Abstract

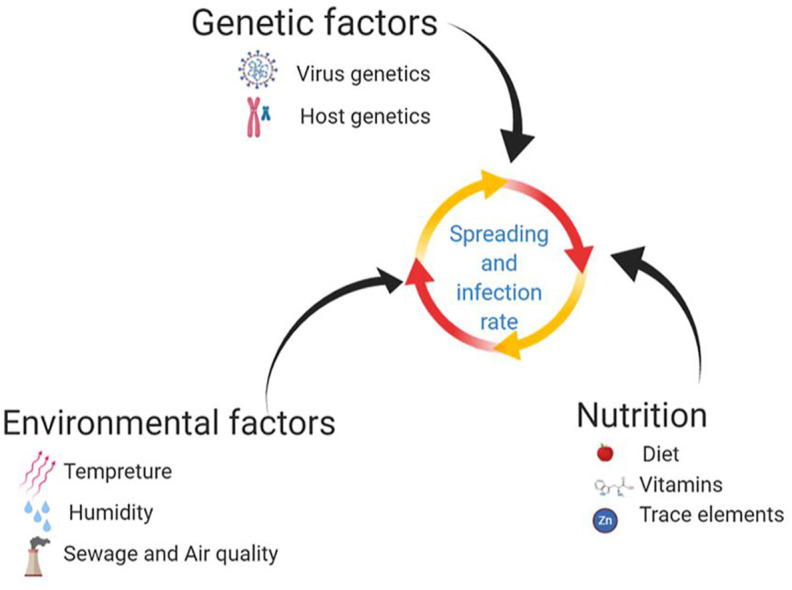

Several factors ranging from environmental risks to the genetics of the virus and that of the hosts, affect the spread of COVID-19. The impact of physicochemical variables on virus vitality and spread should be taken into account in experimental and clinical studies. Another avenue to explore is the effect of diet and its interaction with the immune system on SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality rate. Past year have witnessed extensive studies on virus and pathophysiology of the COVID-19 disease and the cellular mechanisms of virus spreading. However, our knowledge has not reached a level where we plan an efficient therapeutic approach to prevent the virus entry to the cells or decreasing the spreading and morbidity in severe cases of disease. The risk of infection directly correlates with the control of virus spreading via droplets and aerosol transmission, as well as patient immune system response. A key goal in virus restriction and transmission rate is to understand the physicochemical structure of aerosol and droplet formation, and the parameters that affect the droplet-borne and airborne in different environmental conditions. The lifetime of droplets on different surfaces is described based on the contact angle. Hereby, we recommend regular use of high-quality face masks in high temperature and low humidity conditions. However, in humid and cold weather conditions, wearing gloves and frequently hand washing, gain a higher priority. Additionally, social distancing rules should be respected in all aforementioned conditions. We will also discuss different routes of SARS-CoV-2 entry into the cells and how multiple genetic factors play a role in the spread of the virus. Given the role of environmental and nutritional factors, we discuss and recommend some strategies to prevent the disease and protect the population against COVID-19. Since an effective vaccine can prevent the transmission of communicable diseases and abolish pandemics, we added a brief review of candidate SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Keywords: COVID-19, Environmental factors, Diet, Cell entry, Genetics factors, Vaccine

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The world is going through an unpleasant situation as the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has infected a large portion of the world population and resulted in a significant death and mortality rate. For the first time, the world health organization (WHO) recognized the COVID-19 as a worldwide pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Nakada and Urban, 2020). To date (May 2021), there are over 165 million confirmed cases reported globally, with approximately 3.4 million of deaths (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/). Generally, three parameters affect the spreading of communicable diseases: the agent of transmission, the host, and the environment (Sobral et al., 2020). Immune systems, genetics, and host-virus interaction are heavily studied, while less attention is paid to the environmental factors and interaction of the virus, as a particle, with its surroundings.

Three months after the COVID-19 pandemic had started, researchers showed that the new coronavirus can survive for several hours as air particles and can last for days on surfaces. It has been demonstrated that virus causing COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), similar to SARS-CoV-1 has had an exponential collapse in titration of the virus in all experimental situations (Van Doremalen et al., 2020a). They found that the SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1 have a similar half-life under aerosol conditions, with an average estimate time ranging from 1.1 to 1.2 h and 95% credible intervals of 0.64–2.64 for SARS-CoV-2 and 0.78 to 2.43 for SARS-CoV-1 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b). Unfortunately, their observation was not supported by the WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statements (World Health Organization, 2020).

Droplets and airborne particles arising from speech, sneezing and coughing, play important roles in virus transmission and have been investigated to understand their influence in COVID-19 outbreak (Anfinrud et al., 2020).

There is a convention that aerosols smaller than 5 μm in aerodynamic diameter are also called droplet nuclei related to airborne transport. However, some researchers believe that aerosols larger than 20 μm and even 60 μm may correspond as droplet infection. Other reports indicated that medium-size particles contribute to the infection via both airborne and droplet ways. Large droplets fall quickly to the ground, while small droplets can become dehydrated and linger as “droplet nuclei”, move around 1–2 m in the air. However, smaller droplets stay suspended in the air similar to aerosol and therefore expand at the three-dimensional (Aliabadi et al., 2011; Cole and Cook, 1998). Several factors affect the size of the droplets including geometrical settings, super spreader persons, generation types (speaking, sneezing, coughing), person height, airflow patterns, and surrounding factors such as temperature, relative humidity and vapor pressure. Considering viruses as airborne and transmissible aerosol, significantly affects the decision of which kind of personal protective tools people need to use (Tellier et al., 2019).

For centuries, the human immune system has evolved and developed to protect the body against different pathogens. Being in the best condition, the immune system needs to access the different regulatory molecules, bioactive compounds and different substrates for biosynthesis and energy sources for increased rate of metabolism, this is particularly important during an infection, since immune system needs to deal with infection (Calder, 2020; Zabetakis et al., 2020). The most important vitamins to support immunity and protect the body against pathogens include vitamin A, B6, B12, folate, C, D and E. Furthermore, the trace elements including zinc, copper, selenium, and iron have been demonstrated to have key roles in reducing the risk of infections (Kandasamy et al., 2014; McGill et al., 2019). Therefore, a consistent and sustained supply of these nutrients is needed to maintain human health, and individuals must follow a diet plan to support and maintain the immune system more active during the COVID-19 pandemic. People with immune system deficiency and pre-existing diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are more susceptible to be affected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Cawood et al., 2020; Vuillier et al., 2020).

The cellular entry points and accessibility of cells are important for the spreading rate of one particular microorganism. In COVID-19, the respiratory system is a major target for the virus and different cell types in the upper and lower respiratory tract might be affected (Delgado-Roche and Mesta, 2020; Zabetakis et al., 2020). Since most of the targeted cells are in direct contact with air (with a thin layer of mucosal), then the virus can transmit in aerosols and could be very contagious (Sungnak et al., 2020). However, the virus's main pathway to entering the cells is not completely understood (Cao and Li, 2020). Therefore, we review the cellular pathways that the virus may pass and enter the target cells and start the infection. Besides, these days have been witness to strong challenges on whether the mutation in the virus genome or variability in host's genomes play a more pivotal role in infection rate and mortality rate (Day et al., 2020; Debnath et al., 2020).

Vaccines are the most effective medical tool against infectious diseases, and they not only prevent or ameliorate the disease severity but also reduce the transmission of the pathogens and decrease the mutation rate of the viruses in pandemics (Zhou et al., 2021).

In this review, we discuss the role of environmental factors and nutrition on SARS-CoV-2 spreading and infection rate. Then we provide some aspects of virus-cell entry mechanisms and the role of genetic factors in the severity of the disease. Finally, we discuss the effect of the vaccines in the protection against COVID-19.

2. Environment and virus transmission rate

2.1. Aerosols and droplets

The SARS-CoV-2 virus usually spreads through droplet or aerosol transmission and via the surfaces contaminated by nasal mucosa (Tellier, 2009). Airborne transmission is often referred to disease spread by aerosols or droplet nuclei, while infections that are caused by large droplets correspond to droplet transmission (Jayaweera et al., 2020; Judson and Munster, 2019). The WHO and CDC assume that the particle sizes more than 5 μm are shown as droplets, and particles which are smaller than 5 μm denoted as aerosols (WHO | Infection Prevention and Control of Epidemic-and Pandemic Prone Acute Respiratory Infections in Health Care, 2015; World Health Organization, 2020). This is in contrast to the theories showing that the pathogen with an aerodynamic diameter of 10–20 μm can remain in the air for a long time and travel long distances (Gralton et al., 2011).

