Abstract

In the transition to a clean-energy future, CO2 separations will play a critical role in mitigating current greenhouse gas emissions and facilitating conversion to cleaner-burning and renewable fuels. New materials with high selectivities for CO2 adsorption, large CO2 removal capacities, and low regeneration energies are needed to achieve these separations efficiently at scale. Here, we present a detailed investigation of nine diamine-appended variants of the metal–organic framework Mg2(dobpdc) (dobpdc4− = 4,4′-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3′-dicarboxylate) that feature step-shaped CO2 adsorption isotherms resulting from cooperative and reversible insertion of CO2 into metal–amine bonds to form ammonium carbamate chains. Small modifications to the diamine structure are found to shift the threshold pressure for cooperative CO2 adsorption by over four orders of magnitude at a given temperature, and the observed trends are rationalized based on crystal structures of the isostructural zinc frameworks obtained from in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments. The structure–activity relationships derived from these results can be leveraged to tailor adsorbents to the conditions of a given CO2 separation process. The unparalleled versatility of these materials, coupled with their high CO2 capacities and low projected energy costs, highlights their potential as next-generation adsorbents for a wide array of CO2 separations.

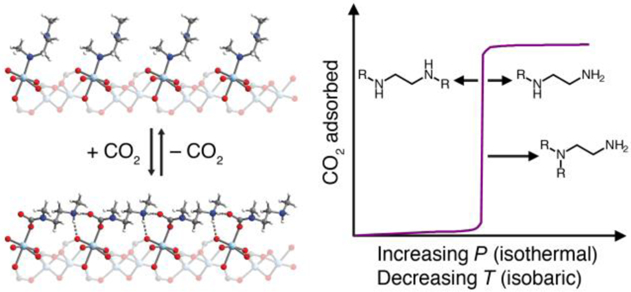

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With the atmospheric CO2 concentration now exceeding 400 ppm,1 rapid implementation of carbon management strategies will be essential to limit further rise in the average global temperature. The energy sector alone accounts for 68% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, including more than 32 Gt of CO2 per year.2 While decarbonization of the energy sector will ultimately require long-term restructuring of current energy systems, emission mitigation strategies are needed in the near-term to minimize the environmental impact of the existing energy infrastructure.3 Carbon capture and sequestration, in which CO2 is selectively removed from point sources such as the flue gas of power plants, has been proposed as a particularly promising emission mitigation strategy.4 As a complementary approach, separating CO2 from crude gas reserves can favor greater production and use of natural gas, which is nearly half as emission intensive as coal on a tons of carbon per terajoule basis.5 In a third strategy, removal of CO2 from crude biogas could enable greater adoption of biomethane as a renewable fuel.6 Each of these strategies requires materials capable of efficiently capturing CO2 from a variety of gas mixtures over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. As a result, a tunable CO2 capture material would be highly desirable to maximize the energy efficiency of each individual process through a coupled optimization of adsorbent design and process engineering.

Aqueous amine absorbers, dating to the 1930s, remain the most mature technology available for large-scale CO2 separations.7 Despite their advanced state of development, these solutions suffer from inherent limitations arising from thermal and oxidative amine degradation as well as corrosion issues, which necessitate the use of dilute amine solutions that possess low working capacities for CO2.8 Furthermore, while thermal integration and the development of new amines enable a moderate degree of flexibility in targeting specific CO2 separations, future advances are anticipated to afford only incremental savings in the regeneration energy of absorption-based processes.9

Recently, solid adsorbents with large working capacities and inherently lower regeneration energy requirements have shown promise in significantly reducing the energetic and economic costs of CO2 separations.10,11 In particular, amine-functionalized adsorbents, as with aqueous amine solutions, leverage Lewis acid–base chemistry between CO2 and amines to form ammonium carbamate or bicarbonate species. These reactions enable highly selective binding of CO2 from gas mixtures even in the presence of water, which typically passivates adsorbents relying on exposed metal ions as binding sites.12

Metal–organic frameworks, a class of crystalline, porous materials consisting of metal ions or clusters bridged by organic ligands, offer the potential to incorporate the desirable properties of amine-based CO2 capture in highly modular systems with well-defined binding sites.13–17 Specifically, the grafting of alkyldiamines onto frameworks bearing coordinatively-unsaturated metal centers has been demonstrated as an effective approach to realize strong and selective binding of CO2.18–29 This strategy led to the recent discovery of an exceptional set of diamine-appended adsorbents, mmen–M2(dobpdc) (mmen = N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine; M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Zn; dobpdc4– = 4,4′-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3′-dicarboxylate) (Figure 1a), that exhibit step-shaped CO2 adsorption isotherms.21,23 Unlike conventional Langmuir-type adsorption, significant CO2 adsorption in mmen–M2(dobpdc) occurs only above a critical partial pressure that dramatically increases with temperature. This switch-like adsorption behavior enables separations in which the full CO2 capacity of the material can be accessed using a minimal temperature swing for each adsorption/desorption cycle.

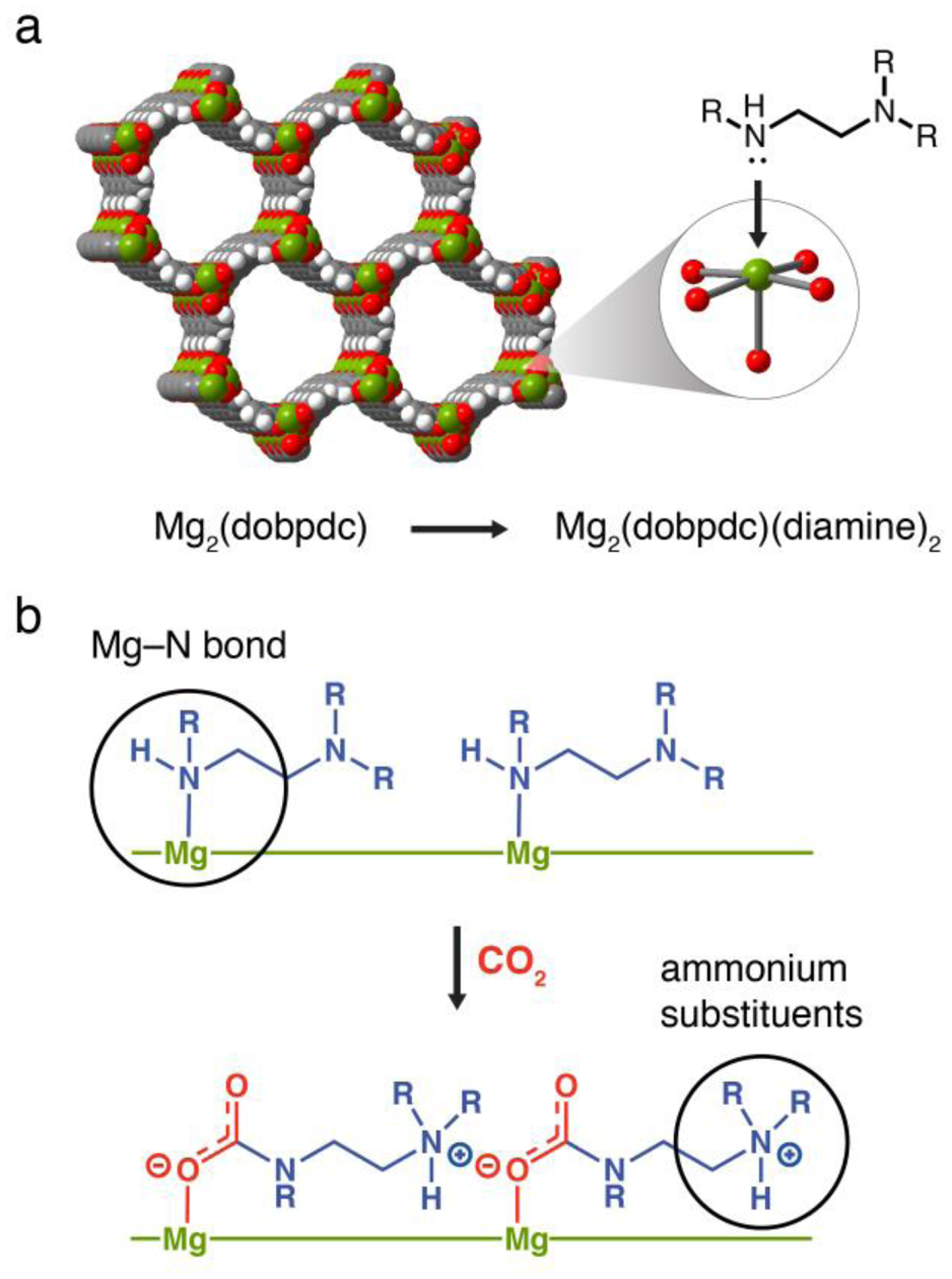

Figure 1.

(a) Representative structure of the metal–organic framework Mg2(dobpdc). Green, red, gray, and white spheres represent Mg, O, C, and H atoms, respectively. The inset shows a single open MgII site appended with a diamine molecule. (b) Depiction of cooperative CO2 insertion into a row of MgII–diamine sites to form ammonium carbamate chains along the pore axis. The threshold conditions for cooperative adsorption can be tuned by modifying the diamine structure to adjust the strength of the metal–amine bond and the ammonium carbamate ion-pairing interaction.

Remarkably, CO2 binds in these materials through cooperative insertion into the metal–amine bonds to form ammonium carbamate chains.23,30 As a result, the adsorption step pressure can be tuned by altering the metal–amine bond strength. Specifically, varying the framework metal(II) cations led to a shift in step pressure following the order Mg < Mn < Fe < Zn < Co,23 consistent with the anticipated metal–ligand bond strengths for divalent, octahedral metal complexes.31 However, this approach to developing tunable CO2 adsorbents is limited by the range of metals with which the framework can be synthesized. In addition, at industrial scale, the flexibility of this strategy is further restricted to metals for which precursor salts can be sourced economically.

As an alternative strategy, the appended diamine can be varied to change the position of the CO2 adsorption step.22,24,28,29 We envisioned that this approach would provide a straightforward and versatile route to a broader library of adsorbents tailored to specific CO2 capture applications. This method further enables the adsorption step pressure to be tuned for a specific metal variant of M2(dobpdc). To maximize the ultimate industrial viability of the adsorbents, we focused our efforts on the base framework Mg2(dobpdc) due to the low cost of MgII precursor salts, the stability and scalability of the material, and the high gravimetric capacities achievable with the resulting diamine-appended adsorbents.

Recognizing that the cooperative adsorption threshold is dictated by the relative stability of the amine-bound and CO2-inserted phases, we sought to probe the influence of the diamine structure on the strength of both the metal–amine bond and the ammonium carbamate ion-pairing interaction (Figure 1b). Here, we present the evaluation of nine diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks using thermogravimetric analysis and a custom-made, high-throughput, volumetric gas adsorption instrument.12 Structural insight from in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments with the isostructural zinc frameworks further revealed precise correlations between diamine structure and the cooperative CO2 adsorption properties of these materials. Altogether, these studies outline the critical principles for the design of diamine-appended metal–organic frameworks with adsorption properties optimized for specific CO2 separations.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Synthesis and Characterization Methods.

The compound 4,4′-dihydroxy-(1,1′-biphenyl)-3,3′-dicarboxylic acid (H4dobpdc) was either obtained from Combi-Blocks and purified by recrystallization from a 3:1 (v:v) acetone:water mixture or was synthesized as previously reported.32 All other reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers at reagent grade purity or higher and were used without further purification. Ultra-high purity (99.999%) He and N2 and research grade (99.998%) CO2 were used for all adsorption experiments. Elemental analyses were conducted at the Microanalytical Laboratory of the University of California, Berkeley, using a PerkinElmer 2400 Series II combustion analyzer.

