Abstract

At the end of 2019, the new coronavirus caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) suddenly raged, bringing a severe public health crisis to the world. It is urgent to discover suitable drugs and treatment regimens against this coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and related diseases. Based on the previous knowledge and experience in treating similar diseases, researchers have come up with hundreds of possible drug candidates in the shortest possible time. Based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology, this review summarized the application of SPR technology in COVID-19 research from four aspects: the invasion mode of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells, antibody drug candidates for the treatment of COVID-19, small molecule drug repurposing and vaccines for COVID-19. SPR technology has gradually become a powerful tool to study the interaction between drugs and targets due to its high efficiency, automation, labeling-free and high data resolution. The use of SPR technology can not only obtain the affinity data between drugs and targets, but also clarify the binding sites and mechanisms of drugs. We hope that this review can provide a reference for the subsequent application of SPR technology in antiviral drug development.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Coronavirus disease 2019, Surface plasmon resonance technology, Invasion mode, Antiviral drug development

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that broke out at the end of 2019 quickly evolved into a global public health emergency in the next few months. As of May 4, 2021, there have been more than 151 million people diagnosed with the new coronavirus, and the death toll exceeds 3 million [1].

Coronavirus (CoV) is a class of positive-sense single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus with envelope. It belongs to the genus Coronavirus of the family Coronaviridae of the order Nidovirales. The new type of coronavirus, which is produced by recombinant mutation of this virus in different hosts, will break out in human population once every several years [2], such as the atypical pneumonia in 2002–2003 (also known severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS), middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, and COVID-19, which are typical representatives of major outbreaks caused by the coronavirus [3]. The pathogens of them are SARS-CoV [[4], [5], [6]], MERS-CoV [7] and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [[8], [9], [10], [11]], respectively.

The length of the coronavirus genome is 27–32 kb, which is the largest RNA virus known to date [12,13]. Its genomes have the same organization and expression mode, from 5′ to 3′, which are replicase, spike protein (S), envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), nucleocapsid (N) and some accessory proteins. Among them, the S protein, which mainly mediates the binding to host cell membrane receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, ACE2) and facilitates virus entry into host cells [[14], [15], [16], [17]], is the primary target for the discovery of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs), small molecule inhibitors, vaccines, etc.

To date, some clinical diagnostic approaches, such as searching for clinical manifestations, evaluation of epidemiological history, lung imaging, virus response to the antibody in blood serum, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (rT-PCR) of the nasopharyngeal swab sample, have been used for COVID-19 detection [13]. Considering the pitfalls of traditional PCR in the way and the position of nasopharyngeal swab collection, sample transportation to the test center, RNA extraction, enzyme inhibitors, etc [13]. And the disadvantages of another commonly used enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique for high-quality antisera and the destructive to samples [18], photonics-based tools are now becoming increasingly popular in clinical science, particularly for virus detection. Till now, there have been several reviews summarized the latest advances in COVID-19 detection by utilizing optical techniques that include spectroscopic and imaging techniques [19,20]. In this review, different from the focus of the new coronavirus diagnosis, we started with the invasion mode of SARS-CoV-2 and summarized the application of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) in the development of coronavirus candidate drugs. SPR is a spectroscopy technique that detects the change in the refractive index of the interface between the analyte and the ligand immobilized on the sensor chip surface [21,22]. It characterizes the binding mechanism and determines the corresponding kinetic parameters between drugs and targets (association constant (ka), dissociation constant (kd), and binding affinity (KD)) in real time [23,24]. Due to its reliable, sensitive, and reproducible data characteristics, SPR technology has been widely used by research and pharmaceutical laboratories around the world and has become the gold standard in the field of biomolecular interaction technology.

1.1. The invasion mode of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells

Regarding the way SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells, it is generally believed that the S protein of the virus binds to the membrane receptor ACE2 on the host cells, thereby realizing the fusion of the virus and cell membrane [25]. S protein is a large trimeric transmembrane glycoprotein with a large number of glycosylation modifications, which forms a special corolla structure on the surface of the virus. It first binds to the receptors on the cell surface, and then undergoes a conformational change to integrate the virus envelop with the host cell membrane, thereby injecting the genetic materials in the virus into the host cell to achieve the purpose of infecting the cell.

Spike protein is the most important surface membrane protein of SARS-CoV-2, which contains two subunits S1 and S2. S1 mainly contains the N-terminal domain (NTD), the receptor binding domain (RBD) and two conserved subdomains (SD1 and SD2). S1 is responsible for recognizing cell receptors, while S2 contains the basic components required for the process of membrane fusion [26]. Wrapp et al., Shang et al. and Wang et al. respectively analyzed the complex structures of S protein, the RBD domain of S protein and the C-terminal domain (CTD) of S protein with human ACE2 (hACE2), and simultaneously characterized their binding affinities with SPR [[26], [27], [28]]. The KD value of SARS-CoV-2 to human ACE2 was 14.7 nM, which was 22-fold stronger than the KD value of SARS-CoV to human ACE2 (KD value: 325.8 nM). The above SPR results explained why SARS-CoV-2 is far more infectious than SARS-CoV. Lu et al. also confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 trimer S protein increased ACE2 proteolytic activity of model peptide substrates (such as caspase-1 substrate and Bradykinin-analog) by about 3–10 times [29]. Whereas, the SARS-CoV-2 core polymerase complex nonstructural proteins (nsp)-12-nsp-7-nsp8, which plays a central role in the virus life cycle, was verified to have less efficient activity for RNA synthesis and lower thermostability of individual subunits compared with SARS-CoV [30]. Meantime, compared with SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 seemed to have a narrower range of receptor selection [31]. SPR technology characterized the binding affinity of RBD from SARS-CoV-2 or SARS-CoV to ACE2 from various species. By introducing mutations that alter the conformational distribution of the S protein domains, Henderson et al. achieved conformational control of the S protein, and SPR technique was used to detect whether RBD in mutants was in ACE2-accesesible (up) state or in ACE2-inaccessible (down) state [32]. Studies on E1 (residues 417, 455–456, and 470–490) and E2 (residues 444–454 and 493–505) of the RBD indicated that E1 and E2 interacted differently with ACE2 at different salt concentrations. At high salt concentrations, the E2-mediated interactions were weakened, but they were compensated by enhancing E1-mediated hydrophobic interactions [33].

