Abstract

Enteroendocrine cells (EECs) are specialized cells that are widely distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract. EECs sense luminal content and release hormones, such as: ghrelin, cholecystokinin, glucagon like peptide 1, peptide YY, insulin like peptide 5, and oxyntomodulin. These hormones can enter the circulation to act on distant targets or act locally on neighboring cells and neuronal pathways to modulate food digestion, food intake, energy balance and body weight. Obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes are associated with alterations in the levels of enteroendocrine hormones. Evidence also suggests that modified regulation and release of gut hormones are the result of compensatory mechanisms in states of excess adipose tissue and hyperglycemia. This review collects the evidence available detailing pathophysiological alterations in enteroendocrine hormones and their association with appetite, obesity and glycemic control.

Keywords: Enteroendocrine hormones, Obesity, Diabetes, Appetite

1. Introduction

Obesity is defined as excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health(Heymsfield and Wadden 2017). Obesity is a chronic, relapsing, multifactorial disorder, whose prevalence continues to increase worldwide (Ng, Fleming et al. 2014) and, in the United States, 42.4% of adults have obesity(Hales, Carroll et al. 2020). Obesity is a central player in the pathophysiology of many chronic diseases, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The excess of adiposity in obesity leads to the establishment of a low grade systemic inflammatory state, a main contributor to the pathophysiology underlying impaired insulin signaling and eventually insulin resistance and T2DM (Heymsfield and Wadden 2017).

Similar to obesity, T2DM is a highly complex metabolic disease; which is characterized by elevated blood glucose concentration due to failure in the production of insulin by the pancreatic beta cells, reduced sensitivity to insulin, or both (Triplitt, Solis-Herrera et al. 2015). The 2017 National Diabetes Statistic Report indicates that 87.5% of adults with diabetes were either overweight or had obesity, and the prevalence of obesity related diabetes is expected to double, up to 300 million by 2025(Leitner, Fruhbeck et al. 2017). These studies represent considerable accumulating evidence demonstrating that weight regulation plays an important role in diabetes prevention and treatment.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract plays a central role in maintaining energy balance and body weight regulation. These functions are mediated by the secretion of gut hormones, including ghrelin, cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY(PYY), glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP1), insulin like peptide 5 (INSL5), and oxyntomodulin (OXM) (Mishra, Dubey et al. 2016). Current evidence suggests that dysregulation in gut hormone secretion may be associated with metabolic disturbances, such as obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM (Steinert, Feinle-Bisset et al. 2017). Accordingly, with an increase in the prevalence of obesity and obesity related comorbidities, enteroendocrine hormones have become an important topic of investigation. This review aims to summarize the pathological changes to the regulation of the enteroendocrine hormones and their association with obesity and T2DM.

2. Enteroendocrine cell physiology

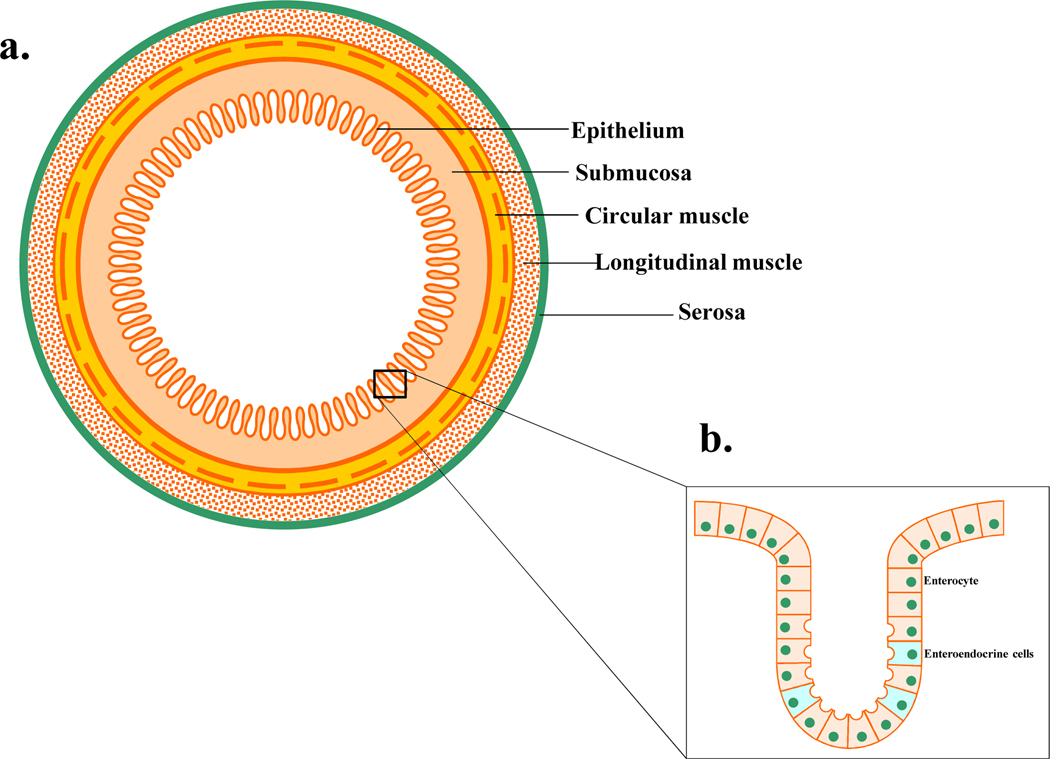

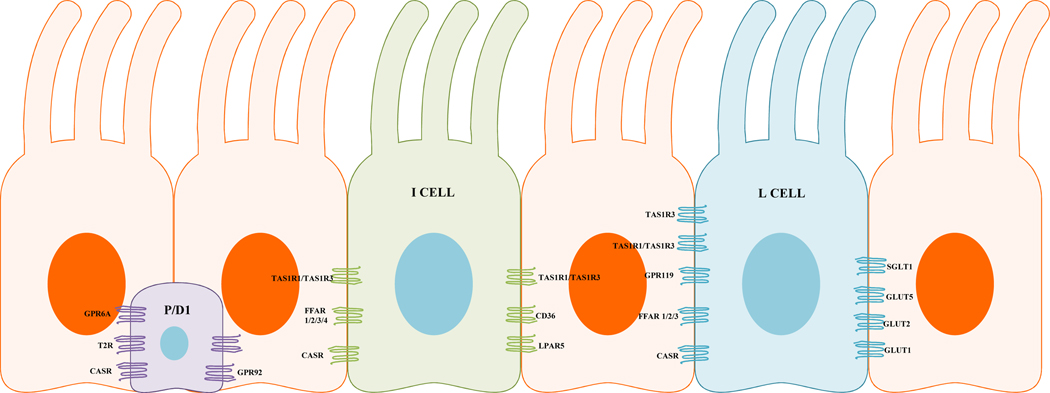

Enteroendocrine cells (EECs) account for less than 1% of the epithelial cells, are distributed along the entire GI mucosa in the crypts and villi (Fig1) and are specialized cells capable of sensing luminal content, producing and releasing hormone signaling molecules to modulate a variety of physiological GI functions. Depending on their individual morphology and position in the GI mucosa, EECs are divided into “Open Type” and “Closed type”. The open-type EECs directly detect luminal contents through the microvilli, whereas the closed type are activated by luminal content indirectly through neural or humoral pathways (Latorre, Sternini et al. 2016) (Fig2). Both closed and open type EECs accumulate their secretory products in cytoplasmic granules and release them by exocytosis at the basolateral membrane upon mechanical, chemical or neural stimulations (Latorre, Sternini et al. 2016). Their secretory products may then act in a paracrine manner, endocrine manner or on nerve endings close to the site of release.

Figure 1.

a) Schematic representation of the gastrointestinal tract layers. b) Mucosa layer contains enterocyte and enteroendocrine cells.

Figure 2.