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO has stated that SARS-CoV-2 spreads through direct contact when a symptomatic person coughs, sneezes, speaks or exhales (Morawska and Cao, 2020). The droplets of the virus exhaled from a sick person are too heavy to stay in the air and fall on the surfaces before they can reach a distance of more than 2 m. However, some droplets generated by an infected person, turn into smaller bioaerosol particles which are known as airborne (Morawska and Cao, 2020). In the other words, the big droplets are heavy and fall to the ground before evaporating, but the small ones can still convert to smaller droplets by evaporation and may stay on air currents for several hours. We can say that, in a tiny droplet, the moisture can evaporate and get lighter, resulting in floating on air currents before it has the chance to reach the surface. This is an old theory, taken from William Wells in the 1930s (Riley, 2001). In 1934, Wells used the simple estimation model to study the evaporation of falling droplets and obtained a classical diagram that revealed the relationship between evaporation, droplet size, and falling rate which has been modified by several researchers (Xie et al., 2007). An infection control strategy can be developed based on whether a respiratory infectious disease is primarily transmitted through the large or small droplets. Based on the Wells framework, a clear difference between droplets and aerosols can be obtained according to their size. Development of Wells law for COVID-19 was carried out recently by Bourouiba (2020). He believes that the cloud of multiphase turbulent gas or puff and ambient air can affect the drop's size range. If droplets are driven by coughing or sneezing, they can travel upward of 7–8 m. Moreover, Bourouiba found that cloud speed, humidity, and ambient temperature determine the droplet's persistent time in the air.

Recently, researchers reported the results of a laser light-scattering experiment that visualized the droplet generation and trajectories by speech (Anfinrud et al., 2020). They showed that breathing and conversation could produce much smaller particles. A super spreader person can produce many more aerosol particles than ta non-super spreader, and the resulting particles, due to low mass and gravity cannot pull down to the ground (Anfinrud et al., 2020; Meselson, 2020). In a lab setting machine generated droplets, the virus can survive in an aerosol form up to 16 h (Fears et al., 2020). Laser study of SARS-CoV-2 spreading indicated that normal speech generates aerosols that can float for several minutes or longer and are capable of transmitting disease indoors (Stadnytskyi et al., 2020). It was confirmed that the big drops and bioaerosol particles have different positions in the human respiratory system. Large droplets could be deposited in the upper regions of the respiratory system, while bioaerosolized particles can penetrate to the depths of the lungs, where they might be deposited in the alveoli (Meselson, 2020).

2.2. Droplets contact angle and its effect on evaporation

Infectious viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, can survive for long times on the surfaces until they reach a new host organism. It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 virus is able to survive 4 h to a few days on surfaces such as copper, stainless steel, aluminum, sterile sponges, plastic or latex surgical gloves, and therefore increasing the opportunity for touch transmission (Qu et al., 2020). In order to assess the SARS-CoV-2 transmission and spreading risk via surfaces, it is necessary to understand the interaction of the surface and droplet and evaluate the effects of the environmental variables, such as relative humidity and air temperature (Casanova et al., 2010). In this section we describe the importance of contact angle as an effective parameter on droplets maintenance on the surfaces. Wetting of a mineral surface can be defined by the term of “contact angle”. The measurement of contact angle for solid/water/gas systems is a very important parameter which is highly applicable in a broad range of research such as chemistry, biotechnology, pharmacy and mineral processing studies, including flotation and oil aggregation (Kowalczuk et al., 2016). In the scientific community, it has been accepted that a surface is hydrophobic when its static water contact angle (θ) is > 90°, due to attractive interaction between water and the hydrophobic surfaces, and is hydrophilic when θ is < 90° (Law, 2014). Moreover, the observation of water droplets at θ > 90° can be related to the high cohesion of the water droplet. Therefore, when the contact angle of water is smaller than 90°, the droplet can cover the surface, while a greater contact angle than 90° on the surface leads to a spherical state. On the other hand, the spherical water droplet prefers to be in the droplet state rather than wetting the surface (dispersion on the surface) due to the small wetting energy. Thus, the competition between wetting and droplet cohesion can change the surface properties from hydrophilic to hydrophobic. The relationship between evaporation and contact angle is that reducing the contact angle increases the contact area or surface area between the droplet and the surface of solid and reduces the droplet thickness and enhances heat conduction through the droplet (Bourges-Monnier and Shanahan, 1995). Picknett and Bexon point out a decrease of evaporation rate with increasing contact angle (Picknett and Bexon, 1977). Birdi and Vu show that the weight loss of wetting drops (θ < 90°) is linear with time and the contact diameter constant. But, for non-wetting liquids, contact angle remains constant, and the diameter decreases (Birdi and Vu, 1993). The outbreak of coronavirus and its remaining on the surface has resulted in debate, and some studies have been published on this topic. Based on data from laboratory studies, a person may be infected with SARS-CoV-2 by touching a surface or object that contains the virus on it and then touching their own mouth, nose, or eyes. Thus, the subject of the surface and its physical and chemical characteristics as well as the environmental parameters, humidity and temperature, are key factors affecting survival rates of SARS-CoV-2. If contact angle between droplet and surface is greater than 90° (θ > 90°), the droplet tends to spherical shape (hydrophobic) or non-wetting drops as seen on plastic and stainless steel after 72 and 48 h (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b). While the contact angle of water on copper is < 90°, no viable SARS-CoV-2 was measured after 4 h (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b). Hydrophilic metal surfaces (copper, nickel) are completely wetted by water only if the surfaces are extremely clean. It should be noted that surface contamination reduces the wettability drastically. If a hydrophilic surface is in contact with droplets of the virus, it tends to cover the surface, and the shape of drop changes from spherical to semi flat figure. Thus, the surface area of the semi-flat drop increases, and consequently the evaporation could be enhanced. By increasing the evaporation rate of the water around the droplet, only the bare virus and its solid attachments remain on the surface. However, in hydrophobic surfaces such as plastic, the water evaporation rate due to the volumetric or spherical shapes is low, and water hydration shells protect the virus. We have now compared some materials and contact angles in Table 1 . It can be seen that SARS-CoV-2 is more stable on hydrophobic materials in comparison to hydrophilic materials.

Table 1.

Comparison of different surfaces with different contact angles and long life of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1.

| Surface | Long life (hour) |

Contact angle (◦) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-1 | ||

| Copper | 4 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | 8 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | θ < 90° (“The Wettability of Industrial Surfaces: Contact Angle Measurements and Thermodynamic Analysis,” 1985) |

| Plastic | 72 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | 72 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | θ > 90° (Bourges-Monnier and Shanahan, 1995) |

| Paper | 3–5 | – | θ < 90°(Liukkonen, 2006) |

| Stainless steel | 48 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | 48 (Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | θ = 50° (Bernardes et al., 2010) |

2.3. Transmission mechanisms and prevention

Air filtration is different from liquid filtration and is the most common method for reducing airborne particles (Givehchi and Tan, 2014). Significant success in preventing the infection, has been achieved by decreasing the amount of some air contaminants such as dust, allergens, microorganisms, welding fumes and combustion-generated particles utilizing air filtration. It has been found that there is a direct association between high concentrations of airborne particles and human health disorders (Bulejko et al., 2016). Nowadays the mask's filter is constructed from layers of cotton gauze to prevent people from the aerosols. The important parameters in mask structure and its efficiency are fiber diameter, porosity, and filter thickness which can collect the particles. The fibrous of filters are responsible to capture particles by following mechanical collection mechanisms: internal impaction, interception, electrostatic attraction and diffusion (Fleeger & Lillquist, n.d.). Internal impaction/interception takes place when large particles cannot quickly pass with an airstream near the fiber, due to mass and inertia, and deposited into the mask's fiber. While diffusion is a mechanism in which small particles wander through random or Brownian motion and leave the airflow and attach to the surface and are significantly removed from the air: occurs for particles less than 0.1 μm (Mao, 2016). Electrostatic attraction is responsible for the removal of charged particles via attraction to charged fiber independent of particle size.

The bio airborne can occur during aerosol generating procedures, high temperature and low humidity conditions, not only in sneezing or coughing but also in speaking, and even in normal breathing. The University of Nebraska's evidence demonstrates that the SARS-CoV-2 distribution in isolated rooms can spread into the corridor (Santarpia et al., 2020). Other hand, by increasing the incubation temperature to 70 °C, the virus inactivation time was reduced to 5 min (Chin et al. n.d.). Therefore, even in hot and dry environments with the evaporation of the water layer, the virus can survive for several hours, and the issue of airborne transmission and filtering becomes more critical.

The prevention strategy for airborne environment conditions (high temperature and low humidity) is to provide high-quality masks for everyone. Ideally, a 0.1 μm filter would be more efficient for longer periods of protection to filter the aerosol of the virus. N95 masks means 95% filtration efficiency of aerosol particles at 0.3 μm, with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles being 0.06–0.14 μm in diameter (Worby and Chang, 2020). Basically, N95 and N100 masks may be appropriate if used for high-risk situations. Generally, the mask's effectiveness as source control depends on the mask's ability to trap or alter the emission of high pressure and its pathogenic payload (Bourouiba, 2020; (Chin et al. n.d.)).