Before SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, more and more research results have confirmed that heparan sulfate on the cell surface, as the initial adsorption factor, can help SARS-CoV-2 to adsorb to the host cell surface and enhance the interaction possibility between S protein and ACE2 [[34], [35], [36], [37]] (Fig. 1 ). Heparin and its derivatives have also been proved to have good S protein binding activity and antiviral activity [36,37]. Kim and his team validated that the binding site of heparan sulfate to RBD was located in the glycosaminoglycan (GAG)-binding motif at S1/S2 proteolytic cleavage site (681–686(PRRARS)) [34]. The KD value of heparin to SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein in trimer was 7.3 pM, in contrast, the KD value of heparin to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein in monomer were only 500 and 1 nM, respectively. The results once again indicated that SARS-CoV-2 was more infectious.

Fig. 1.

The invasion mode of SARS-CoV-2 [36]. SARS-CoV-2 first attaches to the cell surface with the aid of heparan sulfate, and then enters the host cell by interacting with ACE2.

In addition to the usual RBD-ACE2 invasion mechanism, Wang et al. discovered an interaction between the host cell receptor CD147 and SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and confirmed that this interaction was a new route to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 invasion [38]. Human T cells with ACE2-deficient properties could be infected with SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses in a dose-dependent manner. However, this infection was specifically inhibited by CD147 inhibitor, Meplazumab. SPR assay results indicated that the binding affinity of CD147 to S protein was 185 nM. In addition, Cascio et al. showed that Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs) of SARS-CoV-2 E protein (E-SLiM) could bind to the PDZ domain of the wild type human PALS1 protein in the micromolar range, which may also help the virus to invade host cells [39].

The above studies on the invasion mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 have laid a good structural foundation for the subsequent research and development of antiviral drugs.

1.2. Antibody drug candidates for the treatment of COVID-19

Antibody drugs refer to protein drugs containing complete antibodies, antibody fragments, or genetically engineered antibodies. Due to their specificity, high efficiency and safety in binding with target antigens, antibody drugs have achieved rapid development in clinical malignancies, autoimmune diseases, infections, cardiovascular diseases and other major diseases [40]. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, many domestic and foreign scientific research institutions and enterprises are accelerating the development of COVID-19 antibody drugs.

Based on the pathogenic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2, combined with the application of antibody drugs in antivirus, there are currently several antibody drug treatment strategies against COVID-19 [41]: 1. Neutralizing antibodies against S protein, 2. Neutralizing antibodies against ACE2, 3. ACE2 analogs that compete with ACE2 for binding to S protein, 4. Antibodies against cytokine storms.

B lymphocytes are specialized cells that produce and secrete antibodies in the body, and play a key role in fighting infections, tumors and autoimmune diseases. Therefore, a large proportion of antibody drug candidates for COVID-19 are based on single B cells, which have been successfully isolated from patients with COVID-19 in the convalescence stage. For example, by using SARS-CoV-2 stabilized prefusion spike protein as an antigen, Brouwer et al. successfully isolated 403 monoclonal antibodies from three convalescence patients [42]. These antibodies indicated that the human body has a strong immune response to the S protein of SARS-CoV-2. SPR analysis confirmed the binding of 77 monoclonal antibody (mAb) to S protein and 21 mAb to RBD, with binding affinities in the nanomolar to picomolar range. Competitive analysis based on SPR and electron microscopy studies showed that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein contains multiple distinct antigenic sites, including several RBD epitopes as well as non-RBD epitopes. The subsequent structural characterization of these potent NAbs provided guidance for vaccine design, and the use of mAb mixtures to simultaneously target multiple non-RBD and RBD epitopes, paving the way for safe and effective COVID-19 prevention and treatment. Similarly, by using humanized mice and B cells from COVID-19 patients in recovery, Hansen et al. isolated thousands of human antibodies that could bind to SARS-CoV-2 [43]. Subsequently, among these antibodies with different binding characteristics and antiviral activities, the researchers selected pairs of highly potent antibodies that could simultaneously bind to the RBD of the S protein but have different binding sites, and proposed that the use of dual antibodies, as opposed to single antibodies, could not only provide an effective therapeutic effect, but also prevent the virus from mutating into resistance under the selective pressure of single-antibody therapy. SPR assays showed that these antibodies could bind to the trimeric SARS-CoV-2 S protein and RBD, with binding affinities ranging from picomolar to nanomolar. Also in 2020, by using the high-throughput antibody generation platform of the institute, Rogers et al. rapidly screened more than 1800 antibodies, and established an animal model to test protection [44]. According to the two epitopes on the RBD and the non-RBD epitope on the S protein, antibodies with high neutralizing activity were isolated. The team then tested neutralizing antibodies in a hamster model, two of which showed protective effects against SARS-CoV-2. The results of SPR assays showed that the neutralizing ability of the antibody that bound to RBD-ACE2 epitope correlated well with its percent competition for ACE2 receptor binding for both S protein and RBD, suggesting that the corresponding increases in binding affinity of mAbs to RBD-ACE2 epitope will likely result in the corresponding increases in neutralization potency. In addition to the above three examples, many researchers have also obtained effective neutralizing antibodies that can compete with ACE through single B cell isolation, such as CA1 and CB6 [45], P2C–1F11 [46], B38 and H4 [47], etc. Certainly, there were also some RBD-bound antibodies that do not compete with ACE2, such as EY6A [48], etc.