Synthesis of Mg2(dobpdc).

The framework Mg2(dobpdc) was synthesized by a solvothermal method scaled from a previous report.23 The ligand H4dobpdc (9.89 g, 36.1 mmol) and Mg(NO3)2∙6H2O (11.5 g, 44.9 mmol) were dissolved in 200 mL of a 55:45 (v:v) methanol:N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) mixture using sonication. The solution was filtered to remove any undissolved particulates and added to a 350 mL glass pressure vessel with a glass stirbar. The reactor was sealed with a Teflon cap and heated in a silicone oil bath at 120 °C for 20 h. The crude white powder was isolated by filtration and soaked 3 times in 200 mL of DMF for a minimum of 3 h at 60 °C, followed by solvent exchange by soaking 3 times in 200 mL of methanol for a minimum of 3 h at 60 °C. The methanol-solvated framework was collected by filtration and heated in vacuo or under flowing N2 for 12 h at 250 °C to yield fully desolvated Mg2(dobpdc) as a white powder. Combustion elemental analysis calculated for C14H6O6Mg2: C, 52.74; H, 1.90. Found: C, 53.00; H, 1.56. Representative Langmuir surface areas, powder X-ray diffraction patterns, and infrared spectra are presented in Figures S1–S2 and S5.

Synthesis of Diamine-Appended Mg2(dobpdc) Frameworks.

Samples of diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks used for collection of high-throughput isotherm data were prepared following conditions reported previously.23 For each analogue, a solution of 20 v/v% diamine in toluene was stirred over freshly-ground CaH2, and a quantity corresponding to a 10-fold molar excess of diamine per metal site was added to approximately 100 mg of desolvated Mg2(dobpdc) under N2 by syringe or cannula transfer. The slurry was sonicated for 15 min under N2 and left undisturbed under N2 for a minimum of 12 h. The solid was then isolated by filtration in air and washed with 30 mL of dry toluene followed by 30 mL of dry hexanes at room temperature. Prior to adsorption measurements, the samples were desolvated by heating in vacuo at 120 °C for 12 h.

For all subsequent experiments, it was found that identical CO2 adsorption performance could be achieved through direct diamine-grafting of methanol-solvated Mg2(dobpdc), enabling rapid sample preparation by eliminating time-consuming activation of the parent framework. In this rapid procedure, approximately 30 mg of methanol-solvated Mg2(dobpdc) was isolated by filtration, washed with 30 mL of toluene, and submerged in 5 mL of a 20 v/v% solution of diamine in toluene. After 12 h, the solid was isolated by filtration and washed with 30 mL of fresh toluene to remove excess diamine.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns, infrared spectra, and representative diamine loadings obtained from NMR spectra upon digestion of the material are presented in Figures S3–S4 and Table S2.

Synthesis of Zn2(dobpdc) Single Crystals.

In a 20 mL vial, H4dobpdc (23 mg, 0.084 mmol) was dissolved in 2.8 mL of dimethylacetamide (DMA). In a second 20 mL vial, Zn(NO3)2∙6H2O (62 mg, 0.21 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of 2.8 mL of ethanol and 2.8 mL of water. Several thick-walled borosilicate tubes were each charged with 0.2 mL of ligand stock solution and 0.4 mL of Zn stock solution. The resulting reaction solutions (10 mM H4dobpdc, 2.5 equivalents Zn(NO3)2∙6H2O, 0.6 mL of 1:1:1 (v:v:v) DMA:ethanol:water) were degassed by four freeze–pump–thaw cycles, after which the tubes were flame-sealed and placed in an oven pre-heated to 100 °C. After 48 h, pale yellow, needle-shaped crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction had formed. The crystals were transferred from the reaction solution to a 10 mL Schlenk flask, sealed under N2, and soaked 3 times in 10 mL of dry DMA for a minimum of 3 h, followed by 3 times in 10 mL of dry methanol for a minimum of 3 h at room temperature. The solution was replaced 3 times with 10 mL of dry toluene, and the toluene-suspended crystals were degassed by four freeze–pump–thaw cycles. The crystals were then transferred to an N2-filled glovebox and stored under dry toluene until use.

Synthesis of Diamine-Appended Zn2(dobpdc) Single Crystals.

Samples of Zn2(dobpdc) crystals were removed from the glovebox under 2 mL of toluene in individual 4 mL vials. For each analogue, 12 μL of the desired diamine was added to the vial, which was then left undisturbed for 4 h. Excess diamine was removed by decanting and washing 3 times with fresh toluene. For crystals appended with 1°/2° diamines, the crystals were transferred to plastic centrifuge tubes prior to addition of diamine to avoid adhesion of the crystals to the borosilicate glass. The toluene-solvated crystals were analyzed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction within 24 h of preparation.

Gas Dosing of Diamine-Appended Zn2(dobpdc) Single Crystals.

For CO2-inserted structures of Zn2(dobpdc) appended with N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine (m-2-m), N,N′-diethylethylenediamine (e-2-e), and N-isopropylethylenediamine (i-2), diamine-appended crystals were first soaked in hexanes or diethyl ether to facilitate removal of residual toluene from the pores. A single crystal was then mounted on a MiTeGen loop using a minimal amount of epoxy, taking care to avoid the ends of the rod-shaped crystals to preserve access to the hexagonal pores for gas diffusion. The sample was then transferred to a custom-made gas cell consisting of a quartz capillary with a vacuum-tight O-ring seal and Beswick ball valves for gas dosing.33 Within the cell, the crystal was desolvated under reduced pressure for 45 min at an external temperature of 50 °C using an Oxford Cryosystems cryostream and a turbomolecular pump. After solving the structure to confirm removal of residual solvent from the pores, the crystal was cooled to 25 °C, dosed with 1 bar of CO2, and rapidly cooled to 195 K for the final data collection.

To obtain CO2-inserted X-ray single-crystal structures of Zn2(dobpdc) appended with N-methylethylenediamine (m-2) and N-ethylethylenediamine (e-2), single crystals were first washed with dry hexanes, transferred to a glass measurement tube sealed with a Micromeritics TranSeal, and heated in vacuo at 100 °C (m-2) or 50 °C (e-2) for 1 h on an ASAP 2420 gas adsorption instrument. The sample was then transferred air-free to the analysis port of the instrument and dosed with 1.1 bar of CO2. The tube was sealed under CO2, removed from the manifold, and stored over dry ice for 3 h. The crystals were coated with Paratone oil immediately after the tube was opened, and a single crystal was rapidly mounted and flash-cooled to 100 K using an Oxford Cryosystems cryostream prior to data collection.

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction.

All single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected at Beamline 11.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory using synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.7749, 0.7293, or 0.8856 Å; see Table S4) and a Bruker AXS D8 diffractometer equipped with a Bruker PHOTON 100 CMOS detector. Single-crystal structures of diamine-appended Zn2(dobpdc) frameworks without CO2 were collected at 100 K using an Oxford Cryosystems Cryostream 700 Plus. Structures with CO2 were collected at either 195 K (Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2-m–CO2)1.5, Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e)(e-2-e–CO2), and Zn2(dobpdc)(i-2)(i-2–CO2)) or 100 K (Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2–CO2)1.62 and Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2–CO2)1.5). All crystals were refined in space group P3221 or P3121 as inversion twins based on Flack parameter values near 0.5. Raw data were corrected for Lorenz and polarization effects using Bruker AXS SAINT software34 and were corrected for absorption using SADABS.35 The structures were solved using SHELXT36 and refined using SHELXL37 operated in the OLEX238 interface. Thermal parameters were refined anisotropically for all non-hydrogen atoms. All hydrogen atoms were placed geometrically and refined using a riding model.

For structures without CO2, the appended diamines were found to be disordered over a minimum of two positions. The reported formula and final refinement were fixed to reflect the freely refined occupancy of each diamine. However, the occupancy of the bound nitrogen was fixed at 1 to account for solvent or water bound on sites where the diamine was absent. Similarly, for CO2-inserted structures, the occupancy of the bound oxygen of the carbamate was fixed at 1 to account for CO2, solvent, or water where the ammonium carbamate chains were absent, but the reported formula reflects the oxygen content for the freely refined ammonium carbamate chains alone. Displacement parameter restraints (RIGU and SIMU) and distance restraints (SADI, and in select cases DFIX) were necessary to model disorder of the free diamines and the ammonium carbamate chains.

Thermogravimetric Analysis.

Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were conducted using a TA Instruments TGA Q5000 with a flow rate of 25 mL/min for all gases. Masses were uncorrected for buoyancy effects. For isobars under 100% CO2, samples were first activated under flowing N2 at 120–150 °C for 30 min, after which the temperature was rapidly increased to the highest plotted temperature for each adsorption (cooling) isobar. The gas was then switched to 100% CO2 and the mass normalized to 0. Cooling and heating rates of 1 °C/min were used for isobars unless otherwise specified. For N,N-diisopropylethylenediamine (ii-2)-appended Mg2(dobpdc), the sample was held isothermally for 45 min at 30 °C prior to switching from adsorption to desorption. Adsorption isobar step temperatures were determined as the inflection points of the isobars based on the peak of the temperature derivative. Desorption isobar step temperatures were determined as the point of closure of the hysteresis loop (Table S3).

Thermogravimetric decomposition traces were collected under 100% N2 with a temperature ramp rate of 1.5 °C/min (Figures S7 and S9). Comparison of derivative plots (dTG, mg/min vs. temperature) was performed using data collected from diamine-appended samples prepared from the same batch of Mg2(dobpdc) (Figure S8).

High-Throughput Gas Adsorption Isotherm Measurements.

Adsorption isotherms for CO2, N2, and H2O were collected in parallel for all diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) analogues at 25, 40, 50, 75, 100, and 120 °C using a custom-built, 28-channel volumetric gas adsorption instrument designed by Wildcat Discovery Technologies. Calibration and verification of this instrument have been described in detail in a previous report.12 Samples were heated in vacuo for 12 h at 120 °C prior to collection of each isotherm. Additional experimental details, as well as N2 and H2O isotherms, can be found in the Supporting Information (Figures S13–S14).

Calculation of Differential Enthalpies and Entropies of Adsorption.

The differential enthalpy (Δhads) of cooperative CO2 adsorption for each diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) framework was calculated from the high-throughput adsorption isotherms using the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship (Eq. 1).39

| (1) |

Here, P is the pressure, T is the temperature, R is the universal gas constant, and C is a constant equal to −Δsads/R, where Δsads is the differential entropy of adsorption.39 Lines of constant loading at n = 1 mmol/g (within the cooperative adsorption region) were obtained using linear interpolation for a minimum of three adsorption isotherms over a range of 25 to 120 °C. (Note that previous studies21,23 have shown Δhads to be relatively constant throughout the cooperative adsorption region.) From the plots of ln P vs. 1/T, Δhads and Δsads were obtained from the slope and y-intercept, respectively. Standard errors were calculated from the deviations of the best-fit lines of constant loading. For ii-2–Mg2(dobpdc), only two isotherms could be used due to the step pressure exceeding the accessible pressure range at higher temperatures, and thus a comparable standard error could not be obtained in this case. Further details are provided in Table S3.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selection of Diamines and Synthesis of Adsorbents.

