neelam 2018).

Participants

Three studies included infants up to 1250 grams (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Neelam 2018). In one study, the upper weight limit was 1200 grams (Dsilna 2005), and in another the limit was 1400 grams (Macdonald 1992). Two studies included infants weighing up to 1500 grams (Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987). In one study, the upper weight limit was 1750 grams; however, the authors provided data from the subgroup of infants weighing less than 1000 grams which met our inclusion criteria of infants weighing less than 1500 grams (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). One study did not specify an upper weight limit, but it included only babies between 26 and 30 weeks' gestation (Schanler 1999). Four other studies included infants only within specific gestational age ranges: 24 to 29 weeks (Dsilna 2005); 27 to 34 weeks (Silvestre 1996); and up to 32 weeks (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Neelam 2018). All studies excluded infants with major congenital anomalies.

Sample size

Sample sizes ranged from 28 randomised infants (Dollberg 2000), to 250 (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015).

Interventions

In five studies, the continuous feeds were described as being delivered by infusion pump (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Dsilna 2005; Neelam 2018; Toce 1987). One study described the continuous feeding method as semi‐continuous feeds every quarter of an hour, volume fed by gravity every 15 minutes over a 24‐hour period (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). Three studies did not describe the continuous feeding method in detail (Macdonald 1992; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996).

In the comparator groups, the infants received nasogastric bolus feeds by gravity. In one study, the comparator group had either an orogastric tube placed for each feeding or indwelling nasogastric tube feedings (Dsilna 2005). In the comparator groups, the feeds were given for 15 to 30 minutes. The feeds were given every three hours (Akintorin 1997; Dsilna 2005; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987), every two hours (Neelam 2018), or every two hours for infants who weighed 501 grams to 750 grams, and every three hours for all other infants (Dollberg 2000). In one study, the frequency of bolus feeding was unclear (Macdonald 1992).

Type(s) of milk feeds varied, including human milk (Dollberg 2000; Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999), either mother's own milk or pasteurised donor human milk (Dsilna 2005), preterm formula (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987), and mixed feeding regimens (Dollberg 2000). In some instances, preterm formula was initially diluted (Dollberg 2000; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987). Earlier studies also used water to initiate feedings (Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987).

Feeding for infants was initiated at the following times.

On day of birth (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015).

Within 30 hours of birth (Dsilna 2005).

Day two after birth (Macdonald 1992).

Day two or three after birth (Silvestre 1996).

At less than 96 hours of age (Schanler 1999).

Between day two and five after birth (Dollberg 2000).

Before day 10 after birth (Akintorin 1997).

Two studies did not specify the timing of feeds in the protocol (Neelam 2018; Toce 1987).

Outcomes

All studies except two reported age at full enteral feedings (Macdonald 1992; Toce 1987).

Other outcomes were reported by at least one study:

number of days of feeding interruptions: one study (Schanler 1999);

days to regain birth weight: six studies (Akintorin 1997;Dsilna 2005 Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996);

rate of gain in weight: five studies (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987);

rate of gain in length: five studies (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987);

rate of gain in head circumference: five studies (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987);

necrotising enterocolitis: four studies (Akintorin 1997; Dsilna 2005; Schanler 1999; Toce 1987);

days to discharge: two studies (Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996);

apnoea: two studies (Schanler 1999; Toce 1987);

days on total parenteral nutrition: two studies (Dsilna 2005; Schanler 1999).

Study dates

The majority of the studies took place in the 1990s (Akintorin 1997; Macdonald 1992; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996), and 2000s (Dollberg 2000; Dsilna 2005; Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). One study took place in the 1980s (Toce 1987).

Funding sources

One study received funding from a commercial company (Toce 1987); three studies received funding from government or charitable grants (Dsilna 2005; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996); and the remaining studies did not report any details about their funding sources.

Declarations of interest

One study stated that the authors had no conflicts of interest to declare (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015), while the remaining studies did not mention authors' declarations of interest at all.

