Abstract

Background: Several studies assessed the level of knowledge and general public behavior on human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) in India. However, comprehensive scrutiny of literature is essential for any decision-making process. Our objective was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the level of knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS in India.

Methods: A systematic search using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free terms was conducted in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar databases to investigate the level of knowledge and attitude of HIV/AIDS in India population. Cross-sectional studies published in English from January 2010 to November 2020 were included. The identified articles were screened in multiple levels of title, abstract and full-text and final studies that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved and included in the study. The methodological quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s checklist for cross-sectional studies. Estimates with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each domain were pooled to examine the level of knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS in India.

Results: A total of 47 studies (n= 307 501) were identified, and 43 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The overall level of knowledge about HIV/AIDS was 75% (95% CI: 69-80%; I2 = 99.8%), and a higher level of knowledge was observed among female sex workers (FSWs) 89% (95% CI: 77-100%, I2 = 99.5%) than students (77%, 95% CI: 67-87%, I2 = 99.6%) and the general population (70%, 95% CI: 62-79%, I2 = 99.2%), respectively. However, HIV/AIDS attitude was suboptimal (60%, 95% CI: 51-69%, I2 = 99.2%). Students (58%, 95% CI: 38-77%, I2 = 99.7%), people living with HIV/AIDS (57%, 95% CI: 44-71%, I2 = 92.7%), the general population (71%, 95% CI: 62-80%, I2 = 94.5%), and healthcare workers (HCWs) (74%, 95% CI: 63-84%, I2 = 0.0%) had a positive attitude towards HIV/AIDS. The methodological quality of included studies was "moderate" according to Joanna Briggs Institute’s checklist. Funnel plots are asymmetry and the Egger’s regression test and Begg’s rank test identified risk of publication bias.

Conclusion: The level of knowledge was 75%, and 40% had a negative attitude. This information would help formulate appropriate policies by various departments, ministries and educational institutions to incorporate in their training, capacity building and advocacy programs. Improving the knowledge and changing the attitudes among the Indian population remains crucial for the success of India’s HIV/AIDS response.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Knowledge, Attitudes, India

Introduction

Over three decades, HIV/AIDS infected around 37.9 million people globally and is a major public health problem.1 HIV/AIDS is the second most infectious disease globally, and India has the third largest HIV epidemic in the world.2 Since 1992, the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, took several phases of National AIDS Control Programmes (NACP) to improve public knowledge, awareness, and attitudes, as a part of the public health prevention and treatment programs.3 Over the preceding two decades, four phases of NACP have been implemented, and most recent reports suggest that the annual number of new HIV infections has decreased by 66%, and death rate by 54%, in India.3

Since the inception of HIV/AIDS, the only way to fight against this infectious disease is to increase awareness, knowledge, and modify general public’s behavior. Therefore, a lack of awareness, poor knowledge about various aspects of the disease, and negative perceptions can affect preventive initiatives to control HIV/AIDS. In India, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is highly heterogeneous, and dynamics in population, cultures, level of education, religion issues, and societies are frequently reported barriers that can affect an individual’s knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS.4-7 Several studies have been carried out to investigate the level of knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS in India.8-54 Indeed, since 2010, much evidence on this topic has been published. However, comprehensive scrutiny to understand the level of knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS among the Indian population has not been conducted. Thus, this study sought to systematically review and quantitatively estimate the current level of knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS in India.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.55 Cross-sectional observational studies, conducted in India, and published between January 1, 2010, to November 30, 2020, were considered and our search was initiated on April 10, 2020 until December 5, 2020.

Literature search

A literature search was conducted using a combination of the text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords in four databases: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase, and Google scholar, to identify peer-reviewed publications. Several keywords were used, such as; knowledge* OR attitude*, AND cross-sectional studies*, AND questionnaire*, AND surveys*, AND observational* AND sexually-transmitted diseases*, AND human immunodeficiency virus* OR HIV*, AND acquired immunodeficiency syndrome* OR AIDS*, AND physicians* OR doctors* OR primary care* OR dentists* OR dental* OR nurses* OR nursing* OR community health workers* OR public health nursing* OR health professionals* OR public health* OR pharmacy* OR medical students* OR nursing students* OR dental students* OR school students* OR population* OR community*, AND India*. A detailed list of keywords used to identify the literature is presented in Table S1 (Supplementary file 1). The field was limited to “title/abstract,” and the type of publication was limited to “original articles” or “full-length research articles”. We excluded interventional studies, letters, case reports, study protocols, reviews, opinions, grey literature, and non-peer-reviewed publications. The reference lists of articles were also examined to identify other potentially relevant articles. Surveys using open-ended questions focusing on knowledge and attitude about HIV/AIDS were considered. No published or in-progress systematic review on this topic was identified in the Cochrane Library and PROSPERO before this review. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered in PROSPERO 2019 (CRD42019140447).56

Selection of studies

Two researchers (AB and CC) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies, and further assessment was performed by three authors (RS, MC and KV). Only full-text papers available in the English were included. Small changes in the wording were also disregarded to understand their exact functional meaning. The authors excluded duplicates and studies conducted outside India.

Data extraction

The extracted data included the name of authors, year of publication, study design, study location, sampling, methods of administration of the questionnaire, and main results. All these details were captured and recorded in an Excel sheet. The information reported in or calculated from the included studies was used for analysis. Corresponding authors were not contacted for unpublished or additional information. Disagreements related to the inclusion of a study were resolved through consensus amongst the authors.