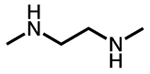

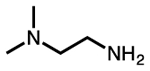

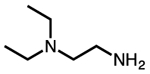

In this study, nine carefully chosen diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks were synthesized and analyzed to determine the correlation between the diamine structure and the thermodynamic threshold for cooperative CO2 adsorption. Based on the metal dependence of the adsorption properties in the mmen–M2(dobpdc) series, we hypothesized that for a given metal, increasing the metal–amine bond strength would increase the isothermal step pressure for cooperative CO2 adsorption (or, equivalently, decrease the isobaric step temperature) by stabilizing the amine-bound phase relative to the CO2-inserted phase. We further postulated that the same effect could be achieved by increasing the steric profile of the unbound amine to decrease the stability of the ammonium carbamate chains. Both of these effects were probed by preparing adsorbents bearing 2°/2°, 1°/2°, and 1°/3° diamines with substituents of varying size. To simplify the nomenclature of this class of adsorbents, a diamine naming scheme was devised following the pattern RR–n–R, where each R signifies methyl (m), ethyl (e), or isopropyl (i) substituents on each amine, and n indicates the number of carbons on the alkyl bridge connecting the amines (Table 1). Note that in order to adsorb CO2 by cooperative insertion, the diamine must possess at least one proton to form a charge-balancing ammonium cation.

Table 1.

Diamine Structures and Nomenclature System

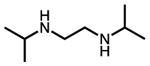

| Diamine name | Structure | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine |  |

m-2-m (mmen) |

| N,N′-diethylethylenediamine |  |

e-2-e |

| N,N′-diisopropylethylenediamine |  |

i-2-i |

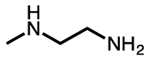

| N-methylethylenediamine |  |

m-2 |

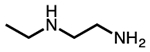

| N-ethylethylenediamine |  |

e-2 |

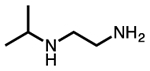

| N-isopropylethylenediamine |  |

i-2 |

| N,N-dimethylethylenediamine |  |

mm-2 |

| N,N-diethylethylenediamine |  |

ee-2 |

| N,N-diisopropylethylenediamine |  |

ii-2 |

The framework Mg2(dobpdc), an expanded variant of the well-studied framework Mg2(dobdc)40 and an isomer of the isoreticular framework IRMOF-74-II,41 was readily synthesized on a multi-gram scale by modification of the previously reported23 solvothermal reaction of H4dobpdc with Mg(NO3)2∙6H2O in 55:45 MeOH:DMF at 120 °C. After washing the as-synthesized framework with DMF and exchanging the bound solvent with methanol, diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) analogues were rapidly prepared by submerging aliquots of the framework in 20 v/v% solutions of diamine in toluene. While previous reports of diamine-appended M2(dobpdc) frameworks stipulated removal of bound solvent molecules by heating in vacuo at 250 °C prior to diamine grafting,21–24,28 we determined that functionalization with diamines could be achieved directly with methanol-solvated Mg2(dobpdc). In this activation-free procedure, a greater excess of diamine (~50 equivalents per MgII site) is typically required, as compared to ~10 equivalents in the procedure involving activation. However, the synthetic ease of the activation-free procedure enables analysis of a wide array of diamine-appended analogues within a short time period. Furthermore, for large-scale preparations, the excess diamine solution can easily be recycled, and the activation-free procedure eliminates the need for hazardous diamine drying agents, such as CaH2, employed in previous reports.

For all diamine-appended frameworks, completeness of diamine grafting was confirmed by examining the CO2 saturation loading (discussed below), the 1H NMR spectra of samples digested in DCl/DMSO-d6 (Table S2), and the thermogravimetric decomposition curves (Figure S7). Attempts to synthesize the tetramethylethylenediamine-appended framework mm-2-mm–Mg2(dobpdc) revealed that diamine loadings higher than 15% could not be achieved, even with addition of a large excess of diamine to the activated framework.

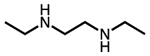

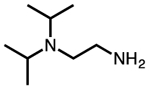

Structural Characterization of Diamine Binding in M2(dobpdc)(diamine)2.

To understand the influence of the diamine on the stability of the amine-bound phase, we sought to characterize the structure of the diamine-appended frameworks prior to CO2 adsorption by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. While we were unable to prepare suitable single crystals of the Mg2(dobpdc) analogues, we developed a new synthetic route to grow millimeter-sized single crystals of the isostructural Zn framework. These crystals were washed and grafted with diamines following a procedure similar to that implemented for Mg2(dobpdc), enabling the characterization of the resulting diamine-appended crystals by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structures of Zn2(dobpdc) and toluene-solvated, diamine-appended variants, as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction at 100 K. Left: A portion of the crystal structure of Zn2(dobpdc)(DMA)2 as viewed along the c axis (N,N-dimethylacetamide molecules have been excluded for clarity). Right: First coordination spheres for the ZnII centers in a series of diamine-appended frameworks examined in this work. Structures were refined as inversion twins in either space group P3121 or P3221, and the diamines were found to be disordered over a minimum of two positions. For clarity, only the dominant conformation is depicted in space group P3221. Light blue, blue, red, gray, and white spheres represent Zn, N, O, C, and H atoms, respectively.

In all cases, disorder of the appended diamine over a minimum of two positions was observed, indicating that the diamines have conformational degrees of freedom within the pores prior to CO2 insertion. With the exception of m-2, all 1°/2° and 1°/3° diamines were found to bind exclusively through the primary amine in the 100 K structures. Although the disorder in m-2–Zn2(dobpdc) could not be modeled satisfactorily, preliminary refinements suggested the presence of a mixture of primary amine-bound and secondary amine-bound structures.

Diamines bound through a primary amine were found to exhibit Zn–N bond lengths 0.03(1) Å shorter on average than those of diamines bound through a secondary amine, consistent with primary amine-bound diamines possessing greater metal–amine bond strengths. This trend likely results from the decrease in steric repulsion between the framework and coordinated primary amines compared to secondary amines. Within a class of diamines (2°/2°, 1°/2°, or 1°/3°), small differences in Zn–N bond lengths were within the estimated standard deviations.

The influence of M–N bond strength was further investigated through analysis of the thermogravimetric decomposition traces of Mg2(dobpdc)(diamine)2 frameworks (Figure S8). For each analogue, the temperature of the maximum rate of diamine volatilization was identified by plotting the derivative of mass loss (dTG, mg/min) with respect to temperature. This Tmax was then plotted as a function of diamine boiling point for all alkylethylenediamine–Mg2(dobpdc) analogues. For 1°/2° and 1°/3° analogues, Tmax of diamine volatilization increases linearly from the methyl to ethyl to isopropyl variants. This increased Tmax for larger substituents likely arises from the increasing diamine molecular weight and greater van der Waals contacts with the framework. In contrast, for the 2°/2° analogues, Tmax of diamine volatilization decreases with increasing diamine boiling point, moving from m-2-m to e-2-e to i-2-i. This finding is consistent with a reduction in metal–amine bond strength upon increasing the substituent size on the metal-bound amine.

Isobaric Characterization of CO2 Adsorption.

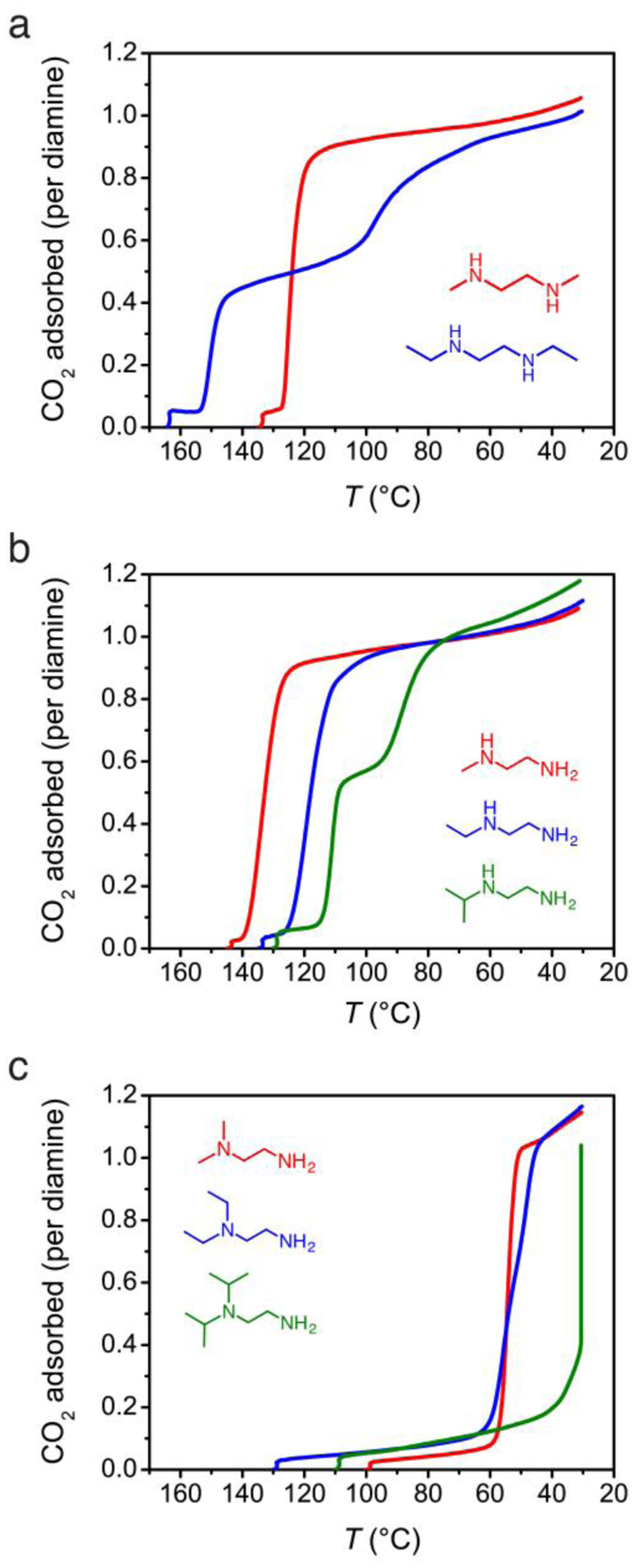

Thermogravimetric adsorption isobars enable rapid comparison of cooperative adsorption step temperatures for a variety of diamine structures. The adsorption isobars of the Mg2(dobpdc)(diamine)2 series under pure CO2 at ambient pressure reveal that altering the steric profile of each amine causes dramatic changes in the isobaric threshold temperature for cooperative adsorption (Figure 3). In all cases, the frameworks were found to possess sharp, step-shaped adsorption isobars with saturation values consistent with a loading of 1 CO2 per diamine–MgII site. For 2°/2° diamines (Figure 3a), moving from m-2-m to e-2-e increases the step temperature from 125 °C to 151 °C. The higher cooperative adsorption temperature for the diethyl variant is consistent with a reduced metal–amine bond strength upon functionalization of the bound amine with larger alkyl substituents. By destabilizing the amine-bound phase, the transition to CO2-inserted, O-bound carbamates becomes favorable at a higher temperature with e-2-e compared to m-2-m. Notably, a second step in the e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc) isobar was observed at approximately half occupancy. This second step is the subject of ongoing investigation in our laboratory and can likely be attributed to formation of a secondary conformation or rearrangement of the ammonium carbamate chains at half occupancy.

Figure 3.