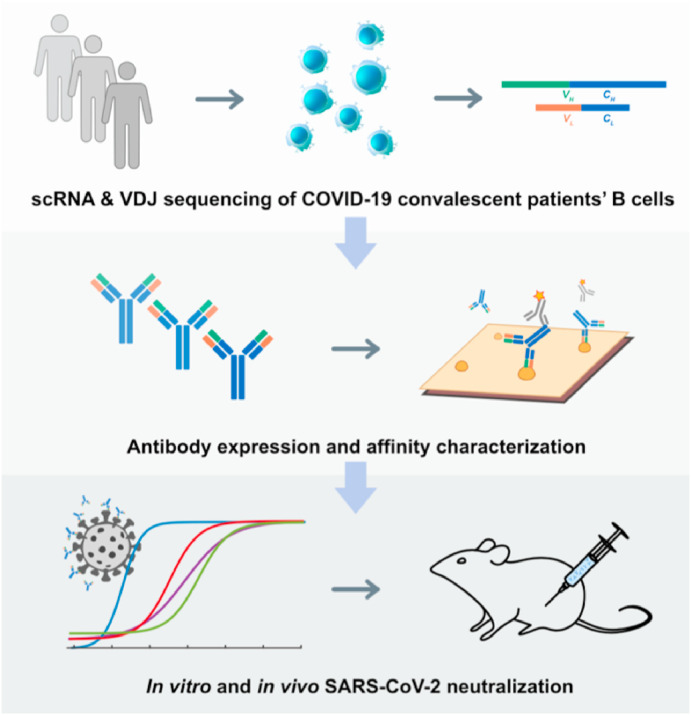

In addition to screening for potent neutralizing mAbs from human memory B cells, researchers have also developed other innovative ways to obtain antibodies that could effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2. For example, based on the technology of high-throughput single-cell sequencing, Xie et al. collected blood samples from 60 convalescent patients and screened 14 high-potent neutralizing antibodies from 8558 antigen-binding IgG1+ clonotypes [49] (Fig. 2 ). As the most potent of them, BD-368-2 exhibited the half-inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 1.2 and 15 ng/mL against pseudotyped and authentic SARS-CoV-2, respectively. SPR assays demonstrated BD-368-2 was an ACE2 competitive inhibitor, with the RBD binding affinity of 0.82 nM. They also demonstrated that in their case, only mAbs bound to RBD showed pseudovirus neutralization effects, and only mAbs bound to RBD with KD values smaller or close to the dissociation constant of ACE2/RBD (15.9 nM), would have significant neutralization effects (IC50 < 3 mg/mL) on SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus.

Fig. 2.

The schematic diagram of identifying potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of B cells from convalescent patients [49].

Except for screening and designing conventional neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, scientists have also discovered a variety of nanobodies in llama, which can effectively neutralize SARS, MERS, and the new coronavirus pseudoviruses in vitro. Nanobodies are a special class of antibodies from camels. Unlike conventional antibodies composed of light and heavy chains, this class of antibodies only have a heavy chain. The antigen-specific variable portion of this single-chain antibody is called VHH, or referred as nanobody. Interestingly, the antigen affinity and specificity of the nanobodies are not affected by the absence of the light chain variable region compared with conventional antibodies. On the contrary, it has the advantages of compatibility with phage display, low molecular weight, high stability, easy expression, and less steric hindrance. Considering the advantages of nanobodies, researchers have attempted to develop a series of nanobodies that can effectively neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Generally, there are two strategies for obtaining nanobodies, the first is to inject the coronavirus S protein, RBD or its mutants into llamas as antigens, and then screen nanobodies by phage display [50,51]. The second is to use the recombinant S protein or RBD as a bait and use phage display to screen the nanobody library [52,53]. For example, Wrapp et al. obtained VHHs from a llama immunized with prefusion-stabilized coronavirus spikes, and demonstrated that these VHHs could neutralize MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1 S pseudotyped viruses, respectively [50] (Fig. 3 ). After being fused with human lgG, these bivalent VHHs neutralized SARS-CoV-2 S pseudotyped viruses with IC50 values about 0.2 μg/ml. SPR assays characterized the binding affinity of VHHs to MERS-CoV RBD, SARS-CoV-1 RBD and SARS-CoV-2 RBD. Similarly, by screening a yeast surface-displayed library of synthetic nanobody sequences, Schoof et al. identified a panel of nanobodies that bound to multiple epitopes on spike and could block ACE2 interaction via two distinct mechanisms [51]. Among nanobodies, Nb6 was confirmed to bind spike in a completely inactive conformation, which was incapable of binding ACE2. The trivalent nanobody, mNb6-tri exhibited femtomolar binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 spike, and has picomolar neutralization effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given that mNb6-tri retained stability and function after aerosolization, lyophilization, and heat treatment, it could reach the airway epithelia through aerosol-mediated.

Fig. 3.

The schematic diagram of identifying single-domain camelid antibodies against Beta-coronaviruses [50].

Certainly, there are also some reported neutralizing antibody antigens that are not S protein or the entire RBD. For example, the extracellular domain of ACE2 fused with the Fc region of human immunoglobulin IgG1 had high binding affinity to RBD of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, and exhibited desirable pharmacological properties in mice [54]. For another example, monoclonal antibodies generated with receptor-binding motif (RBM) in RBD as the antigen could competitively bind to ACE2 and specifically blocked the RBM-induced GM-CSF secretion, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2-elictied “cytokine storm” [55]. In short, the discovery of these antibodies has accelerated the application of antibody drugs in the treatment of coronavirus.

1.3. Small molecule drug repurposing

Considering that the de novo design of small molecule drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 will take several years and will also consume huge amounts of money. Therefore, drug repurposing may be a feasible strategy in the current situation, which can greatly shorten the drug development time and help to response quickly to the new virus outbreak. At present, it has been reported that many old drugs can effectively inhibit the entrance of 2019-nCoV spike pseudotyped virus into hACE2 cells (see Table 1 ), and almost all of these old drugs target ACE2, such as astemizole [56], chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine [57], thymoquinone [58], yinqiao powder [59], lianhuaqingwen [60], astragaloside IV and rutin [61], oroxylin A [62], isorhamnetin [63], doxepin [64], antipsychotic drugs [65], loratadine and desloratadine [66], evans blue [67], etc. Of course, there are also some drugs that target S protein or both S protein and ACE2, such as quercetin and isoquercitrin [61], sodium lifitegrast [67], Linoleic acid [68], glycyrrhizic acid [69], eltrombopag [70], salvianolic acid A/B/C [71], 02B05 [72], etc. The affinity values of the above-mentioned old drugs to the target were characterized by SPR.

Table 1.