On the other hand, droplet transmission may occur during close contact less than 2 m or droplets fall down on the surface and are touched by other people. The lifetime of a droplet on the surface depends on the evaporation rate and the droplet's contact angle on the surface explained before. Therefore, in the high humidity and low-temperature conditions, droplets are longer lasting. Social distancing and glove wearing are more effective in the situations that bio particles are spreading as droplet-born, but when viral particles travel as airborne in the low humidity and high temperature, then masking will restrain the transmission.

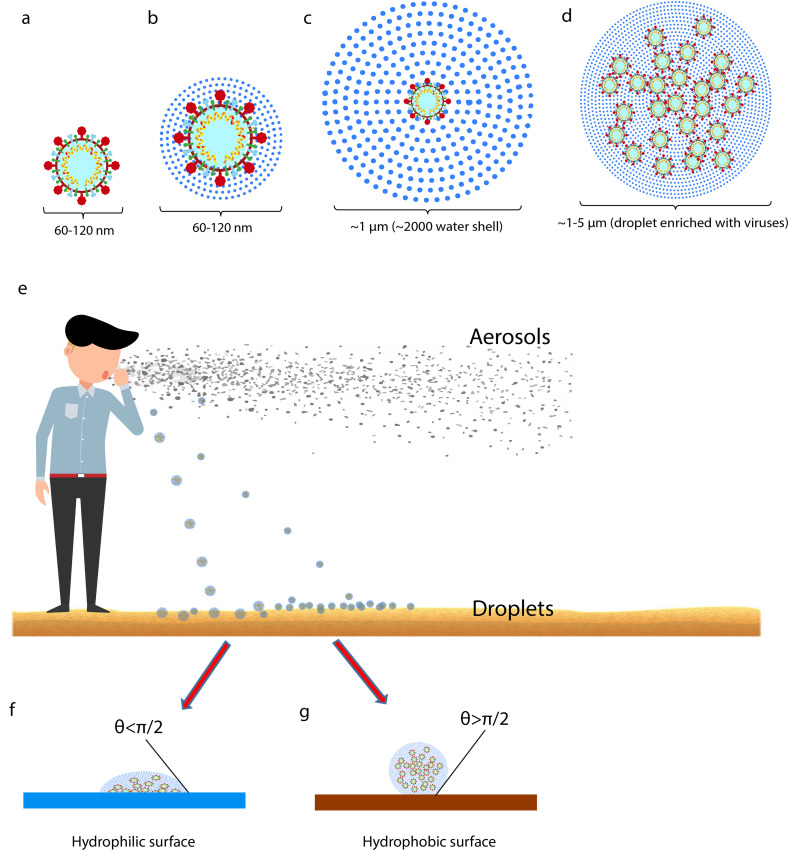

By considering the size of SARS-CoV-2 particles and its surrounding water molecules, the following schematic can be suggested for the droplet and aerosol (Fig. 1 ). It is assumed that the virus with a diameter around 60–120 μm (Fig. 1a) is the core of the droplet and its surroundings is water with molecular diameter about 2.75 A° and hydrogen bonding length 1.97 A° (Suresh and Naik, 2000). If the virus is only covered by a few layers of water molecules, there will be no significant change in diameter (Fig. 1b). Thus, a droplet with 1 μm diameter is surrounded with approximately 2000 water shells (Fig. 1c) and the higher diameter leads to higher hydrated water and likely containing more virus particles (Fig. 1d). Droplets weight and their flotation or deposition define them as airborne or droplet-born particles (Fig. 1e). The first and second shell of water can also be affected by electrostatic interaction between Spike protein and molecular dipoles (Hassanzadeh et al., 2020). It has been found that the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 has more positively charge than that of SARS-CoV-1 since it contains four more positively charged residues and five less negatively charged residues. This may result in an increased affinity to bind with negatively dipole of water and stronger than the positive dipole interactions (Hassanzadeh et al., 2020; Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry, 1979). Hence, the thermal energy for evaporation of the first and second shell of water in SARS-CoV-2 is higher than that of SARS-CoV-1, demonstrating that SARS-CoV-2 can remain for a longer time as aerosols without decomposition by exposure to sunlight. As soon as droplets land on the ground, they will form two types of array denoting as (Fig. 1f) and (Fig. 1g), which have the opposite angles and hydrophobicity.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of SARS-CoV-2 particles as droplets and aerosols. (a–b) SARS-CoV-2 particle diameter with or without few water shells ranges from 60 to 120 nm in diameter. (c) A virus particle enveloped by ~2000 water shells is about 1 μm in diameter. (d) A droplet containing more water molecules and several virus particles ranges ~1–5 μm. (e) Human sneezing and coughing generate a large number of aerosols and droplets. The large droplets fall on the ground more than the lighter ones. Aerosol particles would float on air and survive depending on temperature and humidity as the main factors. (f) A droplet on hydrophilic surfaces with θ<π/2. (g) A droplet on hydrophobic surfaces resulting in bigger contact angle (θ>π/2) and reducing the touch area.

2.4. Fecal-oral route of SARS-CoV-2 transmission

Previous studies have detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in various specimens, including sputum, BAL, nasal and pharyngeal swabs, fibrobronchoscopy brush biopsy, and feces (Morone et al., 2020; W. Wang et al., 2020). However, the information about SARS-CoV-2 RNA in blood and urine specimens is very controversial (Wölfel et al., 2020). In addition to common manifestations of COVID-19 disease such as pyrexia and cough, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain have been also reported in many patients (Guan et al., 2020; D. Wang et al., 2020). It was also revealed that these GI manifestations are more frequent in children compared to adult patients (Donà et al., 2020). Previous data have shown that the coronavirus trend to the gastrointestinal tract cells. Active viral replication of SARS-CoV-1 has been shown in both small and large intestines of infected patients (Leung et al., 2003) and viral RNA was detected in stool specimens (Hung et al., 2004). MERS-CoV has shown a similar pattern for infecting GI cells and it was found that this virus highly infects intestinal epithelial cells, and the viral genome is effectively expressed in this tissue (Hung et al., 2004; J. Zhou et al., 2017). Many studies have recently detected the SARS-CoV-2 RNA in feces samples of infected patients and viral RNA have been found in both rectal swabs and stool specimens of patients with COVID-19 (Xiao et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020c; W. Zhang et al., 2020). Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2020) showed 29% detection rate in feces specimens of COVID-19 patients. Wolfel et al. (Wölfel et al., 2020) showed high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral genome in feces specimens and found a highly direct correlation between viral RNA in sputum and stool specimens. More interestingly, they found that PCR test is still positive in many cases even after full resolution of symptoms and even three weeks later. Furthermore, based on their results, the replication activity of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI system is quite high. However, they could not isolate live virus from the stool. The detection rate for viral RNA in stool samples by PCR method is reported up to 53% of all confirmed cases in different studies (Tian et al., 2020). On the other hand, there is no correlation between positive COVID-19 test results in the stool with clinical manifestations and disease severity (Tian et al., 2020). As mentioned, viral RNA is detectable in these specimens even after the upper respiratory tract samples get negative (Peiris et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2020). Compared to the respiratory system, it seems that viral particles survive longer in the GI tract (Tian et al., 2020). The most important feature is that the gastrointestinal system is a potential target for SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication. Therefore, the frequent occurrence of diarrhea in patients infected with coronavirus may be explained by gastrointestinal tropism. It could be suggested that GI shedding might accrue abundantly and last longer even when the clinical manifestations disappear (Wong et al., 2020). The main human-to-human mechanism to transmit SARS-CoV-2 is droplets; however, stool shedding along with environmental contamination play a crucial role in viral spreading.

The presence of viral particles in stool makes it a potential source for fomite transmission via infective aerosols formation from the toilet plume (Yu et al., 2004). Besides, several studies revealed viral viability in environmental locations that possibly will affect fecal-oral transmission. Ong et al. (2020) showed in their study that SARS-CoV-2 could transmit via fecal route. They found that in the bathroom of COVID-19 patients with a RT-PCR positive fecal test, samples from different part of the bathroom such as the door handle, inside the bowl of the sink, and the surface of the toilet bowl is contaminated with the virus, and their PCR results for viral RNA are positive, while the results turned negative after cleaning. In another study, van Doremalen et al. (Van Doremalen et al., 2020a) found that after the formation of aerosols, the virus is viable for at least 3 h. They also showed that viable viruses exist for up to 2 or 3 days on stainless steel and plastic surfaces. Due to the high viral contamination of SARS-CoV-2, fecal transmission via exposure to fecal contaminated surfaces and fecal aerosols transmission must be considered as an important issue for the management, transmission and infection control of COVID-19 (Wong et al., 2020). It has been suggested that for diagnosis and to determine the isolation period especially in children, along with nasopharyngeal swabs, rectal swabs should also be tested (Wong et al., 2020).