Adsorption isobars under pure CO2 for (a) 2°/2°, (b) 1°/2°, and (c) 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks, demonstrating the effect of diamine structure on the cooperative adsorption step temperature.

Attempts to collect CO2 adsorption isobars or isotherms for the 2°/2° diisopropylethylenediamine-appended framework i-2-i–Mg2(dobpdc) were ultimately unsuccessful (Figure S10). While the 1H NMR spectrum of material digested with DCl in DMSO-d6 indicated up to 70% diamine loading with respect to the quantity of MgII sites in the framework (Table S2), the diamine was rapidly liberated from the framework upon activation under flowing N2 or vacuum (Figure S7). This result further supports the conclusion that increasing the substituent size on the metal-bound amine decreases the metal–amine bond strength.

For 1°/2° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks (Figure 3b), increasing the steric profile of the unbound amine decreases the threshold temperature for cooperative adsorption from 134 °C for m-2 to 120 °C for e-2 and 111 °C for i-2. As with the e-2-e-appended framework, a second adsorption step is apparent for i-2–Mg2(dobpdc). The steric trend is maintained with 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks (Figure 3c), for which the step temperature decreases to approximately 55 °C for mm-2 and ee-2 and 30 °C for ii-2. The reduction in step temperature with increasing substituent size is consistent with weaker ammonium carbamate ion pairing upon CO2 insertion with more sterically encumbered secondary and tertiary amines.

The steric influence of the diamine also accounts for differences in the CO2 adsorption isobars among 2°/2°, 1°/2°, and 1°/3° diamines bearing substituents of the same size. For example, in the series of ethyl-substituted diamines, the primary amine-bound e-2–Mg2(dobpdc) decreases the CO2 step temperature to 120 °C as compared to e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc), where the adsorption step occurs at 151 °C. This is likely due to the stronger interaction of the metal with e-2 as compared to e-2-e, which causes CO2 insertion to become thermodynamically less favorable. For ee-2–Mg2(dobpdc), the adsorption step temperature is further reduced to approximately 56 °C, consistent with the above observation of lower step temperatures for diamines with larger substituents on the ammonium-forming amine. In general, isobaric step temperatures follow the order 2°/2° > 1°/2° > 1°/3° for a given substituent class (methyl, ethyl, or isopropyl). The adsorbent m-2–Mg2(dobpdc), which shows a higher threshold temperature than m-2-m–Mg2(dobpdc), is an exception to this trend and will be discussed in subsequent sections.

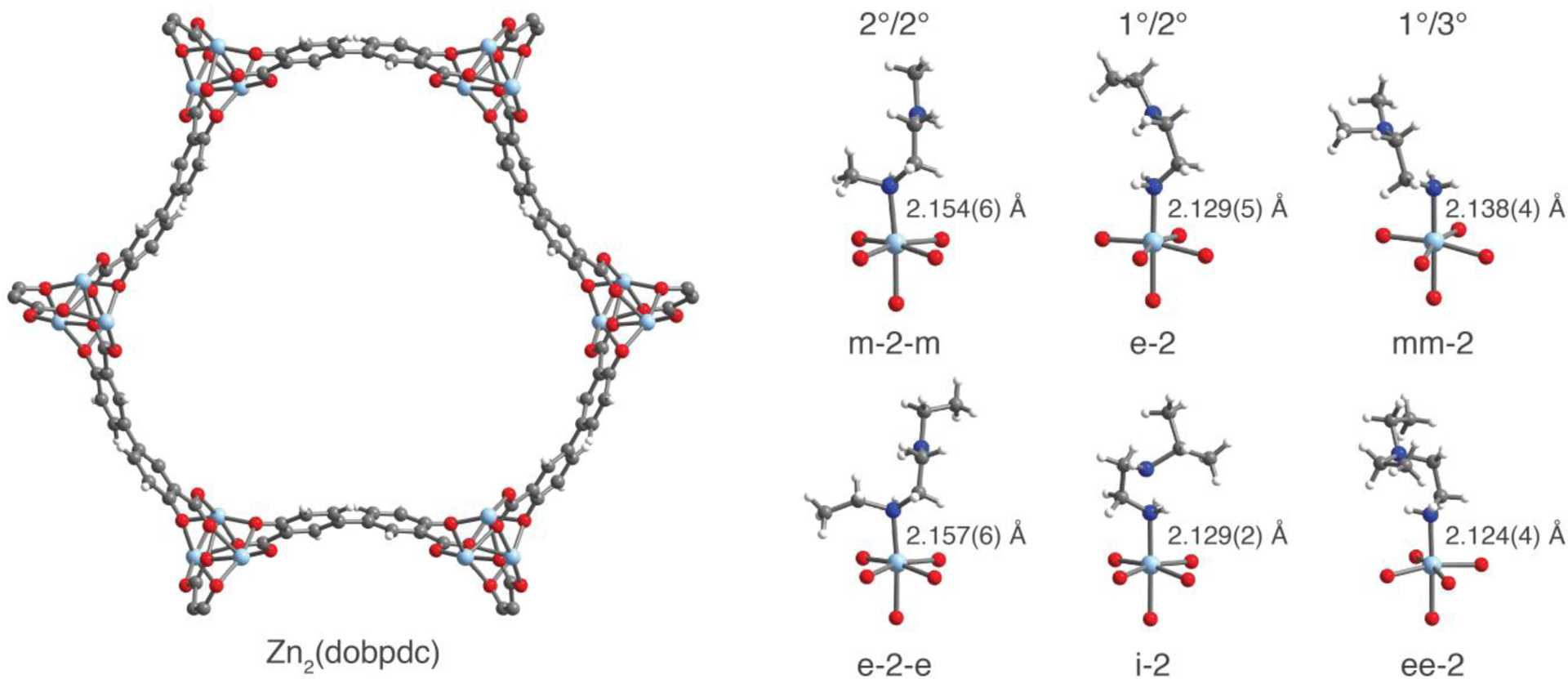

X-ray Single-Crystal Structures of CO2-Inserted Diamine-Appended Frameworks.

To better understand the influence of diamine structure on the stability of the ammonium carbamate chains, in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted using an environmental gas cell33 designed at Beamline 11.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source (Figure 4). While a number of single-crystal structures have been reported characterizing CO2 binding sites for adsorbents demonstrating Langmuir-type physisorption of CO2,33,42–45 analogous experiments are exceedingly rare for phase-change adsorbents, such as flexible metal–organic frameworks.46,47 The dramatic change in unit cell volume that accompanies adsorption-induced phase changes in these materials typically leads to difficulty in maintaining single crystallinity throughout the transition. In contrast, diamine-appended analogues of M2(dobpdc) benefit from the framework acting as a relatively rigid, crystalline scaffold during formation of ammonium carbamate chains, as well as the high degree of order induced by the CO2 insertion mechanism. These experiments afford unprecedented precision in determining the structural nuances governing the cooperative adsorption process. To the best of our knowledge, these structures, together with the previously reported structure of Mn2(dobpdc)(m-2-m–CO2)2 obtained by powder X-ray diffraction,23 represent the only crystallographically characterized examples of chemisorption of CO2 to form ammonium carbamate species in a porous material.

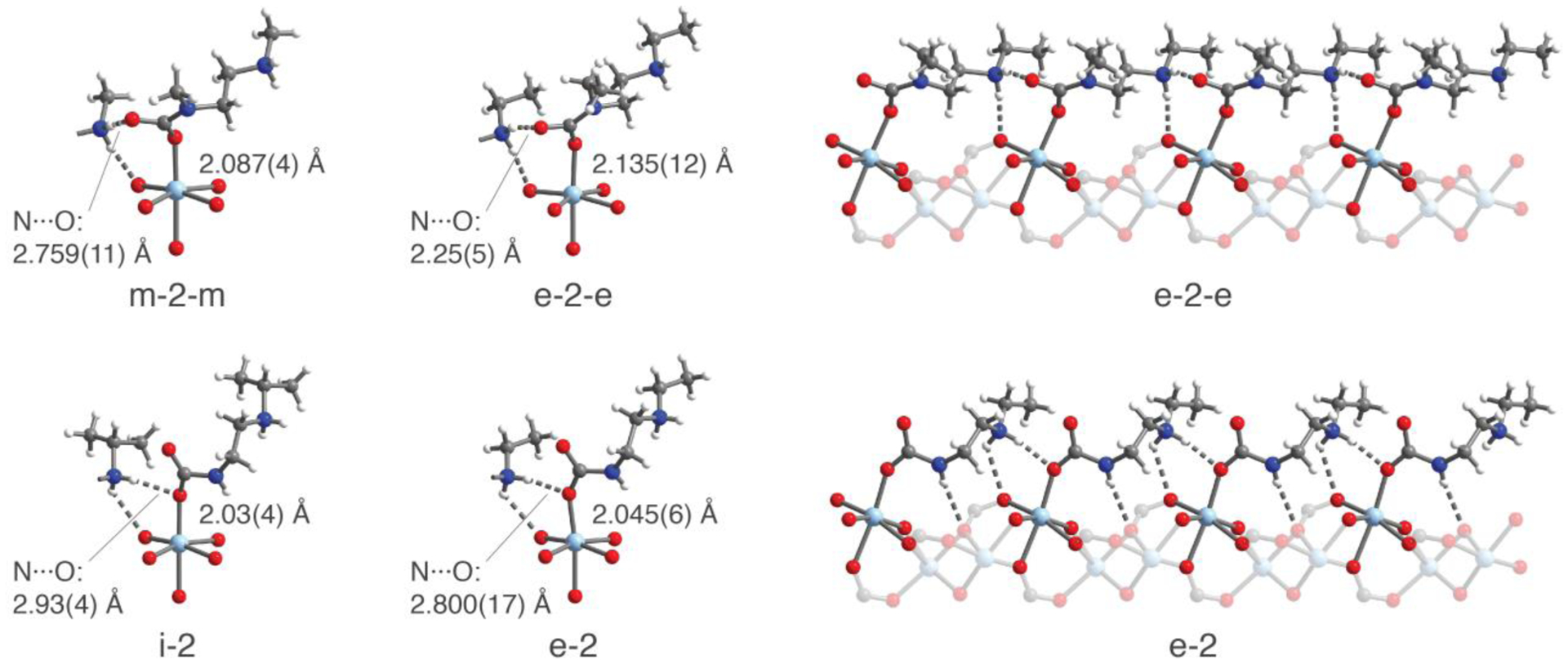

Figure 4.

Representative structures of CO2-inserted diamine-appended Zn2(dobpdc) frameworks as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Left: First coordination spheres for the ZnII centers in Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2-m–CO2)1.5, Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e)(e-2-e–CO2), and Zn2(dobpdc)(i-2)(i-2–CO2) at 195 K and the dominant conformation of Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2–CO2)1.5 at 100 K. Right: A portion of the ammonium carbamate chains along the pore axis of the material for Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e–CO2) and Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2–CO2)1.5. For clarity, all structures are depicted in space group P3221. Light blue, blue, red, gray, and white spheres represent Zn, N, O, C, and H atoms, respectively.

Single crystals of diamine-appended Zn2(dobpdc) frameworks were again used for these experiments, owing to their greater crystallinity compared to the isostructural magnesium frameworks. Importantly, isobaric adsorption measurements with diamine-appended Zn2(dobpdc) powders under pure CO2 confirm that the zinc and magnesium analogues follow the same trends in CO2 adsorption step temperature (Figure S12). Larger alkyl substituents increase the threshold temperature for Zn2(dobpdc) frameworks appended with 2°/2° diamines (55 °C for m-2-m versus >75°C for e-2-e) but decrease the threshold temperature for frameworks with 1°/2° diamines (52 °C for e-2 versus 47 °C for i-2).