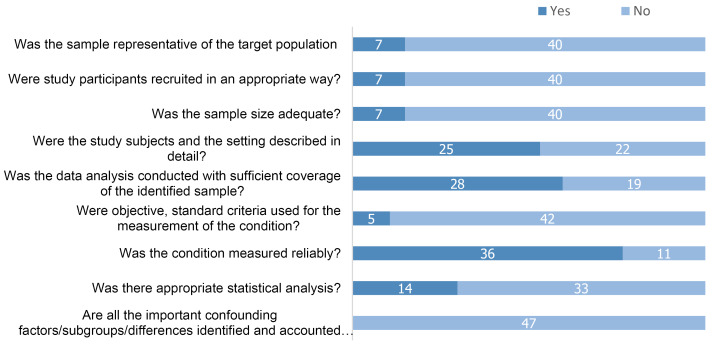

Quality assessment

Methodological quality and risk of bias of each study were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s checklist for critical appraisal,57 which comprises a nine-item checklist to evaluate whether the sample is representative of the target population. Questions include the following: were the study participants recruited appropriately?; was sample size adequate?; were the study subjects and settings described precisely?; was the data analysis used to identify the sample?; were objectives and standard criteria used to measure the condition?; and were important confounders identified or considered? The studies’ methodological quality was also assessed using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) scale.58

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA version 16 software (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas 77, 845 USA). The heterogeneity of the studies was evaluated using Cochrane’s Q-test and I2 statistics. We used DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effect model was used to calculate the overall and pooled effect size. Forest plots were used to demonstrate the selected studies in terms of estimates and presented as proportion (%) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Meta-regression was performed to identify the cause of heterogeneity in the year of publication. The differences in the knowledge and attitude across various study groups were assessed using subgroup analysis. The sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluation effect of each study on the combined result and publication bias was assessment with the funnel plot, “trim and fill” method, Begg’s and Egger’s test. Furthermore, studies were stratified based on high quality (over 75% of the STROBE checklist) and low quality (under 75% of the STROBE checklist). A two-tailed Pvalue of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

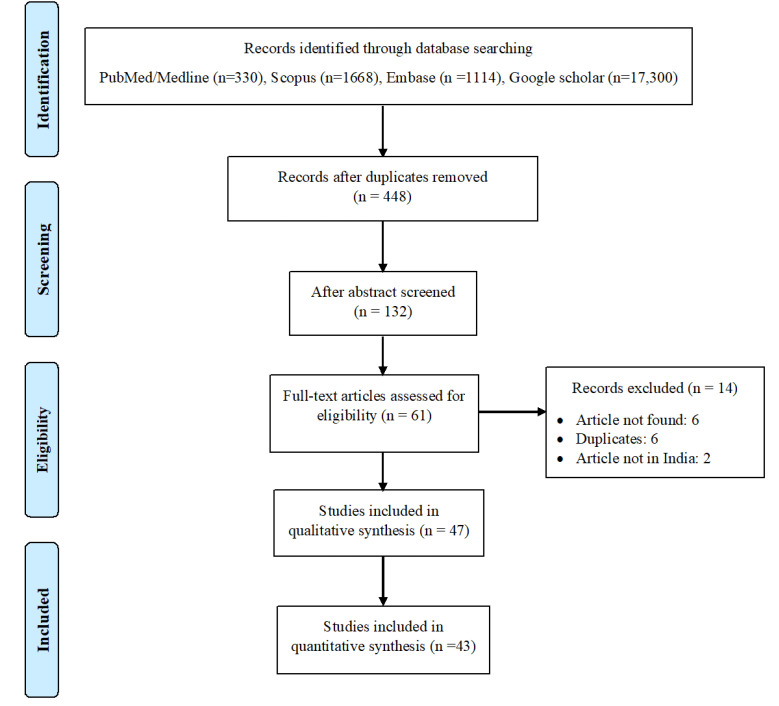

A total of 20 412 studies were obtained through database searching; after excluding irrelevant titles and duplicate records, a total of 132 abstracts were considered for screening. Of these, sixty-one studies were considered for the full-text review, and 14 were excluded for various reasons (Table S2, Supplementary file 1). Lastly, 47 studies8-54 were considered for the systematic review, and 43 were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).8-15,17-21,23-29,31-52,54

Figure 1.

Flow of information through different phases of the systematic review.

Study characteristics

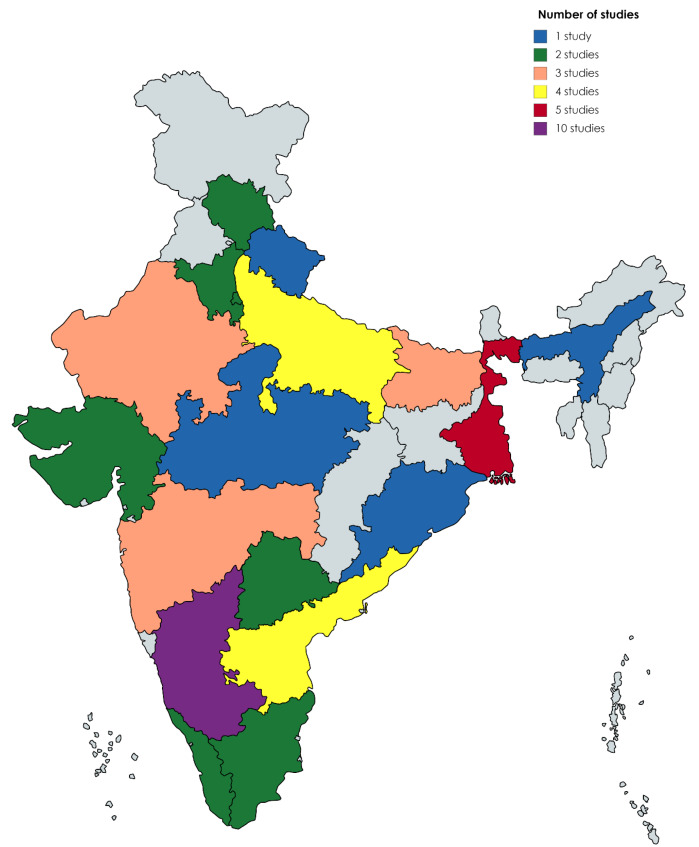

The studies included in the systematic review were cross-sectional observational studies using face-to-face or self-administered questionnaires, published between January 1, 2010 to November 30, 2020. A total of forty-seven studies,8-54 comprising 307 501 participants, were included, and the number of studies reporting knowledge and attitude about HIV/AIDS in India, by state, is shown in Figure 2. These studies come from most of the Indian states with Karnataka state having ten studies included in the current review.