Gut epithelium showing different enteroendocrine cells types, and their associated receptors. Purple (closed type enteroendocrine cell), green/blue (open type enteroendocrine cells). CASR, calcium sensing receptor; CD36, thrombospondin receptor; FFAR, free fatty acid receptor; GLUT, glucose transporter; GPR, G protein coupled receptor; LPAR5, lysophosphatidic acid receptor 5; SGLT1 Sodium glucose transporter 1; TAS1R1, taste receptor type 1, member 1; TAS1R2, taste receptor type 1, member 2; TAS1R3, taste receptor type 1, member 3 (T1R1/T1R3); T2R, Taste receptor type 2.

EECs are also classified according to the principal hormones they produce. While some hormones are produced throughout the entire length of the gut, others are produced in a particular location (Engelstoft, Egerod et al. 2013) (Table 1). Recent evidence has now shown there is considerable co expressions of hormones within individual types of cells, and the traditional classification now appears inadequate(Engelstoft, Egerod et al. 2013).

Table 1.

CCK, Cholecystokinin; GIP, Gastric inhibitory polypeptide; GLP1, glucagon like peptide 1; GLP 2, glucagon like peptide 2; 5 HT, 5 hydroxytryptamine; INSL 5, Insulin like peptide 5; OXM, Oxyntomodulin; PYY, Peptide YY; SST: Somatostatin.

| Gut region | Principal gut hormones | Type of cells | Luminal stimuli |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | 5-HT | Enterochromaffin cells | Acid, digestived protein |

| Gastrin | G cells | ||

| Histamine | Enterochromaffin like cells | ||

| SST | D cells | ||

| Ghrelin | P/D1 cells | ||

| Duodenum | SST | D cells | Monosaccharides, free fatty acids, Monoacylglycerol s, Aminoacids, di/tripeptides, bile acids |

| Ghrelin | P/D1 cells | ||

| 5-HT | Enterochromaffin cells | ||

| GIP | K cells | ||

| CCK | I cells | ||

| Secretin | S cells | ||

| Jejunum, Ileum, colon and Rectum | GLP-1 | L cells | Bile acids, unabsorbed nutrients, short chain fatty acids, secondary bile acids |

| GLP-2 | |||

| OXM | |||

| PYY | |||

| INSL-5 |

Release of hormone products from EECs is coordinated in response to the ingested nutrients. EECs are equipped with a wide array of receptors expressed on the luminal side of the gut mucosa, many of which are G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Gribble and Reimann 2016). EEC sensory receptors include: free fatty acids receptors (FFARs) 1, 2, 3, calcium sensing receptors (CaSRs), GPRC6A, GPR92, and taste receptors (TR).

Upon luminal stimulation by their respective nutrient ligand, GPCRs on EECs undergo a conformational change that activates a G protein by promoting the exchange of GDP to GTP associated with the G alpha subunit. The downstream target of the signaling pathway may be enzymes, intracellular receptors, vesicular transport, gene expression or exocytosis (Hucho and Buchner 1997). In response to GPCR activation, several gut hormones from EEC are basolaterally secreted such as Ghrelin, CCK, GLP1, and PYY (Gribble and Reimann 2019).

Many actions of enteroendocrine hormones are involved in promotion of food digestion, food absorption and food intake(Gribble and Reimann 2019). In the gut, following food ingestion, gastrin and histamine promotes the secretion of gastric acid and digestive enzymes (Gribble and Reimann 2019). As food penetrates further down the gut, the release of other hormones including CCK, secretin, GLP1, GLP2 and PYY follows(Wu, Rayner et al. 2013). CCK and secretin stimulate the release of bile acids, digestive enzymes, and bicarbonate into the gut lumen. GLP1 and PYY are important mediators of the ileal brake; a feedback loop that inhibits gastric emptying when nutrients arrive in the distal gut, ensuring that the rate at which food leaves the stomach does not exceed the digestion and absorption capacity of the proximal small intestine (Gribble and Reimann 2019). Enteroendocrine hormones also contribute to the regulation of metabolism and appetite (Gribble and Reimann 2019). Ghrelin and INSL5 are orexigenic hormones that promote food intake (Gribble and Reimann 2019). CCK, oxyntomodulin, GLP1 and PYY act as satiety signals (Degen, Oesch et al. 2005). GLP1 and GIP also act as incretin hormones that enhance insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells (Gribble and Reimann 2019).

3. Gut hormones and their role in obesity and T2DM

3.1. Ghrelin

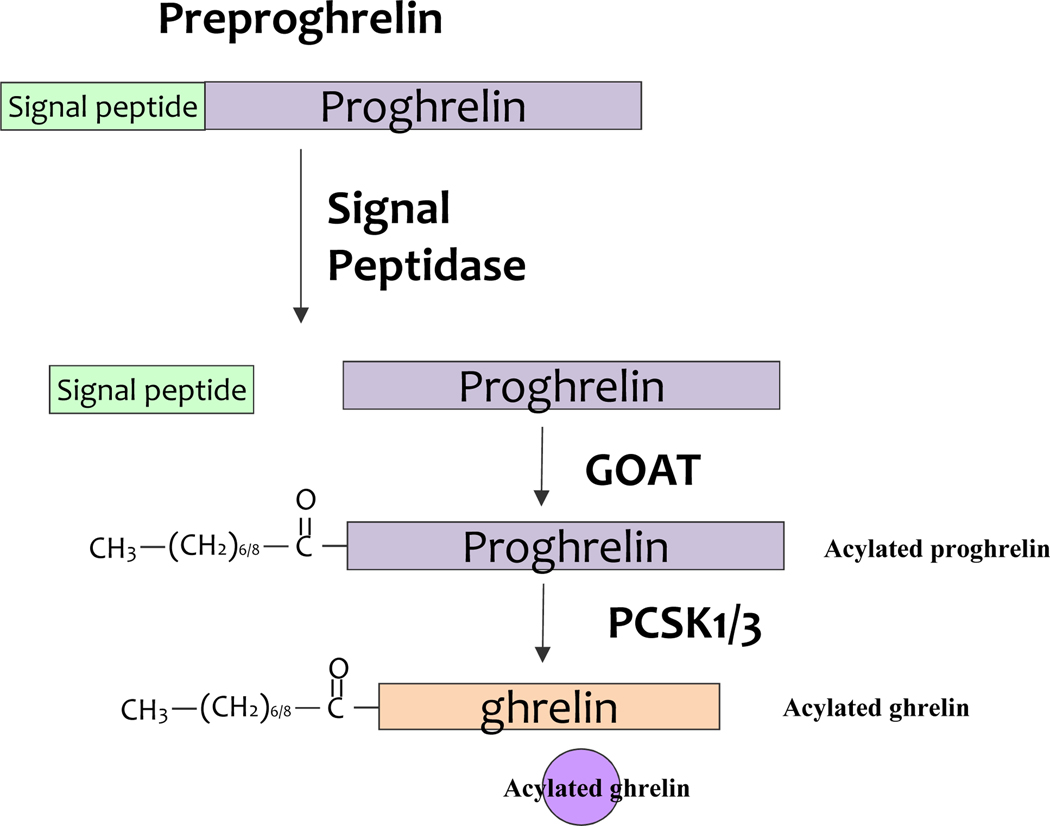

Ghrelin is produced by closed type EECs in the oxyntic gland of the gastric fundus. Ghrelin originates from the preproghrelin polypeptide (Fig3). Plasma ghrelin increases before a meal and decreases in the postprandial period (Sedlackova, Dostalova et al. 2008). Ghrelin stimulates food intake, increases gastric emptying, suppresses insulin secretion, and stimulates counter regulatory hormones (Poher, Tschop et al. 2018)(Table 2).

Figure 3.