Summary of small molecule drug repurposing.

| Compound | Structure | Target | KD value to the target/μM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astemizole |  |

ACE2 | 37.5 |

| Chloroquine |  |

ACE2 | 0.731 |

| Hydroxy-chloroquine |  |

ACE2 | 0.482 |

| Thymoquinone |  |

ACE2 | 32.1 |

| Luteolin from Yinqiao powder |  |

ACE2 | 121 |

| Rhein from Lianhuaqingwena |  |

ACE2 | 33.3 |

| Astragaloside IV |  |

ACE2 | 0.369 |

| Rutin |  |

ACE2 | 66.8 |

| Oroxylin A |  |

ACE2 | 97.2 |

| Isorhamnetin |  |

ACE2 | 2.51 |

| Doxepin |  |

ACE2 | 9.54 |

| Antipsychotic drugs-Trifluoperazineb |  |

ACE2 | 33.3 |

| Loratadine |  |

ACE2 | 9.13 |

| Desloratadine |  |

ACE2 | 0.102 |

| Evans blue |  |

ACE2 | 1.63 |

| Quercetin |  |

S | 16.9 |

| Isoquercitrin |  |

S | 4.54 |

| Sodium lifitegrast |  |

S | 1.92 |

| Linoleic acid | S | 0.041 to RBD | |

| Glycyrrhizic acid (ZZY-44) |  |

S1 subunit | 0.87 |

| Eltrombopag |  |

S and ACE2 | 0.162 and 0.828 |

| Salvianolic acid A |  |

RBD and ACE2 | 3.82 and 0.408 |

| Salvianolic acid B |  |

RBD and ACE2 | 0.515 and 0.295 |

| Salvianolic acid C |  |

RBD and ACE2 | 2.19 and 0.732 |

| 02B05 |  |

RBD and ACE2 | 1.04 and 1.74 |

| EGCG |  |

3CLpro | 6.17 |

| Teicoplanin |  |

3CLpro | 1.60 |

| Dipyridamole |  |

Mpro | 34 |

| S312 |  |

DHODH | 0.0203 |

| S416 |  |

DHODH | 0.00169 |

| Leflunomide |  |

DHODH | c |

| Teriflunomide |  |

DHODH | c |

Rhein from Lianhuaqingwena: The 8 components in Lianhuaqingwen (forsythoside A, forsythoside I, neochlorogenic acid, amygdalin, prunasin, rutin and glycyrrhizin) have been confirmed to target ACE2 and have antiviral activity, we just selected rhein as the representative.

Antipsychotic drugs-Trifluoperazineb: Five antipsychotic drugs (tiapride, aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, thioridazine and trifluoperazine) in the reference have been confirmed to target ACE2 and have antiviral activity, we just selected trifluoperazine as the representative.

c: not determined.

In addition to ACE2 and S protein, the coronavirus main protease (Mpro, also known as 3-chymotrypsin-like protease, 3CLpro) is also essential for the processing and maturation of viral polyproteins, and is therefore recognized as an attractive drug target [73,74]. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) [75], an active ingredient of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), and Teicoplanin [76], an effective glycopeptide antibiotic, have been confirmed to be potent 3CLpro inhibitors with KD values in the single-digit micromolar ranges. Both EGCG and Teicoplanin could destabilize 3CLpro. Also, through the screening of the drug library, dipyridamole was proved to target Mpro with the binding affinity of 68 μM [77]. In addition to the conventionally recognized antiviral targets, Xiong et al. validated for the first time that DHODH was an attractive antiviral target [78]. Two effective inhibitors of DHODH, S312 and S416, have been showed to have broad-spectrum antiviral effects against various RNA viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. The KD values of S312 and S416 for DHODH were 20.3 and 1.69 nM, respectively. At the same time, they also demonstrated that both their self-designed candidates (S312 and S416) and old drugs (Leflunomide/Teriflunomide) with dual actions of antiviral and immuno-repression had clinical potentials not only to influenza but also to COVID-19 circulating worldwide, no matter such viruses mutate or not.

In view of the advantages of small molecule drugs in low molecular weight, low production costs, good membrane permeability and non-immunogenicity, we expect that more effective small molecule drugs can be added to the team for the treatment of COVID-19.

1.4. Vaccines for COVID-19

In terms of vaccines, the current candidate vaccines against coronavirus can be divided into two categories: (1) Gene-based vaccines, including DNA/messenger RNA vaccines, and recombinant vaccines that can produce antigens in host cells, mainly binding vectors and the live virus [79], (2) Protein-based vaccines, including inactivated whole virus and protein subunit vaccines, the antigens of such vaccines are produced in vitro. Protein subunit vaccines have shown good safety and effectiveness in preventing diseases such as hepatitis B [80] and herpes zoster [81]. However, due to their relatively low immunogenicity, RBD-based protein subunit vaccines must be used in combination with appropriate adjuvants, or optimized for appropriate protein sequences, fragment lengths, immunization procedures, etc [82]. For example, Yang et al. selected aluminum precipitates as vaccine adjuvants and constructed a recombinant S-RBD vaccine consisting of residues 319–545 of the RBD of the S protein [83]. The recombinant vaccine was found to induce effective functional antibody responses within 7 or 14 days after a single dose in mice, rabbits, and non-human primates (Macaca mulatta). Moreover, inoculation of this recombinant vaccine also protected non-human primates from SARS-CoV-2. SPR technique characterized the binding of the recombinant RBD and ACE2. However, considering that the introduction of exogenous sequences may affect the clinical potential of the recombinant vaccine, Dai et al. overcame the immunogenicity limitations of the RBD-based vaccine, and constructed the dimer form of MERS-CoV RBD linked by disulfide bonds [84] (Fig. 4 ). The dimer MERS-CoV RBD could significantly enhance the antibody response and NAb titers, and protected mice from MERS-CoV infection. Subsequently, they successfully generalized this strategy to design vaccines against SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and other β-coronaviruses. SPR technique confirmed the dimerization state of RBD would not affect its binding affinity to ACE2. With the development and application of more and more vaccines, it is expected to control the spreading COVID-19 pandemic as soon as possible.

Fig. 4.

The schematic diagram of designing CoV RBD-dimer vaccines against COVID-19, MERS, and SARS [84].