The single-crystal structure of CO2-dosed m-2-m–Zn2(dobpdc) at 195 K shows full insertion of CO2 into the Zn–N bonds to produce O-bound carbamate species with Zn–O distances of 2.087(4) Å. The unbound carbamate oxygen atom interacts with an ammonium cation from a neighboring diamine, forming an ion pair with an N···O distance of 2.579(11) Å. The structure is in very good agreement with the previously published powder X-ray diffraction structure of m-2-m–Mn2(dobpdc), for which Mn–O distances of 2.10(2) Å and N···O distances of 2.61(10) Å were observed.23 Similar Zn–O distances of 1.919(3)–1.995(4) Å have also been reported for molecular zinc(II) carbamate complexes,48–51 and the N···O distances observed here are consistent with those of purely organic ammonium carbamate networks formed from reaction of CO2 with alkylethylenediamines (N···O distances of 2.664(5)–2.810(2) Å).52

In addition, hydrogen bonding between an ammonium proton and the non-bridging carboxylate oxygen atom of the dobpdc4− ligand was observed with an N···O distance of 2.806(9) Å. The sum of these interactions stabilizes a single, highly-ordered ammonium carbamate chain conformation, in contrast to the significant disorder of the diamine observed in the structure prior to CO2 insertion. Importantly, space-filling models (Figures S16–S19) reveal that m-2-m–Zn2(dobpdc) and other diamine-appended analogues maintain significant porosity even following CO2 insertion, a feature that should facilitate rapid gas diffusion through the pores.

The structure of CO2-dosed e-2-e–Zn2(dobpdc) at 195 K shows a similar network of electrostatic interactions. In this case, a Zn–O(carbamate) bond length of 2.135(12) Å was observed, which is 0.048(16) Å longer than that of the Zn–O(carbamate) bond with m-2-m. The ammonium carbamate chains refined to an occupancy of 0.501(15), yielding a formula of Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e)(e-2-e–CO2). The ethyl substituents of the ammonium nitrogen atoms appear to overlap in the a/b plane, which, in conjunction with the apparent second adsorption step in the CO2 adsorption isobar of e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc) (Figure 3a), suggests that a structural rearrangement must occur at half loading to accommodate complete filling (1 CO2 per diamine) of the CO2 inserted phase.

We were further able to obtain the first structures showing CO2 insertion into 1°/2° diamine-appended Zn2(dobpdc) frameworks. For e-2– and i-2–Zn2(dobpdc), CO2 inserts into the bond between the metal and the 1° amine, while the secondary amine forms the corresponding ammonium cation. In both structures, a dominant conformation could be identified and refined to approximately 50% occupancy. The ammonium carbamate chains in these structures exhibit different hydrogen-bonding and ion-pairing networks upon CO2 insertion compared to those found in the 2°/2° diamine structures. Specifically, the 1°/2° CO2-inserted structures show ion pairing of the ammonium with the bound oxygen atom of the carbamate instead of the unbound oxygen. The preference for ion-pairing with the bound oxygen may be explained by the ability of these ammonium carbamate chains to approach the framework more closely, due to the absence of substituents on the carbamate-forming amine. As with the ammonium carbamate chains formed by 2°/2° diamines, the chains formed by 1°/2° diamines also interact with the framework through hydrogen bonding of the ammonium with the ligand. An additional hydrogen bonding interaction was identified between the proton on the carbamate nitrogen and the bridging carboxylate oxygen atom of the ligand. These structures suggest that the ammonium carbamate phases of the 1°/2° diamines are more stable than their 2°/2° analogues. However, this is offset by the stronger M–N bond, ultimately resulting in slightly less favorable CO2 adsorption in these materials.

A second chain conformation with an occupancy of 26.4(1.3)% was found in the CO2-inserted structure of e-2–Zn2(dobpdc) (Figure S18). In contrast to the dominant conformation, this chain structure shows an ion-pairing interaction between the ammonium and the unbound carbamate oxygen atom. As a result, the ethyl groups on the ammonium are shifted toward the pore interior, alleviating steric crowding in the a/b plane. However, the resulting loss of the hydrogen bonding interaction between the ammonium and the framework ligand likely makes this conformation less energetically favorable. While a second chain conformation could not be identified in the CO2-inserted structure of i-2–Zn2(dobpdc), a similar conformational change must occur to accommodate CO2 loadings of greater than 50% due to the apparent overlap of the isopropyl groups in the a/b plane. Furthermore, a secondary conformational shift would explain the second step in the adsorption isobars and isotherms for i-2–Mg2(dobpdc).

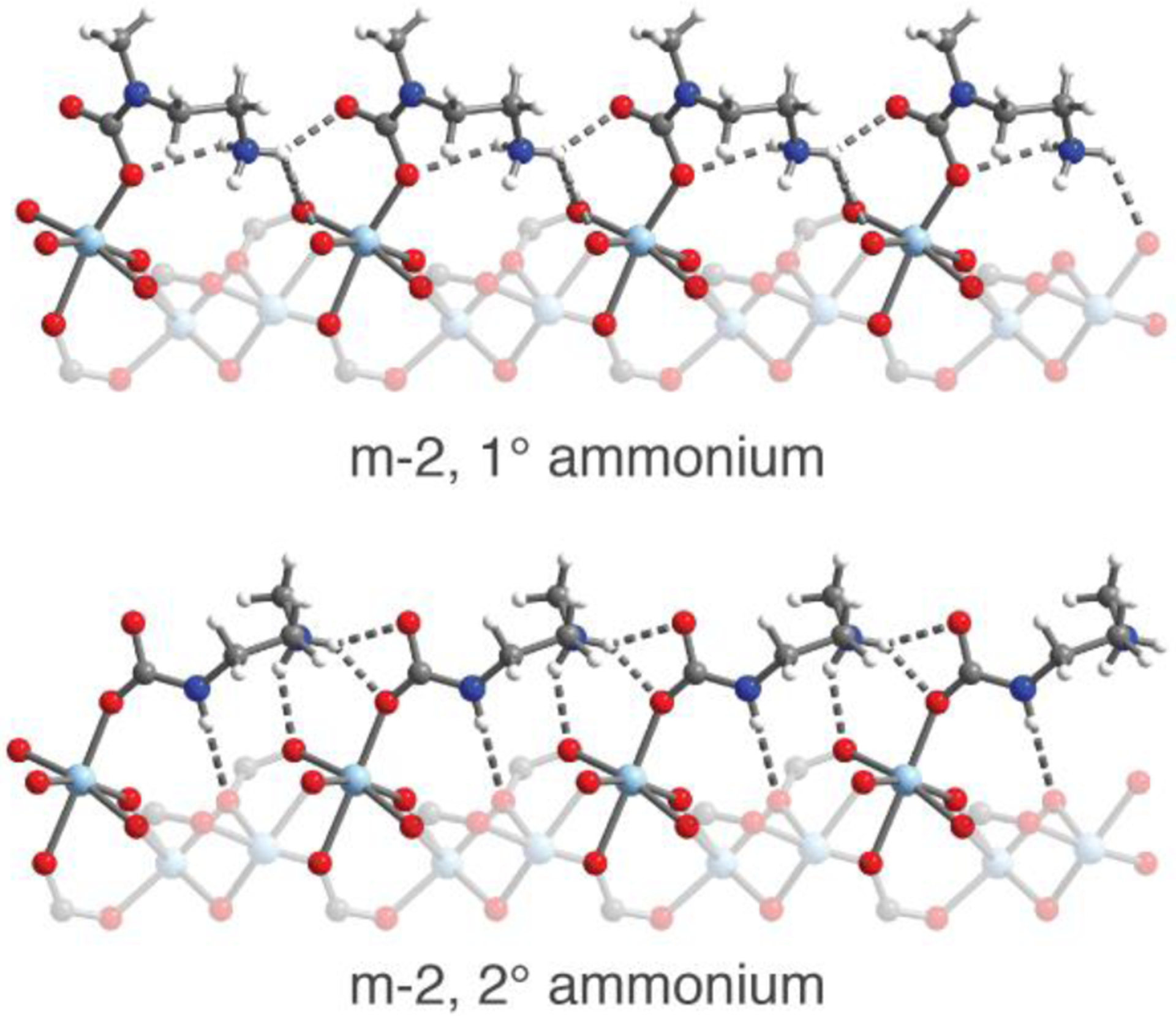

In the structure of CO2-inserted m-2–Zn2(dobpdc) at 100 K, two conformations were identified (Figure 5). The dominant conformation (51.7(9)% occupancy relative to Zn) is similar to that of e-2 and i-2 but features ion-pairing interactions between the ammonium and both carbamate oxygen atoms (Figure 5, bottom). Additionally, a second ammonium carbamate chain conformation was resolved in which the primary amine forms the ammonium and the secondary amine forms the carbamate. In this conformation, refined at 29.2(9)% occupancy, one of the ammonium protons interacts with both the bound oxygen atom of the carbamate of the same site, as well as with the unbound oxygen atom of the neighboring carbamate along the c axis (Figure 5, top). This conformation is unique among the diamine-appended frameworks investigated in this study and likely forms due to the comparatively small size of m-2. The stabilization of the CO2-inserted phase resulting from these additional ion-pairing and hydrogen-bonding interactions may explain the increase in adsorption step temperature for m-2–Mg2(dobpdc) relative to m-2-m–Mg2(dobpdc), a deviation from the trend of decreasing step temperature observed for other 1°/2° diamines relative to their 2°/2° counterparts.

Figure 5.

The structures of two conformations of the ammonium carbamate chains in Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2–CO2)1.62 at 100 K as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. A primary ammonium forms in the first conformation (top, 29.2(9)% occupancy relative to ZnII), while a secondary ammonium forms in the second conformation (bottom, 51.7(9)% occupancy). Light blue, blue, red, gray, and white spheres represent Zn, N, O, C, and H atoms, respectively.

Efforts to observe CO2 insertion crystallographically with 1°/3° diamine-appended frameworks are ongoing. Nonetheless, the step-like CO2 adsorption behavior of the 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) analogues suggests that they also form ammonium carbamate chains. Further support for CO2 insertion with 1°/3° analogues is provided by the similar C–O (~1650 cm−1) and C–N (~1330 cm−1) carbamate vibrations in the infrared spectra of CO2-dosed 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks compared to the 1°/2° and 2°/2° diamine-appended analogues (Figure S6 and Table S1). The envisioned ammonium carbamate chains for 1°/3° diamines cannot achieve the hydrogen-bonding interactions observed for the 1°/2° and 2°/2° diamines between the ammonium or carbamate protons and the oxygen atoms of the ligand. The loss of these interactions is consistent with reduced stability of the ammonium carbamate phase and the resulting lower adsorption step temperatures observed by thermogravimetric analysis (Figure 3).

Process Considerations Derived from High-Throughput CO2 Adsorption Isotherms.