Processing of preproghrelin peptide. The human Ghreline gene encodes a precursor protein, preproghrelin. The signal peptidase cleaves the 23 amino acids signal sequence present in the preproghrelin precursor and release proghrelin peptide. Subsequently, ghrelin O acyl transferase (GOAT) mediates acylation of pro-ghrelin. The acylated pro ghrelin precursor is processed by the prohormone convertase PC1/3 (PCSK1/3). Finally, the mature ghrelin is packaged into vesicles, and eventually released in the blood. GOAT, ghrelin O acyl transferase; PCSK1/3, prohormone convertase 1/3

Table 2.

Enteroendocrine hormones and Receptors Involved in the Gastrointestinal Functions, Satiation, Appetite, and Glycemic control.

| Hormone/Receptor | Predominant site of synthesis | Main function | Secretion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghrelin/ GHSR1 | Stomach | ○ Stimulates food intake via secretion of NPY and agouti related protein ○ Increases gastric emptying ○ Suppresses insulin secretion ○ Stimulates gastric acids ○ Stimulates counter regulatory hormones |

Secretion is inhibited by: High serum glucose High serum Insulin CCK GLP1 Plasma lactate Long chain fatty acids (LCFA) |

(Pekic, Pesko et al. 2006, Brennan, Otto et al. 2007, Camilleri 2015 Hazell,Islam et al. 2016 Poher, Tschop et al. 2018) |

|

Cholecystokinin/ CCKR1 CCKR2 |

Duodenum | ○ Induces satiation ○ Inhibits gastric secretion ○ Promotes gallbladder contraction |

Free fatty acids Aminoacids/Oligopeptides | (Dockray 2012, Mishra, Dubey et al. 2016, Steinert, Feinle- Bisset et al. 2017) |

| Glucagon Like Peptide 1/ GLP1R | Distal small intestine, colon | ○ Decreases gastric emptying ○ Decreases the rate of nutrient absorption ○ Stimulates insulin secretion ○ Reduces postprandial glycemia ○ Enhances satiety. |

Carbohydrates Lipids Proteins | (Camilleri 2015, Lutz and Osto 2016) |

| Peptide YY/ Y1R, Y2R, Y4R, and Y5R | Distal small intestine, colon insulin release ○ Decreases GE and GI motility ○ Reduces gallbladder contraction ○ Inhibits pancreatic and intestinal secretion ○ Enhances satiety |

○ Inhibits glucose stimulated | Lipids | (Batterham, Cohen et al. 2003, Boey, Sainsbury et al. 2007) |

| Insulin like peptide 5/ RXFP4 | Colon | ○ Promotes food intake | (Bathgate, Halls et al. 2013) | |

| Oxyntomodulin/ GCGR | Ileum | ○ Decreases food intake ○ inhibits gastric acid secretion and GE |

(Cohen, Ellis et al. 2003, Pocai 2014) |

Mechanisms underlying ghrelin secretion during the fasting state is not fully understood. However, the mechanism of postprandial ghrelin inhibition has been extensively investigated. Ghrelin secreting cells express nutrient sensing receptors predominantly on the basolateral surface; which can be stimulated by nutrients entering the lamina propia from circulation (Gribble and Reimann 2016). Plasma ghrelin levels are reduced after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) due to high serum glucose and insulin levels(Pekic, Pesko et al. 2006). Additionally, CCK, GLP1, long chain fatty acids (LCFA), and lactate reduce plasma ghrelin concentration in human and mice (Hazell, Islam et al. 2016).

In obesity and insulin resistance, the increased amount of basal blood insulin causes an inhibitory effect on ghrelin secretion (Gagnon and Anini 2012); explaining decreased fasting plasma ghrelin in obesity. Although many studies have correlated low plasma ghrelin levels with elevated insulin in individuals with obesity (Sato, Ida et al. 2014), the specific cellular mechanism regulating ghrelin secretion through insulin remain unknown. Gagnon et al. developed a study using cultured gastric cells to examine the mechanism of ghrelin secretion (Gagnon and Anini 2012). They found that ghrelin secreting cells expressed insulin receptors, and that under euglycemia conditions, ghrelin secretion decreased after insulin treatment at both physiological and high doses with no changes in proghrelin gene expression (Gagnon and Anini 2012). It is probable that the mechanism mediating insulin induced ghrelin suppression involves the insulin signaling pathway. Additionally, they examined the ghrelin level in an insulin resistance model; finding that the highest insulin levels lack an inhibitory effect on ghrelin secretion (Gagnon and Anini 2012). They also observed reduced insulin receptor expression and loss of AKT phosphorylation, supporting that ghrelin secreting cell might become insulin resistant after high and continuous exposure to insulin (Gagnon and Anini 2012). However, the results of this study should be carefully interpreted since the authors did not consider other conditions that coexist with high insulin levels and insulin resistance such as elevated leptin, adiponectin, and pro inflammatory cytokines (Gagnon and Anini 2012).

In addition to insulin, glucose exerts a regulatory effect on ghrelin release. Sakata et al. evaluated the changes in ghrelin secretion after exposure to different glucose concentrations in isolated ghrelin secreting cells from rats (Sakata, Park et al. 2012). They showed that concentrations of D glucose of 10 mM (180 mg/dl) reduced the amount of acyl ghrelin release; whereas, D glucose levels of 1 mM (18 mg/dl), enhanced the acyl ghrelin levels.

Ghrelin has a direct effect on food intake and energy expenditure regulation; chronic central infusion of ghrelin in rats resulted in a significant increase in food consumption and body weight (Kamegai, Tamura et al. 2001). In contrast, ghrelin knockout mice exhibited higher energy expenditure and heat production than wild type (De Smet, Depoortere et al. 2006). A similar finding was observed after intravenous ghrelin administration in healthy human volunteers; ghrelin infusion increased the caloric consumption during a buffet meal, and raised the hunger scores before a meal, compared with intravenous saline solution infusion (Wren, Seal et al. 2001). Additionally, low caloric diet and weight loss led to significant increase in the baseline levels of ghrelin. After 10 weeks of hypocaloric diet, the baseline circulating levels of ghrelin increased, and remained elevated after 62 weeks of diet induced weight loss (Sumithran, Prendergast et al. 2011). Since ghrelin positively regulates food intake and body weight, targeting different signaling pathways of this hormone may induce weight loss. Several ghrelin O acyl transferase inhibitors and ghrelin receptor antagonists have been identified; however, their effects on body weight in humans have yet to be established (Schalla and Stengel 2019).

In summary, ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone that stimulates food intake, hunger sensation and decreases energy expenditure, ultimately promoting weight gain. The available evidence suggests that obesity is associated with many metabolic alterations, such as high levels of glucose and insulin. Glucose and insulin levels are negatively correlated with ghrelin secretion. With current evidence it can be concluded that under conditions of euglycemia, a negative correlation exists between these ghrelin and insulin. However, under insulin resistance’s condition insulin lacks of inhibitory effect on ghreline. Some studies have shown that antagonizing the ghrelin system can reduce body weight, but more studies are required to determine its effect in the long term.

3.2. Cholecystokinin

CCK is secreted by open type I cells, with direct contact with nutrients from the intestinal lumen. In humans, the highest density of these cells is found in the duodenum and ileum (Steinert, Feinle-Bisset et al. 2017). CCK cells sense free fatty acids and aminoacids by FFAR1, FFAR4, CD36 (fatty acid transporter), CASR, LPAR5, TAS1R1/TAS1R3 (Steinert, Feinle-Bisset et al. 2017) (Table 2).

The role of CCK in obesity is controversial. Some studies have shown that subjects with obesity have delayed and reduced CCK response after consuming high fat foods (Stewart, Seimon et al. 2011). There is also evidence showing that CCK response after high fat meals is elevated in patients with obesity compared to lean patients (French, Murray et al. 1993). And other studies did not find differences between CCK response in lean and individuals with obesity (Brennan, Luscombe-Marsh et al. 2012). The discrepancy between these findings may be explained by differences in meal composition, dissimilarities in sample characteristics among studies, and study duration.