Excluded studies

We excluded 15 studies because they were either not eligible study designs, they did not include eligible interventions, or the route of administration was not eligible. See Characteristics of excluded studies for further information.

Studies awaiting classification

One study is awaiting classification (Corbin 2011). We contacted the trial investigators in November 2020 to ask for information about the inclusion criteria for trial participants, but we have not received any response.

See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for further information.

Risk of bias in included studies

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Three studies described using robust random sequence generation methods and were judged as low risk of bias (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Dsilna 2005). Five studies did not provide sufficient information about their randomisation methods, so we judged them as unclear risk of bias (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999; Silvestre 1996). One study used alternative allocation and was judged as high risk of bias because the sequence of allocation to treatment was not truly random (Toce 1987).

Allocation concealment

We judged five studies as low risk of bias because they reported using methods such as opaque sealed envelopes to ensure allocation to treatment could not be predicted (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Dsilna 2005; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999). The other studies did not provide enough information about allocation concealment methods used, so we judged them as unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and care givers

We judged all studies as high risk of bias because blinding of participants and care givers was not possible in any of the trials, and knowledge of treatment allocation could have an influence on the outcomes.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Two studies reported using blinded outcome assessors, so we judged them as low risk of bias (Dsilna 2005; Schanler 1999). Two studies reported that outcome assessment was not blinded, so we judged them as high risk of bias (Dollberg 2000; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). The other studies provided insufficient information about blinding of outcome assessment, so we judged them as unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Five studies had low and non‐differential attrition, so we judged them as low risk of bias (Akintorin 1997; Dsilna 2005; Macdonald 1992; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Schanler 1999). We judged the other studies as high risk of bias because they reported high or differential attrition, or both (Dollberg 2000; Neelam 2018; Silvestre 1996), or because they did not explain substantial amounts of missing data (Toce 1987).

Selective reporting

We judged two studies as high risk of bias because they did not report all of the outcomes that they stated would be measured (Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). We judged the remaining studies as low risk of bias, because despite the lack of published protocols or prospective trial registrations, they reported in full, all outcomes that would be reasonably expected. Additionally, all of the studies we judged as low risk of reporting bias were published before 2010 and would not be expected to have published protocols or to have been registered prospectively.

Other potential sources of bias

None of the studies had any other aspects that could indicate other sources of bias, so we judged all of them as low risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Age at full enteral feedings (days)

Babies receiving continuous feeding may reach full enteral feeding slightly later than babies receiving intermittent feeding (MD 0.84 days, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 1.81; 7 studies, 628 infants; I2 = 41%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). For transparency, we have also reported the median (IQR) data from the two studies whose data we converted to mean (SD) (Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015) (see Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 1: Age at full enteral feedings (days)

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 2: Age at full enteral feedings (days) (median, IQR)

| Age at full enteral feedings (days) (median, IQR) | |||

| Study | Continuous infusion | Intermittent bolus | Measure |

| Neelam 2018 | 16 days (12‐23.2) 35 infants |

by infusion: 16 (14.5‐26), 33 infants by gravity: 15 (11.5‐ 17.5), 29 infants |

Median (IQR) |

| Rövekamp‐Abels 2015 | 8 days (7‐11) 49 infants |

8 days (6‐10) 47 infants |

Median (IQR) |

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies whose comparator groups included infants who received orogastric feeding did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD 0.41 days, 95% CI ‐0.60 to 1.42; 5 studies, 336 infants; I2 = 48%; Analysis 1.3). For this sensitivity analysis, we removed all the data from two studies (Neelam 2018; Schanler 1999), and from another study we removed the comparison between the continuous nasogastric and intermittent orogastric groups (Dsilna 2005).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 3: Age at full enteral feedings (days): sensitivity analysis removing trials with mix of nasogastric and orogastric

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Silvestre 1996), changed the direction of effect but made it less precise, with a wide 95% CI that is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm (MD 1.33 days, 95% CI ‐1.17 to 3.84; 4 studies, 342 infants; I2 = 64%).