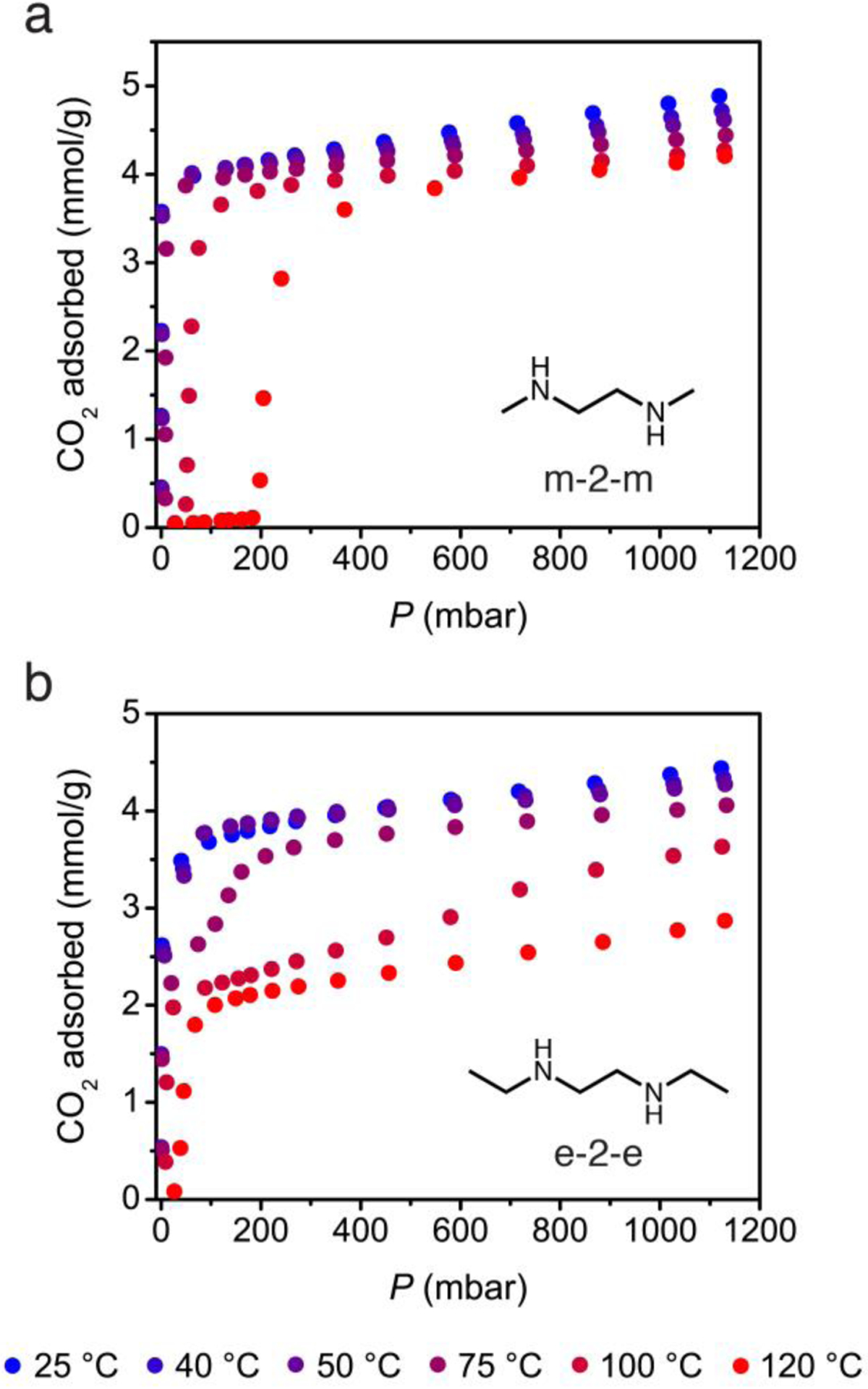

Using a custom-built, high-throughput, volumetric adsorption instrument,12 CO2 adsorption isotherms were collected at six temperatures for each diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) analogue. These measurements establish the characteristic range and temperature dependence of the adsorption step pressures for each material at temperatures relevant to typical CO2 separations, thereby guiding the development and selection of diamine-appended adsorbents for specific capture applications. In addition, N2 isotherms were collected and confirm the high CO2/N2 selectivity of these adsorbents (Figure S13).

The CO2 adsorption isotherms of the diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) series (Figures 6 and 7) demonstrate the wide range of step pressures accessible through systematic modification of the diamine structure. Sharp CO2 adsorption steps were observed for each analogue, following trends consistent with the isobaric adsorption data. The isotherms highlight the minimal uptake of CO2 prior to the adsorption step, the defining feature of these materials that gives rise to their high CO2 adsorption capacities. Desorption isobars under pure CO2 (Figure S10) confirm that the full capacity of the ammonium carbamate chains can be accessed to yield high gravimetric capacities on the order of 3.5–4.0 mmol/g for the adsorbents in this work. These gravimetric capacities correspond to volumetric capacities of 79–84 v/v, as calculated using the crystallographic densities.53

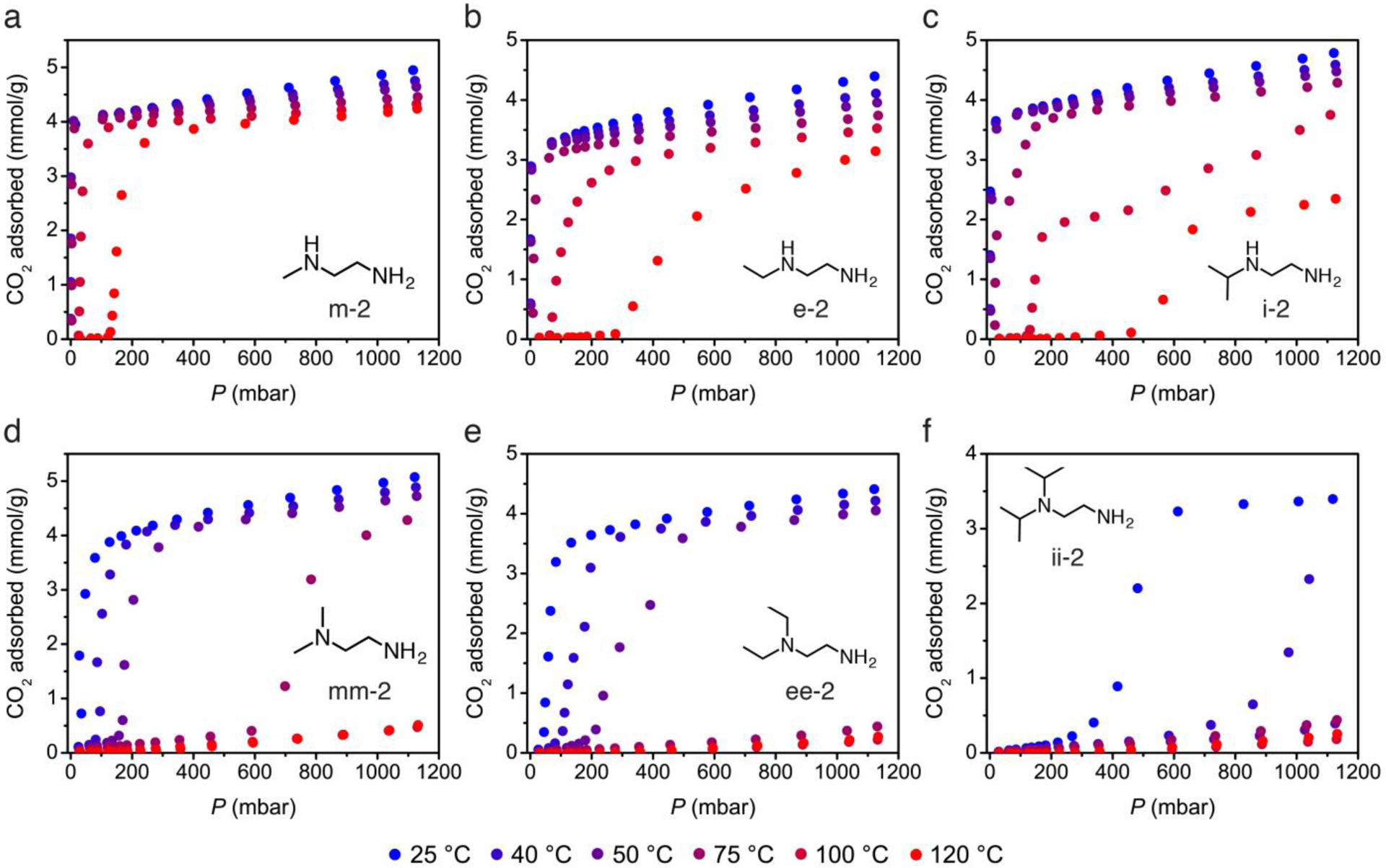

Figure 6.

High-throughput CO2 adsorption isotherms over a range of 25 to 120 °C for the 1°/2° and 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks examined in this work.

Figure 7.

High-throughput CO2 adsorption isotherms over a range of 25 to 120 °C for m-2-m– and e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc).

To design a promising cooperative adsorbent for a target application, the partial pressure of CO2 in the target gas stream must first be considered, as this will dictate the upper bound for the CO2 adsorption step pressure at the temperature of interest. However, the cooperative adsorption step must be positioned at a sufficiently low pressure for capture to occur at the lowest concentration needed to achieve the desired capture rate or product gas purity. Importantly, this concern is intrinsic to all materials possessing step-shaped isotherms, as these materials will cease adsorption as soon as the adsorbate partial pressure in the bed drops below the threshold pressure for adsorption.

As an example, any material that saturates with CO2 at a pressure below 150 mbar will be able to bind CO2 from a stream of coal flue gas containing 150 mbar of CO2. However, in order to capture 90% of the CO2 from this stream, the adsorbent must possess a step that enables CO2 insertion at a partial pressure as low as 10% of 150 mbar, or 15 mbar, at the target adsorption temperature. Likewise, achieving 90% CO2 capture from a natural gas flue gas stream containing 40 mbar of CO2 requires adsorption at a CO2 partial pressure of 4 mbar. At the standard adsorption temperature of 40 °C, the coal and natural gas 90% capture conditions are satisfied by each of the 1°/2° diamines, which possess 40 °C step pressures of < 0.2 mbar, < 0.7 mbar, and < 1 mbar for m-2–, e-2–, and i-2–Mg2(dobpdc), respectively, as determined from the inflection points within the adsorption step. In addition, desorption isobars of CO2-saturated 1°/2° diamine-appended frameworks indicate that these materials can be fully regenerated under a flow of pure CO2 at temperatures of 148, 134, and 123 °C for m-2–, e-2–, and i-2–Mg2(dobpdc), respectively (Figure S10, Table S3). These moderate regeneration temperatures underscore the potential utility of these materials in temperature swing adsorption processes.

For the 1°/3° diamines, the isothermal cooperative threshold pressures are greatly increased compared to 2°/2° and 1°/2° diamines, owing to the combined stabilization of the amine-bound phase (stronger metal–amine bond) and destabilization of the product phase (weaker ion pairing). At 40 °C, the frameworks mm-2– and ee-2–Mg2(dobpdc) display step pressures of approximately 100 mbar, while that of ii-2–Mg2(dobpdc) is close to 1 bar. Desorption isobars indicate that mm-2–, ee-2–, and ii-2–Mg2(dobpdc) can be regenerated at 88, 73, and 68 °C, respectively under pure CO2 (Figure S10, Table S3). Desorption at temperatures below 100 °C allows the use of much lower quality steam for thermal regeneration of these materials, enabling significant energy savings. The low desorption temperature of mm-2–Mg2(dobpdc) led to its prior evaluation for separation of CO2 from coal flue gas.24 However, these 1°/3° diamine-appended frameworks can only achieve a maximum of 33% capture from a coal flue gas stream at 40 °C. As a result, practical use of these adsorbents is limited to cases where a lower capture rate is acceptable or where an inlet stream at lower temperature or higher CO2 partial pressure can be obtained.