2. Conclusion

In this review, we successively introduced the invasion mode of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells, the current research status of SARS-CoV-2 candidate drugs, such as antibodies, small molecules and vaccines, and clarified the specific applications of SPR technology in these research directions. SPR, as a new means of biomolecular interaction, can detect almost all biomolecules, such as proteins, peptides, DNA, polysaccharides, liposomes, small molecule compounds, and even phages, cells, etc. SPR has been widely used to detect whether there is binding between molecules, the affinity of the binding, the speed of association or dissociation, the search for binding sites and binding order, etc. Therefore, its applications in the fields of proteomics, signal transduction, drug development, genetic analysis and food monitoring have developed rapidly, and its role has become increasingly important. For COVID-19, SPR can help us quickly understand its invasion mechanism and guide structure-based drug design. However, because it requires one of the interactions to be immobilized on the chip, it has limitations in characterizing biological targets that require the formation of multimer to be active, covalent drugs, and drugs that require incubation to generate binding activity, etc. In any case, we expect that through our summary, SPR technology can be applied to more fields during the development of coronavirus drugs, accelerate the research process of coronavirus drugs, and contribute to the control of the new coronavirus epidemic.

Author contributions

Qian Wang: Conceptualization, Writing-Original Draft. Zhenming Liu: Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 21772005) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7202088).