The test for subgroup differences did not suggest there may be variation in effect according to birth weight (P = 0.09, I2 = 54.4%; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 4: Age at full enteral feedings (days): subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis has five fewer infants in the intervention arm and 13 fewer in the control arm, compared with the main analysis. This discrepancy is because one study provided data for infants in the less than 1000 grams birth weight category but not for infants in the upper birth weight categories (Dsilna 2005).

Feeding intolerance: number of days of feeding interruptions

It is uncertain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding in terms of number of days of feeding interruptions (MD ‐3.00, 95% CI ‐9.50 to 3.50; 1 study, 171 infants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5). Only one trial reported number of days of feeding interruptions, so we could not conduct sensitivity or subgroup analysis.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 5: Feeding intolerance: number of days of feeding interruptions

Another trial reported the number of infants with feeding interruptions during the study: 44/54 in the continuous group and 36/54 in the intermittent group (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015).

One trial reported 17/35 infants in the continuous group and 36/62 in the intermittent group with any kind of feeding intolerance during the study period (https://revman.cochrane.org/#/074400092812461148/htmlView/6.49.7#STD‐Neelam‐2018).

Days to regain birth weight

It is uncertain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding in terms of the number of days to regain birth weight (MD ‐0.38 days, 95% CI ‐1.16 to 0.41; 6 studies, 610 infants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6). The certainty of evidence is low and the 95% CI includes possible benefit and possible harm.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 6: Days to regain birth weight

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies whose comparator groups included infants who received orogastric feeding did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD ‐0.42 days, 95% CI ‐1.27 to 0.43; 5 studies, 489 infants; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.7). For this sensitivity analysis, we removed all the data from one study (Neelam 2018), and from another study we removed the comparison between the continuous nasogastric and intermittent orogastric groups (Dsilna 2005).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 7: Days to regain birthweight: sensitivity analysis removing trials with mix of nasogastric and orogastric

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Neelam 2018; Rövekamp‐Abels 2015; Silvestre 1996), did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD ‐0.41 days, 95% CI ‐1.49 to 0.67; 3 studies, 319 infants; I2 = 0%).

The test for subgroup differences did not suggest there may be variation in effect according to birth weight (P = 0.99; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.8). The subgroup analysis has five fewer infants in the intervention arm and 13 fewer in the control arm, compared with the main analysis. This discrepancy is because one study provided data for infants in the less than 1000 grams birth weight category but not for infants in the upper birth weight categories (Dsilna 2005).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 8: Days to regain birth weight: subgroup analysis

Rate of gain in weight

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on rate of gain in weight compared with intermittent feeding (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.46; 5 studies, 433 infants; I2 = 66%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.9). We used the random‐effects model for this analysis due to the high I2. According to the interpretation of SMD we have used, this effect estimate does not suggest an important difference between the groups. However, since the evidence is very low certainty, it is very likely that further studies might change the effect estimate substantially.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 9: End of intervention: rate of gain in weight

The statistical heterogeneity may be due to the results in the lower birth weight infants, which favour continuous feeding, while the results in higher birth weight infants and the trials that did not stratify by birth weight have 95% confidence intervals that are consistent with possible benefit and possible harm.

Sensitivity analysis removing one trial that used orogastric feeding (Neelam 2018), did not change the effect estimate substantially (SMD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.47).

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987), changed the effect estimate substantially such that continuous feeding may lead to less gain in weight compared to intermittent feeding, with the interpretation that SMD equal to or greater than 0.2 and less than 0.5 suggests a moderate effect (SMD ‐0.44, 95% CI ‐0.74 to ‐0.13; 1 study, 171 infants).

The result of the test for subgroup differences suggests there may be a variation in effect between birth weight categories (P = 0.01, I2 = 72.4%). However, since only one trial (93 infants) provided data stratified by birth weight category, the difference between subgroups may be due to chance.