3. Effects of nutrition and diet on immunity system, infections and COVID-19

The immune system uses numerous specialized cells, molecules, and functional responses to deal with threats from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. The immune system is always active to protect body health. The immune system's activity is extensively increased during an infection caused by any foreign organism. By advancing the immune system activity, the metabolism's level will improve, and the human body needs more energy supply, regulatory molecules, and various functional and bioactive compounds, which mostly should be obtained from the diet. Although all of the vitamins, minerals, amino acids, peptides and fatty acids are essential in supporting the immune system but some of the vitamins such as A, B6, B12, folate, C, D and E and the trace elements like zinc, copper, selenium and iron are crucial in reducing the various infections and harmonizing the immune system (Fig. 2 ). Among the nutrients above-mentioned, zinc and selenium have shown antiviral effects impact virus infection (Calder, 2020; Gómez et al., 2001; Hulisz, 2004). Therefore, it is necessary that individuals receive sufficient essential nutrients and bio-actives to strengthen their immune system and maintain their health to combat the pathogen, and any type of infection may be exposed.

Fig. 2.

Effects of vitamins, trace elements, gut microbiota, and Mediterranean diet on immune system function against COVID-19.

Another important component in regulating and protecting the immune system is the gut microbiota, as gut dysbiosis is an important factor in many infectious diseases has been described in Covid-19 (Tian et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2020).

3.1. Vitamins

Vitamin C is well known for its antioxidative activities, scavenging the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and, therefore, protecting the body cells against oxidative damage and supporting the healthy immune system. The level of vitamin C decreases during infections, especially in the older people, due to the nutritional deficiency of many nutrients, which is occurred mostly due to poor socioeconomic conditions, mental status, social status, and a host of other multifactorial issues (Castro-Mejía et al., 2020; Power et al., 2014; Volkert et al., 2020). Therefore, vitamin C and other nutrient demand will increase during infections, particularly in elderly populations, as the age itself is a risk factor for COVID-19 and other diseases (Zabetakis et al., 2020). Although several reports suggested using high dosage administration of vitamin C to achieve high levels in the body (Carr, 2020; Carr and Maggini, 2017), however, the finding of a research on 167 patients showed that high-dose intravenous vitamin C did not improve markers of organ dysfunction, inflammation or vascular injury (Fowler et al., 2019). Therefore, vitamin C may still improve sepsis and ARDS outcomes based on statistically significant improvement in 28-day mortality, hospital free days and ICU free days.

Vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc, similar to the nutrients with antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities, may prevent the inflammatory and vascular manifestations associated with COVID-19, however they require further significant studies and investigations (Zabetakis et al., 2020). Although plenty of reviews have been conducted on supplementation of vitamin C, it can also be obtained from regular food sources including fruit and vegetables such as citrus fruit, leafy greens, tomatoes, etc. As Zabetakis et al. (2020) and Hemilä (2017a) indicated, supplementation of 200 mg/day Vitamin C is beneficial, but above this threshold is unnecessary. However, this dosage is not sufficient for the elderly population and in cases with infection severity because they suffer from low levels of vitamin C.

Currently, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of vitamin C for healthful individuals is 75–90 mg/day (Compounds et al., 2000; Zabetakis et al., 2020). Since there is still a lack of clinical reports on COVID-19, the recommendation for vitamin C intake is limited. Meanwhile, the previous doses (1–2 g/day) have been useful to prevent the upper respiratory infections. However, if those doses cannot be obtained only from food sources; vitamin C supplementation could be advisable for individuals with a high risk of respiratory infection. The effect of vitamin C on the infection is likely due to the immunomodulatory activities including improving chemotaxis, enhancing neutrophil phagocytic capacity and oxidative killing and supporting lymphocyte proliferation and function, rather than a direct antiviral property (Carr and Maggini, 2017; Cinatl et al., 1995; Colunga Biancatelli et al., 2020; Dey and Bishayi, 2018; Leibovitz and Siegel, 1981). Moreover, vitamin C is a potent antioxidant, which directly scavenges the free radicals which may enhance the viral-induced oxidative injury (Colunga Biancatelli et al., 2020).

Vitamin D is another important vitamin (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3), which can be found in different food products, including eggs, mushrooms, and fatty fish such as salmon, as well as milk and dairy products or any fortified food with vitamin D but smaller amounts can be obtained from foods. There are several reviews on the impact of vitamin D on the immune system and its possible action in reducing the risk of respiratory tract infections (Grant, Baggerly, et al., 2020; Lanham-New et al., 2020). Since vitamin D receptors have been recognized in most immune cells and some of the other immune system cells can synthesize the active form of vitamin D from its precursor, it is probably to have important immunoregulatory properties. Moreover, vitamin D is reported to enhance epithelial integrity, induce antimicrobial peptide synthesis in epithelial cells and macrophages, and directly enhance host defense (Calder, 2020; Gombart, 2009).

The possible roles of vitamin D have recently been reviewed by Grant et al., 2020a, Grant et al., 2020b. Their findings have recommended that individuals with the risk of influenza and/or COVID-19 consider taking 10,000 IU/day of vitamin D3 for a few weeks to rapidly raise 25(OH)D concentrations, followed by 5000 IU/day. The goal should be to increase 25(OH)D concentrations above 40–60 ng/mL (100–150 nmol/L). Additionally, they proposed that higher vitamin D3 doses might help to treat the people infected with COVID-19. However, Lanham-New et al. (2020) rigorously caution against the doses above 4000 IU/day; 100 μg/day (upper limit); and indeed, of very high doses of 10,000 IU/day (250 μg/day), unless under personal medical and/or clinical advice by a qualified health expert. Therefore, a healthy lifestyle to avoid vitamin D deficiency, supplementation with vitamin D according to professional and government guidelines, following a nutritionally balanced diet, good exposure to the sunlight to boost the vitamin D are highly recommended. Appropriate diet and lifestyle measures are (as highlighted by the WHO) the leading healthy lifestyle and activities that support the immune system and protect the people against COVID-19. Furthermore, in a comment reported by Kow et al. (2020), they are also concerned with taking 10,000 IU/d of vitamin D3 for a few weeks to rapidly raise 25(OH)D concentrations, followed by 5000 IU/day recommended by some authors to overcome the risk of COVID-19 infection as there is not sufficient clinical evidence to support their recommendation. .

Vitamin A has also shown a remarkable effect on the immune system. Previously reported findings indicated that the mice with less vitamin A in their diet showed the destruction of the gut barrier as well as defective mucus secretion resulting in facilitating the entry of pathogens. Vitamin A and its derivatives are effective components in many aspects of innate immunity and barrier function. Furthermore, in vitamin A deficiency the phagocytic function of blood neutrophil and their ability to destroy the bacteria will be impaired. Therefore, natural killer cell activity and antiviral defenses are reduced due to vitamin A deficiency. Additionally, vitamin A deficiency can impair the response to vaccination (Hu et al., 2018; Ross, 1996).

Intestinal immune regulation and gut barrier function is one of the key roles of the B vitamins. B vitamins are obtained from dietary components and the gut microbiota, they then function in modulating host immune function. Mammals cannot synthesize B vitamins and must obtain them from dietary or microbial sources (Yoshii et al., 2019). Vitamins B6 and B12 and folic acid all support the activity of natural killer cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which are important in defense against viruses. Patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had low blood numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes and low natural killer cell activity (Tamura et al., 1999; Yoshii et al., 2019). In a study performed by Meydani et al. (1991), a diet with vitamin B6 deficiency for 21 days decreased the percentage and number of circulating lymphocytes, the T and B lymphocyte proliferation as well as the IL-2 production. Providing 2.362 mg/day vitamin B6 in a 70 kg individual for 4 days increased both lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production.

3.2. Trace elements

Several reviews and research have reported the impact of zinc on the immune system and human health regarding bacterial and viral infections (Hojyo and Fukada, 2016; Maares and Haase, 2016; Maywald et al., 2017; Prasad, 2008; Sprietsma, 1999; Wessels et al., 2017). Among the nutrients, zinc, and selenium have shown particular antiviral activities (Calder, 2020; Gómez et al., 2001; Hulisz, 2004). Therefore, it is needed that individuals receive sufficient essential nutrients and bio-actives to protect their immune system against any type of pathological invasion. Zinc as a trace element is vital in generating, modulating and controlling antiviral responses (Read et al., 2019). Zinc administration was effective in decreasing the duration and severity of common cold and influenza (Prasad, 2008). The viral infections have been positively affected by supplementation of zinc along with enough consumption of food rich in zinc (Solomons, 2001). SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is an essential enzyme for virus replication. It has been reported that zinc is able to inhibit the activity of RdRp, suggesting it may play a role in host defense against the infection (Kaushik et al., 2017).

Moreover, zinc showed good results in inhibiting SARS-CoVs and influenza viruses' replication in vitro ( Gammoh and Rink, 2017; Haase and Rink, 2009 ). Additionally, zinc is an important trace element in maintaining the number of lymphocytes. A lack or lower amount of zinc in the human diet, affects phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and natural killer cell activity of the immune system, as well as the B lymphocyte numbers and antibody production. A 30 mg daily intake of zinc supplementation amplified the T lymphocyte proliferation in elderly care home residents in the USA, which might be due to an increase in numbers of T lymphocytes (Calder, 2020; Prasad et al., 2007). Furthermore, recently reported findings indicated the impact of zinc on the duration of the common cold in adults and lower prevalence of pneumonia in children and adults' mortality (Coffin, 2013; Hemilä, 2017b; Lassi et al., 2016; Science et al., 2012).