It was first recognized over 30 years ago that CCK plays an important role in satiation and food intake. Infusion of exogenous CCK in healthy volunteers and participants with obesity decreased food intake, and this effect was inhibited by CCK antagonist (Pi-Sunyer, Kissileff et al. 1982). After food entry into the small intestine, CCK is released into the blood. CCK activates vagal afferents fiber and transmits signals to the NTS, which promotes satiation and gastric distention (van de Wall, Duffy et al. 2005). Moreover, in the hypothalamus CCK may inhibit the ghrelin induced effect on food intake, and decrease the expression of the orexigenic peptide, orexine A and B. With this evidence it is speculated that one of the mechanisms by which CCK suppresses hunger is by downregulating hormones involved in initiation of feeding in the hypothalamus (van de Wall, Duffy et al. 2005).

CCK genes are among the most highly up regulated in pancreatic beta cells of obese mice (Dreja, Jovanovic et al. 2010), suggesting a potential effect of CCK in insulin secretion in obesity. Lavine et al. found that CCK genes are up regulated in pancreatic islets from obese mice (Lavine, Raess et al. 2010). Additionally, CCK knockout obese mouse models showed reduced beta cell mass, decreased plasma fasting insulin concentration, and increased fasting plasma glucose. In the same study, CCK treatment reduced islet cell death in a dose dependent manner (Lavine, Raess et al. 2010). These results suggest that increased CCK expression in pancreatic islets is an adaptive mechanism in obesity that may prevent a diabetogenic phenotype by expanding beta cell mass and increasing beta cell survival. Nevertheless, the study included a whole body CCK knockout model, which did not allow the authors to demonstrate the direct effect of CCK from the EECs in the small intestine, as a unique mediator increasing beta cell survival (Lavine, Raess et al. 2010).

The regulation of CCK gene expression in beta cell and I cells mainly occurs through cAMP, and the transcription factor CREB (Hansen 2001). As GLP1 also stimulates cAMP production (Linnemann, Neuman et al. 2015), and the GLP1 receptor has been found in beta cells; it was proposed that GLP1 might regulate islets CCK production (Linnemann, Neuman et al. 2015). In many studies, after GLP1 exposure, beta cell cultures from obese mice increased CCK expression, and high levels of CCK ameliorated beta cell apoptosis (Linnemann, Neuman et al. 2015).

Thus, the previous evidences allows for the interpretation that CCK in obesity may be involved in satiation, regulation of glucose homeostasis throughout increasing beta cell mass, and increasing fasting insulin concentration.

3.3. Glucagon like Peptide 1

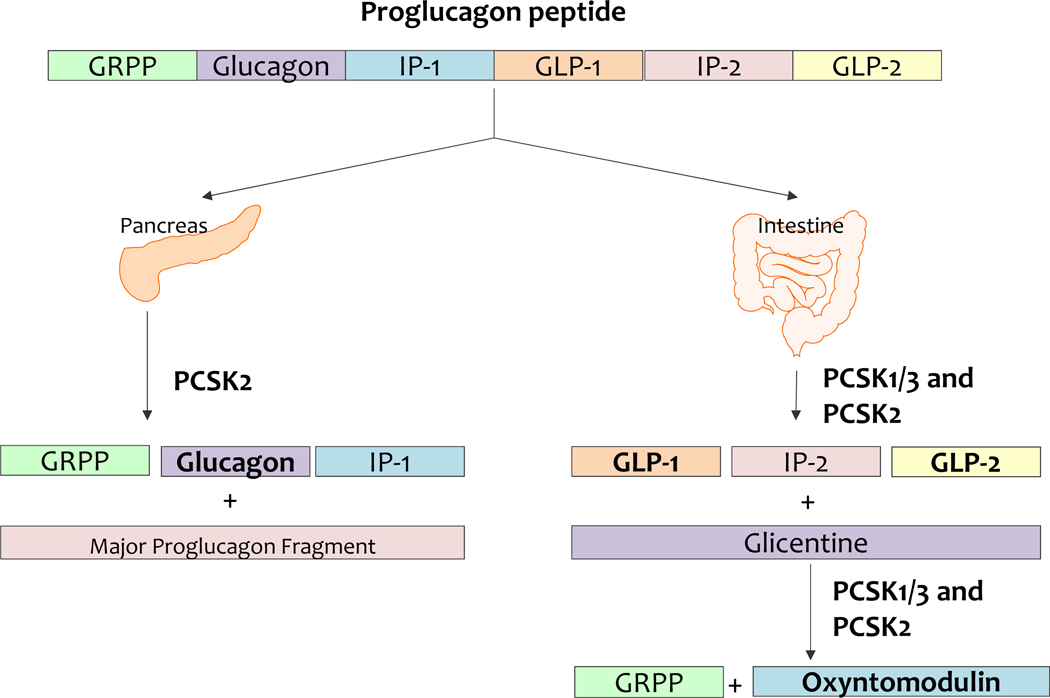

GLP1 is secreted by L cells, an open type EEC located in the small and large intestine. The GLP1 protein is code by the proglucagon gene (Baggio and Drucker 2007) (Fig4). L cells also secrete PYY, CCK, neurotensin, and secretin. GLP1 secretion is stimulated by carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Tissue selective processing of proglucagon peptide. PCSK1/3, prohormone convertase 1/3; PCSK2, prohormone convertase 2; GRPP, glicentin related polypeptide; IP 1, intervening peptide 1; IP 2, intervening peptide 2; GLP1, glucagon like peptide 1; GLP 2, glucagon like peptide 2

GLP1 receptors are widely distributed in the brain, GI tract, and several other organs, such as the pancreas. GLP1 is implicated in the control of food intake and energy balance, as it slows gastric emptying, decreases the rate of nutrient absorption, reduces postprandial glycemia, and enhances satiety. GLP1 and GIP are both incretins, that is, they stimulate insulin secretion after glucose absorption and inhibit glucagon release(Holst 2007). Beyond improving glycemic control and weight loss, GLP1 receptor agonists exert other effects. GLP1 receptor agonists have been associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death compared with treatment using other glucose lowering therapies (Best, Hoogwerf et al. 2011). Moreover, GLP1 receptor agonists have shown a role in atherosclerotic prevention, blood pressure reduction, neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease, and improvement of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The broad location of GLP1 receptors throughout our body may mediate multiples physiological effects, beyond glycemic control and weight loss(Ryan and Acosta 2015).

The relationship between GLP1 and obesity is inconclusive and remains controversial in regards to underlying pathophysiology, disease maintenance, and therapeutic potential. However key studies have suggested that obesity is associated with low fasting GLP1 levels, and decreased postprandial GLP1 response (Ahmed, Huri et al. 2017). A study conducted by Ahmed et al. also found that obesity is associated with high serum levels of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4)(Ahmed, Huri et al. 2017). Other studies have proposed that accumulation of visceral adiposity may contribute to the higher concentration of DPP4 found in subjects with obesity (Nistala and Savin 2017). Therefore, low levels of GLP1 may be partially explained by an increase in the catalytic degradation of GLP1 by DPP4.

Despite previous evidence, some discrepancies exist between reports of GLP1 levels in patients with obesity, according to their glucose metabolic profile. Manell et al. found that fasting GLP1 levels were lower among patients with obesity and glucose intolerance/ T2DM compared to subjects with obesity and euglycemia(Manell, Staaf et al. 2016). After an OGTT, the total postprandial GLP1 tended to be lower in individuals with obesity. However, a more significant reduction in GLP1 levels was observed in patients with obesity and poor glycemic control, with a 50% reduction in the GLP1 postprandial levels in the diabetic group compared to the normoglycemic group. On the other hand, fasting GLP1 levels (Manell, Staaf et al. 2016) and post prandial GLP1 peaks in patients with normoglycemic and obesity were higher in comparison to lean patients (Acosta, Camilleri et al. 2015). These controversial findings may be due to the type of GLP1 which was measured in each study, the method for measuring, the type of meal provided prior to blood collection and the type of patients. Clearly, more studies are needed to understand whether a deficiency of GLP1 exists in obesity and diabetes.