References

- 1.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

- 2.Su S., Wong G., Shi W., Liu J., Lai A.C.K., Zhou J., Liu W., Bi Y., Gao G.F. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zumla A., Chan J.F., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., Rollin P.E., Dowell S.F., Ling A.E., Humphrey C.D., Shieh W.J., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., Rota P., Fields B., DeRisi J., Yang J.Y., Cox N., Hughes J.M., LeDuc J.W., Bellini W.J., Anderson L.J. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drosten C., Günther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., Berger A., Burguière A.M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N., Grywna K., Kramme S., Manuguerra J.C., Müller S., Rickerts V., Stürmer M., Vieth S., Klenk H.D., Osterhaus A.D., Schmitz H., Doerr H.W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Chen H.D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shen X.R., Wang X., Zheng X.S., Zhao K., Chen Q.J., Deng F., Liu L.L., Yan B., Zhan F.X., Wang Y.Y., Xiao G.F., Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., Hu Y., Tao Z.W., Tian J.H., Pei Y.Y., Yuan M.L., Zhang Y.L., Dai F.H., Liu Y., Wang Q.M., Zheng J.J., Xu L., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S.M., Lau E.H.Y., Wong J.Y., Xing X., Xiang N., Wu Y., Li C., Chen Q., Li D., Liu T., Zhao J., Liu M., Tu W., Chen C., Jin L., Yang R., Wang Q., Zhou S., Wang R., Liu H., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shao G., Li H., Tao Z., Yang Y., Deng Z., Liu B., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Shi G., Lam T.T.Y., Wu J.T., Gao G.F., Cowling B.J., Yang B., Leung G.M., Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziebuhr J. Molecular biology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brian D.A., Baric R.S. Coronavirus genome structure and replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;287:1–30. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gui M., Song W., Zhou H., Xu J., Chen S., Xiang Y., Wang X. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res. 2017;27:119–129. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan Y., Cao D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Qi J., Wang Q., Lu G., Wu Y., Yan J., Shi Y., Zhang X., Gao G.F. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15092. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pallesen J., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Wrapp D., Kirchdoerfer R.N., Turner H.L., Cottrell C.A., Becker M.M., Wang L., Shi W., Kong W.P., Andres E.L., Kettenbach A.N., Denison M.R., Chappell J.D., Graham B.S., Ward A.B., McLellan J.S. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:7348–7357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707304114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walls A.C., Xiong X., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Snijder J., Quispe J., Cameroni E., Gopal R., Dai M., Lanzavecchia A., Zambon M., Rey F.A., Corti D., Veesler D. Unexpected receptor functional Mimicry Elucidates activation of coronavirus fusion. Cell. 2019;176:1026–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.028. e1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto S., Putalun W., Vimolmangkang S., Phoolcharoen W., Shoyama Y., Tanaka H., Morimoto S. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the quantitative/qualitative analysis of plant secondary metabolites. J. Nat. Med. 2018;72:32–42. doi: 10.1007/s11418-017-1144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukose J., Chidangil S., George S.D. Optical technologies for the detection of viruses like COVID-19: progress and prospects. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;178:113004. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samson R., Navale G.R., Dharne M.S. Biosensors: frontiers in rapid detection of COVID-19. Biotech. 2020;10:385. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper M.A. Optical biosensors in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:515–528. doi: 10.1038/nrd838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber W., Mueller F. Biomolecular interaction analysis in drug discovery using surface plasmon resonance technology. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2006;12:3999–4021. doi: 10.2174/138161206778743600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q., Liberti M.V., Liu P., Deng X., Liu Y., Locasale J.W., Lai L. Rational design of selective allosteric inhibitors of PHGDH and serine synthesis with anti-tumor activity. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017;24:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X., Yin N., Guo A., Zhang Q., Zhang Y., Xu Y., Liu H., Tang B., Lai L. NF-κB signaling and cell-fate decision induced by a fast-dissociating tumor necrosis factor mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;489:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., Lu G., Qiao C., Hu Y., Yuen K.Y., Wang Q., Zhou H., Yan J., Qi J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu J., Sun P.D. High affinity binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances ACE2 carboxypeptidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:18579–18588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng Q., Peng R., Yuan B., Zhao J., Wang M., Wang X., Wang Q., Sun Y., Fan Z., Qi J., Gao G.F., Shi Y. Structural and biochemical characterization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107774. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L., Chen Q., Liu K., Wang J., Han P., Zhang Y., Hu Y., Meng Y., Pan X., Qiao C., Tian S., Du P., Song H., Shi W., Qi J., Wang H.W., Yan J., Gao G.F., Wang Q. Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 and the molecular basis for SARS-CoV-2 binding to cat ACE2. Cell Discov. 2020;6:68. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson R., Edwards R.J., Mansouri K., Janowska K., Stalls V., Gobeil S.M.C., Kopp M., Li D., Parks R., Hsu A.L., Borgnia M.J., Haynes B.F., Acharya P. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:925–933. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0479-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva de Souza A., Rivera J.D., Almeida V.M., Ge P., de Souza R.F., Farah C.S., Ulrich H., Marana S.R., Salinas R.K., Guzzo C.R. Molecular dynamics reveals complex compensatory effects of ionic strength on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike/human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:10446–10453. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S.Y., Jin W., Sood A., Montgomery D.W., Grant O.C., Fuster M.M., Fu L., Dordick J.S., Woods R.J., Zhang F., Linhardt R.J. Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antivir. Res. 2020;181:104873. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L., Chopra P., Li X., Bouwman K.M., Tompkins S.M., Wolfert M.A., de Vries R.P., Boons G.-J. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans as attachment factor for SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.10.087288. 2020.2005.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tandon R., Sharp J.S., Zhang F., Pomin V.H., Ashpole N.M., Mitra D., Jin W., Liu H., Sharma P., Linhardt R.J. Effective inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry by heparin and Enoxaparin derivatives, bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.08.140236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mycroft-West C.J., Su D., Pagani I., Rudd T.R., Elli S., Gandhi N.S., Guimond S.E., Miller G.J., Meneghetti M.C.Z., Nader H.B., Li Y., Nunes Q.M., Procter P., Mancini N., Clementi M., Bisio A., Forsyth N.R., Ferro V., Turnbull J.E., Guerrini M., Fernig D.G., Vicenzi E., Yates E.A., Lima M.A., Skidmore M.A. Heparin inhibits cellular invasion by SARS-CoV-2: structural dependence of the interaction of the spike S1 receptor-binding domain with heparin. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020;120:1700–1715. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K., Chen W., Zhang Z., Deng Y., Lian J.Q., Du P., Wei D., Zhang Y., Sun X.X., Gong L., Yang X., He L., Zhang L., Yang Z., Geng J.J., Chen R., Zhang H., Wang B., Zhu Y.M., Nan G., Jiang J.L., Li L., Wu J., Lin P., Huang W., Xie L., Zheng Z.H., Zhang K., Miao J.L., Cui H.Y., Huang M., Zhang J., Fu L., Yang X.M., Zhao Z., Sun S., Gu H., Wang Z., Wang C.F., Lu Y., Liu Y.Y., Wang Q.Y., Bian H., Zhu P., Chen Z.N. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020;5:283. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo Cascio E., Toto A., Babini G., De Maio F., Sanguinetti M., Mordente A., Della Longa S., Arcovito A. Structural determinants driving the binding process between PDZ domain of wild type human PALS1 protein and SLiM sequences of SARS-CoV E proteins. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:1838–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez H.L., Cardarelli P.M., Deshpande S., Gangwar S., Schroeder G.M., Vite G.D., Borzilleri R.M. Antibody-drug conjugates: current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today. 2014;19:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klasse P.J., Sattentau Q.J. Mechanisms of virus neutralization by antibody. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2001;260:87–108. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05783-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brouwer P.J.M., Caniels T.G., van der Straten K., Snitselaar J.L., Aldon Y., Bangaru S., Torres J.L., Okba N.M.A., Claireaux M., Kerster G., Bentlage A.E.H., van Haaren M.M., Guerra D., Burger J.A., Schermer E.E., Verheul K.D., van der Velde N., van der Kooi A., van Schooten J., van Breemen M.J., Bijl T.P.L., Sliepen K., Aartse A., Derking R., Bontjer I., Kootstra N.A., Wiersinga W.J., Vidarsson G., Haagmans B.L., Ward A.B., de Bree G.J., Sanders R.W., van Gils M.J. Potent neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients define multiple targets of vulnerability. Science. 2020;369:643–650. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen J., Baum A., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Wloga E., Fulton B.O., Yan Y., Koon K., Patel K., Chung K.M., Hermann A., Ullman E., Cruz J., Rafique A., Huang T., Fairhurst J., Libertiny C., Malbec M., Lee W.Y., Welsh R., Farr G., Pennington S., Deshpande D., Cheng J., Watty A., Bouffard P., Babb R., Levenkova N., Chen C., Zhang B., Romero Hernandez A., Saotome K., Zhou Y., Franklin M., Sivapalasingam S., Lye D.C., Weston S., Logue J., Haupt R., Frieman M., Chen G., Olson W., Murphy A.J., Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D., Kyratsous C.A. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020;369:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers T.F., Zhao F., Huang D., Beutler N., Burns A., He W.T., Limbo O., Smith C., Song G., Woehl J., Yang L., Abbott R.K., Callaghan S., Garcia E., Hurtado J., Parren M., Peng L., Ramirez S., Ricketts J., Ricciardi M.J., Rawlings S.A., Wu N.C., Yuan M., Smith D.M., Nemazee D., Teijaro J.R., Voss J.E., Wilson I.A., Andrabi R., Briney B., Landais E., Sok D., Jardine J.G., Burton D.R. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science. 2020;369:956–963. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi R., Shan C., Duan X., Chen Z., Liu P., Song J., Song T., Bi X., Han C., Wu L., Gao G., Hu X., Zhang Y., Tong Z., Huang W., Liu W.J., Wu G., Zhang B., Wang L., Qi J., Feng H., Wang F.S., Wang Q., Gao G.F., Yuan Z., Yan J. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;584:120–124. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ju B., Zhang Q., Ge J., Wang R., Sun J., Ge X., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou B., Song S., Tang X., Yu J., Lan J., Yuan J., Wang H., Zhao J., Zhang S., Wang Y., Shi X., Liu L., Zhao J., Wang X., Zhang Z., Zhang L. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature. 2020;584:115–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y., Wang F., Shen C., Peng W., Li D., Zhao C., Li Z., Li S., Bi Y., Yang Y., Gong Y., Xiao H., Fan Z., Tan S., Wu G., Tan W., Lu X., Fan C., Wang Q., Liu Y., Zhang C., Qi J., Gao G.F., Gao F., Liu L. A noncompeting pair of human neutralizing antibodies block COVID-19 virus binding to its receptor ACE2. Science. 2020;368:1274–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.abc2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou D., Duyvesteyn H.M.E., Chen C.P., Huang C.G., Chen T.H., Shih S.R., Lin Y.C., Cheng C.Y., Cheng S.H., Huang Y.C., Lin T.Y., Ma C., Huo J., Carrique L., Malinauskas T., Ruza R.R., Shah P.N.M., Tan T.K., Rijal P., Donat R.F., Godwin K., Buttigieg K.R., Tree J.A., Radecke J., Paterson N.G., Supasa P., Mongkolsapaya J., Screaton G.R., Carroll M.W., Gilbert-Jaramillo J., Knight M.L., James W., Owens R.J., Naismith J.H., Townsend A.R., Fry E.E., Zhao Y., Ren J., Stuart D.I., Huang K.A. Structural basis for the neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by an antibody from a convalescent patient. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:950–958. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao Y., Su B., Guo X., Sun W., Deng Y., Bao L., Zhu Q., Zhang X., Zheng Y., Geng C., Chai X., He R., Li X., Lv Q., Zhu H., Deng W., Xu Y., Wang Y., Qiao L., Tan Y., Song L., Wang G., Du X., Gao N., Liu J., Xiao J., Su X.D., Du Z., Feng Y., Qin C., Qin C., Jin R., Xie X.S. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients' B cells. Cell. 2020;182:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wrapp D., De Vlieger D., Corbett K.S., Torres G.M., Wang N., Van Breedam W., Roose K., van Schie L., Hoffmann M., Pöhlmann S., Graham B.S., Callewaert N., Schepens B., Saelens X., McLellan J.S. Structural basis for potent neutralization of betacoronaviruses by single-domain camelid antibodies. Cell. 2020;181:1004–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.031. e1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoof M., Faust B., Saunders R.A., Sangwan S., Rezelj V., Hoppe N., Boone M., Billesbølle C.B., Puchades C., Azumaya C.M., Kratochvil H.T., Zimanyi M., Deshpande I., Liang J., Dickinson S., Nguyen H.C., Chio C.M., Merz G.E., Thompson M.C., Diwanji D., Schaefer K., Anand A.A., Dobzinski N., Zha B.S., Simoneau C.R., Leon K., White K.M., Chio U.S., Gupta M., Jin M., Li F., Liu Y., Zhang K., Bulkley D., Sun M., Smith A.M., Rizo A.N., Moss F., Brilot A.F., Pourmal S., Trenker R., Pospiech T., Gupta S., Barsi-Rhyne B., Belyy V., Barile-Hill A.W., Nock S., Liu Y., Krogan N.J., Ralston C.Y., Swaney D.L., García-Sastre A., Ott M., Vignuzzi M., Walter P., Manglik A. An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive Spike. Science. 2020;370:1473–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chi X., Liu X., Wang C., Zhang X., Li X., Hou J., Ren L., Jin Q., Wang J., Yang W. Humanized single domain antibodies neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by targeting the spike receptor binding domain. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4528. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huo J., Le Bas A., Ruza R.R., Duyvesteyn H.M.E., Mikolajek H., Malinauskas T., Tan T.K., Rijal P., Dumoux M., Ward P.N., Ren J., Zhou D., Harrison P.J., Weckener M., Clare D.K., Vogirala V.K., Radecke J., Moynié L., Zhao Y., Gilbert-Jaramillo J., Knight M.L., Tree J.A., Buttigieg K.R., Coombes N., Elmore M.J., Carroll M.W., Carrique L., Shah P.N.M., James W., Townsend A.R., Stuart D.I., Owens R.J., Naismith J.H. Neutralizing nanobodies bind SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and block interaction with ACE2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:846–854. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lei C., Qian K., Li T., Zhang S., Fu W., Ding M., Hu S. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16048-4. 2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiang X., Zhu S., Li J., Chen W., Yang H., Wang P., Tracey K.J., Wang H. Monoclonal antibodies capable of binding SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding motif specifically prevent GM-CSF induction. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jlb.3covcra0920-628rr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X., Lu J., Ge S., Hou Y., Hu T., Lv Y., Wang C., He H. Astemizole as a drug to inhibit the effect of SARS-COV-2 in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 2021;156:104929. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang N., Han S., Liu R., Meng L., He H., Zhang Y., Wang C., Lv Y., Wang J., Li X., Ding Y., Fu J., Hou Y., Lu W., Ma W., Zhan Y., Dai B., Zhang J., Pan X., Hu S., Gao J., Jia Q., Zhang L., Ge S., Wang S., Liang P., Hu T., Lu J., Wang X., Zhou H., Ta W., Wang Y., Lu S., He L. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as ACE2 blockers to inhibit viropexis of 2019-nCoV Spike pseudotyped virus. Phytomedicine. 2020;79:153333. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu H., Liu B., Xiao Z., Zhou M., Ge L., Jia F., Liu Y., Jin H., Zhu X., Gao J., Akhtar J., Xiang B., Tan K., Wang G. Computational and Experimental studies reveal that thymoquinone blocks the entry of coronaviruses into in vitro cells. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021;10:483–494. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin H., Wang X., Liu M., Huang M., Shen Z., Feng J., Yang H., Li Z., Gao J., Ye X. Exploring the treatment of COVID-19 with Yinqiao powder based on network pharmacology. Phytother Res. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen X., Wu Y., Chen C., Gu Y., Zhu C., Wang S., Chen J., Zhang L., Lv L., Zhang G., Yuan Y., Chai Y., Zhu M., Wu C. Identifying potential anti-COVID-19 pharmacological components of traditional Chinese medicine Lianhuaqingwen capsule based on human exposure and ACE2 biochromatography screening. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2021;11:222–236. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ye M., Luo G., Ye D., She M., Sun N., Lu Y.J., Zheng J. Network pharmacology, molecular docking integrated surface plasmon resonance technology reveals the mechanism of Toujie Quwen Granules against coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia. Phytomedicine. 2021;85:153401. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao J., Ding Y., Wang Y., Liang P., Zhang L., Liu R. Oroxylin A is a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-spiked pseudotyped virus blocker obtained from Radix Scutellariae using angiotensin-converting enzyme II/cell membrane chromatography. Phytother Res. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhan Y., Ta W., Tang W., Hua R., Wang J., Wang C., Lu W. Potential antiviral activity of isorhamnetin against SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus in vitro. Drug Dev. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ddr.21815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ge S., Wang X., Hou Y., Lv Y., Wang C., He H. Repositioning of histamine H(1) receptor antagonist: doxepin inhibits viropexis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike pseudovirus by blocking ACE2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021;896:173897. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu J., Hou Y., Ge S., Wang X., Wang J., Hu T., Lv Y., He H., Wang C. Screened antipsychotic drugs inhibit SARS-CoV-2 binding with ACE2 in vitro. Life Sci. 2021;266:118889. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hou Y., Ge S., Li X., Wang C., He H., He L. Testing of the inhibitory effects of loratadine and desloratadine on SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus viropexis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021;338:109420. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Day C.J., Bailly B., Guillon P., Dirr L., Jen F.E., Spillings B.L., Mak J., von Itzstein M., Haselhorst T., Jennings M.P. Multidisciplinary approaches identify compounds that bind to human ACE2 or SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as candidates to block SARS-CoV-2-ACE2 receptor interactions. mBio. 2021;12 doi: 10.1128/mBio.03681-20. e03681-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toelzer C., Gupta K., Yadav S.K.N., Borucu U., Davidson A.D., Kavanagh Williamson M., Shoemark D.K., Garzoni F., Staufer O., Milligan R., Capin J., Mulholland A.J., Spatz J., Fitzgerald D., Berger I., Schaffitzel C. Free fatty acid binding pocket in the locked structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science. 2020;370:725–730. doi: 10.1126/science.abd3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu S., Zhu Y., Xu J., Yao G., Zhang P., Wang M., Zhao Y., Lin G., Chen H., Chen L., Zhang J. Glycyrrhizic acid exerts inhibitory activity against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Phytomedicine. 2021;85:153364. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng S., Luan X., Wang Y., Wang H., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Tian Z., Liu M., Xiao Y., Zhao Y., Zhou R., Zhang S. Eltrombopag is a potential target for drug intervention in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;85:104419. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu S., Wang J., Zhang Y., Bai H., Wang C., Wang N., He L. Three salvianolic acids inhibit 2019-nCoV spike pseudovirus viropexis by binding to both its RBD and receptor ACE2. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:3143–3151. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu Z.L., Qiu X.D., Wu S., Liu Y.T., Zhao T., Sun Z.H., Li Z.R., Shan G.Z. Blocking effect of demethylzeylasteral on the interaction between human ACE2 protein and SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein discovered using SPR technology. Molecules. 2020;26:57. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., Yuen K.Y., Wong L., Gao G., Chen S., Chen Z., Ma D., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Design of wide-spectrum inhibitors targeting coronavirus main proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du A., Zheng R., Disoma C., Li S., Chen Z., Li S., Liu P., Zhou Y., Shen Y., Liu S., Zhang Y., Dong Z., Yang Q., Alsaadawe M., Razzaq A., Peng Y., Chen X., Hu L., Peng J., Zhang Q., Jiang T., Mo L., Li S., Xia Z. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, an active ingredient of Traditional Chinese Medicines, inhibits the 3CLpro activity of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;176:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tripathi P.K., Upadhyay S., Singh M., Raghavendhar S., Bhardwaj M., Sharma P., Patel A.K. Screening and evaluation of approved drugs as inhibitors of main protease of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:2622–2631. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Z., Li X., Huang Y.-Y., Wu Y., Zhou L., Liu R., Wu D., Zhang L., Liu H., Xu X., Zhang Y., Cui J., Wang X., Luo H.-B. FEP-based screening prompts drug repositioning against COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.23.004580. 2020.2003.2023.004580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiong R., Zhang L., Li S., Sun Y., Ding M., Wang Y., Zhao Y., Wu Y., Shang W., Jiang X., Shan J., Shen Z., Tong Y., Xu L., Chen Y., Liu Y., Zou G., Lavillete D., Zhao Z., Wang R., Zhu L., Xiao G., Lan K., Li H., Xu K. Novel and potent inhibitors targeting DHODH are broad-spectrum antivirals against RNA viruses including newly-emerged coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Protein & Cell. 2020;11:723–739. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00768-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Graham B.S. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science. 2020;368:945–946. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Valenzuela P., Medina A., Rutter W.J., Ammerer G., Hall B.D. Synthesis and assembly of hepatitis B virus surface antigen particles in yeast. Nature. 1982;298:347–350. doi: 10.1038/298347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Syed Y.Y. Recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix(®)): a review in herpes zoster. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:1031–1040. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang N., Shang J., Jiang S., Du L. Subunit vaccines against emerging pathogenic human coronaviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang J., Wang W., Chen Z., Lu S., Yang F., Bi Z., Bao L., Mo F., Li X., Huang Y., Hong W., Yang Y., Zhao Y., Ye F., Lin S., Deng W., Chen H., Lei H., Zhang Z., Luo M., Gao H., Zheng Y., Gong Y., Jiang X., Xu Y., Lv Q., Li D., Wang M., Li F., Wang S., Wang G., Yu P., Qu Y., Yang L., Deng H., Tong A., Li J., Wang Z., Yang J., Shen G., Zhao Z., Li Y., Luo J., Liu H., Yu W., Yang M., Xu J., Wang J., Li H., Wang H., Kuang D., Lin P., Hu Z., Guo W., Cheng W., He Y., Song X., Chen C., Xue Z., Yao S., Chen L., Ma X., Chen S., Gou M., Huang W., Wang Y., Fan C., Tian Z., Shi M., Wang F.S., Dai L., Wu M., Li G., Wang G., Peng Y., Qian Z., Huang C., Lau J.Y., Yang Z., Wei Y., Cen X., Peng X., Qin C., Zhang K., Lu G., Wei X. A vaccine targeting the RBD of the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces protective immunity. Nature. 2020;586:572–577. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dai L., Zheng T., Xu K., Han Y., Xu L., Huang E., An Y., Cheng Y., Li S., Liu M., Yang M., Li Y., Cheng H., Yuan Y., Zhang W., Ke C., Wong G., Qi J., Qin C., Yan J., Gao G.F. A universal design of betacoronavirus vaccines against COVID-19, MERS, and SARS. Cell. 2020;182:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]