Copper is also an essential trace element that is vital to support the immune system and the functions of neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes against different pathogens including bacteria and viruses. It has also been reported that Copper shows antimicrobial activities and promotes T-lymphocyte responses. Copper-deficient people have indicated high susceptibility to infections due to the malfunctions and lower number of critical immune cells (Raha et al., 2020; Sprietsma, 1999).

Infants and older people have shown more susceptibility to the deficiency of Copper. Infants with Cu-deficiency genetic disorders indicated severe and frequent infections (Failla and Hopkins, 1998; Percival, 1998; Raha et al., 2020). Furthermore, according to Raha et al. (2020) review, Copper can kill some viruses such as bronchitis virus, poliovirus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1(HIV-1), and different enveloped or nonenveloped, single- or double-stranded DNA and RNA viruses. Therefore, they have concluded that as this outbreak of the COVID-19 is still increasing, and there is no effective medicine or vaccine available, thus boosting the immune system and enrichment of plasma copper level is a useful option that might prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The other essential trace element is selenium. Numerous studies have shown that its deficiency is associated with loss of immunocompetence, and both cell-mediated immunity and B-cell functions can be compromised (Spallholz et al., 1990). Supplementation with selenium has improved the immunostimulant properties and improvement of activated T cell proliferation. Moreover, lymphocytes of individuals supplemented with selenium at a dosage of 200 μg/day showed an enhanced response to antigen stimulation (Kiremidjian-Schumacher et al., 1994; Rayman, 2000).

Selenium is an essential element for the physiological function of the immune system. Selenium deficiency has been shown to enhance viral mutations in different viruses such as coxsackievirus, polio virus and murine influenza virus (Beck et al., 2001; Beck and Levander, 2000).

According to the study, it seems selenium supplementation in the range of 100–300 μg/day improves various aspects of humans' immune function (Graat et al., 2002; Hawkes et al., 2001; Peretz et al., 1991). However, selenium supplementation of 50 or 100 μg/day in the UK with low selenium status improved some aspects of the immune response to a poliovirus vaccine (Broome et al., 2004; Calder, 2020).

3.3. Gut microbiota, immune system and COVID-19

Another important element in regulating and protecting the immune system is the gut microbiota. Gut dysbiosis, is an element in many infectious diseases, including COVID-19, has been described (Tian et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2020).

Cytokine storm is a prevalent symptom that has been reported in many cases of COVID-19, and is characterized by extensive and harmful inflammation due to severe infection of the respiratory epithelium, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Several studies have indicated that the n-3-fatty acids can control cytokine storms, probably by the metabolism of fatty acids to their effective pro-resolving mediators (Bursten et al., 1996; García de Acilu et al., 2015).

Several research studies showed that up to 20% of COVID-19 patients exhibited GI symptoms, including diarrhea (Chen et al., 2020; Cheung et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Zuo et al., 2020). As previously explained in this review, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been detected in stool samples of about 50% of COVID-19 patients. Therefore, the digestive tract could be an important site for virus replication and activity (Wölfel et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020c; Zuo et al., 2020). Zuo et al. (2020) performed shotgun metagenomics sequencing analyses of faecal samples and found persistent alterations in the faecal microbiome. Furthermore, faecal microbiota alterations were associated with SARS-CoV-2 load and COVID-19 severity. Thus, they suggested that strategies to modify the intestinal microbiota might ameliorate the severity of disease.

Therefore, dietary strategies to attain a healthy microbiota can also support the immune system to defend better against bacterial and viral infections, including COVID-19. Several studies indicated that probiotic bacteria such as some lactobacilli and bifidobacteria could alter the microbiota and protect against different infections. Additionally, some plant foods, fiber and fermented foods play a role in creating and maintaining a healthy gut microbiota and would support the immune system (Dhar and Mohanty, 2020; Schiffrin and Donnet-Hughes, 2011).

3.4. Support the immune system through good diet

People's nutritional conditions can have a considerable effect on the individual's health, their resistance level against infection, and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (Zabetakis et al., 2020). Although, suitable nutrition, an individual's health status, and a healthy diet clearly have a key role in the patient's immune response infected by different viruses. There are plenty of foods, diets and nutrients with no immunosuppression, which have been previously reported for their valuable biological activities including immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory against diseases such as lung diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and NCDs (Andersen et al., 2016; Butler and Barrientos, 2020; Khayyatzadeh, 2020; Prasad, 2008; Walker and Black, 2004; Wessels et al., 2017; Zabetakis et al., 2020). However, there are no proven treatment strategies, or any single food approved by the WHO prohibiting the occurrence of the COVID-19 infections before this time. Moreover, the new findings and the previously reported results related to the healthy diet and nutrition and their impact on the viral infections will be discussed in the following subtopics.

Calder (2020) tabulated some foods associated with the essential nutrients as shown in Table 2 . He recommended that the best diet to support the immune system is an intake diet with various types of vegetables, fruits, berries, nuts, seeds, grains and pulses, and some meats, eggs, dairy products, and oily fish. Furthermore, based on the study performed by Gibson et al. (2012), he recommended the consumption of fruits and vegetables in more than 5 servings per day, particularly in older people with the age range between 65 and 85 years, to a better immune response to pneumococcal vaccination.

Table 2.

Important dietary sources of nutrients that support the immune system. The reference daily intakes (RDIs) are for healthy individuals. The RDI for infants, children and lactating women is different which should be consulted with the physician. Adopted from Calder (2020).

| Nutrient | Dietary Source | Main Roles on The Immune System | Reference Daily Intake (RDIs) in Adults and Children≥ 4 Years According to FDA | Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) Per Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Milk and cheese, eggs, liver, oily fish, fortified cereals, dark orange or green vegetables (e.g., carrots, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, squash, kale, spinach, broccoli), orange fruits (e.g., apricots, peaches, papaya, mango, cantaloupe melon), tomato juice | Vitamin A has both promoting and regulatory roles on the innate immune system and adaptive immunity; therefore, it can enhance the organisms' immune function and provide enhanced defense against multiple infectious diseases. Its deficiency is associated with the impaired barrier, function, altered immune responses, and increased susceptibility to a range of infections (Z. Huang et al., 2018) (Z. Huang et al., 2018) | 900 mcg | 3000 mcg Institute of Medicine et al. (2002) |

| Vitamin B6 | Fish, poultry, meat, eggs, whole grain cereals, fortified cereals, many vegetables (especially green leafy) and fruits, soya beans, tofu, yeast extract | Cell-mediated immunity and, to a lesser extent, humoral immunity are being affected by Vitamin B6 deficiency in both animal and human studies. Its intake or supplementation improves some immunological parameters in vitamin B6-deficient animals and humans(Van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | 1.7 mg | 100 mg (Haugen et al., 2018; Stover and Field, 2015) |

| Vitamin B12 | Fish, meat, some shellfish, milk and cheese, eggs, fortified breakfast cereals, yeast extract | The phagocytic and bacterial killing capacity of neutrophils is decreased by Vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamins B6, B12, and folate all support the activity of natural killer cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, effects which would be important in antiviral defense. Patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had low blood numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes and low natural killer cell activity (Calder, 2020) | 2.4 mcg | 4 mcg (NDA, 2015) |

| Folate | Broccoli, brussels sprouts, green leafy vegetables (spinach, kale, cabbage), peas, chickpeas, fortified cereals | Folic acid, the synthetic form of folate, plays an important role in cell division and cell production in blood-forming organs and bone marrow. Many studies recommend that adequate dietary levels of folic acid and B12 can act as preventative measures for inflammation, immune dysfunction, and disease progression (Alpert, 2017; Mikkelsen and Apostolopoulos, 2019; van Doremalen et al., 2020b) | 400 mcg | 1000 mcg (Sawaengsri et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2018; World Health Organization & FAO, 2004) |

| Vitamin C | Oranges and orange juice, red and green peppers, strawberries, blackcurrants, kiwi, broccoli, brussels sprouts, potatoes | Vitamin C contributes to immune defense by supporting various cellular functions of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Vitamin C supports epithelial barrier function against pathogens. It also has roles in several aspects of immunity, including leukocyte migration to infection sites, phagocytosis and bacterial killing, natural killer cell activity, T lymphocyte function (especially CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes), and antibody production. People deficient in vitamin C are susceptible to severe respiratory infections such as pneumonia (Calder, 2020; Carr and Maggini, 2017). | 90 mg | 2000 mg (Hemilä and Chalker, 2020; Institute of Medicine et al., 2002; Levine et al., 1998) |

| Vitamin D | Oily fish, liver, eggs, fortified foods (spreads and some breakfast cereals) | Vitamin D is able to modulate innate and adaptive immune responses. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased autoimmunity and increased susceptibility to infection. Vitamin D supplementation can reduce the risk of respiratory tract infections and reduce influenza risk during winter. Besides, avoidance of severe vitamin D deficiency improves immune health and decreases susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. (Bouillon, 2017; Calder, 2020; Martens et al., 2020) | 20 mcg | 100 mcg (Bouillon, 2017; Martens et al., 2020; Pludowski et al., 2018) |