As previously mentioned, obesity has long been associated with various gastrointestinal abnormalities such as decreased satiation, accelerated GE, and larger fasting gastric volume (Acosta, Camilleri et al. 2015). GLP1 receptor agonists are effective in improving satiation, decreasing gastric emptying, and body weight (Halawi, Khemani et al. 2017); and this class of medication was approved by the FDA for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. There are seven available GLP1 analogs for the treatment of diabetes, exenatide, liraglutide, exenatide LAR, albiglutide, dulaglutide, and lixisenatide, which have showed an HbA1c reduction of −0.55% compared with placebo (Htike, Zaccardi et al. 2017). Liraglutide was approved in the US in 2014 for weight management. In a large multicenter trial, administration of liraglutide resulted in an average weight loss of 8% after 6 months of treatment; notably, weight loss of more than 10% was observed in 33% of the participants, and more than 15% of body weight in 14% of the participants (Pi-Sunyer, Astrup et al. 2015). Effects of liraglutide on weight loss have been associated with delay in gastric emptying of solids at 5 and 16 weeks(Halawi, Khemani et al. 2017), reduced maximal tolerated volume, desire to eat, and increased perception of fullness(Kadouh, Chedid et al. 2020).

In conclusion, obesity has been associated with low fasting GLP1 levels and a decreased postprandial GLP1 response, especially under conditions of dysregulated glycemic control. In contrast, obesity with normal glycemic control is associated with increased GLP1 expression and secretion as a compensatory mechanism to prevent the progression to T2DM. GLP1 analogs have shown effectiveness in T2DM and obesity treatment. Furthermore, their benefits have extended beyond blood glucose control, and body weight regulation, to almost every organ system.

3.4. Peptide YY

Peptide YY, is synthesized by L type EECs. The active form of PYY, PYY (3–36), results from the cleavage of PYY (1–36) by the enzyme DPP4. PYY has wide range of functions, including inhibition of glucose stimulated insulin release, decreased GE and GI motility, reduction of gallbladder contraction, and suppression of pancreatic and intestinal secretion (Boey, Sainsbury et al. 2007). The most potent stimuli for secretion of PYY are lipids; a lipid rich meal results in significant and more sustained elevation in PYY than glucose and proteins (Steinert, Feinle-Bisset et al. 2017) (Table 2).

The relationship between PYY and obesity is inconclusive, as some studies have shown decreased fasting (Batterham, Cohen et al. 2003) and postprandial PYY levels in patients with obesity (Acosta, Camilleri et al. 2015). In subjects with obesity and without diabetes, fasting and postprandial PYY concentrations were lower after weight loss secondary to dietary restriction, compared with baseline and these observations persisted for 12 months after bodyweight reduction (Sumithran, Prendergast et al. 2011). The role of PYY on weight regulation has been studied on the basis of food intake. Vrang et al. demonstrated in mouse models of diet induced obesity that chronic administration of PYY decreases body weight and food intake, and improves insulin sensitivity. However, the anorexigenic effect of PYY was blunted after four days of treatment (Vrang, Madsen et al. 2006). In contrast, Batterham et al. found that after PYY infusion in humans with obesity, the cumulative 24 hour food intake was reduced (Batterham, Cohen et al. 2003). Food intake discrepancies between these studies may be explained by intrinsic differences of PYY response between mice and humans, the duration of PYY treatment, and the method used for PYY administration, as it affects the blood PYY concentration. Furthermore, these results have been difficult to replicate in various clinical studies due to the poor tolerance and high incidence of nausea and vomiting after PYY administration (Gantz, Erondu et al. 2007).

As previously stated, there is discrepancy among evidence regarding the relationship between PYY and obesity. In response to the multitude of contradictory studies, Fernandez et al. conducted a study with subjects with morbid obesity and different glycemic statuses (Fernandez-Garcia, Murri et al. 2014). After stratification according to insulin resistance and glycemic control, they found that in similar degrees of obesity, fasting PYY levels were not influenced by insulin resistance, glucose intolerance or diabetes. However, after food intake, they found a significant increase in PYY levels in patients with obesity, normal glucose and low insulin resistance. An absent postprandial response was observed in patients with obesity, and high insulin resistance, glucose intolerance or diabetes. These findings suggest that insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and diabetes may impair the postprandial PYY response in patients with obesity (Fernandez-Garcia, Murri et al. 2014).

In an investigation into the role of PYY in T2DM, Boey et al. found that fasting PYY levels were negatively correlated with fasting insulin secretion and HOMA B. These data suggest that low circulating levels of PYY are linked with insulin resistance (Boey, Heilbronn et al. 2006). Another study showed that chronic PYY administration in insulin resistant mice increased fat oxidation and enhanced the ability of insulin to promote glucose uptake, indicating that PYY administration improves insulin sensitivity (van den Hoek, Heijboer et al. 2007).

In summary, PYY has a key role in food intake regulation and low levels may be associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM; insulin sensitivity improves after PYY administration. PYY also has effects on weight regulation, through suppression of caloric consumption and increased fat oxidation. Nevertheless, the evidence is still contradictory and more studies are needed.

3.5. Insulin like peptide 5

Insulin like peptide 5 (INSL5) is a peptide hormone product of colonic L cells, and a member of the relaxin/insulin family. In the gut, INSL5 has been found to be expressed in EECs and co released in the same vesicles as GLP1 and PYY (Billing, Smith et al. 2018). Although some members of the relaxin family have important roles in reproductive physiology and remodeling of connective tissue (Wagner, Flehmig et al. 2016), the specific function of INSL5 remains unclear (Table 2).

INSL5 has been reported to act through the relaxin/insulin like family peptide receptor 4 (RXFP4). RXFP4, is a GPCR with inhibitory adenylyl cyclase activity and is expressed along the GI tract. RXFP4 has also demonstrated stimulation of <di> concentration, suggesting that RXFP4 can couple with additional G proteins (Bathgate, Halls et al. 2013). RXFP4 has been linked to appetite regulation; a dual RXFP4 and RXFP3 agonist elicited an increase in food intake after and intracerebroventricular administration in rats, and this increase was still observed at 4 and 24 hours post administration (DeChristopher, Park et al. 2019). In a similar study, INSL5 showed an orexigenic role (Grosse, Heffron et al. 2014). Johannes Grosse et al. found that INSL5 plasma levels and colonic mRNA transcripts were elevated by caloric restriction, and circulating INSL5 concentrations were suppressed by refeeding. Knockout of the receptor RXFP4 or treatment with antibodies against endogenous INSL5 correspondingly reduced refeeding responses after fasting (Grosse, Heffron et al. 2014). These results support the notion that INSL5 is an orexigenic hormone that plays a physiological role in driving food intake under conditions of energy restriction. On the other hand, Ying Shiuan Lee et al found no effect on food intake in INSL5 deficient mice(Lee, De Vadder et al. 2016). This last finding should be interpreted carefully because the chronic deficiency of INSL5 might be compensating by elevation of other orexigenic hormones, hiding the effect of INSL5 in food intake.

The effect of INSL5 on glucose homeostasis is less clear. Burnicka-Turek et al demonstrated that, INSL5 knockout (Insl5−/−) mice displayed impaired glucose homeostasis. Glucose levels were significantly higher in Insl5−/− mice at an advanced age after glucose tolerance test. The increased blood glucose was due to glucose intolerance resulting from reduced insulin secretion, reduced average islets area and β cell numbers(Burnicka-Turek, Mohamed et al. 2012). Some evidence suggests that INSL5 mediates insulin secretion in parallel via two pathways: directly through RXFP4 in pancreatic β cells and indirectly by promoting GLP1 secretion(Luo, Li et al. 2015). Beta cell models using MIN6 cells increased insulin secretion in conditions of high glucose exposure and INSL5 stimuli. Additionally, after treating an L type cell model with INSL5 in a glucose containing medium, the GLP1 contents in the supernatant were significantly increased from the basal level, in a dose dependant manner. These observations suggest an insulinotrophic effect of INSL5(Luo, Li et al. 2015).