Figure 2.

Number of studies reporting knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS in India by state.

The sample sizes ranged from 3623 to 132 678.52 The primary target population across studies were students (n=19),10,14,15,17,21,23,26,27,29,31,34,35,37,38,40,42,46,47,49 general population (n=9),9,13,18-20,43,48,51,52 healthcare workers [HCWs] (n=5),8,24,28,41,50 people living with HIV (PLWHIV) (n=4),25,32,33,36 and female sex workers (FSWs) (n=3).11,12,45 More details are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Core characteristics of the studies included in Systematic review and Meta-analysis .

| Author | Year | Study design | Study location | Quality assessment | Sample size | Focusing group | Questionnaire administration | Outcome | Quality a | References |

| Ghosh et al | 2020 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Kolkata | <75% | 250 | Nurses | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 8 |

| Joshi et al | 2020 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Jodhpur | <75% | 1200 | Slums | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 9 |

| Vittal and Murthy | 2020 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Andhra Pradesh | <75% | 234 | Medical and nursing students | Self-administered | Poor knowledge and positive attitude | 3 | 10 |

| Kumar | 2020 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Uttar Pradesh | <75% | 195 | Female sex workers | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 5 | 11 |

| Sinha et al | 2020 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Alipurduar | <75% | 90 | Female sex workers | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, negative attitude and positive practice | 6 | 12 |

| De Souza et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Mangalore | <75% | 1535 | Students, teachers and parents | Self-administered | Modest knowledge | 6 | 13 |

| Saheer et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Kerala | <75% | 341 | Dental students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, negative attitude | 5 | 14 |

| Biswas and Bandyopadhyay | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | West Bengal | >75% | 296 | School students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge | 4 | 15 |

| Sarkar et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Kolkata | <75% | 220 | PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Negative perception | 5 | 16 |

| Limaye et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Mumbai | >75% | 199 | College students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 5 | 17 |

| Meharda et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Ajmer | <75% | 288 | Slums | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and poor practice | 5 | 18 |

| Singh et al | 2019 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Patna | <75% | 120 | General population | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and attitude, poor practice | 5 | 19 |

| Khandekar and Walvekar | 2018 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Kangrali | <75% | 400 | Married men | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 6 | 20 |

| Chowdary et al | 2018 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Guntur | <75% | 400 | Engineering students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and attitude | 6 | 21 |

| Doda et al | 2018 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Uttarakhand | >75% | 385 | Consultants, residents, medical students, laboratory technicians, and nurses | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, receptive attitude and satisfactory practice | 7 | 22 |

| Roy et al | 2018 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Eastern India | <75% | 36 | Medical students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 5 | 23 |

| Dhanya et al | 2017 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Trichur district of Kerala | <75% | 206 | Dentists | Self-administered | Positive knowledge, attitude and practice | 6 | 24 |

| Banagi Yathiraj et al | 2017 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Manglore, Karnataka | <75% | 409 | PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Poor knowledge | 7 | 25 |

| Subbarao and Akhilesh | 2017 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Bengaluru and others | <75% | 350 | Engineering students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and negative attitude | 5 | 26 |

| Rahman and Santhosh Kumar | 2017 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Chennai | <75% | 100 | Undergraduate students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and negative attitude | 6 | 27 |

| Ngaihte et al | 2017 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Delhi, Gandhinagar, Bhubaneswar, and Hyderabad | <75% | 503 | Dentists | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and modest attitude | 6 | 28 |

| Kalyanshetti and Nikam | 2016 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Belgavi | <75% | 102 | Nursing students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 5 | 29 |

| Baruah et al | 2016 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Jorhat | <75% | 261 | Adolescents | Face-to-face | Unclear | 3 | 30 |

| Chaudhary et al | 2016 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Jaipur | >75% | 613 | School students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 31 |

| Gupta et al | 2016 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Himachal Pradesh | <75% | 150 | PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, positive attitude and negative perception | 5 | 32 |

| Bhagavathula et al | 2015 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Warangal, Telangana | >75% | 542 | Family of PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, modest attitude and positive perception | 8 | 33 |

| Kumar et al | 2015 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Raichur | <75% | 425 | Medical and dental students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and attitude | 6 | 34 |

| Gupta et al | 2015 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh | <75% | 250 | Technical institute students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 35 |

| Mittal et al | 2015 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Karnataka, Davangere | <75% | 100 | PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Poor knowledge and attitude | 6 | 36 |

| Dubey et al | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | North India | <75% | 630 | College students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 7 | 37 |

| Grover et al | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | NCR | <75% | 600 | Dental students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 5 | 38 |

| Jogdand and Yerpude | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Guntur | <75% | 138 | Medical students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 39 |

| Oberoi et al | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | NCR | <75% | 610 | Dental students | Face-to-face | Poor knowledge and positive attitude | 5 | 40 |

| Prabhu et al | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Tamilnadu | <75% | 102 | Dentists | Self-administered | Positive knowledge | 5 | 41 |

| Sakalle et al | 2014 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Indore district | <75% | 200 | School students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 42 |