| Vitamin E | Many vegetable oils, nuts and seeds, wheat germ (in cereals) | Immunomodulatory effects of vitamin E have been observed in animal and human models under normal and disease conditions. With advances in understating the development, function, and regulation of dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, T cells, and B cells, recent studies have focused on vitamin E's effects on specific immune cells (Lee and Han, 2018). Vitamin E supplementation of the diet of laboratory animals enhance antibody production, lymphocyte proliferation, T helper 1-type cytokine production, natural killer cell activity and macrophage phagocytosis. Moreover, vitamin E promotes interaction between dendritic cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes (Calder, 2020) | 15 mg | 1000 mg (Institute of Medicine et al., 2002; Jansen et al., 2016) |

| Zinc | Shellfish, meat, cheese, some grains and seeds, cereals, seeded or whole-grain bread | Zinc deficiency has a remarkable effect on bone marrow, decreasing the number of immune precursor cells, reduced naive B lymphocytes' output causes thymic atrophy, and reduces naive T lymphocytes' output. Therefore, zinc is vital in maintaining T and B lymphocyte numbers. Zinc deficiency impairs many aspects of innate immunity, including phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and natural killer cell activity. Zinc also supports the release of neutrophil extracellular traps that capture microbes.115 There are also marked effects of zinc deficiency on acquired immunity. Circulating CD4+ T lymphocyte numbers and function (e.g., IL-2 and IFN-γ production) are decreased, and there is a disturbance in favor of T helper 2 cells. Likewise, B lymphocyte numbers and antibody production are decreased in zinc deficiency (Gammoh and Rink, 2017; Hojyo and Fukada, 2016) | 11 mg | 50 mg (R. S. Gibson and Anderson, 2009; World Health Organization & FAO, 2004) |

| Selenium | Fish, shellfish, meat, eggs, some nuts, especially brazil nuts | Selenium deficiency in laboratory animals adversely affects several innate and acquired immunity components, including T and B lymphocyte function, including antibody production, and increases infection susceptibility. Lower selenium concentrations in humans have been linked with diminished natural killer cell activity and increased mycobacterial disease (Avery and Hoffmann, 2018; Cheng and Sandeep Prabhu, 2019; Hatfield et al., 2006) | 55 mcg | 400 mcg (Cheng and Sandeep Prabhu, 2019; World Health Organization & FAO, 2004) |

| Iron | Meat, liver, beans, nuts, dried fruit (eg, apricots), whole grains (e.g., brown rice), fortified cereals, most dark green leafy vegetables (spinach, kale) | Iron exhibits important effects on immune cell function and differentiation, and fourth almost every immune activation, in turn, impacts iron metabolism and spatiotemporal iron distribution (Haschka et al., 2020). The role of iron in immunity is in immune cell proliferation and maturation, specifically lymphocytes, associated with generating responses to infection(Alpert, 2017; Haschka et al., 2020) | 18 mg | 45 mg (Schümann et al., 2002; World Health Organization & FAO, 2004) |

| Copper | Shellfish, nuts, liver, some vegetables | Copper supports neutrophil, monocyte, and macrophage function and natural killer cell activity. It promotes T lymphocyte responses such as proliferation and IL-2 production. Copper deficiency in animals impairs a range of immune functions and increases susceptibility to bacterial and parasitic challenges (Calder, 2020). Cu can kill several infectious viruses such as bronchitis virus, poliovirus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1(HIV-1), other enveloped or nonenveloped, single- or double-stranded DNA and RNA viruses (Raha et al., 2020) | 0.9 mg | 10 mg Institute of Medicine et al. (2002) |

| Essential Amino Acids | Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, milk and cheese, soya, nuts and seeds, pulses | Amino acid metabolism plays a key role in this metabolic rewiring, and it supports various immune cell functions beyond increased protein synthesis. Immune cells critically depend on such pathways to acquire energy and biomass and to reprogram their metabolism upon activation to support growth, proliferation, and effector functions (Cruzat et al., 2018; Kelly and Pearce, 2020; Raha et al., 2020) | – | |

| Essential Fatty Acids | Many seeds, nuts, and vegetable oils | Clinical signs of essential fatty acid deficiency include a dry scaly rash, decreased growth in infants and children, increased susceptibility to infection, and poor wound healing | Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR) - Total fat is 20–35 E% - linoleic acid: 5 to 10 E% - α-linolenic acid) 0.6 to 1.2 E% - (NDA, 2010) |

|

| Long Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Oily fish | This family of polyunsaturated fatty acids exerts major alterations on the activation of cells from both the innate and the adaptive immune system, although the mechanisms for such regulation are diverse | The FDA recommends that the intake for consumers not exceed 3 g/day of combined EPA and DHA, with no more than 2 g/day from dietary supplementation (51). However, according to EFSA Panel on Dietetic Product (52),long-term consumption of EPA and DHA supplements at combined doses of up to about 5 g/day and supplemental intakes of EPA alone up to 1.8 g/day, appears to be safe. Additionally, available data are insufficient to establish a UL for the omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC–PUFA), individually or combined, for any population group | |

| Got microbiota | A plant-based diet, fiber, and fermented food including yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, tempeh | Indigenous commensal bacteria within the gastrointestinal tract are believed to play a role in host immune defense by creating a barrier against colonization by pathogens. Improving gut microbiota profile by personalized nutrition and supplementation are known to improve immunity can be one of the prophylactic ways by which infectious diseases can be minimized in older people and immune-compromised patients (Childs et al., 2019). | – | |

3.5. Effects of micronutrients combination on immune system

Micronutrient deficiency hinders immune function by affecting the innate T-cell mediated immune response and adaptive antibody response. As discussed before, the micronutrients, including elements such as copper, zinc, selenium, iron, and vitamins such as vitamin A, C, E, B6, and folic acid, significantly influence the immune responses. Availability of one nutrient may either decrease or enhance another nutrient's function on the immune system. Although many studies have been performed on the interactions between nutrients, further research is needed to improve our knowledge in this area. A nutrient-nutrient interaction may negatively affect the immune function; for instance, an excess amount of calcium interferes with leukocyte function by displacing magnesium and reducing cell adhesion (Kubena & McMURRAY, 1996).

In a study by Tan et al. (2005), the effects of α-tocopherol alone or in combination with vitamin C, was investigated on the phenotype and functions of human dendritic cells (DCs) generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. The results indicated that expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, CD40 CD80, and CD86 appeared to be increased when exposed to a low concentration of vitamin E (<0.05 mM), but the combination of vitamin E and C prevented DC activation. In another study, Raposo et al. (2017) investigated the effect of vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, zinc, and polyunsaturated fatty acids on upper respiratory tract infection. Their findings showed a negative association between upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) incidence and vitamin C, vitamin E, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and arachidonic acid (AA) intake in female subjects. While there was a positive association among men for vitamin E and zinc intake (Fuente et al., 1998). The authors also reported an increase in both phagocytosis and oxidant generation following supplementation of elderly participants with a combination of vitamins C and E.

The synergism effect of vitamin A and Zn was indicated in a study by Li and Li (2007). They observed significantly higher proliferation and lower apoptosis levels in cells co-administered with Zn and vitamin A compared to their single-use (P < 0.05). Therefore, different parameters such as dose of nutrients, age, and gender should be taken into consideration in combination therapy of nutrients. Regarding the impact of nutrient combination therapy on the immune system, the existing data is controversial; some evidence indicates that combination therapy results in antagonism, while others reveal the effects of nutrients' synergism. Therefore, any kind of supplementation, either single-use or combination therapy should be recommended by experts in the field and by government authorities.

3.6. Dietary patterns, immune system and COVID-19

A nutritious diet with sufficient amounts of efficient compounds and a healthy microbiota can boost and support the immune system. Mediterranean diet contains relatively high dietary intake of various fresh or minimally processed foods such as fruit, vegetables, legumes, monounsaturated oils like olive oil, whole grains, nuts, as well as low-to-moderate fermented dairy products fish, poultry, wine, and low consumptions of processed and red meats (Razquin and Martinez-Gonzalez, 2019; Zabetakis et al., 2020). The food associated with the Mediterranean and similar diets contain very significant bioactive compounds, including vitamins, minerals, phenolic and bioactive peptides with different bio-functional activities. Therefore, such beneficial diets are potentially effective against infections such as COVID-19 due to their effects on the immune system (Gentile and Weir, 2018; Shah et al., 2020; Zabetakis et al., 2020).

In contrast to the Mediterranean diet, the Western diet is characterized by consuming processed foods such as cured and red meat, sausages and salami, high consumption of sweets, desserts, deep-fried, and high-fat food products. Therefore, this diet is linked to hyperglycemia, which is associated with high mortality in COVID-19 patients (Li et al., 2020b) as well as hyperlipidemia and, consequently, high prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Hence, this population is potentially more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection (Butler and Barrientos, 2020; Li et al., 2020b; Sergi et al., 2020; Zabetakis et al., 2020).