In agreement with the report from Burnicka Turek et al, INSL5 deficient mice in the Ying Shiuan Lee et al study showed impaired tolerance to glucose administration intraperitoneally (Lee, De Vadder et al. 2016). According to these previous findings, men with obesity and T2DM showed lower levels of serum INSL5 compared to men without obesity and diabetes(Wagner, Flehmig et al. 2016).

3.6. Oxyntomodulin

Oxyntomodulin (OXM) is a 37 amino acid peptide hormone secreted from enteroendocrine L cell. OXM is a specific product of the intestinal proglucagon process (Fig4). Luminal nutrients including carbohydrates, lipids, and protein will stimulate OXM secretion (Pocai 2014)(Table 2).

Although an endogenous OXM receptor has not been identified, this hormone exerts weak agonist activity on glucagon receptors (GCGR), meaning that OXM may affect insulin secretion via the GCGR expressed by beta cells, as well as acting on the hepatocytes where it may lead to glucose production. OXM also interacts with the GLP1 receptor, therefore, it may also stimulate insulin secretion(Pocai 2014).

Some studies have shown that exogenous administration of OXM can reduce body weight in humans. The effect of OXM in weight lost arises from its ability to both reduce food intake and increase energy expenditure (Cohen, Ellis et al. 2003). The anorexigenic effect of OXM is mediated centrally via GLP1 receptor activation (Baggio, Huang et al. 2004). However, the mechanism by which it increases energy expenditure remains controversial, and both glucagon, and GLP1 receptor activation has been implicated. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that the glucagon receptor is the principal mediator underlying increased energy consumption (Scott, Minnion et al. 2018).

Scott et al. demonstrated that subcutaneous administration of analogous OXM increased energy expenditure, however, when the glucagon receptor was blocked; there was no increase in energy expenditure (Scott, Minnion et al. 2018). Therefore, the dual agonist effect of OXM on GLP1 and glucagon receptors makes it an ideal therapeutic target for obesity (Cegla, Troke et al. 2014). The overall actions of OXM on glucose metabolism are less clear, since the actions on hepatic glucose production and insulin secretion would be expected to have opposing effects; however, glucose tolerance in mice was reported to be improved rather than inhibited by OXM administration, directly by stimulating insulin secretion (Maida, Lovshin et al. 2008). Moreover, OXM significantly reduces apoptosis in murine beta cells after streptozotocin administration and decreases apoptosis in thapsigargin treated INS 1 cells (Maida, Lovshin et al. 2008). Similar results were found in humans, where infusion of OXM in subjects with obesity and with or without T2DM showed that OXM acutely improved glucose homeostasis in a graded glucose infusion. The principal mechanism was thought to be through the increase of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity (Shankar, Shankar et al. 2018). These findings may lessen previously held concerns about the dual agonism of OXM on both GLP1R and GCGR leading to deterioration of glucose tolerance in those at risk for T2DM.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this review highlighted the regulation of enteroendocrine hormones in obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM. A large number of studies have emerged about the role of GLP1, PYY, ghrelin, CCK, INSL5, glucagon, and OXM under conditions of excess adipose tissue and hyperglycemia. The available evidence allows us to understand that some changes in gut hormone regulation are the result of compensatory mechanisms, and that obesity associated with glucose alterations is linked with more changes in the physiological response of enteroendocrine hormones. Additional research is necessary to address the current controversies around enteroendocrine hormones, obesity, and T2DM.

Highlights.

Enteroendocrine cells are specialized cells capable of sensing luminal content, producing and releasing hormone signaling molecules to modulate a variety of physiological GI functions.

Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone that stimulates food intake, hunger sensation and decreases energy expenditure, ultimately promoting weight gain.

Cholecystokinin in obesity may be involved in satiation and regulation of glucose homeostasis.

Obesity has been associated with low fasting GLP1 levels and a decreased postprandial GLP1 response, especially under conditions of dysregulated glycemic control.

PYY has a key role in food intake regulation and low levels may be associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Megan Schaefer for critical review of this manuscript.

Funding support: Dr. Acosta is supported by NIH (NIH K23-DK114460, C-Sig P30DK84567), ANMS Career Development Award, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine – Gerstner Career Development Award, and the Magnus Trust.

Abbreviations:

- 5HT

5 Hydroxytryptamine

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CaSRs

calcium sensing receptors

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DPP4

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- EECs

Enteroendocrine cells

- FFARs

free fatty acids receptors

- GCGR

glucagon receptors

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GIP

gastric inhibitory polypeptide

- GLP1

glucagon like peptide 1

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptors

- INSL5

insulin like peptide 5

- IP3

inositol triphosphate

- LCFA

long chain fatty acids

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- OXM

oxyntomodulin

- PC1/3

prohormone convertase 1/3

- PC2

prohormone convertase 2

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3 kinases

- PKB

Protein kinase B

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PYY

peptide YY

- RXFP4

relaxin/insulin like family peptide receptor 4

- SCFAs

short chain fatty acids

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TR

taste receptors

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Acosta is a stockholder in Gila Therapeutics, and Phenomix Sciences; he serves as a consultant for Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, General Mills.