| Tondare et al | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Mumbai | <75% | 256 | Adolescents | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and modest attitude | 6 | 43 |

| Jindal | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Moodbidri | <75% | 300 | College students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 4 | 44 |

| Hemalatha et al | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Andhra Pradesh | <75% | 5580 | Female sex workers | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 4 | 45 |

| Gupta et al | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Lucknow | <75% | 215 | School students | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 5 | 46 |

| Aggarwal and Panat | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Bareilly | >75% | 460 | Dental students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and attitude | 6 | 47 |

| Cooperman et al | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Mumbai | <75% | 300 | Women | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 6 | 48 |

| Fotedar et al | 2013 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Shimla | >75% | 191 | Dental students | Self-administered | Positive knowledge and negative attitude | 6 | 49 |

| Achappa et al | 2012 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Manglore | >75% | 200 | Nurses | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge, attitude and perception | 6 | 50 |

| Yadav et al | 2011 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Saurashtra | >75% | 1237 | Young population | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge | 5 | 51 |

| Hazarika | 2010 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Rural and urban | <75% | 132678 | General population | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 4 | 52 |

| Jayanna et al | 2010 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Karnataka | <75% | 393 | Female sex workers | Face-to-face | Unclear | 4 | 53 |

| Taraphdar et al | 2010 | Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Kolkata | >75% | 90 | PLWHIV | Face-to-face | Positive knowledge and attitude | 5 | 54 |

aJoanna Briggs Institute’s criteria

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS

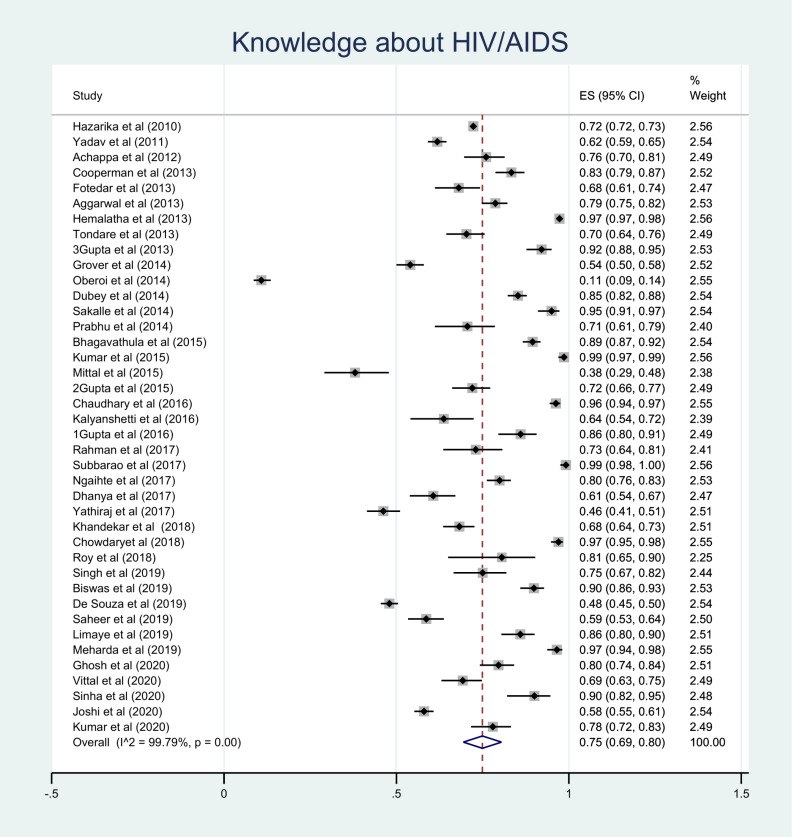

Forty studies reported on knowledge about HIV/AIDS,8-15,17-21,23-29,31-38,40-43,45-52 where the overall level of knowledge was 75% (95% CI: 69-80%, P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS.

The subgroup analysis showed the level of knowledge about HIV/AIDS was high among FSWs (89%),11,12,45 while the level of knowledge among PLWHIV was 65%.25,32,33,36 Additional information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Subgroup analysis of Knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS .

| Subgroups | Knowledge | Attitude | ||||

| Studies | Sample size | Estimates (95% CI) | Studies | Sample size | Estimates (95% CI) | |

| PLWHIV | 5 | 1291 | 65% (40% - 90%) | 4 | 882 | 57% (44% - 71%) |

| Healthcare workers | 5 | 1261 | 74% (67% - 80%) | 3 | 909 | 74% (63% - 84%) |

| Students | 19 | 5366 | 77% (67% – 87%) | 13 | 4540 | 58% (38% - 77%) |

| General public* | 10 | 138 014 | 70% (62% - 79%) | 4 | 133 454 | 71% (62% - 80%) |

| Female sex workers | 3 | 5865 | 89% (77% - 100%) | 1 | 90 | 18% (11% - 27%) |

| Low qualitya | 34 | 149 293 | 73% (67% - 80%) | 18 | 104 593 | 60% (29% - 92%) |

| High qualityb | 9 | 3828 | 81% (71% - 91%) | 6 | 1682 | 60% (52% - 69%) |

a<75% response rate and b≥75% response rate.

*General population, community residents, school students, prisoners, and pregnant women.