In addition to rate of gain in weight at the end of the intervention, one trial also reported rate of gain in weight at discharge (MD ‐0.18 days, 95% CI ‐1.61 to 1.25; 1 study, 92 infants; Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 10: At discharge: rate of gain in weight g/kg/day

Rate of gain in length

Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in length compared with intermittent feeding (MD 0.02 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.08; 5 studies, 433 infants; I2 = 3%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 11: End of intervention: rate of gain in length (cm/week)

Sensitivity analysis removing one trial that used a mix of nasogastric and orogastric feeding (Neelam 2018), did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD 0.07 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.15; 4 studies, 341 infants; I2 = 0%).

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987), did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD 0.10 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.29; 1 study, 171 infants).

The test for subgroup differences did not suggest there may be variation in effect according to birth weight (P = 0.54, I2 = 0%).

In addition to rate of gain in length at the end of the intervention, one trial also reported rate of gain in length at discharge (MD ‐0.01 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.05; 1 study, 125 infants; Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 12: At discharge: rate of gain in length (cm/week)

Rate of gain in head circumference

Continuous feeding may result in little to no difference in rate of gain in head circumference compared with intermittent feeding (MD 0.01 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.05; 5 studies, 433 infants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 13: End of intervention: rate of gain in head circumference (cm/week)

Sensitivity analysis removing one trial that used a mix of nasogastric and orogastric feeding (Neelam 2018), did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD ‐0.00 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.05; 4 studies, 341 infants; I2 = 0%).

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Macdonald 1992; Neelam 2018; Silvestre 1996; Toce 1987), did not change the effect estimate substantially (MD ‐0.04 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.04; 1 study, 171 infants).

The test for subgroup differences did not suggest there may be variation in effect according to birth weight (P = 0.72, I2 = 0%).

In addition to rate of gain in head circumference at the end of the intervention, one trial also reported rate of gain in head circumference at discharge (MD 0.10 cm/week, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.16; 1 study, 91 infants; Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 14: At discharge: rate of gain in head circumference (cm/week)

Necrotising enterocolitis

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on the risk of necrotising enterocolitis compared with intermittent feeding (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.11; 4 studies, 372 infants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.15). The evidence is low certainty and the 95% confidence interval is consistent with possible benefit and possible harm.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 15: Necrotolising enterocolitis

One trial reported zero cases of confirmed necrotising enterocolitis (Bell's stage II or greater) in both arms (Silvestre 1996; 0/45 and 0/48).

Sensitivity analysis removing the data from infants receiving orogastric feeding (Dsilna 2005), did not change the effect estimate substantially (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.64 to 2.08).

Sensitivity analysis removing the studies where more than half of the risk of bias domains were unclear or high risk (Toce 1987), did not change the effect estimate substantially (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.20; 3 studies, 319 infants; I2 = 0%).

None of the studies contributing data to this outcome reported data by birth weight category, so we did not do subgroup analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Days to discharge to referral hospital or home

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on days to discharge compared to intermittent feeding (MD ‐1.55 days, 95% CI ‐5.13 to 2.02; 2 studies, 264 infants; I2 = 28%; Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 16: Days to discharge

Apnoea

It is uncertain if continuous feeding has any effect on the number of apnoea episodes compared with intermittent feeding (SMD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.44 to 0.60; Analysis 1.17). Since this SMD is less than 0.20, and the 95% CI spans little effect to possible harm, we cannot be certain about this result.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 17: Apnoea episodes

Another study reported little difference in median (IQR) episodes of apnoea between the two groups (Analysis 1.18) (Rövekamp‐Abels 2015). We have not combined these data with those reported as mean (SD) because we judged the converted means were so different from the data reported as medians that it would be misleading to include them in the analysis (converted means: 4.03 and 4.4 episodes).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 18: Number of apnoea episodes per day (median, IQR)

| Number of apnoea episodes per day (median, IQR) | ||

| Study | Continuous infusion | Intermittent bolus |

| Rövekamp‐Abels 2015 | 3.9 (2.5‐5.7) 54 infants |

3.6 (2.5‐7.1) 54 infants |

Days on total parenteral nutrition

Continuous feeding may result in fewer days on total parenteral nutrition compared to intermittent feeding (MD ‐4.77 days, 95% CI ‐9.52 to ‐0.03; 2 studies, 239 infants; I2 = 30%; Analysis 1.19).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding, Outcome 19: Days on total parenteral nutrition

Discussion

Summary of main results

This updated review now includes evidence from nine trials (involving 919 infants), compared to seven trials (involving 511 infants) in the previous version of this review (Premji 2011).