Maria Laura Ricardo-Silgado and Alison McRae declare no conflict of interest

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acosta A, Camilleri M, Shin A, Vazquez-Roque MI, Iturrino J, Burton D, O’Neill J, Eckert D. and Zinsmeister AR (2015). “Quantitative gastrointestinal and psychological traits associated with obesity and response to weight-loss therapy.” Gastroenterology 148(3): 537–546 e534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta A, Camilleri M, Shin A, Vazquez-Roque MI, Iturrino J, Burton D, O’Neill J, Eckert D. and Zinsmeister AR (2015). “Quantitative Gastrointestinal and Psychological Traits Associated With Obesity and Response to Weight-Loss Therapy.” Gastroenterology 148(3): 537–5460000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed RH, Huri HZ, Muniandy S, Al-Hamodi Z, Al-Absi B, Alsalahi A. and Razif MF (2017). “Altered circulating concentrations of active glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) in obese subjects and their association with insulin resistance.” Clin Biochem 50(13–14): 746–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio LL and Drucker DJ (2007). “Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP.” Gastroenterology 132(6): 2131–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio LL, Huang Q, Brown TJ and Drucker DJ (2004). “Oxyntomodulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 differentially regulate murine food intake and energy expenditure.” Gastroenterology 127(2): 546–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate RA, Halls ML, van der Westhuizen ET, Callander GE, Kocan M. and Summers RJ (2013). “Relaxin family peptides and their receptors.” Physiol Rev 93(1): 405–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham RL, Cohen MA, Ellis SM, Le Roux CW, Withers DJ, Frost GS, Ghatei MA and Bloom SR (2003). “Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3–36.” N Engl J Med 349(10): 941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JH, Hoogwerf BJ, Herman WH, Pelletier EM, Smith DB, Wenten M. and Hussein MA (2011). “Risk of cardiovascular disease events in patients with type 2 diabetes prescribed the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist exenatide twice daily or other glucose-lowering therapies: a retrospective analysis of the LifeLink database.” Diabetes Care 34(1): 90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billing LJ, Smith CA, Larraufie P, Goldspink DA, Galvin S, Kay RG, Howe JD, Walker R, Pruna M, Glass L, Pais R, Gribble FM and Reimann F. (2018). “Co-storage and release of insulin-like peptide-5, glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptideYY from murine and human colonic enteroendocrine cells.” Mol Metab 16: 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boey D, Heilbronn L, Sainsbury A, Laybutt R, Kriketos A, Herzog H. and Campbell LV (2006). “Low serum PYY is linked to insulin resistance in first-degree relatives of subjects with type 2 diabetes.” Neuropeptides 40(5): 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boey D, Sainsbury A. and Herzog H. (2007). “The role of peptide YY in regulating glucose homeostasis.” Peptides 28(2): 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan IM, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Seimon RV, Otto B, Horowitz M, Wishart JM and Feinle-Bisset C. (2012). “Effects of fat, protein, and carbohydrate and protein load on appetite, plasma cholecystokinin, peptide YY, and ghrelin, and energy intake in lean and obese men.” Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303(1): G129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan IM, Otto B, Feltrin KL, Meyer JH, Horowitz M. and Feinle-Bisset C. (2007). “Intravenous CCK-8, but not GLP-1, suppresses ghrelin and stimulates PYY release in healthy men.” Peptides 28(3): 607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnicka-Turek O, Mohamed BA, Shirneshan K, Thanasupawat T, Hombach-Klonisch S, Klonisch T. and Adham IM (2012). “INSL5-deficient mice display an alteration in glucose homeostasis and an impaired fertility.” Endocrinology 153(10): 4655–4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M. (2015). “Peripheral mechanisms in appetite regulation.” Gastroenterology 148(6): 1219–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cegla J, Troke RC, Jones B, Tharakan G, Kenkre J, McCullough KA, Lim CT, Parvizi N, Hussein M, Chambers ES, Minnion J, Cuenco J, Ghatei MA, Meeran K, Tan TM and Bloom SR (2014). “Coinfusion of low-dose GLP-1 and glucagon in man results in a reduction in food intake.” Diabetes 63(11): 3711–3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Ellis SM, Le Roux CW, Batterham RL, Park A, Patterson M, Frost GS, Ghatei MA and Bloom SR (2003). “Oxyntomodulin suppresses appetite and reduces food intake in humans.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(10): 4696–4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet B, Depoortere I, Moechars D, Swennen Q, Moreaux B, Cryns K, Tack J, Buyse J, Coulie B. and Peeters TL (2006). “Energy homeostasis and gastric emptying in ghrelin knockout mice.” J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316(1): 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChristopher B, Park SH, Vong L, Bamford D, Cho HH, Duvadie R, Fedolak A, Hogan C, Honda T, Pandey P, Rozhitskaya O, Su L, Tomlinson E. and Wallace I. (2019). “Discovery of a small molecule RXFP3/4 agonist that increases food intake in rats upon acute central administration.” Bioorg Med Chem Lett 29(8): 991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen L, Oesch S, Casanova M, Graf S, Ketterer S, Drewe J. and Beglinger C. (2005). “Effect of peptide YY3–36 on food intake in humans.” Gastroenterology 129(5): 1430–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockray GJ (2012). “Cholecystokinin.” Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 19(1): 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreja T, Jovanovic Z, Rasche A, Kluge R, Herwig R, Tung YC, Joost HG, Yeo GS and Al-Hasani H. (2010). “Diet-induced gene expression of isolated pancreatic islets from a polygenic mouse model of the metabolic syndrome.” Diabetologia 53(2): 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelstoft MS, Egerod KL, Lund ML and Schwartz TW (2013). “Enteroendocrine cell types revisited.” Curr Opin Pharmacol 13(6): 912–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Garcia JC, Murri M, Coin-Araguez L, Alcaide J, El Bekay R. and Tinahones FJ (2014). “GLP-1 and peptide YY secretory response after fat load is impaired by insulin resistance, impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes in morbidly obese subjects.” Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 80(5): 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SJ, Murray B, Rumsey RD, Sepple CP and Read NW (1993). “Preliminary studies on the gastrointestinal responses to fatty meals in obese people.” Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 17(5): 295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J. and Anini Y. (2012). “Insulin and norepinephrine regulate ghrelin secretion from a rat primary stomach cell culture.” Endocrinology 153(8): 3646–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I, Erondu N, Mallick M, Musser B, Krishna R, Tanaka WK, Snyder K, Stevens C, Stroh MA, Zhu H, Wagner JA, Macneil DJ, Heymsfield SB and Amatruda JM (2007). “Efficacy and safety of intranasal peptide YY3–36 for weight reduction in obese adults.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(5): 1754–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM and Reimann F. (2016). “Enteroendocrine Cells: Chemosensors in the Intestinal Epithelium.” Annu Rev Physiol 78: 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM and Reimann F. (2019). “Function and mechanisms of enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones in metabolism.” Nat Rev Endocrinol 15(4): 226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse J, Heffron H, Burling K, Akhter Hossain M, Habib AM, Rogers GJ, Richards P, Larder R, Rimmington D, Adriaenssens AA, Parton L, Powell J, Binda M, Colledge WH, Doran J, Toyoda Y, Wade JD, Aparicio S, Carlton MB, Coll AP, Reimann F, O’Rahilly S. and Gribble FM (2014). “Insulin-like peptide 5 is an orexigenic gastrointestinal hormone.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(30): 11133–11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halawi H, Khemani D, Eckert D, O’Neill J, Kadouh H, Grothe K, Clark MM, Burton DD, Vella A, Acosta A, Zinsmeister AR and Camilleri M. (2017). “Effects of liraglutide on weight, satiation, and gastric functions in obesity: a randomised, placebo-controlled pilot trial.” Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2(12): 890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD and Ogden CL (2020). “Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018.” NCHS Data Brief(360): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TV (2001). “Cholecystokinin gene transcription: promoter elements, transcription factors and signaling pathways.” Peptides 22(8): 1201–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell TJ, Islam H, Townsend LK, Schmale MS and Copeland JL (2016). “Effects of exercise intensity on plasma concentrations of appetite-regulating hormones: Potential mechanisms.” Appetite 98: 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymsfield SB and Wadden TA (2017). “Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity.” The New England journal of medicine 376(15): 1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst JJ (2007). “The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1.” Physiol Rev 87(4): 1409–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Htike ZZ, Zaccardi F, Papamargaritis D, Webb DR, Khunti K. and Davies MJ (2017). “Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison analysis.” Diabetes Obes Metab 19(4): 524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho F. and Buchner K. (1997). “Signal transduction and protein kinases: the long way from the plasma membrane into the nucleus.” Naturwissenschaften 84(7): 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouh H, Chedid V, Halawi H, Burton DD, Clark MM, Khemani D, Vella A, Acosta A. and Camilleri M. (2020). “GLP-1 Analog Modulates Appetite, Taste Preference, Gut Hormones, and Regional Body Fat Stores in Adults with Obesity.