4. Cellular mechanisms of virus cell entry and genetics factors affecting SARS-CoV-2 spreading and severity

4.1. Cellular pathways for SARS-CoV-2 -host cells interaction and entry mechanisms

The crucial step for viral infection is the process of viral particles binding and entering host cells. Understanding the mechanism of entry is a key step for finding effective therapeutic targets for the treatment of viral infection.

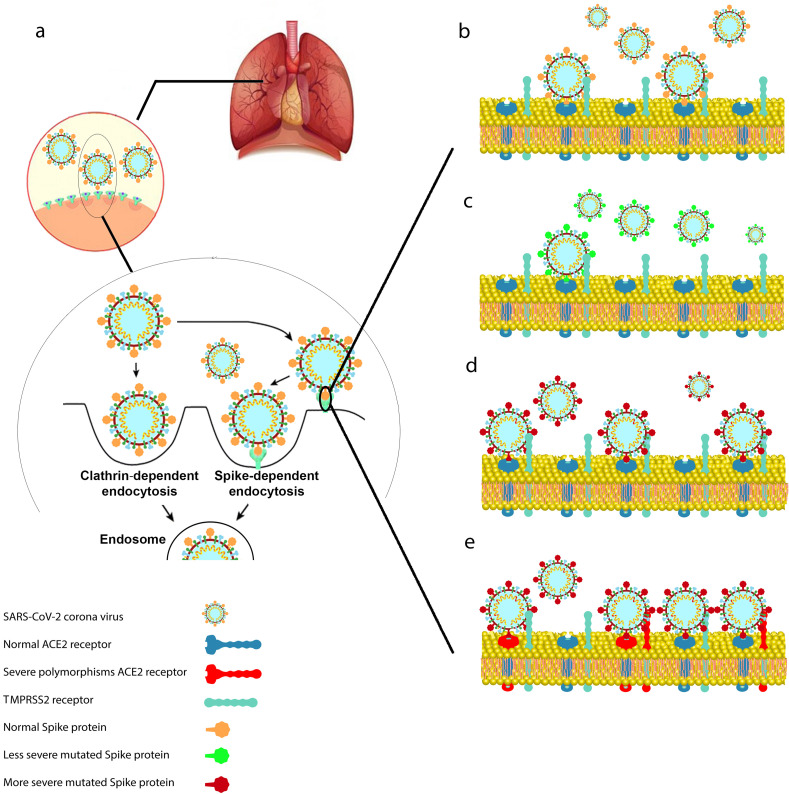

The entry of enveloped viruses into the cells has been documented to occur through two main pathways: in the first route of entry; the virus transfers its genomes to the cytosol following its binding to the cell surface receptor and the virus envelopes fuse with the plasma membrane at the host cell surface. While the second pathway benefits from the endocytic components of the host cell (Fig. 3 a). In this mechanism, the endocytosed virions are activated in the endosome, which is generally mediated by the acidic endosomal pH, causing the fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes and release of the viral genome into the cytosol (Wang et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms for cell entry and possible genetic mutations in Spike protein and host receptors. (a) Possible cellular pathways for cell entry, including Spike-dependent or clathrin-mediated endocytosis. (b) Wild-type Spike protein and ACE2 receptor and their interaction. (c) Possible mutation in Spike protein which results in weaker interaction between Spike protein and ACE2 receptor. (d) A condition in which the mutation in the virus Spike protein but not ACE2 increases their interaction and eventually elevates the infection rate. (e) Possible mutations in Spike protein and ACE2 host genetic polymorphism may lead to a higher affinity, infection rate and more severe disease.

Spike protein is the coronaviruses ‘key player’ for infection of host cells via strong binding to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE2) and other cell receptors (Li et al., 2005a; Xu et al., 2020b). However, coronavirus SARS-CoV-1 cell entry mediated by Spike protein reviewed elsewhere (Belouzard et al., 2012). It has been shown that Spike protein structure and its function is highly important for cell infection in different tissues (Belouzard et al., 2012; K. Wu et al., 2012).

The Spike protein is a homotrimer; each monomer contains a receptor binding domain which sticks out from the viral membrane and facilitates the viral interaction with the ACE2 receptor in the host cell's plasma membrane (Yan et al., 2020) (Sun et al. n.d.) (Baig et al., 2020; Ortega et al., 2020). Virion particle needs a series of protease cleavage on the Spike protein to remove the S1 domain and expose the S2 domain containing the fusion peptide (FP) and heptad repeats (HR1 and HR2) for fusion to the cell membrane and entry to the cytoplasm.

For membrane fusion of virus particles, coronavirus Spike protein must go through several cleavages at S1/S2 site and S2 site in order to be able to bind ACE2 receptor. Virus entry through membrane fusion is 100–1000 -fold more efficient than the endosomal entry pathway (Matsuyama et al., 2005). Some proteases including Furin (Shuai Xia et al., 2020), TMPRSS2 (Hoffmann, Kleine-Weber and Pöhlmann, 2020) (Hoffmann, Kleine-Weber, Schroeder, et al., 2020; Kawase et al., 2012) (Walls et al., 2020), and TMPRSS4 (Zang et al., 2020) have been confirmed to facilitate virus entry into the cells. Also, cathepsins play an important role when other proteases are not expressed by the target tissue and mediate the endosomal entry pathway (Bertram et al., 2011; Zang et al., 2020). In the cells expressing TMPRSS2, SARS-CoV virions still rely on endosomal cathepsin for entry. In fact, both TMPRSS2 and Cathepsin B/L proteases are crucial for efficient cell entry and blocking protease activity. Specific blockers including camostat mesylate and E−64d (cathepsin inhibitor) could interfere with cell entry of SARS-CoV virion (Hoffmann, Kleine-Weber, Schroeder, et al., 2020) (Kawase et al., 2012).

Researchers mutated the novel proprotein convertase (PPC) motif of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and found that removing Furin cleavage site significantly reduces the efficiency of cell entry (Shang, Wang et al., 2020). Overall, it seems that TMPRSS2, TMPRSS4 and cathepsins have synergistic effects with FURIN on activating SARS-CoV-2 entry into different cell types (Kawase et al., 2012). For therapeutic purposes, protease inhibitors have to target all of the proteases for efficient blocking of the virus entry, which seems an unrealistic approach, because blocking of these proteases could also interfere with cell function. Cleavage of virions surface Spike protein before their binding to the cell (ACE2 receptor) would probably minimize infection by inactivating the virion and should be a better target for potential therapeutics (Corrêa Giron et al., 2020).

Spike protein binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor is also important for internalization of SARS-CoV-2 virus and pathogenesis. More recently, several groups demonstrated that the affinity of the ACE2 to the RBD in the Spike protein is more than 10–30 fold higher in SARS-CoV-2 compared to SARS-CoV-1 (Shang et al., 2020a; Shang et al., 2020b) (Hoffmann, Kleine-Weber, Schroeder, et al., 2020) (Lan et al., 2020) (Vandelli et al. n.d.) (Wrapp et al., 2020). However, the efficiency of the entry to different cell types remains the same as SARS-CoV-1 due to less accessibility of RBD in SARS-CoV-2 (Ou et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020a).

Co-expression of ACE2 and proteases involved in cell entry, have been shown in the bronchial secretory cells in lungs (Lukassen et al., 2020), conjunctiva epithelial cells of cornea (Ma et al., 2020), arteries, heart, kidney, intestines (Zang et al., 2020) and brain (Doobay et al., 2007). Being ACE2 receptor exposed on the surface of several cell types including the respiratory tract epithelium, the lung parenchyma and other areas such as the gastrointestinal tract, endothelial cells, and among others the brain (Li et al., 2020c), the virus can potentially reach several organs.

Endocytic pathways including endosome, lysosome, and the autophagy process have attracted considerable attention in viral entry in the last decade. These pathways have the potential to be the therapeutic targets in combating diseases caused by viruses (Yang and Shen, 2020).

Although, the clathrin-dependent endocytosis/exocytosis (Fig. 3a) has been reported as the most important pathway for some viruses entering the host cells such as Hepatitis C virus, Tick-borne encephalitis virus and Zika virus which induce neuroinfection (Jorgačevski et al., 2019; Zorec et al., 2019). Whether SARS-CoV-2 enters the cells and infects the organs by this mechanism has yet to be elucidated. There are other types of coronavirus such as swine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (HEV), which employs endocytosis as the main pathway for its trans-synaptic transfer in the neuronal system (Li et al., 2013).