We found low‐certainty evidence that continuous feeding may result in infants reaching full enteral feeding slightly later than with intermittent feeding. There may be little to no difference between continuous and intermittent feeding in terms of rate of gain in length and head circumference.

It is uncertain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding in terms of number of days to regain birth weight and risk of necrotising enterocolitis, because the certainty of evidence is low and the 95% confidence intervals are consistent with possible benefit and possible harm.

The evidence regarding feeding intolerance, measured by number of days of feeding interruptions, and rate of gain in weight is very low certainty. Therefore, we cannot be certain if there is any difference between continuous feeding and intermittent feeding for these two outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Despite the inclusion of data from an additional 408 infants, compared with the previous version of this review, the evidence remains largely uncertain about the effect of continuous feeding compared with intermittent feeding for preterm infants weighing less than 1500 grams.

Several of the studies in this review utilised the occurrence of gastric residuals as a major criterion for determining feeding intolerance. Three studies reported higher incidence of residuals in infants fed by continuous tube feeding which might have resulted in more feeding interruptions or slower increases in feeds, or both, thereby increasing the time taken to reach full feeds (Akintorin 1997; Dollberg 2000; Schanler 1999). The necessity of checking gastric residuals has been challenged in recent years, as there is a paucity of evidence to support this practice, and wide variation in practice regarding acceptable volumes of residuals, and how they should be managed (Li 2014). One recent study of preterm infants born at 32 weeks' gestation or earlier and weighing 1250 grams or more at birth, found that not checking gastric residuals prior to feeding as compared with checking residuals prior to feeding was associated with more rapid advancement of enteral feeding and higher intake of nutrients at some time points (Rysavy 2020). Therefore, a change in the practice of using gastric residuals to guide feeding advancement in preterm infants might affect outcomes such as feeding tolerance and time to full feeds when comparing continuous tube feeding to intermittent bolus tube feeding.

In practice, when utilising continuous feedings of human milk, concerns have been raised related to a loss of nutrients when human milk sits in tubing for a length of time (typically four hours). This has been studied in vitro by mimicking intermittent and continuous feedings using available feeding systems, and measuring nutrient contents of feedings before and after running feeds through a feeding system set to mimic either continuous or intermittent feedings. One study comparing nutrient loss suggested that continuous feeding of fortified human milk resulted in significant losses of calcium, phosphorus, protein, and fat, especially when using a bovine source human milk fortifier (Rogers 2010). Another in vitro study measured nutrient loss during continuous feedings with or without the use of a priming volume of feeding which would be discarded after the feeding. Researchers found that they could reduce the loss of fat (decreased from 16.7% to 8.2%), protein (decreased from 3.4% to 0), and calories (decreased from 9.2% to 3.3%) by preparing and infusing the exact feeding volume using air to clear the milk from the tubing at the end of the feed, as compared to discarding the priming volume of milk which remained in the tubing at the end of the feeding (Davidson 2020). These studies were performed in vitro and therefore, could not assess the impact of continuous feedings on outcomes such as growth and nutrient retention, and further studies to address this issue would be useful. In the current systematic review, the evidence is uncertain about differences in the rates of growth in weight, length, or head circumference in infants fed by either continuous or intermittent tube feeding. The use of parenteral nutrition to supplement enteral nutrition while establishing feedings might have diminished any potential variation.

Quality of the evidence

The assessment of risk of bias was limited by lack of information reported in the trials, particularly in terms of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessors. It was not possible for care givers to be blinded to group allocation in any of the studies, which could have had an impact on outcomes. There was high risk of bias in terms of incomplete outcome data in four of the nine trials, and we judged two trials to be at high risk of selective reporting.