As an additional advantage, frameworks appended with 1°/3° diamines exhibit reduced water uptake in the absence of CO2 compared to frameworks appended with 2°/2° and 1°/2° diamines (Figure S14). Therefore, modification of the diamine structure allows control not only over the threshold for CO2 adsorption, but also over the hydrophobicity of the framework pores. Importantly, previous multicomponent equilibrium experiments under simulated coal flue gas confirmed that cooperative CO2 adsorption is preserved in these materials in the presence of water.12 By segregating the CO2 and H2O binding sites and minimizing water co-adsorption, significant savings in regeneration energy can thus be achieved with diamine-appended frameworks by diminishing the energetic costs associated with desorption of large quantities of water between cycles. Moving forward, additional multicomponent experiments under realistic mixed-gas conditions will be a central focus in advancing these materials toward specific applications, as single-component isotherms on the diamine-bound phase may not adequately reflect the affinity of other species in a mixture for the CO2-inserted phase.

The CO2 adsorption isotherms for m-2-m–Mg2(dobpdc) reported here display step positions in good agreement with those observed previously (Figure 7a).21,23 For e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc), destabilization of the amine-bound phase reduces the CO2 insertion step pressure for the first step by an order of magnitude at each temperature, with step pressures of approximately 1, 10, and 50 mbar occurring at 75, 100, and 120 °C, respectively (Figure 7b). Thus, adsorbents capable of scrubbing CO2 at ultradilute concentrations can be designed through the use of sterically encumbered amines that facilitate weak dative metal–amine interactions. Indeed, the ability of m-2-m–Mg2(dobpdc) to capture CO2 from air (400 ppm) has been demonstrated previously,21 and the lower step pressures of e-2-e–Mg2(dobpdc) would enable an increased capture rate from air or capture from streams containing even lower partial pressures of CO2.

Calculation of equivalent energy (MJ/kg CO2 captured and compressed to 150 bar) as a function of the adsorption partial pressure of CO2 indicates that energies on the order of 1.1 MJ/kg CO2 can be achieved with 2°/2° and 1°/2° diamine-appended frameworks for dilute CO2 streams (Figure S15a–b, Table S3). For more concentrated CO2 streams (> 120 mbar CO2), equivalent energies approaching 0.5 MJ/kg CO2 captured may be possible with 1°/3° diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks (Figure S15c, Table S3). Considering CO2 capture from a supercritical coal-fired power plant as an example, these numbers compare favorably with the Department of Energy baseline for absorption-based capture with the amine solution Cansolv,54 for which an analogous calculation yields an equivalent energy of 0.935 MJ/kg CO2 for capture over the range of 128.8 mbar to 16.3 mbar of CO2 (Figure S15).

Novel process configurations that leverage the step-shaped adsorption within these materials may afford further savings in regeneration energy. For example, while Langmuir-type adsorbents require adsorption at the lowest possible temperature to maximize the working capacity, cooperative adsorbents can operate at higher adsorption temperatures, with the maximum adsorption temperature dictated by the desired CO2 capture rate and purity. Pressure and vacuum swing adsorption processes may likewise afford savings in regeneration energy as well as decreased cycle times. The potential engineering advantages of these materials have already received attention,27 and we and others are exploring additional process configurations to achieve further reductions in the capital and operating costs of CO2 capture.

Thermodynamics of CO2 Adsorption.

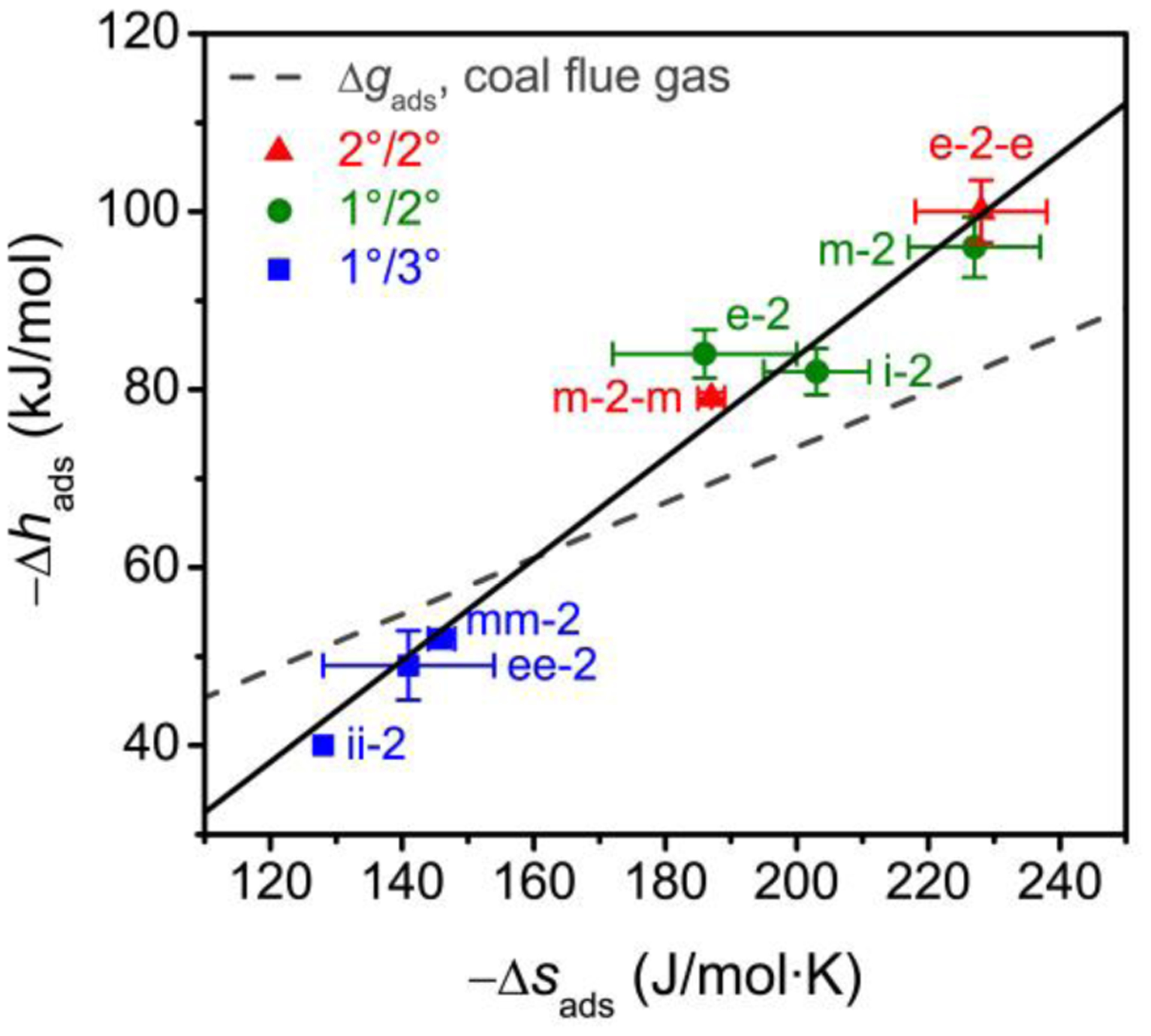

Characterization of the thermodynamics of CO2 adsorption in these materials imparts further insight on the influence of diamine structure on cooperative adsorption and provides key parameters necessary for industrial applications. The differential enthalpies and entropies of cooperative CO2 adsorption (Δhads and Δsads) for the diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) series were obtained using the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship. For each framework, lines at a constant loading of 1 mmol/g (0.2–0.3 mmol CO2/mmol Mg) were calculated across all temperatures by linear interpolation within the CO2 isotherm step. Plotting the corresponding pressures and temperatures as ln P vs. 1/T afforded the differential enthalpy and entropy of adsorption from the slope and y-intercept, respectively, of the resulting lines.

As shown in Figure 8 and Table S3, more exothermic CO2 adsorption correlates with more negative adsorption entropies. As |Δhads| increases, the ammonium carbamate units in the CO2-inserted phase interact more strongly with one another and with the framework walls, leading to a greater loss of entropy upon CO2 adsorption. Similar compensating effects have been observed previously for both gas adsorption55,56 and a number of other chemical processes.57 Furthermore, large |Δhads| values were found to correlate with lower step pressures, a result consistent with the need to offset the larger gas-phase entropy of CO2 at low pressures.

Figure 8.

Plot of the differential enthalpy (−Δhads) vs. differential entropy (−Δsads) of CO2 adsorption for alkylethylenediamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) frameworks, as calculated using a Clausius–Clapeyron relationship at a loading of 1 mmol/g (within the first step of the cooperative adsorption region) for isotherms over a range of 25 to 120 °C. A linear relationship is apparent (black line, R2 = 0.97), demonstrating enthalpy–entropy compensation for cooperative CO2 adsorption in this class of materials. Materials above the dashed gray line are predicted to be capable of capturing 90% of the CO2 from a coal flue gas stream (15% CO2 in N2 at 40 °C).

Relative to the 2°/2° diamines, the 1°/2° diamines show an increase in the stability of the CO2-inserted phase due to the additional hydrogen-bonding interactions, as observed crystallographically. However, the 1°/2° diamines also show increased Mg–N bond strengths relative to the 2°/2° frameworks. The combined stabilization of the amine-bound and CO2-bound phases leads to similar −Δhads and −Δsads values for 1°/2° and 2°/2° analogues. For the 1°/3° frameworks, stabilization of the amine-bound phase and destabilization of the ammonium carbamate ion pairing results in the lowest |Δhads| and |Δsads| values (and thus the highest CO2 adsorption step pressures) of the series.

Beyond demonstrating the enthalpy–entropy tradeoff for CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended frameworks, these plots can be used to illustrate thermodynamic cutoffs for specific separation and capture targets. At equilibrium,

| (2) |

Here, Δgads is the free energy of adsorption, R is the universal gas constant, p is the partial pressure of CO2, and p0 = 1 bar is the reference pressure. Using this relationship, the Δgads required to achieve a target separation can be determined from the adsorption temperature T and minimum adsorption partial pressure p, which in turn is determined from the inlet CO2 concentration and desired capture rate. Using the relation

| (3) |

lines of constant Δgads and T can be drawn on the enthalpy–entropy correlation plot as a visual guide for predicting the viability of an adsorbent for a given process. An example is shown in Figure 8, where a line of Δgads = −10.9 kJ/mol has been drawn to represent the target differential enthalpy and entropy needed to achieve 90% CO2 capture from coal flue gas (step pressure of 15 mbar at 40 °C). Adsorbents above this line, including all 2°/2° and 1°/2° diamine-appended frameworks explored in this work, are predicted to meet the separation target, while those below the line will fall short of the 90% CO2 capture rate. Similar analyses can be performed for other mixtures of interest, such as natural gas flue gas (see Table S3). Materials that fall on the line will operate with the highest thermodynamic efficiency in a given process by minimizing the regeneration energy. Importantly, for diamine-appended frameworks, energetic savings can be achieved not only by modifying the adsorbent structure to match the target Δgads, but also by modifying the process configuration (for example, increasing the adsorption temperature) to shift the Δgads line toward the known adsorbent points.