Attitude towards HIV/AIDS

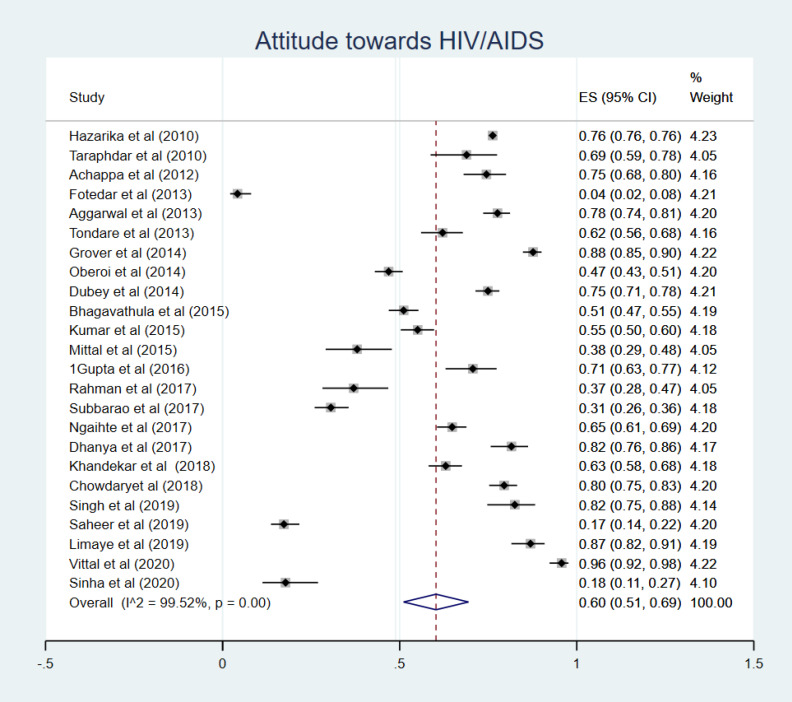

Twenty-four studies reported the attitude towards HIV/AIDS,10,12,14,17,19-21,24,26-28,32-34,36-38,40,43,47,49,50,52,54 where an overall percentage of 60% (95% CI: 51-69%, P< 0.001) of subjects had a positive attitude about HIV/AIDS (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Attitude towards HIV/AIDS.

Subgroup analysis showed that HCWs,24,28,50 as well as general population,19,20,43,52 had a positive attitude towards HIV/AIDS, with 74% (95% CI: 63-84%) and 71% (95% CI: 62-80%), respectively. However, only one study investigated the level of attitude about HIV/AIDS in FSWs12 and reported only 18% (95% CI: 11-27%). More information is presented in Table 2.

Meta-regression

Meta-regression based on the year of publication was considered to understand the influence of each study on the overall effect size. Meta-regression analysis suggested no influence of year of publication on the knowledge (Coef= - 0.0052, P=0.773) and attitude towards HIV/AIDS (Coef= 0.0036, P =0.737) (Figure S1, Supplementary file 1).

Sensitivity analysis

To address the issue of heterogeneity, studies were classified into high (>75%) and low quality (<75%), according to the STROBE checklist for methodological quality. High-quality studies reported higher knowledge about HIV/AIDS than low-quality studies (81% vs 73%). However, no significant difference in the attitude levels was seen between low- and high-quality studies (Table 2). Figure S2 (Supplementary file 1) presented sensitivity analysis for included studies and showed significant differences beyond the limits of 95% CI of calculated combined results.

Study quality assessment

Study quality was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s criteria (Figure 5), where a set of nine criteria were used to evaluate the quality of the studies. Seven studies showed that the sample represented the target population,20,24,25,27,33,51,52 the participants have been recruited appropriately,8,11,12,16,18,33,43 and calculated the sample size.11,18,20,22,25,33,43 Twenty-five studies described their study settings,9,11,12,19,21-25,27,29,31,33-37,39,42,47-50,53,54 Thirty-two studies conducted the data analysis sufficiently8,9,13-22,24-28,31-37,39,41-43,48-51 and five studies used standard criteria to assess HIV/AIDS.19,22,28,35,48 The majority of the included studies measured precisely, 8,12,13,20-29,31-52,54 14 studies used appropriate statistical analysis,9,13,14,17,20,22,25,28,33,37,38,40,46,47 but none identified major confounders and subgroups.8-54

Figure 5.

Quality assessment of included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s criteria.

Publication bias

Publication bias was highlighted in included studies and was confirmed by asymmetric funnel plots. Furthermore, the Begg’s rank test identified a considerable proportion of bias in the knowledge statements (P < 0.05) and the Egger’s regression test showed a statistically significant publication bias in the attitude statements related to HIV/AIDS (P < 0.05) (Table 3). To reduce this publication bias Trim and fill analysis was conducted and the result was depicted on Figure S3 (Supplementary file 1).

Table 3. Risk of bias .

| Egger test | Begg’s test | |||

| t-value | P value | z-value | P value | |

| Knowledge | 0.08 | 0.938 | 2.34 | 0.019 |

| Attitude | -2.27 | 0.033 | 1.22 | 0.224 |

Discussion

In the present study, we assimilated studies that assessed knowledge and attitude of HIV/AIDS in India, published from January 2010 to November 2020. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of this topic. However, some prior reviews have investigated the level of adherence to antiretroviral therapy59 and HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in India.60 We identified a total of 47 studies that evaluated the knowledge and attitude of HIV/AIDS in 307 501 participants; accordingly, we were able to perform a series of robust meta-analyses, therein providing a hitherto unreported insight into knowledge and attitude about HIV/AIDS in the Indian population.

Our results are interesting, indeed, as three-quarters (75%) of the subjects had adequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS, but only 60% exhibited a positive attitude. Our findings are consistent with another meta-analysis conducted on an Arabian population where the level of knowledge was 74.4%, and attitude was 53% towards HIV/AIDS, respectively.61 Such findings are somewhat lackluster, given the NACP has undertaken several initiatives to increase awareness among the general population by implementing a large number of innovative awareness programs for HIV prevention. For instance, in 2018, NACO initiated multimedia campaigns across television channels, radio broadcastings, online programs, and at cinemas to increase HIV awareness among the general population. A special emphasis was given to HIV testing among the young population.62 In 2017, NACO conducted a national survey on the wider Indian population and identified that only one-third of men and one-fifth of women aged between 15-49 had sufficient knowledge of HIV/AIDS.63 These findings point to a systematic lack of comprehensive knowledge, prevalent in India, and such deficits in knowledge levels may contribute to false perceptions towards HIV/AIDS. Hence, it is clear that there is much room for improvement in facilitating increases in the basic knowledge about HIV/AIDS among the Indian population through intensive, scientifically guided, educational interventions.