As a result of serious concerns about risk of bias, we downgraded the certainty of the evidence. We also downgraded the certainty of evidence because of serious concerns about imprecision due to low numbers of infants in the included trials, wide confidence intervals leading to lack of precision in the effect estimates, or both.

Potential biases in the review process

To reduce the risk of bias in the review, we conducted a comprehensive literature search with no limitations in terms of language of publication or publication status. While we recognise that there may be studies that were not retrieved by our literature searches, we made every attempt to identify relevant unpublished studies and to obtain missing data from published studies.

Two review authors independently carried out study selection, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, and GRADE assessment, with recourse to the third review author to resolve any discrepancies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We were able to locate only one systematic review examining feeding methods (continuous versus intermittent bolus) in low birth weight infants under 2500 grams (Wang 2020). This systematic review also reported that infants (n = 707) fed by continuous feeding method took longer to achieve full feedings (weighted mean difference 0.98 days, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.71; P = 0.008) when compared to those fed by intermittent bolus feeding method.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although babies receiving continuous feeding may reach full enteral feeding slightly later than babies receiving intermittent feeding, the evidence is of low certainty. However, the clinical risks and benefits of continuous and intermittent nasogastric tube milk feeding cannot be reliably discerned from current available randomised trials.

Implications for research.

Further research is needed to determine if either feeding method is more appropriate for the initiation of feeds, and if either method may be better tolerated by infants who experience feeding intolerance, a question not addressed in the current review. A rigorous methodology should be adopted, defining feeding protocols and feeding intolerance consistently for all infants. Infants should be stratified according to birth weight and gestation, and possibly according to illness.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 July 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed |

|

| 17 July 2020 | New search has been performed |

|

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1999 Review first published: Issue 1, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 August 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Search was updated in July 2011. No new trials identified. Risk of Bias tables completed. No changes to conclusions. |

| 4 August 2011 | New search has been performed | This review updates the existing review "Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500 grams", published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Premji 2004). |

| 5 February 2008 | New search has been performed | This review updates the existing review "Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500 grams", published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4, 2004 (Premji 2004). Two new trials were identified as a result of the most recent search completed October 26, 2007. The previous conclusion of no significant difference in somatic growth of infants fed by continuous versus intermittent bolus tube feeds remains unchanged. |

| 15 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 5 March 2004 | New search has been performed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cochrane Neonatal: Colleen Ovelman, Managing Editor, Jane Cracknell, Assistant Managing Editor, Roger Soll, Co‐coordinating editor, and William McGuire, Co‐coordinating Editor, who provided editorial and administrative support. Carol Friesen, Information Specialist, designed and conducted the literature searches, and Colleen Ovelman peer reviewed the Ovid MEDLINE search strategy.

Sarah Hodgkinson and William McGuire have peer reviewed and offered feedback on this review.

We thank Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation Foundation for funding the initial review.

We would like to acknowledge and thank the following people for their help in assessing the search results for this review via Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow: Anna Noel‐Storr, Stefanie Rosumeck, Karen Ma, Stella Maria O'Brien, Nikolaos Sideris, Anna Resolver, Lai Ogunsola, Luma Haj Kassem, Thidar Aung, Sarah Moore, Sunu Alice Cherian, Brian Duncan, Charlotte Lake, Ana María Rojas Gómez, Lyle Croyle, Ana Beatriz Pizarro, Cathy Wellan, Chet Chaulagai, Artem Oganesyan, Mohammad Aloulou, Ana‐Marija Ljubenković, Jorge MM Teixeira, Iltimass Gouazar, Selin Bicer, Dulce Estêvão, Ya‐Ying Wang, Mateus Falco, Jehath Syed, Chloe Thomson, Ahlam Jamal Alhemedi, Paula Miguel, and Nirupa Sundaravadanan.

We would like to acknowledge and thank Dr John C Sinclair for his mentorship and guidance with the initial systematic review (Premji 2004).