CONCLUSIONS

The foregoing results demonstrate that variation of the diamine structure can be used to control cooperative CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended M2(dobpdc) frameworks. Gas adsorption measurements coupled with in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments enabled identification of the principal structural features that influence CO2 adsorption. First, steric bulk on the metal-bound amine leads to lower step pressures by destabilizing the diamine-bound phase. Second, adding substituents on the terminal amine increases the step pressure due to weaker ion-pairing interactions within ammonium carbamate chains formed upon CO2 insertion. Third, specific ion-pairing and hydrogen-bonding interactions stabilize the CO2-inserted phase and consequently decrease the threshold pressure for cooperative CO2 adsorption. These structural considerations result in a compensating effect between the differential enthalpy and entropy of adsorption, as revealed by thermodynamic analysis of the gas adsorption isotherms of these materials.

The structural and thermodynamic relationships identified here allow the selection or design of diamine-appended frameworks with CO2 step positions ideally suited to minimize the energy consumed in a temperature or pressure swing process. In ongoing work, we are studying the application of these materials to specific CO2 separations, including CO2 capture from flue gases, biogas, and crude methane streams. Critically, we are working to characterize all parameters necessary for complete process modeling, with particular attention to the kinetics of adsorption and the stability of these materials to cycling in the presence of water and other impurities. We further anticipate that these materials will afford engineering opportunities to design new process configurations, such as high-temperature operation, to maximize the utility of the cooperative adsorption mechanism.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Materials synthesis and collection of adsorption data were funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E), U.S. Department of Energy under award number DE-AR0000402. Structural studies were supported by the Center for Gas Separations Relevant to Clean Energy Technologies, an Energy Frontier Research Center supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0001015. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected on Beamline 11.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. J.D.M. thanks the Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science for a postdoctoral fellowship. P.J.M. thanks the National Institutes of Health for a postdoctoral fellowship (GM120799). We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Hye Jeong Park for the development of a gram-scale synthesis of Zn2(dobpdc) powder and Dr. Simon Weston for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(DMA)2 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2-m)1.46 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e)1.26 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2)1.68 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(i-2)1.94 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(mm-2)1.83 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(ee-2)1.65 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2-m–CO2)1.5 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2-e)(e-2-e–CO2) (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(m-2–CO2)1.62 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(e-2–CO2)1.5 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for Zn2(dobpdc)(i-2)(i-2–CO2) (CIF)

Additional experimental details, including gas adsorption data, infrared spectroscopy, equivalent energy calculations, and crystallographic tables (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest: T.M.M. and J.R.L. have a financial interest in Mosaic Materials, Inc., a start-up company working to commercialize metal–organic frameworks for gas separations. U.C. Berkeley has applied for a patent on some of the materials discussed herein, on which T.M.M. and J.R.L. are included as inventors.

REFERENCES

- (1).Dlugokencky E; Tans P ESRL Global Monitoring Division - Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ (accessed Jan 25, 2017).

- (2).International Energy Agency. CO2 Emissions From Fuel Combustion: Highlights 2016. https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/CO2EmissionsfromFuelCombustion_Highlights_2016.pdf (accessed Jan 25, 2017).

- (3).In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer O; Sokona Y; Farahani E; Kadner S; Seyboth K; Adler A; Baum I; Brunner S; Eickemeier P; Kriemann B; Savolainen S; Schlömer S; von Stechow C; Zwickel T; Minx JC; Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Boot-Handford ME; Abanades JC; Anthony EJ; Blunt MJ; Brandani S; Dowell NM; Fernández JR; Ferrari M-C; Gross R; Hallett JP; Haszeldine RS; Heptonstall P; Lyngfelt A; Makuch Z; Mangano E; Porter RTJ; Pourkashanian M; Rochelle GT; Shah N; Yao JG; Fennell PS Energy Environ. Sci 2013, 7 (1), 130–189. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Pacala S; Socolow R Science 2004, 305 (5686), 968–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Holm-Nielsen JB; Al Seadi T; Oleskowicz-Popiel P Bioresour. Technol 2009, 100 (22), 5478–5484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Rochelle GT Science 2009, 325 (5948), 1652–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wang M; Lawal A; Stephenson P; Sidders J; Ramshaw C Chem. Eng. Res. Des 2011, 89 (9), 1609–1624. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bhown AS; Freeman BC Environ. Sci. Technol 2011, 45 (20), 8624–8632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Choi S; Drese JH; Jones CW ChemSusChem 2009, 2 (9), 796–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Samanta A; Zhao A; Shimizu GKH; Sarkar P; Gupta R Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2012, 51 (4), 1438–1463. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mason JA; McDonald TM; Bae T-H; Bachman JE; Sumida K; Dutton JJ; Kaye SS; Long JR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (14), 4787–4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sumida K; Rogow DL; Mason JA; McDonald TM; Bloch ED; Herm ZR; Bae T-H; Long JR Chem. Rev 2012, 112 (2), 724–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Li J-R; Ma Y; McCarthy MC; Sculley J; Yu J; Jeong H-K; Balbuena PB; Zhou H-C Coord. Chem. Rev 2011, 255 (15–16), 1791–1823. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang Q; Luo J; Zhong Z; Borgna A Energy Environ. Sci 2010, 4 (1), 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lin Y; Kong C; Chen L RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (39), 32598–32614. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yu J; Xie L-H; Li J-R; Ma Y; Seminario JM; Balbuena PB Chem. Rev [Online early access]. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00626 . Published Online: Apr 10, 2017. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00626http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00626. Published Online: Apr 10, 2017. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00626 (accessed Apr 24, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- (18).Demessence A; D’Alessandro DM; Foo ML; Long JR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131 (25), 8784–8786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).McDonald TM; D’Alessandro DM; Krishna R; Long JR Chem. Sci 2011, 2 (10), 2022–2028. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Choi S; Watanabe T; Bae T-H; Sholl DS; Jones CW J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2012, 3 (9), 1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).McDonald TM; Lee WR; Mason JA; Wiers BM; Hong CS; Long JR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (16), 7056–7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lee WR; Hwang SY; Ryu DW; Lim KS; Han SS; Moon D; Choi J; Hong CS Energy Environ. Sci 2014, 7 (2), 744–751. [Google Scholar]

- (23).McDonald TM; Mason JA; Kong X; Bloch ED; Gygi D; Dani A; Crocellà V; Giordanino F; Odoh SO; Drisdell WS; Vlaisavljevich B; Dzubak AL; Poloni R; Schnell SK; Planas N; Lee K; Pascal T; Wan LF; Prendergast D; Neaton JB; Smit B; Kortright JB; Gagliardi L; Bordiga S; Reimer JA; Long JR Nature 2015, 519 (7543), 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee WR; Jo H; Yang L-M; Lee H; Ryu DW; Lim KS; Song JH; Min DY; Han SS; Seo JG; Park YK; Moon D; Hong CS Chem. Sci 2015, 6 (7), 3697–3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yeon JS; Lee WR; Kim NW; Jo H; Lee H; Song JH; Lim KS; Kang DW; Seo JG; Moon D; Wiers B; Hong CS J Mater Chem A 2015, 3 (37), 19177–19185. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Liao P-Q; Chen X-W; Liu S-Y; Li X-Y; Xu Y-T; Tang M; Rui Z; Ji H; Zhang J-P; Chen X-M Chem. Sci 2016, 7 (10), 6528–6533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hefti M; Joss L; Bjelobrk Z; Mazzotti M Faraday Discuss. 2016, 192, 153–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jo H; Lee WR; Kim NW; Jung H; Lim KS; Kim JE; Kang DW; Lee H; Hiremath V; Seo JG; Jin H; Moon D; Han SS; Hong CS ChemSusChem 2017, 10 (3), 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Long JR; McDonald TM Cooperative chemical adsorption of acid gases in functionalized metal-organic frameworks. US20170087531 A1, March 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Drisdell WS; Poloni R; McDonald TM; Pascal TA; Wan LF; Pemmaraju CD; Vlaisavljevich B; Odoh SO; Neaton JB; Long JR; Prendergast D; Kortright JB Phys Chem Chem Phys 2015, 17 (33), 21448–21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Irving H; Williams RJP J. Chem. Soc 1953, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lindsey AS; Jeskey H Chem. Rev 1957, 57 (4), 583–620. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gonzalez MI; Mason JA; Bloch ED; Teat SJ; Gagnon KJ; Morrison GY; Queen WL; Long JR Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 4387–4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).SAINT, APEX2, and APEX3 Software for CCD Diffractometers; Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sheldrick GM SADABS; University of Göttingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sheldrick GM Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv 2015, 71 (1), 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Sheldrick GM Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem 2015, 71 (1), 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Dolomanov OV; Bourhis LJ; Gildea RJ; Howard J. a. K.; Puschmann H J. Appl. Crystallogr 2009, 42 (2), 339–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Campbell CT; Sellers JRV Chem. Rev 2013, 113 (6), 4106–4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Caskey SR; Wong-Foy AG; Matzger AJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (33), 10870–10871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Deng H; Grunder S; Cordova KE; Valente C; Furukawa H; Hmadeh M; Gándara F; Whalley AC; Liu Z; Asahina S; Kazumori H; O’Keeffe M; Terasaki O; Stoddart JF; Yaghi OM Science 2012, 336 (6084), 1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Vaidhyanathan R; Iremonger SS; Shimizu GKH; Boyd PG; Alavi S; Woo TK Science 2010, 330 (6004), 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kim H; Kim Y; Yoon M; Lim S; Park SM; Seo G; Kim KJ Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (35), 12200–12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Liao P-Q; Zhou D-D; Zhu A-X; Jiang L; Lin R-B; Zhang J-P; Chen X-M J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (42), 17380–17383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Queen WL; Hudson MR; Bloch ED; Mason JA; Gonzalez MI; Lee JS; Gygi D; Howe JD; Lee K; Darwish TA; James M; Peterson VK; Teat SJ; Smit B; Neaton JB; Long JR; Brown CM Chem. Sci 2014, 5 (12), 4565–4581. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Takamizawa S; Nataka E; Akatsuka T; Miyake R; Kakizaki Y; Takeuchi H; Maruta G; Takeda S J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (11), 3783–3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lama P; Aggarwal H; Bezuidenhout CX; Barbour LJ Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (42), 13271–13275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Castro J; Castineiras A; Duran ML; Garcia-Vazquez JA; Macias A; Romero J; Sousa A Z. Für Anorg. Allg. Chem 1990, 586 (1), 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Yamaguchi S; Takahashi T; Wada A; Funahashi Y; Ozawa T; Jitsukawa K; Masuda H Chem. Lett 2007, 36 (7), 842–843. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Notni J; Schenk S; Görls H; Breitzke H; Anders E Inorg. Chem 2008, 47 (4), 1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).An J; Fiorella RP; Geib SJ; Rosi NL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131 (24), 8401–8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Tiritiris I; Kantlehner W Z. Naturforsch 2011, 66b, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- (53).The unit v/v corresponds to cm3STP/cm3, where STP is defined as 273.15 K and 1 atm. Volumetric capacities of the frameworks Mg2(dobpdc)(diamine)2 were calculated using crystallographic densities approximated from the 100 K single-crystal unit cell volumes of the analogous zinc frameworks.

- (54).Cost and Performance Baseline for Fossil Energy Plants. Volume 1a: Bituminous Coal (PC) and Natural Gas to Electricity. Revision 3; DOE/NETL-2015/1723; U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Garrone E; Bonelli B; Otero Areán C Chem. Phys. Lett 2008, 456 (1–3), 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Areán CO; Chavan S; Cabello CP; Garrone E; Palomino GT ChemPhysChem 2010, 11 (15), 3237–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Liu L; Guo Q-X Chem. Rev 2001, 101 (3), 673–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.