Further, it was observed that the lack of sufficient knowledge reflected negatively on attitudes, and some studies reported more than half of the subjects had a negative attitude towards HIV/AIDS.12,14,26,27,36,40,49 The underlying differences in their attitudes are plausibly due to lack of adequate knowledge, negative perception, variations in the sociocultural taboos, and other characteristics that might underlie this negative attitude. For example, a 2016 survey, by the United Nations AIDS study, found that a third of Indian adults had a discriminatory attitude towards PLWHIV, and suggested that activities related to reducing stigma and discrimination are similar to the levels recorded a decade earlier in 2006.64 In our subgroup analysis, around 43% of the PLWHIV, 42% of the students, 29% of the general population, and a quarter of HCWs, demonstrated a negative attitude towards HIV/AIDS. Although it is difficult to identify the underlying rationale for these negative attitudes, several studies in India have shown that one-third to half of the respondents, including HCWs. They blame PLWHIV for their infection, endorse denial of their right to marry, and support their isolation from the community.60,65 While India made considerable progress in reducing new infections and HIV-related mortality, further efforts are required to change, not only the attitude, but also the pervasive public behaviors, inequalities, societal taboos, stigma, and discrimination towards HIV/AIDS. The wide variations in the knowledge and differences in attitudes reflect the lack of adequate understanding and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS across subgroups. Health administrators and policymakers’ role in providing sufficient training and interventions to level up the awareness and changing the attitude may change the stigma and other inequalities among the HIV/AIDS population.

Although the present study presents a novel addition to the literature, some limitations should be addressed. Firstly, through a comprehensive search strategy, we included 43 cross-sectional observational studies in the meta-analysis and showed high heterogeneity and variations in the responses. This resulted in a significant publication bias, as shown in the asymmetric funnel plots, Begg’s rank test, and Egger’s regression test, respectively. Considering this, only a limited number of studies reported the sample size,11,18,20,22,25,33,43 and following the STROBE checklist, we have identified that most of the studies included had low methodological quality. Expecting a high heterogeneity, we used a random-effect model and performed a subgroup analysis to investigate the source of heterogeneity. Secondly, although several comprehensive, validated questionnaires to measure the knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS are freely available,66-71 most of the studies did not use validated questionnaires. Thus, because of the non-uniformity of study instruments across the studies, we provided only general observations of knowledge and attitudes of HIV/AIDS. Thirdly, all the studies used self-administered questionnaires, and responses are self-reported; therefore, it is conceivable that responses may overestimate or underestimate the true responses and recall bias. Finally, as the sociodemographic, sociocultural, and geographic variations influence the level of awareness and attitudes, it should be considered in future research.

Conclusion

The overall knowledge about HIV/AIDS in India was found to be reasonable (75%), with about two-thirds (60%) of those indicating a positive attitude. However, students predominantly had a negative attitude towards HIV/AIDS. This evidence-based information would help formulate appropriate policies by the concerned departments, ministries and educational institutions in India. The government should keep designing effective training, capacity building, and strong advocacy programs to improve the general population’s knowledge levels thereby reducing the false perceptions, stigma, and discrimination towards PLWHIV. Finally, improving the knowledge and changing the attitudes among the Indian population remains crucial for the success of India’s HIV/AIDS response. The study findings will add value to the existing scientific knowledge base not only for India but also at global level in this domain.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank PROSPERO, National Institute of Health Research for reviewing and approving our study protocol.

Funding

Nil.

Competing interests

Vijay Kumar Chattu is an Advisory Board Member for Health Promotion Perspectives. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

AB, CC, RS, MC, KV and VC conceptualized and designed the study. AB and CC independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies, and further assessment was performed by three authors RS, MC and KV. AB conducted the statistical analysis and others assisted with data extraction and curation of the database. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and provided critical inputs in the draft manuscript. VC edited the final draft and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Online Supplementary file 1 contains Tables S1-S2 and Figures S1-S3.

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2019. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