Appendices

Appendix 1. 2020 Search methods

The RCT filters have been created using Cochrane's highly sensitive search strategies for identifying randomised trials (Higgins 2020). The neonatal filters were created and tested by the Cochrane Neonatal Information Specialist; please see the Search Methodology section at https://neonatal.cochrane.org/resources-authors/author-resources-new-reviews.

CENTRAL via CRS Web:

Date ranges: 01 January 2011 to 17 July 2020 Terms: 1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Enteral Nutrition EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET 2 (((bolus or continuous* or intermittent* or enteral* or early or nasogastric*) and (feed* or fed or tube‐feed* or tube‐fed or nutrition)) or feeding method* or feeding strateg*) AND CENTRAL:TARGET 3 #2 OR #1 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Infant, Newborn EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET 5 infant or infants or infant's or "infant s" or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birthweight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW or ELBW or NICU AND CENTRAL:TARGET 6 #5 OR #4 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 7 #6 AND #3 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 8 2011 TO 2020:YR AND CENTRAL:TARGET 9 #8 AND #7 AND CENTRAL:TARGET

MEDLINE via Ovid:

Date ranges: 01 January 2011 to 17 July 2020 Terms: 1. exp Enteral Nutrition/ 2. (((bolus or continuous* or intermittent* or enteral* or early or nasogastric*) and (feed* or fed or tube‐feed* or tube‐fed or nutrition)) or feeding method* or feeding strateg*).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. exp infant, newborn/ 5. (newborn* or new born or new borns or newly born or baby* or babies or premature or prematurity or preterm or pre term or low birthweight or low birthweight or VLBW or LBW or infant or infants or 'infant s' or infant's or infantile or infancy or neonat*).ti,ab. 6. 4 or 5 7. randomized controlled trial.pt. 8. controlled clinical trial.pt. 9. randomized.ab. 10. placebo.ab. 11. drug therapy.fs. 12. randomly.ab. 13. trial.ab. 14. groups.ab. 15. or/7‐14 16. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 17. 15 not 16 18. 6 and 17 19. randomi?ed.ti,ab. 20. randomly.ti,ab. 21. trial.ti,ab. 22. groups.ti,ab. 23. ((single or doubl* or tripl* or treb*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab. 24. placebo*.ti,ab. 25. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 26. 5 and 25 27. limit 26 to yr="2018 ‐Current" 28. 18 or 27 29. 3 and 28 30. limit 29 to yr="2011 ‐Current"

CINAHL via EBSCOhost:

Date ranges: 01 January 2011 to 17 July 2020 Terms: (((bolus or continuous* or intermittent* or enteral* or early or nasogastric*) and (feed* or fed or tube‐feed* or tube‐fed or nutrition)) or feeding method* or feeding strateg*) AND (infant or infants or infant’s or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birthweight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW) AND (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR randomised OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial) Limiters ‐ Published Date: 20110101‐20201231

ISRCTN:

Date ranges: 01 January 2011 to 17 July 2020 Terms: "Continuous nasogastric" AND feeding within Participant age range: Neonate "intermittent bolus" AND feeding within Participant age range: Neonate

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR):

Date ranges: 1 February 2020 to 17 July 2020 Terms: "Continuous nasogastric" AND feeding "intermittent bolus" AND feeding

EU Clinical Trials Register (EU‐CTR):

Date ranges: 1 February 2020 to 17 July 2020 Terms: "Continuous nasogastric" AND feeding "intermittent bolus" AND feeding

Clinical Trial Registry – India (CTRI):

Date ranges: 1 February 2020 to 17 July 2020 Terms: "Continuous nasogastric" AND feeding "intermittent bolus" AND feeding

Appendix 2. Previous search methods

Computerised searches were conducted by both review authors up to July 2011. The databases that were searched included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2011), MEDLINE back to 1966, CINAHL back to 1982 and HealthSTAR back to 1975. The following MeSH headings were used to conduct the searches: continuous, intermittent, enteral nutrition, enteral feeding, feeding, enteral nursing, enteroinsular axis, infant‐premature‐metabolism, feeding methods, gastric residuals, feeding intolerance. The searches were limited with terms such as infant‐newborn and infant, very low birthweight.