The clathrin-dependent endocytosis (Fig. 3a) is a transportation mechanism for viruses to enter the host cell in an endosome form (Savarino et al., 2003). Intracellular lysosome leads to rupture of the endosome and release of the viral contents (Savarino et al., 2003). Hydroxychloroquine has been shown to accumulate in lysosomes, interfering the usual process of lysosome/endosome fusion, thus preventing the viral contents release (Golden et al., 2015; Morozov, 2020). Chloroquine is also shown to raise the pH level of the endosome, which may inhibit virus entry to the host cells (Vincent et al., 2005). With regard to the controversy on the susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 to the inhibitory effect of Hydroxychloroquine, it is possible that this novel coronavirus employs other pathways for entry into the host cells. However, recent studies indicate that Hydroxychloroquine may also reduce glycosylation of ACE2, therefore inhibiting virus/ACE2 interaction (Devaux et al., 2020). In addition, the immunomodulatory effects of Hydroxychloroquine have been proposed recently as the main mechanism of action instead of prevention of cell entry in cell models (Li et al., 2020a).

Considering our previous computational assay, we suggest that Spike protein dependent pathway may play a greater role than clathrin-dependent endocytosis for SARS- CoV-2 cell entry. Therefore, Spike dependent pathways should be taken into account as the main target for therapeutic strategies (Hassanzadeh et al., 2020).

4.2. Human host genetic background and SARS-CoV-2 polymorphisms, key factors in COVID-19 infection and severity of the disease

Genetic background and polymorphism in the population, affects the vulnerability and susceptibility to infection caused by coronavirus and other types of pathogens (Carter-Timofte et al., 2020; Casanova and Abel, 2018). An study on the UK Biobank genomic data and people who had been tested positive for COVID-19, revealed a direct relationship of ethnicity and different genetic background with the severity level of COVID-19 infection (McQueenie et al., 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative is a global effort to analyze the genomic data generated by the human genetics community to reveal the genetic factors and polymorphisms involved in COVID-19 susceptibility and severity (COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, 2020). These studies will help the global understanding of the outbreak and categorize individuals and populations to higher or lower risk groups. The effect of the host genetics background on the susceptibility to infectious diseases including COVID-19 has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (Kwok et al., 2020; LoPresti et al., 2020).

It has been investigated that genetic variation in histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I genes is also involved in being more vulnerable to COVID-19 (Nguyen et al., 2020). Nguyen et al. pointed out that people carrying HLA-B*46:01 allele show lower immunity development against COVID-19, while the HLA-B*15:03 allele highly represents the corona protein to the immune cells and makes the carrier more tolerant to the disease (Nguyen et al., 2020).

It has been shown that some genetic polymorphisms in ACE2 could make it more potent to have stronger binding interactions with the Spike protein (Cao and Li, 2020). The level of Spike protein affinity in SARS-CoV-1 to ACE2 is significantly dependent on the special amino acid residual on both proteins involved. It had been confirmed that different variants of ACE2 indicate different affinity levels to the Spike protein variants (Li et al., 2005b). Asian males have been shown to express more ACE2 and there is a possibility that they have a greater risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (Zhao et al., 2020).

Mutations in the Spike protein cleavage sites contribute directly to the activation of Spike, its binding affinity to the cell receptors and pathogenesis of the virus. Italian population genetics analysis suggested the possible correlation of TMPRSS2 variants with the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy (Asselta et al., 2020).

It is expected that any type of polymorphisms in Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, its receptor ACE2 and the involved proteases and also the immunity response genes would affect the infection rate and severity of the COVID-19 illness. In the most common situation, SARS-CoV-2 and the host cells have a normal binding affinity of protein-protein interaction (Fig. 3b). In some cases, new mutations in the Spike protein, might result in less or higher binding affinity to its receptor on the host cells (Fig. 3c and d). However, the coincidence of new mutations in the Spike protein and host genetic polymorphisms at the individual or population level might cause strong affinity between the virus and the host cells (Fig. 3e). In this scenario, the infection and spread rate of the disease might be higher in comparison to the normal situation. The most known SARS-CoV-2 mutation called D614G in which the amino acid number 614 in the Spike protein changed from Aspartic acid to Glycine (Korber et al., 2020) has become dominant mutant across the world. Mutated Spike D614G showed less infectious titres in the lung of hamsters but higher in nasal washes and the trachea. This is on par with the clinical observation where the patients infected with mutated virus carry more viral particles in the nose and mouth resulting in faster spreading of the virus (Plante et al., 2020). This mutation was also reported to cause a higher fatality rate (Becerra-Flores and Cardozo, 2020; Korber et al., 2020; Plante et al., 2020).

Some new variants of SARS-CoV-2 originating in mink have been reported to infect humans in Denmark (Hammer et al., 2020). This mutation called the Cluster 5 variant, showed the possibility of transmission from mink to the farmers and also transfer human to human (WHO, 2020). The transmissibility and severity of this new variant does not seem to be more than other SARS-CoV-2 variants, however more investigations are needed to evaluate the efficacy of the approved and currently in development vaccines, on this new cluster of the virus.

5. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2

Previous knowledge about the genome, structure and function of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS, as well as rapidly available genome information of SARS-CoV-2, enabled scientists to accomplish a remarkable achievement in the development of COVID-19 vaccines in a very short time frame (Krammer, 2020; Li et al., 2020d). Various approaches and platforms have been suggested to provide promising COVID-19 vaccines. As of March 2021, twelve different vaccines have been developed based on four main strategies comprising: RNA vaccines, conventional inactivated vaccines, viral vector vaccines and protein subunit vaccines (Rawat et al., 2021; Shrotri et al., 2021). Considering the pivotal role of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, which was described in detail before, most of the current vaccine design strategies target this primary antigen (Dai and Gao, 2021). Here, we briefly describe vaccines categories based on the structure and mechanism of action and give some examples of each type of vaccine that have been developed against SARS-CoV-2.

5.1. RNA-based vaccines

RNA-based vaccines are known as one of the next-generation vaccine technologies which prevents pathogen or cancer cells through encoding one of the main and unique antigens of pathogen or cancer cells. Once the mRNA vaccine is taken by dendritic cells and translated by the host cell, the antigen can then be presented to T cells and B cells and stimulate the adaptive immune system (Le et al., 2020). This type of vaccine has several beneficial aspects such as self-adjuvant properties, faster production process with lower rate of error and manufacturing cost, and no risk of infection and integration into the host genome (Xu et al., 2020a). Modified nucleosides such as pseudouridine, N1-methyl-pseudouridine (m1Ψ) and 5-methylcytosine are the building blocks of most RNA-based vaccines (Karikó et al., 2005). These modifications and various carrier molecules (such as lipid nanoparticles and antifreeze materials) protect the fragile mRNA structure and increase its half-life and stability (Aldosari et al., 2021). Despite these modifications, RNA-based vaccines should be stored at extremely cold temperatures to avoid degradation and this is the main drawback of this class of vaccines (Meo et al., 2021). Pfizer–BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) vaccines are examples of RNA-based vaccines encoding Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 with clinical efficacy of 95% and 94% respectively (Baden et al., 2021; Polack et al., 2020).

5.2. Inactivated vaccines

Inactivated vaccines are composed of physically (using heat or radiation) or chemically (using formaldehyde) inactivated virus particles. These virus particles are unable to cause disease, but they can stimulate immune response. Inactivated vaccines are safer than live attenuated vaccine (LVA), but they have lower immunogenicity than LVAs. Therefore, multiple doses of inactivated vaccines and adjuvants are required for more effective immune response. Inactivated vaccines have incomplete induction of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Jeyanathan et al., 2020). BBIBP-CorV, CoronaVac, Covaxin, and CoviVac are four authorized inactivated vaccines so far. In phase III clinical trials BBIBP-CorV vaccine had 86% efficacy, and for CoronaVac, and Covaxin the efficacy was 78% and 81% respectively (Ella et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021).

5.3. Non-replicating viral vector vaccines

Several viral vector vaccines have been developed based on human or non-human replication-defective adenovirus serotypes. Adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5), adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) and Chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAd) vectors are among commonly used adenovirus vectors against SARS-CoV-2 (Belete, 2020). These adenovirus vectors are genetically engineered, and they express SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Chilamakuri and Agarwal, 2021; Jeyanathan et al., 2020). Sputnik V (using Ad5 and Ad26), Convidicea (using Ad5), and the Johnson & Johnson vaccines (using Ad26) are human based adenovirus vectors. Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine is based on Chimpanzee adenovirus vectors and this vaccine has less seroprevalence in comparison with Ad5 and Ad26 (human based adenovirus) (Zhang et al., 2013). The key advantages of viral vector vaccines are that one-shot vaccines provide immunity and have long-term stability under normal fridge storage temperature and vaccine can be delivered directly to the respiratory tract (Putter, 2021). The major drawback of adenovirus vector vaccines is pre-existing immunity toward the viral vector backbone that could eradicate the vaccine particles before the immunity is established (Zhu et al., 2020). Clinical phase III studies indicated that the efficacy of approved viral vector vaccines are 91% for Sputnik V, 81% for Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine, 65.7% for Convidicea, and 64–77% for Johnson & Johnson vaccine (Logunov et al., 2021; Mahase, 2021; Stephenson et al., 2021; Voysey et al., 2021).

5.4. Protein subunit vaccines (PSVs)