- 2. National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. India HIV Estimates 2015: Technical Report. Available from: www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/India%20HIV%20Estimations%202015.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- 3. National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Annual Report 2014-2015. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization; 2015. Available from: www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/annual_report%20_NACO_2014-15_0.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 4.Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, Ramasamy J. Challenges in HIV care: accelerating the pace of HIV-related services to accomplish the set global targets. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2017;10(3):509–10. doi: 10.4103/1755-6783.213162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS. Battling against the epidemic of HIV infection ensuring that everybody counts. Prim Health Care. 2020;10(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Unnikrishnan B, Thapar R, Mithra P, Kulkarni V, Holla R. et al. Stigmatization and discrimination toward people living with HIV/AIDS in a coastal city of South India. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(3):226–32. doi: 10.1177/2325957415569309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machowska A, Bamboria BL, Bercan C, Sharma M. Impact of ‘HIV-related stigma-reduction workshops’ on knowledge and attitude of healthcare providers and students in Central India: a pre-test and post-test intervention study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e033612. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh N, Dey A, Majumdar S, Haldar D. Knowledge and awareness among nurses in tertiary care hospitals of Kolkata regarding HIV positive patient care: a cross-sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2020;7(6):2357–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi V, Joshi NK, Bajaj K, Bhardwaj P. HIV/AIDS awareness and related health education needs among slum dwellers of Jodhpur city. Indian J Community Health. 2020;32(1):167–9. doi: 10.47203/IJCH.2020.v32i01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vittal CS, Murthy GK. Vittal CS, Murthy GKKnowledge attitude and practice study on HIV/AIDS among 1st year MBBS medical students & 1st year BScnursing students in a private medical college in W G DIST, AP. Int J Sci Res. 2020;9(1):59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A. Study on HIV/AIDS Knowledge in Female Sex Workers in Moradabad District of Uttar Pradesh. UGC Care J. 2020;19(21):206–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha A, Goswami DN, Haldar D, Choudhury KB, Saha MK, Dutta S. Sociobehavioural matrix and knowledge, attitude and practises regarding HIV/AIDS among female sex workers in an international border area of West Bengal, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(3):1728–32. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1196_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Souza NJ, Kolipaka RP, Kumar J, Hegde AM. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a questionnaire study among students, teachers, and parents in Mangalore, India. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2019;17(1):70–5. doi: 10.4103/jiaphd.jiaphd_139_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saheer PA, Fabna K, Febeena PM, Devika S, Renjith G, Shanila AM. Knowledge and attitude of dental students toward human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients: a cross-sectional study in Thodupzha, Kerala. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2019;17(1):66–9. doi: 10.4103/jiaphd.jiaphd_47_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas R, Bandyopadhyay R. A study on awareness of HIV/AIDS among adolescent school girls in an urban area of North Bengal, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6(2):875–8. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar T, Karmakar N, Dasgupta A, Saha B. Stigmatization and discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS attending antiretroviral clinic in a centre of excellence in HIV care in India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6(3):1241–6. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limaye D, Fortwengel G, Limaye V, Bhasi A, Dhule A, Dugane R. et al. A study to assess knowledge and attitude towards HIV among students from Mumbai university. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7(6):1999–2002. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20192158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meharda B, Sharma SK, Keswani M, Sharma RK. A cross sectional study regarding awareness of HIV/AIDS and practices of condoms among slum dwellers of Ajmer, Rajasthan, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7(7):2604–9. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20192886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh G, Ahmad S, Kumari A, Kumar P, Ranjan A, Agarwal N. A study of Knowledge, Attitude, Behaviour and Practice (KABP) among the attendees of the Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre of Tertiary Care Hospital of Bihar, India. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2019;50(4):153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandekar SG, Walvekar PR. Knowledge and attitude about human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among married men in Kangrali, India: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9(9):89–93. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2018.00974.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdary SD, Dasari N, Chitipothu DM, Chitturi RT, Chandra KL, Reddy BV. Knowledge, awareness, and behavior study on HIV/AIDS among engineering students in and around Guntur, South India. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2018;7(1):26–30. doi: 10.4103/jdrntruhs.jdrntruhs_110_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doda A, Negi G, Gaur DS, Harsh M. Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a survey on the knowledge, attitude, and practice among medical professionals at a tertiary health-care institution in Uttarakhand, India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2018;12(1):21–6. doi: 10.4103/ajts.AJTS_147_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy PK, Jha AK, Zeeshan M, Chaudhary RK. Knowledge regarding HIV/AIDs in medical students. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2018;28(1):35–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhanya RS, Hegde V, Anila S, Sam G, Khajuria RR, Singh R. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards HIV patients among dentists. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7(2):148–53. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_57_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banagi Yathiraj A, Unnikrishnan B, Ramapuram JT, Thapar R, Mithra P, Madi D. et al. HIV-related knowledge among PLWHA attending a tertiary care hospital at Coastal South India-a facility-based study. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(6):615–9. doi: 10.1177/2325957417742671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subbarao NT, Akhilesh A. Knowledge and attitude about sexually transmitted infections other than HIV among college students. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38(1):10–4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.196888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman R, Santhosh Kumar MP. Knowledge, attitude, and awareness of dental undergraduate students regarding human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(5):175–80. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i5.17277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ngaihte PC, Santella AJ, Ngaihte E, Watt RG, Raj SS, Vatsyayan V. Knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus, attitudes, and willingness to conduct human immunodeficiency virus testing among Indian dentists. Indian J Dent Res. 2016;27(1):4–11. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.179806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalyanshetti SB, Nikam K. A study of knowledge of HIV/AIDS among nursing students. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2016;5(6):1209–12. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2016.10022016374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baruah A, Das BR, Sarkar AH. Awareness about sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents in urban slums of Jorhat district. Int J Med Sci Public Heal. 2016;5(11):2373–7. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2016.02062016509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhary P, Solanki J, Yadav OP, Yadav P, Joshi P, Khan M. Knowledge and attitude about human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome among higher secondary school students of Jaipur city: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2016;14(2):202–6. doi: 10.4103/2319-5932.183800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta M, Mahajan VK, Chauahn PS, Mehta KS, Rawat R, Shiny TN. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of disease among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immuno deficiency syndrome: a study from a tertiary care center in North India. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2016;37(2):173–7. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.185500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhagavathula AS, Bandari DK, Elnour AA, Ahmad A, Khan MU, Baraka M. et al. Across sectional study: the knowledge, attitude, perception, misconception and views (KAPMV) of adult family members of people living with human immune virus-HIV acquired immune deficiency syndrome-AIDS (PLWHA) Springerplus. 2015;4:769. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1541-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar V, Patil K, Munoli K. Knowledge and attitude toward human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immuno deficiency syndrome among dental and medical undergraduate students. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S666–71. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.163598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta PP, Verma RK, Tripathi P, Gupta S, Pandey AK. Knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS among students of a technical institution. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27(3):285–9. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2014-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mittal D, Babitha GA, Prakash S, Kumar N, Prashant GM. Knowledge and attitude about HIV/AIDS among HIV-positive individuals in Davangere. Soc Work Public Health. 2015;30(5):423–30. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2015.1046628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubey A, Sonker A, Chaudhary RK. Knowledge, attitude, and beliefs of young, college student blood donors about Human immunodeficiency virus. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8(1):39–42. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grover N, Prakash A, Singh S, Singh N, Singh P, Nazeer J. Attitude and knowledge of dental students of National Capital Region regarding HIV and AIDS. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(1):9–13. doi: 10.4103/0973-029x.131882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jogdand KS, Yerpude PN. A study on knowledge and awareness about HIV/AIDS among first year medical students in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2014;5(3):45–8. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2014.00271.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberoi SS, Marya CM, Sharma N, Mohanty V, Marwah M, Oberoi A. Knowledge and attitude of Indian clinical dental students towards the dental treatment of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Int Dent J. 2014;64(6):324–32. doi: 10.1111/idj.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prabhu A, Rao AP, Reddy V, Krishnakumar R, Thayumanavan S, Swathi SS. HIV/AIDS knowledge and its implications on dentists. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5(2):303–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.136171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakalle S, Pandey D, Dixit S, Shukla H, Saroshe S. A study to assess knowledge and awareness about the HIV/AIDS among students of government senior secondary school of Central India. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2014;5(2):80–5. doi: 10.5958/j.0976-5506.5.2.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tondare D, Sekhar KC, Kembhavi RS. Knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases and HIV among adolescent boys in urban slums of Mumbai. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2013;4(1):75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jindal S. Awareness about HIV/AIDS in selected pre university colleges in Moodbidri: a cross-sectional study. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6(Suppl 1):208–10. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemalatha R, Kumar RH, Venkaiah K, Srinivasan K, Brahmam GN. Prevalence of & knowledge, attitude & practices towards HIV & sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among female sex workers (FSWs) in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(4):470–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta P, Anjum F, Bhardwaj P, Srivastav J, Zaidi ZH. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among secondary school students. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(2):119–23. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.107531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aggarwal A, Panat SR. Knowledge, attitude, and behavior in managing patients with HIV/AIDS among a group of Indian dental students. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(9):1209–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooperman NA, Shastri JS, Shastri A, Schoenbaum E. HIV prevalence, risk behavior, knowledge, and beliefs among women seeking care at a sexually transmitted infection clinic in Mumbai, India. Health Care Women Int. 2014;35(10):1133–47. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.770004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fotedar S, Sharma KR, Sogi GM, Fotedar V, Chauhan A. Fotedar S, Sharma KR, Sogi GM, Fotedar V, Chauhan AKnowledge and attitudes about HIV/AIDS of students in HPGovernment Dental College and Hospital, Shimla, India. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(9):1218–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Achappa B, Mahalingam S, Multani P, Pranathi M, Madi D, Unnikrishnan B. et al. Knowledge, risk perceptions and attitudes of nurses towards HIV in a tertiary care hospital in Mangalore, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(6):982–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yadav SB, Makwana NR, Vadera BN, Dhaduk KM, Gandha KM. Awareness of HIV/AIDS among rural youth in India: a community based cross-sectional study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5(10):711–6. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hazarika I. Knowledge, attitude, beliefs and practices in HIV/AIDS in India: identifying the gender and rural–urban differences. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3(10):821–7. doi: 10.1016/s1995-7645(10)60198-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jayanna K, Washington RG, Moses S, Kudur P, Issac S, Balu PS. et al. Assessment of attitudes and practices of providers of services for individuals at high risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in Karnataka, south India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(2):131–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taraphdar P, Ray TG, Haldar D, Dasgupta A, Saha B. Perceptions of people living with HIV/AIDS. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;64(10):441–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. PROSPERO website. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=188371. Accessed 2 March 2021.