We also searched: www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.controlled‐trials.com; terms: (infant OR newborn) AND (continuous OR intermittent) AND (nutrition OR feeding OR nursing OR enteroinsular OR metabolism OR gastric).

All potentially relevant titles and abstracts identified in the searches by either review author were retrieved. The reference list of each article was reviewed independently for additional relevant titles and abstracts and these were also retrieved.

Appendix 3. ‘Risk of bias’ tool

Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

For each included study, we categorised the method used to generate the allocation sequence as:

low risk (any truly random process e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk (any non‐random process e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). Was allocation adequately concealed?

For each included study, we categorised the method used to conceal the allocation sequence as:

low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

For each included study, we categorised the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or class of outcomes. We categorised the methods as:

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for participants; and

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented at the time of outcome assessment?

For each included study, we categorised the methods used to blind outcome assessment. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or class of outcomes. We categorised the methods as:

low risk for outcome assessors;

high risk for outcome assessors; or

unclear risk for outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

For each included study and for each outcome, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses. We categorised the methods as:

low risk (< 20% missing data);

high risk (≥ 20% missing data); or

unclear risk.

Selective reporting bias. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. For studies in which study protocols were published in advance, we compared prespecified outcomes versus outcomes eventually reported in the published results. If the study protocol was not published in advance, we contacted study authors to gain access to the study protocol. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (where it is clear that all of the study's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk (where not all the study's prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified outcomes of interest and are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk.

Other sources of bias. Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias (for example, whether there was a potential source of bias related to the specific study design or whether the trial was stopped early due to some data‐dependent process). We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as:

low risk;

high risk; or

unclear risk.

If needed, we explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Continuous versus intermittent bolus milk feeding.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Age at full enteral feedings (days) | 7 | 628 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [‐0.13, 1.81] |

| 1.2 Age at full enteral feedings (days) (median, IQR) | 2 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.3 Age at full enteral feedings (days): sensitivity analysis removing trials with mix of nasogastric and orogastric | 5 | 336 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [‐0.60, 1.42] |

| 1.4 Age at full enteral feedings (days): subgroup analysis | 7 | 610 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [‐0.13, 1.74] |

| 1.4.1 Birth weight < 1000 grams | 4 | 216 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [‐0.69, 1.54] |

| 1.4.2 Birth weight ≥ 1000 grams and < 1249 grams | 2 | 71 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐2.54, 2.21] |

| 1.4.3 Birth weight ≥ 1250 grams and < 1500 grams | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.00 [‐0.48, 10.48] |

| 1.4.4 Data not stratified by birth weight category | 3 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.30 [0.58, 6.01] |

| 1.5 Feeding intolerance: number of days of feeding interruptions | 1 | 171 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.00 [‐9.50, 3.50] |

| 1.6 Days to regain birth weight | 6 | 610 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.38 [‐1.16, 0.41] |

| 1.7 Days to regain birthweight: sensitivity analysis removing trials with mix of nasogastric and orogastric | 5 | 489 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐1.27, 0.43] |

| 1.8 Days to regain birth weight: subgroup analysis | 6 | 592 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.34 [‐1.14, 0.46] |

| 1.8.1 Birth weight < 1000 grams | 3 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐2.11, 1.84] |

| 1.8.2 Birth weight ≥ 1000 grams and < 1249 grams | 2 | 71 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐2.45, 1.66] |

| 1.8.3 Birth weight ≥ 1250 grams and < 1500 grams | 1 | 32 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐3.53, 3.53] |

| 1.8.4 Data not stratified by birth weight category | 3 | 369 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐1.40, 0.60] |

| 1.9 End of intervention: rate of gain in weight | 5 | 433 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.27, 0.46] |

| 1.9.1 Birth weight < 1000 grams | 1 | 30 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.20, 1.75] |