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamegai J, Tamura H, Shimizu T, Ishii S, Sugihara H. and Wakabayashi I. (2001). “Chronic central infusion of ghrelin increases hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and Agouti-related protein mRNA levels and body weight in rats.” Diabetes 50(11): 2438–2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre R, Sternini C, De Giorgio R. and Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. (2016). “Enteroendocrine cells: a review of their role in brain-gut communication.” Neurogastroenterol Motil 28(5): 620–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine JA, Raess PW, Stapleton DS, Rabaglia ME, Suhonen JI, Schueler KL, Koltes JE, Dawson JA, Yandell BS, Samuelson LC, Beinfeld MC, Davis DB, Hellerstein MK, Keller MP and Attie AD (2010). “Cholecystokinin is up-regulated in obese mouse islets and expands beta-cell mass by increasing beta-cell survival.” Endocrinology 151(8): 3577–3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, De Vadder F, Tremaroli V, Wichmann A, Mithieux G. and Backhed F. (2016). “Insulin-like peptide 5 is a microbially regulated peptide that promotes hepatic glucose production.” Mol Metab 5(4): 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner DR, Fruhbeck G, Yumuk V, Schindler K, Micic D, Woodward E. and Toplak H. (2017). “Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Two Diseases with a Need for Combined Treatment Strategies - EASO Can Lead the Way.” Obes Facts 10(5): 483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann AK, Neuman JC, Battiola TJ, Wisinski JA, Kimple ME and Davis DB (2015). “Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Regulates Cholecystokinin Production in beta-Cells to Protect From Apoptosis.” Mol Endocrinol 29(7): 978–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Li T, Zhu Y, Dai Y, Zhao J, Guo ZY and Wang MW (2015). “The insulinotrophic effect of insulin-like peptide 5 in vitro and in vivo.” Biochem J 466(3): 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz TA and Osto E. (2016). “Glucagon-like peptide-1, glucagon-like peptide-2, and lipid metabolism.” Curr Opin Lipidol 27(3): 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maida A, Lovshin JA, Baggio LL and Drucker DJ (2008). “The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist oxyntomodulin enhances beta-cell function but does not inhibit gastric emptying in mice.” Endocrinology 149(11): 5670–5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manell H, Staaf J, Manukyan L, Kristinsson H, Cen J, Stenlid R, Ciba I, Forslund A. and Bergsten P. (2016). “Altered Plasma Levels of Glucagon, GLP-1 and Glicentin During OGTT in Adolescents With Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101(3): 1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AK, Dubey V. and Ghosh AR (2016). “Obesity: An overview of possible role(s) of gut hormones, lipid sensing and gut microbiota.” Metabolism 65(1): 48–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, Abraham JP, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Achoki T, AlBuhairan FS, Alemu ZA, Alfonso R, Ali MK, Ali R, Guzman NA, Ammar W, Anwari P, Banerjee A, Barquera S, Basu S, Bennett DA, Bhutta Z, Blore J, Cabral N, Nonato IC, Chang JC, Chowdhury R, Courville KJ, Criqui MH, Cundiff DK, Dabhadkar KC, Dandona L, Davis A, Dayama A, Dharmaratne SD, Ding EL, Durrani AM, Esteghamati A, Farzadfar F, Fay DF, Feigin VL, Flaxman A, Forouzanfar MH, Goto A, Green MA, Gupta R, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hankey GJ, Harewood HC, Havmoeller R, Hay S, Hernandez L, Husseini A, Idrisov BT, Ikeda N, Islami F, Jahangir E, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeffreys M, Jonas JB, Kabagambe EK, Khalifa SE, Kengne AP, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Kimokoti RW, Kinge JM, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Kwan G, Lai T, Leinsalu M, Li Y, Liang X, Liu S, Logroscino G, Lotufo PA, Lu Y, Ma J, Mainoo NK, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Mokdad AH, Moschandreas J, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Nand D, Narayan KM, Nelson EL, Neuhouser ML, Nisar MI, Ohkubo T, Oti SO, Pedroza A, Prabhakaran D, Roy N, Sampson U, Seo H, Sepanlou SG, Shibuya K, Shiri R, Shiue I, Singh GM, Singh JA, Skirbekk V, Stapelberg NJ, Sturua L, Sykes BL, Tobias M, Tran BX, Trasande L, Toyoshima H, van de Vijver S, Vasankari TJ, Veerman JL, Velasquez-Melendez G, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wang C, Wang X, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wright JL, Yang YC, Yatsuya H, Yoon J, Yoon SJ, Zhao Y, Zhou M, Zhu S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ and Gakidou E. (2014). “Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.” Lancet 384(9945): 766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistala R. and Savin V. (2017). “Diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease progression: role of DPP4.” Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312(4): F661–F670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekic S, Pesko P, Djurovic M, Miljic D, Doknic M, Glodic J, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF and Popovic V. (2006). “Plasma ghrelin levels of gastrectomized and vagotomized patients are not affected by glucose administration.” Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 64(6): 684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DC, le Roux CW, Violante Ortiz R, Jensen CB, Wilding JP, Obesity S. and Prediabetes NNSG (2015). “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management.” N Engl J Med 373(1): 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer X, Kissileff HR, Thornton J. and Smith GP (1982). “C-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin decreases food intake in obese men.” Physiol Behav 29(4): 627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocai A. (2014). “Action and therapeutic potential of oxyntomodulin.” Mol Metab 3(3): 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poher AL, Tschop MH and Muller TD (2018). “Ghrelin regulation of glucose metabolism.” Peptides 100: 236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D. and Acosta A. (2015). “GLP-1 receptor agonists: Nonglycemic clinical effects in weight loss and beyond.” Obesity (Silver Spring) 23(6): 1119–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata I, Park WM, Walker AK, Piper PK, Chuang JC, Osborne-Lawrence S. and Zigman JM (2012). “Glucose-mediated control of ghrelin release from primary cultures of gastric mucosal cells.” Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302(10): E1300–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Ida T, Nakamura Y, Shiimura Y, Kangawa K. and Kojima M. (2014). “Physiological roles of ghrelin on obesity.” Obes Res Clin Pract 8(5): e405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalla MA and Stengel A. (2019). “Pharmacological Modulation of Ghrelin to Induce Weight Loss: Successes and Challenges.” Curr Diab Rep 19(10): 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R, Minnion J, Tan T. and Bloom SR (2018). “Oxyntomodulin analogue increases energy expenditure via the glucagon receptor.” Peptides 104: 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlackova D, Dostalova I, Hainer V, Beranova L, Kvasnickova H, Hill M, Haluzik M. and Nedvidkova J. (2008). “Simultaneous decrease of plasma obestatin and ghrelin levels after a high-carbohydrate breakfast in healthy women.” Physiol Res 57 Suppl 1: S29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar SS, Shankar RR, Mixson LA, Miller DL, Pramanik B, O’Dowd AK, Williams DM, Frederick CB, Beals CR, Stoch SA, Steinberg HO and Kelley DE (2018). “Native Oxyntomodulin Has Significant Glucoregulatory Effects Independent of Weight Loss in Obese Humans With and Without Type 2 Diabetes.” Diabetes 67(6): 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert RE, Feinle-Bisset C, Asarian L, Horowitz M, Beglinger C. and Geary N. (2017). “Ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, and PYY(3–36): Secretory Controls and Physiological Roles in Eating and Glycemia in Health, Obesity, and After RYGB.” Physiol Rev 97(1): 411–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JE, Seimon RV, Otto B, Keast RS, Clifton PM and Feinle-Bisset C. (2011). “Marked differences in gustatory and gastrointestinal sensitivity to oleic acid between lean and obese men.” Am J Clin Nutr 93(4): 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A. and Proietto J. (2011). “Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss.” The New England journal of medicine 365(17): 1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A. and Proietto J. (2011). “Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss.” N Engl J Med 365(17): 1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triplitt C, Solis-Herrera C, Cersosimo E, Abdul-Ghani M. and Defronzo RA (2015). “Empagliflozin and linagliptin combination therapy for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.” Expert Opin Pharmacother 16(18): 2819–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wall EH, Duffy P. and Ritter RC (2005). “CCK enhances response to gastric distension by acting on capsaicin-insensitive vagal afferents.” Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289(3): R695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoek AM, Heijboer AC, Voshol PJ, Havekes LM, Romijn JA, Corssmit EP and Pijl H. (2007). “Chronic PYY3–36 treatment promotes fat oxidation and ameliorates insulin resistance in C57BL6 mice.” Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292(1): E238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrang N, Madsen AN, Tang-Christensen M, Hansen G. and Larsen PJ (2006). “PYY(3–36) reduces food intake and body weight and improves insulin sensitivity in rodent models of diet-induced obesity.” Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291(2): R367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner IV, Flehmig G, Scheuermann K, Loffler D, Korner A, Kiess W, Stumvoll M, Dietrich A, Bluher M, Kloting N, Soder O. and Svechnikov K. (2016). “Insulin-Like Peptide 5 Interacts with Sex Hormones and Metabolic Parameters in a Gender and Adiposity Dependent Manner in Humans.” Horm Metab Res 48(9): 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, Brynes AE, Frost GS, Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Ghatei MA and Bloom SR (2001). “Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86(12): 5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Rayner CK, Young RL and Horowitz M. (2013). “Gut motility and enteroendocrine secretion.” Curr Opin Pharmacol 13(6): 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]