- 57.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chakraborty A, Hershow RC, Qato DM, Stayner L, Dworkin MS. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV patients in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2130–48. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bharat S. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in India: current understanding and future needs. SAHARA J. 2011;8(3):138–49. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2011.9724996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aldhaleei WA, Bhagavathula AS. HIV/AIDS-knowledge and attitudes in the Arabian Peninsula: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(7):939–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Annual Report 2018-2019. National AIDS Control Organization (NACO); 2019. Available from: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/24%20Chapter%20496AN2018-19.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2020.

- 63. IIPS and MHFW (Indian Institute of Population Sciences & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16. Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2017. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR339/FR339.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2020.

- 64. UNAIDS. AIDS Data 2019. 2019. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf. Accessed August 10 2020.

- 65.Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of literature in AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(4):617–28. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beaulieu M, Adrien A, Potvin L, Dassa C. Stigmatizing attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS: validation of a measurement scale. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(2):172–82. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balogun JA, Abiona TC, Lukobo-Durrell M, Adefuye A, Amosun S, Frantz J. et al. Evaluation of the content validity, internal consistency and stability of an instrument designed to assess the HIV/AIDS knowledge of university students. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2010;23(3):400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Segura-Cardona A, Berbesí-Fernández D, Cardona-Arango D, Ordóñez-Molina J. [Preliminary construction of a questionnaire about knowledge of HIV/AIDS in Colombian veterans] Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28(3):503–7. doi: 10.1590/s1726-46342011000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zelaya CE, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, Srikrishnan AK, Suniti S, Celentano DD. Measurement of self, experienced, and perceived HIV/AIDS stigma using parallel scales in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24(7):846–55. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.647674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Program on AIDS Social and Behavior Research Unit. Research package: knowledge, attitude, beliefs and practices on AIDS (KABP). Phase I, Release 20.01.90. Geneva: WHO; 1990.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Supplementary file 1 contains Tables S1-S2 and Figures S1-S3.